Chapter 2

Nineteenth - Century Restorations

In 1846 the archaeologist Didron, aîné, wrote a diatribe against the restorations effected under the direction of François Debret (1813–1846). Concluding that it would be impossible to spoil Saint-Denis any further, Didron lamented: “Le mal est fait, et parfait.” To restore Saint-Denis when only wars and revolutions had left their mark on the monument would have been possible, he continued, though not easy. But to reclaim the church in 1846, after seven million francs had been spent systematically spoiling it, would be a task beyond the capabilities of archaeology.[1]

Until 1837, the beginning of Debret's final decade as architect-in-chief, the western portals had escaped a nineteenth-century restoration. As work on the building neared completion, Debret proposed the restoration of the sculpture—a project that appalled some but by no means all of his contemporaries. In the same year a bolt of lightning struck the north tower, thereby providing him with an excuse to restore the entire facade.[2] Although the electrical storm did not affect the portals, the earlier damage to the sculpture seemed to justify its repair. Debret commissioned the well-known sculptor Joseph-Sylvestre Brun, who from 1837 to 1839 worked single-handedly to restore the figurate sculpture of the three portals;[3] accounts show assistants receiving payment only for carving foliate ornament.[4] After assaults on the portals by time and wars, Brun's work proved the final indignity. In Didron's estimation, the restoration had created a “façade défigurée, dépourvue à tout jamais d'interêt historique, et fort laide d'ailleurs.”[5]

Didron used the publication Annales archéologiques, a journal he had founded, as the vehicle to alert the world to the incalculable damage that French monuments and sculpture were suffering in the name of restoration. Using the work at Saint-Denis as the tragic example, he and his collaborator,

Guilhermy, filled pages describing the atrocities committed under Debret's direction.[6] By exposing what he called the acts of vandalism and “le massacre de Saint-Denis,”[7] especially with respect to the restored portals, together they hoped to save the sculpture of other treasured monuments from a similar fate.[8]

Over the years, the Administration of Public Works had given Debret enthusiastic approval for everything he proposed and from 1830 on had supplied almost limitless funding. But his restoration of the facade caused such a stir that an official investigation followed, with a full report to the minister of the interior itemizing the egregious mistakes.[9] Debret replied in detail to the charges against him.[10] Yet opinion proved so divided that officials of the Académie des Beaux-Arts were called in to judge the matter.[11] To Didron's dismay, the officials exonerated their colleague, suppressed the critical report, and Debret continued in his post at Saint-Denis. But his shocking ineptitude soon became evident. He had rebuilt the damaged spire with stone of a greater weight than the original. The new spire put such an overload on the supporting structure that its stability was threatened, and fissures opened up across the facade that invaded the stones of the tympana. Finally Debret was relieved of his post, but with a promotion.[12] The post of architect-in-chief at Saint-Denis was offered first to one M. Duban, who accepted but then withdrew.[13] In 1846, the young architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc assumed responsibility for Saint-Denis with the intention of restoring the abbey as far as possible to its original state. He began by stabilizing the portions of the building that Debret had left in jeopardy.[14]

Beginning in the 1790s, records of public works were preserved by the national government.[15] Although far from complete, they help to reconstruct the history of the nineteenth-century restorations. Yet because of uncertainties about what had survived untouched from the twelfth century, historians of art have slighted the sculpture of the west facade in discussions of Early Gothic sculpture in the Ile-de-France. Misunderstandings of the written reports and of the archaeological evidence marred their conclusions concerning the portal ensemble. Whether critics dismissed the sculptures as completely restored but accepted the iconography as valid, all had apparently based their judgments on an examination made from ground level.[16]

Since the restorations under Debret, no significant alterations have affected the sculpture of the western portals.[17] The nineteenth-century work remains the critical problem in any evaluation of the style and iconography of

the portal ensemble. Unfortunately, the location of the royal abbey in a Parisian suburb destined to become an important industrial center has magnified the problems in many ways. As early as the 1860s more than forty-five industries began to saturate the air with chemical effluents.[18] The pollution increased as the twentieth century advanced, until all exterior surfaces of the church became corroded and soiled.[19] The decay and encrustation affected not only the surfaces of the surviving original work, but also those of the restoration—a shared condition confusing at first even to the practiced eye.

Unsound practices employed in the restoration had put some of the surviving sculptures at risk. In deference to their delicate condition the portals were not touched in the campaign of the early 1970s to clean the west facade. Yet while the south side of the west facade lay behind scaffolding covered with green baize, three roundels containing the Labors of the Months on the right jamb of the right portal were cleaned with water and sand. The pressure used was strong enough to remove the protective coating of mastic (applied as a liquid, which then hardened) as well as the grime. With those exceptions, the sculptures on all three portals remain darkened with grime, and many of them are still covered with mastic.[20]

Although disagreeing in details, the two recent attempts to ascertain the extent of damage and repairs to the portals both pointed to the need for a complete examination of the sculpture.[21] As the only way to eliminate uncertainties created by the restoration, an archaeological study of the sculpture at close quarters was begun in 1968 to identify all unspoiled twelfth-century carving. Satisfactory examination of the tympana and archivolts of the doorways was possible only from scaffolding.

The results presented in this volume are based on a meticulous examination of all carved surfaces under magnification.[22] Since layers of soot and encrustations of grime masking the carved surfaces proved a major obstacle to close observation, permission was granted to dust them lightly with a toothbrush, as needed. The brushing—definitely not a cleaning—made it possible to follow the course of mortar joints attaching the nineteenth-century carved insets, which were often partially concealed by dirt, and to expose grainy surfaces where the twelfth-century carving had been recut.

Sanding and recutting had frequently eliminated all or most of the patina of age that had survived intact on unretouched surfaces. Identifying all insets

and recutting required painstaking and repeated inspections of each carved figure under different lighting conditions. At times the light on an overcast day proved more revealing than the dazzling light of the afternoon sun on the west facade. Often the light at noon, just before the sun rounded the south tower, disclosed restorations not visible under other lighting conditions. The examination established which areas had been recut and which consisted of carved replacements of lost elements, and achieved its purpose by authenticating areas of well-preserved twelfth-century carving untouched by the restorer's chisel.

Determination of the extent of the damages, losses, and restorations to the sculpture provides the essential prelude to any consideration of iconography and style. As Erwin Panofsky once wrote, “Archaeological research is blind and empty without aesthetic re-creation; and aesthetic re-creation is irrational and often misguided, without archaeological research.”[23] In effect, the archaeological examination allows us to rediscover the style of the twelfth-century carvers of the central portal and also the iconographical intentions of those who formulated the portal program. With that knowledge, the portal can resume its rightful place in discussions of the influences upon and formation of the Early Gothic style in the Ile-de-France.[24]

Consistent with the lack of precise information about restorations to the western portals, information about their prerestoration appearance also proved inconclusive. For example, the earliest known drawing of the portals, a small-scale sketch of the entire facade made by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1600, shows the original lofty proportions of the doorways prior to the raising of the pavement in 1806, as does the one made in 1700 by Martellange (Fig. 2). The latter also indicates the trumeau of the central portal still in situ, and both sketches suggest that none of the portals had a lintel of any significant height. Yet despite those visual documents, the debate whether or not the portals originally had lintels with carved decoration has continued.[25]

Unfortunately, in both drawings the details of the portal sculpture proved too sketchy to be useful.[26] Although prerestoration nineteenth-century drawings such as the one signed by Cellérier and Legrand (Fig. 3) provide more information than the earlier two, the architects did not draw the sculpture to scale, and their drawings contain obvious inaccuracies (Fig. 4). Attachements signed by Debret in 1838 presumably should show us exactly what was restored and

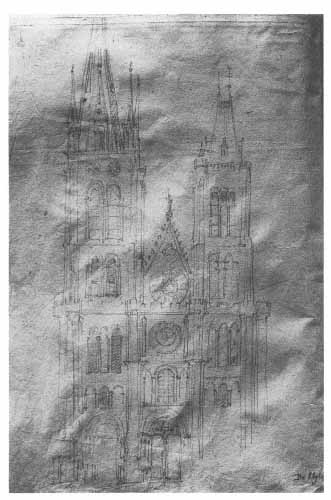

Fig. 2.

West facade. Drawing by Martellange of 1700, showing portals

before the level of the pavement was raised. Paris, Archives des

Monuments historiques

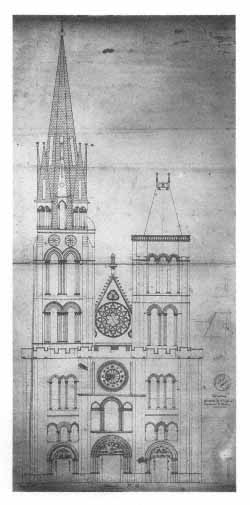

Fig. 3.

West facade. Drawing by Cellérier and

Legrand, ca. 1815, after the raising of the

pavement. Album Debret, Paris, Archives des

Monuments historiques

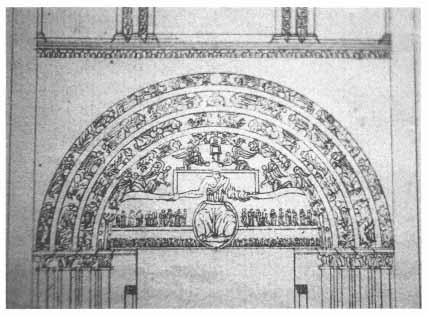

Fig. 4.

Tympanum of the central portal. Detail

of drawing by Cellérier

and Legrand (Fig. 3), ca. 1815

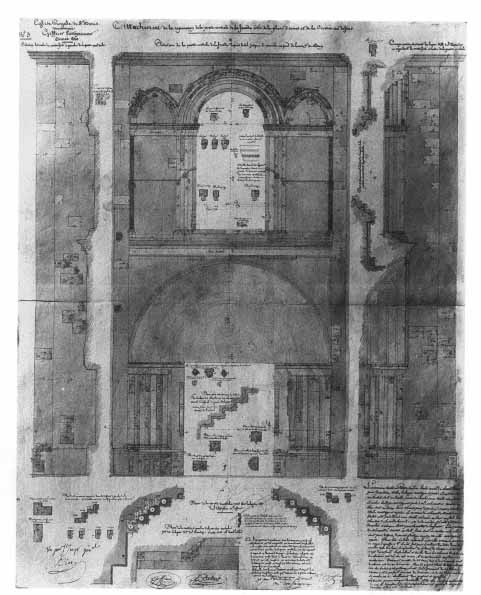

Fig. 5.

Attachement showing reparations to the central portal proposed by Debret, 1840

Album Debret, Paris, Archives des Monuments historiques

what remained untouched (Fig. 5). But in many instances, because the details do not correspond to what exists today, the attachments evidently represented Debret's intentions rather than his actual accomplishments.[27] As for written evidence, Guilhermy's record of the restorations to the portals based on his observations made in the course of the work have proved quite accurate, but not sufficiently detailed. Yet some of his conclusions about preexisting arrangements as well as some of his iconographical interpretations do not agree with the surviving evidence.

The precise information accumulated from the scaffolding is presented here in diagrams which are superimposed on photographs. They identify all untouched or surviving twelfth-century carving, every nineteenth-century inset and repair, and all recut or retouched surfaces.[28] This study focuses on the

sculptural decoration of the central portal; iconographical and stylistic observations accompany the validation of twelfth-century sculptural details.[29] Furthermore, awareness of different stylistic and aesthetic preferences manifested in the unrestored portions of the figures allows the identification of the distinct styles of three twelfth-century artists who worked on the portal, namely, the Master of the Apostles, the Master of the Tympanum Angels, and the Master of the Elders. In effect, the purpose of the archaeological examination is realized with the rediscovery of the twelfth-century styles and in the verification of iconographical details.

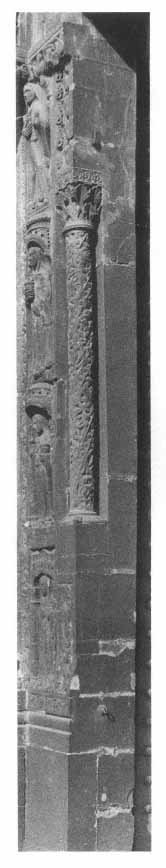

An understanding of how the twelfth-century portal was constructed proved essential in order to distinguish the nineteenth-century restorations from the original work. A number of perplexing irregularities in the masonry of the lower portions of the portal led to a careful study of the construction of the entire doorway and the adjacent buttresses of the facade (Figs. 6a-b, and Plates I, Xa, and XIa). Except where interrupted by repairs, the bottom or first four beds of masonry are continuous across the buttresses and both embrasures of the portal.[30] That linkage or bonding of the masonry between the buttresses and the portal structures ceases on both sides at the fifth bed of masonry and begins again in the spandrels between the buttresses and the archivolts, above the level of the capitals. The lack of linkage indicates that the decorated portions of the portal with which we are concerned were built as independent entities and apparently were inserted into the mural masonry of the west facade. The quality of limestone used for the portal sculpture has a much finer grain than that of the mural masonry. Emphasizing the structural independence or differentiation, the blocks of limestone in the doorways measure 29.5 cm. high and lie in regular horizontal beds, whereas the masonry of the buttresses and of the interior walls of the western bays—all part of the same campaign of building—has beds of stone that vary from 12 to 48 cm. in height. The uniformity of the portal masonry provided an objective control for detection of restorations in the decoration of the jambs. Stones that disrupt or are at variance with the regular masonry must be regarded as inserts into or changes within the original construction.[31]

The tympanum was carved from two large, originally rectangular stones shaped to form a hemicycle. Pressures exerted on those blocks caused extensive irregular fractures that must have endangered the solidity of the tympanum and

Fig. 6a

Central portal, left jamb

required unusual procedures to strengthen and support it.[32] Because the fractures continued into the narrow lintel stone, it could not adequately support the tympanum. To remedy this condition, an iron band, now functioning as the lintel, was inserted under the lintel stone. Large plaques of stone were also bolted to the back, or interior face, of the entire tympanum, presumably to stabilize it.[33]

Knowledge of the techniques and materials of the nineteenth-century restorers and an understanding of the various ways they could manipulate them was a prerequisite for recognizing their work. Because of the accidental and essentially irrational character of most of the damage, only minute examination of every figure could determine the type and extent of its restoration.[34] Fractures and decay of stone along masonry joints constituted usual areas for repairs. Projecting elements such as heads, hands, and accompanying attributes naturally suffered more than the less salient carved surfaces. To repair the heaviest damages and remedy major losses, the restorers depended primarily on newly carved insets, which they secured with metal dowels as well as mortar. A look at the diagrams (Plates IIb-XIb) shows recutting as the primary method for eliminating both major and minor mutilation. Although occasionally heavy enough to cause deformation, some of the recutting barely skinned the surface. For other repairs, the restorer drew on a reservoir of supplementary techniques involving such materials as mastic, mortar, cement, and a composite or manufactured stone as well as a gessolike material resembling terra cotta, and a liquid preservative, or mastic, that coated surfaces and gave them a shiny, uniform appearance.

Although each material seemed to have had a primary function, convenience often dictated some interchanges. Three distinctive types of mortar and a pure white cement occur throughout the portal. Those substances were used to close fractures, bind insets, and restore the masonry. The fine-grained white cement provides reinforcement for both freestanding twelfth-century sculptural elements and nineteenth-century insets. Only occasionally does it actually form the joint for an inset. As a binder, it apparently lacked the durability of the buff-colored mortar, the preferred material for attaching insets. Sometimes used lavishly in a masonry joint or as remedy for a clumsily fitting inset, the buff-colored mortar also occurs in beautifully executed hairline joinings. Their perfect condition in some of the most exposed locations testifies to the strength and endurance of the material.[35] A more granular grayish mortar

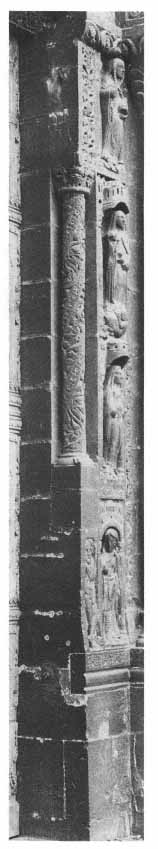

Fig. 6b

Central portal,

right jamb

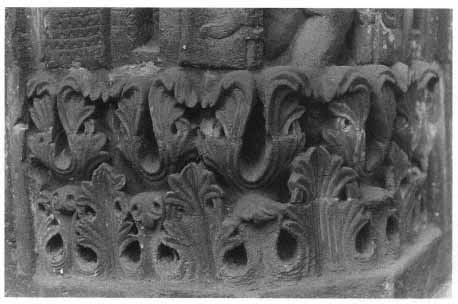

proved most effective in closing eroded and separated masonry joints. It was also used for minor patching where the damaged area seemed too small for a carved stone inset. Occasionally that mortar fills out a small break along the edge of a garment or on the frame of a musical instrument—minor repairs of the type usually reserved for mastic. The third type of mortar, a granular mixture compounded with reddish sand, occurs exclusively in repairs of voussoirs and moldings, and on the background planes, never in the sculpture proper. That material has weathered very badly and continues to crumble and fall away. A fine-grained gessolike substance with a glossy surface repairs whole sections of the foliate rinceau to the left of the Wise Virgins on the left jamb and also reconstitutes a portion of the acanthus motif ornamenting the molding of the tympanum on the left side, behind the head of the trumpeting angel.[36] In a few instances, as substitution for one of the mortars, the material spreads over small sections of a fracture or over the joint of a badly fitting inset. Composite manufactured stone occurs only in the replacements of the jambcolonnettes. Cast from molds made from the originals, those decorative colonnettes of pierre factice now occupy the recessed angles of the jambs of all three portals.[37]

Two types of mastic, now a dark gray approaching black, provided a suitable substance for delicate surface repairs. In the lintel zone of the tympanum, dribbles of mastic on the lid and front surface of the first sarcophagus on the left indicate that here the substance was applied in a liquid state (see no. 11, Plate IIIa, and the schema preceding Plate I that locates and identifies each figure). Used in that form over limited areas, the mastic smooths over abrasions or pitting. In some instances the liquid mastic seems to provide a protective coating, a thin shell-like crust, through which even the most delicate modeling of the original sculpture emerges. When tapped lightly, those resurfaced areas respond with a dry, metallic click.[38] That type of coating occurs primarily on the jamb sculpture of all three portals, as well as in the lintel zone of the central doorway. The initial use of the liquid mastic presumably dates from the alterations of 1770 and 1771.[39] When making surface repairs in the archivolts and higher zones of the tympanum, the nineteenth-century restorer applied mastic in a less viscous and more malleable form that did not harden into a brittle skin. He used it primarily to smooth over and fill out nicks, chips, and other superficial damage, and to repair ornamental borders and broken ridges of folds in

the drapery. Occasionally the buff-colored mortar substitutes for mastic in such minor surface repairs.

In the jambs and archivolts, mortar often sufficed to point up the masonry joints. But when deterioration had progressed too far, particularly when the eroded joint impinged on one of the figures, the crumbling edges were cut away in preparation for insertions of couvres-joints. Those bands of nineteenth-century stone either lie along or interrupt the original masonry joint, and the repair generally caused some distortion to both drapery and figure (Plates Xb and XIb).

The limestone used for insets in the nineteenth-century work approached the creamy, fine-grained twelfth-century limestone in quality but appears slightly yellower and coarser to the eye than the original. The broken surfaces, newly revealed by recent losses of both old and new carving, are still clean and therefore clearly show the differences in color and grain. The weathered surfaces of both the old and new stone also present contrasts in color and in texture that helped to distinguish them. As the carved surfaces of the restoration stone became coated and ingrained with industrial dirt, the larger insets acquired a uniform cold monotonic gray color quite distinct from the more variegated gray hues of the weathered twelfth-century stone. Warmed by tones of yellowish buff, the original stone has attained a mellow glow. Age and weather have crackled and pitted its surface or skin, now dappled with buffcolored specks in varying concentrations. The variegated aspect of the skin, or patina of age, resulted from minerals in the stone that were carried to the surface as the newly quarried stone dried. Aging of the patina created the effect resembling craquelure. In comparison, the nineteenth-century stone appears smooth. Identification of the two stones depended equally on those differences in texture and color that emerged readily after a light brushing with a toothbrush had disturbed the overlay of soot and dust.

Depending on its thoroughness, recutting and sanding of the old stone either removed or diminished the encrustation and the characteristic buffcolored dappling. A white powder, mingling with and dissipating in clouds of soot, invariably rose from the recut surfaces as they were brushed. The powdering suggests that recut and sanded areas were primed with a substance like plaster of Paris or gesso as a preparation for overpainting intended to harmonize the newly cut surfaces with the original, unspoiled carving. The restorer's

Fig. 7.

Central portal, socle. Detail of Gate to Paradise, first archivolt, left

concern for the final effect required a uniform hue for the finished work. In addition, the recut stone often retains telling striations representing tooth-marks of the nineteenth-century chisel. The discordant sharpness of recut details contrasts with the finely drawn details of the original carving, now somewhat muted by the pitting and encrustation of age (Fig. 7). The crackled surface of the pristine twelfth-century stone also provided a more retentive base for the deposits of soot, which adhered less well to the smoother surfaces of the recut or nineteenth-century stone. In the outer archivolts, however, weathering has accelerated the accumulation of all deposits and encrustation to a point where it is difficult to recognize insets and distinguish between unretouched and recut surfaces.

Where damage was severe, the surgery required to insert a newly carved element unfortunately caused additional destruction and loss of twelfth-century carving. A good joining for an inset necessitated the elimination of jagged stumps and all irregular surfaces along the old breaks. In the archivolts, the restorers usually achieved the optimal flat surface by cutting back to the nearest joint, which offered a structural camouflage for the repair. With few exceptions, the joints of the voussoirs coincide with the base of the neck or collar line. Identification of those insets therefore depended on the clearly visible stylistic anomalies and the textural and color differences between the old and new stone. The tympanum had no such joints to determine or limit the extent of the incursion into the old stone or to facilitate the preparation of good surfaces to receive insets replacing the heads. In the tympanum, most of the joinings for the heads lie partially concealed by the edge of a collar, striations of the hair, or a

fold of drapery. The cutting away of figures was usually kept to a minimum. Nevertheless, in several instances the figures appear to have been restored in a manner that facilitated the repairs at the expense of some of the original work (see Apostles nos. 28 and 31, Plate IVb). If possible, the restorer tried to hide joinings by making them coincide with the contours of the replaced member, whether an arm, a hand, a foot, or an attribute (see no. 31, Plate IVb). When the random nature of the damage did not allow this concealment, scattered insets create a patchwork across the figure (see no. 27, Plate IIIb).

The use of metal dowels to secure most insets has caused postrestoration fractures in both the original and the nineteenth-century stone, as well as numerous losses that clearly reveal the techniques used to attach the repair. Because of their small scale, the figures of the Resurrected Dead of the lintel zone have suffered especially severe attrition. On the right, in the second sarcophagus from the center, the figure to the right of the bishop has lost the two insets that restored his right shoulder and head (no. 16b, Fig. 8). The remaining stump of twelfth-century stone shows not only two dowel scars but also heavy patches of white mortar—vestiges of reinforcing fill never intended to be seen from the front. The smoothed surfaces that were prepared to receive the insets are visible on the right shoulder and at chin level. Apparently owing to seasonal temperature changes, expansion and contraction of the two metal dowels caused the twelfth-century stone to split and, in time, to fall away. Because the dowels were inserted at the same angle and on nearly the same plane, their movement destroyed portions of the outer surfaces of the original upper torso, the right arm almost to the wrist, and the left forearm and hand. Frequently a figure required more than one inset, each doweled from a different angle (nos. 11b, 13c, and 17b, Plates IIIb and IVb). But the old stone suffered the greatest stress when both dowels were located at the same level and on approximately the same plane.

In the small figures, the stone of the nineteenth-century insets withstood the expansion and contraction of the dowels no better than the twelfth-century stone. The resulting pressures have fractured some of the restorations and caused sections of the insets to fall away. Those losses always reveal either dowels or their scars as well as the surfaces of the twelfth-century stone cut and dressed to receive the missing portion of the inset. Unfortunately, new fractures now threaten additional losses of both old and new stone.

Fig. 8.

Detail of frieze of the Resurrected Dead, lintel

zone, right, no. 16b

Two figures provide evidence of a last-minute change of mind about procedures in the restoration. After outlining an area for excision with an incised line, the restorer decided against an inset and instead recut the damaged surface. Although recutting has eliminated all traces of mutilation, the incisions remain clearly visible across the recut thumbs of the Deity in the representation of the Trinity (no. XVIII, Plate Vb), and around the heavily recut face of the figure of the Blessed in the portal of the Heavenly City (no. VI, Plate VIb).

The final comments on the attrition of nineteenth-century repairs concern their erosion. Besides some loss of the cement and mortar that fill fractures, point up masonry joints, and repair the surface planes of the voussoirs, scattered flakes of eroded mastic indicate that many mastic repairs have peeled and dropped off, revealing the original surfaces, unrecut but pitted and scarred. That phenomenon probably explains why some of the current observations are at variance with those made several decades ago. In noting the reworking of draperies, the earlier observers frequently failed to specify whether recutting, mastic, or mortar had been employed. Since many areas once identified as “retouched” now reveal unrestored and often somewhat abraded twelfth-century surfaces, one suspects that the crust of mastic may have fallen away because of weathering in conditions of ever-increasing air pollution.

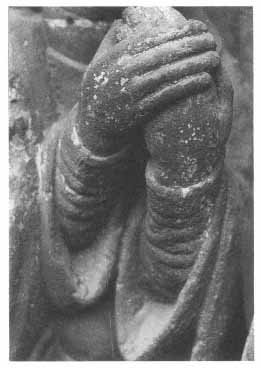

During the examination of the sculpture, evidence accumulated to suggest a scattering of minor alterations made in this century. Unfortunately no records

Fig. 9.

Twelfth-century hands. Detail of Apostle

no. 30, tympanum, right

were kept detailing the work done or noting the persons or agency involved. Photographs taken in 1935 and 1947 record a number of carved elements that had disappeared by 1968. One of the 1935 photographs shows irregular projections of stone flanking the lower half of the head of the second Apostle on Christ's left (no. 29, Plate IVa).[40] The perspective of the photograph, slightly above and to the right of the head, made the rough stone fragments appear to rise from behind the Apostle's shoulders. Because of the location, the projections cannot be construed as vestiges or stumps of original heads. Pictured in a 1947 photograph, another unidentifiable carved fragment located between the third and fourth Apostles on Christ's left (nos. 30 and 31) was once mistaken for the left arm of Apostle no. 30 (Plate IVa). Since the fragment could not be reconciled with the pose and gestures of the figure, the beautifully preserved, folded, twelfth-century hands of the Apostle were dismissed as nineteenth-century fabrications (Fig. 9). We cannot ascertain from the photographs whether that unidentifiable carved element (also visible in earlier photographs) was associated in any way with the remnants already mentioned.

Another loss, a lesser one, involved a rectangular fragment that projected from the surface plane below the crook of the right wing of the angel on Christ's left, upper tympanum zone (no. IV, Plate IId). The location suggests that the missing stump probably was carved of a piece with the angel's twelfth-century head and linked it to the upper tympanum stone. The removal of all those

fragments seems to represent an effort to tidy the tympanum. To judge from the photographs, all surfaces exposed after the fragments were chiseled away were painted gray to achieve a uniform appearance. Possibly the painting coincided with the removal of the fragments. As mentioned elsewhere, surfaces exposed since then by losses of stone still retain either the yellowish color of restoration stone or the creamier shades of the twelfth-century stone.

Study of the sculpture at very close quarters quickly revealed a great variation in the quality of the restorations.[41] The differences pertain not only to the carving of the insets and the felicity of the joinings but also to the recutting and to other minor surface repairs. The work ranges from the crudely carved and clumsy inset that completes the lower half of the figure of the Wise Virgin in the lintel zone of the tympanum, far left (no. 5, Plate IIIb), to the barely visible mortar filling Christ's wound (no. I, Plate IIb), as well as to the joint of an unobtrusive inset replacing the ear of the Lamb in the center of the third archivolt (no. XVIII, Plate Vb). Decay of the stone and the crust formed by industrial soot compounded the difficulties in locating such skillful insets, whereas the unfortunate facial style of the nineteenth-century heads, so blatantly incompatible with the twelfth-century sculpture, instantly proclaimed their modernity even in the most heavily eroded figures.

Assistance in pinpointing inserted repairs came not only from contrasts in the quality of the carving, stylistic incongruities, and the visible differences in surface colors and textures, but also from formal confusions such as unconvincing drapery arrangements or perplexing and inexplicit poses. For example, the awkward pose and stylistically discordant drapery over the right leg of the third Apostle from the left (no. 23, Plate IIIa-b), clearly identified a problem area. Visually incongruous forms coextensive with a nineteenth-century inset were often attended by minor recutting of adjacent surfaces. Drastic recutting in severely damaged areas occasionally provided equally disturbing effects. Patriarch C, on the far left in the lowest tier of the fourth archivolt (Plate VIa-b), and patriarch H, third archivolt, left, third tier (Plate VIIa-b), contain excellent examples of distortions created by recutting. The lower left portion of the former must have suffered considerable damage along the left side. The inset along the hem and the severe cutting-back of the leg, especially around the knee, and of the attendant drapery, not only created an anatomical aberration but also may have altered the pose. The original arrangement probably approximated that of

patriarch G (Plate VIIa), who sits with his right leg crossed over his left, and with his feet, although nearly parallel, also crossed. Eliminating the crossed legs of patriarch C may have enabled the restorer to minimize the size of the inset, but in so doing, he reduced the forward projection of the legs and sacrificed the forms beneath the drapery—forms strongly evoked in the better-preserved twelfth-century figures. Recutting has also noticeably changed the proportions of the lower half of patriarch H (Plate VIIa-b), and has both distorted and modified the drapery arrangement, especially from the knee down on the right side. In addition, the drastic recutting of his bench has destroyed its orthogonal perspective. The adjacent surface planes of the voussoirs appear cut back, and heavy recutting eliminated some of the foliage forming the footrest directly below. In short, the illegibility of a pose, of drapery, or of form and anatomy invariably bespeaks the hand of the restorer rather than the ineptness of the original design.