Residential Infill

55. Standard Housing, State Street near 15th, Chicago, 1868-69 (above, left). Narrow wooden buildings were one-to-a-lot in good neighborhoods, crammed one behind the other in poor sections; the unpaved street and wooden sidewalk were typical. Chicago Historical Society

56. Standard Housing in Brick, 1848 Bloomingdale Avenue, Chicago, ca. 1912 (center, left). After the 1871 fire, a city ordinance, only laxly enforced, required that the core city be rebuilt in brick. Half-cellar rental units ("up and down" housing) were created out of a single-family house design. Chicago Historical Society

57. The New Environment, 1749-59 North Whipple Street, Chicago, ca. 1912 (below, left). About five miles west of downtown, streetcars and elevated railroads opened up Humboldt Park section to the middle class and upper working class. It provided running water, public sewers, electricity, gas, paved streets and sidewalks, lawn strips and street trees, and closely set single- and two-family wooden houses. Chicago Historical Society

58. Rear Yards, 1754-58 North Whipple Street, Chicago, ca. 1912 (above). Urban houses are intended to make their best impression on the front street, and this plan was carried to the suburbs until the ranch house and attached garage of our time brought cars, children's bicycles, trash barrels, and impressive front entrances all to face the street. Here, an alley carries electricity, gives access for trash and service, with small businesses occupying sheds in rear yards before zoning prevented such mixed land uses. Chicago Historical Society

59. Nineteenth-Century Housing, 44th and Wood Streets, Chicago, 1959 (below). Industrial metropolis housing survives in working-class sections of all American cities. Here, with asphalt siding, encroached upon by cars, a "Back of the Yards" neighborhood of the 1880 standard land and housing plan. Chicago Historical Society, Clarence W. Hines

60. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, 1905. The absence of railroad tracks and easy commuting to downtown shifted the focus of fashion from South Side to the Near North Side Lake Shore. The public parkway system enhanced the private amenities of the rich. Library of Congress

61. Going to a Band Concert, Lincoln Park, Chicago, 1907. The well-to-do always have gotten the best municipal socialism in America. Lincoln Park is the nicest and most continuously maintained and improved of all the Chicago parks. It serves the fashionable North Side. Library of Congress

62. Kenilworth Avenue, near Chicago Avenue, Oak Park, 1925. Seven miles west of the Loop, just outside city limits, shaded lawns and planted streets of railroad commuters, the apogee of bourgeois propriety. Chicago Historical Society

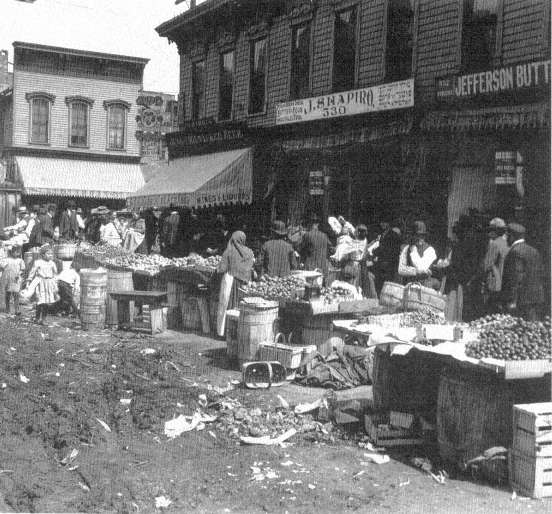

63. Maxwell Street near Jefferson Street, Chicago, ca. 1904-06. Effective street cleaning was one of the important goals of the Progressive Era. "Perhaps our greatest achievement was the discovery of a pavement eighteen inches under the surface of a narrow street, although after it was found we triumphantly discovered a record of its existence in the city archives." Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull House , 1910. Chicago Historical Society

64. Women with Market Baskets, Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904. Chicago Historical Society, Daily News

65. Children on Wooden Sidewalk, Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904. The standard of living among the poor has now risen sufficiently that, in contrast with this, today's poverty pictures show children with sneakers or shoes. Chicago Historical Society, Daily News

66. Family Waiting for Strikers' Parade, Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904. Chicago Historical Society, Daily News

67. Packing House Workers' Strike Parade, 4600 Block, Ashland Avenue, Chicago, 1904. Chicago Historical Society, Daily News

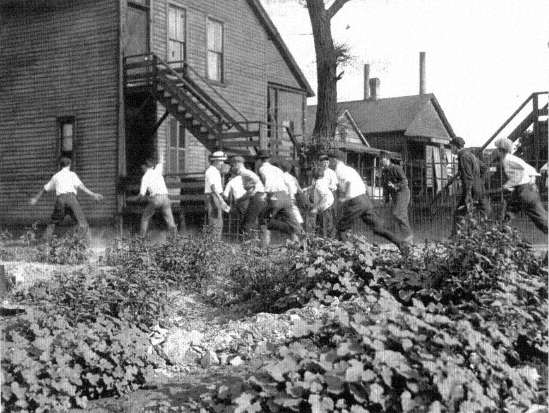

68. Mob Hunting a Black Man, Chicago Race Riots, July 1919. Lacking the racial covenants, housing price barriers, and real-estate associations of the prosperous, poor white neighborhoods enforced their apartheid by violence. Chicago Historical Society

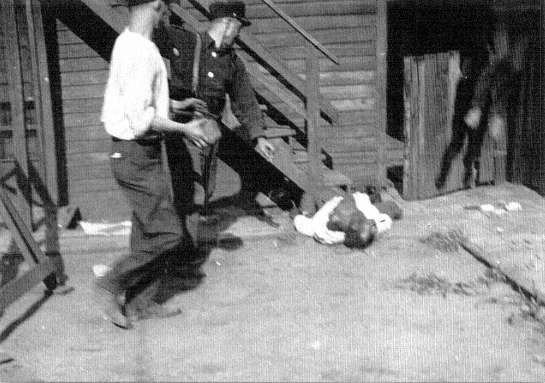

69. Black Victim Stoned to Death, Chicago Race Riots, July 1919. The fleeing man was cornered and killed by the mob. Chicago Historical Society

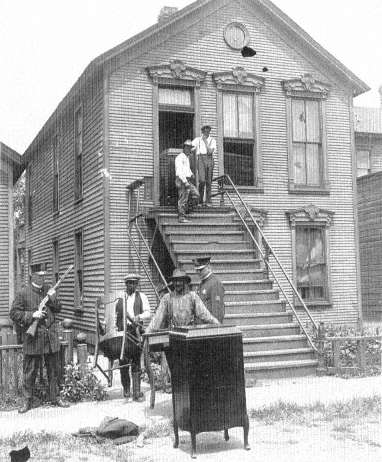

70. Blacks Evicted from Their Houses in the Wake of the Riots, Chicago, July 1919. With the old South Side ghetto jammed by blacks drawn to Chicago for wartime jobs, many sought houses on margins of their neighborhoods. A leader of nearby Kenilworth Improvement Association testified, "We want to do what is right. . . . But these people will have to be more or less pacified. At a conference where their representatives were present, I told them we might as well be frank about it, 'You people are not admitted to our society,' I said. Personally, I have no prejudice against them. They have been clean-in every way, and always prompt in their payments. But, you know, improvements are coming along the lake shore, the Illinois Central, and all that; we can't have these people coming over here." Carl Sand-burg, The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919. Chicago Historical Society

71. Under the El at 63rd Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, Chicago, 1924. Despite bombings, riots, and intimidation, the Negro ghetto could not be denied. Here is its more prosperous, growing edge, having advanced fifteen blocks south since the riots. Chicago Historical Society

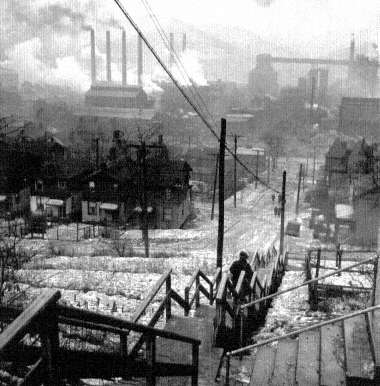

42.

Pittsburgh Mill District, 1940

43.

Michigan Avenue, Chicago, 1933

44.

Near 12th and Jefferson Streets, Chicago, 1906

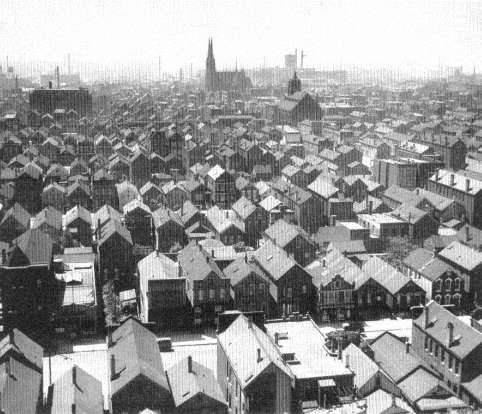

45.

Working-Class Chicago, 1934

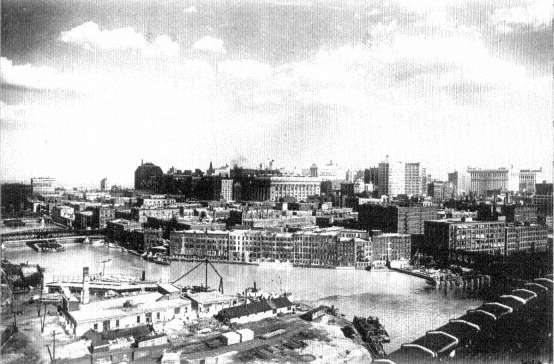

46.

South Water Street and the Chicago River, ca. 1920

47.

Michigan Avenue and Grant Park, ca. 1910

48.

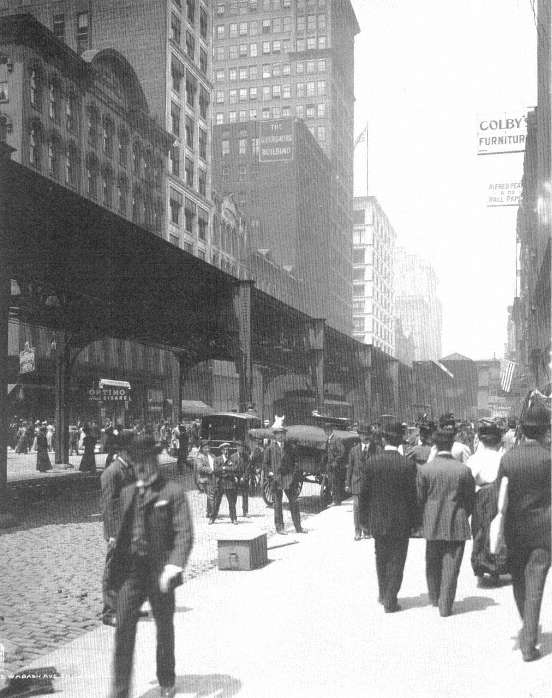

Wabash Avenue, Chicago, 1907

49.

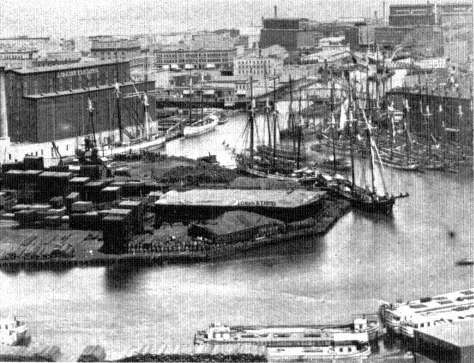

Chicago River, Looking East Toward Lake Michigan, 1875

50.

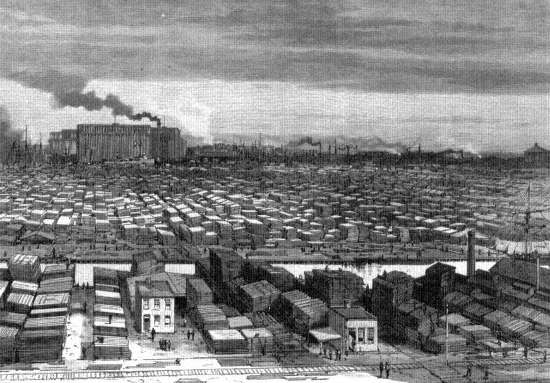

South Branch of the Chicago River, 1883

51.

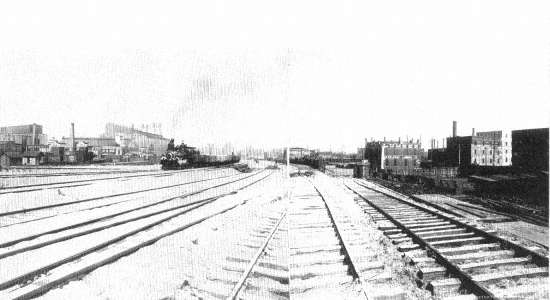

Track Elevation at 23rd Street, Chicago, ca. 1907

52.

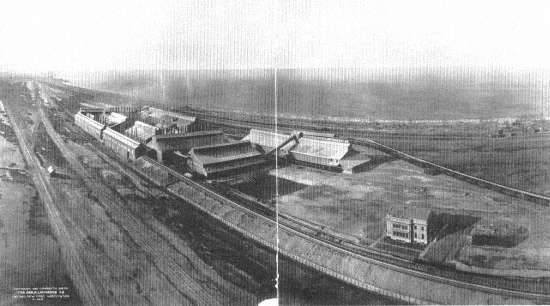

Calumet Harbor—Gary Industrial Strip, 1908

53.

Western Electric, Hawthorne Works, Cicero, ca. 1910

54.

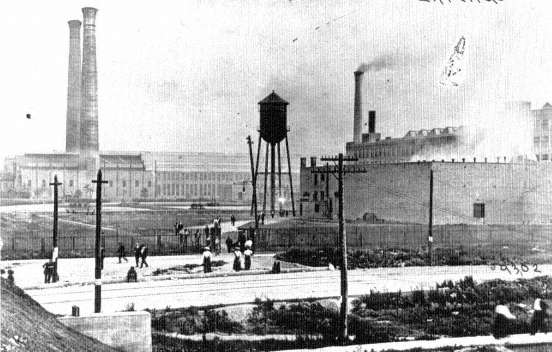

Iroquois Smelter, Calumet Harbor, South Chlcago, 1906

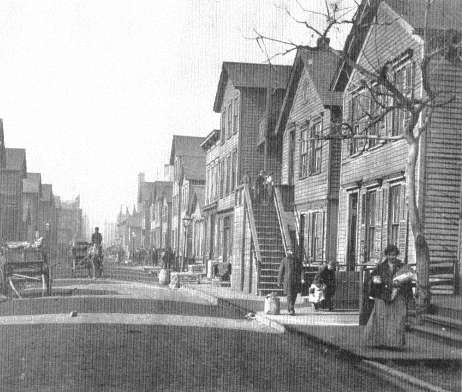

55.

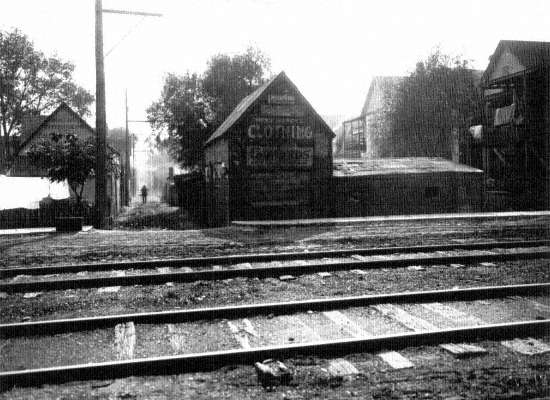

Standard Housing, State Street, Chicago, 1868-69

56.

Standard Housing in Brick, Chicago, ca. 1912

57.

The New Environment, Chicago, ca. 1912

58.

Rear Yards, Chicago, ca. 1912

59.

Nineteenth-Century Housing, Chicago, 1959

60.

Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, 1905

61.

Band Concert, Lincoln Park, Chicago, 1907

62.

Kenilworth Avenue, near Chicago Avenue, Oak Park, 1925

63.

Maxwell Street near Jefferson Street, ca. 1904-06

64.

Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904

65.

Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904

66.

Strikers Parade, Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904

67.

Packing House Workers Strike Parade, Chicago, 1904

68.

Mob Hunting a Black Man, Chicago Race Riots, July 1919

69.

Black Victim Stoned to Death, Chicago Race Riots, July 1919

70.

Blacks Evicted from Their Houses, Chicago, July 1919

71.

Under the El, Chicago, 1924

perfecting of the railroad, and the unmistakable westward flow of the American population made the occupation of the Midwest profitable, Chicago rose to service this giant hinterland. By 1856, with the completion of the Illinois and Michigan Canal and ten trunk-line railroads, Chicago began its role as a major regional center. At first it functioned simply enough. Commercially it marketed the grain and animals of the new farms while managing the flow of capital out to the farms and towns of the newly settled West, and industrially it manufactured almost every item needed to run a railroad or start a farm, to build a town, to furnish a home, or to clothe a family. The geography of Chicago thus assured its future as a world metropolis. In addition, it was placed in the most rapidly rising sector of the national economy by the functions it performed in mechanized manufacturing, transportation, finance, and servicing of business[22]

The rapid growth of all the elements that composed the city's economy in this era—factories, railroad shops and yards, banks and exchanges, warehouses, offices, department stores, and so on—forced Chicago, and indeed all contemporary American cities, into a new spatial structure: the sector-and-ring pattern of settlement. The strictness of the segregation of this urban organization and the suddenness with which it swept over American cities holds much meaning for today. On the one hand the residential segregation patterns of this era, its core of poverty and rings of rising affluence, still prevail in many cities. On the other hand the swiftness and completeness with which Americans in this era overturned their former habits suggest that in the future strong changes in transportation, job location, and housing prices could easily revolutionize what now seem to be obdurate habits of city dwellers. If we really wished to abandon our current pattern of an inner ring of poverty and black segregation, we could probably do so as quickly as we suddenly assumed it during the late nineteenth century.

In Chicago in the years from 1870 to 1920, the location of jobs was governed by the concentration of economic activity in sectors: narrow pie-shaped wedges of commercial and industrial property stretching out from the downtown business center toward farmland yet to be developed beyond the city. Between the long corridors of the industrial wedges lay vast tracts of empty land, into which settled the major part of the population in three highly segregated great rings: an inner one of

[22] . Homer Hoyt, One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago , Chicago, 1933, pp. 53-59.

poverty and low income marked by cheap divided houses and old apartments, a middle ring of secondhand working-class houses and cottages, and an outer ring of better-quality apartments and homes (Figure V, page 106). In addition, the wealthy and their followers, the downtown white-collar workers, occupied a long wedge of their own, cutting across the rings and running from the fashionable shops and downtown offices outward along the lines of good transportation and attractive sites. By 1920 the axis of this corridor lay along Michigan Avenue and the north shore on Lake Michigan. This generalized sketch of the spatial configuration of Chicago in this era—the radial city with a single center—can be applied to the other industrial metropolises of the time. It was a pattern to which all of them roughly conformed,[23] and it was the very same pattern which the highway engineers rediscovered for themselves in their traffic studies of the 1930s.

The central point from which the industrial sectors of Chicago fanned out lay at the meeting of lake and land traffic at the mouth of the Chicago River. The two sectors that were occupied first ran along the north and south branches of the river, which divided a few blocks inland from Lake Michigan just north of the central downtown area that was to become the Loop. City commerce and settlement commenced at this center. It burgeoned with the opening of the Illinois and Michigan Canal in 1848 and was thereafter continually re-formed and rebuilt by unremitting industrial pressure. Ever since, the river has served as an inner harbor for the handling of grain and lumber and coal, and manufacturers have been attracted by the accessibility of transport. The river banks became the industrial sinews of the city. Here Cyrus H. McCormick (1809-84) built his reaper factory, originally on the North Branch; later on the South Branch when he rebuilt after the Chicago fire of 1871.[24] As the city grew, competition for central space drove the price of inner-city land up and up, and industry edged ever outward from the center along the branches of the river, paralleled by the lines of the railroad. Other businesses not immediately dependent on the complementary cluster of small firms and support from the downtown services followed them out—Montgomery Ward to the North Branch,

[23] . Robert E. Park, Ernest W. Burgess, and Roderick D. McKenzie, The City , Chicago, 1925, pp. 47-58; U.S. Federal Housing Administration, The Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods in American Cities , Homer Hoyt, ed., Washington, 1939, pp. 72-78, 86-104; Harlan Bartholomew, Urban Land Uses , Cambridge, 1932, pp. 97-102.

[24] . Hoyt, Land Values in Chicago , p. 104.

Figure IV.

Industrial and Transportation Structure of Chicago, 1920, 1970

SOURCE: Homer Hoyt, One Hundred Years o/ Land Values in Chicago,

Chicago, 1933; Center for Urban Studies, University of Chicago,

Mid-Chicago Economic Development Study, Chicago, February, 1966.

machinery factories to the South Branch, while others joined Sears, Roebuck in a due-west migration from the city center.[25]

The city core itself assumed a mature form in the early years of the twentieth century. At the center, land mounted in value until it was prohibitive to manufacturing and wholesaling on any considerable scale; instead the innermost streets blossomed with skyscrapers and theaters and stores, all the full flowering of an old-fashioned metropolitan downtown. Around this center, factories and commerce threw up an immense wall of structures. The wall was composed of factories that needed minimal space and so could remain near the center by occupying multi-story buildings and of wholesale houses that were dependent on downtown passenger stations, hotels, and customer entertainment.

It is clear that this era had spawned industrial sectors and a downtown far removed from the urbanism of New York in the preceding period, with its mixed commercial and residential center and informal fringes. Rather, every part of the industrial metropolis now became more rigidly compartmentalized with each year of growth. After about 1890, no neighborhood in the city of Chicago sheltered industry, commerce, and homes of all classes of citizens; segregation of industrial, commercial, and residential land became the hallmark of the metropolis.

Rail lines coming in from the West and South added two more manufacturing sectors to those created by the Chicago River and the tracks that ran parallel to it. The transportation activity itself tending the yards, repairing cars and locomotives, building all sorts of equipment from fishplates to Pullman cars—generated an enormous volume of employment. Chicago was the nation's foremost rail-terminal city, and the prosperity of its railroads did much to build its employment base. By complementarity and the sheer expansion of urban business, these new rail sectors attracted industry. Most famous were the stockyards and meat-packing houses of the southern sector, a development of 1865 at Thirty-ninth and Halsted Streets that comprised a hundred acres of cattle pens and two hundred and seventy-five additional acres devoted to slaughterhouses and packing plants. The dependence of this gigantic operation on cattle cars and refrigerator cars forbade any but a rail location.

The stockyards forecast a special urban characteristic of the industry

[25] . Center for Urban Studies, University of Chicago, Mid-Chicago Economic Development Study , Chicago, February 1966, pp. 16-37; Hoyt, Land Values in Chicago , pp. 82-85.

of the 1870-1920 period—the movement of mammoth enterprises completely outside the confines of the core city. Steel mills, electrical machinery plants, car factories, all industries that needed good transportation for great quantities of shipments as well as vast open land for future expansion, followed the meat packers' example in seeking locations at the fringes of the manufacturing sectors.[26] In 1880, George M. Pullman (1831-97) built his shops and model town south of the city, and he was soon followed by steel mills, cement plants, and the whole Calumet River heavy industrial complex. The United States Steel Corporation placed a brand-new integrated steel plant in Gary, Indiana, a city constructed for the purpose in 1905 just east of the Calumet concentration. The industrial satellite city, a mill town set within a metropolitan region where workers could live and labor in their own community instead of commuting to work, was a characteristic type of the era. All such satellites owed their appearance to the configuration of rail transportation and the scale of late nineteenth-century mechanized manufacture. As Chairman Elbert H. Gary set his new mill down outside Chicago, so Westinghouse built in East Liberty on the edge of Pittsburgh and Ford built at River Rouge outside Detroit.[27]

Finally a spatial relationship between the metropolitan railroad lines and the outer industrial locations should be mentioned, less for its impact on the structure of Chicago in this era than for its future consequences. The radial Chicago form had emerged from the railroads that served the industrial sectors, which fanned out from the core of the city. In addition, however, transfer of freight from one line to another and from one sector to another necessitated interconnections. The most inclusive of these linkages were the rectangular belt lines that crossed over the city's radial trackage to pass almost entirely around the city. A map of the railroads in this period can therefore be seen as the superimposition of a giant grid, reminiscent of the early township grid pattern, upon the older radial lines (Figure IV, page 103). Moreover, where the belt lines intersected the radials, still other centers were created. This evolving multicentered layout helped to relieve the city's inner terminals from the traffic congestion that inevitably tends to plague a strongly central-

[26] . Harold M. Mayer, "Localization of Railway Facilities in Metropolitan Centers as Typified by Chicago," Journal of Land and Public Utility Economics , 20 (November 1944), 299-315.

[27] . Graham R. Taylor, Satellite Cities, A Study of Industrial Suburbs , New York, 1915, pp. 1-67, 165-93; Glenn E. McLaughlin, Growth of American Manufacturing Areas , Pittsburgh, 1938, pp. 127-32.

Figure V.

Class Rings and Sectors of

Residential Chicago, 1920 Source:

Federal Housing Administration,

Structure and Growth of Residential

Neighborhoods in American Cities,

Homer Hoyt, ed., Washington, 1939.

ized system with all the heaviest traffic concentrated at its center.[28] After 1900 the belt lines themselves became increasingly attractive to industrial firms. Western Electric, for example, moved its plant in 1903 to Twenty-second Street and Cicero Avenue on the outermost belt line.[29]

In the years after World War II, highway engineers began to appro-

[28] . The strong radial quality of the alignment of tracks in American cities made freight traffic jams endemic during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and brought a catastrophic breakdown during the First World War. K. Austin Kerr, American Railroad Politics 1914-1920 , Pittsburgh, 1968, p. 40.

[29] . Hoyt, Land Values in Chicago , pp. 104-7, 213; Robert L. Wrigley, Jr., "Organized Industrial Districts," Journal of Law and Public Utility Economics , 23 (May 1947), 180-98.

priate the partially occupied land along the railroad corridors, and three of Chicago's four interstate highways have repeated in a rough way the radial and grid alignments attributable to the old railroads. When the next section of the interstate Crosstown Expressway is built along Cicero Avenue, the duplication of the old rail system will be complete, and Chicago will have constructed a crude grid layout of highways whose squares grow larger as one moves from the center of the city.[30] Such a pattern has proved highly efficient for the purpose of moving traffic through a multicentered network that serves multiple locations of origin and destination. It is a pattern that much resembles the one made by Los Angeles highways, a city that so fully exemplifies the era of the automobile megalopolis.

The great preponderance of urban land has always been taken up by residential lots and streets, and these miles and miles of neighborhoods filled the spaces between the industrial fingers of the metropolis. In the half century after 1870 these neighborhoods ceased to be a jumble of rich and poor, immigrant and native, black and white, as they were in the former era of the big city. Instead the neighborhoods of the industrial metropolis came to be arranged in a systematic pattern of socioeconomic segregation. The rings of residential settlement varied from inner poverty to outer affluence,[31] and this pattern of residential segregation was as characteristic of the metropolis of 1870-1920 as were its industrial sectors, its satellites, and its downtown areas.

The suddenness with which the new pattern settled upon American cities has been documented for Chicago by its social scientists. The new possibilities of cable and electric street transit worked with rapid growth and a middle-class fashion in suburban living and downtown shopping to revolutionize the social geography of the American city.

On October 9, 1871, the Chicago Fire burned out the core of the

[30] . Center for Urban Studies, Mid-Chicago Development , plates 13 and 14; Joseph R. Passonneau, "Urban Expressway Design in the United States: The Institutional Framework," Systems Analysis for Social Problems , Alfred Blumenstein et al., eds., Washington Operations Research Council, Washington, 1970, pp. 210-22.

[31] . The sector of the wealthy, occupying an attractive site and enjoying easy transportation to the downtown (Chicago's North Shore) is a significant exception to the ring arrangement of residential land. The reasons for a sector of the rich, not a ring, are twofold: the rich are not numerous enough to fill a metropolitan ring, and they can pay enough to control expensive land near the center of the city. The phenomenon of this sector in 1870-1920 cities has been shown to be general by Homer Hoyt, in his Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods , pp. 112-22; and Peter G. Goheen, Victorian Toronto , pp. 201-13.

city and its North Side, leveling 2,100 acres of city land and destroying nearly a third of its structures. At first Chicagoans rebuilt their city in somewhat the same mixed central business and residential patterns with which they were familiar. With mortgage funds from the East, speculators rebuilt the downtown office buildings to a height of four and five stories instead of the previous two or three, while a few promoters hazarded six and even eight stories. But near the offices and stores, a block or two from the railroads, warehouses, and factories of the center of the city, many middle-class Chicagoans rebuilt their homes or settled into rented quarters or small hotels or boardinghouses in the core city.

During the 1870s the class pattern of Chicago homes bridged both the old and the new style of neighborhoods. The presence of some middle-class and well-to-do families near the downtown area recalled the old tradition, as did the outer location of many working-class dwellings. The new, however, was represented by a growing suburban fringe of middle-class families who were commuting to the downtown offices and stores.

During the next two decades the outmigration of Chicago's middle class completely reorganized the settlement patterns of the city. Instead of taking up vacant tracts in the partially built-up fringe where the working class were also settled, as had been the practice in the past, the middle class skipped over that ring entirely and settled itself in its own districts beyond. In Chicago the specific location of the ring of middle-class settlement had been determined by the building of a series of parks and boulevards in imitation of New York's Central Park and Baron Georges Haussmann's Paris boulevards. Finally mass suburban living was made possible by a succession of transportation improvements during the years from 1887 to 1894. Cable lines, electric surface lines, and elevated rapid transit all were introduced. Simultaneously, a uniform five-cent fare with one free transfer facilitated commuting.[32]

In this way Chicago's residential pattern by class had been fully set by 1894. The Loop was surrounded by decaying structures waiting to be taken up for commercial and industrial uses as the downtown expanded. Beyond this section, abandoned by the middle class, was the belt of working-class housing, close to jobs in the core city and close to the industrial sectors. Into the inner area poured the immigrants, native and foreign, and their poverty and consequent overcrowding of existing

[32] . Hoyt, Land Values in Chicago , pp. 104-7, 429.

homes transformed twenty-year-old middle-class houses and workers' cottages into the slums of the core city.[33]

With this new urban segregation of classes by housing, the core of poverty, and the rings of rising affluence, the working class came to assume the city-building role the middle class formerly performed. In the teens and twenties the working class, in order to find land to build upon or to rent, had to expand into those suburban areas which the middle class had already partially occupied, just as the middle class had earlier taken up vacant land in the mixed fringe of the old premetropolitan city. As their members moved outward they had to buy land that had already advanced in price in anticipation of suburban development. Often they found subdivisions of small lots which bore the charges of full city improvements, such as streets and curbs and sidewalks, city water and sewers, and gas and electricity, and which had to be built upon in conformity with modern building codes. The cheap working-class dwelling, the tiny wooden house or shack often built by the owner upon undesirable fringe land, now became a legal as well as an economic impossibility. Such housing returned only after World War II, with the trailer parks and self-help housing that occupy edges and pockets of the megalopolis. For most of the workers of the city the entrapment of the early twentieth-century housing pattern endured, and the loss of the single-family cottage which had been the staple of Chicago workers since long before the fire was never recovered.[34] From the first decades of the twentieth century dates the relentless shortage of decent detached homes for the blue-collar class and the widespread use of two-family and three-flat structures; by 1915, statistics showed that single-family homes had fallen to 10.8 percent of all new construction in Chicago.

The street railway, elevated in the Loop section, further influenced the makeup of metropolitan neighborhoods by nourishing the whole central-city retailing complex. Millions of men and women could now be carried cheaply in and out of the core to work and to shop. Although rows of stores sprang up along the streetcar lines and at the transfer points to serve the neighborhood, these stores faced intense competition from the shops of the Loop. Well-to-do women formed the habit of

[33] . For documentation of inner-ring housing conditions, see Edith Abbott and Sophonisba Breckinridge, The Tenements of Chicago 1908-1935 , Chicago, 1936, pp. 72-169.

[34] . Hoyt, Land Values in Chicago , p. 231.

shopping as a form of daily entertainment; for the women of the middle and working classes the seeking of bargains and major purchases in downtown stores became a focal point of their lives. To a degree perhaps not equaled since the 1830s and the heyday of the Broadway promenade in New York City,[35] the downtown district became the city for Chicagoans. It was the place of work for tens of thousands, a market for hundreds of thousands, a theater for thousands more. Yet for a city like Chicago, a metropolis of two million, even though its newspapers, tall buildings, and advertisements may have cried out for civic pride and unity, a downtown could not re-create the recognitions and sociability of a city of three hundred thousand like old New York. Instead the metropolitan downtown functioned as the symbol of unity and pride for a mass of individuals.

Chicago sociologists of the early twentieth century spoke of their fellow city dwellers as isolated individuals, cut off from each other by a screen of thousands of impersonal commercial contacts.[36] Surely the downtown and its crowds looked that way; so too did the Chicago novelists report it.[37] But the monumentality of the lake front and the Loop and their power as symbols misled the novelists. The sociological studies that have come down to us do not show a mass of two million discrete individuals but rather a highly fragmented society tightly structured along economic lines.

The scholars' reports gave the clue to the new social linkages: workers were tied to mills and foremen within them; immigrant laborers were tied to padrones and sweatshop bosses; office girls had been organized in clerical pools or became personal servants for the men they served; store clerks were at the mercy of buyers and merchants. The people of Chicago were systematized by work relationships and bound into a gigantic metropolitan economic web. The Chicago studies made plain how much of the city dweller's life was ordered by the sway of the boss, the foreman, and the buyer.

[35] . John A. Kouwenhoven, The Columbia Historical Portrait of New York , Garden City, 1953, p. 145.

[36] . Robert E. Park, "The City: Suggestions for the Investigation of Human Behavior in the City Environment," American Journal of Sociology , 20 (March 1915), 577-612.

[37] . For instance, Theodore Dreiser's Carrie Meeber in Sister Carrie (New York, 1900) and James T. Farrell's Studs Lonigan and his friends (New York, 1932-35) are overwhelmed by the early twentieth-century downtown environment which they experienced from the street. Inside the skyscrapers conditions were portrayed as more human, if also more vicious; cf. Henry B. Fuller, The Cliff Dwellers (1893).

In addition social investigations revealed that, despite basic economic ties and the class rings of residential settlement, no metropolitan class consciousness had emerged. In the residential districts there was further fragmentation by race, religion, and ethnicity.[38] Local politicians did their best to manipulate this configuration for their own ends, but it was a fragmentation without a uniform political direction. Harvey Zorbaugh's wonderful 1923 study of the near North Side of the city showed the cleavages. Here within a few square blocks lived the city's artists and writers and bohemians. There were streets of young people from the farms and small towns of the Midwest living in roominghouses and trying to find a place for themselves in the life of the city, as well as an enclave of Italian immigrants and a Persian colony, flanked along the lake edge by a narrow strip known as the Gold Coast and occupied by Chicago's oldest and wealthiest families. Such a district had not produced even district-wide power groupings, to say nothing of class consensus or political programs. Experiments by settlement-house workers or citizen volunteers to transform the district into a single social and political entity failed because the residents' significant ties were to their jobs, their homes, their ethnic groups.[39]

One extremely influential group, however, did live in the district and enjoyed city-wide ascendancy—the wealthy Anglo-Saxon Chicagoans of the Gold Coast. These families owned, controlled, or worked as professionals with the leading economic units of the city. For them the downtown and its towers were the effective center of the city. From the windows of their skyscraper offices they could look over the roofs of the city, and from their desks they could read the reports of the far-flung factories, shops, banks, and properties of the metropolitan region. It is no accident that the Commercial Club, whose members were the wealthy Chicago businessmen, should be the first to propose a city plan for the entire metropolis.

Zorbaugh concluded his study of social fragmentation by saying that the new industrial metropolis contained only one group who had the entire city as their focus, the men of the Gold Coast, and that therefore upon that group would depend the future of any program requiring city-

[38] . A recent study of elections in Chicago shows that, except for a few issues which particularly attracted the middle class, voting behavior was linked to ethnicity, not to class. See John M. Allswang, A House for All Peoples , Lexington, 1971, pp. 182-212.

[39] . Harvey W. Zorbaugh, The Gold Coast and the Slum , Chicago, 1929, pp. 182-220.

wide attention. Though an admirer of the generosity and wisdom of some of the Gold Coast families—indeed he thought them the city's only hope—Zorbaugh went on to point out that the structure of social relationships in the new metropolis was such that this elite could know nothing of the daily existence of the country boys and girls, the Sicilians, the Persians, and the bohemians who lived a few blocks away.[40] Remarkably, since the study was firmly rooted in the academic style of his day, Zorbaugh ends by describing the structure of the industrial metropolis in terms that parallel our modem assessment of the corporation which had made the industrial metropolis possible. He could have described his Chicago as Alfred Chandler did the early twentieth-century corporation:

Yet the dominant centralized structure had one basic weakness. A very few men were still entrusted with a great number of complex decisions. . . . Because these administrators had spent most of their business careers within a single functional activity, they had little experience or interest in understanding the needs and problems of the other departments or of the corporation as a whole. As long as an enterprise belonged in an industry whose markets, sources of raw materials, and production processes remained relatively unchanged, few entrepreneurial decisions had to be reached. In that situation such a weakness was not critical, but where technology, markets, and sources of supply were changing rapidly, the defects of such a structure became more obvious.[41]

Yet change, within the city and within the network of cities, had always been the essence of the American urban system. Even as downtown skyscrapers piled ever higher in the boom of the twenties, the breakup of the overcentralized, oversegregated industrial metropolis began.

[40] . Ibid., pp. 261-79.

[41] . Chandler, Strategy and Structure , p. 41.