Proven Ingredients

American cities have produced a set of characteristic responses to opportunities for planning and development that constitute the ingredients available for revitalizing center cities. Although these ingredients are not necessarily original to America, most have been modified to suit American circumstances. In the catalog that follows, we identify obvious European roots. Our descriptions are intentionally terse because these ingre-

100.

A swatch out of an American fabric includes high-speed

regional movement, arterials, neighborhood streets and

service alleys, paths, rail lines, and even a canal.

101.

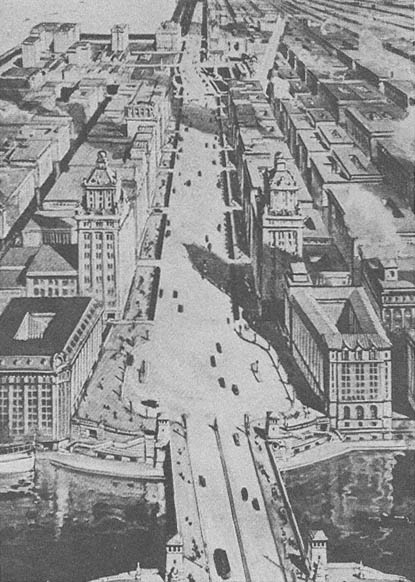

North Michigan Boulevard Extension, Chicago, 1920. From Chicago: The Great

Central Market, 1921. According to Michael Edgerton and Kenan Heise, in Chicago,

Center for Enterprise (Chicago: Windsor, 1982), property values increased by

$12 million after this transformation of what had been more modest streets.

dients can come to life only through their use by thoughtful designers responding to specific circumstances where catalysts, or support for catalysts, are needed.

Hierarchy of Movement

Although the principle of hierarchy of movement is established by European functionalist and systemic theory,

America's version of the idea is distinctive, perhaps because automobile use is so extensive and parking and access to parking have been a particular necessity. The hierarchy is efficient and workable. It admits the need for varied means and speeds of movement.

Boulevard

Because they are wider and operate as arterials, boulevards carry more traffic than typical streets. They are more pleasant to experience because of their planted median strips or verges or the tone of structures fronting them. Symbolically they lend status to addresses along the way or indicate a thoroughfare of special civic significance.

Main Street

Not surprisingly, urban elements that facilitate vehicular movement can also be places of pedestrian activity. Main Street is a major traffic artery, but it is a civic place, too. America's Main Street is a place to park a car while shopping or doing business. Teenagers cruise Main Street on Saturday night. Preservationists spruce it up to symbolize urban revitalization.

Suburban shopping centers tried to replace Main Street by offering a more palatable version that removed cars, provided shelter from the

102.

Main Street, Dallas, Texas, circa 1910. In Art Work of Dallas

(The Gravure Illustration Co., 1910), part 3.

103.

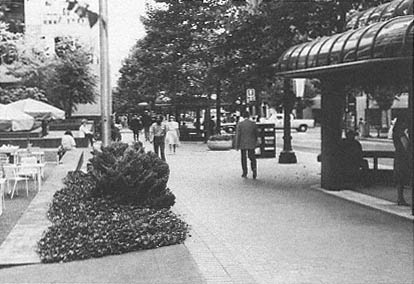

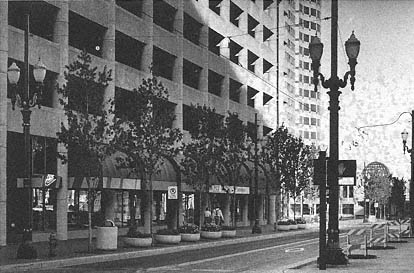

Portland Transit Mall, Skidmore Owings and Merrill, architects.

weather, and expunged references to labor and to classes other than the middle class. But this was not what was needed. What went wrong with Main Street was that as cities grew, it could not provide enough parking. Moreover, existing department stores on the main street were not large enough to survive, given contemporary retailing economics.

In response, the new version of Main Street provides convenient but unobtrusive parking, consolidates sizable retail space behind a collection of familiar facades, and mixes enough vehicles with pedestrians to give a feeling of street activity without jeopardizing safety. Discordant facades are not tamed with unifying graphics programs. Instead, vital variety is encouraged.

Transit Mall

The characteristic American problem of too many automobiles even for cities designed to facilitate automobile traffic has necessitated a customized solution to make public transit integral, attractive, and convenient. Buses and streetcars must not seem to intrude but to belong; pedestrians must feel at ease with them. Nicollet Mall in Minneapolis made the first strong case for such treatments. It proved that retailing, vehicles, and pedestrians could mix profitably through good design. A more recent example, Portland's Transit Mall, is conceived as one ingredient in the catalytic chain that is rejuvenating downtown Portland.

An economic analysis was performed to evaluate the feasibility of the [Portland Transit] Mall. The analysis identified and measured the direct benefits to transit users, and transit operating cost and safety savings, issues important to economists and planners to assess project feasibility. However, local decisionmakers and citizens are not particularly concerned with the aggregation of small savings

104.

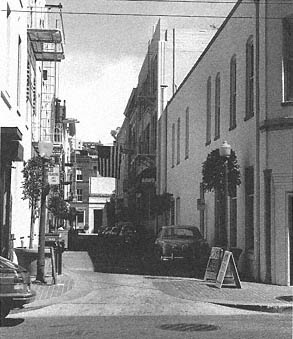

Multi-use alley in San Francisco's financial district.

of time, costs, or accidents. Rather, they are concerned with using transportation investments to maintain and strengthen the downtown area. Often investing in transportation is an expensive way to provide a competitive advantage. However, the Portland Mall has met the economic expectations well and is also extremely popular with citizens and politicians.[2]

Alley

That people and traffic can (and should) mix is a principle being explored in rethinking the role of alleys in American cities; similarly, the role of alleys solely for "service" is being rethought. Alleys add variety to the urban scene for pedestrians; they also have the potential for uses not feasible on more costly street frontage. In San Francisco's financial district, alleys are affordable sites for restaurants and office support services. (Grady Clay's book Alleys: A Hidden Resource describes the potential of alleys for improving the quality of American cities.)[3]

Skywalk

Humanistic and systemic designers in Europe called for "streets in the air" to facilitate neighboring in multi-family complexes as well as pedestrian movement in intensively developed parts of cities. The American version is skywalks that ease movement and ensure comfort in office and commercial districts. Cities like Minneapolis, St. Paul, Cincinnati, and, more recently, Des Moines and Milwaukee overlay the street grid with a pedestrian network that typically makes connections at mid-block. This pattern sometimes follows service alleys.

In most cases skywalks have been added to an existing urban fabric; a result is awkward connections where new bridges attach to older buildings. When skywalks are conceived as integral to buildings rather than as additions, the visual results are usually more pleasing.

One of the consequences of skywalks can be streets without pedestrians, for when foot traffic is elevated, and when developments are oriented to the interior of buildings, streets become the province only of vehicles. If streets are to remain "friendly," skywalks must be designed and access to them located to ensure continued use of the street level.

Riverwalk

River edges, a feature of many cities, are typified by three treatments: they are the "working" backs of buildings, providing utilitarian connections between river transport and riverside industry; they

105.

Skywalk system, Minneapolis.

106.

Paseo del Rio, San Antonio.

107.

The river and riverwalk create a separate pattern one level below downtown

San Antonio.

are formalized as pedestrian promenades (like the Embankment in London and the Seine embankments in Paris); they are naturalized as parks recalling an imagined idyllic character preceding urbanization (like Fairmont Park in Philadelphia).

America's preeminent riverwalk is San Antonio's Paseo del Rio. Although some of the building facades have been formalized, for the most part the back-side character of buildings was appreciated and accepted; all that needed to be done was to make the river's edge habitable and accessible. The result is a complex mix of buildings that formally address the river (like La Mansion Hotel, a former college) and less formal buildings that offer balconies and patios along the river.

In Milwaukee, developments downtown are stimulating renewed interest in pedestrian uses along the Milwaukee River. Riverwalk development, in turn, is supporting projects on abutting sites.

Promenade

In Europe pedestrian areas along grand boulevards and linear parks along streets change the act of getting from one place to another: these links between areas of activity themselves become destinations. That pedestrians mix with vehicles is not a detriment but a positive feature of such places, which "have always been like street theaters: they invite people to watch others, to stroll and browse, and to loiter."[4]

A promenade called the Rambla, modeled on Barcelona's Ramblas, is central to an urban design strategy for Austin, Texas, by Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown: "Make Third Street both the main street and the public square of the project. We recommend the creation of an elongated, tree-lined pedestrian avenue [that] would be on the right-of-way of the soon-to-be-removed rail line along Third Street and would link Congress Avenue to Shoal Creek and thereby to the trails of Austin."[5] American designers need not look to Europe for such precedents. Brooklyn's Esplanade overlooking Manhattan "functions as a park, a viewing spot, and as a central anchoring space for the neighborhood. It feels as if Brooklyn Heights with its tight streets, were all one great building and the Esplanade were its veranda."[6]

Galleria

Although the name galleria has been appropriated for a wide variety of spaces and places, it originally referred to pedestrian streets under glass where the mix of activities associated with a commercial street is protected by a glass roof. Milan's Galleria is the model.

When the galleria appears in America,[7] it either takes over an existing street or creates an alternative place. The galleria of the Grand Avenue absorbs service alleys, and in concert with the existing interior of Plankinton Arcade, it forms an extensive, complex place. Similarly, a project called the Courtyards for Fort Wayne, Indiana, transformed a block of disparate retail units into a new complex with a glass-covered, three-storey passage along former service alleys. Kenneth Frampton pronounced the scheme an "astonishingly clever idea in relation to the disorganized, half-abandoned inner urban detritus that is being used, which has no order.

108.

The Rambla, proposed for downtown Austin by Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown,

would establish a formal equivalent to a more typically American ad hoc version

of the promenade: the blocks of older buildings with restaurants, bars, and boutiques

along Sixth Street, not far away. The strolling, browsing,and watching characteristic

of Sixth Street could carry over to this redeveloped part of downtown.

109.

The proposed Rambla. Activities along the street are focused by the new promenade.

This introduction of an arcade system would revitalize the leftover bits, bond them together, and give them an internal life."[8]

Housing Precinct

The very term precinct suggests that a boundary or edge gives identity to a place; it also suggests a degree of security, the precinct's edge seeming defensible. Although walled compounds make poor neighbors, the desire for a sense of security must be recognized. It can be achieved by arranging housing and the passages around it to provide "eyes on the street."

The interior of a housing precinct is pedestrian oriented. Often it is raised above grade both to shelter parking and to demarcate the boundary. Shops located at grade serve a wider neighborhood as well as the housing precinct itself (see Figure 122).

Superblock

Because the ubiquitous American grid does not lend itself to all uses, development often needs to comprise a larger mesh. Milwaukee's Grand Avenue stretches across streets to create a linear shopping center paralleling Wisconsin Avenue. In Phoenix, developments encompassing six or more contiguous blocks will create building complexes around open interior spaces. Traffic flows around or enters the complex under strict control.

The advantages of assembling elements of the grid into larger blocks are efficiency and flexibility of use. A danger is that such complexes can interrupt the free movement of pedestrians or confuse a district's traffic patterns. In the past, parking podiums underlying such developments have too often created fortresslike obstructions to pedestrian movement. Then too, larger parcels can seem to justify the development of larger buildings; the combination can make a fine-grained neighborhood seem suddenly coarse.

110.

The Courtyards Development, Fort Wayne, Indiana. Eric R. Kuhne and Associates, 1985.

111.

The Courtyards Development, Fort Wayne.

112.

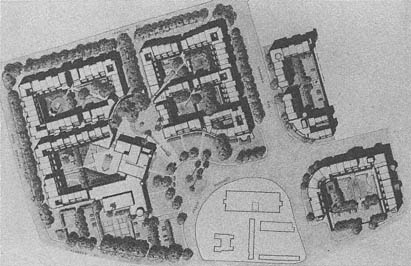

A housing precinct: La Entrada housing master plan, Tucson, Arizona,

ELS / Elbasani and Logan, architects.

113.

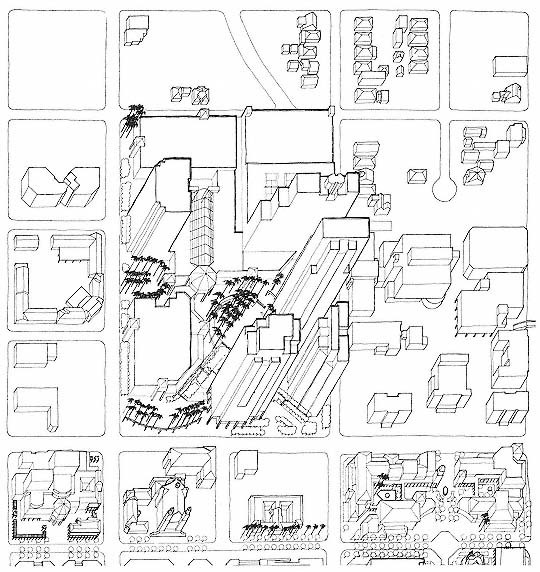

Superblock proposal for downtown Phoenix, Gruen Associates, architects.

Called superblocks, these urban elements parallel strongly Le Corbusier's notion, seen at Chandigarh in India, of pedestrian-oriented precincts within a network of roads and avenues. But in American usage they are not the underlying planning schema but are incidental, a way of drawing together or crystallizing particular areas of a city. The occasional overlaying of a larger mesh upon the grid creates welcome and often unexpected complexity within the otherwise rational and predictable urban pattern.

Pedestrian Mall

Simultaneously a goal and a place on the way to other goals, the pedestrian mall creates a realm where people on foot feel

114.

Kalamazoo Mall.

safe. Usually shops front on pedestrian malls. Associated housing is a supportive addition. Nearby parking and readily accessible public transport are crucial to keeping a mall occupied.

Regarding the success of Kalamazoo Mall over its first twenty years, a Downtown Kalamazoo Association representative concluded:

There has always been a total commitment by both the city and merchants to make the mall an attractive place to shop. There is a captive clientele of employees . . . at large businesses and institutions which ensure that a steady stream of people plies the auto-free streets. At least 75 percent of the mall stores are locally owned, a factor that guarantees a different attitude by shopkeepers and sales persons who deal with the shoppers. . . . [T]he Kalamazoo Mall was built in 1959 and as the first of its kind was early enough to attract the kind of clientele who stayed.[9]

Although for a time converting streets to malls was the most popular technique for center city redevelopment, pedestrian mall conversions do not always work. In many cases they have not brought about the anticipated retail rejuvenation—largely because they were conceived as single efforts rather than as part of a catalytic process—and the approach is less frequently used.

Positive Parking

Once the presence of automobiles is accepted as a given in American cities, provision for their storage should be handled not grudgingly but purposefully. Parking lots and, more pointedly, parking structures need to be designed as positive ingredients of the urban fabric and experience. Although the inclination to do little more than decorate parking structures is understandable, a more useful approach is to mix parking with retail businesses, offices, housing, parks, and so forth, domesticating the beasts, making them easier, more pleasant, to keep close at hand.

City Room (Interior)

Cities can have places where people gather and activities cluster in an urban mix sheltered from troublesome weather. A city room is not a pedestrian shopping street but rather a formal place that serves as a crossroads for varied activities. The Crystal Court at the IDS Center in Minneapolis embodies the idea. For Kalamazoo a more modest version at the crossroads of downtown serves similarly as a hub for hotel, shopping, restaurant, cinema, convention center, and office uses. It was conceived as the city's "living room."

115.

Morrison Park East parking structure, Portland, Oregon, tries to be a good neighbor.

116.

Crystal Court, IDS Center, Minneapolis, Johnson-Burgee, architects.

Photograph © 1986 Richard Payne, AIA.

City Room (Exterior)

Whereas the European square or piazza often grew from earlier marketplace activities, in America urban public spaces more often have formal origins as sites for courthouses and state capitols or as arcadian settings like grazing commons and landscaped parks. Outdoor urban "rooms" where people gather for informal activities were surprisingly rare in America until recent decades. According to the authors of A Pattern Language , in a "Public Outdoor Room,"

what is needed is a framework which is just enough defined so that people naturally tend to stop there; and so that curiosity naturally takes people there, and

117.

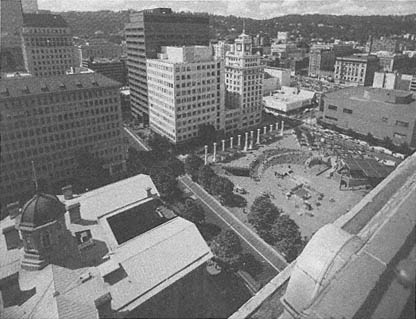

Pioneer Courthouse Square, Portland, Oregon, 1984,

Martin/Soderstrom/Matteson, architects.

Photograph © 1984 Strode Eckert Photographic.

118.

Invitation to a corporate drawing room, New York City. Park Avenue Plaza, by

Skidmore Owings and Merrill, architects.

Photograph by Joe Lengling.

119.

Redwood Park, San Francisco, which replaces a city street.

invites them to stay. Then, once community groups begin to gravitate toward this framework, there is a good chance that they will themselves, if they are permitted, create an environment which is appropriate to their activities.[10]

A recent example is Pioneer Courthouse Square in Portland, where formality and informality smoothly meld in a public place to which people are naturally attracted. The heart of Phoenix's Municipal Government Center will be a flexible city room.

Corporate Drawing Room (Corporate Atrium)

The private equivalent of the city room is the corporate atrium, a lobbylike place through which people are introduced to a building complex, a place that also serves as a semipublic urban amenity, a gift to the city. These atria are so numerous now that they constitute a coherent way of comprehending some urban centers. Publication of a "lobby and green space locater" guide to Midtown Manhattan testifies to the new pattern in New York; it is evident elsewhere as well.[11]

The type was established in America by the Ford Foundation building in New York City. Its proliferation and its tendency to create midblock linkages has produced pedestrian webs that belie the apparent regularity of the street grid. "Many [atria] have an entrance on one street and an exit on another, establishing a secondary, episodic pathway. New York's streets and avenues may seem strictly gridded and channeled, but the lobbies, in fact, make the city quite porous."[12]

Nature in the City

The purposeful provision of natural areas in city centers has been justified on the grounds of health and aesthetics, but it can also be argued for on social and economic grounds. Park or boulevard frontage increases land value; green spaces attract people and cause

120.

The Forecourt (Ira Keller) Fountain

(top) and the Lovejoy Fountain

(bottom), in conjunction with a small

park (center), create a pedestrian link

that unites sections of Portland.

121.

Site plan, Lovejoy Fountain. Lawrence Halprin, landscape architect.

them to linger. Early European examples of nature in the city were private squares associated with upper-class housing developments and public parks to provide relief from crowded living and working conditions. Corporate gardens and vest-pocket parks are recently introduced variations. The palette of design ideas for bringing nature into the city continues to broaden.

Fountain

Although in the past fountains have celebrated their practical purpose of making water available to a populace, more often they have no celebratory role and are included halfheartedly in the cityscape. Lawrence Halprin's fountains in Portland reinvigorated the impressive tradition of water as an urban element. They are not only ornaments but parts of a larger urban design strategy:

Right from the start, the Forecourt [Fountain] plays an important part in a sequence of open spaces—a matter of great importance to Halprin. This sequence starts in the adjoining Portland Center redevelopment project, where a system of planted pedestrian malls, also by Halprin, link[s] Lovejoy Plaza to Pettigrove Park—a cluster of shady green knolls—and continues to the auditorium.[13]

Microcosm

Conventionally called mixed-use developments, these complexes not only mix uses but blend them symbiotically. It is not enough to put housing adjacent to offices or to mix shops and convention facilities; the uses must reinforce each other. When the various ingredients of a mixed-use complex are related strategically to make them work the way a good city works, the complex becomes a microcosm of the city. Edmund Bacon argues that we should undertake such projects

because they intensify the richness of living, enhance people's range of experience and create easy access to a nearly inexhaustible variety of activities. Mixed

use developments are designed at a human scale and represent a positive attempt by the development community to achieve the public objective of keeping central cities alive and making cities a viable organism.[14]

Realm in Between

Although buildings-as-objects are a natural focus of urban design, there is also a peripheral area that is too often for-

122.

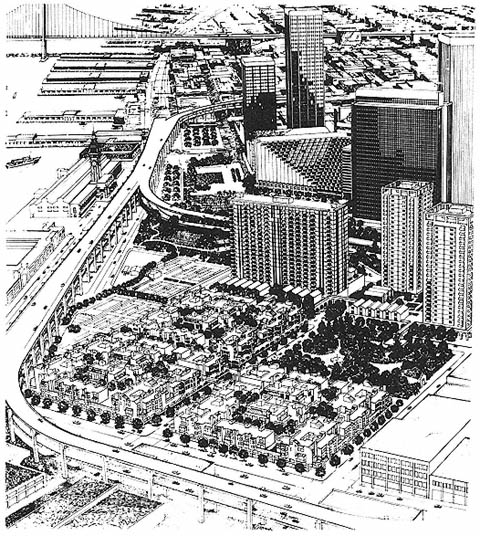

Embarcadero Center, Golden Gateway, and Golden Gateway Commons, San

Francisco. John Portman, Wurster Bernardi and Emmons, and

Fisher-Friedman, architects, designed various elements, 1962–1985.

123.

The Brewery, Milwaukee, a proposal for a mixed-use project incorporating the former Blatz Brewery,

Pabst Bottling Plant, other brick loft buildings, and new construction that in the end would provide

470 apartments, 300 hotel rooms, and 1 million square feet of offices, shops, and parking.

ELS / Elbasani and Logan, architects, 1978.

124.

In Kalamazoo, the areas behind the

Haymarket Historic District and

the areas between Bronson Park

and Kalamazoo Mall could become

realms in between other places.

gotten. Between the focal elements lie realms of less precise character that nonetheless have immense potential. Between the civic center and the pedestrian mall in Kalamazoo, for example, are pedestrian passages that potentially can offer an alternative location to the commercial activities on the pedestrian mall and an informal alternative to the civic park nearby. Similarly, between the formal Haymarket historical buildings and adjacent open space is an informal realm suited to more modest commercial uses.

Pocket of the Past

Groups of older buildings with a particular character can give parts of a city individuality and character. "Historic district" is more than a bureaucratic designation; it is a promise of character and visual interest. The economic incentives for preservation created in the 1960s and 1970s slowed demolition long enough for it to be proved that pockets of the past are not an urban liability but a versatile and attractive resource. In Portland's downtown the Yamhill and Skidmore districts are crucial elements of the overall revitalization strategy, as Figure 76 indicates.

Designated-Use District

Arts districts, cultural districts, educational districts, and so forth are all areas in which particular uses benefit from proximity to one another and where the concentration of these similar uses gives an area of the city a special flavor. Unique precincts with distinctive patterns of use (Sundays, late night, early evening, and so on) provide the satisfying variety needed in a healthy city. Theater districts in Milwaukee and Portland exemplify the pattern (see Figures 33, 82).

City Stoop

A stoop lets people sit and watch the city go by. A cascade of steps (the Spanish Steps, Rome; the Opera House steps, Stockholm; the New York Public Library steps) invites large numbers of them to observe the passing scene. It is not surprising that Martin/Soderstrom/Matteson's Portland Square design includes a substantial city stoop.

Colonnade/Arcade

Like many other elements of urban design, the colonnade, or arcade, grew out of a practical need but developed the power to mold urban character. In Southern Europe it shelters shops from the sun, and pedestrians (and casual business and socializing) from both sun and rain. Besides serving its practical purpose, it has achieved another end, giving continuity and character to urban settings. In Pasadena a colonnade was proposed to organize a collection of uses and diverse buildings, in fact to draw together several city blocks into a coherent, identifiable complex. A gesture of this magnitude seems in keeping with Pasadena's powerful city hall (glimpsed at the bottom of Figure 126).

125.

Portland's Pioneer Courthouse Square with its "stoop"

in use. Martin/Soderstrom/Matteson, architects, 1984.

126.

A design proposal for Plaza las Fuentes, Pasadena, California, by Moore/Ruble/Yudell, architects

and planners; Lawrence Halprin, landscape architect; and Barton Myers Associates, architects, 1985.

Furnished Street

Whereas life on the streets of European cities grows from necessity (daily shopping, moving between public transport and work or home, meeting friends), street life in American cities is largely voluntary and much more passive. As a result, American designers work hard to make the street environment comfortable and respectable—almost like home—with places to sit, handy trash receptacles, flowers and trees, good lighting, and an overall sense of design coordination. The American view is that people at leisure will enjoy watching others who are not. Part of the success of street conversions like Nicollet Mall (Figure 127) is attributable to the quality of its furnishings.

127.

Nicollet Mall, Minneapolis, Lawrence Halprin, landscape architect.

Photograph by Lawrence W. Speck.

128.

Chicago's Water Tower celebrates public works, identifies its district, and

ornaments Michigan Avenue.

129.

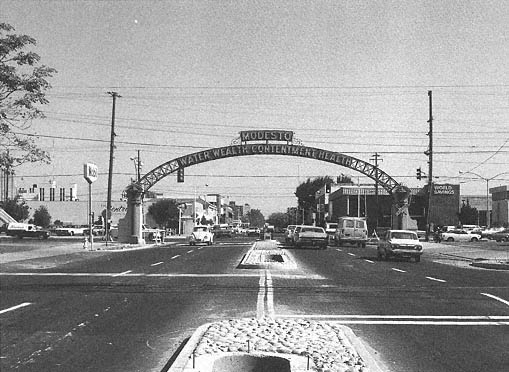

Typically, gateway arches have been more promotional than celebratory, but nonetheless they

give scale and lend a sense of significance.

Monument

Monuments celebrate heroes, civic services, and cultural achievements. Water towers in Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Louis, and Louisville are nineteenth-century celebrations of public water supplies. A twentieth-century equivalent is a Boston water tank transformed into a canvas for art. The State Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Indianapolis is intrinsic to that city's identity. From a utilitarian standpoint, monuments are landmarks, too, identifying districts and helping us stay oriented.

At another scale, markers of the skyline, like Philadelphia's and Milwaukee's city halls, are collective symbols. And though sometimes controversial, office buildings too can become, like the Empire State Building, the Transamerica headquarters, and the Sears tower, integral parts of a city's visual image. Skytowers, with their revolving restaurants and observation decks, are the latest urban monument in America. Gateway arches of an earlier era were more promotional than celebratory, but because of their location and size, they achieved the goal of bringing monuments close to daily life (Figure 129).