XIX

Friendly urging on Garry's part had made his home our daily rendezvous. Our conversations were usually in English. He had a mastery of French and German as well. Occasionally, I spoke to his hospitable wife, either in French or Russian. Though she knew the general nature of my work and had read Garry's article about it, we never discussed these details nor the confidential matters which developed from them.

A friendship grew between Garry and myself. I appreciated his energy, persistence and sincerity. He spared no effort in pursuing the end for which we were struggling. Under the surface of his official hardness, I found him to be a warm, varied personality. His mind was always sharp and clear. Fruitful ideas flowed continuously from it. His strange life was crowded with amazing, almost incredible experiences. Master of several languages, a brilliant journalist, with profound psychological insight and considerable technical knowledge, he insisted, laughingly, that at fourteen he had run away from school and had never thereafter entered the gates of any educational institution. He had joined the revolutionary movement in Russia at an early age and distinguished himself in the Civil War fighting.

During the turbulent years of consolidation of power by the Communist government, Garry had been an officer of the Cheka, the predecessor of the O.G.P.U. As the government became more firmly established, he was drawn away from the military and espionage phases of revolutionary activity and entered journalism, specializing in technical and industrial fields. His influence grew rapidly.

His far-flung activities had led to a sinister episode veiled in mystery. A fighting journalist, constantly investigating the serious difficulties in the seething transformation of the nation, involved in cases of real or suspected sabotage, he was frequently embroiled in bitter conflicts with bureaucratic officials, whom he attacked mercilessly. Once his enemies succeeded in having him exiled. According to rumor in Moscow he was released through the personal intercession of Stalin.

As our association developed he revealed to me intimate details of his crowded, exciting life and I disclosed parts of my existence and activities to him. He seemed the only Russian I knew in whom I could place confidence without reservations. I sorely needed someone. My position on the technical staff of the Workers' and Peasants' Inspection Commissariat sometimes placed me in situations which made it extremely important to have the counsel of an experienced mind thoroughly conversant with Russian psychology and habits. At this time, also, my intimate friendship with the great Russian actress, who had planned to return with me to America, was in tragic dissolution.

Accordingly, I told Garry of my confidential appointment to the R.K.I. It would be helpful to me, and for the work, I said, if I could consult him occasionally. Among my assignments had been the unusual request for a memorandum on the possibilities of recognition of the U.S.S.R. by the U.S.A. I had made a report dated June 28, 1933. It read as follows:

The possibility of diplomatic recognition of the government of the Soviet Union by the United States of America, so momentous in present world relations, hangs in the balance between two sets of opposing forces. Some of these forces are deeply rooted in the characteristics of the American people. Others spring from the influence of important institutions. Still others arise from disturbances in the present international situation, which is forcing a new alignment of the Great Powers.

Advocates of Soviet recognition in the United States may be listed as follows:

(1) Intellectual and liberal groups in the universities and cities, and liberal journalists who are dissatisfied with the prolonged economic crisis and who are attracted by the social program of the U.S.S.R., the small amount of unemployment, and the idea of a planned national economy. Though in some cases they have high specialized standing, they are few in number, and their influence in the government and over the masses is slight.

(2) Professional radicals; members of the Communist Party, Socialist Party, and others. Recent elections exhibit their numerical weakness and lack of hold on the American people.

(3) Manufacturers who have profited by Soviet business orders, or who have hopes of such profit by the development of trade between the two countries.

(4) Politicians who guess that recognition is coming, and wish to be associated in the popular mind and the Press with its advocacy.

(5) A section of the liberal press, notably the Scripps-Howard Press, its owner, Roy Howard; the United Press, its manager, Karl Bickel; and

several American foreign correspondents, especially Eugene Lyons, William Henry Chamberlin, Walter Duranty, and Louis Fischer, who have been instrumental in sympathetically informing the American public of developments in the U.S.S.R.

(6) Anti-Japanese elements of the population of the Pacific Coast states, California, Oregon, etc., and manufacturers whose Chinese trade is jeopardized by Japanese aggression in Manchuria.

Opposing these groups in their advocacy of recognition are powerful forces and institutions which may be classified as follows:

(1) Strong anti-Communist feeling in all classes of American society, growing out of the individualistic philosophy which has hitherto dominated the American economic scene. Added to this is the knowledge of the great wealth which has resulted from high industrial productivity in capitalistic society, though distribution of wealth has been inequitable.

(2) The Catholic Church, controlling the thoughts of millions of the population; standing like a rock against Bolshevism and its program of liquidation of established religion.

(3) Protestant Church denominations; much less unified and definite in their actions than the Catholic Church, but opposing any social order which might reduce or limit their power.

(4) The American Federation of Labor, which opposes Communism on the grounds of low living standards of Soviet workers, the effects of Soviet competition in international markets, and the curtailed autonomy and power of the Soviet trade unions.

(5) The conservative press, which constantly emphasizes the abolition of free speech, free press and free assemblage in the U.S.S.R., together with the bureaucracy, the low standard of living, the food shortage and resulting famine, and the unsatisfactory experiences of American engineers in the U.S.S.R.

(6) The traditional attitude of the State Department in linking the question of recognition of the Soviet Union per se, as a stable, established government, with approval of Communist social and economic policies, especially the repudiation of Czarist debts and Communist propaganda, and refusing the former because of its rejection of the latter.

(7) Patriotic societies, such as the American Legion, the Better America Federation, the Daughters of the American Revolution, and others, who bitterly oppose a Communist social order.

Careful study of the American scene reveals that in the minds of the American people, including most of the groups above, recognition of the Soviet Government is intimately related to approval of its social and economic order, and to a fear that recognition might be an impetus to the spread of Bolshevism in the United States. It is extremely difficult to disassociate recognition from approval in the American mind.

Pro-recognition agitation based on the hope of expanding trade between the two countries has lost force, because it is becoming clear that the total possible amount of foreign trade with the U.S.S.R. is small, com-

pared to the enormous home market which has fallen off and which urgently requires re-establishment, and secondly, because Soviet trade would have to be financed by extensive, long-term credits. At present, foreign credits are in great disfavor in the U.S.A. Banking circles are not supporting such ventures. The government definitely opposes any.

There remains the uncertain trend of the Roosevelt foreign policy, which has extended the opportunity at London for a possible rapprochement between the two countries. Japanese aggression in Asia, unless checked, will wipe out American trade in China. The United States has refrained from sharp action till now, partly because Japan has represented itself (as in Matsuoka's recent visit to Washington) as the bulwark against Bolshevism in Asia.

The reversal of many traditional policies of the American Government by Roosevelt under the stress of present conditions may include recognition of Soviet Russia as an actual fact, with some strong qualifications regarding propaganda.

In the opinion of competent observers, close to authority, there is a strong possibility of recognition, growing out of the negotiations in progress at the World Conference in London. It is felt that pro-recognition sentiment reached a peak several months ago, and was hurt severely by the trial of the British Metro-Vickers engineers on wrecking charges and by the visit of Matsuoka to Washington. It was delayed by the overwhelming domestic problems of national economic reconstruction, including unemployment, banking reform and control of the currency confronting the American administration.[49]

Garry wondered at the action of the R.K.I. in asking me for a report on such a subject, remote from the technical phases of the construction industry in the U.S.S.R.

"It is strange," he mused, "but apparently you can help us in many ways. Continue with the work. My counsel is at your command whenever you desire it!"

The next days were crowded by the addition to my regular work of preparation of plans for working models of the interlocking blocks, and the drawing up of the patent application. The grave shortage of technical facilities in the U.S.S.R. was shown by the fact that despite the backing of the Revolutionary Council of Labor and Defense in this project, blueprinting equipment and materials were not available. I had to make five copies of each drawing by hand for the Patent Office! Incidentally, these drawings were made with American pencils, on German tracing paper, both of which I had brought from abroad. Judicious distribution of a few

American drafting pencils had made me several friends for life among my technical colleagues.

Soviet pencils are amazingly bad. With the best graphite in Europe, and unlimited supplies of fine lumber, the Soviet factories manage to produce the worst pencils in the world. This is due to failure to grind the graphite fine and uniformly and to season the wood. Instead of letting the wood dry out after manufacture, though the nation suffers from a shortage of oil paint, pencils are enamelled and moisture sealed in. The result is a pencil which cannot be sharpened with the ordinary penknife. It requires a razor-blade. The lead is brittle, breaking constantly, causing a large proportion of waste.

About this time I undertook another task—the supervision of construction of an apartment for Lyons. It was to be on the third floor of a large cooperative apartment house being built for a group of Soviet writers. Months before, I had planned the rooms in the space which Lyons had purchased. These plans had been revised several times, until at last they were what he desired, or rather what Mrs. Lyons desired. Her instinctive feeling for loveliness in a home was infallible.

Many special problems were worked out in the plans. Independent access to the United Press office, which was incorporated in the home, had to be provided. The arrangement of the kitchen and provision of sleeping quarters for the servant were other difficulties. The latter I met by designing the first counterweighted folding-bed in Soviet Russia, in a closet in the large kitchen. Utilizing the considerable ceiling height, I designed trunk racks for storage, which gave the effect of vestibule entrances. All piping and electric wiring were to be concealed, something unknown in Soviet Russia. Pipe-chases and furring are not yet employed there to cover utility services, and electric wiring is run exposed on walls and ceiling.

The administration of the job was tangled and torn with conflicts among the literary leaders. It was subject to the customary inefficient, irresponsible management. The superintendent was changed frequently. Each new one disavowed the acts of his predecessors and was blandly indifferent about the future. Nevertheless, by filing careful, detailed plans with the management, I was able to pin them down to the drawings as conclusive evidence of my instructions.

To permit the use of the living-room and dining-room as one combined chamber on occasion, I designed a large framed opening between

them, hung with two pairs of folding-doors which locked, forming a wall between the two rooms, or folded practically out of sight when it was desired to join the rooms. At first, this was a disturbing mystery to the superintendent. Later, after he had grasped the idea, it was copied by several of the directors of the enterprise for their own apartments, as were other features of my plans.

Lyons had paid for his apartment in full in advance. Withholding of progress payments could not be employed, therefore, to secure effective action. Moreover, he had paid in American money, whereas the other writers were to pay relatively insignificant amounts in Soviet paper currency, spread over a long period of years. The management of the apartment house took advantage of every opportunity to bleed Lyons for more foreign valuta, which they wanted for the purchase of material not obtainable for Soviet currency. All sorts of excuses were invented for extra charges.

My position quickly became that of a watch-dog, ready at all times to defend my friend from these specious claims. The construction schedule was continually disrupted by lack of material, labor and money and by changes in the supervisory force. Work would be started in one room, then abandoned after a few hours or days and the labor diverted to other tasks.

My specifications called for a smooth-finish, plastered wall to provide a good base for the application of oil paint. Lyons agreed to purchase the oil paint himself instead of using the kalsomine finish which was to be provided for the apartments. I made every effort to have the work pushed during the fine season so that there would be ample time for the plaster to dry and the paint to be put on while the weather was still warm and the air free from dampness. Despite this, delay after delay was incurred. Weeks passed fruitlessly with little work accomplished.

I had designed cabinets for various rooms which could have been built while the other construction was held up. The completion date for the job had been fixed for November, 1932, then for the first of January, 1933. It was already six months overdue, and was not in fact finished until 1934—when Lyons was departing and no longer needed it!

Every obstacle was thrown in the way of securing a proper wall finish. Finally it was agreed by the management that a test section would be put on. If approved by me, it was to serve as a standard for the rest of the apartment. I usually visited the job every two or three days, which was sufficient to watch every step, because progress was so slow. The job

management had agreed to notify me when the sample wall section would be ready for inspection. Five days passed in which no word came. I then decided to visit the building.

When I arrived I found that all the plastering throughout the apartment had been completed! A large gang had been put on and the job rushed through! It was abominable work, showing the haste in which it was done. The surface was rough and uneven, exactly what I had been at such pains to avoid. It was utterly unacceptable. I condemned the work on the spot and ordered the walls scratched with a rake to furnish adhesion for a new finish. Then I telephoned Lyons to come to the building at once.

My action in condemning the work was unheard of. There was no precedent for rejection of poor workmanship, so accustomed had everyone become to bad quality and low standards. Some of the officials of the cooperative were well-known literary figures of the Soviet Union. Despite their consciousness of attempted fraud, they could not believe my sharp order.

Lyons soon arrived. He was shocked to see the work and was especially hurt at the deception by his Soviet literary colleagues, whom he had regarded as friends and upon whom he had showered hospitality and aid.

Mild and long-suffering, however, Lyons attempted to smooth the situation over. He was willing to compromise the matter in some way. I warned him that this would not be possible, since the inferior workmanship, the rough finish, and the use of cement in the plaster surface would cause the destruction of the paint later on by combined chemical and physical action. He finally realized the seriousness of my caution and took a firmer stand. After a sharp altercation with the management, he demanded that the walls be refinished as I had ordered.

The management finally capitulated. Again it was agreed that a small section would be completed, according to my specifications. When satisfactory and approved, it was to be used as a standard for the rest of the apartment.

Several more days passed. One afternoon, Lyons was called to the building by the management. They asked him to come alone. Before he left his office, however, he telephoned me to join him on the job. He was met at the building by the managers, who attempted to dissuade him from my recommendations. They insinuated that I was unfamiliar with Russian conditions. I required impossible things, they said. Lyons re-

mained adamant in his demand for fulfillment of my specifications. The management then admitted that what I required could be done, but they claimed it would be expensive. They would be forced to charge Lyons a considerable amount of extra money, they said.

Just at this point, I entered the office. The managers were greatly embarrassed. Lyons told me in a few words what had occurred. I surveyed the group, angrily.

"All of you knew my instructions," I said. "You agreed to them. This trouble arose because you wilfully violated them. I warn you that no cheating will be tolerated. I know all the tricks. I see them a hundred times a day. The bad work you did will have to be corrected. There is no alternative and there will be no extra payments!"

The management saw that the extortion game was up. A room was selected for a sample wall treatment. Again I outlined the process of finishing the wall to smooth the surface. They agreed to begin work the next morning.

Zara Witkin, from the University of California yearbook, the Blue and Gold ,

1921. This is the only photograph I was able to obtain of Witkin. Courtesy of

The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Emma Tsesarskaia in The Quiet Don , 1931. Courtesy of Emma Tsesarskaia.

Emma Tsesarskaia, 1930s. Courtesy of Emma Tsesarskaia.

Eugene Lyons, late 1920s. At right, Ella Wolfe; at left, Bessie Weissman. Courtesy

of the Hoover Institution Archives, Bertram Wolfe Collection.

Romain Rolland (left) and Maxim Gorky, 1934. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque

Nationale, Paris.

Soviet antibureaucratic cartoon. The caption reads, "At the Northern [Shipbuilding]

Wharf." The chef is labeled, "The Factory [Trade Union] Committee."

The dishes, from left to right, say, "We promise to improve the food";

"We promise to strengthen sanitation"; "We promise to repair the cafeterias."

From Leningradskaia pravda , 23 August 1933.

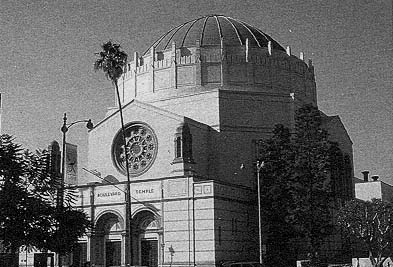

The Wilshire Temple in Los Angeles, whose construction Witkin directed shortly

before his trip to the Soviet Union. Courtesy of Jeffrey Pott.