6.

Suppression by Church and State

Over the first year the vicar general marked his distance from the visions and successfully turned public opinion against them. Then the governor investigated promoters for conspiracy and dispatched some seers to a mental hospital. Finally the bishop decreed the visions devoid of supernatural content. Government persecution brought the believers together. Diocesan persecution split them apart. Relations between promoters, between seers, and between promoters and seers were strained to the breaking point. Visions of the devil and accusations that visions were diabolical mirrored these strains. The bishop eventually singled out the two most visible promoters, Raymond de Rigné and Padre Amado de Cristo Burguera, for special treatment.

The Vicar General

The visions at Ezkioga took place at a time when the church in Spain in general and in the Basque Country in particular was on the defensive. Visions began after the expulsion of the bishop and the burning of churches

and convents. They reached a peak during the discussions leading to the separation of church and state in October 1931. And they flared up again in the spring of 1932 as the government removed crucifixes from public buildings and disbanded the Jesuits. The church's vulnerability during this period may help explain why the hierarchy tolerated the visions for so long and why ultimately it suppressed them with such vigor.

While the bishop of Vitoria was in exile, the vicar general took charge of the running of the diocese. Elderly priests remember Justo de Echeguren for his rectitude and tell me he was an Integrista with friendly contact with the Basque nationalists. Some emphasize his diligence and activity, others his humaneness, studiousness, and intelligence.[1]

Justo Antonino de Echeguren y Aldama, born 1884 into a wealthy family of Amurrio, ordained 1907, doctor at Gregorian University in Rome, licenciado in law at the University of Valladolid, secretario de cámara under Bishop Leopoldo Eijo y Garay of Vitoria and vicar general under Mateo Múgica from 1928 until becoming bishop of Oviedo in January 1935. Opinions from Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 7 April 1983, pp. 1, 8-9; G. Insausti, Ormaiztegi, May 1984; Barandiarán, Ataun, 9 September 1983, p. 3.

He allowed Antonio Amundarain to organize the visions at Ezkioga for the first few months, as long as Amundarain did not say where he obtained his authority. Waiting to see what would happen, Echeguren did not stop priests from leading the rosaries at the ceremonies or Catholic newspapers from reporting the visions in detail. He had regular channels for making his wishes known to the Catholic press, and El Día, the newspaper of his protégé, gave the visions the most coverage of all.[2]The diocesan press delegate, José María de Sertucha, had the bishop's entire confidence.

Much of this news was favorable. In July, August, and September 1931 the Catholic press throughout Spain liked the outpouring of piety at the visions. Leftist newspapers did not make an issue of the matter. When the deputy Antonio de la Villa protested in the Cortes, Manuel Azaña, then minister of war, thought him vulgar, and other deputies, including the philosopher Miguel de Unamuno, thought him ridiculous. The minister of the interior pointed out that the French republic tolerated Lourdes and an entire district lived off the popularity of the site. The political slant of the visions in late July did not reach the press, so they did not embarrass the diocese.[3]

De la Villa, DSS, 13 August 1931; Maura in El Socialista, 14 August 1931, p. 4. For Azaña the speech was "muy chabacana" (Obras [México: Oasis, 1968], 4:82). On Echeguren's attitude, Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 7 April 1983, pp. 15-16.

Echeguren maintained one consistent policy—he deprived the vision prayers of the legitimacy that external Christian symbols would have provided—but otherwise he underestimated the depth of public interest and the potential of the visions for disruption. When his friend and protégé Pío Montoya called him urgently on the evening of Ramona Olazábal's wounding, Echeguren refused to go to Ezkioga because he had to adjudicate a marriage annulment proceeding. Only Montoya's excited insistence brought him on the morning train. At Ezkioga he dealt with Ramona expeditiously and decisively, but by his own admission he had come with his mind open to the possibility that here at last was the confirming miracle.

As a result of Echeguren's press release against Ramona, El Día stopped reporting on the visions and Rafael Picavea thereafter prepared his entertaining articles for El Pueblo Vasco . About this time the vicar general forbade priests to lead the rosaries and ordered the seer Patxi Goicoechea to take down the vision stage. But not until Carmen Medina and the seers went to see the exiled Bishop Múgica in France in mid-December 1931 did the vicar general and the bishop

choose to go on the offensive. By then Rigné had published his defense of Ramona and had shown Múgica photographs, and Catalan gentry had accompanied José Garmendia to see the vicar general in Vitoria. There was lobbying as well from Bishop Irurita of Barcelona. The leaders of the diocese of Vitoria now realized that the seers would not stay home and their supporters would not stay quiet.[4]

On the rosaries the directive was unpublished; see BOOV, 1 May 1932, p. 264; Echeguren, notes to Laburu, spring 1932; and L 14. Cardús wrote Ramona, 9 March 1932, that Irurita intervened "hace tiempo" (some time ago).

When Patxi announced a miracle for December 26, the bishop sent his fiscal to Ormaiztegi to expose and discredit the seers in general. Such predictions, coming in a series of relays, had been maintaining the hopes of believers from the start of the visions. José María de Sertucha took testimony from Carmen Medina, Rigné, Ramona, Evarista, and Patxi about the prediction. By then Patxi had amended the date to a month later. The day after the Sertucha mission the vicar general prohibited all priests from going to the vision site. He asked the Jesuit Padre Laburu to reason with an industrialist in Bilbao, Manuel Arriola, who supported the visions. The industrialist promised to stop going to Ezkioga if the miracle did not occur in January.[5]

For Sertucha see R 41; Boué, 69; Juan Celaya, Albiztur, 6 June 1984, p. 29. Rigné's private life was at issue as well, perhaps because he was seen as aggravating the situation. BOOV, 1 January 1932, p. 6, and 1 May 1932, p. 263; Echeguren to Laburu, Vitoria, 20 January 1932.

The Jesuit Expert, José Antonio Laburu

Forty-eight years old, José Antonio Laburu was then at the height of his popularity as one of Spain's most eloquent preachers. He was also a kind of popular scientist whose specialties in 1931 were "psychology, psychobiology, and characterology." He gave lectures to audiences in the thousands, with simultaneous radio broadcasts, on subjects that ranged from morality on the beaches to the psychology of fighting bulls. His oratory was "eminently popular, attractive, full of overwhelming conviction, within reach of the illiterate worker as well as the university professor." He taught biology at the Jesuit school in Oña (Burgos) and traveled widely the rest of the year. In 1930 many of his thirty-seven lectures were in Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay, to audiences top-heavy with university, government, and military leaders. His psychology leaned more to the Germanic than the French, but he was dismissive of Freud and occasionally cited Pierre Janet. In the ecclesiastical firmament, he was a very bright star. Oña was close to Vitoria and Laburu had fluid relations with the diocese. In Holy Week of 1930, according to the diocesan bulletin, his spiritual exercises in San Sebastián "were the sole topic of conversation in cafés and workshops, factories, and offices."[6]

Profiles in Estrella del Mar, 8 November 1931, p. 457, and Caro Baroja, Los Baroja, 274-275; oratory description from El Debate, 24 March 1933; for his psychology see Laburu, Psicopatología; BOOV, 1930, p. 372. From April to July 1932, in addition to his Ezkioga lectures he gave at least eight in Bilbao, Vitoria, and San Sebastián on childhood education, the psychology of children, wealth and social justice, and the psychology of Ignacio de Loyola. One in San Sebastián, held outdoors, attracted eleven thousand persons.

Apparently Laburu's natural curiosity led him to try to capture the experience of the visionaries on film, perhaps as material for his lectures. He first went to Ezkioga with a priest from San Sebastían on 17 and 18 October 1931, just after Ramona's wounding, when he filmed Ramona and Evarista Galdós. Evarista, he said, obligingly rescheduled her visions to midafternoon so there would be enough light.[7]

Laburu's family also went to Ezkioga and his mother wanted to know his opinion (letter to Laburu after 8 February 1932).

He returned to Ezkioga around January 4 to show the films to theseers and their friends. On the next day he filmed some more, in part at the request of the seers. This time he included Benita Aguirre, who also rescheduled her visions for him. Skeptical from the start and perhaps inspired by the photographs of religious hysterics in books by Janet and other French psychologists, he intended to compare the seers to mental patients. Seers and believers considered his presence a good sign. They still hoped for a favorable verdict. After all, Bishop Múgica had treated Rigné, Carmen Medina, and the sample seers gently; and even the vicar general's delegate Sertucha had been convivial while drawing up his affidavits.[8]

The priest José Ramón Echezarreta, brother of the owner of the apparition site, thought Sertucha's questions were part of the approval process, whence the prohibition of priests at the site, "a measure used first at Lourdes and lately at Fatima." At Ezkioga he had seen Laburu's films, "which provided us with a most agreeable moment" (to Cardús, Legorreta, 4 January 1932).

In the first months of 1932 activity picked up at the apparition site. The nonstop stations of the cross proved attractive not only to the Catalans but also to the Basque and Navarrese. The removal of crucifixes from public buildings helped focus attention on the living crucifixes at Ezkioga. The Rafols prophecies fed this enthusiasm. Echeguren needed a master stroke, so he asked Laburu to give a series of public lectures critical of the visions. At the beginning of April he sent Laburu the evidence he had against content of the visions and the seers' conduct. Since much of this was rumor and some of it actionable, Echeguren specified what Laburu could mention but not print and which names he could use. Laburu himself gathered more information from the seers' former employers or skeptics in the Bilbao and San Sebastián bourgeoisie, to whom he had easy access.[9]

For activity in early 1932: ARB 20-21; Romero, "Comunicado"; "Vuelve la afluencia de gentes a Ezquioga," LC, 9 February 1932, p. 1; Andueza, LC, 11 March 1931. The high point was Holy Week, with buses from Pamplona, VN, 24 March 1932, p. 2. Early in April Echeguren succeeded in getting Patxi, through an Ataun priest, to take down the stations of the cross he had put up in February (Echeguren to Laburu, 13 May 1932); note in ADV Varios file, 1927-1934, for Echeguren's measures. Echeguren wrote to Laburu regarding the talk on 3, 13, 15, and 18 April 1932.

The Vitoria vicar general hoped that Laburu's first lecture, in the seminary in Vitoria, would serve to disenchant those professors, parish priests, and seminarians who believed in or were confused about the visions and persuade influential laypersons then providing moral and logistical support to the seers. Echeguren posted the parish priest of Ezkioga at the door to keep the seers out.[10]

The seminarian Francisco Ezcurdia (9 September 1983, p. 5) originally had been assigned the task of excluding the seers.

Both in its debut on April 20 and in repeat performances at the Teatro Victoria Eugenia in San Sebastián on 21 and 28 June 1932 Laburu's lecture against the "mental contagion" at Ezkioga was a devastating success.[11]

As far as I know, Laburu never published the complete lecture. In the archives at Loyola are three texts, one handwritten, undated, with corrections by another hand, possibly that of Mateo Múgica; I use, citing as L, a forty-page, double-spaced typescript of the same text; there is also a French translation. I have listed some newspaper reports under Laburu in the bibliography. The best is that by José Miguel de Barandiarán in the seminary's student magazine, Gymnasium. That of GN was reprinted in BOOV, CC, and Semanario Católico de Reus. There were short summaries in Easo, EM, and La Verdad of Pamplona. The June 20 lecture, which had new details and was more combative, is reported best in PV.

With daunting theological and psychological vocabulary, Laburu laid out the characteristics of true visions, citing Thomas Aquinas and Teresa de Avila, and showed how those at Ezkioga did not measure up. Rather, he said, they were purely natural, if unusual, mental processes. He went down a list of aspects that disqualified the visions:1. The seers' certainty about when their visions would occur. They had a special stage and they could have their visions virtually at will. He cited in particular the behavior of Ramona, Evarista, and Benita from the time when he made his films.

2. The childishness of what the seers asked about and saw. He cited their asking whether the duke of Tárifa would survive an operation and whether

various relatives were in purgatory. He mentioned visions in inappropriate places, visions of persons in hell or heaven or still alive, visions of the devil making faces at Benita through a bus window, visions of the Virgin walking through a house in Ormaiztegi and blessing the rooms, and visions of divine figures with the wrong attributes (Jesús Elcoro allegedly described the Virgin Mary with a Sacred Heart of Jesus pierced with a sword). And he referred to "the alleged delivery of medals, ribbons, rosaries, without any purpose other than the gift of these objects to 'seers' whose spiritual life was an open question."[12]

L 11.

3. The falsity of what the apparition was supposed to have said. His examples: the Virgin said she would not forgive those who did not believe in Ezkioga, whereas the church did not require belief even of "approved" apparitions; a seer saw someone in purgatory who was actually alive; and a seer said that Carmen Medina's brother-in-law would survive, though he did not.

4. The behavior of the seers before and after the visions. Here Laburu referred, at least in his unpublished text, to the reputation of Patxi and Garmendia as drinkers; to Ramona's dancing soon after her wounding; to the seers' showing off in gestures, photographs, and on film; to boasts as to the length of time in trance; to female seers being alone behind closed doors with male seers or believers; and to male seers kissing female believers.

5. Obvious frauds: Ramona's wounds and rosary; a false report in a Catalan newspaper.

6. "The total absence in the 'seers' of supernatural behavior, whether in (1) humility; (2) recollection; (3) prayer; (4) penance; or (5) obedience; and their distinguishing themselves by overt exhibitionism, utilitarianism, and dissipation."[13]

L 13.

He also remarked on a kind of habitual dullness (abobamiento ) on the part of several seers caused by their repeated trances.7. "The enormous emotional pressure on the seers to have visions." Here he mentioned as examples: that believers gave slickers, shoes, stockings, and wool socks to Ramona and Evarista; that Carmen Medina took the girl from Ataun to live with her; that believers admired or praised the seers as if holy and asked them to pray for people; that believers kissed Patxi; that believers offered Patxi the use of automobiles; and that the seers gave the general impression of being on holiday.

Finally, in a kind of catchall category, Laburu cited the refusal of the seers to remove the cross and the stage; the scheduling of apparitions of the Virgin at ten o'clock at night or later, "an hour at which it has been the prudent and traditional custom of the church to suggest that young women should be in their houses" (what can happen at these gatherings, he added darkly, is obvious); and the repeated announcements of extraordinary events for all to see, none of which had occurred.[14]

L 15.

Although the Jesuit referred favorably to the public display of faith at Ezkioga, he warned that people could not deduce from this piety that the visions were supernatural. He distinguished "a true faith, solidly reasoned and cemented, a faith instructed and conscious," from "faith of pure emotionality or family tradition [held by] sentimental and mawkish persons who confuse secondary and unimportant things with what is essential and basic in dogma." After reviewing diocesan policy in regard to Ezkioga, he emphasized that the diocese had made no formal inquiry because there was no trace of the supernatural to investigate. Finally he showed his films of the seers and compared them with a film of patients in insane asylums.[15]

L 18-19. In Laburu's films at Loyola I did not find those from Ezkioga.

Laburu stayed at the seminary in Vitoria and made himself available to answer individual questions or doubts of the professors and seminarians. One professor had brought back a blood-soaked handkerchief from Ramona's wounding. The seminarians were divided. Attitudes of the clergy in the zone around Ezkioga ranged from tenacious opposition to tacit approval.

But Laburu convinced many. Francisco Ezcurdia was then a seminarian and had been a frequent observer of the visions. The Rignés lived in his parents' boardinghouse in Ormaiztegi in the winter of 1931–1932. He had been especially puzzled by the case of an acquaintance, a cattle dealer from Santa Lucía whom María Recalde repeatedly tried to see. The man did all he could to avoid her, but she finally caught up with him and told him a secret about himself. The event so changed the dealer that thereafter he received Communion daily. Through his teacher José Miguel de Barandiarán, Ezcurdia asked Laburu how this knowledge of conscience was possible. Laburu's commonsense response was that there were other, natural ways, such as gossip, to find out people's sins. Ramona's spiritual director also had a chance to consult Laburu personally. He too was convinced by the Jesuit, if only temporarily. Another priest who was a seminarian at the time told me that although he personally found Laburu's talk superficial and pseudoscientific, it convinced the other students.[16]

Francisco Ezcurdia (1908-1993), Ataun, 9 September 1983, pp. 5-6; for Ramona's spiritual director: Ramona to Cardús, 6 June 1932; for convincing of seminarians: Daniel Ayerbe, Irun, 13 June 1984, pp. 4, 7, who did not, however, support the visions.

Laburu's impact went a far beyond the seminary. Major regional newspapers repeated his main points. So did local periodicals in areas where there were supporters of the visions, like a Basque-language weekly in Bizkaia and the parish bulletin of Terrassa in Catalonia. El Matí, at first enthusiastic about Ezkioga, by then opposed it. Even El Correo Catalán summarized the talk. It was clear that Laburu spoke for the diocese, and his lecture permitted priests and laypersons opposed to the visions to speak out. And the lecture changed the minds of many believers, like the priest of Sant Andreu, in Barcelona, who in his parish hall spoke first in favor of the visions in December 1931 and then, on the basis of Laburu's lecture, against them six months later.[17]

Basque-language weekly: Ekin-Jaungoiko-zale, 30 April 1932, p. 3; Full Dominical (Terrassa parish bulletin), 5 June 1932; La Verdad (Pamplona parish bulletin), no. 36; Joan Colomer i Carreras to Cardús, Barcelona (Sant Andreu), 10 May 1932; SC E 476-480.

Among Ezkioga enthusiasts the lecture provoked consternation, disillusionment, and anger. For those whom the visions touched in a personal way or who felt that they were witnesses to miracles, Laburu's arguments were thin stuff.

Only greater miracles could have persuaded them to disavow the seers. The rector of Pasai Donibane warned Laburu not to give the lectures in San Sebastián.

You have no right to come and play the Vitoria phonograph record as if we the priests of Gipuzkoa could not demand more respect for matters related to the Mother of God…. If your reverence wants to preach in a theater, preach against the terrible torments that in hell await those who adore the flesh, but let Most Holy Mary appear to whomever she wishes at Ezkioga, although she did not appear to your reverence who went to Ezkioga with a movie camera.

Never shy about writing anyone, Rigné asked Laburu to study the problem with greater care, rebutted specific points regarding Ramona and Evarista, and informed the Jesuit that "the Most Holy Virgin spoke to me herself at Lourdes last August 9, the feast day of the saintly Curé d'Ars for whom I have a special devotion. She entrusted me with a certain mission and now I know why." In the same vein a Catalan pharmacist informed Laburu of an Ezkioga spring that allegedly went cloudy when an unbelieving soldier approached it. In sizzling terms an art restorer from Vitoria denounced "official science and the pedantry of this collection of dolts with pretensions of wisdom who monopolize the diffusion of knowledge they do not possess." He blamed Laburu and the diocese for not orienting the seers from the beginning and then making fun of them for being disoriented.[18]

For Pasaia rector, Pedro Gurruchaga to Laburu, San Sebastián, 18 June 1932; Rigné to Laburu, Ormaiztegi, 26 June 1932. Three days later Rigné in Llamamiento denounced the vicar general for opposing the apparitions, for using Laburu as his pawn, and for presenting the bishop with a fait accompli. Pharmacist Gonzalo Formiguera Hernández to Laburu, Barcelona, 29 April 1932; art restorer Pedro María Lage to Laburu, Vitoria, n.d.

Ezkioga believers were not the only ones upset by the speech. The novelist Pío Baroja's sister had gone to Ezkioga from Bera and returned impressed with the piety. Baroja thought it ridiculous that Laburu should adduce proofs against the seers, and he said so in a shortbook, Los visionarios: "The exact measurement of a miracle is sort of thickheaded. The only ones who would think of that are these poor Jesuits we have now, who are pedantry personified." His nephew later wrote, "Everyone knew that my uncle did not believe in miracles; but in that case, as in others, what irritated him was the pseudo-positivism of those who denied them, not the denial in itself."[19]

Baroja, Los Visionarios, 539, and similarly, for Ezkioga and Limpias, El Cura de Monleón, chap. 21; Caro Baroja, Los Baroja, 275.

After the first talk in San Sebastián, the Ezkioga parish priest, Sinforoso de Ibarguren, wrote to Laburu that he had stirred up a hornet's nest.

You must surely be tired of having hot ears, as they say; this is inevitable after the storm you have raised with your talk. The Ezquioguistas are of course infuriated. Even the farm folk have heard about the lecture and comment on it. And the Catalans tear into you on every occasion. They would skin you alive.

Ibarguren ended with a thought about the long-term consequences: "Church authority comes out of all this badly shaken. Great damage is being done; how will it be repaired?"[20]

Sinforoso de Ibarguren to Laburu, Ezkioga, 27 July 1932.

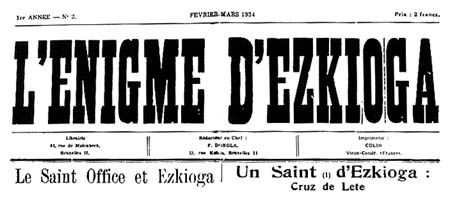

Cover of pamphlet by Mariano Bordas Flaquer

defending apparitions, published October 1932

Because Laburu was so effective, believers scrambled to find a priest to counter his arguments in public. Some asked a learned Carmelite, Rainaldo de San Justo, which worried the vicar general enough for him to contact the Carmelite provincial in Bilbao. The provincial reported that Padre Rainaldo said he would not speak unless his superiors in the order and the diocese asked him to. With the diocese thus on the alert, the rebuttal could come only in print. Mariano Bordas Flaquer was one of the leaders of the weekly Catalan trips. A lawyer, former member of parliament, and former assistant mayor of Barcelona, Bordas had led a pilgrimage to Limpias in 1920. In June 1932 he prepared a series of articles refuting Laburu. The diocese of Barcelona approved the series for El Correo Catalán, but for some reason the newspaper did not publish the articles. Burguera added a preface that gave Bordas some theological legitimacy, but The Truth about Ezkioga did not come out as a pamphlet until October 1932.[21]

For P. Rainaldo see B 137, 288; and the Carmelite provincial Ecequiel del S. C. de Jesús to Echeguren, Bilbao, 20 June 1932; and see chap. 8 below, "Religious Professionals." For Limpias see Diario Montañés, 6 November 1920, p. 2.

Bordas distinguished seers who were true, naming ten Basques and the Catalan seers in the weekly groups, and others who, he admitted, were not. But he denied that the great majority of seers asked childish questions or had visions at any set time. He explained the vision messages containing errors in dogma as misunderstandings on the part of seers or mistakes in copying. He accused Laburu of slandering the seers but said that in any case their behavior before and after the visions was irrelevant to the truth of the visions themselves. He argued that even if there were seers who said someone alive was in purgatory this would not disqualify the others.

As proofs for the visions he gave the seers' clairvoyance, their knowledge of unconfessed sins, and their conversions of sinners. He adduced three instances of the seers' preternatural knowledge: a seer's answer of a Catalan youth's unspoken question about the fate of his mother; Benita Aguirre's and María Recalde's knowledge of the pious death in Extremadura of a Catalan's relative; and María Recalde's reply in vision to an unread, carefully folded, query.

As their popularity and even their respectability melted away, the seers reacted in their own way against the lectures. Already before the first lecture, Garmendia had worried about its effect. According to a visitor, in the week after the Laburu talk the only people around Ezkioga who believed in the visions were Joaquín Sicart the photographer, the Zumarraga hotel owners, the taxi drivers, and some of the inhabitants of the Santa Lucía hamlet. Benita Aguirre wrote plaintively that in her town of Legazpi "no one believes; almost all have grown cold."[22]

For Garmendia, SC E 421, 17 April 1932; for effect of Laburu lecture: Joan Colomer i Carreras to Cardús, Barcelona (Sant Andreu), 10 May 1932, and Benita to García Cascón, Legazpi, 22 May 1932, in SC D 111.

María Recalde told her Catalan friends that two weeks after his lecture in Vitoria Laburu called her to a convent in Durango and reproved her for sending him a disrespectful letter. Feeling divinely inspired, she allegedly rebuked him for making Christ suffer on the cross during his talk, and what she said led Laburu to renounce the lectures planned for San Sebastián. Since he subsequently gave them, the account is of dubious accuracy. But it captures the depth of the seers' distress.[23]

The meeting, described in a letter from Cardús to Pare Rimblas, 17 June 1932, and ARB 73-74, allegedly took place May 5 with Franciscan nuns as witnesses.

After Laburu spoke in San Sebastián, the Virgin supposedly told one seer that he was a sinner and another that in the end he would change his mind. Subsequent rumor among seers and believers had it that Laburu had a cancer of the tongue as punishment, that he wanted to retract what he had said and to study Ezkioga seriously. In visions in 1933 Benita Aguirre and Pilar Ciordia said the Virgin gave messages for Laburu to mend his ways and help Padre Burguera with the book. But this was all wishful thinking.[24]

For Laburu as sinner, Juana Aguirre vision, 28 June 1932, in Boué, 78; for change of mind, Evarista vision, 29 June 1932, in B 334 and 721; on cancer, Boué, 97, and EE; dismissed by Múgica in BOOV, 15 March 1934, p. 245; Benita Aguirre, n.d, B 592, and 5 June 1933, B 494-495; Pilar Ciordia, 14 July 1933, B 691.

The Governor

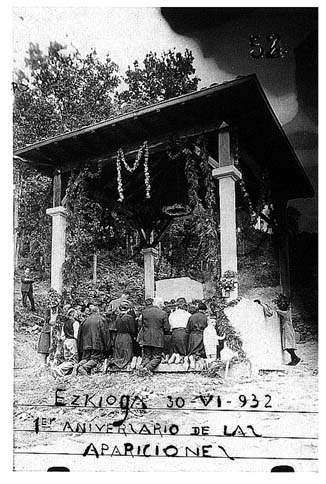

Seers and believers now worked with a new urgency to dignify their holy place. The vicar general denied permission repeatedly for a chapel, and the

Chapel virtually completed for the first anniversary

of the apparitions, 1932. Photo by Joaquín Sicart

lectures showed that he had made up his mind. So finally, following José Garmendia's inspirations, Juan José Echezarreta started building the chapel anyway. Vigilant to the point of obsession, the Ezkioga pastor notified the diocese at once, and in an official note on June 10 the vicar general prohibited the chapel. Echezarreta pushed ahead and by the end of the month the chapel was virtually complete. Garmendia also described the image in detail; an artist sketched it in his presence, and a sculptor in Valencia, José María Ponsoda, prepared the image. Again Echezarreta footed the bill. The parish priest must have been suspicious about the large pedestal, often wreathed in flowers, waiting in the structure.[25]

Echeguren notes to Laburu, spring 1932; ARB 24-25; Echeguren, BOOV, 15 June 1932; the vicar general's note was in ED, LC, and EZ on June 16. In the summer of 1932 some priests forbade their penitents to go to Ezkioga, but this was not a diocesan policy. Garmendia had a vision on August 19 and 20 in which the Virgin said that priests could not keep properly dressed people from going, B 636. For image, B 42, 387 n. 1; the artist was Martí Gras; more in chap. 11 below.

In September 1932 it became clear that the next offensive against the seers would come from the government. In August General José Sanjurjo had led an attempt to overthrow the Second Republic from Seville. Sanjurjo was surprised when the uprising fizzled from lack of support, which he had expected in particular

from Navarra and the north. This was the rebellion that Carmen Medina was sure the Virgin of Ezkioga was announcing in 1931. At that time, when the visions were drawing tens of thousands of spectators, the government had not been worried or at least had not acted. Paradoxically, when the Republic did crack down in 1932, there were far fewer spectators and the visions were much less of a threat. There was no longer the kind of chemistry among newspapers, seers, and social anxiety that a year before had turned seers into political subversives. The difference in the government's reaction may lie in its greater insecurity after the coup attempt or, more simply, in the personality of the new governor.[26]

ARB 151.

Pedro del Pozo Rodríguez came to Gipuzkoa as governor on 20 August 1932 from Avila, where he had been governor since the creation of the Second Republic. Spanish governadores civiles , like prefects in France, are above all in charge of public order and police. During the Republic they were generally young, well-educated members of political parties in the government. Those in the provinces of the north, where the majority of citizens opposed the Republic and the political landscape was as complicated and rugged as the physical one, were men in the confidence of key members of the cabinet. La Voz de Guipúzcoa noted that del Pozo was "bound by ties of close personal and political friendship with [the prime minister] Señor Azaña" and that Azaña had personally briefed him.[27]

VG, 17 August 1932, p. 1.

Just one month later del Pozo served notice in the press on the Ezkioga seers and believers, who had been gathering in greater numbers at the new chapel:

MORE MIRACLES AT EZQUIOGA?

Word has reached the governor's office that there is a renewal at Ezquioga of reactionary religious movements, using as a pretext apparitions recently discredited by an official of the church.

It is surprising after the presidential visit to Guipúzcoa, a visit that was a triumph without precedent, after the approval of the Statute of Catalonia and a renewed governmental interest in coming to terms with the Basque Country, that once more the name of Ezquioga should be heard from the lips of deceivers who with the pretext of the alleged apparitions are undertaking a political campaign.

The governor is ready to act in this matter and will tolerate no more "miracles." Our enemies must play fair. They cannot be allowed to play politics with religious images that deserve their total respect. Seeking to maintain the faith, in fact they destroy and undermine it with their maneuvers.

"As long as I am in this post," Señor del Pozo told us, "I will not tolerate this kind of politics disguised as religion."

Very severe measures will be taken.[28]

Del Pozo press declaration, 21 September 1932, in VG 22 September 1932, p. 5, and widely reported elsewhere. B 268 claimed that the order came from Azaña.

On October 1, ten days after this warning, the Bordas and Burguera booklet on Ezkioga came out, and on October 6 or 7 Echezarreta installed the new image of the Virgin on its pedestal to "ardent tears, continuous prayers, pious hymns,

and fervent applause." All of the slow accretions of liturgical respectability had come to this climax, an image in a shrine, complete with a Way of the Cross on its approach, a holy spring, and a photographer standing by at the foot of the hill.[29]

FS 53; B 42, 379; ARB 27. An eyewitness to the image's arrival by truck (Surcouf, L'Intransigeant, 20 November 1932) wrote that some rural folk expected it to come down from heaven.

The final straw for del Pozo was an incident on a train from Zumarraga to San Sebastián on the afternoon of October 8. Tomás Imaz and two other believers, brothers who owned a bakery in San Sebastián, were returning to the city with the seer Marcelina Eraso. As they prayed out loud, Marcelina fell into a vision. At least one of the passengers began complaining vociferously that Imaz was exploiting the seer, and in San Sebastián police hauled off the little group for disturbing the peace. Dr. José Bago, the head of medicine for the government in the province and a republican hero, examined Eraso and sent her for observation to the provincial mental hospital. The governor reprimanded Imaz and fined him five hundred pesetas.[30]

Marcelina Eraso Muñagorri (b. Arriba [Navarra], ca. 1909-d. ca. 1972). Incident reported on 10 October 1932: VG, p. 7; PV, p. 9; Sol, p. 9; La Vanguardia; and B 379 (wrongly dates it October 7). Marcelina supposedly told a doctor at Mondragón that she saw a serpent around his neck, and he stopped questioning her, for he was living in sin (elderly believer, Ikastegieta, 16 August 1982, p. 2). On October 24 del Pozo released the hospital diagnosis that she had a weak memory and little judgment and was very suggestible (VN, 25 October, p. 6).

Bago, jailed for storming the provincial seat in 1930, had been the subject of a nationwide homage by republican doctors. He was a trusted adviser to governors under the Republic. See C. and J., VG, 2 May 1931; Barriola, "La medicina donostiarra," 39; and Estornés Zubizarreta, La Construcción, 295-296.

The following afternoon Governor del Pozo stopped at Ezkioga to see for himself what was going on. There was quite a crowd, and when Echezarreta came forward, del Pozo ordered him to remove the image by daybreak, to forbid entry to the site, and to take down the souvenir stands. If he did not, the government would dynamite the chapel. Perhaps not understanding the fine points of the matter, del Pozo told him to put the outlaw image in the parish church. He suggested that if Echezarreta wanted to be altruistic he could offer the property for a school. The photographer from Terrassa, Joaquín Sicart, his livelihood in immediate danger, alerted the Catalan supporters.[31]

Unlabeled clipping, 11 October; VG, 3 November; B 379-380; Sicart to Cardús, Ezkioga, 9 October. Strikes closed all San Sebastián daily newspapers from 10 October until 3 November 1932, which facilitated del Pozo's crackdown. The press of Pamplona, Madrid, and Barcelona reported del Pozo's measures in brief notes.

Echezarreta agreed to remove the image, but he had not counted on the opposition of the believers, who swore to defend it. When he returned with workers from his paper mill, there was a tense standoff. Echezarreta paused to pray part of a rosary so as not to offend the Virgin, whereupon the believers declared they would pray fifty rosaries for the Virgin to strike dead the first to touch her. The workmen then refused to help. Burguera intervened to calm things down and persuaded Echezarreta not to remove anything; rather he should let the governor do it. The standoff around the image continued from October 10 to 13 with round-the-clock prayers and visions. Del Pozo insisted not only that Echezarreta take the statue away but also that he raze the chapel and wall off the site. Four seers told Echezarreta from the Virgin that he should not give in. Civil guards protected the workers as they dismantled the stands at the foot of the hill.[32]

B 379-380; ARB 29-30. One of the workers, Juan Benarrás (Ezkioga, 15 August 1982), said the pressure not to act was intense. El Noticiero Universal, 12 October; Ahora, 13 October; VG, 3 November; Sol, 13 October; ARB 31; SC E 481/ 14. Cardús's account of these days is untitled and numbered separately; I have treated it as part of "Engrunes," in which it would follow p. 481.

José Garmendia defended his image and temple as best he could by visiting President Francesc Macià once more in Catalonia. He arrived in Barcelona on October 12, and that evening, in the private chapel of a wealthy believer, he asked the Virgin whether the image was still at the Ezkioga site. He said she refused to tell him in order to spare his feelings. The next day believers drove Garmendia and Salvador Cardús to Macià's country home at Vallmanya in the province of

Lleida. There Garmendia and Macià spoke for about fifteen minutes in the patio. According to Garmendia, Macià said that he preferred not to approach the prime minister, Manuel Azaña, who was a republican of the "red" variety but would speak instead to the president of the Republic, Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, "who always goes to mass," and ask him to intervene "to leave you in peace." Garmendia gave him a photograph of the image and the Bordas pamphlet. That night at Ezkioga about thirty believers and seers stayed with the image. Many but not all present thought they saw the image weep, and at three in the morning they sent for Burguera. He too saw the weeping and drew up an affidavit that those present signed.[33]

SC E 481/ 1-2, 6-7; Cardús to García Cascón, Zaragoza, 13 October 1932. According to Sospedra Buyé, Barcelona, 15 February 1983, García Cascón later gave Macià a replica of the Ezkioga statue. For night vigil see ARB 154.

Cardús arrived the next day just after workmen had removed the statue from the chapel. He just had time to kiss the images of the surrounding angels before the workers took them away. Citing the diocesan ban on objects associated with the visions, Sinforoso de Ibarguren had refused to let the image into the parish church, so the workers had carried it to the nearest farm. They did so reverently, on their knees, praying the rosary to the tears of the onlookers. Shortly afterward, they sawed down the great cross that Patxi had erected a year before, and it broke into pieces as it fell. Many of the several hundred persons present gathered splinters as relics. For the seers and believers, who so often had simulated crucifixion or acted out the stations of the cross, the Passion was taking place yet again at Ezkioga. They saw Echezarreta as a coward and Ibarguren as Judas. Cardús described the fall of the cross with the words of Christ: "Consummatum est, it is finished." Many seers had visions and all of them wept. The believers held continuous rosaries, some fearing divine punishment, others pleading for the Virgin to make herself visible. "In the meantime the blows of the hammers and chisels that began to demolish the building cut into people's hearts." That evening the mayor of Ezkioga announced on behalf of the governor that as of the next day all seers who had visions in public would be jailed. After dinner Cardús returned to find the image adorned with flowers and lit by a multitude of candles. Believers prayed before it in the rain.[34]

Account of events based on SC E 481/ 8-13; Benarrás, 15 August 1982; R 120; and El Debate, 15 October 1932, p. 3. For Ibarguren, DN, 15 October, p. 4. Benita claimed to see the cross falling in a vision in Legazpi (ARB 156). For after dinner, SC E 481/ 16-17.

On October 15, the feast of Teresa de Avila and the anniversary of Ramona's wounds, Salvador Cardús was surprised to encounter his spiritual director, Magdalena Aulina herself. She had come incognito as "María Boada," and with her were José María, Tomás, and Carmen Boada and Ignasi Llanza. Together in the rain they watched the workers remove the iron grille from the chapel. Around noon, on orders from the governor, the workers stopped. Burguera speculated that Macià's intercession with the government had had some effect, but it could also have been the result of the meeting in San Sebastián of Echezarreta, the mayor and town secretary of Ezkioga, and the governor. Nevertheless, civil guards prevented people from going up the hill. Sometime during the day Echezarreta had his workers take the image in a wheelbarrow down to a house on the road and install it in what had been Burguera's room.[35]

SC E 481/ 20-24; DN, 16 October, p. 4; ARB 155-156; B 380, 405. The weekly La Cruz alone questioned the governor, asking on October 16 that the believers be left alone. The house, Kapotegi, belonged to Echezarreta.

The Boada party invited Cardús, Garmendia, and Burguera to lunch in Zumarraga. There Burguera told them that his superior, the archbishop of Valencia, Prudencio Melo y Alcalde, had ordered him to go home. He was not obeying. According to Cardús,

P. Burguera also revealed his contacts in regard to the events at Ezkioga with the papal nuncio, who several times has expressed interest in them, even though he had said he could not intervene in the internal affairs of the diocese. The nuncio had a note given to P. Burguera to pass on with this significant message for Ramona Olazábal, dated 25 July 1932. "Tell Ramona from me to suffer with patience everything that Our Lord God sends her, and if she is innocent He will help her and she will triumph over all ."[36]

I do not know if Tedeschini really said this, and if so, to Burguera himself or someone else, like Carmen Medina, who was in touch with him that summer (B 137; SC E 481/ 25-27 (quote); Burguera to Cardús, 21 October 1932). The message would not have been out of character; witness Tedeschini's informal statement at Limpias in 1921 in Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 79.

On their return to Ezkioga, the party found believers and onlookers had arrived by car and bus and were milling about on the road. The houses along the road were full of believers praying and in almost every one a seer was having visions. A few defied the ban on outdoor visions. The original boy seer had his at the back door, facing the nearby apple trees. Evarista Galdós had hers under apple trees near the road and told Cardús that the Virgin told her to tell Burguera not to worry, that she (the Virgin) would watch over him. To the others she said, "Don't forget that the Virgin has said that there would be martyrs here!" Benita excitedly told José María Boada that she would write him from jail and that the Virgin had told her, "This is the hour of my soldiers." Even though she had met Magdalena Aulina in Barcelona, Benita did not see through the disguise; she even asked to be remembered to her. The guards heard that Patxi had had an outdoor vision and they tried to find him, but he escaped through a house to the hills. Then they tried in vain to locate Evarista, whom Cardús found huddling in a bus, "like a dove waiting to be sacrificed." That evening Burguera and his family were praying before the image and again saw that it seemed to weep, although there was no liquid on it. Burguera pronounced that here was not one miracle, an image weeping, but as many miracles as people who were seeing the image weep, for separate miracles were affecting the eyes of each.[37]

SC E 481/ 28-31, 34-35; ARB 156-157.

To round out this eventful day, around midnight Cardús went with Garmendia to the foot of the hill. Garmendia had had a vision in the afternoon and expected another. Since the houses were all closed for the night, they prayed by the road. Garmendia saw Gemma Galgani and the Virgin. He said the Virgin told him she was happy they had come out so late. As Cardús said good-bye to Garmendia on the dark road, a car went by and they heard one occupant say to another, "Poor man, what a shame!" It was the son of Garmendia's employer in Legazpi.[38]

SC E 481/ 32-34.

The next day the Catalan party, including Magdalena Aulina in disguise, stopped to say good-bye to Burguera and Cardús. They said the rosary, and

Garmendia entered into a lengthy trance in which he described the Virgin, Gemma Galgani, and the devil, who threatened him. Aulina almost gave herself away by pointing and saying, "Look! Our Mother!" After the rosary, pilgrims arrived from Pamplona with a letter from Pilar Ciordia, who claimed that the previous day the Virgin had said to tell Burguera that she was at his side. Burguera pointed out to the visitors that Evarista had said the same thing and that seers regularly coincided in this way. The Boada party left an observer but took Cardús, our witness, back with them to Barcelona.[39]

SC E 481/ 37-38; ARB 162.

The governor opened a judicial inquiry on October 11. Because of the Gipuzkoa newspaper strike, we catch only glimpses of the witnesses. Echezarreta testified on October 14 and October 18. Garmendia, Patxi, the child Conchita Mateos from Beasain, and María Luisa of Zaldibia appeared on October 21. Patxi had a vision before the magistrate, who sent all these seers to the mental hospital. Burguera wrote Cardús theatrically about the catacombs and of "repeating the early days of the church" and forwarded a letter from Garmendia asking further help from Macià.[40]

Burguera to Cardús, 21 and 22 October; B 380; DN, 22 October, p. 3, and 26 October, p. 3; Sol, 22 October, p. 5; Crónica Social, Terrassa, 26 October.

Over the next week the magistrate called Ignacio Galdós, Evarista, Benita, Recalde, Rosario Gurruchaga, and Vicente Gurruchaga. When seers took the train for San Sebastián, small groups of believers greeted them at many stations with flowers. On October 28 del Pozo appointed a trusted republican and fellow Freemason, Alfonso Rodríguez Dranguet, as special magistrate. By then the case centered principally on Burguera and other organizers for "fraud and sedition." This judge saw witnesses for about a month and finally remanded the case to the court in Azpeitia. Believers estimated that thirty to forty persons testified in all.[41]

ARB 161; El Socialista, 9 July 1932, p. 2, and 29 October 1932, p. 6; Sol, 30 October, p. 7; PN, 30 October, p. 3. Dossiers as Freemasons in AHN GC 211/17 and 214/9.

Burguera compiled a list of the magistrates' questions and noted the following themes: how the Virgin looked; how the visions took place; how the visions related to the Republic and if and when anyone sang the royalist anthem, "Marcha Real"; what Padre Burguera's role was; whether the seers gained any benefit from the visions; how the seers and believers organized their meetings and who were the ringleaders; whether they disobeyed church authority; and what the Catalans were up to.

The magistrate and the governor did not know what to do with seers who talked back, fell into swoons, and were ready for the worst. The telling and retelling of the dialogues, however improved or apocryphal, gave the seers an aura of martyrdom. The girls and women enjoyed going beyond the passive role of victims of God to become, like the men, active witnesses against iniquity. The believers appreciated this shift, which was in keeping with the well-publicized imprisonment of women for holding religious processions and returning crucifixes to schools.[42]

B 388-390, a court officer in Azpeitia who was a friend of an Ezkioga believer may have leaked the interview transcripts. Women fined in Viana (Navarra), PV, 9 February; Yécora (Alava), PV, 11 February; women jailed in Salinas de Oro (Navarra), CC, 27 April; women jailed, from El Debate, Casa de Miñán (Cáceres), 27 May, Anna (Valencia), 14 July, San Esteban del Valle (Avila), 30 July, Algemesí (Valencia), 6 November, and Navalperal de Pinares (Avila), 6 December. In Galvez (Toledo) women forced the mayor to carry the Virgin on the annual trip from the parish church to the chapel, LC, 3 April 1932.

The authorities released several seers after questioning them. The judge questioned Evarista on October 26. She claimed later that the Virgin told her what to answer. When the judge asked her whether she had seen a devil, she said

she had. When he asked whether the devil was naked or clothed, she allegedly said, "He was dressed like you." After more questions he let her go. A young woman from rural Urrestilla, Rosario Gurruchaga, seems to have had a fit. After ten minutes only the neighbor who accompanied her was able to unclasp Rosario's hands by touching them with a crucifix. The judge did not commit Rosario either. Benita was euphoric before she went. She wrote García Cascón, "Thank God we are not crazy; knowing this I am ready to go anywhere, as if on a social call. I am so happy I cannot explain it." The magistrate quizzed her on general knowledge, such as the capital of France, and sent her home too.[43]

For Evarista, B 380, 722; ARB 159-160; unlabeled note in the folder "La Persecució governativa," ASC. For Rosario, B 381; ARB 158-159. For Benita, Benita to García Cascón, Legazpi, 24 October 1932. ARB 161-162.

On November 25 Ramona's spiritual director went with her to San Sebastián. This was Ramona's second appearance, and the priest relayed some of the exchanges to Cardús.

Ramona told me that the judge asked her if she sees the Virgin. She said she did. [He asked] at what distance she saw it, was it within shooting range? I think at that moment Ramona had some kind of divine inspiration. She replied that yes, that she saw it close enough to fire on a civil guard, but it was the Virgin. The curious thing about this is that the man who asked this question some days before the Republic was established in Spain killed a civil guard in a riot in San Sebastián.[44]

Francisco Otaño to Cardús, Beizama, 26 November 1932.

The Catalans heard that when the judge asked María Recalde if she had lost any weight on her repeated trips to Ezkioga, she said she had. Portly like her, the judge said that maybe he too should go. She told him it would do him good—his body would lose weight and his soul would gain it. Allegedly via a vision on October 22 Recalde was sure that Justo de Echeguren was behind the government offensive.

Judge: What did the Virgin tell you about the Republic?

Recalde: She told us nothing.

J: But she must have said that now we are worse than before.

R: No. Before you acted against the clergy; now it is the clergy that has gotten you to act against us.

J: who told you that?

R: I have my sources.

J: Well, the vicar general told me he would not tell anybody.

In Burguera's account she went on to say that she laughed at her accusers, that she feared her heavenly judge, not the earthly one. She spent a night in a holding cell and went on to the mental home.[45]

ARB 159; first two questions and answers from Cardús, "La Persecució," ASC; B 391.

Burguera, the big fish, was called to San Sebastián on November 3 along with José Joaquín Azpiazu, the justice of the peace in whose house he was staying.

Burguera claims that the court typist told him that three priests from around Ezkioga had already been there to testify against him. The governor held Burguera responsible for the resurgence of the visions in the summer of 1932 and thought he had "manipulated people who were mentally ill in order to maintain the fiction of the visions." He said Burguera had "created more seers, held clandestine meetings, and organized apparitions, in some cases where the Marcha Real was played during the visions." He therefore jailed Burguera, releasing him seven nights later on condition that he leave Gipuzkoa. By that time the press had held Burguera up to ridicule. El Socialista of Madrid printed a satirical poem "The Last Miracle-Worker," which referred to "Padre Amado," who first lost his license to say mass "because he wanted to do miracles on his own without the permission of the holy mother church" and then was "thrown in the clink" for conspiring against the government.[46]

For arrest B 68-69, 393-398; VG, 3 November 1932, p. 7; and on 4 November 1932; DN, p. 3; VG, p. 4; PV, p. 3; LC, p. 3; Sol, p. 1. Next day: La Vanguardia, and Moya, El Socialista. Mariano Bordas interceded with the governor of Gipuzkoa for Burguera, who defended himself in PV, 2 December 1932. Azpiazu was accused of holding clandestine meetings in his house.

Shortly after the governor released Burguera, the mental hospital released the seers, virtually all with a clean bill of health. Recalde had visions there, convincing some of the nuns who were nurses. Catalans from the Aulina group had gone to intercede with the staff. Del Pozo fined five prominent believers a thousand pesetas each, substantial sums. He told the press he had received a letter from Navarra saying that a female seer saw devils dragging his soul into hell. After he was transferred to the province of Cádiz on December 7 the government left the seers alone. Civil guards stopped patrolling the site in late November because the towns could not pay them.[47]

Garmendia's certificate of sanity circulated among believers (AC 409). He and others were let out November 13. Recalde in ARB 162-164. Del Pozo in Noticiero Bilbaino, 30 October 1932, p. 3, and PV, 4 November 1932, p. 3. His downfall came when civil guards massacred villagers at Casas Viejas in Andalusia. Ezkioga believers noted that Casa Vieja in Spanish means Echezarreta in Basque (ARB 165-166). For the new governor, Jesúus Artola, B 403-404, 710; SC E 504-505; R 31.

Like Recalde, the other seers and believers were convinced the diocese was behind the government's actions, something Bishop Múgica vigorously denied. A more elaborate theory was that the diocese sponsored the Laburu lectures in exchange for the bishop's return from France. Múgica entered Spain on 13 May 1932 through the intercession of Cardinal-archbishop Vidal i Barraquer and of the nuncio with Prime Minister Azaña. But he could not go back to his diocese of Vitoria for a year, and it is unlikely that Ezkioga, after 1931 a negligible threat to public order, had anything to do with his return.[48]

The vicar general's inactivity was anomalous, given his swift reaction to other images in the past. Múgica entered the diocese 11 April 1933; his denial of a role in del Pozo's campaign in BOOV, 9 March 1934, pp. 241, 245.

Padre Burguera in Charge

Burguera's imprisonment consecrated him as the defender of the seers. Benita had a vision that he would be a martyr, Patxi said the Virgin had a crown for him, and Garmendia said the Virgin called Burguera "your apostle." When he got out of jail, Burguera seems to have concentrated on finishing his book, and he went at once to Barcelona for copies of the Catalans' documents of cures and predictions. A month later, in mid-December 1932, he took his manuscript to a bishop he thought would be sympathetic, probably Luis Amigó of Segorbe. On 1 April 1933 he found out that the diocese would not give him permission to

publish, and a month later the seers had visions that he should print the book anyway.[49]

Visions about Burguera, Benita, November, SC D 119; Patxi's declaration, 4 December 1932, ASC; Garmendia, 19 December, B 638; cf. visions of Ińes Igoa and Evarista in B 622-623. Burguera was in Barcelona from 16 to 20 November 1932. He saw a bishop December 12 and March 21 (B 323). Vision to publish anyway, Evarista, 1 May 1933 (B 723); see also Ciordia, 4 April (B 684), Evarista, 4 and 9 May (B 723, 725), and Benita, 3 and 5 June (B 493-494).

All this time he was away from Ezkioga, but he did not forget his flock of seers and believers. He wrote many individually; he also sent an apostolic letter to the group. Assuming his position by divine right, he reproved the seers for denigrating one another, urged humility, and told them not to let themselves be photographed. The devil, he warned, was always ready to disturb their friendships and imitate true visions. He urged them to check against the devil by asking the apparition to repeat a pious phrase, by examining their own feelings after a vision, by vetting messages through other seers in trance, by consulting with their personal spiritual director, and by clearing messages for the general public with him, their "general director." He warned that if they did not behave well, God would take away their gift, and he closed commending them to "Gemma, the efficacious protector of our work" (see text in appendix).

The Mission of Juan Bautista Ayerbe

In Burguera's absence a new defender came forward. Juan Bautista Ayerbe Irastorza was the secretary of the small town of Urnieta, forty kilometers northeast of Ezkioga. There his brother Juan José was the parish priest. Previously, while town secretary of Segura, Ayerbe had rescued the municipal archive and published a book of local history. In August 1919 he visited Limpias and he wrote about those visions in national newspapers.[50]

J. B. Ayerbe (ca. 1865-1957), Hijos ilustres de Segura, and El Siglo Futuro, 23 August 1919, and El Debate, 20 July 1921. Another brother, Felipe, and two brothers of his wife were priests.

From his enormous output of mimeographed, dittoed, and typewritten semi-public letters and leaflets, it seems Ayerbe started circulating news of the Ezkioga visions in December 1932. He was led to believe in his own divine mission by Patxi.

On Saturday, the third of this month of December [1932], the seer Francisco Goicoechea went up the apparition mountain at four in the afternoon. During his ecstasy, which lasted about forty minutes, he received four messages. The third of these was for a J. B. A., who lived near San Sebastiÿn, who thereby satisfied a wish made to the Holy Virgin on the same day at ten in the morning without contact with the seer. The message has a close connection with these notes.[51]

Ayerbe, "Maravillosas apariciones," AC 1 [p. 6], and Boué, 126-127. From private collections of Ezkioga material I have made a consolidated archive (labeled AC) of original or photocopied documents written or recopied by Ayerbe, consisting of over 450 different items; this is a fraction of his output.

It took courage and commitment to defend this cause when many seers were in the mental hospital and Burguera himself was just out of jail.

A visiting expert helped confirm Ayerbe's belief in the visions. In mid-December 1932 Father Thomas Matyschok, "Professor of Psychic Sciences" from Germany, told him that the ecstasies of Conchita Mateos of Beasain were supernatural. That month Ayerbe wrote his first pamphlet, "The Marvelous

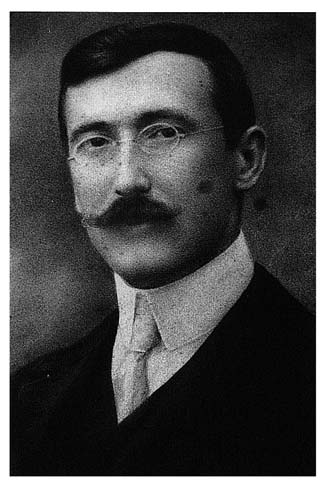

Juan Bautista Ayerbe, ca. 1930. Courtesy Matilde Ayerbe

Apparitions of the Most Holy Virgin in Ezkioga," and distributed two hundred dittoed copies in January.

Conchita Mateos was the twelve-year-old daughter of a worker in a Beasain factory. Ayerbe wrote, "She is the seer with whom I have most contact and whom I like the best because of her angelic manner and a prudence truly unusual in a girl her age." She was the youngest seer sent to the insane asylum. The real-estate agent Tomás Imaz took down some of her vision messages in December 1932 and subsequently Ayerbe went weekly to visions in her house in Beasain. About twenty persons generally attended these visions. She also had them in Ayerbe's house in Urnieta, where the Virgin showed a special partiality for Ayerbe's family. Ayerbe also distributed the vision messages of Luis Irurzun of Navarra, Esperanza Aranda, an older woman who then had most of her visions in San Sebastián, and others to believers in Terrassa, Barcelona, Madrid, and San Sebastián.[52]

Ayerbe to Cardús, 24 October 1933; I have Ayerbe's versions of about eighty sessions with Conchita from 10 December 1932 until 15 March 1942. He circulated messages from at least eighteen different seers.

His children grew up in a house where the presence of rapt visionaries was normal. According to his son Daniel, Ayerbe was devoted to anyone who was a believer. "He would not leave you alone, bringing you one thing after another until he overwhelmed you. But if you did not take an interest, you were public enemy number one." As Ayerbe wrote García Cascón, "I cannot disguise my sincere love for all who share my fervor for the apparitions. Maybe it is because there are so few of us or because we are so persecuted…. Is it because we imitate to some extent the first Christians of the catacombs?"[53]

Daniel Ayerbe, Irun, 13 June 1984, p. 1; J. B. Ayerbe to García Cascón, 22 March 1934, AC 416.

In spite of his "obsessive," "fanatical" (the words are his son's) activity in favor of the visions, an activity that lasted the rest of his life, Ayerbe never took sides among the seers or the leaders and was relatively modest. He did not want to threaten the careers of his brothers, so he usually remained just inside the limits of what might bring a public rebuke from the diocese. Because of the priests in his family, however, he was able to get away with more than others. He did not have a personal agenda for the visions, like Rigné, or a political one, like Carmen Medina; he was simply a scribe. Although he was an Integrist, his involvement in the visions stemmed from an interest in the politics not of Spain but of heaven—the broader designs that God held out for humanity. He wanted Ezkioga, as he had wanted Limpias, to be the Spanish Lourdes, but this time he went deeper and circulated messages about chastisements and Antichrists.

Ayerbe kept in touch with Pedro Balda, town secretary of Iraneta (Navarra), who served as the seer Luis Irurzun's scribe. In the rural north town secretaries were professionals with typewriters and time to use them. As the representatives of literate bureaucracy in rural villages, Ayerbe and Balda provided the seers with some local credibility. But their influence in the wider society was slight. On that level people like Medina, Burguera, and Rigné had more impact.

Away from Ezkioga in the winter and spring of 1933, Burguera worried about bad news he heard about the seers. From March 25 to 27 he accompanied a small group to Lourdes. At the grotto he felt that the Virgin confirmed his mission again. For when he asked the Virgin through a female seer in his group whether they might stay longer, the Virgin purportedly answered, "Tell the Padre that his duty is to go at once to Ezquioga, and when he has the Ezquioga matter all fixed up as at Lourdes, then he may come here."[54]

B 280. On the return trip from Lourdes the seer heard the Virgin explain that she wore colored robes in France because France received her better: "When Spain knows how to answer my call, I will show myself in Spain more splendidly than in France ... and work more miracles than in France."

Burguera no doubt knew that in mid-March 1933 one of the teenage seers had given birth to a child. Believers explained away the pregnancy by rape and dignified the birth by claiming it occurred without pain during a vision. But for the general public the pregnancy was a disgrace that affected the apparitions as a whole.[55]

For the pregnancy, Ducrot, VU, 23 August 1933, p. 1332; R 47, 95; and EE, April-May 1936, p. 2. Sexual immorality during the night visions was already an issue in the summer of 1931. Amundarain in his note of July 28 referred to "atrevidos desahogos nocturnos"; see also Masmelene, EZ, 15 July 1931; E. G., "En torno a los sucesos"; Millán, ELB, 9-10 September 1931: "una joven señorita ... recrimina a un señor que se aprovecha del lugar y del momento explorándola descaradamente"; Romero, "Communicado"; and Txindor, ED, 22 March 1932.

The scandal, which roused the many people in the region who had become skeptical, showed up in the broadsides of verses which are a Basque tradition. In October and November 1931 both the famous bertsolari (oral versifiers) José Manuel Lujanbio Retegi ("Txirrita") and his relative from OrdiziaPatxi Erauskin Errota, had published verses in praise of the seers Ramona and Patxi. Now José Urdanpilleta responded with two sheets. No doubt the most effective was the unsigned, scurrilous "The Great Miracle of the Virgin of Ezquioga," in which he identified by village two girls who had become pregnant and one boy who, he said, was a licentious as a ram and had even corrupted two nuns. Urdanpilleta had at least one public verse debate on the subject with Txirrita, and old-timers still remember lines from the argument. The Albiztur enthusiast Luistar published verses in support of the seers in 1931; but Laburu persuaded him to change his mind and in 1933 he published a long verse sequence against the seers. For Luistar and Urdanpilleta the great issue was immorality Txirrita had claimed the visions were true because they led to conversion; these poets claimed the visions were false because they led to sin.[56]

For verses about the visions, see below in bibliography Emika, Erauskin Errota, Lujanbio Retegi, Luistar, Urdanpilleta, and Zavala, Txirrita and Erauskin, 87-95. Verse 8 of Urdanpilleta, Berso Berriak, reads: "Euzkaldun neska gastiak / favores aditu / gauza biar bezela / nai det esplikatu / gaurko nere etsanak / goguan ondo artu / mariak beretsat lagun / garbiyak nai ditu" (All Basque girls / please listen / I want to explain this / properly / pay good attention / to what I have to say: / Mary wants for herself / clean friends). In 1984 Pedro Manuel Larrain of Alkiza remembered part of the verse debate in Zarautz (personal communication, Kepa Fernández de Larrinoa).

Prior to clearing up the scandals, Burguera had to recover his dignity. He attempted to do so in a four-page printed encomium signed by Ayerbe. It called for serious study of the Ezkioga visions and presented Burguera as "extraordinarily expert in the theological and ascetic-mystic matters so necessary for clarifying and resolving the apparitions … very well known by the intellectual elite of the Catholic world … armed with stunning erudition and perspicacity … with an apostolic zeal and an iron will." It described the Studium Catholicum, listed Burguera's published and unpublished works, and reproduced the entry for Burguera in the main Spanish encyclopedia ("a wise theologian").[57]

Ayerbe, Las Apariciones, obviously required Burguera's collaboration. The diocese privately complained to Ayerbe, who withdrew the leaflet. Burguera came to consider him a careless amateur who, although "active and zealous," did not know how to tell good spirits from bad ones (B 20-21).

The scandals, following the attacks by the church and the Republic, convinced Burguera that he had to do some serious "weeding" of the seers. His perplexity because some seers refused him their vision messages grew to a conviction that the devil was at work. After a month taking counsel with the Virgin in the visions of Ciordia, Benita, Aranda, and Garmendia, Burguera called a general meeting of seers. There he tried to rein in those who had taken advantage of their special status to lead freer lives. He told the girls who had found lodgings in order to be close to the vision site to go home, and he forbade seers to go on any more excursions.

Burguera claimed that some of the seers disobeyed him and started a "schism" because they did not want to give up their newfound liberty. In fact, any unity was in his own mind. He himself wrote that by this time there were three kinds of seers, the docile and obedient ones (obedient to him, that is), the untutored and credulous ones (by which I think he refers to the more rural, less classy or attractive seers, including those who spoke only Basque and trusted other, Basque-speaking leaders like Tomás Imaz and Juan Bautista Ayerbe), and the crafty and proud ones (he meant in particular Ramona and Patxi), who enjoyed the limelight and let no one direct them. As he began to do his weeding, the seers he rejected came out openly against him.[58]

B 280-82, 409, 711.

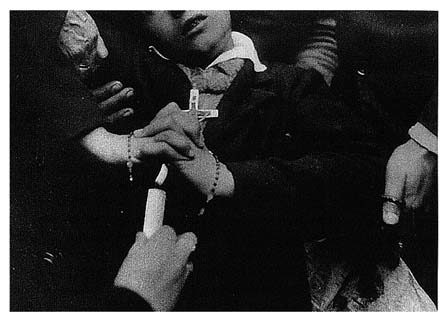

By now Burguera made no move without divine authority from trusted visionaries. He first tested the seers in vision by burning them on the hand with

Padre Burguera, probably, tests with a candle a boy seer in vision, mid-1933 (detail). Photo by

Raymond de Rigné, all right reserved. Courtesy Arxiu Salvador Cardús i Florensa, Terrassa

the flame of a candle. Those passed who did not react and felt no pain after the vision. For him this did not mean automatically that the visions were divine, but it did mean that the seers were worthy of further study.[59]

B 83-84, 282 n. 5. At Lourdes in 1858 Dr. Dozous had watched a candle flame in contact with Bernadette's hand, and doctors tested Patxi this way in 1931. Burguera's detractors argued against the test, citing I. Lenain, "Les Événements de Beauraing," Nouvelle revue téologique de Louvain (April 1933): 327-356.

When he tested Esperanza Aranda on 5 May 1933 in San Sebastián, two believing priests were witnesses. The flame burned "skin, flesh, and cartilage, causing a blister and a wound." Aranda did not react and her pulse remained steady. Lorenzo Jayo was present when Burguera tested his mother, María Recalde, at Ezkioga and remembers vividly the fat in her finger melting and a wound forming. A French writer saw the badly burned hand of José Garmendia. Rigné photographed Burguera burning with a candle the clasped hands of a boy in trance. In Albiztur he did the tests in the home of the parish priest. By July 14 sixteen seers had passed; others took the test later.[60]Aranda, B 711; Lorenzo Jayo, Durango, December 1984, p. 6; for Garmendia's burned hand, Boué, 116; photograph in VU, 23 August 1933, p. 1329; for Albiztur, the witness Juan Celaya, Albiztur, 6 June 1984, p. 26; sixteen tested, B 690; Luis Irurzun, San Sebastián, 5 April 1983, p. 17, took the test later.

These tests coincided with a new diocesan offensive. Starting in May 1933, less than a month after his return to Vitoria, Bishop Múgica instructed parish priests to obtain signed statements from the prominent seers, including Benita, Evarista, Ramona, and Gloria Viñals. The seers should retract their visions and vow not to go to the hillside. Benita signed that she would not go but added that she did so on the Virgin's instruction. She continued to have visions at home and when her parish priest found out and she refused to declare her visions diabolical

or illusory, he excluded her from the church. Accompanied by prominent Bilbao believers, her parents went to the bishop to protest, but Múgica went a step further and denied the child all the sacraments. Most other seers agreed to suspend their trips to the site, but few if any retracted the visions.

The combined pressure from Burguera to prove some visions "false" and from the bishop to force seers to retract the visions sent many seers into a kind of tailspin. They desperately sought divine messages that would please Burguera and affirm his authority. Garmendia, for instance, told him that the Virgin had said that all seers should obey Burguera and that whenever she had a message for Burguera, she would appear to Garmendia as long as necessary.[61]

B 638, 24 May 1933.

By the end of May Burguera's most trusted seers began to help by specifying the number of "true" seers who remained. Then, supposedly repeating what the Virgin told them, they began to finger the false ones. Pilar Ciordia declared that Conchita Mateos's visions were diabolical and that others should not go to the house. Burguera broke the bad news to the family, and Conchita agreed to a fire test. She passed and delivered a message: Burguera did well to test seers and those who disobeyed were not true seers. But Burguera nevertheless excluded her because of others he trusted more.[62]

AC 296, 1 June 1933.

The accusing continued, as in a witch-hunt. On June 3 Benita heard the Virgin say that Burguera should remove all reference to Patxi from the book because of the things he made up ("sus mixtificaciones"). Two days later Benita learned from the Virgin that of nine true seers only four would remain. The three others she had in mind would have been Evarista, whose visions she was explicitly confirming, Pilar Ciordia, who came from Pamplona to stay at her house from time to time, and her friend María Recalde. These four gradually eliminated others. On June 29 Burguera informed the Bilbao supporter Sebastián López de Lerena that his protégée Gloria Viñals was no longer a true seer. Burguera based this judgment on a vision by Evarista in Irun. On the same day Evarista and Garmendia declared that Burguera should remove from the book those who did not obey him.[63]

B 493-494, 565, 636, 727; López de Lerena to Burguera, 26 July 1933, private collection.

Seers had more spectacular visions under the stress of denouncing their friends. On July 14 Burguera and others watched an eight-hour Passion trance of Pilar and Evarista. The seers had announced the event twelve days in advance; lying on the floor they described the devil in the form of a great serpent encircling and strangling them. As they went through the motions of the Passion and were attacked by twelve devils (whose tortures with giant needles must have been reminiscent of Burguera's tests), they narrated their experience through a running dialogue with the Virgin. The Virgin took part in the crucifying. The ordeal was a sign for the upcoming chastisement of the sinful people in "packed theaters and movie houses and crowded beaches" who did not believe the apparitions. The Virgin was most bitter about the disobedient ex-seers who had once believed but then after falling into evil company abandoned her. But Pilar and Evarista were

obedient. "No Mother, we wish to be very good. Rather than stop seeing thee, we prefer a thousand deaths."[64]

B 689-693.

The core seers heard the Virgin say where to print the book and warned Burguera not to open certain letters, for the diocese wanted to pack him off to Valencia. Burguera was present in Navarra when Evarista in Basque and Pilar in Spanish both claimed to see eight devils drag the vicar general (yet again) to hell.[65]

For publication of Burguera's book, Benita, 3 and 5 June 1933, B 493-494; for letters, Evarista Galdós, 24 May 1933, B 726; Evarista and Pilar visions, Navarra (Uharte-Arakil), 7 July 1933, B 753, and López de Lerena to Burguera, 26 July. Pedro Balda was at the Uharte-Arakil sessions and warned Echeguren (Alkotz, 7 June 1984, pp. 1-2).

Burguera also felt the pressure, for the seers confirmed that the devil was out to stop him. Benita Aguirre, who had taken refuge with believers in Girona when denied Communion in Legazpi, wrote that in a vision she had seen him writing his book with good angels on one side and bad angels on the other. She and Evarista had seen a false Ezkioga book held by the devil, whom Evarista saw disguised as Gemma Galgani. Because the devil might interfere with his revisions, Burguera had to check his proofs and arguments with seers.[66]

Benita, 20 July 1933, B 500, and AC 21, p. 2; Benita and Evarista, 9 May 1933, B 685-686, 725; book content, Garmendia, 28 June 1933, B 639.

On 16 July 1933 Burguera, Garmendia, and Baudilio Sedano were in the hallway of the Hotel Urola in Zumarraga on their way to lunch. An uncouth man came in and warned Burguera he should "stop persecuting at Ezkioga." Burguera told the hotel owner to call the police because of the threat, but the man had disappeared (mysteriously, Burguera thought). The man could well have been a relative or follower of one of the seers whom Burguera was busy repudiating, but Burguera was convinced that he had seen the devil in human form, something María Recalde confirmed in a vision two days later.[67]

B 232-233.

The conflict between Burguera's seers and those he excluded came to a head a week later when on the apparition hillside Benita Aguirre's father read a warning from the Virgin that those who disobeyed Padre Burguera would suffer terrible divine punishment. The rumor was out that Burguera had asked as a special grace that only the seers who cooperated with him could see the Virgin. That would have simplified his job of discernment considerably. The first to react was Rigné, who on July 25 printed an open letter warning the seers that priests in rebellion against the church were misleading them. Instead, he said that they should consider Bishop Múgica Christ's representative and pray that he change his mind. The true history of the apparitions, he wrote, could only come from a canonical inquiry. Rigné was convinced that the seers who refused to obey Burguera were the most trustworthy.[68]

Given Rigné's lifelong delight in flaunting bishops, this attack on Burguera was a low blow; R 112-114, with Pilar Ciordia's retort.

Sebastián López de Lerena, an electrical engineer from Bizkaia who was perhaps the most balanced and realistic of the opinion leaders among the believers, wrote a stinging letter to Burguera denouncing his errors, his self-appointed authority over the seers, his improper trials by fire, not approved by theologians, and his attempt to blackmail seers into giving him their vision messages for his book under threat of declaring them nonseers. Above all López de Lerena charged that Burguera had unwittingly suggested many of the visions. He blamed the padre for dividing believers when more than ever they needed to stand together. These attacks increased Burguera's testiness. In the ensuing days

he had a falling out with José Garmendia. Two weeks later Pilar Ciordia told him that he had just avoided an ambush on his way from Zumarraga to Benita's house.[69]