Biblia Pauperum

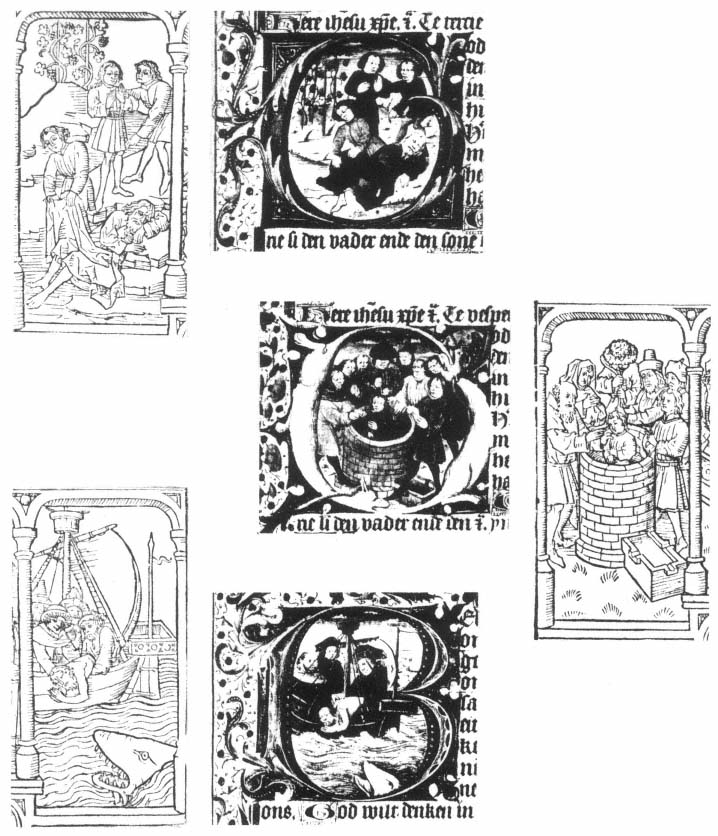

The name Biblia pauperum was used as early as the thirteenth century for various typological summaries of the Bible which might perhaps have been more accurately called Biblia picta , a title which appears in the manuscript of this work in Munich.[16] It was by no means as popular in its manuscript form as the Speculum humanæ salvationis . Some sixty-eight surviving manuscripts were documented in 1925,[17] but the blockbook editions appear to have been even more widely distributed than the Ars moriendi . The ten xylographic editions depend upon a single prototype and have forty anapistographic pages. Most of these are of a small square folio size, and within the framed architectural arrangement of the pictures, the text is carved in banderoles and rectangular units (fig. IV-8). They recount the story of the Fall and Redemption through the life of Christ, the central New Testament subject being flanked by scenes of Old Testament prefigurations, with portraits and predictions of four prophets, usually two above and two below.

Another edition of the Biblia pauperum consists of fifty pages, in which the ten extra subjects are partly borrowed from the Speculum and which survives in a unique copy at the Bibliothèque Nationale. A chiro-xylographic edition, of German origin, in thirty-four leaves is found in a single copy in Heidelberg, which is dated as early as 1420 by Musper, but which is thought to have been made in the late 1460's by Hind and Koch.[18] For the Netherlandish editions, scholars' dates vary from 1440 to 1480.

Research by art historians has brought to light some interesting relationships between dated illuminated manuscripts and the blockbook woodcuts. One of these is the richly decorated manuscript usually referred to as the Hours of Mary van Vronensteyn. It was originally owned by Jan van Amerongen, sheriff of Utrecht from 1468 to 1470, and his shears device can be seen on his cloak (Plate IV-2).[19] The date of the manuscript, 1460, is taken from its Sunday calendar in which a pointing hand is directed to the year 60 in the part dealing with the fifteenth century. Van Amerongen married Mechtelt Hendricksdr of Ghent, but they had no children and she left the Book of Hours to her niece Maria van Raephorst, who in 1520 married Lubbert de Wael van Vronensteyn. Thereby the manuscript acquired its name.[20]

[16] Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 22098.

[17] Henrik Cornell, Biblia Pauperum (Stockholm, 1925).

[18] Musper, op.cit. , p. 340; Hind, op.cit. , p. 242; Robert A. Koch, "New Criteria for Dating the Netherlandish Biblia Pauperum Blockbook," in Studies in Honor of Millard Meiss , edited by Irving Lavin and John Plummer (New York, 1977), I, p. 285.

[19] L. M. J. Delaissé, A Century of Dutch Manuscript Illumination , p. 45.

[20] K. G. Boon, "Een Utrechtse Schilder uit de 15de Eeuw, de Meester van de Boom van Jesse in de Buurkerk," in Oud Holland LXXVII (1961), p. 51, note 2.

Among the historiated initials there are some in which the pictures appear to be copied from certain scenes in the forty-leaf edition of the blockbook Biblia pauperum (fig. IV-9).[21]

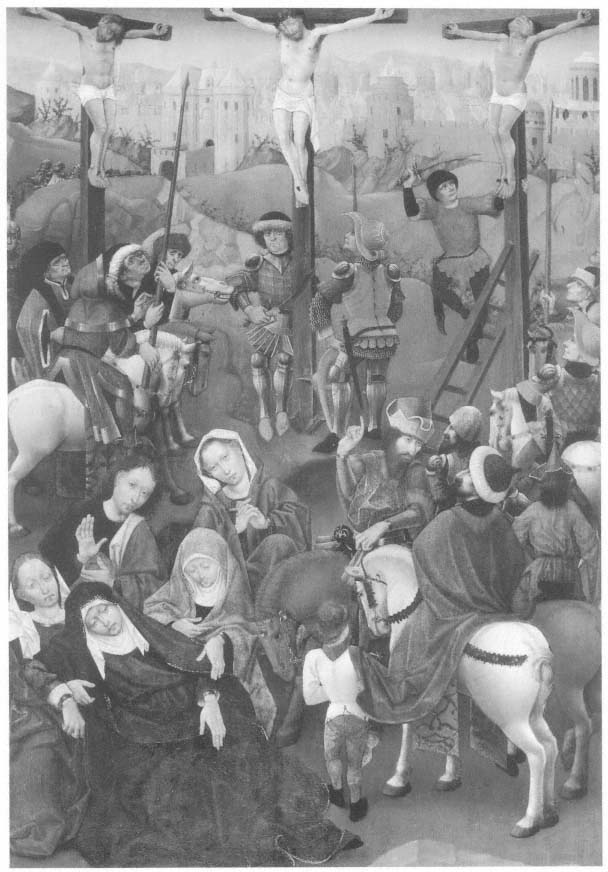

The artist of the twelve full-page illustrations of the Hours has been credited with certain miniatures in the Dutch Bible of Evert van Soudenbalch, now in Vienna, and with the painting of the Calvary, now in the Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design at Providence (fig. IV-10). To this artist is attributed the Christ Nailed to the Cross now in the Walker Art Gallery at Liverpool, and a mural painting, after 1453, of the Tree of Jesse in the Buurkerk in Utrecht (fig. IV-11). This group of paintings is related to a triptych of the Crucifixion, at Utrecht, which shows a view of the town and must be dated 1460–1465. Between 1455 and 1470 the only painter known to have received commissions from the Buurkerk was Hillebrant van Rewijk and he therefore might be considered the creator of the works above. His son may have been the better-known Erhard van Rewijk or Reuwich who made the famous woodcuts for Breydenbach's Peregrinationes in Terram Sanctam , which were printed under his name at the press of Peter Schöffer in Mainz in 1486. It has been suggested that the miniatures, mentioned above, of the Evert van Soudenbalch Bible and the full-page pictures of the Vronensteyn Hours might be his juvenile work.[22]

[21] Maurits Smeyers, "De invloed der blokboekeditie van de Biblia Pauperum op het getijdenboek van Maria van Vronensteyn," in Bijdragen tot de geschiedenis van de grafische kunst opgedragen aan Prof. Dr. Louis Lebeer (Antwerp, 1975), p. 378; see also Koch, op.cit. , I, p. 285.

[22] Boon, op.cit. , pp. 59–60.

IV-9.

Comparison of details of the Biblia pauperum with initials in

the Hours of Mary van Vronensteyn.

Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels, Ms. II 7619.

a. Ham Mocking Noah.

b. Joseph Cast into the Well.

c. Jonah Thrown to the Whale.

IV-10.

The Master of the Tree of Jesse in the Buurkerk.

The Crucifixion with Two Thieves, ca.1450–60.

Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, No. 61.080.

IV-11.

Master of the Tree of Jesse in the Buurkerk.

Fresco, The Tree of Jesse.

Rijksdienst voor de Monumentenzorg, Zeist.