Two—

The Birth of Hindi Drama in Banaras, 1868–1885

Kathryn Hansen

The construction of the modern literary history of India has been informed by an elitism comparable to that identified by the Subaltern school of historians in regard to Indian nationalism. Like nationalism, modern Indian literature, particularly in its origins, has been conceived as "the sum of the activities and ideas by which the Indian elite responded to the institutions, opportunities, resources, etc. generated by colonialism" (Guha 1982:2). The birth of Hindi drama in nineteenth-century Banaras affords a compelling example. In the received view, modern drama originated with Bharatendu Harishchandra, "father" of modern Hindi literature, in response to the introduction of European models and the rediscovery of a Sanskrit dramatic tradition (itself a "response" to the activities of foreign Indologists). The preexisting theatre traditions of the region are seen to have had no bearing on the nature of this event, and they have been excised from literary history.

Writing on the development of modern Hindi literature, Shri-krishna Lal declared an "absence of Hindi dramas" before Bharatendu (Lal 1965:181). Following Somnath Gupta, and before him the influential critics Shyam Sundar Das and Ramchandra Shukla, he posited reasons for this assumed absence, ranging from Muslim rulers' opposition to the dominance of bhakti poetry. Folk theatre forms, while acknowledged at least by Lal and Gupta, were not seen to have contributed to the growth of drama, being inherently "undramatic" (anatakiya[*] ). Extant Braj Bhasha dramas from the eighteenth century and earlier were regarded as poems only. These discussions make clear

[*] This chapter is based partially on research supported by grants from the Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute (1982), the Social Science Research Council (U.S.A.) (1984–85), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (1984–87). The generosity of all these agencies is gratefully acknowledged.

the wide acceptance of certain criteria of drama. A genuine dramatic text should be divided into acts and scenes, use different speech levels, and indicate entrances and exits (rules of Sanskrit drama); it should describe scenery and scene changes, develop complex characters, and build to climax (conventions of European stage); and it should not be predominantly poetic or musical or contain a self-referring narrator (as in Indian folk drama). These rules, as will become clear, were formalized by Bharatendu Harishchandra himself and were inherited together with Bharatendu's published canon of dramatic works, thus securing the "absence" of pre-Bharatendu drama and transforming it into a "problem." In the process, the popular theatre of the time was denied, lost to the pages of literary history, to the point where it is common to read, "Before Bharatendu, Hindi drama had no tradition of its own" (B. Shukla 1972:150).

My purpose in this chapter is twofold. If the value of studying popular culture, as Carlo Ginzburg suggests, lies in removing some of the silence imposed upon the nonelite groups by history, then, first, I would hope to give voice to the thriving, vital presence of popular theatre in Banaras at the time of Bharatendu's "invention" of modern drama.[1] I have used the evidence of recently discovered play texts published in Banaras, together with historical accounts of travelers, administrators, and local informants, supplemented by my own fieldwork on present-day folk theatre, to document the popular secular theatre traditions of Banaras in about 1880. Second, I would propose that Bharatendu's drama constituted an articulated, intentioned rejection of these popular traditions. The confrontation between Bharatendu's concept of a new elite theatre and the indigenous theatre is expressed in his theoretical writings on drama, and these, together with secondary biographical and historical data, constitute the sources for the second part of the chapter.

Popular Theatre in Late-Nineteenth-Century Banaras

Theatre was an important component of popular culture in nineteenth-century Banaras. Sacred spectacles like the annual Ramlila[*] native to Banaras or the seasonal Raslilas[*] of the rasdhari s[*] from Vrindavan were interwoven into the fabric of public religious life. The secular varieties of entertainment were probably just as numerous. These ranged in complexity from the street shows of solo disguise artists (bahurupiya s[*] ), acrobats, and animal trainers, to the elaborately staged musicals of the Parsi theatrical companies. Most of the forms found in

[1] On the "silence" of the subordinate classes in history, see Ginzburg's valuable preface to The Cheese and the Worms , especially xvii–xxii.

Banaras were common to the region extending from the Punjab to Bihar. A shared system of cultural codes and symbols, including the lingua franca Hindustani, its specific meters and song genres, a common body of folktales, and a single musical system, enabled the actors, musicians, and dancers to communicate easily throughout this region. The personnel associated with popular entertainment were primarily professionals who led an itinerant existence, touring within a geographical range that varied with their fame and access to patronage.

While certain unifying characteristics existed within this multiplicity of forms, I focus the present discussion on two varieties of theatre that can be definitively documented in late-nineteenth-century Banaras. The first is the folk theatre tradition known in this period as Svang[*] or Sang[*] (lit., "mime"). Svang is a musical form of theatre (often described as "operatic"), featuring full-throated male singers, loud, arousing drumming on the naggara[*] (kettledrums), and dancing by female impersonators. The tradition seems to have originated in the Punjab in the early nineteenth century, developing from recitations of ballads and oral epics. It then spread to Delhi, Meerut, and Banaras, where fledgling Devanagari printing presses reproduced its handwritten, illustrated librettos, known as Sangits[*] , from the 1860s on.

In about 1890 the Svang tradition was developed by certain folk poets of Hathras, who introduced a greater variety of themes, meters, and musical features into the plays. Further changes took place in Kanpur under the influence of the Parsi theatre, so that two distinctive styles (hathrasi[ *] and kanpuri[*] ) are now recognized. At some time in the early twentieth century, Svang came to be known as Nautanki[*] , after a fairytale princess, Nautanki Shahzadi[*] ; her story was a favorite in the theatre. In a state of decline since the 1940s, Nautanki shows are still found occasionally in the countryside as well as in the poorer neighborhoods of the cities, although its stories and tunes now imitate Bombay films rather than old ballads.[2]

Specifics of the nineteenth-century Svang tradition can be ascertained in part by examining the Sangits in the India Office Library and the British Museum in London (Blumhardt 1893, 1902). Unlike much folklore, consigned to the oblivion of oral tradition, Svang dialogues were copied down, probably for the actors' convenience, and circulated in manuscript form.[3] Beginning in 1860 or earlier, these handwritten manuscripts were lithographically printed, and typeset versions appeared in the 1890s. Sangits in pamphlet form can still be purchased from publishers' warehouses or on the street. The quantity of pub-

[2] For a brief history of Svang and Nautanki, see Hansen 1986.

[3] Robson mentions obtaining the manuscripts of Khyals[*] owned by Maharajas in Rajputana, and Temple also consulted the texts in the possession of Svang actors.

lished Sangits[*] is very large. Dozens of local presses are engaged in the trade, and during the last century, four hundred titles or more have appeared.[4]

Eight Svang[*] plays (Sangits) published in Banaras between 1868 and 1885 are preserved in the British Museum. All except one are named for their heroes. Five of them concern famous devotees (Prahlad[*], Gopichand[*]Bhartari[*], Raja[*]Harichandra , and two versions of Dhuruji[*] ), while one is a fragment concerning a king reclaiming his throne (Raghuvir[*]Singh ), and two are romances (RajaKarak[*] and Rani[*]Nautanki[*] ). Four were published in Banaras (Kashi) by Munshi Ambe Prasad, three by Munshi Shadi Lal, and one by Lala Ghasiram, and the dates of publication range from 1875 to 1883. Except for the 1875 Dhuru[ *]Lila[*] and Sangit[*]Rani Nautankika[*] , all of the texts had been published previously, in Delhi, Meerut, Agra, or Lucknow.[5]

Two of these Sangits, Gopichand Bhartari and Prahlad , had a long publishing history, with at least twenty-seven editions of Gopichand appearing between 1866 and 1893, and sixteen of Prahlad . The Sangit version of Gopichand even came to the attention of linguist George A. Grierson. "There is no legend more popular throughout the whole of Northern India," he wrote, "than those [sic ] of Bharthari and his nephew Gopi Chand. . . . A Hindi version of the legend can be bought for a few pice in any up-country bazar" (Grierson 1885:35).

In five out of eight of these plays, the name and particulars of the author are mentioned within the text. The famous Prahlad and Gopichand plays were both written by Lakshman Singh, alternatively styled Lachhman Das, but little is known of him. The author of Raghuvir Singh was Hardev Sahay; he also wrote Sangit Siya[*]Svayamvara[*]ka and coauthored Sangit Rup[*]Basant with Lakshman Singh. In the text he describes himself as a Brahmin (vipra ) and a pandit, and he appears to be the same Hardev Sahay who ran the Jnan Sagar Press in Meerut. Khushi Ram, the author of RaniNautanki , describes himself as a Brahmin from Faraknagar in Gurgaon district. Jiya Lal, the author of RajaHarichandra as well as of Raja Mordhvaj , provides the fullest self-introduction:

I am head of the guards, a Jain scribe by caste.

In the world my name, Jiya Lal, is famous.

My name Jiya Lal is famous, my hometown is Faraknagar.

In Chaproli I received this story already made.

(Jiya Lal 1877:51)

[4] For figures and statistics on the volume of popular publishing in Sangits and other genres, see Pritchett 1985:20–36, 179–90.

[5] A list of Banaras Sangits published between 1868 and 1885 appears at the end of this chapter.

Internal evidence helps us to assign the texts to a single genre. All except one contain the word Sangit[*] in the title, while the terms sang[*] , svang[*] , sangit[*] , or sangit bhasha[*] ("musical play in the vernacular") are also present in many of the invocations and colophons. Two of the plays refer to themselves as lila[*] , and each of these, significantly, is focused on a saintly personage, in these cases Dhuru and Gopichand. Such dramas may have developed in imitation of the lila s[*] of Krishna and Ram[*] , pointing to an earlier stage when Svang[*] was indistinguishable from popular religious theatre. However, these saint legends were more likely connected with oral recitations by ascetics and mendicant groups. The Gopichand story, which concerns the conversion of a king to the path of Guru Gorakhnath, was one of the legends popularized by the Kanphata or Nath Yogis, who wandered all over north India. Other legends associated with this sect are Guga (Zahir Pir), Puran Bhagat, Raja Rasalu, Hir-Ranjha, and Rani Pingla (Briggs 1938:183–241). It is noteworthy that Svang versions of all these Nath stories exist in the old Sangit collections.[6]

The Banaras Sangits[*] can be distinguished from legends, tales, and other types of dramatic texts by their poetic meters. The characteristic meters at this time are doha[*] (a couplet, line length 24 matra s[*] ), kara[*] (a quatrain, line length 24 matra s), and chaubola[*]chalta[*] (a quatrain, line length 28 matra s). Songs in various ragini s[*] (modes or tunes) are also interspersed. These meters are specified in the text in full or abbreviated form (do . for doha, chau . for chaubola ). The alternation of speakers is marked by headings, such as "reply of the queen to the king" (javab[*]rani[*]ka[*] raja[*]se ). These meters and printing conventions continue in the twentieth-century Sangit texts.

The connection of the Banaras Sangits to more recent texts is also illustrated by their subsequent publishing history. Lakshman Singh's Gopichand[*] Bharthari[*] , for example, continued to be reprinted well into the twentieth century. A chapbook printed in modern type recently came to my attention in a Jaipur bazaar. On examination, the text turned out to be identical to the nineteenth-century version by Lakshman Singh, except for orthographic changes introduced to conform to current printing practices.

That Sangit texts were published in Banaras in the 1880s suggests that performing Svang troupes had toured the area and established a

[6] In further support of this point, Sherring records two groups of ascetics, Bhartharis and Harischandis, whose main occupation involves retelling the stories of the famed kings for whom they are named (Sherring 1872:261, 267). Similarly, K. Raghunathji mentions a group called Gopichandas, who "carry fiddles and sing in praise of Gopichand" (Raghunathji 1880:279). Given the prominence of Banaras as a gathering point for ascetics, we can assume that their lore became part of popular culture and was assimilated into theatre and other performance traditions.

reputation for popularity. This in turn created a demand for the texts of their plays to be circulated in print (see fig. 6). Such a process was explained in an "Announcement" on the back cover of a Sangit[*] published from Kanpur in 1897:

Let it be known to all good men that the entertainment (tamasha[*] ) of the troupe from Hathras has been shown in various places in Kanpur, and many gentlemen have gathered for it and all their minds have been pleased. Seeing the desire of these good men, we have published the same entertainment . . . so that whenever they read it, they will obtain happiness and remember us. (Chiranjilal-Natharam 1897)

The publication of a play text subsequent to its performance is also confirmed by present-day practice (Pritchett 1983:47). Unfortunately, no details of Svang[*] performances in nineteenth-century Banaras appear to have survived. For information on the performative circumstances we must rely instead on accounts from other parts of northern India.

One source is Richard Carnac Temple, a British administrator who collected an impressive body of folklore from the Punjab in the late 1870s and early 1880s. His three-volume Legends of the Panjab contains texts of four Svangs[*] performed in Ambala district in 1881 and 1883: Guru[*]Gugga[*], Shila[*]Dai[*], Gopichand[*] , and Raja[*]Nal . All of these were composed by a poet named Bansi Lal. In the preface to volume 3, Temple also lists a number of unpublished manuscripts in his collection, which include familiar Svang titles like Harichand, Amar Singh, Raja Karag[*], Dayaram[*]Gujar[*] , and Rani[*]Nautanki[*] .

Temple was exposed to the Svang tradition while attending the Holi festival at Jagadhri. He later called the actors in private and had a scribe copy down their verses as they recited. He also prevailed upon Svang performers to give him their private manuscripts (Temple 1884, 1:ix). Temple's Svang singers were Brahmins, of a higher status than other types of bards, and some of them were literate. They engaged in playacting as a profession (Temple notes they are "called in—on payment always"), but Temple gives no information on their backgrounds or features of their performance. His remark that the Svang "is not strictly a play according to our ideas" seems to refer to the third-person commentary provided by the rangachar[*] (stage director) and by the characters themselves, and also to the absence of European conventions of scene divisions, curtains, and scenery (Temple 1884, 1:243). The metrical structure and other stylistic features of Temple's Svangs link them clearly with the Sangits[*] published in Delhi, Meerut, and Banaras in the same period.

Another account, from farther to the west in Rajasthan, is John Robson's Selection of Khyals or Marwari Plays (1866). (The term Khyal[*] was used in this period as a generic term for north Indian folk drama,

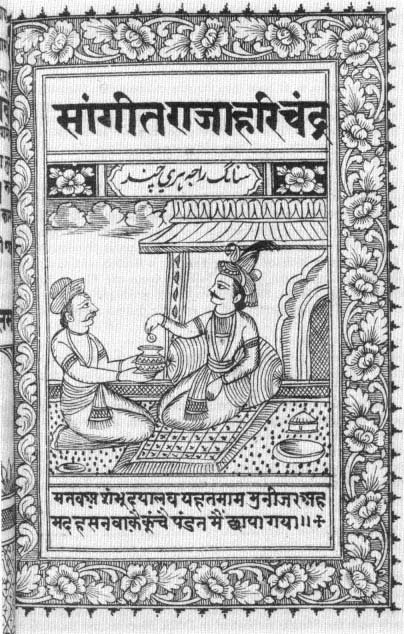

Fig. 6

The cover of Sangit[*] Raja[*] Harichandra ka[*] , by Jiya Lal (Banaras, 1877).

Courtesy of The British Library, Oriental Manuscripts and Printed Books.

although nowadays Khyal[*] signifies a Rajasthani form and its language is Marwari or other Rajasthani dialects.) Robson, like Temple, describes a performance situation associated with the festival of Holi.

In the principal cities and towns of that country, during the weeks following the Holi, crowds assemble night after night around elevated spots of ground or chabutra s[*] , which supply a ready-made stage, and on which rude attempts at scenery are erected, and the players continue acting and singing accompanied by an orchestra of tom toms, on till late at night, or early in the morning, and for weeks and months afterwards, the favourite refrains and passages may be heard sung in the streets and markets. (Robson 1866:vi–vii)

Robson refers to a large body of Khyals[*] ("hundreds"), a history going back to 1750, and the low reputation of the form (Robson 1866:v–vi).

Descriptions of a performance of the drama Prahlad[*] and the contents of a playbill of the "opera" Puran[*]Bhagat from Lahore in the late nineteenth century are contained in J. C. Oman's Cults, Customs, and Superstitions of India. Prahlad was sponsored by a "successful tradesman, who hoped to acquire some religious merit by having a moral drama produced for the benefit of his fellow-townsmen" (Oman 1908:195). Accounts of a number of other north Indian dramas, including Prahlad, Hir[*]Ranjha[*] , Bin[*]Badshahzadi[*] , and Svangs[*] from the Punjab, such as Gopichand[*], Puran Bhagat , and Hakikat[*]Rai[*] , are found in William Ridgeway, The Dramas and Dramatic Dances of Non-European Races , which documents a slightly later period (Ridgeway 1915:181–99). The existence of Svang[*]akhara s[*] in Saharanpur in 1910 is mentioned by Ramgharib Chaube in the Indian Antiquary (R. Chaube 1910:32). These reports do not satisfy our curiosity about the composition of Svang troupes, the size and nature of the audience, caste of the patron, the costumes, makeup, stage appurtenances, presence of musicians and dancers, and countless other aspects of performance. However, they do establish the link between the Banaras Sangits[*] and a Svang theatre of considerable popularity, stretching from Punjab and Rajasthan to eastern U.P. in the late nineteenth century.

The manuscripts available indicate a transition from a simpler format, involving dramatic recitation of legends by two main characters, to a more complex structure involving a larger number of actors and more frequent turns of plot. Subject matter was gradually moving away from stories concerning saintly figures (Gopichand, Prahlad ) to romances (Rani[*]Nautanki[*] , Raja[*]Karak[*] ), shifting from otherworldly values to an emphasis on victory in love and war. The metrical varieties were becoming more sophisticated, suggesting a more complex musical repertoire and an evolving performing style. The later plays show

more diversity of meters, and by 1892 the meter daur[*] had joined the earlier doha[*] and chaubola[*] to form the stable ten-line stanza that constituted the metrical trademark of the genre.[7]

Assuming that the Svang[*] performance ethos changed little between the nineteenth and the twentieth century, we can infer its general character from more recent observation of the Svang and Nautanki[*] stage. Then as now, the performance venue was probably a public space accessible to many classes of people, such as a fairgrounds, crossroads, or market. Large crowds would gather, and social behavior reflected the spontaneity and looseness associated with impromptu open-air entertainment.[8] When private shows were commissioned, it was often in connection with a marriage or feast-day where an ebullient atmosphere prevailed. The reference in both Temple and Robson to Svang festivals at the time of Holi, the spring bacchanalia, implies an affinity between seasonal rites of reversal and popular theatre.

In the techniques of theatrical presentation, an informality and openness characterized Svang. Stage arrangements might include the erection of a makeshift platform where necessary or the use of an available porch or chabutra[*] . The employment of props, scenery, and stage devices was minimal, in part dictated by the itinerant lifestyle of the troupe. Plays had a loose, variable structure based on episodes, and a leisurely pace of presentation with little dramatic tension; performances lasted late into the night or until morning. During the performance the audience (and the actors) were free to eat, drink, smoke, chat, or be still (Gargi 1966:37).

Another important aspect of Svang was its competitive, exhibitionistic impulse, a likely by-product of the akhara[*] system. The akhara (lit., arena, gymnasium) was then and remains the organizational unit for many types of folk music and drama in northern India. Performers are linked by their allegiance to a guru or ustad[*] to a particular akhara , whose compositions are passed on to them; akhara members form the primary personnel of the troupe. The various akhara s[*] are in a perpetual state of competition with one another, which is acted out in each public appearance. The performance event is structured as a dangal , a

[7] The text in which the meter daur first occurs is Khyal[*]Puranmal[*]ka[ *] (actually a Sangit[*] in Khari Boli Hindi, not a Rajasthani Khyal), published in 1892 by Ganesh Prasad Sharma in Calcutta. The play is significant because it appears to be the earliest published composition of Indarman, the guru of the first and most prominent of the Hathras akhara s, and because it is the first Sangit set in modern Devanagari type.

[8] The ideology of "freedom" and "openness" has been discussed with reference to the artisans of Banaras by Nita Kumar (1984). A similar value system would seem to characterize the audience of nineteenth-century Svang, many of whom (in the urban areas at least) were probably artisans of the type described by Kumar, although the audience was not limited to any one caste group.

tournament or contest between rival akhara s[*] , with the object of outdoing the opponent and obtaining "victory."

The akhara[*] system entered the Svang[*] tradition through the institution of Turra-Kalagi[*] , a dialogic poetic genre traceable to eighteenth-century Maharashtra. In it, rival groups designated Turra[*] (representing the Shaivites) and Kalagi[*] (Shaktas) directed questions and answers to each other on metaphysical themes, using the song type known as lavani[*] (or khyal[*] ) (Tulpule 1979:440). Later these troupes traveled northward, following the Maratha armies, and expanded their performances to include narrative material, giving rise to the folk drama forms Manch[*] in Madhya Pradesh, Khyal[*] in Rajasthan, and Svang in U.P. (see fig. 7). By 1890, Svang texts abound with references to the dangal situation. Most common is the invocation to the goddess to descend upon the poet and protect his honor by inspiring him during the poetic combat.[9] This competitive ethos resulted in a high degree of interaction between performers and audience, with an atmosphere of enthusiasm and partisanship akin to a sporting event. The dangal mode provided an alternative aesthetic structure to that of the Aristotelian plot, binding the performance event in a different tension.

Svang shows, like most other public events that lacked an explicit religious function, were most likely off limits to women in the nineteenth century. Women did not participate as actresses on the Svang/Nautanki[*] stage until about 1920; before that all female roles were enacted by men. The fact that Svang shows occurred in public space ensured that the audience would be primarily men. Women had comparatively less freedom to leave the home, because of parda[*] restrictions, and in lower-class families less leisure to do so, because of economic responsibilities. Upper-caste folk in general were admonished to avoid such entertainments; these were considered unsuitable, especially for those who were "by nature" morally weaker—for example, women and boys. Indications are that in the nineteenth century as in the twentieth, the popular stage was dominated by the "male gaze." Fulfillment of male fantasy and desire were among its main attractions, as they are in the popular cinema in India today.

This introduces perhaps the most often noted feature of Svang, its allegedly "low," "lewd" character, which provoked exclamations of

[9] In the mangalacharan[*] of Khyal Puranmal[*]ka[*] (1892), the poet invokes the goddess Bhavani:

Come sit in my throat, goddess, and sing 3,600 ragas.

. . . Protect the honor of your servant.

Drink the blood of the wicked.

Be gracious to me now,

Uphold my respect today in the assembly.

Fig. 7

The cast of the drama Bin[*] Badshahzadi[*] , a Svang[*] of the late nineteenth

century. From William Ridgeway, The Dramas and Dramatic Dances of

Non-European Races , 1915.

contempt from the foreign observer or high-caste Indian informant. Was the nineteenth-century Svang[*] indeed obscene? The Banaras Sangit[*] texts, on the contrary, point to a highly moral universe, where good deeds and truthfulness are rewarded by the gods (Raja[*]Harishchandra ), where kings yearn to become saints (Gopichand[*]Bharthari[*] ), where even children are capable of exemplary devotion (Prahlad[ *], Dhuru[*] ). When such instructive tales were posed in the common tongue, in an unbounded, exhibitionistic, male-oriented milieu, however, the message, at least for the elite observer, was reversed. (The allegations of obscenity were not made by the lower-caste spectators, or at least we have no record of their views.)

The opprobrium of the elite, I suggest, had less to do with the obscene gestures, the display of the female body, and the unruly crowd—all convenient pretexts—and more to do with the wider significance of the theatre in the cultural system. Parallel to festivals like Holi, Svang provided an arena for staging symbolic inversions of the power structure of the society at large.[10] These inversions took place on stage, in the debunking of authority coded in the routines of clowns and transvestites.[11] Motives of mistaken or lost identity and disguise were very common, playing on the inversion of hierarchically ordered categories such as male-female, parent-child, master-servant. Virtually every text in our period reveals a significant element of status reversal—for example, king becomes an ascetic (Gopichand, Raghuvir[*]Singh ), king becomes an untouchable (Harishchandra ), child becomes a preacher to adults (Prahlad, Dhuru ). The text that set the fashion for future development in the genre, Rani[*]Nautanki[*] , contains multiple incidents of cross-dressing and transformation of gender identity, both from male to female and from female to male.

Inversions were also manifest offstage, in crowd behavior expressive of loss of control and the absence of authority, ranging from noisiness, crude language, and drunkenness to actual physical violence. Such inversions were not written into the script, and they were not necessary to any given performance, but they were communicated in the larger text of the theatre: in the use of unbounded public space, in the open-ended time frame, in the competitive situation, in the absence of a controlling figure of authority, in the gathering together of spectators from all castes and classes. This was not a theatre of protest, and resistance to oppression was rarely an implicit or explicit message here.[12]

[10] See Barbara Babcock's Introduction, 1978:13–36, for definition and discussion of the history and use of the concept of symbolic inversion.

[11] A suggestive parallel to the clowns and transvestites of Svang is provided by James L. Peacock in his study of these figures in Java, in Babcock 1978:209–24.

[12] Political themes are not the norm in Svang/Nautanki[*] , a notable exception being a number of Sangits[*] composed after 1920 on the incident at Jallianwalla Bagh (e.g., P. M. Shukla 1922).

Nonetheless, the very existence of such an arena outside of the direct control of the elite constituted a negation of their authority, and it was therefore perceived as a threat and condemned.

In the nineteenth century Svang[*] served all levels of society, and it would probably be fallacious to imagine its audience as composed entirely of lower castes and classes. Brahmins and high-caste poets were active in writing Svang texts, and the widespread publishing of these texts suggests a sizable literate readership, who may well have included members of elite groups. The distinction between "popular" and "elite" that has been made so far is thus a somewhat idealized one; indeed, greater or lesser participation in "popular" entertainments by "elites" is observable throughout the period. However, in relation to the Parsi theatre we are about to describe, and even more so in relation to Bharatendu's theatre, Svang manifested an overwhelmingly popular character. It was available to the laborers, artisans, and peasants and was part of their cultural universe, and it reflected their tastes, dreams, and beliefs. Svang maintained its position distant from elite appropriation, and elite disapproval ironically ensured its survival.

In contrast, the Parsi theatre appealed to a relatively sophisticated, urban middle-class audience. The so-called Parsi stage of the second half of the nineteenth century was a broad-based commercial theatre whose appeal and influence extended far beyond the ethnic group for which it was named. It developed in about 1850 from Parsi-organized amateur groups in Bombay, like the Elphinstone Club, which were active in presenting English and Indian drama classics. Soon full-fledged professional companies were being floated by Parsi businessmen who were themselves theatre buffs. Many of the leading actors, also Parsis, held shares in these companies, and several of them went on to form their own companies. Khurshedji Balliwala founded the Victoria Theatrical Company in Delhi in 1877, and Khawasji Khatau, the "Irving of India," established the rival Alfred Theatrical Company in the same year. Dozens of companies sprang up across the subcontinent, attaching the phrase "of Bombay" to their names to associate themselves with this prestigious new theatre. Muslims, Anglo-Indians, and a certain number of Hindus joined the companies, but the organizational reins remained largely in Parsi hands.[13]

In a short time the demand for Parsi theatre fare spread to all parts of India. The major companies routinely toured between Bombay, Lahore, Karachi, Peshawar, Delhi and the Gangetic plain, Calcutta, and

[13] Little original research has been done on the history of the Parsi theatre. The main secondary sources are R. K. Yajnik 1933; Somnath Gupta 1981; Ram Babu Saksena 1940; Birendra Narayana 1981; Annemarie Schimmel 1975; A. Yusuf Ali 1917.

Madras. The Parsi stage had a major impact on the emerging vernacular theatres in south as well as north India. Although Gujarati was the first language of the Parsi theatre, by the 1870s the large companies had adopted the practice of hiring Muslim munshi s[*] (scribes) as part of their permanent staff, and Urdu became the principal language of the stage. In the early twentieth century, Talib, Betab, Radheyshyam, and others began writing plays in Hindi for the Parsi companies. The Parsi theatre was never a bastion of linguistic purity, and to entertain the widest cross section of society it favored the Hindustani forms of speech which were the most readily understood.

Much of the initial inspiration for the Parsi stage came from British-sponsored dramatic efforts in their colony. English-style playhouses were erected in Bombay and Calcutta in the late eighteenth century, and the native elite was invited to attend from time to time. Later the Parsi companies played in the same halls and took over the material culture of European theatre: the proscenium arch with its backdrop and curtains, Western furniture and other props, costumes, and a variety of mechanical devices for staging special effects. Artists from Europe were commissioned to paint the scenery, and the latest in "elaborate appliances" were regularly ordered from England, so as to achieve "the wonderful stage effects of storms, seas or rivers in commotion, castles, sieges, steamers, aerial movements and the like" (Yajnik 1933:113; Yusuf Ali 1917:95–96). The British example was also followed in matters of advertising and scheduling. Playbills boasting the latest Saturday evening performance were distributed throughout the city, and in the auditorium, spectators perused the "opera book" or program containing the lyrics of the latest songs (Yajnik 1933:111–15).

However, in several important respects, aside from language, the Parsi theatre revealed its Indian character: it employed Indian subject matter, and it included a great deal of music and dance. The first Indian-produced dramatic performance in Bombay is said to have been a Hindustani version of Raja[*]Gopichandra[*] written by Vishnudas Bhave. Hindu epic heroes and heroines—Harishchandra, Prahlad, Nala and Damayanti, Savitri, and Shakuntala—were extremely common on the Parsi stage, as were characters from the stock Islamic romances: Shirin Farhad, Laila Majnun, Benazir Badremunir, Gul Bakavali. The Parsi theatre's sizable repertoire of mythological and legendary plays drew upon the same stratum of north Indian popular culture that produced the nineteenth-century Svangs[*] . Of course Shakespeare was also very popular, usually dressed up in Indian guise, and some English comedies were adapted as well (Yajnik 1933:125–216; Yusuf Ali 1917:90).

The music and dance of Parsi theatre, while difficult to document, appear to have been liberal in measure and hybrid in manner. The

"orchestra" often consisted of harmonium and tabla, played by accompanists who, sitting in the wings or pit, "also in many cases do duty as prompters" (Yusuf Ali 1917:96). The musical style has been described variously: "tuned to the traditional modes (Ragas)" and "in the chaste classical style," by Narayana (1981:40), but consisting of "slipshod Parsi and semi-European tunes," by Yajnik (1933:115). Partial manuscripts of two plays, Jahangir[*]Shah[*]aur Gauhar of unknown authorship and Raunaq's Benazir[ *]Badremunir[*] , do contain the names of classical and semiclassical ragas, such as Bhairavi[*] , Sorath[*] , Desh, Pilu[*] , Kalingra[*] , and Kalyan[*] , at the headings of the thumri s[*] , ghazal s, and other songs. An initial phrase is given in quotes, the opening line from an already wellknown song, as an indication of the tune to be followed (S. Gupta 1981:Appendix 2, 40–50). In actual practice, this classical basis may have been considerably undermined in favor of novelty and catchiness.

When women were admitted to the Parsi stage in about 1880, an innovation commonly credited to Balliwala, they were recruited primarily from the ranks of professional singers and dancers. Their crowd-pleasing tactics were a big draw, and solo dancers "were rewarded by the audience with currency notes and coins amidst shouts of 'Encore' " (Narayana 1981:40–41). The better-known actresses, Khurshed, Mehtab, and Mary Fenton, achieved their fame at least partly on the basis of genuine talent. Boy actors gifted with sweet voices, good looks, and physical graces were also employed by many professional companies to play the heroines' roles and perform dance items, and "boy companies" became a popular item in certain regions (Yajnik 1933:109–10).

An idea of the literary style of the plays can be obtained from the available scripts, which show that a typical scene in a Parsi stage play consisted of a variety of songs and verses (in forms such as thumri[*] , ghazal, lavani[*], sher, musaddas , mukhammas[*] , savaiya[*] , or simply gana[*] ) interconnected by prose dialogues. In the early plays even the dialogues were composed in rhymed metrical lines, and they were spoken with great emphasis to project the actor's voice to the back of the hall. Later, prose became predominant, although rhyme at the end of sentences was retained. In such stylistic matters, as well as in story content and music and dance, a great deal of mutual influence is visible between the north Indian folk theatre forms such as Svang[*] and the Parsi theatre in this period.

The first Parsi touring company to reach Banaras was the Victoria Natak[*] Mandali[*] , which performed in 1875 (Anand 1978:54). After this, it can be assumed that visits by the Parsi companies became a regular part of the local entertainment scene. Several prominent playwrights of the Parsi theatre were from Banaras, including Raunaq, who published

plays such as Hir[*] Ranjha[*], Laila[*]Majnun[*] , and Puran[*]Bhagat in about 1880, and Talib, who was writing about twenty years later.[14]

Educated opinion in Banaras was uniformly disparaging toward the Parsi theatre. At a performance of Shakuntala[*] , several members of Bharatendu Harishchandra's party walked out of the theatre when Dushyant swaggered onto the stage, singing and dancing lasciviously (S. Mishra 1974:789). The Hindi journalist Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi warned novice playwrights against the quick path to fame afforded by "writing such trash" and reprimanded errant theatregoers: "Those who go to see Indara Sabha and Gulabakavali etc. presented by Parsi Theatrical Companies should think about their own good" (Narayana 1981:48).

Although the elite saw in the Parsi theatre vulgarity, sensationalism, and lack of aesthetic standards, the humbler sections of society thrilled to the mystique of English company names like the Corinthian, the Victoria, and the New Alfred. The allure was augmented by the sumptuous fittings of the Parsi stage, replete with elaborate painted scenery, fine costumes, exotic Anglo-Indian actresses, and tricks of stagecraft. Such shows may have been commonplace in the numerous theatre houses of the big cities, but in the provincial towns the spectacles no doubt overawed the populace. No wonder then that the Bombay companies were eagerly sought as the purveyors of all that was current and stylish in theatre practice—and were emulated and imitated wherever they performed. This was especially true in the cities of Uttar Pradesh like Banaras.

Despite its more elaborate organization and urbanized clientele, the Parsi theatre provided essentially the same stimulus to the reversal of social rules as did the simpler Svang[*] stage. Here too the crowd reveled in the public display of eroticism, in the extremes of pathos and melodrama, in the latest gimmicks and spectacles. Because of its closeness to middle-class popular taste, the Parsi theatre posed an even greater threat to elite standards of propriety than did the Svang folk theatre. Here too the prevailing social codes seemed, however temporarily, to be turned upside down. What the Parsi theatre provoked by way of reaction—an elite theatre predicated on values of control, order, and refinement—will now be examined in the career of Bharatendu Harishchandra, its chief exponent.

[14] At least four of some twenty-five plays of Raunaq's are in the British Museum collection; these were published in Bombay in 1879–1880 and are printed in Gujarati script. Also see S. Gupta 1981:62–71. For a discussion of Talib's works, including examples of his language, see Gupta 1981:71–85. Gupta indicates that Talib's plays were published by Khurshedji Balliwala, and he bases his comments on personally owned manuscripts.

Bharatendu Harishchandra and the Elite Hindi Theatre

Bharatendu Harishchandra was born in 1850, the eldest son in a wealthy and socially prominent Agarwal family in Banaras.[15] Since the days of Shah Jahan his forefathers had been associated with various ruling families of northern India as moneylenders and bankers. Bharatendu's great-great-grandfather, Amichand (Omichand), amassed a large fortune in Bengal in the eighteenth century, acting as an intermediary between the British East India Company and the Nawabs at Murshidabad, but he was double-crossed by Clive and ultimately lost everything (Dodwell 1929, 5:141–51). After this debacle, his son Fateh Chand migrated to Banaras in 1759 and became financier to the Maharaja of Banaras while also continuing the friendly ties with the British which had proved his father's undoing. By the time of Bharatendu's grandfather Harsh Chand, the family had again become extremely wealthy. The Maharaja's treasury was kept in the vaults of Harsh Chand, and he led a life of ostentation, parading about the streets with large numbers of bodyguards and a martial band in attendance. Bharatendu's father, Gopal Chandra, protected the valuables of the British Residency during the unstable times in 1857 (Gopal 1972:4–10).

Bharatendu's literary talents and role as cultural patron appear to have been inherited from his father, who composed a number of poetic and dramatic works, including what some call the first modern drama in Hindi, Nahushnatak[*] . In Bharatendu's generation the joint family continued its close ties with the Maharaja of Banaras, but their role as moneylenders eroded as Bharatendu squandered his fortune on literary and cultural activities as well as more hedonistic pursuits, such as the maintenance of his two mistresses, Madhavi and Mallika, and a harem of nautch girls. In his lifetime he was famous for emulating his namesake, King Harishchandra of the Markandeya[*]purana[*] , who was so generous that he gave away his kingdom and sold his wife and son into slavery in fulfillment of a vow. Possessing little inclination for generating income or saving it, Bharatendu had no trouble devising ways of spending, and the lifestyle of the rakish, extravagant nobleman sat easily with him. He was a perfect representative of the wealthy Vaishya

[15] The primary source for Bharatendu's biography is Shivnandan Sahay 1905, first published in Bankipur by Khadgvilas Press and reprinted by the U.P. Government Hindi Samiti in 1975. Sahay, a contemporary and friend of Bharatendu, records the many anecdotes and details which have been repeated in subsequent biographies. The chief English biography, Madan Gopal 1972, is not a scholarly work; however, it closely follows Sahay. R. S. McGregor's discussion (1974:75–85) is the best English-language treatment of Harishchandra's literary accomplishments.

class in Banaras in the 1860s, filling the place vacated by the Mughals and the Nawabs of Lucknow at the pinnacle of a feudal society where cultural consumption, in the form of patronage of music, poetry, and other arts, was simultaneously duty, occupation, and obsession.

Bharatendu's leadership in the literary field was a product of his own prolific energy, as well as of his fortuitous situation in the social hierarchy. His early education included training in Sanskrit, Hindi, Persian, Urdu, and English, and he was also fluent in Bengali in consequence of family ties to that region. He began composing poetry at a young age, and in his brief life-span of thirty-five years he produced many volumes of verse (almost all in Braj Bhasha), as well as eighteen plays and innumerable essays, which laid the foundation for a modern Hindi prose style. His activities in journalism involved the publication of two magazines, Kavi vachan sudha[*] and Harishchandra chandrika[*] , which spread his social, political, and literary programs to a new reading public. His network of friends and admirers extended beyond the upper echelons of Banaras society to Kanpur, Allahabad, and other northern cities, and these followers were his primary audience; several of them carried on his work in journalism and drama for a number of years after his death.

His reputation as "father of modern Hindi" was also based on his propagation of a language style that eventually became the accepted standard in the twentieth century.[16] This too was not unrelated to his social position. By virtue of not being a Brahmin, he was able to urge the adoption of a vernacular medium in place of Sanskrit. In the power structure of the time, the pandits were in fact dependent upon patrons like Bharatendu for their maintenance. (In 1870 Bharatendu organized the Banaras pandits to pay homage to the Duke of Edinburgh, and in return for publishing their poems and earning them honoraria, he received their lasting blessings and gratitude; Gopal 1972:37–42.) He appears to have been beyond the influence of their orthodoxy, at least in linguistic matters. However, as a devout Vaishnava he also opposed the infusion of Urdu expressions into Hindi, which was characteristic of the prose of Raja Shiv Prasad Singh. Shiv Prasad, who had taught Bharatendu English as a young man, became his lifelong rival, not only on the language issue but in the arena of favors distributed by the British and the Maharaja of Banaras.

This introduces the question of Bharatendu's relationship to both the British political presence in India and their social, educational, and cultural values. Bharatendu made manifest his loyalty to the British

[16] Bharatendu's testimony before the Hunter Commission (1882) on behalf of the use of Hindi in the schools is recounted in Ramadhar Singh 1973 and reveals many aspects of Bharatendu's opinions on the language question.

Crown on a number of occasions, as when he played host to the visiting Duke of Edinburgh in 1870, publicly expressed his grief at the assassination of Lord Mayo in 1871, submitted poems to the Prince of Wales during his visit in 1875, celebrated the birthday of Queen Victoria each year, or commemorated in poetry her victory in Egypt in 1882. Bharatendu used the time-honored genre of panegyric verse to express an attitude that he shared with many of the people of India, who in his own words, "have a kind of superstitious reverence for their Sovereign, so much so that they regard their Sovereign but next in reverence to God only" (Gopal 1972:181). This attitude was not disinterested but was part and parcel of a feudal code of obligations that bound the subject and the sovereign to each other. Bharatendu, like his ancestors before him, undoubtedly expected a return on his loyalty to the ruling power, and after the Duke of Edinburgh's visit he was indeed rewarded by being appointed Municipal Commissioner and Honorary Magistrate at the unusually young age of twenty. Furthermore, the proffering of allegiance to the Crown was a technique of demonstrating his superior status in Indian society, a form of competition with local nobles such as Raja Shiv Prasad.[17]

Yet Bharatendu was given to satirizing the pomp and ceremony of British rule, especially when his rivals were the objects of British attention, as in the darbar held in Banaras in 1870 ("Levi[*] pran[*] levi[*] ," V. Das 1953:938–40; Gopal 1972:102–5). He frequently tangled with local British officials and was under some sort of ban in 1880, apparently as a result of offensive editorials he had written (Gopal 1972:145). Later in his career his writings focused more frequently on the economic ruin of India, especially the outflow of cash for manufactured goods, as a result of British policies. He supported the Swadeshi movement and held that the imitation of English fashion and social behavior would lead to moral decadence as well as economic ruin for India. Despite his unsystematic and rather inconsistent political views, Indian historians have generally described him as a nationalist and social reformer, forerunner of the generation of leaders who founded the Indian National Congress (Verma 1974:377–87).

As could be expected from his education and socioeconomic class, Bharatendu's intellectual outlook was much influenced by his exposure

[17] The theme of competition among the leading citizens of Banaras to demonstrate loyalty is alluded to by Gopal where he reports of Bharatendu, "None in Banaras could really surpass him in giving expression to loyalty to the British Crown" (1972:117). The competition with Shiv Prasad helps to explain perhaps some of the inconsistency in Bharatendu's position toward the British. When Shiv Prasad was in favor with the British, Bharatendu found fault with the rulers and accused Prasad of being their lackey. On other occasions he would court the British in precisely the same manner as his rival, for his own ends.

to several great literary traditions. His knowledge of Sanskrit classics (especially of the dramatic literature), coupled with his familiarity with English literature, helped produce the characteristic stance of the Indian Renaissance man—an urge at once to reclaim the past, reform the present, and progress into the future. Bharatendu was also close to intellectual currents in Bengal and derived many of his ideas and knowledge of Sanskrit and English literary works from Bengali writers.[18]

However, his education was not confined to these "high" sources. Bharatendu was a "bi-cultural" man, to use Peter Burke's phrase (Burke 1978:28). That is, he had access to a second Indian tradition of folk and popular culture in addition to the great traditions he had formally studied. He was well versed in the oral traditions of Hindi and Urdu poetry, and he composed in several genres typically associated with Banaras, such as kajali[*] and holi[*] .[19] He is said to have sat in company with lavani[*] singers on the pavement and learned their compositions, and his own lavani s[*] were published as well (Gopal 1972:28). During festivals like the Burhwa Mangal, the riverboat festival patronized by his family, popular forms of music, dance, and poetry prevailed. Bharatendu's acquaintance with many forms of popular theatre is also apparent from his writings on drama, as we shall soon see.

But while Bharatendu participated in the popular cultural traditions of Banaras and no doubt derived relish from the activity, he seems never to have examined this cultural stream consciously or considered its role in society, except in one unusual essay. In "Jatiya[*] sangit[*] " he recommends the dissemination of published booklets of folk songs written on themes of social reform as a technique of rural uplift, much as twentieth-century development planners use traditional media in the service of modernization (Das 1953:935–38). For Bharatendu, as for the European Renaissance man, the popular side of the culture was always available for recreation and amusement. Where serious thought or literary productivity were required, however, he turned to the high literary traditions. This attitude had a great deal to do with the shape that Bharatendu's activity in the theatre eventually took.

From early on, Bharatendu embarked on the enterprise of creating a Hindi theatre movement in Banaras. His father had composed "the first [Hindi] drama of literary scope in the modern period" in 1859, but

[18] R. Stuart McGregor asserts, "The influence of Bengali literature and of views held in Bengal was clearly a dominant formative element in his work, and it is acknowledged in the prefaces to several of his plays" (1972:142). See also Mahesh Anand, who quotes Bharatendu as expressing a hope for the progress of Hindi, with the "help of her big sister Bengali, who is well-endowed and wise in years" (1978:53).

[19] For a discussion of Bharatendu's Urdu poetry and his lavani s, see Ramvilas Sharma 1973:20–22. Gopal mentions Bharatendu's 79 holi verses (1972:142), and McGregor refers to his kajali s[*] (1974:82).

there is no record of any performance of his Nahush natak[*] (McGregor 1972:92). The first drama to be presented on stage was Shital Prasad Tripathi's Janaki[*]mangal , which was put on at the Banaras Theatre (also known as the purana[*]nachghar[*] ) in 1868. The performance was sponsored by the Maharaja of Banaras, and Bharatendu himself made his acting debut as Lakshman in this play.[20] News of this performance was reported in the London-based Indian Mail and Monthly Register , and the item gives an idea of the ambience of the event:

Benaras, April 4 [1868]. . . . Last night a Hindi drama named "Janki Mangal" was acted by natives in the Assembly Rooms, by the order of his Highness the Maharaj of Benaras. Our enlightened Maharaja who generally takes an interest in all the [sic ] concerns the improvement of his countrymen, was present on the occasion, he was accompanied by Kunwar Sahib and his staff. The principle [sic ] European and native citizens were invited to witness the performances. A few ladies and many military and civil officers were present, and many rich folks of the city. (Saksena 1977:128)

Bharatendu's own dramatic compositions date from the same year, with the publication of his Vidyasundar[*] . As with most of his early plays, this was a translation, from Bengali. After writing several such plays and then freer adaptations of classic tales from Sanskrit, such as Mudrarakshas[*] , he began writing original dramas by the mid-1870s. Of his best-known plays, some employ totally contemporary settings, such as Bharat[*]durdasha[*] (1880), his commentary upon the calamities that have befallen the Indian nation, and some treat historical themes highlighting India's past glory, such as Nildevi[*] (1881). Bharatendu attempted a number of styles, from romance to farce, and he used the generic classifications of Sanskrit drama to label his plays—for example, bhan[ *] , prahasan , natika[ *] , gitirupak[*] , and so forth.

It is not known precisely how many of Bharatendu's plays were performed in his lifetime or, with a few exceptions, where and under what circumstances these performances took place.[21] However, there is

[20] Bharatendu's on-the-spot memorization of his role is one of the most famous anecdotes concerning his acting talent. See Mishra 1974:24, 791; McGregor 1974:92. (McGregor erroneously records the author as Shital Prasad Tivari.)

[21] Hindi criticism has taken the view that plays are meant primarily for reading, and hence most studies of Bharatendu consist of analyses of written texts. Not until recently has much emphasis been placed upon the performance dimension of Bharatendu's dramatic work. The problem is discussed by S. K. Taneja in his Introduction (1976:9–12). Nineteenth-century sources such as Sahay, however, do give some idea of the performance history of Bharatendu's plays. According to Sahay, five of the dramas (Vediki[*]himsa[*]himsana bhavati, Satya Harishchandra, Nildevi, Bharat durdasha, Andher nagari[*] ) were performed in places such as Kanpur, Prayag, Baliya, Kashi, Agra, and Dumrao at that time. See Sahay 1905:160–211.

abundant proof that Bharatendu was actively involved in at least three aspects of theatre aside from his role as playwright: acting, organizing dramatic societies, and writing drama criticism. His biographers describe a flamboyant and exhibitionistic streak in his temperament, and he is said to have been fond of dressing up (Saksena 1977:138–39). After his youthful performance in Janaki[*]mangal , records show that he played the role of the madman in his own drama Nildevi[*] , and also performed in Satya Harishchandra and Nildevi at Ballia with great histrionic skill (Taneja 1976:17; Anand 1978:60, description of his "overacting" by Gahmari).

Bharatendu expended considerable effort toward spreading his theatre movement among the educated elite. His organizational talents and probably his financial resources were instrumental in the founding of theatrical societies and literary clubs not only in Banaras but in other nearby cities. For example, Bharatendu was director of the Hindu National Theatre (Natak[*] Samaj[*] ) of Banaras, which consisted of a group of Bengali and Hindi speakers who met at Dashashvamedh Ghat, and it was for this society that Harishchandra wrote Andher nagari[*] .[22] He also organized the Kavita[*] Varddhini[*] Sabha[*] , which staged play performances at his own residence, and he founded the Penny Reading Club in Banaras, which engaged in regular play-reading and skit performances among its activities. In Allahabad, Bharatendu helped form the Arya[*] Natya[*] Sabha, and a number of performances took place in the Railway Theatre. In Kanpur he inspired Protap Narayan Mishra to organize the Bharatendu[*] Mandal[*] ; five dramas written by Bharatendu had been staged under its auspices by 1885. Similarly, Lucknow too had a theatre hall, the Vidyant[*] Natyashala[*] . Patna had its own Natak Mandali[*] , as did Ballia, Muzaffarpur, and Agra (Taneja 1976:17–18; Anand 1978:54–55; McGregor 1974:92–93; Shivprasad Mishra 1974: 25–26).

These societies were sustained by a group of Bharatendu's disciples, who, like him, were at once amateur playwrights, actors, and organizers. Bharatendu's literary and personal influence was clearly marked on men such as Ambika Datt Vyas, Kishorilal Goswami, and Radhakrishna Das in Banaras, Pratap Narayan Mishra in Kanpur, Kashinath Khatri in Agra, Balkrishna Bhatt in Allahabad, and Keshavram Bhatt in Bihar. Within this circle they produced each other's plays, performed for each other, and criticized each others' performances in their journals, supported by members of the local elite who had the leisure and interest to engage in amateur theatre. Performances were

[22] See Mishra 1974:25, 164. According to Taneja (1976:17) and Anand (1978:54), the National Theatre was founded in 1884, but the data of Andher nagari 's composition is given as 1881 in Mishra.

held occasionally in members' residences or in the few auditoriums that existed. Many plays of the period were never performed on stage, although some of them have been used in play readings (McGregor 1974:93). In addition to the performances mentioned above, Bharatendu's own plays were performed at his residence and in the court of the Maharaja of Banaras (Anand 1978:54).

Another context for the dramas of Bharatendu and his colleagues was the boys' school. Bharatendu's preface to Satya Harishchandra indicates that it was written with the moral instruction of boys in mind. "My friend Babu Baleshwar Prasad, B.A., has asked me to write a play suitable for the education of boys, since the dramas which I have written in shringar[*]ras [the erotic mood] are appropriate for adults but of no benefit to boys. At his request, I have composed this drama named Satya Harishchandra " (Mishra 1974:251). Similar plays compiled as school texts, to be read rather than acted, include Kashinath Khattri's Tin[*]manohar aitihasik[*]rupak[*] (1884) (McGregor 1974:93, 96). The popularity of dramatics both as an academic subject and as an extracurricular activity (no doubt inspired by British schoolmasters) is also confirmed by the early stages of modern theatre in Bengal and Bombay, where school and college clubs provided the first forum for plays in the vernacular.

The picture of Bharatendu and his theatre which emerges thus far contrasts sharply with the composite portrait of popular theatre drawn earlier in this essay. Far from being a "theatre of the common man," as some Hindi critics have claimed, this was an amateur theatre created by and for the leisured elite. The private space of the late-nineteenth-century drawing room was its distinctive setting, a closed environment that enjoined upon the spectators a refined, controlled mode of behavior. Access was limited to the socially privileged few, the private-club members and their friends. The frequent presence of British officers and their wives is another potent indicator of the degree of decorum and constraint that was observed.[23]

Furthermore, Bharatendu's theatre was still dependent upon the patronage of the court for its legitimation in the eyes of Banaras society, and courtly codes of conduct were naturally carried into the theatre milieu. The Maharaja of Banaras, Ishvariprasad Narayan Singh (1835–1889), was involved in many cultural ventures, but he was especially keen on the revival of the drama, as is testified to by his assistance to Bharatendu and his engaging a court poet to work specifically on be-

[23] Mahesh Anand states, "The theatre invented by Bharatendu was a theatre of the common people (jansamuh[*]ka[*]rangmanch )" (1978:58). Shrikrishna Lal writes, on the other hand, "It may be said that these plays were written for a drawing-room theatre, whose viewers could only be the few, highly sophisticated scholars" (1965:195).

half of the theatre (Saksena 1977:140). On the model of his king, Bharatendu's charismatic leadership provided the backbone to the dramatic societies he founded. Through the figures of authority central to these occasions, the theatre event derived its primary significance to its audience—as an opportunity for the display and affirmation of social status.

That this elite theatre was being promoted in reaction to the popular theatre prevailing in Banaras becomes clear when we turn to Bharatendu's critical writings. The practice of drama criticism was yet another dimension of Bharatendu's zeal for theatre, and reviews of productions were regular features in the pages of his journals, such as Harishchandra's Magazine . From these sources, we find that Bharatendu had witnessed performances of the Parsi theatre groups and found them not at all to his taste. The Victoria Natak[*] Mandali's[*] performance of Shakuntala[*] in Banaras in 1875 drew from him the comment that the players were "turning the knife at the neck of Kalidasa." Later he saw a Parsi production of Gulbakavali[*] , "but unfortunately nothing occurred as I had hoped" (Taneja 1976:26–27). Similar denunciations issued from Balkrishna Bhatt's pen: "Nowadays the dance of prostitutes is considered a civilized form of entertainment." The Parsi theatre was "the sure ruin of the Hindu caste and nation," or in the words of Premghan, "equal to the arrival of Kal[*] (Death)" (Anand 1978:58–59). Still, Bhatt noted, at least the civilized members of society had the sense to avoid these shows: "When the spectacle is cheap, more rakes and loafers from the city congregate than do nobles and cultured people" (Taneja 1976:27).

It is not certain that Bharatendu saw any performance of the Urdu musical, the Indarsabha[ *] , although the popularity of that drama was so well established that he could hardly have escaped it. Bharatendu published a parody of the Indarsabha in the July 1879 issue of Harishchandra chandrika[*] , under the title Bandarsabha[ *] (Assembly of the Monkeys). In the introduction to this piece he comments, "The Indarsabha is a type of drama in Urdu, or the semblance of a drama, and this Bandarsabha is in turn a semblance of it" (Mishra 1974:729). The imitation of the style of the Indarsabha here reveals a familiarity with the work, possibly through reading of the text, but perhaps also through seeing it on stage. In any case, the parody makes clear Bharatendu's rejection of the Indarsabha as a suitable model for his theatre.

Other references to popular theatre forms are scattered throughout Bharatendu's writings. One particular mention of the folk traditions of Bhand[*] and Bhagat appears in his opening verses written to accompany Shrinivas Das's play Randhir[*] Premmohini[*] . Here he alludes to the former traditions of drama in the country as "full of stupidity," which has in-

creased with the spread of troupes of "bhand s[*] , bhagatiya s[*] , and ganika s[*] " (jesters, actors, and courtesans). It is to rectify this deplorable situation that the present play was composed "full of all virtues" (Taneja 1976:104).

Bharatendu's rejection of popular traditions is most clearly stated, however, in his treatise "Natak[*] ," written in 1883. The purpose of this essay is to redeem theatre as a respectable pursuit of the educated elite, a goal which Bharatendu considered essential to his campaign to establish a viable Hindi stage. The text alternates between defining typologies of dramatic species and constituent elements in the style of Sanskrit shastra[*] , sketching miniature histories of Indian and Western drama, and making emotional appeals to the readers to shed their prejudices. "Natak" constitutes an illuminating discourse on the status of theatre at the time and the impetus for its reform, and it is to an analysis of this text that we now turn.

Bharatendu's essay is explicitly directed at an elite readership, a group he repeatedly refers to as the sabhyashishtagan[*] , sabhya meaning "civilized," and shishta[*] , "cultured" or "courteous." Underlying the essay is the assumption of the aversion of this class to the theatre. As Bharatendu notes, "Nowadays people have no enthusiasm for the practice and study of drama, but on the contrary consider it mean and low and flee from it" (Mishra 1974:777). "Natak" is thus an apologia, a defense of drama and the theatre, which seeks to win over the audience and turn its hostility into admiration and support. Bharatendu's initial tactic is to disarm his audience by conceding the justice of their point of view. He begins the essay by defining the work natak[*] (drama) as "the action of nat s[*] ," thus associating the art with the debased caste of professional actors, acrobats, jugglers, and popular performers. After further defining drama as drishyakavya[*] , loosely "poetry for the eyes," he proceeds to divide it into three types. The first is kavyamishra[*] , "mixed with poetry," about which nothing further is said. The second is shuddh kautuk , "pure entertainment," which is described as "all types of shows, such as puppet and toy shows, mime acts, juggling, dialogues during horse shows, imitation of ghosts and spirits, and other civilized entertainments." This category is clearly ranked above the third, bhrasht[*] , or "depraved," types of drama. Here the list is extensive and includes almost every type of popular theatre known at the time: Bhand[*] Indarsabha[*] , Ras[*] , Yatra[*] , Lila[*] , Jhanki[*] , etc.," as well as "Parsi drama and Maharashtrian plays, etc." The basis of the depravity of these forms is obscure; Bharatendu says only that "there is no theatricality (natakatva[*] ) left in them," and in the case of Parsi and Maharashtrian plays, he comments that they are "lacking in poetry" (kavyahin[*] ) (Mishra 1974: 749–50).

Thus from the outset Bharatendu dissociates his concept of theatre from the very forms that had popular appeal in his day, confirming the distaste with which the "civilized" class views these arts. He then proceeds to establish the legitimacy of elite drama, in contradistinction to the debased forms that have been dismissed, by linking it with the most prestigious sources of authority: the classical Sanskrit dramatists and theorists, on the one hand (Bharata and Kalidasa in particular), and the European playwrights and men of the theatre, on the other, from the Greeks and Shakespeare down to the Sahebs in the cantonment. He includes a lengthy exposition of the categories and terminology of Sanskrit drama, not so much as a framework for analysis of current plays, I suspect, as proof of the sophistication of the ancient tradition. In a similar vein, the essay closes with a description of Western theatre that is nothing more than a list of playwrights and periods, again serving to demonstrate the historical depth and respectability of the drama. In discussing his own recommendations for the "new" theatre, Bharat endu too attempts to establish legitimacy through shastraic precedent. Thus he traces the use of curtains and scene divisions to Sanskrit dramatic practice, although the popularity of these elements in his day came directly from European and Parsi theatre conventions.[24]

Although Bharatendu originally defined natak[*] as the province of nat s[*] , much of the essay is devoted to disproving that assertion. He repeatedly refers to the fame of drama in ancient times, when it was patronized by royalty and acted in their palaces (Mishra 1974:754). "These dramas were not always performed by professional actors (nat[*]log ). Aryan princes and princesses also learned them." He cites a lengthy example from the Mahabharata[*] which tells of a drama put on by the Yadav[*] princes Pradyumna and Samba (Mishra 1974:776). Later he joins to this the English example. "And if performing dramas were a bad thing, why have the English, those pinnacles of civilized wisdom, made such efforts on its behalf, and why do prominent officers every day put on costumes and perform in their large auditoriums?" (Mishra 1974:778). He regrets that "people adept at acting are considered ordinary drum-beating nat s and are hated" (Mishra 1974:777). These negative attitudes, to Bharatendu, simply indicate a defective upbringing (kusamskar[*] ), based on ignorance of the illustrious history of drama in India and the West.

[24] Mishra 1974:756–57; Taneja 1976:42. Bharatendu's fondness for painted curtains seems related to the fascination with perspective that characterized the Company school of miniature painting, which was much in vogue with the Banaras gentry (Sukul 1974:60–61). It is curious that Bharatendu found fault with the folk theatres of Raslila[*] and Tamasha[*] , accusing them of lack of realism, because they did not use backdrops and curtains.

An important element of Bharatendu's revision concerns the aims of drama. Alongside the traditional rasa s, shringar[*] (eroticism), and hasya[*] (humor), and the conventional motive of kautuk (surprise), he joins samaj[*]samskar[*] (social reform) and deshvatsalta[*] (love of country) as suitable ends to be aroused by a play (Mishra 1974:754). The latter two aims operate with special force in the present period, when every play must have a moral or an educational purpose. If such a purpose is lacking, the cultured class will not respect the work (Mishra 1974:773). This moral purpose must be especially apparent at the conclusion of a drama; the evil characters must be punished and the good rewarded (Mishra 1974:774). Drama ought properly to be ras rupi[*] updesh , instruction in the form of aesthetic delight. When it is such, it has tremendous power to reform society, because of the irresistible force of the educational message made pleasant through entertainment. Bharatendu predicts a moral renaissance from the propagation of plays:

Just as men addicted to prostitutes come to hate their behavior by seeing actors dressed as men addicted to prostitutes, . . . so are drunkards made to experience their sorry situation by those impersonating drunkards, and in the same way gamblers, liars, debtors, those who oppose their brothers, misers, spendthrifts, harsh speakers and fools will become conscious simply by the depiction of their sorry plight . . . and, becoming cautious by virtue of this pleasant form of instruction, will avoid these evils. (Mishra 1974:777–78)

The unique facility of drama as an instrument of social reform was a cornerstone of belief shared among the playwrights of Bharatendu's day (Taneja 1976:16). It was the trump card in Bharatendu's case against the opponents of theatre; to obstruct the progress of drama meant to stand in the way of the moral regeneration of the nation.

The emphasis on the didactic purposes of drama led Bharatendu to modify the rules inherited from Sanskrit theory. For example, he restricted the types of heroines in the "new" drama to svakiya[*] women only, that is, women who are loyal to their husbands. There was no place on his stage for a parakiya[*] , a woman who belongs to another. So too the use of music was circumscribed, and of course the arousing dance displays of the popular theatre were curtailed. Bharatendu also recommended a reduced role for the vidushaka[ *] , the clown whose mocking of authority is almost a universal in Indian theatre. Hand in hand with these changes, Bharatendu espoused certain realistic conventions that had previously been absent from the Indian theatre, except for the recent Parsi stage. He emphasized the unities of time and place and advocated the use of painted backdrops and stage props to represent the changing settings of acts and scenes. The Sanskrit and folk dramatic practice of establishing the place or time by verbal reference was

scorned. He stressed the literal correspondence of costumes to the state of the characters at the time of the action—for example, rags for King Harishchandra when he is working on the burning ghat. He also allowed for the mixing of moods, or rasa s, a rigid taboo in classical Indian theatre, especially in the case of plays with tragic endings.

The prescriptions of Bharatendu's treatise, written at the end of his life after the composition of his dramas, are not uniformly followed in his own dramatic works. Elements of various folk theatre traditions are visible in some of his texts, pointing to a still incomplete bifurcation of drama into "popular" and "elite."[25] However, the kind of theatre experience that was in the process of formation was fundamentally different in structure and function from the earlier popular theatre. Bharatendu's theatre was moving in a clear direction: away from the openended, improvisational, stylized, multivalent theatre of the Svang[*] and Parsi stage, and toward a controlled, unambiguous, realistic, morally edifying model of theatre. Not only was the social milieu of theatre now pervaded by values of civility and refinement; the means and ends of theatrical representation were purged to eliminate all that was vulgar. Theatre was henceforth an unabashed arena of instruction, whether its actual locus was the schoolhouse or the parlor.

To students of modern Indian literature, the large dose of didacticism and moral idealism that accompanied Bharatendu's theatre program comes as no great surprise. The same infusion of reformist sentiments, coupled with a rigorous purging of eroticism, fantasy, and humor, accompanied the development of other literary genres, such as poetry and fiction, as they crossed the boundary into modernity. Bharatendu's larger corpus illustrates the split. It contains the sober, message-laden "modern" dramas, as well as volumes of flippant, sensuous lyric poetry that adhere to the traditional type. What was "modern" in literature had less to do with turning one's view toward "real life" (the heroes and heroines of Bharatendu's plays were still the ideal princes and princesses of yore) than toward affixing a conscious purpose to the literary work, making the work subservient to the larger task of the betterment of "society." What writers like Bharatendu

[25] Susham Bedi, Krishna Mohan Saksena, Mahesh Anand, and others have made rather inflated claims regarding the folk elements in Bharatendu's plays. To cite one extreme example, Nildevi[*] and Andher nagari[*] have been characterized as written in Nautanki[*] style (Bedi 1984:31–36), although the texts of these plays contain none of the standard meters of Nautanki and bear no resemblance to the Svang texts of the same period. More plausible are the identifications of various scenes, characters, and conventions, which are reminiscent of the Parsi stage. Despite the vehement scorn Bharatendu expressed for the Parsi companies, he was unable to free himself completely from its dominance in the theatre world in which he lived and worked. See Taneja 1976:26–32; Anand 1978:59–60; Saksena 1977:133–38.

meant by "society" is another topic; it still referred primarily to the sabhyashishtagan[*] , the elite.

The reformist spirit that permeated Bharatendu's theatre in Banaras and spread from there may have been a result of growing Arya Samaj[*] influence. Dayanand Saraswati first visited Banaras in 1869, and as early as 1870 his addresses stirred Bharatendu to compose pamphlets deriding "the naked Dayanand of unknown caste" (Gopal 1972:32). Bharatendu initially rejected Dayanand's claims to religious authority and, as a Vallabhite, refuted his denunciation of idol worship and sanatana[*] practices. However, Dayanand later became a contributor to Harishchandra's Magazine , and the edge of their quarrel seems to have worn off. Many of Dayanand's positions on child marriage, widows, temperance, and education were probably acceptable to Bharatendu. Even though Dayanand made few converts at the time, the impetus to self-purification in Hindu society permeated educated circles in Banaras in consequence of his continued preaching. The same species of influence emanated from Bengal in the form of the Brahmo Samaj; Bharatendu may have come into contact with it indirectly through Bengali authors who had imbibed its teachings.

The reform of the more exuberant and potentally licentious aspects of popular culture was a certain component of Arya Samaj philosophy. The Aryas condemned the singing of "indecent songs" on ceremonial and festival occasions, and they introduced a purified form of the Holi festival which excluded all spontaneous merriment and focused upon the Vedic havan ritual. They also abolished the performances of dancing girls at Arya Samaj marriage ceremonies (Jones 1976:95, 99). According to the Vatuks, "The movement's founder, Dayanand, was quite explicit in his writings about the evils of dramatic performances" (Vatuk and Vatuk 1967:48). Proselytizing efforts by the Arya Samaj in Haryana in recent years have included denunciation of the local folk drama form Sang[*] (another descendant of ninteenth-century Svang[*] ) and concerted efforts to replace it with the more salutary songs of Arya Samaj bhajanmandali s[*] .

By way of comparison, we may refer briefly to the tremendous opposition toward the popular theatre voiced by Plato, the Christian Fathers, the Puritans, and any number of other reformist movements throughout Western history. The "antitheatrical prejudice," as Jonas Barish puts it, is a universal phenomenon, singularly oblivious to transformations of culture, time, and place (Barish 1981:4). As Barish shows, the most vehement attacks against the corrupting influence of theatre have tended to occur when the theatre was at a height of popularity. From this it is reasonable to infer that Bharatendu's denunciation of the Indarsabha[*] , Lila[*] , Tamasha[*] , and so forth, as bhrasht[*] occurred

not because they were almost extinct, as has been generally thought, but precisely because there was an intense degree of public devotion to these spectacles. Swept along by the puritanical fervor of the Arya Samaj[*] , Bharatendu fortunately did not call for a complete ban on playacting, as the English Puritans did. However, he embarked on a course that served to disengage the modern Hindi theatre from its very roots in the traditions of the people.

Conclusion