Chapter Five

The First Figure-scenes in Greek Art

The change of subject at this juncture may seem abrupt; but there is an underlying unity of theme behind the disparity of subject matter. Classical archaeology has been criticized within the archaeological world for its isolation from the mainstream of archaeological research, yet in my view it is placed to reenter that common tradition from a position of strength. Similarly, classical archaeology stands accused of applying outmoded methods in art history, yet here, too, as I hope we shall see, it can offer something distinctive to the field as a whole. In terms of sheer quantity, the volume of past work in ancient art history is so huge that to omit the study of Greek art from an investigation of Greek archaeology would either show an absurd lack of proportion or, if done as an act of policy, be an example of precisely the kind of doctrinaire compartmentalization that I have been deploring. It seems to me a strength, not a weakness, of classical archaeology that it should automatically be taken to include the study of art, and that the same people should often choose to practice, and be required to teach, in both fields. The special contribution the subject can make to art history derives from this very circumstance, that the same people can be expected both to offer the artistic analysis and to have mastered the archaeological evidence.

Judged by its own standards, the past tradition of study of classical art, in addition to its volume and duration, has been distinguished. Yet criticisms of it cannot, and should not, be silenced. Let me quote one of them, which is so comprehensive that it can perhaps do duty for a whole range of more specific charges. It is the statement made in 1966 by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, a distinguished exponent of the subject himself, that classical archaeology is guilty of "the almost total abandonment of art history."[1] This is the sort of charge that may tempt the classical archaeologist, as his wife exhorted Job, to curse God and die. The vast investment of time and scholarship in the study of Greek and Roman art has shown no sign of diminishing, let alone coming to an end, in recent years; its scale and preponderance within the discipline are intermittently a subject for disparagement among the latter's critics; if, after all that expenditure of effort, the result cannot even be dignified by the name of art history, then what purpose has it served? It will help if I clarify a little the context of Bianchi Bandinelli's comment: he was attacking what he felt to be the obsession with classification and dating, and the search for parallels and attributions, pursued by classical archaeologists to the neglect, often the exclusion, of true art history. To this, his numerous opponents would at once have replied that such classificatory work is an absolutely indispensable first step in a field such as classical art, which is relatively ill-documented by the standards of later art history, before anything in the nature of critical interpretation can be attempted. But the point of the criticism is that this "preliminary" work, on its own, seems to exhaust the time, the scholarship, and apparently the interest of the classical art historian. One may venture to suggest, again, that

[1] R. Bianchi Bandinelli, "Quelques réflexions à propos des rapports entre archéologie et histoire de l'art," in Mélanges offerts à Kazimierz Michalowski (Warsaw, 1966), 262. For a parallel opinion about the study of Greek vases in the past century, see H. Hoffman, "In the Wake of Beazley," Hephaistos 1 (1979): 61–70, especially 61 on "the virtual exclusion of inquiries concerned with the meaning, function and cultural relevance of these objects."

psychological factors are at work: the appeal of this kind of study to the convergent intellect, with its appetite for the single, right answer, will be apparent.

Another kind of rejoinder might today be given to Bianchi Bandinelli's charge: that, in the fairly short time since he brought it, classical archaeologists have discernibly mended their ways; that true classical art history is now alive and well, practiced indeed by several dissident schools simultaneously. One symptom of this revival might be that discussion of an art-historical problem of especial importance to Greek art has come vigorously to life after some two generations of relative neglect. The problem is that of the relationship between narrative and artistic representation. There are several reasons why this question is central to Greek art; two of them may be illustrated by two of the more emphatic claims that have been made for Greek artists in this field. First, John Carter's proposition, in the course of a valuable article on the subject in 1972, that the Greeks virtually invented narrative art;[2] second, Gombrich's well-known argument that what lay behind the historic appearance of naturalism in Greek art was "the character of Greek narration": that a special gift or quality, hitherto revealed mainly in the literary medium, inspired the sculptors and painters of Greece to create the achievement Gombrich called "The Greek Revolution."[3]

It was this theory of Gombrich's that Carter used in discussing his own material, notwithstanding that he himself was writing mainly about Geometric art of the eighth century B.C., whereas Gombrich's "Greek Revolution" was something that he explicitly dated between the limits of about 550 and 400 B.C. Both writers are clearly impressed (as innumerable others have been) by the frequency in Greek art of scenes with a narrative content, and by the fact that, in the majority of these scenes, that content is spe-

[2] J. Carter, "The Beginning of Narrative Art in the Greek Geometric Period," BSA 67 (1972): 25–58, especially 26.

[3] E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion (Oxford, 1960), 110; cf. 99.

cifically mythical or legendary. As always in this field, one has to be very careful about one's terminology: it would be possible, for example, to define "narrative" either in a sense so narrow that it would greatly reduce the body of material open to discussion; or in a sense so wide as to make it a false claim that myth and legend preponderate, as I have said that they do. As a matter of fact, today one has to be careful about a great deal more than one's terminology; for we must reckon with new interpretations of these same phenomena, which not only differ from, but may even entirely exclude the approach we have begun to consider.

The Structuralist interpretation comes under this heading. Anyone familiar with the Structuralist view of myth—that a given myth is made up of all its variants, that the narrative sequence and content of all or any of these variants is unimportant, and that what matters is the structure of the myth, reflecting as it does the structure of the human mind—and more especially, anyone who has read the remarkable sentences in Lévi-Strauss's retrospective survey of his own work on myth, about the study of myth making possible a "conspiracy against time," even the "abolition of time"[4] —may not be surprised at what is coming next. It is clear that such a doctrine of myth will have some repercussions on one's view of mythical narrative in art. If time and temporal sequence are peripheral to the nature of a myth, then they are not likely to be judged important ingredients of a myth-picture. But where will this leave the wide range of scholarly work that has been devoted to the treatment of temporal sequence in Greco-Roman art? Such work has taken as its first field our richest corpus of evidence, Greek vase-paintings; and, as I have already hinted, it has been notably concentrated in two periods, the generation after the appearance of Carl Robert's Bild und Lied in 1881, and our own generation. One strand of this investigation has been focused on that interesting device,

[4] C. Lévi-Strauss, L'Homme nu (Mythologiques 4) (Paris, 1971), especially 542.

adopted by some Archaic vase-painters, whereby a single picture combines a series of episodes in a story as if they were simultaneous, but—a very important restriction—without allowing any single figure to appear in the picture more than once.[5]

This practice has, at different periods, been called the "complementary" (komplettierend ), "simultaneous," or "synoptic" method. One of the more interesting results of the study of this method has been the revelation that such a way of conceiving a myth in visual terms was, at least as far as Greece was concerned, the original innovation of Archaic artists (and quite possibly of vase-painters specifically). It is significant that the examples of Aegean Bronze Age art in which the treatment of successive episodes of a story has been detected—for instance, in fresco and inlay work,[6] and in the series of gold rings discussed in the 1941 Sather Lectures of Axel Persson[7] —have all been claimed to represent a quite different method or methods, in which either the principal figure (or figures) are repeated in order to show the passage of time, or the same end is achieved by showing a row of different figures in the postures that would be successively occupied by one figure as time passed.

This technique, even if correctly diagnosed, is uncommon in later Greek art; whereas the "simultaneous" or "synoptic" method is, for a time, characteristic of it. The classic illustration, which I apologize for showing yet again, is an Attic black-figure cup of about 550 B.C. in Boston that portrays the story, familiar from the tenth book of the Odyssey , of Circe's transformation of

[5] See my Narration and Allusion in Archaic Greek Art (11th Myres Memorial Lecture, Oxford, 1982) in a somewhat oversimplified form.

[6] See J.L. Myres, "Homeric art," BSA 45 (1950): 233, on the "Taureador fresco" as showing the successive positions of a single acrobat (cf. A.J. Evans, The Palace of Minos , vol. 3 [London, 1930], 22, fig. 156); and compare Myres, 245, on the "Lion hunt dagger-blade," showing "phases through which any one warrior may pass."

[7] A. W. Persson, The Religion of Greece in Prehistoric Times , Sather Classical Lectures, no. 17 (Berkeley, 1942), 28–30, 47, 80–81. Figures 49 and 50 in this volume illustrate two of these.

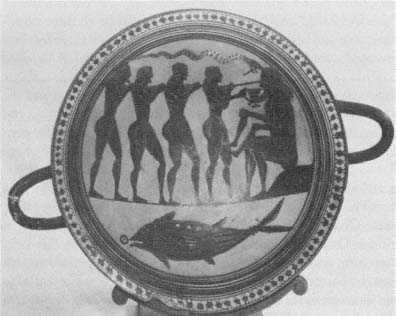

Figure 35.

Attic black-figure cup (Boston), with scene of Circe and Odysseus's sailors.

Odysseus's sailors (Figure 35).[8] The picture, in some respects very faithful to the Homeric account, shows Circe mixing the potion that will transform the sailors into animals, that will lead the suspicious Eurylochos to steal off and give the alarm, that will provoke Odysseus to come and threaten Circe into reversing the spell—yet all these three subsequent episodes are already shown taking place (right and left of center, far right, and far left respectively). To the layman, "synoptic" pictures of this kind seem to represent time defied; to the Structuralist, they show something rather different (and more "Structuralist"): time disregarded.

In presuming to represent their view here, I am in something of an embarrassment. Lévi-Strauss himself has written extensively about art, but his well-known predilection for studying "cold," as opposed to "hot," or historically documented, cultures means that there is no treatment by him of the kind of work that we are looking at here. Nor have I even been able to find specific statement of the doctrine in question in the writings of the "Paris School" of classicists, who under the recent leadership of Jean-Pierre Vernant have turned their attention to many such prob-

[8] Cup, Boston 99.518; J.D. Beazley, ABV 198.

lems. The truth is that I am relying on oral expositions, given by adherents of the Paris School who are also in sympathy with Structuralism; and if I am doing less than justice to a view I actually find very persuasive, then I trust that matters will shortly be set to rights in print. The central assumption of the argument, as I understand it, is that the whole notion of "time" in the context of such works, as employed for instance in my description of the Circe picture just given, is an anachronistic modern importation; that the artist himself was not conscious of it, and therefore equally unconscious that he was, to the literal-minded spectator, defying it. All that he meant to show, by portraying different characters involved in different actions that, in the story, took place at different times, was merely the distinctive and characteristic attribute of each figure. Circe is the sorceress, the sailors are the victims and so on, and each must therefore be given his or her essential action or attribute; the inherent structure of the myth, which is thereby portrayed, is a timeless one. Any apparent violation of time was thus an accidental byproduct of the artist's concern with another, to him more important, question. A possible implication is that much the same was true of later artists who intermittently handled similar themes in a similar way, right down to the invention of photography, which is mainly responsible for alerting man's sensitivity to these apparent "violations" of the unity of time. If it is true that the producers of such scenes and their publics wished only to see each character given his or her individual action or epithet, then this will deny to such pictures the strict status of "narrative art"; indeed the doctrine could be pursued to the point of denying the possibility of true narrative art at all.

Let me at once admit that this theory, when applied to a number of works of Greek art, gives convincing results. It can equally well be applied to another, quite separate, category of ancient pictures that are non -episodic: that is to say, that appear to respect unity of time by showing only actions that happened, or could have happened, at the same moment in a given sequence

of episodes. These pictures are less frequent, or less conspicuous, in Archaic Greek art, but they become almost the norm in the full Classical period, when the passion for presenting eventful legendary tales in their full detail had somewhat waned. Here, the Structuralist explanation will be that the apparent "unity of time" is but a coincidence: the characteristic actions or epithets given to each figure happened, in this case, to be compatible with one another in temporal terms, according to the accepted version of the story. Only if we can detect independent signs of a concern with temporal issues on the artist's part—and this we are much more likely to be able to do with the first, "synoptic" type of picture than with the second kind just described—are we entitled to contest an interpretation that conforms as well as this to what we can actually observe. I wish now to draw attention to a few cases where I think we can detect such signs; but I should say, in anticipation of the main argument of this chapter, that for some purposes this apparent polarity of views need not be resolved, but can be by-passed. Whether we believe that the Archaic artists were defying time or merely ignoring it, the end-product of their endeavors remains unchanged, and this end-product is susceptible of other kinds of analysis in which the question of the thought-processes of the artist is not a crucial one.

We have already referred to several different ways in which ancient artists, at least on a naive reading, appear to have set about "telling a story" in visual terms: by compressing several successive episodes into a single moment; by choosing a single moment in the first place; or, in the Bronze Age, by showing successive episodes as successive through repetition or multiplication of figures. At the risk of complicating things still further, I should mention here yet another method that is sometimes used. This involves representing a series of exploits of one heroic figure, with a separate panel or picture being devoted to each exploit; in this case, of course, the hero reappears in each scene. The prime medium for this treatment is architectural relief-sculpture, but it also appears, slightly adapted, in a group of vase-paintings that

show some of the deeds of Theseus. It has been noticed, for example, that in the twelve sculptured metopes of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia that portray the twelve labors of Herakles, or in the group of Attic red-figure vases just mentioned that illustrate Theseus's exploits, the artists do not respect the "official" temporal sequence in which the deeds were supposed to have been performed, but instead allow themselves either to rearrange the order to suit their artistic purpose or to omit episodes no less important than the ones they show.[9] This shows that there were at least some contexts in which time was, to say the least, not an ever-present subject of concern—just as the Structuralist view would lead us to expect.

The real test for the validity of that view comes, however, in the context of the "synoptic" pictures with which we began. Whereas in the case of the "separate panel" treatment, it is only the moderately well informed spectator (ancient or modern) who will be aware that there is any violation of the accepted time-sequence, with the "synoptic" treatment it is temporal logic that appears to be infringed, and certainly any modern viewer who stops to analyze the picture for a minute or two will become aware of that violation. The question that faces us is whether the artist himself, and his contemporary public, were conscious of any such thing. Let us use the Structuralist language of "attributes" or "epithets" in approaching one instance that is representative of a larger group of pictures: those in which a single figure is given more than one "attribute." On a Lakonian black-figure cup, once again of about 550 B.C., we see one of the more elaborate vase-pictures of the story of the blinding of Polyphemos (Figure 36).[10] We are shown the Cyclops devouring the limbs of

[9] Compare V. Dasen, "Autour du dinos de Néarchos: Essai sur la bande dessinée chez les anciens," Etudes de Lettres (1983), pt. 4, 55–73, especially 64–65.

[10] Cup, Paris, Cabinet de Médailles 190; C. M. Stibbe, Lakonische Vasenmaler des sechsten Jahrhunderts v. Chr. (Amsterdam and London, 1972), 285, no. 289.

Figure 36.

Lakonian black-figure cup (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale), with scene of Polyphemos and Odysseus.

Odysseus's sailors, while about to drink from the cup that will induce the drunkenness that will cause him to fall into the sleep that will enable Odysseus and his surviving comrades to blind him—as they are also shown doing. On the traditional analysis, which we used in first approaching the Circe cup, the artist has here compressed three of the five successive episodes just listed into a single moment. For the Structuralist, all that he has done is to give two "epithets" (roughly speaking, cannibalism and drunkenness) to Polyphemos, and another (the stake for the blinding) to Odysseus and his companions.

We may wish to protest here that the temporal "collision" is too obvious for anybody to miss; but in saying this we may be merely revealing our anachronistic prejudices. A better approach

may be to pose a question: Polyphemos may be "the cannibal," "the drunkard," and "the victim"; but can he be all three simultaneously and (more important) inherently ? Are all three features essential components of the structure of the myth? A detailed analysis of the numerous variants of this story by Claude Calame suggests otherwise. The act of cannibalism, he suggests, and the act of retribution that avenges it, the blinding, are balancing and critically important features of any version of the story. By contrast, the role played by the cup of wine is not so obviously essential to the structure; Polyphemos (with his non-Greek counterparts) is not "always" the drunkard, either in the sense that this detail is present in all versions, or in the more trivial sense that, in the Greek version, he is "always" drinking (on the contrary, in Homer Odysseus's wine is a special treat for him). In this case, therefore, one might ask which is the more likely explanation: that the painter included all the attributes that he felt essential to the characterization of his figures; or that, having decided to show the cannibalism and the blinding, he felt that the transition between the two would be too abrupt unless he inserted an intermediate temporal stage in the form of the cup (at the cost of some awkwardness, since Polyphemos has no free hand with which to hold it).[11]

There may still be difficulty in making a choice between the alternatives, so I shall turn to another, slightly later picture in which this same element of "multiple epithets" applied to a single figure is present, together with other, rarer features. It is the scene running continuously round the shoulder of an Attic black-figure hydria by the Antimenes Painter (about 520 B.C.), and it is one of the most arresting new works of Greek vase-painting to come

[11] See C. Calame, "La Légende du Cyclops dans le folklore européen et extra-européen: Un Jeu de transformations narratives," Etudes de Lettres (1977), pt. 2, 45–79, especially 64.

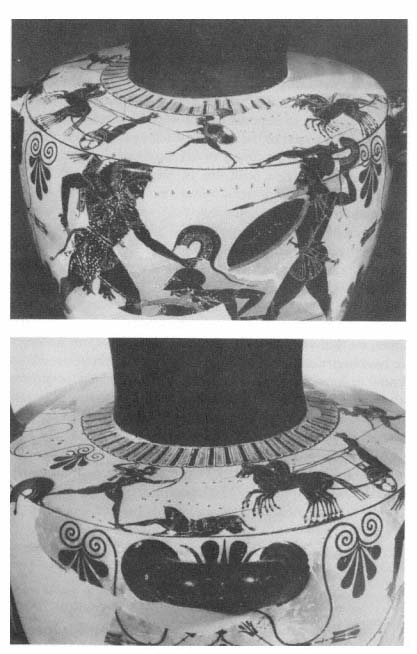

Figures 37, 38.

Two views of the scene on the shoulder of an Attic black-figure hydria

(Basel, private collection), with scene of Neoptolemos at Troy.

to light in recent years (Figures 37–38).[12] The subject is generically common but individually very rare: the aristeia , or prowess in battle, of Neoptolemos at Troy, which was treated in the lost epic called the Little Iliad . From the right (at first sight surprisingly, since the left is the "winner's side" in Attic vase-painting), Athena runs up to support her protégé Neoptolemos, whose chariot follows next to the left; to the left again, we see, first the hero's handiwork, the corpse of his most noted opponent, the Trojan ally Eurypylos, with one of Neoptolemos's spears still fixed in his body, and with his armor already stripped off him by his conqueror. This was Neoptolemos's hardest victory, singled out for mention by Odysseus when he tries to cheer the ghost of Achilles by regaling him with his son's more recent exploits (Odyssey 11. 520). To the left again, we at last see Neoptolemos himself, on foot, in the very act of spearing in the back a fleeing charioteer, who cries out and throws back his head in agony. Whose charioteer this is is not absolutely clear, because next to the left again we find another fallen enemy, Helikaon, whom we know to have been the son of the Trojan Antenor, but whom we did not know to have been killed at Troy, by Neoptolemos or anyone else: indeed we hear from Pausanias of an incident in the epic cycle when his life was spared by Odysseus after he was wounded, and from Martial that he escaped after the fall of Troy and became one of the founders of Patavium in northern Italy. In this picture, however, as Mark Davies has pointed out, the signs are that Helikaon is dead.[13] Finally, at the far left and from the left, Apollo advances brandishing his bow to put a stop at last to

[12] For knowledge of this scene, painted on the shoulder of a still unpublished hydria in Basel, I depend on the photographs in K. Schefold, Götter-und Heldensagen der Griechen in der spätarchaischen Kunst (Munich, 1978), figs. 339–40, and on the comments of the scholars mentioned in the next footnote.

[13] See M. I. Davies, "The Reclamation of Helen," Ant.K. 20 (1977): 75 n. 12; cf. also the views of J. D. Beazley, Paralipomena (Oxford, 1971), 119–20, no. 35 bis. The interpretations do not coincide with those of Schefold's text and captions (cited above, n. 12), 252–54 in all particulars—for example as to the exact role of Apollo or the attribution of chariots to warriors.

Neoptolemos's triumphant progress; thus we find the explanation for the fact that the hero's direction of progress has been from right to left—in the last resort he will not conquer. Apollo, the protector of Troy, will stop him from taking the city (just as he stopped his father in similar circumstances at the end of book 21 of the Iliad ).

Two things about this picture suggest to me that the painter has handled the dimension of time with conscious deliberation. First, the killing of the charioteer is an instantaneous representation of the moment of death, set in the middle of a sequence of three killings. Second, the temporal sequence unrolls from right to left, and has to occupy an appreciable length of time. Neoptolemos has had time not only to spear Eurypylos, but to strip him of his armor. Epic heroes use two spears, and it is with his second one that Neoptolemos is just now killing the charioteer; he must, however, retain this one in order to encompass the death of Helikaon, in whose body a spear (presumably this same one) is again fixed. Finally, Neoptolemos will be halted by Apollo. That this is the sequence of events is confirmed by a partial duplicate of this scene by the same painter: on another hydria, in Würzburg,[14] an almost identical Neoptolemos is spearing an almost identical charioteer, while the presumed Helikaon, wounded but still alive, crawls vainly in the direction of his doomed chariot and driver. Thus, the death of Helikaon should be set in the future relative to that of the driver. The temporal sequence runs consistently from right to left. On the Structuralist view, this becomes something of a coincidence: the artist wished only to portray Neoptolemos's prowess by giving him three victims, and just happened to arrange the three, plus the fourth and final episode with Apollo, in a right-to-left order. The last point, together with the observation about the spears, and the central emphasis on the moment of the charioteer's death, seem all to tell in favor of the other interpretation—in this case . But it would still be open to

[14] Hydria, Würzburg 309: ABV 268, no. 28.

the Structuralist to respond that this is a very unusual vase-painting: we are not used to seeing a single instant in a narrative sequence given this dramatic emphasis in Archaic Greek art.

The most that I have succeeded in showing is that some artists, sometimes, look as though they were conscious of the fact that, in using the "synoptic" method of presenting a story, they had to manipulate time. This point may perhaps be reinforced by one last example, taken from the much smaller group of works in which the chosen subject matter was taken not from legend but from history. In his description of the mural of the Battle of Marathon in the Stoa Poikile at Athens, Pausanias (1. 15.4) says that "at the beginning" the two sides were shown coming to grips; "things are about evenly balanced. But in the heart of the battle the barbarians are in flight . . . and the painting comes to an end at the Phoenician ships." Presumably, the direction of the sequence from the "beginning" to the "end" was left-to-right; but irrespective of this, it is clear from Pausanias's description that he could understand the time-dimension as running from one side to the other, and the painter must have intended him to do so. We may also note a telling feature of the description: the leading figures on the battlefield, of whom there were several, were evidently shown only once each—exactly as we have found to be the rule in the "synoptic" vase-paintings. The conclusion seems clear that an artist, working in this much grander medium, still felt constrained to observe the rules of a "synoptic" representation; and that his subject, which required him to present a fairly recent historical event in circumstantial and more or less accurate detail, also compelled him to use the time-dimension clearly and consciously.

Whether or not the examples that I have given prove to be representative of all Archaic Greek art, the fact remains that in all genuine uses of the "synoptic" method, unity of time is not present: the statement remains empirically true even if it is merely a statement of modern descriptive attitude. This is the point to be borne in mind as we turn our search backwards in time in an

attempt to seek out the origins of this artistic method. For this, I think we have to go back to a date some two centuries earlier than that of the three black-figure vases that we have looked at—that is, to the time of the first massed figures in surviving Greek art, on the vases of the Late Geometric style. The interpretation of these scenes has formed the subject of intense discussion in recent years, but it remains one of the unresolved disputes of classical art history. This very fact, that the deployment of traditional approaches has resulted not in a consensus but in a stalemate, is part of my reason for choosing it as the main theme of this chapter. Can we make use of the circumstance mentioned earlier—that the handling of the archaeological context of these Geometric vases, and the interpretation of the scenes on them, rest with the same group of people—to start building a truly integrated analysis of them?

First, I recapitulate the current state of the debate over the interpretation of the Geometric scenes. Each of the two main schools of thought—those who see in these pictures the evocation of a heroic past, and those who read them as portrayals of contemporary life—bases its arguments partly on analogy with literature and with Greek art of the ensuing period that is better understood, but ultimately, on an appeal to common sense credibility. Each, as a consequence, seems to find in the other's conclusions a violation of such credibility. Attempts to find a mediating, compromise solution, either on a simple level (that some of the scenes are heroic, some from real life), or on a more sophisticated one (that, from the moment of their creation, the scenes were meant to be ambivalent) seem destined for rejection by both sides, as is often the fate of the peacemaker's efforts.[15] If there is any way of establishing a common ground of objective

[15] See most recently J. Boardman, "Symbol and Story in Geometric Art," in Ancient Greek Art and Iconography , ed. W. Moon (Madison, Wis., 1983), 15–36, who rejects compromises such as those proposed by Isler and Kannicht (cited below, n. 24).

observation and verifiable hypothesis, then this should be done without further delay.

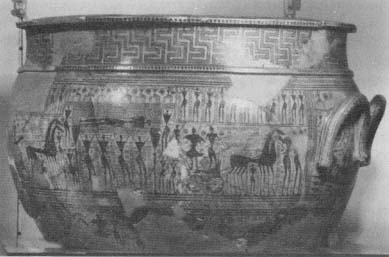

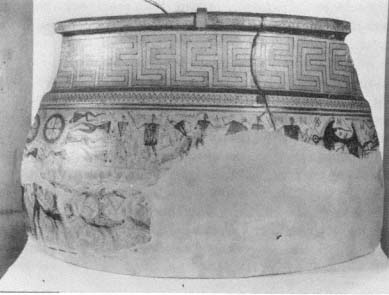

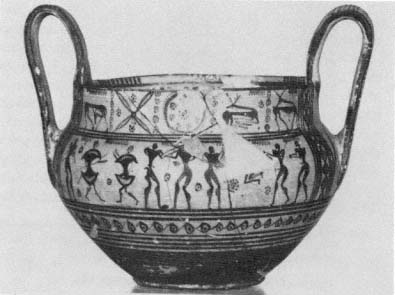

Let us begin with a statement about the context of these pictures that at least has the merit of being quantitative. Large crowd scenes with massed figures are, in Geometric art, confined to funerary vases, many of them apparently markers that stood over graves, visible to the passerby. Two subjects predominate: the prothesis , or lying in state of a corpse before its burial (Figure 39), and the battle scene, whether on land, on sea, or amphibious (Figure 40). Both subjects have been treated in valuable monographs by Gudrun Ahlberg, and from her catalogues we learn that fifty out of fifty-two prothesis scenes known in 1971 were Attic, and twenty-six out of twenty-eight battle scenes: 96 and 93 percent respectively. Moreover, their scope is not only restricted geographically, but heavily concentrated in time: as Ahlberg observes in her book on the battle scenes, the great majority of them (sixteen out of the twenty-two that are readily datable) come from a single Athenian workshop whose activity may have lasted little more than a decade, around 750 B.C. on the conventional dating.[16] We are looking, in other words, at the work of a tiny group of craftsmen, over a short space of time, in a single location. With the prothesis scenes, the time-span is longer and the diversity of style, partly but not entirely because of this, greater; yet the range of composition is, if anything, rather narrower than with the battle scenes—the essential formula for a prothesis on Attic vases, once established, changed little over the two generations of its prevalence.

So much for the producers; what of their customers? Another striking feature of the Late Geometric crowd scenes is that the great majority of them have been known, or at least in existence

[16] G. Ahlberg, Prothesis and Ekphora in Greek Geometric Art , Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology, no. 32 (Göteborg, 1971), and Fighting on Land and Sea in Greek Geometric Art , Skrifter utgivna av Svenska Institutet i Athen, no. 16 (Stockholm, 1971). For questions of production, provenance, and date, see Ahlberg's catalogues in Prothesis and Ekphora , 23–29, with references, and cf. 281 for comment; and in Fighting on Land and Sea , 12, 25–26 with references, 39-41, 66.

Figure 39.

Fragment of Attic Geometric krater (Paris, Louvre A 517).

Figure 40.

Fragment of Attic Geometric krater (Paris, Louvre A 519).

above ground, for about a hundred years. More recent additions to their number have come in a very slow trickle, and consist mainly of relatively late and simplified prothesis scenes. The bulk of the battle scenes—again, about three-quarters—can be shown, or strongly suspected, to have been found in the excavation of a series of rich graves on the modern Piraeus Street in Athens in the last thirty years of the nineteenth century, where they often featured (as in Figures 39 and 40) on vases erected as markers. Even though the pieces have become scattered among a number of museums in several countries, their essential unity was demonstrated some years ago when scholars found that fragments in different collections actually joined.[17] This observation strongly reinforces our previous one about the concentration in time of the battle scenes: most of these pictures were produced not only by, but also for, a handful of people—the family group or groups that used the Piraeus Street cemetery. The elusiveness of closely comparable pottery in the hundreds of Athenian graves of similar period excavated in more recent years gives a powerful hint of the exclusiveness, in both social and local terms, of the group that bought, and possibly commissioned, these vases.

All of this acts as a deterrent, in at least two ways, to any attempt at unraveling the meaning of the scenes on the vases. First, the group for which they were destined may have been utterly unrepresentative of contemporary society in Athens, let alone the wider Greek world; so that inferences drawn from what we know from other sources of beliefs and practices among the Greeks at this time, and from what we see on other contemporary art, may be misleading. Ideally, such inferences should be derived from the associations and burial circumstances of these same few graves; but unfortunately, because of the very early date of their discovery, this information is mostly lost for ever. The second deterrent is that we cannot necessarily expect the fu-

[17] Cf. J. N. Coldstream, Greek Geometric Pottery (London, 1968), 29–33, with references to the earlier work of E. Kunze (1953) and F. Villard (1949 and 1954).

ture to bring substantial additions to the body of evidence; we cannot therefore form hypotheses and see them verified or falsified by later finds, in the way that archaeologists often can. Our interpretations must therefore be based on a body of data that may be too small for a convincing, let alone "conclusive," statement, in terms of probabilities, to be made about them.

I shall nevertheless venture on a statistical observation about the battle scenes, which arises from a remark made in a review of Ahlberg's Fighting on Land and Sea in Greek Geometric Art a decade ago by Nicolas Coldstream.[18] It concerns a particular bone of contention in the controversy about the meaning of the Geometric scenes: the "Dipylon shield" carried by so many of the warrior figures in them. I am not going to reopen the old controversy as to whether or not these shields can be taken as a sign that the artist is giving his picture a heroic setting. Instead, I wish to use as a statistical unit the individual figure, rather than as hitherto the complete scene. We have some twenty-three figures of warriors holding these shields, or else of isolated shields without a user, shown in actual combat scenes, as opposed to pictures of people marching, parading, or standing by.[19] Of these twenty-three, some seven are either insufficiently well preserved for it to be clear what will be the outcome, or are shown at a point where the fighting has not yet reached a decisive stage. This leaves a residue of sixteen where the warrior is in the thick of battle; and of these, every single one looks like losing. Four are dead or at the point of death (as in Figure 40, top right); two others are already pierced by weapons; four are being disarmed, apparently after capture, and so probably is a fifth, on another vase, who has dropped his shield and is leaning over backwards; two must be listed as "missing, presumed killed," since their shields are shown

[18] Gnomon 46 (1974): 395.

[19] All these scenes are conveniently illustrated in Ahlberg's Fighting on Land and Sea (cited above, n. 16); for one or two details that are difficult to make out, I rely on her descriptive comments.

Figure 41.

Attic Geometric oenochoë (Copenhagen), with scene of land and sea battle.

being carried off on the deck of a departing warship, presumably as booty; while the remaining three (two of them shown in Figure 41) are still embattled, in circumstances where it appears that their comrades are dead or wounded, and there is little evidence of damage to their enemies.

Now sixteen is not a large sample; the portrayals of these shields and their users in battle are greatly outnumbered by the pictures of them being carried in neutral contexts, by files of men on foot (Figure 40, lower zone) or in chariot processions. Yet the record remains a curiously one-sided one, with thirteen definite

and three probable defeats out of sixteen. It seems to me likely that the painters of the dozen battle scenes from which these figures are taken were trying to characterize the users of these shields in some way, at least when it came to combat, and that their meaning was intelligible at least in the small circle of their known customers. The likelihood of mere coincidence is further reduced by another feature pointed out by Coldstream in his review: in no single surviving Geometric battle scene is the same type of shield carried by members of opposing sides. What I am suggesting is not that the context of these scenes need necessarily therefore be heroic; but that they are likely to have a narrative content of some kind.

Let us turn back now to the question of the treatment of time, which we saw to be bound up with the understanding of later Greek vase-paintings and works of art of other kinds. I have tried to show elsewhere that Geometric scenes, of varying subject matter, exhibit rudimentary instances of the "synoptic" method, in which we can say that more than one moment of time (or on the other account, more than one "epithet") appears in the same picture.[20] Even the commonest of subjects, the prothesis , shows this in a number of cases. Twice, the actual lying in state appears in the same zone as a complete procession of chariots; more often, a few representative chariots (as in Figures 39 and 42) appear immediately alongside the prothesis , rather than the full procession.[21] In any sensible funerary ritual, these two events would take place successively, not simultaneously, so that the participants could witness both; furthermore they must have been spatially separated, with the procession in a large open space and the lying in state either indoors or in the courtyard of the deceased's house.

[20] A. M. Snodgrass, Narration and Allusion in Archaic Greek Art (cited above, n. 5), 16–21.

[21] See Prothesis and Ekphora (cited above, n. 16), 185, on nos. 20 and 33, noting also 160–70 on "the lateral extensions of the prothesis zone."

Figure 42.

Fragment of Attic Geometric krater (Athens), with scene of prothesis.

Parallel arguments could be applied to the case of an actual procession where the chariot passengers face alternately forwards and backwards,[22] which is best explained as showing different moments in the course of a ritual that required them to turn around as the chariot raced along; to pictures of dancers, some of whom have their hands raised and some lowered, which are susceptible of a parallel explanation; and to a few of the small, but interesting, group of Geometric scenes that have been thought to show specific legends, known to us from epic or other literary sources—including both the examples to be discussed presently (Figures 45 and 48). Nor is this "proto-synoptic" idea the only link between Geometric and later artists' approaches to their themes. A group of later paintings with genre subjects treats the theme of the dance in a quite different way, by choosing the fleeting moment of time in which a dancer is in the act of leaping into the air, with legs doubled underneath him (Figure 43). It is remarkable to find that there is more than one example of this motif in Geometric vase-painting, showing a preoccupation with

[22] Amphora, Hamburg 1966.89: see Prothesis and Ekphora (cited above, n. 16), 28, 189–90, no. 43, pl. 60a.

Figure 43.

Corinthian aryballos (Corinth Museum), with scene of dancers.

catching the single instant of time, almost in the manner of a snapshot (Figure 44).[23]

There is little doubt that further search would add considerably to this list of features that link the Geometric figure-scenes with those of the later phases of Greek art. But let us pause here to consider what has emerged so far. The Geometric vase-painter, almost from the time that he begins to show grouped figures, exhibits signs of what was later to become a consuming interest, that of embodying some kind of story in his compositions—whatever the precise content of those stories. He also makes use—indeed, it is only because of this that we can detect a narrative element in some of his pictures—of a technique that enables him to encapsulate more than one element of a narrative sequence in the same picture: the technique that I have been call-

[23] For example, the kantharoi Athens NM 14447 and Copenhagen 727: see R. Tölle, Frühgriechische Reigentänze (Waldsassen, 1964), 12–14, nos. 4 (pl. 3) and 6.

Figure 44.

Attic Geometric kantharos (Copenhagen), with scene of musicians and dancers.

ing "synoptic." Thus, whether or not we may infer from the use of this technique a conscious concern with the time-dimension, this conclusion seems to follow: whatever motive lay behind the use of the technique in Archaic and later times, that motive was already operative in the later part of the eighth century B.C., when the Geometric figure-scenes appeared.

I make these observations mainly in order to combat the tendency, long maintained among historians of classical art, to draw a firm line between Geometric and later art. This demarcation underlies many treatments of artistic questions, including the one from which we began, that of the narrative emphasis in Greek art. Specialists in this field have espoused the view that the Geometric painter, lacking the technical means of making explicit his narrative intentions, must therefore have lacked such intentions in the first place. It must be conceded that for us today (and therefore, we are apt to infer, for contemporaries too), it is only with

great difficulty that any distinctive story can be extracted from these impersonal compositions. But I am not sure that this has any firm implications for the painters' thought-processes. I do not think that we should easily reject the view, put forward in Richard Kannicht's recent paper, that "for the contemporary (as well as for the modern) viewer they were (as they are) open to more than one interpretation."[24] It is interesting that recent work of a Structuralist bent has begun to make some rather similar claims for vase-scenes of a later date,[25] and there is an attraction about any initiative that opens up the possibility of analogy between different periods of Greek art.

A good and specific example of this distinction habitually drawn between Gemometric and later art—even art of the immediately ensuing generation—is given by the case of the strange "double figures" shown on a surprising number of Geometric vases (Figure 45). It is a widely held view, first advanced by John Cook in 1935 and strongly maintained by more recent writers, that the double figure is an artistic convention for showing two men (most often, two warriors) standing side by side.[26] This view fits well with the fact that, among other things, it appears four times on a single vessel, a krater in New York. But most adherents of this view have also seen that in the immediate post-Geometric period, the first decades of the seventh century B.C., the same convention (or something very like it) had already come

[24] R. Kannicht, "Poetry and Art: Homer and the Monuments Afresh," Classical Antiquity 1 (1982): 85, a view anticipated by H.-P. Isler, "Zur Hermeneutik früher griechischer Bilder," in Zur griechische Kunst: Hansjoerg Bloesch zum 60. Geburtstag (Ant. K. , suppl. 9, Bern, 1973), 34–41.

[25] As for instance those by C. Bérard, "Iconographie—Iconologie—Iconologique," Etudes de Lettres (1983), pt. 4, 5–37, for fountain-house scenes on hydriai (22) and for tyrannicide pictures on funerary vases (30–31); echoed by V. Dasen's paper (cited above, n. 9) in the same issue, at 68; note, too, R. Osborne, "The Myth of Propaganda and the Propaganda of Myth," Hephaistos 5–6 (1983–84):61–70.

[26] J.M. Cook, "Protoattic pottery," BSA 35 (1934–35):206: "nothing more than the creation of artists faced with the difficulty of filling a space too broad for a single figure and too narrow for two." Cf. Boardman, "Symbol and Story" (cited above, n. 15), 25–26.

Figure 45.

Projected drawing, by Piet de Jong, of scene from Attic Geometric oenochoë

(Athens, Agora Museum).

to mean something quite different: it was now used to portray the pair of Siamese twins who occur in Greek legend, the sons of Aktor, who beat Nestor in a chariot race on one occasion, fought inconclusively against him on another, and were finally killed by Herakles. Now whatever our verdict on this theory, it clearly posits a certain perceptual gap or discontinuity between the Geometric artists and their immediate successors: a gap that would be quite intelligible—and would indeed find many parallels—if the two groups had belonged to different cultures, or even possessed different bodies of legend. But neither circumstance applies to this period of early Greek history.

I have been stressing, in contrast, certain elements of continuity between Geometric and later vase-painters. It would be unwarranted to use this evidence as a basis for the wider claim that there was also continuity in subject matter between the two periods: that, for example, the later preoccupation with portraying specific legends was already present in Geometric times. It is surely a sounder approach to examine the Geometric evidence first in its own framework, remembering that it reflected the concerns of a particular society—in some cases, as we have seen, a decidedly restricted society, but more generally the Greek communities of the later eighth century, about which we know a certain amount from other sources. One such source (a fundamental one) is our knowledge of the contemporary Greek language itself. I wish to digress here, to consider an important question that

must arise in any discussion of attitudes to the heroic past: namely the meanings of the word heros itself.

In his edition of Hesiod's Works and Days in 1978, Martin West spelled out some of the implications of the curious fact, noted by Erwin Rohde more than eighty years earlier, that the word heros appears in Greek in two distinct, and in some ways incompatible, meanings.[27] In epic, it is freely applied to living men who are, before all else, warriors, but who when they eventually die or are killed, will pass irrevocably into a dim underworld. This use, which occurs seventy-four times in the Iliad alone, is also found in surviving passages of Hesiod as well as in the Odyssey —where, however, it is more indiscriminately applied (to a bard and a servant, for instance), in a way that might suggest that this sense for heros had now begun to pass out of the living language. By contrast, heros in later literature means someone who has died—not necessarily long ago, but sometimes very recently—but who in another sense has been immortalized, and is honored by some kind of cult. The first sense is thus purely secular, the second essentially religious. The two senses are not, however, sequential in time, as the literary record might suggest: if anything, there are signs that the second use of hero , though not attested in writing until the later accounts of the Code of Draco (c. 620 B.C.), may be the older and the more primitive. Rather, they represent two different facets of a system, developed separately during the Greek Early Iron Age; West tentatively hints at a geographical distinction between the two in the earlier stages, with the secular warrior-hero being characteristic of the Ionian epic, and the hero of cult being at home in the Greek mainland. The archaeological evidence certainly supports the second element of this view, with the practice of cult-offerings at the

[27] See M.L. West, Hesiod: The Works and Days (Oxford, 1978), 186 on line 141; 190–91 on lines 159–60; and in excursus 1, 370–73. E. Rohde's discussion is to be found in his Psyche: Seelencult und Unsterblichkeitsglaube der Griechen (2nd ed., Freiburg i.B., Leipzig, and Tübingen, 1898), 152–99.

graves of the ancient or recent dead beginning very early on the mainland. In 1979 this same distinction in the use of the word hero was dealt with independently, and more elaborately, in an important book by Gregory Nagy.[28] He emphasized a further aspect of the contrast: the hero of Ionian epic is typically a figure of pan-Hellenic importance, whereas the status of the recipient of a hero-cult, like the cult itself, is usually a local one. The first is indeed "immortalized" in one sense, by having his deeds perpetuated in song, but the second becomes "immortal" in a more practical way, receiving honors almost as if he were a god. Nagy, like West, sees the two systems as having eventually come into some degree of competition; the result was a form of multiple fusion, with Homeric heroes, for example, also becoming recipients of a hero-cult.

Is this matter relevant to the interpretation of the Geometric vase-paintings of the Greek mainland? There has been a strong tradition here of pursuing parallels between the painter and the epic poet, not just at the level of their general mentalities, but in terms of their interest in identical narrative subjects. I count this, however, among those approaches referred to earlier, which must be judged to have failed. I was glad to read in John Boardman's recent paper the bald proposition "that no Attic Geometric artist had ever read or heard recited a single line of Homer."[29] On a parallel issue, that of the Geometric hero-cults at anonymous Bronze Age graves, I have argued likewise that the absolute contradiction between the funerary practices described by Homer and those of the actual mainland tombs where cults were established hardly suggests that the latter activity was inspired by hearing epic recitations.[30] On reflection, I now feel that this

[28] G. Nagy, The Best of the Achaeans (Baltimore, 1979), pt. 2, 69–210, especially 114–17, 159–61.

[29] Boardman, "Symbol and Story" (cited above, n. 15), 29.

[30] See A.M. Snodgrass, "Les Origines du culte des héros dans la Grèce antique," in La Mort, les morts dans les sociétés anciennes , ed. G. Gnoli and J.-P. Vernant (Cambridge, 1982), 107–19, especially 115–16. There has perhaps been an excess of recent writing on this theme, as is shown by the fact that some of the same points are made in an earlier paper of mine, "Poet and Painter in Eighth-century Greece," PCPS 205 (1979):118–30; by Kannicht, "Poetry and Art," in 1982 (cited above, n. 25); and again by C. Brillante, "Episodi iliadici nell'arte figurata e conoscenza dell'Iliade nella Grecia antica," Rh. Mus. 126 (1983): 97–125—three articles none of which displays awareness of the others.

view could have been put more strongly: the contrast between the cremation, covered by a tumulus, that Homer describes and the multiple inhumations in rock-cut chamber-tombs where most of the cults were instituted is so complete that it positively excludes familiarity with Homer—or, at least, identification of the object of the cult with a "Homeric hero."

Now, too, it becomes possible to fit a new piece of evidence into its place. Greek hero-cult, as already remarked, could include not only the worship of the remote and anonymous Bronze Age dead but also the heroization of the recently deceased. The discovery in 1981 of a pair of exceptionally rich burials of the tenth century B.C. at Lefkandi, over which a large building (Figure 54, p. 183), apparently a heroön (center of hero-cult), had been almost at once constructed,[31] posed insuperable problems for those who believed in the influence of Ionian epic on such practices: for who could believe that the great burial scenes in Homer, or even their earlier prototypes, were known to the people of the island of Euboea as early as about 950 B.C.? We can now see this phenomenon for what it probably is: an unusually early manifestation of a strand of hero worship that we know well from classical times—the elevation of prominent persons to the ranks of the heroes immediately after their death. Rohde, who called the hero-cults of classical Greece "a still burning spark of ancient belief kindled to a new flame," spoke truer than he knew: the spark had been alight since at least the tenth century B.C. (Psyche , W.B. Hillis, trans.).

[31] See M.R. Popham, E. Touloupa, and L.H. Sackett, "The Hero of Lefkandi," Antiquity 56 (1982): 169–74.

Figure 46.

Distribution map of hero-cults in early Greece.

We can now begin to draw the strands of this argument together. The worship of the anonymous but heroic dead (Figure 46), that essentially local phenomenon, was part of the world view of several eighth-century communities in mainland Greece: notably in the Peloponnese (the Corinthia, the Argolid [Figure 47], and later Messenia); but also perhaps in Boeotia (on the evidence of a passage of Hesiod to be considered in a moment); and quite definitely in Attica (the most relevant locality from the point of view of the Geometric vase-paintings). The evidence here includes one of the richest of these cults, at the Mycenaean tholos-tomb of Menidhi (ancient Acharnai), where as Peter Kahane shrewdly pointed out, the dedications actually included Geometric vases decorated with racing chariots in a funerary

Figure 47.

Plan of a Mycenaean chamber-tomb (Prosymna Tomb xix)

with traces of later cult (after C. W. Blegen).

context.[32] The very foundation of the Olympic Games, traditionally in 776 B.C., may be linked with such practices. Euboea, as we have seen, provides our earliest evidence for the heroization of the newly deceased, and the occurrence at Lefkandi is supported by a later instance from nearby Eretria.[33] Quite possibly,

[32] P. P. Kahane, "Ikonologische Untersuchungen zur griechisch-geometrischen Kunst," Ant. K. 16 (1973): 134 n. 89.

[33] See C. Bérard, "Récupérer la mort du prince," in La Mort, les morts (cited above, n. 30), 89–105.

the subjects of these early cults were, at the time, referred to by some word other than hero : just as, in the converse case, Homer seems to prefer the word hemitheos ("demigod") for those few personages in his poems who appear to receive worship after their deaths. It seems to have been in the years round 700 B.C., with the fusion of the two facets of heroism, that the local grave-cults were joined by the worship of the named heroes of epic, ranging from the famous Agamemnon and Menelaos to the more obscure Phrontis, who had been Menelaos's steersman and was probably commemorated at Cape Sunion, where he had died. It may be significant, too, that these "Homeric" cults seem never to be located at genuine graves of the heroic age.

We return now to a point made much earlier, about the social and chronological exclusiveness of the vases with battle scenes from Athenian burials. It has emerged that the background of the people who made and used these vases is unlikely to have been touched by Ionian epic. It may indeed be doubted whether their vision was shaped by literary works of any kind, but that is not central to the argument here. Whether we are dealing with lost poetry, or with a purely vernacular oral tradition, the content of the stories familiar to these people is likely, from our point of view and indeed from that of post-Homeric Greece, to have been of considerable obscurity. The legends will have included a substantial body of primarily local traditions, of the kind that often surfaces in later classical literature, sometimes to the embarrassment of the writers who retail it, because of its predictable inconsistency with the (by then) more widely accepted versions. It is no wonder, then, that the attempt to match the pictures on their vases with the episodes known from epic has been a failure: no wonder, but also no reflection on the likelihood of legendary subjects having been portrayed.

We have, in the course of this argument, reached two apparently conflicting conclusions: on the one hand the Geometric artists, in terms of their techniques and aims, show signs of having begun to explore the same problems that preoccupied their suc-

cessors; but on the other, they cannot be thought to have yet encountered the inspiration from epic that was to make a progressively greater impact on those successors in their choice of subject matter. The question of the subjects of the Geometric vase-scenes is thus left in a state of suspense from which it may never be possible to release it. A possible view would be to see these paintings as a fleeting apparition in the history of ancient art; as the product of a brief overlap in time between the mainland Greek vision, not yet overlaid by the influence of epic, and the existence of a new conceptual apparatus that enabled a story to be told in visual form. If so, one could reasonably speculate that current beliefs included such elements as we know to have composed the traditional cult of the hero: the retailing of locally important legend and its linkage with the honors paid to the remote and anonymous dead. This is the spirit embodied by the passage in Hesiod's Works and Days (lines 141–43), in which he speaks of the tribute paid after their death, not to the heroes, but to the Silver Men of a yet earlier age: hidden under the earth, they have become "spirits of the underworld," and they are remembered with honor. But the tradition also extended to the more recent dead, and some fusion may have taken place between these and their more distant predecessors, in that "highly evolved transformation of the worship of ancestors" that Nagy (following Rohde) sees in the Greek cult of heroes.[34]

If any of this belief infiltrated the decoration of the Geometric vases, it would of course make for a much more ambiguous interpretation of them than those sought by modern scholarship. It is unlikely that we shall ever be able to assess the relative prominence, in the mind of artist and client, of the several elements in this "evolved ancestor worship" Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility that such an interpretation might apply, not only to the relatively frequent and apparently anonymous crowd

[34] Nagy, Best of the Achaeans (cited above, n. 28), 115.

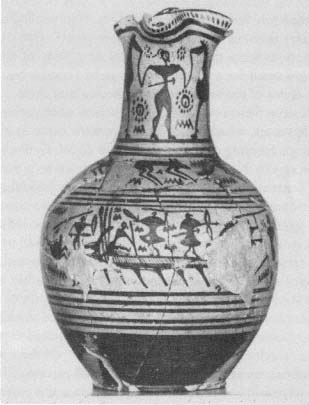

Figure 48.

Attic Geometric bowl (London, British Museum), with scene of departing warship.

scenes on which we have been concentrating, but also to the handful of more distinctive pictures in which elements of a unique narrative content have been seen. Because of the obvious attraction of identifying their subjects with episodes known from epic, these few pictures have become the fiercest battleground between the upholders of the "heroic" interpretation and their more skeptical opponents.

A notable case in point has been the scene on a bowl in London showing a departing warship; it perhaps belongs to the 730s B.C. (Figure 48). Klaus Fittschen, for example, devoted several pages to arguing that it could not be interpreted as a portrayal of the elopement of Helen with Paris, of the abduction of Ariadne by Theseus, or of the flight of Jason with Medea, all of which identifications had been earlier suggested.[35] But what if we look

[35] K. Fittschen, Untersuchungen zum Beginn der Sagendarstellungen bei den Griechen (Berlin, 1969), 51–60.

Figure 49.

Impression of a gold signet ring (Oxford, Ashmolean Museum), said to be from the harbor town of Knossos.

at it in the different, if hazier, light of a society known to have been concerned with hero and ancestor worship? We might then wish to compare its iconography with that of a surviving Bronze Age scene to which it bears a certain resemblance: the one on a Minoan gold ring from the harbor town of Knossos (Figure 49).[36] The subject of the gold ring is detectably different: the man and woman at the left do not seem to be about to embark on the galley in this case, whereas the man at least is definitely going to do so in the Geometric scene; and a female figure, doubtless a goddess, appears to float in the air above the Minoan ship. But some iconographic connection, however indirect, would go some way towards explaining a puzzling feature of the Geometric painting, the large scale of the figures at the left; and the very existence of such a connection would be suggestive for the interpretation of the later work.

At this point, the skeptics may appeal to the verdict of the late V.E.G. Kenna (see n. 38 below) that the ring is, or may be, a modern forgery. His opinion was based partly on the suspiciously excellent preservation of the work, partly on the icono-

[36] Oxford, Ashmolean Museum no. 1938.1129.

Figure 50.

Impression of a gold signet ring (Athens, National Museum), from the Tiryns Treasure.

graphic resemblance to other ancient works (perhaps including our Geometric bowl) that could have been known to a forger in 1927, the year in which Sir Arthur Evans first came to hear of the ring's existence. But the scene on the ring does have some affinity, in content but not in style (as, less directly, does the Geometric vase-painting) with another gold ring of Bronze Age date, which cannot be suspected of being a forgery, since it was dug up as part of a hoard at Tiryns in 1915 (Figure 50).[37] Furthermore, the genuineness of the Knossos harbor town ring had been accepted by a long line of experts before Kenna, including not merely Evans (who had the vested interest of having later bought it), but also Martin Nilsson in 1928, Axel Persson in 1942, Hagen Biesantz in 1954 (by implication, since he excluded it from his list of gemmae dubitandae ), and Stylianos Alexiou, who proposed a new interpretation of it in 1958. Fittschen, writing in 1969, did not use this pretext for disregarding the ring, as well as the one from Tiryns, but merely remarked (quite correctly) that since their own interpretation was obscure, they could not be used to aid

[37] See G. Karo, "Schatz von Tiryns," AM 55 (1930): 124–26, pls. 2.2 and 3.1 and Beilage 30.1: no. 6209.

the interpretation of the Geometric scene.[38] My point can be summed up by saying that a connection of any kind between the Geometric painting and the Minoan ring—provided that the latter is genuine—will be enough to throw grave doubt on what has become the standard skeptical reading of the Geometric scene: that it portrays a blameless eighth-century Athenian sea-captain saying good-bye to his wife.

But there I should like to leave the matter. The general aim of this chapter has not been to interpret: indeed, it could be seen as that of showing that interpretation is premature, and that our failure to achieve any consensus to date is itself a sign of this prematureness. We have first to establish something more fundamental: the general area in which we might conduct our search in the future for possible interpretations of the baffling figure-scenes of Greek Geometric art.

[38] On the Knossos harbor town ring, see Persson, Religion of Greece (cited above, n. 7), 81–82, ring no. 26; and also S. Alexiou, "O daktulios tes Oxfordis," in Minoica: Festschrift zum 80. Geburtstag von Johannes Sundwall, ed. E. Grumach (Berlin, 1958), 1–5, who cites the earlier verdicts on the ring's genuineness and detects a parallel resemblance to another work of post-Minoan date, the open-work bronze stand from the Idaean Cave. For later views, see V.E.G. Kenna, Cretan Seals (Oxford, 1960), 154, under both "3(b)" and "7(a)"; Fittschen, Untersuchungen (cited above, n. 35), 58 and n. 307. I am most indebted to J.G. Younger, who is to include the ring in a forthcoming publication and has drawn my attention to features (the form of the ring itself, the decoration on the ship's hull) that would not have been likely to occur to a forger in or before 1927.