PART ONE

THE POETS OF NEPAL

Nepali Poetry

Poetry is the richest genre of twentieth-century Nepali literature. Although the short story has developed strongly, the drama holds its ground in the face of fierce competition from the cinema, and the novel is increasingly popular, almost every Nepali writer composes poetry. Since the appearance of Sharada , Nepali poetry has become diverse and sophisticated. The poets I have selected for inclusion represent different stages and strands of this development, and I have attempted to present them in an order that reflects the chronology of literary change. The direction that this process of evolution has taken should be clear from the introduction to individual poets and the translations of their poems. Here, a few general comments are offered by way of introduction.

Lekhnath Paudyal, Balkrishna Sama, and Lakshmiprasad Devkota were undoubtedly the founders of twentieth-century Nepali poetry, and each was a distinctly different poet. Lekhnath was the supreme exponent of meter, alliteration, and melody and the first to perfect the art of formal composition in Nepali. His impact on poets contemporary with him was powerful, eventually producing a kind of "school." Although his influence has waned, this school retains some notable members.[1] Sama was primarily a dramatist, but his poems were also important. He began as a disciple of Lekhnath but later rebelled against the restraints of conventional forms with the same vigor that he brought to his opposition to Rana autocracy. Sama's compositions are colored by sensitivity, intellectualism, and clarity, and because of his role as a social reformer and the accessibility of his work, he is still highly respected. Both Lekhnath

[1] These include Madhav Prasad Ghimire (b. 1919), whose long lyric poem on the loss of his wife, Gauri (1947), remains extremely popular.

and Sama were deliberate, methodical craftsmen and masters of particular modes of poetic composition, but the erratic genius of Lakshmiprasad Devkota brought an entirely new tone and spirit to Nepali poetry. Early in his career, he took the revolutionary step of using folk meters in the long narrative poems that are now among the most popular works of Nepali literature. Later, he produced the greatest epics of his language and finally, adopting free-verse forms, he composed some of its most eloquent poems. It would be difficult to overstate Devkota's importance in the modern literature of Nepal: his appearance on the scene has been compared to that of a meteor in the sky or as Nepali poetry reaching full maturity "with a kind of explosion" (Rubin 1980, 4).

The Sharada era produced poets who were influenced by their three great contemporaries, but also made their own distinctive contributions to the development of the genre. In his early years, Siddhicharan was obviously a disciple of Devkota, but his poems are calmer, clearer, and less rhapsodic. Vyathit also had much in common with Lekhnath, but he differed in his obvious social concern and his gift for composing short epigrammatic poems. Rimal was motivated principally by his political views, but he also did much to establish free verse and the prose poem in Nepali. His influence is more apparent in the work of young poets today than is that of most of his contemporaries. The Sharada poets were men who were in their prime during the 1940s and 1950s, although both Siddhicharan and Vyathit remain active today. The revolution of 1950-1951 certainly brought an atmosphere of greater freedom to Nepal, and a large number of works were published that had been withheld for fear of censorship. Few immediate changes took place in the Nepali literary scene, however, and the prerevolutionary poets continued to occupy a preeminent position until the following decade.

During the 1960s, Nepali poetry departed quite radically from the norms of the preceding twenty-five years, which was a result of the unprecedented changes that occurred in Nepali society in general and in intellectual circles in particular. After 1960, a new literary journal, Ruprekha (Outline) quickly became Nepal's major organ for aspiring new writers. Among these was Mohan Koirala, arguably the most significant poet to have emerged in Nepal since Devkota. The philosophical outlook of the generation of poets who emerged after 1960 differed from that of its predecessors in many respects. The immense expansion of education spread literacy throughout Nepal and produced a generation of graduates who were familiar with philosophies and literatures other than their own. The initial effects of this intellectual opening out in Nepal could be seen clearly in the poetry of the Third Dimension movement and particularly in the work of Bairagi Kainla and ÌIshwar Ballabh. The new poetry of the 1960s was full of obscure mythological references and

apparently meaningless imagery; this "cult of obscurantism" also influenced later poets, such as Banira Giri. It was coupled with a sense of pessimism and social alienation engendered by lack of opportunity in Nepal, which is expressed poignantly by the novelist and poet Parijat and angrily by Haribhakta Katuval.

The emergence of Bhupi Sherchan brought about further changes in the language and tone of Nepali poetry as well as in its purpose. His satire, humor, and anger were expressed in rhythmic free-verse forms, and the simplicity of his diction signified an urge to speak to a mass readership, not just to the members of the intellectual elite. During the 1960s, Nepali poetry seemed divorced from the realities of the society that produced it, but in the decade that followed it again addressed social and political issues in a language stripped of earlier pretensions. Poetry reassumed the role it had played during the Sharada era, once again becoming a medium for the expression of social criticism and political dissent. This trend reached a kind of climax in the "street poetry revolution" of 1979-1980, and Nepali writers played an important role in the political upheavals of February-April 1990 (Hutt 1990). This would surely have been a source of satisfaction to the mahakavi (great poet) Lakshmiprasad Devkota, who once wrote:

Our social and political contexts demand a revision in spirit and in style. We must speak to our times. The politicians and demagogues do it the wrong way, through mechanical loudspeakers. Ours should be the still, small voice of the quick, knowing heart. We are too poor to educate the nation to high standards all at one jump. Nor is it possible to kill the time factor. But there is a greater thing we can do and must do for the present day and the living generation. We can make the masses read us if we read their innermost visions first. (1981, 3)

Almost every educated Nepali turns his or her hand to the composition of poetry at some stage of life. In previous centuries, poetic composition was considered a scholarly and quasi-religious exercise that was closely linked to scriptural learning. It therefore remained the almost exclusive preserve of the Brahman male. Today, however, Nepali poets come from a variety of ethnic groups. Among those whose poems are translated here, there are not only Brahmans but also Newars, a Limbu, a Thakali, and a Tamang, and although it is still rather more usual for a poet to be male, the number of highly regarded women poets is growing steadily. Even members of Nepal's royal family have published poetry: the late king Mahendra (M. B. B. Shah) wrote some very popular romantic poems, and the present queen, writing as Chandani Shah, has recently published a collection of songs.

The Nepali literary world is centered in two Himalayan towns: Kath-

mandu, the capital of Nepal, and Darjeeling, in the Himalayan foothills of the Indian state of West Bengal. Other cities, notably Banaras, served as publishing centers during the period of Rana rule in Nepal, but their importance has diminished in recent years. Until the fall of the Ranas, some of the most innovative Nepali writers were active in Darjeeling (the novelist Lainsingh Bangdel and the poet Agam Singh Giri are especially worthy of note), and fundamental work was also done by people such as Paras Mani Pradhan to reform and standardize the literary language. In more recent years, Darjeeling Nepalis have been concerned with establishing their identity as a distinct ethnic and linguistic group within India and with distancing themselves from Nepal. Thus, the links between the two towns have weakened to the extent that writers are sometimes described as a "Darjeeling poet" or a "Kathmandu poet" as if the two categories were in some way exclusive. This difference is also underscored by minor differences in dialect between the two centers.

It has always been well-nigh impossible for a Nepali writer to earn a livelihood from literary work alone. All poets therefore support themselves with income from other sources. Lekhnath was a family priest and teacher of Sanskrit; Devkota supported his family with private tutorial work and occasionally held posts in government institutions. Nowadays, poets may be college lecturers (Banira Giri), or they may be employed in biscuit factories (Bishwabimohan Shreshtha). Many are also involved in the production of literary journals or in the activities of governmental and voluntary literary organizations. Devkota, for instance, edited the influential journal Indreni (Rainbow) and was also employed by the Nepali Bhashanuvad Parishad (Nepali Translation Council) from 1943 to 1946. Sama became vice-chancellor of the Royal Nepal Academy, as did Vyathit. Both Rimal and Siddhicharan were for some time editors of Sharada , and nowadays many younger poets are active in associations such as the Sahityik Patrakar Sangha (Literary Writers' Association) or the Sirjanshil Sahityik Samaj (Creative Literature Society), which organize readings, publish journals, and attempt to claim a wider audience for Nepali literature.

There are various ways in which Nepal rewards its most accomplished poets. Rajakiya Pragya Pratishthan (the Royal Nepal Academy), Nepal's foremost institution for the promotion of the kingdom's arts and culture, was founded in 1957 and now grants salaried memberships to leading writers and scholars for periods of five years. Academy members are thereby enabled to devote themselves to creative and scholarly work without the need for a subsidiary income. The period during which Kedar Man Vyathit was in charge of the academy is remembered as a golden age for Nepali poetry, but in general the scale of the academy's activities

is limited by budgetary constraints. Nevertheless, the academy is a major poetry publisher and has produced many of the anthologies and collections upon which I have drawn for the purpose of this book. The academy also produces a monthly poetry journal, Kavita (Poetry), edited until his recent demise by Bhupi Sherchan, and awards annual prizes to prominent writers; these include the Tribhuvan Puraskar, a sum of money equivalent to two or three years of a professional salary.

Another important institution is the Madan Puraskar Guthi (Madan Prize Guild), founded in 1955 and based in the city of Patan (Lalitpur). The Guthi maintains the single largest library of Nepali books, produces the scholarly literary journal Nepali , and awards two annual prizes (Madan Puraskar) to the year's best literary book and nonliterary book in Nepali.

Sajha Prakashan (Sajha Publishers) is the largest commercial publisher of Nepali books, with a list of nearly six hundred titles. It assumed the publishing role of the Nepali Bhasha Prakashini Samiti (Nepali Language Publications Committee) in 1964 and established an annual literary prize, the Sajha Puraskar, in 1967. Since 1982 Sajha Prakashan has also produced another important literary journal, Garima (Dignity). The Gorkhapatra Sansthan (Gorkhapatra Corporation) produces the daily newspaper Gorkhapatra and the literary monthly Madhupark (Libation). The latter publication has become the kingdom's most sophisticated periodical under the editorship of Krishnabhakta Shreshtha, who is himself a poet of some renown. With Garima, Bagar (The Shore, an independently produced poetry journal), and the academy's Kavita (Poetry), Madhupark is now among the leading journals for the promotion of modern Nepali poetry. The monthly appearance of each of these journals is eagerly awaited by the literary community of Kathmandu, many of whose members congregate each evening around the old pipal tree on New Road. Madhupark in particular has a wide circulation outside the capital. In India, too, institutions such as Darjeeling's Nepali Sahitya Sammelan (Nepali Literature Association) and the West Bengal government's Nepali Academy produce noted journals and award annual literary prizes.

Despite the limited nature of official support for publishing and literary ventures in Nepal, the literary scene is vibrant. The days when Nepali poets had to undertake long periods of exile to escape censorship, fines, and imprisonment have passed, but until April 1990 the strictures of various laws regarding public security, national unity, party political activity, and defamation of the royal family still made writers cautious. With increasing frequency during the 1980s, writers were detained, newspapers and journals were banned, and editors were fined.

But poetry remained the most vital and innovative genre and the medium through which sentiments and opinions on contemporary social and political issues were most frequently expressed. In Nepal, poets gather regularly for kavi-sammelan (reading sessions), and the status of "published poet" is eagerly sought. Most collections and anthologies produced by the major publishers have first editions of 1,000 copies—a fairly substantial quantity by most standards. Literary communities exist in both Kathmandu and Darjeeling, with the inevitable loyalties, factions, and critics. Books and articles on Nepali poetry abound, and critics such as Taranath Sharma (formerly known as Tanasarma), Ishwar Baral, and Abhi Subedi are highly respected.

Features of Nepali Poetry

The last eighty years have seen a gradual drift away from traditional forms in Nepali verse, although a few poets do still employ classical meters. Until the late nineteenth century, however, almost all Nepali poetry fulfilled the requirements of Sanskrit prosody and was usually composed to capture and convey one of the nine rasa. Rasa literally means "juice," but in the context of the arts it has the sense of "aesthetic quality" or "mood." The concept of rasa tended to dictate and limit the number of themes and topics deemed appropriate for poetry.

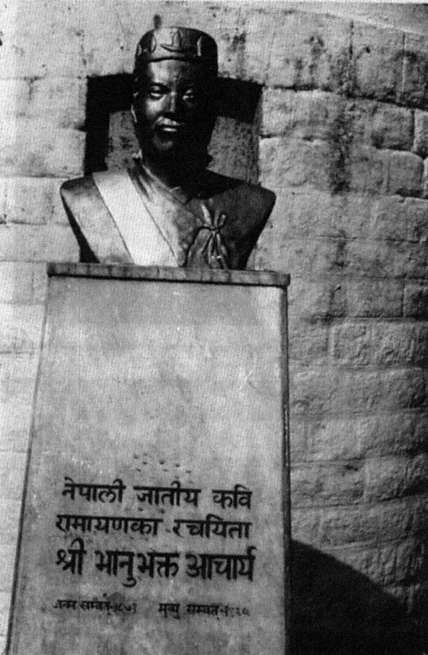

Classical Sanskrit meters, many of which are derived from ancient Vedic forms, are based on quantity and are extremely strict. A syllable with a long vowel is considered long, or "heavy," whereas a syllable is short, or "light," when it contains only a short vowel. Whether a syllable is followed by a single consonant or a conjunct consonant also affects its metrical length. The simplest classical meter, and consequently one of the most commonly used, is the anushtubh (or anushtup ), often referred to simply as shloka , "stanza." This allows nine of the sixteen syllables of each line to be either long or short and therefore provides an unusual degree of flexibility. In most other meters, however, the quantity of each syllable is rigidly determined. The shardula-vikridita that Bhanubhakta adopted in his Ramayana epic is a typical example. Each line of verse in this meter must contain nineteen syllables with a caesura after the twelfth, and the value of each and every syllable is dictated with no scope for adaptation or compromise.

Evidently, the ability to compose metrical verse that retains a sense of freshness and spontaneity is a skill that can be acquired only through diligent study and has therefore remained the preserve of the more erudite, high-caste sections of society. Most Nepali poets now regard these rules and conventions as restrictive, outdated, and elitist, especially

because they also extend to considerations of theme and structure. Yet it is significant that the skill to compose poetry in a classical mode was considered an important part of a poet's repertoire until quite recently. Balkrishna Sama used Vedic meters even in some of his later poems, and Devkota gave a dazzling display of his virtuosity in the Shakuntala Mahakavya (The Epic of Shakuntala) by employing no less than twenty different meters.

The first attempts to break the stranglehold of classical conventions were made during the 1920s and 1930s when poets such as Devkota began to use meters and rhythms taken from Nepali folk songs. The musical jhyaure became especially popular and retains some currency today. Such developments were part of a more general trend toward the definition of a specifically Nepali identity distinct from pan-Indian cultural and literary traditions. These changes could also be regarded as a literary manifestation of the Nepali nationalism that eventually toppled the Rana autocracy.

In the years that followed, many poets abandoned meter altogether. Nonmetrical Nepali verse is termed gadya-kavita , literally "prose poetry." Most nonmetrical poems can be described as free verse, but a few works do exist, such as Sama's "Sight of the Incarnation" (Avatar-Darshan ), that seem to be conscious efforts to compose genuine prose poems. As Nepali poetry departed from the conventions of its Sanskrit antecedents, its language also changed. The arcane Sanskrit vocabulary required by classical formulas was no longer relevant. When poets began to address contemporary issues and to dispense with traditional forms, they also strove to make their works more readily comprehensible. The vocabulary of the "old" poetry was therefore rapidly discarded.

Nepali poetry is composed in several distinct generic forms. The most common is, of course, the simple "poem" (kavita ) written in metrical or free-verse form. A khanda-kavya , "episodic poem," is longer and is usually published as a book in its own right. It consists of either a description or a narrative divided into chapters of equal length. Devkota's narrative poem Muna-Nadan (Muna and Madan) and Lekhnath's description of the seasons, Ritu-Vichara (Reflections on the Seasons), are two famous examples. Because the khanda-kavya is a form with classical antecedents, it is invariably composed in metrical verse. The lamo kavita , or "long poem," however, is a modern free-verse form that is not divided into chapters and that can address any topic or theme. The longest poetic genre is the mahakavya , the "epic poem," another classical form that must be composed in metrical verse. The importance and popularity of the khanda-kavya and the mahakavya have diminished significantly in the years since 1950.

Some Problems of Translation

All translation involves a loss, whether it be of music and rhythm or subtle nuances of meaning. To translate from one European language into another is no easy task, but when the cultural milieus of the two languages concerned are as different from each other as those of Nepali and English are, the problems can sometimes seem insurmountable. The first priority in translating these poems has been to convey their meaning, tone, and emotional impact. On numerous occasions, I have begun to translate poems that seemed especially important or interesting only to realize that justice simply could not be done to the original and that the task had best be abandoned. Lekhnath's poems in particular, with their dependence on alliteration and meter, are inhospitable territory for the translator: to render them into rhyming couplets would be to trivialize and detract from their seriousness, but a free-verse translation that lacked a distinctive rhythm would be dishonest. For these reasons, Lekhnath is represented here by only a few of his shorter poems: to appreciate fully the elegance of a work such as Reflections on the Seasons , a knowledge of Nepali is essential. In contrast, some of Bhupi Sherchan's compositions lend themselves particularly well to translation, especially to an admirer of Philip Larkin's poems. (See, for example, "A Cruel Blow at Dawn" [Prata: Ek Aghat ].) In every case, I have attempted to produce an English translation that can pass as poetry, without taking too many liberties with the sense of the original poem. I cannot claim perfection for these translations, and it would of course be possible to continue tinkering with them and redrafting them for years to come. Eventually, however, one must decide that few major improvements can be made and that the time has come to publish, although, one hopes, not to await damnation.

The intrinsic difficulty of translating Nepali poetry into English stems partly from some important differences between the two languages. The nature of the Nepali language provides poets with great scope for omitting grammatically dispensable pronouns and suffixes and for devising convoluted syntactic patterns. In some poems, it is impossible for any single line to be translated in isolation: the meaning of each stanza must be rendered prosaically and then reconstituted in a versified form that comes as close as possible to that of the original Nepali. This is partly because Nepali follows the pattern of subject-object-verb and possesses participles and adjectival verb forms for which English has no real equivalents. But the untranslatable character of some Nepali poetry can also be explained in terms of poetic license. Nepali is also capable of extreme brevity: to convey accurately the meaning of a line of only three or four words, a much longer English translation may be necessary.

The translator is often torn between considerations of semantic exactitude and literary elegance. For example, how should one translate the title of Parijat's "Sohorera Jau"? Jau is a simple imperative meaning "go" or "go away," but sohorera is a conjunctive participle that could be translated as "sweeping," "while sweeping," "having swept," or even "sweepingly," none of which lends itself particularly well to a poetic rendering. "Sweep Away" is the closest I have come to a compromise between the exact meaning and the requirements of poetic language. Problems can also arise when poets refer to specific species of animals or plants. This causes no difficulty when such references are to owls or to pine trees, but in many instances one can find no commonly known English name. A botanically correct translation of a verse from Mohan Koirala's "It's a Mineral, the Mind" (Khanij Ho Man ) would read as follows:

I am a Himalayan pencil cedar with countless boughs,

the sayapatri flower which hides a thousand petals,

a pointed branch of the scented Ficus hirta ...

Clearly, such a pedantic rendering would do little justice to the original Nepali poem.

A further problem is caused by the abundance of adjectival synonyms in Nepali, which English cannot reflect. The translator must therefore despair of conveying the textural richness that this abundance of choice imparts to the poetry in its original language. As John Brough points out, Sanskrit has some fifty words for "lotus," but "the English translator has only 'lotus,' and he must make the best of it" (1968, 31). Nepali poets also make innumerable references to characters and events from Hindu, and occasionally Buddhist, mythology and from their own historical past. Nepali folklore and the great Mahabharata epic are inexhaustible sources of stories and parables with which most Nepalis are familiar. A non-Nepali reader will require some explanation of these references if the meaning of the poem is to be comprehended, and brief notes are therefore supplied wherever necessary.

Lekhnath Paudyal (1885-1966)

Lekhnath Paudyal was the founding father of twentieth-century Nepali poetry, but his most important contribution was to the enrichment and refinement of its language rather than to its philosophical breadth. His poems possessed a formal dignity that had been lacking in most earlier works in Nepali; many of them conformed in their outlook with the philosophy of orthodox Vedanta, although others were essentially original in their tone and inspiration. The best of Lekhnath's poems adhered to the old-fashioned conventions of Sanskrit poetics (kavya ) but also hinted at a more spontaneous and emotional spirit. Although often regarded as the first modern Nepali poet, Lekhnath is probably more accurately described as a traditionalist who perfected a classical style of Nepali verse. Note, however, that his poems occasionally made reference to contemporary social and political issues; these were the first glimmerings of the poetic spirit that was to come after him.

Lekhnath was born into a Brahman family in western Nepal in 1885 and received his first lessons from his father. Around the turn of the century, he was sent to the capital to attend a Sanskrit school and thence to the holy city of Banaras, as was customary, to continue his higher education. During his stay in India, his young wife died, and he met with little academic success. Penniless, he embarked on a search for his father's old estate in the Nepalese lowlands, which was ultimately fruitless, and he therefore spent the next few years of his life seeking work in India. In 1909 he returned to Kathmandu, where he entered the employ of Bhim Shamsher, an important member of the ruling Rana family, as priest and tutor. He retained this post for twenty-five years.

As an educated Brahman, Lekhnath was well acquainted with the

classics of Sanskrit literature, from which he drew great inspiration. From an early age, he composed pedantic "riddle-solving" (samasya-purti ) verses, a popular genre adapted from an earlier Sanskrit tradition, and his first published poems appeared in 1904. Two poems published in an Indian Nepali journal, Sundari , in 1906 greatly impressed Ram Mani Acharya Dikshit, the editor of the journal Madhavi , who became the first chair of the Gorkha Bhasha Prakashini Samiti (Gorkha Language Publication Committee) in 1913 and did much to help Lekhnath to establish his reputation as a poet. His first major composition was "Reflections on the Rains" (Varsha Vichara ) and it was first published in Madhavi in 1909. This poem was later expanded and incorporated into Reflections on the Seasons (Ritu Vichara ), completed in 1916 but not published until 1934. More of his early poems also appeared in a collection published in Bombay in 1912.

One of Lekhnath's most popular poems, "A Parrot in a Cage" (Pinjarako Suga ) is usually interpreted as an allegory with a dual meaning: on one level of interpretation, it describes the condition of the soul trapped in the body, a common theme in Hindu devotional verse, but it also bewails the poet's lot as an employee of Bhim Shamsher. Here the parrot, which has to make profound utterances according to its master's whim, is actually the poet himself. This particular poem is extremely famous in Nepal because it is one of the earliest examples of a writer criticizing the Rana families who ruled the country at the time. In terms of literary merit, however, it does not rank especially highly in comparison with Lekhnath's other verse because it suffers from excessive length and frequent repetition. Indeed, some critics regard it as a poem originally written for children.

Lekhnath produced one of his most important contributions to Nepali poetry at quite an early stage of his career: his first khanda-kavya (episodic poem), Reflections on the Seasons , demonstrated a maturity that was without precedent in Nepali poetry. Indeed, it is largely to Lekhnath Paudyal that this genre owes its prestige in Nepali literature. The primary inspiration for this work was probably The Chain of the Seasons (Ritu-Samhara ) by the great fifth-century Sanskrit poet Kalidasa. Each of the six "episodes" of Lekhnath's poem comprises one hundred couplets in the classical anushtup meter and describes one of the six seasons of the Indian year. Most of the metaphors and similes employed in the poem were borrowed directly from Sanskrit conventions for the description of nature (prakriti-varnana ), but a few were unusual for their apparent reference to contemporary political issues:

In the forest depths stands a bare poinsettia

Like India bereft of her strength and wisdom . . .

Soon the flowers seem tired and wan,

sucked dry of all their nectar,

As pale as a backward land

The poem is also often praised for the subtlety of its alliterations and for the dexterity with which Lekhnath constructed internal rhymes:

divya anandako ranga divya-kanti-taranga cha

divya unnatiko dhanga divya sara prasanga cha

Divine the colors of bliss,

divine the ripples of light,

Divine the manner of their progress,

divine the whole occasion

Lekhnath did not develop the great promise of these early episodic poems further until much later in his life, but a large number of his shorter poems continued to appear in a variety of literary journals in both India and Nepal. Many poems were probably never published and may now be lost. A two-volume collection, Delicacy (Lalitya ) was published in 1967-1968 and contained one hundred poems. Lekhnath's shorter works covered a wide variety of topics and conveyed all of the nine rasa . Although many are plainly moralistic, some have a whimsical charm and are often couched in uncharacteristically simple language. One such is "The Chirruping of a Swallow" (Gaunthaliko Chiribiri ), first published in 1935, in which a swallow explains the transient nature of existence to the poet:

You say this house is yours,

I say that it is mine,

To whom in fact does it belong?

Turn your mind to that!

His devotional poems are more formal and are admired for their beauty and for the sincerity of the emotions they express. "Remembering Saraswati" (Saraswati-Smriti ) is the prime illustration of this feature of Lekhnath's poetry. Other compositions, such as "Dawn" (Arunodaya , 1935), represent obscure philosophical abstractions:

Inside the ear, a mellifluous sound

is drawn out in the fifth note,

the more I submerge to look within,

the more I feel a holy mood

Poems such as "Himalaya" (Himal ) are probably intended to arouse patriotic feeling. Lekhnath approached all his work in the deliberate man-

ner of a craftsman, paying meticulous attention to meter, vocabulary, and alliteration. His primary concern was to create "sweetness" in the language of his poems, and many were rewritten several times before the poet was content with them.

In 1951, Lekhnath was invested by King Tribhuvan with the title of kavi shiromani , which literally means "crest-jewel poet" but is generally translated as "poet laureate." Since his death in 1966, no other poet has been similarly honored, so the title would seem to be his in perpetuity. His first composition after 1950 was a long poem entitled "Remembering the Truth of Undying Light" (Amar Jyotiko Satya-Smriti ), which expressed grief over the death of Mahatma Gandhi. Under the censorious rule of the Rana regime, this would probably have been interpreted as an expression of support for the Nepali Congress Party.

The work that is now regarded as Lekhnath's magnum opus is "The Young Ascetic" (Taruna Tapasi ), published in 1953. "The Young Ascetic" is a lengthy narrative poem concerning a poet stricken by grief at the death of his wife, who sits beneath a tree by the wayside. As he mourns alone, a renunciant sadhu appears before him; this man later turns out to be the spirit of the tree beneath which the poet sits. The sadhu delivers a long homily to the mourning poet: as a tree, rooted to one spot, the sadhu has experienced many hardships and has learned much from his observation of the people who have rested in his shade. Thus, after long years of watchfulness and contemplation, he has achieved spiritual enlightenment. The poem contains much that can readily be construed as symbolism, allegory, and even autobiography. The poet probably represents Lekhnath himself, and the descriptions of the changing seasons are said to represent the advent and departure of the various ruling families of Nepal.

Lekhnath was honored by the Nepali literary world on his seventieth birthday in 1955 when he became the focal point of a procession around the streets of Kathmandu. The procession was probably modeled on the old-age initiation ceremony practiced by the Newars of Kathmandu Valley. The old poet was seated in a ceremonial carriage and paraded through the city, pulled by most of the better known poets of the time and even by the prime minister. In 1957, he was awarded membership in the newly founded Royal Nepal Academy, and in 1969 he was honored posthumously with the prestigious Tribhuvan Puraskar prize. These honors are a mark of the peculiar reverence felt by members of the cultural establishment of Nepal for the man whose poems represent the "classical" aspect of their modern literature. He can no longer escape the scorn of the young, however, and he is rarely imitated by aspiring poets. In an essay published in 1945, Devkota defended the "laureate" from his critics:

Whether poetry should be composed in colloquial language or not is still a matter for dispute: we praise the attempts that are made to utilize the melodiousness of rural or mountain dialects, but this, after all, is not our only resort. Even if one agrees that meter can fragment the flow of poetry, it remains true that less criticism can be made of the poet whose feelings emerge in rounded, smooth, illuminated forms than of the poet who expresses himself in an undeveloped torrent of primitivism. (1945, 223)

Surprisingly little is known about the personal life of the man whose poems are now read and learned by every Nepali schoolchild. In the few portraits that exist, Lekhnath, an old man with a long white beard, peers inquisitively at the camera from behind a pair of cheap wire-framed spectacles. Born into a tradition of conservative and priestly scholasticism, he was innovative enough to compose poems in his mother tongue that dared to make occasional references to contemporary social realities, and he also brought the discipline and refinement of ancient Sanskrit conventions to the development of Nepali poetry.

The essential quality of much of Lekhnath's poetry derives mainly from his choice of vocabulary and his use of meter and alliteration; it is therefore rather less amenable to effective translation than the works of most later poets, a fact reflected by the small number of poems translated here. Of these, "A Parrot in a Cage" has been slightly abridged: the Nepali poem contains 25 verses. A translation of Reflections on the Spring , completed some years ago, has with some regrets been deleted from this selection. Many of the one hundred couplets that make up this famous poem are merely exercises in alliteration and rhyme, and as a whole Reflections on the Spring tends to defy translation.

Most of Lekhnath Paudyal's shorter poems are collected in Lalitya (Delicacy), published in two volumes in 1967 and 1968. His longer works —khanda-kavya and mahakavya —are (with dates of first publication) Ritu Vichara (Contemplation of the Seasons, 1916), Buddhi Vinoda (Enjoyments of Wisdom, 1916), Satya-Kali-Samvada (A Dialogue Between the Degenerate Age and the Age of Truth, 1919), Amar Jyotiko Satya-Smriti (Remembering the Truth of Undying Light, 1951), Taruna Tapasi (The Young Ascetic, 1953), and Mero Rama (My God, 1954). Another epic poem, entitled Ganga-Gauri (Goddess of the Ganges), remains unfinished.

A Parrot in a Cage (Pinjarako Suga)

A pitiful, twice-born[1] child called parrot,

I have been trapped in a cage,

[1] Dvija means "twice born" and therefore of Brahman, or possibly Vaishya, caste.

Even in my dreams, Lord Shiva,

I find not a grain of peace or rest.

My brothers, my mother and father,

Dwell in a far forest corner,

To whom can I pour out my anguish,

Lamenting from this cage?

Sometimes I weep and shed my tears,

Sometimes I am like a corpse,

Sometimes I leap about, insane,

Remembering forest joys.

This poor thing which wandered the glades

And ate wild fruits of daily delight

Has been thrust by Fate into a cage;

Destiny, Lord, is strange!

All about me I see only foes,

Nowhere can I find a friend,

What can I do, how shall I escape,

To whom can I unburden my heart?

Sometimes it's cold, sometimes the sun shines,

Sometimes I prattle, sometimes I am still,

I am ruled by the fancies of children,

My fortune is constant change.

For my food I have only third-class rice,

And that does not fill me by half,

I cast a glance at my water pot:

Such comforts! That, too, is dry!

Hoarse my voice, tiresome these bonds,

To have to speak is further torment,

But if I refuse to utter a word,

A stick is brandished, ready to beat me.

One says, "It is a stupid ass!"

Another cries, "See, it refuses to speak!"

A third wants me to utter God's name:

"Atma Ram, speak, speak, say the name!"

Fate, you gave my life to this constraint,

You gave me a voice I am forced to use,

But you gave me only half my needs;

Fate, you are all compassion!

And you gave me faculties both

Of melodious speech and discerning taste,

But what do these obtain for me, save

Confinement, abuse, constant threats?

Jailing me, distressing me,

Are the curious sports Man plays,

What heinous crimes these are,

Deliver me, thou God of pity.

Humanity is all virtue's foe,

Exploiting the good till their hearts are dry,

Why should Man ever be content

Till winged breath itself is snatched away?

While a single man on this earth remains,

Until all men have vanished,

Do not let poor parrots be born,

Oh Lord, please hear my prayer!

(1914/17; from Adhunik Nepali Kavita 1971)

Himalaya (Himal)

A scarf of pure white snow

Hangs down from its head to its feet,

Cascades like strings of pearls

Glisten on its breast,

A net of drizzling cloud

Encircles its waist like a gray woolen shawl:

An astounding sight, still and bright,

Our blessed Himalaya.

Yaks graze fine grass on its steepest slopes,

And muskdeer spread their scent divine,

Each day it receives the sun's first embrace:

A pillar of fortune, deep and still,

Our blessed Himalaya.

It endures the blows of tempest and storm,

And bears the tumult of the rains;

Onto its head it takes the burning sun's harsh fire,

For ages past it has watched over Creation,

And now it stands smiling, an enlightened ascetic,

Our blessed Himalaya.

Land of the Ganga's birth,

Holy Shiva's place of rest,

Gauri's jeweled palace of play,[2] Cruel black Death cannot enter

This still, celestial column,

Our blessed Himalaya.

It nurtures mines of precious gems,

And gives pure water, sweet as nectar,

[2] Gauri is a name of Parvati, spouse of Shiva.

And they say it still contains

Alaka, the Yaksha's capital;[3] Climbing to its peak, one's heart

Is full of thoughts of heaven,

Thus bright with light and wealth,

Our blessed Himalaya.

(from Adhunik Nepali Kavita 1971; also included in Nepali Kavita Sangraha [1973] 1988, vol. 1)

Remembering Saraswati (Saraswati-Smriti

She plays the lute of the tender soul,

Plucking thousands of sweet sounds

With the gentle nails of the mind,

As she sits upon the heart's opened lotus:

May I never forget, for the whole of my life,

The goddess Saraswati.[4]

She wears a crystal necklace

Of clear and lovely shapes,

It refines the practical arts of this world,

And my heart ever fills with her waves of light:

May I never forget, through the whole of my life,

The goddess Saraswati.

She keeps the great book of remembrance,

Recording all things seen, heard, and felt,

All are entered in their fullness,

And nothing is omitted:

May I never forget, through the whole of my life,

The goddess Saraswati.

She rides the quick and magical swan[5] Which dives and plays in our hearts' deep lake,

And she brings to life the world's games and their glory:

May I never forget, through the whole of my life,

The goddess Saraswati.

"When you come to comprehend

The world-pervading sweetness

Of this my art of living,

Your fear and ignorance must surely end."

With this she gestures reassurance:

[3] The Yakshas are attendants to the god of wealth, Kubera, who dwells in the fabulous city of Alaka.

[4] Saraswati, consort of the god Brahma, is patron of the arts and literature.

[5] Each Hindu deity has his or her own "vehicle"; Saraswati is borne by a swan.

May I never forget, through the whole of my life,

The goddess Saraswati.

(from Adhunik Nepali Kavita 1971)

An Ode to Death (Kal Mahima)

It knows naught of mercy, forgiveness, love,

It makes neither promises nor mistakes,

And never is it content,

Indra himself may bow down at its feet,[6] But it heeds not Indra's plea,

It does not pick through the pile,

Dividing sweet from sour,

But checks through all our records;

It never strikes in error.

Kings and paupers are all alike,

It picks them up and bears them away,

Never put off till its stomach is filled;

Medicine's cures present no threat,

Like an undying hunter, it moves unseen.

It bathes in pools of tears,

It dislikes all cool waters,

Without a dry old skeleton

It cannot make its bed,

It wears no more than ashes,

Sings naught but lamentation.

Everything is gulped straight down,

To pause and chew would mean starvation,

All that is swallowed is spewed straight out,

Nothing is digested, through long ages,

Death's hunger never sated.

(from Adhunik Nepali Kavita 1971)

Last Poem (Akhiri Kavita)

God Himself endures this pain,

This body is where He dwells,

By its fall He is surely saddened,

He quietly picks up His things, and goes.

(1965?; from Adhunik Nepali Kavita 1971)

[6] Indra is the mighty Hindu god of war and of the rains.

Balkrishna Sama (1903-1981)

Lekhnath Paudyal, Balkrishna Sama, and Lakshmiprasad Devkota were the three most important Nepali writers of the first half of this century, and their influence is still felt today. Lekhnath strove for classical precision in traditional poetic genres; Devkota's effusive and emotional works provoked a redefinition of the art of poetic composition in Nepali. In contrast to both of these, Balkrishna Sama was essentially an intellectual whose personal values and knowledge of world culture brought austerity and eclecticism to his work. He was also regarded highly for his efforts to simplify and colloquialize the language of Nepali verse.

Sama was born Balkrishna Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana in 1903. As a member of the ruling family, he naturally enjoyed many privileges: his formative years were spent in sumptuous surroundings, and he received the best education available in Nepal at that time. In 1923 he became a high-ranking army officer, as was customary for the sons of Rana families, but from 1933 onward he was able to dedicate himself wholly to literature because he was made chair of the kingdom's main publishing body, the Nepali Language Publication Committee. He changed his name to Sama , "equal," in 1948 after spending several months in prison for his association with political forces inimical to his family's regime. It is by this pseudonym that he is now usually known. Sama is universally regarded as the greatest Nepali playwright, and it was primarily to drama that he devoted his efforts during the first half of his life. In recognition of his enormous contribution to the enrichment of Nepali literature, he was made a member of the Royal Nepal Academy in 1957, its vice-chancellor in 1968, and a life member after his retirement in 1971.

The young Balkrishna seems to have been unusually gifted because

he began to compose metrical verses before he was eight years old, imitating those of his father and his tutor, the father of Lakshmiprasad Devkota. Balkrishna conceived an affection for music and art and developed a sense of reverence for sacred literature, particularly the Ramayana of Bhanubhakta: "Up until then, it had never occurred to me that the Ramayana was the work of a human being. When I watched my sister bowing down before the book, I thought it had been created by one of the gods!" (Sama 1966, 14).

At school, he read William Wordsworth and other English poets and even translated the poem "Lucy Gray" into Nepali in 1914. He was also impressed by Lekhnath Paudyal's "Ritu Vichara, " and Lekhnath's influence is clearly discernible in Balkrishna's earliest compositions. His first play, Tansenko Jhari (Rain at Tansen), which he wrote in 1921, used the classical anushtup meter, and he wrote most subsequent dramas in verse forms. These included the classic works of Nepali theater: Mutuko Vyatha (Heart's Anguish, 1929), Mukunda-Indira (Mukunda and Indira, 1937), and Prahlad (1938). Sama was undoubtedly influenced by Shakespeare's use of verse in drama and experimented with unorthodox metrical combinations, showing scant regard for the rules of Sanskrit prosody.

Sama was also an accomplished painter and story writer, as well as the author of a speculative philosophical treatise, Regulated Randomness (Niyamit Akasamikta ). His poetry represented the second facet of his literary personality, although it was certainly no less important to him than his plays. All of his poems were published as a single collection in 1981, with the exception of two long works that appeared separately. It is clear from this volume that Sama produced far more poetry in his later years than in his youth: less than forty poems were published before 1950, but more than one hundred and fifty appeared between 1950 and 1979. T. Sharma (1982, 92) believes that Sama's poems fall into four categories. The earliest were fairly conventional compositions in Sanskrit meters and were followed by the many songlike poems that are sprinkled throughout Sama's first verse dramas. After 1950, he produced poems that dealt with philosophical themes in ancient Vedic meters, as well as thematically similar poems written in free verse. The earlier compositions were more formulaic than later works, although Sama's interest in experimentation was clearly evident at an early stage. In "Broken Vase" (Phuteko Phuldan , 1935), for instance, the opening verse is symbolically shattered and fragmented:

oh the vase . . . from my hand...

slipped . . . fell to the floor . . . broke with a crack

. . . water spilled . . . flowers, too,

. . . smashed . . . to smithereens!

His most famous nonmetrical poems are praised for the sweetness and simplicity of their language and often have a strong didactic tone. If they have a fault, it is their tendency to become long-winded and humorless. Sama was a rationalist and an agnostic, which made him highly suspect in the eyes of the rulers. His personal beliefs were set forth in poems such as "Man Is God Himself" (Manis Svayam Devata Huncha ), translated here, and a longer poem, "I, Too, Believe in God" (Ma Pani Dyauta Manchu ):

I, too, believe, holy man,

I, too, believe in God,

but between your God and mine

there is the difference of earth and sky.

Him you see when you close your eyes

in meditation's abstract clouds,

Him I see with my eyes wide open

in the dear sight of every man.

The subject of many poems was poetry itself: one of his longest works, "Sight of the Incarnation" (Avatar-Darshan, 1973) is a seventeen-page prose poem that describes a dream in which Sama encountered the goddess of poetry, presumably Saraswati. Extracts from this poem are presented here. Sama's incomplete autobiography is entitled My Worship of Poetry (Mero Kavitako Aradhana ), and the composition of poetry evidently meant far more to Sama than a mere literary pursuit. This attitude to poetry, common to all South Asian poets of earlier generations, is derived from ancient classical traditions, as expounded by the tenth-century poet Rajashekhara in his Kavya-Mimamsa (Treatise on Poetry). This attitude continued to influence Nepali poets well into the present century. Sama's literary perspective was far broader than that of thoroughly traditional poets such as Lekhnath, however, and his exposure to Western literatures and knowledge of world affairs led him to conduct a number of unusual experiments.

Among the most ambitious of these was a long poem in free verse entitled Fire and Water (Ago ra Pani ), which was published in book form in 1954. In Fire and Water , Sama attempted to describe the whole history of humankind as a struggle between the forces of good (water) and evil (fire):

Golden fire, silver water,

ruby spark and diamond snow,

their confrontation is not new,

their lack of concord, constant conflict,

struggle, tangle, war and scrabble,

slaughter, murder: these all began in long ages past.

Certain passages of Fire and Water are remarkable, but the work as a whole is somewhat overcontrived, and its concluding chapters, which describe a utopia governed by "regulated randomness," are unconvincing. Despite these shortcomings, Fire and Water is considered, with some justification, to have been a bold and significant new venture in Nepali literature.

Sama's second major poetic work was a full-blown epic (mahakavya ) entitled Cold Hearth (Chiso Chuhlo ), published in 1958. Its theme was a tragic love affair between two young people divided by a difference in caste. Part of the epic's novelty lay in the fact that its various characters spoke in a diction that imitated that of other Nepali poets. Cold Hearth also demonstrated Sama's erudition and represented his humanistic rejection of the Sanskrit convention that holds that the hero of an epic must be a character of high birth and nobility: the central character of the story was Sante Damai, a low-caste tailor. Critics generally agree that Cold Hearth is diffuse and overextended and that it ranks somewhat lower than Fire and Water and "Sight of the Incarnation" among Sama's major poetic works.

All of Sama's shorter poems (including "Sight of the Incarnation") are collected in Balkrishna Samaka Kavita (The Poems of Balkrishna Sama, 1981), and some appeared in English translation in Expression after Death (1972). The two long works Ago ra Pani (Fire and Water) and Chiso Chuhlo (Cold Hearth) were published in 1954 and 1958 respectively.

Man Is God Himself (Manis Svayam Devata Huncha)

He who loves flowers has a tender heart,

he who cannot pluck their blooms

has a heart that's noble.

He who likes birds has a gentle soul,

he who cannot eat their flesh

has feelings that are sacred.

He who loves his family

has the loftiest desires,

he who loves all of Mankind

has the greatest mind.

He who lives austerely has the purest thoughts,

he who makes life serve him well

has the greatest soul.

He who sees that Man is Man

is the best of men,

he who sees that Man is God,

he is God himself

(1968; from Sama 1981)

I Hate (Ma Ghrina Garchu)

I hate the loveliest star-studded silks,

I hate the scent of the prettiest flower,

I hate the moonlight's thin, lacy veil,

I hate your sweetest love song,

because, because,

they come between your lips and mine.

(1968; from Sama, 1981)

Aall-Pervading Poetry (Kavitako Vyapti)

Picking up a huge basket, a holy man

ventured out to the forest to gather poetry.

Through hills and streams, pastures and fields,

he searched every waterfall, fruit and bush,

but nowhere could he find it,

so he decided such things were out of season,

at a loss he had set off home

when he came upon an aesthete.

To his enquiry this man replied,

"Is poetry not everywhere?

If you look at those falls through prosaic eyes,

even they will be dry, just declaring the void

left by the hair which falls out as youth passes;

but what could dry up these waters,

or make this hillside bald?

"Holy man, look with redoubled love

at the heart's smooth surface

where foaming blood gathers;

gather up all this sad world's blows,

attack with a powerful breath;

lift waves of experience to your head,

scatter pure drops till your eyes are wet,

make your vision subtle with sympathy,

look closely: you will see the blood

which runs through the veins of these rocks,

you will touch the hearts of stones,

the cliffs will shower nectar,

you will have poetry to drink!"

With this the aesthete faded away,

melting like beeswax in the sun,

and the holy man's eyes softened too.

The trees melted like resin, the fruits like honey,

the green fields dissolved into lakes,

the whole world thawed like snow,

the sky dissolved to become the Ganga,

the stars were all droplets of water.

And then the holy man knew

he meant no more than a teardrop;

throughout the world, in each atom's womb,

pervading destruction's terrible sound,

he found poetry surging forth.

(1972; from Sama 1981; also included in Pachhis Varshaka Nepali Kavita 1982)

From Sight of the Incarnation (Avatar-Darshan)

She came before me incarnate,

the mother of the universe, beautiful verse,

snatching sun-flowers, scattering star-leaves,

streaks of dark cloud her agile pen,

their rain her ink,

the poems she wrote were lines

of heavenly lightning-letters,

making the moon sing softly,

making the thunder echo a song

that only the moonbird could hear.

She came dancing, her slim body of spotless crystal,

and as she spread her veil of delusion I doubted

that I had truly seen.

She came like my mind's reflection,

she surely came,

but what of this watcher's reform?

On trembling elbows, my head bowed low,

I try to crawl on four limbs of rhyme

toward poetry's tempting light,

but into a trap I tumble

to struggle there like a four-legged beast,

with no prospect of further progress:

my weight makes me sink ever deeper.

Or maybe I am a black insect,

tumbling onto the wrong path,

prostrate in despair on a slippery rock,

waving four legs at the empty sky.

I saw Poetry's tangible image,

the speech of the cosmos incarnate,

beauty and joy I witnessed,

but what could I do? I could not touch her feet,

I could not bow low with a change in my heart,

no words of strong love could I find,

I could not fly, could not dissolve in the Goddess.

Poetry, Poetry, was it an illusion,

that sight of your lovely incarnation? If so,

whence came such joy? I could not guess

at such joy in the world,

except the bliss which springs from your touch.

I write, remembering things from my past,

but most I forget—all that remain are the dregs

which cling in an emptied jug.

Yesterday is met by today,

today obscured by tomorrow,

tomorrow wiped out by the following day,

each second erases our footprints,

wandering around, awaiting death,

one sleep shatters scores of resolutions.

Death closes our eyes and makes us forget

the things we aimed for in life. I write what I remember,

but Great Death tells me, if my heart should stop

as the morning sun climbs high tomorrow,

I would go to embrace the fire,

forgetting my resolves,

forgetting that fire can burn. But still

I begin to relate the events I recall,

I cannot account for all the blows inflicted,

but write all I can of important times.

I remember him who caused me pain,

but forget the one who wiped my tears,

I remember him who wounded me,

he who healed me I forget,

I remember the man who brought me fear

but forget the one who always consoled,

I remember the ones I have loved,

forgetting those who loved me.

Though I am a sinner, ungainly and unvirtuous,

I will never forget that sacred vision,

I feel you came just now: still I see you,

all before me fades away

as your feet approach with the sound

of ringing anklet bells...

Where have they gone, those lovely childhood hours,

when I lived through each day and night

as if they were my body?

All that once was has passed away,

all that was not has come to pass,

the future holds all that the present lacks.

Still the days are fine, sun and moon undiminished,

Dasain and Tihar come adorned as before,[1] Dasain comes anointing foreheads with red,

making the rupees ring, then comes Tihar,

applying strokes of sandalwood paste,

adding dashes of color in lines,

filling mouths with fruits, piling garlands high,

cracking chestnuts with the teeth.

But now such lovely feasts bring dreams,

dreams from the past which tell only of death,

and that high peak of festivals melts,

springs of tears burst from the eyes,

pools of water collect and soon

the dam is breached and they fall.

Garlands, anointments, are all washed away,

the heart is uneasy, the mouth is dry,

unswallowed fruits stick in the throat.

Where has that burning childhood fled?

What of the golden sun, the silvery moonlight?

What of the gilded finial set by the sun

on silver mountains made by the moon?

They are no longer seen,

now only cold snow is heaped on the mountains,

their peaks always bear fresh wounds,

inflicted by dark ignorance, by insane selfishness,

whose hunger gnaws ever deeper:

that time is gone like the sky itself.

I remember that day of my vision,

I was nine years old, new things fell to new eyes

all around, the sky was as clear

as an ideal, I thought it would reflect the earth,

all upside-down. There was sweet new sunshine,

transparent and soft, a display of colors

surrounded me with grandeur. Tall trees danced

with classical gestures, bending from the waist,

whispering their songs, lifting their hands

to stir the white clouds with brushes,

weaving poetry, poetry! In this movement I felt

I might clearly see you take shape;

the air was ringing with bird song

as if your voice would burst out—then it flared!

[1] Dasain is an important festival celebrated in honor of the fearsome goddess Durga during the month of Ashwin (September-October). It is part of a long national holiday in Nepal that involves the slaughter of buffalo and other livestock and the anointing of foreheads with their blood. Tihar is a name for the Diwali festival of lights.

You appeared, I saw you! In your face

I found such joy that now I know

no other happiness in this life.

This is no fulfillment,

it is a lifelong thirst,

a hope which will last until the pyre

raises its last flag of flame.

(1973; from Sama 1981)

Lakshmiprasad Devkota (1909-1959)

When a truly great poet appears during an important phase in the development of a particular literature, the fortunes of that literature are changed forever. All poets who follow are bound to the traditions that their great predecessor has established, even if it is only in the sense that these become the conventions against which they rebel, the norms from which they make their departures. The contributions made to the development of Nepali poetry by Bhanubhakta, Bhatta, Lekhnath, and Sama have been fundamental, yet Devkota stands head and shoulders above all of these. An American scholar of comparative literature has written, "In Devkota we see the entire Romantic era of Nepali literature" (Rubin 1980, 5), but this is an oversimplification or even an understatement. In Nepali, Devkota's works have formed a colossal touchstone and are the undisputed classics of his language.

In the short space of twenty-five years Devkota produced more than forty books, and his works included plays, stories, essays, translations from world literature, a novel, and poems that ranged in length from a 4-line rhyme to an epic of 1,754 verses. His writings were certainly extraordinarily profuse, but they were also remarkable for their intellectual and creative intensity. Devkota rarely returned to a poem to revise or edit, being in too great a hurry to commence his next composition, nor was he averse to using little-known dialect words to enrich his vocabulary. As a result, some poems suffer from obscurities that puzzle even the most scholarly Nepali reader. Nevertheless, little that Devkota wrote would now be considered dispensable.

Born into a Brahman family in Kathmandu in 1909, Devkota was educated at the Durbar High School and Trichandra College in the capital and received a B.A. in 1930. Married at sixteen years of age, he

became a father at nineteen, and most of the rest of his life was a struggle to support his family, usually by teaching, although he briefly held governmental posts in later years. He often complained bitterly that it was impossible for him to earn a living from writing alone. A prey to deep depressions, Devkota was confined to an Indian mental home in 1939 and was almost suicidal after the death of his son in 1952. His life was a series of financial problems and personal sorrows, but through them all shone a personality of humor, warmth, and deep humanity. These personal ups and downs never retarded the growth of his genius; in fact, some of his best humorous poetry was written in the most tragic circumstances. Certain events in Devkota's life, such as his pilgrimages to the mountain lakes north of Kathmandu in the 1930s, the time he spent in a mental hospital, his employment as a writer and translator from 1943 to 1946, and his subsequent political exile in Banaras can be identified as definite influences on his work. To some extent, however, Devkota's poetry often seems to have been a kind of "inner life" in which he found solace and optimism despite the trials of everyday life.

The life and works of Lakshmiprasad Devkota have been described and analyzed at length in scholarly works in Nepali (see, for instance, Pande 1960; K. Joshi 1974; and Bandhu 1979) and in a recent study published in English to which readers are referred for more detailed biographical information (Rubin 1980). Because Devkota's oeuvre is so immense, and because his greatest achievements are to be found in epics such as Shakuntala Mahakavya, Sulochana , and Prometheus , the introduction and translations presented here offer only a glimpse of a talent that was unprecedented in Nepali poetry.

Devkota's earliest poems reveal the powerful influence of English Romantic verse. Many of the poems collected in The Beggar (Bhikhari ) celebrate the fundamental goodness of humble people, as typified by "Sleeping Porter" (Nidrit Bhariya ), or look back with longing to the innocence of childhood:

We opened our eyes to a glimmering world,

in wonder we wandered freely,

playing games celestial,

running in bliss and ignorance

Soon, however, Devkota began to spice his poetry with a flavor that was essentially Nepali, and Muna and Madan (Muna-Madan ) marked an important stage in this development. Muna and Madan is based on an old Newar folktale (D. Shreshtha 1976) and derives much of its considerable charm from its simple language and musical meter. Devkota broke new ground by becoming the first Nepali poet to employ the jhyaure meter of the folk song, despised by earlier poets as vulgar and unfitting

for serious poetry. He defended this novel move with an appeal to patriotic sentiment:

Nepali seed, Nepali grain, the sweetest song,

watered with the flavor of Nepal;

which Nepali would close his eyes to it?

If the fountain springs from the spirit,

will it not touch the heart?

The plot of Muna and Madan can be summarized as follows: Madan, a trader, resolves to go to Tibet to seek his fortune. He intends to spend only a few weeks in Lhasa and then to return to Kathmandu to grant his aging mother her final wishes. Muna, his wife, is sure that he will never return and begs him not to go. Madan ignores her pleas, and once he has arrived in Lhasa, he becomes entranced by the city's beauty. Suddenly he realizes that he has stayed too long in Tibet, and he sets off home but falls sick with cholera on the way. In Kathmandu, a suitor tells Muna that her husband has perished. But in fact, he has been rescued by a Tibetan, who nurses him back to health. By the time Madan returns home, both his mother and his wife have died, one of old age and the other of a broken heart. Madan decides that he will follow them, and he also passes away at the end of the poem.

Although it is primarily a romantic tragedy designed to tug at the heartstrings, Muna and Madan contains a number of moral statements and comments on the Nepali society of its time. The melodramatic climax of the tale makes its principal message clear: loved ones are far more precious than material wealth. Certain passages from Muna and Madan have the quality of proverbs and are often quoted by ordinary Nepalis in the course of their everyday lives:

hataka maila sunaka thaila ke garnu dhanale?

saga ra sisnu khaeko bes anandi manale!

Purses of gold

are like the dirt on your hands,

what can be done with wealth?

Better to eat only nettles and greens

with happiness in your heart.

The most progressive element of the poem is its implicit rejection of the importance of caste: Madan is saved by a Tibetan, a meat-eating Buddhist, described by Rubin (1980, 31) as a "Himalayan Samaritan," whom an orthodox Hindu would regard as untouchable. Here, the poem proclaims a belief in the goodness of humble people:

This son of a Chetri touches your feet,

but he touches them not with contempt,

a man must be judged by the size of his heart,

not by his name or his caste.

Muna and Madan was Devkota's most beloved composition: on his deathbed he made the famous remark that even though all of his works might perish after his demise, Muna and Madan should be saved. It is also the most popular work in the whole of Nepali literature: in 1936, only 200 copies were printed, but by 1986 it had entered an eighteenth edition, for which 25,000 copies were produced. In 1983 alone, more than 7,000 copies were sold.[1]

Muna and Madan represented something of a watershed in the development of Nepali literature, but it was a minor work in comparison with the great flood of poetry that Devkota unleashed in subsequent years. Between 1936 and his death in 1959, Devkota produced many works on a far more grandiose scale, as well as a wealth of shorter poems that now fill nearly thirty volumes. The five poems presented here in translation shed light upon separate facets of Devkota's poetic personality: "Sleeping Porter" is typical of his early period, during which, as I have noted, his tone and philosophical stance were strongly reminiscent of English poets such as Wordsworth. Muna and Madan was his first great success, a romance written in a melodic meter and simple language that struck a chord in the minds of ordinary Nepali readers. "Prayer on a Clearing Morning in the Month of Magh" (Maghko Khuleko Bihanko Jap ) is an entirely different composition because it weaves together references to Hindu mythology and descriptions of natural beauty to offer an insight which is deeply personal but also resounds with a profundity which is universal. "Mad" (Pagal ), on the other hand, is a poetic expression of the personal philosophy that Devkota developed in his essays (1945) and was clearly inspired by his experiences of the asylum at Ranchi:

When I saw the first frosts of Time

on the hair of a beautiful woman,

I wept for three days:

the Buddha was touching my soul,

but they said that I was raving!

"Mad" also communicates a political message that can be described as revolutionary:

Look at the whorish dance

of shameless leadership's tasteless tongues,

watch them break the back of the people's rights.

[1] This statistic was reported in the English language daily The Rising Nepal , January 17, 1984. Nepali literary publications are usually printed in editions of 1,000 copies.

For Lekhnath and Sama, poetry was ultimately a discipline that had to be painstakingly acquired and cultivated. For Devkota, however, and particularly in his later years, poetry was "a hill stream in flood" or "a spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings." Devkota died while he was still developing his craft and entering new fields of endeavor. Indeed, as the deathbed poem "Like Nothing into Nothing" (Shunyama Shunyasari ) demonstrates, he continued to compose until hours before his demise. His death was Nepal's eternal loss: despite the poems' flaws-and inconsistencies, it seems extremely unlikely that his poems will ever come to be considered wholly "outdated" or that his genius will ever be deemed unworthy of emulation.

Much of Devkota's poetry was not published until after his death in 1959. In the following titles, arranged in approximate order of composition, dates given are of first publication.

Devkota's shorter poems are collected in Bhikhari (The Beggar, 1953), Putali (The Butterfly, 1952), Gaine Git (Minstrel Songs, 1967), Bhavanagangeya (The Ganges of Emotion, 1967), Akash Bolcha (The Sky Speaks, 1968), Sunko Bihana (Golden Morning, 1953), Manoranjana (Enjoyments, 1967), Janmotsava Mutuko Thopa (Tears of a Birthday Heart, 1958), Chahara (Cascade, 1959), Chilla Pataharu (Smooth Leaves, 1964), Katak (The War, 1969), Changasanga Kura (Conversations with a Waterfall, 1966), Lakshmi-Kavita-Sangraha (Collection of "Lakshmi's" Poems, 1976), and Mrityushayyabata (From the Deathbed , 1959).

The shorter narrative poems, khanda-kavya , and verse-dramas are Muna-Madan (Muna and Madan, 1936), Savitri-Satyavan (Savitri and Satyavan, 1940), Rajakumar Prabhakar (Prince Prabhakar, 1940), Mhendu (The Flower, 1958), Krishibala (The Peasant Girl, 1964), Sitaharana (The Abduction of Sita, 1968), Dushyanta-Shakuntalabheta (The Meeting of Dushyanta and Shakuntala, 1968), Luni (Luni [a woman's name], 1966), Kunjini (Girl of the Groves, 1945); Ravana-Jatayu-Yuddha (The Battle of Ravana and Jatayu, 1958), Pahadi Pukar (Mountain Cry, 1948), Navarasa (The Nine Sentiments, 1968), Mayavini Sarsi (Circe the Enchantress, 1967), Vasanti (Girl of the Spring, 1952), Maina (Maina [a woman's name], 1952), and Sundari Projarpina (The Fair Prosperina, 1952).

Devkota's epic poems (mahakavya ) are Van-Kusum (Forest Flower, 1968); Shakuntala Mahakavya (The Epic of Shakuntala, 1945), Sulochana (Sulochana [a woman's name], 1946), Maharana Pratap (King Pratap, 1967), and Pramithas (Prometheus, 1971).

Sleeping Porter (Nidrit Bhariya)

On his back a fifty-pound load,

his spine bent double,

six miles sheer in the winter snows;

naked bones;

with two rupees of life in his body

to challenge the mountain.

He wears a cloth cap, black and sweaty,

a ragged garment;

lousy, flea-ridden clothes are on his body,

his mind is dulled.

It's like sulphur, but how great

this human frame!

The bird of his heart twitters and pants;

sweat and breath;

in his hut on the cliffside, children shiver:

hungry woes.

His wife like a flower

searches the forest for nettles and vines.

Beneath this great hero's snow peak,

the conqueror of Nature is wealthy

with pearls of sweat on his brow.

Above, there is only the lid of night,

studded with stars,

and in this night he is rich with sleep.

(1958; from Devkota 1976)

From Muna and Madan (Muna-Madan)

Muna Pleads with Madan

Madan:

I have only my mother, my one lamp of good auspice,

do not desert her, do not make her an orphan,

she has endured nigh sixty winters,

let her take comfort from your moonlight face.

Muna:

Shame! For your love of your mother

could not hold you here,

not even your love for your mother!

Her hair is white and hoary with age,

her body is weak and fragile.

You go now as a merchant

to a strange and savage land,

what's to be gained, leaving us for Lhasa?

Purses of gold

are like the dirt on your hands,

what can be done with wealth?

Better to eat only nettles and greens

with happiness in your heart.

Madan Goes to Tibet

Hills and mountains, steep and sheer,

rivers to ford by the thousand:

the road to Tibet, deserted and bare,

rocks and earth and poison drizzle,

full of mists and laden with rain,

the wandering wind as cold as ice.

Monks with heads round and shaven,

temples and cremation pillars,

hands and feet grow numb on the road

and are later revived by the fire,

wet leafy boughs make the finest quilts

when the teeth are ringing with cold,

even when boiled, it's inedible:

the rawest, roughest rice.

At last, roofs of gold

grace the evening view:

at the Potala's foot, on the valley's edge,

Lhasa herself was smiling,

like a mountain the Potala[2] touched the sky,

a filigreed mountain of copper and gold.

The travelers saw the golden roof

of the Dalai Lama's vast palace,

where golden Buddhas hid behind yak-hair awnings,

graven rocks of every color, embroidered like fairy dresses,

snowcapped peaks, waters cool,

the leaves so green, mimosa flowers

blooming white on budding trees.

Muna in Her Solitude

Muna alone, as beautiful as the flowering lotus,

like moonlight touching the clouds' silver shore,

her gentle lips smile, a shower of pearls,

but she wilts like a flower as winter draws near,

and soon her tears rain down.

[2] The Potala is the magnificent palace-cum-monastery that dominates the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, and was the winter residence of the Dalai Lama.

Wiping wide eyes, she tends Madan's mother,

but when she sleeps in her lonely room

her pillow is soaked by a thousand cares.

She hides her sorrow in her heart,

concealing it in silence,

like a bird which hides with its wing

the arrow which pierces its heart.

She is only bright by the flickering lamp

when the day draws to its close.

A wilting flower's beauty grows

while Autumn is approaching,

when the clouds' dark edges are silver

vand the moon shines ever brighter.

Sadness glares in her heart,

recalling his face at their parting,

wintry tears fall on the flower,

starlight, the night's tears

drip down onto the earth.

A rose grows from the sweetest roots,

but roots are consumed by worms;

the bud which blooms in the city

is the prey of evil men;

pure water is sullied

by dirt from a human hand;

men sow thorns in the paths of men.

Most lovely our Muna at her window,

a city rascal saw her, a fallen fairy,

making a lamp for goddess Bhavani,

oblivious to all.

He saw the tender lobes of her ears,

saw her hair in disarray,

and with this heavenly vision

he rose like a madman and staggered away.

You see the rose is beautiful,

but brother do not touch it!

You look with desire, entranced,

but be not like a savage!

The things of Creation are precious gems,

a flower contains the laughter of God,

do not kill it with your touch!

Madan Tarries in Lhasa

Six months had passed, then seven,

suddenly Madan was startled,

remembering his Muna, his mother:

a wave of water rushed through his heart.

A dove flew over the city,

it crossed the river near the ford,

Madan's mind took wing, flew home,

as he sat he imagined returning,

and Muna's eyes were wide with sorrow,

her wide almond eyes.

"Dong" rang the monastery bell,

the clouds all gathered together,

mountain shadows grew long with evening.

Chilled by the wind in sad meditation,

Madan rose up, saw the moon wrapped in wool,

his mother, his Muna, danced in his eyes,

it became clear to him that night,

his pillow was wet with tears.

His heart oppressed by the reddening sky,

he packed his purses of gold away,

he gathered up his bags of musk,

then took his leave of Lhasa,

calling out to the Lord.

Madan Falls Sick on His Journey Home

Here in the pitiless hills and forests,

the stars, the whole world seemed cruel,

he turned over slowly to moan in the grass...

some stranger approached, a torch in his hand,

a robber, a ghost, a bad forest spirit?

Should he hope or should he fear?

His breath hung suspended, but in an instant

the torch was beside him before he knew.

A Tibetan looks to see who is weeping,

he seeks the sick man there,

"Your friends were worthless, but my house is near,

you will not die, I shall carry you home."

Poor Madan falls at his feet,

"At home, I've my white-haired mother

and my wife who shines like a lamp,

save me now and the Lord will see,

he who helps his fellow man

cannot help but go to heaven.

This son of a Chetri touches your feet,[3]

[3] Chetri is the second Hindu caste in Nepal, roughly equivalent to the Indian Kshatriya.

but he touches them not with contempt,

a man must be judged by the size of his heart,

not by his name or his caste."

Madan Departs for Nepal

Far away lies shining Nepal,

where cocks are crowing to summon the light,

as morning opens to smile down from the mountains.

The city of Nepal wears a garland of blue hills,

with trees like earrings on the valley peaks,

the eastern ridges bear rosy clouds,