Organizing a Corporate Economy

The restructuring of mining that began during the early 1850s was completed with the rise of corporate mining on what came to be known as the Comstock Lode in Nevada (then part of Utah Territory) during the 1860s. Miners who crossed the Sierra from California had prospected the area for nearly a decade, barely eking out a living. Then, in June 1859, a party of prospectors discovered a rich ore deposit containing gold and silver.[41] Quickly forming a company, the partners worked their claim. News spread fist, and miners from throughout the West, especially Californians, swarmed to the Comstock. Problems emerged quickly. The mining codes adopted on the Comstock, modeled after California's, ensured that conflicts would develop over claim boundaries and guaranteed that lawsuits would follow. This was hardly surprising in an area that stretched less than three miles, where nearly seventeen thousand claims were quickly recorded.[42] A lively trade in mining claims developed immediately. In his detailed study of the Comstock Lode for the U.S. Geological Survey, Eliot Lord noted that "without and within doors a fever of speculations raged without check. Sales of claims for money were comparatively rare, but barters were incessant. . . . Paper fortunes were made in days.[43]

The original claimholders, lacking both the knowledge and the capital to develop large-scale quartz mining operations, sold out. The buyers included some familiar names: Judge James Walsh, Joseph Woodworth, and George Hearst, all from Nevada County, California.[44] After forming a partnership, the Ophir Mining Company, they undertook the first systematic mining operations on the lode. Before long, they sent a shipment of ore to San Francisco for assay. On November 16, 1859, the San Francisco Alta California reported that the ore revealed an estimated $1,595 in gold and $4,791 in silver per ton, fabulously valuable by California standards. And California standards prevailed on the Comstock. Initial ore assays helped cre-

ate the impression that the Comstock mines would prove rich beyond belief and produce for centuries, similar to the fabled mines of Mexico, Bolivia, and Peru.

As California miners and financiers bought up Comstock properties and established corporations, speculation in mining claims quickly gave way to speculation in mining stock. On April 28, 1860, Hearst and his partners incorporated their mine in California to create the Ophir Silver Mining Company. With $5.04 million in capital stock, the Ophir was the largest corporation in the West. Others quickly followed suit. By the end of 1860, thirty-seven additional Comstock mines were incorporated in California, which triggered a wave of incorporations never before seen in this country. More than one thousand mining companies were incorporated in California that year.[45]

All this activity attracted intense interest, as more and more people hoped to make money in mining stock. While some hoped for more reliable financial reporting, most appeared more interested in the speculative prospects of mining securities.[46] The increase in transactions and opportunities for the collection of brokerage commissions led to the formation of the San Francisco Mining Stock and Exchange Board on September 1, 1862. Although founders of this exchange were branded in the press as the "Forty Thieves," the organization prospered. By 1864, six new mining stock exchanges were formed in San Francisco, and nine in the vicinity of the Comstock Lode, along with exchanges in Sacramento, Stockton, and Marysville.[47] Meanwhile, the number of mining corporations skyrocketed; 2,933 were formed in 1863 alone, 84 percent of them gold and silver mines.[48] California banking historian Ira Cross concluded that "especially during 1863 did it become the normal, expected thing for any party possessing a small mining claim to organize a corporation of large proportions and to sell the stock at astounding prices to a gullible and speculative public."[49] Securities of the Comstock corporations dominated the market. Strangely enough, stock speculation increased, due largely to the production of a single mine, the Gould & Curry[50] Few of the other mines produced profits or paid dividends. Yet, as miners on the Comstock Lode wrestled with technical problems of extracting and processing the complex amalgam of gold and silver found there, financiers and promoters developed sophisticated new methods of organizing companies and manipulating stock transactions. By comparison, California mines continued to have difficulty attracting investments.[51] California's gold mines were much smaller operations. They required far less operating capital than the gold and silver mines on the Comstock Lode and offered fewer opportunities for speculation on the stock market. As Table 3.2 shows, California gold production continued to decline into the 1860s, after which it remained relatively steady, between $15 and $24 million through 1878. While gold and silver on the Comstock Lode did not exceed California's gold output until 1873, the annual transactions on the San Francisco Mining Stock and Exchange Board alone exceeded $100 million a year between 1871 and 1877.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Following the practices adopted a decade earlier, corporate promoters on the Comstock Lode issued elaborate prospectuses that they distributed far and wide. They also enlisted the press in campaigns to sell stock to the public, and with huge success. For the first time in the history of the United States, stock market participants represented a broad cross-section of social classes.[52] San Francisco's Mining and Scientific Press observed that it was the rare person who did not own at least a share or two of mining stock.[53] According to the publication, "the market extends everywhere; the buyers and sellers of stock include the millionaire and the mendicant, the modest matron and the brazen courtesan, the prudent man of business and the gambler, the maidservant and her mistress, the banker and his customer.[54]

As had been the case a decade earlier, close ties developed between banks and mining corporations. Banks managed mining corporation accounts, arranged payrolls, made short-term loans, lent money for the purchase of mining stock, and accepted mining stock as collateral on loans.[55] When production dropped at the Comstock mines, San Francisco banker William C. Ralston and his agent, William Sharon, stepped in to take control. Indeed, close relations between the leading bank on the West Coast, San Francisco's Bank of California, and the Comstock mining corporations lent an air of respectability to mining stock transactions. At the same time, it gave Sharon and Ralston direct access to financial information on local businesses, which they used to advance their own interests.

Enacting a liberal lending policy, Ralston and Sharon lent money to independent mills, but then starved them of ore to process. Without income from ore processing, mills were unable to repay their loans, and Ralston and Sharon gained control over most mills in the area, which they then consolidated as a single corporation, the Union Mill and Mining Company. They held onto these shares, rather than distributing them through the stock market.[56] At the same time, they extended their control over both mines and mine suppliers, which continued to operate as formally distinct corporations.[57] Relying on advance knowledge about progress in the mines, Ralston, Sharon, and their allies, known as the "Bank Crowd," fed rumors to the press and timed assessment calls and stock sales to drive prices up or down according to their plans. According to early historian John S. Hittell, "every trick that cunning could devise to make the many pay the expenses, securing to the few the bulk of the profit, was practiced on an extensive scale.[58]

This broad control, even backed by the financial power of the Bank of California, could not guarantee perpetually growing production at the Comstock mines, however. Nor did it prevent the rise of rival groups to challenge the control wielded by Ralston and his allies. Twice during the 1870s, successful campaigns were waged through the stock market to wrest control of particular mines.[59] Alvinza Hayward and John P. Jones broke away from the Bank Crowd and gained control of the Crown Point and Savage mines. At about the same time, four Irish immigrants soon known

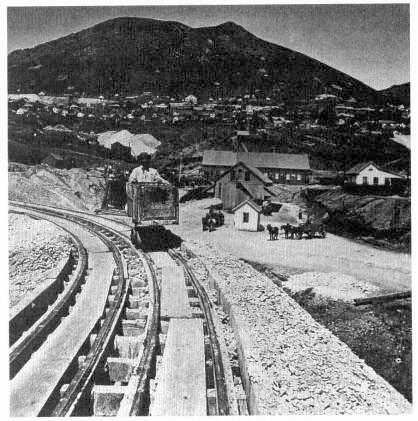

Mount Davidson, on the far western reaches of Nevada, looms above a

miner at the lower dump of the Gould & Curry Mine in 1865. Although the

Comstock Lode entered into decline that year, its fortunes would revive in

the early 1870s, when the Silver Kings struck the "Big Bonanza," the massive

veins of silver and gold buried deep beneath the windswept heights of Mount

Davidson. Financed in large by California capital, the mines not only produced

enormous quantities of high-grade ore but sparked volatile trading in silver

stocks on the San Francisco exchanges. Courtesy Huntington Library, San

Marino, Calif .

as the "Bonanza Firm"— John W. Mackay, James G. Fair, James C. Flood, and William S. O'Brien—formed a formal partnership and pooled their money for stock operations. The resulting growth in stock transactions fueled the formation of a new wave of mining corporations.[60] By 1873, they controlled five mining companies: Hale & Norcross, Gould & Curry, Consolidated Virginia, California, and Ken-tuck[61] The rival campaigns waged through the stock market produced a staggering volume of transactions, peaking in 1874 at more than $260 million, more than ten times the total production of gold and silver from the Comstock that year. Before the

fight to control the Comstock was over, Ralston was mined. Though Sharon and the Bank of California survived, the activities of the Bonanza Firm exacted a heavy toll on the broader economy.

Following the pattern adopted by the Bank Crowd, the Bonanza Firm not only purchased all major suppliers to their mines, they also established an "independent" mill, the Pacific Mill and Mining Company, a corporation that they wholly owned. Such arrangements were so common that, in a trial closely watched throughout the mining West, the Bonanza Firm successfully countered shareholders' complaints of fraud by pleading that the practice represented industry custom.[62]

By the end of the 1870s, the era of the fabulous Comstock was nearly at its end. The mines had been gutted. In 1877, even as the Bonanza Firms mines produced millions in gold and silver, the mining stock market collapsed, and California's economy sank into depression. The California Assembly Committee on Corporations concluded:

Where there should be universal prosperity and happiness, there is widespread poverty and suffering. Thousands of comfortable homes and many millions of dollars earned by the patient toil of the industrious masses, have been swept away by disastrous investments in mining shams. Undoubtedly the stock market has been a chief factor in producing the present destitution of the people. Its baneful effects have been felt in every neighborhood and almost every family in the State.[63]