7

Cats and Categorization

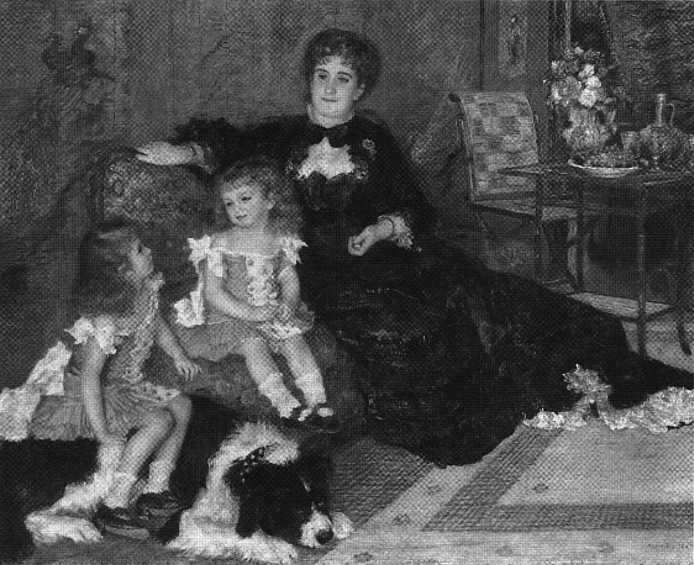

Auguste Renoir's painting of Mme Georges Charpentier and her children (1878) rehearses the major themes of this book. The bourgeois home as cozy retreat, the dog as whimsical signifier of family life, the echo of nature uneasily subdued, these are ideas we easily, even happily, read in a portrait of domestic bliss. If we look very closely at this painting, other themes come to light. As Michael Brenson explains in an article on secondary images in modem art, the "mood of fantasy and enchantment is reinforced by secondary images knitted into or rearing up within the fabric of the painting." A monstrous face within the curtain, skulls in Mme Charpentier's dress, and a cat that seems to rest on the woman's lap and look at her—here are images that intensify the unexpectedly menacing ambiguity in this painting Marcel Proust once called the poetry of the home (figure 9).1

In Renoir's painting of the Charpentier family the cat necessarily appears disguised. It was the anti-pet of nineteenth-century bourgeois life, associated with sexuality and marginality, qualities the cat inherited from medieval and early modem times when cats were sometimes burned as witches. Inverted, the tradition persisted in the nineteenth century, since cats were embraced by intellectuals. Baudelaire notably was a lover of cats. Recall that in the poem "The Cat," his mistress and the animal are one:

Come, superb cat, to my amorous heart;

Hold back the talons of your paws

. . . . . . . . . . . ...

When my fingers leisurely caress you,

Your head and your elastic back,

And when my hand tingles with the pleasure

Of feeling your electric body,

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 9. Pierre Auguste Renoir, Madame Georges Charpentier et ses enfants

(by permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wolfe Fund, 1907; Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection).

In spirit I see my woman. Her gaze

Like your own, amiable beast,

Profound and cold, cuts and cleaves like a dart,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

And, from her head down to her feet,

A subtle air, a dangerous perfume

Floats about her dusky body.2

The cat was sexually charged, independent, dangerous, egotistical, and cruel. By the end of the century, however, it had become a family pet. It had gained a modern pedigree. Breeds were now important as the cat took its place in bourgeois life alongside the dog. Indeed, it came to act as a dog did, in the determining imagination of pet owners. The cat

was neutralized—"rehabilitated," in a telling phrase. Once notoriously faithful to the house, not the person, the cat came to be faithful to its owner even beyond the grave.

Here was an important shift: the rehabilitation of the cat, the inclusion of the feline in bourgeois culture, suggests that by the last decades of the nineteenth century animals had lost some of their power to refract bourgeois life. New metaphors for modernity had developed to link, imaginatively, the symbolism of pets in organic life to the inorganic. The machine now functioned as a new signature for modern times in science fiction beginning with Jules Verne and then, more disturbingly, in futurism and in fascism.

The impulse to categorize that informed nineteenth-century culture remained thematically bound to an organically ordered world. Darwinism, or evolutionism in general, figured minimally in Parisians' thinking about pets. What mattered instead was catachresis, the paradoxical process of inclusion, exclusion, substitution, and completion that powered the postrevolutionary world.3 Ordinary people used inherited notions of animal behavior to describe something new, something that approximated our understanding of class. For them, the sexuality and independence of the cat, the fidelity and malleability of the dog, were self-reflexive building blocks of culture. And uncertainties in categorizing human being and animal, the working class and the bourgeoisie, which this play with values describes, suggest a "fluid relativism" in Linda Nochlin's phrase about realism that informed scientific and ordinary thinking alike—a pliancy that shifted, sadly, in later modernist thought to a more restrictive mechanical plane.4

Buffon is a convenient starting point for our investigation into the place of cats in nineteenth-century culture. The eighteenth century's most widely influential naturalist—-Georges Louis Leclerc, !e comte de Buffon, whose multivolume Histoire naturelle (1749-1788) sold at least twenty thousand copies and whose Petit Buffon had a place in innumerable French homes—remained a touchstone for later debate about feline nature.5 Buffon hated cats. As Pierre Larousse lamented in his dictionary article on cats, "Buffon has darkened the portrait of the cat." In contrast to the dog, the cat was a perfidious animal, an "unfaithful

servant," that one kept only out of absolute necessity, as the lesser of two evils, "to control another enemy of domestic life still more discomforting, which we are unable ourselves to hunt."6

The cat was a wild animal. "[We find] with the cat," Buffon insisted, "that the shape of its body and its temperament are at one with its nature." Its domesticity was sham. Kittens, especially, could be appealing, even gentle, but "at the same time, they have an innate malice, a falseness of character, a perverse nature, which age augments and education can only mask." Cats were furtive and opportunistic. They feigned devotion and civility for the comfort these might bring. "They take easily to the habits of society, but never to its moral attitudes; they only appear to be affectionate," Buffon added. Unlike the frank and trusting canine, cats were devious; "either out of mistrust or duplicity, they approach us circuitously when looking for caresses that they appreciate only," Buffon insisted, "for the pleasure they [themselves] get from them." Cats were self-indulgent, Larousse reiterated in the kindest of Buffon's comments that he included in his Dictionnaire. "The cat is attractive, adroit, clean, and voluptuous; he likes his leisure, he searches out only the softest furniture to sleep and play on."7

Buffon based his valuation of cats, he believed, on careful observation of their behavior. For instance, the untrustworthy character of cats is obvious in their demeanor, he explained, "in their shifty, eyes; they never look directly at the person they love.8 A later commentator puzzled out an even more provocative description of Buffon's way of thinking about cats. Henri Lautard, the Belle Epoque author of Zoophilie ou sympathie envers les animaux: Psychologie du chien, du chat, du cheval, described in his own overwrought style these disturbing sounds of cats in heat that he thought might have stimulated Buffon's imagination. "Wild nights, parties, disputes and love songs, duels and duets, with little regard for our somewhat disturbed sleep, have told Buffon," Lautard explained, "[that] the cat is very inclined to love." Surprisingly, Buffon's female cat was more driven by her desires than the male was, "and, something rare in animals, the female appears more ardent than the male." Buffon vividly described the female cat's overwhelming need for sex: she invites it, calls for it, announces her desires by her piercing cries, or rather, the excess of her needs." Driven by sexual desire, the female forced herself

on an often reluctant male, "and when the male runs away from her, she pursues him, bites him, and forces him, as it were, to satisfy her," despite the pain of copulation. "Although these approaches are always accompanied by sharp pain," Buffon carefully and delicately explained.9

Buffon's stunning association of the cat with rapacious feminine sexuality seems to have been informed by a pre-Enlightenment understanding of the cat. Robert Delort, the medievalist and occasional animal historian, suggests that from the early Middle Ages onward writers have endowed the cat with dangerous feminine qualities. In the image of the cat in Western culture, "One finds woman, sexuality, sensuality, love, mystery, likewise, darkness, evil, and danger." This characterization of the cat as both feminine and sensual was an inheritance from German and Egyptian paganism. Absorbed within Christianity, but uneasily, the cat centered on itself all that was suspect in European life. "One detects a strong hostility for all that [the eat] represents: sexuality, sensuality, femininity, paganism, the moon, darkness, blackness, Diana, treachery, cruelty, demons, that is to say, the greater part of the instruments of witchcraft," Delort explains,10

Cats were ritually murdered. They were sacrificed in fertility rites and in rites of purification and protection. At Metz during Lent on "cat Wednesday," at a ceremony first recorded in x 344 and last performed in x777, thirteen cats were placed in an iron cage and burned (a similar instance was recorded in Lorraine in 1905). Cats were burned also on the festival of Saint-Jean, which marked the end of the sowing season. In Paris this bonfire of felines was performed in the place de Grève.11

Roger Chartier warns against a naive assumption that the cat had a fixed meaning in early modern culture.12 But like canine fidelity, feline perfidy and sexuality were qualities, the tenacious interest in Buffon indicates, that nineteenth-century citizens were ready to appropriate. Writers such as Alphonse Toussenel, the Fourierist and anti-Semite, seized on Buffon's characterization of the cat when looking for a potent analogy for female sexuality. In his Zoologie passionnelle of 1855 his chapter on the cat is clearly a point-by-point, and to his mind salutary, exaggeration of Buffon's dissertation. Cats, Buffon had explained, were a necessary evil; without cats, homes would be overrun with mice. As Toussenel more frighteningly elaborated, moving from the domestic to

the social realm, the need for cats was like the need for prostitution. "Civilization may no more dispense with the cat than with prostitution," he less charitably continued, this "horrible vampire that it feeds with its flesh and blood and that it dares not do away with for fear of a worse evil."13

In Toussenel's logic of symbols, the cat stood for sexuality as the female cat stood for its species; the male was insignificant. Unusually, but instructively, the female was the means of degrading a species. "In all human and animal races," he claimed, "progress works through females." Women married up. Black women married white men, Jewish women married gentlemen, and European women married French men. Only cats, driven by lust, would seek satisfaction among less civilized members of their species. Female cats were interested only in free love. "The [female] cat is essentially antipathetic to marriage," Toussenel explained. "She accepts one, two, three lovers," and if denied by her domesticity the freedom to love, "she goes to reclaim that freedom in the wild."14

Like Buffon, Toussenel luridly insisted that cats keenly enjoyed sex, despite its acute attendant pain. "All is not rosy in these shameful affairs that denote the [female] cat," he seemed to warn. "The unfortunate creature confesses this rather strongly by her meows of pain that the brutal caresses of her lovers draw from her, and yet," Toussenel observed with keen interest, "it is not always she who runs in front of her tormenters."15

As with Buffon, the cat's sexuality was the element that prompted Toussenel's most extravagant phrases. For Toussenel, however, it also stood for prostitution. Toussenel insisted on the cat's kinship with women of leisure and pleasure: "An animal so keen on maintaining her appearance, so silky, so shiny, so eager for caresses, so ardent and responsive, so graceful and supple . . .; an animal who makes the night her day, and who shocks decent people with the noise of her orgies, can have only one single analogy in this world, and that analogy is of the feminine kind." Toussenel pressed his point. "Lazy and frivolous and spending entire days in contemplation and sleep, while pretending to be hunting mice.., incapable of the least effort when it comes to anything repugnant, but indefatigable when it is a matter of pleasure, of play, of

sex, lover of the night. Of whom are we writing, of the [female] cat or of the other?" he rhetorically asked.16

The cat's outré and irrepressible sexuality was noted by other observers, of course. "When the cat is in heat, its wild nature reveals itself in all its fullness in terrible cries," explained A. L. A. F(ée, professor of medicine at Strasbourg and member of the Académie impéiale de médecine.17 Earlier in the century the naturalist Georges Cuvier had described feline courtship as a battle: "The male and the female call each other with sharp high cries, approach each other distrustfully, satisfy their passion in the midst of mutual threats, and then separate, full of fear (each one of the other)," Larousse repeated in his Dictionnaire. He also explained (although Larousse was an advocate of cats, as we will see below) that the imperatives of sexual desire in cats were unmitigated by higher needs. Cats were not concerned with the preservation of the species: "But the wildness of their nature is not sweetened by this need, of which the conservation of life is merely the goal," he added. Cats were selfish in love.18

As we might expect, notions of feline behavior also informed the century's understanding of rabies. It was widely believed that cats were subject to the spontaneous generation of the disease. The Dictionnaire de médecine, for instance, explained that spontaneous rabies was possible in cats, wolves, and foxes, as well as in dogs. Only cats and dogs, however, could become diseased through sexual deprivation.19

But cases of feline rabies were very rare. Statistics from the Conseil d'hygiène publique for the years 1850-1876 offered a comparison of feline rabies with the incidence of the disease in dogs. Cats were blamed for twenty-three cases of human rabies, while during the same twenty-six years, 707 cases (still fewer than thirty per year) were the result of bites from dogs.20 More important, people's perceptions of the disease in cats seem to accord with some of the facts. Tardieu, for instance, public health officer and firm believer in the spontaneous generation of rabies, declared in his 1859 report to the Comité consultatif d'hygiène publique that "the animal whose bite caused rabies" was almost always the dog.21

People believed that few cases of rabies occurred among cats because many males were neutered and their sexual drive destroyed. Sexual deprivation was no longer a problem for the sex believed more suscep-

tible to the disease. But that admirable observer of animals and people in nineteenth-century Paris, the veterinarian Dr. Bourrel, pointed out that only one in ten male cats was neutered. And in fifteen years of practice, he had come across only one case of feline rabies in a male. Rather than suggesting that sexual desire in cats was unremarkable, however, Bourrel used the obvious exigent sexuality of female felines as an argument against the theory of the spontaneous generation of disease. "If [the urge for sex] can cause rabies, then cats who have not been neutered would often be struck by the disease, since the cat is, of all animals, the one in which these desires are the most pressing," he argued. He reminded his readers of Buffon's striking description of the cat in heat, repeating Buffon's phrases with a flourish. In such an animal, if in any, sexual frustration would explain the spontaneous generation of this disease, and veterinarians "would very often have to diagnose rabies in (female) cats." Yet they did not.22

Bourrel's unwelcome explanation of the rarity of feline rabies fit in with the conventional appreciation of the cat. Cats were hypersexual, independent, and asocial. Cats were devoted to the house, not the person, "The cat is attached to the house," Bourrel noted. "That he belongs to such and such an owner is of little importance to him, provided he is fed." The cat left the house rarely and then only when looking for sex, explained Bourrel. "Ordinarily, he does not stray from home. And it takes all the strength of sexual desire, which in {the cat} is so intense, to compel him to separate himself from his abode." Since the cat left its home only when pressed by desire, periodically, but not habitually, it had only occasional opportunities to catch the disease.23

The cat as icon of a sexuality pushed to the margins of bourgeois life was presented with disturbing effect by Edouard Manet in his 1863 painting Olympia. As T.J. Clark argues, Manet transformed the conventional nude into a portrait of a working-class prostitute while signaling its prototype with a replacement of signs. Among these signs, the cat figured significantly. Olympia revealed its derivation from Titian's Venus of Urbino, Clark points out: "The pose of the nude is essentially the same and the nude's accessories seem to be chosen as the modem forms of their Renaissance prototypes; orchid in place of roses, cat for

dog, negress and flowers instead of servants bringing dresses from a distant cassone." Clearly part of what made critics judge this painting obscene is the black cat arching its tail at Olympia's feet. Along with Olympia's oversized hands and her dark skin, the cat signaled, in the shorthand of criticism, the painting's distinctive motifs. Cham's caricature of 14 May 1865 in Le Charivari offered a good example of this figuration. His "Manet, la naissance du petit ébéniste" exaggerated the size of the cat particularly by elongating the tail and emphasized Olympia's hands by darkening them. Le Journal amusant also played with the figure of the black cat in its review of the painting.24

Manet echoed Baudelaire's themes. The darkness of Olympia's skin, the evocation of perfume in the bouquet, and the startling image of the cat, of course, rearranged the central and ancillary metaphors of "The Cat," quoted above.25 A similar image in Zola's Thérèse Raquin (1 867) reflected the murderous sexuality of the exotic Thérése in the petitbourgeois family's cat.26

The cat in nineteenth-century culture was distinctly not bourgeois. "If the Parisian cat could choose his own master, it would be the artisan rather than the rich bourgeois he would give himself to," suggested F&. "Admitted to the honors of the shop or to the pleasures of the salon, he buys these advantages with ail the dignity of his sex," Fée continued, "he loses, with the instinct for love, [the instinct] for hunting; and rats and mice might dance round him with impunity, having nothing to fear."27 The cat was like Thérèse, the bourgeois Raquin's half-Creole relative, who explained to Laurent after he had reawakened her sexuality, "They have so smothered me in their middle-class refinement that I don't know how there can be any blood left in my veins."28

But neither was the cat working-class, within the associative terms of per. keeping culture. The cat was linked rather with bohemia, a social space only indirectly concerned with class: intellectuals were elitist, and their affiliation was to the ancien régime's republic of letters rather than to a supposedly Philistine class.29 "The philosophes of the last century affirmed, on good authority no doubt, that a pronounced taste for cats in certain people was an indication of superior merit," Larousse noted approvingly. "Witness those of our contemporaries whose affection for

cats is a matter of notoriety, Théophile Gautier, Albéric Second, Léon Gozlan, Champfleury, Théodore Barrière, Paul de Kock, and several others."30

The companionship of a like-minded animal became a trope of intellectuals, the cat a sign for the literary life, a signature. Jules Barbey d'Aurévilly, for example, had a cat named Démonette, "or rather Des-démone—Démonette to close friends," which was given to him in 1884 by Madame Constantin Paul, the famous doctor's wife. The cat "would hardly ever leave the office of her master," his literary executor explained with great exactness, "settling herself comfortably on blank paper or, better yet, when those large pages of foolscap—on which he wrote his articles and novels—were filled with lines, fresh with ink, then, with so many switches of the tail would augment them with cross-hatching!"31

Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve also had a notable feline companion, Polémon, a magnificent tabby, who had the freedom of his master's office. A friend later described him, typically, lounging lazily and deliberately among Sainte-Beuve's mountain of books. Gautier also described the intellectual's ideal companions who purred and performed their toilette as a pleasing background to intellectual work but always discreetly, "as if afraid of distracting or being annoying."32

In the realm of the imagination where the myth of the intellectual's life was invented, the cat described the social space to which it was restricted.33 Looking backward from the twentieth century, we see the cat lazing about the intellectual's study as part of a harmless cliché that described the intellectual and artistic life. But in the nineteenth century the cat intensified, for a caste in formation, its salutary unconventionality. Cats were homologous to intellectuals, their writings suggested. Chateaubriand explained, "What I like about the cat is his character, independent and almost heartless, which prevents him from attaching himself to anyone . . .. The cat lives alone, he has no need of society," Chateaubriand reminded his audience. The cat did what it wanted, obeyed only when it wanted to, and was admirably free of social conventions. Chateaubriand clearly admired "that indifference with which he passes from salon to gutter." Distinctly unlike dogs, the cat was never obsequious. When it socialized, it sought only its own physical pleasure: "one strokes him, he raises his back in pleasure; but it is a physical

pleasure that he experiences, and not, as with the dog, an inane saris-faction in loving and being faithful to a master who thanks him with a kick."34

Like the intellectual, the cat held in limbo, so to speak, values forced to the margins of bourgeois life.35 The supreme individualism of genius that Chateaubriand's comment on the cat described is an instance of this displacement. So too was the liberty and integrity of an artist who refused to be sold. The cat defined the way one should behave, the writing of intellectual cat lovers suggested. "To gain the esteem of a cat is a difficult thing," explained Gautier. "It's an animal.., who will not carry affection to the point of foolishness," he stressed. The cat would be your friend, "if you are worthy [of his friendship]," but never your slave. The cat maintained his "free will," despite the demands of friendship "and will not do anything for you that he considers unreasonable," he added. In the cat, affection was not compromised by convention. As Jules Michelet explained, cats owned people, not the other way around. "I have had at least one hundred cats or rather, as Michelet said, one hundred cats have owned me," noted Paul Morand when the trope was already a cliché.36

Cats refused to accept the constraints of bourgeois life, in the self-reflexive fictions, perhaps, of intellectuals. Catulle Mendès, for instance, had a cat that killed itself, he mournfully suspected, after having been neutered to make him a more agreeable pet. The cat, Mime, was beautiful, but he gave off a very strong odor. Taken to be neutered, he returned depressed: "Mime fell into a depression blacker than his beautiful velvet coat," we learn. Catulle Mendès lived on the fifth floor, and the cat was in the habit of walking along the ledge below the windows. One morning, Mime "deliberately" threw himself off the ledge and onto the street, where he broke his back. "I have the distinct impression that Mime committed suicide, " Mendès asserted.37

Significantly, cats rarely allowed themselves to be victims of vivisection. "[A cat] escapes the knife of those experimenters who find the dog, the rabbit, the pigeon far easier to sacrifice," explained Fée. Cats were constitutionally difficult to shape to utilitarian ends. "The cat alone [of all animals] cannot be trained. He is not at all malleable, either physically or psychologically. He remains obstinately himself, and therein is his

dignity."38 In another echo of Baudelaire, contemporaries believed that cats could be appreciated solely for their beauty, like art for art's sake. Catulle Mendès, for example, first owned falcons and other birds and then turned to dogs and cats, "the latter which he loved solely for their beauty," we are told.39

To understand the cat, wrote Champfleury in an often quoted phrase, "one must be a woman or a poet." The nineteenth century's appreciation of the cat rested for a long time on these two adjunct ideals contained uneasily within bourgeois culture. Within the logic of petkeeping, cats were feminine, philosophical, or both. "He is reserved, a philosophe, closed up within himself," suggested Henri Lautard, a Belle Epoque master at restating the obvious who also traced an affinity between Baudelaire and the cat. Both liked perfume. "Baudelaire loved cats who like himself were such lovers of perfume that a whiff of valerian [garden heliotrope] would throw them into a kind of epileptic fit," he wrote in a frenzy of clichés. Lautard was echoing Larousse who had explained in his Dictionnaire that perfume so strongly affected cats that its scent sent them into transports of pleasure.40

Cats and courtesans shared a luxurious sexuality, a fantastic sensuality, rather, that was carefully maintained outside the home. "He hides everything that should be hidden," wrote Lautard admiringly about the cat. "At certain times, he will throw off surveillance and escape from the house . . .. But if he cries his love affairs on the rooftops or in the street, it is only during the night that he does so, he never lets us see them," he explained in his work on feline psychology.41 A utopia of irrepressible sexuality, the world represented by cats and prostitutes in the bourgeois imagination was like the "separate universe," in Pierre Bourdieu's phrase, that intellectuals carved out of bourgeois life. The excessively independent cat lived rather as the intellectual did, an existence of bourgeois individualism freed from the constraints of modern life. In the fictional world of creativity, both set themselves outside of family, society, and state, refusing to be dishonored, as Flaubert felt he would he, by any sense of belonging. The impulse to "affirm oneself as an artist with neither ties nor roots," as Bourdieu reads Flaubert, "'with no boots to lick; homeless, faithless, and lawless'" as Jean-Paul Sartre later expressed the modernist myth, found its animal counterpart in the cat.42

This creature intensified decidedly discordant themes within bourgeois culture. Unlike the dog, whose qualities lent themselves to embourgeoisement, the cat seemed resolutely set against incorporation into the mainstream of bourgeois life. Writers often drew unfavorable comparisons between the irascible autonomy of the cat and the fidelity, sociability, and malleability of the dog. "The cat and the dog bear absolutely no resemblance to each other, either in physical being or in educability," Fée said. The dog was our friend, the cat our guest. The cat was useful for chasing mice. But, Fée warned, "do not attribute to him any will to help us, he merely gives in to his instinct to hunt." It would be useless to ask anything more of a cat; "no one has been able to force the cat to render us the least service."43 Toussenel, predictably, expressed the familiar wisdom with deliberate hostility. "The female cat attaches herself to the dwelling and not to the people who live there, proof of her ingratitude and the aridity of her heart," he concluded. A cat thought only of its comfort, unlike the dog, he insisted, "who attaches himself only to people and who is indifferent to misery provided he is sharing it with the objects of his affections."44

Unexpectedly, these same disagreeable feline qualifies ensured cats' safety from the disease that dogs were so prone to catch. In his discussion of rabies, the persistently logical Bourrel contrasted admirable canine qualities to feline ones: the dog is a social animal. He is devoted to his master, "to the hand that feeds him," and wherever that master may go, here or there, the dog is happy, "provided he can sleep at the feet of his master, watch over his sleep, and defend him against enemies." A dog's sociability also led it to "fraternize with other dogs." The dog had many more opportunities than cats had to contract the disease.45

It is a mark of the strength of these themes that attempts to "rehabilitate" the cat took the form of making a cat seem to behave like a dog. Stories that featured feline fidelity, for instance, began to appear sporadically in the bulletin of the Parisian Société protectrice des animaux in the mid-1860s. In a single bulletin of z864, Mme Addle Favre attempted a "rehabilitation of the cat" on page 313 and M. Fournier "a new rehabilitation of the cat" on page 353. In the same year, in the July issue, the society featured another brief story on the "attachment cats are capable of feeling toward us." Cats, like dogs, these stories detailed,

could be faithful beyond the grave. An attempted feline suicide, notably, was reported in 1865 under the heading, "Singular attachment of a cat for his master." In this story that purported to be true, observers narrowly prevented a cat whose master had just killed himself from doing the same. Fée, whose work the animal protection society reprinted and publicized in many formats, agreed: "The cat is not loving. However, if one succeeds in gaining his affection, which is not a very easy thing to do," he warned, "he may attach himself to his masters so passionately that sometimes he will die of grief from having lost them."46

The theme of feline fidelity was also developed with telling effect outside the bounds of the animal protection society. In children's literature, for instance, we find a polemical story, "Jenny and Minnie," appearing in French about this time. "Jenny and Minnie" tells of the friendship between a kitten, Minnie, and an abused orphan, Jennie. Jennie dies of her mistreatment, of course, and as we might guess Minnie dies on Jenny's grave.47 So the cat was capable of expressing affection, even if only exceptionally. In a work of animal protection propaganda, Marie-Félicie Testas reluctantly admitted the possibility: "It is said, and truthfully, that the cat does not love his master the way a dog does. He appears to love only his food and lodging. The master leaves and the cat remains. Nevertheless, it is true that there are cats who recognize their master and who love them. I have known one or two of this kind."48 Ernest Renan was more generous, suggesting that although cats were devoted to the home, they were capable at the same time of affection for people. "With respect to the cat, I believe that there is, indeed, a bit of egoism in him," admitted that positivist admirer of cats. "He likes his comfort above all and attaches himself more to the house than to persons. We have had here, however, striking proofs of that ability cats have to attach themselves to people." Renan warned, collapsing categories with anti-Semitic effect, "Do not charge that animal so much with the sins of Israel.49

Occasionally and pointedly a writer might applaud feminine cats for exhibiting masculine canine behavior. Female cats, for instance, could practice "fraternité" The animal protection society printed a letter in its March x873 bulletin from a M. Heine, "Observation de fraternité comparée." He called readers' attention to "the story of twin cats who

had their kittens the same day and in the same basket and who share their affectionate cares."50

Larousse, who directly engaged the arguments of Buffon and Toussenel in a premature effort to rehabilitate the cat in bourgeois culture, insisted that the cat could love as the dog did. "Biographers of cats, from the great naturalist [Buffon] to the very witty Toussenel," he explained, "have shown themselves severe on our heroes . . ., and it is a kind of rehabilitation that we are attempting here." Toward this end he whimsically printed a letter to his daughter from a kitten who claimed to be a good pet. The letter ended with the assurance of canine affection: "Which leads me to say to you that I write like a cat but I love like a dog."51

Alexandre Dumas, also, had a cat, Mysouff, whom he loved for its canine behavior. As he explained, "that cat missed his vocation, he should have been born a dog." The Dumas family lived on the rue de l'Ouest. Each day Mysouff walked Dumas to work as far as the rue de Vaugirard. On the writer's return, his canine cat would greet Dumas. "He would jump up on my knees as if he were a dog, then run off and return, then take the road home, returning a last time at a gallop," we are told with generous detail,52

A defense of the cat that attempted to neutralize feline perfidy by exposing its logic was also sketched out in the 1860s. The "fausseté" of the cat that Buffon had criticized was accidental, merely the result of artificial circumstances, a M. Boitard claimed. Forced to live in close quarters with its worst enemy, the dog, the cat had developed strategies of circumvention. "His natural distrust increased, necessarily, and it is probably to this that we must attribute what Buffon calls his treachery, his insidious gait," Boitard suggested. "He has kept that part of his independence to assure his existence in that position in which we have placed him," he also insisted, with Larousse's approbation,53 Somewhat paradoxically Fée also tried to distance feline behavior from the morally charged universe to which it had been attached. The cat was not really traitorous when he scratched the hand that caressed him, Fée insisted. The impulse to scratch was a reflex, an instinct, over which he had no control. "When he submits to our caressing, it excites him, and when he appears to enjoy it the most, he will open his claws and scratch the

hand that is stroking him. It is this that makes people call him a traitor," he explained. "To my mind, we must understand the thing in a different way and not attribute to treachery what is a simple effect of the nervous system." Furthermore, cat qualities in themselves could be appealing. "For people, in fact, the cat is a friend to talk to and converse with at our ease," Larousse suggested,54

By the 1880s, pet owners needed little convincing that cats were good pets. The popularity of cats grew undeniably from the last decades of the nineteenth century until the First World War. Cats continue as a presence in mass culture and today in France are almost as numerous as dogs. According to Theodore Zeldin, in 1983 seven million dogs cohabited officially with six million cats. Unofficial figures put the totals at nine million dogs and seven million cats.55

Even before the Belle Epoque, cats had supporters among ordinary people who were neither intellectual nor sexually unconventional. During the Paris Commune, when people had to eat or destroy their pets, some saved their cats.56 And in the early days of the siege of Paris, when authorities attempted to save dogs from destruction, cats found supporters also. As was explained in the animal protection society's bulletin of 1871, "It took very strong needs to push anyone to destroy that four-footed friend; more than one poor devil shared his last crust of bread with him and in one club when the motion was made to sacrifice, ruthlessly, all of the useless mouths, there was a general revolt among the tender-hearted." The reporter was referring to dogs but a small effort was made, less predictably, on behalf of cats. "Several good souls spoke on behalf of cats also, who certainly have their merits, in spite of the lies malicious people make up about them," the writer added.57

During the late 1870s the Société protectrice des animaux grew more active in its defense of cats. The 1 866 index to the bulletins of that year cites no listings of reports on cats; there were twenty in 1876. These included plain entries entitled "cats" as well as more descriptive ones such as "abandoned," "plans for a shelter," "plans for a pound," "rescued," "bad treatment toward," and other issues that signaled, significantly, cats' canine susceptibilities. In 1873 only six articles on cats were listed under four headings: "cruelties toward," "rescued," "acts of fraternity," and "nursed by a dog"; on dogs, thirty-two headings were

needed to organize eighty-one separate entries. Perhaps as important as the increase in articles about cats is a shift in emphasis in the late 1870s from sporadic defenses of the cat's personality and general protection concerns to mainstream pet protection issues. In the 1860s the society was still concerned, for example, with preventing cats from being hunted for their coats in Paris, and with demonstrating that a cat could be loyal. In the late 1870s the dominant eat-related issue was the refuge.58

The appearance of cat shows in Paris and an interest in breeding marks an even more significant abandonment of the conventional assessment of the cat. Cat shows, like dog shows earlier, were based on British models. Harriet Rirvo points out in her book on British attitudes toward animals that the first cat show was held in 1871 at the Crystal Palace. And specialist cat clubs "began to spring up at the turn of the century."59 As Henri Lautard remarked in 1909, cat shows were held yearly in London, adding, somewhat defensively, that Parisians also showed their cats. "We might also note.., that Paris has also had several fine cat shows during these last few years."60

The French interest in cat breeds began in the late 1870s. Robert Delort explains that Abyssinians were brought from Africa in 1869 and first appeared in writings about cats in 1874. Siamese cats, smuggled into Britain in the 1870s and 1880s, were introduced to France by the French ambassador to Siam, Auguste Pavie. In 1885 he presented one to the Jardin des plantes.61 In 1869, however, A. E. Brehm, "one of the high priests of zoologie," as Delort points out, had listed only eight breeds of cats in La Vie des animaux illustrée: "the Angora, the Manx, the Chinese cat, and five other varieties (the Chartreuse, the Persian, the Rumanian, the red cat of Tobolsk, and the red and blue cat of the Cape)." The same edition had described x95 breeds of dogs. Larousse in the 1860s knew only four varieties of domesticated cats: "the domestic tiger, the Chartreuse, the Spanish cat, [and] the Angora."62

Cat shows set the standards for breeds. But unlike dogs, where size, gait, shape, even purported function, set one type off from another, cat types differed mainly in color and length of coat.63 As Lestrange explained in 1937, when the cat show was a set practice, "Cat shows have made us aware of the very special characteristics of the genre 'cat,' according to the color of the coat, which goes from ermine white to black

velvet, passing through all the shapes of gray, yellow, and red without counting those of tortoise shell or tabby." The determined exoticism of breeds however—"chats de Perse, de Birmanie, de Siam, chats rouges de Tobolsk, chats nègres de Gambie, chats cypriotes, chats du Canada," as Lestrange detailed64 —testifies to the impulse to introduce the safely exotic into everyday life, a belated echo of canine structures in catkeeping practice.

Alain Corbin suggests that the cleanliness of the cat played a significant role in its new popularity. "Yet here, too, Pasteur's discoveries changed behavior," he explains in his discussion of the "animal de tendresse" in The History of Private Life, the fear of germs "worked in favor of the house cat, which smelled less than its rival and was reputed to take better care of itself."65 Certainly, the only consistently appealing feline trait, reluctantly conceded by the most hostile of commentators, was its obsessive self-care. Florent Prévost, in one of the few pet-care books to discuss cats, explained that though cats were disagreeably faithful to a house and not to a person, they were, at least, clean. Testas, in the Contes de l'asile du quai d'Anjou agreed: "The cat is not lacking in certain qualities. He is clean, glossy, one often notices him performing his toilette. Never has dirt of any kind been seen on his coat.'"66

Even those who celebrated canine qualities of fidelity and affect admitted that the dog's standards of hygiene were low. The Parisian animal protection society made this point in a report on "The dog, the premier domestic animal" published in its early bulletin of x857. "The feelings he develops for us set him above all others. He loves us and it is because of this, principally, that we are touched." However, left to its own devices, the dog was a glutton, ruled by his stomach. His choice of food was often disgusting: the dog would eat the droppings of other animals—"so lacking in refinement when it comes to food." And the dog was dirty. Unlike the cat, the dog cared little about his appearance, apparently as happy when covered with dirt as when "combed, washed, and perfumed."67

The history of the cat, however, addresses the history of the nineteenth century at another level of meaning, one that this book seeks to enclose. The impulse to categorize shaped both scientific and social

representations of modern life. Shifting configurations of human and animal, outsider and insider, being and nonbeing, were described at many levels of nineteenth-century culture. Among ordinary people the attempt to catalog concerned primarily the language of class. To speak of the popularization of scientific ideas is to grasp only one of the directions that shaped bourgeois culture, a civilization marked by multiples of self-definition. Like the corporate world it replaced, Pierre Bourdieu reminds us, the universe of class was an attempt, mediated by power, to describe—codify and fix—"a state of the social structure."68 We could say modernity.

In everyday life the shaping of nineteenth-century modernism was effected in petkeeping culture. Around the dog were clustered qualities that spoke to contemporary feelings of fragmentation and isolation. The faithful and affective dog commented pointedly on the failures of individualism, the perceived lack of community in urban life. At the same time, the dog fixed modernity in notions of class. Bourgeois dogs, contemporaries insisted self-consciously, were distinctly unlike working-class animals. The aseptic pet, denatured in the imagination of pet owners, worked to distinguish culture, or bourgeois ideas of civilization, from nature, a sometimes undifferentiated confusion of categories—animals and the working class, women and the poor, sexuality and violence. It helped describe the norms of everyday life, whose costs were registered in disease.

Natural history per se was less important in petkeeping culture than the bourgeoisie's own understanding of its history. The fidelity of the dog, as well as its opposite value, the perfidy of the cat, were qualities borrowed from, or, rather, renewed with pointed reference to, pre-Enlightenment Europe. Here was a moral zoology that ordered the hierarchy of petkeeping. For Larousse, writing in the 1860s about cats, moral values were intrinsic to species. "First of all, to get a fix on the intrinsic value of a species, a value that is as much moral as physical, we consult proverbs," he noted with true lexicological flair.69

The role of the imagination in shaping bourgeois culture was also apparent in the development of the home aquarium. The impulse to collect exotica—in the aquarium, deliberately alienated natural objects—

was paralleled in the development of breeds. Invented histories of other times and places were fixed in types of dogs. Later, Asian and African cats would appeal to the same interest.

The Parisian Société protectrice des animaux shared the view that animals embodied values. The marquess de Montcalm, for example, vice-president of the Parisian society in 1860, could refer to animals as models for human behavior.70 A more sophisticated view was expressed by Oscar Honoré in Le Coeur des bêtes, which a committee of the society's officers praised in 1861. He discussed the relationship of human beings to animals in terms of evolution. More specifically, he posited a moral Lamarckism. Humanity, Honoré argued, had become too complicated to understand: "too complete, too complex to be in itself, and directly, a profitable subject of study. Modified by education," he explained, "disguised by the changing glaze of diverse civilizations, protean human passions.., sometimes suggest the image of chaos." Animals, however, like children, were easier to read. They expressed human qualities in a simpler form: "Like a child, the animal is without shame or artifice, he opens his heart like a book, where we recover in each line a trait from the human character." The function of zoology was the explication of an otherwise baffling humankind. "Would not the almost impossible analysis of human passions find precious instruction in the observation of these so much simpler combinations of ideas and feelings that the animal presents?" he asked.71

Some fifteen years later Sociétaires continued to suggest not only that the function of zoology was moral but that human beings were its determining subject. "What do these anatomical descriptions, these measurements, these analyses, these experiments tell us about the true character of an animal, about those traits that make it a distinct being?" the author of an 1875 article on "la zoologie morale" asked. "Nothing," he answered. Dissected, all animals looked alike. In looking at animals, he suggested astutely, human beings were looking for themselves: "Now, as we know things only by the impression they make on us, it is not in the animal we must search, but in ourselves."72

By the end of the nineteenth century, however, canine and feline values had lost the power to reassure or disturb. The excessive individualism and sexuality of the cat, for instance, were no longer sources of

anxiety for the bourgeoisie. Petkeeping grew formulaic, as the participants set the broad strokes of bourgeois culture itself. By the First World War people knew about the care of pets, just as they intuited the conventions of bourgeois life; class was an object, knowable and known.

The cat's absorption within bourgeois culture signals not merely the neutralization of the qualities it represented, but the abandonment in the late nineteenth century of organic metaphors for modernity. Between the,1850s and 1880s, scientific and ordinary thinking alike were still strongly moored to natural models. Nature could still speak to culture, at least negatively. By the First World War, however, the ambiguities of bourgeois culture had found other, sadder, resolutions. In art and technology, in likening human beings to machines, modernism failed.