PART ONE—

EARLY DAYS

From Film Quarterly 's first issue in Fall 1958 through the Spring 1961 issue, Albert Johnson was the journal's assistant editor, the only one it has ever had. Thereafter he became a member of the editorial board, on which he is active to this day. This is by far the longest service on the board that anyone has had: thirty-seven years. Johnson's long career as a teacher and his participation in film festivals and colloquia around the globe have enriched the journal many times over, particularly as Johnson is the only member to have seen many of the films that contributors have reviewed or discussed in articles submitted to the journal's editorial board. His encyclopedic knowledge of the entire work of a staggering number of filmmakers has aided the board in its deliberations and, through the editor, helped contributors avoid errors and expand the scope and applicability of their arguments.

Johnson's article "Beige, Brown, or Black" (Fall 1959) concerns the treatment of blacks in Hollywood film in the 1950s but begins with a brief summary of the late 1940s, "a brief period of sociological experiment in American film." Several works dealt specifically with "problems involving Negro characters." These included Home of the Brave, Pinky, Lost Boundaries , and No Way Out . Of the 1950s generally, he notes that American drama has suffered from a lack of Negro playwrights and screenwriters able to present their characters "in authentic and dramatically informative situations." In "The Negro in American Films: Some Recent Works," a seventeen-page article that appeared in Fall 1965, Johnson drew attention to, among other issues, later Sidney Poitier films and what might be called the Diahann Carroll–Diana Sands era, literally a pivotal time for African American characters—and players—in film.

Thirty-two years after "Beige, Brown, or Black," in the Winter 1990–91 and Spring 1991 issues, Johnson published a two-part article entitled "Moods Indigo: A Long View." Filling a gap in film scholarship, this article became an instant classic, remarkable for its intellectual acuity, breadth and firmness of

grasp, and subtlety and grace of writing style. Johnson's opinions are also sometimes controversial—for instance, his reservations about some aspects of Spike Lee's work—but this controversy too provides impetus for critical thought. Comprising thirty pages of Film Quarterly 's then relatively new 8 1/2-by-11 format, "Moods Indigo" already constitutes a short book. Indeed, Johnson's colleagues—on Film Quarterly and elsewhere—urged him to gather the articles mentioned, along with his two-part article on Vincente Minnelli and his writings on the musical (including reviews of West Side Story and The Young Girls of Rochefort ), into the confines of a book.

Founding editor Ernest Callenbach's twenty-two-page article "Recent Film Writing: A Survey" (Spring 1971) appeared in the journal's fourteenth year. Of course, Film Quarterly had published a number of book reviews over the years. Some issues had five book reviews; most had two or three; quite a few had none at all. Callenbach wrote many of the reviews; in the Spring 1967 issue, for instance, he reviewed A World on Film by Stanley Kauffmann and Josef von Sternberg by Herman G. Weinberg. But there were other reviewers also, such as Hugh Kenner (author of books on Ezra Pound, Buckminster Fuller, and Chuck Jones, among others), who reviewed One Reel a Week , accounts by filmmakers of cinema's early days; Rudi Blesch's biography of Keaton; and other books.

But "Recent Film Writing" was something new. Its immediate impetus was a quantum leap in the number of film books published. Callenbach's article was divided between attempting to understand this phenomenon and trying to catch up with it.

There have been a tremendous number of film books published in the past year or so, although the output relative to that of the established fields like English or sociology is still modest. Once, we could have the easy feeling that we could read everything that came out. We now face a situation like that in older fields, where specialization is forced on us whether we like it or not: nobody has the time to read all the books that are appearing. I regret this, personally speaking, because it means a kind of fragmentation and dispersion of intellectual activity, but it seems to be inevitable whenever any subject is attacked by large numbers of people.

It may be stretching a point, but one might link Callenbach's lament to the early writings of Marx, in which the division of labor is seen as a kind of Original Sin, which occasions the fragmentation not only of fields of knowledge, but also of the self.

Callenbach's article in its complete form (it has been edited for this anthology) lists sixty-six books and discusses six additional books, in greater depth

than the other books, in the long "Criticism" section (reproduced here). With this number of books, the author felt it necessary to devise a system of categories, which was no more perhaps than a pragmatic breakdown according to the topics they treated. The nine sections of the article covered anthologies, interviews, how-to-do-it books, scripts, director studies, histories, reference books, miscellaneous, and criticism. The first eight sections—one to three pages each—comprise ten pages of the article; the "Criticism" section comprises thirteen pages.

These categories and the article itself are important as the precursor, indeed the actual beginning, of what eventually became a Film Quarterly regular feature, if not an institution: the annual book review issue, which is now the summer issue of each year. Tracing briefly the development of these surveys or round-ups, as they came to be called, might be illuminating. For one thing, Callenbach's article marked the first and last time that a survey of the year's film books was done by a single person; many hands have accomplished all later book issues. Regular journal features rarely spring up all at once, and the annual book issue is no exception. It took several years before the survey was established as an annual summer event. Moreover, the book issue has never quite congealed into a fixed entity: its format and categories have changed over time. Since 1984, for instance, the summer book issue has more often than not spilled over into the fall issue also.

There was no book issue in 1973, but there has been one in every year since. Nearly all issues since 1975 have referred to the book issue—on the cover and inside—as a "round-up": "Another Round-up at the FQ Corral" or "Another Giant Film Book Round-up." This became more or less standardized in 1985 as "Annual Film Quarterly Book Round-up." This metaphor refers not to the actual West, of course, but to the Western genre. Taken literally, the term suggests a correspondence between a gathering of film books and a gathering of cattle into a herd. One can imagine individualistic authors who might not enjoy that metaphor. ("Don't Fence Me In" might be their anthem.) For perhaps a larger number of writers, the prospect of a review, even a lackluster one, is a promotional opportunity not lightly cast aside. Accepting an uncertain fate—or pessimistic about the whole matter—"I'm a-headin' for the last round-up" might be their lament of choice.

One might speculate also about the lingering doubt editors and board members might have over how readers react to the perpetually spilling-over book review coverage. In this event, the Western terminology and tongue-in-cheek Paul Bunyan hyperbole—"Gargantuan! Colossal! Stupendous!"—may be attempts to overcome the long stretches of extended book reviews, short notes, and annotations. Matthew Arnold said that religion had "lighted up" morality, meaning—it has been supposed—that the burdens of morality may be carried more easily

with the aid of the light, sound, music, and other consolations of religious experience. So perhaps with the phraseology of hoopla that dominates the covers and insides of book issues. Very few complaints have been received about the book issues, however, and much praise. Book reviews provide abundant materials for conversations about film—as much as interviews, articles, and film reviews—which is presumably a principal reason people read film journals.

Equally important for the future of Film Quarterly are Callenbach's remarks in the long "Criticism" section of the piece. Sometimes explicitly, sometimes between the lines, he considers where film criticism—and, implicitly, Film Quarterly —has been and where it is going/should go. His theme is stated in the section's first paragraph:

It seems to me that we now have critical resources that greatly surpass those of a decade ago; our general-audience magazines, in particular, are now immensely better served, and the critical books which have flowed from the journalistic work seem to me to constitute a remarkable outpouring of critical energy, knowledge, and intelligence. Many new and good critics continue to develop within the specialized film journals. As a congenital pessimist, I choke to say it, but we have never had it so good.

That general magazines are now "immensely better served" surely refers to several well-known critics, but it refers especially perhaps to Pauline Kael. From 1961 to 1965 Kael contributed a considerable amount of material to Film Quarterly , including her best, most amusing blasts at the flat-footed pretensions of Hollywood filmmaking; her contributions to "Films of the Quarter," a regular FQ feature for some years; and her notorious article "Circles and Squares." After writing for Vogue and the New Republic , Kael became a permanent regular film critic at The New Yorker .

What Callenbach seems to be thinking through in the "Criticism" section is the question of the future, specifically the weekly critical format of the general magazines versus the ideas, including theoretical ones, of a younger generation (or half generation). This is not an "either/or" in relation to ultimate values, but a question of where the future lies, especially for a journal the size of Film Quarterly , its mission at least partly defined by its university-sponsored status. His conclusion is perhaps implicit in his remarks on method at the outset: "Nevertheless, speaking more as an editor than a critic, I would like . . . to make some sense of what has been happening in film criticism recently on the level of ideas."

He cites the ideational limits of weekly reviewing—"You can imply theoretical matters, but in the general press you had better be sure they don't get too heavy." Also, each review has to be freestanding; one can't expect the

reader to keep a connected argument in mind from one week to the next. A review done by a skilled writer is a special-purpose item that cannot easily be put to other purposes. Finally, especially with foreign films now having a hard time entering the U.S. market, there are not necessarily films worthy to review every week. Regarding Kael's then recent collection Going Steady , he says that of seventy-six films discussed, only ten seem to matter to her as films.

On the other side, Callenbach notes:

The theorist must attempt to "rise above" individual cases, to arrive at large generalizations. . . . Theorizing can be a pleasure quite in itself, of course, just as playful activity. . . . Criticism needs ideas, however, and I would like to spell out some of the reasons, perhaps a bit painfully. Criticism cannot in fact rely upon "taste" alone; every good critic's way of thinking rests upon a pattern of assumptions, aesthetic and social; and it employs a constellation of terms appropriate to those assumptions. The act of "criticism," in essence, as opposed to the mere opinion-mongering of most of the daily press, is the application of such terms to the realities of a given film: describing it, analyzing it, evaluating it, and in the process also refining the terms and assumptions.

Nobody would enjoy this process if carried out in an obvious and mechanical way: "there are benefits to be gained by carrying it out with more intellectual elegance and determination than are customary among our film critics." He also notes:

Assumptions and terms reasonably suitable for dealing with conventional narrative fictions have been around for a long time. Basically "realist" in tenor, these ideas have never applied very well to non-narrative and expressionist forms, especially experimental ones; the neglect of experimental film by critics has been due at least as much to practical embarrassment at this as to the inaccessibility or low quality of the films.

Callenbach concludes this section of his article with a brief mention of a filmmaker-theorist such as Eisenstein and, with qualifications, Godard. "But aside from such rare exceptions, we will get our ideas about what is going on from critics, or we will not get them at all. It would be a good thing if our critics could, over the next couple of years, come up with some new and coherent ones."

Beige, Brown, or Black

Albert Johnson

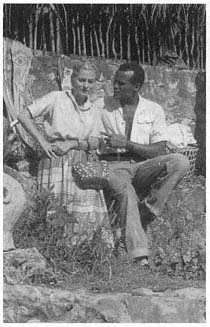

Tropical dilemma: Joan Fontaine and

Harry Belafonte in Island in the Sun .

Vol. 13, no. 1 (Fall 1959): 38–43.

The late nineteen-forties, a brief period of sociological experimentation in American film-making, contained several works dealing specifically with problems involving Negro characters. Such films as Home of the Brave, Pinky, Lost Boundaries , and No Way Out were particularly memorable because they attempted to portray the Negro in a predominantly white environment; as a figure of dramatic importance, the Negro has long been overlooked or carefully avoided on the screen, chiefly because of the refusal of Southern theater exhibitors to book such films. The U.S. Motion Picture Code's rule regarding the depiction of Negro characters, notoriously outdated, has only managed to keep in effect a rigidly stereotyped view of a race whose economic and intellectual status has risen to such a degree since 1919 that one tends to look upon most Negro screen actors as creatures speaking the language of closet-drama.

American drama has suffered from a lack of Negro playwrights (not to mention Negro screen writers) who are able to present their characters in authentic and dramatically informative situations, for certainly few racial groups in this country flourish so actively on a level of melodrama, except perhaps the Puerto Ricans in New York, and yet, the two most successful stage works about contemporary Negro life are based upon the same rather bland premise: the sudden acquisition of a large sum of money by a middle-class family (Anna Lucasta and A Raisin in the Sun ). These plays succeed because they honestly develop character in an all-Negro milieu on a nonstereotyped basis—they reveal the Negro to audiences with the same sympathy and insight with which Sean O'Casey exhibited the Irish in Juno and the Paycock . So far, so good, but what has happened in the American cinema since the forties regarding the plight of the Negro?

First of all, the Supreme Court decisions regarding integration of Southern schools, in 1954, once more brought the entire question of Negro-

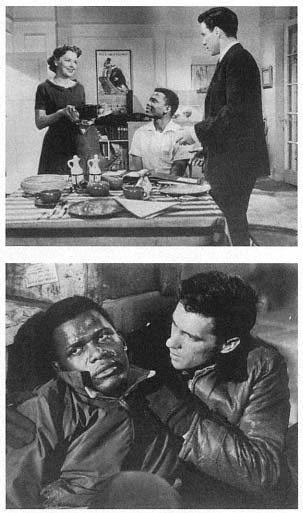

white relationships to the attention of the world. The incidents ensuing from this historic decree have yet to be conveyed in either stage or screen terms, and apparently, no one is courageous enough to do anything about it, but, at any rate, the Arkansas affair stirred interest in the Negro race once more as a focus for drama. Secondly, it was apparently decided by various Hollywood producers that a gradual succession of films about Negro-white relationships would have a beneficial effect upon box-office returns and audiences as well. The first of these films, Edge of the City (1956), is the most satisfactory because it is the least pretentious. The performance by Sidney Poitier (the Negro actor whose career has most benefited by the renaissance of the color theme) was completely authentic, but true to the film code, any hint of successful integration must be concluded by death, usually in some particularly gory fashion, and so Poitier gets it in the back with a docker's bale-hook. The most constructive contribution of Edge of the City to film history is one sequence in which Poitier talks philosophically to his white friend, using language that rings so truthfully and refreshingly in the ears that one suddenly realizes the tremendous damage that has been nurtured through the years because of Hollywood's perpetuation of the dialect-myth. The film was praised for its honesty, but its conclusion was disturbing; audiences wanted to know why the Negro had to be killed in order for the hero to achieve self-respect.

Strangely enough, this promising beginning of a revival of American cinematic interest in interracial relationships took a drastic turn with Darryl F. Zanuck's lavish production of Island in the Sun (1957). The focus changed from concern for an ordinary friendship between men of different racial backgrounds to the theme of miscegenation, considered to be, in Hollywoodian terms, a much bolder and more courageous source of titillation.

This film, made solely for sensationalistic reasons, was supposed to depict racial problems on the fictional West Indian island of Santa Marta, but it became simply a visually fascinating document without a real sense of purpose. Against a background of tropical beauty, a series of romantic attachments and longings are falsely attached to a group of famous personalities, each of whom is given as little to do as possible.

Harry Belafonte, a Negro singer who has risen to the astonishing and unprecedented stature of a matinee idol, was presented as David Boyeur, a labor leader for the island's native population, and his obvious attractions for a socially distinguished white beauty, Mavis (Joan Fontaine), created a furor among the Southern theater exhibitors, who either banned the film or deleted the Belafonte-Fontaine sequences. Actually, there were no love scenes between the two, only glances of admiration and dialogue of almost Firbankian simplicity. In fact, Boyeur's decision not to make love to Mavis is evasive and full

American film mythology: Integration leads to death.

Kathleen Maguire, Sidney Poitier, and John Cassavetes

in scenes from Edge of the City .

of chop-logic, and every indication is given that poor Mavis will literally pine away thereafter among the mango trees. On the other hand, a Negro girl, Margot (Dorothy Dandridge), is allowed to embrace and eventually marry a white English civil servant (John Justin) and, although their life on Santa Marta is segregated, they finally sail happily off to England together at the end of the film. And so, the crux of the matter of miscegenation is again at the mercy of the film production code. Although "color" is the most important problem on the island, it seems that a white man may marry a Negro girl and not only live , and live happily, but that a Negro man and a white woman dare

not think of touching. There is an odd moment in Island in the Sun when (after watching Mavis yearn for Boyeur in sequence after sequence) the Negro reaches up and lifts her slowly from a barouche, holding her waist. The shock-effect of this gesture upon the audience was the most subtle piece of eroticism in the film, and only the lack of honesty in the work as a whole made this hint of a prelude-to-embrace seem realistic.

Island in the Sun also stirred other concepts about color, for the problem of concealed racial ancestry is introduced, bringing out all sorts of moody behavior on the part of a young girl, Jocelyn (Joan Collins), and her brother, Maxwell (James Mason). Jocelyn attempts to break off her engagement to an English nobleman, but he ignores her racial anxieties and is willing to chance the improbabilities of an eventual albino in the family. Maxwell, however, is driven into gloom, drink, and eventual murder, one feels, because the Negro skeleton in the family closet has thoroughly rattled him. The entire film is certainly important as a study of the tropical myth in racial terms, and even Dandridge's character, though she comes out of the whole business fairly happily, is not entirely free from the stereotype of the Negro as sensualistic, for, at one point, she performs a rather unusual Los Angeles–primitive dance among the Santa Marta natives, an act that is quite out of character, if one knows anything at all about the problem of class consciousness among the Negroes themselves in the West Indies.

Miss Dandridge has been continually cast as the typically sexy, unprincipled lady of color, in all-Negro films like Carmen Jones (1956) and Porgy and Bess (1959), as well as in a singularly appalling film called The Decks Ran Red (1958), in which she is the only woman aboard a freighter in distress and, naturally, is pursued by a lusty mutineer, with much contrived suspense and old-hat melodrama. It is ironic, under the circumstances, to recall that this actress's dramatic debut in films coincided with that of Belafonte in Bright Road (1955), a minor work about a gentle schoolteacher and a shy principal in a Southern school.

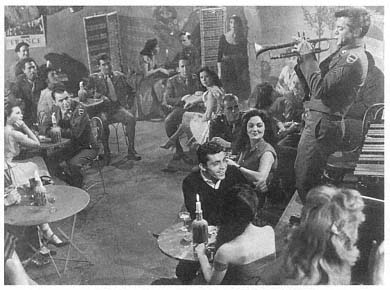

The commercial success of Island in the Sun led to the decisive movement in Hollywood to make films dealing specifically with the theme of miscegenation. The color question appeared in the most unusual situations, particularly Kings Go Forth (1958), an epic cliché of wartime in France, where two soldiers (Frank Sinatra and Tony Curtis) find it nicer to be in Nice than at the front. Sam (Sinatra) falls in love with Monique Blair (Natalie Wood), whose parents are American, although she has been reared in France. Monique lives with her widowed mother, and reveals to Sam that her father was a Negro. Exactly why this is introduced is never really clear unless it was intended to bring some sort of adult shock to a basically What Price Glory situation, for even Mademoiselle from Armentières is fashionably under the color line in contemporary war

American film mythology: American GIs are more susceptible to

miscegenation. Far left : Natalie Wood and Frank Sinatra,

right : Tony Curtis, in Kings Go Forth .

films. There is also a triangle complication, for while Sam is away, Monique becomes infatuated with Britt (Curtis) after hearing him play a jazz solo on a trumpet. This implies that even Monique's French upbringing cannot assuage the jazz-tremors of her American Negro heritage. Of course, nothing is solved in the film. Although Sam and Britt go through a baptism of fire and limb-loss, their characters are molded out of a screen clay pit as tough-talking, hard-drinking, callous hedonists, and the fact that both love and racial awareness are merged in their personalities is supposed to be basis for poignancy; besides, marriage with Monique is only weakly suggested at the conclusion of the film. Perhaps the most unfortunate part of Kings Go Forth was its adherence to the lamentable Hollywood practice of casting a white actress in the part of a mulatto heroine, thereby weakening even further an already unsuccessful attempt to jump on the bandwagon of popular film concepts regarding hardhearted American officers falling madly in love with foreign girls of another race. Kings Go Forth convinced one that racial films were once more in vogue, and the so-called taboo theme was simply a "gimmick."

Although it attempts boldness, Night of the Quarter Moon (1959) only belabors the question of intermarriage. Ginny (Julie London) marries a wealthy San Franciscan, Chuck Nelson (John Drew Barrymore), while on a vacation in Mexico. When she reveals that their marriage might cause them trouble because of her racial background (she is one-quarter Portuguese-Angolan, which is, one supposes, cause for some sort of genetic alarm), Chuck tells her that

such statistics only bore him. However, the film erupts into a succession of violent and racially antagonistic episodes on the part of Chuck's society-minded mother (Agnes Moorehead), the San Francisco police force, and the neighbors. The fact that Chuck is a Korean war veteran, susceptible to mental blackouts and fatigue, creates an odd impression about American film myths of this nature. It would seem that war veterans are more susceptible to miscegenation, and that certain environments, like the Caribbean or Mexico, actually put one into that frame of mind which considers racial backgrounds to be of major insignificance, eventually leading to intermarriage. All of this chaos leads to one of the most incredible courtroom sequences in film history, during which Ginny's Negro lawyer (James Edwards) strips the blouse from her back in front of the judge so that her skin color can be revealed as white. Night of the Quarter Moon did contain one notable feature, however. It showed an adjusted, sophisticated, and extremely articulate interracial couple, Cy and Maria Robbin (Nat Cole and Anna Kashfi), and Maria's summation of a white man's general attitude toward a quadroon is a very forthright and adult statement that takes one by surprise.

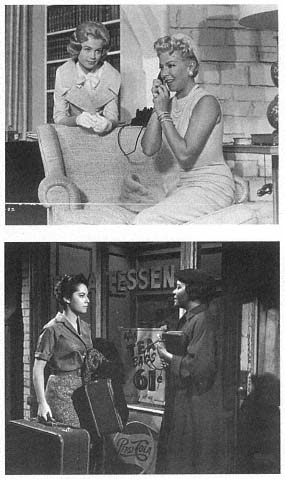

It is, indeed, the social position of an individual who is able to pass for white that seems to bear most interest for film-makers, and it was only a matter of time (28 years) before a remake of Imitation of Life (1959) would appear. Fannie Hurst's novel, a tear-jerker, could possibly have been a fine film, considering the different film techniques and audience attitudes of 1931 and 1959. However, the earlier version of the film is the more honest of the two, if only for the fact that the mulatto girl, the true figure of pathos, was played by Fredi Washington, a Negro actress. But the basic premise that any Negro girl with a white skin is doomed to despair on a social level is maintained in a most unreal and almost farcical manner. The clichés are kept intact and aimed at the tear ducts, and once more, one cannot help feeling that a Negro screen writer might have been able to bring subtlety into the characterizations. Imitation of Life is a hymn to mother love, a popular fable of ironic contrasts between the light and the dark realms of racial discrimination. A famous actress, Lora Meredith (Lana Turner), and her daughter, Susie (Sandra Dee), are devoted to the Negro maid, Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore), and her mulatto child, Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner). But it is the behavior of Sarah Jane as a beautiful young woman that is handled falsely. Living in a nonsegregated environment in a Northern metropolis, surrounded by the glamour of Lora's world of the theater, it is inconceivable that Sarah Jane would be made to feel inferior by people around her, especially since she is not, by any stretch of the imagination, obviously a Negro. It is equally incomprehensible that Sarah Jane's taste in clothes would not be affected by the chic apparel of both Lora and Susie, both of whom symbolize a world to which she very much wants to

"Ironic contrasts between the light and the dark

realms" of mother love. Above : Sandra Dee

and Lana Turner, below : Susan Kohner and

Juanita Moore, in Imitation of Life .

belong. The final stroke of absurdity lies in the sequence in which Sarah Jane is savagely beaten by her white boyfriend (Troy Donahue) when he learns that she is a Negro, implying that anyone who attempts to step out of an established class structure, racially or otherwise, must be subjected to physical violence. This attitude (equally out of place in a film like Room at the Top ) comes as a shock and reflects a dangerous kind of moralizing. As if inner anguish is not enough for an individual who is unable to successfully "pass" for white, or move from one social stratum to another, one must behold such a character actually beaten up and thrown into the gutter.

In Imitation of Life , Annie's funeral is epic sentiment in the charlotte russe tradition, complete with a spiritual by Mahalia Jackson—an episode that is

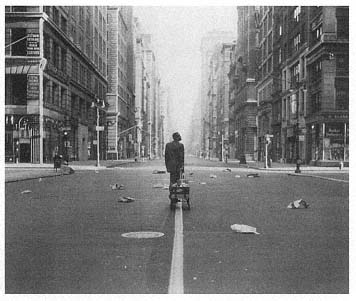

The hero in isolation: Harry Belafonte in The World, the Flesh and

the Devil .

completely fictional and as incredible to Negro spectators as it is to white; and Sarah Jane's psychological maladjustment never leads one to imagine that she would so blatantly embrace her Negro heritage by hysterically throwing herself upon her mother's coffin; also one is never told what the girl eventually does or becomes. What is not understood by the makers of Imitation of Life is that a Negro's sympathies are with Sarah Jane, not Annie, and that contemporary audiences are able to discern the finely hypocritical dictums of the fake solution, the outdated stereotypes of the code, and, in a sense, the anti-integrationist's point of view.

The Negro character in the nineteen-fifties is very much the hero or heroine in isolation, and the cinema never quite illustrates this quality of "invisibility" and frustration as often as it should. Perhaps the most effective presentation of this particular aspect of racial adjustment is The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959), in which Ralph Burton (Harry Belafonte) finds that he is the only person alive in New York City after some great destructive force has swept away all human existence. The horror of loneliness in New York, a potential Angkor Wat surrounded by steel foliage, is brilliantly evoked, at once underlining one's contemporary fears of sudden radioactive destruction, and emphasizing the symbolic figure of the Negro hero alone in society.

The appearance of two white people throws the film back into the world of color consciousness. Sarah Crandall (Inger Stevens) meets Ralph, and for a time they exist together, but he insists upon maintaining separate living quarters. The racial issue remains symbolically in his mind, though, in reality, it is gone with the civilization around them. When Benson Thacker (Mel Ferrer) arrives, however, a triangle is created, a wall of simple-minded clichés obscures the true situation, and, after a gun battle and fight, the men declare peace, join hands with Sarah, and walk into the oblivion of Wall Street together.

This parable exemplifies today's approach to the theme of interracialism: vague, inconclusive, and undiscussed. Like a fascinating toy, American film-makers survey the problem from a distance, without insight, and guided by a series of outmoded, unrealistic concepts regarding minorities. The major irony is this: that in a country where life is actually lived quite freely with races so intermingled, it is still difficult to capture this sense of freedom, of humanity, this robust diversity of backgrounds of American life upon the screen. As far as motion pictures are concerned, the Negro character remains mysterious because he is the most diversified by background, by color, and by regional dialect, and, considering the number of films involving Negroes, the race as a whole is inadequately represented on the screen. Represented solely by limited night-club entertainers and recording artists, and only a few outstanding young actors (Poitier, Belafonte, and Henry Scott, who has appeared in only one small role so far), it is no wonder that audiences cannot get a sense of truth between the black, brown, or beige images that vary so greatly from celluloid to reality, from mythology and stereotype to history and drama.

Recent Film Writing:

A Survey

Ernest Callenbach

When I was little, I wanted to be a mathematician. I have always been fascinated by those who do pure research, by the great mathematicians who, by making an advance in one direction, unlock years of fruitful research possibilities for succeeding generations. This taste for research is quite personal and absolutely irrational.

—Jean-Luc Godard to Jean Collet, Sept. 1963

Vol. 24, no. 3 (Spring 1971): 11–32.

Ernest Callenbach © Ken Stein

It's a satisfaction to film people, in a general way, that so many film books are now being published. After the long lean years, it's comfortable to think that our faith in the art is at last being justified. For if anything signifies Seriousness, it is books. Yet a publisher and editor like myself must be constitutionally skeptical, in hopes of conserving both sanity and trees. The motives people have for wanting to publish are, to say the least, mixed—though we have only recently begun to receive in the film field any sizable number of manuscripts that are clearly sprung from the publish-orperish fount, that source of so much academic intellectual corruption (not to mention the waste of paper). And especially in a field where the pace of publication has increased so fast, we need to stop and try to take stock of the purposes and worth of what has been done. There have been a tremendous number of film books published in the past year or so, although the output relative to that of the established fields like English or sociology is still modest. Once, we could have the easy feeling that we could read everything that came out. We now face a situation like that in older fields,

where specialization is forced on us whether we like it or not: nobody has the time to read all the books that are appearing. I regret this, personally speaking, because it means a kind of fragmentation and dispersion of intellectual activity, but it seems to be inevitable whenever any subject is attacked by large numbers of people; in science, matters have gone so far that the dozen or so workers really concerned with a given problem communicate with each other by telephone, xerox, or at worst mimeograph, between Berkeley, Cambridge, Dubna, or wherever, and only see other scientists at occasional meetings; publication itself is a side product of the process—not unimportant, of course, but it merely memorializes what has happened, and adds to the problems of the abstracters and information-retrievers. (When Watson and Crick had cracked the DNA structure, they took pains to bring their report down to a crisp 600 words, and could hardly be accused of littering up the intellectual universe.)

Film is still, however, within the domain of the humanities for most writers who address themselves to it. An occasional sociologist ventures some notions, usually with a generality that film historians consider flimsy; an occasional psychologist uses film as a research recording tool. There are probably some curious scientific problems involved in film perception, but so far no psychologists have found them interesting. People writing about film have usually been interested in it either because it's an art that intrigues them (like most critics) or because it's a mass medium they hope can be turned to political advantage (a tradition going back to John Grierson, who was a political scientist and socialist agitator). We are now, however, coming to a point where both of these emphases seem limited and insufficient, and people seem to be getting ready to try integrating them, to deal with film as an art that is inherently political even in the most apolitical hands. . . .

It seems to me that we now have critical resources that greatly surpass those of a decade ago; our general-audience magazines, in particular, are now immensely better served, and the critical books which have flowed from this journalistic work seem to me to constitute a remarkable outpouring of critical energy, knowledge, and intelligence. Many new and good critics continue to develop within the specialized film journals. As a congenital pessimist, I choke to say it, but we have never had it so good.

Nevertheless, speaking more as an editor than a critic, I would like to try here to make some sense of what has been happening in film criticism recently on the level of ideas. I do not propose another round of critical arm-wrestling, of which I am probably more tired than any reader could be. Nor do I have a defensive attitude about film criticism's contribution to our culture. It is reported that when an actor attacked John Simon, in a television debate, Simon tried to justify his role as a critic by lamely recounting how he had worked in

dramatic productions and so on; even Pauline Kael, when attacked along the line of how can you know anything about it if you've never done it, once retreated to telling of her work with the San Francisco underground. Such arguments are farcical because they ignore the fact that criticism is an art in its own right. Writers who can get hundreds of thousands of intelligent persons to read their stuff are clearly practitioners with some kind of real skill; but it's not the same skill that film-makers have, much less actors. Like film-making, criticism is a kind of culture-secretion, and they share a few elementary prerequisites like taste and intelligence; but the working requirements of the two are utterly different. We might as well demand of an actor that he be able to write a readable, stimulating, informative critique as ask a critic to act (or direct, for that matter). The business of the film-maker is to make films; the business of the critic is to react to them—as sensitively and intelligently and wisely and interestingly as he can. I don't find a balance of presumption on either side. There is a plainly visible Darwinian selection process among critics, just as among actors; if you can act or write so that it impresses and interests people, and have reasonable luck, you'll be able to work and become known. It would be excellent if more critics tried their hand at scriptwriting or directing, and more directors tried their hand at writing criticism, but it isn't obligatory; they are working opposite sides of the same movie street, and should have the mutual regard of good gunfighters or good con men or good trial lawyers.

Our critics span a range of philosophical assumptions and tastes which is broad enough (though so far entirely bourgeois) to cope with almost all films produced in recent years, one way or another; you have always been able to find a critic who could deal with films in a way that seemed reasonable to you, whether your tastes ran to Hawks, Kramer, or Bergman.

In what way, then, can this body of critical work be considered deficient?

One way to begin is by noting that practically nobody writes books of film criticism. If this seems a strange statement after a year when more film books have probably been published than in all previous publishing history, consider that among the books that could be considered as serious, major criticism only a tiny handful were original, "real" books—Wood on Bergman and Higham on Welles, above all. For the rest—Kael, Farber, Sarris, Pechter (and Youngblood to a lesser extent)—all was packaging together of previously written material. I indicated earlier one practical reason for this—you can make a living by writing for magazines, and you can't just by writing books. Robin Wood, I believe, mainly teaches to live; so does another excellent British writer, Raymond Durgnat. But in this country our film teachers don't seem to include talented critical writers, with the exception of Sarris, who has begun to teach at Columbia.

Now journalism is not necessarily a bad thing for writers. Bazin was, after all, a journalist, and a harried one at that. Some of Shaw's best writing was done under journalistic pressure. A weekly deadline can be an inspiration, and so can the fact that in weekly criticism you get no chance for second thoughts or leisurely revision. Nonetheless, writing in the review format has drastic limitations. You can imply theoretical matters, but in the general press you had better be sure they don't get too heavy. You can revert to themes broached in another piece, but you had better make every review essentially free-standing—you can't depend on the reader keeping a connected argument in mind from one to the next. You can mention old films, but you had better organize your reviews around current ones, and if you generate any historical perspectives, you had better keep them light. Moreover, the finer a writer you are, the harder it becomes to turn your reviews into genuine chapters of a book (even supposing editors encouraged you to try); for a review done by a skilled writer is a special-purpose item that cannot easily be put to other purposes. From a practical working standpoint, thus, reviews aren't really useful grist for an integrated book—they may, indeed, be outright obstacles.

An equally severe problem with working as a weekly critic is that it forces you to waste your time: especially with today's situation where foreign films are having a hard time entering the U.S. market and domestic production is falling off, there simply isn't a film worth writing about every week. (Or indeed sometimes every month.) And this disability is simply memorialized in the ensuing books. In Going Steady , for instance, out of some 76 films Kael discusses, about 10 seem to matter to her as films. She has important and intriguing things to say about many of the unimportant films; but when the balance tips this far one feels it as a waste of talent—not only is criticism here an independent art, but a superior one; it's like devoting an orchid-grower's finesse to the production of snap beans. There is no question that the ordinary output of an art-industry like film deserves some attention, above all because the first works of promising talents generally fall into the less-than-triumphant category, and also because film criticism is inevitably cultural criticism and must convey to the reader some sense of the general cultural output surrounding works of unusual interest. But what we most relish in good criticism is the sense of a fine mind responding to a fine work: in fact, it is the excitement of this give-and-take process, which Kael is extraordinarily good at conveying, that makes criticism an art: who really reads critics to obtain ratings for movies? Sometimes, indeed, the critique that fascinates us most is busily setting forth an opinion on a film utterly different from our own. (Just as, in science, we may admire a co-worker's experimental technique but believe that his results must be interpreted differently.)

As a group, our American big-time critics are very good at responding to movies; in one way or another, they make you feel that it would be simply

marvelous to hang around listening to them in person. (Complaints have even been heard about the cult of personality in film criticism, where the critic becomes the star just as the director has.) They are sensitive and witty people, often with a stunning gift of phrase. I think it not far off to say, however, that general ideas do not much interest them. Why this is, I do not pretend to know; perhaps there is something about the very act of writing criticism which means that one tends to so intently focus upon the work in immediate question that sensitivity in that context triumphs over all more general kinds of mental activity. Theorizing, that particular speculative curiosity which motors science, takes after all a very special mental set. Its presumption may even be inherently at odds with art, which is by nature unsystematic, ad hoc, furtive, messy, vital. (Or so at least I would imagine Pauline Kael might argue.) The theorist must attempt to "rise above" individual cases, to arrive at large generalizations—a process which inevitably dissociates his sensibility from actual films, at least to some extent. It is significant that Bazin, the most theoretical critic of our times, also relied constantly on scientific allusions and metaphors in his work.

Theorizing can be a pleasure quite in itself, of course, just as playful activity. But as a kind of intellectual work it appeals to disappointingly few people. Besides, it's scary; as Kael remarks, "In the arts, one can never be altogether sure that the next artist who comes along won't disprove one's formulations." However, this is a risk any person who indulges in what we might very loosely call "scientific" thinking has to take. Indeed it is practically foregone that one will look a bit silly, for every generation of scientists reworks and refines previous thought—sometimes even throwing it out bodily. There is no reason to hope that criticism (even Bazin's!) can be exempt from this process; nor can concentrating on the refinement of taste exempt one—for tastes too change, indeed even more rapidly and irrationally.

Criticism needs ideas, however, and I would like to spell out some of the reasons, perhaps a bit painfully. Criticism cannot in fact rely upon "taste" alone; every good critic's way of thinking rests, if we bother to analyze it carefully, upon a pattern of assumptions, aesthetic and social; and it employs a constellation of terms appropriate to those assumptions. The act of "criticism," in essence, as opposed to the mere opinion-mongering of most of the daily press, is the application of such terms to the realities of a given film: describing it, analyzing it, evaluating it, and in the process also refining the terms and assumptions. Nobody would enjoy it much if the process were carried out in an obvious and mechanical way; on the other hand, there are benefits to be gained by carrying it out with more intellectual elegance and determination than are customary among our film critics. For the terminologies current today really don't seem to be suitable for coping with crucial current developments;

they leave the sensitivity and intelligence of the critics stranded whenever a difficult new film appears—a Persona, Weekend , or Rise to Power of Louis XIV .

Assumptions and terms reasonably suitable for dealing with conventional narrative fictions have been around for a long time. Basically "realist" in tenor, these ideas have never applied very well to non-narrative and expressionist forms, especially experimental ones; the neglect of experimental film by critics has been due at least as much to practical embarrassment at this as to the inaccessibility or low quality of the films. They have also, as Brian Henderson suggests . . . not been very useful for analyzing internal ("part-whole") relationships in works of art—precisely the kind of formal analysis we need to fall back on in a period like the present when relations to reality have become largely moot.

Realist assumptions tend to deal in terms of essences, but film has no single essence such as Bazin sought—it is a multiform medium, and all signs point to our entering a period of increasing fragmentation. We may never reach another consensus, such as underlay traditional Hollywood craftsmanship, as to what film is or ought to be. Assumptions may henceforth have to be couched in terms of polarities, or "ideal types." The notions that will seem natural to the future are almost literally invisible to us, because they will make assumptions we cannot entertain. It seems certain, however, that any new nomenclature must include terms for dealing with the relations between the art's materials and its forms, and the relations between the work and its viewer. Surrounding and to some extent subsidiary to such terms will be various others concerned with technique or style: questions on the level our criticism now chiefly deals with. But where are the critics who are developing new terms? (I must reserve judgment about the "structuralist" school of analysis until it shows itself more clearly in English; so far, work under this banner has seemed either conventionally literary-thematic analysis or "iconography" on a stupefyingly naive level.)

The critic needs new ideas because otherwise it is impossible to articulate what the new film-maker feels and does; otherwise the most delicate critical faculties can register only zeroes. Most artists, of course, have ideas they are plenty willing to express, and indeed often talk in a strongly programmatic style. (The Flaherty Seminars were an attempt to institutionalize this phenomenon.) It's seldom, however, that artists have an interest in or grasp of large trends in their art, and the root act of artistic creation is in any event not ideational. A rare film-maker, like Eisenstein, happens to be good at theorizing about his own kind of work; Godard, in his elliptical and maddening way, seems to be the only one around at present. But aside from such rare exceptions, we will get our ideas about what is going on from critics, or we will not

get them at all. It would be a good thing if our critics could, over the next couple of years, come up with some new and coherent ones.

Every critic worth reading has some heresy to propound, and William Pechter's in Twenty-four Times a Second (New York: Harper & Row, 1971. $8.95) is that of revelation: he believes that the truth is ready to hand, if only somebody will come forward to seize it, like Lancelot picking up the magic sword. Thus he tends to be a little scornful of other views, brashly over-confident that he is of the Elect. In fact, when he is good he is very good, but sometimes he is not. His explication of Breathless is acute, energetic—his abilities outstretched to cope with a challenging work. His defense of de Broca's Five Day Lover , and of de Broca's essentially noncomic talent, is the kind of clarification of style and genre we badly need and rarely get. But his attempted clearing of the air about Marienbad gets nowhere because he is unwilling to entertain the possibility that the film is as psychological as it is, and as un "moral"—he writes of its containing "scarcely a line of dialogue that one can imagine being spoken." Yet clearly, if the film makes any sense to anybody at all, this can't be true. And it seems in fact that most of us, though perhaps not Pechter, do indeed "imagine" dialogue like Marienbad 's in plenty of our adolescent and not-so-adolescent fantasies. It's bad dialogue, perhaps; but that doesn't keep us from imagining it—quite the contrary, for it is a minor subspecies of pornography, whose necessary repetitiousness and obsessiveness it shares. The Marienbad case sets one limit for Pechter's method; to his relentless moral tests, the film yields no clear pink or blue reaction. It makes no statement; yet it exists, it presents something. But that something is not of the order which Pechter can analyze; he complains, thus, that "the deeper we probe into the characters' consciousness, the less we know and understand them." But what if the film is not "probing," or at least not probing "characters"—what if it is the complex embodiment of fantasy, something like visual dreaming? Pechter even ventures to speak confidently of "failure" when he surely must have considered that he could be misunderstanding the film's intention. At the end of his essay, conscious of the problem, he poses it in fancifully stark terms: whether art serves beauty or knowledge. He declares roundly that the end "must, of internal necessity, be that of knowledge"—but only after qualifying this to apply only "where the subject of art is the human being, at least, the human being as protagonist of an action." Thus finally he must beg the question—for whatever Marienbad is, it does not seem to be that sort of art. It is, rather, some weird transitional variant between the film drama we are familiar with and some as-yet-undefined species toward which film is moving. As Kipling had it in his story, something that is neither a turtle nor a hedgehog may still come

into existence and survive, and somebody will come along to name it armadillo. But poor Marienbad has no category in Pechter's nomenclature.

Nor is Pechter, to my way of thinking, really any more reliable than most critics on more conventional fare. In dealing with The Wild Bunch , he neglects the important machismo side of Peckinpah's personality (the film in fact owes major debts to a Mexican novel). Pechter thinks Nicholson the only interesting thing in Easy Rider , whereas his actorish performance seemed to me the major tonal flaw in the film—entertaining, but as out of place as an interjected juggling performance might have been.

Pechter's essay against Eisenstein is a bold attempt at a major overhauling job, but it still seems to me rather perverse. This is not because of its judgmental side—I am not greatly agitated by the question of whether or not Potemkin is a Great Classic, though I think it is rather more humanly interesting in an allegorical way than Pechter does—but because his essay merely sets up an undergraduate dichotomy and plumps for one side of it: Bazin and Renoir over Eisenstein and montage. But in the art history that must some day be written about film, no film-maker is an island; and Eisenstein, whose thought is immensely more complicated and subtle than Pechter admits, will have to be evaluated not only in the circumstances of the deadly society he inhabited but also in the context of a larger world artistic tendency with counterparts in other arts. Pechter skirts edges of this large problem here and there—he quotes Eisenstein on Joyce, thinking to ridicule only Eisenstein—but doesn't try to do anything with it.

Of Bergman, Pechter has little good to say—and even less of the recent films, where morality has given way to psychology and what Bergman also thinks of as a kind of music. He is good on Psycho; though (as I did too at the time) he misapprehends the ironies of the phony psychological ending. He makes a valiant defense of The Birds on the grounds that it is about "Nature outraged, nature revenged"—a kind of premature ecology story, with Jobian overtones—which I find clever but hopeless, fundamentally a city person's misplaced fantasy ("nature's most beautiful and gentle creatures . . .").

Was will der Mensch? one of my philosophy professors used to begin by asking. And in Pechter's case the dominant underlying concern seems to be with the question, "Is this film or film-maker truly great?" The question can be interesting, and attempted answers to it can be interesting; but as an organizing principle of analysis it seems to me somehow deficient—its role really ought to be that of a working hypothesis, as it was for Bazin, but not the end of enquiry. Assuming and believing that Bicycle Thief is great, or that Diary of a Country Priest is great, Bazin always goes on to propound ideas of another order: ideas having to do with how the films work upon us, what their aesthetic assumptions and strategies are, ideas in short having to do with style, in

the largest sense. Pechter has some ideas about style, but they largely boil down to negative propositions. Eisenstein is a bad artist (and a bad man, as well as a bad writer) because he elevated art above truth, thus betraying both man and art. Marienbad is a bad film because it is not about character and plot in a manner that provides "meaning" or truth. Bergman is a bad director because his is an art of surfaces.

Well then, what is this truth? Don't stay for the answer, because there really isn't one. Each artist has his own truth: Buñuel's that "this is the worst of all possible worlds" (I'd like to verify the original on that some day—did he say "the worst" or "not the best"?); Welles's, Renoir's, Fellini's. It seems to be, in fact, essential to a great artist that his truth cannot be described. But it is the role of the critic to discern and announce its existence, and to excoriate all those false artists who don't tell the truth.

Whatever its virtues, this is a narrower conception of the critic's task than most critics accept. Consequently, Pechter heaps much scorn for their laxness upon film magazines, film books, other film critics, and "film enthusiasts," and thus generates unfulfillable expectations in the reader that his own book will somehow be a quantum jump ahead of other film writing. Pechter is a most intelligent and sensitive critic; disconcertingly, what keeps him from the very front ranks is precisely a certain hubris, a prideful fastidiousness which can become suspect even though it never becomes crippling as it does in the work of John Simon. Pechter quotes Lionel Trilling, on Agee, as saying that "nothing can be more tiresome than protracted sensibility"; but his 300 pages of careful, judicious, humane prose end merely with a section called "Theory," leading to the conclusions that critical consideration of art must be whole, cannot concentrate on mere technique, and is inherently dependent upon reactions to "the aesthetic ramifications of art's meaning."

It is any critic's right to imply that his candlepower exceeds others' by a significant margin, or that the darkness is denser in film than in other parts. But it is more accurate, as well as more modest, when critics recognize that their work is part of an inherently confused welter by which tastes and ideas rub upon created works and little by little give off the light, such as it is, by which we and posterity understand them. Bazin, who seems to me the most important film thinker of our times, was too busy analyzing films, trying out his ideas on them, constantly testing and revising and rethinking, to be much concerned with the sort of ultimate, permanent critical purity Pechter envisages as the goal. I would be the last to deny that film criticism could use a lot more sensibility of the kind Pechter possesses; but in itself that is not enough. We also need new ideas; and the fundamental ideas lurking in Twenty-four Times a Second , as in virtually all other current film writing, are still Bazinian. It is as if Bazin had thoroughly ploughed the field of film aesthetics right up to the edge of the precipice. We can

retrace his work, refine it, even eke out a corner here or there that he missed. But nobody has yet figured how to fly off into the space at the edge.

Ironically, the only critic around with a patent on a theory is Andrew Sarris, whose success as popularizer of the "auteur theory" was, as he genially points out in the introduction to Confessions of a Cultist , entirely inadvertent (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1970. $8.95). Worse still, this theory isn't a theory at all, but a practical critical policy: a good one within obvious limits, but of no analytical significance in itself whatsoever. When we look back over Sarris's columns of critical writing, as assembled in this volume, it's surely just as much a shambles as the film criticism he observed about him in 1955. He's a master of the light phrase ("Neorealism was never more than the Stalinallee of social realism") and he is charming about his extra-theoretical divagations—at least when you share them, as I do about Vitti. Sarris makes a halfhearted attempt to turn the auteur theory into "a theory of film history" in the introduction to The American Cinema ; but a little later he remarks that it's "not so much a theory as an attitude." Actually, he doesn't have a real theoretical bone in his body; he is a systematizer, but that's quite a different matter, just as entomologists who revise the species classifications for bees are useful scholars, but not doing the same kind of work as researchers who try to figure out how bees fly. Sarris's early formulations of auteurism, as about The Cardinal , are significantly evasive: "Preminger's meaning" is said to be strongly expressed visually, but is nowhere described—as indeed, judging even by what else Sarris says of the film, it could hardly be by anybody. Admittedly, in this volume we get only a truncated Sarris. But a truncated pyramid is still visibly a pyramid. When one takes away Sarris's holy categories, however, there is nothing theoretical left; what is left is an urbane, witty writer with an elephantine memory and an accurate eye who often has sensible things to say about individual films and who can occasionally, as in his account of seeing Madame X on a transatlantic jet, become quietly and movingly personal. The generalities he will sometimes venture are usually perverse: "The strength of underground cinema is basically documentary. The strength of classical cinema (including Bergman) is basically dramatic. The moderns—Godard, Resnais, Antonioni, Fellini—are suspended between these two polarities." Moreover, by 1968 he could write in the New York Times a piece whose defense of auteurism is so mellow that it must seem mild to Pauline Kael (who can, of course, out-auteur anybody when she feels like it). At this point it seems clear that Sarris's contribution to American film thought has been massive in transmitting enthusiasms but minimal in analytical ideas.

Perhaps disappointingly, neither Dwight Macdonald on Film (New York: Berkeley Books, 1970. $1.50) nor Stanley Kauffmann's new collection, Figures

of Light (New York: Harper & Row, 1971. $7.95), offer any explicit, coherent view of the new relations developing between art and audience, though they are our two most socially concerned critics. Macdonald was famous for his own attempt at classification, his formula of masscult and midcult and kitsch . But as far as analytical ideas go, he cheerfully confesses that "being a congenital critic, I know what I like and why. But I can't explain the why except in terms of the specific work under consideration, on which I'm copious enough. The general theory, the larger view, the gestalt—these have always eluded me." He then trots out a number of rules of critical thumb, but only to prove his honesty by showing how they don't work. It is only in a piece about comedy that he is less diffident, and works out some general principles (he calls them "rules"); but these could apply to novels or plays just as well as to films. His long and careful commentaries on Soviet film, written in the thirties and forties, are to my mind excellent cultural criticism of a kind we also could use, but they don't contain anything original about film style.

Kauffmann, though he is concerned with the new audiences and the delicate balances between commercial hype and genuine novelty in "youth" films, isn't willing to venture any general ideas about what is going on, either; at the end of his new book he takes refuge in the vague notion that "standards in art and life are becoming more and more congruent." In a day when survival is a catchword, it may be true that criticism should select and appraise "the works that are most valuable—most necessary—to the individual's existence ." But how do we know which works those are? To determine this, we need ideas about the society we must survive in, the role of art in it, how we "use" art, and what makes art "useful."

The virtues of Manny Farber (Negative Space . New York: Praeger, 1970. $7.95) have usually been taken to be those of the wise tough guy who looked at movies for their secret pleasures—those precious moments in the action flicks when a clever actor and a "subversive" director got together either to spoof the material or give it an instant of electric life. He liked plain, grubby stories, and he was allergic to pretensions at all levels, including those of auteurists; he could write of Hawks's Only Angels Have Wings as a "corny semi-catastrophe" and conclude that "No artist is less suited to a discussion of profound themes."

But there's more to Farber than that. Farber hates what has been happening to movies since about 1950, but that doesn't really matter; he could just as well have loved it—except that adoration has a tendency to blur vision. What counts is that he notices what has been happening, and indeed has been more willing than any other critic to try and elaborate on it in fairly general terms. If he might be called an aesthetic reactionary, at least he's a conscious and articulate one. Like Bazin, of whom one perhaps hears faint indirect echoes in

Farber from time to time, he believes in realism. The excitement of action films comes from the fact that they confront us with the gutty, tough, cynical inhabitants of the American lower depths caught on the fly in miscellaneous unhallowed adventures, racing through stories of greed and desperation under the guidance of skilled and modest craftsmen. Appreciation of such films is a kind of shock-of-recognition operation—the film whirls you through its itinerary and here and there you notice things that matter, because they are real . Farber would never presume to hope for what Bazin saw in neorealism—whole, finished works of dense and convincing realism—but he would have wanted it if he thought it could happen here.

Yet Farber never confronts the philosophical or aesthetic or indeed practical problems such a position presents. He is not some kind of Christian like Bazin, so he has no doctrine of immanence or anything like it. Though he is aware that film involves much pretense, he is unwilling to consider that "realism" is itself a set of conventions; his defense of the old style is ultimately an impossibly simplistic "imitation" theory. Thus he can argue: "What is unique in The Wild Bunch is its fanatic dedication to the way children, soldiers, Mexicans looked in the small border towns during the closing years of the frontier"—as if he (or we) had to have been there to enjoy or appraise the movie. He never confronts the phenomena of camp, whereby a bit of acting which strikes him as utterly real can seem totally phony to somebody else—especially somebody coming along a couple of decades after. (It has been found that fashions in clothes can't be revived until 30 years have passed; does a similar cycle length perhaps prevail for film acting?)

But, from the standpoint of his devotion to the old Hollywood style, Farber sees pretty clearly what has been happening: how the former "objective" style, the anonymous, geographically reliable world of the Hollywood writer, cameraman, and editor, has given way to far more dubious forms dominated by directors, in which some vague directorial viewpoint or personality or style is supposed to be the center of interest, rather than the plot.

Nor is Farber's perceptiveness only a recent development. As far back as 1952 he was complaining about A Streetcar Named Desire that "The drama is played completely in the foreground. There is nothing new about shallow perspectives, figures gazing into mirrors with the camera smack up against the surface, or low intimate views that expand facial features and pry into skinpores, weaves of cloth, and sweaty undershirts. But there is something new in having the whole movie thrown at you in shallow dimension. Under this arrangement, with the actor and spectator practically nose to nose, any extreme movement in space would lead to utter visual chaos, so the characters, camera, and story are kept at a standstill, with the action affecting only minor details, e.g., Stanley's backscratching or his wife's lusty projection with eye and

lips . . . the fact is these films actually fail to exploit the resources of the medium in any real sense." He exaggerates, of course; moreover, a few years later Kazan was to be the first director actually to use the vast expanses of CinemaScope with any visual activity—in East of Eden , a film Farber did not comment on. And we must admit that Farber's analysis is often careless and suspect. Thus he remarks that Toland's camera in Kane "loved crane-shots and floor-shots, but contracted the three-dimensional aspect by making distant figures as clear to the spectator as those in the foreground." Would space have been expanded if they were fuzzy? On the contrary, keeping the backgrounds blurry (and the lead players in stronger light than anybody else) was a basic device of standard Hollywood craftsmanship to avoid perception of fuller spatial relations, resulting in compositions where the figures stood out but not really against anything—only as differentiated from a background blur, usually of constructed, shallow sets.

Nonetheless, Farber's basic descriptive contention cannot, I think, be escaped: "The entire physical structure of movies has been slowed down and simplified and brought closer to the front plane of the screen so that eccentric effects can be deeply felt." (81) "Movies suddenly [in the early 60's] changed from fast-flowing linear films, photographed stories, and, surprisingly, became slower face-to-face constructions in which the spectator becomes a protagonist in the drama." (190)

Since the Hollywood film is dead, and Farber knows we can never go back to that aesthetic home again, what is left? In a melancholic survey of the 1968 New York Film Festival, he plumps for Bresson's Mouchette —because of the girl's toughness, the down-and-out life surroundings taken straight; his terms of praise are that the film is "unrelievedly raw, homely, and depressed," and here for some reason he does not mention Bresson's camera style, or note how odd it is that Bresson's excruciatingly refined and stripped-down handling should be the last refuge of the streamlined naturalism he loved in the action flicks. There's not much left in the cinema to love, for Farber. Some of Warhol's odd characters appeal to him; he approves of Michael Snow's "singular stoicism"; he likes Ma Nuit chez Maud because of Trintignant's performance and the richness of its provincial detailing, and Faces grabs him because of Lynn Carlin. But no more do we enjoy "the comforting sense of a continuous interweave of action in deep space." We're caught up instead in conversations about movies—"a depressing, chewed-over sound, and . . . a heavy segment of any day is consumed by an obsessive, nervous talking about film."

For readers who only know Farber by his famous piece on "underground" (action) pictures, this new volume will establish that he is indeed one of our first-rank critics, with a very personal vision, an often irritating yet suggestive style, and faster ideational reaction-time than anybody around. But the acuteness of

his vision is like looking down the wrong end of a telescope; everything looks very sharp, but small and going away.

In the one corner, thus, we have Farber, stoutly bemoaning the destruction of the movies—the replacement of the plotted and acted picture by exudations of the director's twisted psyche. In the other, we have Gene Youngblood, bemoaning the phoniness and redundancy of the plotted and acted picture and announcing the cinematic millennium because film-makers are at last portraying "their own minds."

I think Youngblood's Expanded Cinema (New York: Dutton, 1970. $4.95) is an important book, so I want to get out of the way some minor criticisms of it. Youngblood writes in that blathering style common among media freaks—half Bucky Fuller mooning and half McLuhan "probes"—with a peculiarly alarming Teutonic tendency toward agglomeration. "The dynamic interaction of formal proportions in kinaesthetic cinema evokes cognition in the articulate conscious, which I call kinetic empathy." (Who won World War II, anyway?) He can be staggeringly naive or unperceptive. ("A romantic heterosexual relationship of warm authenticity develops between Viva and Louis Waldron in the notorious Blue Movie .") He is prone to wild exaggeration and imprecise logic, but he is also the only film writer on video technology to display mastery of the subject. He is very unhistorical, which may merely be fashionable disdain of the past, but is more probably a youthful lack of familiarity with both the conventional and experimental cinema of the past—however lamentably unexpanded they may have been. Nonetheless, its drawbacks do not prevent the book from being a forceful and clear exposition of a theoretical position, like it or lump it.

Youngblood's view can be sketched thus: all previous cinema has been deficient because it has been falsely and tautologically "about external things, to the neglect of the proper subject of cinema, namely the mind of the film-maker. In the synaesthetic cinema or expanded cinema, however, this dominance of the external is thrown off; all things become subjects of film perception and expression, nothing is taboo, "unfilmic," or impossible to deal with, and people use film as freely or wildly as poets use words. It turns out that the really distinguishing mark of synaesthetic cinema is superimposition, which guarantees that you are not seeing via a "transparent" medium, but via one which somebody has created—the function of superimposition is perhaps similar to that of the frame or canvas surface in illusionist painting. Sound is dissociated from image—for, as Bazin remarked, the coming of synch sound extinguished "the heresy of expressionism," and Youngblood is reviving it.

All this has some smell of novelty; does it perhaps have the substance as well? What is the philosophical and ideological basis of such a doctrine?

One way of getting at this question is to look back at earlier major shifts in film "theory." We can now see that Bazin crystallized, in his defense of deep-focus and neorealism, the essence of the cinema of Christian Democracy—postwar European liberalism. (As Bazin himself pointed out, it is no argument against this that Italian script teams, for political insurance, customarily included one Communist, one Christian Democrat, one rightist, and one socialist.) Similarly, we can see in Eisenstein the essence of Bolshevik cinema—montage was "democratic centralism" in the hands of the film director, while deep-focus and widescreen allowed democratic participation in the image-reading process by the liberal middle-class spectator.

If we can see a similar over-simplified paradigm in Youngblood, it would probably be that of the coming technological slave culture, in which the masses of people are allowed to play with certain fascinating visual toys within a tightly controlled corporate society. At a discussion during the opening festivities of the University's Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, Youngblood spoke of people playing with visual equivalents of Moog synthesizers—processing bits of film into their own personal video trips, presumably rather as our ancestors used to gather round the piano and sing "Daisy, Daisy." What really catches his imagination is man-machine symbiosis: computers retrieving and storing and diagramming in a playful partnership with people—a sort of benign Big Brother fantasy in both the sibling and sociological senses.

There are two main problems with this kind of notion. One is aesthetic, and was put into blinding focus at the Berkeley symposium when somebody asked John Whitney how long it took him to make Matrix , no doubt expecting an answer like six hours. But it took three months of shooting (fully assisted by sophisticated computer hardware) and three more months of editing, filtering, and printing. Now Matrix is not a frightfully complex production project in its own area, and it is a highly precise, mathematical kind of work which probably entails less than the usual stresses and indecisions of artistic creation. In short, we are not about to enter some kind of aesthetic paradise in which every man can become his own electronic-wizard artist. Indeed the lesson of Youngblood's own tastes is that the best of the "synaesthetic" artists he discusses (Belson, Brakhage, Hindle) don't even use electronic technology, only rather ingenious but conventional home-made rigs, in which the impact of the human hand, brain, and eye can be directly and intimately achieved. I don't wish to assert that there is a simple inverse relation between technological involvement and artfulness—if there were, modelling clay would be our greatest art form. But artfulness does not spring from technology, it uses technology. When you ask machines to create something, as in the computer-generated films Youngblood describes, it comes out dreadfully flat and dull. Even the most sophisticated machines so far built have no sense of play.

What they do have is a high price tag, and this connects with the second problem, which is a social one. Modern technology is extraordinarily expensive, and it is owned, in a patent and often in a literal sense, by giant corporations which lease it out. Youngblood talks like some kind of radical, and writes for the underground LA Free Press , but he seems surprisingly comfortable with big business, and sometimes seems to think it philanthropically inclined to coddle our perceptions. Yet we must notice that the only way artists have gotten at complex video technology is through the ETV stations in San Francisco and Boston and by the "artist in residence" situation at Bell Telephone and a few other corporations. It is not only chroma-key video equipment which is tightly controlled, either; the coming wave of EVR and other cassette distribution systems is similarly tightly held, with patents flying like shrapnel. The sole aspect of video technology which is freely available to artists and users the world over—largely thanks to Japanese initiative, it seems—is half-inch video tape, a cheap, convenient but shabbily low-definition medium. Anybody using the other systems will not be his own master; he may not be as bad off as artists at the mercy of old-fashioned producers or distributors, but he will be in jeopardy whenever he becomes unorthodox.

Youngblood writes of the new technology creating a technoanarchy in which all men's creativity is freed. This kind of optimism is not just constitutional, of course, but springs from a particular philosophical position—one which, in my opinion, fits neatly into the program of the technofascism which is what is really developing in our society. Youngblood's position is a confused and oversimplified one. "We've been taught by modern science that the so-called objective world is a relationship between the observer and the observed, so that ultimately we are able to know nothing but that relationship." (127) A few pages later he breezily remarks, "There's no semantic problem in a photographic image. We can now see through each other's eyes . . ." (130) To compound these basic confusions, he also contends that the "media," by which he and other McLuhanites tend to mean not whole, real-people social institutions but only their technical manifestions, are becoming and will be our only reality: our very minds will be merely extensions of the worldwide media net.

This kind of view has been put so often lately that it is necessary to say why it is not reasonable, or perhaps even sane. First of all, we are creatures with a very detailed biological constitution that has powerful mental components; moreover, the psychological development of a human being takes place on a level of experience quite different from that of the media. Without necessarily being Freudian about it, our minds are much more extensions of our experiences in babyhood and childhood than they are of anything that happens to us later. We must expect the replacement of a good deal of normal parental interaction by interaction with television sets to have significant effects on our

children and on their own later child-rearing practices as adults—effects in the direction of depersonalization, passivity, and so on. Even so, the residues and constancies of our biological condition and earliest life persist; they account for the myths that concerned Jung, and in a different sense Bazin. They are, indeed, most of what enables us to continue as viable mammals, rather than appendages of machines.