New Strains, Private Needs

31—

Friendship and Fortification:

Bordeaux, Spring 1770

This prosperous city with its crescent-shaped tidal port dominates the Guyenne region, whose people have a reputation for being intractable, boastful, and extremely frank.[1] Du Coudray certainly appreciates the frankness, especially in the person of Duchesne, whom she gets to know still better now during a rather quiet and anticlimactic teaching spell here. Things go so smoothly that she really can relax and socialize. Local villages send young women, each with 60 livres generously contributed by the parishioners—nearly twice what Turgot used to give students in the Limousin.[2] One of the midwife's trainees will even become a teacher here in her own right, an extremely rare case of the job of demonstrator being passed to a woman.[3]

Primarily this stop, a watershed in her life, serves the purpose of emotional refueling. Du Coudray has been on the road a full decade; she is fifty-five. She had feared coming here, but now Boutin is gone, and it turns into a delightful occasion instead. Simply being here at last plays something of a cathartic role. In her relief she can take stock of her situation.

About many things she has been absolutely stoic. Her traveling, for example. She has looped north, east, south, west, north again, south again, west again, covering with these tours and detours well over two thousand miles. Often the dusty roads are crowded with noisy farm wagons, heavily laden donkeys, flocks of bleating sheep and full-uddered cows, and of course numerous boisterous voyagers on foot—indigent seasonal migrants, students, peddlers, musicians, traveling players, pilgrims to various religious shrines, compagnon artisans on their formative tour de France . These latter stroll in merry, often rowdy bands, scattering sometimes to distribute themselves behind or alongside carriages for shelter from the winds.[4]

The upper classes journey also, to parties or operas in other towns, adding to the general clutter and congestion.

There are no rules of the road, and frequently the many wagons and carriages jockey for position on routes too narrow even for one of them, capsizing or at the very least listing precariously, careening wildly, shaking up and injuring the passengers. More often than not there are too many creatures and things crammed into the small space, loud snorers, incontinent revelers, mothers with crying children, lap dogs, parrots, and the ubiquitous cloaks, parcels, and umbrellas. It is impossible to find a comfortable position. Horses act up, coachmen get drunk—or grow horn mad or whip crazy and decide to have a race. Wheels, axles, and reins break. On steep hills, as in Poitiers, everyone needs to empty out and walk, or even help to push the still-heavy carriage. These vehicles are uncomfortable, with their oilcloth flaps barely keeping out the elements. They have little suspension and so bump, plunge, creak, and lurch along on roads that in some provinces are little more than rocky dirt paths. Soon Turgot will make some innovations in transportation, such as lighter, spring-cushioned carriages that can reach their destinations faster by traveling through the night.[5] For now, though, because area tolls and regional frontiers are not manned after dark, the distance can be covered by day only and the traveling seems to take forever.

And all over there are beggars—crowds of wretched folks, files of them at inn doors, swarms of them in and around churches, interrupting rests, meals, and even prayers with their importunity.[6] Winter, of course, brings another set of problems, the piercing blasts of cold being the least of them. Mud, ice, floods, and poor visibility greatly increase the number of accidents on the road. Carriages fill with freezing water at every ford. Warm weather has its own drawbacks; sickness of one sort or another routinely follows a ride through pestilential, marshy plains. And there are wolves, especially in the forests that come right up to the roadside. And muggers, smugglers, highway bandits who often kill. "We advise our public," reads a notice in the Gazette de France , "that there is no substance to the rumor spread about regarding a robbery of the coach to Lyon and the assassination of its passengers."[7] The fact that carriage companies must so protest to reassure the public about safety reveals the true conditions that prevail. Much apprehension surrounds travel; passengers often prepare their last will and testament

before embarking on a long voyage, and some have been known to die of apoplexy.

Of these hazards, which are legion, of the inevitable headaches, sore rumps, bruised or even broken bones, indigestions, fevers, and terrors of the journey, du Coudray says next to nothing. She has borne them with indomitable strength of character. Her consistent demand for two weeks' rest upon her arrival in a town before beginning her class and for another two weeks' rest to fortify herself before setting out on the next trip speaks more eloquently than words of the physical and emotional toll of her travels. But she has kept her feelings to herself, hiding any vulnerability, any scars to her body or spirit. In those few instances where her letters do reveal some distress—at Angoulême, Bourges, Issoudun, Périgueux—she hastens to move on to an upbeat subject, never allowing herself to dwell on problems for long or to leave a dejected impression. Her resolution to establish her mastery of the monumental job entrusted to her has prevailed. She has not dared to falter before admirers or critics. Above all she will not expose herself to accusations of female delicacy. Perhaps she made, long ago, a conscious choice to suppress and silence her personal needs in exchange for the right to function like a man.[8]

Such spartan endurance, however, can turn eventually to exhaustion, such exaggerated self-reliance can change to deep yearning for emotional intimacy. Earlier du Coudray hinted at the loneliness of the nomadic life, the lack of opportunity to make friends. Now in Duchesne she has finally found one, and he becomes a kind of lifeline. She has discovered him just in time, because she will soon be traveling much greater distances than before. Her trip thus far has been mostly in the center of France, in pays d'élection where the intendant's influence is most powerful. But she must next reach farther afield to the outskirts, to areas with which she is not familiar, areas added more recently to the country, where the king's influence is therefore less accepted. Feelings of affection, so long pent up, now give her new strength, new energy. If she worried formerly that such ties would "weaken" her, she sees here that she can let down defenses without falling apart or losing momentum. She has confronted this city, exorcised her Bordeaux demon, opened up her heart. She can tackle the tasks of the future honestly and whole now, facing squarely her felt needs, finding balance, acknowledging a

kind of hunger she has ignored or refused to admit. It has been said that the first discipline required of a leader is that he or she have no friends, and ever since the start of her mission and the dizzying expansion of her role she has coped alone, steadied herself, kept her own counsel, and proven her professional competence and capacity to lead. But now she senses she can give free rein to these new stirrings of the soul. Her letters will be looser once the floodgates open here in Bordeaux, permitting the midwife's ink to flow more freely.

And there is another change. She has spent the last decade getting, losing, regaining, and maintaining her bearings essentially by herself. Until now this has been very much a solo performance. But here, before leaving, she adds to her traveling team a helper, a Bordeaux surgeon named Coutanceau. She still remains very much in charge, and in fact her extant letters from this period do not mention him at all. Does she yet realize or even begin to imagine the significant part he will play?

32—

The Suitor and Other Calamities:

Auch, 19 December 1770

Monsieur—Read me when you have the time.

I don't know if you remember a certain marriage proposal to my niece when I was in Bordeaux. It was a fortune offered for her. If you recall, I refused all these advantages. I saw nothing but vices in this young man, and my governess as well as my niece saw nothing but 30,000 livres. The importunities of the mother and of the sister of the young man showed they wanted to pawn off this scoundrel on me. I left even refusing from the mother a pension for Monsieur her son that she offered me to train him further. After so much stubbornness on my part, I suddenly reflected that in the event that I should die, [my niece] would reproach me for having opposed a so brilliant fortune. This idea seized me like an inspiration: What do I risk? say I to myself. His views are monstrous. When people live together, facts strike a young person more than all the advice in the world. I resolved then to put him to the test, supposing that if I was mistaken and that he has more virtue, this could make a suitable engagement. But God who gave me inspiration for this trial was good enough to surpass my expec-

tations. A letter negligently discarded and luckily found, in which he wrote to Mme his mother that he gave up the rest of his legitimate inheritance in exchange for 4 louis, reversed the fortune of my niece, and as the strongest feeling she had for him was interest, you can judge, Monsieur, that this little inclination, or love if you will, took flight immediately. But to join antipathy to disdain, a last stroke brought the whole thing down. He left for Bordeaux at the time of the fair. He stole from my niece a small lined ring box of little value but a treasure more precious to her than that of St. Denis. He came back but the box was lost, and all her jewels. What a flood of tears, what indignation against him, and what joy for me that she could regard him with all the scorn he deserved. The maid, touched by the little one's weeping and affected by the trick he played on her, could have strangled him. I must tell you too, Monsieur, that he took from my cupboard a gold knife with a little lined case of the same metal. This knife, just by chance, I wanted to show to someone, and I couldn't find it at all. Luckily for my staff, I am not hasty to accuse. I wanted to discover it before I punished, but a second inspiration came to me, and I suspected him of taking it away. I stopped all the crying I was causing in the house. I assured them I knew who. I was not wrong. The young man returned, and in a firm and confident tone, fixing him with my eyes: Give me back my knife and my case. He pulled it from his pocket, and [so] happily I did not lose these two little personal effects. Even if he had had for me only the defect of lying, for I don't think there can be a man in the world who equals him, I could never have allowed, you realize, Monsieur, all of these scenes. I could no longer stand the sight of him. However, I was charitable enough, in order to avoid a great scandal, not to throw him out immediately, and I have continued to feed, lodge, and have his laundry done since his return from the fair of Bordeaux. I wrote to madame his mother that it was not possible that I keep M. her son any longer, that his blunders did not suit me, and that, combined with the debts he incurred, I was really always alarmed. You will be good enough, Monsieur, to read Mme Rodes's letter that I'm enclosing . . . [and my notes about] the debts he had and that I paid. You will do the greatest thing in the world, you will be good enough to go find her and to settle this affair. I

see no other hope for me than this approach by you. You see what faith I have in your way of thinking. . . . I have every reason to dread on the part of the mother troubles of a different kind from her son's. It's in your hands that I put my interests. I could not do better. With anyone else I would worry that the charms of the young man's sister would outweigh the claims I could inspire, but with you I have nothing to fear. It is enough that my cause is that of justice.

I have yet another story to tell you. The subdelegate of Pau does not want me to bring my good works there. Speaking of the good, M. Esmangart [the newest intendant of Bordeaux] could oblige me if he agreed to. The états of Bigorre want two machines as soon as possible. I will send them yours, which are all ready, and will receive for them needed money right away. It is only to you that I tell this, and especially as I am about to go on vacation. . . . Answer me as quickly as you can, a thousand thousand pardons. I am, with all feelings of esteem and veneration, your very humble and very obedient servant,

du Coudray[1]

How complicated and messy things have suddenly become! So the midwife has had a young scamp under her roof since summer, when they all came and set up house here in Auch, not far from Frère Côme's hometown of Tarbes, where the monk has asked her to enlighten the region as a personal favor. Du Coudray has had her share of calamities since her arrival, including an illness she diagnoses as overwork.[2] And she relates them liberally now to her friend Duchesne.

She had written to him earlier in a dither asking for help, because she misplaced a receipt showing she had cleared a debt of 600 livres. Du Coudray is usually remarkably organized and meticulous in her record keeping, despite the fact that nothing has a permanent, stationary filing place, so she is half crazed over the missing slip of paper. Hopeful that officials in Paris will remember her reimbursing them, she tells Duchesne: "if they have the slightest doubts, I will not hesitate for a moment to be accountable." What courage it must take to make this gallant statement when she has absolutely no extra funds, indeed, barely enough to manage at all. "If you only knew my chagrin, I cannot express it to you, and that I

cause you problems just makes it worse. I will rest easy only when this matter is settled. I will take great pains not to be careless even as I experience such dismay." Meanwhile, however upset she is, her teaching obligations must be met. "I will use for this meeting the machine made for Agen because mine is soaking wet—my thriftiness in sending my trunks by water transport nearly cost me the total loss of the little I possess. That's another experience! I have many things, Monsieur, to tell you about the reception that I got here, but I am too preoccupied by our cursed matter. May the angels accompany you. I will await your response with all the vivacity of my impatience."[3]

This money matter is satisfactorily resolved by Duchesne, for it is not mentioned again. Either the receipt is found, or the Paris officials let it drop, or Duchesne is a dear enough friend to cover it from his own pocket and never say. He next does another favor and sees to it that every one of the surgeons du Coudray designates as a demonstrator does indeed get his commission—in Agen, Monflanquin, Périgueux—in spite of "all the difficulties that the cabal of the community of surgeons ordinarily gives rise to." She thinks long and hard about who best deserves these coveted appointments, so Duchesne honors her wishes and immediately expedites her orders.[4]

Now comes the biggest crisis, a matter of greed, betrayal, and a fifteen-year-old girl's heartbreak. Du Coudray's household help get very emotionally involved in this drama concerning their mistress's family and the bad seed in their midst. And who is this "niece," Marguerite Guillaumanche, who abruptly appears as such a central protagonist? She is probably first mentioned as the "apprentice" in Bourges. Had her parents, illiterate peasants from Tallende, turned her over to the midwife, or had she recently been orphaned? Was there perhaps some very distant relationship?[5] The midwife's clear understanding that preaching self-righteous sermons has no success with adolescents sounds like the insight of a seasoned guardian. Chances are they have had quite a few years together already. Is she also remembering some stubbornness in her own distant past? In any case, du Coudray, playing the maternal role, feels responsible for providing her niece with future security by marrying her off sensibly. And the money is tempting.

But the midwife, a keen judge of character, will not be the dupe of this feckless young man. The letter shows that, perhaps for lack of companionship of female equals, she has conversations with herself

in the privacy of her brain to decide on a course of action. Unscrupulousness cannot go unpunished; as mistress of the house she must educate them all. For the first time, too, the midwife confronts her own mortality. What will happen to her ward when she is gone?

There is still further cause for alarm—of which she does not speak to Duchesne, though it is deeply disquieting. The administration has decided, unaccountably, to sponsor another midwifery manual, of over 250 pages, by a doctor named Joseph Raulin. That Pau and Bayonne have just rejected her offer to "bring the good there," thus defying Frère Côme's wishes, is bad enough, but now there is this other matter of Raulin's rival publication. His Succinct Instructions . . . for Midwives in the Provinces , printed "by the ministers' orders," has immediately sold out in first edition and is already being reprinted in large numbers. What ministers? the midwife wonders.[6] Literate women in the parishes—dames distinguées —are being asked to read this work regularly to illiterate women and to engage them in conversation on the subject so that they become familiar with the art of childbirth.[7]

Raulin's book appears to be catching on fast. A new dictionary of the trades declares that his instructions are all that country women need in order to learn to deliver babies properly.[8] His text, like du Coudray's, has pictures, but they are twelve unhelpful illustrations of babies floating in acrobatic positions in unfolded wombs that look like geometric puzzles. These pictures do not compare in utility or beauty to the colored ones in the Abrégé . In fact, the rival publication has no particular merit that the midwife can discern. There is a lengthy section on religion and the crucial importance of baptism, all of which can be found in her book too, of course, but Raulin has cleverly devoted to this material a disproportionate number of pages, thus winning the resounding approval of the Paris Faculty of Theology.[9] Is this perhaps a rebuke because du Coudray's text is more secular?

In any case, it is not a good development. Of course, the new book cannot substitute for her actual teaching. Deep down she understands that. It is nonetheless an affront and a scare, for it is no mere private undertaking by Raulin, but a government-supported project. Who exactly commissioned Raulin's book? Politically, things are more turbulent than ever. The king's man d'Aiguillon was actually brought to trial this spring by the Parlement of Paris, a trial that dragged on for several months until the king held a lit de justice

and quashed the proceedings. Louis's new controller general, Terray, is doing his best to back up the crown, but the chorus of parlements protesting royal policy and appealing instead to public opinion grows louder and louder. Just last month Chancellor Maupeou declared, as Louis did four years ago at his famous session of the scourging, that parlements are nothing but courts of law, have no legislative authority, and are forbidden to act as one body. This political conflict seems to be coming to a head, and the midwife surely finds it unsettling and confusing to try to follow from afar.

Was it worth spending so much of her personal funds last year on illustrations for her Abrégé only to see the book get lost among competitive publications? She is not flattered by the idea of imitators. She does not know Terray. Is he against her for some reason? She must keep her head and monitor this situation carefully. The knife almost stolen from her just now, and reclaimed, seems in some way symbolic of her need to insist on her rights here, to jealously guard what is hers, to arm and defend herself. This knife is no mere trinket, but one of many priceless gifts given in recognition of her extraordinary efforts wherever she has taught, her legacy of successes. In her household she has confronted the foe, recovered the goods, and restored order. She must now do the same in her job, do all she can in the outside world to save her mission.

New tests, new challenges. But just how widespread is this ministerial mutiny? How much trouble is she really in?

33—

Coutanceau, "Provost" and Partner:

Montauban, Winter 1771

This pink brick city, once a hotbed of Protestantism, is now a center for the manufacture of textiles. In fact, there is so much spinning of wool and hemp, so much weaving, such a spread of these industries even into the countryside, that the peasants sometimes neglect the land.[1] Du Coudray has been impatient to get here early, ahead of the game, so she can start making machines before beginning her lessons. In Auch she was sick for a spell;[2] now she has much catching up to do filling numerous back orders. This is, too, a way to get her mind off her worries. She tells Duchesne she is eager "to put myself to the task."[3]Ad operam is indeed a guiding principle for the midwife; lying fallow depresses her, and work seems therapeutic.

We now hear more about the sixth and newest member of her band, thirty-three-year-old Jean-Pierre Coutanceau, a surgeon from a medical family in Bordeaux.[4] Somehow in the short period since he joined them he has assumed a very special role. Du Coudray is for the first time admitting that she needs assistance. Although young enough to be her son, he is treated as an equal, a colleague. She obviously already admires and trusts him, for she sends him to do a course in her stead a bit to the north, in cozy, affable Cahors.[5] They give Coutanceau the perquisite of a few hundred livres that usually goes to the midwife. The two seem to have agreed on this, although it is not clear if he contributes the money for shared household expenses or if it is his exclusively.[6] Du Coudray is regarding him still more appreciatively since the fiasco with her niece's suitor. She counts on Coutanceau, who is as steady and reliable as the younger man was shiftless, calls him her "provost," and passes on to him many demonstration and teaching responsibilities. Having an intelligent and loyal adult along has to be an enormous comfort. Perhaps he can become a permanent fixture, an extra pair of hands she will be able always to rely on.

Such have probably been her thoughts lately, for more and more she treats their relationship as a partnership. Is she instinctively insulating herself from adversity? Never before has she given a helper this kind of status, but now she hesitates to proceed alone. She is heading next into the south of France, an area full of conservative pays d'états —Pau, Toulouse, Foix, Perpignan, Montpellier, Aix—where having a male surgeon partner might indeed be an advantage.

But an odd thing is about to happen. Even with Coutanceau's company and cooperation, she will be repeatedly cast out, forced to wander as if in the desert. She disappears now from public view for over a year, her mission seemingly suspended, her whereabouts entirely unknown and unmarked in the official correspondence.

34—

"Happy As a Queen":

Grenoble, 16 June 1772

Monsieur—

I write to you almost from the other world. I am in Grenoble happy as a queen: a charming intendant, a secretary worthy

of him, inhabitants full of gratitude, and lots of intelligence in the subjects. This has made amends for the ennui in which I found myself in Toulouse, traveling calmly along across six provinces in my carriage. Can it be imagined, I was turned away. I do not know what will be my destination, if I will go to Trevoux or to Besançon, but at least let me find there the same zeal and readiness to receive me [as I find here]. I am writing to M. Esmangart to ask that he please give to M. Brochet, surgeon in the city of Périgueux, the commission I had obtained for M. La Combe who just up and died on me [qui s'est laissé tout bonnement mourir ]. I am not telling the intendant that I am urged to do this by the demoiselles Bertin, but I am asking you to second me so that such supplicants not be disappointed. So oblige me, Monsieur, and give it your attention as promptly as possible. I count on all your kindness toward me. A ton of fond wishes to Mme Duchesne, please, [and] to your sons. You will favor me with a reply as soon as you've expedited this matter, so that I may report to the demoiselles Bertin. I am for life, with feelings of pure attachment, Monsieur, your very humble and very obedient servant,

du Coudray[1]

Where has the midwife been? For thirteen months she sank from sight and Duchesne has heard not a word. In March 1771 she was still in Montauban,[2] by April 1772 in Grenoble. But in between she had been compelled to keep moving, had been unable to stop anywhere to teach. It was certainly not for want of trying. There was some major problem in Toulouse; as she reports to her friend now with considerable shock, several places actually refused her. Narbonne did. And Montpellier.[3] The latter is perhaps not surprising, for this city has a very strong medical faculty, the great rival of Paris; they do not believe they can use any help from this woman trained in the capital. So there she is, reduced to a fugitive! It is so shameful that she chooses silence rather than attempting to tell Duchesne the details of what happened.

But we can conjecture. Throughout late 1770 the parlements had grown flagrantly disobedient and provocative. On the night of 19 January 1771 the chancellor Maupeou effected a coup, a complete purge of the law courts, banishing the recalcitrant magistrates to remote, desolate corners of the country. In June d'Aiguillon, so hated

by the refractory parlements , was made secretary of state for foreign affairs. Maupeou, Terray, and d'Aiguillon now constitute the so-called triumvirate of ministers, determined to see that the king's will be done, that his edicts be imposed and forced into law. In the eyes of many, not just the privileged nobility, Maupeou's maneuver was an act of naked despotism, and the royal midwife almost surely suffered the resentment and hostility directed toward the monarch.

There were other reasons for her rejection in these southern regions. The intendant St. Priest, in April 1771 and again in November, put du Coudray off as politely as possible, referring to bureaucratic complications with the powerful états , suggesting she try again sometime in the future.[4] These areas are in any case notoriously inhospitable to female practitioners. Elizabeth Nihell's fierce attack on accoucheurs has just been translated into French, with an updated diatribe against the Frenchman Levret who advocates forceps. The Midi apparently makes no distinction between such belligerent feminist midwives and du Coudray: none of them are welcome. Despite seeing that her slightest attempt to alight provoked such antagonism, the royal midwife was too proud to bow, scrape, and explain herself.

The setbacks during this year of enforced leisure, when she could gain no foothold anywhere, must have raised the specter of her whole mission fizzling ignominiously. But she does not permit herself to wax maudlin in letters. In fact, it would seem she wrote no letters during her wanderings, and resumes contact only now after the humiliation is over and past. Even today she gives just the sketchiest picture of those many months. She will not be seen as the plaintive exile. Some things, some feelings, are beyond description. If they go unreported, however gravely wounding, they can lose their edge and fade away.

Du Coudray somehow again now musters all her ardor for Grenoble. She has been in this capital city of Dauphiné for two months, where the locals, even the most rustic, are known for friendliness to outsiders.[5] Technically this is also a pays d'état , but the états have not met since 1628 and a much more progressive atmosphere prevails. Here the king's intendant, Marécheval, has considerable influence. He has been truly excited about du Coudray's arrival, writing before she came to both lay and clerical administrators in surrounding towns that they "must be convinced in advance of the utility

cities can derive from her intelligence. It should interest citizens of all orders." An avis has been printed up and circulated, explaining how her mission came about. It is based on Le Nain's Mémoire but much more succinct.[6] Perhaps because of the recent hiatus in her teaching, Marécheval believes it wise to reintroduce her; she has not been lately on people's minds. In response, numerous villages have sent students to take advantage of "this important school."[7] The midwife trains some very talented women here, and being appreciated again is sweet.[8]

Even with Duchesne, du Coudray prefers to display her proud moments and keep low moods to herself. Now that her routine is picking up again she feels like reconnecting, sharing her feelings but also reestablishing her businesslike mode. Duchesne takes care of the favor she asks for the surgeon protégé of Bertin's daughters.[9] She has, of course, much to thank the former minister for; without his help all those years ago her mission might never have gotten going at all. Du Coudray is feeling so much better that she can even speak flippantly of the inconvenient death of one of her demonstrators. Finding replacements for her trained disciples is at best a bother. She is regaining her sense of humor. And she again pushes, however charmingly, for what she wants, returning time after time to the favor she needs and insisting on a reply so she'll know it has been taken care of. Her epistolary pressures are in full swing once more. She is back to her old tricks.

Politically now too, in the summer of 1772, things have settled down considerably. The royalist "triumvirate" has been in power for some time, and the parlements have been subdued and replaced by courts more cooperative with the crown. D'Aiguillon, the new minister of foreign affairs, seems sufficiently impressed with the midwife's mission, and especially with Coutanceau, that he grants him permission, even though he is not a military man, to don the surgeon-major's uniform.[10] It was good to bring him along after all.

35—

Networks, Newspapers, and Name Games:

Besançon, 16 November 1772

Crisp, confident, and vigorous, the midwife has been executing numerous tasks in this capital of Franche Comté, another erstwhile pays

d'état, land of plentiful, exquisite fish, superb big game, abundant wheat, and wine. But the roads here are known to be dangerous, too closed in by menacing woods, too narrow and rutted, too overgrown.[1] As a consequence the trip from Grenoble, not so far as the crow flies, took an inordinately long seven days.[2]

Du Coudray had pushed herself with unusual aggressiveness on this intendant, La Coré, writing in May from Grenoble with a detailed enumeration of her talents. Dreading another idle spell, she is resolved to preserve her new momentum in a long, strong trajectory. In case La Coré shares the prejudice against accoucheuses that she encountered in the south, she stresses her connection with surgeons especially. The awkwardness of the letter shows that she is not relaxed. She has, it seems, almost gone to Besançon once before. This time the trip really must materialize.

I do not doubt that the sentiments of humanity that you have always held will have you learn with pleasure of my proximity. . . . Your reputation inspires me. . . . I have made such a round of visits but despite the postponement I never forgot about you. I am in Grenoble. Everyone in this province supports the beneficence of M. de Marécheval. He is loved, you are, Monsieur, and you are everywhere, and I can do the same for yours. I thought of doing the Lyonnais, but the impossibility of M. de Flessel setting up this establishment only hastens the satisfaction of being with you. . . . My brevet . . . removes all difficulties. I enclose a recommendation from the surgeons of Rochefort that might make yours interested in seeing operations that so much resemble nature. I have here, as I have had everywhere, a great number of [surgeon-students]. I will await your answer, and I will be painfully afflicted [douloureusement pénétrée ] if obstacles interfere with your desires and with the eagerness I have to support you.[3]

Du Coudray makes it hard to deny her. Plans have not worked out for her to teach in Trévoux near Lyon,[4] so she simply can't let Besançon fall through, for the memory of her year of rejection still smarts. She is in luck, as it turns out. The subdelegate of Besanqon, Ethis, having heard the highest praise for the midwife from Grenoble,[5] is very ready and willing to accommodate her. They have a good working rapport, though no close friendship. She has told him bluntly, "I need time to rest before starting."[6] Without such acknowledgment of her limits, she would soon be irretrievably spent.

Since mid-August she has been living and teaching in a house

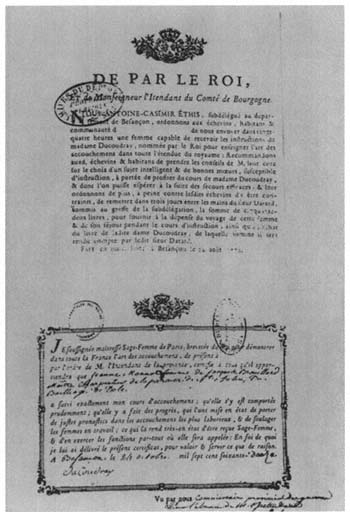

on the rue St. Vincent, not far from the square in front of the governor's palace, where there is a fountain in the shape of a nude seated woman with water spurting from her breasts. Ninety-four students have come, but Ethis and du Coudray herself have had to advance nearly all of them money, as their parishes fell far short of covering their living expenses.[7] This is unprecedented. Ethis will later be obliged to go in hot pursuit of the funds from these delinquent villages, threatening them with lawsuits and arrests if the responsible parties do not pay up.[8] The midwife, however, knows full well she will never again see the sums she "lends" these poor women. Certainly she needs the money, but she is also aware that they are far worse off than she. Besides, they are an investment for her, in the immortality of her life's work, in the future (fig. 8).

Something else is new here also. A particularly intense selection process has taken place, with many letters exchanged between the midwife and the parish priests. Usually the students are all lined up for the midwife beforehand, but here the priests consult her on each choice, addressing her variously as "the very deserving dame du Coudrez approved by the King," "midwife proposed by His majesty for instructing," "established by the King," "his Majesty's deputy in the whole extent of the kingdom," "midwife by special appointment," expecting her to be intimately involved in the shaping of her class. One girl is "sheepish and timid" and "has never left her village" but is being sent anyway, "informed of your consideration and kindness toward this sort of person." Another painfully shy girl is nevertheless "rich in character." Du Coudray interviews them all, then sends off cheerful and efficient notes to Ethis telling him her decisions. In one case she has to explain to "surprised" town officials why she rejects a practicing midwife in favor of her untrained daughter; she wants fresh, open, malleable minds that do not need to unlearn bad habits first. Only one pupil is supposed to be sent from each town, but the curé of Héricourt, embarrassed because his best volunteer is Lutheran, begs du Coudray's "dear person" to accept a Catholic girl as well, to balance things out. Protestant midwives are technically against the law, for it is feared that they will not baptize babies, yet in this region there are many of them.[9]

One particularly supportive priest is helped by a good word du Coudray puts in for him with the cardinal. In return she asks for his assistance making certain that her students get clients and are

Figure 8.

On top is a call sent by the subdelegate of Besançon on behalf

of the king, recruiting suitable midwifery students from each village, to

be carefully selected by the parish priest and financially provided for during

the lessons. Below is a typical diploma awarded by Mme du Coudray

at the completion of the course.

not squeezed out of their rightful job. She fights aggressively on this point, to make sure her system of birthing prevails. Priests in each parish, she suggests, should refuse to recognize any midwife at baptisms except the one trained by her. Mothers so obstinate that "they prefer to die in the hands of ignorant women than to call to their aid the new one" can choose an old matron if they wish, but in du Coudray's system both the mother and the matron will be liable five sous each to pay for the baptism. A shrewd boycott indeed. "Shame and stinginess together" will soon win the village women over to the new trainee. You must sometimes, she explains, force "the good" on a public too backward to recognize it themselves.[10]

The midwife develops a special closeness with her students here in Besançon, perhaps because she protects so strenuously their right to practice. She hears about their bad livers and hearts, traumas with their children, and always their immense gratitude to her, for everything. "As for me, my dear lady," writes one succinctly, "I will never forget you."[11] Another thanks du Coudray for being such a sympathetic listener and sends her a gift she received at a noble baptism. This woman is falsely accused of a crime, and complains that she is at a great disadvantage because her adversaries are "rich and well protected." Her honor and all her earthly goods are at stake, and she begs du Coudray to intercede in her behalf with the intendant, "for which I will not stop being grateful as long as I live."[12] The teacher is as sensitive to her students as she is harsh with the old matrons. The hardship she must cause these "other" women, who have practiced for years and are now being pushed aside by girls with a couple of months' training, is nowhere in her thoughts. Saving babies is her sole goal, and creating a new set of victims in the process does not appear to deter her.

That she is noticeably hardened against the older matrons here might be because she finds more than the usual birthing atrocities in this region. A supporter of hers will later explain that she beheld

horrible spectacles devised by ignorance and cruelty to deliver a woman with a malpresentation, the account of which makes one tremble. She was called to a poor peasant, exhausted by a long labor: they had sat her on a chair with a chopping block under her thighs, on which they cut with a butcher's knife all the emerging parts of a live child; one stepped on the head and pieces of limbs of this child upon entering the room, and to pull the rest of this victim out of this unfortunate mother's body, they tugged and tore it with handles of soup

ladles and hooks from a scale by turns, under which the woman expired in this sad moment.[13]

Even du Coudray, exposed constantly to upsetting sights, found these abominations too much.

The local newspaper has just carried two extensive articles on her lessons, which are credited with having "ended . . . abuses so contrary to the public good, prevented the shedding of an infinity of tears . . . avoided the extinction of families." She is working longer hours than ever, teaching from eight in the morning to noon and then from two to seven in the evening, with only Sundays off. Including surgeons, she has 120 students. The reporter, waxing rhapsodic, portrays a saintly midwife, nearly beyond recognition.

Mme du Coudray shuns praise. Her modesty cannot admit it. Let us just say then that she taught with much order, neatness, and precision. Her method employs no hooks or other metal instruments, which are alarming and dangerous, but only the dexterous hand. She has as assistants M. Coutanceau, of ample erudition and experience, and Mlle de Varennes, faithful follower of Mme du Coudray her aunt. All the students, male and female, filled with gratitude, praise the seigneur for having given them this favorable opportunity, and to show him thanksgiving Mme du Coudray in her rare piety thought it appropriate to say, last Sunday . . . at 9 in the morning at the Capucins, a mass with offering of blessed bread. . . . She took the sacrament of the Eucharist along with most of her students.

The intendant, the newspaper reports, has generously prepared and presented special leather-bound copies of the Abrégé to each of the graduates.[14]

The second article laments that more men are not willing to study with du Coudray, mistakenly thinking they have nothing new to learn. These men should "banish such vain politics, the fear of blushing," and "base sentiments of misplaced pride" and open themselves to enlightenment.[15] The dean of the University of Besanqon's medical faculty, who attended the midwife's course, adds his voice too: "We see only too often enormous mistakes made in childbirth by the very ones who call themselves experts in this profession."[16] This kind of blindness and stubbornness on the part of men, coupled with the rashness of untrained matrons, the dean observes, results in the kind of horror scene the midwife witnessed in the region.[17]

These press reports raise several questions. First, how has Coutanceau been persuaded to stay on permanently as part of the crew? The midwife has been turning over her gratuities to him since Bordeaux. Was that all the coaxing he needed, or did he have other reasons for wanting to stay? Second, why does du Coudray suddenly style her "niece" as "Mlle de Varennes"? Maybe it is part of some aristocratic role-playing to enhance the prestige of the group and wipe out memories of the bruising year of rebuffs. Du Coudray, after all, has seen fit to assume for herself a surname complete with noble particle to suggest a lineage of status, and the younger woman is supposedly her relative. A third question concerns why the midwife thinks Besançon is worth a mass. Is it because, just now when she is eager to wind things up and leave, the province turns out to have no money whatsoever to pay her? A display of piety might help. It certainly didn't hurt her rival Raulin get a lot of support and attention for his birthing manual.

Today, chafing at the bit, she writes to her contact M. St. Etienne at the projected next stop, Châlons-sur-Marne. By happy coincidence, she somehow already knows and likes this man very much. Did they perhaps befriend each other during her hard vagabond year when he was on another administrative assignment in a different region? In any case, he is about to take Duchesne's place as her best confidant. She seems positively giddy at the prospect of their imminent reunion. Delayed here, she must wait a full month for the Treasury to be replenished so she can collect payment for the many machines she is leaving in the Besançon region. "I cannot wait to see you again, and without this reason I would have left immediately. I embrace you always, while waiting to be able to tousle your head, goodbye, hello. I am very respectfully, your little servant, du Coudray. P.S. Dear me how we will gossip!"[18]

Is du Coudray actually flirting? For a woman nearing sixty, this petite servante sounds positively girlish. It is impossible to be sure. But St. Etienne is clearly a kindred spirit for whom she feels enormous affection, and she is bursting to tell all. Periods of relief, release, unwinding seem essential to her now to punctuate the grueling routine. Bonds created by chatter, laughter, good times, hilarity even, have become vital necessities. And between her and St. Etienne there is something very special. This is her most ebullient letter to date, a complete change from the self-conscious gravity of

some and the breezy efficiency of others. Whatever their relationship is, here in anticipation of their meeting she expresses a boisterous, almost visceral joy.

36—

Flirtation in Champagne:

Châlons-sur-Marne, March 1773

A dalliance perhaps? Certainly an especially good time. Sharing the limelight now with her niece and M. Coutanceau, the midwife has spent the winter in this walled city with its shady canals, situated in a large plain in Champagne.[1] Rouillé d'Orfeuil, the intendant, is solicitous, though he is away on rounds and not here to supervise things himself. His official, St. Etienne, has taken over in his absence, adding several incentives to attract students. The first two—the offer of free lodging in Châlons and an assurance that extra earnings from the practice of their new art will never be subject to the taille —have been tried before, but the third—exempting their husbands from the hated corvée , the enforced labor on royal roads, as long as the midwives remain professionally active—is an innovation.[2]

Nevertheless, things have not gone entirely smoothly. The fanfare has upset one combative surgeon, who casts aspersions on du Coudray's book and its "sloppy" way of "laying the foundations of this establishment." Luckily, this attack does not sway Rouillé d'Orfeuil from his loyalty to the midwife and her enterprise.[3] But there have been other difficulties as well. Some curés have had trouble recruiting students; one who could not find anyone to volunteer sends a compensatory poem instead, lauding the intendant for his farsightedness on this important issue.[4] The problem in gathering recruits for the courses is perhaps related to how hard women work the land in this area, where the chalky soil would form an almost solid crust, broken only by an occasional black pine, were it not for the combined power of men and women.[5] Those students who do come, though, get printed certificates on which the promise of tax exemption is clearly spelled out.[6]

Du Coudray is so happy. Deeply appreciative of Rouillé d'Orfeuil's support, she writes to him: "One feels in this province all the good you do for it. I will neglect nothing, so that your kind intentions will be carried out. I only regret that I will not have the hap-

piness of seeing you."[7] However much she likes writing and receiving letters, the midwife also looks forward to meeting people in the flesh. In this case, however, there is ample compensation for the intendant's absence. St. Etienne is helping with everything, rounding up more students, selling machines, turning a lackluster beginning into a smashing success for du Coudray. She can relax. He is one conquest already made.

Beyond the likelihood that St. Etienne is unmarried—her subsequent letters to him never include greetings to a wife, as is her custom with Duchesne—we know very little about him, except for the unprecedented coquettishness he inspires on the midwife's part. Nowhere else in her extant letters does she speak or behave this way, loosened up, even playful. He and only he, in her extensive correspondence, will be addressed as "Monsieur and Dear Friend." Perhaps a romance really does blossom between them. But if so, it never sways du Coudray from her path. Aeneas may have slowed down for Dido, but the midwife does not seem to skip a beat. Whatever the nature of this interlude, it gets transformed by her into yet another business relationship, does not make her stray, stay, or even delay. Really, St. Etienne is far more of a facilitator than an obstacle, helping her achieve and indeed surpass her goals. More and more she sees that mixing pleasure with work enhances her effectiveness. She need not take it all so terribly seriously.

And now things are picking up, getting lively. Surgeons in surrounding towns fight for the chance to become her demonstrators, hearing of the midwife's courses through public announcements at the meetings of their guild. Male pride and professional rivalry ensure that initial reactions are rarely enthusiastic, but in the end many compete to be chosen, and sometimes there is acrimonious argument and even foul play as they vie for the coveted assignment. The nearby city of Troyes is a case in point. One Picard, a master surgeon, had with a gesture of irritation read out loud the notice of du Coudray's coming in a scornful tone, stressing that anyone traveling to Châlons to attend the course would lose valuable business on the home front and that, in any case, it is indecent and demeaning to be taught by a woman. Having elicited the desired negative reaction, Picard was dispatched to the mayor of the city to report that nobody was interested. Once there, however, he betrayed the fold, taking advantage of the interview to slip an idea to the town officials:

his own son-in-law would be a willing candidate. Hearing of this deception, the community of surgeons nominated a member of their guild, M. Simon, as well, and Troyes was eventually obliged to send both men. As things stand now, though, only one can officially be named demonstrator. Simon, eager for the designation and disturbed by the irregularities of the procedure, has reminded the intendant that he once sent him some verses, for which an unspecified return favor was promised. Has the time come to make good on that promise? But Picard's relative is a favorite of the subdelegate of Troyes, and in the end it is he who gets the commission and the machine, though only after an intense and ugly struggle. Similar dramas are played out in many towns. Sometimes surgeons literally come to blows in their scramble to be chosen to help bring du Coudray's science to the villages.[8] The Affiches, annonces et avis divers de Reims et de la généralité de Champagne reports that some surgeons even join the classes for women to reap additional profit from the "rare talents" of the aunt and niece and the "precision" of Coutanceau.[9]

All in all the stay here ends up a huge hit, thanks to the extra help and encouragement from St. Etienne.[10] Letters from fans inundate du Coudray, and do not abate after her departure.[11] Rouillé d'Orfeuil, who has already given her numerous silver presents as tokens of thanks,[12] also sees to it that the towns in his jurisdiction order twenty-three of her machines—a record for one region and a handsome profit for her.[13] Now that such large numbers of these mannequins have to be produced, du Coudray has begun to make a less expensive, less elaborate version in linen, for which she charges only 200 rather than the previous 300 livres. She is working on other shortcuts, alternative ways of fabricating the models more quickly. She once dreamed of such gigantic orders; now she recognizes that they sap her strength even as they replenish her purse.

Her purse has been replenished in yet another way. A new, third edition of her Abrégé has been published here in Châlons-sur-Marne, in response to growing demand for such birthing manuals.[14] Du Coudray realizes she must keep hers available in abundant quantities, saturating the market so that the increasingly popular rival book by Raulin does not jump in to fill the vacuum. Once unique of its kind, her simple text is serving as a model and has inspired a fashionable trend, for others quickly see, as she did years ago, that a new public requires new kinds of reading matter, books that marry word and image and serve as ready reference.[15] These days du Cou-

dray must defend her literary and professional property as never before.

37—

"I Cost Nothing":

Verdun, 17 June 1773

Monsieur and Dear Friend,

Finally, thank God, my course is finished, and the machines also. We had 108 students; we are all in collapse. Our sojourn because of our bad health was altogether disagreeable. And by another heap of bad luck I still don't know when I can get out of here. On the faith of what M. de Calonne told me, that all was arranged with M. de la Galazière and the exchange made between them . . . for Verdun . . . [and] Nancy . . . , CRASH [patatras ] all plans are broken. I have had to write to Flanders and I await the response, which only redoubles my ennui. I am taking a little trip of four days to go to Metz. It is not so much, my handsome man, for my amusement as for my curiosity, to see the machines that the magistrates ordered from Paris. I know they are not worth much, for in spite of this expense the city also bought mine, but if there is something good about them, and that I don't know, I swear to you I will always take it. That's the purpose that drives me there.

Just imagine, Monsieur, that I am not yet paid by Besançon, isn't that shameful? Anxiety is beginning to overtake me. It is awkward to have my rest time now, and yet because of delays of this kind, to find myself in embarrassed circumstances. Again, if you were in charge all would be well.

The machine for Ste. Menehould will be delivered by the coach to the address of the magistrates. The surgeons and these men seem to want it, for they write me of their impatience to receive it. As for the two others, they will go to you. About the one for Rocroy, if I were to believe M. Lamarre, it would be destined for him. He claims to have gotten news that M. d'Orfeuil would intercede for him. This matter will be decided. But in truth, I fear he confuses his dreams for reality, for I have no more faith in all he tells me than in my slipper. But this machine will do very well in the hands of one M. Girardin, surgeon at Rauvay near Rocroy, who seemed to us a real man of

honor. He would have an additional advantage, for he has his son with him . . . [and] one or the other can go to Rocroy to give the lessons. By the way, the woman from Montfaucon came to find me. This poor woman has already done nine deliveries with the greatest possible success, but she has not yet received her book. And I told her I would ask you for it right away. I embrace you with all my heart, as well as dear Miss Frinon. Fanfan does too. The rest of my suite present their respects to you. I don't know if I will take with me the dragées [sugarcoated almonds] I am amassing. I am fed up with Theuveui. He is incapable of profiting from all the good I could teach him. This profession is not made for him with his extreme negligence. Goodbye, hello. Love me always. You owe it to the sentiments of friendship and gratitude with which I am, Monsieur, your very humble and obedient servant.

du Coudray[1]

Neither springtime nor the loveliness of this windy city on the river Meuse can cheer up du Coudray's household, not even the aniseed preserves so reputed in this region.[2] Everyone is exhausted, sick, and as always, short of funds.

The intendant Calonne has put his quite competent first secretary M. Cantat in charge, and the lessons have drawn a huge crowd and lasted four months.[3] But the midwife is uncomfortable. She does not trust Calonne. He has, after all, allowed the nearby city of Metz to purchase some machines from another source, and he endorses an unknown surgeon there rather than one of her disciples.[4] She thinks he is faithless and a poor planner. All this she confides to St. Etienne, and the letter writing does seem to cheer her. The act of composing these missives is somehow cleansing. That they are often dictated through a servant/secretary in no way diminishes their spontaneity or candor; du Coudray has no secrets from her staff. She sorely misses the efficiency of St. Etienne, and even more his caring and sympathetic ear. Is "dear Miss Frinon" perhaps a housekeeper, a maiden aunt, a younger relative of his who has befriended the midwife's niece (now referred to affectionately by her nickname, Fanfan)? The friendliness of the families and the openness with which du Coudray teases—"my handsome man," "love me always," "I embrace you"—suggests there was nothing illicit about their relationship. Rather, it comforts her to be reminded of past good times.

And she has many more complaints to unload! She is unhappy with one of her surgeon trainees and may leave him behind. He is a slacker, it seems, and it is an impossible burden to have in her household someone who does not pull his weight. Furthermore, the future hangs in the balance, for she does not know where to go next. They are all stuck here, marking time, so she busies herself by delivering lots of babies and gathering lots of dragées, the traditional compensation for such work.

She has been misled by Calonne into thinking that all was worked out for her to move on. Now, instead, she has to organize everything herself. She will soon, while waiting for things to be decided, write to Amiens, attempting to coax the intendant Dupleix, who she mistakenly believes to be stationed there:

The good that I do for humanity . . . is perhaps known to you, but in case you haven't heard, I do not doubt, (knowing your reputation), that you will seize with enthusiasm the offer I make to you. . . . The brevet with which I am honored authorizes me and makes me safe from the cabal that surgeons often instigate; anyway, the most zealous intendants don't even consult them. You will see, Monsieur, that I cost nothing. The King, who desires that this establishment be set up everywhere in his realm, has taken care of my honoraria. . . . I hasten to do this good [faire ce bien ] only as long as all cooperate with me and when those in power understand its full price, knowing how to animate the master and the disciples . (emphasis mine)[5]

This terse, self-congratulatory sales pitch reveals her impatience at having been victimized by administrative indifference before. She is, as she puts it, "the master" "I cost nothing" is of course not quite true, but she wants it believed that His Majesty keeps her in cash. What an enormous effort to explain her mission over and over again to these intendants! She must labor constantly to keep herself prominent in their thoughts.

That she has competition for her machines now is just the latest, newest problem, another major setback. Mlle Bihéron has of course been making anatomical models in Paris since the 1750s, but these are of wax. Now there is a Mme Lenfant on rue des Mathurins, who has begun to advertise in the Paris papers models made of cloth, "appropriate for surgeons, accoucheurs , and midwives to give them practice in the maneuvers of delivery. The natural proportions both

in the pelvis and in the fetus are exactly observed."[6] Du Coudray tells St. Etienne gamely that she is curious to observe these mannequins purchased from ateliers in the capital, to learn some tips, perhaps ways to cut costs. Her interest is predatory, for this item, of which she has been the main producer if not the sole inventor, now seems on the verge of becoming easily and more cheaply available. First there was a rival textbook, now a rival machine. Not only Bousquet in nearby Metz, but surgeons in southern areas where she had been turned away have started using these, buying them from manufacturers of dolls and automata in Paris who readily adapt to filling special orders.[7] Things are beginning to slip out of du Coudray's grasp. What has become of her exclusive rights? Feeling beleaguered, she obsesses in her letter about a copy of her book for one of her students in Montfaucon, a reminder of her authority, her authorial voice.

The psychological importance of her letter writing cannot be overestimated. What ultimately puts the midwife back on track again and again is her own inner sense of meaning, reanimated in the act of writing. It provides her steadying ballast. Here, for example, du Coudray works herself into a stronger managerial mode when she speaks of the distribution of her own machines. By weighing and judging the relative merits of the men she has trained and their suitability to become keepers of the mannequin, the midwife boosts herself in her own eyes. A large number of people constitute her network, and she is the final arbiter of their worth. This kind of affirmative reminder works as a tonic, regenerating her sense of purpose. The increasing momentum, the racing of her pulse, is almost palpable in the letter to St. Etienne, as she proceeds from a recitation of her problems to a renewed activist focus on her raison d'être and on what needs to be done. Her correspondence is her best medicine.

If only the men of Besançon will finally pay her, and if only the men who determine her next moves will organize themselves, she can get going again.[8] Instead they are negligent, forever getting their signals crossed. A full seven months ago Controller General Terray, in an apparent act of support for du Coudray, had authorized the purchase of eight or ten machines for the cities around Besançon, volunteering that his tax receivers would pay if the municipal officers refused to.[9] The midwife produced the machines in good faith,

but neither one group nor the other has come forth with the funds. Typical. She, on the other hand, gets things done, sticks to her obligations. In some sense she sees herself as more manly than the males with whom she deals. Her classes are methodical, her students amenable, obedient. One letter recommending someone for her course assures her that the pupil "will be a woman submissive to your orders, with whom you will be pleased."[10] Le Nain's Mémoire was careful to speak of the "mistress" and her disciples, but du Coudray transforms the phrase and calls herself the "master" (maître ). She is on a par with male authorities any day. Indeed, she functions a good deal better than many of them do. Why must she dissipate so much of her energy hounding debtors and incompetents?

38—

She "Partakes of the Prodigious":

Neufchâteau, Fall 1773

Things have worked out after all for the Lorraine. Traveling past firetrap houses, wood-roofed with no chimneys, from which smoke escapes, if at all, through ceiling holes or window slits, the midwife has also seen, in the Vosges area, huts sunk into the earth, damp comfortless dwellings with the inevitable dung heap by the door. Many of her students, she knows, will come from such homes. Neufchâteau itself is a small cloudy town where, despite their love for baba au rhum and madeleine cakes, the people are reputed to be cold and taciturn.[1]

For a while du Coudray had not known where she would end up. Mistakenly thinking the intendant Dupleix is in Amiens, she wrote to him from Verdun attempting to arrange a visit. He, however, turns out to be in charge of Brittany now and received her forwarded letter in Rennes, much farther away. Dupleix fervently wants her to come there, and makes a note to himself: "We must send a courteous letter to this woman that I know by her great reputation. This establishment would be very desirable, but the means are not easy. Promise her that I am looking into it."[2] Meanwhile her original plan nearer by materialized and she wrote again to Dupleix: "The intendant of Nancy, having had I think a letter from the Controller General, finally does want me, and I leave to go to Neufchâteau, which is the center of French Lorraine. The minister must write also

to the intendant of Strasbourg, who set his mind against [my teaching there] last September. As for you, Monsieur, I will write that you don't need it [right now]. I will be honored to let you know what happens, and although I have pledged myself to travel only step by step, as much for my health as for the considerable costs of my voyages, I will spare neither one nor the other to fulfill your wishes as promptly as possible."[3] Thus the midwife lines up a potential future engagement. With Dupleix duly informed by this little geography lesson, blandished by the sacrifice she is willing to make, and satisfied to stay on hold for a while, du Coudray has now come to Neufchâteau, traveling through the town of Domrémy-la-Pucelle, where Joan of Arc was born. Does she ever fancy that her own heroic mission to save France bears some resemblance to the efforts of that maiden?

Contrary to the midwife's advice, local lords and parish priests have sought volunteers among the ranks of matrons already practicing. Du Coudray knows this is stupid. One, for example, who has delivered hundreds of babies, protests that she is too old for the aggravation of having to take lessons and "would rather stop practicing midwifery than go." A second is so preoccupied with her duties at home that she could not concentrate, would have to rush back to preside at births of village women in her care. One curé after another, running into obstinacy on the matrons' part, reports that the recruiting efforts have been "to no purpose," "a pure waste of time," "not a single one wanted to follow [our invitation]."[4] Du Coudray had predicted this in a letter they initially ignored, and when they finally turn to her advice, ninety-two untrained but willing girls are brought in from surrounding towns and many more from Neufchâteau itself.[5]

They seem to stick together a lot even when not in class. Some stay with aunts and sisters, some at inns—two at the Poule Qui Boit, eight at La Croix d'Or—others in private rooming houses run by merchants and widows. They cook for themselves to economize and to keep each other company at mealtime, when they might feel especially homesick. A few are grouped together in a hospice run by the sisters of charity.[6] The surgeons who arrive next for their class are a varied bunch without the same cohesiveness.[7]

One of the midwife's male students here is none other than the surgeon-major M. Saint Paul, who has been a devotee of hers since

her stop in Poitou nearly a decade ago. He pours out to a friend a cascade of heartfelt praise. One must really see the superb du Coudray in action to believe the miracles she can work! Her lessons "surprised and enchanted me . . . realistic demonstrations . . . as well as happy and unfortunate positions that the practice of delivery presents. . . . All this chaos, hidden to the eye and often to the touch, is intelligibly disentangled by her, so much does her vast knowledge partake of the prodigious. Also the intendant of the Lorraine, who is gifted in general understanding of all the sciences, evinced surprised admiration at the demonstrations he came to see her do. He heaped upon her, in my presence, the most flattering eulogies, in my view most deserved."[8]

On the last day of the course, du Coudray is honored by the singing of a musical mass for all her successes with her 150 female and male students.[9] She amasses the familiar stack of thank-yous from adoring trainees pledging to be "eternally her student," and now M. Coutanceau is also gathering a following.[10] The midwife has enjoyed here a sense of settlement, an agreeable calm. There is much socializing. The intendant, La Galazière, has outdone himself to enhance du Coudray's comfort. And the subdelegate of Neufchâteau, M. Rouyer, is a friendly man with a gracious wife who opens their home to the midwife and her team, makes her welcome, and introduces her to his friends. She will remember his kindness and hospitality for a long time and will still be merrily reporting back to him about her odyssey many years later.