PART FOUR

COSTUMES IN RELATION TO THE PRAYER DRAMA

The Sources for a study of the various costumes are fourfold. Individual garments may be seen and minutely examined in many museums and private collections. Long and exhaustive accounts of dances and rituals have been published in scientific reports dealing with anthropology, ethnology, and folklore. The costume descriptions are often detailed, and much can be learned by a comparison of the reports with photographs and illustrations. Indian artists have provided sketches and paintings which are very informative, particularly when carefully checked with authoritative reports. Carved wooden images, the so-called "kachina dolls" (pl. 2), afford valuable information in regard to the concept of masked mythological personages.[1] Most of these images come from Hopi and Zuñi, where they can be seen hanging from the roof beams in the pueblo homes. Several collections have been made and are accessible in museums. The dolls are carved from the root of the cottonwood tree and the art is of a primitive kind. "The representation of the body is subordinate to that of the head, often appearing as a shapeless imitation, but more generally as a conventionalized figure.... The characteristic details are always found on the head. The mask or helmet with its symbolic decorations was made to express characteristics of the Katcinas and care was given to delineate upon this part of the doll those features, or symbolic markings, by which they were distinguished."[2] Symbols painted on the head of a doll also appear on the mask of an impersonator of the same god.[3]

The Hopi dolls are squat and stolid, with characteristic garments carved into the wood. At Zuñi the figures are more slender in proportion, have articulate arms, and are dressed in actual pieces of cloth, fur, and leather. They also wear the characteristic feathers and head ornaments. They are painted with unsized earth pigments in the colors used by the dancing gods. These dolls are made by the men during retreat and later are given to the little girls on important ceremonial days. The child is permitted to carry the doll around for a few days; then it is hung to a rafter in the house, where it serves as a model by which the children come to identify the supernatural being it represents. There is evidence of the existence of a few of these dolls along the Rio Grande also,[4] but they are kept secret, as are the masked dances in which the gods appear.

Origin of Ceremonial Costume

One may well suppose that in prehistoric days the Indian made a special garment, the duplicate of his regular dress, which he put aside with great care to be worn only on those special occasions when he worshiped his gods. To make the garment more beautiful he probably whitened the firm cloth with powdered white clay and painted it with colors which seemed to him beautiful and which, in his mind, were associated with beautiful things. When he dressed in this costume, he would perhaps ornament it with a gay feather dropped by a passing bird or a flower newly bloomed by his doorstep. Evergreen branches made fitting tribute to gods eternal, and added color and beauty to the general scheme, so he may have placed them in his belt, or made wreaths for his shoulders, or carried them as bouquets in his hands. These customs doubtless endured for centuries. Then the Spaniards came, strong, hard men who ruled and killed. They were clothed from head to foot, making their bodies safe from many hardships. Through the years which followed, the Indian men began to copy the dress of the invaders. They had not the fine fabrics of the foreigners,

Plate 30.

Aholi, the Sun Kachina, Oraibi, Hopi. Elongated mask.

but they fashioned imitative garments from the clothes which they made. However, this did not change the costume set aside for the dance worship. In this the Indian continued as before, dressing as his gods had known him whenever he had sought their aid.

Then came drought and with it a state of great distress. Food was scarce, feathers became difficult to obtain, and animals went farther afield and could not be hunted down. We may assume that laxness in worship was held to be the reason for all these calamities, and the Indian then tried very hard to costume himself exactly as had his forefathers, so that the gods would be pleased and life would again be filled with plenty. The old priests surely remembered what colors were used and where the needled spruce was to be found. These things, they must have reasoned, the gods would like to see restored. They probably tried each magical arrangement, and when one brought success that arrangement became the rule. Even today, when the prayer drama is not successful and the reviving and cooling rain does not fall, they believe it is because something is amiss in the ceremony and the Great Ones are displeased. A chant may have been omitted, the colors may have run on a mask, or a man may not have been faithful to his vow of continence during the retreat.

Fundamental Ceremonial Costume

The simplest ceremonial costumes are made up of the few garments that were worn before the white man came. An attempt to gain special favor with some god resulted in ornamentation that could be applied whenever dancing should be done for a particular result. Thus each drama calls for essential parts, distinguishing features worn or carried which differentiate one costume from another, making this one correct for the Bow Dance[5] and that for the Basket Dance.[6]

A step beyond this simple dress come those costumes which have added a fixed representative feature. The Tablita Dance, performed in many villages, makes use of a form of headdress from which it derives its name.

The tablita[*] is a flat wooden superstructure with the lower edge curved to fit across the head. It sits upright, the top cut in irregular forms, and soft feathers and the heads of beautiful wild grasses float from the points. Carried with majestic dignity, it is worn by the women dancers throughout a long, hot day of ceremony.

Among the Tewa the tablita appears in its simplest form (pl. 19). A turquoise blue plaque, painted sky-color, surmounts a head of glossy, floating hair. The top, terraced to suggest mesa and cloud, is accented by white feather puffs which represent prayers for the rain-bringing elements of nature. This touch of color enlivens the otherwise somber appearance of the women, who wear hand-woven dark dresses accented by a red belt bound around the waist. Heavy strands of turquoise and shell beads encircle the neck, and many bracelets of silver and turquoise band the arms. The bare feet scarcely leave the earth as the women move demurely, with downcast eyes, behind the men. A tight bunch of evergreen, clutched in each hand, adds the dull green of its stiff needles to this solemn scene—a scene which is nevertheless alive with color and movement, for the men (pl. 20), brilliant in their white kilts with jewellike colors, prance high, with black hair, fringe of rain sash, and pendent foxskin bounding with every step. Their hands and their bodies beneath the kilts are white. Bands of dark blue yarn are knotted at each knee, and turtle-shell rattles hang behind. White moccasins with skunk-fur heelpieces clothe the feet, and turquoise blue arm bands flaunt sprays of evergreens. The blackness of the loosened hair is accentuated by a yellow topknot of parrot feathers. Gourd rattles and sprigs of spruce are carried in the hands, moving up and down with each well-timed step.

In this dance, as observed in September, 1936, in San Ildefonso, the men and women come down the kiva steps and form casually into couples. two men followed by two women. The first figure of the dance is a forward step in a long, curved line about the plaza. In the center of the plaza

* Tablita is Spanish for "little tablet."

the chorus and the drummer stamp in time as they sing the mystic chant. On the side nearest the dancers a standard bearer takes up his position, holding a twenty-foot pole on the top of which is a banner surmounted by brilliant feathers. This he weaves slowly and continuously over the dancers.[7]

There are different tablita forms at Zuñi and Hopi, but the main costume is always the same.

A similar headdress usage is seen in connection with the Turtle Dance at San Juan,[8] where in a long file of men each wears an ornament of gourd fashioned into a blossom, with two eagle feathers, a macaw feather, and a sprig of evergreen sticking from it—the whole fastened to the top of the head in a horizontal position. There is only one exception to the usual costume: the fringe of the plaited sash, hanging down behind, takes the place of the customary pendent foxskin.

Costumes for Impersonations

So far as interesting costume is concerned, the drama impersonations loom large beside these simple prayers in conventionalized dress.

The Pueblo Indian acquires ideas from almost everything with which he comes in contact. With him the mimetic art is a natural one: he can take on a new characterization as easily as he can put on a costume.

The rigid rules governing the significant use of certain garments and decorations have been mentioned before. Likewise, each impersonation has its own delineation and a prescribed pattern of action. When a serious variation occurs, a new person results. This correlation of costume and character is of some importance. There are so few actual garments that the arrangement of them is limited, yet the many hundreds of impersonations require careful delineation to distinguish one from another. The difference may be only the color of a mask or the shape of a feather ornament, each combined with significant ornamentation.

The earliest and most universal form of impersonation was effected

by the use of cured animal heads and skins. "Impersonation of supernaturals is a religious technique world-wide in distribution. The two most common methods of impersonation are by animal heads and pelts, and by masks, but impersonation by means of body paint, elaborate costume and headdress, or the wearing of sacred symbols is by no means uncommon. In the pueblos, where all magic power is imputed to impersonation, all techniques are employed."[9]

Animal impersonations probably preceded all other impersonations. Animals were believed to be man's brothers, who by their existence made it possible for man to live. Animal headdresses and costumes were used as magic and decoy. By impersonating the animal he wished to kill, a hunter could come very close to a herd without being observed. By performing a dance before the hunt, the Hunt group believed that they could please the spirits of the animals, which would then permit their earthly bodies to be killed.

Many legends surrounding the animals form the background for these dramas. The dramas differ from one village to the next in conception of costume and in number and variety of characters. In the Buffalo Dance of San Juan there appear two Buffalo men and one Maiden,[10] whereas the San Ildefonso version requires two Buffalo men and two Maidens. Parsons says that on one occasion at Taos one hundred and forty Buffalo appeared with but two Deer characters.[11] Elk and Goat dances are also remarked, and some elaborate dramas include a large number of different beasts.

Buffalo Dance, San Ildefonso.

—The Animal Dances are usually given in winter. That is the time of year for hunting because cultivated food is scarce and the animals are then forced down from their mountain homes. At San Ildefonso I saw a Buffalo Dance performed, contrary to custom, in August, 1936. The dancers, two men and two women, came from the round, outside kiva of the Turquoise people,[12] appearing through

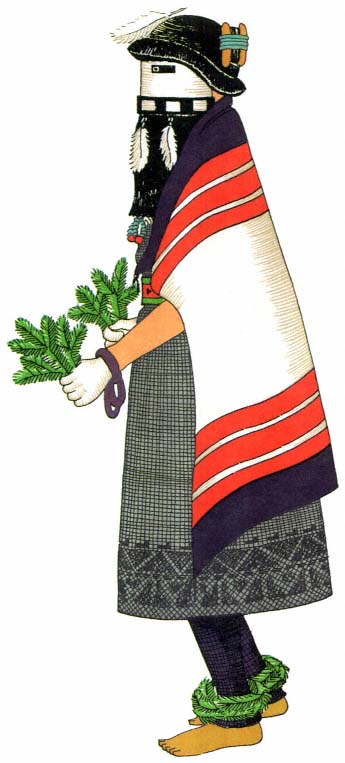

Plate 31.

Natacka Mother, Hopi. Female deity impersonation.

the hatchway about mid-morning. The bodies (pl. 21) of the men were painted a dark earth brown with white crosses on each side of the chest and abdomen and on each arm. They wore soft, cream-colored deerskin kilts, with a writhing black serpent painted through the center, and a border of blue and yellow the bottom of which was edged with metal tinklers, small cones of tin which hung from deerskin thongs and knocked together with every rhythmic movement of the dancers, making a pleasing, silvery sound. A red woven belt held the kilt in place, and a string of bells around the waist added a deeper, more musical tone, punctuating the less melodic vibrations of rattles and drums. Below the knee the legs were encircled by bands of brown buffalo hair which sustained, in front, a floating eagle feather. White moccasins with buffalo-hair heelpieces encased the feet. Arm bands were of buffalo hair. Several strands of white shell beads were worn around the wrists, and many necklaces of turquoise and white shell were around the neck. Just under the chin was a large abalone shell. A gourd rattle with a fringe of bright orange-dyed goat's hair was carried in the right hand, and evergreen and a bow and arrow with four eagle feathers swinging from the string appeared in the other. A large piece of the heavy neck fur of the buffalo over the head and shoulders made a shaggy frame for the little that could be seen of the face. The horns on each side had eagle's down fluttering from their tips. On the back of the buffalo headdress, moving gracefully up and down, was an ornament composed of a fan of eagle wing and macaw tail feathers with the quill ends covered with orange-dyed goat's hair and a large bunch of green and yellow parrot feathers. A small downy white feather was tied directly on top.

The Buffalo Maidens (pl. 22), impersonating the mothers of the game animals, appeared in dresses made from large, hand-woven, white cotton blankets embroidered at top and bottom. Over this, like a short tunic, was a man's embroidered white dance kilt. Both dress and tunic were fastened on the right shoulder. The panel of stylized cloud, rain, and

earth symbols made a line of decoration from shoulder to waist. The great wrapped moccasins of soft white deerskin gave a modest air to the costume, and the heelpieces of black and white skunk fur rounded it off. White shell beads were wound around the wrists, and strings of turquoise and white shells hung in heavy festoons on the breast. A necklace of turquoise with an entire abalone shell encircled the base of the neck. Arm bands of brilliant orange-dyed goat's hair made blobs of color midway in the figure. The black hair hung loose in a solid gleaming mass, while in direct contrast a downy white eagle feather floated from the top. At the back an ornament rose from the neckline majestically above the head. It was composed of a great bunch of green and red parrot feathers, edged in orange-dyed goat skin, supporting three macaw tail feathers—scarlet shafts of color. In each hand formal bouquets were carried. These were composed of shining eagle and parrot feathers surrounded by the dull green of spruce needles and edged with creamy white olive shells[13] which added beauty and supplied a clicking accompaniment to the rhythmic accent of the rattles.

Each dancer was in character from the moment he appeared above the rim of the kiva. With lowered eyes, the men danced with a heavy, steady, downward beat. They were young men, their bodies full of vigorous strength. Their movements, however, were not excessive, but poised and controlled in easy, graceful posture. The maidens were young and handsome. Their clear brown skins were ruddy with health and this contrasted strongly with the positive whiteness of their garments and the jet blackness of their hair. They danced demurely with downcast eyes. Their steps echoed rather than followed those of the men. Never by glance or movement did they betray a consciousness of the spectators, who might crowd in closely. Between the dance patterns the performers were in constant movement, their tinklers rattling and their bodies intent on the regular motion of a stately trot. Their leader, a priest in the somber pueblo dress of the conquistadors, was almost concealed by his great blanket. He car-

ried a feather insigne and sprinkled meal for the dancers' 'road'. The chorus was made up of a knot of men, grouped on one side, who danced gently to the rhythm of their own chants. In their midst a large drum was beaten with hypnotic cadence.

The Buffalo Dance, Tesuque.

—In the Tesuque Buffalo Dance a group of men and women, numbering eighteen couples in all, perform an entire routine as a frame for three dancers and their leaders. These line dancers — if one may call them so for convenience — come from one kiva and perform in the dance places around the village. Returning to the plaza, they stand in two lines facing each other. Here they are joined by the five Buffalo Dancers: two men in buffalo costumes and a woman in a white embroidered mantle dress constituting the group of three, and two other men, one the father or leader and the other the hunter. This second group performs a serpentine between the two stationary lines.

Figure 25.

Headdress of the side dancers, Buffalo Dance. Six eagle feathers bound

with cornhusks and a buffalo horn are tied to a deerskin with thongs.

The costumes of the line dancers are significant in reflecting the qualities of both the Buffalo impersonations and the usual ceremonial attire, a uniform which contributes to the particular performance and yet keeps its place as a subordinate element. When I saw them, the men dancers wore rough buckskin kilts, with belts and anklets of bells, and low moccasins with skunk heelbands. A blackened horn projected from the right side of the head, while on the left was a fan of six or more eagle tail feathers. Both these decorations were attached to a beaded headband.[14] The hair was queued or short. Thin strips of pelt hung from the arm and leg bands. In the right hand was a gourd, in the left a bow and arrow. The upper

and lower parts of the face were painted black, with a broad red stripe across the bridge of the nose. In one dance line the bodies were blackened, in the other they were painted red. On the backs were splotches of white paint, and the thighs, forearms, and hands were whitened.[15]

Dance of the Game Animals, San Felipe.

—The drama of the many horned animals includes all those who, friendly to the Indian, formerly provided him with food during the long winters. The actors are clothed to impersonate the buffalo, deer, mountain sheep or elk, and antelope,[16] as these were the principal game animals of the region surrounding the ancient Pueblo lands.

The San Felipe play begins at dawn when a lovely dark-skinned maiden runs swiftly toward the mountains behind the pueblo. She is the chosen mother of the animals, and she goes to lure them into the village. She is accompanied by young men dressed as hunters, in white buckskin garments similar to those of the Plains Indians. They carry bows and arrows and sprigs of evergreen. All the young people chosen for this part of the ceremony must be fleet and sure of foot, for their purpose is to run as fast as the beasts and drive them into the village amid the great applause of the spectators.

There follows a secret rite in one of the ceremonial chambers, and the entire group emerges to continue the action of the play and to dance ill the plaza, where small evergreen trees have been set up to suggest a forest. Each group, including a scattering of hunters, interprets the movements of the beasts they are impersonating. The Buffaloes, with black bodies, deerskin kilts, and heavy, shaggy buffalo headdress, dance with the solid weight of large and lumbering animals.[17] The Buffalo Maiden dances just behind the leader, her white dress banded at the waist by a red woven belt. On her head is a tight cap covered with iridescent black feathers and topped by the two small horns of the buffalo cow. Her legs are wrapped ill high white moccasins ending in skunk-fur heelpieces. Quantities of

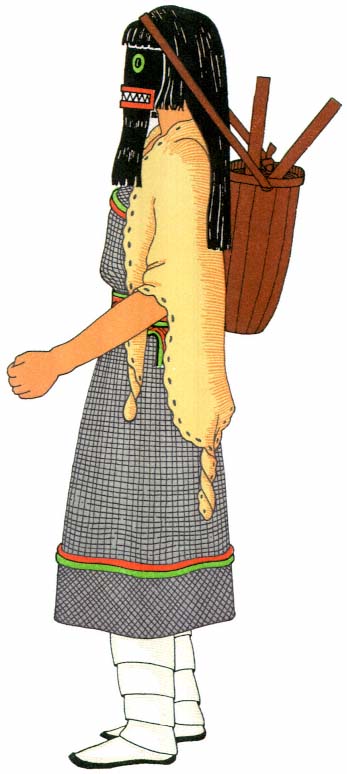

Plate 32.

Natacka Daughter, Hopi. Female deity.

turquoise and white shell beads hang around her neck. In one hand she carries a rattle wand to which are attached feathers, evergreen sprigs, and animal hoofs.

Next come the Elk, lofty and regal in their horned headdresses; and then the antlered Deer approach quickly with shy and fugitive grace. Bird down and puffs of cotton trim the prongs of horns and antlers, and from their foreheads fan-shaped visors of slender sticks rise upward and forward. A red fringe of goat's hair covers the quill ends of an eaglefeather ornament which is tied, tip downward, on the hair at the nape of the neck, and sprigs of evergreen fall over the shoulders. White shirts cover the bodies, and from waist to knee are kilts either of dark blue native stuff with a red and green strip through the middle, or of Hopiembroidered white cotton cloth. Around the waist the white plaited sashes with tasseled ends are knotted at the back to suggest the tails of the animals. White, crocheted leggings, tied at the knee with red yarns, end in low moccasins edged with black and white skunk-fur heelpieces. A light, short stick is carried, and it is decorated with a spray of evergreen which is bound to the center with cotton cord. These sticks are used to support the weight in different postures and to imitate the movement of the forefeet of the animal when running or leaping.

The Mountain Sheep appear with giant horns rising on either side of the caplike base. The Antelope wear on their bodies snug-fitting suits with the backs painted yellow and bellies white to simulate the animal's skin. On the heads are antelope horns. They frisk gaily, their feather tails bobbing up and down. The impersonators dance upright, often leaning forward to rest on the canelike props.

Interrupting the last dance, the animals break away and run for the hills. When they are 'shot down' (that is, when they are caught by townsmen or hunters) they lie inert and 'dead' while they are carried to the kiva across the hunters' backs. The successful hunter receives a spray of evergreen for his reward.

The Eagle Dance.

—In his dramatizations the Pueblo Indian represented birds as well as animals. He watched the eagle soaring overhead. This was the one bird which, with his great, strong wings, could fly out of sight in the blue upper distances. Certainly he must fly to the very sun, and surely he had direct intercourse with the Sky Powers and told the Great Father all that befell his human children! Hence, the Eagle impersonation has become very important and is often connected with medicine and curing.[18]

This dance drama expresses the supposed relationship between eagle and man and the deific powers.[*] It is performed by two young men, who, costumed to represent eagles, faithfully imitate the birds' movements.

The keynote of the eagle dress is stylized realism (pl. 23). The gleaming brown-black of the upper body is interrupted by a vest-shaped patch of bright yellow on the chest. This is outlined with eagle down. The lower arms, legs, and bare feet are as yellow as the legs and talons of an eagle, and the face is yellow with a brilliant red patch across the chin. The smart, soft, buckskin kilt, the color of cream, displays through the center an undulating snake design, and at the bottom of the kilt are strips of blue, yellow, and black, while the tinklers, made of tin and forming the fringe, click together throughout the dance. This garment is held in place by a leather belt of turquoise blue banded by a string of sharp-toned brass bells; the body beneath is painted white. Sprays of spruce stick up above the waist. A sweeping, fan-shaped tail of eagle feathers is attached at the back, and perfectly fashioned wings of long eagle feathers, bound to a strip of heavy buckskin, cover the arms and shoulders from finger tip to finger tip. The hair hangs loose, and the head is covered with white down or raw cotton, forming a deep, snug cap, to which a long, yellow beak is fastened so that it protrudes just above the wearer's nose.

It is obvious that the dancers have made a close study of the eagle's flight, so exact are they in the reproduction of the movements. They

* In the eastern pueblos it is always preceded by fasting and retreat.

create the illusion of soaring through the clouds, hovering over the fields, and perching on high aeries. Again, they strut along the ground, or fiercely swoop, or circle wildly—their bells tinkling like rain—as if disturbed by an approaching storm.

When women accompany the Eagle men in the dance, they are beautifully garbed in snowy white dresses, fringed sashes, and moccasins, accented with jet black embroidered bands, skunk fur, and gleaming hair.[19] Black and white eagle feathers are carried in each hand, and form an ornament at the back of the neck where the only relief in color harmony is the long, tapering points of yellow macaw feathers set at equal distances around a plaque and showing like a halo behind the head.

A further step in the process of impersonation is the masked being. We do not know whether this grew out of the animal and bird characterizations, but it is interesting to contrast the masked and unmasked representation of the same character in two villages so similar in material ways of life. The Rio Grande Eagle appears real and natural beside the Hopi Eagle (pl. 24), yet their origin is the same. They were nurtured on the same beliefs, and they developed with similar objectives. The Rio Grande Eagle wore a kilt of buckskin because the beautiful, soft-tanned hides from the plains were accessible to him. The Hopi Eagle, on the contrary, wore a kilt of native cotton which the Hopi cultivated and wove into cloth. The distinguishing body paint, kilt, brocaded sash, woven red belt, and pendent foxskin are the conventional items of dress for the masked supernatural, and the anklets, wound in colored yarns, are typical of Hopiland. The Hopi eagle wings are more carefully designed and have greater perfection of finish. The rough leather, where the quills of the long wing feathers are fastened, is covered with white down. On the back is a long, flat plaque or shield of buckskin edged in red horsehair, for "the eagle is the chief of birds, and so he wears the shield on his back."[20] At length there is the mask, a distorted object which does not resemble man, and which resembles a bird in nothing but the yellow hooked beak in

front. The helmet of leather, painted the sacred turquoise blue, has large projecting red tab ears and round black and white wooden eyes. The black chevron above the snout is always found on the masks of certain birds of prey.[21] Around the crown is a green yucca fillet tied in front, and from the top wave long, downy white eagle feathers and red and yellow parrot feathers. At the back, two tall black and white eagle feathers stand upright from a great pompon of small black and white feathers which is a part of the full and beautiful collar of like material.

Introduced from Hopi to Zuñi, the Eagle Dance in both villages is a prayer that the eaglets in the nests on the rocky mesa ledges may be increased in number, so that there will be a plentiful supply of fine feathers for the garments of the supernaturals in the other world.[22]

Comparison of Style

Animal impersonations show also a development from the primitive forms to the more highly symbolic and artistic ones—from the realistic to the stylized.

Taos.

—The Animal Dance as given at Taos (pl. 25) represents one of man's earliest efforts at mimetic magic. Here the impersonator of the Deer wears the head and entire skin of the carefully cured and preserved animal. "The head of the animal is over the dancer's head, the pelt hanging down his back."[23] The spectator is hardly conscious of the men's faces as they bend over two sticks which represent the animal's forelegs. A dark kilt and low moccasins complete the costume. There is little color; the sandy gray-brown hair on the back blends into the white of the bellies. Above the head rise the colorless, sharply pointed horns, and from the mouths of the animals sticks jauntily the deer's favorite food, the tender tips of the dark green spruce.[24]

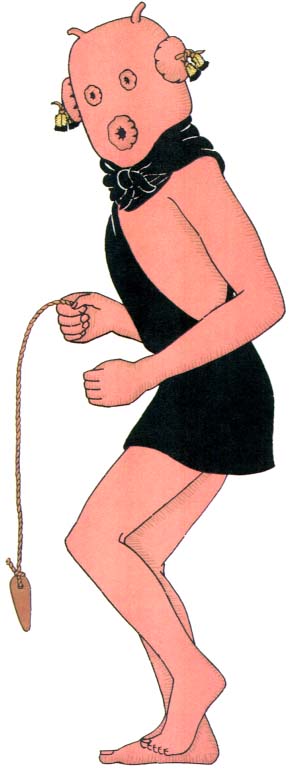

Plate 33.

Natacka Man, Hopi. This is the bogeyman of all Hopi

children. A deerskin mantle is worn over the right shoulder.

The great snout is made of gourd halves hinged together.

San Ildefonso.

—San Ildefonso (pl. 26) offers the next attempt at stylization.[25] Here the impersonator has emerged from the hide and retains only the antlers supported on a tight-fitting cap, from which hangs a sheaf of feathers. The dancers of this pueblo have also retained the ears and two canes for the front feet. An irregular visor of thin sticks has developed in front, topped by eagle's down, and sprays of evergreen hang over each shoulder. The face is painted black with an edge of white; the hands are whitened. A white shirt covers the upper body, which was probably nude until a few years ago. The kilt may be of dark blue native cloth or white Hopi cotton, and the plaited sash hangs down the back. Crocheted leggings, held in place by strands of red yarn at the knee, end in white moccasins and skunk-fur heelpieces.

San Juan.

—The Deer of San Juan (pl. 27) suggests a further step in stylization and a tendency to vary the detail. The close gray cap, tied under the chin, is dotted with eagle's down, and the antlers rise high on either side. A wide, high visor of thin yucca strips fans out around the head and destroys much of the quiet, deerlike quality. The rear of the buckskin cap tapers low over the queued knot of shiny hair and supports a wide semicircle of long eagle feathers held in place by a cornhusk ring, like a half sun-disk hanging down over the shoulder. The body is covered with a white shirt and a white kilt. The embroidered panel of the kilt is worn at the back and is somewhat concealed by the long, loose fringe of the plaited white sash knotted above it. White crocheted leggings, with bells at the knees and fringes of white cord down the front, and white moccasins with skunk-fur heelpieces complete this dress of predominant black and white. A tall staff, with three eagle feathers and an evergreen bound to the top with cotton cord, is carried in one hand, and a gourd rattle in the other. The action of the dancers is much stiffer and more conventionalized, and the animallike movements are only suggested. The dance pattern is a mere formality, and the sticks become a decoration, losing entirely their significance as the forelegs of an animal.

Hopi.

—Further degrees of stylization are seen in the Deer impersonations of Jemez,[26] Zuñi,[27] and Hopi,[28] among those masked figures which appear with all the animals in the mixed dances.[29] The simplest mask is seen at Jemez: a round green helmet of deerskin, with a flat top, from which deer horns are projected, as well as two pointed ears fashioned from leather. An evergreen collar is around the neck.[30]

At Hopi the Deer dancer (pl. 28), like the Eagle dancer, has the usual brilliant body paint, the white embroidered ceremonial kilt, white sash with brocaded ends, red woven belt, and pendent foxskin. His moccasins are of red-brown deerskin, with ankle fringes of the same material. The mask is a turquoise blue helmet with a black center and rectangular, wide, black eyes. Around the top is a low visor made from slit yucca leaves and painted yellow and red. A long, flat, black snout projects in front. On each side are squash-blossom ornaments, made of yarn wound over little sticks and forming wide, flat cones. At the back, standing upright from a bunch of owl's feathers, are two tall eagle feathers. They represent a prayer for rain. The only elements remotely related to the deer are the two horns fastened to the top of the mask. Everything else has been exaggerated or bears relationship only to the stipulated pattern of ceremonial dress. This, although aesthetically satisfactory, destroys all illusion of realism. The Indian desired this of his masked figures; since they are supernatural, they should not appear like human beings.

In many villages the characters of the ceremonial dramas surrounding these gods are often similar. However, each pueblo prescribes its own rules for costume and action, so that they do not appear alike even when borrowed. The masked figure symbolizes, to the Indian, a kind and gentle people who are fond of singing and dancing and whose greatest concern is the welfare of the human race. That is why there is no feeling of terror for them; the kachinas inspire only respect and honor.

Plate 34.

Tümas, the Mother of the Floggers, Hopi.

The mask is trimmed with crow's wings.

The number of masked impersonators is almost unlimited. New characters are added from year to year and ancient ones are often revived. Many characters are presented by groups to whom they were eventually handed down by clans now extinct.[31] This assured to the favored pueblo, throughout many generations, the benefits of the power and goodness attributed to the kachinas thus bequeathed. Whenever the costume and distinctive traits of a character become defined, that character is handed down, together with whatever ritual and legend surround him. The knowledge of this mass of ritual and legend in all its complexity gave preëminence to the office of priest, for only through him could the information be perpetuated. There are both individual and group characterizations. The individual is the only one of his kind and he has a special part to play; the group consists of a large number, all alike and appearing together in dance and song. The size of the groups depends upon the number of men who are able to participate and who desire to do so.

A description of certain important and typical ceremonies may make clear the action as well as the appearance of some of the supernatural characters. They are representative of kachina types and illustrate the various methods by which characterization is obtained.

Ceremonial Powamu, Hopi

Among the Hopi the calendric cycle of ceremonies includes a series of extended festivals, each made up of kiva rites, prayers, and dances. The festivals differ upon the three mesas; certain interpretations of costume and ritual appear to have occurred independently in each village.

Throughout a period of sixteen to twenty days of the second moon after the winter solstice, Powamu, the bean-planting ceremony, celebrates the return of the kachinas, who have been away from Hopiland since July. This festival also involves the exorcism of evil spirits from youth and man, and is appropriately placed in our month of February[32] to denote the purification and renovation of the earth for future planting.[33]

The Powamu ceremony is one of the most important and interesting festivals held on the Hopi mesa, and because it is the occasion of the advent of the supernaturals, many masked figures 'visit' the pueblo. Ordinarily, the commencement of a ceremony is proclaimed from the housetops, but for Powamu a messenger is sent from kiva to kiva to announce quietly and formally that the festival is soon to begin—a procedure required by a convention that no kachina names are spoken in public.[34] During the next few days, prayer sticks are made for placing at various shrines, and the painting and renovation of masks begins. The masks are brought out of their storage jars, the old paint is scraped off, new colors are applied, designs are painted on, and the proper feather ornaments are assembled. In the evenings dance groups from the various kivas make the rounds and entertain audiences in each ceremonial chamber. Fewkes describes such a festival as follows: "On every evening from the opening to the close of the festival there were dances, unmasked and masked, in all the kivas of the East Mesa. ... The unmasked dances of the katcinas in the kivas are called by the same names as when masks are worn. Some of them are in the nature of rehearsals. When the dances take place in the public plaza, all the paraphernalia are ordinarily worn, but the dances without masks in the kiva are supposed to be equally efficacious."[35]

Early in the festival, beans and corn are planted in basins of sand in all the kivas. The seeds are then forced to germinate by frequent watering and continuous heat. The fire beneath the hatchway is kept burning day and night, and a straw mat placed over the opening retains the heat, making the room a "veritable hot house."[36]

One morning, just as the eastern sky reddens with the dawn, Ahül, the Sun Kachina (pl. 29),[37] comes up the trail, with his great circular mask radiating eagle feathers like the rays of the sun. He is accompanied by the kachina chief. In the capacity of leader of the returning kachinas, the

Plate 35.

Black Tungwüp, the Flogging Kachina, Hopi.

The kilt is made of horse hair dyed red.

former visits each kiva, bestowing prayers and blessings and presenting gifts of corn and bean sprouts to the kiva groups in retreat.

At Walpi this character wears around his waist an embroidered dance kilt painted with a turquoise blue border and held in place by a brocaded sash over which is looped a red woven belt. A pendent foxskin is behind. His feet are covered with blue and red dance moccasins, and the leggings have a row of shell tinklers down the sides. Woven red garters band the knees, and blue yarn is tied around each wrist. In one hand he carries a squirrelskin bag of meal, a bundle of bean and corn sprouts, a chief's insigne, and a small slat of wood dentate at each end. In the other hand is a tall staff, the top decorated with eagle feathers and horsehair, while an ear of corn and a crook are attached midway. His discoidal face mask has a buckskin head covering at the back and a foxskin collar. The disk is divided horizontally in half. In the lower part, which is painted black, there is a protruding beak, above which is painted a black triangle. The upper half is divided vertically by a black line; the left side is yellow, the right side green. Both areas are covered with small black crosses. Around the upper side is a periphery of long eagle feathers and red horsehair, held in place by a braid of cornhusk.[38]

The corresponding character at Oraibi (pl. 30) is called the Aholi, and is thus described by H. P. Voth: "The Aholi paints his body as follows: Both upper arms, the sternum, abdomen, back and legs down to the knees, bright red. The left shoulder and breast, right arm and lower part of the right leg, and a narrow band or ring above the right knee and a similar band below the left knee, yellow. The right shoulder and breast, lower arm, lower part of left leg and a band above the left and one below the right knee, blue.... The Aholi is dressed in the regular katcina kilt and sash, a woman's sash [red woven belt] and moccasins. Over the shoulders he wears an old [antique] blanket made of native cotton cloth on which are drawn designs of clouds and other unidentified objects. In the center is a large drawing of the mythical being that has been observed on dif-

ferent ceremonial objects. The head is human, the body that of a large bird.[39] ... In the right hand the Aholi holds a stick, to the upper end of which six makwanpis[*] are attached.... The mask of the Aholi is also rather plain. It is made of yucca leaves and covered with native cotton cloth. To the lower edge is tied a foxskin, while to the apex are fastened a number of feathers of various kinds and to the sides a blossom symbol."[40]

An occasion of the ceremony most dreaded, especially by the young, is the advent of the monsters, the Natackas. These are horrible creatures who threaten and frighten those who have misbehaved at any time during the year. They are the bogeymen of all little Hopi children. They make two visits, the first early in Powamu, when they come to demand food which will be collected on their second visit, which is on the last day. The night before each visit, they are announced by a loud dialogue in which they demand to see the children. The kiva chief replies that they must wait because everyone is at home asleep. The following day they parade through the streets, threatening the villagers, and frightening the children and accusing them of their misdeeds. The food, or spoils, is gathered up by one or two Hehea (pl. 4) who accompany the Natackas.

The Natacka Mother (pl. 31), impersonated by a man, wears a woman's dark dress. A white brocaded sash is wrapped twice around the body so that the many-hued ends meet and fall at angles down the front, making a brilliant herringbone of color. The sash is held in place by a red woven belt. A maiden's blanket, woven of native white cotton with red and blue borders, is thrown about the shoulders. The feet and legs are covered with soft white wrapped leggings, and the hands are whitened. A supple foxskin collar hides the lower edge of a helmet mask which has on its face an inane expression; the character is supposedly stupid. Black human hair, twisted into rolls, hangs down on each side like the Hopi matron's coiffure. A thin red horsehair fringe veils the face, and a topknot of squaretipped turkey feathers flutters from the apex.[41]

* An aspergillum used in connection with the Medicine Bowl.

The Natacka Daughter (pl. 32), smaller and more active, also appears in a dark dress, a red belt, and white wrapped moccasins. Over her shoulders like a cape she wears a streaked buckskin mantle. Her unpleasant face mask has round green eyes and a straight mouth edged in red, with jagged teeth. A black horsehair beard hangs beneath. The real hair of the boy who is impersonating the character hangs loose, and at the front is smeared with white clay. The Natacka Daughter is supposed to be disreputable and slovenly. On her back she carries a basket by means of a cord passed over her head. This is to contain the food as it is gathered by the Heheas.

The male Natackas (pl. 33) wear light shirts, dark trousers, and redbrown buckskin leggings held up by red woven garters. Their feet are covered by ordinary moccasins. Soft buckskin mantles pass under the left arm and are fastened on the right shoulder, and the hands are whitened except where the paint is removed by drawing the fingers across their backs, leaving a definite design. The awe-inspiring helmet masks have large open snouts with pointed teeth. The bulging black and white eyes appear to spring away from their dark background, and the sharp feathertipped horns add to the frightening effect. A fan-shaped crest of eagle feathers, bristling with animosity, stands upright at the back, and a trifid design painted[42] on the forehead suggests deep and scowling ill-humor.

During the several days of retreat the men make kachina dolls for the girls and miniature bows and arrows for the boys. These are given to the children at the last performance. The masks used in the night dances are always redecorated by day. On the day set aside for this purpose the women renovate the kiva by replastering the walls with a thin wash of adobe mud, thus keeping it fresh and clean.

Every four years, children between the ages of six and ten years are initiated into the kachina group[43] at a rite which occurs during Powamu. This rite is observed in one of the kivas. Tümas, a kachina woman, and her two sons, the Black Tungwüp and the Blue Tungwüp, participate.

The masked figure of Tümas (pl. 34), impersonated by a man, wears a woman's dark dress, and a white plaited sash with a long fringe is knotted on the right side. A hand-woven white cotton mantle, embroidered with brilliantly colored borders, is thrown over the shoulders. Tümas carries a sheaf of long, dull green, yucca leaves. Her turquoise blue helmet mask has a double triangular face design in black, edged with white—an effective balance of dark, middle, and light values. On either side of this mask, tied in a vertical position, is an appendage of crisp black feathers—the entire wing of the impertinent crow. A topknot of gayly colored parrot feathers forms the apex of the mask.[44]

The Tungwüp (pl. 35), her two sons, act as floggers. They are often dressed in costumes exactly alike. Their bodies are covered with dull black paint, upon which appear occasional small circles of white kaolin, emphasized by fluffs of eagle down stuck to the centers. The forearms, chests, and lower legs are painted yellow, and white is applied to the hands and the bodies beneath the lower garments. An unusual form of kilt, consisting of a deep fringe of horsehair stained red, is worn around the waist and held in place by a leather belt of turquoise blue. This color combination is striking and effective, and the long strands of wiry horsehair fall in graceful shapes around the bare, painted legs of the dancer, who is in constant rhythmic agitation. The ends of the everpresent breechclout form a decorative part of this body covering. These are drawn out over the top of the kilt and belt, and hang in front and back like small, dark blue aprons, with cords of green and red yarn tracing a square in the lower section. Arm bands of turquoise blue leather, worn above the elbow, have tassels of green yarn and floating eagle feathers hanging from their outer sides. Strands of dark blue wool are tied below the knees, the loops swinging in front. Tortoise-shell rattles, hanging over the calf of each leg, emphasize every movement with sound. Red-brown moccasins are worn, with anklets of fringed red-brown deerskin, adding

Plate 36.

Blue Tungwüp, the Alternate Flogger, Hopi.

a rich accent at the feet. In both hands are carried whips of lithe, tapering yucca leaves which are used in the initiation ceremonies.

The mask which accompanies this costume is a leather helmet painted shiny black. A long, black, curved horn of gourd, with traceries of turquoise blue, sticks out from either side. Eagle feathers, tied with the soft twist of native cotton cord, trail from the center of each horn. The eyes, which are bulging black and white wooden spheres, stare out of the flat brilliance of the surface. Across the lower edge of the masks is a leather strip forming a wide, many-toothed mouth with a border of red, from the bottom of which hangs a black horsehair beard striped with three horizontal bars of white paint. At the apex of the mask, extending backward, is a fan-shaped ornament of eagle feathers, the quill ends hidden by a brilliant topknot of parrot feathers. A glossy gray foxskin collar covers the neck space between mask and body.

When the characters of the two floggers differ, the second is represented by the Blue Tungwüp (pl. 36). His body, like that of the Oraibi Aholi, is painted in three colors: yellow on the left shoulder, the right forearm, and the left lower leg; blue on the right shoulder, the left forearm, and the right lower leg; and red on the torso, the upper arms, and the upper legs. The hands are white. Around the waist is the usual embroidered white kilt, many-colored brocaded sash, and red woven belt with a pendent foxskin. Red-brown moccasins with fringed anklets are on the feet, and strands of blue yarn are around the legs. Above the elbow are turquoise blue arm bands, and the costume is completed with a wristlet of yarn and a bow guard. He carries smooth, slender yucca leaves. The mask, similar to that of the Black Tungwüp, is painted turquoise blue with the same designs traced along the black horns, and the same eagle feathers and brilliant topknot.

Mr. Voth's description of the rites[45] enables us to follow the ceremonial procedure on this day when the small neophytes are initiated into the secret cult of the Kachinas.

In the morning, colored sands are procured from the dry jars in the inner rooms of the chief's house, where treasures are carefully stored. A space about four feet square is cleared on the floor, and selected men, who know the ritual, begin the arduous process of creating a sand painting which is used only on this particular day and is destroyed before the sun dips below the blue outline of the San Francisco Peaks to the west. "They first sift a layer of common yellow sand on the floor, three-quarters to one inch thick. This is thinly covered with a layer of light brown ochre [and] on this field are then produced three figures," the flogging kachinas and their mother.[46] On each side appear the Tungwüp, black figures with white arms and legs, red fringe kilts, and black heads with horns and feathers. In each hand are long yucca leaves. The central figure represents Tümas, and she is dressed in a black dress, white sash and mantle, and a blue head with side appendages and a white topknot. Over the field are spots of different colors which represent herbs and blossoms.[47]

A second and smaller sand painting is made by the Powamu priest in the afternoon. It represents Shipapu, the place from which the human family is believed to have emerged. On an ocher background is described a square of different colors representing the four different quarters: yellow, north; blue-green, west; red, south; and white, east. Each side has, in directional color, a terraced figure which is said to "represent the blossoms of Shipapu." Lying on each side is an ear of corn and a celt or stone implement, both of which are colored to correspond to the direction, like the figures.

After the preparations have been made, a short kiva ritual is performed. The three impersonators then go to another room to put on their costumes. "By this time the children who are to be initiated begin to arrive. Each has a white corn ear and is accompanied by two persons, one male and one female, who may be either married or single. They are said to 'put in', i.e. to introduce or initiate the young into the katcina order.... When they arrive with their candidate they all sprinkle a pinch of corn

meal on the natsi[*] and, having descended the ladder, sprinkle meal also on the small sand mosaic; whereupon the candidate is requested to step into ... a yucca-leaf ring or wheel.[**] ... Two men, squatting on opposite sides, hold this ring and, when the candidate is standing in it, raise and lower it four times, expressing at the same time the wish that the [child] may grow up and live to an old age and always be happy. [The] candidate is then taken by his sponsor ... into the north part of the kiva; another one follows and so on until all have gone through the same performance."[48] This is followed by the entrance of the Powamu priest, who comes down the ladder and takes his place on one side. As the God of Germination and Growth, he tells of his mythical wanderings and his final safe arrival in the pueblo. This long, rhythmic chant is full of the beauty and imagery of the Indian legends, colored by their aesthetic appreciation of nature. At its close he goes among the people, sprinkling the heads of the young candidates with 'medicine'. As he climbs the ladder to depart, four Mudheads appear and conduct a short ceremony at the small sand painting, using the objects which lie on each side in a ritualistic manner.

A sudden noise is heard above the hatchway. The great moment has arrived! Accompanied by loud hooting and the clatter of rattles, the two floggers and their mother descend the ladder. With Tümas near them, the Tungwüps take their positions on either side of the large sand painting. Throughout their part in the ceremony they keep up a continuous howling, grunting, rattling, and brandishing of yucca leaves. The candidate is placed on the sand painting and, if a boy, divested of his clothes; only the shawls of the little girls are removed. The candidate is then given four or five lashes by one of the Tungwüps, who relieve each other at the task of flogging, often exchanging their cudgels for new ones from the supply horne by Tümas. Many of the older people present their arms and legs for the beneficial blows. The flogging is performed for the purpose of purification, but it also suggests a punishment which may be meted

* Society emblem at the hatchway.

** Four lengths of yucca leaves tied together.

out to any initiate who betrays his knowledge of the secret rites and beliefs which are soon to become so important a part of his life. Now the initiate is to learn the supernatural myths, to dance when rain is needed, and to become powerful through the knowledge of prayer and rite by which the gods of his universe are approached.

The many kachinas who return to wander about the villages and dance on the days when no specific public rituals are scheduled, are not always the same from year to year. "Of the masked personations among the Hopi, some, as Tungwüp, Ahül, and Natacka, always appear in certain great ceremonies at stated times of the year. Others are sporadic, having no direct relation to any particular ceremony, and may be represented in any of the winter or summer months. They give variety to the annual dances, but are not regarded as essential to them, and merely to afford such variety many are revived after long disuse. Each year many katcinas may be added to any ceremony from the great amount of reserve material with which the Hopis are familiar."[49] Dance societies from other pueblos send groups of their supernaturals to take part in the general celebration.[50] The Mudheads are always present; they entertain with crude and often obscene play.

Dances are performed in all the kivas on the evening preceding the last day of the ceremony. This is the occasion upon which the newly initiated children learn, for the first time, that the kachina dancers whom they have been taught to regard as supernatural beings are only mortal Hopis. They sit with their mothers in the raised part of the kivas and watch the Powamu Kachinas dance. These kachinas wear no masks, a rare occurrence for a formal dance night and one due, no doubt, to the presence of the children. All the deities, both male and female, are impersonated by men. The bodies of the male dancers are painted in the customary bright colors: yellow on the left shoulder, the right forearm, and the left

Plate 37.

Kokochi Dancer, Zuñi. One of the group of Rain

Dancers, all of whom wear the same costume.

lower leg; blue-green on the right shoulder, the left forearm, and the right lower leg; white on the hands and the body from waist to knee; and red on the remaining parts. There are the usual white embroidered kilt, brocaded sash, red woven belt, and pendent foxskin. There are leg bands of dark blue wool, and a turtle-shell rattle behind the right knee. The moccasins are blue and red with wound heelpieces. A bandoleer of red and blue wool hangs over the right shoulder, and many strings of beads are around the neck. The gourd rattle is carried in the right hand and a spruce branch in the left. The hair hangs free, topped with an ornament of three cornhusk flowers (fig. 14, p. 87), and the face is rubbed with corn meal, which is said to absorb the perspiration.

The manas, or Maidens, are actually young men, each dressed in a woman's dark dress, red woven belt, and a maiden's blanket with red and blue borders, and wearing wrapped moccasins on feet and legs. There are strings of beads around the neck, and pendants hang from the ears. The hair is done in whorls, and a cornhusk sunflower is fastened to the forelock. A sprig of spruce is carried in the left hand. The face and arms are painted white with kaolin.[51]

At sunrise, on the last day, the sprouts of bean and corn, which had been planted early in the festival and forced to germinate by heating and watering, are tied into little bundles. Two men from each kiva, impersonating different kachinas, distribute them along with the kachina dolls and tiny bows and arrows which the men have made during the days of retreat. The bean sprouts are used as one of the dishes in the feast which terminates this long period of ceremony and festival.

Ceremonial Kokochi, Zuñi

In the group dances in which the kachinas are all alike, the men are dressed with extreme care. Each part of a costume is as like that of its neighbor as human hand can make it. No corps de ballet in white tarlatan and pink slippers could be more uniform. The stiff white kilt is folded

around the body to the same point above each knee, the shining black hair hangs to the same straight line at each waist, and the tail of each swinging foxskin clears the ground by the same few inches. The Zuñi Kokochi (pl. 37), the good or beautiful kachinas, are an excellent example of this nicety of similarity.

In September, 1936, I made a casual visit to the pueblo of Zuñi. Leaving my car near the road, I slowly circled the adobe houses in the direction of the sacred dance plaza. Suddenly I heard the deep tones of a chant, vibrant and somber. Climbing to the housetop, I looked down upon the dancing gods below. Forty-five dancers, facing each other, stretched in two lines along one side and part of each end of the plaza. One row, thirtyone in number, representing the male characters, danced shoulder to shoulder with their backs to the plaza. Nearest the wall and facing them were fourteen Kachina Maidens, who turned with the male dancers.[52] The movement flowed continuously from one end of the line to the other. Around, behind, and in the center capered the ten Mudheads, watching the dancers intently so that they might give immediate assistance when hair was entangled in evergreen sprig or turtle-shell rattle slipped from its leg position and interfered with a performer's movements. A dancing god should be as unconscious of such irritating trifles as a West Point cadet on dress parade.

At the head of the lines stood the priest, without a mask, his gray hair clubbed at the neck and bound with a hairband, and a downy white eagle feather moving gently at his forelock. He wore a dark blue shirt of native weave with set-on sleeves, and a white kilt with a brocaded sash tied on the right side. On his legs were blue knitted leggings held in place by red and white garters. He carried a terraced-edged bowl from which he sprinkled meal to make a 'road', and a beautiful wand, the insigne of his society, made of many kinds of brilliant feathers fashioned together and concealing an ear of corn. This ear of corn is known as the "life token."

Plate 38.

Kachina Maiden, Zuñi. Conventional

dress of the female deities.

In the long kachina line there were twenty-nine Kokochi, their bodies painted with pink clay from the Sacred Lake. Each one wore the conventional white embroidered kilt. The white plaited sash, the symbol of rain, was knotted on the right side and the long cord fringe moved restlessly with the dance. A red woven belt was looped over the sash. Pendent foxskins were fastened to the belts in the back, their tails clearing the ground by a scant three inches. Sprigs of spruce were stuck in each belt and woven into bristling anklets worn just above the bare feet. Spruce was carried in the left hand of each dancer. Just below each knee, bunches of dark blue native-spun yarn were tied. At the back of the right leg, just below the bend of the knee, was fastened the turtle-shell rattle. From it hung deer hoofs which hit against the hard shell as the uneven beat was accented with the right foot. A bunch of blue yarn ornamented the right wrist, and a bow guard of leather with silver and turquoise the left. Bunches of native blue yarn and many beautiful necklaces of turquoise and white shell were worn around the necks of the dancers. The right hand carried a gourd rattle filled with pebbles, the clatter of which simulated the sound of falling rain. The half masks were blue-green with rectangular black eyes. The added strip of leather edging the bottom was painted in blocks of black and white, "symbolic of the house of clouds" where the Sky Gods live.[53] A long beard hung from the lower edge of each mask. The dancer's own hair rippled loose and free with a knot of bright yellow parrot feathers on top of the head. A white homespun cotton cord, weighted with a piece of turquoise or a silver trinket, fell down the back, and to this at regular intervals downy eagle feathers had been attached in an erect position.

With the Kokochi, and dancing in their line, were two Upoyona or Cottonheads (pl. 17); one or two of whom often dance with the Kokochi.[54] They are gentle dancers, the sons of the chief of the sacred kachina village, and they occasionally come with the Kokochi to aid them in bringing rain.[55] They were dressed exactly the same as the other dancers: body

paint, kilt, sash, belt, spruce sprigs, foxskins, and wrist guards, yarn on arms and legs, rattles. However, instead of spruce anklets they wore turquoise blue moccasins with red trim and black and white heelpieces of porcupine quill. Their helmet masks had blue faces, with domino-shaped designs around the eyeholes. There were large eartabs edged with thick fringes of hair, and the wigs were of black horsehair straight-bobbed at the lower edge of the great spruce collars. There were long, flat snouts, and topknots of downy white eagle and yellow parrot feathers, from which hung three strings of loosely twisted cotton cord laid over the black hair at the back.

The Kachina Maidens, or Kokwelashtoki (pl. 38), form the second line.[56] They wore black dresses of woven wool. White Hopi blankets with red and black borders were thrown over their shoulders. The feet were painted yellow and the hands white. The legs were covered with dark blue knitted leggings, and there were anklets of evergreens. Blue yarn was tied around the wrists, and bunches of spruce were in each hand. They also wore many necklaces. The half masks were white with rectangular black eyes, and the shiny blackness of the thick horsehair beard was broken by the soft whiteness of three long, downy, eagle feathers. The hair was parted in the middle and wound on either side over rectangular frames of wood; then it was bound with yarn. Thick black bangs of goat's wool hung completely around the head, thus concealing the edge of the mask. A single white downy eagle feather hung from the center of each forelock.[57]

The Kokochi Dance, a prayer for moisture, is performed more often than any other Zuñi ceremony. It always opens the summer series. It is especially important on the occasion of the return, every fourth year, from the Sacred Lake, where certain of the impersonators go to acquire clay and tortoises. The live tortoise is afterward carried in the dance. Later it is killed, and the shells are cleaned and made into dance rattles which

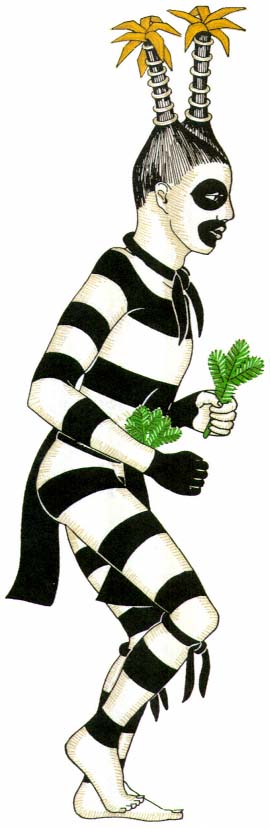

Plate 39.

"Chiffoneti" clown, striped from neck to ankle.

are worn by all masked dancers. These masked beings, "the prototype of the katcina,"[58] are particularly identified with the Lost Children. The legend says that in the course of wanderings subsequent to the mythical emergence of the Zuñi from the four worlds below, they crossed a stream. The children, carried upon the backs of their mothers, fell into the water and were immediately turned into snakes, turtles, lizards, and frogs.[59] Swimming into the Sacred Lake, they became kachinas, and they have lived there ever since. The manner of the Kokochi is always gentle and mild, and they always bring happiness to the people. Their prayers and dances call down the rains and thus keep the world green and beautiful. They come at any time in winter or summer and are impersonated by dancers from each of the kivas in turn. In winter, when the Kachina Maidens come to dance, they bring, hidden under their blankets, the corn for the people to plant in the spring. It is deposited on the altar of each kiva they visit, and the priest distributes it at the end of the dance ceremonial.

The Kokochi is one of the dances which "require the presence of a couple, male and female, at the head of the line, who go through certain peculiar motions and have certain esoteric prayers. Only three men know these prayers, and they must be invited to perform for all kivas."[60] The two lines form in the ceremonial chambers and march in order to the dance plaza. They are led by a priest who, scattering corn meal before them, "makes this their road."

These same masked dances are said to be found in other pueblos,[61] but nowhere is there such precision of step and unanimity of costume as in this oft-repeated Rain Dance of Zuñi.

Clowns

In its ceremonial organization every pueblo has at least traces of two esoteric orders of Clowns, the most potent of priest groups, who appear with the Kachinas and at the Rain Dances.[62] As "Delight Makers" they contribute the comedy interludes to the solemn religious dramas, and

they also perform theatrical entertainments of a secular nature. These secret orders differ in name, membership, and duties in the various pueblos.

"Chiffoneti."

—One order, the "Chiffoneti" (pl. 39), is called the Black Eyes at Taos and Isleta, Kossa among the Tewa, Koshare by the Keres, Tabösh at Jemez, Newekwe at Zuñi, and Paiakyamu at Hopi. The members of the different groups of this order impersonate, without the use of a mask, a certain kind of supernatural. For the concealment of their identities they depend entirely upon the painting of their bodies and faces and the arrangement of their hair and headdresses. These extraordinary beings are striped from head to foot in horizontal black and white earth colors. Their faces are white with circles of black around their mouths and eyes.[*] They wear breechclouts with the ends hanging to midthigh.[63] These are held in place by a narrow belt around the middle. The hair is parted in the center and bound in two bunches which stand upright on each side of the head and are trimmed with bristling rosettes of cornhusks.[64] Among the Tewa, this cornhusk is called "mist."[65] Short hair necessitates a two-pointed cap in imitation of the horned hairdress. This cap is striped in black and white, carrying out the general decorative scheme. Sometimes strips of black cloth are tied around the neck and knees. Branches of evergreen are worn in the belt, or in a bandoleer over the right shoulder,[66] or carried in the hands.[67]

The comic action of these entertainers is impromptu, and it occurs between the appearances of the main drama dance. For subject matter they make use of incidents in village gossip, or they mimic spectators in the crowd. Erna Fergusson, speaking of the Koshare at a Santo Domingo Tablita Dance, says that "a fat one, one day, caught sight of a plumpish matron watching the dance. She was trim and erect, and with a dignity that would have abashed any white clown. But not the Indian. Approaching her, in her full sight and knowledge, he minced, swinging his ample

* In one group, at Jemez, yellow and white body stripes are used (Parsons, 1925b , p. 91). The Newekwe at Zuñi are not all striped; some are merely "ash-colored," but their hair is done in the same manner (Stevenson, 1904, p. 436).

hips, extending a condescending hand, caricatured her so exactly, but with such complete good humor, that the dowager herself laughed and made friends."[68]

Again, these black and white clowns may entertain a crowd by dramatizing an incident. At Taos, on St. Geronimo's Day, a greased pole is set up in the middle of the plaza. From the top a sheep and various other spoils are hung, a reward for the one who successfully climbs that high. On a particular occasion, "one of the Delight Makers walked up under the pole on which the sheep was hanging and made sheep tracks with his fingers in the dust. ... Another strolled by and, discovering sheep tracks, began trailing the animals eagerly, looking everywhere until, glancing up, the dangling sheep caught his eye. Then with tiny bows and arrows the actors began shooting at the sheep with great glee and horseplay. Afterwards they went through the performance of climbing the pole. When the first man slipped down they put earth on the shaft, and when he climbed part way the others dropped on all fours, acting the part of furious bulls ... to discourage the climber's descent."[69]

When the influence of the Church made itself felt among the Rio Grande villages, many Catholic ceremonies[70] were burlesqued. This would indicate that in prehistoric times the 'play' was also about local matters, such as a caricature of some secret ritual which had been performed previously in the kiva.[71]

Mudheads.

—Of the many groups comprising the second order of clown priests, the Mudheads (pl. 40) are the most active. Known locally at Zuñi as Koyemshi, and among the Hopi as Tachuki, they entertain between the dances with comic and often obscene interludes, or play their favorite games of beanbag, tag, and leapfrog, to the great interest and amusement of the spectators on the housetops. Representing childish, immature characters[72] in both action and appearance, they wear knobbed, soft masks of cotton cloth colored with pink clay from the Sacred Lake. The knobs, in various distorted shapes, are filled with raw cotton, seeds,[73] and earth

from the footprints made by the inhabitants in the streets around the pueblo. By using this earth, the Mudheads are supposed to acquire a magical power over the people and can demand from them respect and reverence.[74] Sometimes feathers flutter from the knobs. The lower border of the mask is finished with a strip of black homespun tied at the throat. Concealed under this is a small bag of seeds from the native crops: squash, corn, and gourd. The body is painted all over with the sacred pink clay, and the only garment is a short kilt of black native cloth. The leader often wears a scant tunic caught over the right shoulder, and he is distinguished by this. At Zuñi this group always comes in a full company of ten representing brothers of one family,[75] but each member of the group has a different personality which is discernible in the expression on his welted face and by the antics he performs.

These Mudheads play an important part, as illustrated by Mr. Fewkes,[76] in a "theatrical performance" enacted at Hopi. In March the drama of the Plumed Serpent is performed by various groups not ceremonially related. On one of the evenings a series of several acts of the drama makes the rounds of the various kivas, at which the members of each clan are assembled. The principal theme of this drama centers about the mythical Great Serpents, symbolizing wind and flood, who come from the sky or from holes in the earth. The Serpents destroy the corn and other provender of the human race. The Spirits of the Ancients, the Mudheads, with superhuman powers which cause the corn to grow, struggle with these monsters in an attempt to overcome their destructive forces.

When these scenes are performed at the kivas, the audience sits at the raised end. In the middle of the room two men tend the fire which is the only source of light. Upon hearing the first group of actors at the hatchway above, these fire tenders rise and hold their blankets about the fire in order to darken the room. Behind this 'curtain' the scene is set. Some

Plate 40.

Mudheads, clowns best known at Zuñi and Hopi. Grotesque

and potent rain priests with bag mask and bull-roarer.

of the backgrounds are large screens of thick cotton cloth painted with symbolic designs of rainbows, clouds, and lightning. There is a row of circular holes covered by disks of deerskin with borders of plaited cornhusks. Through these holes, Serpent effigies, made of cloth with gourd heads,[77] are thrust to squirm and wriggle. The Serpents eventually sweep over a miniature cornfield and knock down the green sprouts set in clay balls in front of the screen. In one of the scenes the Serpents struggle with the ugly masked spirits who attempt to thwart their movements. In another scene two large jars are used, the effigies emerging from the tops as if from the earth.

These Serpent acts are interspersed with dances by masked figures and with interludes which deal with the Corn Maidens and the grinding of the corn into meal. The latter scene is sometimes enacted by marionettes, set in wooden frames and manipulated, as were the Serpents, by men concealed behind the screen.

The main purpose of this series of scenes is to instruct and entertain. Based upon legendary events, a combination of history and myth, they originated from ceremonial procedure, but they employ few of the sacred objects generally found in Hopi rites. Mr. Fewkes believes that these facts justify the application to them of the title, "theatrical exhibitions."

This mythical Serpent phase is found in other pueblos,[78] but at no other village has the ceremonial procedure given way to so secular a performance.

The scope of theatrical entertainment among the Pueblo Indians includes all these phases which appear between the simple, physical prayer, danced to climax a period of ritual and worship, and the pseudoreligious drama which has character impersonations and paraphernalia of ceremonial origin, but which disregards the demands of a patterned form.

As a phase of theatrical practice, the native Pueblo drama had its origin in the worship of supernatural powers and its development in the coercing of those powers and the instruction of its followers through story,

impersonation, and action. It had approached the sphere of religious drama. Its death knell was sounded when an invading culture corrupted its beliefs and perverted its believers. Today the surviving practices indicate little of what might have been the full flowering of its maturity.