Modernity and Ascription

Hans Haferkamp

1. Patterns of Development in Modernity

Reflection on the character of modern society suggests that there are two starting points that are not especially viable. The first is Weber's description of Occidental rationalism (Weber 1920); the second is Parson's "relatively optimistic" description of modern society ([1971] 1972, 179) in which he forecast that this society would flourish for another century or two. The modern societies of Northwest Europe, the United States, Canada, and Japan are not characterized by maturing processes alone; they also give evidence of counterdevelopments (foreseen by Marx) and developmental excesses that cloud the picture of continuing upward progress.

These observations are not new. Antinomies and instances of hypertrophy have always occupied a central place among sociology's major topics. Yet insistence on the particular structural features of "advanced industrial societies"—features that include the upward march of capitalism, democracy, the market economy, and prosperity—tends to live on (see Zapf 1983, 294). One example of this tendency is Dieter Senghaas (1982), who does not discuss the autumn of modernity or the beginnings of postmodernity; rather his analysis is characteristic of the optimism of the European grande bourgeoisie around the turn of the century, the United States since midcentury, and contemporary Japan.

Why has this affirmative view of modern social change persisted? As modern theory has moved away from philosophy and become more empirical in character, theorists tend to stick to positive "givens," concluding that a comparison of data from past and present indicates continuing progress. This type of analysis underscores the optimistic diagnosis. But this approach is in one sense odd because a comparison of past and

present should also reveal instances of hypertrophy and counterdevelopments worthy of note. In fact, establishing the counterdevelopments and developmental excesses has been left to social scientists with a philosophical bent (from Marx and Engels [1848] 1964), to novelists like Baudelaire (1925), and, occasionally, to sociologists like Weber, who sang the praises of rational capitalism but also saw counterdevelopments. Today some theorists, specifically representatives of the Frankfurt school and social thinkers like Arnold Gehlen, see decline and fall everywhere and emphasize the decay of civilization in modern societies. Yet these negative characterizations also have a way of losing any sense of proportion.

Bendix (1971) has brought out the problems of Western European rationalism from a realistic stance. He identifies the loss of the feeling of Western superiority, which had lasted for decades. He also notes that "the harnessing of nuclear power marks the beginning of a scientific and technical development calling into question the 350-year-old equation of knowledge with progress for the first time in the consciousness of many people" (179, 13). Following Bendix's approach, we find development, excess development, and counterdevelopment unfolding as follows:

1. The development of various resources used to secure survival and a better life has a counterdevelopmental side that is especially evident in the widespread environmental damage that accompanies it. In addition, counterdevelopments are making themselves felt with the underutilization of potential resources (for example, the labor of youths, women, older people, and foreigners). One of the questions that arises in connection with the deployment of resources is the pattern of social distribution of resources and rewards. The evidence in modern societies indicates that these resources and rewards then to be evening out. For example, educational resources are being concentrated to a greater extent in the lower social strata.

2. All modern societies show a rising level of production measured in terms of goods and services. At the same time, however, counterdevelopments are evident. The continuing application of technology gives rise to new hazards to health and new forms of oppression. These kinds of developments have raised questions about the meaning and purpose of societal development.

3. Modern societies also show growth in power and authority relationships. Both increasing numbers of decision makers and increased political participation are evident (Baudelaire 1925). The involvement of the lower and middle strata in Western European societies ranges from strong interest in politics and high polling rates in

elections to civil protest. These kinds of movements often result in the abandonment of government proposals, and there has been a kind of diffusion of power in the realm of decisions about the deployment of atomic energy and destructive weapons.

4. Remuneration has increased, as suggested by the terms "superabundance" and "the affluent society." Rewards are distributed so as to provide a high level of welfare for almost all actors, and there are minimum standards of economic provision for all phases of the life cycle. Although welfare measures also tend to distribute wealth downward, there remains a residual of poverty in all modern societies (Lockwood 1985).

5. Knowledge of one's own society has been enhanced, often at the expense of traditional religious interpretations. However, it is often impossible to apply this knowledge to the planning process because national planning efforts are subverted by international developments over which planners have little or no control.

6. A further hallmark of modern societies is the high degree of individualism and the desire for self-realization on the part of their citizens. The citizens resent control from above or from any other part of the political spectrum. Increased individualism may, however, spill over into the legitimization of deviance and crime, result in an increasing suicide rate, and give rise to anxieties about future prospects for life. Individualism is accompanied by a loss of community commitment and a loneliness on the part of the masses.

Some of the developments, developmental excesses, and counter-developments mentioned here come about very rapidly, others very slowly. Modernity is synonymous with the continual entry, at different rates, of new elements that are in conflict with established arrangements.

Significant distinctions can be drawn between modern and other societies on the basis of six dimensions: (1) increasing mobilization of resources, (2) increasing levels of positive effort, (3) power relationships, (4) increasing levels of consumer welfare, (5) increasing dissemination of self-reflection, and (6) increasing levels of individualism. Also, the increasing downward distribution of each of these dimensions distinguishes modern societies from others. And of course it is also possible to see differences among modern societies with respect to these six dimensions. But let us confine our comparison to the United States and the German Federal Republic. We can make the following observations:

1. The mobilization of resources is well advanced in both societies. However, important resources lie fallow, both in the potential pool of labor and in the field of education and training. Although West Germany exhibits high levels of achievement and educational

standing, the proportion of willing actors unable to produce effort is higher than in the United States, as is evident in statistics on unemployment and rejected students. Also, lower-class social groups in West Germany are still underrepresented at universities and other institutions of higher education compared with the United States.

2. The level of positive effort is high in both societies but its downward distribution is more pronounced in West Germany—as typified by the image of the "hard-working German"—than it is the United States. A phenomenon that is particularly advanced in West Germany is that achievement problems are identified at the highest level. An increasing number of West German actors now reject the old equation, "level of achievement equals level of welfare" (see Ronge 1975; Kitschelt 1985).

3. Power is becoming increasingly diffuse in both societies. However, the downward distribution of power is more pronounced in West Germany. A higher degree of political participation has been achieved there, and changes in power have occurred whenever the workers' party has attained a mandate to govern. In the United States the existing ruling authority has more effectively defended itself against influences from below.

4. In West Germany remuneration is more evenly spread, and the distribution of goods is less skewed than in the United States.

5. The ability to indulge in self-reflection and to self-steer relationships is downwardly distributed to a more marked extent in the United States than in West Germany.

6. Likewise, individualization is stronger in the United States and the trend is accelerating. North American permissiveness is not yet evident in West Germany.

This mixed picture shows that it is impossible to identify either one of these nations as clearly the more modernized.

2. Change through Action

How can developments in modern society be explained? Why is change so rapid and intense on the one hand and so slow on the other? How can developments of different magnitudes be related to one another?

If these questions are to be answered properly, it is necessary to have some kind of conceptualization of permanent change, and not to simply attempt to explain current arrangements as an extension of past trends. Everything is in permanent flux.

The conceptualization of social change must also take into account that different structures do not simply exert influence independently of one another; they also exert influence on one another. Thus, inequality in the distribution of resources and power in the economic sphere is neutralized by political institutions, such as universal suffrage, social guarantee systems, and public services, in such a way that civic society and capitalism mutually encourage one another (Marshall [1949] 1977).

Furthermore, learning effects also occur in the process of social change. Rapid developments in one society serve as models for change in other societies. This statement applies both to positive developments and to instances of pathology such as refusals to work and protest movements.

Thus change means that altered or even new actions or modes of behavior generate a whole series of ramifications, not simply repetitions of the past.

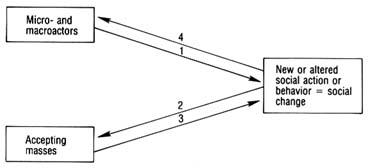

Both microsocial and macrosocial changes occur. Microsocial change is the altering of action or the initiating of new action on the part of a small number of actors who are aware of one another. Macrosocial change encompasses the alternations in action or the emergence of new interrelationships of action that involve many actors who are not aware of one another. Often changes on the macrosocial level can be traced back to changes on the microsocial level: a new or altered action or behavior is always generated or discovered in elementary interrelationships of action and developed as a habit by individual actors in small groups (Relationship 1 of Model 1). The actors attempt to transfer the action or behavior to other groups, or these groups follow suit (Relationship 2 of Model 1).

For example, a new attitude to family size, a new sexual behavior, or a new medical discovery may be adopted initially by a small number of actors before being exhibited to others as a model or gradually becoming appreciated by others and then deliberately imitated. Social change can also be given impetus when new personalities take over macroactor roles, for example, new party leaders and presidents, innovative entrepreneurs and labor union leaders with initiative, church leaders who convey a "message," productive scientists and academics, or imaginative legislators. Individuals and elites with an innovative orientation tend to rise to the top and usher in societal change especially at times of crisis (Nisbet and Perrin 1970, 320).

Change is introduced by either personalities, significant actors, or very small groups who exploit elements of the current social and material situation. If change is to be set in motion by significant actors, it needs to be taken up by many others and introduced into everyday action and behavior. It must be able to be transferred and must allow the

Model 1.

Actors and Social Change

possibility of others adjusting to it. Hence the following distinctions among actors may be drawn:

1. Microactors who introduce alternations but act or behave in isolation and do not succeed in transferring the alternations to others or who do not set any processes of adjustment into action.

2. Microactors who interact with others among the masses and who generate alternations or adjustments.

3. Macroactors who address themselves to large masses, or whose behavior is relevant to them, but whose actions are not adopted or whose behavior has no effect.

4. Macroactors who assert themselves in processes of transfer and adjustment.

Action or behavior carried out on a mass scale—or its rejection—(Relationship 3 of Model 1) affects the position of the micro- and macroactors producing the innovations (Relationship 4 of Model 1). Mass acceptance of new actions and modes of behavior strengthens the innovators' positions in the first instance. The initial effect is one of creating prestige. Soon, however, the actors thus singled out become relatively weaker as the accepting masses improve their living situations by adopting the new action or mode of behavior. Nothing much has changed for the original innovators. They had already been able to put these actions and behavior modes into practice, and in the long run they are unable to derive advantage from the gratitude of the accepting masses. These interrelationships are laid out in Model 1.

Parsons's differentiation between change within the system and change of the system (1951, 480) is no more than a relative distinction. The mass of microactors within an interrelationship of action are able to bring about as much change as can successful macroactors from without: the end result in either case is the emergence of a new relationship of action. The

classic illustration of the first case is the American Revolution. At the outset none of the macroactors, nor any small group, had any notion of the action interrelationship that was later to arise in North America. Yet step by step the actors and groups moved away from the status of being a British colony: "I never had heard of any Conversation from any Person, drunk or sober, the least Expression of a wish for separation, or Hint that such a Thing would advantageous to America" (Benjamin Franklin, cited in Rossiter 1956, 41).

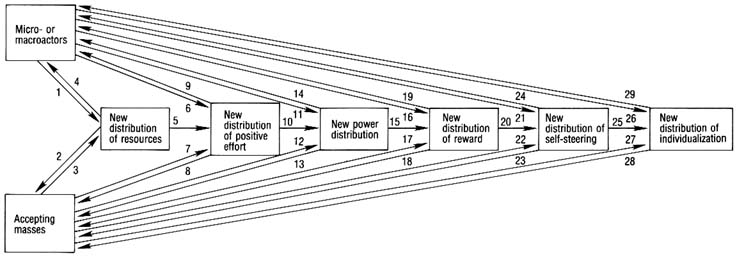

In modern societies, as elsewhere, the chief concern is with a secure and better life, which first means survival, then living the good life. This, however, can only be achieved if in each case a certain new level of resource mobilization can be attained. Anyone wishing to survive or to raise his or her living standards has need of the assistance and cooperation of other actors. These other actors, as carriers of resources, can be activated (Relationships 1 and 2 in Model 2) to generate additional positive achievement if they are promised rewards or threatened with punishment. Because rewards provide a stronger motivation to produce the desired positive effort than punishment, elites substitute rewards for punishment as the production of goods and services grows (Haferkamp 1983).

To refer to Model 2, raising the resource potential (Relationship 3) has the unintended consequence that those in possession of the new resources become more important in relation to the owners of the old resources (Relationship 4). This means that the new resource holders are able to generate more positive effort in comparison with other important micro- and macroactors (Relationships 5–7) and that the relative weights of positive effort are altered (Relationships 8–9). But now some power needs to be conceded to the new carriers of achievement, so that power is ultimately shared with them. This sharing of power affects the distribution of rewards (Relationships 15–19) and the possibility of self-steering (Relationships 20–24) and individualization (Relationships 25–29).

The trends toward growth and downward distribution are the unforeseen consequences of the mobilization of resources that occurs in all stratified societies. If this path is not taken and resources at the lower levels of society are left unutilized, societies remain below their potential level of performance. If no drive is made to raise the level of achievement among the masses, less power is generated than is possible. And if power is not shared and the interrelationships of action are controlled not by increasing rewards but by the use of punishment, then the forces at the top ruin the very interralationships of action they wish to profit from. The historical examples of the fall of the pharaonic empires (see Wittfogel 1938) and the major problems faced by socialist societies in the present day come to mind in this regard (see Senghaas 1982, 277).

Model 2.

Actors, Growth and Downward Distribution

The arguments formulated thus far serve to explain many different developments. Resources are exploited to a much greater extent in modern societies than elsewhere. This has had many consequences, the most immediate of which is the greater part entrepreneurs have played. It is possible to continue in this vein and explain many differences between modern societies and nonmodern ones. But let us turn to the end of the chain of influences, to extreme individualization. It is particularly advanced in the United States and least developed in Japan; Western Europe, including West Germany, lies in between. Evidently, however, the degree of individualization is not correlated with resource mobilization, for in this respect there are no telling differences between the United States and the German Federal Republic, and Japan is remarkable for its particularly high degree of mobilization.

Even among the intermediate links in the causal chains of Model 2, the combination are not maintained as we would expect. Can it be said, for example, that in the United States, with so many subcultures, we also encounter the highest measure of political participation in general? Or that in West Germany, with its pronounced leveling of authority, we find the work performance at the lowest levels that would be appropriate to such conditions? And how can the incidence of counterdevelopments and pathologies be explained? Do we find that the production of toxins and pollution is at its highest level where the most resources have been mobilized? Do minorities have a particularly strong blocking power where the spreading out of achievement-orientation is especially advanced? Why do resources for achievement remain unused? Why do monopolies of power exist that are not based on appropriate achievement? Something more than just resource mobilization and its consequences needs to be added to our model of actors and interaction efforts if we are to understand and interpret the development of modernity. I believe that two other additional factors are essential:

1. Contractual action, which makes everything, including ascription, the object of negotiation.

2. Radical values of equality.

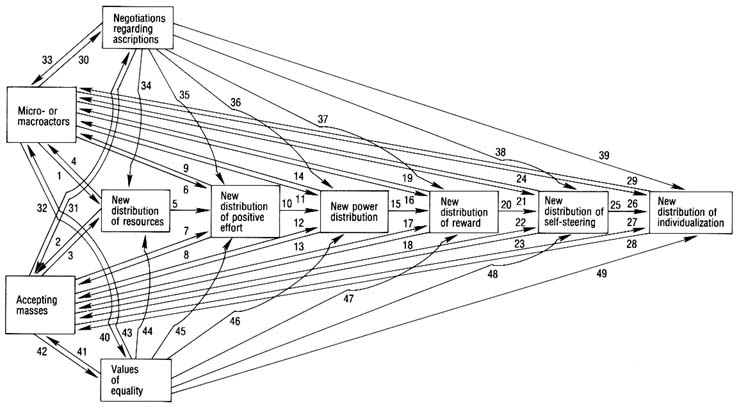

Both factors are typical of modern societies, albeit in different ways from one society to another, and they are the most significant elements of action in these societies. The influence exerted by these two factors on the change toward individualistic modern society is presented in Model 3. This model shows the complex relationship between the fundamental processes of change and the hallmarks of modernity. Macroactors, together with microactors endowed with initiative, assign others to a place in the status hierarchy (Relationship 3 in Model 3), and their ascription are either accepted or rejected (Relationship 31). When significant actors

Model 3.

Actors, Growth, Downward Distribution, Negotiations Regarding Ascriptions, and Values of Equality

interact with the accepting masses, recognized ascriptions emerge (Relationships 32–33). These ascriptions then have effects on the various types of distribution (Relationships 34–39). Actors also create new values (Relationship 40), which are either internalized or rejected by the masses (Relationship 41). This interaction leads in turn to a recognized system of values (Relationships 42–43), which also exerts its influence on all the distributions (Relationships 44–49).

In the following section I concentrated on contractual action regarding the ascription of positive effort, how this trend became widespread, and how it influence the processes of social change that lead to modern societies (Relationships 30–39).

3. Contractual Action and Ascription

The two most important processes involved in the "transition from simple/primitive societal organization to complex/differentiated [organization are] … (1) increasing differentiation and specialization of social functions, and (2) the replacement of ascriptive principles by achievement principles for societal organizations" (Strasser and Randall 1981, 74). I assume in Model 3 that the first process exists, as shown by the chain of relationships leading from resource mobilization to individualism. I have not, however, found that the second process is actually taking place and thus I omit it from my models.

By a change from ascription to achievement principles, sociologists generally mean that there are few characteristics that are solely ascribed to particular actors. Status in particular is no longer simply accorded to a person or group but is acquired by virtue of abilities and measurable success in specific activities. One important consequence is that status in the family system, or any other ascribed status, now plays an ever-smaller part in comparison with status acquired by objective achievement, which is usually based on occupation.

I question this dichotomy and make the following alternative assertion. Modernizing societies emphasize greater achievement, and more positive effort is actually accomplished. Thus achievement is truly an important part of modern societies. Yet more ascription also occurs in modern societies. The paradoxical result is that both more achievement and more ascription arise and that achievement is to a considerable extent ascribed.

Achievement, or making positive effort, means solving problems in life, whether one's own or someone else's, or at least making a contribution to their solution. Not only is such achievement or effort ascribed, but it is also generally measurable. The following observations can therefore be made to avoid constructing a mistakenly one-side theory of ascription. Actions carried out by actors can be distinguished according

to whether or not these actions make a contribution to solving fundamental life problems, such as whether people are dead or alive, sick or healthy, hungry or well-fed, imprisoned or free. These straight-forward differentiations are fundamental life problems that, in modern societies as anywhere else, constantly cry out for solution (see Haferkamp 1991, 311). Although further life problems can be defined and needs shaped and manipulated (Hondrich 1973, 60), these activities cannot be undertaken until the basic problems have been solved. Even holders of power are not able to define all life problems or needs in such a way that they gain greater advantage for themselves by labeling basic life problems as the problems of others that they happen to be able to solve themselves.

Interactions, groups, and interrelations of action in modern societies not only may live on or develop further, but also may decay or self-destruct. Achieving, or generating positive effort, therefore has as its opposite the causing of damage, which occurs whenever solving life problems is prevented or impaired. Damage, like achievement, is objectively measurable and subjectively ascribable. Instances of achievement or damage can be identified by actors in everyday life through observation, even in modern societies. Analysts are able to recapture such processes, which could involve, in the case of achievement, an entrepreneur's success in the marketplace, the output produced by an employee, the trouble-free handling of administrative procedures, or the discovery of new knowledge by an academic (Bolte 1979, 22). All of these are achievements that are measurable in objective terms.

When achievements are generated by several actors, measuring the level of achievement becomes a more complicated matter. Even in these cases, however, it is possible to make objective observations. Insurance companies are constantly refining their schemes for assessing the risks of the actions of organizations and corporations. Banks develop guidelines on credit, making judgment about the ability of borrowers to perform and grow in major interrelationships of action. These examples involve estimates of likely achievement. And at a higher level analysts make measurements of economic growth and progress for entire societies (Senghaas 1982, 136–37). To complete the picture, it is also possible to ascertain the extent of damage and destruction. Measurements may range from the assessment of bodily damage by medical experts to measures of the decline and fall of whole societies (see Wittfogel 1938).

These observations by no means rule out alterations in the values measured. Such alterations are especially evident in the changing view of nuclear power in modern societies in the mid-1980s. Something that had long been treated as an outstanding achievement is now—as the risks

become more evident—being scaled down accordingly. Also, measurement and objective assessment are not rendered impossible by the fact that a long period of time sometimes elapses before actors realize that something either preserves or destroys life.

These remarks on the possibility of identifying achievements are necessary to avoid creating the impression in the arguments that follow that the evolution of instances of achievement or damage are based solely on ascription.

Achievement and damage may be objectively measured and subjectively ascribed at one and the same time, for actors treat achievement and damage no differently than they do other elements of their life-worlds. Not only are these elements represented by actors within their consciousnesses—with greater or lesser degrees of success—but also they are defined from the outset, just as every situation of every actor is defined.

Ascription means that an actor assigns certain characteristics to other actors irrespective of whether these other actors have these characteristics in reality. In other words actors deal out labels to other actors. A vivid illustration of this is the ascribed ability to perform witchcraft or to obtain divine action. These are extreme cases in which either damage leading to infirmity or death or achievement leading to healing is attributing to individual human beings in the absence of any objective evidence. Ascriptions, however, can be investigated to determined whether or not the ascription is based on achievement.

Of course, false ascriptions may arise—a false accusation of murder (see Becker 1963, 20), or a false paternity Charge—but they are the exception, not the rules. It is wrong to take exceptions from everyday life or oversubtleties raised by analysts and elevate to the level of general rules. Since its beginnings science has been driven by the intention of being able to described and explain reality more fully and more correctly than can actors in their life-worlds. To dispute that science does this is tantamount to lagging behind Comte and, even more so, behind the sociologists who followed him. Durkheim, Weber, Simmel, and Mead would have little sympathy with the skepticism so widespread in sociology today about the possibility of making statements that reach beyond the knowledge of the life-world.

Certainly one is bound to admit that there are many cases that lack such straightforward reference points as life and death, health and sickness. On the contrary, social relations are complex, and it is absolutely impossible to provide a totally correct, faithful image of this complexity. It is possible, however, to carry out objective measurements of individual or partial achievements. yet aggregating these measurements is a difficult and at times extraordinarily complex process. Moreover, levels of

complexity are rapidly attained that no human consciousness is able to picture, even in aggregate terms. Actors circumvent this difficulty when they reduce complexity by using ascriptions. Matters are then selected and simplified. Some aspects are singled our for particular attention. others are generalized, and this mixture is understood as a judgment about reality (see Schutz 1964–67). Even these ascriptions, however, maintain a link with reality, for the aspects subjected to representation, selection, overemphasis, or generalization are indeed characteristics of reality in the first instance.

In the majority of cases ascriptions take place unintentionally. However, one can also consciously put forward a distorted ascription. Actors knowingly exaggerated their won achievement and deliberately understated that of their adversaries. Ascriptions in this sence have always existed. Establishing their existence is a sociological banality. More difficult questions, however, concern the alterations involved in processes of ascription and their effect both on social change and on developments leading toward, and taking place within, modernity.

Reduction of complexity is usual underlying motive for ascription. Since the advent of large-scale productive organizations, expanded bureaucracies, economies organized on the basis of a division of labor, and stratified authority groupings the generators of achievement are complex in themselves. The output produced by many workers on one payroll, and even the achievements of a single entrepreneur or politician with a large supporting staff at his or her disposal, is mainly ascribed to a group, and most of all to a large group, such as the work force, the party membership, the management, or the government (Office 1970). Such ascriptions occur even though objective measurements of achievement and aggregations are possible. The "structuring practices of agents" can be seen in operation and "summary representations" can be asserted by the analyst. The best example of this is econometrics (Knorr-Cetina 1981, 34). Another example is the presentation of the "state of the union."

Below this level in modern societies the ascription of achievements occurs with regard to actions and the results of actions in diverse occupations and related positions. Within any one occupations ascription are founded on the ascribed quality of typical occupational activities as well as on the quantitative aspects of work produced. In other words we find ascriptions of important and less important positions. Moreover, the ascription of the ability to cause damage in modern societies is also bound up with large grouping of nations and occupational and related groups. This observations becomes obvious when talks take place between management and striking workers. Both sides ascribe damage-causing

action to the other. Similarly, harmful actions are ascribed to terrorists, professional criminals, a foreign power's military leaders, and the leaders of sects.

Increasing complexity leads to increasing differentiation. The result is that there is no guarantee that ascriptions made by an ever-greater variety of actors will in any way become uniform. In principle one would expect each actor to develop his or her own ascriptions based on his or her individual social and biographical situation. Empirically, however, the actor frequently encounters a closed and rigid system of ascription. Such systems arise in homogenous, closed societies as well as in traditional societies, and they are always present under conditions of oppressive authority. This is quite natural, for uniform ascriptions ensure that interactions will be predictable, which is typical for these types of societies. Once an action or actor is evaluated in the public eye a worthy in terms of achievement, then what that actor can lay claim to is also established. This process occurs against the background of force in societies with a strong ruling authority. In such cases ascriptive power is monopolized, with the result that which is produced in the upper levels is recognized as achievement. Thus whoever possesses power generally has ready and more direct access to ascriptive power.

Wherever societies have become more complex and are internally differentiated (through occupational groupings, political groupings, including those of minorities, or immigration) and wherever there have been a large number of external contacts, existing ascriptions become problematic and discussions, conflicts, and struggles over ascription ensue. Such discussions and conflicts are typical of modernity. The ascriptions of the majority stand opposed to those of the minority. Discussions and conflict surrounding ascriptions also arise when the circumstances of power are loosened, especially as a result of the differentiation of functions and functional systems (Luhmann 1984, 186). these debates focus on the following questions: What constitutes achievement? Who has accomplished it? Which achievements are more important than others? Whose actions cause damages? What brings more damage than benefit?

Conflicts over ascription are aggravated when conceptions of equality become established but inequality continues to exist. Equality carries with it a suggestion of ascription: all achieve to an equal extent. For this reason the inequalities that exist need to be justified. Disadvantages and liabilities are also regarded in the population at large as equally distributed. This raises the problem that a disproportionate amount of blame for such action (for example, criminal action) is placed on particular strata, especially minorities. Equality, however, no longer needs to be

justified or provided with a basis because it is accepted as the natural state. Inequalities with regard to power, reward, and negative sanctions are best explained and justified in terms of differences in achievement and the causing of damage. It is for this reason that ascription conflicts focus on these kinds of inequalities.

To gain outside recognition of their own positions, inferior new groups or actors build up self-definitions and ascriptions concerning not only their own achievements but also their share of power and resources in society. In addition, they formulate images of society that explain the existing reality that they believe to be unjust. They construct images of a future society and ascribe to themselves a more important position within it. Their social self-confidence, their sense of social identity, develops, providing a basis on which it is easier to perform actions. For such a self-assessment to be maintained, an internal organization that nurtures self-ascription is necessary.

But self-ascriptions do not remain stable. The various actors try, within achievement relations, to enforce their definitions of their own and others' resources and achievements. Thus there are negotiations about resources and achievements and about a new, more just distribution of power and privileges. Concepts such as "status management" and "stratification policy" are a reflection of these processes. Negotiations mean that actors, groups, or parties attempt to reach agreements about ascriptions and the recognition of ascriptions in their future relations.

Negotiations encourage the tendency toward more equality, for negotiations always imply that communication takes place between the parties involved and the willingness to communicate confers a sense of legitimacy on the other party. Thus either party may oppose a particular proposition or set certain conditions. This process of negotiation can progress to the point where elites themselves accept conceptions of equality and only ascribe achievements of equal value to themselves, as has been true of members of the nobility in many bourgeois and proletarian revolutions.

The crucial point is that modern ascriptions are not necessarily correct just because they emerged from a process of negotiation. Some evidence suggests that definitions of the situation are more adequate if large numbers of actors from various positions participate in shaping them, but there is no guarantee of the correctness of mass ascriptions. The persecution of witches and of the Jews, each of which was supported by large majorities, makes this point clear.

Finally, in modernity ascriptions are of a less lasting character. One may observe a permanent state of change. Groups are continually appearing on the scene with new demands that repeatedly lead to ascription struggles.

4. An Explanation for Differential Rates of Achievement in Two Modern Societies

There are many developmental processes that can be explained using the frame of reference described above, and negotiations about the ascription of achievement and damage play a central part in them. Negotiations are conducted in a similar way with regard to resources and power, rewards, rights, abilities to engage in self-steering, and individualization. Moreover, the road to modernity is a trend away from the monopolization of the power of definition by elites in favor of the downward distribution of this power. I demonstrate this trend by examining changes in achievement ratios in the United States and the Federal Republic of Germany. This empirical analysis also includes references to Britain and France because these societies strongly influenced developments in both the United States and Germany.

The initial determining factor for the development of modern societies is the mobilization of increasing amounts of resources. The most important stages in this process for modern societies have been the modernization of agriculture, the industrial revolution, the modernization of commerce and transportation, and the educational revolution. these phases of resource mobilization bring about alterations in the relations pertaining to achievement and other factors. Europe in general and Britain in particular long played the leading part in continuously mobilizing new resources. Today resource mobilization in the United States and Western Europe is much similar. If we examine the differences in the downward distribution of achievement in the United States and West Germany, it is clear that observable differences in the mobilization of labor and power and in education are insufficient to explain the contrasts in achievement. Nor is there any essential distinction between the United States and West Germany with regard to the ascription of significance to resources. Factors other than the mobilization and distribution of resources must therefore be responsible for differentials in the distribution of achievement in these two societies.

Similarly, there are no significant differences in the overall levels of achievement in the United States and West Germany. For example, performance ability in the two societies—measured in terms of the growth of gross national product per head—is moderate in both cases (World Bank 1985, 175). An examination of who, according to objective criteria, accomplished achievements shows sharp increases in the levels of achievement in the lower strata in both societies. These increases can be traced back over more than a hundred years.

The industrial revolution, in particular, brought substantial change in potentials for achievement. Entrepreneurs, and indeed the urban middle

class in general, were able to offer their new approach to economic and other activities. They gave many microactors the opportunity to achieve. Using new machines, industrial workers produced a huge new range of commodities. To do this they had to demonstrate orderliness, discipline, willingness to work, and physical application, none of which were by any means achievements to be taken for granted. At an early stage supplementary large groups of highly qualified workers were sought (Geiger 1949, 87–88). The larger leap forward in achievement, however, was accomplished by the dependent masses and no longer, as in the period preceding and following the French Revolution, by the bourgeoisie. The bourgeoisie had already attained a high level of achievement at the time of the great political revolutions and could not improve much more on that level. The masses, however, did not emerge from the shadows of economic developments until the industrial revolution.

From around 1860 until the present day the increase in the achievement of the masses in productivity terms has been impressive. This increase has been particularly evident in Sweden and other Scandinavian countries but increases in achievement in Germany and in the United States have also been significant (Kuznets 1966, 66–65, 73). Economic growth in both Europe and the United States during this period can be attributed to a great extent to increased efficiency in the labor force (Kuznets 1966, 72–81, 494). Even in recent times major increases in the productivity of labor as a factor of production are still being accomplished. Annual increases in this statistic in Federal Germany fluctuated between 1.5 percent and 11.3 percent during the period 1960–84 (Statistisches Taschenbuch 1985, Table 3.3). Productivity per employee-hour increased during the period 1960–84 at annual rates ranging from 1.3 to 6.5 percent (Statistisches Taschenbuch 1985, Table 1.7). Very recent investigations confirm the gain in significance for human labor power (Kern and Schumann 1984). Angelika Schade has concluded that all data "support the contention that there has been a consistent, longterm increase in the efficiency of the masses" (Schade 1986, 75).

At the same time that the efficiency of the masses has been increasing, evidence in several spheres indicates declining achievement among elites. First, economic growth in both the United States and Germany is attributable less to the propagation and deployment of capital than to the raising of labor productivity (Kuznets 1966, 72–81). Second, the elite in Germany has proved to be a political failure several times in succession. Instances include the failure to moderate the policies of Kaiser Wilhelm II, the lack of identification with the Weimar Republic, and the failure to resist national socialism (Mayer 1980, 167). In contrast to these failures, in the years since World War II the German elite has made many significant achievements including guaranteeing authority and undertaking

democratic, economic, and sociopolitical reconstruction. However, in comparison with earlier historical periods the tasks undertaken and fulfilled have been narrower in scope (Baier, 1977). In the economic sphere entrepreneurs have functioned poorly in the modern period, particularly beginning in the mid-1960s. They are too strongly oriented to the short term (Vondran 1985, 42) and are one-sided in the emphasis they give to technical developments (Mayer 1980). Hence bankruptcies, crises, and mismanagement among big-name corporations are not unusual (Wurm 1978, 184). This situation is not substantially different from that in the United States where elites have failed, the race problem providing a case in point. In recent decades in particular U.S. leaders have had to live with significant political and military defeats; and the rates of economic development are not significantly different from those in West Germany.

The lack of differences between the United States and West Germany in the objective achievements of the upper and the lower reaches of society does not explain the achievement ratios discussed in the introduction to this chapter: namely, that German elites tend to be less capable and American elites more capable of achieving, whereas German working people are more efficient than their American counterparts. To explain this difference one must take into account an ascriptive effect that arose before the industrial revolution and still affects the situation today.

By the fifteenth century (at the latest) economic action interrelationships began to emerge in a differentiated form. Their potentials for creating either achievement or damage were measurable in terms of protecting against external threats and offering monarchs and nobility possibilities for using force domestically. These interrelationships gave rise to what marks the beginning of modernity: the first significant conflict over ascription. A new group—the bourgeoisie—was accomplishing important achievements, and it was ascribing these achievements to itself in a process of self-definition. This process culminated in the description of society as a whole as "civil society," a definition first successfully asserted with the bourgeoisie's ascriptive victory in the United States. Before the American Revolution Americans ascribed the achievement of solving all basic societal problems solely to themselves. From this point of view the British sovereign was solely interested in collecting taxes. The First Congress made an appeal to the people in England: Did we not add all the strength of this large country to the power that chased away our common foe? And did we not leave our native land and face sickness and death to further the fortune of the British crown in faraway lands? Will you not reward us for our zeal? (Adams and Adams 1976, 105–6). The small number of representatives

of the British crown had nothing of equal value they could set against these self-ascriptions by American macroactors.

The situation in Germany was very different. There, the bourgeoisie attempted to import the outcome of the French Revolution. The ascriptive victory that the French bourgeoisie won can be explained by the greater weight of its achievement. Already before the revolution the bourgeoisie, because of its successes in craft trades, technical achievement, industry, and commerce, had attained a far greater importance than the king, with his absolute power, and the nobility, which had some share in his ruling authority (Claessens 1968, 132). At the same time the Third Estate had the more able agitators among its own ranks. Whenever Louis XVI's spokesman faced the advocates Saint Just and Robespierre, they invariably got the worst of the situation (Jonas 1982). Other important and like-minded actors who intervened in the ascription battles were radical philosophers and apostate priests, who could do nothing other than ascribe. Abbé Sieyès is known to have posed the rhetorical question "What is the Third Estate?" and then immediately answered, "Everything." A handbill distributed at the time shows a person from the Third Estate carrying the king, nobility, and clergy on his shoulders. Despite the bourgeoisie's ability to achieve, this image was an exaggeration; yet this incredible overestimation of itself was common throughout the Third Estate (Jonas 1982).

Third Estate agitators even succeeded in enforcing the bourgeoisie's self-ascription on other groups as well: the nobility itself propounded ideas of equality, and the priests who remained in office were no longer convinced of their special status (Jonas 1982). This situation provided the basis for the forced dissemination of notions of equality. Thus the ascription struggle between the very top and the very bottom had been decided before the French Revolution actually occurred: "Whoever heard the theories propounded at [in the late eighteenth century], and the fundamental principles tacitly but almost universally recognized … could not have avoided coming to the conclusion that France as it then existed … was already the most democratic nation in Europe" (Tocqueville 1967, 130). The conflict culminated in the French Revolution and a convincing ascriptive victory for the bourgeoisie. This victory ensured that this stratum's superiority in achievement found recognition and that it was established for posterity.

Ascriptions, once established, can endure for long periods. Thus even today the French elite—the bourgeoisie—is still able to claim entitlement to a particularly large portion of the national income (World Bank 1985, 229).

In Germany the situation was different. The Prussian bourgeoisie in 1848 had neither the accomplishments nor the self-confidence of its

French and American counterparts. The leading positions of state in Germany were occupied by actors who were strong achievers and who successfully asserted their right to fulfill important tasks, speaking of themselves as the first servants of the state. Even allowing for the effects of the ideology of equality and the bourgeoisie's ascriptive activities, the bourgeoisie could not hope to win ascription conflicts with the ruling class. Thus, after a short period of insecurity among the rulers as to what role they should play, the course of events in Prussia led to reaction.

To this day the bourgeoisie in the Federal Republic of Germany does not have recourse to any enforced recognition of achievement, as do the bourgeois strata of France and the United States. Hence the different levels of ascriptive success of the business bourgeoisie in Germany and the United States play an essential part in determining the differences in recognized achievement ratios. The recognized achievement of the elite is less in West Germany than it is in the United States. The masses in West Germany, however, proved particularly able to ascribe special achievements to themselves.

Although workers in Britain, Switzerland, and Belgium (the three European societies then more industrialized than Germany) had an awareness that they had an important but disputed position in society, they were not able to combine this awareness with a sufficient number of actors who could organize themselves, go on the offensive, and assert this self-ascription. The first attempts at enforcing this self-definition were the foundings of trade-union umbrella organizations in 1868 in Germany (about twenty years after the commencement of industrialization) and in Britain (about one hundred years after the take-off period). Other nations did not follow suit until very much later. More significant than the foundings of trade-union umbrella organizations was the formation of workers' parties. These parties not only put worker self-ascriptions into effect in labor disputes and negotiations but also involved workers in all aspects of the public negotiating processes in which political parties normally express their positions. Not until after 1885 did workers' parties come into being in Britain, Switzerland, and Belgium, whereas actors in Germany created the Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein (the General German Workers' party) as early as 1863 under Lassalle in Leipzig, followed in 1869 by the Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei (Social Democratic Workers' party) or SDAP under Liebknecht and Bebel in Eisenach. The macroactors Lassalle, Liebknecht, and Bebel formulated self-ascriptions for industrial workers that could not have been clearer. The self-ascriptions are not surprising if one bears in mind that two of Marx's major works appeared in the years 1848 and 1867. The fact that Marx's first works were published in German was undoubtedly a major reason why workers self-ascription was first put forward by German industrial workers and their

leaders. This new self-awareness is evident in the Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein 's federation anthem:

Mann der Arbeit, aufgewacht

Und erkenne Deine Macht!

All Rader stehen still,

Wenn Dein starker Arm es will!

Man of labor, now arise!

What power is yours, if you have eyes.

All the wheels grind to a stand,

If this be the wish of your strong hand.

Like the French bourgeoisie, the self-image of the German workers tended to exaggerate their own importance. But Marx and the labor movement's leaders succeeded—in what, given the prevailing perception of the role and significance of employers, was basically a hopeless situation—in providing industrial workers and their organizers with a strong self-assurance using this self-definition.

As we know, not only does no workers' party exist in the United States to this day, but the level of union organization there is one of the lowest in the world. At the outset of unionization in the United States moderation was already prevailing. Faced with that situation, the leaders of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), Samuel Gompers, deemed it advisable to be invulnerable to attack. After the turn of the century he proclaimed that the demands of the AFL had nothing in common with those of foreign revolutionaries and with ideologies advocating a change of the system. He asserted that American workers only wanted more money and reduced hours (Merkl and Raabe 1977, 17). Clearly, given prior conditions, actors in the lower echelons have scored significantly more impressive success in Western Europe than they have in the United States.

If we compare the bourgeoisie's ascriptive success or failure in political revolutions, that is, success in the United States and France and failure in Germany, and these differences are related to the strength or weakness of the working people's self-definition, strong in Germany and weaker in the United States, then the answer to the question of why the recognized achievement ratio is more favorable to the masses in Germany than it is in the United States lies close at hand. The great turn-around as German elites declined at the beginning of the modern period and the specific "lead in achievement" accomplished by the dependent masses in West Germany cannot be attributed solely to an objective rise in the value of the bourgeois strata's achievements in the United States and France, in the first case, and in those of the proletarian strata at a later stage in Germany, in the second case. For, quite apart from the

actual achievement values, there were also changes in the subjective assessments of these values. These changes were the result, on the one hand, of the success of macroactors who appeared on the scene and interacted with the many microactors below and, on the other hand, of the influence brought to bear by egalitarian and democratic norms and values.

References

Adams, Willi Paul, and Angela Meurer Adams, eds. 1976. Die Amerikanische Revolution in Augenzeugenberichten . Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag.

Baier, Horst. 1977. Herrschaft im Sozialstaat. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpolitik 19 (special issue, Soziologie und Sozialpolitik ): 128–42.

Baudelaire, Charles. 1925. Augewählte Werke . Vol. 3, Kritische und nachgelassene Schriften . Munich: Müller.

Becker, Howard S. 1963. Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance . New York: Free Press.

Bendix, Reinhard. 1971. Sociology and the distrust of reason. In Scholarship and partisanship: Essays on Max Weber , by Reinhard Bendix and Guenther Roth, 84–105. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bolte, Karl Martin. 1979. Leistung und Leistungsprinzip . Opladen, W. Ger.: Leske and Budrich.

Claessens, Dieter. 1968. Rolle und Macht . Munich: Juventa.

Ferguson, Adam. [1767] 1969. Essays on the history of civil society . Farnborough, Eng.: Gregg.

Geiger, Theodor. 1949. Die Klassengesellschaft im Schmelztiegel . Cologne: Kiepenheuer.

Haferkamp, Hans. 1983. Soziologie der Herrschaft. Analyse von Struktur, Entwicklung und Zustand von Herrschaftszusammenhängen . Opladen, W. Ger.: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Haferkamp, Hans. 1991. Soziales Handeln: Theorie sozialen Verhaltens und sinnhaften Handelns, geplanter Handlungszusammenhänge und sozialer Structuren . Opladen: Westdeutcher Verlag.

Hondrich, Karl Otto. 1973. Theorie der Herrschaft . Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Jonas, Friedrich. 1982. Soziologische Betrachtungen zur Französischen Revolution . Ed. Manfred Hennen and Walter G. Rödel. Stuttgart: Enke.

Kern, Horst, and Michael Schummann. 1984. Das Ende der Arbeitsteilung? Rationalisierung in der industriellen Produktion: Bestandsaufnahme, Trendbestimmung . Munich: Beck.

Kitschelt, Herbert. 1985. Materiale Politisierung der Produktion. Gesellschaftliche Herausforderung und institutionelle Innovationen in fortgeschrittenen Kapitalistischen Demonkratien. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 14:188–208.

Knorr-Cetina, Karin D. 1981. The micro-sociological challenge of macro-sociology: Towards a reconstruction of social theory and methodology. In Advances in social theory and methodology: Toward an integration of micro- and

macro-sociologies , ed. K. D. Knorr-Cetina and A. V. Cicourel, 1–47. Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Kuznets, Simon. 1966. Modern economic growth: Rate, structure, and spread . New Haven: Yale University Press.

Levy, Marion J. 1967. Social patterns and problems of modernization. In Readings on social change , ed. Wilbert E. Moore and R. Cook, 189–208. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Lockwood, David. 1985. Civic stratification, 1985. Paper presented at conference, Sociological Theories and Inequality. Organized by the Sociological Theory section of the German Sociological Association, 10–11 Oct., Bremen, 1985.

Luhmann, Niklas. 1984. Soziale Systeme: Grundrisse einer allgemeinen Theorie . Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Marshall, Thomas Humphrey. [1949] 1977. Citizenship and social class. In Class, citizenship, and social development , by T. H. Marshall, 71–134. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. [1848] 1964. Manifest der Kommunistischen Partie . In Karl Marx, Die Frühschriften , ed. Siegfried Landshut, 525–60. Stuttgart: Kröner.

Mayer, Karl-Ulrich. 1980. Struktur und Wandel der politischen Eliten. In Deutschland-Frankreich: Baustein zum Systemvergleich , ed. Robert Bosch Stiftung Gmbh, 1:165–95. Gerlingen, W. Ger.: Bleicher.

Merkl, Peter H., and Dieter Raabe. 1977. Politische Soziologie der USA . Wiesbaden: Akademische Verlagsanstalt.

Nisbet, Robert A., and Robert G. Perrin. 1970. The social bond: An introduction to the study of society . 2d ed. New York: Knopf.

Offe, Claus. 1970. Leistungsprinzip und industrielle Arbeit. Mechanismen der Statusverteilung in Arbeitsorganisationen der industriellen Arbeitsgesellschaft . Frankfurt: Europäische Verlagsanstalt.

Parson, Talcott. 1951. The social system . Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

Parson, Talcott. [1971] 1972. Das System moderner Gesellschaften . Munich: Juventa. (First published in English: 1971. The system of modern societies . Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Ronge, Volker. 1975. Entpolitisierung der Forschungspolitik. Leviathan 3:307–37.

Rossiter, Clinton. 1956. The first American revolution . New York: Harbrace.

Schade, Angelika. 1986. Prozesse der Angleichung: Theoretische Ansätze und empirsche Überprüfung . Master's thesis, Department of Sociology, University of Bremen.

Schutz, Alfred. 1964–67. Collected papers . Vols. 1–3. The Hague: Nijhoff.

Senghaas, Dieter. 1982. Von Europa lernen. Entwicklungsgeschichtliche Betrachtungen . Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. (See English translation: 1985. The European experience . Leamington Spa, Eng.: Berg.)

Simmel, Georg. [1908] 1968. Soziologie: Untersuchungen über die Form der Vergesellschaftung . Berlin: Duncker and Humblot.

Statistiches Jahrbuch für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland . Weisbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt Wiesbaden.

Statistisches Taschenbuch. Arbeits- und Sozialstatistik . 1985 Bonn: Bundesminister für Arbeit und Sozialordnung.

Strasser, Hermann, and Susan C. Randall. 1981. An introduction to theories of social change . London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Strauss, Anselm. 1978. Negotiations, varieties, contexts. processes, and social order . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. 1967. Die gesellschaftlichen und politischen Zustände in Frankreich vor und nach 1789 . In Alexis de Tocqueville . 2d ed., ed. Siegfried Landshut, 117–40. Cologne: Westdeutscher Verlag.

UNESCO. Statistical Yearbook . Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization.

Vondran, Ruprecht. 1985. Gemeinsamkeiten und Unterschiede im Management. In Die Arbeitswelt in Japan und in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: ein Vergleich , ed., Peter Hanau, Saburo Kimoto, Heinz Markmann, and Kazuaki Tezuka, 9–46. Neuwied: Luchterhand.

Weber, Max. 1920. Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Religionssoziologie . Vol. 1. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Siebeck).

Wiswede, Günter, and Thomas Kutsch. 1978. Sozialer Wandel . Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Wittfogel, Karl A. 1938. Die Theorie der orientalischen Gesellschaft. Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung 7:90–122.

World Bank. 1985. World development report . Washington, D.C.

Wurm, Franz F. 1978. Leistung und Gesellschaft . Opladen, W. Ger.: Leske and Budrich.

Zapf, Wolfgang. 1983. Entwicklungsdilemmas und Innovationspotentiale in modernen Gesellschaften. In Krise der Arbeitsgesellschaft? Verhandlungen des 21. Deutschen Soziologentages in Bamberg, 1982 , ed. Joachim Matthes, 293–308. Frankfurt: Campus.