PART ONE

GETTING THERE

1

Student Volunteers

(1905)

In March of 1905 we were living in a little apartment in West Lafayette, Indiana. Bob was general secretary of the Student Young Men's Christian Association at Purdue University. He had become keenly interested in the Y during his undergraduate days at Berkeley. After the Lake Geneva Student Y conference in 1902, he decided to put his life into the foreign work of the Y. He was asked to first go through a training period as secretary of a Student Y in America. Several attractive offers came his way, including the Y at Columbia University. He accepted what seemed the hardest and went to Purdue. He had started at Purdue in the fall of 1902, but I had not been able to join him there until after our marriage in the summer of 1904.[1]

About that time we asked the International Committee of the Y if there was a chance we would be sent abroad that year, or possibly the next. The committee thought there would be no opportunity before 1906. Suddenly one day there came a telegram from John R. Mott, the head man of the Y, appointing a time for seeing Bob in Chicago within the next few days. The message seemed to bode some change for us, but we hardly dared hope for anything definite so soon.

March was cold. I shivered when Bob left at 5:30 that morning on his way to Chicago. We both wondered what it might mean. Being alone, I got up

[1] Grace's home was San Bernardino, California, but they were married in Independence, Iowa. Grace's father was adamantly opposed to her marriage, to the extent of disinheriting her and refusing to pay for or even attend a wedding. He disliked having the daughter of a banker (even a small-town one) "throwing herself away" on the son of a farmer; and he disagreed with her determination on a distant and probably dangerous life as a missionary wife. Grace had spent part of her high school years in Independence, Iowa, with her grandmother and a much-loved aunt. They offered the young couple a haven and support. Grace's father finally became reconciled, but only after many years.

2

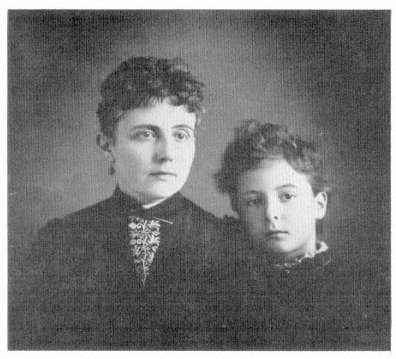

Grace, at about ten, with her mother, Virginia Boggs.

later than usual. The morning chores were still unfinished when there was a telephone call. It was an old Berkeley friend. He had come east unexpectedly on business; finding that he could stop in Lafayette, he thought to surprise us. I told him how to reach us by streetcar and he was there in half an hour. Naturally, he was much disappointed not to find Roy.[2]

After a little visit, I started to show him around. We stopped at the Y, and one of the men there escorted him around the campus. Waiting in Bob's office for their return, I began to think. Obviously our friend would be with me for lunch and there was very little to eat. Delicatessens were few in those days and none. was near us. On the way home we detoured by the grocery store where I traded and found a few ready eatables. I remember that the lunch included Saratoga chips and some of my own jelly.

We were still at lunch when I received another telephone call. This time it was Western Union, where someone realized that if I was to follow the telegram's instructions, I must receive its message at once. A woman's voice read

[2] Bob was christened Robert Roy. His family preferred Roy, and so he was known through his college years. But Grace preferred Bob, and her wish prevailed with the friends made after their marriage. When we children heard someone say "Roy," we knew that the speaker was from away back.

the wire from Chicago: "Appointed foreign work. Will meet you here. Medical examination. Take one thirty train Big Four. Bob."

It was already nearly one and there was not a moment to lose. I hurried to our landlady next door and asked her to kindly gather up my silver and put away the food on the table. Hastily, I snatched up a few things and put them in a small valise. Fortunately, I was dressed for the street and did not have to change. We stopped at the useful corner grocery to get some money. In a few minutes, our friend and I were on the streetcar crossing the Wabash; a little later, we were on the train hastening north. He had decided to go to Chicago with me, as it would give him a chance to see Bob.

It was all tremendously thrilling. Bob met us; he was happy and excited. Very soon I was having my medical examination. The doctor would hardly

3

Grace, between college and marriage, while she was teaching

high school Latin in San Bernardino.

believe that I was expecting a baby in the summer; I was still quite slender. As soon as I passed the doctor's examination, we were definitely accepted for the Y staff in the Orient; but we were not to sail until November.

That evening Mr. Mott talked to us both. I well remember his solemnity and some of his advice. He emphasized that this was a lifework; it was a lasting appointment, not like taking a position with a local Y in America. He repeated that we were set apart by our lifetime commitment. As we listened to his impressive words, we felt that we were making a solemn decision, full of privilege and responsibility. He reported China as on the threshold of vast changes. We would be there in a critical and important time, seeing changes of amazing extent and influence.

It was no wonder that we were too excited to sleep much that night. The only room available in the old Sherman House was for a family, with a huge double bed and two small ones for children. We tossed about in the big bed, rolling over for attempts at sleep and turning back to talk, until the bedding was all pulled loose at the foot. To think that we really were to go to the Orient! Mr. Mott had asked if I wanted to go to Canton where I had an uncle, but we had no preference as to location. China, though, was the land of our dreams.

We stayed on in Chicago for three days. As I was a student volunteer committed to foreign work, Mr. Mott asked me to talk to another wife. The husband was ready and eager for appointment to the Orient, but the wife blocked every offer by persistent objections. I talked, but to no effect; they remained in America. During our Chicago stay we visited Montgomery Ward's huge emporium, famous then for sending supplies to the ends of the earth.[3] We also took advantage of the opportunity for much talk with several experienced Y men who had served abroad.

Soon we were back alone in the little apartment in West Lafayette. We found everything spic-and-span. Our kind Hoosier landlady had cleared my table, put away the food, cleaned up, and taken my silver into her own safekeeping. The whole episode seemed a dream: the telegrams, Chicago, our appointment, our new plans for the coming months.

I was busy and happy that spring, making baby clothes, writing to relatives and friends about our sudden, all-absorbing plans. Bob was taking the track men out for cross-country running those fresh spring mornings. He was very blonde then, and the smooth muscles under his white skin made

[3] This was the beginning of a long association. "Monkey Ward" gave a very useful discount to Y people and probably to other missionaries as well. Through our childhood, the more-or-less annual arrival of a shipment from Montgomery Ward was a joyously exciting event. And the fat, brightly illustrated catalogue was a vivid and sometimes perplexing view of a remote, vaguely known home.

4

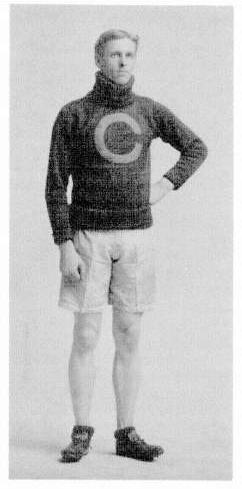

Bob, California's record holder for the half-mile.

him look cleaner than the others as the pack ran past our house. I used to watch for them behind the curtains of our little living room and was always proud of his running style, just as I had been at track meets in Berkeley. I had never seen him lose a race.[4]

During these few months all our wedding gifts and other belongings had to be packed. Orders were carefully made out for Montgomery Ward. Finally, we broke up our first home and started our travels. Bob had agreed to

[4] Bob could run the mile and half-mile well enough to beat Stanford and most other college rivals. But if Grace never saw him lose, it was because she was not able to watch them all. He was captain of the track team in his senior year and set a UC (and West Coast) record for the 880 that lasted for nine years after he graduated.

serve as registrar of the Student Y conference at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. I went out to my grandmother's home in Iowa, where I had been born and where Bob and I were married the year before.

When the Geneva conference was over, Bob came and we soon left for California. My mother had just arrived for a visit but insisted that a pregnant woman, which by this time I certainly was, should not travel without feminine company. So she turned around and came right back with us. Knowing how little practical knowledge Mother had of such emergencies, I have always marveled that she made herself take this journey when she might have enjoyed a summer with her Iowa family and old friends.

We went through Colorado by the Royal Gorge and on by the old Union Pacific. At that time, this trip was considered a marvel. I stood the travel well but was tired when we reached Berkeley.

2

Virginia

(1905)

Bob and I spent July and August in Berkeley with Father and Mother Service in their big home on Oxford Street. We had the large north bedroom, so cleverly planned that it had no north window, but light, air, and views from both east and west. Everyone was lovely to me. Two of Bob's sisters were there at home, and the two younger brothers. Johnnie was thoughtful and pleasant, and Lawrence very kind to his new sister.

In August there was a family reunion. This was an eye-opener to me. My only sibling is a brother twelve years younger; in our family we had no large get-togethers. The Services had nine children; at this time five were married. Twenty-five people lived in the house for over a fortnight. At each meal the Japanese cook served two long tables in the large dining room. For breakfast there was fruit, porridge, huge platters of ham and eggs, coffee, milk, muffins, or perhaps hot cakes. Noon dinners brought the same big platters piled high with steak and onions, or roasts, or perhaps fried chicken. There were tureens of vegetables, mounds of bread, bowls of pickles and jelly, and a favorite dish of my father-in-law's: chopped tomatoes, cucumbers, and onions with a few chili peppers. He seemed to accept me as a member of the family when he found I liked raw onions. Dessert was often watermelon, or there was luscious, real home-made pie. It seemed to me that I had never tasted better food, or any more graciously served, than there in the old Oxford Street home. Now it is gone [burned in the Berkeley fire of 1923], its inhabitants of those days scattered or dead, and even its location lost in experiment gardens of the university.

In those days it was the custom that as soon as the Sunday midday dinner was done, all the Orientals who worked in the big homes had the rest of the day off. About four o'clock one would see a regular procession of sedate Chinese and Japanese cooks, mostly in blue serge, wending its way to the ferry

trains for San Francisco. The Chinese wore clothes of their own style with short, full-cut upper garments and loose trousers; the Japanese preferred Western garments.

With no cook in the house, Sunday supper was prepared by each to his or her pleasure. I realized why my mother-in-law kept one pantry locked. Whole tins of sardines and shrimp would disappear. Jars of pickles would be emptied. Loaves of bread would vanish under the sandwich knife. Fruit was bought by the lug box. All supplies were on the generous scale of the ranch life to which the family had long been accustomed.[1]

The big house with its eight bedrooms and extra attic space held us all easily. The days were full of trips to the City, visits with friends here and there, and good times of many kinds. Evenings we played games, talked, or sang around the piano. They were all fond of music. There was little to attract us from home, for in those days there were no movies. Lulu had already broken the family circle with her recent marriage and departure for Germany; now and then we would think of our own coming separation.[2]

Needless to say, I stayed by the house and did not venture on city jaunts. During the reunion, it seemed once that the time had come and I went to the hospital. After a fruitless wait of several days, Bob came for me one evening. In a raincoat, with my two pigtails tucked inside, I went off on the Oxford streetcar. Home again, and no baby! It was discouraging.

A few days later, on August 26, there were sharp summons. Bob phoned the doctor. I was dressed and roaming about upstairs. I drifted into Irene's room, from whose window I could watch for the doctor's arrival. One of Irene's precious possessions was a china cabinet, a glass-doored case standing on what was really a bench. I thought the two were one solid piece of furniture; in fact, they were unattached. On the shelves were two or three dozen china teacups and saucers. She was "getting a collection," quite a fad for young women at that time. I sat down in a low rocker in front of the cabinet. I had seen the china frequently, but some new thing caught my eye and I opened one of the glass doors. Just then a sharp pain came; l involuntarily leaned back. The arm of the rocker pressed upward against the lower edge of the open cabinet door. This tilted the whole case backward. I was frightened and quickly leaned forward: the case pitched forward with a hid-

[1] Bob's father (our grandfather) had come by wagon train to California in 1859. In 1868 he bought land near Ceres in the San Joaquin Valley and farmed there until he retired in Berkeley in 1899.

[2] Lulu, eighteen months younger than Bob, was his closest sibling. In June 1905, just before the arrival of Grace and Bob from Iowa, she had married Fred Field Goodsell, a UC classmate and close friend of both Grace and Bob. The Goodsells had to leave at once for Germany, where he was to study theology. They later spent many years at Constantinople, where he was field secretary for the American Board. He ended a notable career as the executive head of the Congregational mission board (ABCFM). Fred Goodsell served with the YMCA in Europe and Russia during World War 1, but the missionary paths of brother and sister never crossed.

5

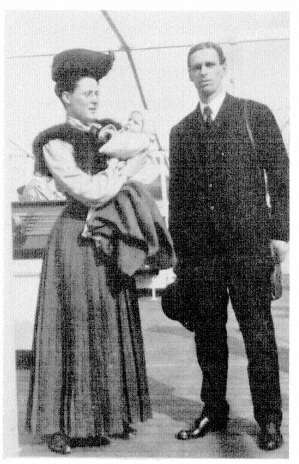

Grace with baby Virginia, in Berkeley before they sailed to China.

eous sound of shattering china. Screaming, I pushed it level on its bench. But not before most of the china had crashed to the floor.

I called for Bob and rushed to our room. He arrived, and soon his mother, and I sobbed out the story. At this moment the doctor arrived and I left the house bathed in tears. Irene, still downstairs and all unconscious of the havoc in her room, came to the front hall to bid me good-bye. She was alarmed to see me in tears, thinking I must be suffering terribly. The doctor, in turn, inquired as we drove off, "Why so many tears? Could things already be so bad?" My husband's family was perfect in its understanding and forgiveness: never was this incident remembered against me.

The long-desired baby was born about two in the afternoon, without the

doctor. He had gone out on calls in the forenoon, and his car broke down. Virginia arrived safely, however, with two nurses at hand. She was tiny, a blonde with large violet eyes. The hospital was the first "Alta Bates Sanatarium" on Dwight Way in Berkeley. She was one of the first five babies born there. Her picture was taken, along with the others, and [in 1937] hangs in the hall of the new building.

Bob was pleased that his child was the first granddaughter in the Service family. He left the day after her birth for a YMCA conference in New York, being already late by waiting for her arrival. Lawrence was the first of the Oxford Street folks to see the baby. He came slipping in when she was a couple of days old, telling me that he was giving her a gold ring. (This was later stolen in Chengtu.)

After I was able to be up and had spent about a fortnight at home, I traveled down to San Bernardino with the baby. I spent October there in my own home; then along came Bob, and partings began. Of course it was hard to say good-bye; but we were young and in love, and going together where we wanted to go. The separation was not as hard for us as for our parents. My father was still opposed to my marriage. I was sorry for Mother, who seemed lonely. It was a little different in Bob's case; his family was large and had a strong group feeling. We were soon back in Berkeley, doing the last packing.

Our appointment had first been for Seoul, Korea. This had now been changed to Chengtu, the capital of Szechwan Province in the far west of China. We were very thrilled: we wanted most to go to China and were excited to be going to a remote pioneer station in the far interior. We looked up Chengtu on the map and tried to visualize the long river journey. Hearing of some Methodist missionaries in Illinois who had been stationed in Chengtu, Bob had stopped to see them en route from New York. They gave him some information about travel, and the wife thoughtfully sent me a note to be sure to take lace curtains "for the home touch." I dislike lace curtains, save very fine ones, which I could not afford; so we purchased none and never regretted their lack. It is difficult to advise people who go to live in foreign places; essentials to one are not needed or desired by others!

In Chengtu, Bob was to be working with Dr. Henry T. Hodgkin of the Friends' Foreign Missionary Association. He had been prominent in the British student movement, and Mr. Mott had wanted him for the YMCA. However, Dr. Hodgkin was already committed to his own church's mission and could only agree to give some time and assistance to the Y. Bob was chosen as his associate because of his experience in American student work, at that time in the high tide of its popularity and influence. Chengtu was becoming a center in China of the new Western-style education. It was a logical place for the Y to establish an Association that emphasized work with students.

3

Shanghai

(1905)

Our ship was the Mongolia of the old Pacific Mail Line. A crowd went to San Francisco to see us off on November 16, 1905. There were relatives and college friends and a few Student Volunteers among the Y men. To us it was a thrilling, exciting day. We sailed at noon and it was warm in the sun. I was wearing a pongee blouse and a blue wool plaited skirt with a blue broadcloth-covered, dishy, pivot-on-the-corner-of-the-head hat, neat and stylish according to the dictates of the day, but impossible to keep steady in sea breezes. Standing on deck to catch last glimpses of the Seal Rocks as we passed out from the Golden Gate, I did not realize how chill the fresh wind was. The next morning I woke with a stiff neck and a cold which threatened croup. This kept me in the cabin, where there was also the small baby demanding my care. And I had a touch of seasickness. Bob had to turn in and care for the two-and-a-half-month-old baby, who was good as gold.

Traveling companions were the Leisers of Wisconsin, whom we had come to know and love in the summer of our honeymoon. They were going for the YMCA to Canton, but she was taken ill in Japan and had to stop there for medical treatment. Winnie Leiser helped Bob care for Virginia during the few days when I was laid low. But that was soon over, and when we began to appear on deck Virginia was a center of interest. She wore a white angora bonnet for the cool sea air of the winter trip.

At our long dining table a missionary gentleman sat beside me. He went down the menu every meal, never slighting a single course. At dinner there was usually an item called "punch." This was a frozen frappé, served after the entree. He saw me eating some one evening and asked what it was. I told him. "Has it any liquor in it?" "Not that I can tell." "Well, I must have some then. I'm sorry I've missed it." He ordered a serving at once and every night thereafter.

6

The young family on shipboard, starting their trip to

China. Grace's hat was"neat and stylish, according to

the dictates of the day, but impossible to keepsteady

in sea breezes."

Fifteen years later, going down the Yangtze in a time of warfare, this gentleman boarded our steamer from a launch in the early hours of the morning. He was escorting some Americans out of a fighting zone in Hunan. He recognized me as soon as I stepped into the saloon for breakfast, and began to ask questions about Szechwan. I, in turn, inquired about Hunan and the dangers through which his party had just come. They had had a narrow squeak to get through some opposing armies. He interrupted me. "How about the food here? I've not traveled by this ship before. Are the hot cakes good? What is their best breakfast dish?" I was thankful that he could forget his narrow escape in a good meal. But not so the couple he had escorted. They had completely lost their nerve, and the husband made no bones of saying that he would not return to Changsha for even a thousand

American dollars. I asked, "Well, what about Mr. ——— who brought you out? He tells me that he is going back very shortly." "He speaks the language and is used to it all," was the reply.

During our stop in Japan there were great demonstrations celebrating naval victories in the war against Russia. I remember a huge floral arch to Admiral Togo near the station on our arrival in Tokyo. Bob attended a big reception in a Tokyo park. All men were to appear in frock coats and top hats; many queer outfits were seen, even quite nondescript nether garments with Japanese sandals. Japan was quaint, and the rickshas seemed agreeable, though my first ride, alone on a cool wet night when I felt none too sure that the runner would deliver me to the correct address, was not a pleasant experience. We spent a day or two with the Fishers of the Tokyo Y. We were horrified, of course, at Japanese men using the streets as public latrines. At Yokohama there were cordial letters from the Shanghai YMCA people. It seemed wonderfully pleasant to be expected and welcomed in anticipation. Several ladies wrote to me that they would be at the Shanghai jetty to meet us.

We arrived at Shanghai on December 18. There was no way of knowing beforehand that this was to be the day of the Mixed Court riots in Shanghai's International Settlement. These riots were caused by a disagreement about the place of detention for Chinese women prisoners while repairs were being made in the jail. Exception was taken to a decision by one of the foreign assessors [judges] at the court, and this started the trouble. Glass windows in several carriages had been smashed, and a few foreigners had been hustled on the streets. One of the men thus treated was Julean Arnold, then American assessor in the Mixed Court, who had intended to meet us.[1]

We arrived late in the forenoon and were surprised that the jetty was almost deserted. Remembering the letters received in Japan, I wondered a bit that nothing was to be seen of any ladies. Two American YMCA secretaries met us. Will Lockwood began talking to me while Robert E. Lewis asked Bob if I was apt to be nervous—because of the riots, no one knew just what to expect. Bob did not like women with nerves, so I soon heard all there was to tell. The ladies who had planned to meet us had been warned by their husbands to keep off the streets. Of course we agreed to fall in with whatever arrangements our friends were able to make.

[1] Julean Arnold was another Berkeley friend and UC classmate (1902). He joined the U.S. State Department after graduation and was sent to Peking to study Chinese as the American government's first "student interpreter." After this Mixed Court assignment, he moved into economic and trade promotion work and spent most of a long and distinguished career as commercial attaché of the American legation in China. The Mixed Court, with Chinese and foreign judges sitting together, was a device to recognize the dual character of the International Settlement of Shanghai: foreign administration but Chinese sovereignty. It dispensed justice, however, only to Chinese: because of extraterritoriality, foreigners in China were subject only to their own laws and courts.

At this time the Shanghai YMCA was on Peking Road in a three-story brick building. At the jetty we were told that we could not risk sending baggage through the streets. How I wished I had known that when packing aboard ship! Thinking we would have all our things that night, I had been careless of where clothing was put; my chief thought had been to get everything in. However, I did have the baby's food and a few necessities in a basket which I had kept with me. Taking this in Mr. Lewis's closed ricksha, I was hurried off under escort.

When we arrived at the YMCA building, I was shown into a large upper room furnished with an extension table and matching chairs. It seemed to be a room used for board meetings. Mr. Lewis thought we might have to remain here several days. They promised to arrange everything for us as best they could. Poor men! I could see both our new friends were burdened by the unexpected difficulties attending our arrival. Whether there was a fireplace in our room of refuge, I do not recall; it seemed chill and bare. Bob went out of the room with the two men. My first thought was for the baby, and I opened her Japanese koré [a large rattan telescoping hamper] to arrange her little bed in its cover, as we had done on shipboard. Ere I had time to do more than this, in came the three men. Mr. Lewis said that a patrol of bluejackets from an American naval ship had just come down North Szechwan Road and reported it clear. Mr. Lewis still had his private ricksha standing by. He thought we should try to go to the Lyon home, where it had been planned that we would stay. The three men would walk with the ricksha, in which the baby and I would be hidden by its curtains. But we must hurry!

I snatched up the baby and we were off, the koré in front of me in the ricksha. We went straight to the Lyon house on North Szechwan Road. They then occupied a house belonging to the Barchet family, but well north of the Barchet Road corner where the old YMCA double residence was. It was quite by itself on what was then a country road. The Lewis and Brockman families lived in the Y residence, while the Lockwoods were in a terrace of houses belonging to Lord Li, farther out on North Szechwan Road Extension.

It was a little after noon when we arrived at the Lyons'. It seemed chilly in the high-ceilinged rooms. The small fire in the tiny grate of our bedroom made little impression on the atmosphere, but it was the best there was to offer, and the welcome could not have been warmer. What things I lacked for Virginia, Grace Lyon could supply from her own baby's belongings. Her Lawrence was then a year old. (He was killed by bandits in Los Angeles in the autumn of 1934 when a medical student.)

In midafternoon an armed American marine came around with a notification from the consulate advising American citizens, and particularly women and children, to go inside the International Settlement before dark that

night.[2] Willard Lyon was away on Y affairs in Japan; his wife, Grace, was there in that somewhat isolated house with four young children and ourselves—new, green, and with a baby. The house stood in a garden with a brick wall on the Szechwan Road frontage. But a high woven-bamboo fence enclosed the other three sides and would have given no protection against marauders. Grace Lyon immediately hurried a coolie off with a note to ask Mrs. Parker if she could go to her in the Methodist compound, south of Range Road, the Settlement boundary. Will Lockwood agreed to look after us, and it was finally decided that, as the Lockwoods were living in property well known to belong to a Chinese, it would probably be unmolested, while a foreign house, standing alone as did the Lyon place, might be liable to attack by any villagers on mischief bent. The Lockwoods, therefore, planned to remain in their own house that night.

Grace Lyon, hurrying off with her children and some large bedding rolls, naturally did not like leaving her house alone with servants. So it was arranged that Bob would stay with her servants while I would go with the baby to the Lockwoods. In some ways this was a good plan, for there was no bed for us at the Lockwoods'. I could see it was reasonable, but I did hate to be separated from Bob on our first night in China—and under such circumstances. Will Lockwood spent the night, fully dressed I think, in the lower part of the house. I know I shared their double bed with his wife, Mary. We had never met before that day. Both of us were college girls, Kappa Alpha Thetas, she from De Pauw and I from the University of California. We both had babies. Her Edward was fifteen months old, Virginia not far from four months. One baby wakened and cried; this wakened the other. Soon we were up, then down, then up again. I was both cold and nervous. Finally, back in bed at last, trying to get some sleep while wondering what kind of night Bob was having, Mary softly whispered: "Do you know you are trembling so much that you shake the whole bed?" "Yes, I know it and I'm sorry, but I just can't help it," was my answer.

During most of the night Bob was sitting in the Lyon living room with a poker for a weapon. He was startled several times by unaccountable noises,

[2] After the original, rather limited area of the International Settlement filled up by rapid growth, the Shanghai Municipal Council had begun a de facto but unauthorized expansion by building roads out into the surrounding Chinese countryside. The Settlement police assumed the right to patrol these roads (on the basis that they were Council property), but they had no jurisdiction over the large areas between them. In times of disturbance this could present problems for the residents. North Szechwan Road Extended, along which these YMCA houses stood, was one of the new roads into Chinese territory. The Lyon house was about a mile outside the Settlement boundary. Fifteen years later, in 1920, I was a boarder in the Shanghai American School just across the street from what had been the Lyons' house. By that time, all this semi-rural, "outside" area was entirely built up and in all practical ways fully incorporated into the International Settlement. North Szechwan Road was a bustling thoroughfare, with electric trams and reasonably adequate sidewalks.

but of course he did not know what noises to expect in China. Finally, finding that nothing came of them, he lay down on the sofa, covered himself with a rug, and dozed. The night passed safely so far as our neighborhood was concerned. The next night I again stayed with Mary Lockwood while Bob, armed with a revolver from the consulate, was a member of the foreign citizen patrol for this part of Hongkew where the Y folks lived. This is the only night in China that he was on armed guard, and there was no need for him to use his weapon. After these two days, the disturbances calmed down, and apprehension of trouble from lawless or ignorant Chinese ended.

We moved back to the Lyon house and within a few days obtained our luggage from the ship. Even after all seemed peaceful and quiet, I was bothered at night by a peculiar sharp rattle that we would hear at intervals through the night. Bob had no idea what it could be. From Grace Lyon we learned it was the watchman in a village across the fields to the west. In the Chinese way, he beat a certain cadence on a piece of bamboo to let householders know he was alert on his job and to notify marauders of his whereabouts!

After we got our luggage from the ship the baby had her carriage, and we acquired an amah for her. She was the wife of a coolie at the Brockman home. The amah was pleasant and the baby liked her at once. Of course, I could not talk to her but soon learned a few nouns and verbs—"hot water," "come," "not want"—and we got on. Christmas came and went. Willard Lyon was home by this time, and we had a pleasant, jolly celebration with new friends who made us feel entirely at home. There was a tree and a cobweb hunt for the children, and a few guests on Christmas afternoon.

Shanghai made very little impression on me at first. There were no high buildings in 1905. China looked drab, cold, and wet. The river [the Whangpoo] was not inspiring, and the land we saw scarcely more so. I do not recall any features that made the city attractive or unique. The streets were narrow and horse carriages abounded, each with its two uniformed men on the box. The driver wielded reins and whip, and his assistant the bell. Sidewalks were narrow and on some streets entirely lacking, so that I was often afraid of having my shoulder or hat nipped by a horse as I threaded my way along between foot traffic of the most motley variety.

We were bidden to tea by Dr. Hawks-Pott, then chairman of the National Committee of the YMCA in China. It was a long journey through the city by carriage to his home at St. John's University. Houses on Bubbling Well Road around where it meets Chengtu Road were then well out in the country. North of Range Road lay fields, save along North Szechwan Road where Chinese white-plastered tenements of the old style swarmed with inhabitants.

We attended Union Church; aside from it I do not recall that we entered a single public building of interest. We went to the American consulate and all

I remember of it is that the river nearby seemed very dirty and noisy. I attended a meeting of the American Women's Club there in the parlors of the consul general's wife. The club was a small circle of women, reading papers and doing the things usual to such groups in America.

As time went on we heard a good many rumors of possible trouble. New Year's Day, we were told, was to be a bad time for all foreigners. After that passed safely, Chinese New Year's Day, late in January, was to be a day of poisonings carried out by servants against their foreign employers. Through all this we went on with our plans to go west as soon as possible. For one thing, our salary would not commence until we reached our final destination; private funds, outfit allowances, and expense money could not last for ever. We were eager, too, to reach our new home and get to work on the language.

We had thought to travel with a bride and groom, both of whom had been in China previously and who expected to return from home leave at this time. They were Canadians, and the bride was well known for her medical work in Szechwan. But their group was delayed for some reason. We then decided to travel with Mr. J. W. Davey of the Christian Literature Society. He had been to the Coast to buy supplies and was returning alone to Szechwan. I was busy those days making warm short clothes for the baby, using white Japanese flannel, like albatross or heavy nun's veiling.

4

The Houseboat

(1906)

Despite rumors of evil, we left Shanghai for Hankow on the river steamer Kinling at midnight on January 17, 1906. Friends saw us off and presented us with many comforts and remembrances. We had many loving messages, and our hearts were firmly bound to the Y friends who had helped us in Shanghai.

Among our fellow passengers was a newly married English couple. She had just come out from England, while the groom came down from Szechwan to meet and wed her in Shanghai. Naturally, her luggage was still marked with her maiden name. The very proper Number One Boy of the ship failed to see why the baggage of Miss L should be placed in the cabin of Mr. S. The bride's panic over her lost trousseau, and the groom's distress as to its whereabouts, soon became apparent. After explanations to the Number One, happiness was restored, and the blushes of the bridal pair provided a pleasant interlude. We all, with the ship's officers, tried to give them a start on a happy honeymoon.

In Hankow we stayed with the Clintons, who were Y friends. Mildred Clinton's amah gave Virginia a pair of little red satin "tiger shoes," with the head, ears, eyes, and mouth, and even silk-thread whiskers, wrought on their toes. Bob and I were more delighted with them than the baby was, though she did take notice. On Chinese New Year's Day we boarded the old Kiang Wo for Ichang and the way west.

Pearl Buck has written of the Yangtze River steamers: "Their polyglot crews were headed by blasphemous, roaring, red-faced old English captains who had rampaged along the Chinese coasts for years and had retired into the comparative safety of the river trade. Not one of those captains but was full of tales of the pirates of Bias Bay and of bandits along the shores of the river, and they all had one love and one hate. They loved Scotch whisky and

hated all missionaries." We saw some of this type but more often found appreciative and friendly hearts under the blue uniforms of the ship's service. Bob was a keen and enthusiastic player of games for sport's sake, and he was tolerant and kindly. He usually made his way to friendship with all he met as companions on journeys.

In command of the Kiang Wo was Captain Mutters, an "old China hand." He was said to be gruff and could talk violently if occasion demanded, but he also had a soft heart. After boarding his ship, I was sitting in the small saloon holding the baby while Bob attended to getting the baggage aboard. The captain saw me there. "Young woman, where are you going?" "Ichang, and then on to Chengtu." I told him. "Where's the young man who is undertaking this?" asked he. Later the captain won my heart by telling me that our baby "did very well." From him, this meant a good deal.

The river was falling rapidly, and we had to tie up almost every night between Hankow and Ichang. Bob played many games of chess with the officers and others, but the time passed slowly. Once we were hailed to help a stranded steamer off a sandbank. We put out a hawser, and the steam winch was set to work. They yelled to us that their ship was "coming all the time." Suddenly our position shifted, and we could plainly see men standing not more than knee-deep in the water on the other side of their stationary craft. Captain Mutters let out a string of the most virulent profanity and ordered the hawser cast off. We proceeded on our way, leaving the other ship for better luck with some other helper, or to settle on their sandbank for a few months of inactivity. A falling river augured well, we were told, for houseboat travel on the river above Ichang. On the last day of January we were in Ichang.

In Shanghai we had provided ourselves with Chinese pugai [thick cotton-wadded quilts, like comforters] and blankets. These were for houseboat travel on the upper river. We found, when we reached there, that these would also be needed at the China Inland Mission Home in Ichang. This guesthouse was efficiently and economically run; everything was clean and the food ample; but there was little to soften the austerities. In our bedroom we found a woven cane frame for a double bed set up on two long benches (bandeng ). There was a small table for a lamp, and an unpainted wooden shelf for a washstand. It held a white enamel basin and water pitcher and a drinking-water bottle and glass. A pail below was for waste water. There were two straight cane-seated chairs. No heating arrangements were provided, and the February weather was raw.

Years later a young friend told with laughter of her first impression of her bedroom in this same Home. Her mission office had failed to inform her that she would need her own bedding in Ichang. So she felt particularly forlorn

when she was ushered into a cold, whitewashed room on a bleak winter day to see only a hard, bare, cane bed-frame standing on ."horses." Then she raised her eyes to the motto above to see "The Lord Will Provide."[1]

In spite of meager amenities, we were soon at home in our room and stayed there quite comfortably for seventeen days. Bob unpacked our portable kerosene heater, and I begged a low chair. Our hostess, Mrs. Row, saw my predicament: it was hard to bathe the baby from a high, stiff chair or from a suitcase dragged from under the bed. She kindly provided me with a low rattan chair. We bought our own kerosene, so could have its heat whenever we wished. Later, I found we were considered very extravagant "in an American way"; but we thought a baby needed warmth, and we sought a bit of comfort ourselves. Virginia was very good those days, playing with her rattle and becoming dearer and sweeter to us all the time.

We were delayed in Ichang because some of the paper and printing supplies in Mr. Davey's charge had failed to be loaded on our steamer when we left Hankow. We had to await their arrival before setting off on the houseboat trip. During this time we were the only American guests at the Home. Several British newcomers for both the China Inland Mission and the Church Missionary Society were there, and a number of them became our very good friends. Some were our own age, and among these at least two incipient courtships had begun. Bishop and Mrs. Cassels were also there. We greatly enjoyed meeting all these people whose lives and environments had been so different from our own. At table I was seated by the bishop and chattered happily away to him in my "carefree American fashion," never dreaming that one should be suitably reserved with gentlemen of such position and cloth. One of the elder single missionary ladies told me years later of how they marveled to see me "talking to the dear bishop just as I did to anyone else."

The interest of this stay in Ichang was enhanced for our newly arrived British friends by the necessity of changing into Chinese garb. A few, such as our groom of the lower river, had already made the change. In Ichang, however, the men all came out in new Chinese clothing. At that time this was thought to be more suitable for the climate, easier to obtain, and—perhaps most important—less conspicuous. It was picturesque but seemed awkward to me, and I was very thankful that we did not have to follow this rule. Especially did it seem peculiar and inconvenient for foreign men to be burdened

[1] There were no foreign-style hotels beyond the coastal treaty port cities. Inland, one had the alternatives of medieval Chinese inns or the hospitality of local missionaries. But the missionary population and missionary travel were expanding rapidly. At focal points such as Ichang the volume of transient travel had outgrown the capacity of local hospitality. So a hostel (or "Home") was established, usually by the mission most active in the area. For Grace and Bob's introduction to these hostels, it happened that the operating agency in Ichang, the China Inland Mission, was perhaps the most austere and "hair-shirty" of the Protestant missions.

by wearing the queue. In Shanghai I had seen one such man with a long blonde braid, and the impression was decidedly unpleasant. The men had been foregoing haircuts for some time and looked forward, no doubt with mixed feelings, to the time when they could boast long dangling braids. The Chinese, to cover any hirsute deficiencies, were exceedingly adept in adding black silk threads to augment the thickness and length of their prized queues. With such skillful aids, even hair of shoulder-length could be made quite presentable.

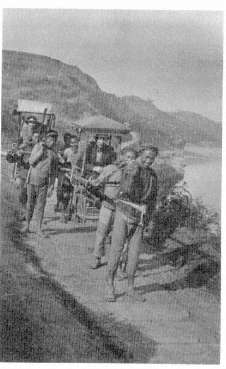

Early in February a large party of British young people left by houseboat for Wanhsien. I recall that I had my first ride in a sedan chair when we went down to the river to see them aboard. It was the custom for houseboat travelers to go aboard and get settled and then make the start after daybreak the next morning. This party had two boats: one for the men and most of the freight, the other for the chaperons and the single ladies.

Ichang was a most unattractive city, low-lying, dirty, and seemingly full of vile and odorous black mud.[2] The pyramid-like hills across the river looked clean and pleasant, but the weather was gloomy and raw and did not make us feel like excursions. Just to look down one of those dingy, foul-smeling streets was enough for me. I wondered then, with a new concern, what Chengtu could possibly be like. Bishop Cassels assured me that it had wide streets well paved with stone slabs. Even doubts of the future did not tempt us to turn back. We felt committed to our new life. I sometimes think back to those Ichang days, a little happy time with our baby before the days of our great testing.

Mr. Davey's cargo arrived, and he now began strenuous efforts to hire suitable boats for our journey to Chungking. He had a considerable bulk of cargo, and we had no small amount of our own. It was decided that three boats were needed.

The first was what the Chinese call a kuazi . This was a four-room houseboat, about eighty feet long and fifteen feet wide. These boats had trim lines and a lean, shipshape look. The long hull, all curves and with a solid grace, was built of heavy timbers and stiffened by a compartmented hold. The draft was perhaps three-and-a-half feet and the deck about four feet above the water, so the space under the flooring was considerable. Sockets in the compartment bulkheads held slats which supported removable floor sections. The material of construction was pine [and cypress] of several kinds, but all · were included by the Chinese in the all-embracing name baimu . Some of this

[2] Today the city of Ichang is a vastly different place. It is the site of a mighty dam across the Yangtze, from which electrical power flows through 500,000-volt transmission lines as far as Shanghai. And through locks in the dam there is a steady flow of modern, machine-powered vessels. A wonderful source of information about the great river and the cities along it is Lyman P. Van Slyke, Yangtze: Nature, History, and the River (Stanford: Stanford Alumni Association, 1988).

7

Grace's sketch plan of the houseboat.

A—open deck for crew, roofed at night by straw mats which were in daylight pushed back over our permanently roofed portion

B—cockpit, where the food for the crew was prepared

C—mast, the wooden partition behind this was made of hinged door-like sections D—living and dining room

E—Mr. Davey's room

F—our cabin

G—kitchen

H—Captain's bridge, a heavy plank raised about four feet above the deck and extending across the boat

I—open deck

J—Captain's cabin

K—passage

wood is knotty and full of pitch; other kinds make better boards. The boats were not painted; an overall finish with wood (tung ) oil gave them the fresh, attractive appearance of natural wood. They were stout craft, well adapted for the perils and strong surges of the great river they served. But nowadays they are seldom seen.[3]

Just aft of the foredeck were the living quarters reserved for our use [see fig. 7]. These took up about thirty feet of the ship's length. Partitions fitted in grooves could be changed to suit the wishes of those chartering the boat. Our own rooms are D, E, F, and K on the sketch. The space marked G was for our cook. Our trunks and valuable possessions were in the hold compartments under our feet; they would be safe, and accessible if needed. There was an inside passage, but the crew were required to go over the roof when passing from front to rear—which, in practice, they seldom did. However, when passing through rapids and difficult stretches, the whole boat had to be open from front to back so the captain and pilot could see through. On each side of the boat there were three tiny glass-parted windows with sliding wooden

[3] Kua in the name of this type of boat means "to stride, bestraddle." The name seems apt in giving a sense of power or aggressiveness. They had the high stern but otherwise were very different from the more familiar cockleshell Chinese coastal junk. Low in the water, with a long, flat foredeck, they had something of the efficient, purposeful look of a modern tanker. That they were seldom seen when Grace wrote in 1937 was an indication of the extent to which they had already been replaced in long-distance freight and passenger transport by modern ships, first steam and then diesel. The Yangtze traveler of today still sees native junks engaged in local traffic; but they are a far cry from the majestic craft of Grace's account.

shutters. Inside our flimsy wooden partitions we hung dark-blue "coolie cloth," the cheapest kind of native cotton material, to foil any prying eyes. The floor was oiled and well finished, and the whole interior neat and attractive.

The other two boats were smaller cargo craft without passenger accommodations. They were loaded high under their roofs with bales of paper, cases, and packages 'containing a great variety of things. Mr. Davey was taking goods for many friends in Szechwan as well as for himself and his work. Shanghai friends had urged us to buy some furniture there. We had iron beds, springs, and mattresses from America. To these we added a large English bureau, a "double" washstand, and a massive teak sideboard, all purchased at a Shanghai auction. We had also acquired a dozen dining room chairs. Mr. Davey had been a bit dismayed to hear of the three larger pieces, but seemed to think the chairs were a better buy. However, when he saw them he was anything but pleased. He assumed we had bought the common bentwood, or Vienna, type of chairs. These were much used on the China coast, perhaps because they could be imported from Europe knocked down and took little shipping space.

It happened that we had been fascinated by some wooden, cane-seated chairs of Chinese make and known as Ningpo chairs. Not only were they rigid and impossible to knock down, they could also in no way be nested. They proved a very bulky possession, but also a joy for many years. Every time we saw bentwood during our early years, we remembered the loading of those Ningpo chairs at Ichang and laughed.

At last all the things were loaded onto the three boats, which were to proceed up river under man power. Trackers were to haul them by long plaited-bamboo ropes, whose constant rubbing across rocks on many points of the shore had worn deep grooves in the limestone. A certain complement of trackers went with each boat; the captain [usually the owner] hired more to assist at rapids and places of peril or difficulty. This crew of trackers slept and ate in the front of the craft; the captain and his family and the pilot lived in the rear. Our rooms were clean and bare. In them we placed our own cots, baggage needed on the journey, and two or three locally made bamboo chairs—bought for a few cents. Dining table and chairs of the usual straight-backed Chinese style were supplied by the boat.

Mr. Davey's boy had gathered together some cooking gear, a charcoal brazier, and a tin oven.[4] Mr. Davey courteously inquired our preferences when laying in food for the journey. Being British, he was especially solicitous as to what kind of meat we liked. We told him we were not fussy; but I added that

[4] This oven would have been made from the ubiquitous square kerosene tin. These tins were designed to transport "oil for the lamps of China," but they found a myriad other uses, some of them rather surprising.

Bob did not care for mutton. What he told his boy I do not know, or what the latter could buy; but he did get half of an old goat and there it was, hanging by the door of the kitchen when we went aboard. I can remember nothing now save boiled potatoes and strong-tasting mutton stew with chestnuts. The bread was also poor, but the cook had few resources and no conveniences.

5

Tragedy on the River

(1906)

We went on board our houseboat on February 16. The next morning, amid a great din of the crew, a cock was killed and held so that its blood ran down on the prow of the boat. Then, as soon as it was light enough to see, the boat cast off and we headed into the Ichang Gorge, just above the city.

Soon we fell into a regular boat routine, tending the baby, looking at the scenery, writing letters, and continually marveling at the handling of the boat, the vistas of the river, and the daily life of our Chinese companions.[1] The gorges of the Yangtze are magnificent; in a houseboat we found them much more impressive than on later steamer trips. A houseboat going up the river moves very slowly. One is so near the water that one senses vividly the power and sweep of the current. There is a greater distance to look up at the cliffs, and more time to note their varying shapes as one slowly changes position. A small boat may take hours to round a turn in the cliffs where for a long time there seemed to be no opening for the river. On a steamer this corner may be behind one in half an hour; its passing does not seem the achievement that it does under man power with the long lines of trackers pitting every ounce of their strength against the relentless force of the stream.

The river has carved its way through canyons of beauty and wonder. In some places there are no paths for the trackers, and they sit on the foredeck, whistling in an eerie way for the prevalent up-river wind to help their craft along. Or they row feverishly to gain on the current as their yells and cries resound from cliff tops lost in clouds. A strange hush often lies over the oily-looking water in places where no sounding has ever recorded its depth.

[1] John Hersey's A Single Pebble (New York: Knopf, 1956) is a wonderfully vivid description of junk travel through the Yangtze Gorges and the life of the men whose humble strength pulled the boats upstream. Hersey is China-born: his father was also a YMCA secretary and, coincidentally, arrived in China with his young bride in the same year as Bob and Grace.

When we had almost reached the west end of the Gorges, a week out of Ichang, Virginia became ill. Steadily she grew worse. We had been giving her a standard brand of baby food, on which she seemed to thrive. I had not been able to nurse her since shortly after our arrival in Shanghai, where the unusual excitement of our first few days stopped the milk supply. Every day we took pains to clean the baby's bottles and prepare her things. All our drinking water had to come from the river; of necessity its preparation, aside from boiling, could not be as carefully done as one might wish. We lacked many facilities and could only do as all such travelers do: be as careful as circumstances permitted. We always used boiled water and boiled the baby's utensils. When she began to be ailing we changed her diet as best we could with the various infant foods we had with us. But nothing arrested her illness.

We now had most of the rapids to negotiate. Between Ichang and Chungking, the Yangtze has thirteen large and seventy-two smaller rapids. "Where hard limestone layers cross the river, and in other localities where torrential tributaries have built great alluvial fans, the valley bottom is no wider than the stream itself. At such places there are dangerous rapids."[2] At various times there have been attempts to reduce these dangers by blasting out rocks obstructing the channel; now, in 1937, the Nanking government has recently made another attempt to do this for the safety of navigation. It still presents many difficulties, perpetually changing as each rise or fall of the river produces different currents and whirlpools, all with varying hazards of rock and channel. The very sight of the worn and eroded rocks, laid bare when the river is low, makes one realize the stern task of the boat with nothing but human strength to pit against the force of the stream. Now steam is used, but in 1906 primitive methods prevailed on the Big River.[3]

We had expected to reach Chungking in about twenty-five days from Ichang. One boat with extra trackers had been known to do this trip at the same time of year in nineteen days, but we had three boats and it would take us longer. It is not easy to keep several craft together on such a journey. Apart from the varying ideas of each boat's captain, there is also the fact that at each rapid, boats take turns in passage up. A very small misadventure could make a boat lose its turn, and should such position be lost there might

[2] George B. Cressey, China's Geographic Foundations (New York and London: McGraw-Hill, 1934).

[3] . China's new government has been able to do much more in clearing obstructions. Even more important has been a complete marking of the channel, mostly with lights on precisely anchored little rafts—whose positions must continually be checked and altered with the rise and fall of the river. Now the ships no longer tie up from dusk to dawn: powerful searchlights grope and mark each shore for the pilot. Today's traveler thus loses not only much of the old excitement of the rapids but also a chance to see some of the scenery. The final diminishment will come if the Chinese government builds a proposed high dam that will drown the rapids and make the river into a lake almost as far as Chungking.

be considerable delay. There were no doctors at any ports of call; foreigners were to be found at only one port, Wanhsien.

During the time of the baby's illness we were traversing that section of the river where the worst rapids occur. At many of these rapids, travelers went ashore and walked around the perilous places, carrying a few precious possessions with them. Now one can hardly imagine the scenes of those days at these danger spots: the roar and surge of the wild waters, often rising in huge waves at the crest of the rock barrier; the yells of the gang bosses, stimulating the trackers to greater efforts with voice and whip; the long lines of tracking men, fairly lying on the ground as they bent far forward and clutched rocks and earth to aid them; the ropes of such immense length that often the trackers were out of sight around rocky points, ropes laid out in ways found most efficient by the long-experienced local pilots hired by the captains to take command at these critical places; the signals of the drummers to trackers far ahead; the sight of the great boats as they came up to their crucial trial in surmounting the rise of water in front of them. The pilots were clever at taking advantage of every little eddy or back current, but to the spectator on his first voyage, who saw the boat containing all his worldly goods hanging on the crest of a treacherous wave as the fury of the river pounded against its wooden shell, the scene held more drama than one liked.

We were fortunate at the rapids, for I dread to think what might have taken place had we lost our houseboat at one of them. Such things have happened. If we had had to camp on the shore with what we could salvage from a wreck, it might have been still harder; or if we had been on the boat when it was swept down stream after the breaking of tow-ropes, the situation might have been worse. Only once did such a rope give way, and the danger was short-lived and did not result in disaster. Even now, all my memories of anxiety at Virginia's illness are forever blended with the sounds of rushing water, of the hiss of the crisp surge against the thin wooden side of our boat, of looking out when caring for the sick child and seeing into the heart of a whirlpool, of rocks half-disclosing their jagged points near the side of our craft, of a feeling of man's utter impotence and the irresistible power of wild water.

Perhaps it was just as well for us that we had no time to spend in worry for our safety during this time. We thought only of our baby and of caring for her. When the men burnt incense, laid out new ropes with much care and ceremony, undergirded the ship with heavy bamboo cables to give added strength to the hull, we gave these details but scant attention. As the boat crept up the rapids we put our valuables in safe places and waited to stir about until we were in calmer water. We lost fear for ourselves in our care for the precious baby.

Only once did we go ashore at a rapid and that was at the Yeh Tan (Wild

Rapid) where the captain of our boat asked us to do so. The baby was fretful there and looked pinched and ill in her basket as we carried her with us along the bank. We had hurried to Wanhsien, hoping to find there a new doctor for the American Methodist Mission in Szechwan. But he had left with China Inland Mission folks of Yunnan to help them with a sick child.

It is impossible to write much of those days of anxiety and anguish. Those who have lived in isolated places in our homelands well know the feelings of helplessness that come to parents. We knew these and more. The whole life purpose that had brought us on this journey was tested in our hearts as the days passed. We questioned ourselves over and over as to what we had done, or omitted to do, in our care of the baby. Mr. Davey had several children, but he had not been through such a crisis. He did all he could for us. When we found no doctor in Wanhsien, one of our British friends from the Ichang stay heard of our distress and came to the boat just before we started off. He wrung our hands with sympathy and offered a prayer for our little daughter. Now time was doubly precious. We made all haste to Chungking, engaging extra trackers and pushing on as fast as was humanly possible.

Still, our Virginia was never to see that city. On March 4, a Sunday evening, we knew the child lay dying. Suddenly it came over me that I would soon be in the presence of Death, whom at this time I had never met. I do not remember what or when I had eaten that day, but I was afraid that evening that I would faint or be ill and so would not be able to do the necessary things for my baby. I asked Mr. Davey to have the Boy make some cocoa, and when it came I drank it so hastily that I scalded my mouth badly.

Virginia died at eight in the evening. I washed and dressed her and we put her in her basket with lighted candles close by. Bob and I, exhausted by our strenuous week of nursing and anxiety, slept fitfully with tears on our faces. That night we were anchored below Fengtu, near a tall pagoda on the top of a high hill. The next day the boat captain went by land across a loop in the river and bought a little coffin for us at Fengtu town. I prepared the coffin, using one of the pretty "puffs" given Virginia for its lining. Mr. Davey insisted upon putting her in the coffin. A workman who came to the boat with the coffin then sealed the lid down with a lime preparation in the Chinese manner. We kept the coffin in our room the rest of the trip to Chungking.[4]

[4] Emotions, for both Grace and Bob, were controlled. There was not much talk of Virginia in our family. But Grace always reminded us quietly on August 26 that "this would have been your sister's birthday." And on trips up or down the river, we boys knew the significance of the "tall pagoda on a high hill" at Fengtu. When Caroline and I made our first return trip up the river in 1975, I found myself looking for it: it is still there, lonely and unchanged.

Grace says, "There were no doctors." There were, however, Chinese practitioners of traditional medicine: unsanitary, unscientific, but with a centuries-long experience of healing, and a knowledge of herbal remedies well proven for many diseases. I am sure that neither Grace, as

long as she lived, nor any of her missionary colleagues and contemporaries, would think it strange, or in any way worthy of note, that they never thought of these Chinese "doctors."

I suggest that neither school of healers, the unused Chinese or the unavailable Western, would have been of much help medically. Virginia had "bowel trouble," probably diarrhea or some form of dysentery. She was sick for about ten days: most likely it was dehydration and the loss of body salts that brought death. In 1906 there were no doctors who understood these factors and their quick and relatively simple remedy.

6

Illness in Chungking

(1906)

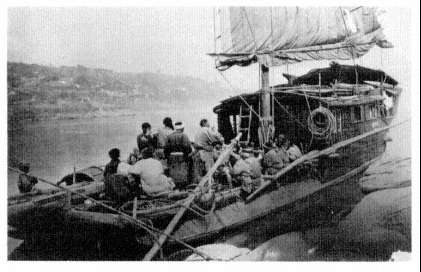

Mr. Davey had been very helpful to us all through these hard days. Now he urged us to get out of the boat: to walk, take photographs, fill our minds with other things. We did go ashore several times the day after Virginia's death. Cloudy and drizzly weather in the Gorges had prevented photography, but we took good pictures of the houseboat on this bright Monday.

That night as we were going to bed I happened to feel Bob's hand. It was terribly hot as it rested on the side of the bed. I told him he must have fever and he reluctantly agreed. Next morning Mr. Davey looked grave. We decided to give Bob nothing but light food, mostly condensed milk and crackers. Before we reached Chungking the crackers were exhausted and the milk was getting very low.

At first we gave him quinine, but Mr. Davey was sure it was typhoid. If so, quinine would not be good; so we stopped that. Then we gave almost no medicine but kept the patient quiet in bed. Neither Bob nor I had ever had a fever, nor had we seen anyone with a severe fever, so we knew nothing about treatment for such illnesses.

By this time Mr. Davey had seen the imperative need for reaching Chungking speedily. Still more trackers were hired, until they overcrowded the boat and slept even on its roof. We did everything humanly possible to hasten our journey. I lived in a daze. My husband, always so strong and athletic, lay ill on the bed; our baby in her coffin lay in the same little room. I cannot now recall that I ever felt Bob might be ill unto death; but I did wonder how one could live on day after day in this strange situation still carrying on the usual daily routine. To start this journey in health and high hopes was easy; to continue it to the end proved to be another thing. But there was nothing else to do; we could not turn back.

8

"We took good pictures of the houseboat on this bright Monday"

(the day after Virginia's death).

On the twenty-first day from Ichang we arrived in Chungking. The day before we expected to arrive, I asked Mr. Davey if it would be possible to send a messenger ahead. He said this could be done; we could get a man from a river-bank village to carry a letter. Mr. and Mrs. Warburton Davidson of the English Friends' Mission had written and invited us to stay in their home while we were in Chungking. However, I did not wish to take Bob there if he had typhoid. This would be too much to ask of strangers who were taking us in only because they had heard of us through Dr. Hodgkin. Also, I knew there was a doctor in the American Methodist Mission in Chungking. Mr. Davey told me this doctor, J. H. McCartney, had a hospital.

I wrote a letter to Mr. Davidson, who had not heard from us since we left Ichang. In this I told him of Virginia's death and of Bob's illness, suggesting that he reserve a room for my husband in the hospital and asking him also if he could have a grave dug and arrangements made for the baby's funeral. Mr. Davey had told me that a foreign cemetery lay outside Chungking. He also said that it was impossible to take a coffin containing a body inside any walled Chinese town, so immediate burial was what we must expect. The runner carrying this letter set off about noon on March 9. He reached Chungking that night after the city gates were locked, but he followed our instructions and had himself pulled up over the wall by ropes. He found the Davidson compound and handed in the message about eleven o'clock. It happened that the Davidsons had just returned from some social affair at the McCartneys'. It was an unusual occasion to be so late, a wedding anniversary

or something similar. Mr. Davidson got back on his horse and immediately returned to see the doctor and show him my letter. They planned for the morrow and then separated for a few hours sleep.

On the morning of March 10 I was combing my long hair when I looked out of the tiny houseboat window and was surprised to see a sampan [a small rowboat] containing what looked like two foreign men. I grabbed up my glasses and saw they really were foreigners. They were, to my great relief, Dr. McCartney and Mr. Davidson. As we had been moving slowly upstream since earliest dawn, they had come swiftly downstream.

Dr. McCartney examined Bob at once and said that he did not have typhoid; his diagnosis was that it was probably malaria.[1] Mrs. McCartney had risen early that morning to have two rooms at the hospital prepared for us: one for Bob and an adjoining one for me so that I could be near him. Mr. Davidson, however, was urgent in his invitation for us to go to his home where his wife was expecting us. After such hard experiences and so much isolation, I longed for the warmth of a home. Also, our food and care would be a considerable burden for the McCartneys, as the hospital was set up for Chinese only and no provision was made for the needs of foreigners. Our food, for instance, would have to come from the McCartney kitchen. We were deeply grateful but decided to go the Davidsons'. A case of malaria in the home was not the same as a case of typhoid. Bob was helped to dress, and before noon we were in the Davidson home inside Chungking city.

After tiffin I went with Mrs. Davidson to an empty residence owned by their mission.[2] This stood outside the city walls, and Warburton had our little coffin brought here. We covered the casket with some black cloth and pinned large sprays of the most beautiful magnolias on its top. The casket had been rough and the varnish hastily applied; with the cloth and the flowers it looked less bleak. Mr. Davey was unavoidably occupied with the many affairs of our arrival and unloading, made more onerous for him by Bob's inability to help, and he was unable to attend the funeral services. These consisted simply of a scripture reading and short prayer at the grave side that afternoon in the small foreign cemetery on a hill near the Tsengkiayai Methodist boarding schools.[3]

[1] Bob never succeeded in getting the malaria completely out of his system. He had recurring attacks every year or two (or so it seems in my memory). Often he managed to keep on his feet; I don't remember his ever going to a hospital, even when the fever was enough to make him delirious.

[2] "Tiffin" is the Far Eastern word for the midday meal, luncheon. Grace and her teetotaler missionary friends may not have realized that it comes from an Anglo-Indian word for drinking.

[3] When these events took place, in 1906, the American Methodist school compound and the nearby foreign cemetery were out in open country amid terraced rice fields and low, grave-covered hills, perhaps a mile beyond the city wall. Tsengkiayai (Tseng Family Cliff) was the name for the general area. In 1938 the Chinese government, driven out of Nanking and then Hankow, moved its capital to Chungking. Government departments, thousands of bureaucrats,

and hundreds of thousands of refugees had to be accommodated. Tsengkiayai was the only direction the river-girt city could grow. By 1941, when I was assigned to the embassy in Chungking, the mission compound and foreign cemetery were little green islands lost in a maze of helter-skelter, flimsy, wartime construction. Not far south of the compound, and separated from the cemetery only by a brick wall, were the headquarters and one of the residences of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. As could be expected, this became a favorite Japanese bombing target. The stone on Virginia's grave (to which Bob's ashes had been added by Grace in 1936) had been chipped and knocked askew by a Japanese near miss.

Being Methodists, as well as neighbors, the Generalissimo and his glamorous wife gave the mission great face by sometimes attending Sunday services at the school chapel. But the name Tsengkiayai is universally known in China today for a very different reason. Only a hundred yards or so to the north of the mission compound gate were the rented premises, down a narrow, crooked alley, which were the wartime office and residence of Chou En-lai and the Chinese Communist Party's delegation to the Nationalist Government.

When I returned to Chungking in 1971, the city had continued to grow, and the little foreign cemetery had disappeared.

A few missionaries who had heard the news of our arrival were present to show their sympathy and concern. As the coffin was lowered by ropes into the grave, it did not lie straight. Dr. Freeman, whom we had tried to overtake in Wanhsien and who had arrived in Chungking a few days earlier, jumped down into the grave and straightened it. I had felt a terrible numbness for days since my first violent weeping and the beginning of Bob's illness. How could I constantly weep when he lay sick and my thought had to be for his welfare! But that friendly act by Dr. Freeman started my tears. I turned away from the grave as if looking for a friend, and one of the women stepped forward to comfort me.

The truth was that I had never before that day seen any of the people at that little service. It was a hard situation, but these new friends did all they could to soften it. I had little courage, but my endurance was sufficient for the day. Mrs. Myers made us take a cup of tea at her nearby home, and this gave me a chance to meet those who had stood by me at the grave. Their kindness brought them close to me that day. It is in these ways that people in foreign lands, isolated from their own blood, become welded together in ties of everlasting friendship.

But I was anxious to return to Bob, who had been sitting fully dressed by the fireplace in the Davidson home inside the city. He could not attend the laying away of his precious daughter; neither could he settle down in bed until it was done. When I came back and told him all was accomplished, he was content to be carried up to his room and get into bed to begin the struggle against his fever. Dr. McCartney was devoted in his attention. But the fever had taken strong hold in those days of untreated illness on the river and was slow to yield. We were obliged, accordingly, to spend some weeks in Chungking. During this sojourn Hetty and Warburton (we soon dropped formality) were like brother and sister to us. We will never forget their kindness.

Much later, we could laugh over some of the happenings. Trying to vary Bob's monotonous liquid diet, Hetty asked the doctor if he could take potato soup. The doctor inquired what it would contain and was told: milk, potato, and some onion. "All right," was the reply, "but no onion and no potato." As Bob had trouble sleeping, the doctor gave me a "sleeping mixture," telling me to give him a teaspoonful every night. I did and Bob slept like a log. One night a terrible fire broke out close to the Davidson compound. Flames lit the sky and showed red on our whitewashed bedroom walls. I was alarmed and talked to Warburton about possible danger. Their house was protected by a high brick wall, but other unprotected neighbors were in a wild state of terror. We could hear them yelling and dragging boxes in search of safety. Chungking is noted for these terrifying conflagrations.

Warburton suggested that I go with them to a platform on their roof to get a better view. Before going I tried to arouse Bob in case he might waken, see the fire, and be alarmed by my absence. But Bob lay like a dead man; try as I might, I could not wake him. Finally, I went aloft and let him sleep. The next morning I recounted this to the doctor. He asked how much of the sleeping medicine I had given. I showed him the spoon. "Goodness," said he, "no wonder he slept! I thought you would use a British teaspoon, which is a good deal smaller than this." My mother, years before, had given me a silver teaspoon for medicine and I had used it. After this Bob got smaller doses.

In April the weather grew hotter, and still Bob lay ill. One day the doctor assured me the fever was broken and our patient would soon be up. The next day his temperature reached a new high! Even the doctor was puzzled. We had to possess our hearts in patience and let time work in its own way.

In Shanghai we had been given Chinese names by Dr. Lyon in consultation with Chinese. In Szechwan the pronunciation differed so that the surname given us had the same sound as the word for "kill" (sha ). Chungking friends said this would never do. We then asked them to pick a more suitable name. Our only stipulation was that it should not be the same as the Chinese name of Dr. and Mrs. C. W. Service of the Canadian Methodist Mission. Hsieh (gratitude) was chosen for us and we always liked it. Bob's given name was An-tao, which meant "peaceful way." Years later, Chinese friends in Chengtu picked a name for me: Yun-tao. This went well with his, and the same characters had been used by a noted woman writer of long ago whose full name was Hsieh Tao-yun. We later learned that the other Services had the same surname; actually, though we lived for years in the same city, there seemed to be little trouble caused by the name identity in both English and Chinese.

During this time in Chungking I was busy caring for Bob and writing the difficult letters home telling of Virginia's last days. It was good for me to keep occupied, and I tried to be as cheerful as possible for Bob's sake. The doctor

wanted me to get out, so nearly every afternoon Warburton had trusty Chair-bearers carry me through the only land gate of the city into the countryside. All the other gates opened toward the Yangtze or Kialing rivers. After a short excursion I would be brought home again. One day the men carried me into a dense crowd and finally set the chair down. It was a closed, or curtained, chair. I was soon glad for this protection when the bearers seemed to disappear and crowds pressed all too closely around me. When I told Warburton about this, he questioned the bearers and found they had set me down so they might better witness the execution of some criminals. We had stopped at the execution grounds.