Chapter Four

Authors, Akharas , and Texts

Although the textual evidence is scanty for much of the dramatic literature predating Nautanki, plays of the Svang and Nautanki traditions have been published in chapbook editions since the arrival of the printing press in northern India. Beginning in the 1860s, dozens of popular publishers have engaged in disseminating Nautanki booklets; the repertoire of stories now numbers over four hundred. These folk plays have been fortuitously preserved against the hazards of time, despite their fragile form and lowly status. By an act of Parliament in 1867, printed playscripts dating to 1866 were collected and sent to the India Office Library and the British Museum in London. Cheaply produced contemporary versions can still be purchased on the street in certain markets in India. The dramatic literature of Svang and Nautanki is a unique resource in its large size, chronological span, and link with a surviving performance practice. Its texts afford an exceptional opportunity to study a single folk genre in rich detail.

Insofar as this literature has never been fully documented, this chapter first specifies the location of contemporary and historical textual resources and then chronicles the sequence of poets, plays, and themes and their changes over time. By noting titles that recur from decade to decade and among authors and publishers, we plot the continuities that bind the genre into a distinct identity. Simultaneously we illuminate aspects of the social process of cultural production characteristic of North India in this period. Thus we focus on the means of production (the

evolution of the printed text and its various formats), the producers of the text (the publishers), and the internal organization of authors (poetic lineages or akharas ). The chapter may consequently be read as a specific exercise in the sociology of culture as well as an extended addendum to canonical literary history.

The Sources of Sangit Texts: Old and New

The scripts of Svang and Nautanki, or more accurately librettos, are termed sangits ; this label or its abbreviation (san .) is almost invariably part of the title. Platts's Dictionary of Urdu defines sangit as "a public entertainment consisting of songs, music and dancing." However, as a printed rubric it denotes simply "musical drama." The origin of the word is disputed: it may be an adjectival form of the Sanskrit sangita (music) or a compound of sang (mime, drama) plus git (song).[1] In any case, the term distinguishes this class of texts as intended for musical performance, in contrast to poems or tales meant for silent reading or unaccompanied recitation.

Sangit manuscripts and booklets are probably as old as the theatre itself. Before the printing press came to India, handwritten scripts circulated among communities of actors and helped them memorize parts; they were sometimes collected by patrons.[2] Lithography made possible their duplication and publication, and it is in this form that they are preserved in the nineteenth-century collections of the libraries in London. With the introduction of inexpensive Devanagari printing in the 1880s, the Sangit entered the era of mass communication and became widely printed and reprinted, bought and sold.

Nowadays Sangit chapbooks can be purchased from pavement sellers specializing in popular literature.[3] These mobile retailers are usually found in a city's old sectors near a temple or market, their wares spread on the ground by day and packed up in a strongbox on a bicycle rack every night. The vendor who deals in Nautanki Sangits is likely to stock a variety of other items: collections of bhajans (hymns), vratkathas (women's religious narratives for fasting days), astrological almanacs, folk poems on martial legends like the Alha , traditional joke books (like Ghagh-bhaddari ), lokgit anthologies (women's songs, marriage songs), sex manuals, how-to guides, cheap editions of Hindu devotional texts (Ramcharitmanas, Bhagavad-gita, Hanuman-chalisa ), discourses by spiritual masters, film magazines, romances and paperback novels, and

detective stories; all are in Hindi. This fare contrasts with the stock at more prestigious sites—railway bookstalls, bookstores, hotel lobbies—where most material is in English, prices are higher, and packaging is more durable.

Among the popular publishing houses that supply the street vendors through a far-reaching distribution network, the most prolific publisher of Sangits is Shyam Press in Hathras. Other popular publishers include Dehati Pustak Bhandar (Delhi), Shrikrishna Pustakalay (Kanpur), Babu Baijnath Prasad (Banaras), and Bombay Pustakalay (Allahabad). These publishers advertise their current lists in conveniently subdivided catalogues, and on making a personal visit one can order specific Sangit titles uncut from the warehouse. In the late 1970s Frances W. Pritchett collected approximately one hundred contemporary Sangit texts from such publishers and donated them to the Regenstein Library of the University of Chicago, where they are accessible to researchers.

Older Sangits from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are held in the Oriental Manuscripts and Printed Books division of the British Museum (BM) and in the India Office Library (IOL), both now part of the British Library system in London. In 1867 the British Government of India passed the Press and Registration of Books Act (Act XXV of 1867), requiring that one copy of every printed or lithographed book issued in India be forwarded to the Secretary of State for India in London. The law was originally introduced to enable the Raj to tighten its control over Indian publications and apply stricter censorship.[4] However, it had the salubrious secondary effect of creating an unparalleled collection of books from India. The India Office Library (and in certain instances the British Museum) became the repository for these books and developed into a virtual copyright library for Indian publications.[5] In this way the British authorities, who probably had less use for chap-books of folk plays than for most types of indigenous literature, unwittingly ensured the preservation of a comprehensive body of folklore.

The British Museum holdings of Hindi, Panjabi, Sindhi, and Pushtu books are catalogued in a three-part publication beginning in 1893, with a supplement for Hindi books in 1913, and a second supplement in 1957. The Hindi acquisitions of the India Office Library are listed in two published catalogues of 1900 and 1902; the 1903-1944 catalogue of Hindi books is unpublished and must be consulted in the library itself.[6] Within these catalogues Sangit texts are not easy to locate, although they are listed by author and crosslisted by title or by "subject" (often literary genre). The difficulty stems from a British-designed tax-

onomy that overlooked or did not perceive the connection between the Sangit and the indigenous folk stage. In very few cases are the Sangit works listed under the drama sections of the subject indexes. In the earlier catalogues, Sangit texts are primarily classified as "Literature: Tales and Fables—Verse." The 1913 catalogue distinguishes between "Poetry—Narrative" and "Poetry—Historical," placing ordinary Sangit titles under the first and Sangits on the Alha epic theme in the second category. In the 1957 supplement, however, these are collapsed into the category "Literature: Poetry—Narrative and Historical Poems." Occasionally Sangits on saintly figures appear under the heading "Poetry—Mythological." These subject indexes point to the bibliographers' confusion regarding the genre and suggest a lack of awareness of its performance context. Similarly, individual bibliographic entries characterize the Sangit first as a "legend in verse" or "metrical legend," and later mostly as a "ballad." Only occasionally is the performative character mentioned, as in the description of Sangit puran mal ka (1878), "a popular romance, in a dramatised form," or Khushi Ram's Sangit rani nautanki ka (1882), "a love-tale, in verse, adapted for the stage." Looking in the title index under Sangit rather than in the subject index is therefore the quickest method of locating these plays, except in the earliest catalogues that lack the title index.

Of the two London collections, the British Museum has the better resources for study of nineteenth-century Sangits, and the India Office Library is superior for those of the twentieth century. The British Museum contains a total of 56 Sangit texts published between 1866 and 1912, plus another 109 published between 1913 and 1957. In the India Office Library, some 28 titles (including 10 duplicates of British Museum items) were published before 1902, and approximately 280 Sangits appeared between 1903 and 1944.[7] By any calculation these are remarkable resources, all the more so considering the lack of attention they have received until now.

With samples of texts from every decade of the last one hundred twenty years, the history of Nautanki as a folk literature lies open for study. Recurring stories, characters, and motifs can be easily identified, formal structures of language and meter can be historically analyzed, and the styles of different authors, schools, and regions can be contrasted. Furthermore, the printed Sangit yields valuable self-contextualizing information. Advertisements on back covers help to reveal the consumer audience for popular texts. Prefaces by editors may explain how a play came to be published, under what constraints, or with what

purposes in mind. Sometimes a poet's colophon includes descriptions of dramatic troupes, the roles and function of their personnel, and the musical instruments used. Invocations directed at patrons provide information on the circumstances of performance. As a result, although the libretto was originally devised as an actor's guide, in its published form it is a self-referencing document that supplies important clues to the evolution of the theatre.

Lithographed Sangits: 1866-1896

From the inception of British collection of vernacular works in 1867, two types of North Indian folk drama occur in large numbers: the Rajasthani khyal (or khel ) and the Hindustani sangit or sang . We have considered the development of khyal and its relation to Svang and in the previous chapter have determined that the Khyal folk theatre probably preceded the printed Sangits by about a hundred years. The earliest preserved Sangits in the British Library are Prahlad sangit (1866) and Gopichand bharatari (1867), both written by one Lakshman Singh (also known as Lakshman Das) and published from Delhi. Each of these was reprinted many times, indicating their great popularity; sixteen editions of Prahlad and twenty-seven of Gopichand were published between 1866 and 1883 (see figs. 4 and 5). Two editions of Prablad and three of Gopichand were written "in Persian characters," that is to say, in Urdu. The fact that multiple copies exist almost from the start of British collecting suggests an already established tradition of Hindi and Urdu folk drama. As with the khyals of Rajasthan, we conjecture that Sangit texts were copied and circulated before printing was known in the region. It therefore seems probable that these two texts were composed sometime before 1866; how much earlier we cannot say.

The widespread availability of the Sangit of Gopichand was noted by G. A. Grierson, who published a fragment of the text in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1885. "There is no legend more popular throughout the whole of Northern India, than those [sic ] of Bharthari and his nephew Gopi Chand. ... A Hindi version of the legend can be bought for a few pice in any up-country bazar."[8] The story concerns the conversion of a king to the ascetic way of life that Guru Gorakhnath embodied. The Sangit has remained a popular classic for over a century. I recently discovered contemporary reprints of the original edition in markets in Hathras and Jaipur (fig. 9).

Thematically related is the story of Harishchandra, a generous king

Fig. 9.

Title page of recent reprint of Gopichand bharthari by Lakshman Das

(Delhi, n.d.), collected from Jaipur bazaar in 1984.

who comes to earthly ruin by speaking and living the truth but who in the end receives salvation. A version by Jiya Lal was published in both Hindi and Urdu scripts in the 1880s. The Gopichand and Harishchandra plays, with their example of abdication of kingly duties for a renunciant's life, are medieval morality tales, inculcating otherworldliness and pursuit of spiritual perfection. Other popular Sangits too exhorted the faithful to renounce power and follow the example of the saints; the titles Puranmal (or Puranmal, Puran bhagat ) (see fig. 7) and Dhuruji both refer to spiritual exemplars admired in the late nineteenth century. The theme of kingly asceticism, popular for millennia in the subcontinent, may have gained prevalence in the disturbed political conditions of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century North India. Loss of power and title was part of everyday reality for the nobility, while the people experienced a dwindling of confidence in the moral authority traditionally expected of kings. The age demanded a model of virtue for future rulers and consolation for privilege usurped.

In counterpoint to these dour dramas of dispossession, the fantasy world of princes and princesses and of fairies and demons played on the nostalgia for bygone days that also preoccupied the late nineteenth century. The Indarsabha of Amanat was the prototype, a play that dominated the Urdu theatre for over seventy years. Its theme of love between a fairy and a prince was a legacy of the Persian dastan and had parallels in Indian folklore, as evidenced by the story of the fairylike Princess Nautanki who weighed only thirty-six grams. The formula of combining ribald love scenes (preferably between celestial women and mortal men), titillating cross-dressing, and bold melodrama featured in a number of popular romances of this period: Rup basant, Saudagar vo syahposh , and Benazir badr-e-munir .

Between 1866 and 1896, thirty-two titles appear as lithographed Sangits in the London collections. Half of them treat religious themes (seven legends of saints, nine stories from Ram and Krishna lilas ); more than a third are romances (nine Hindu or regional, three Islamic), and only a handful are heroic and contemporary stories (two martial chronicles, two modern stories). The most popular as measured by reprintings were the legends of saints (Gopichand, Puranmal, Raja harishchandra, Dhuruji, Prahlad ) followed by the romances Rup basant and Saudagar vo syahposh . The plays were most frequently published from Delhi by Mishra Bhagvan Das of Brahman Press and by Munshi Naval Kishor; from Meerut by Pandit Hardev Sahay of Jnan Sagar Press and

Lala Natthumal Seth of Jvala Prakash Press; and from Banaras by Mum shi Ambe Prasad.

It is difficult to ascertain much about the authors at this time. Rarely does the author's name appear on the title page. Instead the poet usually mentions himself in an invocatory verse, where he speaks as a suppliant requesting blessings from the deity:

Lachhman is your servant, Lord, protect my honor.

(Gopichand , 1870)

Baldev is your servant, give my heart knowledge.

(Krishnalila , 1868)

I am your servant: my name is Dalchand the wise.

(Sorath , 1878)

Ramlal joins his palms and bows his head at your feet.

(Puranmal , 1878)

Infrequently a bit of biographical information appears at the end of the work. Jiya Lal, author of Harichandra (1877), describes himself:

I am head of the guards, a Jain scribe by caste.

In the world my name, Jiya Lal, is famous.

My name Jiya Lal is famous, my hometown is Faraknagar.

In Chhaproli I received this story already composed.[9]

The fragmentary information that is available seems to suggest high-caste backgrounds for many authors and publishers in this period, for example, that of Brahmin, Kayasth, Jain, Rajput, and other literate castes.

The manuscripts are handcopied by scribes with highly ornamented covers featuring illustrations of central scenes and characters. Often the pages of text are also illustrated in a manner similar to folk styles of painting of the time. The widespread use of visual images together with printed text suggests a midway point on the continuum between simple images and learned books, comparable to the chapbooks of sixteenth-and seventeenth-century France. Such materials, in the view of Roger Chartier, suggest the multiple uses to which a text could be put.[10] For the literate classes the text constituted reading matter, while for those unable to read the pictures outlined the narrative, served as a basis for oral (including memorized) recitation, and rendered the written word a familiar part of everyday life.

The appearance of these texts is remarkably similar from one publisher to another, the handwriting of the scribe being the most individualizing feature. The plays are most frequently thirty-two pages in length,

and the page size is 6" by 9½". Urdu versions of some are published separately or back to back with the Devanagari. The title is boldly displayed in Devanagari and often Urdu as well, with the publisher's details appearing at the bottom of the page. In the early manuscripts, the poetic lines are penned running on continuously with no indentation. Only stanza numbers and full stops are inserted to show where lines end. In later texts, lines and stanzas are separated and centered on the page, and the characters' speeches are prefaced by indications such as "reply of the queen to the king." The names of the meters are specified in full or abbreviated form in all the manuscripts of the period.

In the early period no differentiation into rival arenas or akharas occurred, as far as we can tell. Competition among publishers and fear of plagiarism were, however, of some concern. The cover of Sangit budre munir ka (1876) carries a fifty-word plot summary instead of the usual illustration, and the back cover issues this admonition:

All publishers take note that this Sangit Budre [sic ] Munir, or Fairy Princess, was very carefully corrected and published by Pt. Hardev Sahay, after taking permission from Lala Dhannulal's son Munshi Basant Ray and Munshi Umrao Singh. No one may publish it without permission.

Such warnings frequently accompanied the publication of new material, together with notices proclaiming the play's authenticity.

How widely distributed such lithographed plays were we cannot determine, for the title pages bear no mention of the number of copies printed, as later ones did. These plays contain no references to troupe organization or details of performance. However, there is little doubt that the impetus for the creation of these dramas was the presence and continuing expansion of a Hindi and Urdu folk stage in the region around Delhi, Meerut, and Banaras.

Natharam and the Indarman Akhara of Hathras: 1892-1920

At the close of the nineteenth century, major changes in the organization, style, and subject matter of Svang took place. The popular theatrical activity that had been diffused over a fairly expansive area converged on the town of Hathras, where the most visible changes occurred. Hathras is in the district of Aligarh in western Uttar Pradesh. Located in proximity to both the Vaishnava pilgrimage sites in Mathura district and the former Mughal capital at Agra, Hathras became an important

independent Jat kingdom under the chieftain Daya Ram in the early nineteenth century. The area around Hathras was renowned for its unusually rich commercial agriculture, with cash crops of indigo and cotton providing the base for a prosperous economy.[11] It continued to flourish even after the British seizure of Daya Ram's kingdom in 1817 and the revolt of 1857.[12] The town had a large population of money-lenders (sahukars ); together with the wealthy agriculturists they formed a sizable patron class to the service groups, including artisans and performers. Affluent individuals like Hanna Singh Dalal are said to have squandered fortunes on the maintenance of Svang members, construction of their houses and stage facilities, and expenses of special events.[13] As a railway junction later in the century Hathras continued to thrive, a commercial center in a predominantly agricultural region. The constant flow of travelers to festivals and fairs ensured a ready audience for the folk theatre.

The organizational basis of Svang acquired greater structure and visibility with the development of the akhara system in Hathras. The akhara (wrestling-ground or arena) was already associated with teams and lineages of folk poets of lavani and khyal . The first and foremost of the Hathras Svang akharas was founded by a poet named Indarman, who immigrated from Jahangirabad in Bulandshahr district sometime in the 1880s.[14] A Chhipi (from the artisan caste that prints cloth), he was prevailed upon by his fellows in Hathras to visit and initiate them into the art of poetic improvisation for which he was well known. As a devotee of the goddess, Indarman enjoyed the reputation of a seer and, although he himself was illiterate, exerted a spiritual leadership among his followers. The most prominent of these were Govind Ram and Chiranjilal, both Chhipis and prolific poets in their own right. Under their leadership, the Indarman akhara began exhibiting Svangs in Hathras, probably in the 1880s.

Although it is said that Indarman only dictated verses to his disciples and authored no Svang himself, a text has come to light in the London collections that is almost certainly a composition of Indarman—but whether he was the Indarman of Jahangirabad and Hathras we cannot be sure. The work, Khyal puran mal ka (1892), is not a Rajasthani khyal but a Khari Boli Sangit in the style that soon became the standard for the Sangits of Hathras. One of the first to be printed using machine-made type, it was published in Calcutta by Ganesh Prasad Sharma. Indarman's name does not appear on the title page, but it is scattered in signature verses in at least ten places throughout the play, in various

forms such as Indarman, Indraman, Indar, or Inda.[15] New poetic structures characterize the text, and it bears a distinctive cover design, lending credence to the idea that it was an innovative work. The meter daur is introduced for the first time here.[16] The title page is enclosed by a simple border, with the name of the play printed at the top, then the publisher's name, mention of registration under Act XXV of 1867, a small picture of the elephant god Ganesh, and lower on the page the address and name of the printer, the Christian era date, number of copies printed, and price. This bare but elegant format became the basis for Hathras Sangit covers in the following years.

Whereas we know little about Indarman, we are on firmer ground with his most illustrious disciple, Natharam, called Nathuram or Nathumal in his early plays and later renowned as Natharam Sharma Gaur. Born in 1874 in the village of Dariyapur to a Brahmin family, Natharam came to Hathras as a child guiding his blind father, Bhagirathmal, and singing for alms. With his sweet voice and charm, he attracted the attention of Indarman's disciple Chiranjilal and was soon adopted into his akhara , where he learned the arts of singing and dancing as well as reading and writing. He quickly became a star, playing the female parts with irresistible flair; he later revealed great skills as a poet, organizer, and publisher.

The Indarman akhara had its headquarters at Kila Darvaza in Hathras. Nearby was a temple, Dauji ka Mandir, where an annual festival was held. Natharam rehearsed and presented a new play every year for the large crowds who frequented the festival (baldev chat ka mela ); after building up a reputation in this way, he was invited to tour outside the city. Around 1890 Natharam and his teacher Chiranjilal organized a professional troupe that earned a tremendous reputation as it traveled throughout northern India. The eager reception that greeted them is attested in the earliest Sangit attributed to Chiranjilal and Natharam, Chandravali ka jhula (1897):

Announcement

Let it be known to all good men that the entertainment of the troupe from Hathras has been shown in various places in Kanpur, and many gentlemen have gathered for it and all their minds have been pleased. Seeing the desire of these good men, we have published the same entertainment, Chandravali's Swing or The Battle of Alha and Udal , for the amusement of their minds, so that whenever they read it, they will obtain happiness and remember us. Take heed, this opportunity will not come again. Make your purchase quickly, or the chance will slip away and you will be left wringing your hands. All of Indarman's books are available from us.[17]

This statement suggests that the publication of a Sangit followed its performance in a given locale, in response to popular demand for the text.[18] Note that by 1897 Indarman's name was famous enough to warrant the claim that "all of Indarman's books are available from us."

This play is another early example of the new typeset format. The cover drawing has disappeared; instead, an image of Ganesh adorns the top of the page. Prominently placed in the middle is a list of all the meters and melodies included in the text. Whereas the older Sangits contained only a few meters, such as doha, chaubola, kara , and ragani , the Hathras poets employed a plethora of verse types, giving greater variety and virtuosity to their singing style.

Subject matter in the period from 1890 to 1910 was also changing. While the old stories still held their own, episodes from the martial epic of Alha and Udal enjoyed particular esteem. By 1902, the Chiranjilal and Natharam team had published ten episodes from the Alha cycle, and the number kept increasing through the next two decades.[19] The famous Amar simh rathor , another tale of Rajput valor, was first published in 1912. Unlike the earlier saintly legends and make-believe romances, these tales are based on historical events in the not-so-distant past. This celebration of India's warring heroes in folk theatre parallels the resurgence of political activism in the early twentieth century, suggesting that a model of confrontation may have begun to replace the older attitude of religious quietism.

Several turn-of-the-century Sangits yield interesting details about the personnel of the troupe of Chiranjilal and Natharam. The following description closes Udal ka byah (1902):

The Indar akhara in Hathras is like the court of Lord Indra:

The teachers (ustads ) are Ganesh and Chiranji and the

director (khalifa ) is Gobind.

Jivaram Das and Parshadi are servants of Vishnu's lotus feet,

Madan, Janaki, Hira, and Lachchha are known throughout

northwestern India.

Natharam the Brahmin seeks the shelter of Bhairav and Kali,

Dulari and Udayraj dance circles around the king.[20]

The first line compares the entire troupe to the assembly of lord Indra, the glamorous image of the indarsabha frequently invoked in popular culture. The second line refers to Natharam's trio of gurus, Govind, Ganesh, and Chiranjilal. The "servants" may be musicians or other supporting staff (cook, barber, or laborer) but were clearly Vaishnavas, as opposed to Natharam's Shaiva or Shakta proclivities. Madan, Janaki, Hira, and Lachchha appear to be renowned actor-singers; Dulari

and Udayraj specialized in dance. The feminine names "Janaki" and "Dulari" probably indicate female impersonators.

In the standard closural apology the poet alludes to the young Natharam's high caste, physical grace, and poetic talent and begs forgiveness for errors or offense committed.

The Sangit is concluded, the heart pleased and free of sorrow.

The lord's servant, Chiranjilal, lives in the city of Hathras.

Thanks to him, the coquettish Brahmin boy Nathamal lives

happily,

A jewel of the Gaur lineage, creator of spontaneous poetry.

May all good men read this and deem his effort a success:

Excuse his errors and wrongs, knowing him to be a child.[21]

Up to 1910 Chiranjilal and Natharam's plays were all published in Kanpur. Perhaps the initial demand for printed Sangits was greater in Kanpur, or possibly Devanagari printing facilities did not reach Hathras, a smaller town, until later. It is conceivable that the akhara's poets only amassed sufficient capital to finance a local press after 1910. Shyam Press of Hathras, which was originally owned and operated by Natharam Sharma Gaur and is now in the hands of his son, Radhavallabh, began its publishing activities about 1925.

The true authorship of the Sangits printed under Natharam's name is difficult to determine. Although approximately fifteen plays list Chiranjilal and Natharam as joint authors, how the poets divided the labor between themselves is unknown. By 1908 either Chiranjilal had died or his influence had diminished, for a verse speaks of him as the ustad in the past tense.[22] Natharam then began taking sole credit for some of his earlier collaborations with Chiranjilal.[23] Several plays first published between 1910 and 1920, such as Sangit harishchandra , have clear references to Natharam in their colophons and may be his own compositions. After 1920, most plays published under the Indarman akhara name were credited to Natharam, but probably few were wholly his work. By then the akhara had attracted a number of ghostwriters who were turning out Svangs in Natharam's style on new themes.

During the period from 1920 to the present, Sangits of the Indarman akhara were issued and reissued in very large numbers under the name of Natharam. Many of these were actually written by Ruparam of Salempur, who started employment with Natharam around 1920.[24] He composed a number of stories that present new types of heroes and heroines, contemporary or recent historical characters who are in pursuit of justice. These may be outlaws in the service of the poor, such as

Fig. 10.

Title page of Sultana daku by Natharam Sharma Gaur (Hath-

ras, 1982). The actual author is Ruparam and the likely date of compo-

sition in the 1920s. The portrait of Natharam and cover details are typi-

cal of this most popular akhara .

Sultana daku (fig. 10), women warriors avenging their husbands in battle like Virangana virmati , or ill-treated daughters and daughters-in-law, Shrimati manjari, Andhi dulhin , and Beqasur beti . Ruparam also prepared texts for such classics as Laila majnun, Hir ranjha, Bhakt puranmal and Rup basant , and he continued writing under Natharam's imprint even after the latter's death in 1943. Rupa's distinctive signature line appears at the end of the plays:

Enough! Rupa's pen stops here. (Virangana virmati , pt. 1)

Natharam says, "Rupa, stop your pen now." (Sultana daku )

Natharam the Brahmin says, "Rupa, stop your pen." (Andhi

dulhin )[25]

Using an assortment of clues, I have attempted to assign approximate dates of first publication to many of "Natharam's" Sangits. It appears that a minimum of twenty-six were first published between 1897 and 1920. From 1921 to 1940, new publications totaled fifty, and in the categories after 1940 and undated, thirty-seven appeared.[26] The Indarman akhara was thus the most successful and long-lived of the Hathras akharas in producing and publishing Sangits. Its texts, considered the authoritative versions of Nautanki in its present stage of revival, are still reprinted and sold.

The poet Govind, one of Natharam's acknowledged teachers, was another major figure in the Indarman troupe between 1900 and 1910. Using the name \ Ram or Govind Chaman, he published a number of plays, some under the Indarman imprint, some in conjunction with or under the tutelage of an ustad named Tota Ram.[27] These were mostly published by Babu Gokulchand Publishers in Aligarh and Umadatt Vajpeyi of Brahman Press in Kanpur.

Govind's pen name chaman , meaning "garden," appears in an opening doha that occurs in several of his plays, praising the author and his poetic virtuosity.

doha | This history is in the form of a garden (chaman ), whose root is |

It contains various meters (chhand ) and melodies (ragini ), the | |

chaubola | The many classes of flowers bloom on every garden bough, |

Green foliage appears on each branch, each poetic category. | |

On every trunk sprout strange and unusual forms of verse | |

Each tree of literature the gardener-poet waters as he composes.[28] |

Govind Ram's plays also include details of the Indarman troupe, the names of its members, and their respective roles and functions.

In the city of Hathras, the Indra akhara wears the crest of victory

as its mark.

Its poets, Radherai, Baldev, Kalan, and Murshad are full of the best qualities.

Ustad Tota Ram is a mine of wisdom and knowledge.

Ganpati and Miyan Muhammad are not vain of their learning and skill.

The director Govind Ram always narrates the Svang.

Chiranjilal ever performs the latest turns of phrase.

Parshadilal instructs the group so humorously.

Natharam the Brahmin, Madan, Janaki, and Hiralal too are singers,

They uphold their teachers' respect and from this achieve victory.

Ramlal Chaubeji sings the praises of the Lord.[29]

The continuity in personnel between this and earlier descriptions confirms that Govind was associated with the same akhara as Chiranjilal and Natharam.

Other Hathras Akharas

The three decades before the arrival of motion pictures (1890-1920) witnessed a proliferation of playwriting and theatrical activity in Hathras. These were heady days for Svang; in addition to Chiranjilal, Natharam, and Govind Ram of the Indarman akhara , poets such as Muralidhar and Batuknath Kalyan were producing plays by the dozens. The akhara system fostered competition among troupes, and performances often took place in a contest situation or dangal . In this atmosphere of rivalry, poets naturally suspected that others might plagiarize their compositions. The practices of providing a signature couplet (doha ) on the cover of the play, identifying the ustad of the akhara , and later picturing the author himself, perhaps originated as devices to prevent literary theft.

Around 1900, the page size of printed Sangits was reduced to its present 5" by 8½". Two vertical lines of a signature doha flanked an image of Ganesh at the top of the page. For the Chiranjilal and Natharam team, the doha read,

Gentlemen seeking the authentic Indarman khyal

Should buy and read those with the name of Chiranjilal.[30]

After Chiranjilal's death, when Natharam began publishing plays under his own name, he changed it:

Those gentlemen who especially seek the priceless plays (khyal )

of Indarman,

Read "Natharam" in the imprint and gladly purchase them.[31]

Note that the term khyal was still being used to refer to the Hathras Svang.

After the Indarman akhara , the second in importance was the akhara best known by its poet, Muralidhar Ray (or Muralidhar Kavi). Muralidhar was the disciple of one Pandit Basudev, or Basam, whose name is invoked in his plays.[32] This akhara is further connected with the names of Sedhu and Salig.[33] In Sangit samar malkhan (1907), Muralidhar pays homage to Salag, Sedhu, Basam, and Ballabh.[34] The London collections contain several published plays confirming the authorship of Salig (or Shaligram) and Sedhu, although whether they constituted two persons or one remains unclear.[35] The publication dates do not help much to construct the lineage of this akhara , but the fact that Nihalchand published most of Muralidhar's plays as well as those of Shaligram and Sedhu Lal (and may have been related to Shaligram) links these individuals into some sort of unit.

Nine Sangits by Muralidhar are available in London; these are primarily incidents from the Alha epic cycle or romances (Nautanki shahzadi, Siyeposh ). A prolific writer, Muralidhar seems to have been in close competition with the Indarman akhara . The subjects chosen, manner of telling the story, style of printing, and cover design are so similar that one suspects a good deal of borrowing and mutual influence. Muralidhar's publisher, Nihalchand Bookseller of Aligarh, claimed to have an exclusive contract with the popular poet, for the inside covers feature a notice declaring, "All of Muralidhar's plays are published by Nihalchand by right." Nihalchand also seems to have been preoccupied with respectability: "We publish no obscene, vulgar, or impure plays ... and we are having such plays written as will benefit the country."[36]

The third Hathras akhara that developed in this period was known as the Nishkalank (blameless) akhara . Its founders were Sahdev, Mukund Ray, and Shivlal. The chief poets, Muralidhar Pahalvan (the wrestler) and Natharam Jyotishi (the astrologer), bore names that are identical in part with members of the first two Hathras akharas , namely Muralidhar, disciple of Basam, and Natharam of the Indarman akhara . This confusion may have been intentional—a ploy to lure unsuspecting customers to buy their plays. Natharam Jyotishi's son, Chhitarmal Jyotishi, and one Jiman Khan also composed poetry for this group.

The IOL and BM catalogues do not always distinguish Muralidhar Kavi, disciple of Basam, from Muralidhar, disciple of Mukund Ray; as plays by "Muralidhar" are the second most numerous after those of

Natharam, their correct identification is often problematic. To make a distinction we must examine the title page. The signature doha surrounding the Ganesh of Muralidhar's Puranmal jati (1915), for example, reads:

The founder of Nishkalank was Shri Ustad Mukand,

Its pure poetry is composed by Shivlal, Muralidhar, and

Harnand.[37]

This identifies the poet as Muralidhar of the Nishkalank akhara . Nishkalank's publishers were Lala Hotilal Motilal and Buddhsen Bhagvan Das, both of Hathras; these publishers' lists on the back covers indicate that about thirty or forty Sangits, with Alha episodes again dominating, had been published by 1915. Ram Narayan Agraval says that this akhara was supported by Hanna Singh, a wealthy merchant through whose largesse a permanent stage for the troupe was constructed. Their gathering place in Hathras was at Sadabad Darvaza. A number of Nishkalank's Svangs, such as Mah-e-rukh and Mah-e-chaman , are still remembered as occasions of great pomp and display. Hanna Singh was famous for riding through the streets and distributing rupee coins and guineas to the crowd.[38]

The fourth Hathras akhara was that of Batuknath Kalyan, whose main poet was Vaidya Chiranjilal (notice again the similarity in name to another poet). This akhara was possibly the first to publish its plays in the Braj region, for three of its Alha episodes, Brahma ka byah, Malkhan ka byah , and Udal ka byah , were published in Mathura in 1902 by Lala Hotilal Motilal. The cover doha does not mention the founders of the akhara; rather it emphasizes the authenticity of the text:

When you find a jewel, don't settle for glass.

Read from start to finish, and pick the true from the false.[39]

The word "jewel" (chintamani ) may be a pun on the name of one of the troupe's actors; the final lavani mentions a Brahmin, Chunni Chintaman, who sings verses, as well as a possible guru, Siriya, who has died and gone to heaven. Reference is also made to Raghuna (or Raghunath), the troupe's patron. Agraval indicates that this troupe was famous for its extravagant procession employing many decorated elephants on the occasion of the performance of Bahoran ka byah .[40]

Apart from these important and well-remembered akharas , a number of lesser poets were also writing Sangits in the Braj area at this time. The London catalogues list a dozen or more such writers before 1920,

who composed on romantic, martial, and social subjects. We can also measure the scope of publication by examining the lists printed on the backs of Sangit covers. Nihalchand Bookseller, for example, claimed to have published eighty Sangits by Hathras poets by 1913. Significantly, many of these dramas were published. in Urdu script also. Nihalchand notes that thirty-five of the eighty had already appeared in Urdu and the rest were in the process of publication in Urdu.[41] From this it is clear that Hindi and Urdu readers alike sought Svang texts, indicating the mixed following that the dramatic literature enjoyed.

The custom of featuring the poet's or ustad's picture on the title page became established by 1920. A 1915 version of Gorakh machhandar nath by Chainaram and Khumaniram Mistri sheds light on the reasons for the practice: "The purpose of giving photographs in this book is to show that these are good men who are completely worthy, and as their troupe is in need of every item and they require assistance, their pictures have been given here." Other reasons may have been to publicize actors or directors whose faces were well known and to help semiliterate purchasers make the correct choice. At first full-page portraits were included as frontispieces to the plays (see fig. 11 of Trimohan Lal from Alha manaua and fig. 13 of Shrikrishna Pahalvan from Malkhan samar ). Eventually the photographs were integrated into the cover design, occupying the center of the page where detailed lists of the contents and meters had previously been placed. The image of Ganesh now vanished, and the Sanskrit blessing, "hail to Ganesh" (sriganesayanamah ), was poised at the top of the page.

Extension of Nautanki to Kanpur: 1910-1930

As the Hathras Svang spread to other regions in the second decade of the twentieth century, the term nautanki became attached to this performance style. Virtually every poet in his own way retold the popular tale of the princess Nautanki. Evidence of early use of the word to indicate the genre occurs in Shiv Narayan Lal's Sangit sundarkand rah nautanki , "The musical play 'Sundarkand.' in the Nautanki manner." Rah means "road, way; manner, method; custom, fashion," and here designates the performance genre. At the back the author states:

Submission

These days Nautanki is becoming extremely popular. But there is fear of the character being corrupted by books on bad subjects. Therefore I have adapted

the Sundarkand of the revered Ramayana in the style of Nautanki (nautanki ke raste nikala hai ). If my readers appreciate this, then gradually I will bring out all the kands [of the Ramayana ].[42]

The declaration by Shiv Narayan Lal points to public objections to the corrupting influence of Nautanki performances, matched by greater self-consciousness among poets regarding the reception of their work. Moralistic condemnation of the theatre emanated from several quarters. The Dramatic Performances Act of 1876 established a legal basis for the colonial government to prohibit performances deemed defamatory and threatening to the government as well as those likely to deprave and corrupt persons present.[43] Social reform movements such as the Brahmo Samaj and Arya Samaj also sternly criticized popular theatre, and by this time their messages had extended to the smaller urban centers. Authors and publishers had been subject to strict censorship ever since the registration act of 1867. It is thus not surprising to find the competitive publisher Nihalchand Bookseller admonishing his prospective authors:

Notice [English word]: We require intelligent and educated poets to write superior Sangits. Let those who are accomplished in the business of writing doha, chaubola, kara, lavani, dadra, qavvali, bhajan, bahr-e-tavil , and so forth compose true Svangs on subjects pleasing to us and they shall collect their reward. Let them not damage the country by writing lewd and impure jhulnas and so on, boasting of being poets.[44]

Shaligram, the schoolmaster-cum-ustad of the Basam-Muralidhar akhara , likewise imparts a lesson to the poets of his day:

Lesson

Among those who write Svangs are particularly foolish and ill-educated men who compose vulgar, impure, plotless, and completely useless (maha raddi ) Svangs and do a great disservice to the country. Such people should not trouble themselves in vain with this kind of writing ... because they do not enhance their personal esteem; on the contrary they increase their ill repute.[45]

Shaligram goes on to advise the singers of jhulnas not to indulge in verbal abuse of one another's female kin but rather to fill their songs "with sentiments of devotion and valour."

These statements imply that vulgar language and erotic topics were part and parcel of Svang and Nautanki in the early twentieth century. At the same time, the countervailing effects of colonial censorship, curiously reinforced by the reformist social agenda of the nationalist

movement, were beginning to be felt. Just as the mass appeal of the Svang stage became recognized, some quarters attempted to convert Svang and Nautanki to a more edifying form, one beneficial to the building of moral character. The impact of the new political ideology seemed to intensify just as Nautanki took root in Kanpur. It left a clear mark on the early career of Shrikrishna Khatri Pahalvan, the founder and chief proponent of the Kanpur style.

From the end of the nineteenth century, Hathras troupes had performed regularly in Kanpur, and the Sangits of the Hathras akharas were published there in large numbers. Kanpur's history was intertwined with the military and economic purposes of the British Raj. It was one of India's largest grain markets in 1810. The stationing of ten thousand British troops in its cantonment caused the population to rise dramatically in the early nineteenth century. As with the area of Hathras, the lands around Kanpur were very fertile; in response to the army's demand for fruits, vegetables, and tobacco, "an island of relative agricultural prosperity was created in the midst of the depressed middle Doab."[46] After the opening of railway lines connecting the city to Calcutta and Lucknow in the 1860s, the industrialization of spinning and tanning turned Kanpur into a manufacturing center surpassed only by Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras. In 1901 the semiindustrial male labor force was estimated at twenty-seven thousand.[47] Rapid social mobility characterized the society, especially among the lower castes, yet westernization in the sense of interest in British education, culture, nationalist politics, or even religious life scarcely existed. These conditions helped create both the audience and commercial structures that sustained popular entertainments like Nautanki, while minimizing the reformist opposition that might have put a damper on such activities.

Kanpur began to develop its own brand of Nautanki sometime around 1910. One of the first local akharas was that of ustad Chandi Lal and poet Bhairon Lal, whose Jagdev kankali was published in 1914 by Umadatt Vajpeyi of Brahman Press, Kanpur. Chandi Lal was introduced as a "resident of Kanpur" on the title page, and thirty-one titles appear on the back cover in a publication list, indicating an already well developed playwriting tradition based in the city.[48]

The poet Trimohan Lal was an important link between the Hathras Svang and the new Kanpur Nautanki (fig. 11). A native of Kannauj, about fifty miles northwest of Kanpur on the Ganges River, he went to Hathras to become a disciple of Indarman but later established his own troupe in Kanpur and published all his plays there and in Kannauj.[49]

Fig. 11.

Portrait of Trimohan Lal of Kannauj, frontispiece to Alha manaua

(Kannauj, 1920). By permission of the British Library.

Trimohan was a good nagara (kettledrum) player as well as organizer, and Agraval credits Trimohan with instituting scene changes following Parsi theatrical practice. He is also said to have introduced female singers to the Nautanki stage.[50] Curiously, his compositions are described on their covers as phulmati krit (made by Phulmati), a usage usually indicating the poetic mentor or guru rather than the actual author. Phulmati is a female name, and this strange heading suggests that Trimohan Lal composed his plays in conjunction with or for a certain Phulmati. It is possible that Phulmati was an actress or perhaps a transvestite.

Trimohan Lal's plays carry his picture on the title page plus the following doha:

Beware the false book, pay attention please.

This is the real sign: identify the photo and buy this.[51]

Most of his Sangits from the early 1920s are catalogued under the name of the twosome, Manni Lal Trimohan Lal, but nothing is known of Manni Lal.[52] A recently reprinted copy of Trimohan Lal's Khudadost

Explicit political comment and concern with contemporary events are noticeable in several Kanpur plays that retell the tragic massacre at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar. One of these, Rashtriya sangit julmi dayar , written by Manohar Lal Shukla in 1922, bears an unusual cover image in allegorical style (fig. 12). A whip-flailing policeman named Martial Law holds the mantle of a woman named Afflicted Punjab, threatening to disrobe her while she prays to Lord Vishnu (an allusion to Draupadi in the Mahabharata ). The law books, labeled Vyavastha, lie unattended on the ground, while in the corner a male figure resembling Mahatma Gandhi, named Satyagraha, sits sadly in contemplation. After recounting the historical incident from a child's point of view, the play ends with an element of wish fulfillment, when the collective ghost of the murdered citizens comes to the evil General Dyer seeking revenge, beats him up, and forces him to release the prisoners he arrested.

Shrikrishna Khatri Pahalvan

Just as the Indarman akhara and its leader, Natharam, dominate the Hathras Svang, so Shrikrishna Khatri Pahalvan's name is synonymous with the Nautanki of Kanpur. As troupe organizer, actor, author, and

Fig. 12.

Title page of Rashtriya sangit julmi dayar by Manohar Lal

Shukla (Kanpur, 1922), on the incident at Jallianwala Bagh. By permis-

sion of the British Library.

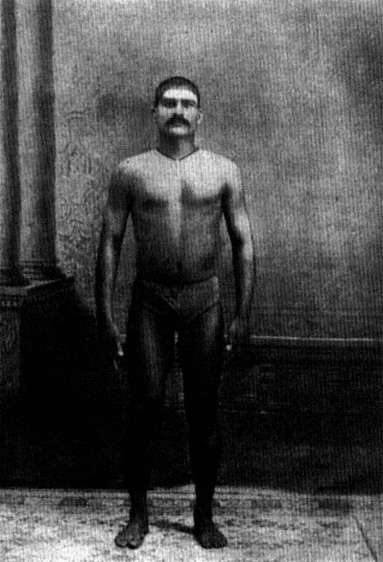

publisher, his influence extended to all aspects of the Kanpur stage in the 1920s and continued for forty years or more.[54] It seems that Shrikrishna made his living as a tailor before he became firmly established in the Nautanki business. The reverse covers of several plays feature advertisements for his shop: "Every type of tailored clothing is sold wholesale, such as coats, shirts, kurtas, women's jackets, waistcoats, three-piece suits, two-piece suits, and so on." Obviously he was also a wrestler (pahalvan ). His Sangits carry a full-length portrait of the poet, standing in a proud posture clad only in a loincloth (fig. 13).

Shrikrishna's early plays dealt with historical figures such as Haqiqat Ray, Maharani Padmini, Shivaji, and Virmati, who defended Hindu faith and territory against Muslim armies and were in most cases martyred. At this time, Shrikrishna was under the influence of the Arya Samaj, a Hindu reform movement espousing the superiority of ancient Vedic civilization. Several of these plays were published expressly for the Arya Sangit Samiti of Kanpur, and the Samiti's name is listed on the covers. There are also internal references to the Samiti and the founder of the Arya Samaj, Dayanand Sarasvati. The mangalacharan of Maharani padmini (1919) concludes with: "May everyone spread the objectives of the Sangit Samiti." This play also closes with a moral lesson based on the promulgations of the Arya Samaj:

Friends, fellow Indians, awake from your stupor!

India produced goddesses like this one, who burned themselves

on the pyre and saved their honor.

If you wish the country to progress, take steps to preserve the Hindu faith.

Rani Padma was burnt to ashes. Hail Dayanand! The story is finished.[55]

Similarly, in Haqiqat ray , reported to be Shrikrishna's first play:

Look, friends, at Haqiqat's sense of duty.

He got beheaded to uphold the Vedic faith.

This only is my request: don't abandon your religion.

Hail Dayanand! The story is finished.

The cover page of Maharani padmini includes the following note: "Warning! It is strictly forbidden to perform this Svang with dancing." This unusual prohibition was probably intended to protect the reputation of the Arya Sangit Samiti, since it could not afford to be seen countenancing nach . (Dancing of course remained an important element in Kanpur Nautanki.) These texts indicate the strong influence of the Arya Samaj on the young Shrikrishna, when he accompanied his treatment of patriotic historical subjects, a feature of his output until around 1930, with a Hindu revivalist tone bordering on communalism.

Fig. 13.

Portrait of Shrikrishna Khatri Pahalvan of Kanpur, frontispiece to

Malkhan samar (Kanpur, 1920). By permission of the British Library.

Later he turned to the middle-class social milieu that characterized the comedies of the Parsi theatre, choosing characters from the nouveau-riche Seth class and their servants, as well as government employees, students, and other contemporary figures. Examples of these subjects in the London collections are "The Eye's Magic" (Ankh ka jadu ), "Devotion to the Husband" (Pati bhakti ), "The Loyal Accountant" (Vafadar munim ), "The Valiant Manjari" (Shrimati manjari ), "The Punjab Mailtrain" (Panjab mel ), "Flute Girl" (Bansuri vali ). Some of these stories were based on current Parsi plays or film hits.

The title page of Virmati (1921) contains the characteristic doha of Shrikrishna's early plays:

The imprint gives information on the name and the mark;

Inside is the photo of Shrikrishna Pahalvan.

The same play mentions two important co-writers in the colophon:

Panna the poet's pen has stopped and Lakshmi Narayan says it is

morning.

A number of early plays are listed under the dual authorship of Pannalal Shrikrishna; possibly Pannalal's contribution was comparable to that of Ruparam who worked for Natharam of Hathras. Lakshmi Narayan's name stands alone in the colophons of several Sangits. As with the other famous poets, it is impossible to determine which plays published under Shrikrishna's picture are truly his own compositions.

In the early days, Shrikrishna's plays were published by Umadatt Vajpeyi, the leading popular press in Kanpur, but eventually he opened his own publishing concern, Shrikrishna Pustakalay in the Chauk. According to his son, Pooranchandra Mehrotra, who now operates the press, seventy-five million copies of Shrikrishna's books were published and sold up to 1971. A 1987 publication, Sangit vir vikramaditya , lists over one hundred Sangits of the Great Shrikrishna Sangit Company. Shrikrishna received the annual award of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, Delhi, in 1967.

Another popular poet of Kanpur, judging from the London collections, was Chhedilal, who often composed with Devidas. Seven of his Sangits, mostly on older themes like Laila majnun, Sultana daku, Amar simh rathor , and Virmati , were published between 1928 and 1932. Other Kanpur poets like Madhoram Gulhare appear to have been competing with Shrikrishna as the popularity of Nautanki spread in this region.

Recent Developments

Beyond Kanpur, publishers in all the major towns of Uttar Pradesh sought out popular plays and encouraged the local troupes by publishing their scripts. The IOL has a particularly large collection of Sangits for the period from 1920 to 1942. Although most were composed by minor poets, a list of the cities in which they were published gives an idea of the geographical extent of Nautanki's popularity: Ambala and Amritsar in the Punjab; Bhiwani, Hisar, and Sirsa in western Haryana; Beawar in Rajasthan; Jhansi and Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh; south as far as Bombay; Meerut, Moradabad, Bulandshahr, and Aligarh in western Uttar Pradesh; and Lucknow, Kanpur, Etawah, Gonda, Allahabad, and Banaras in eastern Uttar Pradesh.

Toward the end of this period, playscripts in the distinctive style of the Haryana Sang appear in the London collections. Pandit Dipchand of Khanda, one of the founders of this tradition, is represented by two plays, Rani mahakde va jani chor (1927) and Nautanki shahzadi (1932), both published in Muzaffarnagar. The IOL contains fourteen Sangits dated between 1937 and 1939 published by Lakhmi Chand, the most famous exponent of Haryanvi Sang. These are mostly on subjects familiar to Nautanki, such as Laila majnun, Prahlad , and Hir ranjha . The metrical treatment is different, however, the verse form ragani replacing the chaubola; the language is the local dialect, Haryanvi. The music in Haryana Sang is simple and resembles folk song, in contrast to the virtuosity of the Hathras Svang.[56]

Since the 1940s, Nautanki performance has been in a decline, caused in large measure by the powerful impact of cinema and television on the traditional performing media. Competition from the Bombay commercial films has exerted particular pressure on Nautanki. But surprisingly, the printing and reprinting of Sangit chapbooks proceeds unabated. The small presses all over North India continue to churn out new covers for the old texts, changing the date each year as the publication runs reach into the tens of thousands. The classic stories dominate the field, and the most esteemed texts for purchase remain those of Natharam and Shrikrishna.

New tastes and trends in popular culture, however, are also quickly absorbed. Two of the latest texts to join the repertoire are Jay santoshi ma , based on the fashionable religious film lauding the goddess Santoshi, and Phulan devi , a product of the cult following enjoyed by the low-caste heroine of the 1980s, the "bandit queen" Phulan. The fasci-

nation with goddess figures and valiant women central to these stories is perennial in North India but has acquired new significance in a time of changing gender roles and expectations.

Also visible in recent additions to the Sangit literature is the impact of the official public culture of postcolonial India, which appropriates Hindu mythology and Sanskritic religious ideology in the service of politics. Dramas based on Sanskrit sources previously unknown to the Nautanki repertoire are appearing for the first time, such as the Sangit vir vikramaditya of the Shrikrishna akhara published in 1987. I suspect that the 1988-89 Doordarshan (Indian television) fifty-two-part serialization of the Ramayana , followed by the Mahabharata and Ramayana part two in 1989-90, will lead to a spate of new Nautanki plays based on the Hindu epics. The cycle of creativity and imitation continues to revolve, throwing up both novelty and reiteration of the old, in response to changes in public demand, whatever their origin.

Perspectives on Change

We can view the historical development of the Sangit literature over the last one hundred twenty years from several perspectives. We can first trace a geographic movement, beginning with the early texts published in Delhi, Meerut, and Banaras, followed by increased activity in Hathras and the Braj region, a shift eastward to Kanpur, and then a gradual extension outward to areas as distant as Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and eastern Bihar. This movement corresponds to the establishment of printing facilities in the areas where the Nautanki theatre attracted large public followings and achieved viable institutional structures. Its two foremost centers—Hathras and Kanpur—remain as active foci of publishing even though their performance traditions have faded away.

Despite their frequent shifts of locale and multiplicity of publishers, the format, content, and manner of distribution of Nautanki chapbooks have been consistent over time. This suggests a network of exchange and borrowing that is corroborated by the publishers' repeated attempts to reduce plagiarism. As a folklore genre disseminated through the print medium, the Nautanki literature exhibits a relatively standard form, enabling its ready recognition and separation from other popularly published genres. Whether such stabilization of the printed package has affected the performance text is a question of interest, but it lies beyond the scope of this research.

The evolution of akhara structures is another dimension of Nautanki

history illuminated by the examination of printed texts. Except for the first twenty or thirty years of its history, this folk theatre has been organized into lineagelike groups of poets and actors whose names, faces, and disciples are given on Sangit covers. The akhara connection serves here as a sort of advertising device. More significantly, the akhara provides cohesion among the performers, sustains the initiation and training of upcoming poets and singers, and supplies a mode of internal organization that is both affiliative and hierarchical. Identification by akhara is the chief criterion by which an aspiring poet establishes his legitimacy, much as adherence to a guru or gharana bestows credentials on adepts of other Indian systems of knowledge, as in music, dance, or spiritual practice.

The alliance to an akhara reinforces group identity in a situation where caste, religion, and geographical origin place few constraints on the participation of performers. The history of printed texts demonstrates that rivalry among akharas parallels rivalry among publishers, as a particular akhara tends to be published by a single publisher and publishers vie for steady contracts with leading poets. The elastic economic network generated in this process has no doubt contributed to the growth and expansion of the Nautanki tradition, enabling authors and publishers to benefit from commercial sales.

Within the covers of Sangit plays a wealth of narrative diversity meets the eye. What at first appears an inchoate mass reveals, to closer analysis by periods, the clear impress of historical change. As the nineteenth century slowly turns into the twentieth, the hoary saints and imaginary princes yield to heroes with firmer historical and regional identities. The old stories with their timeless universal themes continue to attract listeners, even as the appeal of contemporaneity consistently grows. By 1920 or so, everyday situations from various sections of modern life routinely appear, along with a sprinkling of English words appropriate to these contexts. The increasing realism present in folk theatre literature parallels the emergence of realistic conventions in the modern urban literatures in roughly the same period. However, in Nautanki narratives realism coexists with traditional elements; contemporary characters accumulate alongside the existing stock of fantastic, supernatural, and legendary figures rather than replace them or nullify their popularity.

The emergence of certain hero types within the contexts of colonialism and nationalism as well as changing conceptions of political authority will be our subject later, as will the connection between the folk

theatre and social reforms relating to the family, community, and women. At this point, let us summarize certain facts about the political circumstances of the time that bear on the interpretations that this chapter's textual history suggests. First, government censorship of published literature and of public performances was a political reality throughout the period, placing strict limitations on the expression of nationalist or anti-British sentiments. To convey political messages under such conditions, poets had to adopt covert strategies. The fictional, poetic, or dramatic representation of Indian historical figures vanquishing ruthless aliens was a common ploy. The apparent shortage of politically explicit Sangits, seen thus, likely masks the more widespread circulation of nationalist sentiments clearly visible in texts such as Sangit julmi dayar .

Second, the pressure on publishers and poets to "purify" their language, content, and performance practices was not only an echo of Hindu reform movements like the Arya Samaj but constituted an external form of state suppression, aimed at controlling any public exuberance that might acquire a volatile political character. Third, the geographic areas where Nautanki flourished were not early centers of Western-style education, nationalist activism, or religious reform. This fact was fortuitous in several senses, for until recently folk theatre has tended to disappear when "modernizing" forces become ascendant. The poets of Nautanki were by all indicators provincial but literate men who were not unaware of changes in the climate of ideas within their home regions. References to social and political reality in their plays may have become manifest somewhat later than they did in the consciousness of urban elites but probably before the new consciousness spread to illiterate laborers and the peasantry.