9—

In the Wild

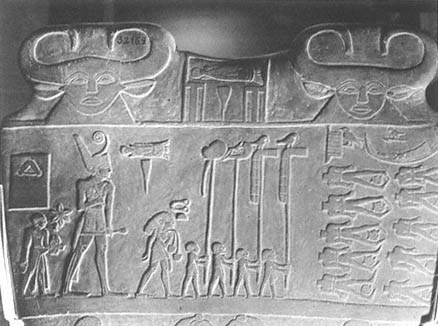

If the Narmer Palette (Fig. 38) is any guide, the radical revision of late prehistoric image making was not accomplished easily. We cannot suppose the maker already had in mind a full conception of a completely new symbolic image that would derive from but thoroughly revise and replace late prehistoric narrative images. Since the image maker could not yet know the later canonical tradition, he would have had to select from his own past tradition of late prehistoric image making, replicating his revisions in such a way that they ceased to be revisions and became the accepted way of making images. Moreover, we cannot suppose that his contemporary patron or larger audience had a new image in mind, demanding the new symbolic image on the Narmer Palette to match the reality of some new social and cultural formation that they had already determined to recognize and represent.

To the degree that representation constitutes the reality of the social and cultural formation, such apparently historical explanations for the creation of the Narmer Palette would be empty. They would imply that the new image was somehow literally produced elsewhere—for example, "in the heads" or "by the design" of fully foresighted image makers or contemporary patrons—and then, somehow, merely translated on the Narmer Palette. We cannot explain, or explain away, a new mode of representation or a new social and cultural formation apart from the image constructed on the object itself. The Narmer Palette is the very site of the appearance of the new image; it is the very theater in which the new scene of representation is being staged.

How, then, can we interpret the disjunctive properties of the Narmer Palette as replicating the existing tradition of late prehistoric representation?

Radical Positions in Continuous Replication

We should not overdramatize the historical problem posed by the Narmer Palette. It is only in double retrospect that the palette could have been regarded, and can now be regarded, as especially radical in its revision. Its decisive and influential qualities are constituted retrospectively both from its own vantage point, looking back over the history of late prehistoric representation before it, and from the vantage point of later image making, looking back over the history of representation including it.

For the first, the replicatory distance between Ostrich and Oxford Palettes (Figs. 25, 26), and between Oxford and Hunter's Palettes (Figs. 26, 28), Hunter's and Battlefield Palettes (Figs. 28, 33), and Battlefield and Narmer Palettes (Figs. 33, 38) is substantial in all cases. All these images are disjunctively related one to the next; in no case does the disjunction amount to a trivial or completely predictable difference, the ordinary by-product of repeating a motif. Rather, the disjunction is the symptom of metaphorical activity: in the chain of metaphors the ruler circles, enters, contests, and finally gains all the ground occupied, initially, by other identities as well—animals, human enemies, companions, followers, and even the viewer. No single advance is possible without the preceding ones, and none is necessarily greater than any other. In fact the "first" step, the Carnarvon handle (Fig. 23) or the Ostrich Palette, is perhaps more decisive than the "last," the Narmer Palette.

At any rate, we cannot find in a chain of replications the wholeness of any one replication, its significance or finality, apart from the chain as a whole. The seeming finality of Narmer's advance depends in part on cumulative advances made by the ruler through earlier images; whatever is radical in Narmer's image must be attributed in part to the narrative structure of the existing chain of replications. From this point of view the Narmer Palette is less a new hypothesis than an obvious and well-supported deduction, "radical" because, by the sheer seriality of the case, it happens to occupy the position of the Q.E.D. rather than the premise. To be more exact, neither premise nor conclusion is, in itself, radical or not radical; the decisiveness of the image in the continuous chain of

replications—the only way it can catch the viewer up—lies in the argumentation as a whole.

The status of the Narmer Palette as the climactic and radical revision of the chain of replications of late prehistoric image making is explained in part by the accident of its survival. There do exist fragments of what must have been other complex palettes datable by their sculptural technique and style to the same period as the Battlefield and Narmer Palettes—that is, to the Horizon A /B or early First Dynasty period. Some of these intriguing objects were quite as well made as the Narmer Palette. Among those that almost certainly presented sophisticated narrative and/or symbolic images are the Louvre Bull Palette (Fig. 37), the Cairo bird-and-boat palette (Petrie 1953: pl. B 4; Asselberghs 1961: fig. 159), the Cairo-Brooklyn Palette (Asselberghs 1961: fig. 181; Bothmer 1969–70; Needler 1984: no. 266; Davis 1989: fig. 6.13b), and the Libyan or Booty Palette (Fig. 53). Moreover, there are three early First Dynasty carved mace heads (Asselberghs 1961: figs. 172–80) that are in my opinion narrative/ symbolic images constructed according to many of the principles considered here, with some differences attributable to the different shape of the artifact itself, the roughly spherical head of a mace. One of them, the mace head of the so-called King Scorpion (Fig. 52), replicates—repeats, but also revises—the metaphorics of the Narmer Palette.

From the vantage point of later image making, in the same way the Narmer Palette became decisive because of the accumulating power, the compounding interest banking up in the chain of replications to which it belongs, its influence also derived from decisions of the later image makers who invested in it. After all, it was these later artisans, like the maker of the mace head of King Scorpion, who seem to have ceased making decorated palettes as such. This decision, in retrospect, gives the Narmer Palette a sense of finality it may not have had for its immediately contemporary maker and audience. Furthermore, later image makers determined to replicate some, but not all, of its narrative and symbolic elements, and, equally important, determined not to replicate other, "earlier" forms of late prehistoric narrativity hitherto available. These two decisions again conferred on the Narmer Palette qualities of preferability or

superiority it may not have had for its immediately contemporary maker and audience.

As all these arguments should imply, it is not self-evident that the Narmer Palette was, in fact, regarded as exclusively preferable, a decisive revision, despite the replication of its symbolic image within the canonical tradition. After all, later users also determined to preserve the Oxford Palette (Fig. 26) in the same archaeological deposit as the Narmer Palette, the Main Deposit at Hiera-konpolis, along with various other materials (Quibell and Green 1900–1901; Adams 1974). The survival of other major carved palettes, the Ostrich, Hunter's, and Battlefield Palettes (Figs. 25, 28, 33), was conceivably attributable to scrupulous preservation by contemporary and later owners, although in these instances we do not have specific archaeological provenances. (The Cairo-Brooklyn Palette [Needler 1984: no. 266; Davis 1989: fig. 6.13a] survived—whether through deliberate preservation or sheer luck we do not know—into the Eighteenth Dynasty and was recut by a sculptor in the reign of Amenhotep III.) It may be, then, that it is from our vantage point alone that the Narmer Palette seems radical—the "end" of late prehistoric representation, the "beginning" of canonical representation—because the full history of the modulation of replication, the pro-and retrospective construction of meaning for contemporary makers and audiences, is so out of good archaeological focus for us.

At the same time we recognize the Narmer Palette as completing a narrative consisting of many narrative images in a way that was selected for continued replication only by later viewers, we must still ask about the status of this already-radical, yet-to-be-radicalized revision that is the Narmer Palette itself. Why was this image produced, and under what conditions? After all, although its apparently radical qualities may result from pro-and retrospective con-ferrals of decisiveness and influence, those conferrals could not have been made if there was nothing they could "nominate for continued regard" (for this latter vocabulary, I am indebted to Levinson 1979, 1989). The text was produced—in all its proficiency or lack of proficiency and in all its backward- and forward-looking hesitancy and ambition—chasing or (as may be) eluding the meaning coming out of the past and out of the future to meet it.

Symptoms of Discomposure

Because we have no independent archaeological evidence for the conditions under which the Narmer Palette was produced, we will never achieve anything like the fine resolution we would need to answer all our questions satisfactorily. Moreover, as we have seen, an "archaeological" observation of the conditions of the production of a given individual replication would not tell us about the determination of that replication. Rather, the replication is produced as a spatial and temporal distribution of meaning, or nonmeaning, that eludes archaeological observation of the conditions at this or that particular place or time.

Nevertheless, in principle, the very fact that representation is produced in the pro- and retrospective construction and distribution of meaning—a metaphor, a narrative, a symbol, an image, a chain of replications—means that the image does contain its own archaeology. The image itself is a spatial and temporal structure with a history of construction. It looks back over itself; and others look it over. We can excavate this folding-over by recognizing that the work of representation necessarily exhibits a material stratigraphy. It displays a recoverable sequence and an apparent direction, an intentionality of making that cannot but reveal something of its determining conditions. The representation is simultaneously the disease and the symptom—although disease and symptom must be differently "placed" and "timed" in the making, in the artifact itself.

As we would expect if the conditions of its creation had a decisively radical effect on the chain of replications, the image on the Narmer Palette—an image spatially and temporally constructed in and distributed on an artifact—is shot through and through with symptomatic material. What we have already seen of the viewer's place in the scene of representation will demonstrate the point. The viewer twists the Narmer Palette in his or her hands to view the narrative of the ruler's blow (Figs. 42, 43), but the blow comes at the viewer in the other direction (Fig. 44); the viewer is caught up in it like one of the ruler's enemies. Upon "beginning" the narrative, however, the viewer had been invited to enter the scene beside the ruler (obverse top zone) or, more generally, to be like the

ruler: the viewer had been solicited by the organization of depiction, its placing of the viewer's "point of view" on the scene, to progress through and master the scene. The "ruler" of the scene continues to stand beside the viewer outside the depicted scene throughout the narrative; his presence outside the scene does not cease to be felt, and in fact the viewer outside the literal depiction, like the identities within it, comes progressively to see its power and danger.

To be specific, the viewer in the scene of representation is placed to the right. Initially (obverse top zone), the viewer looks "down" on the ten decapitated enemies and walks "beside" the ruler's retinue (on the ruler's right hand); and later (reverse bottom zone), the viewer—now constituted as and represented by the fleeing enemies—"looks over the (right) shoulder" at the ruler coming up behind. Indeed the viewer moves right hand over left in chasing the image and constructing the narrative (according to the cipher key presented in the obverse middle zone; Fig. 41). By contrast, the ruler of the scene of representation is placed, with the depicted ruler, to the left (obverse top and reverse middle zones) and moves left hand over right—that is, in a direction away from the viewer's twist (Fig. 44). Like the viewer initially well grounded on the obverse top zone, looking "down" on the ten decapitated enemies, the ruler of the scene is well grounded on the reverse of the palette. Here, in the reverse middle left zone, the sandal bearer carries his two sandals, facing toward the outside of the depiction and at the exact angle at which the ruler of the scene must be standing there, "beside" the viewer on his right-hand side.

If the viewer's action is to view the image, to chase the unfolding narrative by twisting the palette, then the action of the "ruler" outside the depiction is to make the image. He is—in part—the maker himself. Whereas the viewer's first action is to scan the completed depiction from top to bottom, the maker's first act is to draw the ground line from left to right on the blank surface, establishing the armature to guarantee the order of that depiction. Furthermore, whereas the viewer begins the progress through the narrative with the obverse of the palette, various internal clues—what I call the stratigraphy of the image—suggest that the maker's progress began with the reverse . In so doing the maker inverted the direction for viewing the image's story but accepted the primacy of the symbolic image to be precipitated from it. We can

describe the direction of the maker's intentionality as through the symbolic image toward the narrative—a reconstruction, then, of all late prehistoric narrativity by way of the symbol already cast up as its organizing metaphor (the smiting motif) and by way of the compositional format (the register band) long ago adopted, pried apart, and made the ground of the ruler. On the Narmer Palette the register line carrying the motif of the ruler smiting was drawn first, not last.

But in fact this was the first time the image maker had attempted such a thing and thus his work was uncertain, almost botched. In cutting the register line from left to right across the reverse side, the maker had not yet discovered that straight lines drawn across a slightly convex surface and therefore inserted in the edges in nonperpendicular fashion will not appear straight to the eye. The ground line on the reverse side looks lopsided because the maker failed to account for the curvature of the object. He corrected his mistake in the next register ground line drawn, below the top scene on the obverse. Establishing the ground of the ruler as the underlining and armature of the composition was not, in fact, a step the image maker could fully control or understand in all its implications: the ruler, as we will see in more detail, was only just beginning to enter the maker's ground in the scene of representation.[1]

With the armature of the ground lines in place, the maker then sketched the figures and began carving them in light relief, removing and smoothing the negative matter as he worked. Again we can see clearly that on each side he worked from left to right and top to bottom for each figure or group, his left hand holding the palette steady, turning it to the proper angle, and brushing away chips and dust as his right hand carried out the cutting. (For a right-handed engraver, this is, of course, the most natural and efficient procedure.) But working from top to bottom and left to right, he ran the risk of running out of space on the bottom right. Sure enough, at the right bottom corner of the reverse side, he failed to leave quite enough space for the left arm of the right-hand enemy figure, the last element to be produced (Fig. 46). He compensated by cutting back the figure's abdomen slightly and squeezing the arm partly behind the left leg. To make sure the arm would not appear to be lacking a hand, he then drew four fingers of the hand poking out on the other side of

Fig. 46.

Detail of Narmer Palette, reverse: fleeing enemies.

From Wildung 1981.

the leg. Noticing, in turn, that these might look like the genitals of the figure, he carefully added true genitals above them. He completely forgot, however, to return to the first enemy, already drawn on the left side, and add the corresponding genitals there. In revising his figures, the maker was clearly under pressure; and it led to an egregious error precisely in the place where the enemies look over their shoulders to see and acknowledge the ruler's blow coming at them (Fig. 44), or where, in general, the maker reversed the direction of his work—and perhaps its place in the entire chain of replications.

The passages of depiction above the ground line on the reverse side of the palette are, if not incorrect, at least ambiguous; it is not obvious how, as late prehistoric images, they should be divided into zones (left plus top right and middle, versus left plus middle and top right) or whether they should be divided into zones at all—that is, considered entirely within the conditions of intelligibility of the narrative image. Here too the ruler's blow breaks the composition apart. The decision to magnify Narmer's figure in relation to the other figures, and at a scale beyond anything attempted in late prehistoric representation so far, disturbs and arrests late prehistoric narrativity. From the vantage point of a viewer familiar with the general conditions of intelligibility of late prehistoric narrative on the Oxford, Hunter's, and Battlefield Palettes (Figs. 26, 28, 33), the static composition of the reverse side of the Narmer Palette (Fig. 45), with its heavy, lopsided ground line below and floating ground line coming partway in from the left edge, may have seemed clunky, even disorderly,

creating ugly blank spaces and alignments that do not quite seem to flow with the integration of the Oxford or Hunter compositions.

In sum, if we eschew looking at it through the lens of canonical art, the Narmer Palette is no more organized or composed than earlier images, with their clear differentiation and a mutual relatedness of pictorial zones we could pass smoothly between, like the intricate interlocking of pieces in a jigsaw puzzle. The revision of late prehistoric narrativity is not altogether confident and complete, not a correction so thorough that mistakes will cease to be visible and awkwardness avoided. Rather, the revision is, in advance, threatened and to an extent fragmented by the ruler's blow. The ruler's blow against the maker is already present in and as his revision of the image.

The Circumstance of Revision:

Looking at Himself Being Looked at Looking at His Work

Although viewer and maker are separate identities imagined as placed and divided from one another outside the depicted scene, they are the same actual person with two sides or faces—namely, the artist, whose positions as maker and viewer of the image are twisted together as a single identity in the continuous sequence of his work. To make the image he must view it, and to view the image he must make it. He is constantly exchanging one position for the other—coming around his hands with his gaze, coming around his gaze with his hands. And at the same time, he is looking over his shoulder—for another is gazing back at him and at the twists he accomplishes in and as his work. In looking at him looking at his work, this other—the ruler still outside the scene—causes him to twist himself to attend to the other's gaze. In all of this, then, revision becomes re-vision; the artist looks again at what he is doing, and, in looking again, he may not be looking with entirely the same eyes or even with his own eyes at all, for meanwhile he has been looking back to see how the other is looking at him and his work.

Like the figure of the right-hand enemy at the reverse bottom, other telling slips in the progress of his work are symptoms of the artist's double "two-sidedness," the fact that he must come around himself to make and view the work in front of him at the same time he must turn away from it to attend to

Fig. 47.

Detail of Narmer Palette, obverse: (left to right) sandal bearer, Narmer, scribe

priest, standard bearers, and ten decapitated enemies.

Photo courtesy of Werner Forman.

what is behind him. For example, to draw the ten decapitated enemies on the obverse top (Fig. 47), he needed to turn the palette (left hand coming around right) at right angles to the vertical orientation of the register ground lines. He placed the first small enemy figure in the top row against the side edge, the ground line. With his hands coming around his gaze and perhaps thinking of the enemies on the reverse bottom, he drew the enemy's feet both facing right. Doing exactly the same for the next enemy (that is, for the figure second from the left in the top row of enemies), with his gaze in turn coming around his hands, he recognized the compositional difficulty he was creating for himself. With the third enemy in from the left, he turned the two feet to face inward. In this passage his power as artist—his ability to take possession of making and viewing as an uninterrupted, undisturbed condition of replicating and

revising—seems to be confirmed even as the trace of the danger of discomposure persists. As artist, he seems to have escaped what he represented to be the case for his depicted subjects, for whereas the depicted enemies' arms are bound and their heads lopped off, the hand that drew them moved freely with the gaze, always taking control as the work threatened to go out of control. Here we can accept his "mistake" as a successful revision, suppressing a possible difficulty and even adding greater descriptive detail to this passage of depiction.

But when the maker must depict himself in the scene, the two-sidedness of his identity as an agent in control of his work and the fact that he is followed, or shadowed, by another catch him up in a twist. At the introduction to the narrative on the obverse top, the scribe-priest marches in the ruler's retinue in front of the ruler himself—or the ruler follows behind him—to inspect the ten decapitated enemies, the ruler's handiwork and, in the canonical form of the image, a metaphor for the palette itself. Slung over his left shoulder the scribe carries his two paint pots with the rope hanging down in front of his torso. One pot would contain red ink for a preliminary sketch of a text or pictorial composition or for making rubrics and the other black ink for its completion. Whether or not this figure depicts the maker of the Narmer Palette—we cannot confirm it literally—he represents scribes and artists, makers of pictures and texts.[2]

The real artist's interest in him is figured in the complex sequence of slips and revisions in the cutting. For one thing, the artist could not quite manage the two paint pots. They seem to hang impossibly in front of rather than beside or behind the figure, although the rope hangs down his torso and is clutched by his left arm in such a way that the pots could be carried only by being slung over the left shoulder. Here we might recover the mistake as an element of the image. For example, perhaps the descriptive function of this passage of depiction required the artist to inform his viewers of the person's occupation—and somehow he had to depict the paint pots otherwise out of view, like the lead bowman's quiver of arrows, slung over the shoulder, on the Hunter's Palette (Fig. 28).

Why not then do what the maker of the Hunter's Palette had done, and hang the paint pots properly over the right shoulder (on the viewer's left) and "behind" the figure? The maker's problem here is that working from left to

right he had obviously produced the figure's right arm and right shoulder already —with or without rope and pots; and working from left to right, he was forced into an awkward arrangement for the left shoulder: he had no choice but to place the paint pots "in front of" it. In fact the right arm, despite its failure, is a revision of an earlier attempt, cut over something else after the torso and left shoulder had been completed. The new right arm cuts off part of the old left hand. It seems likely, indeed, that the old right arm would have carried the rope and paint pots in proper orientation hanging behind the back. Why then revise the work by moving the rope and paint pots to the other side, the figure's left, and recutting his right arm to hang down rather than clutch the rope, as it probably did in the initial version?

The answer lies behind the figure even farther—that is, where the figure of the ruler is placed. Working from left to right, the artist had placed the scribe's back, right foot close to the forward, left foot of the ruler in the same way the ruler had been placed close to his sandal bearer following behind him at the left edge of the composition. But then it turned out that the figure carrying rope and paint pots over the right shoulder would be too close to the ruler's mace to be fitted in comfortably. Therefore, in what must have been the first revision in this sequence of recuttings, the scribe's back, right leg (on the viewer's left) had to be stretched out at just enough of an awkward angle to put him out of the ruler's way; the right leg angles up from the ground line with an extreme tilt. And then, in relation to the figure's excessively long right leg (on the viewer's left), his forward, left leg coming down to the ground line (on the viewer's right) would appear stumpy, like a peg leg protruding from his skirt—so the skirt is cut at an upward slant toward the front to provide room for a longer, "taller" forward leg matching the back one. Despite this effort the figure would still appear too stooped or lame, dragged backward by the paint pots; so the paint pots come around to the front, the left arm clutching the rope is produced, and the back, right arm, formerly clutching the rope holding the pots, is cut over again. Note, then, that at one point in the sequence of recuttings, the figure would be carrying two sets of paint pots, one over each shoulder.

By this point in his work of revision, the artist was unable to handle the right arm. He did not know which part of it to show himself or the

viewer—back, left side, right side, or front—and awkwardly revealed a little of each: precisely because the ruler comes up forcibly behind him, more of the maker now comes "into view" in the scene of representation.[3] The new right arm and hand—used by a right-handed artist, like the maker of the Narmer Palette, to wield the brush or hold the chisel—hang loose and useless; and its hand finally comes out as a peculiar upside-down version of the hands of enemies acknowledging the ruler (as on the reverse bottom zone of the palette and on the upright fleeing enemy on the Battlefield Palette [Fig. 331]). The left shoulder carrying the paint pots clutched by the left arm is completely twisted around itself. Everything becomes contorted or useless precisely because the artist attempted to revise the figure away from the ruler coming up close behind. There is no confidence in this effort; no full composure can result.

As a replication revising late prehistoric images, the Narmer Palette seems, on the evidence of its internal stratigraphy, to have been made under the very conditions it represents in narrative and symbol. It was made with the ruler just about to wield his blow standing beside and behind the maker, perhaps not literally over his shoulder but certainly close enough—sometimes too close for comfort. The ruler was close enough for the maker to turn his head away from the replication he was making, an activity determined by the history and the general conditions of intelligibility of late prehistoric representation, and toward the person of the ruler coming up behind him. He had to make room for the ruler, both in the image itself and in the making of it. Despite what the narrative and the symbolic images seem to say in their deliberated, literal presentations, the maker seems to have been caught partially unaware. He did not quite see the power and danger of the ruler, or right away; his corrections—of the entire tradition of replication, and of his own image as a deliberated correction of that tradition and of itself—revise him away from his failure to see and toward a greater recognition of the ruler.

The artist's knowledge must have come both pro-and retrospectively. Late prehistoric representation had implied that the ruler is decisively powerful and dangerous (Figs. 28, 33), but the maker could not know how much ground the ruler had gained until he looked over his own shoulder and found him standing there. The work, in other words, had to be hit by the very blow it narrates and symbolizes. The narrated or symbolic blows are only in representation, but the

Fig. 48.

Carved ivory label from Abydos, showing Den smiting

his enemy, First Dynasty. After Spencer 1980.

blow that hits them is real. It hit the maker himself as he composed the image, inevitably losing full control over the replication. The measure of proficiency, subtlety, and sophistication he and earlier makers had achieved in the ongoing elaboration of late prehistoric representation is noticeably disrupted, as if he had been almost pushed aside by the identity looking over his shoulder to inspect the representation of itself.

As a symptom of what it represents, the revision precipitated by the maker of the Narmer Palette could be selected for continued replication as a coherent symbol when other, later image makers, following his example, turned to face the ruler, now fully on this side, the viewer's and maker's side, of the text rather than on its reverse (Figs. 48–50). His revision is no longer uncomfortable, no longer the cause of discomposure or confusion, when later image makers no longer look over their shoulders—when they turn to work with the ruler directly in their field of view and as the frontal field of view. Discomposure will be reserved now entirely for the enemies of the ruler who do not see and acknowledge him (Figs. 51, 52). And with the ruler no longer beside or behind

Fig. 49.

Cliff relief from Wadi Maghara (Sinai), showing Sekhemkhet smiting his enemy

and standing in majesty, Third Dynasty. After Petrie 1896.

Fig. 50.

Cliff relief from Wadi Maghara (Sinai), showing Sanakht smiting his enemy,

Third Dynasty. After Gardiner and Cerny[*] 1952–55.

Fig. 51.

Limestone seated figure of Khasekhemuwy in majesty, with figures of his enemies incised

on the base (see Fig. 36), late Second Dynasty.

Courtesy Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

them, but rather in front, later image makers ceased to narrate the story of his sideways, oblique, and contested advance from the wild outside representation—off to the side, from the back—into the world they could represent. The representable world, directly before them, becomes the ruler. More exactly, it does not matter whether they look straight ahead or over their shoulders when in any case they must face the ruler who can still take them from behind.

Positions

The creation of the Narmer Palette as a replication of late prehistoric images could be described much more literally. I do not believe it is necessary, however,

or even fully desirable, to do so. There are some advantages, but many drawbacks, in trying to say how the ruler actually stood behind the artist or how the artist literally found himself looking over his shoulder. This holds good for the entire chain of replications; for earlier representations we could ask how, in a literal sense, the hunter edged into the natural world or how its ground was contested.

For example, we could say that on the evidence of its internal stratigraphy the Narmer Palette must have been made under the "direct, daily, personal" supervision of the ruler and his immediate entourage (Bourdieu 1977: 190), probably in the context of a political and cultural struggle for national domination (for various accounts, see Edwards 1972; Trigger 1983; and Kemp 1989: pt. 1). In this struggle the labor of artists, scribes, and others was highly valued, their intellectual loyalty sought, and their economic subordination desired (see also Davis 1989: 215–21); the objects or texts they made may have functioned literally as media of state propaganda (Hoffman 1979: 299) or other elite self-representation. According to an account of this kind, the "earlier" images in the chain of replications, by contrast, could have been made by independent craftsmen or craftsmen affiliated with local elites, either historically prior to or contemporary with the emergent state, whose attachment to traditional forms of late prehistoric representation continued to be strong. The upward social and economic mobility of certain artisans (Davis 1983b) and the dynastic ambitions of some elite patrons (Kaiser and Dreyer 1982) had a noticeable if somewhat confusing impact on contemporary image making whether or not makers or patrons intended it, introducing a series of changes into the chain of replications that, whether or not it was initially noticed and selected for further use, constitutes the measure of the revisionary, the "radical," in the Narmer Palette. Some such scenario, to the extent that it might be consistent with other evidence, could be erected on the basis of our findings about late prehistoric image making and its revision.

A literal account such as this might, in principle, give rise to an even finer-tuned account. For instance, the image maker's professional anxiety could become the subject of our historical analysis. On the one hand, the maker of the Narmer Palette seemed to want to replicate late prehistoric representation—that is, to produce a well-formed image according to established standards of

pictorial narrativity. On the other hand, he seemed to want to revise the replication to produce an image more directly attentive to the presence of his ruler, a symbol of the ruler's real substance. Desires like this make sense in a time of upward social mobility for some, but not all, craftsmen and artisans (Davis 1983b). A craftsman on the way up had to detach himself from primary agricultural production and most likely had to become a full-time specialist in a craft workshop. There were significant risks, including possibilities that the workshop would fall, the patron cease to provide, or the agricultural year offer too small a surplus to permit full-time specialization. Inevitably the craftsman's identification with the ruler's ambitions was an ambivalent one.

We might even see the image maker's own craft, the business of painting or sculpting pictures, undergoing swift change, challenge, and doubt in the late prehistoric period—whether it was practiced in a village or at a court, in small, part-time fashion or as a large-scale, full-time operation. The decades reviewed in this book, from about 3300 B.C . to about 3000 B.C ., see the emergence of hieroglyphic script (Schott 1950; Kaplony 1972; de Cénival 1982; Ray 1986; Baines 1989; Millet 1990), based, at least in part, on traditional practices of image making in rock art, pottery painting, and other media (see Arnett 1982). Although I do not focus systematically on this process and it has yet to be investigated in detail as a theoretical problem, we have encountered some of what I believe to be its most important aspects—namely, the use of "keys to the cipher" of iconic signs and the precipitation of standard replicable symbols from narrative pictorial images.[4] Did the image maker learn to read, affecting his replication and revision of images?—or was he one of the first writers of hieroglyphs to begin with? Was his status as maker of images and transmitter of knowledge threatened, or shored up, by the invention of script and the gradual creation of a semiliterate elite? What kind of stories could he continue to tell when a highly efficient mode of notation came into being? Did the very invention of a standard notation, readable under widely varying conditions and transmitted across the length and breadth of the state and as part of the growth of the state sector, make it more difficult to depend on the conditions of intelligibility of late prehistoric narrativity? To be able to answer such questions would be to provide a literal scenario of the image maker

looking over his shoulder at the ruler standing behind him—in the context of producing a representation masking the ruler's blow.

Although they need not be archaeologically implausible, if difficult to piece together, the methodological problems with such literal accounts should be obvious. A literal account might be consistent with archaeological evidence, but such consistency does not constitute explanation. For one thing, in its seemingly straightforward historical statements—based, in turn, on scrutiny of settlement patterns, burial data, and so forth—the literal account begs the hard question of cause and effect. It fails to say in what sense the images were the conditions for, or the results of, one or another element of the full scenario. For instance, in the example above, were some artisans upwardly mobile because they produced images satisfying the preexisting demands of an elite? Or was the success of the elite the result of their ability to persuade artists and other specialists to work for them? Even with the most finely resolved chronological knowledge of the sequence of events, these and other patterns of cause and effect will not be given in the historical evidence cited by any literal account; they will have to be inferred by the historian. The material evidence—which is simply a series of archaeological observations—needs to be narrated; and the narrating is the work of a historian observing patterns of relationship as well as occurrences of fact.

Despite its apparent seamlessness, its narrative drive, the literal story is full of doubts and gaps. Its status as the material account it purports to be is no more than possible at best. For instance, at least for the images under consideration here, archaeological evidence about their actual manufacture by independent regional versus court-affiliated national artists is completely lacking. A distinction of this kind must rely on "stylistic" differences among the works, in turn linked to a few debatable archaeological provenances (for example, see Davis 1989: 155–59 for "Delta" and "Upper Egyptian" styles in late prehistoric and early dynastic relief). But stylistic statements are only descriptions of sets of similarities among artifacts that are explained, by hypothesis, as having been caused by common descent from the same artifact "production system" (Davis 1990a). Thus a stylistic analysis does not allow us to make historical inferences but rather smuggles in a fundamental historical inference from the

beginning. The literal account might rely also on the internal stratigraphy of the images, rather than an independent archaeological record, to suggest possibilities of explanation. But, at least in the way I present it, that internal stratigraphy—although depending on numerous and minutely observed details—is not put forward as a literal history of anything but the material making of the object itself. As evidence for the determination of that material making in some actual context of "masking the blow," it serves as a general narrative of possible coherence and incoherence that must in turn be open to literalization when, or if, independent evidence becomes available.

Furthermore, whatever its measure of historical plausibility, the literal account is strictly limited by its own literalness, which might even be self-defeating. For example, it is always possible that we could secure some positive evidence about the social status of late prehistoric image makers and about particular patrons and viewers for whom their work was made. Taken as such, this evidence would not enable us to determine whether the internal stratigraphy of the images is symptomatic of the history of their production. Following the example of a literal scenario, an "independent" image maker—an artisan not affiliated with any court under the supervision of a powerful patron—could nevertheless be well aware of the possibility of a ruler "standing over his shoulder," and consequently he, like a court artist, would look back. Awareness of this kind might well be one element of his independence as defined in economic, social, or professional terms: to be independent is to be aware of what stands before or behind one. How does the literal account observe here what is, by definition, the imaginary or the symbolic in the real?

Taken too far—as it always must be if it aims to specify the "real" conditions of the production of images and the "actual" dimensions of the scene of representation—a literal account will confuse the cognitive "position" taken up, in the scene of representation, by a human subject in relation to the world and in relation to other representations of the world with real position—economic, social, professional, generational, family, ethnic, sexual, or other. If an artist represents himself in, or is represented as having, a certain economic, social, or other position, then, the account implies, he must really be in that position. By the logic of representation, however, the object depicted and the representing subject are divided from one another. Even in self-representation,

an artist looking at himself in order to represent himself is in a "position" that differs from the side or aspect of himself that has become his subject. To be able to represent being in a position or being represented as having one is already to show that the "real" material position from which the representations are made is partly outside those representations—that is, fully in the wild from the vantage point of identities within, and viewers of, the literal depictions as such. But that is not to say that they do not belong to the scene of representation.

Most worrying of all, in its sheer willingness to tell a story about what really occurred the literal account tends to exclude other possible literal accounts by other storytellers, then and now. Any and all of the positions someone has, including even the most transient "positions" taken up in irreducibly individual, nonconventional aspects of someone's form of life, are possibly relevant conditions of making representations. None can be ignored. The cognitive reality of any one of them in relation to its apparent presence in representation is a matter for investigation following upon, and in the context of, the archaeology of representation in replication.

For example, although certainly not usual in Egyptology or prehistoric archaeology, a literal tale of the maker's affiliation with the burgeoning state sector (as in Trigger 1983; compare Winter 1987) could be entirely rewritten in terms of some other "real" position, such as sexuality or ethnicity (for a provocative attempt, see Bersani and Dutoit 1986, with comments by Davis 1988). On the evidence of the temporal and spatial construction and stratigraphy of the images considered here, sexual, ethnic, community, and generational position certainly seem to be present in the late prehistoric Egyptian scene of representation. Thus the metaphorics that I explore in this book—the narratives of coming up behind, of seeing and being seen, of not-seeing and being destroyed—could be translated or rendered in literal scenarios as resistance and penetration, dominance and submission, ignorance and recognition, being inside and being outside, apartness and belonging, powerlessness and authority, and so forth, in every case assuming that the simple binary oppositions are metaphorically shaded and transformed in complex networks.

Some of these literal translations may be fully compatible with a historical account of the rise of state institutions and state ideology, perhaps even a necessary element in it. Some, however, might resist any such assimilation. And

why should we be forced to choose among them at all, settling, somehow, on the "real" or most basic scenario, the story of what is most compelling or determining in the last instance? For example, dominance of one actor's position over another's entails something specific (and possibly incompatible) in the two contexts, respectively, of real ethnic or racial diversity and real if sometimes unconscious sexual desire in a population. And these contexts cannot be separated: needless to say, ethnic or racial diversity and sexual desire can be the most literal or direct historical or social functions of one another. Thus we can only conclude that in fact the more general the account of "being dominant or being dominated"—or resisting and penetrating, ignoring and recognizing, and so forth—the less it will violate the realities of the world that a more literal, less inclusive account might reduce and obscure.

My account of the archaeology of replications "masking the blow" is, I hope, as open as possible to various, equally necessary literal accounts to be produced by historians with differing skills, knowledge, and interests—to the projections of all interpreters wanting to tell a story about the pastness of representation. To some extent this procedure is simply making a virtue of necessity, since we have no independent evidence for the real conditions of the production of late prehistoric Egyptian images. But I can see nothing intrinsically misleading or mistaken in that. Moreover, by no means does the general, open account have an easy pluralism, a free heterodoxy in its statements. For example, it has been quite tightly constrained by theoretical understandings of, and predictions about, intentionality, depiction, and narrative and their interrelations. Here it is not a virtue, if sometimes a necessity, to state matters in a broad way, for generality does not mean looseness; this framework establishes definite expectations for and limits on both the confirmability and coherence of historical interpretations.

Some historians would suggest that in the circumstances—we cannot know definitively what someone means or meant because we lack full evidence for it—we should say nothing. We would be instructed simply to give up making statements about late prehistoric Egyptian image making. Despite its appeal for those wishing to reserve their energies for what is supposedly secure and definite, I must reject this line of reasoning not only as the usual attempt to

hide "embarrassing questions" about "the place of history and the ultimate ground of narrative and textual production" (Jameson 1981: 32) but also as an abdication of the most literal-minded historical responsibility. In fact, it is an avoidance of the historical project as such. We can never know definitively what anyone means or meant because, by definition, meaning is not open to archaeological or historical observation at this or that time or place.

The hope for a fully general and open interpretation is an analytic ideal that cannot be completely realized in practice. My account of late prehistoric representation and of the Narmer Palette—which some readers must consider overly metaphorical—necessarily literalizes in all kinds of ways. For example, I want to relate the visual (or optical) and the physical (or manual) conditions of figures within the image and of the identities making and viewing it—the place and position of eyes and bodies. But in describing these eyes and bodies as "positions," it is difficult not to fall back into literalization, into a story about "real eyes," which cannot possibly look in both directions at once, and "real bodies," which cannot possibly twist around themselves. It is sometimes necessary, therefore, to maintain descriptions of seeing, viewing, holding, or moving the image or the object between quotation marks. That statements must be thus rhetorical and that the object of study is, itself, a metaphor whose translation is unknown may not be directly relevant in producing a general, nonliteral account—for the general account is about this figurative condition, or the conditions of figuration, in the first place.

The literal existence of some real condition of seeing, viewing, holding, or moving the image or the object is not in great doubt for any human being who could look at images or handle objects. Thus it can be a basic fact entered in any literal chronicle about the scene of representation. A "flipping" of the palette may well be a metaphor for a material scenario about someone's real eyes and bodies still or perhaps never to be specified. But for the purposes of analysis it serves us well enough as one material or metaphorical, particular or general ground, the ground of the eyes and the body, on which further complex metaphors could be propped—extending the optical and the physical into other spheres, such as the economic, social, professional, ethnic, generational, or sexual. As a point of interpretive theory, we may call the position of eyes and body the metaphor,

the "construction," of "real" positions—economic, social, or other. As a point of analytic method, however, we have to say just the opposite. Because the literal reality of some condition of the eyes and the body is not in doubt, it can become the grounds for a general account open to other literalizations in which the material connection between representation and the form of life is, indeed, in considerable doubt.

Always Outside

If the identity outside the literal depiction on the Narmer Palette is simultaneously the maker and the viewer—that is, the artist—then these are positions not only of the actual artist of the work, whoever he or she might have been, but also of the real ruler. Looking over his shoulder to take note of the ruler standing behind him as he produced the representation of the ruler coming up behind his enemy, the artist—along with the figures he drew—is the ruler's representative in the scene of representation. Other works of the early First Dynasty, while fragmentary, seem to advance a literal depiction of the ruler as maker into the depicted scene; his identity as the one who sees had already been well established by the chain of replications (Figs. 25, 26, 28, 33, 38).

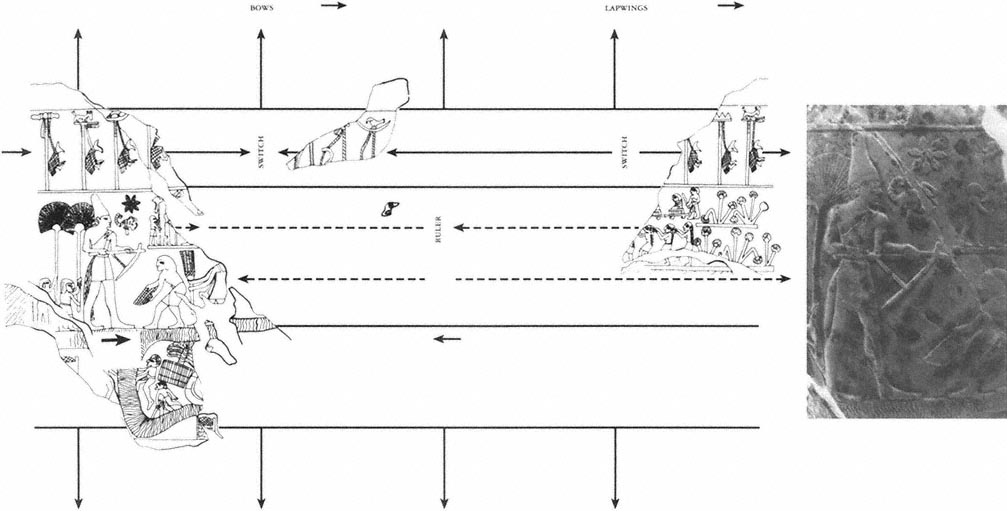

In the image on the carved mace head of the so-called King Scorpion (Fig. 52), probably to be dated roughly to the time of Narmer, the ruler makes the fields of Egypt and, extending the depiction into the metaphorical domain, presumably Egypt's abundance and prosperity as well. The figure of Scorpion is singled out, first, by his size—he is the tallest in the composition; second, by the "royal" rosette and scorpion sign in front of his face, apparently the only such label in the composition; and third, by a narrative device we cannot be surprised to discover, considering how other images in the chain of replications have been put together. The wide band of depiction running around the middle portion of the mace head is divided internally into two (and at points three) stacked registers. The only exception is the figure of Scorpion, facing to the right in the surviving piece of the mace head, who spans the entire band from top to bottom. In the top register of the remaining piece of the central band, figures are oriented as moving away from Scorpion, and in the bottom, as

moving toward him. The switch in direction—where figures moving away must be coming together and figures moving toward must be proceeding outward—is undoubtedly made on exactly the other side of the mace head, in a passage of depiction that can be viewed only when the viewer is not viewing the figure of the ruler opposite it.

But what should appear in this other, exactly opposite position—predictably behind or on the other side—but another figure of the ruler? Although the mace head is almost completely missing for this segment of the image, a surviving fragment of a rosette emblem (not the same as the one used to label the ruler in the main surviving piece of the object) indicates that Scorpion was probably depicted here as well. Presumably facing to the left, he must have been engaged in an activity involving the women of the household, being carried toward him (one carrier and two women have survived), as well as rejoicing women (four surviving figures are visible) and advancing retainers with standards (three surviving figures are visible).

If this interpretation is correct, the portion of the image that survives on the mace head is the "other side" of the "opening" of the visual text—or, more accurately, the depictions of the ruler on both sides of the mace head are the "opening" of a pictorial narrative text, viewable in both directions, of which the ruler opposite is on the other side. In viewing this image by turning the mace head, the two depictions of the ruler are also the "middle" point reached on the two strips of the central band wrapped around the object. Starting with one ruler, we pass by the other ruler in the process of turning the mace head all the way around to the beginning again. In the top band of the image, above the figure of each ruler, the standards with hanging elements—lapwings (possibly the hieroglyph for the people of Egypt) and bows (perhaps the "nine bows" that later symbolize the foreign enemies of Egypt)—face in the direction the ruler is facing. Thus the lapwings hanging from standards by ropes strung around their necks make a switch in direction, with the birds replaced by hanging bows (and vice versa), precisely—in the most plausible restoration I offer here—between the points where the two rulers are placed.

In the portion of the image that survives, Scorpion wields a hoe, the same implement used elsewhere in early dynastic image making to depict the breach-

Fig. 52.

Mace head of King Scorpion: carved limestone mace head from Main Deposit at Hierakonpolis, early First Dynasty. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Detail of principal

figure of King Scorpion (photo courtesy Ashmolean Museum, Oxford); line drawing of surviving surfaces (corrected after Smith 1965) and suggested structure of the image.

ing of enemy fortresses (see Fig. 53, right). Here he is cutting an irrigation canal, indicated along the bottom register of the central band by a channel of water that forms the ground line for his figure and those of several others. Two bearers approach "from the right" to stand before him, preparing to sweep up and carry off the dirt.[5] Two fan bearers come up behind him "from the left" (possibly emerging from the building depicted behind them, according to a recent restoration; Millet 1990: 59) to shade him from the sun. The ruler has the White Crown of Upper Egypt, the tunic, and the tail he wears on the Narmer Palette (Fig. 38); the locality seems to be specified as Papyrus Land.

In the register below the ruler's ground line and to the right (that is, coming into view from the right if the mace head is turned around left behind right), the ruler's sacred bark—only its prow visible—sails on the river, coming from the direction of the scenes now completely lost. Thus as the mace head is turned around to the left, moving "to the right" away from the figure of the ruler, the boat "sails toward" the viewer. (Since the boat presumably bears the ruler, as one figure of the ruler disappears from view, it is as if the other figure—on the other side of the palette—is being transported into view; as always, the narrative is in the motion.) In its progress the boat will pass by or between two cultivated plots. The right-hand plot in the preserved portion of the image is inhabited by a hoeing farmer, below, and another man, above, who seems to thrust his hands into the river. The left-hand plot, now badly damaged, probably contained the same two men; the top figure, thrusting his hands into the water, is still preserved. All these characters may be defeated, bearded enemies of the ruler put to work or settled on the land. Although it is not possible to understand the arrangement of the lower register, it seems that it was divided by the waterlines, and possibly other devices, into at least two and probably more episodes concerning the life of the countryside. The figures seem to be repeated from one zone to the next, as is a round-topped building. The register was probably arranged to establish a series of "befores" and "afters," or of preconditions and consequences, of the ruler's actions as they appear in the central band above it.

In sum, the image as a whole—top band, internally divided central band, and bottom band—divides into two principal movements, separated in the

central band by the register line that runs around the middle of the mace head. The two movements always go in opposite directions as far as we can tell from any single view of the image stretched around the mace head. When the top portion of the image is moving away from Scorpion "to the right," the bottom portion is moving toward him "to the left," and when the top portion is moving away from him "to the left," the bottom portion is moving toward him "to the right." The two figures of Scorpion, opposite one another in the image and each oriented in reverse direction from the other, span these two movements, whose "switch" is not visible when either figure of the ruler is being viewed. Thus, as in the other images in the chain of replications, the ruler is always outside, coming around and behind that which faces toward him and that which faces away from him. This much of the general structure of the image is clear. Unfortunately its metaphorical and narrative content remains obscure; because only about one-third of the whole has survived, we cannot say how the several episodes fitted together.[6]

As the awkward drawing of Scorpion's hands and forearms suggests (there may be substantial recutting here), the artist struggled to position the main handle of the ruler's hoe almost exactly parallel with the ground line. This formal relation in the text of the image is crucial in the general metaphorics. It is the ground line itself that is wielded by the king, produced by him from the land of Egypt and—in continuing or "shooting out" from the hoe and around the mace as the viewer turns it—supporting the register of his rejoicing retainers and standards. The ruler makes the very order that canonical representation finds in the world.

This order is presented also in both early dynastic and canonical image making, as that which the ruler possesses as his estate (Figs. 1, 2). The Libyan or Booty Palette fragment (Fig. 53) preserves roughly the bottom third or half of an image perhaps derived from late prehistoric images as an independent symbol of their metaphorics of the ruler's victory, and now probably of state rule. A missing top register on one side (top )—we cannot tell obverse from reverse because the cosmetic saucer is absent—might be restored as prisoners being marched to the right by the ruler's retainers (for example, like the scene on the Beirut Palette fragment [Asselberghs 1961: fig. 183; Davis 1989:

Fig. 53.

Libyan or Booty Palette: carved schist cosmetic palette,

early First Dynasty. Courtesy Cairo Museum.

fig. 6. 12]); remains of human feet are visible at the edge of the break. Although a figure of the ruler might be restored in this register, he would presumably have to be placed in the center or on the left side so as not to violate the general organization of late prehistoric images, in which the ruler and the ruler's representatives never face "out" of the scene but are always coming into it. All the figures on the palette, however, should probably be "read towards the left in accordance with the orientation of Egyptian writing" (Terrace and Fischer 1970: 21). As we would expect, then, considering the replicatory revisions of the Narmer Palette, this palette exemplifies an emerging canonical revision of the order of late prehistoric image making.

Below this passage of depiction, whatever it presented, fortified cities—inside each, town-name hieroglyphs accompany small rectangles apparently indicating buildings—are breached by representatives of the ruler, including a falcon (top row) and a lion, a scorpion, and falcons on standards (bottom row). In its metaphorics the scene is related, on the one hand, to the image of ruler-as-bull breaking down the enemy citadel on the Narmer Palette (Fig. 38) and, on the other, to the ruler-as-wielder-of-the-hoe, as "maker" of Egypt, on the mace head of King Scorpion (Fig. 52).

On the other side of the palette (bottom ) three registers of animals survive—from top to bottom, bull oxen, donkeys, and rams, all males of their species. The image on this side might originally have included another register or two in the missing piece. There are four beasts in each surviving row of animals, with the exception of the last. The creatures are usually interpreted as booty taken by the ruler from plundered towns in the "olive-tree land" symbolized by the olive trees and "Tjehenu" sign (= western delta, Libya) in the bottom zone on this side of the palette (Vandier 1952: 592). Like the animal-rows motifs produced much earlier in the chain of replications, but separated from them by the complex set of disjunctions we have surveyed, the animals march along ground lines drawn from one edge of the scene to the other, eliminating, as they go, the possibility of a sideline or another ground for humankind and nature. This image has "tamed the unruly mob of the early palettes (although it seems to have robbed every creature of some of its mysterious potency)" (Groenewegen-Frankfort 1951: 20).

Only the young ram at the end of the line in the bottom row—observed last if the image is viewed like hieroglyphic writing from right to left—turns back its head to look outside the depicted scene it inhabits as the king's estate. This figure reminds us (would any contemporary viewer have remembered?) of one of the commonest devices of late prehistoric image making—namely, the creature pursued by what it does or does not see about to catch up with it. But what could be behind this ram but a register line, the continuous, endless ground of the ruler? Or does the register line wrap around the palette—where in fact it disappears in this position—and the ram gaze back into a wild place where the register line cannot be found? The ambiguity is surely inherent and unresolved. The maker of the palette, standing in line facing the ruler like everything and everyone else, did not absolutely intend or fully anticipate how his ram would function. He simply ran out of space toward the bottom of the tapering palette and was forced to squeeze one figure in by drastically scaling down and shortening its body and turning its head back. And yet this slip, or resistance, of the maker plotting the ground figures some possibility of wildness within the unalterable armature of canonical representation. It constitutes as possible the continued presence, for canonical Egyptian art, of the late prehistoric scene of representation that is now literally behind and completely outside it.

The possibility of wildness is only that, for the actual person of the ruler of Egypt is still outside the scene of representation and in the canonical tradition will never be within it. His "real" appearance outside—as much as his represented appearance within—the literal depiction masks the way he continues to stand beside and behind. He is merely represented by that apparently real body with its composing blow of canonical figuration—that is, by the person, action, and gaze of the artist. The ruler himself, as ruler of the entire scene of representation, remains outside. He continues to designate how he will be seen—namely, precisely as the source of the representation he appears to inhabit from any angle or from all directions and about whom such a representation is naturally made. The artist who, as the representative of the ruler, enters a representation that depicts the king entering an unseeing nature can be nothing more than another nature entered by the ruler. The artist is "nature" carried to

the second power, or to as many powers as might be nested within one another; the artist is part of the scene of representation as it is always framed by a final, absolute power outside it. That power is absolute in the world it attempts to guarantee by putting forward this very representation of it. The ruler remains beyond representation—masks his own blow—until his wildness can be entered as a nature by one who has his or her own place outside the ruler's representations.

Disjunctive as it is, a movement has been completed—a series that has taken us through images none of which can stand alone (or as a whole, a beginning or an ending), each subsisting only in terms of what is behind and outside it. From the Oxford Palette (Fig. 26) to the Narmer Palette (Fig. 38)—a temporal and spatial slice of the chain of replications—the deadly forces of humanity and nature have completely traded places, shifted ground, twisted about, absorbed into each other, and advanced from outside to inside and inside to outside. Throughout, the ruler—father, hunter, matriarch, warrior, king—is forever in advantage by the very fact of being behind, the only one to approach always obliquely behind a mask with the other always failing to see him there. Unseeing nature, which cannot represent, does not design a place for the ruler; the ruler designs a place for it—that is what defines him as a ruler, absolute within the temporary reign of uncontested representation.

On the Oxford Palette the wild dogs face one another and clasp paws, while below them the masked hunter stands near the sidelines playing his flute. On the Narmer Palette the heraldic cows turn outward to face the one who looks at the entire scene: the ruler himself, never literally depicted in the scene of his mastery but only figured there as the condition of its composition. And within the depicted scene, at right angles to the person viewing him as his or her self, his represented natural double—the figure of the ruler smiting his enemy—has exchanged his mask and flute for crown and mace.