Pronghorn, Cattle, and Feral Horse Use of Wetland and Upland Habitats[1]

Hal Salwasser and Karen Shimamoto[2]

Abstract.—Developed wetlands play a critical role in habitat quality for pronghorn, domestic cattle, and feral horses in Great Basin range-types. Wetlands provide abundant summer forage for pronghorn when cattle and horse grazing has removed coarse grasslike plants, making forbs available. Wetland creation should be balanced with needs for existing habitats on ranges.

Introduction

The Modoc Wetlands study began in October 1976 as a cooperative effort by the USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region, Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, and Modoc National Forest; the California Department of Fish and Game, Region 1; and the Department of Forestry and Resoure Management, University of California, Berkeley. Local assistance and cooperation were also provided by the USDA Soil Conservation Service, USDA Fish and Wildlife Service Modoc National Wildlife Refuge, and the University of California Cooperative Agricultural Extension. The overall study goal was to assess the population responses of selected wildlife species to wetlands developments on the Devil's Garden plateau of the Modoc National Forest. Study efforts focused on pronghorn antelope (Antilocapraamericana ), sage grouse (Centrocercusurophasianus ), puddle ducks (Anatidae), Canada goose (Brantacanadensis ), mule deer (Odocoileushemionus ), other wetland birds, domestic livestock, and feral horses.

Wetland development began on the Modoc National Forest in the 1920s, initially for runoff storage within Pit River Valley irrigation districts. Damming of major drainages, such as Rattlesnake Creek to create Big Reservoir, was the early mode of altering hydrologic patterns. Subsequently, over a period of 50 years, lesser drainages and internally drained basins were modified for irrigation, livestock forage, and wildlife purposes. An obvious result of these actions was that existing vegetation cover-types, dominated by big sagebrush (Artemisiatridentata ), low sagebrush (A . arbuscula ), silver sagebrush (A . cana ), western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis ), and riparian-associated willows (Salix spp.) and herbaceous vegetation, were converted to wetlands characterized by varying proportions of open water and hydrophytic plants; e.g., spike-rush (Eleocharispalustris ), rushes (Juncus spp.) and a diverse flora of vernal forbs.

The effects of these ecosystem changes on wildlife populations have been the subject of much speculation. With the proposed and actual development of new wetlands in identified pronghorn and sage grouse habitat in the 1970s (Modoc National Forest Wetlands Development Plan), the issue of impacts on these and other wildlife species became a major concern to land managers. This study was initiated to assess those impacts. In addition, the issue of livestock and feral horse use of wetlands as factors in waterfowl, pronghorn, and sage grouse population dynamics was incorporated into the study.

Field investigations and literature studies dealt with four principal questions.

1. What are the characteristics of existing wildlife and livestock habitats?

2. How are wildlife, livestock, and feral horses currently utilizing and interacting with existing plant communities and with each other?

3. How do wetland development and management change the characteristics of plant communities and animal use of those communities?

4. How are pronghorn, sage grouse, waterfowl, mule deer, and other wetland birds responding to these changes and management strategies?

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] Hal Salwasser is Regional Wildlife Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region, San Francisco, Calif. Karen Shimamoto is Forest Ecologist, Modoc National Forest, Alturas, Calif. Research reported in this paper was conducted while both authors were Research Associates at the University of California, Berkeley.

This paper reports on the use and preference of wetlands and surrounding upland habitats by pronghorn, cattle, and feral horses during the summers of 1978–1979.

Study Area

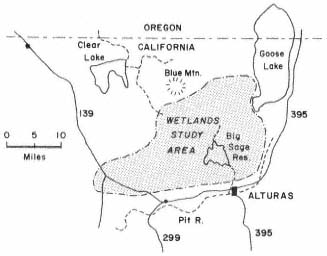

Sampling on the entire area of the Modoc National Forest affected by wetland development was not within personnel and budget capabilities of this study. Therefore, a study area on the Devil's Garden Ranger District, covering roughly one-third of the Devil's Garden Plateau, was selected (fig. 1). The study area encompassed approximately 145,749 ha. (360,000 acres), and included all cover-types within which forest wetlands are being developed. Elevations range from 1,320 m. (4,400 ft.) to 1,680 m. (5,500 ft.). Terrain is generally flat and marked by numerous rimrocks and small block faults.

Figure l.

Location of the Modoc Wetlands Study.

Soils in the study area are derived from basaltic lava flows, mud flows, and wind-blown ash. Alluvial soils are common in the numerous basins. Vegetation, fauna, and climate of the study area are all typical of the Great Basin environment. In fact, the area lies on the western margin of the Great Basin geomorphic province within what would be a natural extension of the Basin and Range Physiographic Province of southern Oregon (Franklin and Dyrness 1973). Young etal . (1977) placed it within the Great Basin Floristic Province.

Precipitation ranges from 51 to 610 mm. (2 to 24 in.) per year, averaging 305 to 356 mm. (12 to 14 in.). Extreme high or low precipitation years are more common than are "normal" years. Winter snow is the main source of precipitation. The frost-free growing season is 80 to 100 days.

Cover-types are described in detail by Salwasser and Shimamoto (in prep.). The bulk of the study area, 69.6%, was in Juniper/Sagebrush and Low Sagebrush cover-types (table 1). These two types were highly intermixed, but occurred in sizable distinct patches as well. Dense Juniper stands and the ecotonal Juniper/Pine/Shrub cover-types comprised 12.1% of the area. Ponderosa pine, which covered 5.3% of the area, was common on the northern and western fringes of the area. Remaining uplands were minor components.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Basins and wetlands in the study area were dominated by three types: Reservoir/Lake, Silver Sagebrush, and Emergent Wetland. There are 23 reservoirs, ranging in size from less than 4 ha. (10 ac.) to over 2,429 ha. (6,000 ac.). Seventy-four percent of the reservoirs are 8.1 ha. (20 ac.) to 81 ha. (200 ac.) in size. The 276 Silver Sagebrush basins ranged in size from .4 to 259 ha. (1 to 640 ac.). However, 96% of them were under 16 ha. (40 ac.). The 57 Emergent Wetlands ranged from .4 to 1,134 ha. (1 to 2,800 ac.); 81% of these were in the under 32-ha. (80-ac.) category. Thus, there are only a few very large reservoirs, silver sagebrush basins or emergent wetlands on the study area. This results in a fairly good distribution of smaller basin and wetland sites over the whole area. Eighty-three percent of all basin and wetland sites are less than 16 ha. (40 ac.) in size.

As a result of the upland conversions to wetlands, over 1,619 ha. (4,000 ac.) of Emergent Wetlands and Vernal Wetlands have been created. This has most certainly diversified the mosaic of cover-types on the study area.

The loss of riparian vegetation has been largely mitigated by enhancement of streamside vegetation due to more consistent water flows from the reservoirs. All riparian areas continue to be heavily grazed by cattle.

The area of Low Sagebrush and Juniper/Sagebrush lost to wetlands conversion is insignificant as a portion of the total area. We did not attempt an exact estimate of this loss, but it certainly amounts to less than 10% of the original area. While the size of the area affected by these changes is not significant, and not likely to ever become so, there is a distinct possibility that key pronghorn or sage grouse habitat areas could be lost through inundation.

Methods

Fixed-wing and helicopter flights were used to census the animals: eight fixed-wing flights in 1978 and two in 1979, and five helicopter flights in 1979. Flights began at daybreak, usually between 06:00 and 07:00. Flights were made at approximately 190 kph (120 mph), 60 m. (200 ft.) above the ground, on north to south transects 0.8 to 1.61 km. (0.5 to 1 mi.) apart. Helicopter flights were made at 160 kph (100 mph), 150 m. (500 ft.) above the ground, on transects 3.2 to 4.8 km. (2 to 3 mi.) apart. All flights had two observers who recorded the number of animals seen, the cover-type, and location.

No attempt has been made to adjust data for differing observability of animals in different habitats. Habitat use is the number of animals observed in each cover-type as a proportion of the total number observed on each flight. Habitat preference is estimated by the index:

This yields PI values that range from –1 to 1. When habitats are used in proportion to availability, PI = 0. PI values greater than zero imply preference while values less than zero imply lack of preference.

Results

Wetlands

Developed wetlands were extremely important habitats to all three animals considered in the study. Use and preference for wetlands increased toward mid-summer with a peak depending on annual water conditions. In 1978, pronghorn use of wetlands peaked at 80% (PI = .86) on August 9 and remained over 40% through October 11; in 1979, use peaked at 71% (PI = .85) on September 14, after having exceeded 50% since August 31. Horse use peaked at 78% (PI = .86) on July 11 and remained over 40% through August 9 in 1978, and at 49% (PI = .78) on July 19 in 1979. Cattle use in 1978 peaked at 80% (PI = .86) on August 9 after exceeding 50% since June 22, and at 85% (PI = .87) in 1979 on September 28 after exceeding 54% since May 22. Both pronghorn and horse exhibited a definite peak in wetland use in mid- to late summer; cattle use exceeded 50% of all observations from mid-June in both 1978 and 1979.

Emergent wetland vegetation, spikerush, and a diverse understory of succulent forbs was highly preferred for forage. Pronghorn appeared to lag about two weeks behind cattle and horses in using wetlands, perhaps needing the larger herbivores to remove coarse, grasslike forage and make forbs accessible.

Silver Sagebrush

Silver Sagebrush basins were also important to all three mammals. They were the first cover-type containing wetland forbs to dry each summer. Their use and preference preceded wetlands by two to four weeks. All three animals maintained a relativly high preference for Silver Sagebrush throughout the summer. Pronghorn use peaked at 23% on June 22 and 24% on July 25 (PI = .77) in 1978, and at 48% (PI = .88) on June 22 and 35% (PI = .84) on July 19 in 1979. Horse use peaked at 35% (PI = .84) on June 22, 1978, and at 44% (PI = .87) on May 25, 1979; cattle use never exceeded 31% of observations, but preference was high throughout the summer of both years.

Low Sagebrush

Low Sagebrush was used in the spring and early summer while its grasses and forbs were succulent. It was very important to pronghorn: 37% to 84% of all observations from April 27 to July 25, 1978 (PI = .11 to .48), and 19% to 66% of all observations from May 25 to August 31, 1979 (PI = .21 to .39). Horses and cattle used the Low Sagebrush type much less than its availability throughout the summer in both years; it is probably important in spring.

Juniper/Sagebrush

The Juniper/Sagebrush type was not a preferred summer habitat by any of the three animals. Only horses showed a slight positive PI on two flights. We suspect horses may use the cover-type for thermal cover on hot, sunny days. It could also be an important winter thermal cover habitat for horses.

Discussion

Pronghorn vary their use and preference of habitat-types. Low Sagebrush is important in spring while forbs are palatable. As soils dry, Silver Sagebrush basins are preferred and may be especially important during drought or low-forage years, as in 1979. As wetland waters recede and horses and livestock remove coarse forage, pronghorn move to the drawdown zone. Wetlands appear to provide a significant source of green forage when uplands are dry. We believe wetlands must be drawn down and grazed by cattle to have maximum forage value to pronghorn.

Horses also vary their habitat use and preference, their pattern being similar to pronghorn. They do appear to rely on the Juniper cover-type more than pronghorn do.

Cattle prefer wetlands and Silver Sagebrush for summer grazing. They use Low Sagebrush when first put on the range, but rapidly move to the wetter sites. The presence of wetlands on a grazing allotment may relieve uplands of excessive use, and thus allow a natural improvement in condition.

It must be noted that all observations were made during the feeding period. Animals probably use habitats differently for resting cover during summer midday.

Conclusions

A variety of cover-types offering cover (thermal and security), seasonal forage, and water are used by large herbivores. Each cover-type appears to play a significant role for each animal. While wetlands are highly preferred, they are most often created by converting a Silver Sagebrush basin which itself is important to the animal in early summer. Land managers should try to achieve a representative balance among all possible habitats within allotments or wildlife home ranges. This study shows that a variety of cover-types may be a key to range capacity and condition.

Literature Cited

Franklin, Jerry F., and C.T. Dyrness. 1973. Natural vegetation of Oregon and Washington. USDA Forest Service GTR-PNW-8. 417 p. Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, Portland, Oregon.

Salwasser, Hal, and Karen Shimamoto. In preparation. Modoc wetlands study: final report. University of California, Berkeley.

Young, James A., Raymond A. Evans, and Jack Major. 1977. Sagebrush Steppe. In : M. A. Barbour and J. Major (ed.). Terrestrial vegetation of California. 1002 p. John A. Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.