Disorders of Cardiac Conduction

The process of conduting impulses through the heart can be disturbed in three ways: (1) by a delay at a given point, (2) by its total interruption somewhere along the pathway, and (3) by nonresponsiveness of some part of the pathway.

Abnormal delay in conduction usually occurs between the atria and the ventricles, presumably because something slows the transit of the impulses through the A-V node. Such a delay is shown in the electrocardiogram by the fact that the interval between the P wave and the QRS complex is prolonged beyond the normal 0.2 seconds. This phenomenon is called first-degree heart block or first-degree A-V block (fig. 26b). First-degree heart block does not disturb the rhythm or the rate of the heart. It is primarily detected by the electrocardiograph. Its importance lies in demonstrating that the patient's conducting system is imperfect, and it may precede more serious forms of conduction disturbances.

A higher degree of impairment of conduction between the atria and the ventricles is a second-degree heart (A-V ) block , a condition in which a certain number of impulses from the atria never reach the ventricle (figure 26c). Thus, one out of every two or more impulses from the atria is lost, producing dropped beats. The result may be an irregular heart action (if dropped beats occur every third beat or more) or a regular rhythm (if every other beat is dropped, two-to-one heart block ).

The next level of disturbance of atrioventricular conduction is its total interruption, third-degree heart (A-V ) block , also called complete heart (A-V ) block . Here the atria and the ventricles act entirely independently of each other: the atria contract as a result of the normal S-A mechanism; the ventricles contract as a result of a

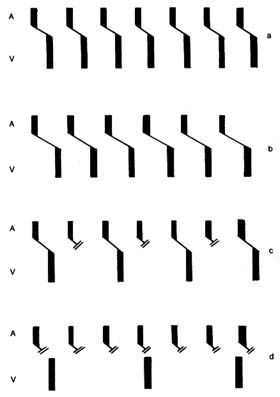

Figure 26. Diagram showing the sequence of beats under normal conditions

and in various forms of heart block. The upper bar (A) represents atrial

depolarization, the lower bar (V) ventricular depolarization. The

oblique line joining the 2 bars is the atrioventricular conduction.

|

ventricular pacemaker with a slow rhythm unrelated to the atrial activity (fig. 26d). In complete heart block the atria usually maintain the normal heart rate of 70 beats a minute; the ventricles beat only 30 to 40 times a minute. This unusually slow ventricular rate imposes obvious problems on the maintenance of the circulation. In an otherwise sound heart the circulation can be maintained reasonably well, especially if the patient's activities are restricted; in the presence of serious heart disease such a low rate may precipitate heart failure. However, the principal danger of complete heart block lies in the fact that the ventricular pacemaker constitutes the last line of defense: its failure leaves the heart without any impulses, hence without contraction. Such failure of the ventricular pacemaker occasionally occurs in complete heart block for short periods (less than two minutes), causing loss of consciousness, and is known as cardiac syncope or Stokes-Adams attack . The danger of such an attack is self-evident: if it lasts more than four minutes, the patient will die.

The three degrees of heart block may be temporary or permanent. Temporary heart block may be due to acute, reversible illness, to the action of drugs, or to nervous influences; permanence implies complete, organic destruction of a given part of the conduction pathway.

If the interruption of conduction pathways occurs in the section below where the bundle of His divides into two branches, the impulse reaches the ventricle through the healthy bundle, so that the rhythm of the heart is not disturbed. However, if one of the ventricles fails to receive the impulses directly from the conduction pathways and the other ventricle is activated via a detour, the second ventricle contracts with a slight delay. This delay does not necessarily affect the function of the heart, but it causes gross distortion of the electrocardiogram. This type of conduction defect is called bundle-branch block (right or left, depending on which bundle is damaged). Bundle-branch block is a common disorder in some forms of heart disease, particularly in diseases of the coronary arteries.

Disturbances of the conduction system due to nonresponsiveness of the conducting tissues has already been touched on in connection with atrial flutter and fibrillation, in which not all rapid impulses can reach the ventricles. Other conditions in this category include atrioventricular dissociation , a disorder in which the A-V

node fires at an abnormally high speed, faster than the S-A node, and therefore takes priority in activating the ventricles. Nonresponsiveness of conducting pathways may separate these impulses from the atria, which obey the normal S-A node stimulation. This situation resembles complete heart block in that the atria and the ventricles beat independently of each other, although here, by contrast, the atrial rate is usually slower than the ventricular rate. Such conditions are almost always temporary, usually do not last long, and often reflect the influence of factors outside the heart (drugs or a disturbance of salt and water metabolism).