4

The Segregated City

Chicago 1870-1920: factories, railroads, and skyscrapers

Motorists Speeding Along the New York Thruway, their glance drawn for a moment by a fragment of stonework from an old Erie Canal lock, may find it hard to see in such small constructions the fateful determination of their own lives, but the artifacts of the second period of industrialization present no such problems of self-recognition. We live among the objects of that age—its railroad stations and yards still stand near the center of town, its rows of warehouses and factories line many of the main streets of any city old enough to have grown up in those years. Its luxury apartments, when still maintained, are widely sought after for their old-fashioned charm and spaciousness, its houses of the well-to-do are the objects of neighborhood defense against destruction by urban renewal, while its parks, boulevards, office towers, and public buildings are often the only monuments to civic pride and luxury in our cities. These structures among which we live are but symbols of our more meaningful ties to this former time. Its manufacturing belts have coalesced into our megalopolises, and many of its business institutions are today's largest corporations. The archetypal city of this era was the industrial metropolis—the city of the mechanized factory, the business corporation, the downtown office, and the segregated neighborhood.

In technological terms the progression from the first era of industrialization (1820-70) to the second (1870-1920) can be characterized as a giant leap forward in power, speed, energy, and adaptability. The

complex machine ceased to be an innovation and became ubiquitous. The period actually opened in 1863 in France with the invention of the Siemens-Martin open-hearth method of high-quality steelmaking, and in 1865 with the introduction of cheap Bessemer steel production in Troy, New York. With the abundance of steels came all the elaboration of engineering that distinguished the times—high-speed rails, massive bridges and viaducts, skyscrapers, battleships, and finally automobiles. Mastery of the technology of electricity made possible the application of energy in measured quantities wherever it was needed, a boon denied to the operators of the cumbersome pulleys, shafts, and belts in the preceding days when power was generated by steam and waterwheels. Now electricity could run an individual streetcar or light a lamp in one room as easily as it could illuminate a skyscraper; it could pull a mammoth assembly line or drive a single sewing machine. Moreover, electric power could be transmitted hundreds of miles from its source, thereby allowing manufacturing plants to seek their best transportation, labor, service, and sales locations rather than clinging to waterpower sites. Explorations taking place in the field of chemistry made possible the refining of petroleum, the manufacture of dyes and high explosives, and the compounding of new alloys. The repeated economic successes of technological innovations led to the institutionalization of invention itself, so that firms regularly set aside money for the specific task of discovering new tools, products, processes, and modes of transmitting energy.[1]

The ubiquity of power and machines in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had profound effects on the American urban system. First the new technics encouraged urbanization in general by drawing more and more Americans into those economic roles which peculiarly favored the growth of cities. Mechanization of agriculture, mining, and lumbering freed a multitude of workers for alternative tasks in manufacturing, transport, finance, and the servicing of business. So successful were the new modes of factory production in saving manpower that in the fifty years after 1870 the ratio of Americans employed in marketing, transportation, and services, the very specialties of cities, grew more rapidly than the ratio of those in manufacturing itself.[2]

[1] . Jacob Schmookler, Invention and Economic Growth , Cambridge, 1966, pp. 199-209; Melvin Kranzberg and Carroll W. Pursell, Jr., Technology in Western Civilization , I, New York, 1967, pp. 357, 563-692.

[2] . Harvey S. Perloff et al., Regions, Resources, and Economic Growth , Baltimore, 1960, pp. 131, 151-61, 168.

Second, the functions of cities within the national urban network shifted. The largest cities diversified, becoming great manufacturing centers as well as places of commerce and finance. At the same time, small cities which specialized either in manufacturing a narrow line of goods or in processing regional products for the national market multiplied and prospered. These growing small cities were not, however, evenly distributed across the nation but were concentrated in the Northeast and Midwest. Because the new electrical and automobile technology built upon the skills and tools of the old iron and steam technology, the cities of these two industrialized regions stood in a favored position for making the components of the new age.[3]

Even the crudest classification of the nation's cities by size of population reveals the new trends (Table 1, page 70). Industrial diversification spurred the growth of metropolises. The 1920 national network of cities was composed of twenty-five metropolises ranging in size from New York (5,620,000) to Denver (256,000).[4] Moreover, the sizes of the cities reflected their economic diversification. The giants, New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia, were the largest manufacturing clusters in the nation in which every kind of product came forth, from the earliest mechanized goods like textiles, clothing, flour, and meat to the most modern like structural steels, petroleum, electrical machinery, and automobile parts. So powerful had been metropolitan growth that two of the twenty-five metropolises, Newark and Jersey City, were themselves adjuncts to the metropolitan district of New York. The smallest metropolises, on the other hand, added a few manufacturing specialties to the traditional regional commercial activities. Rochester concentrated on men's clothing, boots and shoes, foundries and machine shops, furniture, and optical instruments; Portland (Oregon) on lumber, foundries and machine shops, and wooden shipbuilding; Denver on railroad-car building and repair, foundries and machine shops, and slaughtering and meat packing.[5]

[3] . Beverly Duncan and Stanley Lieberson, Metropolis and Region in Transition , Beverly Hills, 1970, pp. 119-34.

[4] . The twenty-five metropolises of 1920 were: New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis, Boston, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, Buffalo, San Francisco, Milwaukee, Washington, Newark, Cincinnati, New Orleans, Minneapolis, Kansas City (Missouri), Seattle, Indianapolis, Jersey City, Rochester, Portland (Oregon), and Denver. Fourteenth Census of the U.S.: 1920 , I, Population , Washington, 1921, p. 80.

[5] . Fourteenth Census of the U.S.: 1920 , IX, Manufactures, 1919 , Washington, 1923, pp. 163-64, 1089-90, 1256.

Below the largest cities came an efflorescence of smaller ones, 263 in all. Of these, 69 were classified by the statisticians of the Fourteenth Census as sections enveloped within metropolitan districts.[6] However one divides them, into 25 metropolises and 263 cities or into 23 metropolitan districts and 194 independent cities, the difference between the two groups was a matter of the degree of specialization of economic function in the urban system.

The smaller cities were all specialists, but of two distinct kinds. One variety, processing and commercial cities, fulfilled the classic urban role of rendering financial and commercial services to its rural hinterland, bringing the goods of the nation to the farms and towns of its surrounding area. In return these cities processed and shipped the local specialties into the stream of the national and international market. Memphis handled Southern lumber and made oil from cottonseed, Tampa manufactured cigars from Cuban tobacco, Richmond made cigarettes, Sacramento canned fruits and vegetables, Tulsa refined petroleum, and E1 Paso, Houston, and Fort Worth built and maintained railroad cars and equipment which carried the Texas farmers' crops and livestock. In the Midwest and Northeast a second variety of small city flourished—the mill town. Here specialties were not based directly on local farms or natural resources but rather capitalized on local skills and the regional and national markets for producers and consumers goods. Albany concentrated on shirts, nearby Troy on collars; Bridgeport on corsets, brass, and machine tools; New Bedford and Fall River on cotton textiles; Elizabeth, New Jersey, on electrical machinery; Chester, Pennsylvania, on iron and steel; Allentown, Pennsylvania, on silk goods; Erie, Pennsylvania, on foundries; Columbus, Ohio, on railroad cars; Dayton on machine tools and cash registers; Toledo on glass, foundries, and auto parts; and Youngstown on steel.[7] The clustering of these specialized cities created the two manufacturing belts of the nation. One belt stretched along the Atlantic coast all the way from Maine to Virginia; the other lay west of the Alleghenies and north of the Ohio, stretching from Pittsburgh and Buffalo on the east to St. Louis and Milwaukee to the west.

It was the railroad that allowed the metropolises to diversify and the

[6] . Fourteenth Census , I, Population , pp. 62-75.

[7] . City specializations taken from listing by city in the Fourteenth Census , IX, Manufactures .

small cities to specialize, because it created the national and large regional markets for both groups of cities. These were the years when almost all of the nation's internal traffic moved by rail. In 1916 (ironically the year in which federal aid was first granted to highways) the nation's rail network reached its apogee: 254,000 miles of tracks, 77 percent of the intercity freight tonnage, 98 percent of the intercity passengers.[8]

Urban economic diversification and specialization both stemmed from the way the railroad customarily handled its freight. Freight cars were made into long trains at the terminals in the largest cities and were then dispatched to another metropolitan center at a distance, with only limited stops for the purpose of adding or dropping cars or taking on more locomotives to climb the Appalachian range, which separated the two manufacturing belts. In these long hauls the railroad reached its maximum efficiency, its lowest costs per mile. A skeleton crew could handle the moving train, whereas the terminal yards required many more men to assemble and reassemble freight cars. Thus starting and stopping were very costly, but the extended hauls saved on fuel. Influenced by these factors as well as by a desire to increase the volume of traffic on long lines through the lightly settled South and West, the railroads offered low rates for those long-haul commodities which were specialties of any given region in the United States—oranges from Florida, lettuce from California, strawberries from Louisiana, copper from Montana, lumber from Idaho.[9]

Furthermore, as the railroads delivered farm products and national resources to the freight-yard and terminal cities, they conferred upon the metropolises choice locations for expansion in wholesale and retail manufacturing. Accordingly, next to the urban terminals sprang up enormous breweries, refineries, steel mills, or meat-packing concerns. Brewing and meat packing, as well as milling, had formerly been among the dispersed processing activities, yet now they clustered together at the terminals in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Kansas City and St. Louis, Chicago, Toledo, and Buffalo. The shipping advantages enjoyed by the

[8] . John F. Stover, American Railroads , Chicago, 1961, p. 269.

[9] . Benjamin Chinitz, Freight and the Metropolis , Cambridge, 1960, pp. 110-28; David M. Potter, "The Historical Development of Eastern-Southern Freight Rate Relationships," and Stuart Daggett, "Interregional Freight Rates and the Pacific Coast," Law and Contemporary Problems , 12 (Summer 1947), 416-48, 600-620.

important terminal points likewise aided existing city industries like printing and clothing manufacture.[10]

The rail-terminal metropolises did not monopolize all the urban growth of the era; rather they formed symbiotic relationships with networks of specialized small cities, thereby allowing these cities to expand on the basis of their particular advantages. The specialized cities were in part the outgrowth of industries based on cheap resources: Manchester, New Hampshire, had long since grown up around waterpower, as had Trenton, though Trenton had access to coal and iron as well. Peoria was a new city that lived by distilling the nearby corn. Some carried old skills into the new electrical and auto age, as was the case in Providence with its machine tools or Waterbury with its brass. But these settlements, whether oriented toward natural resources or toward skills from their pasts, were all sustained and nourished by the interlacing rails that ran through the Northeast and Midwest.

The nation's coal trade also favored the Northeastern and Midwestern manufacturing belts. Coal far outweighed any other freight movement along the railroads. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, coal had to be shipped from the mines of Appalachia, southern Illinois, and Missouri to the cities of the East and Midwest: huge tonnages to heat and light the cities, to make gas for cooking and lighting, to power the factories, to melt the iron, and to serve as the base for chemicals. To keep the fuel moving smoothly, the railroads had to build city terminals and extra trackage along the coal routes. This heavy investment in transportation capacity for coal set in motion a positive cycle of railroad investment, low freight rates, and high industrial investment; since the rail capacity had been justified by coal, it could be used as well for other freight. Thus, low rates and good terminal service could be offered by the railroads in these two regions which the South, Mountain, and Pacific regions could not hope to duplicate.[11]

Finally, competition policed the rate structure of the railroads of the East and Midwest. City rivalries during the years 1840 to 1860 had led Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and others to build rail systems. When completed and interconnected after the Civil War, they offered more than one path to many destinations; the shipper could

[10] . There was much contemporary objection to the rate-making advantages of the rail-terminal cities and already industrialized regions. See, for example, Charles Horton Cooley, "The Theory of Transportation," Publications of the American Economic Association , 9 (May 1894), 113-23.

[11] . Edward L. Ullman, American Commodity Flow , Seattle, 1957, pp. 1-19.

often choose his railroad. Cutthroat competition ensued, only to be halted by agreements among the railroad corporations themselves during the 1870s and 1880s. The corporations set standardized fares within the Northeast and Midwest that ignored precise distances and thereby eliminated slight mileage advantages of one city over another. Federal regulations confirmed these agreements until truck competition made them impossible to maintain in the 1930s.[12] For the half century of its duration this standardized rate structure of the railroads was a stimulus to intra-area traffic. So too was the fact that the volume of freight was so immense in the two lanes of greatest traffic—the Atlantic coast and the land west of the Alleghenies—that lines within these regions could add a certain amount of business without incurring the expense of additional facilities.

Thus the transportation lines and the economy grew together, the easy intercommunication among the industrial metropolises and the specialized small cities fostering the manufacture and marketing of ever more complex products. With good rail service, the lines of complementarities among firms that used to prevail only in the neighborhoods of the old big city now could be enjoyed throughout the manufacturing belts of the Northeast and Midwest. Steel could be ordered from Pittsburgh, Buffalo, Detroit, or Chicago for subway cars being built in New Hampshire, ships being built in Wilmington, generators being built in Schenectady, or harvesters being built in Milwaukee. Likewise the many parts and subassemblies for all these products could be gathered from the crisscross traffic of the regions. Though the long hauls were always the cheapest per mile, the sheer volume and frequency of such traffic, as well as the competition among the lines, kept rates down and service up, and fostered the growth of the two sprawling manufacturing belts, made up of many small cities and linked together by giant industrial metropolises. Half a century ago the railroads were laying the foundation for two of the megalopolises of our own time.

As the completed rail system extended the scope of urban markets so that all manner of products from precut beef to stone crushers could be sold nationally, the mechanized method of production came forward to take advantage of the profits to be reaped by large-scale endeavor. Thus the increase in the size of business enterprises so painfully begun

[12] . Pittsburgh Regional Planning Association, Economic Study of the Pittsburgh Region , I, Region in Transition , Pittsburgh, 1963, pp. 188-202.

in the earlier period continued unabated. The trend toward bigness was most dramatic among the specialized cities where giant mills concentrated on a narrow range of products. The average number of employees per manufacturing establishment exceeded a thousand in such places as Lawrence's worsted mills, New Bedford's cotton mills, Omaha's slaughterhouses, Providence's machine-tool factories, Oakland's shipyards, Milwaukee's engine plants, and Racine's farm-machinery works.

In the industrial metropolis trends were more selective, with considerable variation among cities and industries. New York and Chicago differed in scale of enterprise (Table 2) partly because New York's industrial structure had taken shape in the earlier era of small shops. Here the presence of subcontractors and small specialists discouraged the concentration of every aspect of the manufacture of a product under one roof; firms could achieve large-scale production by taking advantage of the complementary suppliers in the city. On the other hand Chicago—the new industrial metropolis, the rail center of the Midwest, and the center of a vast wholesale trade—organized around large firms and long production runs. Thus its firms, even in old industries like boots and shoes, clothing, furniture, and hardware and hand tools, were larger than New York's. In both cities, however, new industries like electrical machinery, refrigerated dressed meat, rubber products, paper and wooden boxes, steel ships, railroad cars, and steel mills showed the effects of large markets, heavy capitalization, and expensive machinery (Table 2). For such enterprises, firms of hundreds and even thousands of employees became commonplace.

The new scale of business forced a reorganization of urban business institutions. The private corporation replaced the gathering of hundreds of proprietors and partners that had characterized the former big city. As this transformation proceeded, the power of deciding what urban working conditions would be like and where urban jobs would be placed shifted from an unmanageable army of small entrepreneurs to a clearly identifiable group of corporate managers. By 1920 a planned national economy and a nation of planned cities became a possibility open to Americans.

The private corporation in the United States had its roots in the necessity for amassing capital for large undertakings. In the years from 1820 to 1870, when corporations were still a novelty, private groups had sought charters for such institutions in order to construct bridges,

TABLE 2 . |

|

[13] . The purpose of Table 2 is to give illustrations of changes in manufacturing establishment size in a number of representative industries. The industries listed stand for varying degrees of removal from primary processing of resources to complex multistage products which are manufactured either for consumers or for other producers. Some industries were selected because they have a long continuous history, like clothing, flour milling, hardware, and tobacco, and others were selected because they were peculiar to an era, like railroad cars or aircraft.

The verbal descriptions of each industrial group in the table were taken from the 1919 Census of Manufactures, and an analogous 1967 Standard Industrial Classification group was sought to match. For 1870, vaguer approximations had to be tolerated. The 1870 equivalents for the 1920 descriptions were: boxes, cigar, paper, wooden and fancy (1870) for boxes, paper (1920); drugs and chemicals for chemicals; machinery not specified, engines and boilers for foundries and machine shops; iron forged and rolled for iron and steel works; lumber planed and sawed and sashes, doors, and blinds for lumber and planing mills; shipbuilding and repairing for shipbuilding, steel. The killing of animals for shipment as dressed fresh meat was not an industry in 1870, so the packing of salt pork and beef had to be taken as the equivalent of the entire meat-packing industry of 1919.

The city boundaries are in 1870 Cook County, Kings and New York County, Los Angeles County; in 1920 the cities themselves; in 1967 the Chicago Consolidated Statistical Area, the New York Consolidated Statistical Area, and the Los Angeles-Long Beach Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Anaheim-Santa Ana-Garden Grove Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Ninth Census: 1870 , III, Statistics of Wealth and Industry in the United States , Washington, 1872, pp. 639, 649, 701-704; Fourteenth Census , IX, Manufactures , pp. 122-26, 358-64, 1058-66; Census of Manufactures, 1967 , III, Area Statistics, Parts I & II , Table 6.

canals, turnpikes, and railroads, to establish banks, and to engage in some manufacturing.[14] These firms had a common need to raise large amounts of capital. The corporate form, with its legal devices of stock and bonds and limited liability of stockholders for the debts of the business, facilitated a wide canvass for capital. Under the contemporary partnership form of business, every partner was personally liable for the debts of the entire firm, and many a nineteenth-century businessman lost his savings and his home upon failure or from a partner's incompetence or fraud. Under the corporate form, large merchants and small investors, total strangers to each other, could club together in the confidence that each risked only his investment, not his fortune, his home, or his farm.

Although the corporate charters required a governing board elected by the stockholders, the early corporations were so small that they were not in fact managed by committees but by one or two men. The success of these firms depended on the ability of the managers to stay in contact with all aspects of the business in order to coordinate diverse activities and to direct the firm into new undertakings. As the size and complexity of American enterprises increased, however, business management passed beyond the reach of any one man's personal supervision. First with the trunk-line railroads of the 1850s, and then increasingly in production of food products, sewing machines, and farm machinery in the

[14] . George H. Evans, Jr., Business Incorporations in the U.S. 1800-1943 , New York, 1948, pp. 10-30.

1880s, American corporations experimented with new forms of management. By the first decades of the twentieth century a centralized, departmentalized, bureaucratic form of corporate management had been established as the norm for big companies.

No sinister force withered the strength of the personal-style managers, but the increase in the size and complexity of their responsibilities overwhelmed them. In the 1850s a textile company might employ some eight hundred men, a locomotive works six hundred, but the Erie Railroad had four thousand employees, men not confined to one yard but scattered over five hundred miles of track. No one office handled the cash; hundreds of station agents and conductors took in the company's money. By the 1880s the major trunk-line railroads like the Pennsylvania had several thousand miles of track and upwards of fifty thousand employees. Nor was mere size the extent of the manager's problems. These were times of rapid technological change in railroad construction and locomotive and car design, and times of fierce competition. The manager could not hide his head in routine but had to make quick competitive decisions, perhaps whether to merge with minor roads or to cut rates in order to capture more traffic. It was a time too when unscrupulous financiers maneuvered the stocks and bonds of the railroads to found individual empires, so that many a firm was harassed to the point of destruction by external and internal security manipulation.[15]

The absolute necessity for dependable coordination of the management of daily business and the simultaneous need to meet the competition transformed the early trunk-line railroad into a modern centralized corporation. The Erie, the Baltimore and Ohio, and the Pennsylvania were all pioneers in bureaucratic innovation; between 1850 and 1880 they established the fundamental structure of the American corporation. Railroad management divided naturally into three departments—finance, operations, and traffic—each with distinct responsibilities and chains of command. Finance concerned itself with the collection and dispersal of revenues as well as with the issuance of stocks and bonds; operations controlled the movement of trains and their maintenance; while traffic was essentially a sales department, finding customers and following the course of their goods and freight

[15] . Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Railroads, the Nation's First Big Business , New York, 1965, pp. 97-100; and Chandler, Strategy and Structure, Chapters in the History of the Industrial Enterprise , Cambridge, 1962, p. 38.

cars, as well as watching the costs of passenger and freight movement. Throughout this first stage of corporate development the emphasis was on centralized control, because the highest profits were found to accrue through consolidating unrelated commitments into one comprehensive undertaking.

Therefore each department and each section within it had both line and staff officers. The line officer managed day-to-day operations within his section and might deal with the movement of cars, the routine repair of a segment of a trunk line, or the disbursement and collection of funds in a given geographical area. The staff officers reported directly to the central office. They were charged with the responsibility for long-range decisions, such as whether or not to purchase new rolling stock or to establish new traffic patterns. This departmental management of a centralized bureaucracy made possible the successful operation of the great railroad complexes of the period. It also made possible the coordination of hundreds of small lines, originally built by the cities and towns, into far-flung, high-speed routes traveled by thousands of cars, which were unscrambled and rerouted in a thousand different ways on their trips into the city terminals.

The same opportunities and challenges that had organized the railroads manifested themselves a few years later in industries attempting to reach and hold a national market for their products: meat, cigarettes, flour, bananas, harvesters, sewing machines, and typewriters.[16] Problems might arise in sales, production, or supply, but since they had their origin in the grandiose scale of the enterprise, the solution was everywhere the same—toward rationalized departments in management, toward centralization of control. Gustavus Swift (1839-1903), a cattle buyer and shipper, who financed the development of the railroad refrigerator in order to sell meat butchered in Chicago in Eastern cities, found his business requirements driving him from a partnership to a modern corporation. Once he had perfected his car, he needed sales offices and refrigerated warehouses at his major-destinations; he had to finance his fleet of refrigerator cars and struggle with the railroads to obtain fast service for them; and finally he had somehow to connect the purchasing and slaughtering of animals in Chicago to his sales in the East. Aided by a centralized departmental structure and by staff and line control over his operations, Swift was able to build a national business.

[16] . Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., "The Beginnings of 'Big Business' in American Industry," Business History Review , 33 (Spring 1959), 6.

He overcame consumer reluctance by national advertising and expanded into related lines of pork, veal, lamb, butter, oleomargarine, soap, glue, and fertilizer. He was eventually able even to shift to multiple plant locations (Fort Worth, Omaha, St. Joseph, St. Louis) that brought processing closer to the sources of his supplies.[17]

The necessity for management to control sales throughout many cities and possibly also throughout a number of supply locations spread the new bureaucratic corporate structure to cigarettes, flour, bananas, sewing machines, harvesters, and lighting and power utilities.

Corporate centralization also appeared in the rubber companies and in many metalworking industries during the late nineteenth century. To take full advantage of the new technology required heavy investments in machinery housed in factories capable of a tremendous volume of steady production. The consolidated plants were of course immensely more efficient than the previous small factories, but they did require a new approach to sales; the sales force had henceforth to be under the control of management as well as subservient to production. The independent salesman who worked on a commission had dominated American marketing during the nineteenth century, and his success depended on selling a few products at a high commission rather than on selling a great many at a low commission. The route to harnessing the market to the output of the giant factory henceforth lay in the adoption of national advertising to arouse consumer demand and of salaried salesmen and sales managers to close the deals, and this route proved to be the way around the old independent salesman.

Still other industries, like steel and oil, expanded in the direction of controlling their sources of supply so that production would not be at the mercy of outside forces. In almost every industry the forces for centralization, for the integration of sales, supply, and production, pressed upon owners and managers of American business, and everywhere the response took the same general direction toward vertical integration, departmental structure, staff and line responsibilities, and centralized control. The progression was always an uneven one, and some giants like U.S. Steel remained a muddle of centralized operations and semiautonomous subsidiary corporations until the 1930s. The notorious Standard Oil Corporation never attained in these years the rationalization achieved by American Tobacco or General Electric.

[17] . Oscar E. Anderson, Jr., Refrigeration in America , Princeton, 1953, pp. 50-52, 142-50; Chandler, "Beginnings of 'Big Business,'" 6-8.

Whatever the degree of formal rationalization, however, the impersonal centralized private corporation was an outstanding social fact of the era, and from it spread the ever-widening bureaucratization of American work and society.[18]

The reorganization of business institutions to suit the demands and possibilities of large-scale enterprise brought about a chain of adaptations within the cities themselves. Immense factories became normal manufacturing elements. There arose the rubber plants of Akron, the glassworks of Toledo, the cotton mills of Manchester in New Hampshire, the cash-register factory at Dayton, and together they overwhelmed the specialized minor cities of the manufacturing belts. Such factories with their ferocious rationalization were apt metaphors for the new metropolis itself, which experienced a similar heartless rationalization of its jobs and its land use. Exploitation and segregation were the dominant trends within the cities of this era. The similarities between the mechanized centralized enterprise and the industrial metropolis of the half century after 1870 were entirely apparent to their contemporaries. As the science and engineering of the time had supplied the expertise for developing products and processes, so the emerging social science uncovered the framework of the economy and the city and suggested sensible guidelines for their humanization. Indeed, the two most typical cities of the period, Pittsburgh and Chicago, were the ones in which investigators carried on the most advanced research and reached the most perceptive conclusions concerning the interconnections of the national economy, corporate enterprise, urban jobs, and urban land-use structure.

The Industrial Metropolis: 1870-1920

In Pittsburgh a team of investigators spent most of a year in 1907-1908 probing into every aspect of the city. Their goal was to relate the systematic knowledge of census and survey to the reportage of individual lives and experiences. Their hope was to arouse local action directed toward the improvement of living conditions. The reports were masterpieces in social science and journalism. The six volumes ultimately published served as the foundation for urban social science during the next twenty or thirty years, and they are still the richest

[18] . Chandler, Strategy and Structure , pp. 24-41.

available source of concrete information on the urban life of these times.[19]

The repetitive theme of the Pittsburgh Survey emphasizes the driving force of the age. It explored the centralized, rationalized, carefully planned engineering controlled by vast enterprises; the furnaces and rolling mills, railroads, mines, and ovens all interlocked in a wonderfully productive unity supported by armies of men and thousands of machines and fully able to move mountains of material over half a continent. From 1880 to 1910 an industrial metropolis based on steel, glass, and electrical machinery had sprung up from the conjunction of almost unlimited high-grade coking coal, natural gas, and the talent of a fine inventor-industrialist, George Westinghouse (1846-1914). Yet over this triumph of human energy hung a dark pall—a literal blanket of smoke that shut out the sun and seared the soil, as well as a metaphorical pall of exploitation, neglect, disorganization, and helplessness. The personnel of the giant mills was rigidly divided into classes, with college graduates at the top of the pyramid, followed by the skilled workers and finally by the mass of unskilled laborers. Corporations rewarded each class appropriately in their own view, with steady salaries and hierarchical promotions for the educated elite, high wages and fringe benefits in housing for the skilled, bitter poverty and unremitting toil for the unskilled.[20] The gulf between respectability and poverty in the corporations established the major segregation of the city, but this class separation was subdivided by further segregation within the neighborhoods of the city by race, national origin, and church affiliation.

Everywhere in the city, production was the focus of attention. Every day, men were killed and maimed by machinery; every trade injured its help without compunction. The pace was too fast, the hours were too long, and in this era it was not the cellar sweatshops or upstairs factory but the mighty enterprise that stood in the front ranks of the callous. The steel mills and railroad yards ran on a twelve-hour day, seven days a week. Yet managers ruthlessly and systematically used their power to block any counterorganization of the men. The Homestead strike of 1892 and the steel strike of 1919 were both crushed by troops and by

[19] . The survey first appeared in summary form in one volume, "The Pittsburgh Survey," Charities and the Commons , 21 (January 1909), 515-1194; the complete edition, Paul U. Kellogg, ed., The Pittsburgh Survey , New York, 1909-1914, 6 volumes.

[20] . David Brody, Steelworkers in America: The Nonunion Era , Cambridge, 1960, pp. 80-95, 112-24.

the illegal use of police and criminal charges, as well as by spies and scabs and the whole military, economic, and civic machinery of repression.

As the corporations sowed, so the city reaped. Old forms of poverty, fostered by neglect, persisted on and on. One of the worst of the U.S. Steel slums was Painter's Row, a district inherited from a small mill-owner forty years before and never either abandoned or repaired. Self-help was not unknown, but it frequently failed; homeowners dug wells to escape dependence on polluted water only to have their wells polluted in turn by runoff from nearby privies. Ignorant and corrupt public officials in a civic government under the thumb of political bosses and business executives fragmented political boundaries so that big companies escaped taxes, and the workman was left without community resources with which to protect his family or educate his children.[21] Pittsburgh was the perfect prototype of centralized private economic power. Its enormous productivity was based on an insane rationality that consumed men, women, and children in order to create personal ascendancy and a multiplicity of mere things.

Pittsburgh, the heavy-industry metropolis, was the cartoon for Chicago, the total urban industrial landscape. This giant new metropolis (299,000 inhabitants in 1870; 2,702,000 in 1920) was subjected to piecemeal investigation by a generation of social workers and university investigators, with the result that in time a Chicago school of social science could present a reasonably complete analysis of the workings of the economy from 1870 to 1920 and trace its effects upon the city. Whereas the Pittsburgh group had confined themselves to accurate reporting of the existing situation, the Chicago team was able to relate the growth of business in Chicago to national growth factors. They could therefore indicate how the patterns of job location and the wages of workers and office employees determined the location of housing. Finally they discovered that this placement defined much of the social and political structure of the city.

Like all the major cities of the world, Chicago owed its importance to its situation at a point where cheap long-distance water transportation met the more expensive land transport. Even more significant was the fact that at the very moment the inventions in farm machinery, the

[21] . F. Elisabeth Crowell, "Painter's Row," Charities and the Commons , 21 (January 1909), 899-910; Roy Lubove, Twentieth Century Pittsburgh: Government, Business, and Environmental Change , New York, 1969, pp. 1-19.

Illustrations

Industrial Metropolis

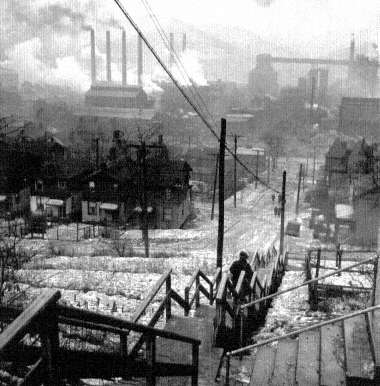

42. Pittsburgh Mill District, 1940. Timeless report from the industrial metropolis: highly articulated science and technology in the mills, leftover spaces, shoddy housing, inconvenience, hazard, and neglect for the people. Library of Congress

43. New Downtown Office Street, Michigan Avenue, Chicago, 1933. Five times as large as Pittsburgh, Chicago reflected the same economic organization and social priorities. Extreme rationalization and concentration of metropolitan commerce, a row of skyscraper office buildings, erected during the twenties, lines new double-decked street with freight deliveries separated from pedestrian and automobile access. Chicago Historical Society

44. Near 12th and Jefferson Streets, Chicago, 1906. Slum use of typical working-class wooden housing in industrial sector along south branch of Chicago River. Overcrowding of structures by poor immigrants, with one and two additional houses in rear yards, nullified any margin of health and safety inherent to a free-standing home. Chicago Historical Society

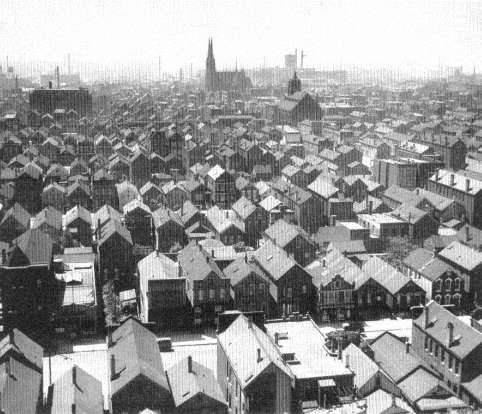

45. Working-Class Chicago, from Damen Avenue and 18th Street, 1934. "Chicago's great southwest side has views as beautiful as any in the world." Daily News, June 30, 1934. Chicago Historical Society

The Downtown

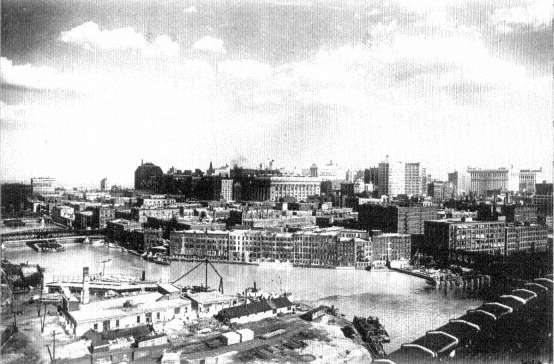

46. South Water Street and the Chicago River, ca. 1920. Downtown from rear, with ring of food dealers, loft manufacturers, wholesale houses next to office towers and public buildings of the commercial core. A City Beautiful project soon replaced these old buildings with the two-level Wacker Drive, Merchandise Mart, and other skyscrapers. Chicago Historical Society

47. Michigan Avenue and Grant Park, Looking North from the Blackstone Hotel, Chicago, ca. 1910. With landscaped park and boulevards between the lake and downtown, the wall of new commercial towers emerged as the visual symbol of Chicago. Old (ca. 1860-80) houses (left) measure the break from the past. Library of Congress

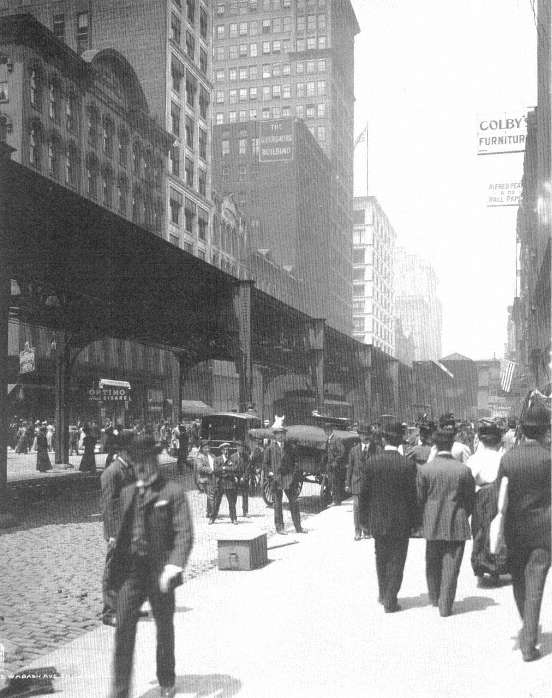

48. Wabash Avenue, Chicago, 1907. New masonry and steel canyons of shopping crowds, white-collar work, novelists' wonder, and sociologists' atomization and alienation. Library of Congress

River Industrial Sectors

49. Chicago River, Looking East Toward Lake Michigan, 1875. Where lake schooners and canal boats (lower right) met, the city's earliest manufacturing districts began. Air-Line Elevator (left) was on the site of present Merchandise Mart. Chicago Historical Society

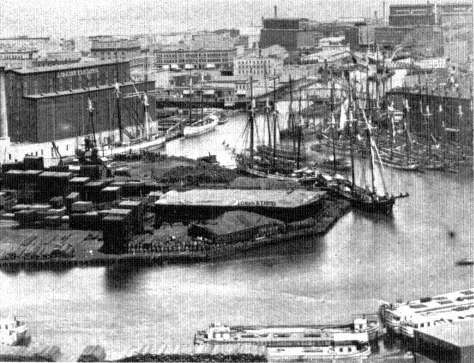

50. South Branch of the Chicago River, 1883. Chicago perfected mass processing of raw materials, animals, grain, and lumber as no city had before. Here, a two-mile wholesale lumber district. Library of Congress

Rail Industrial Sectors

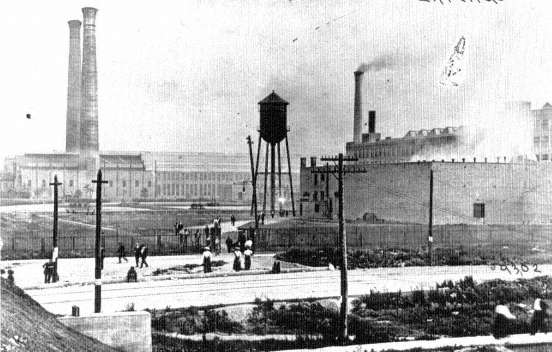

51. Track Elevation at 23rd Street, Chicago, ca. 1907. View of work on Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad shows that the railroad and industrial neighbors often formed a continuous lineal city within the metropolis. Library of Congress

52. Calumet Harbor-Gary Industrial Strip, 1908. Six railroads and artificial harbors for ore boats nourished a sixteen-mile strip of heavy industry, since the late nineteenth century a basic element in Chicago's economy. Here, the new Universal Portland Cement Company plant, next to the Gary steel mills (out of picture, at right), with Calumet Harbor plants of South Chicago down the tracks (upper left). Library of Congress

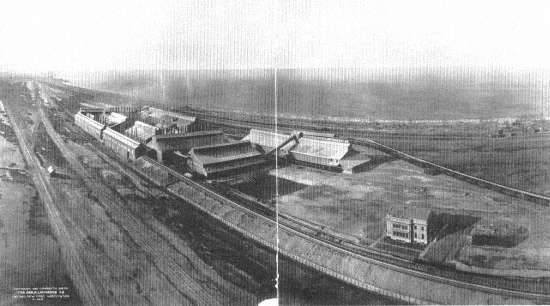

53. Western Electric, Hawthorne Works, Cicero, ca. 1910. In 1903 this manufacturing subsidiary of American Telephone and Telegraph moved its giant plant out to the fringe of the city, where land was plentiful and its operations could be served by the circumferential belt railroads that tied together all the lines of the metropolis. Chicago Historical Society

54. Casting Pig Iron, Iroquois Smelter, Calumet Harbor, South Chicago, 1906. A few workers in the army of hand laborers required by large-scale industry during the early and middle stages of its mechanization. Library of Congress

Residential Infill

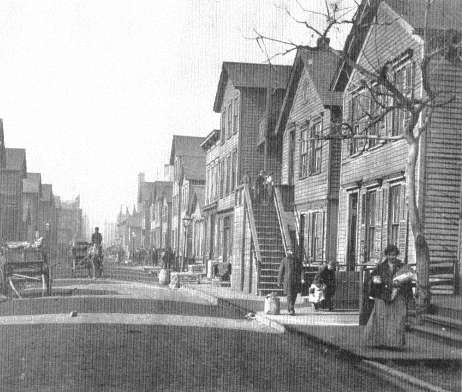

55. Standard Housing, State Street near 15th, Chicago, 1868-69 (above, left). Narrow wooden buildings were one-to-a-lot in good neighborhoods, crammed one behind the other in poor sections; the unpaved street and wooden sidewalk were typical. Chicago Historical Society

56. Standard Housing in Brick, 1848 Bloomingdale Avenue, Chicago, ca. 1912 (center, left). After the 1871 fire, a city ordinance, only laxly enforced, required that the core city be rebuilt in brick. Half-cellar rental units ("up and down" housing) were created out of a single-family house design. Chicago Historical Society

57. The New Environment, 1749-59 North Whipple Street, Chicago, ca. 1912 (below, left). About five miles west of downtown, streetcars and elevated railroads opened up Humboldt Park section to the middle class and upper working class. It provided running water, public sewers, electricity, gas, paved streets and sidewalks, lawn strips and street trees, and closely set single- and two-family wooden houses. Chicago Historical Society

58. Rear Yards, 1754-58 North Whipple Street, Chicago, ca. 1912 (above). Urban houses are intended to make their best impression on the front street, and this plan was carried to the suburbs until the ranch house and attached garage of our time brought cars, children's bicycles, trash barrels, and impressive front entrances all to face the street. Here, an alley carries electricity, gives access for trash and service, with small businesses occupying sheds in rear yards before zoning prevented such mixed land uses. Chicago Historical Society

59. Nineteenth-Century Housing, 44th and Wood Streets, Chicago, 1959 (below). Industrial metropolis housing survives in working-class sections of all American cities. Here, with asphalt siding, encroached upon by cars, a "Back of the Yards" neighborhood of the 1880 standard land and housing plan. Chicago Historical Society, Clarence W. Hines

60. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, 1905. The absence of railroad tracks and easy commuting to downtown shifted the focus of fashion from South Side to the Near North Side Lake Shore. The public parkway system enhanced the private amenities of the rich. Library of Congress

61. Going to a Band Concert, Lincoln Park, Chicago, 1907. The well-to-do always have gotten the best municipal socialism in America. Lincoln Park is the nicest and most continuously maintained and improved of all the Chicago parks. It serves the fashionable North Side. Library of Congress

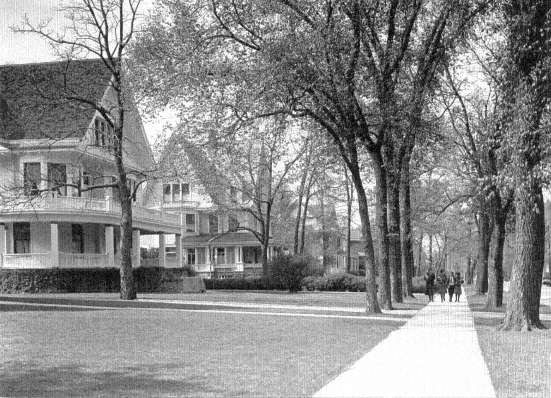

62. Kenilworth Avenue, near Chicago Avenue, Oak Park, 1925. Seven miles west of the Loop, just outside city limits, shaded lawns and planted streets of railroad commuters, the apogee of bourgeois propriety. Chicago Historical Society

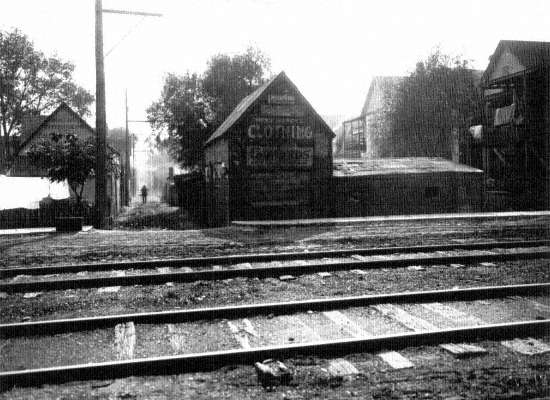

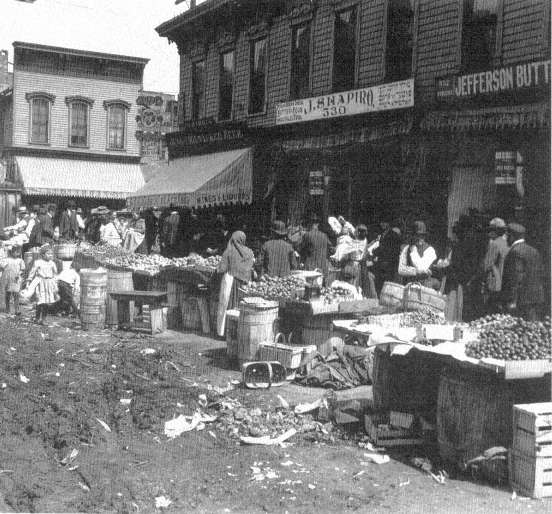

63. Maxwell Street near Jefferson Street, Chicago, ca. 1904-06. Effective street cleaning was one of the important goals of the Progressive Era. "Perhaps our greatest achievement was the discovery of a pavement eighteen inches under the surface of a narrow street, although after it was found we triumphantly discovered a record of its existence in the city archives." Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull House , 1910. Chicago Historical Society

64. Women with Market Baskets, Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904. Chicago Historical Society, Daily News

65. Children on Wooden Sidewalk, Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904. The standard of living among the poor has now risen sufficiently that, in contrast with this, today's poverty pictures show children with sneakers or shoes. Chicago Historical Society, Daily News

66. Family Waiting for Strikers' Parade, Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904. Chicago Historical Society, Daily News

67. Packing House Workers' Strike Parade, 4600 Block, Ashland Avenue, Chicago, 1904. Chicago Historical Society, Daily News

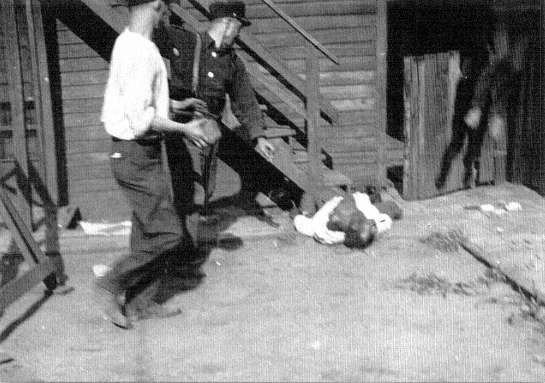

68. Mob Hunting a Black Man, Chicago Race Riots, July 1919. Lacking the racial covenants, housing price barriers, and real-estate associations of the prosperous, poor white neighborhoods enforced their apartheid by violence. Chicago Historical Society

69. Black Victim Stoned to Death, Chicago Race Riots, July 1919. The fleeing man was cornered and killed by the mob. Chicago Historical Society

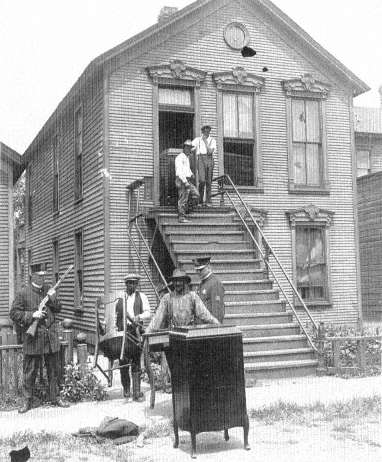

70. Blacks Evicted from Their Houses in the Wake of the Riots, Chicago, July 1919. With the old South Side ghetto jammed by blacks drawn to Chicago for wartime jobs, many sought houses on margins of their neighborhoods. A leader of nearby Kenilworth Improvement Association testified, "We want to do what is right. . . . But these people will have to be more or less pacified. At a conference where their representatives were present, I told them we might as well be frank about it, 'You people are not admitted to our society,' I said. Personally, I have no prejudice against them. They have been clean-in every way, and always prompt in their payments. But, you know, improvements are coming along the lake shore, the Illinois Central, and all that; we can't have these people coming over here." Carl Sand-burg, The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919. Chicago Historical Society

71. Under the El at 63rd Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, Chicago, 1924. Despite bombings, riots, and intimidation, the Negro ghetto could not be denied. Here is its more prosperous, growing edge, having advanced fifteen blocks south since the riots. Chicago Historical Society

42.

Pittsburgh Mill District, 1940

43.

Michigan Avenue, Chicago, 1933

44.

Near 12th and Jefferson Streets, Chicago, 1906

45.

Working-Class Chicago, 1934

46.

South Water Street and the Chicago River, ca. 1920

47.

Michigan Avenue and Grant Park, ca. 1910

48.

Wabash Avenue, Chicago, 1907

49.

Chicago River, Looking East Toward Lake Michigan, 1875

50.

South Branch of the Chicago River, 1883

51.

Track Elevation at 23rd Street, Chicago, ca. 1907

52.

Calumet Harbor—Gary Industrial Strip, 1908

53.

Western Electric, Hawthorne Works, Cicero, ca. 1910

54.

Iroquois Smelter, Calumet Harbor, South Chlcago, 1906

55.

Standard Housing, State Street, Chicago, 1868-69

56.

Standard Housing in Brick, Chicago, ca. 1912

57.

The New Environment, Chicago, ca. 1912

58.

Rear Yards, Chicago, ca. 1912

59.

Nineteenth-Century Housing, Chicago, 1959

60.

Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, 1905

61.

Band Concert, Lincoln Park, Chicago, 1907

62.

Kenilworth Avenue, near Chicago Avenue, Oak Park, 1925

63.

Maxwell Street near Jefferson Street, ca. 1904-06

64.

Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904

65.

Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904

66.

Strikers Parade, Stock Yards District, Chicago, 1904

67.

Packing House Workers Strike Parade, Chicago, 1904

68.

Mob Hunting a Black Man, Chicago Race Riots, July 1919

69.

Black Victim Stoned to Death, Chicago Race Riots, July 1919

70.

Blacks Evicted from Their Houses, Chicago, July 1919

71.

Under the El, Chicago, 1924

perfecting of the railroad, and the unmistakable westward flow of the American population made the occupation of the Midwest profitable, Chicago rose to service this giant hinterland. By 1856, with the completion of the Illinois and Michigan Canal and ten trunk-line railroads, Chicago began its role as a major regional center. At first it functioned simply enough. Commercially it marketed the grain and animals of the new farms while managing the flow of capital out to the farms and towns of the newly settled West, and industrially it manufactured almost every item needed to run a railroad or start a farm, to build a town, to furnish a home, or to clothe a family. The geography of Chicago thus assured its future as a world metropolis. In addition, it was placed in the most rapidly rising sector of the national economy by the functions it performed in mechanized manufacturing, transportation, finance, and servicing of business[22]

The rapid growth of all the elements that composed the city's economy in this era—factories, railroad shops and yards, banks and exchanges, warehouses, offices, department stores, and so on—forced Chicago, and indeed all contemporary American cities, into a new spatial structure: the sector-and-ring pattern of settlement. The strictness of the segregation of this urban organization and the suddenness with which it swept over American cities holds much meaning for today. On the one hand the residential segregation patterns of this era, its core of poverty and rings of rising affluence, still prevail in many cities. On the other hand the swiftness and completeness with which Americans in this era overturned their former habits suggest that in the future strong changes in transportation, job location, and housing prices could easily revolutionize what now seem to be obdurate habits of city dwellers. If we really wished to abandon our current pattern of an inner ring of poverty and black segregation, we could probably do so as quickly as we suddenly assumed it during the late nineteenth century.

In Chicago in the years from 1870 to 1920, the location of jobs was governed by the concentration of economic activity in sectors: narrow pie-shaped wedges of commercial and industrial property stretching out from the downtown business center toward farmland yet to be developed beyond the city. Between the long corridors of the industrial wedges lay vast tracts of empty land, into which settled the major part of the population in three highly segregated great rings: an inner one of

[22] . Homer Hoyt, One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago , Chicago, 1933, pp. 53-59.

poverty and low income marked by cheap divided houses and old apartments, a middle ring of secondhand working-class houses and cottages, and an outer ring of better-quality apartments and homes (Figure V, page 106). In addition, the wealthy and their followers, the downtown white-collar workers, occupied a long wedge of their own, cutting across the rings and running from the fashionable shops and downtown offices outward along the lines of good transportation and attractive sites. By 1920 the axis of this corridor lay along Michigan Avenue and the north shore on Lake Michigan. This generalized sketch of the spatial configuration of Chicago in this era—the radial city with a single center—can be applied to the other industrial metropolises of the time. It was a pattern to which all of them roughly conformed,[23] and it was the very same pattern which the highway engineers rediscovered for themselves in their traffic studies of the 1930s.

The central point from which the industrial sectors of Chicago fanned out lay at the meeting of lake and land traffic at the mouth of the Chicago River. The two sectors that were occupied first ran along the north and south branches of the river, which divided a few blocks inland from Lake Michigan just north of the central downtown area that was to become the Loop. City commerce and settlement commenced at this center. It burgeoned with the opening of the Illinois and Michigan Canal in 1848 and was thereafter continually re-formed and rebuilt by unremitting industrial pressure. Ever since, the river has served as an inner harbor for the handling of grain and lumber and coal, and manufacturers have been attracted by the accessibility of transport. The river banks became the industrial sinews of the city. Here Cyrus H. McCormick (1809-84) built his reaper factory, originally on the North Branch; later on the South Branch when he rebuilt after the Chicago fire of 1871.[24] As the city grew, competition for central space drove the price of inner-city land up and up, and industry edged ever outward from the center along the branches of the river, paralleled by the lines of the railroad. Other businesses not immediately dependent on the complementary cluster of small firms and support from the downtown services followed them out—Montgomery Ward to the North Branch,

[23] . Robert E. Park, Ernest W. Burgess, and Roderick D. McKenzie, The City , Chicago, 1925, pp. 47-58; U.S. Federal Housing Administration, The Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods in American Cities , Homer Hoyt, ed., Washington, 1939, pp. 72-78, 86-104; Harlan Bartholomew, Urban Land Uses , Cambridge, 1932, pp. 97-102.

[24] . Hoyt, Land Values in Chicago , p. 104.

Figure IV.

Industrial and Transportation Structure of Chicago, 1920, 1970

SOURCE: Homer Hoyt, One Hundred Years o/ Land Values in Chicago,

Chicago, 1933; Center for Urban Studies, University of Chicago,

Mid-Chicago Economic Development Study, Chicago, February, 1966.

machinery factories to the South Branch, while others joined Sears, Roebuck in a due-west migration from the city center.[25]

The city core itself assumed a mature form in the early years of the twentieth century. At the center, land mounted in value until it was prohibitive to manufacturing and wholesaling on any considerable scale; instead the innermost streets blossomed with skyscrapers and theaters and stores, all the full flowering of an old-fashioned metropolitan downtown. Around this center, factories and commerce threw up an immense wall of structures. The wall was composed of factories that needed minimal space and so could remain near the center by occupying multi-story buildings and of wholesale houses that were dependent on downtown passenger stations, hotels, and customer entertainment.

It is clear that this era had spawned industrial sectors and a downtown far removed from the urbanism of New York in the preceding period, with its mixed commercial and residential center and informal fringes. Rather, every part of the industrial metropolis now became more rigidly compartmentalized with each year of growth. After about 1890, no neighborhood in the city of Chicago sheltered industry, commerce, and homes of all classes of citizens; segregation of industrial, commercial, and residential land became the hallmark of the metropolis.

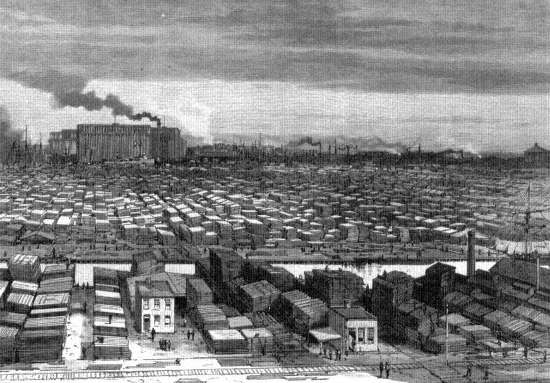

Rail lines coming in from the West and South added two more manufacturing sectors to those created by the Chicago River and the tracks that ran parallel to it. The transportation activity itself tending the yards, repairing cars and locomotives, building all sorts of equipment from fishplates to Pullman cars—generated an enormous volume of employment. Chicago was the nation's foremost rail-terminal city, and the prosperity of its railroads did much to build its employment base. By complementarity and the sheer expansion of urban business, these new rail sectors attracted industry. Most famous were the stockyards and meat-packing houses of the southern sector, a development of 1865 at Thirty-ninth and Halsted Streets that comprised a hundred acres of cattle pens and two hundred and seventy-five additional acres devoted to slaughterhouses and packing plants. The dependence of this gigantic operation on cattle cars and refrigerator cars forbade any but a rail location.

The stockyards forecast a special urban characteristic of the industry

[25] . Center for Urban Studies, University of Chicago, Mid-Chicago Economic Development Study , Chicago, February 1966, pp. 16-37; Hoyt, Land Values in Chicago , pp. 82-85.

of the 1870-1920 period—the movement of mammoth enterprises completely outside the confines of the core city. Steel mills, electrical machinery plants, car factories, all industries that needed good transportation for great quantities of shipments as well as vast open land for future expansion, followed the meat packers' example in seeking locations at the fringes of the manufacturing sectors.[26] In 1880, George M. Pullman (1831-97) built his shops and model town south of the city, and he was soon followed by steel mills, cement plants, and the whole Calumet River heavy industrial complex. The United States Steel Corporation placed a brand-new integrated steel plant in Gary, Indiana, a city constructed for the purpose in 1905 just east of the Calumet concentration. The industrial satellite city, a mill town set within a metropolitan region where workers could live and labor in their own community instead of commuting to work, was a characteristic type of the era. All such satellites owed their appearance to the configuration of rail transportation and the scale of late nineteenth-century mechanized manufacture. As Chairman Elbert H. Gary set his new mill down outside Chicago, so Westinghouse built in East Liberty on the edge of Pittsburgh and Ford built at River Rouge outside Detroit.[27]

Finally a spatial relationship between the metropolitan railroad lines and the outer industrial locations should be mentioned, less for its impact on the structure of Chicago in this era than for its future consequences. The radial Chicago form had emerged from the railroads that served the industrial sectors, which fanned out from the core of the city. In addition, however, transfer of freight from one line to another and from one sector to another necessitated interconnections. The most inclusive of these linkages were the rectangular belt lines that crossed over the city's radial trackage to pass almost entirely around the city. A map of the railroads in this period can therefore be seen as the superimposition of a giant grid, reminiscent of the early township grid pattern, upon the older radial lines (Figure IV, page 103). Moreover, where the belt lines intersected the radials, still other centers were created. This evolving multicentered layout helped to relieve the city's inner terminals from the traffic congestion that inevitably tends to plague a strongly central-

[26] . Harold M. Mayer, "Localization of Railway Facilities in Metropolitan Centers as Typified by Chicago," Journal of Land and Public Utility Economics , 20 (November 1944), 299-315.

[27] . Graham R. Taylor, Satellite Cities, A Study of Industrial Suburbs , New York, 1915, pp. 1-67, 165-93; Glenn E. McLaughlin, Growth of American Manufacturing Areas , Pittsburgh, 1938, pp. 127-32.

Figure V.

Class Rings and Sectors of

Residential Chicago, 1920 Source:

Federal Housing Administration,

Structure and Growth of Residential

Neighborhoods in American Cities,

Homer Hoyt, ed., Washington, 1939.

ized system with all the heaviest traffic concentrated at its center.[28] After 1900 the belt lines themselves became increasingly attractive to industrial firms. Western Electric, for example, moved its plant in 1903 to Twenty-second Street and Cicero Avenue on the outermost belt line.[29]

In the years after World War II, highway engineers began to appro-

[28] . The strong radial quality of the alignment of tracks in American cities made freight traffic jams endemic during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and brought a catastrophic breakdown during the First World War. K. Austin Kerr, American Railroad Politics 1914-1920 , Pittsburgh, 1968, p. 40.

[29] . Hoyt, Land Values in Chicago , pp. 104-7, 213; Robert L. Wrigley, Jr., "Organized Industrial Districts," Journal of Law and Public Utility Economics , 23 (May 1947), 180-98.

priate the partially occupied land along the railroad corridors, and three of Chicago's four interstate highways have repeated in a rough way the radial and grid alignments attributable to the old railroads. When the next section of the interstate Crosstown Expressway is built along Cicero Avenue, the duplication of the old rail system will be complete, and Chicago will have constructed a crude grid layout of highways whose squares grow larger as one moves from the center of the city.[30] Such a pattern has proved highly efficient for the purpose of moving traffic through a multicentered network that serves multiple locations of origin and destination. It is a pattern that much resembles the one made by Los Angeles highways, a city that so fully exemplifies the era of the automobile megalopolis.

The great preponderance of urban land has always been taken up by residential lots and streets, and these miles and miles of neighborhoods filled the spaces between the industrial fingers of the metropolis. In the half century after 1870 these neighborhoods ceased to be a jumble of rich and poor, immigrant and native, black and white, as they were in the former era of the big city. Instead the neighborhoods of the industrial metropolis came to be arranged in a systematic pattern of socioeconomic segregation. The rings of residential settlement varied from inner poverty to outer affluence,[31] and this pattern of residential segregation was as characteristic of the metropolis of 1870-1920 as were its industrial sectors, its satellites, and its downtown areas.

The suddenness with which the new pattern settled upon American cities has been documented for Chicago by its social scientists. The new possibilities of cable and electric street transit worked with rapid growth and a middle-class fashion in suburban living and downtown shopping to revolutionize the social geography of the American city.

On October 9, 1871, the Chicago Fire burned out the core of the

[30] . Center for Urban Studies, Mid-Chicago Development , plates 13 and 14; Joseph R. Passonneau, "Urban Expressway Design in the United States: The Institutional Framework," Systems Analysis for Social Problems , Alfred Blumenstein et al., eds., Washington Operations Research Council, Washington, 1970, pp. 210-22.

[31] . The sector of the wealthy, occupying an attractive site and enjoying easy transportation to the downtown (Chicago's North Shore) is a significant exception to the ring arrangement of residential land. The reasons for a sector of the rich, not a ring, are twofold: the rich are not numerous enough to fill a metropolitan ring, and they can pay enough to control expensive land near the center of the city. The phenomenon of this sector in 1870-1920 cities has been shown to be general by Homer Hoyt, in his Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods , pp. 112-22; and Peter G. Goheen, Victorian Toronto , pp. 201-13.

city and its North Side, leveling 2,100 acres of city land and destroying nearly a third of its structures. At first Chicagoans rebuilt their city in somewhat the same mixed central business and residential patterns with which they were familiar. With mortgage funds from the East, speculators rebuilt the downtown office buildings to a height of four and five stories instead of the previous two or three, while a few promoters hazarded six and even eight stories. But near the offices and stores, a block or two from the railroads, warehouses, and factories of the center of the city, many middle-class Chicagoans rebuilt their homes or settled into rented quarters or small hotels or boardinghouses in the core city.

During the 1870s the class pattern of Chicago homes bridged both the old and the new style of neighborhoods. The presence of some middle-class and well-to-do families near the downtown area recalled the old tradition, as did the outer location of many working-class dwellings. The new, however, was represented by a growing suburban fringe of middle-class families who were commuting to the downtown offices and stores.

During the next two decades the outmigration of Chicago's middle class completely reorganized the settlement patterns of the city. Instead of taking up vacant tracts in the partially built-up fringe where the working class were also settled, as had been the practice in the past, the middle class skipped over that ring entirely and settled itself in its own districts beyond. In Chicago the specific location of the ring of middle-class settlement had been determined by the building of a series of parks and boulevards in imitation of New York's Central Park and Baron Georges Haussmann's Paris boulevards. Finally mass suburban living was made possible by a succession of transportation improvements during the years from 1887 to 1894. Cable lines, electric surface lines, and elevated rapid transit all were introduced. Simultaneously, a uniform five-cent fare with one free transfer facilitated commuting.[32]

In this way Chicago's residential pattern by class had been fully set by 1894. The Loop was surrounded by decaying structures waiting to be taken up for commercial and industrial uses as the downtown expanded. Beyond this section, abandoned by the middle class, was the belt of working-class housing, close to jobs in the core city and close to the industrial sectors. Into the inner area poured the immigrants, native and foreign, and their poverty and consequent overcrowding of existing

[32] . Hoyt, Land Values in Chicago , pp. 104-7, 429.

homes transformed twenty-year-old middle-class houses and workers' cottages into the slums of the core city.[33]

With this new urban segregation of classes by housing, the core of poverty, and the rings of rising affluence, the working class came to assume the city-building role the middle class formerly performed. In the teens and twenties the working class, in order to find land to build upon or to rent, had to expand into those suburban areas which the middle class had already partially occupied, just as the middle class had earlier taken up vacant land in the mixed fringe of the old premetropolitan city. As their members moved outward they had to buy land that had already advanced in price in anticipation of suburban development. Often they found subdivisions of small lots which bore the charges of full city improvements, such as streets and curbs and sidewalks, city water and sewers, and gas and electricity, and which had to be built upon in conformity with modern building codes. The cheap working-class dwelling, the tiny wooden house or shack often built by the owner upon undesirable fringe land, now became a legal as well as an economic impossibility. Such housing returned only after World War II, with the trailer parks and self-help housing that occupy edges and pockets of the megalopolis. For most of the workers of the city the entrapment of the early twentieth-century housing pattern endured, and the loss of the single-family cottage which had been the staple of Chicago workers since long before the fire was never recovered.[34] From the first decades of the twentieth century dates the relentless shortage of decent detached homes for the blue-collar class and the widespread use of two-family and three-flat structures; by 1915, statistics showed that single-family homes had fallen to 10.8 percent of all new construction in Chicago.

The street railway, elevated in the Loop section, further influenced the makeup of metropolitan neighborhoods by nourishing the whole central-city retailing complex. Millions of men and women could now be carried cheaply in and out of the core to work and to shop. Although rows of stores sprang up along the streetcar lines and at the transfer points to serve the neighborhood, these stores faced intense competition from the shops of the Loop. Well-to-do women formed the habit of

[33] . For documentation of inner-ring housing conditions, see Edith Abbott and Sophonisba Breckinridge, The Tenements of Chicago 1908-1935 , Chicago, 1936, pp. 72-169.

[34] . Hoyt, Land Values in Chicago , p. 231.

shopping as a form of daily entertainment; for the women of the middle and working classes the seeking of bargains and major purchases in downtown stores became a focal point of their lives. To a degree perhaps not equaled since the 1830s and the heyday of the Broadway promenade in New York City,[35] the downtown district became the city for Chicagoans. It was the place of work for tens of thousands, a market for hundreds of thousands, a theater for thousands more. Yet for a city like Chicago, a metropolis of two million, even though its newspapers, tall buildings, and advertisements may have cried out for civic pride and unity, a downtown could not re-create the recognitions and sociability of a city of three hundred thousand like old New York. Instead the metropolitan downtown functioned as the symbol of unity and pride for a mass of individuals.

Chicago sociologists of the early twentieth century spoke of their fellow city dwellers as isolated individuals, cut off from each other by a screen of thousands of impersonal commercial contacts.[36] Surely the downtown and its crowds looked that way; so too did the Chicago novelists report it.[37] But the monumentality of the lake front and the Loop and their power as symbols misled the novelists. The sociological studies that have come down to us do not show a mass of two million discrete individuals but rather a highly fragmented society tightly structured along economic lines.

The scholars' reports gave the clue to the new social linkages: workers were tied to mills and foremen within them; immigrant laborers were tied to padrones and sweatshop bosses; office girls had been organized in clerical pools or became personal servants for the men they served; store clerks were at the mercy of buyers and merchants. The people of Chicago were systematized by work relationships and bound into a gigantic metropolitan economic web. The Chicago studies made plain how much of the city dweller's life was ordered by the sway of the boss, the foreman, and the buyer.

[35] . John A. Kouwenhoven, The Columbia Historical Portrait of New York , Garden City, 1953, p. 145.

[36] . Robert E. Park, "The City: Suggestions for the Investigation of Human Behavior in the City Environment," American Journal of Sociology , 20 (March 1915), 577-612.

[37] . For instance, Theodore Dreiser's Carrie Meeber in Sister Carrie (New York, 1900) and James T. Farrell's Studs Lonigan and his friends (New York, 1932-35) are overwhelmed by the early twentieth-century downtown environment which they experienced from the street. Inside the skyscrapers conditions were portrayed as more human, if also more vicious; cf. Henry B. Fuller, The Cliff Dwellers (1893).

In addition social investigations revealed that, despite basic economic ties and the class rings of residential settlement, no metropolitan class consciousness had emerged. In the residential districts there was further fragmentation by race, religion, and ethnicity.[38] Local politicians did their best to manipulate this configuration for their own ends, but it was a fragmentation without a uniform political direction. Harvey Zorbaugh's wonderful 1923 study of the near North Side of the city showed the cleavages. Here within a few square blocks lived the city's artists and writers and bohemians. There were streets of young people from the farms and small towns of the Midwest living in roominghouses and trying to find a place for themselves in the life of the city, as well as an enclave of Italian immigrants and a Persian colony, flanked along the lake edge by a narrow strip known as the Gold Coast and occupied by Chicago's oldest and wealthiest families. Such a district had not produced even district-wide power groupings, to say nothing of class consensus or political programs. Experiments by settlement-house workers or citizen volunteers to transform the district into a single social and political entity failed because the residents' significant ties were to their jobs, their homes, their ethnic groups.[39]

One extremely influential group, however, did live in the district and enjoyed city-wide ascendancy—the wealthy Anglo-Saxon Chicagoans of the Gold Coast. These families owned, controlled, or worked as professionals with the leading economic units of the city. For them the downtown and its towers were the effective center of the city. From the windows of their skyscraper offices they could look over the roofs of the city, and from their desks they could read the reports of the far-flung factories, shops, banks, and properties of the metropolitan region. It is no accident that the Commercial Club, whose members were the wealthy Chicago businessmen, should be the first to propose a city plan for the entire metropolis.

Zorbaugh concluded his study of social fragmentation by saying that the new industrial metropolis contained only one group who had the entire city as their focus, the men of the Gold Coast, and that therefore upon that group would depend the future of any program requiring city-

[38] . A recent study of elections in Chicago shows that, except for a few issues which particularly attracted the middle class, voting behavior was linked to ethnicity, not to class. See John M. Allswang, A House for All Peoples , Lexington, 1971, pp. 182-212.

[39] . Harvey W. Zorbaugh, The Gold Coast and the Slum , Chicago, 1929, pp. 182-220.

wide attention. Though an admirer of the generosity and wisdom of some of the Gold Coast families—indeed he thought them the city's only hope—Zorbaugh went on to point out that the structure of social relationships in the new metropolis was such that this elite could know nothing of the daily existence of the country boys and girls, the Sicilians, the Persians, and the bohemians who lived a few blocks away.[40] Remarkably, since the study was firmly rooted in the academic style of his day, Zorbaugh ends by describing the structure of the industrial metropolis in terms that parallel our modem assessment of the corporation which had made the industrial metropolis possible. He could have described his Chicago as Alfred Chandler did the early twentieth-century corporation:

Yet the dominant centralized structure had one basic weakness. A very few men were still entrusted with a great number of complex decisions. . . . Because these administrators had spent most of their business careers within a single functional activity, they had little experience or interest in understanding the needs and problems of the other departments or of the corporation as a whole. As long as an enterprise belonged in an industry whose markets, sources of raw materials, and production processes remained relatively unchanged, few entrepreneurial decisions had to be reached. In that situation such a weakness was not critical, but where technology, markets, and sources of supply were changing rapidly, the defects of such a structure became more obvious.[41]

Yet change, within the city and within the network of cities, had always been the essence of the American urban system. Even as downtown skyscrapers piled ever higher in the boom of the twenties, the breakup of the overcentralized, oversegregated industrial metropolis began.

[40] . Ibid., pp. 261-79.

[41] . Chandler, Strategy and Structure , p. 41.