II. Spirit Possession in the Sambirano

5. The World of the Spirits

Tromba possession is the quintessence of Sakalava religious experience. Throughout Madagascar, ancestors and other spirits are an important aspect of everyday life, yet no form of possession is more widespread than tromba (see Estrade 1985). For the Sakalava, the spirit world is inhabited by royal and common ancestors, lost souls, nature spirits, and malicious, evil spirits. Tromba, as the spirits of dead Sakalava royalty, are the most significant and influential in terms of daily interactions that occur between the living and the dead. As Huntington has observed, the “royal ancestors belong, in one sense, to everyone” and are regarded as “the ‘national ancestors’ ” of the Sakalava (Huntington and Metcalf 1979: 95).

Tromba as an institution provides keys for understanding Sakalava notions of the world, offering explanations and solutions for misfortune. It is also an important part of any major celebration. Tromba spirits affect the lives of both Sakalava royalty and commoner, and they are active in public and private spheres. These spirits appear in such diverse contexts as royal events, healing rituals, after the birth of a child, and during domestic disputes. Furthermore, a tromba ceremony may be viewed as an encapsulation of Sakalava experience in time and space. Tromba spirits enable Sakalava to record and interpret historical experience. They also offer ways to understand how Sakalava perceive the local geography of their ancestral land and the nature of their responses to economic development. For these reasons, one can not fully understand what it means to be Sakalava without understanding tromba.

In the past, tromba possession was a purely Sakalava institution, tying the living to the dead, and commoner to royalty. Although tromba in Ambanja continues to be a marker of Sakalava identity and tera-tany status, it has undergone radical transformations during this century. Accompanying the increased immigration of non-Sakalava to this region, there has been an explosion in the incidence of possession within the last thirty years, involving the incorporation of new tromba and other spirits and the participation of peoples of diverse ethnic backgrounds. When Malagasy speak of Ambanja, they often remark that there is a lot (misy tromba maro) or, perhaps, too much tromba (laotra ny tromba!). Today the incidence of possession in Ambanja is high when compared to other regions of Madagascar as well as neighboring areas of Sakalava territory.

Discussions of the causes of spirit possession are best argued when rooted in the internal logic of the culture in which they are found (cf. Boddy 1988: 12, who in turn cites Crapanzano 1977a: 11). The interpretation becomes flawed and misleading if it draws exclusively from Western conceptualizations of the body and mind as distinct categories, a notion that only distorts indigenous notions of possession (see also Scheper-Hughes and Lock 1987). The purpose of this chapter is to give the reader a general impression of what possession looks like and to provide an overview of the Sakalava spiritual world.

| • | • | • |

The Dynamics of Tromba in Daily Life

Tromba are perhaps the most well-known—and best documented—of the spirits of Madagascar. The term tromba is sometimes used in Madagascar in a general sense to refer to any form of possession. In the strictest sense of the term, tromba are the spirits of dead Sakalava royalty (ampanjaka) whose lineages are based throughout western Madagascar.[1] The recent proliferation of spirits in Ambanja is rendering this definition of tromba increasingly problematic. Today, tromba continues to play an important part in preserving records of these royal genealogies, providing a shorthand account of the succession of royalty (most often rulers). In recent years it has also become a more flexible category so that it now includes a wide assortment of other spirits. They, like their mediums, are in a sense “strangers” to these lineages, since not all are important rulers from the past.

Tromba in Royal Contexts

In the Sambirano one finds many types of tromba and other spirits. From a precolonial point of view, the key figures of the Bemazava spirit world are those that only appear in mediums on the island of Nosy Faly, in the village that guards the royal tombs (zomba, mahabo). These are the oldest and most powerful of the Bemazava ancestors, and they are often referred to as the tromba maventibe, or the “greatest tromba.” Each of these spirits possesses only one medium, who is referred to as a saha (“valley” or “canal”). Saha live full-time at Nosy Faly (there were four living there in 1987), and their sole purpose is to serve the living royalty. Periodically, members of the royal family come to pay tribute to or consult their ancestors (cf. Baré 1980, especially chap. 6). Since it is forbidden for rulers to approach the royal tombs when they are alive, their personal counselors regularly visit the island to seek advice on issues that affect the well-being of Bemazava royalty and, more generally, tera-tany who inhabit the kingdom.[2]

Two assumptions are central to Sakalava tromba: that all spirits were royalty when they were alive, and that any member of the royal lineage may become a tromba spirit after death (this usually takes about twenty years). When a great royal tromba possesses a medium, it takes her to the tombs: in other words, she will travel to and arrive at the tombs in trance. The royal guardians (ngahy), who reside at the tombs, will test the tromba spirit to make sure it is the ancestor it claims to be. I have heard two accounts from living royalty who have been summoned to the tombs to help administer and witness an examination of a tromba. In both cases the spirit passed, since it was able to pick out personal possessions from a pile of paraphernalia presented to it by the ngahy, and it described the appearance and location of an item that was in a private area of a witness’s house.

The recent proliferation of lesser spirits outside of Nosy Faly make it necessary to distinguish between different types of tromba spirits. Kent (1968) and other authors (cf. Lombard 1973 and Baré 1980) use the term dady to refer to the royal cult of ancestors and tromba to refer to other Sakalava possessing spirits. Perhaps these definitions were true in the past in Ambanja, and they are used elsewhere in Madagascar (see Lombard [1988] on the southern Sakalava of Menabe). In Ambanja, however, the medium serves as the point of reference and the means for distinguishing between these spirits. Royalty and commoner alike draw distinctions between the great tromba of Nosy Faly and other spirits who appear in town by saying that only a medium who has passed an exam (and who usually then takes up residence at the royal tombs) may be referred to as a saha. When speaking of other mediums one simply says that she “has a tromba” (misy tromba, lit. “there is a tromba”). Today the term dady, which means “grandparent,” is a generational term used to refer to the tromba spirits of the greatest age and stature. The founding ancestor of the Bemazava, Andriantompoeniarivo, for example, is affectionately referred to as dadilahy (“grandfather”) by living royalty. This spirit’s saha, in turn, is referred to as dadibe (meaning “big-” or “great-grandmother”). This is because a medium is structurally defined as the spouse of her spirit (see chapter 7).

Unfortunately, it is cumbersome to refer to the medium’s status in order to distinguish between these two types of possession. For this reason I will use the spirit’s audience (and its function) as the point of reference when comparing these two forms. Thus royal tromba are the most important of the Bemazava ancestral spirits that appear only at Nosy Faly, and popular tromba are those that possess mediums in town. Since the town of Ambanja is the focus of this study, the reader should assume that I am speaking of the popular spiritual realm unless spirits are referred to specifically as “royal tromba.”

The Popularization of Tromba

The term “popularization,” as I am using it here, has several meanings. First, it refers to the shift in emphasis from royal tombs to the community of commoners. As in the past, royal spirits are central to the lives of royalty. Yet today Sakalava of common descent possess little understanding of the old order. Only elders have any knowledge of the roles and duties their own grandparents had in relation to living and dead royalty. For most Sakalava in contemporary Ambanja, the royal tromba and their saha seem distant and only occasionally touch their lives, since they are far away on the smaller island. Instead, it is the popular tromba spirits of Ambanja which are important for commoners. The respect that commoners express for royalty is manifested in ceremonies that occur in town, involving spirits of much smaller stature than those that can be found at the royal tombs. Second, accompanying this shift from the tombs to town is the dramatic increase in the incidence of tromba possession over the last few decades. Older informants living in Ambanja report that in the 1940s and 1950s there was only a handful of mediums operating in town, possessed by the stately spirits of old royalty. These mediums assisted commoners, primarily as healers. Today tromba possession is widespread; my data collected throughout 1987 reveal that roughly 50 percent of all women are possessed. Today, tromba possession touches the lives of nearly all of this town’s inhabitants, since almost everyone either knows a medium personally, has consulted a tromba spirit, or has friends or kin who have done so. A third characteristic of popularization is that it involves widespread participation of non-Sakalava female migrants in what was previously an almost exclusively Sakalava domain (the ramifications of this proliferation—generally speaking and in reference to migrants—will be discussed in greater detail in subsequent chapters, especially chapter 7).

Fourth, popularization marks an increase in the number and types of spirits that are now identified as tromba spirits. Although the majority of these new popular tromba spirits are Sakalava, tera-tany often say that Tsimihety and other groups are responsible for bringing them from the south to Ambanja. In addition, recent trends reflect the incorporation of obscure royalty and, potentially, non-royalty into the world of tromba. Many of the spirits that now appear in Ambanja are not members of the Bemazava lineage but are distant kin, coming primarily from the region near Mahajanga. The vast majority of these spirits are obscure members of the Zafin’i’mena royal lineages. Although these spirits usually can be located in the royal genealogies, they are considered to be royalty of low status, for many of them died young without having ruled or accomplished much in their lifetimes. Finally, these new tromba spirits also reflect the nature of contemporary town life in Ambanja. Whereas the stories of the greatest royal tromba are well-known and cherished, few mediums in Ambanja know the details of the lives of popular spirits. The spirits active in town are not the staid and powerful royalty of the past, instead, they are cowboys, boxers, soccer players, and prostitutes. Their life stories often echo the experiences of people who live in the urban environment of Ambanja. They have been in automobile accidents, they like to drink and dance, they frequent boxing (morengy) matches, and several have died at the hands of their lovers or rivals.

The popularization of tromba is now beginning to reveal a shift away from royal status through the incorporation of a few non-royal spirits. The most important of these are spirits who are not direct descendants of royalty, but who are affines who appear to have achieved royal status over time and through association with other tromba spirits. Others are commoners who have retained their lower status after death. For example, a number of informants hoped that friends or kin who had died in a recent ferryboat accident would one day become tromba so that they could talk to them, and there is already a young woman in Ambanja who is possessed by her twin sister who died in this accident. I also know of a spirit whose dog, named Markos, has become a tromba, and these two accompany each other at ceremonies.

Another recent trend involves the incorporation of Christian personalities into the tromba world. In Diégo, the Virgin Mary (Masina Marie) occasionally appears in mediums. In 1988 John the Baptist (St. Jean) arrived in a medium in the middle of a Catholic service. This spirit stood and began to evangelize in the style of a Protestant pastor, infuriating the officiating priest. From a Sakalava point of view, these spirits are confounding, as they defy all rules of tromba. As one of my assistants wrote recently, “I do not consider St. Jean to be a tromba; he is really just some type of njarinintsy” (an evil spirit; see below). These examples are important, since they reveal that tromba is not a static institution but is dynamic and evolving.

The Organizing Principles of Tromba

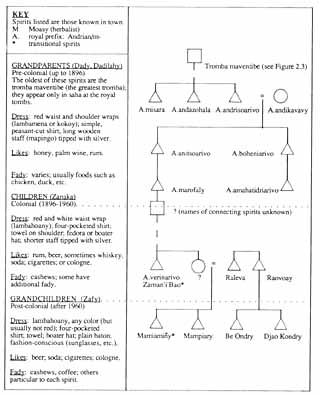

There are several organizing principles inherent to tromba possession which are significant in both royal and popular contexts. First, tromba spirits (like all northern Sakalava royalty) are divided into two major descent groups: the Zafin’i’mena (“Grandchildren of Gold”) and Zafin’i’fotsy (“Grandchildren of Silver”). (These are abbreviated versions of Zafinbolamena and Zafinbolafotsy [see Lombard 1988]). Gold (vola mena, or “red money”) and silver (vola fotsy, or “white money”) are symbols of Sakalava royalty, and these metals are represented by the colors red and white during tromba ceremonies and other rituals. Thus, Zafin’i’mena tromba spirits dress in red and Zafin’i’fotsy dress in white.

Each descent group can be further broken down into a collection of lineages. Each of these corresponds to a different Sakalava dynasty that has its own royal tomb. Tromba genealogies serve as truncated versions of these lineages. Within each lineage, tromba spirits can be divided into three generational groups: the oldest are the Grandparents (dadilahy; grandmothers: dady), of whom the tromba maventibe (“very big” or “biggest tromba”) are the most powerful (and the ones that are generally only found at the royal tombs). Beneath the Grandparents are the “Children” (zanaka) and “Grandchildren” (zafy).

Since each spirit is tied to a specific royal tomb, it is also important to locate it within the context of Sakalava sacred geography. In this context, the tanindrazan̂a or ancestral land provides a way to refer to types of tromba spirits. Among the Zafin’i’mena, for example, there are baka atsimo (lit. “coming from the south”) who are from the region of Mahajanga.[3] Similarly, there is a category of Zafin’i’fotsy tromba which is referred to as the baka andrano (lit. “coming from the water”). These are the spirits of Sakalava royalty who, in the eighteenth century, chose to commit suicide by drowning to escape serving under their Merina conquerors (cf. Feeley-Harnik 1988: 73). It is the baka atsimo and baka andrano who appear most frequently at the ceremonies in town.

Finally, since tromba were at one time living persons, their deeds and personal histories are also important, and these are often reflected in their names. It is fady to utter the given names of Sakalava royalty after they have died. As noted earlier, after death, a royal person is given a new praise name (fitahina). If he or she becomes a tromba spirit, this is the name the spirit will adopt. For example, the former Bemazava ruler was Tsiaraso II; his tromba name is Andriamandefitriarivo, which means literally, “the ruler who is tolerant of many.” Today, many Sakalava only observe this name taboo in a loose sense. During interviews with informants I found that many would shyly refer to the most recent rulers by their living names when they would trace the royal lineages, and use the tromba names when referring to the same persons specifically in reference to spirit genealogies. Because tromba names are long, many of the better known spirits have nicknames: thus Ndramiverinarivo (“the king to whom many return”), a very well-known tromba spirit, is often referred to as either “Ndramivery” or “Zaman’i’Bao” (“Bao’s Uncle”).

These genealogical, generational, and geographical categories comprise the essential operational principles of tromba possession. Their importance is evident in several contexts. If one wishes to invoke a spirit, one must cite its genealogy in descending order, calling first upon the ancestors on high, the Zanahary. The tromba spirit must then be located within its general descent group—the Zafin’i’mena or Zafin’i’fotsy—by calling on the more important tromba spirits of this lineage, the Grandparents. One then descends through the tromba’s specific lineage, and only then does one address the spirit. The spirit should be able to identify itself when it arrives, stating its genealogy (cf. Ottino 1965) by naming its classificatory Grandparent(s) and Parent(s). It should also be able to tell the story of its death. Finally, during a ceremony the order in which spirits arrive and depart reflects these descent groups and the hierarchy of the three generations. In essence, a tromba ceremony is a dramatization of the genealogical system.

| • | • | • |

The Possession Experience

Tromba possession permeates much of everyday life in Ambanja. Large-scale ceremonies that involve a gathering of mediums (and their spirits), kin and neighbors, musicians, and clients occur frequently in this town. This is especially true during the dry months from May through September,[4] because at this time it is easiest to travel. Children are out of school on vacation, and since it overlaps with the coffee season, many adults have the cash needed to host ceremonies. Throughout the course of the year in 1987 I attended a total of nine ceremonies and knew of two dozen more; a third of all of these ceremonies occurred within earshot of my house.

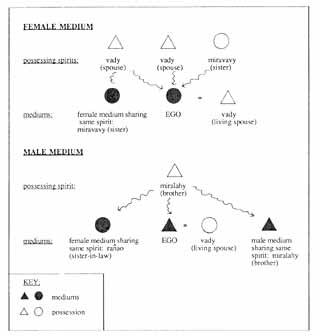

Tromba ceremonies are lively dramas where the spirits of dead royalty come to life and interact with the living (cf. Firth 1967 and Lambek 1988a on possession as performance; see also V. Turner 1987, especially pp. 33–71). This they do by possessing mediums, the majority of whom are female. Tromba spirits may be aggressive and, at times, physically threatening, playful, or flirtatious. Their characteristics vary according to their age and unique personality. Tromba, unlike other Sakalava spirits (as well as many others found cross-culturally), have elaborate histories and highly developed personalities, and each spirit has its own style of dress, behavior, and body of fady, making it easy for the trained observer to identify the spirit once the medium has entered trance. Because of these attributes, when tromba spirits possess their mediums, one often forgets that they are not actual living persons. Since the majority of mediums are female, while spirits tend to be male, the most striking aspect of tromba possession is that one watches a female medium transform into a male spirit.

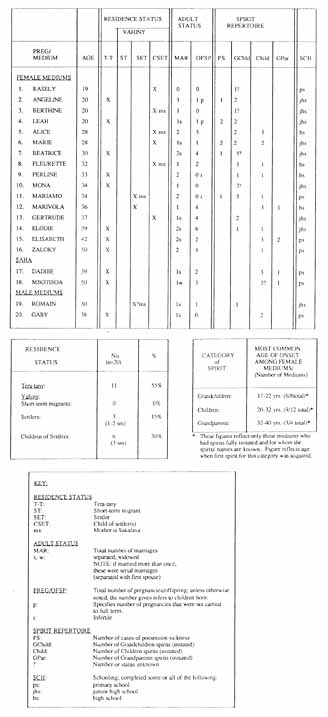

The issue of gender is integral to understanding the nature of tromba possession in Ambanja. Spirits may possess men, but this is unusual: where 96 percent (94 out of 98) of the tromba mediums I encountered were women. The reasons given for this by the living (and by the spirits as well) is that women are more susceptible to possession because they are “weak” (malemy) and it is difficult for them to resist the advances of spirits, in contrast to men who are “strong” (hery). In addition, since most spirits are male, they are attracted to women. Marriage provides the idiom for expressing the relationship between male spirits and female mediums, who are said to be each others’ spouses (vady). As will be described in further detail in chapter 7, tromba mediumship correlates with adult female status, marked by marriage and first pregnancy (which may or may not be carried to full term; see figure 7.1 and Appendix A).

Although the majority of participants at tromba ceremonies are female, tromba possession is not exclusively a female domain. The majority of mediums and observers at ceremonies are teenage girls and adult women, while the musicians and spirit interpreters (rangahy) are men. This division of duties along gender lines replicates what occurs at the royal tombs, where the saha for the most powerful royal tromba are female, and male tomb guardians (ngahy) who serve as the spirits’ interpreters when living royalty wish to consult them. (The significance of gender and the role of the rangahy will be discussed in more detail in chapter 7.)

Should a person show signs of tromba possession, she must accept it, for if she resists the spirit, it may cause her great physical harm. Most often possession is precipitated by an onslaught of chronic symptoms, including headaches, dizziness, persistent stomach pains, or a sore neck, back, or limbs. Typically, the victim has consulted a wide array of healers, including staff at the local hospital and indigenous healers, including tromba mediums, herbalist-healers (moasy), and diviners (mpisikidy). Eventually it is suggested to her that perhaps it is a tromba that is making her ill, the spirit being angry because she is resisting possession. The victim is then instructed to visit an established tromba medium in order to have the diagnosis confirmed. If it is indeed a tromba, she is expected to undergo an elaborate series of ceremonies in order to permanently install the spirit within her.

Once established, a tromba spirit remains active in the medium throughout her lifetime, and although it may become dormant once the medium has reached old age, the spirit departs only after she is dead. The spirit does not constantly reside within her. Instead, the spirit lives in the royal tomb, which it leaves temporarily in order to possess a medium; she in turn serves as a temporary “house” (trano) for the spirit whenever she goes into trance. When the spirit enters the medium’s body (or head, since it is often said “to sit” [mipetraka] here), her own spirit departs and remains absent throughout possession. After the possession experience has ended she does not remember what came to pass, so that a third party is required to serve as a witness or interpreter (rangahy) for her.[5]

One medium may have several tromba spirits, and often the older the medium the greater her spirit repertoire, since she collects increasingly powerful (and older) spirits as she herself ages. A medium can only be possessed by one spirit at a given point in time. Although the greatest royal tromba have only one saha each, the majority of tromba spirits are active in many mediums, and each can only be present in one medium at a time. In the past, when a medium became old or died, one of her daughters would usually inherit her spirits. (Lambek 1988b provides an excellent description from Mayotte of how children inherit their parents’ spirits.) Over the course of my fieldwork I knew of only one medium who had inherited her mother’s spirits. Instead I found that in Ambanja tromba possession often affects clusters of women who are friends or who are structurally related through kinship. Often these women are possessed by the same spirits. Special bonds defined through fictive kinship are established between mediums who share the same spirits or whose spirits are members of the same genealogies. Tromba possession affects a medium’s life in many other ways: in addition to being an important part of her personal experience, tromba spirits often become integral members of her household. As a vessel for them she may also become a respected healer in the community.

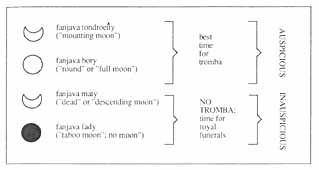

Tromba ceremonies are entertaining and suspenseful events. Spirits love music, and it is the lively sound of an accordion or stringed valiha[6] which generally alerts passersby to the fact that a ceremony is taking place inside someone’s home. The tunes of these instruments are complemented by faray, wooden rattles made of bamboo which are shaken and thumped on the floor to produce sophisticated poly-rhythms. These ceremonies are held for specific purposes: for a woman who is thought to have a new spirit; for the established spirits of a medium in order to introduce them to a new family member (such as a new child); or to show them a new house where the medium (and thus, the spirits, too) have moved. For these ceremonies the sponsor must spend much money for food, drinks, and payments for other mediums, their spirits, and for hired musicians (an accordionist or valiha player). These are often large-scale social events, sometimes attended by as many as twenty mediums (and their spirits), as well as kin, neighbors, and other friends. Tromba ceremonies generally begin in the daytime and run throughout the night and into the next day. The time when a tromba ceremony is held is chosen with care so as to fall within auspicious, complementary phases of the solar day and the lunar calendar.

Angeline’s Tromba Ceremony

Angeline is twenty and was born of Sakalava parents who live in a village thirty kilometers from Ambanja. She has been married to Jean (age twenty-nine) for two years. They met four years ago at the junior high school where she was a student and he was teaching French as part of his national service (required before continuing on to university). Jean is also from Ambanja and is the son of a Sakalava mother and Tsimehety father. His parents live in town, but are divorced. When Angeline and Jean informed their parents that they wished to marry, Angeline’s parents said she had to wait until she had finished her studies at junior high school; a year later Jean left for eighteen months to attend university in another province. During this time Angeline became very sick, possessed temporarily by an evil njarinintsy spirit, but she was eventually cured. She later finished her studies but had to repeat the final year. She did not pass the exam that would have enabled her to continue on to high school. Jean later decided to discontinue his studies at the university, and he returned to Ambanja to marry Angeline. He now works as a shift supervisor at a local enterprise. Since their marriage Jean and Angeline have lived in a small, neat two-room house made of traveler’s palm which was built on land that belongs to Jean’s maternal grandmother.[7]

Eight months after they were married, Angeline became ill again: she was weak, lost her appetite, and suffered from chronic stomachaches, dizziness, and periodic headaches. During this time she also became pregnant, but miscarried in the middle of her third month. Jean’s mother came and cared for her, cooking meals for Angeline and Jean. Being a tromba medium herself, she suspected that perhaps Angeline’s suffering was caused by a tromba spirit. It was not simply the chronic symptoms that led her to think that this might be true. She also suspected that, perhaps, it had been a tromba spirit that had given Angeline a njarinintsy because she was resisting possession. Jean’s mother finally decided to approach Angeline in private to see if she could learn more.

When she asked Angeline about her past experiences with possession, Angeline told her mother-in-law in a low voice that she had, in fact, been diagnosed as having a tromba. At first, when she had attacks of njarinintsy, friends and kin had told her parents that she needed to go to a tromba medium or other healer to have the spirit driven from her. Her parents are devout Catholics and did not believe in njarinintsy. When the doctor at the local hospital failed to cure her, however, they became very distressed and finally decided to do as others had suggested. A tromba medium was eventually able to drive out the njarinintsy, but suspected that Angeline also suffered from tromba possession. The medium said Angeline appeared to be possessed by a young baka atsimo tromba of the Zafin’i’mena descent group. Angeline’s parents had never arranged for the appropriate ceremonies, refusing on religious grounds to let their daughter become a tromba medium. They also feared that Jean would no longer wish to marry their daughter if he knew that she had a tromba spirit.

Angeline and her mother-in-law decided to approach Jean and explain the circumstances to him. He agreed to host a tromba ceremony (romba ny tromba). This ceremony is called mampiboaka ny tromba (“to make the tromba come out”), since it is at this time that the spirit makes its debut. When I later asked Jean what his reaction was when he heard the news he said, “I was surprised, but not upset—you see, I grew up with tromba, since my mother has several spirits. Although tromba spirits can be demanding, they are there to help the members of their households.” The greatest problem was finding the money to pay for the ceremony: it cost 95,000 fmg, the bulk of which Jean saved, with additional assistance from his mother and his maternal grandmother (Angeline did not work). The ceremony was postponed on three different occasions because royalty from different lineages had died throughout the course of that year, thus, “the doors [to the royal tombs] were closed” (nifody ny varavaran̂a), making it taboo to hold tromba ceremonies for several months. The tomb door was finally “opened” (nibian̂a ny varavaran̂a) in September, and the ceremony was scheduled to begin around 9:00 a.m. on a Saturday, when the phase of the moon was nearly full. Jean’s mother and maternal grandmother helped with the arrangements, and although Angeline’s mother did not attend, her mother’s sister, with whom Angeline had lived while a student in Ambanja, was an observer at the ceremony. Jean was also an important observer throughout the ceremony, since he would be introduced to his wife’s spirits. An implicit understanding was that he was there to begin to learn the role of rangahy or medium’s assistant.

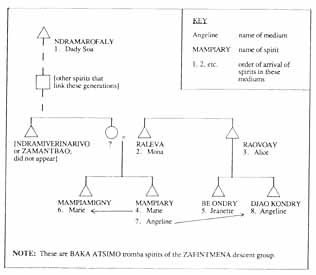

By 9:15 a.m. two men arrive, one bearing an accordion. These musicians have been hired to play music that will entice the spirits to come. They will take turns playing and will split the 5,000 fmg Jean will pay them. Five mediums have also been invited to attend; Jean will pay between 750 and 2,000 fmg for each spirit that has been invited to officiate at the ceremony, the amount being determined by the spirit’s stature (see figure 5.1). The first of the mediums to arrive at the house is Dady Soa, a woman in her early sixties. She is possessed by a powerful spirit named Ndramarofaly, and it is this spirit that will officiate at the ceremony. Dady Soa is accompanied by a man named Anton, who will serve as the rangahy or interpreter for her spirit. He, like Dady Soa, will be paid 2,000 fmg. No one knows Dady Soa personally, but she has been recommended to Jean’s mother by several friends as an accomplished medium. Within half an hour four other mediums arrive. These include two women in their forties: one named Mona, who is a cousin of Jean’s mother, and Alice, Mona’s friend. The other two are Marie and Jeanette, who were Angeline’s schoolmates and who are now her neighbors. All five mediums carry small baskets that hold the costumes for their respective spirits.

The mediums sit down in the house and face the eastern wall. This direction is associated with the ancestors and the location of the royal tombs.[8] Dady Soa occupies the northeast corner. Anton, her rangahy, is seated slightly behind her and to her left, and the other mediums are to her right. In front of the mediums is a short-legged table that Jean’s mother has set up to serve as an altar for the spirits. On this she has placed items needed to summon the spirits: an incense burner in which a piece of resin now burns, issuing a sweet aroma into the air; a plate holding water and crumbled kaolin (tany malandy); a small cup with more kaolin that has been crumbled and mixed with water to make a paste; several bottles that are painted with designs of white kaolin and which hold a mixture of burnt honey and water (SAK: barisa generally refers to the container; the contents is tô mainty/joby; HP: toaka mainty);[9] and an assortment of goods that will be given to the spirits to “eat” (mihinana) or consume. These include a small vial of honey, a small bottle of local rum, three one-liter bottles of beer and two others of soda pop, and two packets of cigarettes. Other similar supplies rest on the floor in a basket, waiting to be added to the table when needed. The mediums have already bathed before coming to the house, but Jean’s mother has placed a pitcher of water beneath the table for periodic hand washing and drinking during the cermony.

The house soon fills with other people. The two musicians sit to oneside, while Angeline, Jean, and Jean’s mother approach the front and sit next to the rangahy along the north wall. Friends and neighbors have also begun to assemble in the room. The majority are teenage girls and adult women, several of whom hold babies on their laps. Out of respect for the ancestors all present are barefoot, have their heads uncovered, and wear lambahoany, a body wrap that is an essential element of Sakalava dress. A dozen children crowd in the doorway and crane their necks inside the windows to watch the ceremony just inside.

When all are seated, the rangahy and mediums consult with Jean’s mother to review the reasons for why the ceremony has been arranged. Dady Soa, Mona, and Alice untie their knots of hair so that their long plaits hang down to their shoulders. This is a gesture they make in deference to the royal spirits that will soon arrive. They then assume a cross-legged position and, while facing east, they hold their palms up in deference to the ancestors; several members of the audience do this as well. The rangahy says the invocation (sadrana), asking the ancestors for their assistance. He first addresses the Zanahary, or Gods on High, and then those spirits who have been requested to attend this ceremony. As he does this, Jean’s mother hands him two 100-fmg coins made of nickel, which serve as an offering of “silver” (vola fotsy) for the spirits. The rangahy places these in the plate that is filled with water and kaolin. A musican then begins to play a lively tune on the accordion.

The atmosphere in the room is not calm, nor are the members of the audience austere. This is a time for excitement and rejoicing, for if the spirits are pleased, Angeline’s spirit will make its debut in her. When the musicians begin to play, one woman begins to sing and three others soon join her, while two additional women each pick up a rattle (faray) and beat out the rhythms of the tune. The time between the prayer and the arrival of any spirit is always one of great anticipation, for no one is ever sure how long the wait will be or if the spirit will come at all.

The first medium to go into trance is Dady Soa, and this she does with ease. She trembles slightly and then, abruptly, she stands. She is now possessed and has become the male spirit NDRAMAROFALY.[10] Jean’s mother jumps up to help this spirit, who draws his clothes from Dady Soa’s basket and begins to dress. As Jean’s mother holds up a cloth between Ndramarofaly and the spectators, the spirit drops Dady Soa’s waist wrap and puts on an old peasant-style white shirt and two tattered and faded pieces of red cloth, one of which he wraps around his waist, draping the other over his shoulders. He then sits down andwashes his hands. Then the rangahy hands him a wooden baton (mapingo) that is tipped with silver. Jean and his mother speak to the spirit with the assistance of the rangahy, who repeats what each party says. In this way the spirit learns why he has been summoned. Throughout this Angeline is silent. The spirit takes the plate of water and blesses Angeline by pouring a bit onto her head, and then pours some more into his palm, which he wipes on her face.

Tromba spirits are arranged hierarchically in relation to one another, according to their positions in the royal genealogies. The order in which they arrive at Angeline’s ceremony reflects these positions: the Grandparents (dady; dadilahy), who are the oldest and most powerful spirits arrive first, followed in turn by younger generations, the Children (zanaka) and Grandchildren (zafy). Thus, Ndramarofaly, who is the most powerful spirit to attend this ceremony, must arrive before other mediums can enter trance. Now Mona and Alice begin to draw on their bodies with kaolin paste. These markings designate which spirits will arrive in them. Alice also ties a white cloth around her chest. Within a few minutes both of these mediums show signs of possession. First their bodies shake violently, then Mona begins to shake only her head, and then she falls on her belly, with her hands behind her back. Alice, meanwhile, begins to hiss, holding one trembling arm outstretched before her. She, too, falls on the ground, and then they each draw a white cloth over their bodies and heads. Two other young women come to their aid, helping them to rise and dress and shielding them with draped cloths. They emerge as two brothers, RAOVOAY (“Crocodile Man”) and RALEVA, who are both young affines of Ndramarofaly. These are the spirits of royalty who served under the colonial administration and their clothes reflect a European flair: in addition to a small baton and a red-print lambahoany waist wrap, each wears a white, four-pocketed shirt and a fedora.

Upon arriving these spirits must greet their elder, and so they approach Ndramarofaly and put their heads on his lap. He then blesses them by placing his hand on their heads. While Grandparents like Ndramarofaly remain calm and somewhat detached throughout tromba ceremonies, younger spirits interact with the living. Typically, a Child or Grandchild will light up a cigarette and then greet members of the audience with a special tromba handshake; this is just what Raovoay and Raleva do.

Again, the spirits confer. All wait and watch Angeline, who now sitscalmly behind the spirits. She has recently untied her long, braided tresses and they now hang down onto her shoulders and back. She sits cross-legged and has a lambahoany draped over her shoulders. The music continues, people chat, and children come in and out of the room. Still, nothing happens.

An hour later one of the two youngest mediums, Marie, starts to go into trance. Grunting, she violently spins her head from side to side, so that her tresses fly. A young woman runs to grab her: first she smears white kaolin along Marie’s jawbone, and then she wraps a towel firmly under her chin and up over her head. All know by now that this is the spirit of MAMPIARY, the cowherd and the son of Raleva, who is trying to make his entrance. When this spirit died he broke his jaw, and so when he arrives the medium’s head must be supported so that she will not be injured in a similar way. The young woman holds Marie, who is kneeling and whose body begins to jerk while her head moves up and down. Meanwhile Jeanette has drawn lines of white kaolin on the backs of her fingers, hands, and up her arms, and she now begins to box the air. When members of the audience realize she is aiming for one wall, they laugh and nervously jump away, while Jean’s mother quickly smears kaolin on the wall. Just as she withdraws, Jeanette strikes the wall with her fists and falls—she is possessed by the boxer, BE ONDRY (“Big Fist”), who is the brother-in-law of Mampiary (see plate 4). Marie and Jeanette, possessed by their respective spirits, each stand and dress. Their clothes are similiar to those of Raovoay and Raleva: they, too, wear lambahoany, although Marie’s is green and Jeanette’s is orange, and they wear boater or panama hats. Once dressed, they greet the other spirits and then turn to the audience and playfully shake each person’s hand. Mampiary also jingles a collection of bottle caps that he has in one of his pockets. Although in appearance these two Grandchildren resemble the Children who are their elders, they are playful and reckless in their actions. These two spirits speak in high voices, and throughout the ceremony they will drink, smoke, and dance with members of the audience. When clowning Grandchildren are present, it is the dead who are the life of the party.

These five spirits will play important roles during Angeline’s ceremony, having been summoned because her spirit is believed to be a member of their lineage (again, see figure 5.1). These spirits appear frequently in Ambanja, each possessing mediums of ages that correspond to those present at Angeline’s ceremony. Throughout this ceremony other spirits will arrive and depart in these and other mediums, so that any medium may undergo a series of transformations, changing personae as different spirits arrive and depart in her body. Since tromba spirits are powerful healers, passersby may also drop in and request their services. Most of these clients are adults who bring small children by for treatment. Periodically there are breaks in the ceremony; at these times the musicians pause to rest or to eat with members of Angeline’s household. Anyone else who is present will be invited to join them. Sometimes mediums leave trance so that they can eat, but more often they refrain, remaining possessed throughout the ceremony.

4. Medium entering trance. The medium is making two fists, which indicates she is about to be possessed by one of the boxer spirits, Djao Kondry or Be Ondry.

Once these five spirits have assembled, all attention is again focused on Angeline in anticipation of her spirit’s arrival. Occasionally she shows signs of possession, shaking and moaning, but she only collapses, exhausted, on the floor. These moments are tense and exciting. The musicians, anticipating the spirit’s arrival, play faster, and the beat of the rattles grows harder and louder. Women also begin to ululate or sing loudly, hoping to excite the spirit and encourage it to arrive. Each time, too, the younger spirits run quickly to Angeline’s aid, holding her up, consoling her, and asking her spirit to be kind to her and arrive smoothly and quickly. This continues throughout the afternoon and into the night, but still her spirit does not arrive. When she shows signs of fatigue following fits of partial possession, the spirits have her drink from the plate of water, or they wipe her face and arms with kaolin paste: both have healing properties because they are cool (manintsy) and because they are sacred, being associated with the spirits. The spirits and a number of observers begin to suspect that Angeline may be possessed by Mampiary since, at one point, when Marie was temporarily possessed by another spirit, Angeline waved her head up and down when showing signs of possession. Mampiary is instructed by Ndramarofaly to leave Marie, who then becomes possessed by another spirit, MAMPIAMIN̂Y (“Limpness”), Mampiary’s brother. His style of dress is slightly different: he wears a purple cloth that is similar to Ndramarofaly’s and a shirt and hat like that of the Children. Also, unlike Mampiary, he is quiet, sitting limply on the ground at the front of the room. By this time Angeline is exhausted and she retires for an hour to the bedroom next door.

5.1. Spirits and Mediums Present at Angeline’s Ceremony.

Around dawn Angeline’s spirit finally arrives. This is the moment of the day that is, in J. Mack’s words, “the most auspicious time in the Malagasy calendar” (1989). Since the spirit is making its debut in Angeline, it is important that it be identified, stating its name and position in one of many genealogies. In this way its relationship to other spirits and to Angeline can be determined. Possessed, Angeline is brought to the front of the room to consult with Ndramarofaly and the other tromba. After much discussion, her spirit finally utters its name: it is, indeed, MAMPIARY. A series of additional conferences are then held, involving Ndramarofaly, the rangahy, and members of Angeline’s household.

The arrival of the long-awaited spirit is the climax of the ceremony. The neophyte may remain possessed for less than an hour, her spirit quickly departing, or her spirit may stay and enjoy the celebration, clowning with other spirits and members of the audience. In Angeline’s case, it leaves quickly, but soon she shows signs of being possessed by yet another spirit. She assumes a boxing position, and at this time others prepare her in the same way as was done for Jeanette. Angeline suddenly hits the wall with her fists, collapses, and then sits up. The spirits and her kin confer and determine that Angeline is possessed by a second spirit, DJAO KONDRY (“The Guy Who Boxes”), the brother of Be Ondry.

After this second spirit departs from Angeline, the ceremony is nearly completed. The spirits that remain must depart in an order that mirrors their arrival, the youngest leaving first, the most powerful departing last. Angeline’s ceremony lasts for another hour because Be Ondry refuses to leave until Jean has bought him yet another bottle of beer. Since it is early in the morning, Jean has to wait for a nearby store to open before he can send a child to purchase a bottle for the spirit. Be Ondry guzzles this down, and then he is cajoled into leaving by the other, more powerful spirits. He finally agrees to leave so that other spirits may follow. Each spirit leaves in a style similar to the way it arrived. As the younger and more active spirits depart, unpossessed members of the audience run to catch each medium, massaging her arms and back with quick slaps and jerks in order to relieve her somewhat of the pain and stiffness she will feel afterward. All mediums are in a daze when they reenter their own bodies and they ask for a summary of what happened, since they do not recall what came to pass. Although they are tired, they do not feel the effects of any alcohol they consumed.

This ceremony will be followed by another equally expensive ceremony called manondro ny lamba (“to give the clothes”), when the spirits will be presented with their appropriate attire and they will be given items they like to eat. For Mampiary and Djao Kondry these goods are beer and cigarettes. They also will be properly introduced to Jean, since he is a member of Angeline’s household, and they will be paraded seven times around the courtyard of the house. Anytime that a major change occurs in Angeline’s life—if she bears a child, or if she moves to another residence, for example—she must hold a ceremony to officially inform her spirits of this. Since these ceremonies are expensive, mediums are often forced to postpone them for a year or more until they can assemble the necessary capital or gain the assistance of kin to help pay for the ceremony. Postponement is dangerous, however, and causes the medium much anxiety, since her spirit may become angry with her and decide to harm her or others close to her. Throughout her life she may accumulate several other spirits, and generally the stature and power of these new spirits increase as she herself ages. If she wishes, she may participate in similar ceremonies held for other neophytes.

In addition to the large-scale ceremonies such as the one described above, many established mediums work alone at home, holding private sessions, by appointment, with clients. These ceremonies are more austere than the larger, public ceremonies, and they are always held in a quiet and dark room. They are attended by the client, the medium and her assistant or rangahy (who is usually her husband, although it may be a woman who is a friend or a relative), and, perhaps, an assortment of other observers such as friends or kin of the medium or client. In addition to prearranged ceremonies, tromba spirits occasionally arrive suddenly and unannounced. This almost always occurs when the spirit has been angered, either by the medium or by someone who is close to her.

| • | • | • |

Other Members of the Spirit World

The spirit world of Ambanja is complex and varied. Tromba are by far the most important spirits. It is they who appear most frequently in mediums and who are most significant in terms of daily interactions between the living and the dead. As the spirits of Sakalava royalty, structurally they are also of prime importance. Although tromba dominate the spirit world, they can not be understood fully unless explored in relation to other spirits.

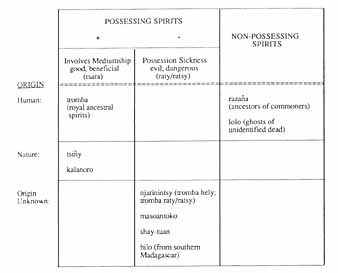

5.2. Spirits of Ambanja.

In Ambanja, spirits are categorized in a number of different ways (see figure 5.2). They may be grouped according to their origins and by human or nonhuman qualities. In addition to the tromba, who are royal, historical figures, there are also the ancestors of commoners (razan̂a), ghosts of the lost dead (lolo), nature spirits (tsin̂y and kalanoro), and a variety of lesser, amorphous, evil spirits (njarinintsy, masoantoko, shay-tuan, bilo). Although all spirits are potentially dangerous, spirits generally are grouped by Sakalava as being either good (tsara) or bad (raty, ratsy).

Mediumship also provides a means by which to group spirits. Just as tromba spirits require mediums, so do the nature spirits tsin̂y and kalanoro. All spirits are potentially dangerous, especially when angered, but spirits that work through professional mediums are regarded as being, in general, benevolent. In Sakalava cosmology, the Zanahary, or Gods on High, are distant and vaguely conceived creator spirits or dieties to whom the living do not give much thought. Ancestral spirits especially serve as intermediaries between the living and the Zanahary. (In Malagasy Christian theology, the Zanahary have been replaced by the Christian God, Andriamanitra, or “the King of Heaven”; sometimes Catholic mediums will address this God instead when they invoke tromba spirits.) Although nature spirits that require mediums are feared, they, like tromba, are respected as authority figures and as specialists in times of crisis. They are also revered as knowledgeable healers.

Finally, positions and meanings assigned to spirits within the Malagasy cosmos are further manipulated, restructured, and redefined through the doctrines of Christianity and Islam. In these contexts, all spirits are considered to be evil and are referred to as devils or jinn (devoly, jiny). Values collide in the realm defined by the spirit world, as devotees of Christianity and Islam (as well as urban intellegentsia and foreigners) struggle to make sense of the pervasiveness of Malagasy customs (fomba-gasy) in light of their own beliefs based on alternative moral and ideological systems (this will be elaborated in chapter 10).

Other Spirits of Human Origin: Razan̂a and Lolo

Like royalty, Sakalava commoners have their own personal ancestors (SAK: razan̂a; HP: razana; the latter term is used throughout Madagascar for ancestors), but, in contrast to tromba spirits, razan̂a do not possess mediums (cf. Rason 1968).[11] Instead, they communicate with the living either through dreams or through a third party, such as a tromba medium, whose spirit, in turn, serves as an intermediary and interpreter.[12] These spirits interact with the living when they are angry or troubled and must be appeased when necessary. An angry razan̂a may also be identified by a healer as the cause for an individual’s sickness or misfortune. They sometimes disturb the living because their bodies have been lost or forgotten. For example, an ancestral spirit may be angry because it has long been dead and its burying place forgotten, or because it was never placed in the family tomb. Reasons for this may vary. Perhaps the person died while traveling, or the body was never recovered, or the body was intentionally neglected, left to rot somewhere in the woods because of a major trespass committed in life.[13] The healer, most often a tromba medium, will then instruct living kin how to placate the troubled spirit, explaining where to find the remains, or what other actions the ancestor wishes its kin to take. Personal ancestors are also honored annually on the Day of the Dead (Fety ny Maty), since many Sakalava in Ambanja are Catholic.[14]

Lolo (pronounced “lu-lu”) is a term used throughout Madagascar for ghosts. These are, in essence, orphaned spirits with no structural ties to anyone. They are similar to razan̂afa, the difference being one of perspective. Razan̂afa are one’s own lost ancestors; lolo, on the other hand, may be seen as the lost ancestors of strangers: they bear no structural affinity to those whom they disturb.[15] Lolo are the ghosts of people who have died in tragic or violent ways, whose bodies were never recovered and placed in a tomb. Lolo haunt the scenes of past accidents, such as regions of the sea where people have drowned or under bridges where there have been automobile accidents. These are jealous and vicious spirits that cause their victims to die in ways similar to their own deaths. For example, the sea near the east coast town of Toamasina is very rough, and it is said that many lolo dwell there. Similarly, people crossing the channel between Nosy Be and the main island often fear that the ghosts of those who drowned in boating accidents will cause them to meet similar fate.

The theme of lost bodies is a common one in Madagascar. As Bloch (1971) has shown, it is in the tomb that Malagasy invest the greatest amount of money and sentiment, for it is the tomb that defines where home is, tying the individual to past, present, and future kin. A lost body is very frightening, and Malagasy tell elaborate tales of trying to recover and transport the body of a loved one who has died far from home, either in a remote part of Madagascar or abroad. During the course of my interviews with an old Sakalava man he told me I should move out of my house because there were lolo living there, since it was built, along with the neighboring Lutheran church, on top of an old Sakalava cemetery. One of my assistants and I later challenged him on the truth of this story (topographical records revealed that a cemetery had in fact existed near the church, but not on its grounds). He later retracted his statement and agreed that it was unnecessary for me to move. I believe that his statement had much to do with my needing to clarify for him my relationship with the Lutheran church, which was not particularly popular with the Sakalava.

Nature Spirits that Require Mediums: Tsin̂y and Kalanoro

In addition to tromba, there are two categories of nature spirits that also possess mediums. These are the tsin̂y and kalanoro. A tsin̂y is a nature spirit associated with a specific location where it is said to live, such as a sacred tamarind tree (madiro) or a rock. Tsin̂y, when they possess their mediums, wear clothes that are similar in appearance to Zafin’i’fotsy tromba. In addition to being periodically possessed by their spirits, tsin̂y mediums also serve as the exclusive guardians or caretakers of the spirits and their habitats, so that a tsin̂y medium is said “to have a tsin̂y” (misy tsin̂y, lit., “there is a tsin̂y”). This issue of guardianship is important. Since a tsin̂y’s dwelling is sacred, people may wish to leave offerings for the spirit without actually consulting with it directly. In order to do this, however, one must acquire permission from the spirit’s guardian. The location of a tsin̂y is easy to recognize, since it generally has a fence built around it for protection, and pieces of white cloth, left as offerings, will be draped on a pole or, if it is a tree, a branch. Unlike tromba, tsin̂y possession is not widespread in Ambanja. Tsin̂y locales and mediums are few and are located in small villages throughout the countryside.

Kalanoro are by far the most mysterious, frightening, and bizarre (hafahafa) of the Malagasy spirits, having a quality that Kane (1988) aptly describes as “surreal” in speaking of the duende spirits of Panama. Kalanoro are found throughout Madagascar, and in other regions of the island they go by such names as kotoky and vazimba.[16] Kalanoro are rarely seen, because they live deep in the forest. They are short and some informants say they have long fingernails and red eyes. Their hair is long and possesses magical qualities. I know of one moasy (herbalist), for example, who derived his power from a small packet of magical substances which included kalanoro hair. The most striking aspect of kalanoro is that their feet point backward, so that if one wishes to track a kalanoro, it is important to remember to follow the footprints in the direction they appear to be coming from, rather than where they seem to be going. Kalanoro eat raw food and may leave evidence of a meal—such as the cracked shells of a crayfish on a rock in the middle of a river.

As is true of tsin̂y, kalanoro mediums are said to have or keep these spirits and act as their guardians. Unlike tromba and tsin̂y possession ceremonies, however, the client is not permitted to view a kalanoro when it possesses a medium. Instead, during the consultation, the medium sits behind a white curtain in a darkened room. There are only a few kalanoro mediums working in the Sambirano Valley, and they, like those with tsin̂y, live out in the bush. Although I was never able to consult a kalanoro, I was told by informants who had done so that when the kalanoro arrives it can be heard walking and banging on the ceiling and walls of the house and that its speech is quick, choppy, and high pitched, so that it is difficult to understand. It is taboo to have a dog present during a kalanoro seance, because dogs can see them. Malagasy are generally wary of kalanoro because of their strange qualities. The few informants I knew who had consulted kalanoro did so either out of curiosity or as a last resort after the efforts of numerous tromba mediums and other healers had failed.

Although tsin̂y and kalanoro are similar to tromba spirits in that they operate through mediums and work as healers, they differ in a number of ways. First, kalanoro and tsin̂y are associated with nature, and so many of their clients seek their assistance because of a trespass they have committed against such a spirit by violating a sacred locale. Second, the mediums for these nature spirits serve as their guardians and, thus, each spirit is only associated with one person, whereas a tromba spirit may possess many mediums. Third, they are much rarer. Over the course of a year, I met only three tsin̂y mediums, and I was never able to locate a kalanoro. Because of this, their services are usually more expensive than those of tromba mediums, which accounts in part for why they are a last resort for clients. Fourth, although the majority of tromba spirits possess women, kalanoro guardians are men and women. Tsin̂y possession, on the other hand, appears to be more common among men: of the three tsin̂y mediums I encountered during one year, only two of these were male. Finally, whereas tromba possession occurs in the context of large-scale ceremonies, tsin̂y and kalanoro work in the privacy of the guardian’s home.

Evil Spirits

Njarinintsy, Masoantoko, Shay-tuan

All spirits that operate through mediums—tromba, tsin̂y, and kalanoro—become permanent fixtures in their mediums’ lives. There are also evil (raty, ratsy) possessing spirits—njarinintsy, masoantoko, and shay-tuan—which are harmful and are often regarded as a special form of possession sickness. These spirits are said to be recent arrivals to the Sambirano region.

Of these malevolent spirits, njarinintsy are the best known and claim the greatest number of victims. For this reason njarinintsy will be the focus of subsequent discussions of possession by evil spirits (see especially chapter 9). Njarinintsy possession is a relatively new phenomenon in Ambanja, occuring only within the last fifteen years. Most informants say that they first heard of njarinintsy in the 1970s, and Sakalava argue that it was brought by Tsimihety migrants. Cases of njarinintsy are reported from other areas of the north as early as the 1960s and informants describe these as clowning spirits. In more recent years, however, njarinintsy have become increasingly violent. Njarinintsy possession is viewed as a grave illness with symptoms that include shaking and chills (this is reflected in the spirit’s name, which is derived from manintsy, which means “coldness”);[17] uncontrollable screaming and crying; loss of memory; and mental confusion. As with tromba possession, the majority of njarinintsy victims are female. They experience temporary fits of possession or madness when they wander the streets aimlessly and may even, in extreme cases, attack people. If an individual is in a possessed state she does not recognize anyone, nor will she remember what happened once the fit has ended.

Sakalava often speak of njarinintsy in reference to tromba. Njarinintsy may be viewed as structurally akin to tromba, for it is sometimes said that they are the “children of tromba” (tsaiky ny tromba, zanaka ny tromba). They are also referred to as tromba hely (“little tromba”) or tromba raty/ratsy (“bad tromba”). Informants insist, however, that njarinitsy are not a type of tromba for, unlike tromba, njarinintsy are malicious and extremely dangerous, and must not be allowed to inhabit the living. In many ways these spirits are defined in opposition to tromba—they are everything that tromba are not.[18]

Masoantoko and shay-tuan are very similar to njarinintsy, and so I will describe them only briefly. A masoantoko (lit. “group of eyes” [?] from maso, “eye,” and antoko, “group”[?]) disturbs its victim while she sleeps, giving her terrible nightmares. Informants opinions on shay-tuan differ, particularly in reference to their origin. Some informants say they are Chinese spirits, referring to the local spelling of the name, but others say they are Muslim. More likely they were brought to Madagascar by slaves or Swahili traders from East Africa (compare with the Arabic term shetwan, for “devil”; setoan in Feeley-Harnik, 1991b: 95; also sheitani spirits of East Africa, see Giles 1987; Gray 1969; Koritschoner 1936). According to one informant, shay-tuan smell bad (maimbo). Odors can be important in distinguishing different categories of spirits from one another. Tromba, for example, can be enticed into arriving in a medium by burning sweet smelling resin or other types of incense. Shay-tuan (and lolo, see above), however, can be driven from a room by burning the same type of incense or a piece of cloth. For this reason adults often burn one of these substances in a room before children enter it to sleep at night.

Bilo

A final form of possession sickness found in Ambanja is bilo. Bilo does not occur with great frequency in Ambanja, being an affliction primarily of peoples who have come from the south, such as the Betsileo and Antandroy. The symptoms associated with bilo are much like njarinintsy in that its victims may become violent and temporarily crazed. Some bilo spirits are animals, such as snakes, and they cause their victims to crawl on their bellies while they are possessed.[19]

Responses to Possession Sickness

The responses to possession involving evil spirits—njarinintsy, masoantoko, shay-tuan, and bilo—reflect the gravity of the situation and the necessity for collective action. In Malagasy communities, individual illness is a time when kin and close friends congregate to care for, watch over, and socialize with the afflicted. This is especially evident in cases involving spirit possession. Tromba, tsin̂y, and kalanoro require that the individual go through a series of ceremonies to instate the spirit permanently within her; in contrast, an evil spirit must be driven from its victim. If it is not, she may become increasingly ill and may even go mad or die. When an evil spirit strikes, the assembled group provides not only a united front against the spirit, but also helps to give the victim strength to resist possession. The presence of kin ensures that the afflicted will be taken to a healer. Furthermore, she has witnesses to the entire process. This is, I believe, essential: regardless of the type of possession, the possessed is never aware of what happens when she is in trance, and so part of the healing process involves the recounting of events to the victim (see Lambek 1980 for a similar discussion from Mayotte).

Possession sickness involving evil spirits most often affects adolescent girls between the ages of thirteen and seventeen, and many tromba mediums and other healers specialize in exorcising these spirits. Malicious spirits generally do not possess their victims through a will of their own but have been sent by an adversary, who has used magical substances or bad medicine (fanafody raty/ratsy) to harm someone. The victims of evil spirits are those who have come into contact with fanafody that was meant for them or, in some cases, through accidental contact with fanafody that was meant for someone else. As the case of Angeline shows, they may precede tromba possession, the evil spirit having been sent by a tromba to harm a woman who is resisting mediumship. In these cases, once the evil spirit is exorcised, the tromba then makes its debut.

Although njarinintsy possession is a grave illness, if a cure has been successful, long afterward kin and friends will tell lively, comical stories of the problems encountered in trying to restrain the possessed and keep her calm during transportation in an oxcart or taxi and, finally, what came to pass with the healer. Njarinintsy are, in general, uncooperative and demanding spirits. The role of the healer is to strike a bargain with the spirit, making arrangements to give gifts to it or later to leave certain goods in strategic locations—by a sacred tree, for example—so that the spirit will be content and will leave the victim. This process is not always successful. It may take several visits to a number of different healers before the spirit agrees to leave. The process is further complicated by the fact that njarinintsy do not always appear alone, for they are said to prefer working in groups of seven. Thus, even if one spirit is driven away, there may be others that remain inside the victim. Once the spirit or spirits have departed, the individual is cured. A failure to cure is a grave matter, for the person will continue to have fits, and it is said that she may be driven mad or even die from the harm caused by the presence of the spirit. If indigenous healers fail to coax an evil spirit from its victim, her kin might then go to a Protestant or Muslim exorcist.

Most Christians and Muslims in Ambanja state that they are opposed to possession. According to Christian doctrine, all spirits are considered to be devils (devoly). Although the Catholic church in Ambanja is fairly tolerant of possession activities, Protestant churches in Ambanja (and in other regions of Madagascar as well) are actively involved in exorcism activities. The FJKM, Lutheran, and a number of other churches have a long tradition of specialists called fifohazana (HP, from the verb mifoha, meaning “to wake” or “to arise”) or mpiandry (“shepherds”) who exorcise tromba and other spirits through the power they derive from the Holy Spirit. Under Islam, all spirits are similarly regarded as being jinn (SAK: jiny), and, like the Protestant churches, a number of Muslim sects in Ambanja also have specialists who are able to exorcise them. Tolerance of possession varies from one Muslim sect to another, and attitudes toward possession often depend on how troubled the victim is. Rarely do kin seek help from Protestant exorcists and only in extreme cases. (This alternative form of therapy will be explored in chapter 10.)

Thus, tromba and other forms of possession now form a vital part of daily life in Ambanja. The social, demographic, economic, and political forces outlined in Part 1 have led to the popularization of tromba. As the chapters that follow will show, tromba provides Sakalava with a means to reflect upon their shared experiences and to document, reshape, and constantly redefine relationships with peoples of diverse origins. In turn, since tromba possession continues to be viewed as a Sakalava institution, it enables tera-tany to regulate the participation (and thus incorporation) of outsiders. For vahiny, it provides them, too, with a powerful vehicle to express their own experiences within the context of migration, and with a means of integration into the local community. In these ways, possession in Ambanja is an important aspect of both collective and individual identity.

Notes

1. Authors generally refer to tromba as being the spirits of Sakalava princes. This is, however, misleading, since both male and female members of royal lineages may become tromba. Throughout the province of Diégo (Antsiranana) there are a number of well-known female tromba: for example, the royal Bemazava lineage has several female spirits. The term prince is misleading as well, because it implies not only the absence of princesses, but also of kings and queens. For these reasons I prefer to use the term royalty when referring to rulers and other members of their lineages.

2. Tsiaraso III, who is the present Bemazava king, does on occasion visit Nosy Faly.

3. Atsimo is the name of the tomb in Mahajanga province in which these royalty are entombed (Ramamonjisoa, personal communication). Some informants also say that the name is derived from tsimo, which means “wind.” The term refers to the idea that tromba are out in the air when they are neither in the tomb nor in a medium.

4. In Ambanja, early June is often a time of much tromba. Following this, however, are “taboo months” (fanjava fady) for certain categories of spirits: mid-June to mid-July is fady for Bemihisatra spirits, and the period from mid-July to mid-August is fady for the Bemazava. These taboo months are associated with times when royal work (fanampoan̂a) is being performed at their respective tombs. Since this period is associated with death and danger, it is said that the tomb “door is closed” (mifody ny varavaran̂a) so that the royal spirits may not leave and possess the living. Similarly, tromba possession is also forbidden during any month when a member of the royal family has died. The month when the door is once again open (mibian̂a) is August (Volambita). Finally, if there is an eclipse, no tromba possession may occur during that month.

5. In this study, I wish to distinguish between spirit possession and trance, the former referring to the experience as it is socially defined and constructed, the latter describing the physiological changes felt by the medium. In other words, possession refers to Sakalava perceptions of the spirit, as it takes control of the medium’s body, and trance refers to the medium’s altered state of consciousness. I am not certain if all of the mediums I observed actually entered trance (Sakalava stress that there is “fake” tromba: tromba mavandy or “tromba who lie”), but since trance is assumed by Sakalava to be part of the medium’s experience I, too, will assume that the majority experienced this altered state of consciousness.

6. A valiha is a type of zither made from a large piece of bamboo. It is held vertically in the lap and the strings are plucked with the fingers and thumbs. It is unusual to find a valiha player at a ceremony in Ambanja, since today there are very few musicians in the area who know how to play this instrument.

7. Students in Ambanja and other coastal areas lag behind highland children in their schooling; it is not unusual for junior high school students to be in their late teens and for high school students to graduate when they are in their early twenties. In addition, Angeline’s experience with njarinintsy possession typifies that of many adolescent schoolgirls. These topics will be discussed in chapter 9.

8. According to compass direction, the closest royal tombs are at Nosy Faly and lie north of Ambanja. The spirits who appear at Angeline’s ceremony all come from tombs in the south (boka atsimo), near Mahajanga.

9. As Feeley-Harnik explains, this is a form of mead used at royal celebrations and to cleanse filth associated with death or wrongdoing (1991b: 594).

10. Spirits’ names appear in capital letters to designate when they arrive.

11. Tromba, of course, as royal ancestors, are also razan̂a. To avoid confusion, I will use the term razan̂a only when referring to the ancestors of commoners.

12. Lambek (1981: 70ff) refers to this as the “communication triad” of possession, which involves the sender (host or medium), the receiver (spirit), and the intermediary (others with whom the spirit converses).

13. One informant stated that in the past individuals with leprosy could not be placed in the family tomb. I am not sure if this was true, since the disease does not appear to be stigmatized today.

14. Non-Sakalava Protestants, too, honor their dead at this time but, as I heard a Lutheran pastor stress during a sermon, they were not to leave goods such as honey or rum at the gravesites to feed the dead, since this is a pagan Malagasy custom (fomba-gasy). They could, however, leave flowers or candles to honor them.

15. Feeley-Harnik describes lolo as spirits who have not achieved ancestor status (1991b: 405); see also Lombard’s discussion (1988: 117ff). Astuti (1991) reports that among the Vezo lolo means “tomb” and it is thus equated with known ancestors.

16. For the Highland Merina, vazimba are the spirits of the little people who are said to be the island’s original inhabitants. See also Lombard (1988: 17) on the southern Sakalava of Menabe.

17. The term njarinintsy is often capitalized; since there is not one but a multitude of njarinintsy spirits I have decided not to capitalize this term in the text (compare, however, Sharp 1990). Feeley-Harnik translates Njarinintsy as “Mother Cold” while my informants in Ambanja defined it as “The Fellow/The One who is Cold.”

18. Among my informants, however, a few were skeptical about this structural affinity to tromba; these tended to be members of the Bemazava royal lineage. They stated that more recent tromba spirits, such as Mampiary, Be Ondry, and Djao Kondry are not tromba spirits but simply njarinintsy who have taken names and who are trying to achieve royal status. According to Feeley-Harnik (1991a: 88), “be hondry,” like njarinintsy and “masantoko,” is an evil spirit (lolo) who possesses in order to kill.

19. Heurtebize (1977) has described this form of possession among the Antandroy. He reports that a decade ago Antandroy sometimes returned from the north with a new form of possession, called doany, which means “tomb,” but by 1987 doany possession was rare (Heurtebize, personal communication). See also Lombard’s description of bilo among the southern Sakalava of Menabe (1988: 17). Finally, for an intriguing discussion of bilo and economic change among the Masikoro see Fieloux and Lombard (1989).

6. Sacred Knowledge and Local Power: Tromba and the Sambirano Economy

In the Sambirano, power, authority, and independence hinge on access to and control over land. At first glance it may appear as though it is outsiders (first, French and, more recently, highland Malagasy) who exert the greatest control in the valley, since throughout this century they have been the managers of the plantations and now the enterprises. In this region, much local power lies, however, with those most familar with and integrated into its institutions: these are the Sakalava tera-tany. Managers rarely occupy their positions for more than a few years and so their influence is limited. Sakalava maintain long-term control over important social, economic, and political arenas since they outnumber other groups; occupy the majority of elected positions; own the greatest number of private landholdings; and define the thrust of local culture. The final factor is significant because shifts in national policy in the early 1970s have underscored the necessity of showing respect for local custom, and so today outsiders find they must maintain a delicate balance with the Sakalava tera-tany if they are to accomplish their goals.

This chapter will explore the manner in which Sakalava collectively view and interpret local power and, in turn, how they maintain their influence in the valley. As will become clear, the power of tera-tany hinges on their ability to resist capitalist relations and to undermine or manipulate the future development of the region by the state. In order to fully comprehend this process, it must be explored from a multitude of angles. First, social cohesiveness is an essential element: among the Sakalava this is defined through the ancestors, the concept of a shared historical past, and the occupation of a common territory, their tanindrazan̂a (cf. Keyes 1981). For the Sakalava, like other Malagasy, these domains of time and space are sacred. Since these contexts are defined by the actions of royal ancestors, tromba spirits are an essential element of local custom and identity.

Second, as the studies of such authors as Comaroff (1985), Nash (1979), and Taussig (1980a, 1987) show, ritual may be rich in symbolism that reveals an indigenous awareness of the disruptive and alienating nature of development. The symbolism associated with tromba serves to record, reorder, and critique collective experiences that occur under drastic economic development. In essence, tromba possession rituals operate as a form of ethnohistory, providing an arena in which to retell and reflect upon relations with non-Sakalava.

Third, and perhaps most significant, tromba possession goes beyond critique: it also empowers the Sakalava of the Sambirano. Apter (1992) has argued that, in the context of Yoruba religion, ritual knowledge and power may be intrinsically linked and may ultimately challenge the political order on a national level (cf. Lan 1985). Tromba spirits (through their mediums), embody sanctioned ritual authority, occupying pivotal positions that affect power relations in the Sambirano and the subsequent development of the landscape of the tanindrazan̂a. Such authority affects not only individual experience but also directs collective reponses to the state. Through popular tromba, individual mediums may manipulate their actions in the context of labor relations, while the saha of Nosy Faly control the actions of outsiders and monitor economic changes that disrupt the order of the local sacred geography as a whole.

| • | • | • |

Tromba as Ethnohistory