TWO—

MAKING IT STRANGE

Literary versions of the Carnival-Lent allegory generally include five segments: presentation of characters, preparation for combat, negotiations between the parties, a battle or lawsuit, and the consequences of the conflict. In Rabelais's episode nearly all the narrative is concerned only with the first two phases, and in this his work is similar to other sixteenth-century examples of the theme.[1] Beyond this, however, he parts company from everyone else by means of three devices that bend the old pattern to the breaking point.

The first deviation is to substitute a descriptive for a narrative approach to his characters. Instead of telling what Quaresmeprenant does — the usual staple of popular tales — Rabelais's narrator describes what Quaresmeprenant is like from different points of view, physical, moral, medical, and metaphysical. The narrator is always Xenomanes, the world traveler, and his audience is Pantagruel and his friends. After and during some of the descriptions the travelers make comments that, instead of unifying the different perspectives offered by each successive description, render those perspectives more perplexing. Bewilderment about the overall nature of Quaresmeprenant seems to augment rather than diminish with the addition of details. Meanwhile, because the monster is at a distance from those discussing him, remaining somewhere on Tapinos Island, which has already been passed by Pantagruel's ships, he becomes more and more imaginary, a creature in people's minds rather than an element of narrative action.

Second, Rabelais breaks the traditional pattern in two by separating his discussion of a Lent-like monster called Carnival from his account of carnivalesque Sausages who resemble Lenten eels. Between the two comes an account of Pantagruel killing a huge "physeter" (Greek, "spouter," adapted to Latin form by Pliny). Why does Rabelais introduce this incident? At the story-telling level it is an adroit move because

[1] Grinberg and Kinser, "Combats," 66–69, 81.

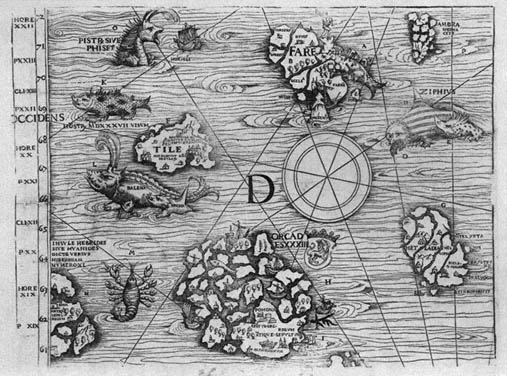

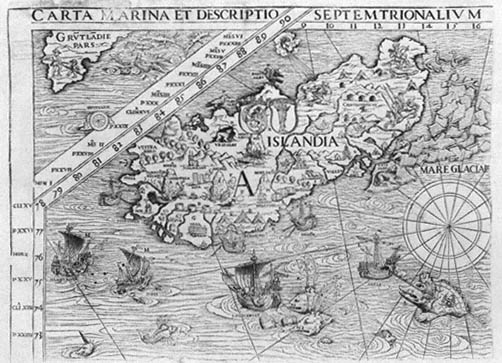

it breaks the tension built up through the static, suspended descriptions of a figure whom one never sees. It is also appropriate to the tenor of the Fourth Book, one of whose dimensions is the comic imitation of voyages like those of the French explorer Jacques Cartier through whale-infested northern seas. Not only was an account of Cartier's search for the Northwest Passage to India published in the 1540s as Rabelais was composing his book, but Olaus Magnus published at Venice in 1539 an illustrated Carta Marina of northern Europe between Finland and Iceland. On Magnus's Carta a "sea-monster or spouter" is shown near the Faroe Islands which lie northwest of Scotland and southeast of Iceland (pistris sive phiseter: see Fig. 3). As Povl Skorup has pointed out, it seems clear that Rabelais associated Magnus's Faroe Islands (labeled Fare on the map) with Ferocious Island (Isle Farouche ), which he adopted from another of his sources for the Carnival-Lent episode, the Disciple of Pantagruel .[2]

A spouter as described by Pliny, whose Natural History Rabelais read assiduously, was a large species of whale. In Magnus's sketch it has the appearance of a huge sea horse with two spouts instead of ears; the animal dwarfs in size a nearby ship. But this geographical and zoological shaping of the interlude does not explain its relation to the Carnival-Lent theme. If one looks at the passage in symbolic rather than story-telling terms, its relevance to the development of the Quaresmeprenant-Sausage episode becomes obvious. Below the "physeter" on Magnus's map is a huge fish-shaped creature with two spouts, volcanically emitting water like the other monster. It is labeled balena, the usual Latin word for whale. A third fish-shaped creature with the same two spouts and glaring eyes has been hauled up on the Faroe Islands where men hack away at its flesh. In the sixteenth century these giant spouters

[2] Povl Skorup, "Le Physétère et l'Ile Farouche de Rabelais," Etudes rabelaisiennes 6 (1965): 57–59. On Cartier and his influence on Rabelais, see Abel Lefranc's well-documented if literal-minded book, Les Navigations de Pantagruel (Paris, 1905). Erik Gamby has republished Magnus's map and has translated the accompanying Latin text into Swedish and German: Olaus Magnus, Carta Marina , ed. Erik Gamby (Uppsala, 1964). Rabelais may have been inspired also by the whale episode in one of his favorite books, Lucian's True History . Certainly this text by Lucian plays a major role in the parodic voyage recounted in the Fourth Book generally, as Paul J. Smith emphasizes, Voyage et écriture, étude sur le Quart Livre de Rabelais (Geneva, 1987), 40. Smith also shows, ibid., 37–42, how the navigational references in the Quart Livre constitute a veritable pastiche of Cartier's Brief Recit of his voyages in 1534–1536.

3. Anonymous, Engraved illustration in Olaus Magnus, Carta Marina, Venice, 1539. Section

D: "Pistris sive Phiseter," and "Fare" (Faroe) Islands. Bayer. Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

must have seemed ambiguously fish- and animal-like. They were the most powerful creatures in the world, whose Biblical prototype was the Leviathan. Insofar as they were fishlike, living in the kingdom of the sea, spouters were in Carnival-Lent terms natural allies of Lent. In the late thirteenth-century French poem alluded to earlier, it is the whale among Lent's allies who takes the lead in the counsels of war at a critical point in the comic combat. In another piece, the "Marvellous Conflict Between Lent and Fleshliness" (i.e., Charnaige ), an anonymous French poem published in the early sixteenth century, Lent summons a whale to come to his aid at the moment when his forces fail, but the whale refuses to "leave his domain" to fight on another's ground when his own life, he explains, may be in danger.[3] Thus when the monstrous spouter charges Pantagruel's ship after they pass Tapinos Island, sixteenth-century readers may have seen the action as an imitation of the traditional Carnival-Lent battles. Mental images of the outsized puppets pulled through public squares in Carnival parades would be reactivated by this fight between two giants; the mock battles that so delighted Carnival revelers would be evoked.[4]

The whale episode, like the descriptive approaches to Quaresmeprenant, breaks away from the usual narrative form of the conflict while preserving its symbols. And in terms of the kind of narrative that Rabelais is telling, the interlude serves well to disrupt but not to destroy the mold of the old conflict tradition. The interlude carries the reader away from the early chapters' obsessive focus on the minutiae of Quaresmeprenant's flaccid, monstrous body toward the more relaxed, narratively diffuse development of contact with the puffed-up Sausages.[5]

[3] "Le merveilleux conflit entre Caresme et Charnaige," in Anatole de Montaiglon and James de Rothschild, eds., Recueil de poésies françaises des XVe et XVIe siècles (Paris, 1875), 125. For the whale in the thirteenth-century Bataille de Caresme et de Charnage, ed. G. Lozinski (Paris, 1933), see 8, 22.

[4] Another source for the whale-killing episode may have been a scene in Teofilo Folengo's Baldo, in which Fracasso breaks the head of a whale as large as an island, as Louis Thuasne suggests, Etudes sur Rabelais (Paris, 1969), 251–52.

[5] The unity of chs. 29–42 from the point of view of Rabelais's interest in Carnival-Lent customs, I reemphasize (see n. 9 to Part One), does not exclude their disunity from other points of view. Paul Smith, Voyage et ecriture, 109, pointing out that one of the "thematic constants" in the Fourth Book is the imitation of books recounting wondrous, supernatural voyages (he cites especially the medieval Navigatio sancti Brendani ), sees the whale episode as part of this imitation: the whale as a preternatural animal is one of the typical "obstacles que le héros [du voyage merveilleux] doit surmonter." From this perspective the association of the whale with the biblical Leviathan is one of "demythification" (ibid., 111–13). Smith does not connect the physétère with Carnival-Lent customs, nor does he find the connection to Magnus's map illuminating; among Rabelais's sources he emphasizes especially Pliny (ibid., 114–15). Smith's interpretation of the episode is also helpful on many points of detail (e.g., his demonstration of Rabelais's Pythagorean interests, 117, and his suggestion that Rabelais played on the phonic similarity of physé [tère ] to [Anti ]physie, 112; concerning that, see my ch. 4, n. 1). On the whale episode, see also Frank Lestringant, "L'Insulaire de Rabelais, ou la fiction en Archipel. Pour une lecture topographique du 'Quart Livre,' " Etudes rabelaisiennes 21 (1988): 264, who draws attention to another detail on Magnus's map that occurs in Rabelais's account (it does not concern the Carnival-Lent associations).

The belligerent encounter of Pantagruel and his friends with the Sausages is the third of Rabelais's innovations, for in his tale it is not only "Lent" who will be "Carnival's" opponent, as the whale interlude suggests, but also "Carnival" will fight "Carnival": Friar John and his cooks will confront the sausages. This anomaly is the culmination of Rabelais's plot to engage readers by puzzling them. Readers have already been confused, as I will show, by the difference between what they think they know about Carnival-Lent conflict and what the Pantagruelians seem to know. In the first chapter of the episode, Friar John tries to persuade Pantagruel to go fight Quaresmeprenant. Now with equal zeal Friar John fights the Sausages. Readers are thus summoned to abandon the conventional identifications they would have brought from festive experience. By this point Rabelais has compelled his audience either to reassess everything or to abandon hope of discovering the substantifique moëlle[6] concealed in the comedy. Yet substance there must be. If not, why does Rabelais end the episode, after the battle is over, with a dignified, didactic discussion between Pantagruel and the queen of the Sausages about the strange deity of these strange pseudo-people?

In larger terms the inherited combat pattern seems to fade in and out as the episode progresses, by pulling characters who at first act as mere spectators into the middle of the action and then shunting them aside again. The plot, too, instead of moving toward confrontation between the supposed representatives of Carnival and Lent, moves away from it. Chapters 29 through 32 deal with the monster Quaresmepre-

[6] Alcofribas Nasier explains in the prologue to Gargantua that the apparently trivial exterior of his book conceals a "substance-stuffed marrow" of great worth (G , Pr, 26–27).

nant in isolation from his enemies the Sausages. Chapters 35 through 41 deal with the Sausages, their island, and their attack on the Pantagruelians in isolation from Quaresmeprenant. The chapters on the battle activate the previously passive Pantagruelians. In the final chapter 42 they return to a passive role as their leader and the queen negotiate a settlement that seems to have less to do with Carnival or Lent than with feudal politics and religiophilosophic ideas. At the same time Carnival symbolism is intensified in the chapter on the battle as Pantagruel's cooks "fight" — that is, prepare for eating — sausages by the thousand. Finally, however, no one eats anything. The Pantagruelians sail away.

A double tension is generated between the plot and the coherence of the characters acting in it and between both of these and the symbolic level to which attention is drawn by using metaphorical names for persons, places, and deities. The symbolic level evokes performances and literary patterns loose enough to be familiar to most of Rabelais's readers: there are spectacular figures of some allegorical value, there are ritual battles, there are repeated references to Carnival and Lenten foods. But the plot's dislocations ricochet on such symbolic references to the point where the symbols themselves are placed in question.

3—

Who Is Quaresmeprenant?

Xenomanes gives his friends six descriptions of Quaresmeprenant that differ not only in what they say but also in how they are proffered. The first description generalizes about the "half-giant" in a relaxed, conversational manner. But the next three accounts move to doctor's chambers, abandoning the pretense of talk. Lists of anatomical and physiological traits succeed each other, mixing medical diagnosis with references to such a hodgepodge of objects that one seems to zigzag between hospital and junk shop. The fifth and sixth descriptions return to a more general style, but this time the tenor is one of philosophical reflection, speaking of the monster's behavior and speculating about the meaning of such a "strange case."

The first description revels in ambivalence.[1] Quaresmeprenant is called a "guzzler of dried peas," which would seem to identify him with Lenten meagerness. But dried peas were also carnivalesque. They were put in pigs' bladders and rattled by persons in fools' costume to suggest their empty heads. And they were a staple food during the winter and early spring seasons of Carnival and Lent, when fresh vegetables could scarcely be found. Then comes Xenomanes's comment that Quaresmeprenant is "the most industrious skewer and lardstick maker in forty kingdoms." What does he do with them? We are not told, except that we shortly learn that he is the "eternal" enemy of the Sausages. Does he use the skewers to torture and dispose of his prisoners of war? On the other hand, Xenomanes says that he presented a gross of the skewers to the butchers of Cande near Chinon. This detail reinforces the notion that Quaresmeprenant's name means what it usually did because butchers and their activities were for obvious reasons associated with Carnival.[2]

[1] Quotations from the first description are found in QL , 29, 642–43. See the introduction above where I discuss some other ambivalent parts of the first description.

[2] Jacob Le Duchat, ed., Oeuvres, Volume 4 (Amsterdam, 1711), 126, n. 16, explains Quaresmeprenant's activity in accordance with his interpretation of the monster as Lent: "C'est en Carême, et principalement sur sa fin, que les bouchers, prennent leur tems pour faire des brochettes, et pour remplacer celles qui manquent à leurs Etaux. Les Cuisiniers et les Rôtisseurs choisissent le même temps pour cela, et pour faire nouvelle provision de lardoires, et de brochettes à retrousser la viande." Le Duchat's interpretation is corroborated by a statement in John Taylor's burlesque narration, "Jack A Lent: His Beginning and Entertainment" (1617), in Taylor, Works, ed. Charles Hindley (London, 1872), 12: "Civil policy [supporting Lent against Carnival] . . . causeth proclamations straight to be published for the establishing of Lent's government . . . [and so] the butchers (like silenced schismatics) are dispersed . . . leaving their wives, men, and maids, to make provision of pricks ["i.e., skewers": Hindley's note] for the whole year in their absence." Taylor's derisive reference identifies Lent as the customary time for preparing skewers, but it also associates this activity with butchers, the enemies of Lent. Quaresmeprenant's preoccupation with meat skewers is like that of the butchers' wives and servants and is anything but Lent-like

Quaresmeprenant, Xenomanes continues, is a "great lanterner," descended from "Lanternland stock." A lanterner is a dreamer who passes the time to no purpose. Rabelais made fun of lanterners in a comically vituperative list of "persons of base estate" in his Pantagrueline Prognostication for 1533: lanterners will, along with adventurers, murderers, sergeants, counterfeiters, alchemists, and such, "make a killing" in the coming year (feront ceste année de beaulx coups ).[3] Xenomanes uses the term almost accusingly in the conversation that follows his first description: that "big lanterner Quaresmeprenant" would like to "exterminate" the Sausages.

Lanterning is not necessarily, within the comic frame of the Rabelaisian text, a negative term. The Pantagruelians are sailing in the Fourth Book to Lanternland to find the Oracle of the Holy Bottle. The second ship in Pantagruel's fleet is named the "Lantern" and carries an image of a lantern on its stern. In an earlier chapter the travelers meet a ship returning from Lanternland where, it is learned, a general assembly of Lanterns is going to meet the following July. "From all the preparations it looked as if they were going to lanternize profoundly." This Lantern or "Lateran" council probably represented the coming sixth session of the Council of Trent, scheduled for July 1546.[4] Church councils had repeatedly been held in the Lateran palace of the popes in Rome, most

[3] PP , 5, 923.

[4] See QL ., 1, 561; 5, 574: This reference to the next church council session allows composition of ch. 5 to be placed with probability before July 1546; it does not seem likely that the passage was composed later because the session scheduled for July was postponed.

recently in 1512–1517, a council that Pope Julius II and Leo X used to counter French attempts to revive conciliar government in the church. Thus a punning reference to a Lantern council implied that at Trent the pope would probably try to carry further his pretension to rule over the church monarchically.

Such divergent references to Lanterners and lanternizing are Rabelais's way of communicating different perspectives upon one verbal sign by juxtaposing the points of view of author, narrator, and narrative actors. Is Rabelais the author making fun of the pious hopes of Pantagruel for a resolution to the questions of church reform at the long-awaited council? The Pantagruelians are portrayed as lanterners in the sense of seeking light and wisdom. But perhaps also Rabelais is suggesting that dreamy trust in light from human contrivances like lanterns or Lateran councils is vain. They beam forth not truth but merely the will and intentions of those using them.

The Pantagruelians and Quaresmeprenant share a tendency to dither around and lanternize. But lanterning also had a sexual meaning relevant to Quaresmeprenant. It was a slang word for the penis. In an obscene poem called the "Fricassée crotystylonée," purporting to record a rhyming game of Rouen children in the mid-sixteenth century, one question and answer goes:

— What are you doing there?

— I'm making lanterns

To put in the ass [au cul]

of the fellow asking for it.[5]

Lanterning seems to be understood here as something like the modern "fucking around," or "fooling around" the euphemism meaning the same thing. Panurge uses the word in a similarly aggressive male homosexual sense in the Third Book and again, offensively but heterosexually, in an early chapter of the Fourth Book .[6] When placed in parallel

[5] Gaignebet, Folklore obscène , 167. The sixteenth-century rhyme also refers, according to Gaignebet, to a game that is played in present-day Carnivals in south France in which people try to attach a lighted wick to the lower posterior part of the costume of the person preceding them, as they dance single file through the streets. But Gaignebet does not cite sixteenth-century or other early sources to support this interpretation.

[6] TL , 443: "Va (respondit Panurge), fol enraigé, au diable et te faiz lanterner à quelque Albanoys." Albanians like Bulgarians were popularly accused of sodomy. QL , 9, 587: "Le vent de Galerne (dist Panurge) avoit doncques lanterné leur mère?"

with some characteristics of the monster, which will be described later, this sexual meaning of Quaresmeprenant's Lanternland origin emerges as less than playful.

Quaresmeprenant nourishes himself on war: "his usual foods [les alimens desquels il se paist] are salted hauberks, casques, salted helmets, and salted sallets [salades sallées: punning on "salad"], on account of which he sometimes suffered a heavy hot-piss." Salty things stimulate the appetite: is this how the fellow excites himself for a voracious fight with the Sausages? However that may be, Xenomanes's first description, in spite of the ambivalences in detail, pulls the reader toward identifying Quaresmeprenant with Lent, not Carnival. The meaning of some seeming identifications of Quaresmeprenant with Lent only becomes questionable in retrospect. "He burgeons with pardons, indulgences, and altar prayers [stations ]."[7] "I've found him in my breviary . . . after the movable feasts," declares Friar John. To what is Friar John referring? Has he concluded that Quaresmeprenant corresponds to Quadragesima (Lent) in his Latin breviary? If he has, should his conclusion be taken seriously by the reader, familiar with Friar John's tendency to jump to conclusions? If Quaresmeprenant is so clearly and simply Lent, why do his mortal enemies the Sausages have fishy characteristics?

The Sausages are identified in this first description merely as the dependents or perhaps the vassals of "noble Mardi Gras, their protector and good neighbor"; they are not equated with Carnival. These Sausages, Xenomanes explains further, are all "mortal women, some virgin and some not," yet they ardently make war. Lent was sometimes identified as a woman in the literary, iconic, and performative traditions of the theme, but only in Rabelais's text is it maintained that Carnival's allies are all female. Indeed the maskers of Carnival in Rabelais's time were in most parts of France all male. What can be the function of such sexual inversion?

[7] "Altar prayers" is only one possible translation. Stations might mean several things: the place within a church from which a preacher would deliver a series of sermons on some social occasion like the days of Lent; an altar before which one would halt to pray before an image (as in the "stations of the cross"); the ceremony in the course of which one would make such prayers; or the church designated for such prayers (as along the route of a pilgrimage).

Pantagruel asks Xenomanes to extend his account of Quaresmeprenant. The three long lists with which Xenomanes accommodates the giant describe first the creature's internal anatomy, then his external parts, and finally their functioning or physiology. Such a move from internal to external description was, as Marie Madeleine Fontaine has shown, common practice in the public dissections forming part of medical training in Rabelais's day. The items of internal anatomy are ordered vertically from the skull's contents down to the base of the intestinal cavity and then outward to muscles, ligaments, and invisible organs of the soul like imagination and intelligence. The items of external anatomy are ordered inversely, from the toes to the head, and then outward to skin and hair. The psychological list moves from upper bodily to lower bodily functioning and then to dreaming and worrying, that is, to a kind of invisible functioning.[8]

"As for his internal parts Quaresmeprenant has — or had in my time" (Xenomanes made a visit to the island some years earlier) — "a brain the size, color, substance, and vitality of a male cheese maggot's left testicle." What a superb example of what Bakhtin has called Rabelais's "grotesquely real" style, in which high, noble objects are debased by comparing human to less-than-human qualities and "high" areas like the brain to "low" ones like the genitals and intestines.[9] But the comparisons move sideways as often as up and down, always with the same unlikely vividness. "His [cerebral] membranes [are] like a monk's cowl . . . his pineal gland like a bag-pipe . . . his colon like a drinking-cup? Seventy-eight "internal parts" are explained in a series of terse analogies that corresponds stylistically to the dryness and lethargy of the creature being anatomized. The next chapter describes sixty-four external organs in the same way; the chapter after that, still maintaining the one-line style, catalogs thirty-six symptoms of sneezing, coughing, talking, and dreaming.

If one reads these lists at the same pace and with the same contextual framing of the text as one has done with respect to the description in the preceding chapter, most of their effect and meaning is lost. The continuity between one item and the next is frequently hard to see; a

[8] See QL , 30–32, 643–49. Fontaine, "Quaresmeprenant: l'image littéraire et la contestation de l'analogie médicale," in Rabelais in Glasgow, ed. Coleman and Scollen-Jimack (Glasgow, 1984.), 90–93, compares the ordering in the first two lists with those of contemporary anatomists.

[9] Bakhtin, Rabelais, 19, 52–53, esp. 308–25.

sense of the whole is impossible to seize from a list of two hundred similes, read from beginning to end. At one level perhaps the reader's confusion is intended. Read apace, these lists create a strong general impression. Quaresmeprenant is, as one commentator puts it, "pulverised" by Rabelais's linguistic strategies, reduced to an image not merely of immobility but of disjointedness.[10] But how and why is this done?

Both the order and the vocabulary used in the lists follow commonplace anatomical practice in Rabelais's time. Sixteenth-century translations of Galen and of the fourteenth-century French physician Chauliac show the same mixture of Greek, Latin, Arabic, and everyday French nomenclature and also the same kind of comparisons to everyday tools and household accoutrements. But the doctors did not in their serious works animate the parts or offer concrete images of abstract functions: "His animal spirits [are] like fisticuffs . . . his consciousness like the fluttering of young herons leaving the nest . . . his understanding like a tattered breviary."[11]

Quaresmeprenant is akin, I have suggested, to the terrifying giants displayed in Carnival parades. Like these lumbering, lurid constructions, Rabelais's grammar urges the reader to peruse the monster part by part, enjoying each absurdly pseudo-human detail. Like the disconnected grammar, each organ and each organ's function operate as independently as the everyday tools and accoutrements, the commonplace insects and birds, to which they are for the most part compared.

The description of functions like memory and consciousness, which sixteenth-century medical science thought were related to what would now be called nervous and circulatory systems, produces magnificently comic effects of misplaced concreteness. Playing on the phonetic closeness of reason and resonance (raison, résonne [r ]), for example, Xenomanes returns by means of the last item in this list to his opening com-

[10] Floyd Gray, Rabelais et l'écriture (Paris, 1974), 184.

[11] See Fontaine, "Quaresmeprenant" 111–12, n. 30, for quotations from the translations. Fontaine illustrates the points about nomenclature with rich details, 93–95. But her conclusion, 101, is questionable because it does not consider the differences from medieval texts of Rabelais's listing, occasioned by the latter's terse style and its inclusion of elements like young herons leaving the nest or tattered breviaries: "Un repertoire des analogies et comparaisons de Galien, souvent reprises par les médecins du XVIe siècle, ou des analogies de Chauliac, aboutirait à un texte aussi grotesque que Quaresmeprenant. Il revelerait des zones de références absolument identiques à celles de Rabelais."

ment on the monster's stupidity by alluding to Quaresmeprenant's hollow head: "His reason [is] like a little drum." Several ecclesiastical references in addition to the ones about the tattered breviary and the monk's cowl recall satirically Xenomanes's opening comment that the monster is a "good Catholic, thoroughly devout." But they do not substantiate his Lenten identity, if such it is.[12] Quaresmeprenant's warmongering is alluded to indirectly ("his stomach like a sword-belt . . . his viscera like a gauntlet . . . his bladder like a catapult") and also rather directly ("his repentance like the carriage of a double cannon"). The metal and leather of his intestinal tract contrasts with his soft sexuality: "his spermatic vessels like a feuilleté cake, his prostate gland like a feather-jar."[13]

Quaresmeprenant's sperm, on the other hand, is like "lathe nails," and his progeny is even stranger: "His nurse told me," says Xenomanes, "that when he married Midlent he begot only a quantity of locative adverbs and certains jeunes doubles ." The French words are a pun, "double fasts" or "double young ones." double children, twins perhaps, even Siamese twins, but singularly deprived.[14] As for the locative adverbs, a late sixteenth- or early seventeenth-century commentator, Perreau, refers this phrase to the vogue for indulgences among devout Christians during the latter half of the Lenten season between Midlent and Easter. Locative adverbs indicate the places where one is, where one comes from and where one is going. Begetting locative adverbs would then mean that Quaresmeprenant bustled from place to place at this season, searching for ecclesiastic pardon.[15]

But Midlent in popular terms meant something far different from churchly enthusiasm. Falling on the fourth of the six Sundays in Lent,

[12] "His heart like a chasuble . . . . His mesentery like an abbot's mitre . . . . His bum-gut like a monk's leather bottle."

[13] A feather-jar, explained Rabelais's eighteenth-century editor Le Duchat, is an old broken pot that is no longer useful as a container for liquids and so is used to collect feathers for eventual use in bedding. Le Duchat, in Oeuvres, ed. Bernard, 2: 78.

[14] Fasts, jeûnes, would normally have been spelled jeusnes in the sixteenth century. Would jeusnes and jeunes have been pronounced in exactly the same way in Rabelais's time and place? Does the use of jeunes doubles also play on the Church's classification of the Sundays in Lent as fêtes doubles, that is, as days of special piety on which a "double office" is read?

[15] See 156–57 for Perreau and the crooked history of this particular explication of Rabelais's text.

it was a holiday on which Carnival erupted anew. Parades, picnics, noisy musicmaking, masking, and bonfires marked the date. Here again Rabelais's description of Quaresmeprenant seems intended to puzzle: Does marriage pull the fellow toward or away from Lent? One ritual of Midlent Sunday, documented for later sixteenth-century Italy and presumably existing there earlier when Rabelais might have observed it, was for children to run through streets screaming "Saw down the old woman!" Wooden images of an ugly old female were carried about and then sawed in half to shouts of laughter as a sign that Lent was half-gone.[16] Does Quaresmeprenant marry an aged or even mutilated replica of Lent, or does he marry the Carnival spirit that violates Lent midway?

In either case the monster's action, viewed in its calendrical context, seems masochistic. Midlent was the only occasion between Ash Wednesday and Easter when in most parts of Catholic Europe a person was authorized to marry. But to marry on that day insured that there would be no prolonged celebration, for fasting must resume on Monday. To marry the personification of a day in Lent could only lead back to fasting, as the calendar insures that it does. Perhaps engendering double fasts simply means that Quaresmeprenant establishes a household in which the tendency toward asceticism is redoubled.

The similes used in the second anatomical description are again articles of everyday employment: slippers and cream cake, crossbows and bagpipes, chessboards and watering cans. Quaresmeprenant is a collection of commonplace things. Should one make a case for the preponderance of items forbidden or frowned upon in Lent, like musical instruments, sporting accoutrements (tennis rackets and billiard tables), and rich foods (drinking cups, dripping pans, cream cakes, butter-pots)? No. Reasoning from tennis rackets to anti-Lenten attitudes tortures the text as uselessly as concluding that Quaresmeprenant personifies Lent because he handles barrels sometimes filled with herrings.

M. M. Fontaine has argued that the ordering of the lists, choice of vocabulary, and especially the manner of argument in these descriptions

[16] See, e.g., Giulio Cesare Croce's broadsheet poem, Invito generale . . . per veder segare la vecchia (Bologna, 1608) or Michelangelo Buonarroti's Cicalata (Florence, 1610), quoted in Lidia Beduschi, "La vecchia di mezza quaresima," La ricerca folklorica 6 (1982): 37.

indicate that Rabelais is making fun of Galenic medicine. Sixteenth-century anatomical science not only exposed a variety of particular errors made by Marcus Aurelius's physician but began to replace Galen's use of verbal analogies with the far superior method of visual illustration, most notably in the extremely meticulous representations of the dissected human body in Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica (1543). Rabelais's tersely repetitious similes render the verbal analogical method ridiculous, not so much with the aim of satirizing Galenists or of directly taking part in the contemporary debates over scientific method, cautions Fontaine, but rather with the purpose of "experiencing the difficulties" encountered in practicing medicine at the time and indeed of experiencing them through laughter that objectifies rather than through satire that attacks.[17]

It is quite possible that one dimension of Rabelais's anatomical approach to Quaresmeprenant is a laughing critique of the use of verbal analogies in medicine. But it is certainly not true that, as Fontaine suggests, this critique forms part of a simple "logic" linking chapters 29 to 32 together by means of "several little syllogisms." For Fontaine these syllogisms are "rather easy to discern":

Quaresmeprenant (Lent, its Catholic rituals and its folklore) inhabits Tapinos Island (the island of hypocrisy). Now, he is a "sucking babe of doctors" because the essential ritual of Lent, fasting, makes one sick. And what did doctors most busy themselves with at the time? With anatomies and descriptions of the structure of the body, and then with a diagnostic

[17] Fontaine, "Quaresmeprenant," 90. This reasonable beginning is not always sustained in Fontaine's later argument. She claims that Rabelais in the Fourth Book refers at least by implication to an attack of the Galenist Sylvius on Vesalius, published at Paris in 1551, and also to Peter Ramus's criticism of Galen, since Ramus was appointed in 1551 to the Parisian Royal College (the present-day Collège de France) and Rabelais was resident that same year in Paris, just at the time Rabelais finished composition of the Fourth Book: "Il est impossible, puisqu'il en fait état dans son Prologue et qu'il est alors parisien, que ces implications soient inconnues de Rabelais, et notamment les aspects méthodologiques. Ce furent de durs temps de Carême!" (100). The only reference to Galen in the prologue has nothing to do with Galenic method, let alone with Ramus, Sylvius, or Vesalius (for the prologue reference to Ramus, which has to do with another affair, see ch. 8), and Rabelais's reference to Lent seems neither "dur" nor in any way connected to the issue cited by Fontaine (Fontaine, ibid., quotes the words discussed in ch. 1 above). Fontaine is not the first to point out that Rabelais's analogistic method in these anatomic chapters both repeats and enlarges upon contemporary medical practice: see Roland Antonioli, Rabelais et la médecine (Geneva, 1976), 289–90.

the illness by means of studying the patient's "appearances". [contenances][18]

From the first announcement of the name Quaresmeprenant and Friar John's comment on the presence of a creature like him in his breviary, Rabelais has led his sixteenth-century readers not toward the clarity of syllogisms but toward bewilderment. One of the author's strategies in this respect has been to juxtapose readers' knowledge to the knowledge of actors in the text. For although readers knew that the word Quaresmeprenant designated Carnival, the Pantagruelians, their guide Xenomanes, and their chronicler Alcofribas, the implied author of the tale, do not seem to know this. They also do not seem to know the inverse of this proposition, that Quaresmeprenant means Lent.[19]

Rabelais is encouraging his readers to distinguish between narrative and other levels of experience. After Xenomanes explains in his first description that the Sausages live under the menace of the monster, the friar wants to go fight Quaresmeprenant. Panurge exclaims: "Quid juris " — that is, by what right or in accordance with what legal judgment would we defend ourselves — "if we should find ourselves trapped between Sausages and Quaresmeprenant, between anvil and hammers?" If readers take narrative reality to be metaphorical play with behavior familiar to them, such as the mock battles on mardi gras, then Panurge's words correspond to readers' festive experience. If one or the other side in the battles should resort to law — as in the lawsuit farces of the day, and as in Rabelais's Pantagrueline Prognostication — then how could persons interfering in such an officially endorsed and customarily sanctioned fight legally justify themselves? But then why is a monster with so many Lenten traits behaving in such a Carnivalesque way, "fighting" sausages? Does fighting mean that he eats them, like his colloquial name, Carnival (Quaresmeprenant), would seem to require, or that he exterminates them, as so many of his Lentlike character traits would indicate? The Pantagruelians, existing at the level of narrative reality,

[18] Fontaine, "Quaresmeprenant," 87. The terms of these so-called syllogisms were developed in anything but an easy and obvious way in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, as indicated in Part Three below.

[19] The reasons for supposing that this is true even for Friar John, who finds Quaresmeprenant in his breviary, and for Panurge, who speaks of the contrast between Quaresmeprenant and the Sausages as a simple opposition in the passage quoted later in this paragraph, have to do not with the word's ambiguity but with its ambivalence, as we will see.

know nothing of such metaphorical puzzles. Nor can they be conscious of a second level of contextual reference in which the Sausages figure as Protestants and Quaresmeprenant as Charles V, leader in a Catholic war that had indeed "hammered" the German Protestants only a few years before the appearance of the Fourth Book . The French — that is, metaphorically, the Pantagruelians — were secretly allied with the German Protestants; they had in this sense "illegally" interfered in the German fight, in contravention of their alliance with Charles V in the Treaty of Crépy (1544).[20]

Such veiled allusions to contemporary politics cease during Xenomanes's descriptions of the monster's physiognomy. The Pantagruelians are entirely silent after each of the three lists. Alcofribas, the narrator, separates the lists, by beginning a new chapter for each of them. One by one, the disjecta membra of the lists dissuade the reader — and the narrative listeners, the Pantagruelians? — from identifying the monster as either traditional personification. During this section of the episode Quaresmeprenant loses his identity as Carnival without gaining that of Lent, and vice versa.

He also very nearly loses his identity as a human being. Although he has the organs and spirituous fluids thought to explain human physiology, the grammar used to enumerate them as well as the things to which they are compared make Quaresmeprenant seem more and more jerkily, discontinuously, mechanically connected in his parts. He assumes the dimensions of the gaping constructions that astonished merrymakers at Lyon, Metz, and Nuremberg. As with these puppets, the displacement and juxtaposition of the ordinary things used in Quaresmeprenant's fabrication are both horrifying and comic.

It seems possible — and the orderly sequence of now familiar and now arcane anatomical parts encourages readerly efforts in this direction — vaguely to imagine some such bizarre assemblage of tennis rackets and bagpipes, feather-jars and gauntlets.[21] But at the same time

[20] QL , 29, 643. See ch. 2, n. 27. Krailsheimer, "The Andouilles" neither drew attention to this passage nor suggested that Panurge was speaking of French policy in veiled terms. But it is very probable that this level of allusion is present here because of Rabelais's personal connections with the policy. He was involved, directly or indirectly, with his patron Jean du Bellay's negotiations with the German Protestants while residing in Metz, 1546–1547. See Marichal, "Rabelais et les Censures" 138–41.

[21] The modern reader has a difficult time of it in these passages, created by four centuries' distance from commonplace objects that are no longer common-place. They have become exotic and unfamiliar or — potentially more distorting for understanding the text from a sixteenth-century point of view — objects of regret and nostalgia. This nostalgic and/or exotic framing of the descriptions accounts, perhaps, for Paul Eluard's extraction of these chapters from their context and their inclusion — as a surreal poem? — in his anthology of French poetry, La poésie du passé, Volume 1 (Paris, 1960), 273–79.

Rabelais is not describing something that could or should be seen as an entity at all. Part of the tactics of giving an emblematic quality to Quaresmeprenant is that in three of his six descriptions Xenomanes does not in strict grammatical terms describe but only compares the monster to an array of things to which his appearance and behavior are analogous.[22] Just as Pantagruel's fleet is in the process of passing by Tapinos Island without stopping, moving further and further away, so Quaresmeprenant, the more his characteristics are listed, the more remote from any coherent reality he seems.[23]

Having constructed the scarecrow, Rabelais wheels it into action. A

[22] Fontaine, "Quaresmeprenant," 89–90, especially emphasizes Xenomanes's procedure by analogy. There are some significant exceptions to this generalization. The second description (ch. 30) consists of analogies except for the first characteristic, describing the size of the brain. The third description (ch. 31) also consists of analogies except for the first characteristic (Quaresmeprenant has seven extra ribs). The sixth description (end of ch. 32) consists of Pantagruel's extended metaphorical comparison of the monster to the children of Anti-Nature.

[23] This point is established with many finely observed details by means of syntactic analysis in François Moreau, Un aspect de l'imagination créatrice chez Rabelais (Paris, 1982), 88–92, by means of stylistic analysis in Alfred Glauser, Rabelais créateur (Paris, 1964.), 251–55, and at a philosophico-ideological level by Michel Beaujour, Le jeu de Rabelais, 127, 139. Michael Riffaterre concludes from syntactic and stylistic analysis that any attempt to "read it [the text of chs. 29–32] in search of a meaning, [by] trying to see Quaresmeprenant" is doomed to failure. "Quaresmeprenant is a monster not because he is formless, but because he cannot be expressed, because he is literally unspeakable" (Text Production, 20). In effect, Riffaterre carries to an extreme the thesis of Fontaine concerning Rabelais's satire of incoherent medical analyses based on analogical referents. None of these authors suggests the relevance of mechanical constructions like Carnival puppets to the passage. The tendency is rather to offer organic parallels: "Rabelais a vu toutes les possibilités du comique de raideur . . . indiquant par une accumulation de détails un arrêt de vie, une stupéfiante momification" (Rabelais créateur, 252); "On peut songer ici aux têtes grotesques d'Arcimboldo, composées avec des fleurs ou des fruits qui, si on les regarde isolément, sont très agréables à l'oeil" (Moreau, Un aspect, 92); "Rabelais décide à l'entrée du ch. 31, que Quaresmeprenant possède côtes et se moque ainsi du débat [between pro- and anti-Galenists; note the misreading; Xenomanes says Quaresmeprenant has seven more ribs than a normal person, QL, 31, 646] . . . . Rabelais s'est ainsi donné un autre motif de rire: son Quaresmeprenant est un singe, et il retrouve ainsi la tradition médiéval de l'hypocrite, et du moine simiesque" (Fontaine, Quaresmeprenant, 97). Glauser's reference to the Quaresmeprenant descriptions in his more recent work, Les fonctions du nombre chez Rabelais (Paris, 1982), 144–46, develops his earlier idea of stylistic "mimesis": the "brevity" and "monochordal rhythm" of the items in the lists signifies "arrêt et mort l'écriture, métaphore de Carême et inversement, car le personnage signifie le texte, autant que le texte signifie le personnage."

new syntax is employed in the third list (Xenomanes's fourth description, chapter 32).[24] Instead of using the anatomical form "Q's x is like y ," this list is diagnostic: if Q does x , then it means y . The xs in the third list vary between Quaresmeprenant's observable behavior (sweating, speaking, blinking) and actions that could only be reported by the patient to an inquiring doctor (defecating, worrying, wool gathering, dreaming, all grouped at the end of the list). The ys in the third list could be interpreted as having the same relation to Quaresmeprenant's behavior as implements, accoutrements, and animals have to his anatomy in earlier lists, but then why did Rabelais change the syntax? Perhaps simply because the "if x then y " syntactic form is more apt to describe motions and actions than the "x is like y " form.

Although the earlier lists give an impression of a body-as-machine with nearly all the parts there to see, high and low, inside and out, this inventory of bodily functions is heavily weighted in favor of movements of the head and actions of the brain.[25] Xenomanes in effect sketches the psyche. A few items concerned with invisible anatomy were already psychological in character (e.g., in the first list, "His intelligence, like snails crawling out of strawberry plants"), but now the emphasis is stronger and more continuous. A textual move toward psychologization of the creature also seems borne out by the following fifth description, as I will show. Interpreted thus, the ys in the fourth description careen between fear and nostalgia, reality and desire, boredom and wishes. Fear: "If he trembled it was large helpings of rabbit pâté ; nostalgia: "If he blinked his eyes, it was waffles and wafers." Re-

[24] These and following quotations from the fourth description are from QL, 32, 648–49.

[25] Twenty-nine of the thirty-six bodily motions in this list describe actions of the head and brain. Robert Groos has devoted an article to this particular description: "The Enigmas of Quaresmeprenant: Rabelais and Defamiliarization," Romanic Review 69 (1978): 22–33. But he constructs solutions to enigmas that exist only because he himself has created them, disregarding Rabelais's grammatical and rhetorical indications.

ality: "If he blew his nose, it was salted eels"; desire: "If he wept, it was ducks in onion sauce." Boredom: "If he yawned, it was pea-soup"; wishes: "If he sighed, it was smoked ox tongues."

In the opening description Xenomanes calls Quaresmeprenant "father and sucking babe of doctors." The enigmatic epithet is clear enough in the light of these lists. The fellow is a good Catholic, concerned with Lenten regulations, but the more he represses his impulses, the less he controls his appetites, and so he has fallen sick, and chronically. He sustains and stimulates the doctor's skills with his absurd mode of life. The monster's equal commitment to both rules and self-aggrandizement makes him all the nastier: "If he scratched himself, it was new regulations"; "if he dreamed, it was mortgage deeds."

Quaresmeprenant is a hypocrite and pathologically so. The aim of Xenomanes's lists is not to recapitulate the method of medieval authors developing the Carnival-Lent combat theme, in which material objects correspond to ritual rules, with fish and vegetables, meats and fowl, asceticism and self-indulgence, greed and generosity each fixed and distinguishable in their symbolism. In Quaresmeprenant any food, any everyday object may signify by turns a Lenten or a Carnival attitude, depending on the psychology investing it. Xenomanes's descriptions abandon pretension to any system of firm signs guaranteeing that behavior corresponds to belief. In Quaresmeprenant a certain psychology is merely associated with a certain physiology and physiognomy.[26] The congruence of one with the other could be illustrated with any sort of behavior, ad infinitum. Xenomanes's lists go on and on in order to develop that sense of congruence, not in order to arrive at a precise moral-theological definition of character like those in medieval representations.[27]

[26] This distinction between correspondence and association is parallel to Michel Foucault's "resemblance" and "similitude" (this would be better translated as "similarity") in The Order of Things (New York, 1970). A brief and not unduly simplified discussion of Foucault's complex distinction is in the translator's introduction to Foucault, This Is Not a Pipe (Berkeley, 1983), 9–10, by James Harkness: "'Resemblance,' says Foucault, 'presumes a primary reference that prescribes and classes' copies on the basis of the rigor of their mimetic relation to itself . . . . With similitude, on the other hand, the reference 'anchor' is gone. Things are cast adrift, more or less like one another without any of them being able to claim the privileged status of 'model' for the rest."

[27] I have discussed the medieval-modern contrast in "Presentation," 23–30. In medieval representations the significance of observable traits is deduced from general principles: "Stomachs like wine barrels, emaciated features like a haggard face or scabby tail, hairy skin, and giant stature cannot change their moral meaning without pulling after them a skein of other symbols. Each is embedded in an elaborate framework of mutual reference, hierarchically organized. In the modern system this attachment of any particular symbolic feature to a hierarchic system has been eroded through such practices as the conversion of ritual into spectacle and the transfer of festive symbols to nonfestive contexts" (25). As traditional connections among Carnival symbols faded, new connections could be suggested, which were adapted to the expression of changing norms of political and psychological behavior rather than to the reflection, as in the medieval system, of the order of the seasons and their religious corollaries.

The congruence portrayed in Quaresmeprenant concerns the mental and bodily effects of routinely deferring and deterring the exercise of natural faculties. This Carnival puppet of a man is always moving toward Lent — but regretfully so, with his mind on the pleasures left behind. "If he mumbled, it was law students' farces" (jeux de la bazoche ); "if he was hoarse, it was the coming-in of Morris dancers" (the latter were as regular a feature of Carnival revels as the law students' farces).[28]

In addition to comically imitating Galenic modes of anatomical description, the use of material, humdrum elements to describe the monster moves readers to fill the imaginary space around that being with the everyday flotsam and jetsam used to describe his body and behavior. Not some place among churchly observances in the cleric's breviary but his obsessive desires and his feud with the people on Ferocious Island have shaped him.[29] This implication is in consonance with the etymology of the monster's name. The first part of it, quaresme -, is simply the

[28] The basoche was an association of largely unmarried young men exercising legal professions in larger French cities.

[29] Of course I am not suggesting that one should reconstruct the life of the monster beyond the text, as in the case of that school of Shakespearean critics that used to trace the supposititious biographies of the playwright's characters. Rabelais creates a semiotic, not psychosomatic, coherence between psyche and behavior. The concept engendering this coherence has more to do with the ancient idea of macrocosmic (natural)-microcosmic (human) correspondences than with any theory of medicine. As Roland Antonioli concludes in his surprisingly brief commentary on the Quaresmeprenant chapters in Rabelais et la miédecine: "Pour l'anatomiste qui connait l'assiette et la conjonction des particules, le corps humain résume tout l'Univers" (290). In contrast to Antonioli's conclusions, the works by Anatole Le Double, Rabelais anatomiste et physiologiste (Paris, 1899) and Dr. Albarel, "La psychologie et le tempérament de Quaresmeprenant," Revue des études rabelaisiennes 4 (1906): 49–58, move to an opposite extreme of medical "realism" taking the text as a serious representation of actual maladies and praising Rabelais for the precision and clarity of his medical descriptions.

French contraction for the Latin name of the first Sunday in Lent, Quadragesima. The second part of it has been explained in two ways. The usual manner, adopted in the standard French dictionaries by Littré and Godefroy, derives -prenant from Latin prehendere. Prehendere means to take hold or pull to one's side, and so in this case Quaresmeprenant means to take hold of or begin Lent. The philologist and literary historian Leo Spitzer, however, suggests that the word comes rather from Latin praegnans : to be full of something imminent, not necessarily of a child but of this or that principle or reason.[30]

Quaresmeprenant, used with attention to its etymology in either of the two senses, would refer not to the season of revels in general but to its last days. What if Rabelais was thinking of Quaresmeprenant not as a fixed and determined object in the Christian calendar, but as a transition period? What if his purpose was to pry loose this personification from its medieval allegorical web of equivalences and oppositions and to offer instead a sense of what happens psychologically as Lent takes hold of the Christian soul[31] The "pregnant, way of explaining the word would be particularly suited to developing this idea. It is abundantly clear from Rabelais's portrayal of Quaresmeprenant that in his opinion Lenten spirit fills the soul not with virtue but with contradictions. A former Franciscan monk, who must have sought to fulfill Lenten rules for years before he rejected monastic discipline and took up the profession of a doctor, Rabelais would have known something about the psychology and perhaps also the physiology portrayed in Quaresmeprenant.

This fellow represents neither Carnival nor Lent but the inversive logic that binds them together. Not ambiguity or confusion but the dynamics of ambivalence are the key to understanding Rabelais's monster. These dynamics are the psychic equivalent of the social inversions of Carnival time: men become animals, women dress like men, humans costume themselves as giants, Christians behave like pagans. The excesses of Carnival lead to the repressions of Lent, repressions known

[30] Leo Spitzer, "Zu carnaval im Französischen," Wörter und Sachen 5 (1914): 194, n. 2, takes issue with Littré and Godefroy. Spitzer was puzzled by Rabelais's use of Quaresmeprenant in the Fourth Book, and he notes that Le Duchat was, too, but he does not pursue the mystery (195–96, n. 1).

[31] See Appendix 2 for a delightful representation of the medieval mode in a poem by Charles d'Orléans.

and in some sense sought by every believing Christian. The pre-Lenten season is fat and full not only with feasting but also with what follows it. It is as pregnant with Lent as that ribald Midlent Sunday is pregnant with twin fasting and other obsessive ascetic practices, exercised with greater and greater fervor as the church year approaches its climax with Easter.

Carnival pregnant with Lent — an eminently carnivalesque idea and a commonplace one, as Claude Gaignebet and others have noted: male pregnancy is a fantasy recurringly played out in Carnival time.[32] Whether or not Rabelais had some sense of the second, pregnant way of explaining the word, he did in writing this episode intend to push his readers toward awareness of the word's roots, quite in contrast to the commonplace way in which he had used it twenty years earlier in the Pantagrueline Prognostication .[33] His emphasis in these lists is on the bodily emblems of contradictory desires. Quaresmeprenant is a monstrosity because he is torn between trying to live according to Lenten rules and wishing for Carnival foods, law students' farces, and Morris dancers.

Centering the question of Carnival-Lent difference not upon ritually selected aspects of behavior but upon the psychological consequences of such selection was not peculiar to Rabelais. Lent, talking to his captains in a basoche play presented at Tours called The Battle of Saint Pansard (1485), exhibits a similar susceptibility:

BRIQUET: [Greeting Caresme .]

May Charnau [Fleshliness, or Meatiness, the personification of

Carnival],[34] who's disputing with you, have cold teeth and a

flat stomach,

A dry throat and nothing at all to fry!

And may Macaire [Caresme's cook], that excellent gentleman,

And Caresme, and all his empire,

[32] Claude Gaignebet, Le Carnaval (Paris, 1974), 48–49. See, for the more ample context of the theme beyond Carnival as part of traditional popular tales, Robert Zapperi, L'homme enceint, l'homme, la femme, et pouvoir (Paris, 1983).

[33] See ch. 2. above. His concern here with the peculiar etymology of Quaresmeprenant is perhaps further indicated by the fact that he uses the word carneval, not Quaresmeprenant, elsewhere in the Fourth Book (QL, 14, 602; QL, 59 , 722), to designate the period of revels.

[34] Charnau is called Saint Pansard only in the title of the play, not in the text. The play is edited by Aubailly in Deux jeux de Carnaval; see 34–35 for these quotations.

Give them just such bits and pieces to gnaw

As will make their bowels do nothing but sigh

For eating and drinking.

CARESME: O Briquet, Briquet, my sweet friend!

Your fine discourse makes me gurgle [me gourgoulle]

I experience such joy in listening to you

That my stomach churns [me triboulle] . . .

MARQUET: There's n bristle on my butt which doesn't twist,

No gut in my groin which doesn't groan,

When I think of the great sausage blows

One [Carnival?] launches upon a naked head!

CARESME: Marquet, you are most welcome.

[But] your words make me clutch my gullet

And I seem to be catching a fever

Which is stopping up my throat.

For all his susceptibility, however, Caresme in this law student farce remains Caresme, exhibiting no psychic ambivalence about his moral identity or purpose. No one using the Carnival-Lent theme developed anthropomorphosis of the old personifications to the pitch of psychic subtlety found in Rabelais's episode.[35]

Xenomanes's fifth description, occupying the second third of chapter 32, returns to the sketchlike style with which he first spoke of Quaresmeprenant.[36] The monster's contradictions are developed so phantasmatically that they no longer have much to do with either the Carnival-Lent tradition or the larger literary and popular-cultural tradition of grotesque realism. "Fasting, he ate nothing; eating nothing, he fasted. He nibbled as if in suspicion, and drank in imagination . . . . He feared nothing but his own shadow and the cries of fat kids." Each element in the new description recalls at a more general level some part or parts of the preceding lists. "He laughed as he bit, and biting, he laughed"; one recalls Quaresmeprenant's teeth "like boar's tusks" and the remorseless insatiability of his repressed appetites. He is both indolent and hyperactive: "Doing nothing he worked, and working, he did nothing." "He

[35] Similar embodiment of psychic properties is given by Hans Sachs to Carnival in his poem, "Ein Gesprech mit der Fasnacht [sic ]" (1540), in his Werke, ed. von Keller and Goetze, 5: 295–98. See also Grinberg and Kinser, "Les. Combats" 84, on the theme of embodiment in a narrative poem by Giulio Cesare Croce, Processo overo esamine di Carnevale (Bologna., 1588).

[36] QL, 32, 649.

used his fist like a mallet"; his bodily parts are often like weapons. His mind twitches between the excessively soft and excessively hard, between regret and vengeance; he is, one recalls, a "whipper of small children" who nevertheless "weeps three parts out of each day."[37]

Contradiction, pushed to these extremes, is surreal: "He bathed above high steeples and dried out in ponds and rivers"; "He fished in the air and caught huge crayfish there."[38] Such features remove the creature still further from the reader and the Pantagruelians. The fourth description begins: "What an extraordinary case in nature" (Cas admirable en nature ). The fifth begins: "What a strange case" (Cas estrange ). Indeed, Quaresmeprenant has become stranger than nature: thus Rabelais prepares readers for his final move, in which the creature seems to vanish into the larger contours of a myth.

Pantagruel compares the monster in the sixth and last description to the children of Anti-Nature (Anti-Physie ). "I am reminded of the form and appearance of Amodunt [glossed by editors as "Lack of Measure"] and Disharmony," declares the prince when Xenomanes finishes his fifth account. Quaresmeprenant's "strange and monstrous" psychophysiology shows a human being's natural parts thrown into such disarray that their combination engenders the opposite of Harmony and Beauty (the latter, says Pantagruel, are Nature's children). Anti-Nature's children are grotesque, although the elements of their bodies — like the things to which Quaresmeprenant's bodily parts have been compared in previous descriptions — are not themselves ugly, taken singly. But their assemblage has gone awry. Amodunt and Disharmony have heads and feet that are round, like bouncing balls. Anti-Nature interprets these spherical parts as evidence of divine kinship because the heavens are made in and move with circular tracery. Her children's arms have been joined to the torso so that they reach toward the back rather than front of the body. This, their mother explains, is an exceptionally well-made adaptation to defense; the front of the body is sufficiently defended by teeth. "Their eyes stood out of their heads on the end of bones similar to heels, with no eyebrows, and they were as hard as those of crabs . . . . They walked on their heads, continually turning cartwheels, tail over

[37] See the beginning of Part One.

[38] According to Screech, Rabelais, 368, these particulars come respectively from a "popular proverb" (no documentation) and from Erasmus's Adagia 1: 4, 74.

head, with their legs in the air"; all this to their mother was evidence of spherical perfection.[39]

Pantagruel expresses horrified disdain for such opinions and such creatures. These superb little Carnival machines are denounced by the hero in ways opposite to the gay and tolerant manner that Pantagruel favors on other occasions. Anti-Nature's "evidence drawn from brutish beasts" is absurd; her arguments are devoid of "good judgment and common sense." Pantagruel's amusing myth-tale is didactic in the usual manner of contemporary humanism; the place for functions like those lodged in heart and head is on high, while that of the limbs and their brutish, material functions is below. Mixing and inverting the two levels, head over heels, disgusts the prince, and prince he does seem to be here, defending the high as properly high and the low as forever low.[40]

[39] QL, 32, 64.9–50. Stanley Eskin's description of the mythic tale by the Italian humanist Coelio Calcagnini (Rabelais's immediate source) in "Physis and Anti-Physie: The Idea of Nature in Rabelais and Calcagnini," Comparative Literature 14 (1962): 167–73, has been largely replaced by the more thorough analysis in Richard Cooper, "Les 'contes' de Rabelais et l'Italie: une mise au point," in La nouvelle française à la Renaissance, ed. Lionello Sozzi (Geneva, 1981), 196–98. Eskin, Cooper, and other editors of and commentators on this passage from the seventeenth century to the present have been puzzled by Pantagruel's comment that he found the story of Nature and Anti-Nature among ancient authors, since Calcagnini lived in the sixteenth century. Pantagruel's reference is probably to those aspects of Calcagnini's tale found in Plato's Symposium, where Aristophanes tells the tale of the originally eight-limbed spherical nature of the three sexes — male, female, and hermaphroditic (189A–191D). Aristophanes' humanity runs about turning cartwheels, and these queer beings are turned in opposite directions, just as in Rabelais's account. They are children of the sun, earth, and moon (hence their spherical shape) and are treated in Aristophanes' story as natural, although troublesome to the gods. Unlike Calcagnini too, and unlike the immediate Rabelaisian context, the Platonic story is explicitly comic.

[40] M. M. Fontaine has discovered a marvelous visual parallel to the children of Anti-Nature in a series of drawings offered by Giovanbattista Braccelli to the Medici princes of Florence in the later sixteenth century. The drawings show geometrized assemblages of mechanical toy people with, indeed, legs and arms hooked on backwards in one case. See Fontaine, "Quaresmeprenant" 106–7, 112, no. 32. But Fontaine's assertions about Rabelais's mechanical-anatomical perceptions, again here drawn into parallel with Vesalian anti-Galenic method, both conflict with and move far beyond the Rabelaisian text: "Quoi qu'on en dise, on pas que le corps de Quaresmeprenant forme une masse où tout fonctionne en rapports continus [sic ] . . . . Le dessin imaginaire du corps permettrait de mieux comprendre la dénonciation de la comparaison et de l'analogie au profit d'une perception globale du corps, telle qu'elle se livre dans les images littéraires de Rabelais . . . . [Here intervene Braccelli's illustrations; see also the analysis of Vesalius's mode of modeling the body, 102–4.] De telles solutions qui visent un corps entier dans ses gestes, dans ses volumes mobiles et ses activités propres, ne sont possibles qu'après Rabelais et Vésale" (104–6).

Elevated in this way to the level of a metaphysical parable, the contrast between Nature and Anti-Nature may be applied to anything. In this passage it is applied with fine fury to Pantagruel's — and Rabelais's — pet hatreds. For Anti-Nature has continued to procreate, says Pantagruel. From her have come empty-headed barbarians (Matagotz ), churchly bigots (Cagotz ), hypocrites (Caphars ), church-serving beggars (Briffaulx ), and popemongers (Papelars ),[41] and the zealots who have attacked Rabelais's writings: les Maniacles Pistoletz, les Démoniacles Calvins, imposteurs de Genève, les enraigez Putherbes. Pistoletz refers to Guillaume Postel, Calvins to John Calvin , and Putherbes to Gabriel DuPuyherbault. These men, as I have mentioned, had denounced Rabelais's books in the 1540s.[42] They, like the other bigots and fools, like homosexuals (Chattemites ) and like "misanthropes" (literally, Canibales ) are all "deformed monsters, made in Nature's despite."[43]

The section of Rabelais's episode that served in traditional examples of the Carnival-Lent genre to introduce the hero and his adversaries ends here with an unexpected break in the fictive frame and a reference to the author's context of threatening religiopolitical fanaticism. The never-never story of Pantagruel and his friends is brought sharply back from the high seas of fiction to a society of jealously striving men full of vituperative suspicion. However unfamiliar readers might be with

[41] Many of these were banned in the same vituperative terms from Thélème Abbey in G, 54, 173; cagotz and caphars are attacked by Rabelais with the same comic excess in his own name at the end of the prologue to the Third Book, TL, P , 351. Matagotz seems to be invented from Greek mataios, empty, vain, foolish, and Gotz, the Goths, the humanists' synonym for barbarians. Cagotz is a synonym of bigot. A caphar seems to be a religious hypocrite (Rabelais uses it in G, 54, 173 with the adjective empantouflez, slippered). Demerson glosses briffaulx as "glutton" in a note to G, 54, (Oeuvres de Rabelais, 197, n. 9) but Le Double, Rabelais anatomiste, 410, n. 1, cites a pre-eighteenth-century poem and an ecclesiastical authority indicating that it meant a lay brother licensed to beg by papal brief; that is, a marginal religious person of low economic and social status.

[42] See ch. 1. Screech, Rabelais, 209–11, 314, 325, 371, gives details about their publications. See L. Thuasne, Etudes, 404–13, 447–50, for the fullest account of Calvin's attacks on Rabelais and E. Droz, "Frère Gabriel DuPuyherbault," on the especially sharp attacks of DuPuyherbault. DuPuyherbault is often called "de Puy-Herbault" in older literature.

[43] See Appendix 3 on Canibales and ch. 5, n. 8, on Chattemites .

Pistoletz as a reference to Postel or with Putherbe, a Frenchified version of the Latin form of the monk DuPuyherbault's name, they could scarcely be unaware in 1552 of the third person, a man whose name is not deformed and whose seat of power is announced without disguise: John Calvin of Geneva.

To the dedicated Pantagruelists among Rabelais's "well-disposed readers," those who had read the author's prologue to the short edition of the Fourth Book in 1548, this break in the text would have been even more striking. These readers would perhaps have noticed the deletion of Dr. Rabelais's violent attacks on his detractors in the 1552 prologue, only to find these same references to caphars, cagots, matagots, and catamites here, accompanied not only by the names of particular persons but also by an embracing philosophical denunciation.[44] Such readers, and still more Rabelais's modern critics, are forced by this shift from paratext to text to consider the meaning of the literary tactic. If Rabelais the real author, the person representing Dr. Rabelais and Alcofribas no less than Quaresmeprenant and Pantagruel, decides to name names in this way, what does it imply? Beyond its literary and eventually its philosophical sense, what are the moral and political implications of rending the symbolic fabric asunder in this manner?

In literary terms placing the denunciations here would tend to conceal them from nonliterary eyes, even while making the rhetoric sharper. Rabelais perhaps decided to make the shift from prologue to this part of the text because he supposed that inquisitorial committees would be less inclined to work their way through a comic depiction of Carnival-Lent customs in search of heresy than to peruse prefatory materials. The shift carried forward Rabelais's tactics of concealment. In political terms the particularized attack and its placement express new boldness and old shrewdness in facing adversaries. In moral terms they intensify the impression gained from many passages scattered through the novels. This gaily affable writer is irascible. Rabelais, as Michael Screech has commented, was a good hater.

Rabelais has sometimes been called a naturalist philosopher, a thinker who identifies man's destiny with his nature-embedded, material existence. For such interpretations Rabelais's myth of Nature's and Anti-Nature's progeny assumes special importance. It is one of the few places in the novels where such imputed naturalism is propounded in general although still humorous terms.

[44] See pp. 34–35 above.

In Rabelais's Italian humanist source Nature pleads her cause against Anti-Nature before the council of the gods, the gods award their favor to Nature's children, and the latter then convert men to religious reverence for nature while Anti-Nature and her progeny vanish. But in Rabelais's version Anti-Nature's children show no sign of defeat or disappearance; perhaps, then, there will never be a lack of "brainless folk" and "fools" who accept with eagerness such confused arguments as Anti-Nature employs. If that is so, what does this ending of the fable imply? Does it present a philosophically open-ended view of the human scene or a somberly pessimistic idea of human nature as distracted in frightful and threatening proportions from the worship of Nature by the silly mechanisms of Anti-Nature? Or does it signify something else entirely? Should one say, moving beyond these futurological alternatives in the authorially self-inclusive manner suggested by Michel Beaujour, that Pantagruel's eruption of anger over the pullulation of Anti-Nature's children represents the snorting helplessness of someone who confusedly perceives an enemy more pitiless and implacable than even religious orthodoxy: the limitations of his own most far-reaching, metaphysical thought, thought that in Rabelais's case is, so far as his extant writings reveal, synonymous with literarily embedded thought[45]

The Rabelaisian text is caught in its own toils, Beaujour maintains, caught in an endless babble of linguistic self-generation because it — the spirit incarnate in this text — cannot imagine a way of "perceiving culture and language as humanly founded, in spite of all its efforts to escape the alienations implied in the antithesis of Nature and Supernature." Rabelais recognized, as a Christian, the discontinuity between Supernature and Nature. The relation between God, on the one hand, and man and the world, on the other, was not a smoothly unfolding emanation like that proposed in Neoplatonic thought. The hiatus between Supernature and Nature seemed to Rabelais, according to Beaujour, so great as to involve man in inescapable alienations, the most

[45] "Futurology" is not my neologism but that of certain present-day sociologists. It directs attention to an allied and more optimistic aspect of Rabelais's thought that has long interested scholars: his concept of human progress. See my "Ideas of Temporal Change and Cultural Process in France, 1470–1535," in Renaissance Studies in Honor of Hans Baron, ed. Anthony Molho and John Tedeschi (Florence, 1971), 710–11, 742–45, and Abraham C. Keller, "The Idea of Progress in Rabelais," PMLA 66 (1951): 235–43. See also Bakhtin's treatment of Rabelais's views of the future, discussed in ch. 10 below.

crucial of which was "Culture." "Culture (that which is no longer Nature yet is not Supernature) takes refuge with Rabelais in the practice of literature as satire." Man the maker of literature, disconnected from, yet finding no other ultimate source for Nature or Culture than Supernature, has no way of founding his activity in his own being, in an "anthropology" or science-art of the human, and so he is "the prisoner of anti-nature." His linguistic activity "cuts up the world, anatomizes it, but never succeeds in catching hold of the true thread of its coherence." In the end, therefore, "Rabelais's practice of language never lays hold upon Nature except as Anti-Nature does, delimiting objects so that they become disjecta membra, haunted by their nothingness: [this idea of] language is incapable of speaking about the world without drying it up."

Rabelais/Pantagruel, or rather the textuality their configuration procreates — is that who Quaresmeprenant/Anti-Nature is[46]

[46] The quotations are from Beaujour, Le jeu de Rabelais, 138–39, but they concern the problematic developed throughout the book and are stated with special clarity in the conclusion, 174–77. I have pulled Beaujour's affirmations in a certain direction and have perhaps extrapolated from them more than he would do. I offer the interpretation hypothetically, adopting a perspective posterior to Rabelais's own, the dangers of which were mentioned with respect to Beaujour in ch. 1, n. 56. The question is not whether such hypotheses can be "justified" by the text but whether the critic juxtaposes them clearly to the text, so that their contextual otherness can be seen and judged. In this connection one must admire the manner in which M. M. Fontaine (see nn. 23, 40) proposes her interpretation of Quaresmeprenant. Whatever one's reservations about the particulars of her exegesis, the open-minded, gaily ironic mode of presentation makes her article an intellectual feast in the best Pantagruelian sense.

4—

What Makes Sausage-People Fight?

After the long wrenching, dismantling, and finally mythicizing movement of the Quaresmeprenant section, the two-chapter interlude in which Pantagruel kills a whalelike sea creature provides action-filled relief.[1] Alcofribas resumes his narration, and the Pantagruelians behave as they normally do: Friar John is brave, Panurge is cowardly, and Pantagruel dispatches the spouter with impossibly perfect marksmanship. The whale-monster is hauled ashore on Ferocious Island where some of Pantagruel's sailors carve it up "to gather the fat of its kidneys" — just as the inhabitants of one of the Faroe Islands are shown doing on Olaus Magnus's map (see Fig. 3). Faroe/Ferocious Island, we have already been told at the beginning of the episode, is the home of Farfelu Sausages.[2]

[1] Action-filled but not less richly symbolic: see n. 5 to Part Two and the references to Paul Smith's analysis of the physétère episode. Because the physétère appears immediately after Pantagruel recounts the myth of Antiphysie, and because Panurge at the approach of the sea-monster begins crying with fear, Smith comments: "Tout se passe comme si Panurge se laissait tromper par l'homologie phonique qui lie le physétère à Anti-physie." False or negligent etymology: the sea-monster's name, from Greek physeter, means "the blower"; a whale blows out water from its spout; conversely, when Pantagruel's arrows hit the monster in the right spots, the blower ceases to blow and is deflated. Hence, concludes Smith, "La victoire de Pantagruel sur le monstre peut se fire comme celle de l'Harmonie sur le Chaos, de I'Esprit sur la Matière, de Physis sur Antiphysie" (Smith, Voyage et écriture , 112, 116–17; see further 120–21). Such conclusions draw much metaphysics (and some hasty identifications of Pantagruel's significance generally) from a slight myth and its aftermath. But Smith, like Beaujour and Fontaine, juxtaposes his conclusions clearly to the text (see my ch. 3, n. 46). Smith, incidentally, identifies Quaresmeprenant in the traditional way with Lent (ibid., 120).