PART 2

SOURCES AND TRADITIONS

The Impact from Abroad:

Foreign Guests and Visitors

Peter Selz

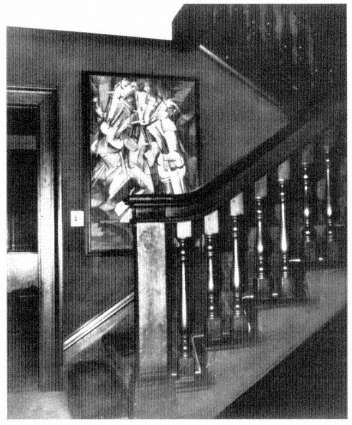

Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 found its first private home in an expansive brown-shingle house in Berkeley (Fig. 34). Frederick C. Torrey, a San Francisco antique and print dealer, had seen it at the Armory Show in New York and purchased it in May 1913 for $324.[1] When Torrey visited Duchamp in Paris soon after, the artist made him a gift of a preparatory sketch. The canvas, Duchamp's chef d'oeuvre up to that time, was the work at the Armory that defined modernist painting. Torrey displayed it in his Berkeley home near the University of California campus, where it served as a background for debates by the Berkeley faculty, often invited for Sunday discussion sessions. A man with a profound understanding of contemporary art, Torrey lectured on new developments in European art in general and on Duchamp and Francis Picabia in particular. Only recently have historians begun to acknowledge his influential role in the story of California modernism. He "should now be remembered for the valiant battle he waged—in the face of resistance and adversity—to foster a better understanding and acceptance of modern art on the West Coast."[2]

Torrey was primarily a businessman, however: in 1919, when the painting had trebled in value, he sold it to Walter Arensberg in New York. Two years later Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 returned to California with other major works by Duchamp, Constantin Brancusi, and other modern masters, when the Arensbergs moved to Hollywood. There they made their important collection of mainly European modern art accessible to many visitors until the early 1950S, when it entered the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

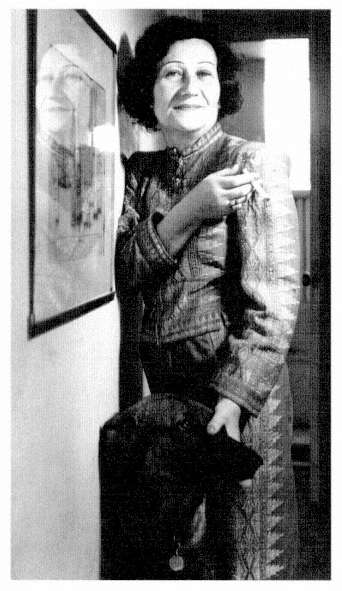

Through the Arensbergs (and other former New York friends such as Beatrice Wood), Duchamp established a California connection. A frequent guest of the Arensbergs in Hollywood (Fig. 35), he also visited San Francisco, taking part in 1949 in the historic "Western Round Table on Modern Art." This symposium, organized by Douglas MacAgy, the perspicacious director of the San Francisco Art Institute, brought together some of the leading thinkers and makers of modern art: Gregory Bateson, George Boas, Kenneth Burke, Alfred Frankenstein, Robert Goldwater, Darius Milhaud, Andrew Ritchie, and Frank Lloyd Wright, in addition to Duchamp.

Figure 34

Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase ,

No. 2, in the Frederick C. Torrey home, Berkeley, ca. 1913.

The Oakland Museum Archives of Cahfornia Art.

This essay describes how international (primarily European) modern art made its way to California: the forms it took, the conduits, and the most significant responses. In other words, what influences were available to interested California artists, and how did they incorporate them into their work? In the history of American art, the Armory Show is generally cited as modernism's "wake-up call." Although the Armory Show itself did not travel west of Chicago, San Francisco organized a much larger, if less radical, exhibition of modern art: the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 displayed no fewer than 11,400 works in Bernard Maybeck s resplendent Palace of Fine' Arts.[3] Although most of the work was conservative and retardataire , there was a sampling of paintings by the impressionists and the Nabis; a group of works by Edvard Munch; and, surprisingly, a section of forty-nine futurist paintings sent from Italy Because the futurists insisted on showing all together, their works were not exhibited at the armory in New York. Instead, they made their American debut in San Francisco.

Figure 35

Louise and Waiter Arensberg with Marcel Duchamp

(right ) in the garden of their Hollywood home, August

17, 1936. Photograph by Beatrice Wood, courtesy

Beatrice Wood papers, Archives of American Art,

Smithsonian Institution.

The Bay Area painter Gottardo Piazzoni said of futurism: "I have been associated with the movement since its beginnings and am acquainted and in correspondence with the man [sic ] who started it in Italy"[4] —a truly amazing statement from an artist whose work is characterized by muted tonalism. Piazzoni, who was born in Switzerland, came to California in 1886 and studied at the California Institute of Design; but he returned to Europe, studying in Paris, before settling in San Francisco. His large expansive landscapes in the former San Francisco Public Library (George Kelham, architect, 1916) are the essence of calm, in total contrast to the dynamic explosions of the futurist painters.

The Americans Ralph Stackpole and Otis Oldfield had also gone to study in Paris, where they remained for some time during the early part of the century. Like many of their countrymen, both artists came under the influence of the modernist trends they encountered there. The large decorative sculptures Stackpole carved for the 1939 World's Fair at Treasure Island and for the San Francisco Stock Exchange were stylized

figures, owing a good deal to the cubism of André Lhôte. Paris-born Lucien Labaudt, who settled in San Francisco in 1911, had also been influenced by Lhôte, with whom he remained in close contact. Lhôte and Labaudt collaborated in the exhibition Ecole de Paris , mounted at the East West Gallery of Fine Arts in San Francisco in 1928, which included paintings by Picasso, Georges Braque, Georges Rouault, and André Derain, among others, and thus made works by contemporary French masters accessible to the Bay Area audience. In 1930, when Matisse stopped in San Francisco on his way to Tahiti, Labaudt was host to him. The Lucien Labaudt papers in the Archives of American Art indicate a "serious professional exchange between Paris and the American West Coast."[5] With his wife, Marcelle, Lucien Labaudt established the Labaudt Gallery, important for young and emerging artists like Richard Diebenkorn, who had his first solo exhibition there. The "flexibility" of the creative situation in California is suggested by Laubaudt's, Oldfield's, and Stackpole's work in both the modernist and social realist idioms, as in their contribution to the Coit Tower murals of 1930.

Somewhat related to Stackpole's work in style, but typically more exotic in subject matter, was the work of Maurice Sterne. Sterne, born in Latvia and brought to New York by his mother, had studied at the National Academy of Design. He went to live in Italy and Greece and traveled to Egypt and Bali, returning to the United States during World War I. He settled in New Mexico, where he was married for a time to the legendary Mabel Dodge, who served as the catalyst for the colorful artists' and writers' colony in Taos. In 1933 he was the first American artist to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Subsequently he came to San Francisco to teach at the California School of Fine Arts. Sterne brought a cosmopolitan spirit as well as a modern idiom to the school. As Hassel Smith, a student there at the time, recalled: "Sterne's approach to drawing from the model (nature) was a revelation. I have no hesitation to saying that to whatever extent my intellect has been engaged in the joys and mysteries of transferring visual observations in three dimensions into meaningful two dimensional marks and shapes I owe to Sterne."[6]

William Clapp, who was born in Montreal, had gone to Paris to study at the Académie Julian as well as the Académie de la Grande Chaumiére before settling in Oakland in 1917. He became a member of the Society of Six, whose small colorful paintings were open to a wide range of influences, from French and American impressionism to the visual abstractions of Kandinsky. In 1918 Clapp, who was probably the most conservative member of the Six, was appointed curator and later director of the Oakland Art Gallery, a city museum housed in the Municipal Auditorium; when it moved to it, present quarters, it became the Oakland Museum. It was without a doubt the most adventurous exhibition space in the Bay Area until Grace McCann Morley founded the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1935.

In his enthusiasm for the avant-garde, Clapp was receptive to Galka Scheyer. Scheyer, born in Braunschweig, had come in 1924 to New York, where she had little success in promoting the work of four German modernists—Wassily Kandinsky, Alexei

Figure 36

Alexander Hammid, portrait of Galka Scheyer.

Photograph courtesy Norton Simon Museum.

Jawlensky, Lyonel Feininger, and Paul Klee—whom she designated the Blue Four. In 1925 she traveled to the West Coast, where she encountered a more favorable response to the German artists. Ironically, none of them was actually German: Kandinsky and Jawlensky were Russian, Klee was Swiss, and Feininger American-born—but they worked in Germany. Scheyer (Fig. 36) had become an apostle of modern art during World War I after seeing Jawlensky's work and falling in love with the artist. After

visiting Feininger, Klee, and Kandinsky at the Bauhaus in Weimar, she decided to bring the work of all four artists to the New World. She came to the Bay Area hoping to obtain a lecturer's position at the University of California, but Eugen Neuhaus, who headed the art department, was no friend of modern art. By 1927, however, she seems to have been a highly successful teacher at the Anna Head School, which was then in Berkeley. She was befriended by Clapp, who appointed her the European representative of the Oakland Art Gallery. The first Blue Four exhibition opened in Oakland in 1926 and went from there to Stanford. Galka Scheyer wrote her artists in Germany that they were being shown "in the most distinguished university in California. . . . Stanford University is worth its weight in gold."[7] But apparently she had miscalculated, for she sold one of Jawlensky's pictures for only twenty-five dollars.

In 1929 the Oakland Art Gallery organized an exhibition including works by Kandinsky that was circulated by the Western Association of Art Museums. With these exhibitions Scheyer offered an ambitious (and expensive) lecture series, titled "From Prehistoric Art to the Blue Four." She would show some five hundred lantern slides, charging those who attended $250 for the series. The fee for the exhibition to the participating museums was at times as low as twenty dollars. When expenses in one instance ran higher than expected, Scheyer suggested a small additional charge, but Clapp explained to her, "If one makes changes in arrangements either financial or otherwise, it irritates those who plan an exhibition. It costs money and entails labor to make changes and if it happens more than once, an art gallery director is apt to become disgusted and to avoid in the future all such exhibitions."[8]

Another exhibition presented by the Oakland Art Gallery in 1929 was entitled European Modernists . It included, not the work of French painters, as it surely would have on the East Coast, but that of Emil Nolde, Carl Hofer, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Max Pechstein, Oskar Kokoschka, and Feininger. While modernist art both in Southern California and on the East Coast looked almost entirely to France, that of Northern California, especially the East Bay, looked to Germany.

The largest exhibition of works by the Blue Four opened at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in the spring of 1931 and then moved to Oakland, where additional works were included in the show. It attracted considerable attention and caused a great deal of controversy. Among those inspired by it was Howard Putzel, who was particularly keen on Feininger's work, discerning his sensitized fusion of the human figure into a precisely structured abstract design.[9] It is evident that Putzel recognized the significance of formal qualities in works of contemporary art. A few years later, in 1934, he organized the first Miró exhibition on the West Coast in San Francisco's East West Gallery of Fine Arts, followed by other surrealist exhibitions at the Paul Elder Gallery on Post Street. In 1935 Putzel moved to Los Angeles, became a major critic, a promoter of modern art, a dealer in it, and eventually the chief advisor to Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery. In New York, he also became a passionate advocate of abstract expressionism; it was he who first brought Jackson Pollock to Peggy

Guggenheim's attention. Galka Scheyer, meanwhile, had gone to Mexico, where she established contact with the painters there, curated an exhibition of works by Carlos Mérida, and became friends with Diego Rivera and Rufino Tamayo. Rivera, his own work of social and political significance notwithstanding, indicated his full understanding of Kandinsky's works when he wrote:

The painting of Kandinsky is not an image of life—it is life itself. If there is a painter who merits the name creator, that painter is Wassily Kandinsky. He organizes his matter as the matter of the Universe was organized in order that the Universe might exist. I know nothing more true and nothing more beautiful.[10]

Filled with admiration, Rivera arranged for a Blue Four exhibition at the Biblioteca Nacional in Mexico City in 1931. For some time the great muralist had wanted to come to the United States to see the feats of engineering—the skyscrapers, highways, and bridges. He was known north of the border as the master artist, able to combine progressive politics with a significant modern style of mural painting, accessible to the general public. However radical his politics, his first project in the United States was a large fresco in the new building of the San Francisco Stock Exchange, designed by Timothy Pflueger. At first Rivera, a member of the Communist Party in Mexico, was refused entry by the State Department, which feared to admit radicals. When he was finally allowed to enter the country, Maynard Dixon, the well-known painter of western landscapes as well as social realist urban scenes, told the press:

The stock exchange could look the world over without finding a man more inappropriate for the part than Rivera. He is a professed Communist and has publicly caricatured American financial institutions. I believe he is the greatest living artist in the world and we would do well to have an example of his work in a public building in S.F. But he is not the man for the Stock Exchange.[11]

When the Mexican painter and his wife, Frida Kahlo, arrived in San Francisco, they were feted and lionized. In 1930 he was given a one-man show at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor. The exhibition traveled to Los Angeles, where his work was also exhibited at the Dalzell-Hatfield Gallery and at Jake Zeitlin's famous bookstore. In fact, Rivera exhibitions took place throughout the state, and the artist was offered substantial lecture fees at the University of California at Berkeley as well as at Mills College. Living in Ralph Stackpole's studio, he completed the mural for the stairwell of the Stock Exchange Lunch Club, which occupies the tenth and eleventh floors of the Stock Exchange Tower. Almost thirty feet high, it represents the productive resources of California, its agricultural and industrial workers, its ranchers and miners and gold prospectors, and a large allegorical figure of California, modeled after the famed tennis champion Helen Wills Moody.

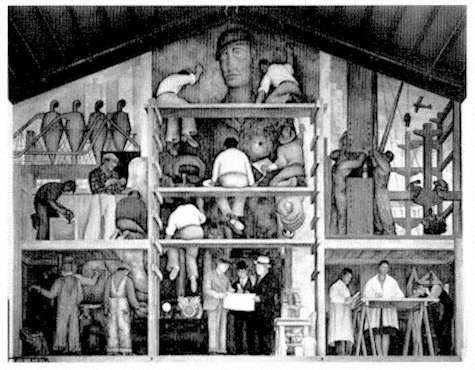

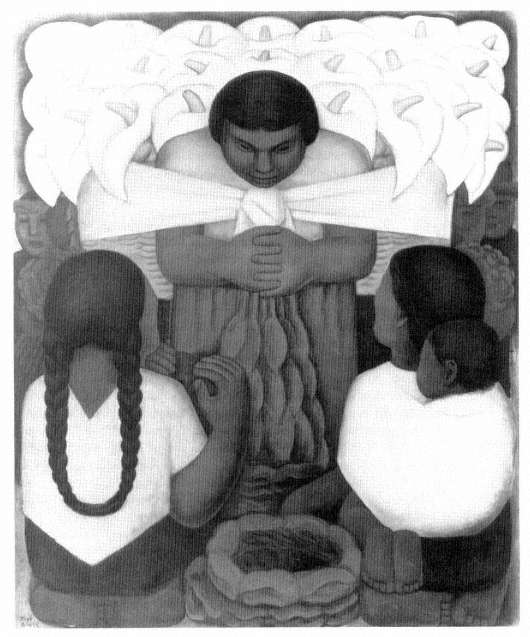

Figure 37

Diego Rivera, The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City , 1931.

Fresco. San Francisco Art Institute. Photograph by David Wakely.

Rivera's next mural was the fresco (Fig. 37) at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute). Here the artist subdivided the painting into cells, separated by a scaffolding—the symbol of architectural construction. On the bottom we see Pflueger, the architect of the Stock Exchange; Arthur Brown, Jr., who had designed the school; and William Gerstle, the donor of Rivera's $1,500 fee for the fresco. Engineers, mechanics, painters, and masons are seen at work, with a gigantic figure of a worker gazing out at the apex. The artist portrayed himself sitting on a plank in the very center, a feature some found objectionable. The Seattle painter Kenneth Callahan complained about the artist's "fiat rear . . . hanging over the scaffolding in the center. Many San Franciscans chose to see in this gesture a direct insult, premeditated, as indeed it appears to be. If it is a joke, it is a rather amusing one, but in bad taste."[12]

Neither Rivera's rear nor his politics but rather his conviction that modern art had to be abstract prompted Douglas MacAgy, the brilliant, forward-looking, but autocratic director of the California School of Fine Arts, to find the mural too representational

and too conservative. But that was fifteen years later. Back in the 1930s Rivera's work had a great impact on the paintings of the twenty-five artists who decorated the newly built Coit Tower, the "simple fluted shaft" designed by Arthur Brown's firm for the top of Telegraph Hill. Rivera became the role model, both stylistically and ideologically. It was he, together with his great colleagues José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, who inspired the Philadelphia painter George Biddle to persuade his former Harvard classmate and friend Franklin Delano Roosevelt to establish the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) that was the predecessor of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Biddle wrote to the president that the younger artists of America, like the Mexican muralists, were conscious of the

social revolution that our country and civilization are going through and . . . would be eager to express these ideals in a permanent art form if they were given the government's cooperation. They would be contributing to and expressing in living monuments the social ideals that you are struggling to achieve.[13]

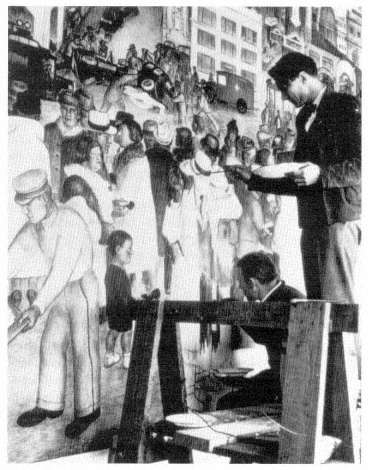

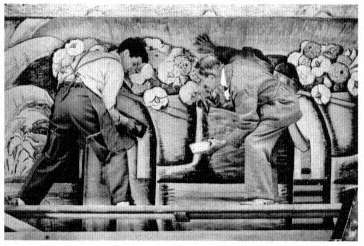

The PWAP was put in place throughout the country. In San Francisco the Coit Tower murals were its first and most important achievement. Victor Arnautoff, the project director, had worked with Rivera in Mexico City and Cuernavaca in 1930 and 1931. Other Californians, including Clifford Wight and Bernard Zakheim, had also worked with Rivera on various walls. In Coit Tower they followed the old Italian tradition of fresco buono as interpreted by Rivera and his colleagues. Arnautoff's Metropolitan Life (Fig. 38) is closely related in its general composition to Rivera's murals at Mexico's National Palace, while Stackpole's Industries of California (1934) resembles the great murals Rivera had completed at the Detroit Institute of Arts a year earlier. The physical types of the striking workers in California Industrial Scenes , by John Langley Howard, also have their source in Rivera's paintings. The bold modeling of figures and the chromatic scheme of subdued earth colors is clearly indebted to Rivera's work. Finally, the frescoes in the tower embody Rivera's belief that the new mural art could help in the revolutionary struggle to create a more equitable social and political system.

In 1934, when Diego Rivera's mural at Rockefeller Center in New York was destroyed, primarily because of objections to the inclusion of a portrait of Lenin, the newly formed San Francisco Artists' and Writers' Union joined a nationwide protest against this act of political vandalism. During the Pacific Maritime Strike, which occurred later that year, the Hearst press in San Francisco started a red-baiting campaign against the Coit Tower murals, which indeed included radical passages: Arnautoff's newsstands displayed the Masses and the Daily Worker but no San Francisco Chronicle ; Bernard Zakheim's Library includes a copy of Das Kapital ; and, most irritating to conservatives, a hammer and sickle appeared next to the National Recovery Administration's blue eagle in the mural by Clifford Wight.

An extended battle ensued, and eventually the Recreation and Park Department

Figure 38

Victor Arnautoff at work on the fresco Metropolitan Life in Coit Tower,

San Francisco, 1934. Photograph courtesy Public Works of Art Project

papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

and the Art Commission locked up Colt Tower, calling the works of the muralists a "typical Rivera stunt." The most offensive element, Wight's Soviet emblem and its accompanying slogan, "Workers of the World Unite," were overpainted, and eventually the tower reopened.

By 1930 the influence of the Mexican muralists was firmly established in California. Even before Rivera was commissioned to paint his mural in the Stock Exchange Tower, Orozco had gone to Los Angeles to execute the dramatic and powerful Prometheus fresco (1930) at Pomona College. Orozco's monumental work in Frary Hall on that campus came to inspire Rico Lebrun to create his mural Genesis (1966) in the loggia of the same building. In 1932 Siqueiros, the third member of Los Tres Grandes, completed a large outdoor mural on Olvera Street in the center of the old Mexican section of Los Angeles. The mural, Tropical America , represents a man crucified on a double cross

with the U.S. eagle perched on top.[14] Soon disparaged as "Communist propaganda," it was covered over with whitewash within a few years and began to deteriorate. The Friends of Mexico Foundation, working with the Getty Conservation Institute, is now trying to preserve it, even if it cannot be restored to its original state.

The political and social message of the Mexican muralists seems to have had less impact in Southern California than in the labor-oriented and unionized city of San Francisco. The American murals that sprang up in Southern California were typified by the work of Millard Sheets, who, after his original contact with Siqueiros, turned toward pleasing ornamental wall decorations.

Because of the Mexican mural movement, California modernism was split along ideological lines. During the debate about the Coit Tower murals in San Francisco, Glenn Wessels voiced the opposition's view. He praised the communal spirit of the enterprise, but also hoped that the public mural artist would remain "upon the plane of high generalities with which the majority can agree, unless his purpose is dissension."[15] In other words, art should stay aloof in matters of politics.

Born in Capetown, South Africa, Wessels had also studied with Andrü Lhôte in Paris and had gone to Munich in the late 1920s to enroll in the school founded by Hans Hofmann. Hofmann had lived and worked in Paris before World War I and participated in the artistic revolution there. He was well acquainted with Matisse as well as Picasso, Braque, Sonia Delaunay, and Fernand Léger. But coming from Munich, to which he returned when the war broke out, he was equally aware of the avant-garde movements in Germany, especially the Blue Rider group led by Kandinsky, who believed in the spiritual quality of art. Hofmann's art school, founded in 1915, may have been the best place to learn the new approaches to painting; it attracted students from all over the world. Louise Nevelson, Alfred Jensen, and Vaclav Vytlacil, as well as Wessels, were among those who came from America. Wessels gave English lessons to Hofmann in exchange for his art classes.

At about the same time, the American painter Worth Ryder was a student at the Royal Bavarian Art Academy in Munich. When he met Hofmann in the summer of 1926 at the Blue Grotto in Capri, where the German painter had taken his summer students, Ryder was impressed with his ideas. Appointed to the faculty at the University of California in 1927, Ryder immediately set himself in opposition to the conservative Eugen Neuhaus. To strengthen his position, he invited Hofmann's student Vytlacil to teach at Berkeley and in 1930 asked Hofmann himself to teach summer school there. Wessels accompanied Hofmann on the boat and train and served as his interpreter; he also translated the original version of Hofmann's textbook on the teaching of modern art, Creation in Form and Color . While teaching, Hofmann made some brisk and lively drawings of the Bay Area. He accepted an invitation to return to Berkeley in 1931 to teach, and he also exhibited his paintings and drawings, first on the campus and then at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. The works in this,

his first American show, were very much in the School of Paris style, heavily influenced by Cézanne, Matisse, and Duly. Only in the mid-1930s did Hofmann again seriously develop his own work as a painter.

Hans Hofmann returned to Germany once more, but, with the political situation there deteriorating, he was glad to accept an appointment to the faculty of the Art Students League in New York in 1932. A year later he started his own school, presiding as a father figure over a generation of abstract expressionist painters.

Rivera and Hofmann had arrived in the Bay Area in the same year, 1930,[16] and both had a profound impact on the art of the region. But there could be no greater contrast than that between the social realists, for whom art was a weapon to change the social order, and Hofmann's teaching of art as pure form and vibrant colors interacting on the picture plane (Fig. 39). Hofmann changed the teaching of art at Berkeley. Erle Loran, John Haley, and Karl Kasten, all Hofmann's disciples, joined Ryder and Wessels on the faculty. Among those they taught was Sam Francis, who received his master's degree from Berkeley in 1950 before leaving for Paris and becoming famous. Years later, Hofmann gave a significant number of paintings to Berkeley. They are displayed at the University Art Museum,[17] which now has fifty paintings by Hofmann. San Francisco is the site of three major murals by Rivera.

In 1935 the San Francisco Museum of Art opened in the War Memorial Veterans Building. Its primary goal was to present contemporary art and its sources, a task for which its first director, Grace McCann Morley, was eminently suited. Feeling that the city needed to catch up on the early stages of modernism, she presented an exhibition of impressionist and postimpressionist art for the premiere of the new institution. This was followed in rapid succession by the Rivera retrospective and the Blue Four show already mentioned. During the late 1930s, before computers allegedly made things so much easier and quicker, Morley and her small staff organized as many as one hundred shows annually. Of particular importance was a large 1936 exhibition of paintings, sculpture, and graphics by Matisse, largely borrowed from Michael and Sara Stein, who had recently returned from Paris to the Bay Area, bringing their collection with them. The San Francisco Museum, modeled after New York's Museum of Modern Art, saw itself as the western outpost of the slightly older institution and showed many of MoMA's most consequential exhibitions. Between 1935 and 1940 these included African and Negro Art; Cubism and Abstract Art; Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism ; and Picasso: Forty Years of His Art . Clearly, an active East-West art axis, one that had important ramifications for the development of California art over subsequent decades, had been established.

It is well known that before and during the war, many of the leading European artists—Piet Mondrian, Léger, Jacques Lipchitz, and most of the surrealists—migrated to New York, giving a major impetus to the incipient New York School. But it is less well known that many of the major European artists also came to the Bay Area, primarily

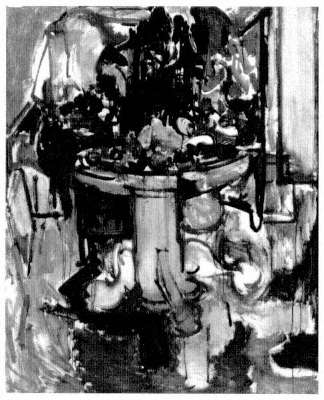

Figure 39

Hans Hofmann, Table with Fruit and Coffeepot , 1936. Casein

and oil on plywood, 60 1/8 × 48 1/8 in. University Art Museum,

University of California, Berkeley, gift of the artist.

because of Alfred Neumeyer, a man of astounding knowledge and cultural breadth. Born in Munich, Neumeyer had studied art history at the University of Munich with Heinrich Wölfflin before becoming Adolph Goldschmidt's student in Berlin and Aby Warburg's in Hamburg. He had received his doctorate from the University of Berlin and had worked at the Cabinet of Engravings in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum. Later he was appointed director of the Press Office of the Berlin museums, where he came in close contact with Germany's modern artists before they were defamed as degenerate. In 1935 he was offered a professorship at Mills College in Oakland. On the recommendation of his erstwhile fellow student Walter Heil, who had recently accepted the directorship of the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, Neumeyer accepted the offer, becoming the first trained art historian to teach the discipline on the West Coast. The position was greatly reinforced by Walter Horn's appointment to the Berkeley faculty in 1938.

Neumeyer maintained his contact with European artists and intellectuals. In 1937 he invited Walter Gropius, who had just been appointed head of the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, to teach a course in architecture in the Mills summer

session. Gropius had to decline, as did Thomas Mann, then living in Princeton, but the correspondence indicates that Mann considered giving a summer seminar on the Mills College campus in 1938 on humanism in the twentieth century or on art and democracy. Neumeyer built on the reputation Mills had achieved as a center of the humanities: the Russian-born sculptor Alexander Archipenko, who had immigrated to the United States in 1923, taught at the Mills summer session in 1933; his work was exhibited on the campus in 1934. Jules Romains had given a seminar on French culture there in 1936, as did André Maurois in 1941. In 1940, the year Darius Milhaud became professor of music composition, Neumeyer wrote a letter to the New York art dealer Pierre Matisse, suggesting that his father might want to leave France because of the war and consider coming to Mills,[18] but Matisse remained in Nice. As director of the Mills Gallery, a position he assumed a year after his arrival and held for many years, Neumeyer was able to bring in major artists to teach as well as to exhibit their work.

In 1936 Neumeyer organized an exhibition of Van Gogh's etchings. The same year he offered summer teaching and a show to Feininger (Fig. 40). The Bauhaus had been closed in 1933, and Feininger felt increasingly alienated and dispirited in his adopted country. He was glad to return to his native land after a fifty-year absence when the invitation from Mills arrived in his Berlin studio. With his wife, Julia, he sailed to New York and on through the Panama Canal to disembark in San Pedro. In Los Angeles he renewed his acquaintance with Galka Scheyer and Walter Arensberg, who owned some of his work, and then traveled on to Oakland, to teach at Mills. The exhibition of his work, lent mostly by his dealer, Karl Nierendorf, went on to the San Francisco Museum of Art, and some of his works were sold to San Francisco collectors. On his return to Germany, Feininger, who had been one of the country's most renowned artists, was featured in the infamous Nazi Degenerate Art exhibition, and 348 of his works were removed from German museums. Clearly his time in Germany had come to an end.

Neumeyer in the meantime had invited Oskar Kokoschka, who had fled to Prague. for the following summer. But when the Austrian painter was unable to come to Cali fornia, Neumeyer invited Feininger for a second summer session. Feininger later wrote to his friend Alois Schardt, the former museum director, "One day it will be noted that at the age of 65 I arrived in New York Harbor with two dollars in my pocket and had to start life anew."[19] At Mills a second exhibition was held in his honor that included forty oils and one hundred watercolors. In a lecture at the opening, Neumeyer pointed out that "nothing vague and indefinite exists in these landscapes and seascapes of crystalline form and crystalline light except the undefinable creative musicality of the artist's mind, which reminds us of Redon." The crystal, he declared, is the "symbol of medieval alchemists and mathematicians. The hardest and clearest of all minerals becomes a magic sign in their dream to conquer and explain the divine world. The hardest, the clearest, the highest organized mineral is not by chance the elementary form and symbol of Feininger's art."[20] At the time of the exhibition, Feininger himself cited Caspar David Friedrich's dictum, which he undoubtedly used during his many years of teach-

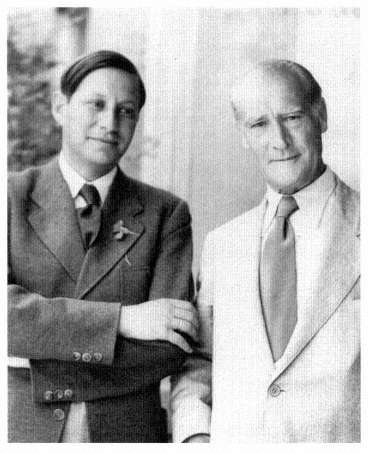

Figure 40

Alfred Neumeyer (left ) and Lyonel Feininger, summer

1936. Mills College Art Gallery, Oakland, California.

ing and which has lost none of its relevance: "The painter should not only paint what he sees around him, but also what he sees within himself; but if he sees nothing within himself, he should refrain from painting what he sees around him."[21]

This second Mills exhibition traveled along the West Coast to Seattle, Portland, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and San Diego. Feininger was enraptured by San Francisco and its rugged coast, where the remains of shipwrecks in the sea reminded him of his own fantasy seascapes. He said he would love to have remained on the Pacific coast but had to face the challenge of renewing his life as a working artist in New York. He arrived there in September 1937 and experienced almost another twenty years as a productive artist. This career "imperative," going to New York City, confronted virtually all serious artists in California.

In 1938 Alfred Neumeyer organized an exhibition of the work of Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, the important Brücke painter whose work, like Feininger's, was outlawed in

Germany. The artist wrote to Neumeyer that an exhibition in America at this time "reinforced his belief that there are still some places in the world with individual and nobler convictions."[22] A year later an exhibition of works by Kokoschka, who was then living in London, and a show of painting and graphics by Josef Albers, then teaching at Black Mountain College, were seen at the Mills College Gallery. Kokoschka presented the gallery with two crayon drawings, while Schmidt-Rottluff donated an early woodcut and the gallery also acquired a fine watercolor by him. A few years earlier two excellent Feininger watercolors had been added to the growing collection on the Mills College campus.

Neumeyer, however, was by no means interested solely in the rescue of German art and artists. He also sought out American artists, approaching those with the highest visibility at the time. He corresponded with Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, Leon Kroll, Eugene Speicher, and Frederic Taubes, asking each whether he might agree to teach summer sessions at Mills. Taubes accepted. Almost forgotten now—he is not listed in the indexes of most books on twentieth-century American art—he was well known at the time, having published eight color reproductions in a single issue of Limb magazine. Born in Poland, he had studied in Munich and was known primarily for his well-executed and colorful still-life paintings and portraits and for his books on the technique of oil painting. The major occurrence at Mills in the summer of 1939 was not the Taubes exhibition, however, but the presence of the Bennington School of Dance with Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Wegman, and Hanya Holm.

The most significant event for art, design, architecture, and art education in California may have been the exhibition The Bauhaus: How It Worked in the spring of 1940 at the Mills College Gallery. Circulated by the Museum of Modern Art, it consisted of Bauhaus objects, paintings, graphics, stage design, typography, graphic design, posters, and photography—in other words, the whole range of design of this century's most influential art school. This exhibition was actually only the curtain-raiser for the 1940 summer session, which brought leading faculty from the School of Design established in Chicago by László Moholy-Nagy—it was originally called the New Bauhaus and later became the Institute of Design—to Oakland. Moholy-Nagy arrived with the photographer, theorist, and painter Gyorgy Kepes; the painter Robert Jay Wolff; the weaver Marli Ehrman; the furniture designer Charles Neidringhaus; and the artist, designer, and craftsman James Prestini. This high-powered faculty taught courses in drawing, painting, photography, weaving, paper cutting, metalwork, modeling, and casting, all based on the Bauhaus belief in combining intuition and discipline in work that was meaningful in a technological world.

A large exhibition of work by the visiting faculty that summer comprised twenty-two paintings by Moholy-Nagy, twenty-four paintings and watercolors by Wolff, twenty photographs by Kepes, eleven trays and bowls by Prestini, and a large wall hanging by Ehrman. The classes were extremely successful, attracting both well-established

artists like Adaline Kent and art teachers from all over the West Coast. In a letter to Neumeyer, Alice Schoelkopf, supervisor of art for the Oakland Public Schools, expressed her appreciation of the program as an important new experience for the teachers in her district.[23] Indeed, the presence of the New Bauhaus faculty had an indelible impact on the teaching of art and design in the Bay Area: the Institute of Design's philosophy of education became a reality when William Wurster was named dean of architecture at the University of California in 1950. He appointed Jesse Reichek from the institute to create the basic design curriculum along Bauhaus lines, and Reichek, in turn, invited Prestini to return to the East Bay to help restructure architectural training at the university.

A good many years later Sybil Moholy-Nagy recalled in her biography of her husband:

By the time we arrived at Mills College, Moholy had lost most of his English vocabulary. During the trip he had insisted on speaking only German, which he loved. But even though he had lost his facility of speech, he had regained the spirit of high adventure which had been his most distinguished characteristic as a young instructor. He consented to a schedule of thirty teaching and lecturing hours a week. Together with five of his best teachers he put a group of eighty-three students through an intensified Bauhaus curriculum, including every workshop and every major exercise. Late at night or on the few free Sundays, we would drive into San Francisco. We loved this unusual town, its clean contemporary structure, the golden color of the wild oats on the hillsides and the red bark in the forest. In his painting Mills #2, 1940 Moholy has translated color-light interplay of the Bay region into a composition of glowing transparency. For the first time since we had left Europe, the atmosphere of a city seemed filled with an enjoyment of non-material values—art, music, theatre—not as demonstrations of wealth and privilege but as group projects of young people and of the community. The museums, co-operative units, studios, and schools offered a hospitality of the spirit that had been unknown to us in America. "One day I'll come back," Moholy said as we drove over the Bay bridge for the last time. "One day I'll have $10,000 in the bank and I'll spend two years in San Francisco."[24]

When Moholy was asked, however, to return to Mills the following year, he declined, wanting to identify his school with Chicago. He recommended Frank Lloyd Wright, who, predictably, was not available. Amédée Ozenfant was seriously considered until Léger, who had come to America in 1940, expressed an interest in coming to Mills—his fourth trip to America. He loved America's engineering feats, called New York "the greatest spectacle on earth," and was captivated by Harlem jazz. To see the country, he took the bus from Manhattan to Oakland. The United States, he said in 1949, "is not a country . . . it's a world. . . . In America you are confronted with a power in movement, with a force in reserve without end. An unbelievable vitality—a perpetual movement. One has the impression that there is too much of everything."[25] At

Mills he taught summer classes but found his own greatest inspiration in the swimmers at the college's pool. He had been working on his Divers series for some time but now painted on with greater energy, turning toward a more definite modeling of the body. He wrote that he was

struck by the intensity of movement. It's what I've tried to express in painting. . . . In America I painted in a much more realistic manner than before. I tried to translate the character of the human body evolving in space without any point of contact with the ground. I achieved it by studying the movement of swimmers diving into the water from very high.[26]

Léger made a number of interesting sketches and preliminary drawings during his stay at Mills, including a fine ink study he gave to the gallery, inscribing it, "Mills '41 en souvenir de mon séjour charmant ici. FLéger" (Fig. 41). He completed the final version on his return to New York, feeling the impact of Times Square. "I was struck," he wrote, "by the new advertisements flooding all over Broadway. You talk to someone and all of a sudden he turns blue. The color fades—another one comes and turns him red and yellow."[27]

An exhibition of Léger's work was installed in the Mills College Gallery and traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Art. On July 21, 1941, he gave a lecture, "L'Origine de l'Art Moderne," with ninety-four people in attendance. He expressed an interest in a permanent teaching position at Mills or, since there was no opening there, elsewhere in the country. Neumeyer wrote to university art departments and art schools from Seattle to Poughkeepsie on his behalf, but there was no opening anywhere for one of this century's greatest artists. A letter from the chairman of the art department at the University of Illinois is typical of the responses Neumeyer received:

I think I ought to say, confidentially, that our general University Faculty and the townspeople are so conservative in their point of view in art that I am afraid a meeting point for sympathetic contacts between them and the artist would be almost impossible to establish. I dare say that this situation is not a new one to you but seems so widely prevalent among the general faculty in our colleges and universities.[28]

During World War II and the immediate postwar period, artists abroad were isolated from those in this country. The energy in vanguard activity here thus centered on the new wave of American artists. Major exhibitions of abstract expressionism were installed at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, where Jermayne MacAgy was acting director, and at Grace McCann Morley's San Francisco Museum of Art. With the appointment of Clyfford Still to the faculty of the California School of Fine Arts both the leading schools in the city and the Art Department at Berkeley were teaching

Figure 41

Fernand Léger, study for The Divers , 1941. Pen and ink,

17 1/8 × 15 in. Mills College Art Gallery, gift of the artist.

abstract expressionist painting, although Still's and Hofmann's disciples worked in a very different manner.

Not until 1950 did a major European artist once more appear to teach in the Bay Area. Max Beckmann, who had gone to St. Louis from his self-imposed exile in Amsterdam in 1947 and had moved to New York in 1949, accepted Neumeyer's invitation to teach the Mills summer session in 1950. A sizable exhibition of his work from the collection of Stephan Lackner, now living in Santa Barbara, was held while he was on his way to Oakland.

In his diaries of that summer Beckmann wrote as much about his depression and the new war that had just broken out in Korea as about his trip to California. He enjoyed spending evenings with Neumeyer, Milhaud, and Alfred Frankenstein, the art critic for the San Francisco Chronicle , as well as taking his breakfasts at an American drugstore near the campus. A heart condition made critiques in his classes difficult for him, but he was able to work.

Beckmann made sketches for three paintings while at Mills: San Francisco, West-Park , and Mill in the Eucalyptus Grove , the latter two of the campus. The pictures were completed after his return to his New York studio. Painted from a vantage point high

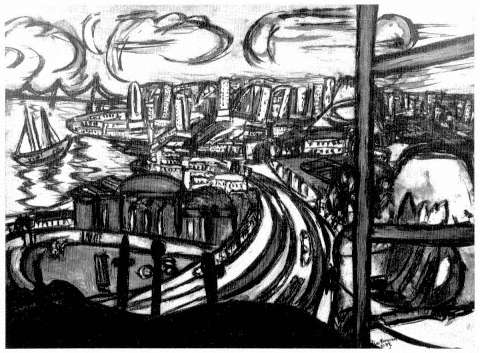

Figure 42

Opposite: Max Beckmann, San Francisco , 1950. Oil on canvas,

39¾ × 55 1/8 in. Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt.

above the Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco (Fig. 42) is a brilliantly colored dynamic painting with the curved arrow of Doyle Drive rushing past the Palace of Fine Arts toward the heart of the city, which appears to be vibrating. A crescent moon and a sunset appear in the eastern sky in this painting, which combines scenes of the city from different viewpoints. In the immediate foreground he has placed three black crosses, apparently stuck into the black earth of the curving ground. On the right above his signature is the fragment of a ladder,[29] a symbol he used frequently. Beckmann completed his greatest triptych, Argonauts , after his return to New York, where he died in December 1950.

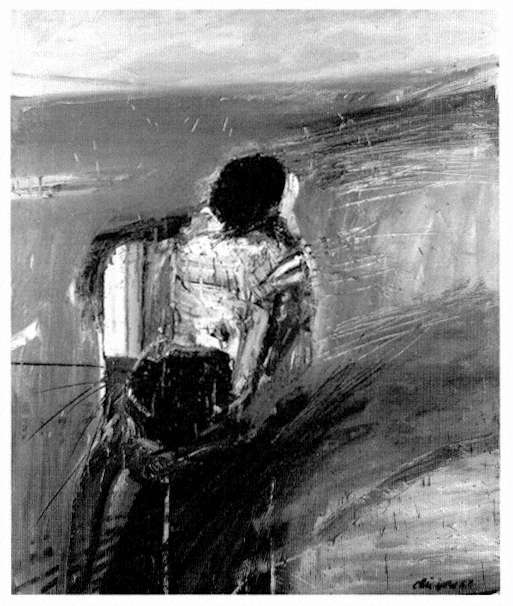

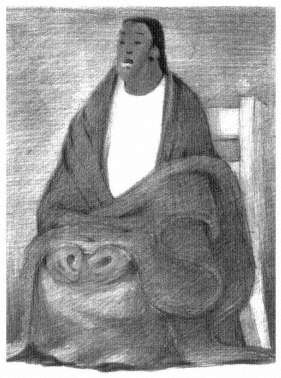

Among the students who registered for the Mills summer session that year was Nathan Oliveira. Oliveira's solitary figures, silhouetted against an unlimited space that is activated by the artist's vigorous brush (Fig. 43), owe a particular debt to the expressionist tradition. For Oliveira,

Beckmann symbolized the old world. Tradition, yes, but on the other hand renewing tradition—in the sense that the past was not being thrown away. It is as if he were saying, "This is it, this tradition, but I'm now dealing with my own reality." Beckmann starts out with a reality which is very fundamental. Over a period of years, and through many periods of transition, you see his work become more and more personalized, and the image becomes very particular. I picked that up and that's pretty much what I based my own work on.[30]

Figure 43

Above: Nathan Oliveira, Seated Man with Object , 1957.

Oil on canvas, 60 × 49 ½ in. Yale University Art Gallery,

gift of Richard Brown Baker, B.A. 1935. Photograph by Joseph Szaszfai.

Many California artists during the first half of this century, like artists elsewhere, decided to complete their training in Paris. What concerns us here, however, is the presence of European and Mexican art and artists and their impact on the art of California. It is safe to assume that the work of Duchamp and that of the futurists and expressionists elicited a response from California artists. Hans Hofmann at Berkeley and other major European artists like Feininger, Léger, and Beckmann at Mills College produced indelible, though not easily measurable, effects on California artists. And the brief stay of Moholy-Nagy and other members of the New Bauhaus faculty altered education and the praxis of the crafts, design, and architecture in the Golden State. Bay Area figurative painting is often seen as an indigenous development of the 1950s, but it was in fact part of an international movement to extend the emotional range and content of abstraction. As I have already noted, Nathan Oliveira acknowledges a direct debt to Max Beckmann. The two California artists who have achieved the greatest acclaim—Richard Diebenkorn and Sam Francis—were, though originally trained in the Bay Area, indebted to the pictorial condensation of sensations in the work of Henri Matisse. And the presence of Los Tres Grandes in California was continued in the widespread mural production in this state. These influences have fostered the pluralism of form and the multi-ethnic origins of current artistic production in the San Francisco Bay Area and throughout California.

Mexican Art and Los Angeles, 1920-1940

Margarita Nieto

Relations between Mexico and the United States have been characterized by conflict and tension, territorial and political imbalance. Since 1850, when Mexico lost its northern territories as a result of the Mexican-American war, the historical narrative of the relationship has consistently favored the "Colossus of the North," according to the poet Rubén Darío. The artistic links between the two nations—the other history—how-ever, pull in Mexico's direction. The country's three-thousand-year artistic history is one reason; another is Mexico's syncretic fusion of European and Mesoamerican cultures.

Mexico's controversial conception of modernity accounts for the richness of its visual language: along with European tendencies, currents, and aesthetics, Mexican art also incorporates the pre-Cortesian.[1] In contrast to the United States, whose art derives from Western, or European, sources, Mexico's fusion of the "other," pre-Cortesian, tradition with the Western tradition has created an art whose proportions and concepts challenge the traditional Western sense of balance and purity. The synthesis of these two aesthetics is Mexico's contribution to twentieth-century art. Mexico's contribution to American art during the twenties and thirties, through an intriguing network of cross-cultural experiences involving Mexican and American artists, critics, gallery owners, museums, and collectors, brought about a new awareness of that aesthetic.

In Los Angeles, founded by settlers who had come to California from Mexico, complex bicultural and multicultural narratives were spun out decades before such narratives had acquired a postmodern significance. Though traditionally, viewed as a city without a fine arts tradition, its film and television industries along with its popular art, public art, and muralism prepared a fertile ground for experimentation in the visual arts. Yet both critics and historians have long ignored the Los Angeles aesthetic, initially excluding or marginalizing, for example, the Chicano-Latino art movement of the sixties and seventies.

This history of cross-cultural influences is one of dichotomies and contradictions: on the one hand, the intellectual and aesthetic fascination with Mexican art and, on the other, the politics of discrimination against the Mexicans and Mexican Americans residing in the United States. It is also a history in which the passion for Mexican art coexists with an interest in economic development and investments in Mexico as a partial solution to the socio-economic problems arising in the United States during the Great Depression.

In the forties and fifties, the emergence of the New York School and abstract expressionism resulted in an about-face. With this original American art movement, not only did the interest in Mexican art fade, but American art history also seemingly chose to ignore the Mexican influences of the twenties and thirties. Moreover, although the United States had now assumed a new international importance as a political and economic power, the postwar period was also characterized by a nationalism bordering on xenophobia and a suspicion of things "foreign."

This xenophobic self-absorption was a reversal of the attitudes of the twenties and thirties, when the dynamism of the Mexican School of Painting served as a model for the artists and artistic movements in the United States. The government-sponsored muralist projects initiated in Mexico in the twenties were the example that George Biddle used in asking President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to fund the public arts project that became the Works Progress Administration. The American artists Ben Shahn, Philip Guston, and Jackson Pollock, among others, sought out the Mexican painters as teachers and masters.

The events, incidents, and exhibitions of the Mexican presence have been largely ignored or forgotten. What has remained are some references to muralism, the controversy over the Diego Rivera mural at Rockefeller Center in New York, and David Alfaro Siqueiros's Olvera Street mural in Los Angeles. Yet the presence of these artists, their work, and, most of all, this aesthetic is integral to the social and cultural history of American art: that presence was felt and reflected in the works of the artists Ben Shahn, Edward Weston, Jackson Pollock, Ralph Barton, and Philip Guston and the critics and writers Elie Faure, Walter Pach, Anita Brenner, Alma Reed, Frances Toot, and René d'Harnoncourt. It caught the interest of collectors and patrons such as Henry Ford, Abby Rockefeller, Nelson Rockefeller, Mrs. Sigmund Stern, and Mrs. Caesar Guggenheimer.

In Los Angeles, collectors and patrons of the Mexican artists included the screenwriters and directors John Huston, Dudley Murphy, Jo Swerling, Josef von Sternberg and Jean Hersholt. Prominent art dealers including Earl Stendahl, Stanley Rose, Howard Putzel, and Jake Zeitlin showed the works of Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros as well as those of Jean Chariot, Roberto Montenegro, Rufino Tamayo, and Federico Cantú. While Los Tres Grandes, the three famous muralists, continue to be the artists most often identified with the period, the painters Alfredo Ramos Martínez, Jorge Juan Crespo de la Serna, Jean Charlot, Francisco Cornejo, Luis Ortiz Monasterio, and José Chávez Morado lived, studied, taught, and worked in Los Angeles during these years

Moreover, the Mexican influence is evident in the works of the Los Angeles painters Alson Clarke, Phil Paradise, Phil Dike, Millard Sheets, Hugo Ballin, Leo Katz, Boris Deutsch, and Fletcher Martin.

But where did it all begin? Why did Americans invite Mexican artists north to adorn public and private buildings with murals, present workshops, teach in their institutions, and exhibit in local galleries—especially in light of the social and political interaction between Mexico and the United States, marked in the twenties in the Southwest by increasing bigotry and by disdain for Mexicans? The climate of hatred peaked in the thirties with a mass deportation of "Mexicans" that included American citizens, while the forties bore witness to the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial and the Zoot-suit riots, events deeply etched in the collective memory of the Mexican American community and later immortalized in Luis Valdez's musical dramas and films.

The enthusiasm for Mexican culture may be traced in part to two phenomena: the presence in Mexico of an American intellectual who has only recently been "rediscovered" by the United States, Walter Pach; and the American cultural climate, which separated theory and practice.[2]

Pach, a respected and well-established art historian, critic, and painter, served as a bridge between the School of Mexico artists—indeed, Mexican art in general—and North American art institutions. The American intelligentsia, moreover, savored both the social changes wrought by European upheavals in philosophy and aesthetics and the results of the socialist revolution in the Soviet Union. That what the intelligentsia learned from events in Europe could not always be applied to the deepest strata of American society is evident. Mexican art in the 1920s was avidly received while Mexican nationals in general were not—a contrast that suggests the difference in power between the cultural and the political establishment in the United States.

Walter Pach, according to William C. Agee, was "a catalyst, an advocate and spokesman for modern art and artists at a time when the modern movement was sorely in need of figures who could nurture it."[3] Born in New York to a well-to-do family of commercial photographers who did much of the work for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he earned a degree in art at the City College of New York. After studying painting with Robert Henri and William Merritt Chase, he moved to France in 1907 and became part of Leo and Gertrude Stein's circle. Pivotal in organizing the European portion of the 1913 Armory Show, he also became a lifelong friend and translator of the French art historian and critic Elie Faure; it was through him that Pach's curiosity about Mexican art was stimulated.

More important for our purposes, Pach served as a link between New York and California, where interest in, and support for, the Mexican muralist movement and for Mexican art were greatest. He also taught at the University of California, Berkeley, and corresponded with West Coast artists in Pasadena and Los Angeles.

Elie Faure's article on Jean Chariot and "Mechanisme" set off the chain of events, documented in the correspondence between Faure and Pach, that culminated in Pach's initial visit to Mexico in 1922, where he introduced Chariot to Diego Rivera. Faure had

known Rivera in Paris and, upon learning Pach was to go to Mexico, advised him to seek out Rivera.

Pach had already been in contact with Mexican intellectuals. As early as 1918 he had been visited by the Mexican philosopher and diplomat Samuel Ramos. Moreover, a letter of appointment and invitation to teach at the National University of Mexico was extended by the then secretary of the university, Pedro Henríquez Ureña, one of the outstanding Latin American intellectuals of the period. Pach visited Mexico during the execution of the Ministry of Public Education murals, mostly by Diego Rivera, and became acquainted with the entire body of Mexican muralists and painters. During that visit he began relationships with Rivera, Orozco, and Chariot and, later, the art dealers Alberto Misrachi and Inés Amor as well as the philosophers and cultural essayists Octavio G. Barreda and Alfonso Reyes.

Following Pach's 1922 visit, the Society of Independent Artists in New York, of which Pach was a founding member, along with Walter Arensberg and Marcel Duchamp, invited the "newly born" Society of Mexican Artists to show in New York. In a letter to Pach dated December 7, 1922, Diego Rivera thanked him in advance, outlined the spatial needs of the exhibition, and listed the names of the artists:

The group will consist—according to your wishes, we have made a list of thirteen names leaving two spaces (we are counting on fifteen spaces in terms of the 15 meters of wall that you've indicated) for the works by the children. [Apparently works by Mexican school children, most probably students of Ramos Martínez's Open Air Schools, were to be included in the exhibition.] We have decided on the following: [He then draws a sketch.] We shall each have 80 centimeters so that in any case there can be 20 centimeters between each canvas. We will also use the wooden rods that you mentioned.

The artists will be=Orozco José

Clemente=Chariot=Revueltas Alfaro

Siqueiros=Leal=Alba=Cahero=Bolaños=Ugarte=Cano=Nahui

Ollin =Atl = Rivera.[4]

This exhibition offered the Mexican artists an opportunity to show their work under the sponsorship of an established organization with connections to the European avant-garde. But it marked only the beginning of Pach's advocacy of Mexican art. In 1924 Pach published an article in Harper's "The Greatest American Masters," on the pre-Hispanic art of Mexico. He defended Rivera, both in the Rockefeller debacle of the thirties (with articles in the New York Times and Harper's ) and again when protests were launched against Rivera's Detroit Institute of Arts murals. He wrote articles on Mexican art for Art in America and introduced American intellectuals to the literary magazines Hijo Pródigo and Cuadernos Americanos , to which he contributed articles. He was the first foreign critic to write on the nineteenth-century painter Hermenegildo Bustos, and in 1951 he published a book on Rivera.

Plate 1

Ben Berlin, Duck-Cannon-Firecrackers, 1936.

Paper and foil collage on board, 19 7/8 × 16

in. The Buck Collection, Laguna Hills, California.

Plate 2

Edward Hagedorn, The Crowd , n.d. Monoprint/

oil on paper, 11 × 15 in. Getty Center for the His-

tory of Art and the Humanities. © Denenberg

Fine Arts, Inc., San Francisco.

Plate 3

Stanton Macdonald-Wright,

California Landscape , ca. 1919.

Oil on canvas, 30 × 22 1/8 in.

Columbus Museum of Art,

Ohio. Gift of Ferdinand Howald.

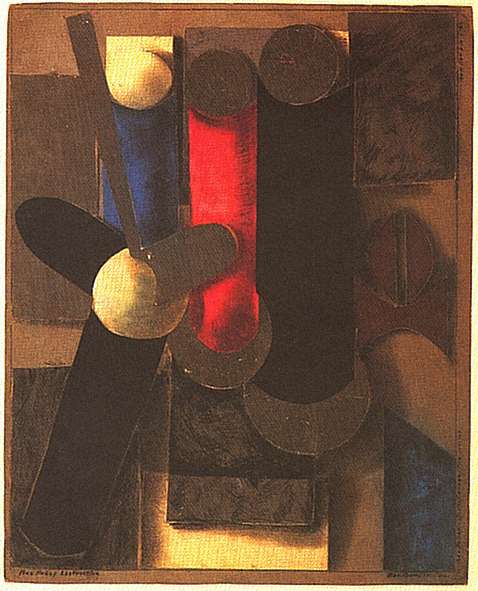

Plate 4

Peter Krasnow, K-1 ,

1944. Oil on board,

48 × 36 in. San Fran-

cisco Museum of Mo-

dern Art, gift of the

artist. Photograph by

Ben Blackwell.

Plate 5

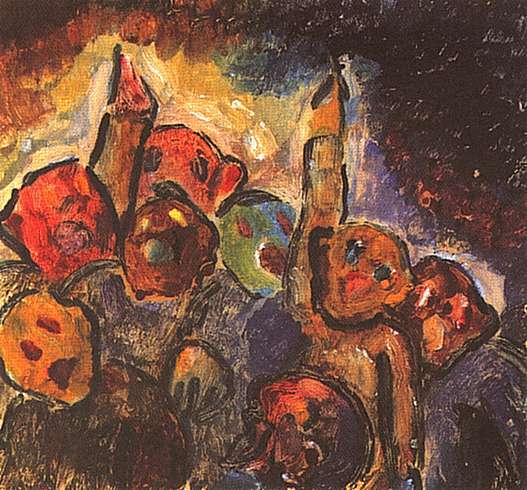

Above: Hans Burkhardt, VE Day ,

1945. Oil on canvas, 42 × 52 in.

Photograph courtesy Jack Rutberg

Fine Arts, Los Angeles.

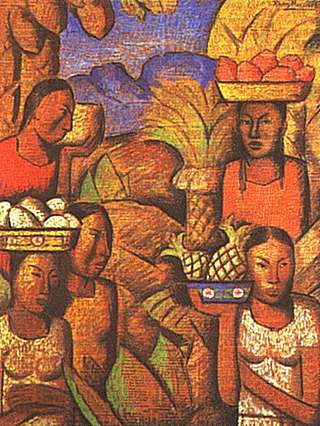

Plate 6

Right: Alfredo Ramos Martínez,

Vendedora de Frutas (Fruit Seller ),

1938. Tempera on newsprint, 21 ×

16 in. Mimi Rogers Collection, Los

Angeles, courtesy Louis Stern Galleries.

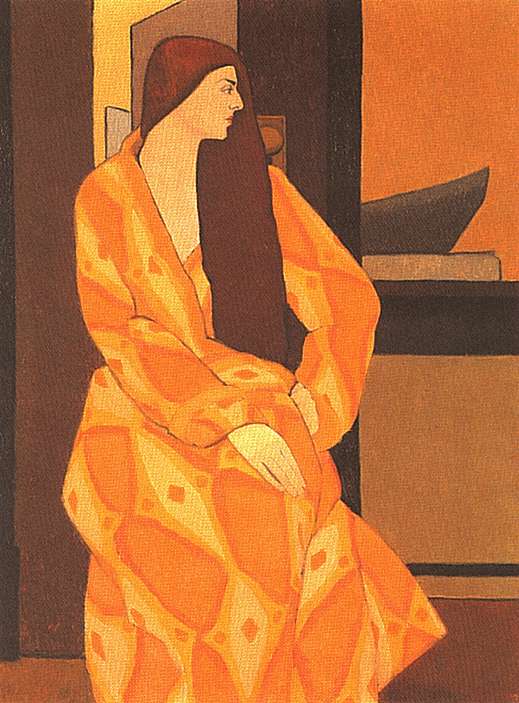

Plate 7

Opposite: Belle Baranceanu, The Yellow Robe ,

1927. Oil on canvas, 44 1/8 × 34 in. San Diego

Museum of Art, gift of the artist.

Plate 8

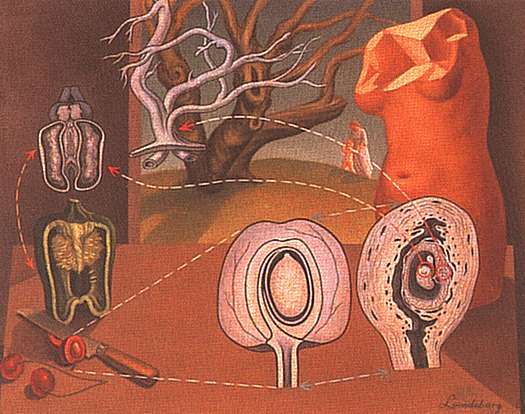

Helen Lundeberg, Plant and Animal Analogies ,

1934-35. Oil on celotex, 24 × 30 in. The Buck

Collection, Laguna Hills, California.

Plate 9

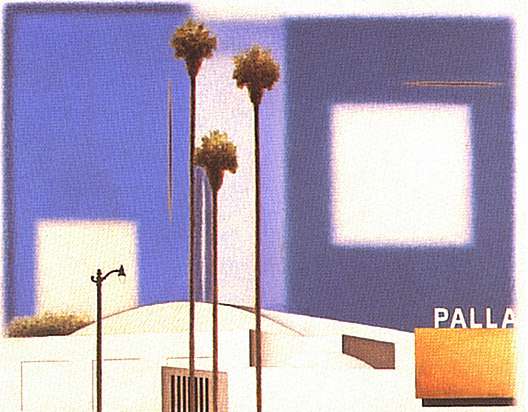

Edward Biberman, The Hollywood Palladium ,

ca. 1955. Oil on celotex on board, 36 × 48 in.

Private collection, Los Angeles. Photograph

© Douglas M. Parker Studio, Los Angeles,

courtesy Tobey C. Moss Gallery, Los Angeles.

Plate 10

Charles Howard, The Progenitors ,

1947. Oil on canvas, 24 3/8 × 34½ in.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco,

Mildred Anna Williams Collection.

Pach and his wife spent the academic year 1942-43 in Mexico, where Pach lectured under the auspices of the Institute for International Education. While his reasons for leaving New York may have been partly financial, Pach was warmly received in Mexico. Shortly after his arrival, the artist Carlos Mérida broadcast a radio essay publicly welcoming him to Mexico and giving a synopsis of Pach's article on Bustos. Letters to Pach from Jean Lipman of Art in America , John Strasser, and the painters John Sloan and Marcel Duchamp allude to his activity among the Mexican intelligentsia and artists. After returning to the United States, Pach delivered a lecture in Los Angeles, at the Earl Stendahl Galleries, on ancient and modern Mexican art.

In 1943, as Pach organized an exhibition of Rivera's work, scheduled for February 1944, at the Arts Club of Chicago, a group—consisting of Inés Amor, director of the Galería de Artes Mexicanas; Francisco Orozco Muñoz, director of the National Museum; Eduardo Villaseñor, director of the Bank of Mexico; Diego Rivera; José Clemente Orozco; Alfonso Noriega, Jr., secretary of the National University; and Octavio G. Barreda, editor of the magazine Hijo Pródigo —addressed a letter, dated June 9, 1943, to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ezequiel Padilla, asking that he name Walter Pach Mexico's cultural representative in the United States. They cited both the urgent need for cultural representation in the United States, given that "the American Government (. . . seems to be interested in better relations and there are indications that they are ready to appropriate funding for this purpose)," and Pach's reputation there. As "a native he could develop cultural propaganda without it being viewed as a paid assignment or as a foreign view; he could address his audience not as 'you,' but rather, as 'we.' " They underscored Pach's importance as a supporter of Mexican art in the United States:

Mr. Walter Pach, a famous painter, . . . author of nine books on art, as well as 200 articles, a student of the ancient art of Mexico for more than a quarter century, came to our National University by special invitation of Pedro Henríquez Urena. . . .

Upon his return to New York, he immediately organized a Mexican exhibition which for the first time, presented painters such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros and it must be said that it was he who successfully introduced our contemporary school of painting in the United States.[5]

Unfortunately for both American and Mexican art, nothing came of this petition.

The Walter Pach papers contain Pach's correspondence with Rivera, Orozco, and Charlot, among others. The letters Pach received from Mexico from 1922 to 1945 suggest the affection and respect the Mexican artists felt for him and show how he acted as an agent and cultural emissary for them. In the late forties the correspondence from Mexico diminished. After Pach's death his writing and critical approach went out of fashion and he was largely forgotten.

Pach's activity as a patron and advocate of Mexican art in the United States demands further investigation, for his wide-ranging interests and correspondence offer tantalizing glimpses into the relationships between Mexican artists and the international art scene. He was, moreover, an independent emissary, a person involved with art and artists for their sake alone. Although he was a friend of the Rockefellers, he was not involved with the foundations or with those institutions whose interest in Mexican art usually developed because of a political or economic self-interest.

Finally, Pach's bicoastal activities—his contacts with the California scene—indicate his awareness of the aesthetic differences between New York and the West Coast. As scholars explore the art scene in California during the twenties and thirties, it becomes increasingly evident from the lively gallery activity and the number of artists working in the state that art in Los Angeles was not dormant, or dull and provincial. Gallery spaces included the Biltmore Gallery, Barker Brothers, the Kanst Gallery, the Assistance League Gallery, the Friday Morning Club, the Ebell Club, Jake Zeitlin's Gallery Bookstore, Stanley Rose's Centaur Gallery, the Howard Putzel Gallery, the Frances Webb Gallery, and the Stendahl Galleries. In 1932 California Arts and Architecture magazine published a directory of California artists, craftsmen, designers, and art teachers.

A major contrast between the two coasts, however, and one that is still being assessed, involves the differences between the two areas as a result of California's shared history with Mexico and her geographical proximity, both issues in the interest shown by local artists in things Mexican. During the twenties in particular, some of these artists traveled to Mexico on painting trips, and local exhibitions often featured the works that resulted.[6]

But a contradiction remained between this appreciation of Mexico and its culture and the harsh reality of the discrimination against the Mexican population in California. Nonetheless, in 1923 Los Angeles was host to the first exhibition of Mexican art in the United States, a show organized by Xavier Guerrero, an artist who worked with Diego Rivera on the government-sponsored mural projects. Entitled The Arts and Crafts of Mexico , and sponsored by the Mexican government, the exhibition was held at the McDowell Club on Hill Street. It featured watercolors and drawings by Guerrero, Adolfo Best Maugard, and pupils of the art schools of Mexico. Originally it was to tour the United States, but because of problems with the United States Customs Office, it returned directly to Mexico from Los Angeles.

As a result of this exhibition, Guerrero first met Tina Modotti, who was then living in Los Angeles. Married to Roubaix de L'Abrie Richey, a French-Canadian poet, Modotti was performing minor roles in Hollywood films. Their studio was a center of bohemian life, frequented by the photographer Edward Weston, the writer Sadakichi Hartmann (who sometimes used the pseudonym Sidney Allan), and, in 1921, the Mexican archaeologist Ricardo Gómez Robledo. The relationship between Guerrero and Modotti was to flourish in Mexico after her separation from Edward Weston and during the time that she posed as a model for Rivera's Chapingo murals.[7]

These glimpses into the connections of Mexican and California artists suggest the need for a broader view of art and social history. In 1925 the Los Angeles County Museum at Exposition Park inaugurated a new wing with the First Pan American Exhibition of Oil Paintings . Opening on November 2, it was scheduled to close on January 31, 1926, but was held over until the end of March because of its popularity. Eighteen thousand people visited it on the first Sunday it was open to the public. It presented 230 artists from the United States and Canada and 145 Latin Americans. The artists from the United States included Thomas Hart Benton, Conrad Buff, Mary Cassatt, Alson Clarke, Maynard Dixon, George Ennis, Childe Hassam, Robert Henri, Rockwell Kent, Guy Rose, John Sloan, and Ralph Stackpole. The twenty-nine Mexicans included Jean Chariot, Joaquín Clausell, Fernando Leal, Roberto Montenegro, Juan O'Gorman, and Diego Rivera.

Of the Latin Americans, the Mexicans were the most strongly represented, both in works displayed and in prizes awarded. The Los Angeles Museum Prize ($1,500) went to Diego Rivera for his painting Día de Flores (Fig. 44). The museum announcement says that "Sr. Rivera is a leader of a modern group in Mexico—'Syndicate of Painters.' Walter Pach, the critic, calls him one of the greatest living artists." The Earl Stendahl Prize for landscapes in the Latin American section was divided between Manuel Villareal (Mexico) and Manuel Cabré (Venezuela). The Bivouac Art Club of the Otis Art Institute Prize for portrait or figure painting in the Latin American section was shared by Luis Martínez (Mexico) and María Ramírez Bonfiglio (Mexico).

During the 1920s the painter, muralist, and sculptor Francisco Cornejo, a native Baja Californian who lived and worked in San Francisco in his "Aztec" Studio, and the sculptor Luis Ortiz Monasterio, the father of Mexican modernist sculpture, collaborated on a theatrical work, Xochiquetzal . Originally performed in San Francisco by the Denis-Shawn Company, the work was staged at the old Philharmonic Auditorium on the corner of Fifth and Hill Streets in 1925. Cornejo also executed one of the side stages of the Mayan Theatre, a landmark of downtown Los Angeles.

Six years later, after murals had been completed at Pomona and San Francisco (José Clemente Orozco's Prometheus , 1930, and Diego Rivera's Allegory of California , the Stern mural, and Construction , 1930-31), two more exhibitions of Mexican art were held in Los Angeles. The first, a city-sponsored show held in conjunction with the August 1931 Fiesta de Los Angeles, was housed in the Plaza Art Center (renovated by R. M. Schindler) on Olvera Street. Facilitated by the Delphic Studios and the Weyhe Galleries of New York, it was curated by E K. Ferenc, the center's director, and Jorge Juan Crespo, who was then teaching art at the Chouinard Institute. The exhibition (135 works representing twenty-eight artists) included works by Cantú, Chariot, Clausell, Crespo, Pablo O'Higgins, Leal, Roberto Garcia Maroto, Siqueiros, Orozco, Mérida, Atl, Rivera, Julio Castellanos, Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, and five mural panels by Cueva del Río.

The second show was the Mexican arts show organized by the Rockefeller Founda-

Figure 44

Diego Rivera, Día de Flores (Flower Day ), 1925. Oil on canvas, 58 × 47½ in.

Los Angeles Count)' Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Fund.

tion and former ambassador Dwight Morrow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1930-31. Opening October 4, 1931, in Los Angeles, it featured lectures by the curator, René d'Harnoncourt, and by Homer Saint-Gaudens of the Carnegie Foundation and received a generous review in the Los Angeles Times by Arthur Millier.

The final "legitimizing" event for Mexican art in 1931 was a lecture, "The Revolution in Art Today," by the eminent French critic Elie Faure at the California Arts Club. In it, he recommended a new direction for American philanthropy:

Much as I love Spain, . . . I can call her conquest of the Aztecs nothing less than brutal. Yet, after the conquest, popular and individual expression of art arose in delightful and gracious forms which continue to the present day.

. . . I cannot understand why Americans who give millions for the restoration of Versailles, do not spend a few millions for the excavation of the . . . temples of Central America and for . . . museums which might be the greatest in the world. You have an obligation in that those Aztecs are your real ancestors, for people are related to the land the), live in rather than to their racial stocks.

But the visual presence of Mexican art went beyond exhibitions and lectures. It involved a continuity of influence through artists who taught, wrote, and created art in Los Angeles, introducing modernist aesthetics as well as fresco painting and muralism. It is difficult, however, to assess the importance of such figures as Jorge Juan Crespo, Alfredo Ramos Martínez, Francisco Cornejo, and Jean Chariot in easel painting, muralism, and sculpture. Even the influence of more famous artists, such as David Alfaro Siqueiros, has only partially been studied.

Painter, muralist, and art writer Jorge Juan Crespo taught at Chouinard from 1930 to 1938 with, in 1931, Richard Neutra and Hans Hofmann. Also in 1931 he curated the exhibition of Mexican art at the Olvera Street Gallery and executed for the Sons of Italy Hall a series of murals that disappeared before they could be documented. His writings on emerging European modernists in such catalogues as those produced by the Earl Stendahl Galleries reveal another aspect of the Mexican influence. Most Mexican artists had lived or studied in Europe before coming to Los Angeles. Thus they provided for the West Coast an alternative view of modern art, one that differed from that of the Atlantic seaboard.

Two important figures, Alfredo Ramos Martínez and Jean Chariot, had played major roles in the Mexican visual renaissance before moving to Los Angeles in 1930. Ramos Marténez had studied, lived, and worked in Paris before returning to Mexico in 1910.[8] The Open Air Painting Schools he founded, based on the Barbizon School principle, were probably the single most important influence on the School of Mexican Painting, for through them the study of art became available to everyone. Indeed, one of Ramos's first pupils at the school, established in 1913, was David Alfaro Siqueiros, who never forgot the debt he owed this master. Ramos also served as director of the

National Academy of Fine Arts. He first visited Los Angeles in 1925, when he accompanied an international exhibition of works from his schools to the First Pan American Exhibition. There he met William Alanson Bryan, then the director of the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Arts; when he returned in 1930, it was Bryan who facilitated his first exhibition.

Upon arriving in Mexico from France in 1922, Jean Chariot, who had studied painting and lithography in his native country, was invited to begin a woodblock workshop at one of the Open Air Painting Schools in Chimalistac, a suburb of Mexico City. There he introduced his technique, which he had acquired from the German expressionists. In doing so, he gave new impetus to the Mexican graphic movement, which had begun with José Guadalupe Posada at the beginning of the century. He worked with Rivera on the murals at the Ministry of Education, but as Rivera became the dominant muralist, Chariot and others turned to other fields of activity[9]

The sense of nationalism that pervaded Mexican painting by the mid-twenties may have motivated Chariot to come to the United States. It may have influenced Ramos as well, for José Clemente Orozco had criticized both the Open Air Painting Schools (because they were based on a European model) and Ramos himself. But the condition of his infant daughter may also have brought Ramos to the United States, for he had been advised that the regions dry climate was most suitable for the child. He arrived in Los Angeles with his wife and daughter in 1930, settled down, and began to work.

What is astonishing about Ramos's subsequent work is the shift in subject matter and technique. By experimenting with space and volume and exploring themes that had never before surfaced in his work, Ramos became a major exponent of the School of Mexico (see Plate 6). Even more intriguing is his acceptance by the art community in Los Angeles even as his contributions to the history of art in Mexico were being forgotten; they have only recently been reaffirmed. His first solo exhibition, at the Assistance League Gallery, featured works in the style that was to become associated with his name in California. They are characterized by a strong linear composition and reveal his preference for a palette rich in ochers and brownish tones in his portraits, in contrast with that of the flowers he sometimes included in his portraits and in his still lifes.

By 1933 Ramos had been commissioned to paint a mural at the home of the Hollywood screenwriter Jo Swerling. The year before, David Alfaro Siqueiros, at the invitation of Nelbert Chouinard, had come to Los Angeles to conduct mural workshops, and Ramos had taken him to meet E K. Ferenc, the director of the Olvera Street Gallery. That meeting led to Siqueiros's commission to paint the notorious mural Tropical America , but beyond that, it brought both painters in contact with a group of Hollywood intellectuals, including Swerling, Dudley Murphy, and John Huston, who supported their work and, in Siqueiros's case, his philosophy of using art for social change and revolution. The Swerling mural attracted other patrons, including Corinne Griffith, Edith Head, Alfred Hitchcock, and Beulah Bondi. In 1934 Ramos executed a set of murals for the Santa Barbara Cemetery commissioned by Mrs. George Washington

Figures 45 - 47

This page and next: Alfredo Ramos Martínez working oil the mural

in the Margaret Fowler Garden at Scripps College, 1946. Photographs

by Max Yavno. Courtesy Millard Sheets Estate, lent by Paul Bockhorst.

Smith, the widow of the famous architect, and the violinist and composer Henry Eichman; and in 1936, he painted a mural for the oratory of the Chapman Park Hotel (now destroyed).

A quiet man, Ramos was befriended by his peers, who admired him. Hugo Ballin introduced Ramos at his exhibition in the Santa Monica Library in 1933, and one of the first artists to visit him upon his arrival in Los Angeles was Leo Katz. But the most important of Ramos's artist friends was Millard Sheets, with whom he had a lifelong friendship. It was Sheets who arranged the commission for the Margaret Fowler Memorial Garden mural at Scripps College in Claremont (Figs. 45-47). Ramos completed it shortly before his death.