Merging with the Ritual Mask

The buccal masks on those two stelae from Veracruz are particularly significant for us since they suggest another way in which the spiritual art of Mesoamerica used the mask to "measure" the degree of contact with the world of the spirit of a

priest or ruler engaged in ritual, to depict what seem to be stages along the continuum that joins the worlds of man and the gods. If the costume of the impersonator is considered as an extension of the mask, a fully masked figure would be one showing no vestige of the human figure within, presenting to the viewer a figure visually indistinguishable from the god—a man become a god. Such figures exist in Mesoamerican art, but far more common are those, like the Zapotec opossum-masked impersonator (pl. 34), with fantastic animal or composite heads on human bodies. Many of the figures in the Postclassic codices, for example, are of this type, and the metaphoric import of such figures is to suggest that in some sense the ritual performer retains his humanity as he merges with the god in the liminal state.

Still further removed from total identification with the gods are those figures, like the rulers on the Veracruz stelae, who wear masks covering only a portion—often the mouth—of the human face. Since the face is of such fundamental symbolic importance in Mesoamerican spiritual art and thought, such partial masking clearly delineates a merging of man and god in a truly liminal moment, the moment of transition from one state of being to another. Finally, a number of gods are represented, especially in the artistic tradition of the Valley of Mexico, by fully human figures with faces that are unmasked but painted in specific ways, revealing even more fully than does the partial mask the human face of the "god." Thus, the degree to which the mask of the god covers the human wearer indicated metaphorically the stage of liminality experienced by the wearer, and in this way as well, as through the emergence of the face from the mask, Mesoamerican art portrays the liminal ground between man and the gods as a continuum, a progression from the realm of the spirit to the world of nature.

The use of such partial masks in Mesoamerican art and ritual goes back to the earliest times. Among the Olmec, in fact, there are far more buccal masks than full masks, a result, perhaps, of the Olmec emphasis on the were-jaguar mouth, the primary symbol of the rain god, but other buccal masks are depicted as well. Probably the best single example of the range of such masks in Olmec art can be seen in the six masked faces inscribed on the figure called the Lord of Las Limas (pl. 3) which Coe and Joralemon see as representing the six most important Olmec gods. Each of these faces is essentially human with a striking masklike treatment of the mouth area, and each of those treatments is represented elsewhere in Olmec art by a buccal mask. One of the clearest examples of such a representation can be seen in a small painting, designated Painting 7, in the grotto of the Oxtotitlán cave, the location of the X-ray representation (pl. 5) described above. This painting depicts the face of a human being whose mouth is covered by a fanged serpent mask. Both his jaw and upper face are fully exposed except for the scroll eyebrow he wears covering his own. His face is shown in profile, accentuating the outline and position of the mask, and the mouth is further emphasized by a small scroll element appearing before it which may be "the earliest known example of a speech glyph" indicating the man's ritual speech.[47] Numerous other examples of buccal masks exist in Olmec art on masks, celts, carved figures, and in paintings, suggesting the importance Olmec thought assigned to this graphic representation of liminality.

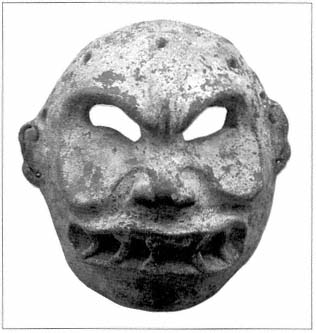

Contemporary with the Olmecs, villagers in the Valley of Mexico were making and using the small pottery masks (pl. 44) through which they created "the mythical half-human, half-animal" disguises referred to by Flannery in his characterization of early Mesoamerican religion. While these certainly do not look like buccal masks—they are always full human faces—the figurines that show them in place on dancing figures often show them covering only the lower part of the face and thus serving precisely the same metaphorical function as the buccal mask.

Given the early importance of the buccal mask in Mesoamerican spiritual art, we would expect to find it well represented in the art of the Classic period, and that expectation is fulfilled, although less fully in the art of the Maya than elsewhere. In Oaxaca, for example, a figure commonly depicted throughout the development of Monte Albán wears the buccal mask of a serpent (pl. 45) which Caso and Bernal see as related to Quetzalcóatl of the Valley of Mexico,[48] although one might

Pl. 44.

Ceramic mask of an old man, Tlatilco

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

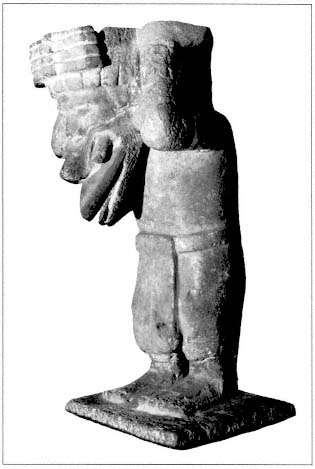

Pl. 45.

Ritual figure wearing buccal mask of a serpent, funerary urn,

Monte Albán (Museo Diego Rivera, México).

also see a strong visual resemblance to the buccal portion of the Cocijo mask (pls. 14, 15), particularly since the serpent is very closely related to both sacrifice and lightning, the two major themes expressed by the mask of Cocijo in its delineation of the great supernatural forces related to fertility and rulership. And buccal masks appear also in the art of Teotihuacán, illustrated most clearly in the so-called Jade Tlaloc mural at the apartment compound of Tetitla. The name is misleading because the priests pictured here do not serve Tlaloc but the god represented by the hook-beaked bird whose mask they wear as an emblem in their headdresses. Their buccal masks are related to that mask, but in what is clearly a significant similarity, both the masks in the headdress and the buccal masks are virtually identical to those worn by the central figure in the Tepantitla mural (colorplate 3). This similarity would suggest that the ritual focus of these figures was also fertility but a fertility that, as Séjourné indicates, may well be associated with creation in a more general sense.[49]

That symbolic meaning continues to be conveyed by the buccal mask in the Valley of Mexico during the Postclassic period where it is most clearly associated with Ehécatl (pl. 46), the aspect of Quetzalcóatl whose natural manifestation is the wind that "clears the roads" for the coming of the rains. That wind, blown through his buccal bird mask, is an obvious symbolic reference to the breath, or essence, of life, especially since man's creation was mythically attributed to Quetzalcóatl. And just as Ehécatl worked in tandem with Tlaloc to provide life for man's crops, so Quetzalcóatl symbolized the breath that along with blood symbolized the essence of life. Significantly, then, Ehécatl's buccal bird mask was the instrument through which that breath was provided by the god since by merging the faces of god and man, the buccal mask provided a metaphor for the movement of the essence of life from the world of the spirit to the world of nature.

Pl. 46.

Ehécatl, Aztec Atlantean sculpture, Tenochtitlán

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

Face painting and scarification provide the natural end to the progression from the full mask to the partial mask by revealing fully the human face while "marking" it with the symbols of the world of the spirit. Like the other forms of masking, face painting and the scarification that can be seen as a method of making that painting permanent have their roots early in Mesoamerican spiritual history. In the village cultures of the Valleys of Oaxaca and Mexico, faces, and whole bodies, were decorated with paint by the roller stamps commonly found in the remains of those cultures alongside figurines displaying the decorations. And among the Olmecs, the incised lines and designs commonly found on the faces of sculptured figures (pl. 3) and on masks surely represent the face painting and scarification worn by priests and other ritual performers. These practices in the cultures of the Pre-

classic prefigured even more elaborate forms of facial decoration in the Classic period. There is, for example, a good deal of evidence of face and body painting as well as scarification on the urns of Monte Albán,[50] and similar evidence exists in the ceramic and stone sculpture of the Maya, such as the Yucatec priest emerging from the jaws of a serpent found at Uxmal (pl. 40) and in the vase paintings of the Classic period.[51]

Such forms of facial decoration reached their apogee among the Classic and Postclassic period cultures of the Valley of Mexico. Faces of priests in the murals of Teotihuacán were often painted in designs signifying their functions, and stone and ceramic masks were decorated with mosaics or paint in similar designs (colorplate 8). These latter are funerary masks (discussed below), which are used in ritual at that most liminal of moments evidently requiring the identification of the physically dead man with the living god whom he was about to "become." Face painting served this function by allowing the death mask of the man, in idealized rather than portrait form at Teotihuacán, to be visible under the symbolic mask of the god. He remained himself—the human ancestor who could be contacted through ritual—while becoming a god.

The importance of face painting at Teotihuacán no doubt provided the impetus for its even greater development in the Postclassic in the Valley of Mexico. In our detailed consideration of the symbols that identified Huitzilopochtli, we delineated the method by which the Aztecs symbolized their gods. "Not many deities were regularly depicted wearing masks," Nicholson points out, but "facial painting was particularly diagnostic."[52] And even beyond the use of conventional designs to define particular gods, face and body painting were used in the codices and presumably on ceramic and stone sculpture to create symbolic combinations of gods in the same way that the mural art of Teotihuacán combined the features of masks to create unique "gods," as we have shown in our discussions of the Codex Borgia Tlalocs (colorplate 1) and the Tepantitla mural (colorplate 3). For the Aztecs, then, and no doubt for the cultures that preceded them, such face painting was the equivalent of a mask, as Sahagún's informants make clear in speaking of Huitzilopochtli: "His face is painted with stripes, it is his mask."[53] Such facial painting, as a mask, allows the simultaneous perception by the viewer of the human and divine identity of the wearer and forces the realization, exemplified by the Hopi children confronting the unmasked kachina, that the world of man and the world of the spirit are essentially one, a unity realized in the liminal state of ritual. Everything in Mesoamerican spiritual art combines to communicate that meaning, and the ritual mask is its single most important metaphor.

The Aztec god Xipe Tótec, Our Lord the Flayed One, provides what is probably the most compelling example both of the importance of face painting and scarification and of the liminal state of the wearer of the ritual mask. For the Aztecs, Xipe Tótec was the red Tezcatlipoca, and his face was painted red with horizontal yellow stripes, the Tezcatlipoca design with red substituted for black, as a visual indication of his identity. He was, however, often depicted with vertical lines through his eyes as well, which may represent a diagnostic detail by which prototypical Xipes can be identified very early in Mesoamerican art. Indeed, Coe identifies one of the masked faces inscribed on the Lord of Las Limas (pl. 3) as the Olmec prototype of Xipe Tótec for this reason,[54] and Caso and Bernal use those same lines to identify early representations of Xipe at Monte Albán in which the lines seem often to represent scarification.[55] Nicholson urges caution as such lines through the eyes are also found on the images of other gods among the Aztecs,[56] but our analysis of the system underlying the construction of symbolic masks suggests that those "other gods" may well be secondary masks symbolizing a merging of the qualities of Xipe with other primary god-masks.

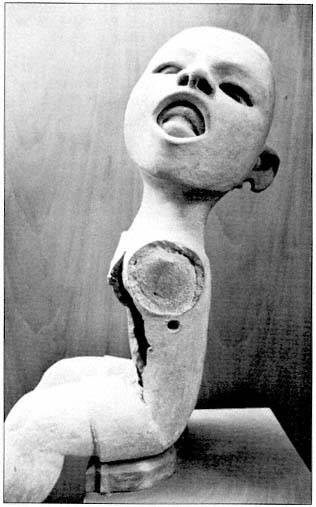

These facial details are not, however, the clearest and most common visual indication that we are in the presence of Xipe Tótec. Rather, that indicator is the unique "mask" worn by his priests and votaries in ritual and often depicted in art (pl. 47), a mask that is the skin of the face and body flayed from a sacrificial victim impersonating the god, donned in the final segment of a complex ritual, and worn for a period of time afterward by beggars before being buried in the temple of the god. In most representations of Xipe, all that is discernible in what seems to be a human face are the slit, buttonhole-shaped eyeholes, the openings of the nose, and the almost circular opening of the mouth through which the lips of the wearer can be seen. All else is hidden by the tightly stretched, flayed skin that has become the most macabre and most metaphoric of masks. The victim's hands hang limp at the wearer's wrists, and on many representations in the round, the lacing in the rear that holds the skin together is elaborately rendered.

Although there are various theories concerning the meaning of this ritual wearing of the victim's skin, the metaphor underlying the ritual is clearly the same as the central metaphor provided by the idea of the mask for Mesoamerican spirituality. The ritual and the art depicting it require us to consider separately the external covering and the essence of a living being. Most literally, the god is the essence; he is "the flayed one" who is revealed by the stripping away of his covering or mask according to the consistent logic of Mesoamerican sacrifice which always, at the sacrificial moment, opens or removes the outer to reveal the inner that is metaphorically the essence of life itself—

PI. 47.

Xipe Tótec, Palma Cuata, Veracruz

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

the god. When that now-removed covering or mask was donned by another in ritual, the wearer almost literally found himself within the skin of the god. And after the skin had been flayed from the sacrificed body of the impersonator, the flesh was cooked and eaten in a form of communion that reversed the metaphor by placing the god's essence within the ritual participant.

Seler's interpretation of this ritual as a metaphor for the living seed bursting forth from within its dead covering, resulting in the "new skin" of vegetation placed on the earth by the coming of the rainy season,[57] has been generally accepted since it seems to explain the timing of the calendrical ritual dedicated to Xipe and the reference in the mysterious and beautiful "Song of Xipe" to the god's donning of his "golden garment." As Seler suggests, the metaphor and the ritual refer both to sowing, as we have seen, and to the harvest where the skin becomes the metaphor for the husk of the corn. In thus embodying the agricultural cycle, Xipe reveals himself as an earth god whose concern is fertility and man's sustenance. Nicholson objects to this interpretation on the grounds that we have no native informant's testimony to support it, although he does agree "that fertility promotion was the central purpose" of the ritual. He seems more comfortable with a more general interpretation.

By donning such a terrible garment the ritual performer thereby becomes the deity into which the victim had earlier been transformed, literally crawls into his skin, so to speak—or, at least more directly partakes of his divine essence than by merely attiring himself with the god's insignia .[58]

Such an interpretation of the ritual accords with our idea of the mask as metaphor, and it is important to note that it does not conflict with Seler's interpretation; they approach the ritual on different levels. This seems a perfect example of the multivocality of what we have termed primary god-masks, and Séjourné provides still another level of interpretation that, we would argue, conflicts with neither of these. Calling Xipe "the most hermetic of all Nahuatl divinities," she sees the symbolism of his ritual as one in which the victim

is relieved (by flaying) of his earthly clothing and is freed forever from his body (an act represented by the dismembering of the corpse). The mystical significance of these rites is emphasized by the behaviour of the owner of the sacrificed prisoner. Not only does he dance, miming the various stages of the [ritual] combat and death; he also behaves towards the corpse as if it were his own body. This identification suggests that the slave represents the master's body offered to the god, the former being merely a symbol for the latter. The drama thus unfolds on two planes: that of the invisible reality, and that of finite matter, a mere projection of the former.[ 59]

Such an interpretation fits perfectly the most fundamental assumptions of Mesoamerican spiritual thought as we will outline them in Part II. And while it is probably true that the ordinary citizen observing this ritual was most aware of its gruesome fertility implications, it is just as probable that the priest saw in its series of oppositional relationships between inner and outer and living and nonliving the acting out of the most profound mystery recognized by Mesoamerican seers, that mysterious entry of the spiritual essence of life into the world of nature for which the mask stood in art and ritual as metaphor.

Sahagún indicates clearly the validity of such an interpretation of the ritual in his delineation of the relationship between the prisoner of war who was to become the sacrificial victim and his captor. The captor did not himself kill the captive but offered him "as tribute," the actual sacrifice being consummated by the priests. Furthermore, "the captor might not eat the flesh of his captive. He said: 'Shall I, then, eat my own flesh?' For when he took

the captive, he had said: 'He is as my beloved son."' That identity between captor and captive is made explicit in still another way:

They named the captor the sun, white earth, the feather, because he was as one whitened with chalk and decked with feathers.

The pasting on of feathers was done to the captor because he had not died there in the war, but was yet to die, and would pay his debt in war or by sacrifice. Hence his blood relations greeted him with tears and encouraged him .[60]

Thus the captive is simultaneously the god whom he impersonates and the alter ego of the all-toohuman captor; in the captive, the human and divine identities of the human being merge, and it becomes agonizingly clear that the human skin is but a mask hiding the divine essence that is revealed in the most literal and striking manner possible in the course of the ritual.

In this ritual, called Tlacaxipeualiztli, which means the flaying of men, the mask is no longer an instrument of ritual; here it becomes the very subject, a subject no longer metaphorical but now intensely, almost overwhelmingly, real. The impersonator of the god is stripped of his human covering to reveal the essence of life, which is then consumed so that it—literally—can sustain human life. Such a ritual unmasking as this makes the Hopi children's realization pale by comparison.

But in the final analysis, even this masked ritual is metaphoric. Like the Maya incised conch shell described by Octavio Paz, itself a potent symbol of the inner-outer dichotomy that fascinated Mesoamerican artists, Xipe Tótec in ritual

not only offers us the crystallization of an idea in a material object, but is also the fusion of the two into a true metaphor, not verbal but emotional. This kind of fusion of literal and symbolic, matter and idea, natural and supernatural reality, is a constant factor not only in Maya art but in that of all the Mesoamerican cultures.[ 61]

Such fusion is characteristic both of metaphor and liminality, for in both cases, at the moment of the juxtaposition of the two normally separated realms of experience, a recombination and transformation takes place through which a new reality is formed. In that moment, all previous definitions of reality are questioned and the new image created by the transformation enables man to transcend his mundane existence and, like Melville's Ahab, "strike through the mask" of nature to engage the very essence of life while protected by ritual from "going to pieces" in that encounter.

Two facts emerge from this relatively brief and partial survey of the vast subject of Mesoamerican masked ritual. First, throughout their long history, the cultures that made up Mesoamerican civilization explored every possible dimension of the metaphor of the mask. That metaphor was twisted and turned, looked at this way and that, and made to express every nuance of Mesoamerican spiritual thought. Second, in each of those expressions, the emphasis was always on the link between man and god, on the creation in ritual of a liminal space in which that linkage could be made. For this reason, perhaps, the emphasis in Mesoamerican masking seems overwhelmingly on the mouth—mouths open to reveal faces emerging, mouths composed of the features of a variety of natural creatures dominate masked faces, mouth masks partially cover human faces—announcing the fundamental Mesoamerican idea that man is an expression of the gods, that natural reality is a manifestation of spiritual reality.