The "New Woman" Versus the New Immigrant: the Cheat

Since the heroine of The Golden Chance is familiar to readers of sentimental literature, DeMille's articulation of the moral contradictions of a consumer culture goes further in The Cheat , an original screenplay by Hector Turnbull and Jeanie Macpherson.[41] Far more than class distinctions, the significance of racial difference in early-twentieth-century America clarifies the ethical dilemma of remapping gender roles at the site of emporiums laden with Orientalist fantasies. A narrative of an interfacial relationship in which a wealthy Japanese merchant (Sessue Hayakawa) brands a socialite (Fannie

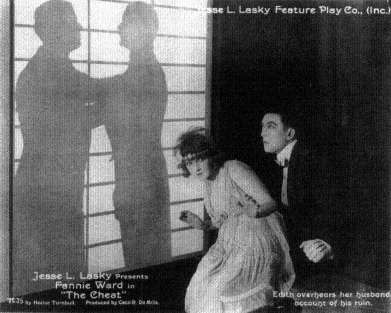

21. DeMille used low-key lighting and set design with a Japanese shoji

screen to dramatize an interracial relationship in The Cheat (1915), acclaimed as

one of the great films of silent cinema. (Photo courtesy George Eastman House)

Ward) with a hot iron bearing his trademark, The Cheat still inspires frisson. Since Japan fought on the side of the Allies during World War I, the villain's ethnic, if not racial, identity was altered in the 1918 reissue that is presently in circulation.[42] An intertitle in the credits preceding a shot of the Japanese actor thus reads, "Haka Arakau, a Burmese Ivory king to whom the Long Island smart-set is paying tribute." DeMille, interestingly, changed the shot of Hayakawa described in the script: "Tori (the Japanese name of the character) is discovered seated near tables, reading magazine or newspaper, and smoking. He is dressed in smart American flannels." According to changes pencilled on the script, the director called instead for a "Scene dyed Red —Black Drop—oriental lamp—brazier of coals—Tori takes iron away from object he is branding—turns out light—replaces iron in brazier—his face shown in light from coals—when he puts lid on brazier screen goes black."[43] Tori, costumed in a Japanese robe, is shown in low-key lighting as he inscribes his mark, a shrine gate, on an objet d'art. (Curiously, the Japanese term for a shrine gate is torii .) The film thus emphasizes the racial "Otherness" of the Asian merchant, who is both fascinating and repulsive, in the first of several dramatically lit shots that won critical acclaim. Further,

this scene, illuminated by the glow of the brazier on the desk and an offscreen light, was to be tinted red (as opposed to amber in the George Eastman House print) to emphasize the character's dangerous sexuality.

Richard Hardy, "a New York Stockbroker" (Jack Dean), is also seated at his desk in the credit sequence, but the shot is tinted blue rather than red or amber. Although the background has been darkened by a black drop, the character, who is feverishly poring over ticker tape and correspondence, is less dramatically lit. The businessman is thus represented as a rather pedestrian and unimaginative character. While the Japanese merchant enjoys wealth and leisure, the American stockbroker has yet to make his mark; he confides to friends who urge him to spend more time away from his desk, "It's for my wife, I'm doing it." An accepted social practice among the elite, the sexual division of labor in a consumer culture dictated that men earn and women spend as a sign of genteel status. Characteristic of middle-class marriage at the turn of the century, as Thorstein Veblen argues, was the role of the woman as a lady of leisure:

It is by no means an uncommon spectacle to find a man applying himself to work with the utmost assiduity, in order that his wife may . . . render for him that degree of vicarious leisure which the common sense of the time demands. The leisure rendered by the wife . . . invariably occurs disguised under some form of work or household duties or social amenities, which prove . . . to serve little or no ulterior end beyond showing that she does not and need not occupy herself with anything that is gainful.[44]

Such a division of labor, it would appear, was based on traditional gender roles, but the distinction between private and public spheres was collapsing in an era of self-sufficient and energetic "new women." Mrs. Potter Palmer, for example, annexed business circles to Chicago society, in fund-raising activities and thereby outmoded the practice of separate spheres for the sexes. Yet heterosexual relations in an elite social setting that contrasted with the sex-segregated world of Victorian culture were not necessarily based on equality.[45] Although DeMille represents Richard Hardy as the victim of his wife's extravagance in The Cheat , such a narrative strategy disguises actual control of the purse strings. As Veblen concludes, the wife is "still unmistakably . . . chattel in theory; for the habitual rendering of vicarious leisure and consumption is the abiding mark of the unfree servant."[46]

Significantly, the script of The Cheat juxtaposes the figure of the glamorous socialite with her maid in the credits. "Dressed in smart evening gown—Maid fitting the gown to her . . . Edith revolves slowly to get effect as though standing before a mirror. She must be pleased and happy." Although the maid is a minor character likely to be overlooked, her presence in the film is undeniably a reminder of the wife's analogous status. The uniformed servant, in other words, is a stand-in occupying the domestic

space appointed for the housewife.[47] As if to underscore this reality, the maid interrupts Edith in the act of taking Red Cross funds to gamble on the stock market in a scene that occurs early in the film. The socialite is seated in front of a dresser, but the mirror shows a reflection of the maid as she brings in folded laundry. DeMille deleted the servant in the credits, however, and introduced Edith in a long shot in which she is seated on an upholstered wicker chair and pets her dog, an animal that Veblen described as a useless and thus ideal token of wealth. So that women in the audience could get a closer look at her feathered headdress and jeweled bodice, Edith stands, advances toward the camera, and greets an unseen guest, a stand-in for the spectator. A bracelet winding up her right arm is molded in the form of a serpent. Although the leisured woman is clearly aligned with the vampire, her fashionable wardrobe and surroundings disguise her actual status both in the home and in a consumer culture.

DeMille's casting of Fannie Ward to play the self-indulgent socialite in The Cheat capitalized on the cult of celebrity that was well established in big-time vaudeville, theater, and opera before it was typified by film stars. A stage actress whose career had been interrupted by marriage to a British multimillionaire, described as "actually rolling in gold," Ward personified conspicuous consumption. According to news and magazine articles, "her jewels and gowns created a furor" during the years she graced British society as the mistress of a country house and a London mansion. When she decided to return to the United States in 1907, the actress had in tow "three maids, two automobiles, five dogs, and a wardrobe that, with her jewels, cost a million dollars." Appearing once again on the American stage, Ward dazzled the audience with her elegant attire. "From a purely fashionable standpoint," reported Theatre , "the costumes worn by Fannie Ward . . . are both a sensation and an inspiration. They are the last word in modishness. They typify the light hearted woman of fashion with a love for beautiful things and the means to gratify that love." As a film star relocated on the West Coast, Ward acquired a Florentine villa touted as "the most sumptuous photoplayer's domicile in the world." The actress apparently indulged her taste for luxury without experiencing the moral constraints of sentimental culture. Fittingly, she wrote an advice column in which she counseled women, "Express your own personality in every way. And let the world feel you are going to do this because of the individuality of the clothes you wear."[48]

Publicity regarding the details of Ward's elegant attire and villa illustrates the extent to which personal identity and celebrity status were based on commodities acquired in a fashion cycle. That is to say, the Protestant notion of character based on individual ethics and social commitment was being superceded by a modernist concept of personality defined in terms of consumer goods. Such a development further weakened the traditional

distinction between home and marketplace, or the Victorian practice of separate spheres for the sexes. Since respectable middle-class women in privatized households did not expect to function outside the domestic sphere, character remained a manly attribute.[49] When personality became a product of consumption, however, women assumed significance in the public sphere but at great cost to themselves. As the embodiment of com-modification in theatrical spectacles designed to stimulate acquisitive behavior, they occupied center stage but played a perverse role in the enactment of Orientalist fantasies. According to Williams, the "chaotic exotic" display of department stores was based on sheer accumulation that "becomes awesome in a way that no single item could be." An exotic decor, moreover, is "impervious to objections of bad taste"—taste being an Arnoldian concept with moral as well as aesthetic implications in genteel culture. Such a decor "is not ladylike but highly seductive . . . and exists as an intermediate form of life between art and commerce." Similarly, Said defines Orientalism as "a systematic discipline of accumulation."[50] Williams's distinction between "art and commerce" has limitations in a postmodernist age, but her argument about exotic decor, sensuality, and accumulation is well taken. Zola, for example, compares the orgiastic buying sprees of women on the sales floor with the obsession of an entrepreneur for a virtuous maiden in scenes in Au bonheur des dames that exemplify parallel editing. The impassioned relationship between buyers and commodities, in short, is one of temptation, seduction, and finally rape, a drama rendered even more titillating by the taboo of interracial desire in The Cheat .

DeMille borrowed an old plot device about gambling used in Lord Chum-fey and in The Squaw Man to precipitate the series of events leading to seduction and rape in The Cheat .[51] As treasurer of the Red Cross, Edith gambles with funds meant for Belgian refugees, the film's only reference to the events of World War I, so that she may ignore her husband's plea for economies and splurge on fashionable gowns. Symbolically, the Red Cross ball is held at Tori's mansion, described in the script as a "gorgeous combination of modern luxury and oriental beauty." Guests must traverse a Japanese bridge in a richly landscaped garden to leave the mundane world behind and to enjoy the pleasures of an emporium. Although her upper-class home has a living room accented with a dark, velvety portiere, plush upholstered furniture, and a grand piano, Edith is captivated by Tori's mansion, a site replicating exotic displays in department stores. Upon arrival, guests congregate in a large living room decorated with art objects that include a statue of a Buddha in front of a folding screen. Architecturally distinctive, the room is dominated by a magnificent hanging lantern and supported by dark columns with heavy gold ornamentation in Oriental design. Assuming the role of a dry-goods merchant or a museum guide, Tori attempts to seduce Edith with priceless objets d'art during a private tour of

the back region or "Shoji Room." According to a report in Motion Picture News , this set was filled with "novelties," including a bronze Buddha and "mysterious panels" borrowed from wealthy Japanese in Los Angeles and San Francisco.[52] As detailed in the script:

This room is the typically Japanese room—In it are Shoji Doors—The Shrine of Buddha—A cabinet where Tori keeps his treasures—A gold screen against which stands silhouetted sharp as an etching, a tall black vase full of cherry blossoms—Near the screen stands the treasure cabinet—and a brazier of coals with small branding iron which has Tori's seal on the end—This brazier has a cover to it—On a table are several artistic curios—Over a seat is thrown a woman's gorgeous kimono—plainly a treasure of great worth—etc.[53]

As Tori opens a sliding door and extends his arms in welcome, Edith enters the room, lit in very low-key lighting, and advances to the foreground where she becomes a showpiece by posing self-consciously like a manikin draped with an exquisite kimono. She refuses, however, to accept the costly garment as a gift in what is obviously a ritual of seduction. As opposed to the ballroom scene tinted in blue, the shots in the Shoji Room are tinted amber to lend the objects a more lustrous glow. Consistent with the architecture of the house which features sliding shoji screens, the couple's movement is lateral as they occupy a series of contiguous but fragmented spaces. As Tori gestures left, they exit the frame and retreat further into the interior of the room. A cut to a medium shot shows them standing before Tori's desk laden with exotic objects. Edith is captivated by the bibelots on display, but when her curiosity about the branding tool elicits an explanation—"That means it belongs to me"—she is palpably uncomfortable and shrinks back. A cut to a longer shot of the same scene effects a change in scale that creates depth as Edith moves to the rear of the room to continue her excursion. A folding screen in the background stands beneath a vase containing a large branch of cherry blossoms whose petals rain down on her.

As if to break the spell of enchantment to anticipate a disastrous turn of events, DeMille suddenly cuts to an extreme long shot of the couple photographed from a slightly oblique high angle that is unsettling. A succession of medium shots are then intercut to show events as they occur in the front region of the ballroom and in the back region of the Shoji Room. Jones, whom Edith has entrusted with the Red Cross funds, is searching for her among the ballroom guests. A cut back to the Shoji Room shows Tori flicking on a light switch to give Edith a better view of the Buddha seated before an incense burner releasing puffs of smoke into the air. Suddenly, Jones intrudes on this backstage tour with devastating news that the charity funds have been lost. Stunned, Edith faints in front of the statue of the Buddha. Switching off a series of lights, Tori renders the interior completely dark as the film is now tinted in blue instead of amber. A cut to a blank screen, the

22. Agreeing to "pay the price" in The Cheat (1915), Fannie Ward accepts a

ten thousand dollar check from Japanese art collector Sessue Hayakawa

to avoid a ruinous disclosure. (Photo courtesy George Eastman House)

left half of which is part of the shoji panel, represents an adjacent space outdoors. Gradually, Tori enters the frame as he carries the socialite's body and steals a kiss before she revives. While Edith confides her dilemma to him, suddenly a light in the interior projects the shadows of Richard and Jones, who are conversing inside, against the shoji screen on the left. A reverse angle shot shows the two men on the opposite side of the screen. Richard informs his friend, "I wish I could help you—but I couldn't raise a dollar tonight to save my life." Fearful of disclosure, signified by garish newspaper headlines that appear on the darkened screen to her right, Edith agrees to "pay the price" in exchange for ten thousand dollars. DeMille makes brilliant use of lighting effects, color tinting, set design, and variations in scale and angle of shots to dramatize a ritual of seduction symbolizing the moral contradictions of a consumer culture.

The Shoji Room, at first an exotic spectacle, continues to be the scene of disastrous transactions. As opposed to coded social rituals in genteel drawing rooms, the back region remains a site where financial deals, violent

emotions, and sexual desire are undisguised. After learning that her husband's stock investments have yielded a fortune, Edith attempts to renege on her deal by offering Tori a ten thousand dollar check. When he insists, "You cannot buy me off," a violent struggle ensues during which Edith brandishes a samurai sword. Tori brutally seizes her and brands her on the left shoulder with the mark of his possessions. The enraged socialite retaliates by grasping a gun and inflicting a similar wound on her assailant. A startling correspondence between these two antagonists divided by race and gender underscores the film's representation of modern consumption as a form of Orientalism or Western hegemony. Albeit the villain, Tori, like Edith, is a victim whose desire is thwarted by the arousal of desire in others in an unending cycle of exchange. Aside from the symmetry of their wounding each other on the left shoulder, the two characters are shown in matching high angle shots that show the diagonal of their fallen bodies intersecting with the line of the tatami mat. When Richard arrives on the scene moments after Edith's departure, he bursts through the shoji screen with explosive force to find Tori clutching a piece of chiffon torn from a gown. Unquestionably, this violation is a counterpart of the rape that has just occurred and is perpetrated, not coincidentally, against the Japanese merchant by an enraged husband. Attempting to shield his wife from her crime, Richard too engages in duplicity as he assumes blame for the shooting and is imprisoned. When Edith visits him in jail, DeMille projects the shadows of the characters and the vertical bars of the cell onto the rear wall in a succession of riveting shots. As in the scenes in the Shoji Room, the positioning of the figures in terms of light and dark areas of the frame signifies emotional states corresponding to ethical dilemmas. Paralleling this melodrama, it should be noted, were equally histrionic events that blurred the line between reality and representation. Jack Dean and Fannie Ward were married after a lawsuit in which Dean's first wife accused Ward, then a widow, of alienation of affection.

Within the historical context of urban immigration and resurgent nativism in the early twentieth century, what does the dramatic courtroom conclusion of The Cheat signify? Specifically, what message is being conveyed in the form of Orientalism as a Western discourse regarding American relations with an emergent Japan? Although Americans responded enthusiastically to Japanese exhibits of precious objets d'art at world's fair pavilions in Philadelphia, New Orleans, Chicago, and Saint Louis, their fascination was a sign of profound ambivalence. As Neil Harris argues, Americans projected their own equivocal response to modernization, industrialism, and immigration onto Japan, a nation whose artwork was still the product of exquisite craftsmanship even as its government began to Westernize.[54] Given anti-Asian sentiment on the West Coast, where the Chinese had long been brutally oppressed, admiration for Japanese artifacts

did not translate into a welcome for new immigrants. A negotiated Gentlemen's Agreement with Japan, therefore, restricted further entry, of Japanese laborers, and state legislators barred Japanese immigrants from land ownership and citizenship.[55]

The tense courtroom drama that concludes The Cheat is highly charged with the politics of nativism and racism characteristic of the era. At the beginning of the proceedings, the camera pans across the jury box to show twelve white men in three-piece suits as representatives of the status quo. As the trial progresses, DeMille uses a number of masked medium close-ups of the principals to reveal their emotional reaction to crucial testimony. During a sensational moment following the announcement of a guilty verdict, Edith proclaims her guilt and disrobes to reveal the scar that vindicates her actions. The sympathetic courtroom crowd, which has become all male in the final shots, erupts in anger and surges forward in a scene recalling a lynch mob. In fact, the script characterizes the situation as a "riot" in which the audience shouts, "Lynch him! Lynch him!" (referring to Tori) and urges men to "right the wrong of the white woman."[56] As noted in Moving Picture World , "the wrath of the audience bursts forth with elemental fury and there ensues a scene that for tenseness and excitement has never been matched on stage or screen." Equally impressed, the New York Dramatic Mirror described the courtroom scene as "one of the most realistic mob scenes that has ever been produced upon the screen."[57]

Since DeMille himself pencilled on the script the clichéd intertitle, "East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet," the message of the film about race relations is clear. In sum, The Cheat is a statement about the impossibility of assimilating "colored" peoples, no matter how civilized their veneer, and warns against the horrors of miscegenation. When the courtroom crowd attempts to attack Tori, it recalls lynch mobs that murdered blacks with impunity in a segregationist era of Jim Crow laws. Within the context of early-twentieth-century demographics, protest against Asians and African Americans also represented paranoia about the new immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. At the time, Congressman Oscar Underwood called for a literacy test to restrict immigration by claiming that the nation's purity was being threatened by the mixture of Asiatic and African blood coursing in the veins of southern Europeans.[58]

Although nativism and racism are obviously linked in The Cheat as a response to the new immigration, the relationship of these political developments to the "new woman" as a consumer is more complex. As homologous threats to the social formation, women and racial groups may be substituted for each other in considerations of the-body politic. A lurid aspect of Orientalism as a Western discourse, moreover, is the characterization of the East as effeminate and subject to colonial rape. A sign of their correspondence, Edith and Tori wear similar costumes in the film's early

sequences. During an outing, for example, the socialite appears in a striped coat lined with fabric in a bold, checkered pattern, while Tori wears a striped shirt and dons a plaid cap. Yet Edith is rehabilitated as a repentant wife through objectification of her body as a courtroom spectacle, a strategy that reinforces sexual difference to offset the diminution of separate spheres in Victorian culture.[59] Consumer behavior as a sign of modernity, in other words, is recuperated by sentimental values. Such a narrative strategy displaces anxiety about the "new woman," which was considerable, onto the racial "Other." Nevertheless, women's extravagant behavior was stereotyped as childish, if not deceitful. According to the script, when Richard reprimands Edith for a bill totalling $1,450 worth of gowns and negligees, he "indicates some displeasure, but his attitude is that of one talking to a spoiled child—not angry."[60] Yet women's inability to resist merchants and advertisers who lured them to department stores, labeled an "Adamless Eden," surely provoked disquieting thoughts about the nature of female sexuality.[61] Discourse on kleptomania as a function of the womb was, therefore, a symptom of larger concerns regarding the viability of traditional definitions of gender. Attempts to regulate sexual behavior and the body, including the medical categorization of women as kleptomaniacs, were part of tactics to impose order on a pluralistic urban environment. As women's historians demonstrate, such policing attempts intensified during periods of rapid social change and upheaval.[62]

If Edith's questionable behavior is interpreted as a woman's response to her ambiguous role in a consumer culture, what, then, may be said about Tori as a Japanese merchant and art collector? According to Grant McCracken, "the cultural meaning carried by consumer goods is enormously more various and complex than the Veblenian attention to status was capable of recognizing." Commodities do not necessarily constitute the locus of irrational and ungovernable desires, nor are they merely objects acquired during lapses of ethical judgment.[63] Granted, this may be the case today, but a discussion of Progressive Era consumption that does not account for the legacy of sentimentalism and evangelical Protestantism is an exercise in decontextualization. Yet McCracken's observations are useful in decoding the actions of the Japanese merchant as a hieroglyph that requires an investigation of meaning invested in objects. Genteel familiarity with world's fair exhibits as an intertext in middle-class culture accounts for the characterization of Tori as an art dealer. Since his enormous wealth renders consumption meaningless, Tori is no longer a consumer but a collector of rare objets d'art ritualistically branded with the mark of his possession.[64] Although department stores, museums, and world's fairs were interchangeable in terms of architectural design and displays meant to spur consumption, these institutions also served as social agencies with a mission to educate public taste. According to this logic, the Japanese merchant has

learned his lesson well and seeks assimilation in American society. For him, Edith is not simply prized as a beautiful woman who represents a tabooed relationship; as the ultimate bibelot, she symbolizes his acceptance as an art collector in an elite society that marks him as alien.[65] Anticipating their rendezvous, Tori is even more sumptuously arrayed than the fashionable socialite. Consequently, when Edith reneges on her bargain, he possesses her by force in accordance with an established ritual signifying ownership. When she later changes her mind and offers herself willingly so that charges against her husband will be dropped, Tori replies impassively, "You cannot cheat me twice." Edith is labeled "The Cheat" because she has denied the Japanese merchant assimilation into privileged white society.

Unquestionably, the enthusiastic reception accorded The Cheat was in large measure due to Hayakawa's riveting screen presence. Film critics unanimously singled out his subtle acting style, described as "the repressive, natural kind, devoid of gesticulation and heroics," because it not only contrasted with the melodramatic stage posturing of Fannie Ward and Jack Dean but rendered the villain a complex character. As Hayakawa stated in a fan magazine interview, "If I want to show on the screen that I hate a man, I do not shake my fists at him. I think down in my heart how I hate him and try not to move a muscle of my face. . . . The audience . . . gets the story with finer shades of meaning than words could possibly tell them." The Japanese actor in effect triumphed over the racist characterization of Tori in a script that stereotyped him as bowing with "oriental deference," having "a slow Oriental smile" or an "enigmatic smile," registering "sinister satisfaction," and crouching like an animal with "eyes narrowing" and "nostrils breathing hard."[66]

Catapulted into stardom, Hayakawa became one of the most important male stars on Famous Players-Lasky's roster and preceded Rudolph Valentino as an exotic matinee idol for female filmgoers.[67] Predictably, his screen persona remained charged by the fiendish role he played in The Cheat , a part that aroused protest in Japan and in Japanese-American communities. Publicity stories emphasized his bellicose nature and gave detailed descriptions of the ritual of hara-kiri. Photo-Play Journal informed readers, "You can 'take it from us,' this popular Japanese artist can scrap. His efficiency in the art of belligerency may be due to his fondness for it. In fact, he'd rather fight than eat any day. . . . Sessue is a formidable rival either at boxing or jui-jitsu [sic ]." Motion Picture Classic claimed, "in his customs and manners and conversation he is American to the finger-tips, but one always feels . . . there is the soul of some stern old Samurai."[68] Ultimately, the Japanese were unassimilable, not least because Japan's rise to global power was perceived as a threat to the United States in violation of Orientalism as a hegemonic discourse.[69]

Since canon formation is a political enterprise, an inquiry into reasons for recognition of The Cheat , as opposed to other titles in DeMille's filmography, further illuminates the issue of the new immigration in relation to the "new woman." Aesthetic considerations with respect to visual style, such as low-key lighting with dramatic use of shadows or mise-en-scène including a high ratio of medium shots, were obviously significant in the film's reception at a time when the industry sought cultural legitimacy.[70] Critics singled out the film's sensational lighting. According to Moving Picture World , "the lighting effects . . . are beyond all praise in their art, their daring and their originality." A reviewer for Motion Picture News claimed that "the picture should mark a new era in lighting as applied to screen productions." Sociological issues, however, were hardly negligible in the film's reception and elevation to canon status. The Photoplay critic focused on The Cheat as "a melodrama . . . full of incisive character touches, racial truths and dazzling contrasts"; he rightly predicted that the story was so novel it would appear before footlights.[71] Charting a reversal of the usual trajectory, The Cheat was adapted for the legitimate stage in the United States and as an opera in France (where it was retitled Forfaiture ). Paramount remade the film twice, and a French filmmaker shot a European version as an homage that also starred Hayakawa.[72] Without minimizing DeMille's superb achievement, the enormous success of The Cheat must be understood within the context of an era of rapid urban change that provoked discourse on the "new woman" and the new immigration as ideologically charged subjects.

As a footnote, it should be observed that the acclaim accorded The Cheat may well have profited from hindsight. William deMille stated in his account of the early silent film era that The Cheat became "the talk of the year." Yet an examination of trade journal literature shows that Carmen (1915) received far greater publicity as a result of the screen debut of Metropolitan Opera soprano Geraldine Farrar. Samuel Goldwyn recalled in his autobiography that The Cheat catapulted DeMille "to the front" rank of film directors and "was a first real knockout after a number of moderate successes." Again, trade journal literature and DeMille's financial statements indicate otherwise. But The Cheat did earn foreign receipts that were considerably higher than those posted for DeMille's earlier features, an indication that overseas reception of the film was quite exceptional. At the time of its release, Jesse L. Lasky did claim that The Cheat had "equalled if not surpassed" Carmen and rated the film as "the very best photoplay" his company had produced. Indeed, he had written to Goldwyn, "At last we have a picture with a wonderful, absorbing love story, with plenty of drama, and original in theme. Cecil has surpassed all his other efforts as the direction is absolutely perfect." Possibly, William deMille and Goldwyn were influenced in their recollections by French critics like Louis Delluc whose

response to The Cheat was nothing short of adulation comparable to reception later accorded Battleship Potemkin (1925). Astonished by DeMille's brilliant achievement, French intellectuals began to consider film as a serious art form. And as a further sign of bourgeois respectability, The Cheat drew crowds for ten months at a theater on the fashionable Boulevard des Italiens.[73]