5—

The Problem of Tribal Education

The vulnerability of tribal populations to exploitation by minor government officials, as well as moneylenders, landlords, and other agents of vested interests, can largely be traced to their illiteracy and general ignorance of the world outside the narrow confines of their traditional environment. Their inability to cope with the many novel forces impinging nowadays on tribal villages and on an economy which had remained virtually unchanged for centuries is by no means due to any innate lack of intelligence. As long as they operate within their familiar atmosphere, tribals evince as much perspicacity, skill, and even true wisdom as any other population, but as soon as they are faced by social attitudes rooted in a different system they become insecure and often behave in a manner detrimental to their own interests. Brought up in a system in which all communications are by word of mouth, and hence used to trusting verbal statements, they get confused by constant reference to documents and written rules, which increasingly determine all aspects of rural life. Unable to read even the receipt given by an official and obliged to put their thumb impressions on documents which they cannot understand, they are easy victims of any fraud or misrepresentation which more educated exploiters are likely to devise.

It is obvious, therefore, that a modicum of literacy is indispensable as a first step towards enabling tribals to operate within the orbit of the advanced communities dominating the economic and political scene. The disadvantages under which illiterate tribals labour are multiplied in the case of those who do not even speak and understand the

language of the dominant population, and hence cannot communicate with officials except through better-educated fellow tribesmen acting as interpreters.

Many of the tribal groups of Andhra Pradesh long ago lost their own language and speak Telugu as their mother tongue. In their case there is no language barrier, and hence no need for any special type of schooling. Other tribes, however, speak languages unintelligible to most outsiders, and it is imperative for them to learn Telugu if they want to communicate with members of the majority community. This is the case of the Gonds and Kolams of Adilabad, of some groups of Koyas of Khammam, and of several of the tribes of Vishakapatnam and Srikakulam.

Among the Gonds there are still many who speak no other language than Gondi, a Dravidian tongue closer to Kanara than to Telugu, and many Kolams speak Kolami and Gondi, but neither Telugu nor any other language understood by officials and members of the advanced ethnic groups. Hence they are handicapped at every step as soon as they move out of the small circle of their fellow tribesmen.

Education for tribals who normally speak their own tongues is beset with difficulties, because the acquisition of literacy has to be combined with the learning of a language other than the mother tongue. Yet the average teacher available for tribal schools has had no training whatsoever in the technique of imparting to children what is to them a foreign language.

The first major educational experiment launched among any tribal community of Andhra Pradesh was the Gond Education Scheme in Adilabad District, initiated by the Nizam's government in 1943. At the time, when there was a determined drive to improve the position of the Gonds, Pardhans, and Kolams, it was realized that no advance could be maintained unless it was accompanied by the emergence of at least a small number of literate tribals. But what was to be the medium of instruction? The vast majority of Gond children did not speak or understand any language other than Gondi, but there were no teachers who knew Gondi and could communicate with Gond children. Hence there was no other solution to the problem than to produce Gondi-speaking teachers before any schools for Gond children could be established. There existed at that time a few young Gonds who had privately learned the rudiments of reading and writing Marathi, the language spoken by many of the Hindus of the western part of the district. A small band of such semi-literate Gonds were assembled at Marlavai, a village in the hills of Utnur Taluk, and initially given systematic training in the reading and writing of Marathi and in arithmetic.

It was hoped that this training centre established in Marlavai would

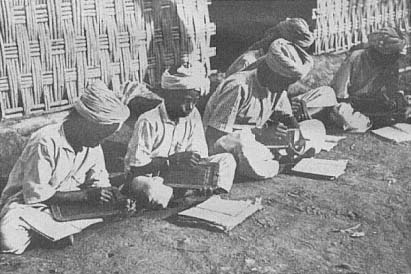

Gond boys practising writing on slates in front of the school building of

Marlavai village.

produce enough Gondi-speaking teachers to make it possible to start within a few years a network of primary Gond schools extending over the greater part of the district. The medium of instruction in the first two classes of these schools was to be Gondi, and to provide teaching materials the headmaster of the Marlavai Training Centre and I composed Gondi primers and readers printed in Devanagari script. The idea was that once the children had learned to read and write Gondi in this script, they could more easily be taught Marathi, the script being the same. From the fourth standard onwards Urdu, then the official language of Hyderabad State, was to be added, and in order to make this possible the teacher trainees were also taught Urdu.

By 1946 thirty primary Gond schools were functioning, and by 1949 their number had more than trebled. In order to improve gradually the standard of the Gond teachers, all of them were annually assembled at Marlavai for a course of instruction lasting one month. In this way the level of their competence was raised, and they were familiarized with new developments in the sphere of tribal welfare. In addition to the training of teachers, the Marlavai centre was used for the instruction of literate Gonds in the basic knowledge of revenue matters required for village officers, and some of those trained were subsequently appointed as patwari .

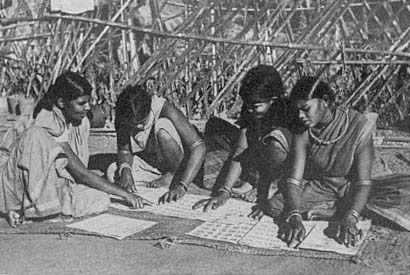

Girls of Marlavai being taught to read Gondi with the help of a chart prepared

in 1943 for the instruction of adults.

By 1951 the Marlavai Training Centre, which in 1943 had begun with the training of five semi-literate Gonds, had produced ninety-five teachers, five village officers, one revenue inspector, five clerks, and seven forest guards. One of the trainees of Marlavai, Atram Lingu, subsequently became patwari, sarpanch of the Sirpur panchayat , and finally in 1967 president of the Panchayat Samithi of the Utnur Tribal Development Block.

The success of this centre encouraged the Social Service Department to establish a second centre at Ginnedhari, a Gond village in Asifabad Taluk. There Telugu was the language of the non-tribal population, and hence Telugu was taught instead of Marathi.

The high hopes which had been placed in this experiment of imparting education to Gond children in the mother tongue and at the same time familiarizing them with the regional languages were subsequently disappointed. The incorporation of the Telengana districts of Hyderabad State into Andhra Pradesh was accompanied by fundamental changes in the educational system. The government decided to abandon the use of Gondi, and no further schoolbooks in Gondi were supplied to the schools. Instruction in Telugu, now the state language, replaced teaching in both Marathi and Urdu, with the result that

many of the Gond teachers became redundant because they could not teach in Telugu.

Yet the young Gonds who had attended the two training centres formed for years a class of moderately educated tribals. Apart from those who worked as teachers, there were some who found employment in minor government posts.

In 1972 the character of tribal schools was changed. Many single-teacher schools were closed and staff and children grouped together in so-called ashram schools. These provide boarding facilities for children from other villages, while children from the same locality can attend as day scholars. The expense of these boarding schools is considerable, for to maintain and educate a child in one of them costs the government approximately Rs 1,000 per year. There is no coordinated control over the tribal schools, as some are supported by the Tribal Welfare Department and others by the relevant Panchayat Samithi. In 1975 there were 269 primary schools, 46 ashram schools, and 10 Tribal Welfare hostels for children attending upper primary schools and high schools outside the area covered by the Integrated Tribal Development Project. The government also provided scholarships, books, slates, and clothes to tribal pupils. Despite all these facilities only 31.2 percent of the tribal children of school age were enrolled in educational institutions, and the literacy rate of the tribals of Adilabad District, which had been 2.52 percent in 1961, had risen to no more than 3.28 percent. According to the 1971 census there were then many villages the entire population of which was illiterate, and I learned by personal observation that even in 1979 there were still entirely illiterate village communities.

The numbers of the various types of educational institutions in all the tribal areas of Andhra Pradesh in 1979 were as follows:

|

The number of teachers in ashram schools was 1,171 and that of teachers in other schools 1,821. Despite the existence of all these schools, the percentage of tribal children who pass the tenth standard, i.e. matriculation, and are thus qualified to proceed to intermediate courses in colleges is very low, and in thirty-six years of tribal education only five Gonds and two Pardhans have been awarded university degrees.

What is the reason for this disappointing lack of educational prog-

ress, which contrasts so dramatically with the rapid advances achieved by most tribal communities in Northeast India (see chapter 11)?

One of the causes is undoubtedly the very low standard of teaching and facilities in tribal schools. About 75 percent of all schools are housed in thatched huts, many of which leak during the rains, a defect making their proper functioning extremely difficult. There are, moreover, no quarters for the teaching staff, and rented accommodation is unavailable in most tribal villages. The lack of basic comforts discourages non-tribal teachers from taking on jobs involving residence in remote villages, and among those posted in such villages there is a high rate of absenteeism. While non-tribal teachers are reluctant to work in tribal villages, few Gonds are nowadays available for such posts. The reason is that the Education Department has raised the required standard, so that only persons who have attained intermediate standard are eligible for teaching posts. Gonds who have reached that standard are few; those who have done so can continue their education with the help of scholarships, and if they are successful they have a good chance of obtaining more attractive posts owing to the system of reservation of posts for members of scheduled tribes. Hence, qualified tribals are not very interested in appointments as teachers, and those tribal matriculates who would be glad to take up such posts are not acceptable to the education authorities.

Among the teachers working in tribal schools at present, those of non-tribal origin generally have higher educational qualifications than their tribal colleagues. Nevertheless, their efficiency as teachers is not necessarily higher than that of tribal teachers. Their appointment to schools in a tribal area is usually purely accidental. Few of them have expressed any preference for such a posting, and they are given no orientation or training for work among tribal children. Their difficulties begin with their inability to speak and understand Gondi, the only language most of the younger children know. Moreover, they are total strangers to tribal culture and the values of the society within which they have to operate. Those who persevere in tribal schools usually pick up a working knowledge of Gondi, but their own cultural background stands in the way of an understanding and appreciation of tribal culture and traditions. As quarters are not provided by government and rented accommodation is usually unobtainable, most non-tribal teachers are separated from their wives and children, with the inevitable result that they take every opportunity of leaving their posts and visiting their families. The majority of these teachers try to obtain posts outside the tribal area as soon as possible.

As a result of the shortage of efficient teachers, as well as of the inadequate facilities in most schools, few tribal boys and girls pass the

tenth standard, and the majority of those enrolled drop out long before. The reasons for this wastage are many. At the age of ten to twelve, boys and girls are useful for work on their parents' farms, and many Gonds are unwilling to spare their children, particularly if they see that the schools are not well run and the teachers' frequent absences condemn the children on many days to virtual idleness. Perhaps more important is the realization among parents, as well as the older pupils, that school education is of limited usefulness. While those who have passed the tenth standard are eligible for minor jobs in government service, by no means all have obtained such jobs, and there is, moreover, the large category popularly described as "tenth failed." Boys who have read up to the tenth standard but failed to pass the final examination have few chances of employment in government service, and as nearly all commercial activities down to small village shops are in the hands of non-tribals who employ on principle only members of their own caste or community, there are no other openings for such youths. Yet ten or more years at school have given them the ambition to find an occupation other than the ordinary farm work for which they are no better qualified than their illiterate contemporaries.

In the tribal societies of Northeast India, superior educational institutions allow many young people to obtain good academic qualifications which enable them to compete even outside their own sphere on equal terms with men and women of other communities. There many tribals have been appointed to gazetted government posts, and others have proved successful in the professions and in commerce. Hence education has so high a prestige that a few failures do not marr its image. But the Gonds see hardly any of their fellow tribesmen elevated to respected and lucrative positions, and numerous school-leavers are without any jobs. Their disillusionment with school education is therefore understandable. The advantage of having some literate persons in the village does not weigh heavily with the individual family which for years has forgone a son's help on the farm without enjoying any financial reward for the time he spent at school.

A certain disenchantment with the results of school education prevailing among many of the illiterate tribals accounts for the fact that in villages where tribals and non-tribals live side by side the latter are much keener on making use of educational facilities. In an investigation conducted in 1977 by Y. B. Abbasayulu in nine villages of Utnur Taluk, it was found that 62.28 percent of the non-tribals, but only 33.72 percent of the tribals, sent their children to school. Of the tribals interviewed, 22.15 percent gave poverty as their reason for not sending their children to school, 12.5 percent claimed the children's involvement in agricultural activities, and 3.75 percent gave as an excuse their

general inferiority complex vis-à-vis non-tribals. Some of the non-tribals also claimed poverty as an excuse, but none invoked the need for children to do farm work, and reference to a feeling of inferiority did not figure in their replies. Interestingly, more tribals than non-tribals replied positively to the question of whether they thought of education as good and valuable; 98.46 percent approved of school education, whereas only 76.3 percent of the non-tribals professed so positive an appreciation. Abbasayulu interprets this surprising result of his inquiry by pointing out that non-tribals, engaged mainly in making money, were confident of their ability to be economically successful even without formal education, whereas tribals realized that their depressed status could be bettered only by education, despite the disappointing results of the schooling of so many of their children.

As an illustration of the impact of education on individual villages, we may consider the situation in Marlavai and Kanchanpalli. The former was the first centre of Gond education and is still the site of an ashram school, and the latter also has some tradition of literacy as the seat of a raja family literate for at least three generations. At Kanchanpalli, too, there is at present an ashram school.

Among the fifty households of Marlavai, there were in 1977 eleven literate adults and fourteen children attending the local school. Apart from one retired school-teacher, no one in the village had ever held a paid post.

Among the sixty-four households of Kanchanpalli, there were in 1977 twenty-two literate adults and twenty-four children were attending the local school.

In both villages there were among the literate adults men who had attended school for only three or four years, and had only a very limited knowledge of reading and writing.

By the beginning of 1980, the educational scene in both villages had considerably improved, probably because of the Gonds' general increased awareness of the need for education. Forty children of Marlavai were attending various schools. Twenty-one of these went as day pupils to the local ashram school, 15 were boarders in other ashram schools, and 4 attended schools in two taluk headquarters and stayed there in hostels for scheduled tribes where they got free food and lodging. In the Marlavai ashram school there were then 139 pupils, including 21 girls. Attendance in the Kanchanpalli ashram school had also increased: there were altogether 89 pupils, including 50 boarders and 39 day pupils.

There can be no doubt, however, that part of the money and effort devoted to the teaching of tribal children is wasted because many children leave school after the third or fourth year and soon relapse into virtual illiteracy. This is borne out by the relatively small number of

literates in Marlavai. This village has had a primary school since 1945, and in 1943–44 it was the focal point of an adult literacy project for which special charts in Gondi had been printed. Yet thirty-four years later there were only eleven literate adults among the villagers.

In a study of tribal education in Adilabad District, E. V. Rathnaiah investigated the attitude of Gonds to school education.[1] In the course of this investigation he found that in the opinion of the teachers interviewed 13.7 percent of parents were positively cooperative, 56.3 percent were favourable to education but not active, 23.7 percent were indifferent, 1.3 percent were unfavourable, and 5 percent were antagonistic. The reasons given by parents for not sending their children to school were as follows:

|

In the opinion of the teachers questioned, the reasons for the poor enrollment of tribals in schools were:

|

Even more important factors impeding the spread of education among tribal children are the distance of many villages from the nearest school and the limited places in ashram schools. There are many villages whose children would have to walk five or six kilometers to attend a school, and there are not enough boarding schools to accommodate more than a fraction of the children from villages without primary schools in a vicinity.

For tribal children who are eligible for admission to upper primary and high schools, most of which are situated at some distance from tribal villages, there are hostels in which pupils are provided with free board and lodging, and in some cases also with extra tuition. Without such facilities few tribal children could attend high schools, because for most parents it is economically impossible to maintain a child in a taluk or district headquarters.

Notwithstanding all the material facilities provided by government for tribal students, few progress beyond the fifth from. The following figures relating to 1976 make this clear. Of 5,599 tribal children enrolled in the schools of Adilabad District, 4,555 were boys and 1,044

[1] Structural Constraints in Tribal Education.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

were girls. Distribution in forms I to X was as follows: I, 3,302; II, 832; III, 363; IV, 298; V, 345; VI, 194; VII, 119; VIII, 58; IX, 43; X, 40.

The rapid drop in attendance was particularly noticeable in the blocks of Wankdi and Utnur.

There the relevant figures were as follows:

|

For the years after 1976, statistics for the indigenous aboriginals are not available because in 1977 the immigrant Banjaras were notified as a scheduled tribe, and henceforth counted among the tribals. But my personal enquiries in primary, upper primary, and high schools confirmed the trend apparent in the above statistics. After the first form, in which many children are enrolled, there is a dramatic drop, and between forms II and III, and III and IV, the figures are each year more than halved. Only a very small percentage of pupils reaches forms VIII, IX, and X. Of those reading in form X, many fail the Secondary School Certificate examination, and the number of Gond children attaining eligibility for college education is thus infinitesimal; this explains the disconcertingly small number of graduates. In the school year 1976–77, 797 boys and 109 girls were attending high schools in Adilabad District, but only one boy attended a junior college.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There is no shortage of scholarships for those eligible for higher education, and this may be seen from Table 1.

In the Government Degree College, Adilabad, the enrollment in the first-year intermediate course from 1969–70 to 1975–76 was twenty-five, out of which only six students completed their courses. The high degree of wastage was probably due to the students' inadequate previous education, which did not enable them to compete with non-tribal students in a course demanding not only learning by rote but also independent judgement.

The standard of educational performance by tribals, i.e. Gonds, Pardhans, and Naikpods, is reflected in the qualifications of those who succeeded in obtaining employment in government service up to 1977. The fact that no Kolam figures in this list indicates the exceptionally low educational level of that tribe.

The columns of Table 2, from which individual names are deliberately omitted, contain information on the tribe, the type of employment, the educational qualification, and the home village of the tribal employees in 1977.

This list of tribal government employees illustrates both the successes and failures of tribal education in Adilabad District. Among the successes must be considered the fact that thirty-seven tribals received an education which enabled them to enter the ranks of government service at all. Seventeen of them acquired sufficient skills to enable

them to attain and hold positions as lower division clerks in a variety of offices. Their qualifications range from secondary school certificate to B.A., but a number of them failed either in the intermediate or in the degree examinations and had to content themselves with minor clerical positions though success in their examinations might have made them eligible for gazetted posts. Thus one Gond graduate has recently attained the elevated position of district revenue officer. The number of those who failed in the examinations for which they had studied is relatively large, but even they managed to obtain such minor government posts as market inspector, salesman, or vaccinator. But there must be many more who failed to attain the secondary school certificate and who did not manage to secure even the humblest of government posts.

A further fact emerging from this list is the disproportionately large representation of Pardhans among government employees. They outnumber Gonds, even though the total Pardhan population is less than 10 percent of the number of Gonds. As traditional bards and chroniclers they were always the "intellectuals" among the local tribesmen, and it is hardly surprising that they could overtake the Gonds in the competition for jobs which require some intellectual gifts.

The list further reveals the advantages enjoyed by tribals in the more progressive areas, such as Adilabad Taluk, and the more backward status of the tribal population of Utnur Taluk. Proximity to district headquarters seems to have had a positive influence both on education and on the people's awareness of the opportunities for entering government service.

A study of tribal manpower resources in Adilabad District undertaken in 1977 by the Tribal Cultural Research and Training Institute, Hyderabad, has diagnosed some of the factors which impede the recruitment of young tribals to government service and private industry. Both in government enterprises and in industry there are numerous vacancies for posts requiring technical skills, but the number of tribal candidates with such qualifications are few. There is an Industrial Training Institute in Mancherial, entry into which is open to candidates with a pass in the eight standard. In the year 1973-74 one tribal joined one of the courses but dropped out, and in the years 1971–72, 1972–73, and 1974–75 there were no tribal students. In the year 1975–76 six tribal candidates joined this institute; three in the course for fitter's trade and three for tractor mechanic's trade. In 1976–77 three candidates joined the course in mechanic's trade, and in 1977 altogether six tribal students were enrolled in the institute. This is a very small number considering the fact that the Singareni Collieries Company Limited alone has an annual requirement of three thousand candidates to fill vacancies in all grades and has to import labour from

other districts because of the lack of sufficient qualified local persons. In 1977 there were seventeen vacancies for holders of certificates of the Industrial Training Institute on the register of the employment exchange, but there were only two tribal candidates.

As early as 1946 I advocated in my pamphlet Progress and Problems of Aboriginal Rehabilitation in Adilabad District the systematic training of Gonds and other tribals in mechanical skills. I wrote:

I believe that Gonds could be trained as skilled workmen, and I would suggest that the training of young literate Gonds as carpenters, mechanics, fitters etc. should not be deferred until the industries of the new towns have come into being, but should be taken up at once. If we can build up a small stock of trained Gond workmen of fairly high qualifications . . . these young men can become the nucleus and leaders of an industrial Gond colony and serve as an example that for the aboriginal industrial employment does not necessarily mean casual labour at low wages and life in an uncongenial, squalid environment, but that an industrial worker can enjoy as high or higher a standard of living and as good housing as an independent cultivator. (P. 54)

Had this proposal been taken up, the involvement of tribals in the industries of Bellampalli and Mancherial might have begun when these industries were still in an early stage of gradual development and hence capable of integrating small groups of tribal workers. Today Gonds can enter industry only as individuals and only at the cost of total alienation from the traditional life-style of tribal society.

In the course of the study of manpower resources quoted above, tribals in various boys' hostels were questioned about their career preferences. The results of the interviews showed that 40.9 percent wanted to become teachers in arts subjects; 22.7 percent wanted to become science teachers; 18.2 percent wanted to study medicine and become doctors; and 18.2 percent wanted to enroll in technical courses and become engineers. Of those interviewed, 82.8 percent hoped for employment in Adilabad District, preferably near to their home villages. An interesting feature of this enquiry is the preference for such familiar professions as teaching, medicine, and engineering, while none of those asked mentioned careers as veterinary surgeons or agricultural extension officers. More surprisingly none of the boys stated that he wanted to become a tahsildar or superior revenue officer, an interesting contrast to the aspirations of tribal students in Arunachal Pradesh, many of whom told me that they hoped to join the administrative service and to attain ultimately the position of deputy commissioner or another post involving responsibility and authority. The tribals of Adilabad have for so long been ruled by outsiders that they cannot envisage the possibility of occupying positions of authority and power, although one of them was recently appointed to the pres-

tigious position of district revenue officer.

The situation in other tribal areas is similar to that prevailing among the Gonds of Adilabad. In the 1940s teacher training centres identical to those at Marlavai and Ginnedhari were established in Koya villages of Warangal District, and in 1979 some Koya teachers trained in those institutions were still in service. Most of the Koyas have the advantage of speaking Telugu as their mother tongue, and Koya children therefore face fewer difficulties than the Gondi-speaking children of Adilabad. The absence of a language barrier accounts perhaps for the fact that among the tribals of Khammam district the literacy rate was 5 percent, compared with 3.28 percent in Adilabad District, both figures relating to the 1971 census. Another explanation may be the inclusion in Khammam District of some areas which in the days of British rule belonged to the Agency Tracts of Madras Presidency, where educational standards were more advanced than in Hyderabad State. In the area of Sudimalla, one of the Koya training centres established in 1946, several Koyas have had fairly successful careers. In 1978 there were two Koya subinspectors of police, and one Koya who had entered the central police service held the appointment of district superintendent of police at Imphal in Manipur State, a highly responsible position in a sensitive frontier region.

In recent years special efforts have been made to develop educational facilities in Srikakulam District, where the administration is anxious to regain the confidence of the many tribesmen who were involved in the Naxalite uprising (see chapter 2). Saoras, Jatapus, and various minor tribal groups number a total of 213,928 and thus constitute 8.2 percent of the population. Most of them are economically backward and, dwelling in remote hill villages, had until recently no access to any kind of schools. A further obstacle to the spread of education was the fact that such tribes as Saoras and Gadabas speak Munda languages, whereas teaching was available only in Telugu, even where schools had been opened in the vicinity of tribal settlements. By 1978 there were 227 primary schools, 5 upper primary schools, and 4 high schools, in which nearly 12,000 children were enrolled. In addition, there were 61 ashram schools, 25 of which had been opened in 1977, and altogether 6,000 tribal children were maintained as boarders in ashram schools and hostels. The annual expenditure on education was then Rs 5,000,000. Some of the results seem to have been rather better than those from Adilabad quoted above. Thus, between 1974 and 1979, 35 tribal pupils of the high school at Bhadragiri succeeded in passing the matriculation examination. Even in some Saora and Jatapu villages situated on high hills and accessible only by footpaths, ashram schools have recently been opened and seem to be well attended.

Chenchus of Kurnool were taught ploughing and supplied with bullocks; when

the bullocks died the Chenchus fashioned hand-ploughs and continue to cultivate

on a small scale. A woman walking behind the plough is dropping maize seeds.

The overall literacy rate for all the tribal areas of Andhra Pradesh was 5.34 percent in 1971, and had risen to 8.62 percent by 1978. The system of ashram schools providing boarding facilities for tribal children extends to all the districts containing tribal populations, including Mahbubnagar and Kurnool, where school education is provided even to the children of the semi-nomadic Chenchus.

It appears that the low economic level of the foodgathering Chenchus has no adverse effect on the children's ability to absorb the instruction provided in schools, and in the ashram school at Mananur some Chenchu girls are studying in the tenth standard.

In Kurnool District, where education for Chenchus was started in the British period, there are a few families of educated Chenchus who have obtained positions in government service, but in Mahbubnagar District there are as yet no adult Chenchus who have gone through the school system. It remains to be seen whether those Chenchus who have spent several years in boarding schools will be able to readjust to the forest life of their parents. If they have lost the skill of gathering marketable forest produce or have developed wants which cannot be met from the income Chenchus derive from the sale of such produce, education may be a mixed blessing except for those young people who

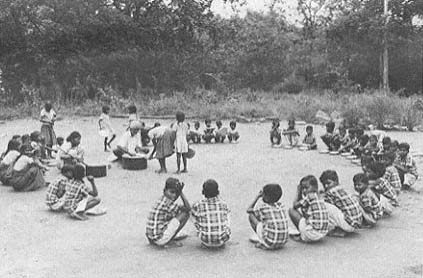

Chenchu pupils of the boarding school at Pulajelma during the midday meal.

obtain jobs outside their traditional habitat.

The educational backwardness of most of the tribal populations of Andhra Pradesh is a correlate of the generally adverse economic conditions under which the tribesmen labour, and cannot be attributed to a lack of funds available for educational institutions. In the financial year 1978–79, a total of Rs 56,340,000 was allocated for tribal education, and of this total budget Rs 52,245,000 was provided by the Tribal Welfare Department.

The number of educational institutions in 1978, together with the number of pupils within the area covered by the plans for tribal development, is shown in Table 3. The boarders accommodated in hostels were also given special coaching. The number of teachers in ashram schools was 1,171, and the number of teachers employed in primary, upper primary, and high schools was 1,821. The number of students in receipt of post-matric scholarships was 1,950, 468 tribal students were admitted to reputable private schools and public schools, and 90 students were enrolled in the special residential Kinnarsani school for tribals.

In Andhra Pradesh the funds spent on educational institutions accessible to tribal populations have not yet brought about a fundamen-

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

tal change in the tribals' unfavourable position, largely because the social, political, and economic forces arraigned against them have so far prevented all real progress. In chapter 11 we shall see, however, that in Northeast India educational progress among tribals has played an important role in securing for them a position of political equality and growing economic prosperity.