Chapter 5

Housing the Algerians: Grands Ensembles

Construction of housing responds to an urgent social need. . . . Housing is a decisive factor in social evolution: the modification of habits and familial needs that it instigates broadens the possibilities for industrialization and general development.

République Française, Délégation Générale du Gouvernement en Algérie, Plan de Constantine

In the wake of the modernist practices that had become commonplace in Europe, social housing made its debut in Algiers in the mid-1920s. Between the years 1925 and 1933, seven complexes were built for Europeans.[1] Situated on the outskirts of the city proper as independent enclaves, these early experiments were the model for future trends. From then on, housing complexes in Algiers dotted the unbuilt zones on the edges of the city and played an instrumental role in its growth pattern (Fig. 58).

Promotion of modern low-cost housing for the Algerians followed in the footsteps of the projects built for Europeans, but incorporated another set of sociocultural criteria that maintained the separation of the two communities. As discussed in the previous chapter, the first serious discussions on the urgency of promoting such housing took place as part of the attempts to renovate Algiers on the centennial of the occupation. Not only were policies and legislations developed, but also questions of lifestyle and cultural differences were addressed, incorporating debates on the form of the traditional house, the nature of the Algerian family, the role of women, and the adoption of appropriate architectural forms and styles. Owing to former practices in Lyautey's Morocco and

the experimentations with Islamic forms in the colonial pavilions of the universal expositions, the first housing schemes reflected strong "arabisance" traits.[2]

At the same time, the architects of the first phase of indigenous mass housing relied on the puristic white plasticity of modernism, also favored by the North African vernacular. Two theoretical Cité Musulmane projects from the 1930s crystallize the idealized qualities of the "traditional" Algerian vernacular, although tamed according to French rationalism. In François Bienvenu's 1933 proposal for a modern indigenous quarter in Climat de France on the heights of Bab el-Oued, the whitewashed, cubical volumes recalling the casbah are regimented by straight streets; to reinforce the casbah association, the drawing depicts veiled women in white robes crowding these streets (Fig. 59). Individual houses are interlocked with each other and each house is introverted by means of a courtyard with only one main window to the outside. In Louis Bérthy's 1939 cité , again an iron grid organizes the abstract site, creating a straightforward street network (Fig. 60). Within the grid each block is divided into individual houses with courtyards that share walls. The street facades are blank except for the entrance doors, whereas the houses open up to the courts, which display miniature havens planted with exotic plants and trees.

Only three housing projects were built for indigenous people during the 1930s. They were stylistically conscious undertakings that emphasized the cultural differences between the two communities in Algiers. This trend was gradually overshadowed by the more universal architecture of the second and third periods of massive housing construction—the second under Mayor Jacques Chevallier between 1954 and 1958, and the third corresponding to the implementation of the Plan de Constantine between 1959 and 1962. While "statistical" concerns would gain priority in the 1950s, a nod would always be given toward the sociocultural norms of Algerians, and in a few cases, architecturally intriguing solutions would attempt to reinterpret local lifestyles.

The First Phase: The 1930s

The first cité indigène by François Bienvenu was an HLM that consisted of sixty-two apartments. Located on the Boulevard de Verdun, which defines the northern boundary of the casbah, it sits on

Figure 58.

Schematic plan of Algiers showing the location of housing projects discussed in this chapter. The numbers correspond

to the order in which the projects appear in the text. (1) Boulevard de Verdun, (2) Scala, Clos Salembier, (3) Ste.-Corinne, (4)

Climat de France, (5) Boucle-Perez, (6) Diar el-Mahçoul, (7) La Montagne, (8) Dessoliers, (9) Carrière Jaubert, (10) Djenan

el-Hasan, (11) Cyclamens, (12) Nador, (13) Eucalyptus, (14) Taine E, (15) Asphodèles, (16) Mahieddine, (17) Dunes, (18) Diar es-Shems.

Figure 59.

(above) François Bienvenu, cité indigène project, Climat de France, 1933. Figure 60.

(below) Louis Bérthy, cité indigène project, 1936.

Figure 61.

Bienvenu, Boulevard de Verdun housing, view, 1935.

the ramparts of the Ottoman fortifications (Fig. 61). Its placement at the very edge of the old city and its architectural qualities—"rationalized" from the houses of the casbah—allude to its symbolic ambivalence: the Verdun housing belongs and does not belong to the casbah. The cité consists of three blocks, separated from each other by interior passageways and courts. Multiple entrances, marked with horseshoe arches, provide access to various levels, but only from the Boulevard de Verdun side; the complex cannot be reached from the casbah. The massing and the height of the blocks (which reach seven stories at their highest) form a contrast to the scale and fabric of the casbah and further accentuate the "in between" quality of the project. The complex topography of the site helps enliven the volumes and spaces; while the facades on the Boulevard de Verdun are from six to seven stories high, the back facades remain only three stories.

The architecture of the Boulevard de Verdun blocks aimed for a new urban image that combined the "traditional" with the European and a new housing type that responded to the customs of Muslim residents while giving them the amenities of modern habitation. With their clean, modernist lines, white surfaces, sparse openings, crenellated rooflines, and flat roofs, the new buildings complemented the old quarter in their picturesque appearance, but their exaggerated height on the Boulevard de Verdun acted as a clear-cut boundary. The plans were derived from

the courtyard houses of the casbah, but what was private in the latter was made public in the former: apartment units now faced the courtyard, not the rooms of the same house. A continuous hallway surrounded the courtyard and gave access to individual units. The concept remained a simple enlargement of the casbah-style house into a communal type, despite the emphasis on "conform[ity] to Muslim customs."[3]

As it was the first housing project built for Algerians in a prominent location, the Boulevard de Verdun apartment complex enjoyed great publicity. Yet it failed to serve as a model for other complexes in the 1930s, because the predominant characteristics of the "traditional" Algerian house (as studied by the French) dictated that "horizontal" housing met the needs of Algerians better than "vertical" schemes. The choice for low-rise single-family patterns called for ample space, and the subsequent low-cost projects were not built in the center of Algiers, where land was scarce and expensive.[4] The Boulevard de Verdun housing thus remained a unique experiment.

In contrast to the Boulevard de Verdun blocks, the other two schemes realized in the 1930s were horizontal developments located away from the center of Algiers and consisted of attached individual units, each with its own courtyard or small garden behind high walls. Architects Albert Seiller and Marcel Lathuillière designed the Cité Scala (also known as La Madania), on the Clos Salembier hill, near Belcourt. Covering an area of 8 hectares, this settlement was intended to house six thousand residents with diverse social origins, including "the poorest . . . families and bachelors who had just arrived from the countryside." The project was considered an excellent social and political solution to the pressing problem of hygiene, commonly attributed to old indigenous quarters of the city.[5]

Lathuillière's sketch, published in Chantiers in 1935, shows a compact settlement nestled against the hill and consisting of cubical, flat-roofed, low-rise houses with very small windows (Fig. 62). The rooflines of the houses are broken by chimneys and, on the larger scale, the domes and minarets of the religious and social centers animate the entire built fabric. A central axis divides the quarter in two and is stepped to conform to the topography. On this axis is a public square faced by a large institutional building with neo-Arabic facades and a courtyard. Lathuillière's idealized drawing borrows from the picturesque Islamic villages of the world's fairs, especially from the 1931 Colonial Exposition with its extensive Tunisian village and from Morocco's nouvelles médinas of the 1910s and 1920s. Nevertheless, it also displays a similarity to Tony Garnier's

Figure 62.

Albert Seiller and Marcel Lathuillière, housing project in Clos Salembier, initial scheme, 1935.

Figure 63.

Seiller and Lathuillière, housing project in Clos Salembier, site plan, 1936.

Cité Industrielle in the cubical white masses of the housing, the courtyards, the placement of communal facilities, and the clear hierarchy between main streets and residential ones. If the "arabizing" details were erased from the drawing, the references to Garnier's vision would be truly striking in the resulting image—not a surprising influence given Garnier's reliance on an abstract Mediterranean residential type. Garnier's socialist agenda is absent from Lathuillière's design, however, as utopia is a tricky notion when building for the colonized.

Seiller and Lathuillière's preliminary design underwent changes as the construction was executed. The built scheme followed the initial site planning principles, which adhered to the topography in creating a terraced settlement pattern (Fig. 63). The main axis with its central spine of stairs was also kept. The architects diluted the architectural vocabulary by deleting the overt neo-Islamic references and by opting for a pure and modernist vocabulary. In its final form, the overall appearance of the Clos Salembier project ends up displaying strong formal affinities to Garnier's early modernism. Yet the spatial organization of each unit recalls the rural housing types studied by ethnographers (Fig. 64). With

Figure 64.

Seiller and Lathuillière, housing project in Clos Salembier, plans of two house types, 1936.

Figure 65.

Louis Bonnefour, indigenous housing project in Maison-Carrée, plans, sections, and facades, 1932.

few exceptions, direct communication between rooms was not provided for. The attached single-story houses had prototypical U-shaped plans, with courtyards that gave access to all interior spaces. The overall plan thus recalled an extended family compound, as studied by Thérèse Rivière, for example.

The last housing project from this period is the cité indigène in Ste.-Corinne in Maison-Carrée, an industrialized suburb of Algiers. In 1933, an official document recorded two quartiers insalubres in Maison-Carrée: a "village of negros" (village nègre ) and Ste.-Corinne, both deemed "unacceptable." Several measures were taken to reorganize the quarter, in addition to building a new housing project.[6] An early scheme prepared by Louis Bonnefour, an architect practicing in Algiers, proposed a continuous framework of houses with shared side and back walls (Fig. 65). The exterior facades had minimal openings—an entrance door, a bathroom window, and a triangular ornamental window for ventilation. One pitched roof sheltered two units, back to back. Organized by an ever-extendable grid, each unit consisted of two rooms, a court with a water outlet, a separate toilet, and a sheltered area.

Figure 66.

Socard, low-rise cité indigène, view, 1951.

The rooms opened onto the courtyard, intended as the heart of the house. There was no separate kitchen or facilities for cooking, most likely justified by studies of traditional housing and women's domestic work. The fireplace in the main room could be used for cooking as well as heating the house. Because the water outlet was in the courtyard, accommodations for cooking were not coordinated, setting a precedent for future kitchen designs, which remained problematic.

A couple of years later, in 1935, architects Guérineau and Bastelica reinterpreted this scheme and increased the density by superposing another unit on top of two neighboring units while maintaining the internal organization of each unit. The cité indigène in Ste.-Corinne did not resolve the hygiene problem in Maison-Carrée outlined in the 1933 report, but it did introduce a long-lasting typology. As argued by Deluz, the minimal living spaces and the inner private courtyards with water outlets and toilets, derived from "traditional" houses and supposed to answer the needs of Algerians, were later incorporated into high-rise blocks.[7]

Another scheme to shelter two thousand Muslims in the Climat de France area to the west of the casbah also dates from 1934, although its execution had to wait until the end of World War II. By the early 1950s, two new settlements were built here: a "horizontal" development, consisting of parallel rows of two hundred single-story units, and an apartment building complex known as Boucle-Perez. The first, also referred to as Cité Climat de France, was later extended to incorporate ten thousand units. Architect Tony Socard designed the core settlement with groups of two houses whose courts shared a party wall. Constructed in a prefabricated system, they could be reproduced easily (Fig. 66). Each house had two or three rooms under a tiled, pitched roof, and there was

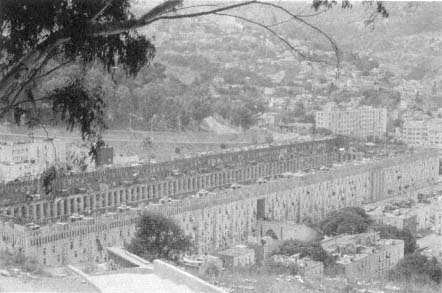

Figure 67.

Bienvenu, Boucle-Perez housing project, overall view, 1952.

a toilet in the courtyard, repeating the pattern set by the Ste.-Corinne housing and referring back to the "traditional" house.[8] The ornamental framing of the windows facing the streets was intended to secure privacy for the family. The bold expression of the geometric patterns generated by the prefabricated elements and the formal qualities of the window and ventilation frames, derived from the rural vernacular, enlivened the facades in a vocabulary familiar to the modernist architecture of Algiers—showing particularly the influence of Auguste Perret. Some communal facilities, such as a clinic and a nursery, were also projected for this neighborhood, in addition to eight shops. The site plan formed

Figure 68.

Bienvenu, Boucle-Perez housing project, plan of a unit, 1952.

a grid, with stepped streets which climbed the hill and were interrupted by platforms at individual entrances.

The Boucle-Perez housing block, designed by François Bienvenu and intended for the resettlement of the populations evacuated from the Marine Quarter, was situated on Avenue Ahsan. While it belongs to the same typology as the Boulevard de Verdun project, its relative distance from the casbah freed the architect from stylistic references to the architecture of the old city (Fig. 67). Bienvenu organized the project as one building, a perimeter structure that surrounded a communal court. The court was reached from Avenue Ahsan by a monumental stairway; a new mosque on the other side of the road, but on the same axis as the stairway, provided the community with an essential amenity and created an architectural vista. A secondary street that cut through the lower part of the project and ran parallel to the avenue activated the inner landscape of the complex. The communal court acted as the main focus with shops on the ground floor. The overall symmetry of the composition around the court was broken up by the varying heights of the buildings, the tallest reaching six stories. The density and the "picturesqueness" of the resulting cluster referred to the casbah without mimicking it. The individual units consisted of two or three rooms with a kitchenette in the living room, and a deep and sheltered "patio," intended to duplicate the traditional courtyard, where the toilet was located (Fig. 68).[9]

This configuration, based on adapting a rural pattern into an urban typology, had serious shortcomings. Mainly, it worked against the intended use of the patio as an open-air living room and turned it into a secondary space as an extended bathroom and storage area. In some

cases, the residents enclosed it to gain an extra bedroom. Two problems contributed to the transformation of the patio: the fact that the apartments were often inhabited by more people than intended and the poor quality of the plumbing, which stemmed from corners being cut during construction. Despite the obviousness of these deficiencies from the first, the same pattern was repeated in many housing projects.

The Tenure of Mayor Chevallier: 1953–58

"He builds for Arabs . . . he is the mayor of Arabs, the mayor in fez [chechia ], he does everything for them." Such were the accusations Jacques Chevallier would have to defend himself against continuously during his tenure as mayor between 1953 and 1958.[10] These years marked an intense housing construction program, much of which was geared toward the local populations, in direct response to their ever-deteriorating housing conditions and the growth of squatter settlements around Algiers. Based on more than a personal love for Arabs, however, Chevallier's campaign expressed a policy to secure the future of French rule in Algeria by addressing a crucial problem that, in the mayor's mind, lay at the heart of the unrest among local populations.

In a speech Chevallier delivered during the groundbreaking ceremony of the Diar el-Mahçoul project on the eve of the War of Independence in 1953, he emphasized that the main goal was to assure "the triumph of human dignity, of French liberties, and of the future of French-Muslim civilization." Reiterating Sarrault's proposals to revise and humanize colonial policies and Lyautey's dictum that "each construction site is a battleground," he argued that "France had to build in Algeria, day and night, as much as possible, so that she would not have to worry any more about the political problem." Addressing himself to Maurice Le Maire, the minister of reconstruction and urbanism who laid the first stone of the project, he criticized the French Parliament for developing grandiose political ideas for North Africa without comprehending the real problems, without seeing the bidonvilles . For Chevallier, the drama of North Africa was not political, it was social—it was about human dignity. Nonetheless, this social drama would shape the political one if not addressed effectively.[11]

Chevallier's chief architect, Fernand Pouillon, would later recall the acuteness of the mayor's sociopolitical concerns. Pouillon recorded in his Mémoires his initial encounter with Chevallier, during which the lat-

ter articulated the essence of the problem as he saw it. The mayor also made an urgent call for immediate measures:

I want to take care of my city. She needs it. First, we must provide shelter for the inhabitants. The crisis is terrible. You will see the bidonvilles . Awful. Nothing has been done for these poor people for the last twenty years. . . . Here, everything belongs to Europeans. There is nothing for Muslims and for little people. I would like to build one hundred thousand housing units. Then we will see more clearly.

Pouillon interpreted Chevallier's long-term vision for Algeria as separatism: Algeria should be independent with a federal status, but maintain a cultural and economic link to France.[12] The housing projects built under Chevallier's leadership reveal a wide range of experimentation and a great deal of architectural ambition. The principal architects of the time were Fernand Pouillon and Roland Simounet. The following discussion focuses on their work and glances at several complexes designed by other architects.

Fernand Pouillon

The year Chevallier became the mayor of Algiers, he named Pouillon the chief architect (architecte en chef ) of the city and commissioned him to design the Diar el-Mahçoul housing development. First educated at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Marseille, then the Beaux-Arts in Paris, Pouillon had established himself in Aix-en-Provence and Marseille; by the early 1950s he had an impressive record of public and private buildings. It was most likely Pouillon's Mediterranean sensibilities and his experience in southern France that had appealed to the mayor. Unattached to any school, Pouillon's architecture represented a modernistic hybrid, learned from the local heritage as well as classical antiquity. His career in Algiers would be prolific and outlive Chevallier's, extending not only into the building frenzy of the Plan de Constantine period, but also well into the postcolonial era.

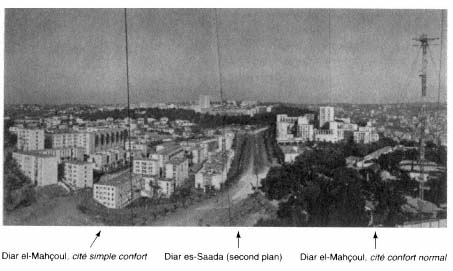

Diar el-Mahçoul, purposely named in Arabic, means "land of plenty." Its topographically complicated site on the hills above the Jardin d'Essai necessitated terracing 100,000 square meters and constructing massive supporting walls in concrete. The development was divided in two by means of a main road, creating two distinct quarters: cité confort normal and cité simple confort (Fig. 69). The former was to the south of the corniche; it afforded good views of the bay and was reserved for Europeans. The simple confort , designated for the Muslims, faced the highway and the valleys. Although first intended as 1,200 units, in its

Figure 69.

Fernand Pouillon, Diar el-Mahçoul and Diar es-Saada, view of the entire development, 1957.

completed version Diar el-Mahçoul had 1,454 units, 912 of which were simple confort .[13]

Pouillon summarized his design philosophy in his Mémoires:

I work for the pedestrian, not for the airplane captain. . . . I walk around . . . imaginary spaces and I modify them if I do not get the sensations that I want. It is them [the sensations] that come to me first, together with various geometric plans that delimit them: facades, porticos, without forgetting that other important facade formed by floors and gardens. A space is surrounded by walls, grass, trees, pavings. Everything takes on importance: materials, proportions of openings create the complement of an indispensable harmony. The architect, the urbanist, must think like a sculptor, not like a surveyor who distributes buildings alongside a street.[14]

Pouillon thus designed his housing projects with direct reference to cities. He understood the city as a network of public spaces, each public space bearing a different character that could not be explained by clear-cut typologies. A crucial issue for the architect was to establish the right relationship between buildings and public spaces as one defined the other.[15] The ambiance the architect wanted to create in Diar el-Mahçoul was culturally multilayered. In his view, historic Algiers expressed the

presence of two cultures strongly: Ottoman and Islamic Spain. In Diar el-Mahçoul, the monumental quality of the walls referred to the Ottoman ramparts, whereas the interior squares, gardens, and patios were inspired from Seville and Granada in their porticos, fountains, and cascades.[16] The architect implicitly stated that the technical ingenuity and design synthesis were French.

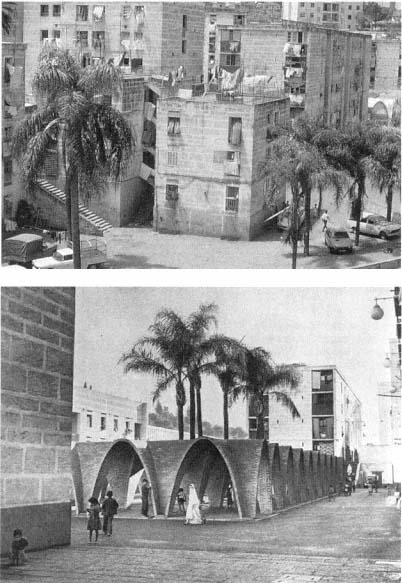

The "Islamic" qualities were expressed more strongly in the simple confort quarters, where the placement of blocks and the smallness of openings enhance the fortification-like effects and where the public squares—some planted with palm trees—are more numerous (Fig. 70).[17] The terraces on which the public squares are located interlock with each other by means of monumental stairways, fragmenting the site into more intimate zones, and the composition of volumes allows for visually active perspectives. The varying dimensions and heights (two to ten stories) of the blocks and their open staircases enliven the massing of Diar el-Mahçoul further, in both simple confort and confort normal sections. In addition to the dynamism of the massing, based on a manipulation of cubical volumes, the accessibility of the roofs referred to the architecture of the casbah in a "typological search" for an Algerian habitat.[18] Pouillon continued to explore the potential of rooftops as the women's realm in Climat de France, thus separating men's and women's public spaces and following the pattern set by the old town.

At the completion of Diar el-Mahçoul's construction, it was proudly noted in the architectural press that "nowhere could one feel any impression of repetition, of the sad monotony of barracks." Pouillon's choice of materials played a crucial role in the subtle effects he desired to create. All the walls are of a cream-colored stone, transported from the Fondvieille quarries in Provence.[19]

The communal facilities, such as the markets and the church (now transformed into a mosque), bring a deliberate contrast to the architectural unity of the housing blocks. The market in the simple confort quarter is a rectangular space surrounded by a low brick arcade, formed by cross-vaulted units; its center is planted with palm trees (Fig. 71). The market of the confort normal area again uses the arch to mark its difference from the residential functions, but here the arch is less accentuated, less "vernacular"; it is a stylized low arch that sits on an orthogonal arcade. The church, the former St.-Jean-Baptiste, was placed in the European section. A concrete structure defined by vertical thin elements, it was covered by four cross-vaults, open at the sides. Its bell tower referred to North African minarets with its square form and tripartite organization. No provisions were made for a mosque.

Figure 70.

(above) Pouillon, Diar el-Mahçoul, view.

Figure 71.

(below) Pouillon, Diar el-Mahçoul, view of market square, 1957.

Figure 72.

Pouillon, Diar el-Mahçoul, plan of a one-

bedroom confort normal apartment.

(1) living room, (2) bedroom, (3) bathroom,

(4) kitchen, (5) entry, (6) patio.

Figure 73.

Pouillon, Diar el-Mahçoul, plan of a two-

bedroom type évolutif apartment.

(1) living room, (2) bedroom, (3) water

closet, (4) kitchen, (5) entry, (6) patio.

The units ranged from two to six rooms, with the larger ones in the European quarter. In accordance with the search for a new dwelling type that would adapt and modernize the "traditional Algerian house," Pouillon cited its most prominent element, the interior courtyard, as his primary concept. The organization of the apartments incorporated considerable variation. For example, a one-bedroom confort normal apartment had an entrance hall, a living room onto which a large patio opened, a separate kitchen, and a separate bathroom with sink, tub, toilet, and bidet (Fig. 72). A two-bedroom type évolutif unit in the Muslim quarter, in contrast, had an interior patio without a view, a living room with a kitchenette in one corner, and a Turkish-style toilet with a small sink (Fig. 73).[20] One of the main deficiencies in the housing provided for Algerians was the poor quality of sanitary services, ironically betraying the French concern with reforming the habits of hygiene among the indigenous people. Nonetheless, it was reported at the time that even the most modest apartments were well built; they had good ventilation

Figure 74.

Diar el-Mahçoul during the Algerian War.

and light. In contrast to the "horrible aggregates" of bidonvilles as well as the "not very brilliant" previous social housing experiments, Diar el-Mahçoul should be considered a success, because it was not as crowded, and it was constructed well.[21]

Pouillon remained ever proud of the "humanism of [his] contemporary 'casbahs.'"[22] The project was also hailed enthusiastically by those who believed in the power of social reforms to overcome the problems France faced in Algeria. According to this view, Diar el-Mahçoul could even serve to pacify its inhabitants: an editorial in Travaux nord-africains maintained it was "highly probable that Diar el-Mahçoul would never become a recruitment center for rebellion against the established order." It was acknowledged that the scheme diverged from common practice by taking certain risks, mainly by not entirely segregating the Muslim population. Nothing could be taken for granted, however, and the future would depend on the behavior of the residents, as well as the vigilance of their guardians.[23] In fact, the War of Independence transformed the social atmosphere of the settlement, turning the public squares and gardens into proper battlegrounds and army stations (Fig. 74). For example, on 11 December 1960 about five thousand residents of Diar el-Mahçoul and the Mahieddine bidonville descended the

hills, joining the demonstrations downtown.[24] Hostilities toward the French had already surfaced much earlier. As reported by L'Echo d'Alger in March 1957, a visit by Mayor Chevallier and a group of schoolteachers to the construction site of Diar el-Mahçoul had ended with the "salutations of about one hundred little Muslims who shouted 'Algeria is ours' and who threw stones at the visitors."[25] A couple of years later, military forces would be installed in the school buildings of Diar el-Mahçoul and Diar es-Saada, as well as the high-rise structure in Diar es-Saada.[26]

Pouillon conceived Diar el-Mahçoul together with Diar es-Saada ("land of happiness"), the latter reserved exclusively for Europeans and at a good distance from the former. The construction of an artery between the two projects, however, emphasized the interrelationship of Diar es-Saada and Diar el-Mahçoul in accordance with the new mentality, advocated by Chevallier, that did not separate the indigenous population from the European.[27] Pouillon organized the site of Diar es-Saada along a main pedestrian street that turned into sets of stairs at higher slopes. A series of rectangular and L- and U-shaped blocks of various heights defined communal courts, some paved, some planted with palm trees. A twenty-story tower added to the silhouette. The project housed about eight hundred families. Here Pouillon's prototypes were European, with no reference to Algerian forms and spaces (Fig. 75). The differences from the Muslim housing units were also blatantly evident in the separation of the kitchens from the living quarters and in the design of the bathrooms with full facilities.[28]

In addition to Pouillon's project, there were three other housing types in the area, to the west of the cité simple confort . The farthest from the new development was a bidonville , a trace of the original pattern before municipal interventions. The second, situated above the shantytown, consisted of minimal barracks for "emergency rehousing" (recasement d'urgence ). The third, the "transit housing," was formed of two-story longitudinal buildings. Both emergency housing and transit housing were considered temporary solutions to the bidonville problem.[29] Therefore, this site revealed all stages and forms of low-cost "mass housing" for Algierians: spontaneous, temporary, and permanent, the last in its most ambitious format. Farther away, although still part of the same complex, were the "better" collective housing developments for Europeans.

Pouillon also designed the most spectacular and extensive project of Chevallier's tenure, the Climat de France complex. On a sloped site to the west of the casbah with views toward the Mediterranean, its

Figure 75.

Pouillon, Diar es-Saada, plan of two-

and three-bedroom units. (1) living

room, (2) bedroom, (3) bathroom,

(4) kitchen, (5) entry, (6) patio.

Figure 76.

Pouillon, Climat de France and vicinity, site plan.

(1) Pouillon, Climat de France, (2) Bienvenu,

Cité Boucle-Perez, (3) Simounet, Daure, and Béri,

Cité Carrière Jaubert.

most memorable structure, the 200 Colonnes, defines its focus. The site is like an island, surrounded by major roads—Boulevard Mohamed Harchouche to the west defining the highest boundary, Avenue Ahsan marking the lowest area to the north, and Boulevard el-Kattar to the east. This tight circumscription allowed Pouillon to treat the development as a small town with its own hierarchy of streets, squares, monuments, and residential zones.

Pouillon conceived the 4,000-unit development covering an area of 30 hectares as a conglomeration of distinct nodes, each with its own streets and open squares (Fig. 76). The northern boundary was fixed by an Aaltoesque building whose curvilinear lines followed the contour of Avenue Ahsan. The pedestrians were to walk between the buildings (and sometimes cut through the buildings), following narrow, often

stepped, paths interrupted by paved and planted public squares of varying sizes. The two main arteries ran perpendicular to the slope in the northeast-southwest orientation and connected Avenue Ahsan with the 200 Colonnes and Boulevard el-Kattar with the second largest plaza. Lateral connections were provided mainly from the east. The blocks were carefully placed with respect to each other to allow for uninterrupted perspectives to the sea. They were grouped in four types: linear buildings, those with interior courtyards, a series of buildings linked to each other, and single towers. Like in Diar el-Mahçoul, Pouillon varied building sizes greatly and sought for a compositional balance in the placement of large and small structures. Terracing of the terrain to manipulate its 25 percent natural slope helped animate the massing.[30]

The siting of the Climat de France was applauded by Jacques Berque (writing on housing issues in Algiers at the time), who labeled it "geological urbanism" because of its sculptural treatment of large blocks. He suggested that Pouillon's approach to landscape, characterized by the "petrification and crystallization" of the site, paralleled the former aspects of médinas , which had evolved spontaneously. The resulting image is so multivalent that G. Geenen, A. Loeckx, and N. Naert argue that there are three distinct images: viewed from the northeast, Climat de France evokes the image of a new casbah; from the northwest it resembles a small fortified town; and approaching the development closer from the northwest, it appears like actual fortification.[31]

The massing and architectural vocabulary of Climat de France was similar to Pouillon's experiments in Diar el-Mahçoul: his crisp, geometric volumes were pierced by small modular openings (windows and ventilation holes); the bold expression of bricks and stones enhanced the architectonic qualities of the facades; the rectilinear arcades of the ground floors complemented the series of square openings that defined the roof terraces. Although not acknowledged by Pouillon, the influence of Italian rationalist architecture is clear on this formal language, making the architect a pioneer neorationalist. As such, he is a predecessor to Aldo Rossi, whose work would display a striking similarity to Pouillon's fifteen years later. Pouillon's affiliation with Italian rationalism did not carry political undertones, but should be understood within the context of his broad search for a contemporary Mediterranean architecture that brought together modernism with local forms, needs, and sensibilities.

The apartment units of Climat de France can be grouped into three main categories: "double-exposure type," "single-exposure type," and "particular solutions" that also included "buildings with patios."[32]

Figure 77.

Pouillon, Climat de France, plan of a "double-exposuretype" unit with two bedrooms.

(1) living room, (2) bedroom, (3) water closet, (4) kitchenette, (5) entry, (6) patio.

Figure 78.

Pouillon, Climat de France, plan of apartments in a

"patio-type" building. (1) living room, (2) bedroom,

(3) water closet, (4) kitchenette, (5) entry, (6) patio.

Units with double exposure (40 to 50 square meters) occupied the entire width of the building, and a staircase served two units on every floor (Fig. 77). In general, the units consisted of one or two bedrooms, a living room with an open kitchen corner, and a toilet-shower closet immediately off a small entry hall. Units with single exposure were grouped in fours around a "sanitary core." Smaller than the first type (about 30 square meters), some had one bedroom and a living room, while others accommodated the two functions in a single space. The kitchen was again in a corner of the living room and the toilet-shower area off the entrance. Of the third type, the "particular solutions," the "patio scheme" allowed for the grouping of twelve apartments around an inner court and facilitated cross-ventilation (Fig. 78).

With few exceptions, each unit was equipped with a deep balcony protected by a perforated wall, by now the customary substitute for the courtyard. Aside from providing privacy and shade, these walls made a formal reference to mashrabiyyas and integrated an element of the "traditional" urban house into the facades. The arrangement of the entrance hall so that direct views were obstructed from the main door into the living spaces by the careful placement of the toilet-shower closet was another attempt to respond to local forms and customs.[33]

Figure 79.

Pouillon, 200 Colonnes, overall view.

In the center of Climat de France sat the 200 Colonnes, a vast rectangular housing block with a monumental agora, 233 meters long and 38 meters wide, as its court; the similarity of its size to the Palais Royale in Paris was a matter of pride (Fig. 79).[34] The courtyard was surrounded by a three-story-high colonnade made up of two hundred square columns that gave the project its name. In addition to apartments, the complex was to shelter two hundred shops and act as the heart of the entire settlement, considered an "absolutely autonomous" area complete with its own educational, commercial, and health services.[35]

Aside from the obvious references to Hellenistic agoras, Roman fora, the Place des Vosges in Paris, and the Court of Myrtles and the Court of Lions in the Palace of the Alhambra, the 200 Colonnes also displayed several obscure influences. With this building, Pouillon admittedly turned away from the "charming" effects he had achieved in his former projects in order to create a "more profound, more austere plasticity." He thus moved from the "arabesques of Algiers" and toward the south, to the Sahara, the towns of Mzab and the ruins of el-Goléa and Timimoun—all of which, he wrote later, gave him a lesson in formal austerity, as well as a new sensibility with numbers and proportions.[36] Greatly revered by modernist artists and architects, the architecture of the Mzab is characterized by its simple rectilinear geometries and blank walls; fur-

thermore, the two villages Pouillon specifically refers to have rectilinear, "rational" street plans.

Two years before Pouillon started working on 200 Colonnes, he had visited Isfahan, a very different Islamic city. Isfahan's seventeenth-century Maydan-i Shah had made a great impression on him.[37] Maydan-i Shah is an introverted public space, surrounded by a continuous two-story colonnade. Its longitudinal axis linked the Masjid-i Shah, built at the same time as the Maydan, with the preexisting markets. The Maydan has two axes in the other direction; the major one connects the Lutfullah Mosque to the Ali Qapu Palace, while the other axis simply opens into the existing fabric on each side. The axiality in Pouillon's "maydan" echoes this pattern: the main axis, marked with hypostyle hall-like entrances, crosses the court lengthwise while the short axis is off center, as in Isfahan. The other gates to the court do not define axial connections and, devoid of columns, assume a secondary role.

The main entrances to the 200 Colonnes (on the shorter facades) were delineated by protruding propylaea that mirrored a fragment of the interior colonnade on the outside. Monumental stairs adjusted the gates on the longitudinal facade to the sloping site, meanwhile enhancing the differentiation between entrances. The variation in their size and monumentality alluded to the two scales the project combined: urban and residential. The contrast between the exterior and the interior facades turned the building inside out, making the interior public and urban. With its small, receded openings and dominant planar quality, the exterior facade made reference to city walls—a theme dear to Pouillon, as observed in Diar el-Mahçoul. In addition, the treatment of the facade as a modular tapestry was inspired by the carpets made in southern Algeria,[38] and the emphasis on crisp geometry evoked the flavor of the casbah. The inner facade, in contrast, was and remained the "austere" and open one, its public nature expressed by the colonnade behind which the vaulted entries to the shops were lined.

The roof terrace was a major feature of the 200 Colonnes. Pouillon borrowed the concept from the casbah rooftops, appropriated by women as their own public and private spaces. He made the stairs climbing up to the roof particularly narrow to emphasize the domestic and private nature of the passageway and as a reminder of the stepped streets of the old town. The immense roof terrace—dotted with small, domed washhouse pavilions placed at regular intervals—was intended as a place for work and socialization for the women who lived in the building. The drying laundry would add a colorful background to the picturesque scene created by groups of women and children. The women of 200

Figure 80.

Pouillon, 200 Colonnes, plan of units. (I) living room, (2) bedroom, (3)

water closet, (4) kitchenette, (5) entry, (6) patio, (7) public hallway.

Colonnes, however, refused to climb up the narrow stairs with basketfuls of laundry and, despite the inadequacy of the provisions, chose to wash their clothes in their apartments. To dry the laundry, they projected rods from the windows, thus adding unintentionally to an atmosphere of "authenticity," so cherished by Pouillon.

The units of 200 Colonnes were of the "double-exposure"/one-bed-room type, according to the formula described earlier (Fig. 80). Albert-Paul Lentin, a critic of French colonial policies in Algeria, contrasted the "futurist ridicule" (tantinet futurist ) of the building's exterior appearance with the design of the apartments, clearly conceived for the "underdeveloped." He described them as having "two rooms with low ceilings (2 meters high), one 2 by 3 meters, the other 3 by 3 meters large, a tiny kitchen, a water closet, narrow windows."[39]

Pouillon defended his scheme not only as architecture but also as agent of social reform catering to the Muslim, who had been acknowledged until then as only an indigène —a term loaded with "pejorative and humiliating" undertones. The architect proudly announced that here, "for the first time [and] thanks to Mayor Chevallier, Algerians would live in a real city." Intended for the lowest income groups, 200 Colonnes met all the requirements for a monumentality commonly reserved for official buildings of prestige. Pouillon himself referred to this building as "the monument of 'Climat de France'" and argued that he had "installed men in a monument . . . perhaps for the first time during modern times." Furthermore, he continued, "these men, the poorest in poor Algeria, understood it. It is they who baptised it 'Two Hundred Columns."'[40] In tune with Mayor Chevallier's paternalistic benevolence aimed at engraving a sense of pride in the residents, Pouillon saw himself bringing a new urbanity to this chaotic fringe of Algiers.

It was reported repeatedly that the apartments in Climat de France seemed like "paradise" compared to the shantytowns. Relying on this assumption, an administrative report quoted by Lentin stated that "the settled, well-housed population of 'Climat de France' is less fidgety than that of the neighboring casbah." Lentin ironically noted, however, that this population had decided to "move" too, and had joined the rebelling crowds. To cite one incident, sixty people from the 200 Colonnes were killed by the French forces in the massive demonstration on 11 December 1960.[41]

Roland Simounet

Pouillon's sweeping approach to architecture and urban design and his radical interventionism vis-à-vis site conditions present a contrast to the architecture of Roland Simounet. Simounet's responsive and imaginative buildings gained him respectable status and a place among Chevallier's leading architects, despite his relative youth and his blatant disapproval of the aesthetic sensibilities of Pouillon, the mayor's chief architect.

Simounet was greatly inspired by the work of Le Corbusier, but he was also a careful student of Algerian architectural culture, with a focus on the Algerian vernacular. His architecture was shaped by the lessons he learned from European modernism, his respect for the site, and his inquiry into vernacular residential forms (including squatter houses) and patterns of daily life and ritual.[42] In a retrospective evaluation in 1980 that maintained the fervor of the debate of the 1950s positing Pouillon and Simounet as polar opposites, Pierre-André Emery, another Algiers-based architect of Le Corbusier's school, criticized Pouillon's urbanism by suggesting that he could have learned a thing or two from the contextual approach of the turn-of-the-century Austrian architectural theorist Camillo Sitte and dismissed Pouillon's architecture for being "very personal" and not relating either to the site or to the local context. Simounet's work, in contrast, stood out with its "plastic language that had evolved naturally , allowing [the architect] to resolve new problems simply "—in the words of Jean de Maisonseul, another member of the same circle.[43]

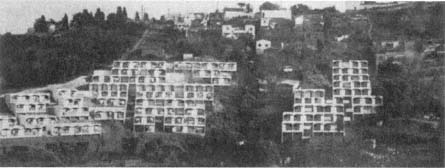

Simounet's first housing project was a collaboration with Parisian architects A. Daure and H. Béri, who had won a competition to design the vast complex of La Montagne, intended solely for Muslims in 1955.[44] Located above Bel-Air and to the west of Maison-Carrée on the hill of the same name, the settlement consisted of two parts: "col-

lective" housing (walk-up apartment blocks) on the summit and individual houses on the slopes (Fig. 81). Communal facilities, namely a market, shops, baths, and "Moorish cafés," constituted the rest of the program.[45]

The architecture of La Montagne displayed Simounet's respect for the customs and habits of the future residents, especially in the design of individual units. The apartments in the longitudinal blocks of the collective housing had an unusual plan type, with two loggias facing opposite directions (Fig. 82). The living room (with a kitchenette) was sandwiched between the loggias, and the two bedrooms were interconnected, resulting in a peripheral circulation pattern. The architect separated the elementary functions that occurred in the courts of the "traditional" houses: the narrower loggia in the back acted as the entry zone, whereas the front loggia housed the water closet. Cross-ventilation, "indispensible in Algeria," was provided in all spaces. The tiny kitchenette, however, squeezed in a corner of the living room, was not adequate for cooking for large families.

The architectural conception of the individual house stemmed from the "independence of the entrance from the kitchen and the patio—both reserved for women."[46] Units with one or two rooms were placed in rows, and the topography of the site was utilized to energize the overall massing of the settlement. The entrance of each unit was through a small court, to which a general room, the bathroom, and the abri (a sheltered but not enclosed space where the kitchen was placed) opened (Fig. 83). Separated from the entrance, the garden became a private place. In the larger units, a second room, in line with the first, connected to the garden. The "horizontal" housing in La Montagne was developed on the basis of a prefabricated construction system consisting of load-bearing walls and double-shelled (ventilating) vaults. Responding to the irregular topography, the siting of the rows allowed for the vaults to be oriented in three directions, thereby introducing a subtle plasticity to the overall composition. Two reasons dominated the choice of vaults: to evoke the picturesque character of indigenous forms and to discourage vertical additions that would increase densities and damage the unity of the nuclear family. In the housing discourse of the time, overcrowding and cohabitation were considered "destroyers of family life."[47]

The architecture of the shops and workshops echoed that of the "horizontal" housing in its attempt to create an "indigenous" environment (Fig. 84). Rows of shops under vaults repeated a regular pattern that accommodated prefabricated construction techniques in four types responding to different needs. Capitalizing on his knowledge of local

Figure 81.

(above) Roland Simounet, A. Daure, and H. Béri, Cité La Montagne, model, 1955.

Figure 82.

(below) Simounet, Daure, and Béri, Cité La Montagne, plan of units in an apartment block,

1955. (1) living room, (2) bedroom, (3) water closet, (4) kitchenette, (5) entry, (6) loggia.

Figure 83.

(above) Simounet, Daure, and Béri, Cité La Montagne, plan of low-rise

unit, 1955. (1) room, (2) shelter, (3) garden.

Figure 84.

(below) Simounet, Daure, and Béri, Cité La Montagne, plan of shops, 1955.

lifestyles, Simounet created sitting areas for informal socialization in front of shops, as well as inside some, and gave the majority of shops a private court in the back.[48]

"Horizontal" housing, now considered most appropriate for the most recent immigrants to Algiers because they had the strongest ties to rural living, was also envisioned for Cité Dessoliers in the Ste.- Corinne quarter of Maison-Carrée. Roland Simounet's contribution to this settlement, commissioned to several teams of architects, was a cellular scheme that attempted to relate to the slight slope of the site. Consisting of two rooms, courtyard, kitchen, abri, and water closet, the individual unit duplicated many characteristics of La Montagne.[49]

Despite their problematic initial collaboration, in 1957 Simounet worked with Daure and Béri on another housing project, the Cité Carrière Jaubert, named after the stone quarries nearby.[50] Carrière Jaubert was part of an experiment in "transit housing" to provide temporary shelter for the residents of demolished bidonvilles, who would eventually be moved to newly built permanent housing projects. Considered as a "transit hotel," a caravansary around a vast courtyard, the complex would shelter sixteen hundred apartments in a tripartite composition. Of this ambitious scheme, only the central unit was realized, reducing the original program by half.[51]

The result was a huge, fortresslike structure, a long rectangular building around a narrow courtyard that maintained its references to a large caravansary (Fig. 85). The regularity of the plan was deceptive, as the architects used several devices to animate the massing. The building adhered to the topographic conditions, with the heights of different sections varying along with the sloping site. The fragmented silhouette attempted to inscribe the building into the site in a manner reminiscent of the old stone quarries.[52]

The units were kept small, with the majority consisting of two spaces, an 18-square-meter living room and a 7-square-meter loggia. Simounet's drawings of the interiors revealed the architect's vision of life in these units, where nothing was permanent and the sparse furnishings were transportable (Fig. 86). Two variations accommodated larger families: a "twin" unit, formed by combining two neighboring units, and a duplex. Every unit received light and cross-ventilation. There were, however, no washing and toilet facilities in individual apartments, but a communal lavatory could be reached by means of the back corridor, the latter considered an inner "street" that periodically opened up onto a "communal space." The concentration of hygienic facilities

Figure 85.

Simounet, Daure, and Béri, Carrière Jaubert housing, axonometric view.

stemmed from economic considerations but also fit the idea of a caravansary and could be easily justified as communal places derived from local culture. References to traditional living patterns were reiterated by drawing parallels to the public fountain and the bath, the hammam. Issues of privacy related to gender differences—a recurrent theme in the discourse on the Algerian home life—were totally ignored.[53]

Following his architectural collaborations, Simounet had the opportunity to work independently on a housing project, the Djenan el-Hasan. Widely published and discussed, this project established Simounet's reputation as one of the most talented architects in Algiers. In the vicinity of Climat de France, on the southern slope of M'Kacel Valley, the 210 units of Djenan el-Hasan were intended to rehouse temporarily one thousand former residents of the demolished bidonvilles in the area. Confident in his knowledge of the residents' lifestyles and former living conditions, and experienced in low-cost housing issues, Simounet accepted the challenges of the project—the difficulty of the site and the economic restrictions—with great enthusiasm.[54]

The scheme, described as "between vertical and horizontal," accommodated eight hundred inhabitants per hectare, compactly settling as a series of terraces on the steep slope of the terrain (Figs. 87 and 88).[55] The superimposed uniform, vaulted units reinterpreted, rationalized, aestheticized, and synthesized the lessons Simounet had derived from the

Figure 86.

Simounet, Daure, and Béri, Carrière Jaubert housing, sketches and plan of units, 1957.

casbah and the bidonville. The overall image borrowed at the same time from the architecture of Le Corbusier, in particular the 1949 Roq et Rob project in Cap St. Martin—a particularly relevant scheme in the "Mediterranean" tradition and on a dramatically steep site. Rationalizing the street network of the casbah, Simounet developed here a complex circulation system that responded to the site and opened up to communal

Figure 87.

(above) Simounet, Djenan el-Hasan, overall view, 1959.

Figure 88.

(below) Simounet, Djenan el-Hasan, partial site plan, 1958.

spaces. It consisted of two interconnected networks: single-level paths and stepped paths. Horizontally laid out paths on leveled terraces served the individual units, as well as separating them from the concrete foundation walls of the neighboring terraces above. Stepped paths in staggering rows ran perpendicular to the horizontal ones and the contours of the land. A public patio was placed next to each staircase for ventila-

tion and good views. All existing trees on the site were preserved and "productive trees" (mainly fig trees) were planted in the communal zones.

Siting principles and the circulation system made the units "strictly independent" and gave them "absolutely uninterrupted views." A strictly modular system, derived from Le Corbusier's Modulor, organized the complex and the two types of apartments. The first type consisted of a single room, about 12.4 square meters large, and a loggia of 4 square meters; a water spigot and the toilet were located on the loggia. Each room boasted "a well-lighted corner" and "permanent ventilation" from the French windows (porte-fenêtres ) that connected the living room to the loggia, and the door that opened to the alleyway behind. The second type was a duplex. Its upper level replicated all characteristics of the first type, while its lower level was made up of a single room; an interior stairway linked the two stories.

The load-bearing walls in concrete masonry blocks carried the vaulted, tile-covered roof. The blocks were deemed to provide good thermal insulation and resistance to rainwater and wind. On both the interior and the exterior, the walls were whitewashed. The sanitary system was enclosed within the construction, with access doors at the top for easy repairs. This avoided the previously common practice of breaking open the walls to get at the pipes.[56]

Simounet's apartment designs recalled closely the ones he had developed for Cité Carrière Jaubert, both projects intended for the most destitute members of the Algerian population. Aside from the gridlock of their economic situation as recent immigrants to the city, these people were confronted with a new lifestyle, in their encounters not only with urban colonial culture, but also with an Islamic urban culture. As recorded over and over by French ethnographic studies, life and the forms that accommodated life were drastically different in the Algerian countryside—a phenomenon whose correspondence to the differences between Arabs (urban) and Berbers (rural) was insistently stressed. The housing developments of Djenan el-Hasan and Carrière Jaubert focus on this difference as well as the transitional situation of the immigrants which Simounet had studied in the bidonvilles:[57] fitted within a strict matrix, the residential units themselves resemble nomadic structures. They provide basic shelter, and their grouping reinterprets and regularizes the "organic" quality of gourbis . In these projects Simounet developed a new dwelling type distinct from the "horizontal" schemes and the multistory blocks with apartments essentially based on European

precedents. Despite their intended "temporary" status, the buildings embodied a powerful permanency due to their architectural imagery and construction techniques—in contrast, for example, to the single-story barracks next to Diar el-Mahçoul built as temporary housing, which seemed ready for dismantling at any time.

Another issue raised by Djenan el-Hasan and Carrière Jaubert is the degree of commitment to the "civilizing mission" of French colonialism. A consideration of the sanitary facilities in these projects—as well as all other projects to varying degrees—reveals conflicts between enforcing hygienic reforms and considering economics. Given that the sanitary amenities of indigenous housing had been a major point of criticism by the French, the provisions in the housing built for new immigrants cast doubts on the sincerity of efforts to improve the living conditions of local populations. In view of the resulting hygienic facilities (bathrooms and kitchens, but especially bathrooms), the elaborate lip service paid to the "customs and needs" of "indigenous people" seems in conflict with the agenda to "civilize." The residents were persistently denied the most basic technological comforts of European "civilization" in the very projects intended to ease their transition to a better life.

Like Carrière Jaubert and other "transitional" housing projects, Djenan el-Hasan eventually became permanent shelter. Nevertheless, lack of space had turned into a major issue immediately after completion of the settlement. According to projected figures at the time of the development's conception, an average of five people would live in each unit in Djenan el-Hasan.[58] Mainly due to the continuous flow of new immigrants joining their extended families, this number turned out to be much higher. As the tight site plan did not allow for any incremental growth—an essential characteristic of squatter housing—the only answer to lack of space was to turn the loggia into living quarters. This intervention robbed each apartment of its breathing space and transformed both the quality of the well-lighted and well-ventilated interior and the plastic integrity and aesthetic rhythm of the exterior. The numerous materials employed in the later additions were chosen for their cost and availability, rather than in light of the original construction. The result was an overall patchy appearance that again disrupted the formal purity of Simounet's design. Finally, to make up for the loss of the loggias, the residents installed horizontal rods from their windows to dry their laundry, pushing the limits of their units into the open air, as the residents of 200 Colonnes and other new housing projects had done.[59]

Chevallier's Other Architects: A Sample

Mayor Chevallier's massive campaign for housing created opportunities for numerous architects, some based in Algeria, others in France. Restricted by economic considerations, focused on quantities, and built in haste, these projects were not memorable architectural creations and their success in providing decent living conditions was limited. However, their impact on the city of Algiers was significant. They played an important role in the shaping of the outskirts of Algiers in a process that recalls many cities throughout the world. Islands of new structures surrounded the city and contrasted with the congested architectural pluralism of Algiers proper. Because each housing project was treated as an individual unit without much consideration of its context and its links to neighboring settlements or the city itself, the resulting conglomeration lacked an urban cohesiveness. The projects themselves displayed a range of experimentation in their massing, architectural vocabulary, and unit plans.

The majority of housing complexes were high-rise ensembles , with low-rise projects few and far between. In the Cité Dessoliers in Maison-Carrée, the team of Barthe, Cazalet, and Solivères designed 250 "cells" of one, two, or three rooms that were covered by cement vaults and organized in six groups (Fig. 89). Each unit boasted a simple kitchen corner and a patio where the water closet/shower was located. The stated goals were "light, comfort, independence, and low cost."[60] Architects Georges Bize and Jacques Ducollet, responsible for another six hundred units in the same location, stated proudly that every unit was equipped with electricity, water, and sewage lines. These houses were "evidently very simple," yet they "conformed perfectly to the needs of the occupants, who, being used to gourbis , needed to adapt to an improved installation little by little." The dominant "simplicity" called for some justification and it was argued apologetically that while cost played an important role in the outcome, the Dessoliers housing still displayed the will of the authorities to do away with the "horrible plague of bidonvilles ."[61]

The Groupe des Cyclamens, an apartment complex in Clos Salembier, was organized as four individual but attached blocks. Louis Bérthy (whose site-abstract project for a cité indigène in 1939 was a horizontal scheme that quoted many aspects of local architecture) created here one hundred type évolutif units in six-story walk-ups, with four units per story in each block (Figs. 90 and 91). The unit sizes varied from one to

Figure 89.

(above) Barthe, Cazalet, and Solivères, Cité Dessoliers, overall view, 1954.

Figure 90.

(below) Bérthy, Groupe des Cyclamens, perspective drawing, 1957.

Figure 91.

Bérthy, Groupe des Cyclamens, typical

floor plan. (1) living room, (2) bedroom,

(3) water closet, (4) kitchenette, (5) entry,

(6) loggia, (7) public hallway.

four bedrooms, with three-bedroom apartments constituting the majority.[62] These were minimalist units that incorporated the few features determined to conform to the needs of "evolutionary" indigenous families: kitchenette in a corner of the living room, a loggia now reduced to a width of 1 meter (thus unusable as an extension of the living space and offering no privacy), and a water closet about 2 square meters that included a toilet, sink, and shower. The facades expressed the floor plans in a straightforward manner, the recesses of the balconies creating light and shade contrasts; a rectilinear geometry, generated by the prefabricated construction system, dominated the scheme. The architectural vocabulary and the massing aspired to Pouillon's principles in nearby Diar el-Mahçoul.[63]

Groupe des Cyclamens's east-west orientation was dictated by Gérald Hanning, the director of the Plan d'Urbanisme, to harmonize with the forthcoming Cité de Nador. Cité de Nador was built on a site cleared of squatter houses in 1955 and connected by a new road to the Route de la Femme Sauvage.[64] The architects in charge—Mauri, Pons, Gomis, and Tournier-Olliver—opted for two "bars," 100 and 72 meters long, respectively, forming between them a wide angle open to the south (Fig. 92). A predecessor of the Plan de Constantine schemes, this was perhaps the most uniform, and therefore the most economical, of all the housing projects realized under Chevallier. Each of the sixty-two units here was the same; about 35 square meters large, it consisted of a living room, a bedroom, a loggia/drying room (loggia-séchori ), a kitchenette, and a water closet.[65]

A review of the projects designed during the 1950s reveals a pattern shaped by adherence to a short checklist of prerequisites presumed essential. In the Cité des Eucalyptus at the border of Hussein-Dey and Maison-Carrée, architects Bize and Ducollet prioritized "maximum

Figure 92.

Mauri, Pons, Gomis, and Tournier-Olliver, Cité de Nador, view, 1958.

economy, solidity, and comfort" for the 600 units they designed (Fig. 93). Of these units, 450 were accommodated in longitudinal blocks placed in rows, whereas 150 were duplexes around communal courtyards. The long blocks bordered the main road connecting Algiers to el-Harrache; the duplexes were in the back. By placing the blocks perpendicular to each other, the architects created a hierarchy of public open spaces, interspersed with public facilities.

The 40-square-meter individual units in the higher blocks of the Cité des Eucalyptus repeated a similar configuration, the formula that had evolved from a consensus on the lifestyle of indigenous people: the combined living/cooking space opened to a terrace and a minimal bathroom space (in this case 0.75 square meter for a toilet, sink, and shower). The duplex units had a double-height living room and a kitchen-bathroom combination on the ground level and two bedrooms on the second floor (Fig. 94). A major difference from the earlier schemes was the placement of the bathroom inside the unit as opposed to its former location in the loggia, a change that stemmed in part from the diminished size of the latter. The toilet and the kitchen now became a unit (with the toilet door opening directly into the kitchen) in a most unhygienic combination. Perhaps it was again the new dimensions of the loggia that led the architects to make provisions for privacy in the Cité des Eucalyp-

Figure 93.

Bize and Ducollet, Cité des Eucalyptus, axonometric view.

Figure 94.

Bize and Ducollet, Cité des Eucalyptus,

plan and section of low-rise unit. (1) living

room, (2) bedroom, (3) bathroom,

(4) kitchenette, (5) entry, (6) patio,

(7) public hallway.

tus by including high screens that allowed for "correct ventilation" while satisfying the Muslims' "taste for apartments sealed off from the exterior."[66]

On Rue Léon-Roches at the periphery of Climat de France, Cité Taine E was built specifically for the families whose house were expropriated in the Marine Quarter. Architects Daure, Béri, Chauveau, and Magrou again relied on the template devised for loggias, kitchens, and bathrooms. Reliance on prefabrication validated the construction of a simple rectangular scheme, a north-south oriented "bar" that was 153 meters long and 11.15 meters wide. Twelve stories high, Taine E provided 284 apartments of mostly three rooms apiece and an average of 47 square meters. Inspired by the social amenities Le Corbusier had in-

Figure 95.

Nicholas Di Martino, Cité des Asphodèles, site plan.

corporated into his Unité d'Habitation, this project designated the top floor for a nursery school and children's playground.[67]

Thin, longitudinal blocks that could be placed with relative facility and without constructing ample terraces on the hills of Algiers became increasingly popular in the late 1950s. The form also catered to prefabricated construction systems efficiently and allowed for units to have cross-ventilation, if at times through the communal corridors—the "inner streets." In the Cité des Asphodèles on the northwestern hills of Algiers, Nicholas Di Martino attached the bars to each other, creating T-shaped buildings and open spaces between them that were meant to be shared by the residents (Fig. 95).[68] The facades were enlivened in a pattern that had become customary: the depth of the loggias provided a shadow contrast and the lattice-blocks of the water closets alluded to local architectural forms and geometric ornaments.

As Deluz argued, Chevallier's "humanist urbanism" followed in the footsteps of Marshal Lyautey, who had summarized his philosophy in several memorable remarks, among them "urbanism must be implanted first in the hearts of men."[69] Founded on the belief that urbanism could be used as a tool to reshape people's lives and, in the colonial context, gain the confidence of the local people by improving their living conditions, Chevallier's approach was considered the humanistic alternative to militaristic policies. Innumerable statements about the assumed power of good environments on people make it plain that the underlying agenda for the housing projects in Algeria was the pacification and control of colonized people by meeting one of their basic needs. In

meeting this need, Chevallier, together with his architects and urban planners, had attempted to understand the sociocultural structures of Algerian people and address them in their projects. To do so, they turned to the discourse on the "traditional" urban forms, the Algerian house, the Algerian family, and the Algerian woman—a discourse whose history was almost as long as the French occupation. By appropriating, taming, and rationalizing the domestic settings and their urban environments, the architects attempted to enter a realm of Algerian life whose obstinate impenetrability had become a source of colonial anguish.

Realities of the Algerian War proved that housing or other kinds of social reforms would not weaken the struggle for independence. Resistance to colonial rule found shelter even in the most thoughtfully designed new housing projects. Faced with the failure of social engineering and shaped by a more technocratic mentality, the next wave of construction in Algiers focused obsessively on numbers and ignored the humanistic dimensions of Chevallier's tenure.

Plan de Constantine: 1958–61

The urban interventions done according to the provisions of the Plan de Constantine were fragmentary with clearly delineated zones, among them the ZUPs (zones à urbaniser en priorité ), which would find their way to France. Fifty thousand housing units per year were projected, as compared to the eighteen thousand built in 1958. This quantity dictated that the form of housing be large blocks exclusively. The units designed for Muslims would "transpose the traditional houses onto vertical plans," in conformity with previous experiments.[70]

The pressing issue was the uncontrollable expansion of bidonvilles . The Cité Mahieddine, on a bulldozed shantytown, would consist of eighteen hundred units, in eleven blocks reserved for the fourteen hundred families that had resided in the bidonville , and three towers whose occupants would come from elsewhere. The huge project occupying a 7-hectare area was delegated to the architectural team of Gouyon, Bellisent, Régeste, Toillon, Dupin, and Goraguer. The two existing villas in the center, classified as "historic monuments," were preserved together with their gardens. A grid organized the site plan; the buildings

were designed as simple "bars," with a single longitudinal unit occupying the entire width. Public hallways running along the entire back facades led to stairways and, in higher buildings, to elevators.[71]

Two years later, only five hundred units were completed. Yet L'Echo d'Alger praised, more than anything else, the "human and social" dimension of the enterprise. Residents of the bidonville , temporarily housed in barracks in Clos Salembier and Diar el-Keif, would now be transported to their new residences, the "hearth of [their] dreams," in army trucks.[72]

The team of Gouyon, Bellisent, and Régeste also undertook the design of Cité Faizi on Route Nationale 24, about 4 kilometers from Algiers. The four-story, 800-unit blocks repeated the bar formula, the linear blocks placed at right angles to each other. The one- and two-bedroom units were accessible once again from a back corridor (Fig. 96). the loggia had diminished considerably in size and although it was accessible from both the living room and the kitchen, because of its location off the kitchen, it served as an extension to that room. The total separation of kitchens and bathrooms—the latter much larger and better equipped than those of the earlier schemes—showed an improvement in sanitary provisions.[73]

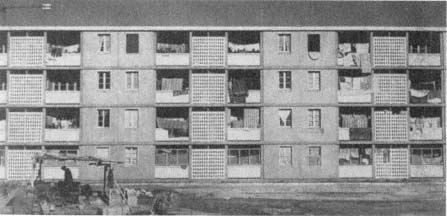

Gouyon, Bellisent, and Régeste quickly became known as experts on low-cost housing for Algerians. They were commissioned to design the Cité des Dunes in Maison-Carrée, in collaboration with a fourth architect, Brusson. Taking advantage of the flat site, the architects exaggerated the bar scheme to its limits. The two blocks that ran parallel to each other were immense walls twelve stories high—one 200 and the other 330 meters long (Fig. 97). They sat crudely on the site, and no attempt was made to provide public spaces, parks, or gardens. The 850 apartments were lined along a back hallway intended to provide cross-ventilation to each unit. One of the last and most dreary projects to be completed by the French in Algiers, the Cité des Dunes represents best the number-oriented mentality of the Plan de Constantine technocrats.[74]

Other architects continued to build predictable schemes. For example, Challand replicated the planning principles of Cité Mahieddine in the Cité Diar es-Shems, built on the site of a large bidonville to the west of Clos Salembier, by placing shorter bars vertical to long ones.[75] As in the Mahieddine complex, the proximity of the blocks to each other, coupled with the heights of eight stories minimum, resulted in a very dense settlement with unpleasant leftover space between buildings.

Figure 96.

(above) Gouyon, Bellisent, and Régeste, Cité

Faizi, unit plans. (1) living room, (2) bedroom,

(3) bathroom, (4) kitchen, (5) entry, (6) loggia,

(7) public hallway. Figure 97. (below) Gouyon,

Bellisent, and Régeste, Cité des Dunes,

axonometric view.

The prefabricated structures had a uniform plan, by now accepted as the most efficient and economic solution for long and thin blocks (Fig. 98). A hallway in the back connected all the units to the circulation cores. A main feature that distinguished these units from the previous ones was an entry with a kitchen corner into which a relatively large bathroom opened, still a hygienically problematic arrangement. In a common pattern, the loggia accessible from the main room was later closed off by the occupants to gain extra space.

Marcel Lathuillière and Nicholas Di Martino's Cité Haouch Oulid Adda in Hussein-Dey again relied on prefabricated, four-story-high bars, in a layout described by Deluz as an example of "the misorgani-

Figure 98.

Challand, Diar es-Shems, plan of apartments.

(1) living room, (2) bedroom, (3) bathroom,

(4) kitchenette, (5) entry, (6) loggia,

(7) public hallway.

zation of spaces and absence of all elements of urban life" (Figs. 99 and 100). The novelty in this scheme was the placement of a large sink off the loggia, in addition to the water closet inside the apartment. The separation of the "wet" zone in the loggia from the exterior by a latticelike panel helped to enrich the monotonous facades.[76]

In addition to their mediocre spatial planning, the housing projects of the Plan de Constantine period are characterized by poor construction. Dominated by an obsession with pace at the cost of everything else, the architects opted for building systems that allowed for the most efficient organization of the construction site. The prefabricated panels, though assembled quickly, were not insulated, and little attention was paid to their joints. Therefore, despite the persistent allusion to good environmental conditions inside the apartments (for example, cross-ventilation), the residents suffered from excessive heat and cold, as well as rainwater leaking into their units. The hasty paint job soon looked worn-out, the concrete surfaces were smeared with water leaks, the unmaintained communal spaces—the interminable corridors and stairways—became laden with dirt, and the broken glass on the windows of the communal areas were not replaced. Without exception, these buildings acquired the appearance of slums.[77]

The transformations in the approach to housing Algerians that occurred between the centennial and the end of French rule reflected a multitude of fluctuating social, cultural, political, and economic factors, but overlooked certain key changes that took place in Algerian society during the three decades of intense construction activity. Perhaps the most important among them was the impact of the Algerian War, which began to redefine the status of women and gave them an unprecedented

Figure 99.

(above) Marcel Lathuillière and Nicholas Di Martino, Cité Haouch Oulid Adda, plan of unit, 1959.

(1) living room, (2) bedroom, (3) water closet, (4) kitchen, (5) entry, (6) loggia, (7) public hallway.

Figure 100.

(below) Lathuillière and Di Martino, Cité Haouche Oulid Adda, view, 1959.

visibility in the public realm.[78]El Moudjahid argued at the time that women's roles had shifted from "knitting for soldiers and weeping for them" at home to active combat in the underground resistance, with the potential for imprisonment, torture, and death.[79] The multiple tasks women assumed during the war had broadened the sphere of their activities and the boundaries of their relations.[80] Furthermore, in the absence of men, women were obliged to carry out all the business activities outside the home. Consequently, it became common to see many women in government offices, shops, streets, and squares.[81] Even more significantly, they expressed their willing participation in the resistance by taking part in demonstrations against colonial rule and thus occupying the public spaces of the city.[82]