Blackmail (1929)

In the even more interesting Blackmail , patriarchal culture is indicted with the exposure of its intentional suppression of the woman's voice. Although it was made seventeen years before the other films discussed in this chapter, Blackmail provides an illuminating second "take" on the traumatized, silent woman. The dis-synchronization of the female character's image and voice

and her problematic relation to language are the central issues of nearly every scene in Hitchcock's first sound film.

The most striking manifestation of the heroine's visual/aural fragmentation lies in the dubbing of the lead character, Alice White, marking the material conditions of post-sync sound in the transitional period as crucial to the issue of the representation of the woman. The decision to dub the central female character was made by Hitchcock and the British producers. Anny Ondra, a silent film star in England, had a heavy Czech accent. Dubbing was a common solution in the earliest days of sound for studios and producers whose success in the years prior to sound had depended to a great extent on foreign actors. Although audiences knew these players were foreign (a great deal of publicity having established this as part of their "other-worldly" personas), in silent films an actress like Ondra was free to play either a foreign princess or the girl next door. In sound films, accents locked such stars into "exotic" roles at a time when vamps and sheiks were distinctly out of fashion. The desire to hear everyday speech, slang, and the vernacular created new stars in America and was felt in England as well. "Hear our Mother Tongue as it should be Spoken," a British poster for Blackmail proclaims (Barr 1983). Consequently a "woman," in effect, was constructed according to the production team's idea of what a woman should be—half agreeable appearance, half acceptable accent. The desire to dub Ondra was therefore in response to a cultural/realist demand ("local English girls don't talk like that") and the subsequent economic demand (the public wouldn't "buy" a Czech "posing" as a Chelsea shopgirl).

The technical limitations of the day made accurate lip-syncing virtually impossible. While Ondra mouthed the words, a second actress, Joan Barrie, spoke the dialogue offscreen. The failure of synchronization between lips and words makes a present-day audience constantly aware of the process of synchronization, taken for granted in every other sound film and ostensibly the "talkie's" reason for being.

The dubbing of Alice is a literal example of what Rick Altman calls sound cinema's ventriloquism. In arguing against the alleged "redundancy" of sound and image, Altman states that the two have a "complementary relationship whereby sound uses the image to mask its own actions" and vice versa. "Far from undermining each other, . . . each track serves as mirror for the other. . . . the two are locked in a dialectic where each is alternately master and slave to the other." Through this illusion of wholeness, untained by the "scandal" of a mechanical source, the "myth of cinema's unity—and thus that of the spectator" is perpetuated (Altman 1980b, p. 79).

The failure of synchronization fragments the unified subject created by successful synchronization by revealing the material heterogeneity underlying the sound film. It exposes "Alice," the character with whom the audience would usually identify, as a (re)production, a composite made up from several

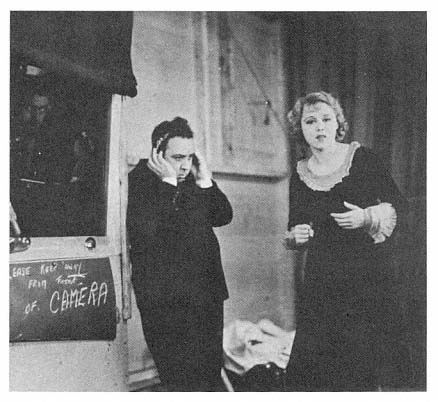

Alfred Hitchcock with Anny Ondra on the set of Blackmail

sources. Because the convention of synchronization is designed to make lip-syncing seem "natural" and easy, the actress's painfully apparent exertions to say one word "right," in perfect sync, break down illusions of smoothness, as well as interfering with spectator identification. The spectator is denied the specular and auditory pleasure realized in simply watching an image appear to "speak." In being dubbed—and badly at that—Alice becomes a voiceless Echo, betraying the inadequacy of the image, its nature as shadow, and the vague threat of a voice that is not fixed, not fully secured to the narrativized image.

It is difficult to say whether audiences in 1929 were as intolerant of lapses in synchronization as contemporary audiences. Accepting that "meanings are not fixed and limited for all time within a text," and that "it is likely that they will be read in different ways at different times and places" (Kuhn 1982, p. 94), and rather than try to recapture whatever phenomenological impact Blackmail might have had upon its audience in 1929, the following analysis is

an attempt to read the film according to contemporary issues: the ways in which woman is positioned by cinematic processes of signification, and the function of the sound track in this process.

Although 1929 was rather late for a "first" sound film, the delay enabled Hitchcock to produce an advanced meditation on the possible uses of sound. The text incorporates silent footage (lifted whole from the original silent version, made immediately prior to the sound version), which allows for a series of comparisons/contrasts between sound and silents/silence. The conceit of this early sound film is an attempt to keep a man silent (paying off a blackmailer). The heroine spends over a third of the film virtually speechless. When she finally speaks, her boyfriend urges her to keep quiet. The dialogue is laughably banal, yet the right word can cut like a knife. The opening scene, an exciting silent chase, is immediately contrasted with a poorly dubbed, confusingly cut dialogue scene that seems as if it will never end. But before we glibly assume silents were "better" movies, sound becomes a moral force, while silence is linked with corruption and moral lassitude.

The text's position on "sound plus image" versus "image alone" is carefully paralleled with the depiction of Alice. Thematically, she veers from one extreme to the other. She is introduced as a chatterbox. After a violent assault, she becomes almost catatonic. Finally, she accepts speech as a moral imperative, achieving maturity and the audience's respect before slipping back under patriarchal control and enforced silence. Alice White becomes Hitchcock's personification of the course the sound film must take.

After the opening scene, detailing an arrest, Frank, a Scotland Yard detective, meets his girlfriend, Alice, back at the station. Totally caught up in his work, Frank explains why he's late by telling Alice that the great (male) machinery of the Yard cannot be rushed for a woman. As they walk outside, Alice begins to giggle. Frank asks what she is thinking about, but she keeps it to herself. In another context, Mary Ann Doane describes the result of such a construction: "The voice displays what is inaccessible to the image, what exceeds the visible: the 'inner life' of the character" (in Weis and Belton 1985, p. 168). Already the sound marks Alice's voice as the signifier of an inner woman inaccessible to Frank.

At dinner, Alice is again dissatisfied with Frank. His idea of a good time is to see a movie about Scotland Yard, called Fingerprints . (Fingerprints, incidentally, like the silent film image, are visually perceptible physical imprints, whose alleged ability to indicate guilt or innocence would prove totally inadequate in the case we are about to see.) An artist, on the other hand, has sent her a note saying that he is waiting to see her . While Frank is clearly the force of order (safe, secure, predictable), the artist attracts Alice with a bohemian quality that suggests he is outside Victorian expectations and constraints. Yet Alice has trouble deciding. Verbally, all she does is equivocate. Frank, exasperated, walks out (making her choice for her), and she leaves with the artist.

In his apartment, the artist seems unhurried, kind, and enjoys Alice's company. However, this scene is gradually revealed as a series of subtly graded attempts by the male character to control both the female's image and her speech. Alice draws a face that could be either male or female. The artist, controlling her hand, adds a sexy female body. Alice toys with the idea of putting on a fancy dress and asks if it will fit. She may sound a little silly, but she clearly feels free to try new things. He urges her to try on the dress while he plays the piano. Hitchcock indulges/accuses his/our voyeurism as she undresses behind a black screen but remains visible to the camera. This creates a split-screen effect. Alice looks like an idea in the artist's mind, a projection of white on black, a silent image to his "all-singing, all-talking" one. He sings a song about the twenties' "wild youth" ("There's no harm in you, Miss of Today") and when Alice steps out, he informs her, "That's you," defining her in the lyrics of the song. While Alice takes dressing up as part of her adventure, one of the possibilities opening up to her, the artist uses it as an excuse to kiss her, implying that her willingness to experiment with her image shows that she has in fact agreed to accept the image he has given her. The kiss upsets Alice, and she wants to leave, but the artist dominates her further by witholding her dress. Finally, he physically drags her out of the frame despite her reluctance. He terms her objections "silly."

The series of uninterrupted, static long takes in the scene leading up to the rape give Alice's exchanges with the artist an unstructured quality noticeably absent from the stilted restaurant scene with Frank. The limited camera movement in contrast to the acoustic "opening up" (the use of music and verbal wit) allows the characters constantly to experiment with their positions, increasing the sense of freedom. Alice's being forced by modesty to retreat behind a screen to change her dress underscores the psychological progression of the scene by indicating to us that she isn't as free as she thinks she is and that the open apartment could become a trap.

Charles Barr compares this scene with its counterpart in the silent version of Blackmail (apparently released only in Britain). The silent version of the scene in the artist's studio has eight shots and two titles, both of the artist addressing Alice: "Alice" and "I've got it" (when she is looking for her dress). As Barr describes it, "The silent sequence, then, is based on montage, reverse-field cutting and mobility of the camera and viewpoint; the sound sequence has none of these." He disagrees with "Rotha's 1929 verdict that the silent version was infinitely better by virtue of 'the action having its proper freedom.'" Barr argues that as "post-Bazin era" spectators, "we have more 'freedom' watching the sound sequence" (Barr 1983, p. 124). While the spectator/auditor's "freedom" is, of course, constrained in both versions, the sound version offers a greater potential ambiguity in attributing psychological motivation to the two characters.

The series of shot / reverse shot alternations reproduced in the stills accompanying Barr's article resemble classic melodrama, intimating an impend-

ing "fate worse than death." This construction is so much a part of the "damsel in distress" silent film that the next shot could well reveal Frank and the Mounties riding to the rescue. The use of the long take in the sound version, with Alice unwittingly trapped in a large empty set that invites her to feel free, and where any choice she makes is ultimately revealed as having been the wrong choice, is finally more claustrophobic and threatening than the looming close-ups of a sinister Cyril Ritchard as the artist cut opposite high angle shots of a cowering Alice. The sound version is a more subtle achievement, with the bright and inviting apartment of the easy-going artist changing imperceptibly into a suffocating enclosure.

Up to this point, Alice's words have had little individual impact. Her dialogue has consisted of clichés, slang phrases, and expressions of indecisiveness indicating that she doesn't know her own mind. Ironically, when she definitely says "No," it is discounted. The futility of her discourse, her attempt to establish an independent identity in the face of male domination is now forcefully introduced. By cutting to a static long shot of a draped bed, Hitchcock eliminates the image's ability to tell us simple facts of plot or action. The only movement is Alice's hand, fingers flexing against the air, literally unable to come to grips with the assault taking place.

With the visual obstruction of the action, the spectator must rely on the sound track for information. Alice screams, "No! Let me go!" over and over, her voice the only instrument that keeps her from being absorbed into the oblivion represented by her invisibility. However, her words are ignored; her attacker doesn't listen; the policeman outside is oblivious; Hitchcock doesn't spare her. Alice is forced either to allow herself to be victimized or else resort to violence. The music is suddenly brought in at full volume as Hitchcock returns action to the image with a cut to a close-up of Alice's hand finding the knife that will free her.

The trauma that occurs in this scene and that must be worked through for the rest of the film is the separation of image-track and sound track. Alice is stratified; she becomes a silent image or (as in the rape scene) a disembodied voice. The question the film raises is whether or not it is possible to reunite image and voice, the very question film itself was facing in the early sound era. As long as Alice occupies the two irreconcilable extremes—silence and screaming—she remains powerless. The question dramatically posed by the rest of the narrative ("When will she speak?") implies the text's resolution of her verbal impotence/catatonia: mature speech unified with her image. However, as we shall see, the wholeness and potency associated with the synchronization of image and voice are ultimately denied to Alice, who cannot bring herself to speak at the right time and whose voice is (literally) never her own.

The power of words, when wielded by others, is imposed on Alice at breakfast the next morning, when she is presumably in the bosom of her family. As Alice sits down, a local gossip relates in gory detail the horrible "mur-

der" that has occurred. The near-monologue fades to a murmur while the word "knife" is amplified, sharpened. The blurring/accenting functions as audio "point of view," a famous use of subjective sound.

The manipulation of the sound track is augmented by the use of standard point-of-view construction in an alternation of shots of Alice staring avidly before her and close-ups of a breadknife. The combination of image and sound track develops a clear, even overemphasized, depiction of Alice's psychological state and of the relationship between knives and her efforts at control. She used the first knife to regain control of her environment and stop the attack; here, she unconsciously tries to deny she ever had control of the original knife by suddenly flinging the breadknife to the floor. Sound functions here as the representation of moral consciousness, reflecting on and deepening the meaning of the earlier action/image.

At this point in a classical Hollywood film, the hero would enter and take over—speaking for the heroine, protecting her, explaining situations, devising scenarios, and verbally controlling the world for both of them. However, Hitchcock insists on Alice's discourse. Although she is often speechless, instead of turning to the detective to relate the "truth" and take charge, Hitchcock makes us wait for Alice. Frank has been assigned to investigate the "murder" of the artist. He finds Alice's glove at the scene and goes to ask her what it means. As Frank impatiently waits, Alice (center of the frame) plays with her sweater, looks away and shakes her head. No music fills the space. We are left with a silence that is consequently all the more uncomfortable for character and audience.

Thus the dramatic structure of the film has been transformed. The suspense now rests entirely on Alice's asserting her version of events, her discourse, the truth. This is the need established in the audience, which must now be satisfied. Instead of wondering, "Who done it?" we ask, "When will she speak?"

But Alice finds it extremely difficult to speak except in the near-nonsensical utterances of a young lady at tea. A blackmailer who had seen Alice and the artist together outside the artist's apartment arrives and tries to blackmail Alice and Frank. Attracting the attention of Alice's parents, he brazenly invites himself to breakfast. With all eyes on her, all Alice can manage to blurt out after the fact is "Would you stay for breakfast?"—clearly inadequate to the tense situation, but for the moment all she can handle.

Kaplan points out the inadequacy of language to express crises common to the lives of women. The character Norah in Fritz Lang's The Blue Gardenia is in a situation similar to Alice's: an attempted date-rape resulting in the woman's seemingly killing the man in self-defense.

Norah's inability to "remember" or to say what actually happened represents the common experience of women in patriarchy—that of feeling unable to reason well because the terms in which the culture thinks are male and alien.

Women in patriarchy do not function competently at the level of external public articulation and thus may appear "stupid" and "uncertain."

(Kaplan 1978b, p. 85; italics added)

This encapsulates Alice's position as well, and might account for some of the hostile reactions to her character in writing on Blackmail .[3]

Just as the artist would not concede Alice control of her image or validity to her speech, Frank also tries to suppress her. Far from helping Alice overcome her fear of speech, when she succeeds in getting out a word, Frank snaps, "Don't interfere." It's her life, but it's his job, which from the beginning has taken precedence over Alice. Visually, Frank and the blackmailer work together, surrounding Alice or forcing her to the edges of the frame. Dramatically, the men are engaged in an effort to keep Alice's actions secret.

Where the standard film detective's goal is to find and thus establish for us the "truth," here Frank knows the truth. His job has become to suppress it in deference to a greater goal—the Victorian patriarchal control of women's sexuality. In this case, it is preserving the illusion of control while ushering Alice back into the fold that counts. After all, what Frank is protecting Alice (and society) from is the public admission that she chose her own male companion and assumed the authority to say whether or not she would have sex.

Formally, the respective moral sensitivities of Frank and Alice are linked to cinema. Codes of silent and sound film are made to interrogate each other, each representing the two characters who are at odds with each other, Frank and Alice. While it might seem that Frank, earlier so dedicated to the Yard and police procedure, would have scruples about hiding evidence, Hitchcock (never a fan of the police) reveals that he has surprisingly few hesitations. To keep things quiet, Frank considers paying blackmail. He finds it more appealing to frame an innocent man than to seek justice. Frank's job is redefined; he is not supposed to find the truly guilty but to maintain law and order, the status quo, appearances. Caught in his failure to control Alice, Frank simplifies the situation. He accuses the ex-convict blackmailer of the "murder." Forced to run, the man dies in the chase.

Police procedure is characterized throughout the film as a silent film chase. The pursuit of the wrongly accused man refers us back to the opening scene, which used the same set of silent film conventions. Through the comparison we can now recognize the lack of moral thoroughness that results when action (visual only) proceeds without verbal (moral) qualifiers; the power of force is celebrated over the power of reflection, appearances over truth. In the opening scene, the police push their way into the room of a man who looks typically "criminal" (unshaven, surly). Suspenseful music reminiscent of that in silent film melodramas is laid over the visuals, while ambient sounds and speech are removed. When the man is arrested, however, his neighbors object and crowd around the police. Who is this man? What is the charge? What do we the audi-

ence know about him except the stereotype of the silent film thug? The image shows us the surface, but we never do find out the purpose or justness of the arrest. The haste to judge on the basis of appearances foreshadows the end of the film's second chase. The wrong man dies in a mindless, impurely motivated chase, persecuted by the police because it is convenient for the police. They pursue the matter no further. Once the action has been carried out, they wash up and go home (as in the first scene).

The framing of the blackmailer is the dilemma that forces Alice to break her silence. The chase is intercut with Alice sitting at a table, troubled by her conscience. She writes a note, refusing to participate through her silence in what amounts to a lynching. She writes that she must "speak up" to save "this poor man." However the crosscutting reveals that her efforts are too little and too late. As the blackmailer is about to shout the true identity of the killer, he falls to his death.

Alice arrives at the police station ready to speak. The station is a male cloister, where a woman must apply to the doorman in writing (!) for admission. The sergeant, who recognizes Alice as Frank's girl, laughs at the thought of a young lady knowing anything about a "murder." Alice is led to the chief inspector's office. Frank arrives to "rescue" her by preventing her from carrying out her plan. As she struggles to choose the right words, Frank interrupts to tell the chief that what she has to say can't be important. The chief interrupts her by taking a call in the middle of her statement.

The dialogue warns us that Alice is doomed to fail. She is still unable to finish a sentence. She stutters, repeats herself, announces that she is about to say something and generally prevaricates. The space between sound and image remains a chasm. She has not been able to unite image and voice. On the contrary, if Alice wants to keep her "good" image, she has to keep silent and let Frank usher her out of the room. Where Frank, the chief, and the sergeant take it for granted that speaking moves straightforwardly along pre-set male-controlled channels of meaning, Alice is completely incapable of making the words serve or even accord with her intentions when she is called to account for herself to the male head of the law. Her attempt to speak has failed and she is hustled away.

Out in the hall, Alice breaks down and tells Frank her actions were in self-defense, but what she says clearly does not matter. Out of convenience, the forces of law and order have blamed a dead man. Frank has returned Alice to her constrained place within patriarchy. She has been forced to submit herself to the judgment of the police, to "confess" her "crime," and her confession has been totally contained by the system. Alice's story is dismissed (the real truth) and she is turned over, in effect, to Frank's custody.

Standing between Frank and the sergeant, Alice is literally surrounded by the police. "Next they'll be having lady inspectors," the sergeant jokes. Alice

joins in the laughter. She is back in line and won't step out again. Another policeman takes the artist's painting of a clown to be filed away. The leering, pointing clown reminds Alice to look at herself. She stops laughing.

In Blackmail , maturity comes at the cost of innocence. Alice resumes her place in patriarchy, but has to acknowledge that she is neither innocent nor free. Frank succeeds in containing Alice, but is forced to compromise his duty and any idealism in favor of maintaining appearances. Frank and Alice are painfully aware of the price of socialization. The recognition of the workings of patriarchy and language precludes a romantically happy ending. Alice and Frank are fragmented and must confront that what society holds they should be is actually very far from what they are. The end only increases their disintegration. Their images are false and they are struck dumb.[4]