8

Looking to the South

Many Americas

It is strange, some think, that peoples of the Americas tend to look east and west rather than north and south. About thirty years ago, when we first began to look for books from and about Latin America, this was plainly true; perhaps it still is. Often enough we have criticized ourselves for paying more attention to Europe and Asia than to the twenty or so countries to the south of us. But they too have looked to Europe for cultural ties, all the while complaining about the attitudes of their northern neighbor. Latin American intellectuals were, and still are, I believe, more at home in Paris than in any city north of them.

More at home in Paris, sometimes, than in each other's countries. And not always interested in each other. In Buenos Aires one day the lady manager of a large book store said to me, "We don't care about the Mexican revolution." That the memory of this remark remains with me so many years later shows that I must have been shocked—shocked perhaps into realizing that, in a very real sense, there is no such thing as Latin America. There are a number of countries, not all alike. They don't speak the same language. Nearly half the people speak Portuguese, and the Spanish of the others is similar but not the same. In Santiago de Chile my Mexican friend burst into huge laughter on seeing a newspaper headline that read, "Cohete norteamericano se chingó." What the North American rocket did to itself was splendidly vulgar in one country but not, apparently, in the other. Some countries (Argentina, Chile) are predominantly European in

stock. Others (Peru, Bolivia) are largely Indian. Still others (Brazil, Mexico) are mestizo or mixed. But nearly five hundred years have passed since Cortés and the other conquistadores; the pervading culture is European, the sensibility Catholic, in spite of those intellectuals who would like to bring back Coatlicue and the Aztecs.

These are the impressionistic remarks of a nonexpert, a mere publisher, and are not to be taken as Truth, but perhaps they say something about our difficulties in understanding the other Americas, in distributing our books to them, in translating and publishing their literary and intellectual writings. When we ask God to bless America we mean the America north of the Rio Grande. When Mexicans write of nuestra América, that America is theirs, not ours, the one called New Spain for three hundred years. Included vaguely are the other Spanish American countries; along with the differences there is some sense of a common colonial origin, not like ours or Brazil's.

The several Latin American ventures, or adventures, of the Association of American University Presses came about almost accidentally; they had only grudging support from some member presses, notably those situated away from the Mexican border. At California the translation program—the larger part of our Latin American list in the sixties—was thrust upon us, willing as we were. In our university at that time there must have been more active scholars in this area—in the history, geography, anthropology, Spanish, and other departments—than in any other university. Without intention on our part, we at the Press found ourselves with the beginning of a Latin American list.

The old monograph series in History included a number of Latin American studies, and then in 1932 was founded the most distinguished of all the series outside the biological and geological sciences, Ibero-Americana. The first editors, led by Carl O. Sauer of geography, defined it as "a collection of studies in Latin American cultures, native and transplanted, pre-European, colonial, and modern . . . in the main, contributions to cultural history." By the end of the 1950s more than forty separate monographs had been issued, all but a few on Mexican topics. At first Sauer himself was the chief author, but the

series came to be dominated later by the writings of Woodrow Borah, Sherburne F. Cook, and Lesley Byrd Simpson, of the history, physiology, and Spanish departments. In 1960 a noted French scholar, writing in the Revue historique, dubbed these scholars, along with some others, the École de Berkeley, in part, I think, because their methods bore some resemblance to those of the Annales school. Much later, in the 1970s, some of the series papers, along with new ones of similar kind, were issued as books, both in cloth and in paper.

Meanwhile, we were publishing the books on Latin American literature of Arturo Torres-Rioseco, a Chilean long resident in Berkeley, and a little later those on Peruvian literature by Luis Monguió, a native of Tarragona on the Berkeley faculty. Quite a number of these were in Spanish and thus not suitable for wide promotion, but when we started the paperback list in the mid 1950s, we included Torres' Epic of Latin American Literature as well as several of Lesley Simpson's literary translations. The Poem of the Cid and the Celestina were Spanish, of course, but there was also Two Novels of Mexico by Mariano Azuela, better known perhaps for Los de Abajo, translated as The Underdogs and published elsewhere.

A number of scholarly books, perhaps a dozen of them, happened along in the forties and fifties, notably Sanford Mosk's Industrial Revolution in Mexico (1950). Our first real success in this area was Simpson's Many Mexicos, whose title I have paralleled in the subtitle of this chapter. A lively and irreverent interpretation of Mexican history and culture, the book was first published by Putnam in 1941 and reissued by us in a third edition in 1952. Not often is it wise to take over books abandoned by commercial firms, but this time we were fortunate. Or, as Harlan Kessel would say, we did a better job of selling a good book. And it was Kessel, after he came to the Press, who did the most for it. In 1966 he planned and promoted a silver anniversary edition, with revisions, that had considerable success. Since the book still sells, the anniversary might now be golden.

So we had the beginnings of a list, but neither I nor anyone else thought of it as such. As for me, I had a tourist's interest in Mexico

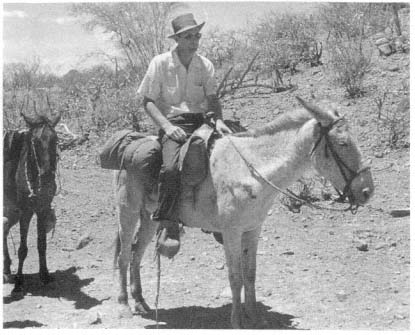

How we went to San Javier, 1951. Photo by Neal Harlow.

and no thoughts about the continent to the south. In 1951, with Neal Harlow of the UCLA library, I drove an old military jeep the length of Baja California at a time when there was no paved road, only dirt tracks that branched off in various directions and, when we were lucky, came back together again. There were no service stations and only one ratty hotel between Ensenada and La Paz, nearly one thousand miles, but every farm on the way sold gasoline and beer. Gasoline was filtered through felt hats, the beer through us. One could stay in private houses if one knew where to ask. In Ensenada, by good fortune, we met a woman who had sisters in San Ignacio, Loreto, La Paz, and perhaps places I forget; we stayed with all of them, talking as best we could around the kitchen table, dictionary in hand. From Loreto we had to ride mules to reach Padre Ugarte's stone mission of San Javier, perhaps the finest in the two Californias. At Cabo San Lucas, at the end of the peninsula, where now there are at least six

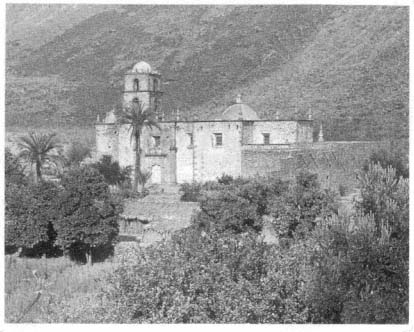

Mission San Javier Viggé.

big hotels, a marina, and a tourist town, there existed then only a fish cannery and one beer joint. We slept on the sand under the very last rocks.

Two or three years after that, the painter Rico Lebrun (to be mentioned later as an author) and his wife Constance were spending the year in San Miguel de Allende, in the Bajío region north of Mexico City, and asked me to visit them. Leaving from New Orleans after a meeting, I was told I could go by way of Mérida or by way of Houston. Not that fond of Texas, I chose Yucatán and spent a couple of days at the great Mayan ruins of Chichén Itzá before going on to Mexico City. Only passenger on a small bus to San Miguel, I sat with the driver, dictionary on my knee.

In Mexico I made the first of our many calls at Fondo de Cultura Económica, perhaps the most intellectual publishing house south of the border, where we had a piece of business, now forgotten. Formed originally to bring out translations of books on economic matters,

Fondo had branched out into many fields and was selling its books all over Latin America. It was, I think, what is known as a sociedad mixta , a kind of mixed corporation peculiar to Spanish America, which could make use of both government and private money and could avoid the bureaucratic regulations that make state presses, here as well as there, so difficult to manage.

Such was my small experience of Latin America when things began to happen in the Association of American University Presses. In 1959 the annual meeting of the AAUP was held in Austin, and Frank Wardlaw, director of the press at Texas, talked us into holding a second session in Mexico City as guests of the National University there. A converted South Carolinian, Frank had become more Texan than a Texan, if that can be done, was building up a fine list of regional books, and always conscious of the border near by, was beating the drums for closer relations with Latin America. So about one hundred of us boarded a Mexican train in Laredo, survived a slow-down strike and a shortage of beer, and gathered with our Mexican colleagues the next morning.

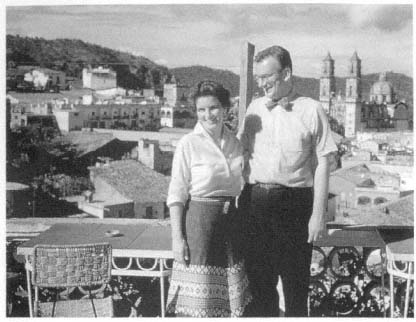

Two things I remember about that meeting. One, through a large window looking south we could see the great volcanoes, Popo and Ixta, as their long names can be shortened. And two, since that was my second year as president of the AAUP, I had to respond to the speech of welcome. With some coaching I managed to read out a short talk in Spanish—with only one mistake, I was told by Jack Harrison of the Rockefeller Foundation. My mind retains little else of the meeting itself, but holds the memory of our driving with Harrison through the midnight streets of Mexico in search of band music, and over the hill to Taxco next day.

Berkeley graduate and friend of Ibero-Americana authors Borah, Simpson, and Jim Parsons, Jack Harrison, more than anyone else, brought about the events of this chapter. It was he who proposed me for the trip to South America; he was inventor of the Latin American translation program and sponsor of it through the foundation. With the third Latin American endeavor, the distribution office in Mexico (CILA), he had less to do. All three ventures are now things of

Jack and Barbara Harrison in Taxco, 1959.

the past, but the translation program resulted in many books of lasting value.

An organization optimistically called CHEAR (Council on Higher Education in the American Republics), with Ford Foundation money in hand, wanted to learn something about university and other scholarly publishing in the Latin American countries. So in the summer and fall of 1961 they sent two of us, one Mexican and one North American, on a survey trip around South America. We both traded our first-class tickets for coach tickets and took our wives along. Susan and I, before starting out, did what we could for our Spanish by attending Berlitz classes in San Francisco. With her superior ear she progressed faster than I with the spoken language. I could always read well enough.

My colleague was Carlos Bosch García, who taught history at UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) and was also distribution manager of the Editorial Universitaria, the press there. Like many intellectuals in Mexico, where university salaries were low,

he needed two jobs, morning and afternoon, to support himself. Some of our friends took on evening jobs as well. Carlos' wife, Elisa Vargas Lugo, having written a monograph on the church of Santa Prisca at Taxco, was soon to become professor of art history. While she was Mexican-born, Carlos was a Catalonian from Barcelona, son of the rector of the university there, who at the end of the civil war had fled from Franco and eventually settled in Mexico. Carlos, by good fortune and good education, had some facility in five languages, four of which I heard him use in our interviews. The fifth, of course, was Catalán, which Carlos claimed as his first language. In Barcelona, said he, we learn Spanish at Berlitz.

Languages can be tricky, especially when they have many words in common. We all know about the faux amis , French words that look like English ones but differ in meaning. Carlos tells of a time when, as a very young man unsure of himself, he went to a dance across the French border. Dancing with a French woman, he stumbled and stepped on her feet, causing some pain. At this point one must remind the listener that the Spanish word meaning to tread on or step on is pisar , while the French word happens to be rather different, piétiner . Confused and contrite, Carlos could only accuse himself. "Ah, Madame," said he, "je vous ai pissé sur les pieds." Whether this truly happened to him or whether it is a standard Barcelona story, I do not know.

We began in Mexico with an automobile trip to the Universidad Veracruzana in Jalapa, five thousand feet up and foggy, the old colonial town that was once the first goal of incoming Spaniards, anxious to escape the malarial coast of Vera Cruz. To my surprise we found a young and enterprising university press, one of the most attractive in Latin America, publishers of original literature and of works about the archaeological findings of the region, including the caras sonrientes , the smiling faces, quite unlike anything Aztec or Toltec. After that little side trip, Susan and I went alone to Guatemala and Costa Rica, and then the four of us set off for Brazil and around the southern continent, traveling sometimes together and sometimes separately.

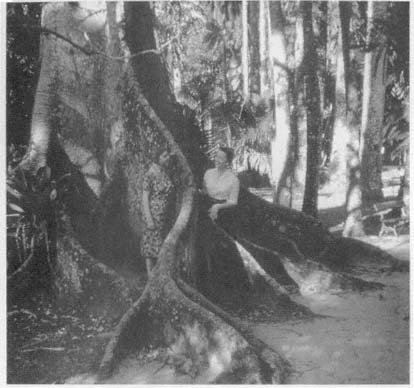

In Brazil we were accompanied by Helen Caldwell, who taught

Helen Caldwell in Brazil, 1961. With Susan Frugé.

Latin at UCLA but whose chief research interest was the novels of J. M. Machado de Assis, thought by many to be the finest fiction writer of all Latin America and the only one before Jorge Luis Borges to bear comparison with the best European writers. Along with Bill Grossman of New York University, Helen had been responsible for making Assis known in this country. Epitaph of a Small Winner , Grossman's version of Memórias posthumas de Braz Cubas , appeared in 1952 and Helen's translation of Dom Casmurro the following year, both published by Noonday Press. In 1960, shortly before this trip, California brought out Helen's book about Dom Casmurro , and in the years thereafter a biographical study of the writer and several more translated novels, as well as a volume of stories that she did together with Grossman.

Basilica of Bon Fim.

I get ahead of myself once more but would like to record that Helen Caldwell, who had never before been to Rio de Janeiro but knew the streets from her studies, led Susan and me through the old districts where Machado de Assis had lived and worked in the century before. And in Salvador da Bahia, the old northeastern capital city, the three of us got caught up in a popular religious procession, hundreds of people who had walked and sung from the basilica of Bon Fim in the outskirts, five miles away. They filled the narrow street from wall to wall and swept us along, with Helen singing "Ave María" at the top of her voice and muttering under her breath, "And I come from five generations of atheists."

In Brazil, I had thought, all educated people would speak Spanish as well as Portuguese. But none of them did, we found, not a one that we met. They would understand Spanish, more or less, reply in Portuguese, and as the conversation proceeded each speaker would adapt a few words, pronounce a little in the direction of the other until they were conversing in a tongue never known to man. Unknown to me, at least, but Carlos had a name for it, españolete , I think. It was a wonder to hear but too much for my fragile Spanish, which fell to the ground and shattered, never put together again until we reached the next country. Some in the offices where we went spoke

English, but at a university gathering in São Paulo one man insisted on German and another would speak only French. Carlos handled it all, and to me anything was better than the spontaneous hybrid. Brazil, we thought, was the most attractive of all the South American countries, but it was only later, when the Press was doing translations, that I came to appreciate the quality of written Portuguese.

Thereafter the language problem was less acute, or we became more adept at guessing or at making use of our Mexican friends. In Argentina we sometimes thought from a distance that people were speaking Italian, only to find closer up that it was Spanish with an unfamiliar intonation and some unexpected consonant sounds. Had there still been horses in the streets, we thought, one would have ridden a cabazho en la cazhe , with the double l , here transcribed as zh , pronounced like the z in azure or the g in my own surname. This, I was later told by my friend Luis Monguió, is an old Spanish pronunciation, abandoned in Spain and preserved in some parts of the new world. I have heard the name of the city of Medellín in Colombia pronounced in this way.

We visited universities at Rio, Bahia, Belo Horizonte, and São Paulo, in Brazil; at Buenos Aires and Córdoba in Argentina; and at Santiago de Chile, Lima, and Bogotá, and found them different from each other and quite different from our own. My information is out of date, perhaps, but in this memoir I must tell it as it was.

North American universities are descended through Oxford and Cambridge from the University of Paris, which in the interpretation of Luis Alberto Sánchez, then rector of the University of San Marcos in Lima, was a university of maestros , while those of Spanish America were formed in the image of Salamanca, deriving from Bologna, a university of estudiantes .[1] Hence the Spanish American tradition of student participation in university government, broken in the nineteenth century but renewed in the twentieth after a reform movement that began in Córdoba in 1918.

[1] "The University in Latin America: Part 1, The Colonial Period," American , November 1961, pp. 21–23.

In Brazil no universities existed in the colonial period; advanced students went to Europe. The first universities were founded in the twentieth century by combining the several schools and institutes that existed in each city. In Spanish America, too, universities tended to be loose federations of faculties or schools; power was more decentralized than with us, and the chief officer, the rector, had relatively little control over the several parts of his institution. Schools of law and medicine were often quite powerful, and sometimes the facultad de filosofía (humanities) thought of itself as the true university. There were a few exceptions of course, but usually the rector was elected by students and faculty for a term of four, five, or six years, and some professors were also elected. The political climate, then, was quite different from ours, more chaotic and subject to frequent change. Later in the sixties, listening to the agitation for student power in Berkeley, I recalled the South American universities and thought that reforms could move backwards as well as forwards.

It was also true that research, both organized and individual, was far less central to Latin American universities than to ours. They never experienced the remodeling on European lines that took place in this country in the second half of the nineteenth century, and, for better or worse, missed the great flowering of scholarly writing and publishing that took place here. Historical and literary writing has flourished, and at that time there began to appear works in economics and other social sciences, but these were not many.

In all South America we found only one university press—in the University of Chile—that operated on lines familiar to us. Most worked in the old print-and-exchange system, printing occasional books from the several faculties, some of them collected articles or speeches. One press, EUDEBA at the University of Buenos Aires, had gone to the opposite extreme. Operating as a sociedad mixta , it brought out small popular books, selling them from kiosks on street corners. Whether they have survived the political upheavals since then, I do not know. In Mexico I have already mentioned the Universidad Veracruzana. The University of Mexico itself had a large press, with an organization partway between the old and the new

styles; they had their own printing plant and were publishing about one hundred books a year and distributing them with some success, partly by barter with other universities, a practice strange to us but evidently workable for them.

A number of university officers, we found, anticipated that a foundation might help them buy new printing equipment, but we judged, rightly I think, that the greatest need in Latin American university publishing was for better distribution, particularly from one country to another but also within the countries of origin, and we recommended that, if CHEAR and the foundations wished to do something to improve matters, they might concentrate on that aspect and perhaps set up a number of distribution centers in major capitals. A committee of the AAUP, after spending some time in Mexico, made a similar recommendation.

I have sometimes wondered whether those who are asked to study problems do not feel a compulsion, internal or external, to recommend large cures. It might often be sensible to write in a final report: Yes, the problem is serious; something should be done about it, we suppose, but a move for change is apt to encounter difficulties one cannot foresee; large measures may bring small results, and perhaps it will be best not to attempt too much.

A notable example occurred in the 1970s, when there was a widespread belief that the whole system of scholarly communication in this country—writing, book publishing, journals, research libraries—was in trouble, trouble too various to be spelled out here. A group of scholars, publishers, and librarians spent three years on the problems and came up with a number of individual studies, the most useful being perhaps one by Datus Smith on the foreign distribution of university books. But no large solution was in sight, it seemed, and perhaps should not have been looked for. At the eleventh hour, with three years of work to justify, the board of governors voted to recommend a great new central library system, parallel to the Library of Congress; this, it was hoped, might make (expensive) sense of the entire system of scholarly communication. Fortunately, the plan was never implemented. It is mentioned here merely to illustrate the men-

tal set that leads investigators to propose whole new structures when it might be more feasible to whittle away at the edge of the old ones.[2]

It is possible that in the 1960s we fell into a trap not so different from that one. Diagnosing the problem correctly, we felt that an interested foundation might do something useful. The difficulties were clear enough; how intransigent they might be was less clear. And for reasons that now escape me the two foundations, Ford and Rockefeller, decided to fund only one distribution center, in one capital, Mexico City, hoping it might do something to improve the movement of scholarly books throughout the hemisphere. Mexico was the obvious choice, close to us and of greater interest than others, but not a choice that was understandable, or useful, to book people in Buenos Aires, for example. The plan may have been too small rather than too large. Or both too small and too large. It succeeded in part, and for a time, and in one direction more than in the other.

This is not the place for an account of the Centro Interamericano de Libros Académicos (CILA), but it was one of our major Latin American endeavors and may be worth a comment or two. The Centro was opened in 1965 in modest quarters in a good location on the Avenida Sulliván, with a handsome display of North American and Mexican books along with a handful from South America. A board of directors was appointed: three from the United States, appointed by the AAUP; three from Mexico, appointed by the rector of the National University; and three from South America, chosen in a way I forget. To the best of my recollection, only one South American ever attended—José Honorio Rodriguez of Rio de Janeiro, author of a book that California translated and published, entitled Brazil and Africa .

The Mexicans gave us a distinguished group: Jaime García Terrés, who shortly thereafter became ambassador to Greece, where Susan and I later called on him; Manuel Alcalá, then head of the national library and later ambassador to UNESCO; and Rubén Bonifaz Nuño,

[2] See my "Two Cheers for the National Enquiry: A Partial Dissent," Scholarly Publishing (Toronto), April 1979, pp. 211–18.

The original CILA group: Chester Kerr, Frank Wardlaw, Carlos Bosch García,

August Frugé, and Rubén Bonifaz Nuño; Mexico, 1963.

head of the press at Mexico and for a long time the second in command at the university. García Terrés and Bonifaz Nuño were also, and still are, distinguished poets, and the latter has published translations into Spanish of Pindar, Ovid, and other classical authors. He served as chairman of the CILA board for nearly the entire time. Understanding English quite well, Rubén would never try to speak it, and Carlos Bosch sat next to him and translated what he had to say. And because his appearance seemed to fit the part—black hair, dark three-piece suit, necktie with stick-pin, huge ring on his finger—we always called Rubén, to his great delight, the Riverboat Gambler. Retired now, he continues to write books and is one of my faithful correspondents.

We North Americans could not expect to match such distinction but tried to balance it, as best we could, with knowledge of scholarly publishing. Our first group was Frank Wardlaw of Texas, Chester Kerr of Yale, and I from California. Serving thereafter were Jack

Schulman of Cambridge, Willard Lockwood of Wesleyan, Bill Becker of Princeton, and others. The executive secretaries of the AAUP, from Dana Pratt to Jack Putnam, served as secretary of the group. We met in Mexico two or three times a year and worked quite hard, going over the inventory, checking the accounts, visiting bookstores, calling on the American ambassador, for reasons I forget, and planning with the staff. Carlos Bosch García of Mexico was director, and Jonathan Rose of the United States, assistant director.

It was difficult, of course, to sell expensive hard-bound books, except for a few about Mexico, but some paperback editions, including our Many Mexicos by Lesley Simpson, were attractive to tourists and could be sold in quantity to bookstores. CILA did a good job of distributing in Mexico, but national boundaries proved even higher than expected and more encumbered with red tape; books crossed borders less easily than did people, legal or illegal. The staff made a trip or two to South America with results that hardly repaid the cost.

The greatest success came in selling Latin American books to university libraries in the United States. These latter, often unable even to learn what was available, were pleased to place standing orders for everything published in certain categories. South American organizations, not much on buying, were happy enough to sell. CILA bought, had the paper-covered volumes bound at Mexican prices, and resold north at a good profit.

After some retrenchment of the original plan, operating with one executive instead of two and putting the North American directors up at cheaper hotels, CILA managed to operate in the black for a number of years until Mexican inflation and rules of employment became too much to overcome. Whether the dozen or so years of effort had a lasting benefit, it is hard to say. Something was gained at the time.

And we, the North American directors, made many friends and came to feel at home in Mexico City. It was indeed a splendid place before being overwhelmed by too many people—a remark that might also be made about southern California. There was time to visit the university as well as the Colegio de México, an advanced school origi-

nally set up under the name of Casa de España to provide teaching posts for refugee scholars from Spain, and later Mexicanized. And there were peripheral activities, such as heckling Chester Kerr when he called a press conference to publicize a new Yale book entitled The Vinland Map purporting to prove that Norsemen reached America before Columbus. The map was a forgery, some of us claimed, and perhaps it was. And no one, we said, could interest Mexican journalists in a book written in English to discredit the discoveries of an Italian who had sailed for Spain. But Chester proved to be a press agent of genius, and was given polite attention, more than the book received, I think, from Italian groups in New York.

We also called on Fondo de Cultura Económica, where I had first gone nearly fifteen years before and could now sell translation rights into Spanish. The director at that time was a left-wing Argentine businessman named Arnaldo Orfila Reynal, who made a show of disliking things North American. At luncheons, when I went there alone, he liked to place me between two people who spoke no English and watch to see whether I could survive. On another occasion, when several of us arrived for a talk, Orfila dismissed his English-speaking secretary, while Chester Kerr grew red with anger. The incident is of no importance but shows the kind of attitude we sometimes encountered. Other Fondo officers were helpful, and several years later our friend Jaime García Terrés became director there, and always welcomed us.

We sought out authors when we could, and translators too, although most of the good ones translated into their native language and could more easily be found at home. One of the very best, however, was the American wife of a Mexican intellectual. Prompt, literate, knowledgeable, she also possessed a quick wit and a sharp tongue, and we may call her Melissa. She used to drive to the airport to meet two of my colleagues. More standoffish or less charming, I was not so privileged, but could say that she translated books for me and not for them.[3] The game was all quite innocent, of course, but at

[3] Later she did a book for one of them.

a later time something happened to the marriage, and her husband, whose nom de guerre can be Pablo, found himself an amie . The latter came from Austria, and Melissa was soon referring to her as Pablo's Tail from the Vienna Woods.

Preceding and paralleling the CILA venture was the translation program, a genuine success. The idea came from Jack Harrison of the Rockefeller Foundation. With his help Frank Wardlaw and I wrote the proposal, and in 1960 the foundation granted $225,000—worth much more than that sum is worth now—to the AAUP to help finance translations of literary and scholarly books from and about Latin America. Individual grants were made to pay translation and other manuscript costs in order that translated books might start out even with those written in English. Without this help, it was reasoned, the expense of translation had to be laid on top of all the usual expenses, making publication impossible unless the book promised a big sale or came as a labor of love from the translator. And big sales were not likely. Latin American books were notoriously more difficult to sell than those from France, Germany, and other European countries. Alfred Knopf, for example, made an effort to publish Latin American novels in the 1940s and 1950s; they sold only a few hundred copies each.

When he proposed the program to the chief officers of the foundation, Harrison remembers, they brought in Knopf to evaluate it; he recounted his own sorry experience and said there would never be an adequate market in this country. Harrison countered with the report that Frank Wardlaw at Texas had sold 20,000 copies of Platero and I , a work of poetic prose by the Andalusian poet Juan Ramón Jiménez, then living in Puerto Rico. In disbelief, Knopf checked the story, found that the sale had been even higher, and advised that Latin American books deserved another try.

The association appointed a committee of university scholars to receive proposals and approve individual grants. Thus at some presses, such as California, each project had to get over two hurdles, the home editorial board and the national committee. But in the next five years more than eighty books were approved, mostly in the humanities at

first, after that nearly half in the social sciences. About twenty presses participated, but the greatest number of projects came from Texas and California, the two presses most willing to do without manufacturing subventions. The translated books were a major part of the publishing program at Texas. At California, as part of a larger list, they were less central but quite important.

It is worth noting that nearly half the California books were from Brazilian Portuguese, and several were from French. The Brazilian books included Helen Caldwell's translations of Machado de Assis, but there were also economic studies by Celso Furtado and a number of historical and cultural works. It is difficult, I learned at this time, to be confident about originals in a language one does not read—read enough at least to get a feel for the nature of the work. The opinions of others are essential, of course, but one is still in the dark without some first-hand knowledge or impression. And so, to make myself feel better, I had to get hold of a Brazilian-Portuguese grammar and teach myself to read. The language, I found, was in some ways less like Spanish than it looked; the syntax, fortunately, was more like French. I began to share the enthusiasm of Helen Caldwell.

Friends told us about three exceptional books written in French and for some reason never put into English, perhaps simply because they were about Latin America. Most notable and first in period covered, was Robert Ricard's La conquête spirituelle du Mexique (1933), the story, says the translator, Lesley Simpson, of "the profound revolution in Mexican life brought about by the Mendicant friars." The author himself wrote, "In the religious domain, as in the others, the sixteenth century . . . was the period in which Mexico was created, and of which the rest of her history has been the almost inevitable development."

François Chevalier's Land and Society in Colonial Mexico: The Great Hacienda, published in 1963, concerns the Mexico of the great landed estates formed in the seventeenth century after the military and spiritual conquests had come to a halt. Like the Ricard, it is still in print in paper after all these years. So also is Latin America: Social Structures and Political Institutions by Jacques Lambert.

Out of the Homeric sixteenth century, as Lesley Simpson called it, came the Historia de la conquista de México by Francisco López de Gómara, published in Zaragoza in 1552 and translated as Cortés: The Life of the Conquerror, by His Secretary (1964). Suppressed by the Crown, perhaps on advice of Bartolomé de Las Casas, the great enemy of Cortés and Gómara, it survived outside Spain but has been neglected in modern times. Intellectual fashion in Mexico is to denigrate the Spanish conquerors, as Las Casas did, and to exalt the Indian component of the heritage. In English Gómara's book has been pushed into obscurity partly by the popularity of the contemporary chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Gómara, said Bernal Díaz, gave too much credit to the leader, Cortés, and not enough to the soldiers, or even to the horses, and he was not even there but wrote from a distance. But he was a great writer, as Simpson tells us, and seems to have had much of his information from Cortés himself. In English there was no modern or adequate edition of a chronicle parallel to, and equal to, the True History of Bernal Díaz, and we were pleased to publish it in Simpson's version.

Although most of our Spanish American books were Mexican, there was also Aldo Ferrer's The Argentine Economy (1966) and A Cultural History of Spanish America (1962) by Mariano Picón-Salas of Venezuela. Country Judge (1968), a novel by the Chilean writer Pedro Prado, was one of several literary works gathered in by the translation net. And because our paperback list was proving successful with poetry and other literary classics, as hard-cover editions were not, the translation impulse carried over to works not eligible for the AAUP grant, such as books by the Spanish poets Antonio Machado and Rafael Alberti, translated by the American poet, Ben Belitt.

Foundation interests change like any other fashion, sartorial or intellectual. When the Rockefeller money was exhausted after the allotted time of five or six years, the AAUP made strenuous efforts to obtain a second grant but was never successful. We no longer had Jack Harrison on the inside, he having gone first to Texas and then to Miami to head Latin American centers. And the enthusiasm of many presses was limited, they having less interest in Latin America

Jacket by Adrian Wilson.

than had Texas and California. They wanted manufacturing subsidies while we were usually content with funds for translation and illustrations. So the game came to an end, but not before we had made a considerable splash. A couple of decades later, a former student of Helen Caldwell, Joan Palevsky, established at the Press a fund to support literary translations. Although this was not limited to works from Latin America, I like to think, because of Helen, that there was some kind of relation between the two grants.

The Rockefeller grant, I think, and the six years of working on it, had a salutary effect on Latin American studies in this country. We—all of us—managed to bring into English, along with many current studies, most of the classics and standard works that had long been unavailable; they may now be assigned to students in survey courses where the foreign language is not required. Scholarly editors around the country became used to thinking about what is written in the countries to the south of us. And as for current literature, it is noticeable that new Latin American novels are now regularly translated and published by commercial firms, the same firms that could not make a go of such works a generation back. Although it may be that current writings, including those in the "magic realism" genre, are more to North American and British tastes than were the older works of fiction, there is reason to believe that our efforts had something to do with the change.

The Press came out of the endeavor with one of the two best Latin American book lists among American scholarly presses, the other being that at Texas. Since then interest has declined somewhat, perhaps, but retains a part of its strength. If fortune should send along another Lesley Simpson—our most prolific author and translator—we might see another flowering.