PART TWO—

SUSTAINING BODY/MIND/SOUL

Polymorphous Perversities

Female Pleasure and the Postmenopausal Artist

Work on this paper was supported by a Faculty Research Award from the University of Nevada, Reno. I especially appreciate the travel funds that allowed me to interview artists across the United States. My deep thanks go to the artists, for their time, honesty, and interest in this project.

Parts of this chapter appeared in M/E/A/N/I/N/G 14 (November 1993) and are reprinted by permission of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues.

Other versions of "Polymorphous Perversities" have been delivered at:

The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, June 1993

Art Works Gallery; San Jose, California, July 1993

Artemisia Gallery; Chicago, Illinois, October 1993

School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, February 1994

Women in Photography Conference, Houston, Texas, March 1994

[Wearing a form-fitting minidress that reveals her shoulders and arms, Frueh assesses the audience. Her pearl necklace and bracelet are visible to them, as are her sheer black stockings and short black boots with low heels. ]

In The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography Angela Carter writes, "It is in this holy terror of love that we find, in both men and women themselves, the source of all opposition to the emancipation of women." In D. V. , Diana Vreeland states, "The beauty of painting, of literature, of music, of love . . . this is what men have given the world, not women."[1] I vehemently agree with Carter and disagree with Vreeland. The circulation of love, within the bodies of women and within civilization, which supposedly sustains human life, accounts for the (im)possibilities of pleasure. Vreeland turns love into a misogynistic joke against women, for to claim love as men's invention is to hate women and implicitly to laugh at their displays of passion and creations of pleasure in art or in life, to infantilize them, and to turn them into sphinxes—mysteries and monsters.

Reconceive the monster. She is an emancipatrix in her perversities, a muse of beauty and hilarity, a circulator of love.

Research and conversation tell me I would be unwise to generalize about postmenopausal women. But society's erotic and aesthetic aversion toward old(er) women drives me to speak for their pleasures, to theorize them, and to situate this material in my continuing development of a feminist erotics. I base my ideas on four areas of study: looking at and loving old(er) women, the experiences and art of women visual artists over fifty, feminist writings on female pleasure and eroticism, and literature on menopause and women's aging.[2] My desire is to make connections between visual pleasure and female pleasures from a position of difference, female aging, that is a largely uncharted territory, outside cultural maps of conventional femininity, and that consequently may provide feminism with new models of female pleasure.

Theorizing Observation

I remember grandma with her silver-white hair in a French twist.

She faces me in a white mink coat, wearing a diamond wedding ring, pearl necklace and bracelet. Five feet tall and unmadeup, my grandma embodies an oxymoron, unpretentious opulence.

After grandma died Aunt Sylvia and I found raspberry suede gloves in grandma's dresser. Sylvia asked, "Do you want them?" I said, "No." I was a fool.

But the diamonds and pearls have become mine, the link to a love-site of visual pleasure, my grandma, the legacy that charges me to articulate how seeing and being an old(er) woman need not be disjunctive.

Often the old do not like to recognize themselves, for aging can be a process of "adaptive repulsion" that may indicate psychic ill health.[3] Getting used to the mirror's "ugly" reflection may give in to the social incorrectness of embodying a difference, old(er) age, that is more apparent and more deeply felt by people than that between the sexes. The young(er) woman wants to be seen, the old(er) woman is hypervisible, yet, paradoxically, erased by society's alienation from its aging bodies.[4]

In my Performance Art class, women students in their early twenties talked about beauty. They cited beautiful old(er) women—a grandmother, Georgia O'Keeffe. Then one asked, with witty humanity, "But do you want to look like that?"

I catch myself staring at an over-fifty woman in a conservatively patterned miniskirt that matches her blouse. She leans on the counter in a SoHo gallery and runs her fingers through wheat-in-moonlight hair. I turn away, embarrassed to be scrutinizing a gesture and a look that seem forcedly sexy. Then I question the force of sociovisual conventions—only young(er) women can assume the appearance and postures of sexiness—and of two wishes: that her sexuality disappear and that her desire for her visual pleasure in herself not compel me to look at her.

I revise my fearful need for her and other old(er) women to age gracefully, a euphemism for fading away, lulling lust. Grace derives from Latin gratia, a pleasing quality. An old(er) woman who doesn't act her age is not pleasing, unlike a young(er) woman in the guise of femininity, because the old(er) woman exposes her pleasure, which society tries to deny and names indecent.

Gratia also means thanks.

Amazing grace.

I thank the woman in the gallery for the indecency of defiance.

I watch my aesthetician's hands as she prepares to give me a facial. She grooms them as glamorously as she does her face. Deft knowledge about beauty rituals need not hide age, nor does it necessarily betray submission to the cosmetic industry. My aesthetician's hands declare attentiveness to detail: the contrast between lightly tanned skin, mottled by darker spots, and madder red polish, the just-this-side-of-exotic nail length, the well-lotioned skin. I respond to the thick veins underneath as one more element in a picture of lush softness and lucid style.

Love of color and texture is not a crime that old(er) women commit against themselves. Old(er) women's self-aestheticization is autoerotic action and event that destroy visual pleasure as we have known it.[5] For the postmenopausal woman cannot be the feminine fetish, eroticized by patriarchal womb-worship. The nonreproductive woman's self-aestheticization deaestheticizes Woman as socially constructed femininity.

In society's eyes the old(er) woman who costumes herself in feminine beauty has usurped it from the young. But if there is a costume, anyone can wear it, anyone can be feminine, including the erotically disenfranchised postmenopausal woman. It is not that she makes femininity ugly but, rather, that she refuses to accept the exclusive canon of womanly beauty. Her defiance both shatters and expands the aesthetic of femininity and opens the way to new meanings of woman.

One of my friends wears her hair in a braid that reaches the middle of her back. She used to ask me, "Do I look old and severe like this?" I'd look at her hair, which is whiter each time I see her, once or twice a year, and the lines in her face, the creamy peach or subtle pink lipstick, the lavender, apricot, or buff eyeshadow, and her radiant complexion, and I'd say, "You're beautiful." Now she no longer asks the question. "It suits me," she says of her hairstyle and adds, "Fuck 'em."

Carolyn Heilbrun writes,

Biographers often find little overtly triumphant in the late years of a subject's life, once she has moved beyond the categories our available narratives have provided for women. Neither rocking on a porch, nor automatically offering her services as cook and housekeeper and child watcher, nor awaiting another chapter in the heterosexual plot, the old woman must be glimpsed through all her disguises which seem to preclude her right to be called woman. She may well for the first time be woman herself.[6]

I am not promoting femininity but, rather, its fluidity. Even though femininity is misogyny's attempt to sanitize the female body, femininity is also a complex of pleasures that are lived and available and that women can use in order to change them. The heterosexual plot may try to entrap old(er) women in youth, the purchase of beauty products, plastic surgery, and gym memberships, but age triumphs over youth and cannot be contained by purchases or by the fictions in outworn biographical narratives. Postmenopausal eroticism, which includes taking pleasure in the vision of oneself and creating that pleasure, is overt triumph over societal and self-repulsion.

Women can choose dyed hair, red lipstick, "inappropriate" dress, styles of flamboyance, spectacle, elegance, or "tastelessness" that may be indicators of self-love and lust for living. Margaret Simons recounts her first sight of Simone de Beauvoir: "I was shocked when she opened the

door. In spite of looking old and wrinkled, she had the audacity to wear red lipstick and bright red nail polish!"[7] In this context the word audacity seems ageist. Although I like the implication or effect of red's rudeness, the idea that an old(er) woman must be brave to wear bright cosmetics saddens me. Color is pleasure, and Simons's shock suggests partial recoil. A viewer cannot assume that an old(er) woman alive with colors and sensuous bodily and clothing surfaces is trying to mask her age because she hates herself.[8] Then the narrative closes. The old(er) woman who chooses pleasure does not wait for the next chapter, which patriarchy has already written. The heterosexual plot, having excluded old(er) women from the love story of romance and breeding, has no words for women's love of themselves.

My mother dyes her hair bird's-wing black, and she wears crimson lipstick. After almost forty years of cutting her hair very short, she's growing it, at age 81.

My father tells her she has a heartshaped face.

[Frueh 's voice becomes soft and especially smooth. ]

My mother is the face of love.

Well-preserved does not describe mom or grandma, my aesthetician or my friend, for femininity has not mummified them. To preserve is to protect, to save from spoilage or rotting, to keep for future use, to maintain an area for hunting, to put up fruit. The well-preserved old(er) woman is always in danger of becoming overripe, damaged by age, unsavable and unsavory, worthless for the mating chase because she is a victim of language whose hatred of her rigidifies pleasure. The well-preserved woman is a dead body, embalmed by a disgusted secularization of women once the culturally sacred womb can no longer bear children.

The postmenopausal body deserves cultural resurrection as a site of love and pleasure.

Without love, there is no revolution,

And without pleasure, there is no freedom.

The Other Side of Privilege

Female pleasure has been theorized in terms of sexual difference but insufficiently in terms of women's differences from women. This mat-

ters, because patriarchy has determined reproductive woman to be desirable, a site of pleasure, and postreproductive woman to be undesirable. Younger women live the privilege of bondage to the eroticized reproductive ideal. Old(er) women live beyond that privilege.

The castrated woman of Freudian theory gains power, the phallus, by bearing a child. Her erotic power is beholden to insemination, imagined or real, and erotic myth builds on woman's capacity to seduce the male organ into the hole/hold of creation or to mangle male hopes. Man fears the cunt (vagina dentata ), for it may destroy him, but he worships the womb, for it aggrandizes his self-image. This story lays the groundwork for hatred of old(er) women. A man cannot impregnate a postmenopausal woman, cannot even imagine his creativity visible in her body. Thus menopause is a subversion of female reproductive organs as the origin of male desire (and greed), of erotic symbols and narratives, and of womanhood when spiritualized as cosmic center of the female body.[9]

Womb-privilege operates along with the eroticization of young(er), firm(er) flesh and muscles, which represent the phallic symbol, the penis, in its state of power, erection. The old(er) body is the equivalent of detumescence and represents phallic failure. So man must avoid entry into the tomb of his desire.

Womb is a privileged word, whereas uterus is not used in a spiritual or romantic context. Menopausal and postmenopausal hysterectomies remove the uterus, not the womb. Elinor Gadon writes, "I suggest that women s wombs are their power centers, not just symbolically but in physical fact. When we say we act from our guts, from our deepest instincts, this is what we are speaking of. The power of our womb has been taken from us."[10] She is not talking about hysterectomy but, rather, of the devaluation of soul-and-mind-inseparable-from-the-body wisdom.

I agree that the body, woman's and man's, is a vehicle and site of wisdom, and perhaps Gadon's old(er) woman could retain her wiseblood regardless of whether she had a uterus. In Privilege (1990), filmmaker Yvonne Rainer presents the information that "by age 50, 31% of U.S. women will have had a hysterectomy. Hysterectomy is the most frequently performed operation in the U.S. . . . Hysterectomies . . . garner $800 million a year in gynecological fees. There is a popular saying among gynecologists that there is no ovary so healthy that it is not better removed, and no testes so diseased that they should not be left in-

tact." I question the wisdom of locating female power—erotic, mystic, intuitive—in an organ that reads differently according to its owner's or former owner's age.

Luce Irigaray's "Ce Sexe qui n'en est pas un," as title, pun, and article, poeticizes and analyzes female pleasure as multiple, a polyvocality of organs, surfaces, sensations, and as inclusive of differences among women. I gather from Irigaray's arguments and ecstasies that any and all female bodies are erotic. Patriarchy, then, is arbitrary in its eroticization of the firm(er) phallic body, the vagina that is the corresponding nothing to man's something, the womb that is his dream of himself, and in so doing more severely castrates the old(er) woman than the young(er).

Arbitrariness is historically specific, so if Cranach's, Rubens's, Titian's, Renoir's, Boucher's, and Modigliani's nudes, all young but variously fleshed, have been seen as erotic, so can the old(er) female body. For the eye is polymorphously perverse and can be trained and lured into diverse pleasures, just as the libido can be.[11] Erotic desire floats, ready for grounding, awaiting direction from a desiring or loving subject. Changing the image of female erotic object from the youth ideal of Western art and advertising demands a change in the parameters and focus of love, the applications of femininity, and the source of female privilege, which has been patriarchy's maintenance of its own empire of desire that has used the female body to further male ends. In actuality, pleasures can abound in any body and therefore appear on "the other side of privilege."[12]

Rainer's Privilege presents variously privileged voices and characters, female, bourgeois, African-American, Nuyorican, male, poor, lesbian, heterosexual, young, menopausal, and postmenopausal. The last two positions receive the greatest attention and are spoken by a number of women and in diverse visual and narrative contexts. One story appears on a computer screen, and part of it reads:

A woman who is just entering menopause meets a man at a conference at the University of El Paso. They hit it off. Later, after hearing his lascivious remarks about a much younger woman, she is shocked at having misinterpreted what she had thought was mutual sexual attraction. Toward evening, from the hilltop heights of the university, a Mexican-American student points out to her the sprawling shanties of Juárez across the Rio Grande. In the gathering dusk she realizes she is on two frontiers: Economically, she is on the advantaged side

overlooking a third-world country. And sexually, having passed the frontier of attractiveness to men, she is now on the other side of privilege.

This declaration of self-recognition stuns me. I see a European-American woman of independence, self-esteem, professional standing, more than adequate income, and confidence in her attractiveness shocked to be persuaded that she is other from the self and persona she believed in. I see her standing above the Rio Grande, dumbstruck and fucked by a society in which, just as suddenly, women of fifty or so wake up to find that men have been the locus of their existence and to ask, now that they have fallen from the grace of womb-love, what do they love in themselves and in their unbecomingly hypervisible because erotically invisible sisters? In Privilege , Jenny, the menopausal hub figure, starts up from the bed where she has just had sex with a male lover, who is young in this flashback where she is her contemporary fiftyish self, and she exclaims, "My biggest shock in reaching middle age was the realization that men's desire for me was the lynchpin of my identity."

The El Paso story and the images it creates in my mind haunt me and force rumination. They point out a gap in women's lives and in the stories about them that begs to be filled by an eros that is self-reliant and resilient. The El Paso story speaks of loss and of the silence of teller and audience at the end of a sad or amazing tale. But to maintain that silence would be to accept the closure provided—dictated—by Heilbrun's heterosexual plot. So I continue the story and say that, loosened from the privilege of constrained eros, an old(er) woman adventures after different pleasures, polymorphous and perverse because they neither play to nor rant at the father who demands erotic conformity and submission and therefore provokes hostility, and because they demonstrate the impropriety of existing at all and the intractability of a subject who will not nullify her lust for living.

Grant Kester's discussion of alternative art's rant genre, practiced in large part by performance artists, including postfeminists, started me thinking about the rant nature of much visual art by postfeminists and post-postfeminists, exemplified in works by many young(er) women in 1920: The Subtlety of Subversion, the Continuity of Intervention at the New York Gallery Exit Art/The First World (6 March-7 April 1993). Kester writes, "The implied viewer . . . is often a mythical father figure conjured up out of the artist's imagination to be shouted at, attacked, radi-

calized, or otherwise transformed by the work."[13] I believe the old(er) woman artist of feminist conscience speaks to the world, not to the father. When she taps into the polymorphously perverse libido, she can circumvent—and demolish—people's domination by the father-in-the-brain who oversees and de-eroticizes most bodies.

Awakening is a passage (El Paso, The Pass) on the great river (Rio Grande) of life, after which women can no longer pass for young. Passage releases them from the social order's dominant erotic games of coercive femininity and heterosexuality, and conscious passage encourages new formulations of desire. The proliferation of polymorphous perversities from and within the postmenopausal soul-and-mind-inseparable-from-the-body open-ends female ways of seeing and being pleasure. The old(er) woman need not be the Crone or the matron or feminine forever, ways of aging that satisfy some women but are insufficiently diverse. The Crone archetype offers a model of wise old age, usually earth-connected; the matron is a model of self-sufficiency and welcome invisibility; and feminine forever may necessitate posthuman control—cosmetic surgery and hormone replacement therapy.[14]

The social order is safer with fewer models than with many and is especially secure when women mourn their youth. They mourn because they see so few models of power and pleasure. The proliferation of polymorphous perversities in postmenopausal women's self-presentation and -concept would help reify historian and singer Bernice Reagon's statement about menopause, and I paraphrase her, It's the point from which you fly.[15]

The Art of Flying

Visual art reifies pleasure. Images, objects, and artmaking processes are testimonies to artmaking as the production of pleasure, for the artist and for the viewer. Making art is the practice of love, and many women artists over fifty say that doing what you love keeps you young. Underlying the various ways women express belief in artmaking as fountain of youth, I find erotic motivation.

The erotic is rich living and, ultimately, an involvement in the transformation of self and society. The erotic is pleasure-work, the means and ends of flight. Its practitioner engages in social risk and provides social sanctuary, for the art of flying is a provident skill. I think of Erica

Jong's Fear of Flying (1973), about a young(er) woman's investment in erotic action and fantasy—the Zipless Fuck—and compare the novel with Privilege , in which Jenny finds that men have flown, and I imagine she must search out new ways to fly, not necessarily without men but definitely different from a young(er) woman's assertions of erotic will.[16] Jenny exemplifies Maxine Kumin's Sleeping Beauty:

When Sleeping Beauty wakes up

she is almost fifty years old.[17]

The rude awakening is the beginning of mature yet strangely fledgling flight, of a new erotic movement and new aesthetic assessments that do not demean Awakening Beauty for either the phobic dreams of old(er) women's age she has shared with patriarchy or for innocence about the mysterious beauty that has become aware of itself and that she must investigate. Sleeping Beauty wakes herself up from the coma of delivery by man, and though her prince may come, erotic union with him will not fit into the heterosexual plot. One reason is that she has negotiated an autoerotic awakening. Beauty Aroused is an erotic agent, Dorothy Sayers's "advanced old woman [who] is uncontrollable by any earthly force," for she can fly.[18]

A number of women artists over fifty are overcoming Sleeping Beauty's fear of flying. Below I discuss the work of three: Bailey Doogan, Claire Prussian, and Carolee Schneemann.[19] Each formulates a reification of the aging physical and psychic body, a way to see and experience sensation, emotion, and palpability, to understand erotic accesses and outlets of the self, whose wholeness an individual, looking at or touching her body, cannot entirely grasp.

Beauty Aroused is pleasure-vehicle, the artist, and pleasure-product, the art. Beauty Aroused is subject, muse, and artist in service of her self, a triune power whose erotic engagement in visual and female (self-) pleasure dismantles Diana Vreeland's misogynistic, Paglian statement that opens this paper: "The beauty of painting, of literature, of music, of love . . . this is what men have given the world, not women.

I do not want the listener to think that just because Doogan, Prussian, and Schneemann all deal with the female body I am reducing visual pleasure in women's art to anatomical or somatic expression. Visual pleasure, and its relationship with female pleasure, continues to be a largely unarticulated aspect of feminist discourse. I attribute that partly to the lingering success of Laura Mulvey's "Visual Pleasure and

Narrative Cinema" (see note 5, below) and partly to feminists' body-phobia, even prudery, this despite a growing literature on the body.

Theoretical focus on the female body as site and vehicle of feminist visual pleasure is necessary. CORP (Canadian Organization for the Rights of Prostitutes), addressing what they considered feminists' condescending and patronizing attitude toward prostitutes, wondered in a 1987 publication, "How can they [feminists] hear us talk, how can they hear us when they can't even hear their own bodies? They are continually shaping it with their minds. . . . Whatever their bodies are telling them somehow comes up through their minds, and then they shape what's comfortable."[20] I would rather have a shapely soul-and-mind-inseparable-from-the-body, disciplined, determined, and liberated by inevitable discomforts of thinking and feeling, than be shaped by intellectual prudence bordering on a prudery that disjoints mind from soul from body and sex from intellect.

For better or worse, we are wed in utero to our bodies, and as my friend Helen says about the body, "It's all we have." This is more realistic than fatalistic. The body is radical, is, in tandem with mind, root and heart of knowing. A woman's sexual organs do not define her root-heart, for that would mean the rest of her is aphasic. Beauty Aroused is erotic art(ist), fighter, speaker, and seer militating against continuing Cartesian escapism into presence through mind. Beauty Aroused minds the body and embodies thought—she is an activist—and she reifies the fact that woman is an erotic territory yet to be explored by herself. That exploration is necessary and revolutionary. If you think it is utopian, consider that eros is reality rather than perfection, and always within reach.

Bailey Doogan

Doogan says, "Female pleasure is a Pandora's box. So much goes against your realizing what female pleasure is, but something about female pleasure is connected with a freedom and acceptance of myself. I find that I often can't talk about the things I care about and the passion for what I care about is reserved for my work.

"I feel more of a going inward as I get older," and perhaps this is associated with a positively narcissistic scrutiny: "The older I get the more I stare at myself." This desire to know one's soul-inseparable-from-the-

body through observation is Doogan-the-artist's pleasure, and she duplicates her visual self-fascination in her paintings of the old(er) female nude. She says, "I feel as if I'm crawling over the bodies inch by inch" as she paints.[21]

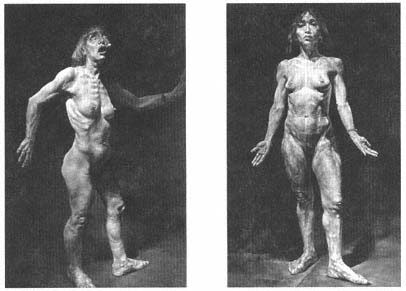

Doogan wants to "define the body in relation to culture." As a painter of the female nude/herself seen in her model's flesh, Doogan uses male visual language to shatter it while simultaneously creating what male visual language has made absent. Feminists have continually reiterated the problem of producing changed meanings while speaking male language, which has been the only one available. Don't vocabulary—the female body—and syntax—youth and beauty—wrest change from the female and feminist painter's hands? Mightn't an aging body simply be perceived or interpreted as a facile mockery of the standard? No, for the old(er) body, in contemporary American culture, is never a gloss. The old(er) body, within the conventions of Western art and its vampiric relative, contemporary advertising, represents chaos, because it does not submit to the strictures of domination that have pictured the female body for man's eyes. While the standard female nude or nearly nude in advertising is a sweet that pains a woman's mind-and-soul-in-separable-from-the-body, Doogan's figures in works such as Mea Corpa (1992) and Mass (1991) are sights for women's sore eyes.

Whereas the conventional female nude is an icon of womb-worship, Doogan's nudes retheorize the canonical female body.[22] Her iconoclasm goes beyond resistance or rejection because she invents a difference from the norm that does not transcend the significance of liminal experience. Although Western culture has construed the female body to be more liminal than the male, because the former manifests blood mysteries and has culturally been defined more cruelly than the male body as exemplar of time's ravaging passage, Western art has denied that liminality by shunning age (as well as pregnancy, menstruation, and menopause).[23] Western art's use of the female body to control time—aging and death—contributes to our fear of flesh that moves, wrinkling, even shrinking, with age in a dephallicizing process.[24] As I said earlier, the old(er) female body is the tomb of man's desire. To picture the old(er) female nude is to represent the ultimate patriarchal taboo, the end of patriarchy. Doogan's female nudes, then, are models of feminist and female pleasure. They are made by a woman who questions to death the premises of erotic argument (only the young(er) body is desirable, and patriarchy decides that), and the subject who questions experiences pleasure.

The liminal body, Sleeping Beauty, represents desire.

[Frueh says, "Lights down, please. Projector on." A slide of Mea Corpa appears. As the discussion of the painting progresses, Frueh shows details so that the audience cannot ignore its departures from conventional nude beauty. ]

She is Mea Corpa, my body, standing in the posture of the resurrected Christ, and her flesh moves with the energy of eros. Veins protrude along her calves and feet, skin creases at her ankles and waist and both clings to and bulges at her knees. Light does not caress her, it illuminates her new seductions: heavy eyelids and undereye pouches, bony shoulders, muscled arms and legs worked out in the gym and worked on by the force of gravity over time. Doogan's crawling over every inch results in a body that feels like fluids, flesh, and organs and that recalls Monique Wittig's resuscitation of the female body in The Lesbian Body:

THE PLEXUS THE GLANDS THE

GANGLIA THE LOBES THE

MUCOSAE THE TISSUES THE

CALLOSITIES THE BONES THE

CARTILAGE THE OSTEOID THE

CARIES THE MATTER THE MARROW

THE FAT THE PHOSPHOROUS THE

MERCURY THE CALCIUM THE

GLUCOSES THE IODINE THE

ORGANS THE BRAIN THE HEART

THE LIVER THE VISCERA THE

VULVA THE MYCOSES THE

FERMENTATIONS THE VILLOSITIES

THE DECAY THE NAILS THE TEETH

THE HAIRS THE HAIR THE SKIN

THE PORES THE SQUAMES THE

PELLICULES THE SCURF THE SPOTS[25]

It is not that Doogan shows everything, and Wittig's words are certainly neither enumeration nor description. Like Wittig, Doogan expresses flux and inseparability by using erotic syntax and creating a body—a word that feels too categorical in Doogan's and Wittig's usages—that deserves the name "m/y radiant one."[26]

Naked splendor in Mea Corpa offers itself to female eyes and recovers itself from the guilt, mea culpa, of not being beautiful or correct enough to be seen. This female figure steps out of the (literal) darkness (of guilt) deaccessorized of conventional erotic props such as bed, fan, drapery, fruit, flowers. She displays appetite for herself, my body , not the one Western art invented and permuted for Woman, so my body has risen, flown from the dystopian eros developed by patriarchy. Doogan puts an end to anorexia of the spirit.

In 1987, at forty-six, Doogan painted Femaelstrom ,

[slide appears ]

in which a female St. Sebastian, haloed in gold leaf and pierced by arrows—actual sticks of wood dipped in red paint—gazes towards a bevy of bean pods, upon each of which Doogan has painted a young bikinied woman. The femaelstrom is women's confusion over Western culture's splitting of woman into saint and sinner. The next year Doogan produced a monumental triptych, RIB (Angry Aging Bitch) ,

[slide appears ]

a mixed-media drawing that rails against woman's creation from the body-mind of man. In each of the piece's panels Doogan depicts an old(er) female nude. Femaelstrom and RIB are characteristic of Doogan's late 1980s female nude—suffering, melancholy, aging in monumental resoluteness and inspirational rage. The nude in Mea Corpa , Mass ,

[slide appears ]

and Hairledge (1993), all completed after Doogan turned fifty, suggests reconciliation, the balance in one body of sensuousness and spirituality, a redirection of displeasures from injuries sustained from the fathers to pleasures maintained in service to oneself.

Pleasure, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder, who is me and you and who may wish to remake the meaning of Pandora's box. Remember Doogan's "Female pleasure is a Pandora's box." Female pleasure curses only misogynists, and we need not believe Hesiod's story that Pandora's box held evils and afflictions, that, though warned not to open it, she did out of curiosity, and consequently made humankind accursed. The "curse" of the old(er) female body is chaos. The culture that has perceived and mythicized the old(er) female body's terrific disorderliness has also made it unsightly and invisible in order to shore up the young(er) female body as an object and idea of phallic security. When the old(er) woman, Doogan in this case, releases her polymorphously perverse libido, she releases chaos, which is Pandora's gift.[27]

Doogan's female nude is vessel, locus, and outpouring of curiosity and subjectivity. The name Pandora means All-giver, from the Greek pan , all, and doron , gift. Barbara Walker writes, "Pandora's vessel was . . . a honey-vase, pithos , from which she poured out blessings: a womb-symbol like the Cornucopia."[28] So that we do not continue the womb-worship that is detrimental to old(er) women's erotic social security, let us simply say that Pandoras, such as Doogan, dying for a look into what man has warned them in visual and popular images not to see, release self-knowledge, which is a blessing.

Pandora's box holds erotic sweets, which patriarchy withholds from old(er) women, whose defiance is auto-expression, without which transformation, social or personal, cannot occur. To turn Doogan's phrase, Pandora's box is female pleasure gone wild, the pandemonium feared by some viewers of Doogan's paintings and blessed by others. I've heard several people compare her figures to Ivan Albright's. Both artists do present unforgiving scrutinies, but Albright's most-remembered paintings depict pathetic specimens of decay. Their flesh mocks them with the futility not only of vanity but of living itself, so the figures, which are rarely nudes, become emblems of dying and death. Their skin looks iridescent, diseased, and worn, and they seem predisposed to growing tumors. If Doogan's bodies seem like sore sights that frighten women's eyes, that is only because they are unaccustomed to chaos, which is

Doogan's assertion of corporeal specificity and individuality as beautiful. Doogan is friendly to the female body, and Mea Corpa, in Doogan's language, reads most significantly as destigmatization, a transformation from guilt to self-possession that is responsible to women's real bodies. This happens because Doogan has made a spectacle out of the old(er) female body.[29]

[blank slide ]

Claire Prussian

Claire Prussian writes to me, "I remembered when I was in art school how much more I loved drawing fat old models. Young ones were not interesting. Funny, I haven't thought about that in years . I love clothes so much more now, and jewelry. Beautiful things have assumed a different dimension, it's not just material. And I feel more comfortable in my body, spiritually—not physically—too many aches, pains, but I'd rather feel this way."[30]

In her studio Prussian talks with me about clothes and apologizes several times for her interest in them. Later, after having lunch at a restaurant in Chicago's Neiman Marcus Building, we look at clothes. She points out a Mary MacFadden gown that falls in rippling pleats from a densely sequined and embroidered bodice. Floor-length and long-sleeved, the dress would entirely cover a body. Prussian speaks of such dresses as armor. They would conceal a wearer in power. She says too that many old(er) women's hairdos are helmets. "If I have to be old," said Prussian at lunch, "I'll be the most elegant old woman you've ever seen." She adds, "Style doesn't take lots of money."

Prussian's interest in clothing and style must not be misconstrued as simplistically materialist. Although feminists heatedly critique the dogma of beauty, they have written very little about beauty itself.[31] Patriarchally instituted beauty doctrine—look young-sexy-beautiful so men can better worship your womb—garners so much feminist attention that feminist theories and practices of female beauty, especially regarding old(er) women, do not arise.

The feminist critical gaze has eyed Joan Collins and Madonna, professional beauties skilled in professional seductiveness.[32] Madonna and Alexis Carrington, an old(er) sexpot played by Collins in the nighttime

soap opera Dynasty , function for some feminists as women who are self-consciously desiring and desirable: they are sexual agents as much as objects, and they enjoy both roles. Like Madonna and Alexis, Prussian can afford to buy glamor, but, unlike them, she does not adhere to the erotic orthodoxies of slenderness clothed in absolute fashionableness, skin made up into a doll-like dream, and signs of aging entirely eradicated by hair coloring or surgical and photographic means. Prussian underwent cosmetic surgery but directed her physician to leave certain lines because "I wanted to look my age but more rested." Prussian's love is not youth but style, which can be the creation of self, whereas fashion necessitates the bending of taste to currency.

Wherever possible, women must reinterpret beauty in their personal style, in their work and workplaces, so as to make beauty nongenerational. Women must control the images of their desire, which means making them anew. I don't expect absolute authenticity, images from the origin of female desire—can we know or believe in such a location?—But I do demand complexity in the symbolic representation of women. Beauty in old(er) women requires creative visual expression that burrows and flies with Naomi Wolf's idea in The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women that old(er) women are "darker, stronger, looser, tougher, sexier. The maturing of a woman who has continued to grow is a beautiful thing to behold."[33] But women must soar and dig much farther. Though Wolf's assertion is easy for young(er) women such as herself to pronounce, it is exceedingly difficult to practice from an old(er) body. Patriarchy's horror of the old(er) female body stems from attraction to the vision and then to embodiments of old(er) beauty, from fear of men's damnation by new desires that would mean oblivion, an end to the psychic perpetuation of control over women and to the actual perpetuation of the human race. Man would forget his duties.

Prussian's images of beauty for women sometimes rawly confront aging, but more often they displace it. The beauty of armor and helmet—the screen, to use Prussian's word, of style—appears repeatedly in her drawings, prints, and paintings. Screen should not be confused with fashion, for fashion shifts, it is a personality that flutters, while style holds, like a barrier invested with self.

Born in 1930, Prussian says that "growing old is a real loss of self, a narcissistic injury" that may result in "a dedication to screen." In her art

the screen, which includes luxurious fabrics and settings, proliferation of pattern, reveling in flowers and plants, and sensuous detailing of aging skin, is the psychic body. Her images depart radically from cosmetic surgery, the au courant, posthuman way to screen, or mask, female aging. In contrast, Prussian's works are screens that let down a guard against aging. They both comfort the viewer and set her on edge.

Vanitas (1981)

[slide appears ]

is a triptych whose rich lithographic tones describe the face of a woman about Prussian's age who was a friend. In the right panel she faces left, almost profiled; the central panel features her larger, head-on, and framed so that no hair shows; and in the left panel she is in three-quarters view, facing in. All the portraits are insistent closeups of a goddess of aging whose nonchalant sophistication—the way she holds a drink as if toasting or caresses one finger with another—speaks self-awareness. Prussian delineates her subject's fine and deep lines, eye pouches, and nose-to-lip folds. They are as lovingly and sensuously determined as are the hollows of her cheeks as she eyes the viewer from the central panel.

Vanitas treats the end of female vanity based in conventional femininity. Unlike Renaissance paintings whose theme is vanity, Prussian's print does not feature a young naked woman gazing in a mirror, nor does Prussian critique female "narcissism." Her composition recalls a three-part mirror, before which a woman makes up while looking at herself closely and at different angles. Here the making up is not cosmetic but, rather, a reconciliation with one's face by examining it.

In Latin vanitas means emptiness, and vanitas paintings in seventeenth-century Flanders and Holland were allegorical still lives. Prussian does not use any traditional objects from such paintings, which are meditations on transience and the emptiness of worldly possessions: an overturned bowl or cup refers literally to emptiness. Here the old(er) subject is herself the symbol of vanitas , for she represents the end of herself as (man's) worldly possession, the emptiness of that status. The emotion conveyed, however, is not emptiness, for Vanitas is starkly full, visually and otherwise. The woman's face fills each frame with determined resonance, and her glass isn't empty. In fact, she seems to toast herself and the viewer. She is Still Life, alive, visibly unavoidable.

In Vanitas-Tas-Tas (1988),

[slide appears ]

Prussian photocopied the earlier piece in four multiples that descend from ten and one-half inches to a little more than five inches high and that stand behind one another, as if in embrace. She hinged each triptych like an altarpiece and decorated the outer altarpiece panels with brilliantly colored fake jewels glued onto patterned Japanese papers. Replication adds a funhouse dimension, an Alice in Wonderland perceptual distortion, which relates to women's conceptual self-distortions as they age: intimate knowledge of one's appearance becomes magnified and looms in one's mind, beauty seems false, only a layer of glitter. Prussian seems to take herself/the old(er) woman to task for her vanity—tas, tas sounds like tsk, tsk—but also delights in the adornment of the altarpieces. Each one is a gem of private and sacred scale, a dedication to the possibility of beauty-in-realism.

[blank slide ]

Prussian loves her subjects and their environs, belongings, and gestures. Her fastidious, explicit way of looking, whether in photorealist drawings and prints or later faux-naïf paintings, reminds me of Chantal Akerman's words in a 1977 interview about her film Jeanne Dielman (1975):

If you choose to show a woman's gestures so precisely, it is because you love them. In some way you recognize those gestures that have always been denied and ignored. I think the real problem with women's films has nothing to do with content. It's that hardly any women really have confidence enough to carry through on their feelings. Instead the content is the most simple and obvious thing. They deal with that and forget to look for formal ways to express what they are and what they want, their own rhythms, their own way of looking at things.[34]

Prussian sees and wants fullness, eros, age. She finds and plants her women in the midst of flowers. In the prismacolor drawings Woman in Blue and Woman in Blue with Flowers (both 1980),

[slide appears ]

a gray-haired woman with crimson lips and nails and diamond heart pendant sits in front of a mass of flowers. Male poets and artists have equated women erotically with fruits and flowers: women blossom and wither; are succulent, then dry up. Flowers' aesthetic and sensual beauty, epitomized in the nineteenth century by Dante Gabriel Rossetti's

visually and symbolically seductive use of them in relation to young(er) women, in Prussian's work calls into question the oppositional duality of youth and age, life and death. The subject in Woman in Blue with Flowers cocks her head, opens her voluptuous mouth in a near-sneer, moves her hands with the studied poise of a feminine smoker—her Tiparillo is caught in the breath of her conversation, in a pose that can no longer be read as flirtatious, for she is an uncanny queen of hearts. She covers her soul with sunglasses, but her body is soul nonetheless, a flower that shouts vitality. So does the body in Still Life I ,

[slide appears ]

a 1981–82 lithograph of an unclothed woman lying in an abundance of blooms—roses, irises, birds of paradise, and many more—that are her analog.

[blank slide ]

The body becomes less relevant in a series of portraits from the early 1980s. Or perhaps I should say that the psychic body is obviously paramount in the material world that covers and surrounds the flesh. In such compositions the sitter is defined by a

[slide of Portrait of Grace Hokin (1982) appears ]

deep-rose lace dress and a dusty pink and gray abstract floral patterned drape, or by her

[slide of Woman from New Jersey (1983) appears ]

fluffy white cat, blond helmet hair, multicolored sweater, and literal screen of vegetation, or by her

[slide of Portrait of Shirley Cooper (1982) appears ]

fur jacket and sofa of similarly delicate hues, or by a

[slide of Portrait of Ruth Nath (1982) appears ]

soft apricot wing chair, butter-colored curtains, and forsythia sprays in a large rust-orange vase.

[blank slide ]

In paintings from the mid-1980s to the present, each thing —flowers, fish, potted plants, wallpaper, mirrors reflecting the artist—possesses uncanny vitality. Often the mirrors and long, distorted perspectives push and open space into the super real—past, future, mythic, and strangely present times and places which are the psychic body. There the human face and figure are usually wistfully pathetic and undemanding of the eye. They are simply a visible part of the universe, and the psychic body shows its age in this displacement replete with complexity, timelessness, and beauty.

Kathleen Woodward theorizes a mirror stage of old age in Aging and Its Discontents: Freud and Other Fictions , and one section, based on Freud's writings, treats the uncanny, which may be an effect of looking into a mirror and recognizing, with shock and fright, that one is old. The familiar turns unfamiliar, for, according to Freud, the familiar has been repressed. He also relates the uncanny to castration anxiety, which may recall Prussian's belief that "growing old is a real loss of self, a narcissistic injury." The phallus dies and the double rises. Woodward says Freud follows Otto Rank in stating that in an early era of human history the double assured immortality and armed a person against death, but it came later to be seen as a messenger of death.[35]

Prussian sees herself over and over. In Untitled (1991),

[slide appears ]

a triptych whose panels she displays diagonally, Prussian appears in a magnifying mirror in the uppermost section, like a sad, decapitated head, and in the center panel we see her in the magnifying mirror and in a horizontal bathroom glass that reflects a younger Prussian opening a door to the room behind. We also see her as the entering figure would, from the rear. The Beauty Shop (1991)

[slide appears ]

is a Land-O-Lakes butter-carton illusion in which an image retreats seemingly ad infinitum. The beauty-shop mirror reflects Prussian, as does a mirror held by the hairdresser, and her image appears too in another mirror to the right of his station. An uncanny pattern—a wilderness of large, reaching, blue fern fronds—decorates the wall and chair. The latter is empty, for Prussian exists only in the mirrors and in the extreme patterning that is the psychic body or the presence of the repressed. She keeps the eye so busy with her array of fronds, rippling-grained floorboards, bricks in the buildings outside the window, and a plant whose serpentine stalks inch along the floor toward both the chair and the viewer that she staves off the death-harbinger double.

Pattern displaces anxiety; it creates much where there may all too soon be nothing and puts order into the unpredictability of life. Pattern is beautiful. One's double may mean death, but Prussian actually multiplies herself and opens psychic and physical space far beyond the confines of any particular room she depicts. Perhaps the multiple image is self-protection, like the statues of Egyptian pharaohs that housed the ka, the spirit/double after death, so that he or she would continue in the afterlife.

Prussian has used explicit ancient Egyptian imagery in her work. One example is Three Frozen Images: Beginning, Middle, End (1984),

[slide appears ]

where she stands, elegantly gowned in green—color of the generative, the everlasting—in an interior that resembles an Egyptian tomb. For the ancient Egyptians death was not the end, and for Prussian this tomb may be a house of life. Her back to us, she faces an altarpiece-like mirror and views herself in triple deity. Prussian says of daily life, "I want to see something gorgeous when I look in the mirror," so she cares about jewelry, beautiful makeup, the coordination of colors and fabrics. Rather than seeing Prussian's self-mirroring in her body of work as the fascination of "adaptive repulsion," in which the mirror distances one from oneself, we should understand Prussian's self-observation as amatory. The mirror in Three Frozen Images reflects the gorgeous self from more than one side, and the mirror can also be seen as a painting that, like a ka statue, keeps alive, provides nourishment for, the gorgeous spirit/double in the present.

[blank slide ]

In the infant mirror stage the subject falls in love with herself, but if in the old(er) age mirror stage the observer identifies with her image, she is differently transformed, supposedly because she does not, cannot desire what she sees.[36] So she is set reeling away from herself. Prussian says there are things she does not enjoy about growing old—the loss of friends and family, "too many aches, pains." But her spiritual comfort leads her to say, "I'd rather feel this way" than young(er). In her art Prussian looks into, not at, the mirror. She does not deflect aging, for she desires the looking into herself, which is the look of love. Prussian loves the time spent in her studio more than any other: "It's the only place where time feels right, not too fast or too slow." The pleasures met and created in that kind of time appear in Prussian's libidinally invested representations.

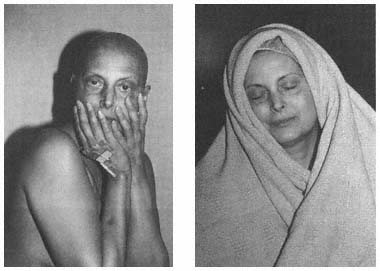

Carolee Schneemann

Schneemann talks about "the ecstatic body and the power of the ecstatic. Sexual pleasure is a capacity and gift of the organism." Eros has consistently been both source and content of Schneemann's art. Probing, ex-

posing, and loving a "hand-touch sensibility" while believing that "tactility is suspect" in Western culture, she continues to divest the female body of iconicity and to create "a jouissance beyond the phallus." This is a courageous project, for, as Schneemann says, androcentric culture has a "terror of the nonerect self"; it is age- and vulva-phobic. "The old woman is the ultimate betrayal of masculine imagination, the imagined ideal of the feminine," she says.[37] The old(er) body's tactility is especially threatening, for it is flesh that has moved by virtue of having been around so long; it is sliding, sinking, ever more earthbound. Testicles and penises move, but they belong to a reproductive program of male creation/creativity, and a penis can defy gravity. Young(er) breasts and labia move, but they are part of the reproductive plan and the heterosexual plot. Culture conceives of them as plush organs that time destroys: breasts sag, vaginas atrophy, and both dry up.[38] The realities of some men's impotence and some women's moist vaginas do not conform to cultural myth. At fifty-two one postmenopausal artist says, "I'm as horny as ever, and when I make love I'm as wet as ever."[39] Schneemann speaks of the possibility that "in the ancient goddess-worshipping cultures—Minoan, Sumerian, Celtic—there was a full female erotics, older women had respect, and men were their acolytes."[40]

Schneemann has certainly been interested in flesh, but as a vehicle rather than an end point of eros. Her classic performance Meat Joy (1964)

[slide appears ]

was flesh that moves, an orgiastic

[another slide of Meat Joy appears ]

dance of semi-clothed bodies and animal parts, an Aphroditean ritual. (She says that Dionysus stole orgiastic pleasures from Aphrodite.) While Schneemann has used her own classically beautiful body

[slide of Eye Body (1963) appears ]

in her art—one artist says, "Carolee, she personifies the goddess each time she steps out in performance"—the intention has not been to make herself into an icon.[41] Carolee-as-goddess is not Womb-Worshipped One, patriarchy's docile deity, for she celebrates the female body for the pleasure of women. "In some sense I made a gift of my body to other women: giving our bodies back to ourselves."[42]

[blank slide ]

In order to divest the female body of the iconicity that adheres to it through womb-worship and to counter, psychoanalytically speaking, its

conversion into a phallic stand-in for (its lack of) male organs, Schneemann proves the existence of female organs. In Interior Scroll (1975)

[slide appears showing sequential action ]

she stood naked and delicately unraveled from her vagina a ten-foot-long paper scroll folded in a "strange origami,"

[blank slide ]

and in Cycladic Imprints (1988–92) she uses vulval images.[43] Like Meat Joy , Cycladic Imprints celebrates eros. For an artist of any age and sex this is a victory over cultural erotophobia, for an artist to continue such work over thirty years is a tribute to her faith and fortitude, and when a woman of fifty creates such work, it is a triumph over ageist assumptions about the pleasures and desires of old(er) women, and it diverges from the only archetype as yet provided for postmenopausal women, that of the Crone. I don't object to the Crone, for she is a figure of useful power and self-esteem for some women, but as one artist, who is a grandmother, said to me, "I'll never be the grandmother, I'll never be the Crone."[44]

Cycladic Imprints

[slide appears ]

is an installation that embraces the viewer, who, upon entering, immediately absorbs and penetrates

[another slide of Cycladic Imprints]

a heady and sensual atmosphere of images, objects, sound, and dusky light. As she sits or walks

[another slide of Cycladic Imprints]

within a tangibility of eros, the viewer becomes the ecstatic body. Schneemann envelops the visitor in

[another slide of Cycladic Imprints]

a love potion, a tender orgy of slide projections—such as Cycladic statuettes, female nudes from art history, and

[another slide of Cycladic Imprints]

Schneemann's own vulva and torso, all beamed in dissolving relays from four positions—

[another slide of Cycladic Imprints]

sound, by Malcolm Goldstein, that flutters and hums into one's body like a wordless love song;

[another slide of Cycladic Imprints]

fifteen motorized violins, hung on and out from the walls, whose rhythmic movements suggest rhythms of sexual intercourse; and voluptuous,

[another slide of Cycladic Imprints]

linear abstractions of an hourglass or female form painted on the walls.

[another slide of Cycladic Imprints]

One's soul-and-mind-inseparable-from-the-body resonates to the overlay and transformation of images from historical, mythic, and (Schneemann's) personal memory, for Cycladic Imprints makes love.

[another slide of Cycladic Imprints]

In this installation the female body and its abstract figuration are everywhere, but they are not aestheticized in phallic terms and therefore are not conventional erotic models that say, "Look at me." Schneemann performs a feminist deaestheticization that recreates the female body in an intersubjective, in contrast to voyeuristic-phallic, mode. This is a restructuring of desire in which relationship is paramount. Such an artist/viewer interaction is mutuality, a subject to subject relationship that replaces the standard subject to art object one. This kind of interpenetration and embrace is mental and sensuous and, while it claims an individual's participation, it also permits her a singular though not separate presence within the spatial arena that is physical and psychic. The hand-touch sensibility reaches, caresses, and still leaves/makes room for the distance self-integrity requires.

Schneemann's visual and aural terms establish reciprocal space, where viewer and audience become absurd designations, for the gallerygoer is receptor, full of self, connections, and connectedness, but not receptacle, the feminine passive. Receptivity is Cycladic Imprints 's mode of communication. Images dissolve, music never forces entry, violins appear and disappear depending on light level and direction, so the piece is nondirective as to where a person might ground desire—except that grounding is clearly felt to be one's mind-and-soul-inseparable-from-the-body, both the organic and invisible sites of self and receptivity, onto and into which tones and images play.[45]

Schneemann does not create womb-space. She does focus on the female body, often as metonymic vulval form—the wall abstractions, violins and their cases, and, of course, her own organs. Historical repetition is the point, to which Schneemann has brought her partner in art and pleasure, the gallerygoer, as if through steady, continual orgasm, the kind a woman can undeliberately experience simply by sitting legs

crossed and not moving, upper thighs slightly pressing at an unconscious angle. This is a leisurely route to pleasure which never has to peak. To read Cycladic Imprints as essentialist—vulva is woman's center, the transhistorical and cultural mark of Woman that marks her fate; Anatomy is Destiny—is to gloss over Cycladic Imprints 's intersubjectivity as theoretical proposition.[46] Here the vulva functions neither as a simplistic reversal of phallus as symbolic representation of desire nor as a facile glorification of the female body and its anatomical difference. Cycladic Imprints is not about woman's capacity to attract or to be fertile or to bear children. It is (about) female pleasure as historical resonance and present reality.

In Cycladic Imprints the (grand)mothers come.

[blank slide. Frueh says, "Lights up, please." ]

Angela Carter writes in The Sadeian Woman that "Mother must never be allowed to come, and so to come alive." The (grand)mothers' pleasure is taboo. The expletive motherfucker identifies its object as pariah, curses him into place outside socialized sexual behavior. Schneemann dares and entices the participant lovingly to know the (grand)mothers' genitals, despised when not altogether obliterated.[47]

Taboo intimidates—and excites.

Schneemann's love opens a largely unmodeled articulation of female pleasure. In Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the "Frenzy of the Visible," Linda Williams argues that porn films have looked for the truth—and difference—of women's pleasure, visually investigating the female body and probing it for confessions of pleasure, visible signs.[48] This is far more difficult to accomplish with the female than with the male body, which—reductive and often silly though the images are—can be shown with an erect or ejaculating penis as a sign of pleasure. Just as the conventional female nude is to a great degree a sign of male pleasure and thus of the invisibility of female pleasure—in terms of actively showing female pleasure or showing active female pleasure—porn, still a male-dominant field in regard to decision-making, has not made visible the anatomically hidden location of female pleasure. A shot of a clitoris, for instance, does not convey the sensation felt there. Porn can show the effects of female sexual pleasure in facial expressions and body gestures, but picturing cannot frame and measure female orgasm as it can—however inadequately—male orgasm. Visual examination of naked pleasure, the (idealized) female body—the skin, hair, and contours of the nude,

the sex parts of the porn model or actress—cannot reveal the immeasurable. That model of pleasure-proof does not work. Cycladic Imprints, however, offers a different model, as explicit as porn when understood.

Barbara Hepworth, speaking as a sculptor who is a woman relating to form, says the relationship is a kind "of being rather than observing."[49] Observation can be a mode of surveillance and supremacy, the eye pinning and strutting over a sight. Being-in-relation treats the sight unseen. We move from I've got you in my sights, under the fascist control of one model of pleasure, to I've got you under my skin, where the irritant that is pleasure allows me room to move.

Without Love There Is No Revolution

Love is not a romance novel, and, contrary to Diana Vreeland's remark, neither is it a beauty that only men have created. Romance can be risk, adventure, and vision, in real terms that develop new narratives, which are old(er) women's love stories. The myth of the artist as risktaker, adventurer, and visionary is embedded in art history's and criticism's language of war and language of miracles, which are metaphors of spiritual and heroic prowess. Postmodern critiques have challenged that myth. But it doesn't die. Robert Mapplethorpe and David Wojnarowicz live on in contemporary art lore as heroes whose art and lives held erotic value, and the art press has lionized Matthew Barney, Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, and David Salle, still living exemplars of a masculine ethos, enforcers in their art of the patriarchal plot. Art history's and criticism's romance with them all is a nostalgic replay of Western cultural legends in current and easy incarnations of Joseph Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces.

When love is a large hunger for flesh that moves, the terms of romance transform. The art hero with the same old face turns into an actual old(er) woman whose art is known to provide erotic sustenance and activate ever more polymorphous perversities.

Has the Body Lost its Mind?

"Has the Body Lost Its Mind?" is a revision of a paper delivered on the "Theory" panel at "The Way We Look, The Way We See. Art Criticism for Women in the '90s," a conference organized by the Woman's Building in Los Angeles, in January 1988.

A version of this chapter originally appeared in High Performance 12 (Summer 1989). That material is reprinted by permission of High Performance.

[Frueh steps from a table of panelists to a podium. As she stands up, she takes off her white tailored jacket to reveal a spare peach-pink camisole. The audience gasps, and Frueh is amazed at how small a gesture can be disruptive in an academic setting. Her linen miniskirt is a similar pink, but has a lavender cast. Her stockings are white, her shoes deep rose. ]

I called my mother. I was writing a novel and wanted to confirm the details of an incident at the beginning, an accident of blood, based on her experience. She said I had conflated elements from three events, a doctor-induced abortion, a miscarriage, a sudden hemorrhaging when she walked a city sidewalk on a summer day.

[Frueh's voice catches as if she is about to cry. ]

She told me more about each happening than I had heard before, and she said too that years later, when maybe she had not needed a hysterectomy, she had been enraged at the doctor. The intensity of memory, current emotion, and understanding brought us close to tears.

[Frueh's voice gains force through volume in the next three paragraphs. ]

Maybe I am bleeding now. And maybe you are bleeding too. Maybe all of us are bleeding in more ways than one. Maybe we are hurting for

ways to love our bodies, to talk about our blood and hair, our fat and wrinkles, our sexual sensations, our treatment under the hands of lovers and the medical profession, our many changes of life.

Maybe we are searching for erotic ways of living, which express the joy, depth, richness, and responsibility of being human. The erotic is the source and sustenance of wisdom, but Western culture does not understand the erotic—that it can exist in spiritual and political activity and activism, that it can be dead or alive during sex, that it is present in prosaic as well as ecstatic moments. The erotic is expansive, but it has become shrunken due to misunderstandings of it and accommodations to dullness.

Maybe we seek an equilibrium between spiritual and political, a rejection of fear and ignorance of the female body, a state of comfort, which is the lost homeland of the body. For we are not at home in our bodies. We are not sufficiently body-conscious.

Body-consciousness comes from thinking about the body as a base of knowledge and using it as such. Mind is inherent throughout the body.[1] To perceive blood, hair, flesh, senses and their existence in a network of information—social, political, and ecological structures that are the world—is to know that the body is not dumb.

Artists and critics who deal with the voice and intelligence of the female body, especially issues or themes of blood, sex, myth, cunt, womb, breasts, goddesses, and spirituality, are sometimes called essentialist.

Before I define and discuss essentialism, I want you to know that I consider it a misnomer. This is because it is a name given by those who do not engage in what they see as its practice. Essentialism, like Impressionism, is a name given by the opposition. Many feminists, such as Mary Daly, an essentialist par excellence if we were to take the term as true, have addressed the significance of naming. On the negative side, those who are named can not only be labeled but, worse, branded and then dismissed through the name.

According to the namers, essentialism is biological determinism, glorification of a female essence, belief that such an essence is transhistorical and transcultural. Essentialists may deal with goddess myths and focus on female deity as idea and presence, as a source of empowerment. Theorists who believe in the term essentialist say that because sexuality is socially and culturally constructed, there is no female essence. They say too that female sexuality so constructed is the male-dominant culture's delimiting of women into the bondage of Woman, who is the

Other, marginalized and discounted, not permitted to be a serious shaper of culture. Essentialists, by seeing Woman as Other—sexual, natural, spiritual—maintain women's Otherness and continue women's absence from the cultural dialog.

Artist Judith Barry and film critic Sandy Flitterman-Lewis critique women's art that

can be seen as the glorification of an essential female power. . . . This is an essentialist position because it is based on the belief in a female essence residing somewhere in the body of woman. . . . Feminist essentialism in art simply reverses the terms of dominance and subordination. Instead of the male supremacy of patriarchal culture, the female (the essential female) is elevated to primary status.[2]

Essentialism is seen as simplistic, a monolithic treatment of the female body, a restereotyping. Appropriation and deconstruction, which are anti-essentialist positions, reject the idea of innate femaleness and the authenticity of women's experiences, which, because they are culturally and socially constructed, cannot be trusted. Essentialism is an artistic affirmation of what film critic Jane Weinstock, writing about Nancy Spero's handmade paper scrolls of women heroes, calls "an Other-worldliness which reinscribes the traditional male/female opposition."[3]

Mary Daly writes about metapatriarchal journeying, away from patriarchy's necrophilic lusts and into a biophilic participation in the reality that human beings are as much earth-substance as are trees, winds, oceans, and animals. Daly's belief that this journeying is "Astral/Archaic" would probably be seen by Weinstock as extremely Other-worldly rather than as bio-logically substantial.[4] (Bio means life.)

Certainly sexuality is socially constructed, but it is also bio-logically determined, grounded in the facts that there is a logic to life and that if we avoid this logic, which includes love and knowledge of our bodies, we will suffer in them.

Spero responded to Weinstock's comments. Spero says Weinstock "tries to gag me by her legislating" against myth and the body. Weinstock replies that she intended "to articulate a perspective which would bypass the biological."[5] To bypass the bio-logical is to condemn the female body to absenteeism, not to allow it to speak through the language of its owner. Granted, we all speak through the damage of male dominance, but this does not mean that we must mute the female body until a new vocabulary has been created. For we create the change, and

not through bio-logical rejection. We alter reality by asserting our presence, as body, soul, and mind. We combat absence with presence.

Weinstock says that "the Body, . . . exalted by a number of feminist artists, ha[s] become [a] victim of the capital letter."[6] This may be true, but the female body, proscribed by the namers, has also become the victim of fear that anatomy, based on past, patriarchal experience, is an ugly destiny because women's genitals, which, read by patriarchy and by many individual men, appear to provide entry into women's bodies, seem to be the source of women's passiveness, receptivity, and vulnerability. So cunt is the source of inferior human status, and, in essence, a woman is a cunt.

Anti-essentialists believe that artists who represent the female body and critics who applaud this art and deal with the female body as source and site of experience are retrograde. Eleanor Heartney writes in reference to feminism and the '80s, "Suddenly nothing seems more passé than . . . vaginal imagery, body art . . . and all the other forms pioneered by women in response to their particular experience."[7] In the so-called postfeminist '80s, it is fine, even lucrative, to deconstruct man-made images, cultural and media representations of women. But it is retrograde to be a woman who, like Spero or Hannah Wilke, uses the female body as a vehicle for exploring the lost homeland, what has been territory uncharted by women through their own images.

Spero and Wilke, among others, are interested in universalizing the female body as form and metaphor, not through a simplistic reversal of male-as-universal, but, rather, as a declaration of reality: women are present and can create their own meanings. Such work asserts that the body is not simply nature, and these artists do not assume that nature as our culture understands it is natural. In Spero's and Wilke's work, the female body speaks as culture, for its representation realizes the interconnections of art, idea, meaning, history, and bio-logic.

Anti-essentialists seem to think that the body is mind-less, but the body is intelligent and articulate. The body and the unconscious are one, unconscious and tacit knowing are closely related, and body knowledge is a part of all cognition. The opposition, armed with theory from the current voices of authority, who are mostly French and male, armor themselves against the body. They treat the body as ideology and cultural artifact, not as lived-in reality. Anti-essentialism is a technique for management of anatomy as reality.

Reality can be seen as culturally constructed, but it can also be seen as what inescapably is. Experience, accruing different meanings in different

eras and cultures, cannot be negated. Yet, like it or not, women menstruate, swell in pregnancy, give birth, go through menopause. Women artists and critics who represent and write (about and from) the body are engaged in a reconstruction of reality, so that the body, loosened from the constraint of an absolutist cultural determination, can speak as an origin of experience, knowledge, and possibility.

The female body can speak from a standpoint of unworkable cliché and self-exploitation, but it can also speak with a terrifying and truthful presence that is anything but Other. Otherness may be the divorce of mind from body, Logos from Eros, escape into the Otherworld of hyperintellectualism.

Feminism is suffering in the '80s from this Otherworldliness, a critical and artistic retreat from the body into a theoretical stratosphere from which the artist or critic observes or analyzes but is not the body. Art is an intellectual endeavor, as is criticism, but the foregrounding of theory incarcerates the mind, so that it is out of touch with the body, isolating the brain from the body. In actuality brain and body are mutually necessary: they are alert to and in love with one another. Body is all mind and mind is all body, they permeate one another, and together they originate information that can initiate erotic wisdom.

After the heat of early '70s feminism, with its angers, militancy, and cunt art, its lack of theory—a retrospective and hyperintellectualist assessment—and its academic unacceptability, we have seen in the past decade, especially in the "postfeminist" '80s, the appropriation of existing images of women for a cool art, disembarrassed of particular experience, disembodied, and we have witnessed the phenomenon of feminism grown frigid through the legitimation of gender studies as practiced by feminists and nonfeminists alike. We have seen feminists proving they are intellectuals. Perhaps this has been necessary, to know, I hope for ourselves, that we are neither simply bodies nor simple bodies. To some degree, however, I see this intellectual production, so much of it ultrasubtle in the employment and elaboration of semiotic, psychoanalytic, and deconstructionist theories, its embracing of Franco-male fashions, as forced labor. Alice Neel said, "Women in this culture often become male chauvinists, thinking that if they combine with men, they may be pardoned for being a hole rather than a club."[8] Fear of the female body separates Logos from Eros. Cunt, and all its derisive connotations, scares us. Cunt is dangerous to professional well-being.

Theory is important. But it need not be written in a dry prose filled with jargon. And scholarship is not by definition compliance with intellectual trends. Theory, stylish and elegant, can become an adornment, a luxurious covering (up) of the body.

Apparently the female body is too bald an issue, but we must find ways to be naked, to uncover whatever it is that we may be.

Hyperintellectual criticism is very much unlike the new art writing, both polemical and poetic, that art historian and critic Moira Roth saw emerging in the '70s.[9] The importance of developing such a language, one rooted in an erotics of the intellect, seems to have fallen by the wayside on the tough road to the lost homeland. If we only think —narrowly defined—about the body, our prose will be dispassionate, will close into an academic mold instead of opening into the lushness that grows from mental sensuality and experiential lust.

Knowledge, we believe, is gained through distance from the body. A choice has been made for us: we think with a narrowly defined mind and come up with austere, dis-embodied solutions to problems of living. We (try to) stand outside ourselves, so to merge mind and body consciously, to be erotic about ourselves, is misunderstood as a kind of idolatry, as if women who love the female body in their art and writing will now and forever practice the woman worship that men have promulgated.

Learning and knowing are process, the flow of information—which is emotional, intellectual, and sensuous—throughout a world of political and social structures, of rivers, woods, and deserts, and of human relationships, all of which are alive, which means nonstatic. Women who represent and write (about and from) the body may only be inching away from centuries of outworn myths about women, but measurement is not the point. Movement is.

To participate in the process of living, to be alive, we must act, and we cannot act without our bodies. If we are to take action on our own behalf, to be activists, we need an erotics of the intellect to give ideas body. The wordplay enjoyed by Weinstock in the exhibition review that cites Spero as Other-worldly is erotic to a degree. For example, it is pleasurable to hear and think about Weinstock's question, "Could there be a better way to punish the pundits than with a pun?"[10] Linguistic play and French theories are seductive, but they often serve as stimulations for a certain kind of autoeroticism, which is pleasure on the part of the thinker and initiated readers. Now, autoeroticism is important, for it affirms the subject's knowledge of herself. An erotics of the intellect

originates in autoeroticism. However, autoeroticism is insular if its practice does not include outreach, action, interaction, intercourse. Autoeroticism becomes dystopian, as Spero calls Weinstock's view.[11] Autoerotic dystopia is a difficult and ineffective place, a depressing refuge for the homeless, unless the practitioner is moved to speak, write, and act beyond the world of theory.

A better way to punish a pundit than with a pun is to kick her ass, to make her know she has a body and that sensation is real. Disrupting a pundit's linguistic security is good, for language constructs reality, but the body, constructed of blood, bone, hair, flesh, and water, is reality.

Essentialists are accused of being unreal, of being actresses playing man-made roles, posing as goddesses, acting as if they are in touch with nature unadulterated by ideology. Women who represent the female body, however, can be activators, of sexual and spiritual potential. They are activists who know that to speak with the body, for themselves, is to speak politically.

At its best, body politics is an erotic practice. So the issue of the female body in art and criticism is not necessarily one of female essence but, rather, one of epistemology, action, and love. Love is distant in theoretical autoerotics because love is action, aliveness in the soul-and-mind-inseparable-from-the-body. The kiss of love is a mouth away. Theory does not kiss us, and we as daughters, mothers, sisters, and even lovers have hardly learned to kiss each other.

My mother kissed me, with her words and heart, when she told me about her accidents of blood, and she said of women, "We're an immense club." I said, "Yes, but we need to know more about each other, to talk about our bodies."

We need to speak about and with our bodies, to make art and writing that kiss us, to know our own wiseblood.

Duel/Duet