Who Would Honor a Cynic?

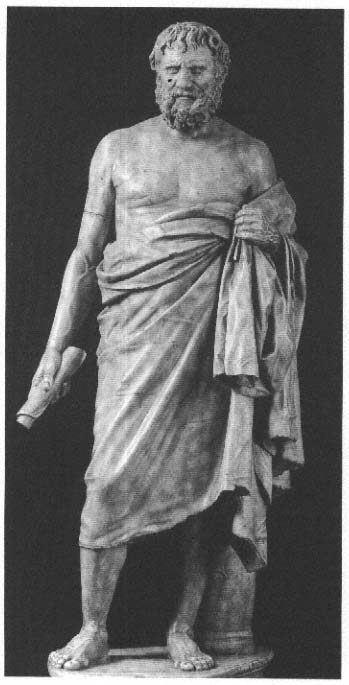

The statue of a Cynic of the mid-third century B.C. , preserved in a superb copy of the Early Antonine period, seems to satirize the new breed of pioneering thinkers (fig. 72). That this old man is indeed a Cynic has long been supposed, on the basis of his appearance, which is the antithesis of the good citizen's: he is slovenly, wears a short mantle made of coarse, dense material, and is barefoot. These are all characteristics of the Cynics, originally inspired by Socrates (Xen. Mem. 1.6.2; D. L. 2.28, 41).[43] The only element inappropriate for the Cynics, who were "practical philosophers" opposed in principle to any kind of formal education, is the book roll in the right hand. This is, however, an addition of the eighteenth-century restorer, who apparently could not imagine a philosopher without such an attribute of the intellectual.

The whole figure is practically an assault on the viewer. An ugly,

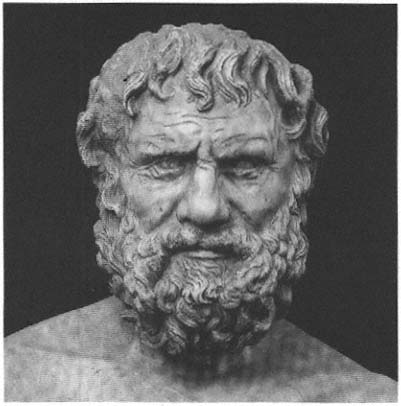

Fig. 72 a–b

Statue of an unidentified Cynic philosopher. Rome, Capitoline Museum.

belligerent old man and social outcast, he looks us straight in the face. In his right hand was originally a staff, which perhaps was even pointed at the viewer. Everything about his appearance expresses contempt for bourgeois manners and values: the clumsy, flat-footed stance, drooping shoulders and belly sticking out, the garment sloppily wound around the body and awkwardly held together in the fist, the uncombed, matted hair falling in his face, the untended clump of beard, and, finally, the wrinkled face with its vacuous, squinting look.

Here we have the complete antithesis not only of the ideal of the

proper citizen, but of the new image of the serious philosopher as well. Instead of presenting an expression of concentrated thought, he squints like someone who is either nearsighted or blinded by the sun. We need only compare the stylistically closely related countenance of Chrysippus (fig. 56) to see that the Cynic is not meant to express the concentration of serious thought or, for that matter, the ravages of old age or man's mortality but rather the self-satisfaction of a social dissident.

The public display of such a statue was itself a celebration of the provocative and antisocial behavior of the Cynics, calling into question every traditional value, a kind of fire-and-brimstone sermon decrying the pretensions and hypocrisy of bourgeois society. The simple, self-sufficient life has evidently not done this old man any harm. He seems well fed, and despite his lifelong avoidance of the gymnasium, he is shown as still tough and strong. His appearance has been likened to the iconography of poor people such as fishermen and peasants. But unlike these, he shows none of the physiognomic characterization that in this period would carry connotations of inferiority.

Who could have commissioned such a statue? It is hard to believe that a polis would have chosen to honor such a subversive provocateur with a public monument. It is equally unlikely that a man like this had a wealthy following of students and friends. But it is entirely possible that one individual, even a Hellenistic king, could have dedicated such a statue in a sanctuary or gymnasium, as a way of asserting that this was the only kind of "practical philosophy" that he truly found credible as a way of life. Though it is true that the Cynics believed in going "back to nature," to a simple life free of the "unnatural" constraints of social convention, this does not mean that they rejected the social order in principle. They too believed that virtue can be taught and saw themselves in the role of educators (D. L. 6.105). Krates of Thebes, for example, Diogenes' eldest pupil and the first teacher of Zeno, was very popular with his fellow citizens, because he actually discussed their problems with them. People opened their doors to him, enjoyed his visits, and revered him as a kind of lar familiaris .[44]

The face of the old man in the Capitoline Museum is unique in the corpus of preserved Hellenistic portraiture. Undoubtedly there were

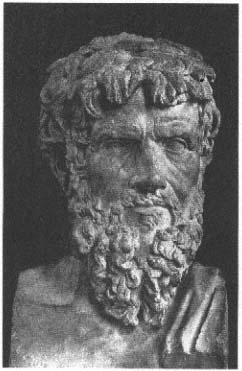

Fig. 73

Head of a Cynic (?). Roman copy of a statue

ca. 200 B.C. Paris, Louvre.

other "character studies" of this kind, in which sculptors commemorated the behavior and appearance of those who practiced a kind of antiphilosophy and a defiant alternative life-style. This is, at least, the impression we get from several copies of anonymous philosopher portraits of the late third or early second century, whose hostile expression and slovenly appearance evoke thoughts of the Cynics and related groups. A particularly impressive example is a head in the Louvre with disgruntled countenance, wild beard, and matted hair over the brow (fig. 73). The original was probably an important work of the High Hellenistic period.[45]