Iran

The Iranian presence at the world's fairs began modestly. In 1867 in Paris, the Persian park, located next to the Egyptian quarter, consisted of a small kiosk, a replica of a house, and an opium factory.[53] As Iran's exposure to the West increased, so did the elaborateness of its pavilions. But even at their most elaborate, they were less grand than those of other Islamic nations.

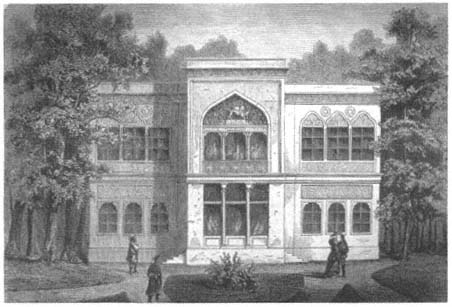

The architectural language of the Iranian pavilions was that of the Safavid Isfahan region. Although at times the pavilions alluded to particular monuments, they were never complete replicas. For example, the 1873 pavilion in Vienna was a two-story exhibition hall on a residential scale (Fig. 78). Its central part projected, with an entry at either side and porches on both levels; the large pointed arch on the projection resembled arches of the grand iwans (vaulted halls), but here, uncharacteristically, it was divided horizontally. The building was rigidly symmetrical, with externalized facades, a major divergence from the internalized monumentality of, for example, the mosques and madrasas of Islamic Persia, where courtyard facades with their ample iwans would be richly decorated in colorful tiles.

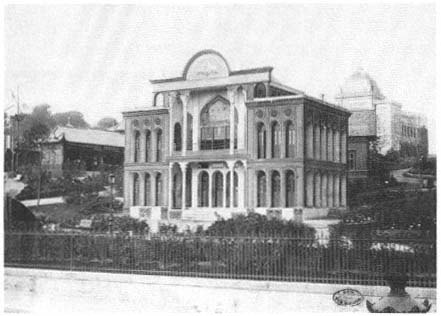

The Persian palace in 1878 (sometimes called the Palace of Mirrors) was noted not for its exterior, which incorporated random details from Isfahan's monuments, but for its main hall, which duplicated the Hall of Mirrors in the

Figure 78.

Persian pavilion, Vienna, 1873 (L'Esposizione universale di Viena, no. 5).

Ali Qapu Palace (Fig. 79). For visitors, this was the ultimate expression of Oriental luxury. A guidebook to the exposition stated that the grand salon, "with millions of pieces of glass adorning the stalactites of the ceiling," flashed like a huge diamond.[54] Another observer called the room enchanted, "a real salon from The Thousand and One Nights " that acquired an "absolutely magical" atmosphere when the candles were lighted.[55]

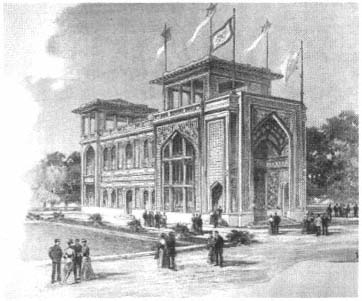

Iran made its greatest architectural statement in Paris in 1900 (Fig. 80). A French architect, Philippe Mériat, designed and supervised the construction of the Persian pavilion on the Rue des Nations for the Iranian government, which asked for a building modeled on the Madrasa Maderi Shah Sultan Husayn.[56] The exposition hall, however, did not rely solely on toe original model organized around a courtyard. In fact, the pavilion had four elaborate facades and no Interior courtyard; thus references to the original were restricted to particular elements. Moreover, the structure was topped by two colonnaded pavilions modeled after the Pavilion of the Forty Columns and the terrace of'Ali Qapu Palace in Isfahan. Visitors were dazzled by the octagonal columns carved in cypress; ceilings sculpted, painted, and gilded; and a floor of white marble.[57]

Figure 79.

Persian pavilion, Paris, 1878 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Département des

Estampes et de la Photographie).

FIigure 80.

Persian pavilion, Paris, 1900 (L'Esposizione universale

del 1900 a Parigi ).

The facade on the Rue des Nations reinterpreted the great portal of the original madrasa as a tall iwan whose vault was decorated with stalactites; the tiles defining the borders of the portal were green, pink, orange, and different shades of blue. The overall effect was one of "grandeur, elegance, and bright gaiety." It was reported to be such a "perfect reproduction" that one observer lamented the lack of Iranian plants and waterworks on the Rue des Nations.[58] The interior of the building contained both a "magnificently furnished" reception hall and an "immense bazaar," where agricultural, industrial, and artistic products were exhibited.[59] The Hall of Honor, reserved for Shah Muzaffar ad-Din, was reportedly of the "first rank." It was lighted by two large stained-glass windows. On one, a Persian lion was depicted; on the other, lines by a contemporary poet were inscribed, glorifying the role of France and the city of Paris in modern civilization.[60] To Europeans such an integration of long inscriptions into architecture was novel. One observer remarked in awe: "Every facade is a real banner. They wrote everywhere: on the tiles, on the walls, on the glass."[61]

The attention given to the design and execution of this pavilion indicates the changing relations between Iran and Europe. Following Egypt and the Ottoman Empire, Iran had joined the "train of Western civilization."[62] Its exposure to the West led to a redefinition of its identity. Like the architecture of other Islamic powers at the world's fairs, that of Iran looked back to the nation's heritage, reinterpreting it according to the principles of Western architecture.