Affinal Relations: The Lius and the Chuangs

As formidable as the Chuang lineage had become by the eighteenth century, its strength and influence was not based on kinship solidarity alone. Marriage strategies and descent were both used by elite households to serve their larger social and political ends. Alliance with other powerful families and lineages complemented kinship solidarity. The Chuangs thus developed close external affinal ties with the Liu lineage in Ch'ang-chou. Although prominent scholar-officials often preferred to build social networks based on more than local kinship, lineage organization, particularly through affinal ties, nevertheless remained a prominent feature in elite life. In the cases of the Chuangs and Lius, we can see how broader national level networks overlapped with local level lineage organizations and their interrelation in national and local politics.[34]

Unlike the Chuangs—whose migration to the Yangtze Delta can be

[33] See P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 18B.39a, and Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), ts'e 10, pp. 25a-26b. Liu Feng-lu's mother wrote a collection of poetry and took charge of her son's early literary training. See Wu-chin Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1929), 8.14a.

[34] James L. Watson, "Chinese Kinship Reconsidered," pp. 616-17. See also Ebrey, "Early Stages," p. 40n, and Hymes, "Marriage in Sung and Yuan Fu-chou," pp. 95-96 (both articles are published in Ebrey and Watson, eds., Kinship Organization ). Hymes cautions against overly contrasting strategies of alliance and descent. Cf. Dennerline, Chia-ting Loyalists , pp. 104-11, 113, for different views.

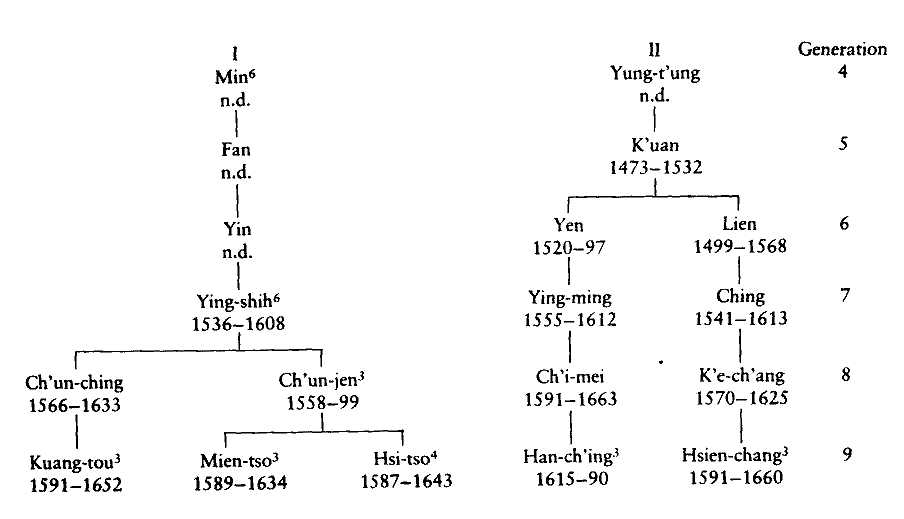

Fig. 8.

Major Segments of the Liu Lineage in Ch'ang-chou during the Ming Dynasty

traced to the twelfth-century advances of the Jurchen forces in north China—the Lius traced their origins in Ch'ang-chou to the mid-fourteenth century and the social and political convulsions that overtook the Lower Yangtze when rebel forces rose against Mongol rule. Contending armies struggled against Mongol forces and among themselves for control of the lucrative resources of the Mongol empire's richest region. One of these armies, led by Chu Yuan-chang, succeeded in establishing the Ming dynasty in Nan-ching in 1368.

Liu Chen, a native of the northern town of Feng-yang in He-nan Province, arrived in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture in 1356 in the service of one of the armies allied with Chu Yuan-chang. After aiding in the pacification of Ch'ang-chou, Liu stayed on for a decade, marrying and raising a son, Liu Ching. In 1366-67, Liu Chen left Ch'ang-chou to participate in military campaigns in Shan-hsi, leaving behind his son, who remained in Ch'ang-chou and transmitted the Liu family line in local society there. Although a military epochal ancestor for the Lius, Liu Chen never returned to Ch'ang-chou. Later investigations by the Lius in Ch'ang-chou revealed that Liu Chen had established yet another Liu family in Ta-t'ung, Shan-hsi, after he left Ch'ang-chou (fig. 8).[35]

Liu Ching passed the provincial chü-jen examination in 1400 and served as a county magistrate during the early fifteenth century, bringing the Lius to prominence in Ch'ang-chou society. His son, Liu Chün in turn became the chief ancestor for the three major branches of the Liu lineage in Ch'ang-chou, and the lineage became increasingly important in the late Ming. By comparison to the T'ang and Chuang lineages,

[35] Wu-chin Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1929), 1.13a, 3.la, and Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.1a-b.

however, the Lius were relative newcomers in Ch'ang-chou. They did not become prominent in elite local circles until, in the eighth and ninth generations, the first and second branches produced a distinguished crop of scholar-officials.

In the eighth generation, Liu Ch'un-jen, of the main branch (ta-fen ), became the first of the lineage to pass the national chin-shih examination, finishing eighteenth in the competition of 1592. Liu Ch'un-jen's sons, along with those of his younger brother Ch'un-ching (direct ancestor of Liu Feng-lu), counted among their ranks two chin-shih, one chü-jen, and two tribute students (kung-sheng; nominees of local schools for advanced study and subsequent admission to the civil service). The ninth generation was conspicuous for producing three imperial censors (yü-shih ) during the late Ming: Liu Kuang-tou (son of Liu Ch'un-ching); Liu Hsi-tso (son of Liu Ch'un-jen); and Liu Hsien-chang (son of Liu K'e-ch'ang), a member of the second branch of the lineage (fig. 9).[36]

Liu Hsien-chang, for example, had taken his chin-shih degree in 1637 and was politically active in the late Ming, participating in the meetings of the Fu She activists. Liu Hsi-tso, in addition to his government service, had begun a pattern of marriage alliances with the Chuangs in Ch'ang-chou by marrying his daughter to Chuang Yin (1638-78), son of Chuang Ying-chao in the prominent ninth generation of the second branch of the Chuangs (see list). Hsi-tso's younger brother, Liu Yung-tso, was among those who participated in the Tunglin movement. The intermarriages continued as follows (generation number is in brackets):

Liu | Chuang |

Hsi-tso's [9] daughter | m. Yin [10] |

I-k'uei [10] | m. daughter of Yu-yun [10] |

Lü-hsuan's [10] daughter | m. Tou-wei [12] |

Yü-i's [11] mother | née Chuang |

Wei-ning's [11] daughter | m. Pien [11] |

Hsueh-sun [13] | m. daughter of Ch'u-pao [13] |

Hsing-wei's [14] daughter | m. Fu-tan [15] |

[36] Wu-chin Yang-hu hsien ho-chih (1886), 17.44a. See also Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1876), 8.18a, 8.33a.

Lun's [14] son | m. daughter of Ts'un-yü [12] |

Lun's [14] granddaughter | m. Ch'eng-sui [14] |

Chung-chih's [15] granddaughter | m. Ch'ien [16] |

Chao-yang's [15] daughter | m. Ch'eng [15] |

Another important member of the pivotal ninth generation of the Lius (in the second branch) was Liu Han-ch'ing, who took his chü-jen degree in 1642 and became a chin-shih in 1649. Before his death, Liu Han-ch'ing compiled the first genealogical record of the Liu lineage, which was completed in 1689. Six subsequent revisions were made in 1693, 1750, 1792, 1855, 1876, and 1929. Han-ch'ing's son, Liu I-k'uei, married the eldest daughter of Chuang Yu-yun, who was Chuang Ying-chao's eldest son. We should add that Han-ch'ing's great-uncle Liu Ying-ch'ao earlier had arranged for a marriage between his eldest daughter and Chuang Heng, Chuang Ying-chao's elder brother. Thus, by the early Ch'ing dynasty, the seventh and eighth generations of the Lius and the ninth and tenth generations of the Chuangs had developed close marriage ties.[37]

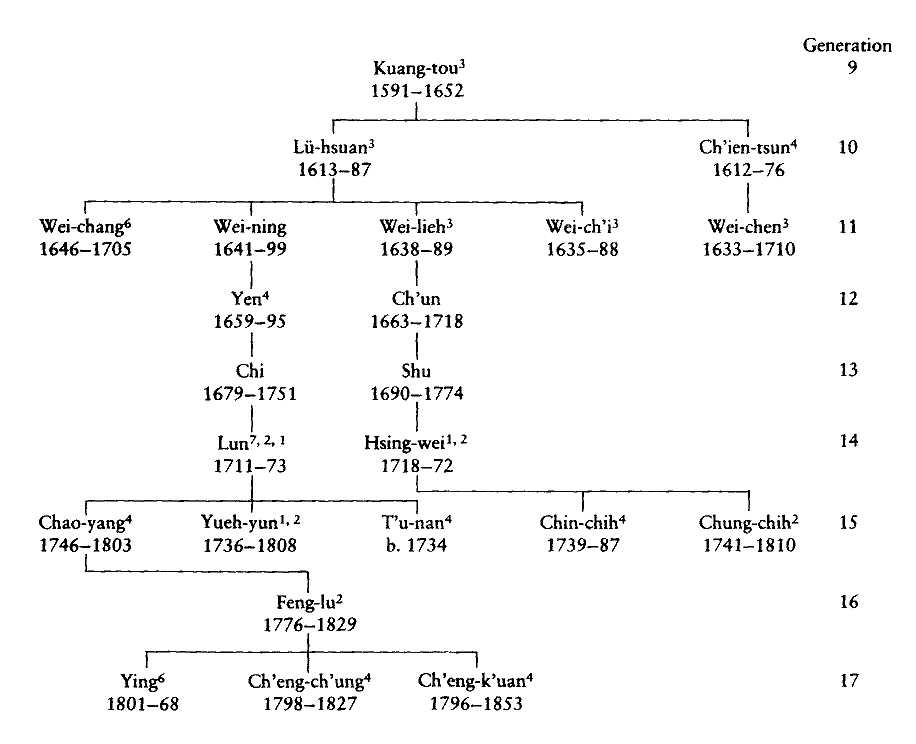

Liu Kuang-tou, in the main branch of the lineage, passed the chü-jen examination in 1624 (fig. 10). The following year he took the chin-shih degree in Peking. Involved in the up and down, factional nature of late Ming politics during the Tung-lin party's efforts to gain control of the imperial bureaucracy, Liu was appointed imperial censor, subsequently dismissed, and then reappointed as censor during a period of extreme bureaucratic corruption. Kuang-tou's examination success and high office—as important as they were in promoting his official career and the fortunes of the Liu lineage during the late Ming—were overshadowed by his remarkable behavior when Manchu armies, filled with Chinese mercenaries, launched their invasion of Ch'ang-chou in 1645.[38]

As a Ming dynasty censor, Liu Kuang-tou was bound by traditions of loyalty to the dynasty he served. The generation of 1644, which witnessed the demise of a native Chinese dynasty, had an established

[37] Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.1a-13a, 4.1a-2a, 4.14a-14b; (1876), 1.36b, 2.1a-2b, 4.1a-2a; Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), 5.34b, 5.43a-44b, 5.46b-47a; and Wu-chin Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1840), 3.20b. See also Chuang Chu, P'i-ling k'e-ti k'ao , 1.17b, 8.33a. Cf. Chin Jih-sheng, Sung-t'ien lu-pi, ts'e 1, p. 14a; Wu-chin Yang-hu hsien ho-chih (1886), 24.48b-49a; and Crawford, "Juan Ta-ch'eng."

[38] Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.13a-14a. See also Crawford, "Juan Tach'eng," p. 42.

Key: l Grand secretary

2 Hanlin academician

3 Chin-shih

4 Chü--jen

5 Fu-pang: supplemental Chü-jen

6 Tribute student

Fig. 9.

Major Segments of the First and Second Branches of the Lius during the Ming Dynasty

Key: 1 Grand secretary

2 Hanlin academician

3 Chin-shih

4 Chü-jen

5 Fu-pang: supplemental Chü-jen

6 Tribute student

7 Grand counselor

Fig. 10.

Major Segment of the Main Branch of the Liu Lineage during the Ch'ing Dynasty

ideology of "not being a servant of two dynasties" (pu erh-ch'en ). This ideology forbade an official—even a subject—in one dynasty to serve in another. Ming loyalists, who remained influential for the remainder of the seventeenth century, expressed their dissent through the Confucian imperative of loyalty..[39]

In contrast to celebrated Yangtze Delta Ming loyalists such as Ku Yen-wu and Huang Tsung-hsi, however, Liu Kuang-tou was among the first Confucian officials in the Lower Yangtze to urge submission to the conquering Manchus. Unlike the grandson (Liu Ch'ao-chien) of his cousin Liu Hsi-tso, who went into seclusion after the Ming collapse in south China, Liu Kuang-tou urged the surrender of the Chiang-yin county seat in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture, which became, along with Yang-chou and Chia-ting, a symbol of Ming resistance to the invading armies. Chiang-yin loyalists chose instead to hold out. Thousands perished when mercenary armies brutally subdued and sacked the city.

Victimized by late Ming factionalism, Kuang-tou seems to have had few qualms about deserting the Ming banner. Moreover, because Ming loyalist forces labeled him a traitor after the fall of Chiang-yin, Liu was quickly appointed county magistrate in Chiang-yin by Manchu authorities in the Yangtze Delta. Later he served the new Ch'ing dynasty as pacification commissioner (an-fu shih ) in his home area of Ch'ang-chou Prefecture. It is intriguing that Liu Kuang-tou became associated under Manchu rule with the reform policy of "equal service for equal fields" in Ch'ang-chou, a policy that late Ming reformers had been unable to implement..[40]

Whatever the ethical implications of Kuang-tou's behavior, the Liu lineage in Ch'ang-chou benefited for the duration of the Ch'ing dynasty. Liu Kuang-tou's line in the main branch of the lineage assumed central importance in lineage affairs, and in almost every succeeding generation, the Lius produced a scholar-official of national and local prominence.

Kuang-tou's son, Liu Lü-hsuan, for instance, took his provincial degree in 1642 and passed the capital examination of 1649, surviving the dynastic change barely missing a rung in the bureaucratic ladder of

[39] Mote, "Confucian Eremitism."

[40] See Wakeman's poignant account of Chiang-yin's fall entitled "Localism and Loyalism," pp. 43-85, esp. p. 54, for a discussion of Liu Kuang-tou. Hamashima, "Mim-matsu Nanchoku no So-So -Jo[*] sanfu ni okeru kinden kin'eki ho[*] ," pp. 106-108, discusses tax reform efforts during the Ming-Ch'ing transition. See also Wu-chin Yang-hu hsien ho-chih (1886), 28B.7b, and Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1876), 2.27a. Cf. Li T'ien-yu, Ming-mo Chiang-yin Chia-ting jen-min te k'ang-Ch'ing tou-cheng , pp. 16-34.

success. Similarly, Liu Han-ch'ing took his chü-jen degree in 1642 under Ming dynasty auspices; he had few hesitations in competing, successfully, for chin-shih status in 1649 under Manchu jurisdiction. Liu Kuang-tou's reputation as a turncoat and his sons' examination success under two dynasties did not ruin the status of the Lius in local society either. Lü-hsuan gave the hand of his eldest daughter to Chuang Tou-wei, a member of the twelfth generation of the prominent second branch of the Chuangs and grandson of Chuang Ch'i-yuan. Although some Chuangs were Ming loyalists, such matters were of secondary importance in the advancement strategies of the Lius and Chuangs..[41]

Both the Chuangs and Lius had come through the Ming-Ch'ing transition remarkably intact and relatively unaffected by ideological commitments to the fallen Ming dynasty. Only slightly less successful than the Chuangs in the examination system, Liu Kuang-tou's line could count ten chin-shih from the ninth through sixteenth generations. There were an additional nine chü-jen graduates in generations nine through eighteen. Among these nineteen officials, the Lius could point to five Hanlin academicians, three grand secretaries, and one grand counselor (see fig. 10).

The intermarriage between the two lineages, as we have seen, was already important during the Ming-Ch'ing transition. Arranged marriages were common during the Ch'ing dynasty, no doubt in part to solidify the local position of the Chuangs and Lius as gentry who had switched rather than fought. The high incidence of such intermarriages, from the ninth to fifteenth generations of the Lius and from the tenth to the sixteenth generations of the Chuangs, signals an intimate relation of affines that carried over from Ch'ang-chou local society to the inner sanctum of imperial power in Peking..[42]

In the tenth generation, the main branch of the Liu lineage began to place sons in the upper levels of the imperial bureaucracy. Beginning with the eleventh and twelfth generations, the Lius were honored with Hanlin Academy graduates. By the fourteenth generation, the Lius had "arrived," placing sons of that generation in the Grand Council and Grand Secretariat. They reached the pinnacle of national and local prominence by the middle of the eighteenth century, coinciding almost

[41] Chuang, P'i-ling k'e-ti k'ao , 8.7a, and Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.13b-14a; (1876), 4.14a-14b. See also Wu-chin Yang-hu hsien ho-chih (1886), 24.84a-84b, Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), 7.22b, and P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 1.23b, 3.25.

[42] Cf. Dennerline, "Marriage, Adoption, and Charity," p. 182.

exactly with the prominence of the Chuangs. Moreover, the key players in the Lius' and Chuangs' dual rise to power had affinal ties of great strategic importance, both for career advancement and as a guarantee for future success of the lineages..[43] The role of the two families from 1740 to 1780 may be summarized as follows (generation number is in brackets):

Chuangs | Lius |

Ts'un-y.ü [12] | Yü-i [11] |

Hanlin | Grand Secretariat |

Grand Secretariat | |

P'ei-yin [12] | Lun [14] |

Hanlin | Hanlin |

Grand Council | Grand Secretariat |

Grand Council | |

Yu-kung (from Kuang-chou) | Hsing-wei [14] |

Grand Secretariat | Hanlin |

Governor-general (Chiang-su) | Grand Secretariat |

Liu Yü-i, a chin-shih of 1712, was the first Liu from Ch'ang-chou to reach the Grand Secretariat. An eleventh-generation member of the second branch (erh-fen ) of the Lius, Yü-i served in the Hanlin Academy, where he worked on the Neo-Confucian compendium entitled Hsing-li ta-ch'üan (Complete collection on nature and principle) before holding the position of assistant grand secretary from 1744 until 1748. His mother came from the Chuang lineage. Liu Lun and Liu Hsing-wei, cousins in the main branch of the lineage that traced its prominence back to Liu Kuang-tou, took their chin-shih degrees in 1736 and 1748 respectively..[44]

Liu Hsing-wei, whose great-grandfather Wei-lieh and great uncles Wei-ch'i and Wei-chen had all been eleventh-generation chin-shih, served first in the Hanlin Academy. In 1765 he served as grand secretary in the Imperial Cabinet, along with Chuang Ts'un-yü who had been a grand secretary (in his second term) since 1762. Liu Hsing-wei's daughter was married into the Chuang lineage when she became the wife of Chuang Fu-tan, who was granted chü-jen status on the special

[43] Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1876), 2.80a-87b.

[44] Ch'ing-tai chih-kuan nien-piao , vol. 1, pp. 49-51, and Wu-chin Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1929), 4.16b.

examination of 1784 administered during the Ch'ien-lung Emperor's last southern tour. In addition, Hsing-wei's son, Liu Chung-chih, was admitted to the Hanlin Academy after passing the chin-shih examinations with honors in 1766. Chung-chih's granddaughter married Chuang Ch'ien, another in the prestigious second branch of the Chuang lineage, further cementing affinal ties between the Lius and Chuangs..[45]

Liu Lun's rise to prominence began when he finished first among more than 180 candidates on the special 1736 po-hsueh bung-tz'u examination ("broad scholarship and extensive words"; that is, qualifications of distinguished scholars to serve the dynasty) to commemorate the inauguration of the Ch'ien-lung Emperor's reign. Liu was subsequently appointed to the Hanlin Academy where he worked on a successive series of prestigious literary and historical projects, including compilation of the Veritable Records (Shih-lu ) of the preceding K'ang-hsi Emperor.

After serving as Hanlin compiler, Liu Lun's duties shifted from scholarship to politics. He rose to the presidency of a number of ministries after his appointment to the Grand Secretariat from 1746 to 1749. Liu Yü-i was concurrently an assistant grand secretary. In 1750 Lun was promoted to the Grand Council, where he served for much of the remainder of his career. As a grand counselor, Liu Lun was involved with initial efforts in the 1750s to put down the Chin-ch'uan Rebellion..[46]

As a senior colleague of Chuang Ts'un-y.ü, who served as a grand secretary more or less continuously from 1755 until 1773, Liu Lun presented the Chuangs with an ideal opportunity to strengthen the marriage links between the two lineages. Thus, when Chuang Ts'un-yü's second daughter, née Chuang T'ai-kung, married Liu Lun's youngest son, Liu Chao-yang, it represented a unification of the two most important lines within two extremely powerful higher-order lineages in Ch'ang-chou. Their combined influence extended into the upper echelons of the imperial bureaucracy. For all intents and purposes, the Chuangs and the Lius, via Chuang Ts'un-yü and Liu Lun, had engineered a marriage alliance of remarkable social, political, and intellectual proportions. Liu Lun's second son, Liu Yueh-yun, himself a Hanlin

[45] Ch'ing-tai chih-kuan nien-piao , vol. 2, p. 981. See also Chu-chi Cbuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), 7.36a-37b, and P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), 18b.38a.

[46] See the Chuan-kao of Liu Lun, no. 5741. See also Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.38a-40a; (1876), 2.81a-83b. Cf. Ch'ing-tai chih-kuan nien-piao , vol. 1, pp. 138-41, 609-14; vol. 2, pp. 965-68.

academician and grand secretary, would later compose a preface for the 1801 Chuang genealogy..[47]

Counting the Chuangs' twelfth generation and Lius' fourteenth generation as a single one within an affinal framework, we discover, more or less contemporaneously, five Hanlin academicians, four grand secretaries (including assistants), and one grand counselor within this inter-lineage social formation. Chuang Ts'un-y.ü and his younger brother, Chuang P'ei-yin, as secundus (1745) and optimus (1754) respectively on the palace examinations, both served as personal secretaries to the Ch'ien-lung Emperor early in their careers. In overlapping periods, Chuang Ts'un-yü, Liu Lun, and Liu Hsing-wei served in the Grand Council and Grand Secretariat. All three were affinally related.

When we include the clan relations that brought Chuang Yu-kung (see above), a Cantonese and optimus on the 1739 palace examination, into kinship ties with the Chuangs in Ch'ang-chou through the efforts of Chuang Ts'un-yü, the picture of powerful Ch'ang-chou lineages well-positioned in mid-eighteenth-century Peking politics is even more compelling. Chuang Yu-kung had served as assistant grand secretary (1746-47), education commissioner for the Lower Yangtze region (Chiang-nan hsueh-cheng, 1748, 1750-51), and governor of Chiang-su (1751-56, 1758, 1762-65) and Che-chiang (1759-62) provinces.

We have noted above that Yu-kung's appointment in Su-chou as governor of Chiang-su placed Ch'ang-chou (and the Chuangs) under Chuang Yu-kung's jurisdiction. Lineage interests, cemented through clan association with Yu-kung, could be expected to further, legitimately, the Chuang's position in their home province and prefecture while Yu-kung served there. It was hardly any accident, then, that Chuang Ts'un-yü urged Yu-kung to prepare a preface (dated 1761) for the Chuang genealogy, then being revised. The 1760s and 1770s marked the height of Liu and Chuang political power in the Ch'ien-lung era. The Ho-shen era of the 1780s would force them into careful retreat..[48]

The above account situates the reemergence of New Text Confucianism in Ch'ang-chou during the late eighteenth century within the lineage structures and affinal relations we have described. Liu Chao-yang, who

[47] See Freedman, Chinese Lineage, pp. 97-104. See also earlier citations from P'i-ling Chuang-shih tseng-hsiu tsu-p'u (1935), and Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792 and 1876).

[48] Ch'ing-tai chih-kuan nien-piao , vol. 1, pp. 138-41,609-14, 624-32; vol. 2, pp. 974-89.

married T'ai-kung (née Chuang), finished first on the special 1784 chü-jen examination administered by the Ch'ien-lung Emperor on the last of his six Grand Canal tours to the Yangtze Delta. The emperor was overjoyed that the son of one of his trusted advisors had done so well. Chuang Fu-tan (see above)—who had married the daughter of Liu Hsing-wei (Chao-yang's immediate uncle)—also passed that examination.

But Liu Chao-yang declined high office and contented himself with the life of a schoolmaster. Compared with his two more distinguished elder brothers—Liu T'u-nan, a 1768 chü-jen, and Liu Yueh-yun, a 1766 chin-shih, Hanlin academician, and grand secretary—Liu Chao-yang led a scholarly life in the company of his talented wife devoted to poetry, the Classics, mathematics, and medicine. As we shall see in chapter 4, Liu's "contentment" may have been enforced. His brothers' careers in the bureaucracy were cemented before the 1780s, which witnessed the rise of Ho-shen and his corrupt followers to prominence. In 1784, therefore, Liu Chao-yang faced an uncertain political career. His influential father-in-law, Chuang Ts'un-yü, was opposed to Ho-shen but was helpless to break Ho-shen's hold over the aging emperor. His powerful father, Liu Lun, had died in 1773. The Lius and Chuangs now had to tread very carefully in the precincts of imperial power. One wrong move and the cumulative efforts of generations of Lius and Chuangs to further the interests of their kin could be undone by an unscrupulous imperial favorite.

Liu Chao-yang's son, Liu Feng-lu, first studied poetry and the Classics under his mother's direction, before continuing his classical education in the Chuang lineage school. Women had considerable influence with their sons, husbands, and fathers, and were therefore important participants in affinal relations between lineages. Liu Feng-lu's mother, for instance, brought her son to her father, Chuang Ts'un-yü, for instruction at an early age.

Under Ts'un-yü's direction, Liu studied the Classics and other ancient texts before turning to Tung Chung-shu's Ch'un-ch'iu fan-lu (The Spring and Autumn Annals' radiant dew) and the Kung-yang Commentary based on Ho Hsiu's annotations. From his maternal grandfather, he absorbed the "esoteric words and great principles" (wei-yen ta-i ) that Chuang Ts'un-yü had stressed in his writings and teachings. Ts'unyü was so pleased with the progress of his precocious grandson that when Liu was still only eleven, Chuang remarked: "this maternal grandson will be the one able to transmit my teachings." The old man,

politically defeated in his last years, had toward the end turned to the New Text Classics to salvage a hope of victory over a corrupt age. His grandson would transmit the message to a post-Ho-shen age..[49]

As Chuang Ts'un-yü's major disciple, Liu Feng-lu, represented the culmination of the development of the Ch'ang-chou school. After Feng-lu, New Text Confucianism transcended its geographical origins to become a strong ideological undercurrent through the writings of Kung Tzu-chen and Wei Yuan. Both of the latter studied in Peking in the 1820s under Liu Feng-lu's direction when Liu was serving in the Ministry of Rites..[50]

In the next chapters, we shall begin to analyze the New Text ideas transmitted by Chuang Ts'un-y.ü and Liu Feng-lu to the Confucian academic world in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Here, we will conclude by observing that both Ts'un-yü and Feng-lu drew on their links to the cultural resources of their lineage organizations and interlineage connections in Ch'ang-chou to learn and transmit the set of classical ideas that later would be labeled as the "Ch'ang-chou New Text school." Liu Feng-lu, accordingly, was a product of Chuang lineage traditions that crossed over to the Liu lineage through the affinal relations that had been built up since the Ming-Ch'ing transition.

Although the achievements of the Liu lineage were substantial, the Lius were at a distinct disadvantage when compared with the Chuangs. The Chuangs had a higher level of scholarly achievement, as distinct from mere success in the examination system. Although Grand Counselor Liu Lun had published on a variety of subjects, the Chuangs and their longer tradition of classical scholarship proved to be the model that Liu Feng-lu, through his mother, would choose to follow. The two grandfathers, Liu Lun and Chuang Ts'un-yü, had sired a loyal son of the Liu lineage who would transmit the teachings of the Chuangs..[51]

Consequently, the intellectual direction of the eighteenth-century revival of New Text studies in Ch'ang-chou was indebted to Chuang

[49] Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1792), 2.39b; (1876), 2.81b-84a, 12.15a-18b, and Wu-chin Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1929), 12.19b. See also Ch'ing-tai chih-kuan nien-piao, vol. 2, pp. 997-1001, and Wu-chin Yang-hu hsien ho-chih (1886), A.26b-27a. Cf. Liu Feng-lu, Liu Li-pu chi , 10.25a-26b, on née Chuang T'ai-kung, and Dennerline, "Marriage, Adoption, and Charity," p. 182.

[50] See "Shen-shou fu-chün hsing-shu," by Wang Nien-sun (1744-1832), a major figure in the Yang-chou Hah Learning tradition, in Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1876), 12.55b. See also Kung Tzu-chen nien-p'u , p. 603, and Wang Chia-chien, Wei Yuan nien-p'u , pp. 30, 33n.

[51] For a list of publications by members of the Liu lineage, see Wu-chin Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1929), 8.12a-14a. See also Liu Lun, Liu Wen-ting kung chi .

and Liu lineage traditions and their affinal relations. During his years under Chuang tutelage, Liu Feng-lu formed close friendships with his cousins Chuang Shou-chia (1774-1828) and Sung Hsiang-feng (1776-1860). Chuang Ts'un-yü's teachings were thus carried on by two grandsons, Chuang Shou-chia and Liu Feng-lu, and a nephew, Sung Hsiang-feng, son of Chuang P'ei-yin's third daughter, who had married into the Sung family in nearby Su-chou. Each went on to stress different aspects of the teachings they received, which they applied to broadening the content of New Text studies..[52]

We turn now to the rise of the New Text tradition as a product of classical teachings and statecraft ideals that represented in part the continuing legacy, however diluted, of late Ming political agendas in Ch'ang-chou within the organizational framework of kinship networks drawn around the Chuang lineage. Internal descent strategies and external affinal relations with the Lius would successfully harbor activist Confucian political values that had survived among Ch'ang-chou literati despite the Ming debacle and the Manchu triumph.

[52] Chu-chi Chuang-shih tsung-p'u (1883), 8.30b-31a, 8.36a. See Chuang Shou-chia, She-i-pu-i-chai i-shu , "Shang-shu k'ao-i hsu-mu" (Preface), pp. la-2b, where he discusses his relationship with Liu Feng-lu; and Wang Nien-sun's biography of Feng-lu in Hsi-ying Liu-shih chia-p'u (1876), 12.55a-b.