Chapter Eight—

Writing Roughing It

The story of Samuel Clemens's remaining days in Buffalo intertwines with and eventually becomes the story behind the composition of his second big book, Roughing It . By his own account, he began work on his sequel to The Innocents Abroad in August of 1870 and was still revising and adding to it as late as October of 1871. During those fifteen months he probably produced more than two thousand manuscript pages, of which just three are extant today.[1] Over the course of that time, waves of energetic, sometimes frantic, composition alternated with troughs of torpor, distraction, and despair. There may even have been moments of calm, consistent, workmanlike productivity. But by and large, writing Roughing It was a struggle for Clemens: against the odds, which emphasized the unlikelihood of his producing a successful follow-up to a bestseller; against the Fates, which seemed determined to rain an endless stream of catastrophes down upon him; and against the elements of his own temperament, which were inclined from time to time to give way to self-doubt, insecurity, and guilt.

The germ of the book, the impulse to recollect and make literary matter of his western experiences, can be traced back at least as far as the "Around the World" letters Clemens began publishing in the Buffalo Express in the fall of 1869. Six of the eight letters he wrote for the series treated Nevada and California.[2] His imagination may have been further stirred by his writing a long congratulatory letter to the New York Society of California Pioneers on II October 1869: "If I were to tell some of my experiences, you would recognize Californian blood in me," he wrote the society. "Although

I am not a pioneer, I have had a sufficiently variegated time of it to enable me to talk pioneer like a native, and feel like a Forty-Niner."[3] He seems clearly to have had some western project or projects in mind when he wrote to his mother and sister in February or March of 1870 asking that they send him a file of his clippings from the Virginia City, Nevada, Territorial Enterprise ; the file arrived on 26 March 1870.

Quite some time earlier, however, Clemens was at least toying wth the idea of capitalizing in some way on the popularity of The Innocents Abroad . "I mean to write another book during the summer," he wrote Mary Fairbanks on 6 January 1870. "This one has proven such a surprising success that I feel encouraged." Later that month, just before his wedding, he wrote with the same easy assurance to his publisher, Elisha Bliss, "I can get a book ready for you any time you want it." As if to protect himself from the pressure such a promise might generate, though, he added, "but you can't want one before this time next year—so I have plenty of time" (22 January 1870). Bliss apparently responded with a combination of enthusiasm and his customary shrewdness to overtures of this kind on Clemens's part, and during the spring the two fenced rather languidly with one another about contracting for a second book. When it seemed likely that the newlyweds might travel to Europe, for instance, either for the sake of their own pleasure or in order to accompany Jervis Langdon on an excursion to restore his health, Clemens wrote, "I have a sort of vague half-notion of spending the summer in England.—I could write a telling book" (11 March 1870).

It was amid these circumstances that he sent for the "coffin" of clippings from the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise . Insofar as he and Bliss had any very definite notions at this time about the nature of his second book, those notions pretty clearly centered on his setting off on another round of foreign travels in order to write a sort of "Innocents Abroad II." It seems likely, therefore, that requisitioning the file of Enterprise clippings that arrived in late March had more to do with his having agreed earlier that month to edit a regular ten-page column for the Galaxy than with his intention to write a book.[4] Every early indication is that the second major work from Mark Twain was, like the first, to chronicle his encounter with the Old World, not the New. While Clemens was securing

and assessing those Enterprise clippings, in fact, Bliss evidentally put teasing aside and began pressing him in earnest about a European tour. On 1 April 1870 Clemens wrote Olivia's parents, "Bliss is very anxious that I go abroad during the summer & get a book written for next spring." Had Jervis Langdon's rapidly failing health not put such a trip out of the question, Clemens would probably have acted on his publisher's urging, since neither of them had come up with a better way of stimulating a follow-up to his best-seller, and set out to write a second Innocents Abroad . Only upon acknowledging his inability to do so did he hit, glancingly at first and without much fervor, upon the idea of turning west rather than east—to the past rather than the present, and to the internal world of recollected experience rather than the external world of accident and circumstance—in generating the matter for his second book.

On 29 May 1870 Clemens made his first explicit reference to the idea of writing a western book when he tentatively, perhaps playfully, agreed in a letter to accompany Mary Fairbanks and her family on a trip to California the following spring. "The publishers are getting right impatient to see another book on the stocks," he said, "& I doubt if I could do better than rub up old Pacific memories & put them between covers along with some eloquent pictures." The letter somewhat contradictorily juxtaposes the mention of his publisher's impatience against his expressed intention of waiting almost a full year to undertake the trip that would "rub up" the memories needed to produce the book. But it does indicate a willingness, at least, to draw from those "Pacific memories" in writing his second major work, if only because he doubts that he "could do better." These lukewarm, inconclusive musings about a second book persisted into June, when Clemens expressed the hope to Bliss that his flagging enthusiasm for the project, whatever its nature, would be restored by the late-summer vacation he and Olivia were hoping to take. "I like your idea for a book," he said, apparently in response to a suggestion that has since been lost, "but the inspiration don't come. Wait till I get rested up & rejuvenated in the Adirondacks, & then something will develop itself sure " (9 June 1870).

Clemens's uncertainty about the subject of his second book, no doubt amplified by the distractions he faced in coping with his

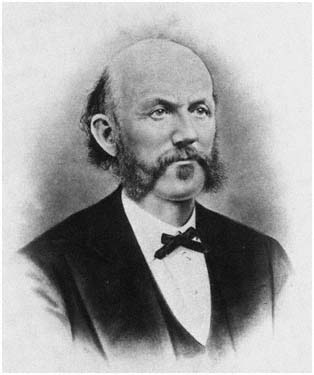

Elisha Bliss, Jr. (Courtesy Mark Twain Memorial,

Hartford, Conn.)

father-in-law's decline, became a matter of record when Bliss visited him in Elmira on 15 July and secured his signature on a contract. The agreement obligated him to produce a six hundred-page book for the American Publishing Company "as early as 1st of January next," but was quite unspecific as to what those six hundred pages might treat, stipulating only that Clemens produce for the company "a book upon such subject as may be agreed upon between them."[5] The matter of content was left open, it turned out, because even as he signed the document Clemens was unable to say unequivocally what he would write about. "The subject of it is a secret," he wrote to Orion later that day, "because I may possibly change it. But as it stands, I propose to do up Nevada & Cal., be-

ginning with the trip across the country in the stage." Roughing It came contractually and conceptually into existence in this conditional, provisional way. Dealing with an experienced publisher whose impatience and solicitude were carefully orchestrated, flushed with his own success and renown, and momentarily benefiting from a brightening in Jervis Langdon's condition, Clemens found his way into a bargain that stipulated his obligations much more clearly than it did the course he would follow to fulfill them.

In his 15 July letter to Orion he explained that "per contract I must have another 600-page book ready for my publisher Jan. 1," adding, "I only began it today." His subsequent correspondence, however, indicates that Clemens did not start work on Roughing It until about six weeks later. In a letter to his mother and sister dated 27 July, he described the contract for the Nevada and California book and said, "I shall begin it about a month from now." The postponement was very likely due to the strain of maintaining Jervis Langdon's sickroom vigil, but it may also reflect Clemens's difficulty in recalling events of a decade earlier. "Do you remember any of the scenes, names, incidents or adventures of the coach trip?" he had asked Orion, "for I remember next to nothing about the matter" (15 July 1870). Even had he planned to begin work on the book sooner, those plans would necessarily have been set aside when his father-in-law died on 6 August. Langdon's long decline, which might under other circumstances have helped members of his family prepare for the worst, instead preyed upon their incautious optimism and so relegated them to a deep and troubled mourning. Back in Buffalo by the end of August with Olivia and her mother, Clemens wrote his sister, Pamela, "Livy cannot sleep since her father's death—but I give her a narcotic every night & make her" (31 August 1870). His own mourning and ministrations had to be interrupted or cut short in order to allow him to produce copy for his October "Memoranda" column, due in early September. Having excused himself from his Galaxy obligations for the preceding month because of Langdon's illness, he found himself in a position where he simply had to resolve to work.

Apparently it was that resolution—intensified, perhaps, by the recognition that his I January book deadline was now only four months away—that finally led him to begin Roughing It . He was further stimulated when he received the record of the stagecoach

trip he had requested from Orion. "I find that your little memorandum book is going to be ever so much use to me," he wrote, "and will enable me to make quite a coherent narrative of the Plains journey instead of slurring it over and jumping 2,000 miles at a stride."[6] The big western book was at last under way. "I am just as busy as I can be," he wrote his sister on 31 August, "am still writing for the Galaxy & also writing a book like the 'Innocents' in size & style.... I have got my work ciphered down to days , & I haven't a single day to spare between this & the date which, by written contract I am to deliver the MSS. of the book to the publisher." On 2 September 1870 he reported to Mary Fairbanks, "I have written four chapters of my new book during the past few days," and on 4 September he bragged to Bliss, "During the past week have written first four chapters of the book, & I tell you the 'Innocents Abroad' will have to get up early to beat it.—It will be a book that will jump right strait into a continental celebrity the first month it is issued."

Ciphering and enthusiasm, though, were no proof against the misfortunes that plagued the book's early composition. Just as Clemens was writing these initial chapters, he and his wife were paid a visit by Emma Nye, a girlhood friend of Olivia's, who was stricken seriously ill shortly after arriving in Buffalo. With her parents off vacationing in South Carolina, responsibility for their guest's care fell to the Clemenses. On 7 September Clemens wrote Ella Wolcott, an Elmira friend of the Langdons', "Poor little Emma Nye lies in our bed-chamber fighting wordy battles with the phantoms of delirium. Livy & a hired nurse watch her without ceasing,—night & day." On 9 September he told Orion, "I have no time to turn round. A young lady visitor (schoolmate of Livy's) is dying in the house of typhoid fever ... & the premises are full of nurses & doctors & we are all lagged out." Olivia, who had yet to get over the shock and wearying ordeal of her father's dying, exhausted herself at yet another sickbed, and Clemens watched helplessly as his wife's strength and their patient's life ebbed. The end came as he had foreseen. "Miss Emma Nye lingered a month with typhoid fever," he wrote Mary Fairbanks, "& died here in our own bedroom on the 29th Sept" (13 October 1870).

Almost four decades later Clemens remembered Emma Nye's last days as being "among the blackest, the gloomiest, the most

The Map of Paris as it appeared in the November Galaxy.

(Courtesy Mark Twain Papers, The Bancroft Library)

wretched of my long life," but he also regarded "the resulting periodical and sudden changes of mood in me, from deep melancholy to half insane tempests and cyclones of humor," as standing out among his life's principal "curiosities."[7] For all its manifest and indisputable wretchedness, September 1870 was a time of quirky, manic productivity for Clemens. Even with his Express obligations in abeyance, he was driven by his Galaxy and book deadlines to a frenzy of creative energy whose sources were somewhere between desperation and whimsy and whose most notable consequence was his famous "Map of Paris," a parody of the military maps many periodicals were then publishing in connection with their accounts of the Franco-Prussian War. "During one of these spasms of humorous possession," he later recalled, "I sent down to my newspaper office for a huge wooden capital M and turned it upside-down and carved a crude and absurd map of Paris upon it, and published it, along with a sufficiently absurd description of it, with guarded and imaginary compliments of it bearing the signatures of General Grant and other experts."[8] The map appeared in the Express on 17 September and 15 October 1870, was reprinted with a bit more elaboration in the November Galaxy , and directly became a minor national sensation. Among its admirers was Schuyler Col-

fax, vice president of the United States, who wrote Clemens on 26 September, "I have had the heartiest possible laugh over it, & so have all my family."[9] The map's patent absurdities—the inclusion, for example, not only of Verdun and Vincennes but also of Omaha, Jersey City, and the Erie Canal—and execrable execution were perfectly set off by Mark Twain's transparent vanity over its supposed brilliance and indisputable uniqueness. The map is a telling manifestation of the internal skirmishing Clemens's impulses were conducting in the wake of Jervis Langdon's death and during the course of Emma Nye's dying. Its botched, infantile look and general silliness aptly reflect his knack for finding imaginative freedom and release from the draining cares of adulthood through childish forms and perspectives. Mourning the loss of one patient, doing his part to nurse another, afraid that his wife was about to break with grief and anxiety, he regressed to a safer—and funnier—place; or rather he was taken there by "spasms of humorous possession" over which he claimed no control and for which, therefore, he could not be held responsible.

A similar release may well have accompanied Clemens's early work on the Roughing It manuscript, particularly if that manuscript essentially resembled the book as it was eventually published (a likelihood to be discussed below). For it, too, offers a childish, or puerile, perspective on the world, the outlook of a narrator who opens by allowing that he was "young and ignorant" when he began his western adventures, at least in part because he "never had been away from home."[10] The first of these claims distorts the actual circumstances of Clemens's history and the second wholeheartedly misrepresents them. When he accepted his brother's invitation to head west in the summer of 1861, he was a twenty-five-year-old man who had already seen and lived for a time in such places as St. Louis, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Cincinnati, and who had gained a wide experience of the Mississippi Valley during three years as an apprentice and steamboat pilot. The Roughing It narrator, however, is a callow, inexperienced innocent in those opening chapters, a wide-eyed adolescent who anticipates a string of western adventures as breathlessly as Tom Sawyer would, who refers to himself as a "stripling" (RI , p. 96), who is on one occasion supposedly mistaken for a child (RI , p. 17), and who is carried away from "the States" in a stagecoach

that seems to him "an imposing cradle on wheels" (RI , p. 47). The regressions in the early going of Roughing It , moreover, operate on other levels as well. The trip west seems, at least at the outset, a flight from civilization to conditions more primitive and rudimentary, from relative order to something approaching anarchy, from the rules of decorum and the forms of polite address to the unrestraint of practical usage and the vigor of colloquial language, from the tame to the wild. Aboard their hurtling stagecoach, the narrator and his brother shed their clothes, stow their unabridged dictionary, and revel in a "wild sense of freedom" (RI , p. 66); the coach itself undergoes a parallel transformation, eventually devolving to a mud wagon, its horses replaced by mules.

In beginning his book, Clemens was clearly tapping into and in his way extending the myth of the West, but on a much more personal level he was also discovering in the unfettered, childlike joy of "those fine overland mornings" a refuge from the grown-up burdens that weighed upon him in the early fall of 1870. "We bowled away and left 'the States' behind us," he wrote: "It was a superb summer morning, and all the landscape was brilliant with sunshine. There was a freshness and breeziness, too, and an exhilarating sense of emancipation from all sorts of cares and responsibilities, that almost made us feel that the years we had spent in the close, hot city, toiling and slaving, had been wasted and thrown away" (RI , p. 47). Like the map of Paris, the opening chapters of his California book offered Clemens the tonic of boyish self-indulgence and release. His early enthusiasm for the project and his ability to stay with it very likely derived from his exploiting it as a means of escape. Vicariously sloughing layers of respectability and obligation, he found in the writing a form of emancipation not only from the close, hot confinement of Buffalo, where his dreams of perfect domestic contentment were fast giving way to a nightmare reality, but also from the specters of age, disease, and mortality that seemed destined to harry him there and from the burdens of gentility and the confinements of newspaper and magazine work that had become his lot.

So it is not altogether surprising that Clemens managed to make some progress on the Roughing It manuscript in September 1870, even as Emma Nye was losing her battle with typhoid fever in his home. In the middle of the month he wrote to Hezekiah L. Hos-

mer, postmaster of Virginia City, informing him that he was "now ... writing a book" and that "the Overland journey has made six chapters of it thus far & promises to make six or eight more" (15 September 1870). The letter is significant not only because it indicates that Clemens had written chapters 5 and 6 between 4 and 15 September but also because it requests from Hosmer information about Slade, the division agent to whom chapters 10 and 11 of the book in its present form are entirely devoted.[11] The timing of the request suggests that the arrangement and numbering of the early chapters in the manuscript were essentially similar to those of the first edition. That is, Clemens raised an issue at the end of manuscript chapter 6 that he carne to treat in book chapter 10. The overland journey, as it turned out, eventually occupied the first twenty chapters of Roughing It , not twelve or fourteen as Clemens here speculates.

By 19 September Clemens could report to Bliss that he had "finished 7th or 8th chap of book to-day ... —am up to page 180—only about 1500 more to write." It had taken him three weeks, under trying circumstances, to produce these 180 manuscript pages; it would be months before he would be able to sustain even this modest pace again. His attention may have been overtaken at this point by the demands of Emma Nye's illness, but it may also, and necessarily, have been diverted by his having to prepare "Memoranda" for the November Galaxy in time for his early October deadline. Nothing in that November column approached the antic foolery of the map of Paris, which accompanied it. The "Memoranda" opened with a long encomium to John Henry Riley, a cohort from Clemens's California and Washington days, and included two further letters from Ah Song Hi, "Goldsmith's Friend," depicting the plight of the Chinese in the courts of San Francisco. There were also a five-column "General Reply" to aspiring writers from a seasoned, savvy Mark Twain, and the usual gathering of saccharine verse and other literary overindulgences sent him by correspondents. Each of these pieces reinforced Twain's stature not only as a sage and serious adult but also as a critic in conspiracy with his readers to trim the excesses of unenlightened sentimentality. They were set off by "A Reminiscence of the Back Settlements," in which a vernacular speaker, an undertaker, rhapsodizes about an especially agreeable corpse he has just had the pleasure of

interring. "There's some satisfaction in buryin' a man like that," he says. "You feel that what you're doing is appreciated. Lord bless you, so's he got planted before he sp'iled, he was perfectly satisfied." Perhaps Clemens's frustration with the dead and the dying led him to publish this "Reminiscence," which otherwise seems a particularly inappropriate and insensitive performance in light of his circumstances and Olivia's in the early fall of 1870. Perhaps his experiment with a vernacular narrator served as a kind of warmup or preparation for Roughing It . The garrulous, unsentimental undertaker of "A Reminiscence," at any rate, could have held his own with the "sociable heifer" who makes her appearance in chapter 2 of Roughing It , and would have been just the man to conduct Buck Fanshaw's funeral in chapter 47.

It would be some time, though, before Clemens could turn his full attention back to the book. Olivia collapsed shortly after Emma Nye's death in late September, exhausted by the month-long sickbed vigil and the strain of her first pregnancy. Mindful that his wife had been something of an invalid for much of her adolescence, Clemens anxiously monitored her slow recovery. She was still too weak on 12 October to attend the wedding of her brother, Charles, to Ida Clark in Elmira. On 13 October Clemens wrote Bliss that he had recently been able to return to the manuscript. "I am driveling along tolerably fairly on the book," he said, "getting off from 12 to 20 pages (MS.) a day." But the demands of his literary obligations, augmented by his worries at home, were growing burdensome. "The reason I haven't written before," he admitted the same day in a letter to Mary Fairbanks, "is because I am in such a terrible whirl with Galaxy & book work that I am so jubilant whenever each day's task is done that I have to dart right off & play—nothing can stop me. I never want to see a pen again till the task-hour strikes next day."

An important change had taken place, not in the big western book, but in Clemens's attitude toward it, and toward himself. It had become work , and he the harried worker. No longer a lark or an escape, it was an incessant daily obligation—an obligation, moreover, bearing a deadline he could not hope to meet. And he was no longer the world-class raconteur, the darling of senators and congressmen, tossing off another six hundred-page best-seller in a few carefree months, but a drudge and perhaps even a fraud,

straining to produce by tedious effort and under grim circumstances the kind of thing he wished to believe he could turn out in a fit of happy inspiration. As the fall of 1870 deepened, so did Clemens's experience of the slow, anxious, frustrating toil that was so much at odds with the widely held and assiduously perpetrated image of the offhand, drolly spontaneous Mark Twain. His Galaxy "Memoranda," which he originally undertook as an outlet for "fine-spun stuff" and an antidote to the grind of newspaper work, had grown arduous as well. Five days after telling Mary Fairbanks of the terrible whirl he was in, Clemens warned Galaxy co-editor Francis P. Church, "Sometimes I get ready to give you notice that I'll quit at the end of my year because the Galaxy work crowds book work so much" (18 October 1870).

It was in this frame of mind that Clemens ground out his "Memoranda" for the December 1870 Galaxy . The main feature of the column and its leadoff piece, "An Entertaining Article," is a densely humorless review of The Innocents Abroad which Clemens attributed at the time to an English critic but later revealed he had written himself. The point of the exercise, by this time a familiar point to Mark Twain's Galaxy readers, is to hold up to ridicule those people too opaque or too much in earnest to get a joke or to penetrate even the most transparent irony. It was in keeping, then, with Twain's ongoing endeavor to challenge and educate his public in the matter of appreciating strategies and subtleties important to the humorist. It is accompanied by several other pieces that in one way or another also touch upon a writer's role or prerogatives or frustrations: "Running for Governor," for example, points up the press's willingness to resort to slander in its biased coverage of political campaigns. "The 'Present' Nuisance" attacks the practice common among tradesmen of giving newspaper editors merchandise in return for free advertising in the form of favorable "notices." In it Twain quite disingenuously says, "I am not an editor of a newspaper, and shall always try to do right and be good, so that God will not make me one." Finally, among these writer's laments, "Dogberry in Washington" lodges a complaint against the Buffalo postmaster who misinterprets an inscrutable postal regulation in such a way as to prohibit an author's sending his manuscripts through the mail at a reduced rate. Twain resolves

Langdon Clemens.

(Courtesy Mark Twain Memorial, Hartford, Conn.)

to take no action against this "misguided officer," but, perhaps with the vigilante justice of Roughing It fresh in his mind, says, "If he were in California, he would fare far differently—very far differently—for there the wicked are not restrained by the gentle charities that prevail in Buffalo."

Soon, however, the Galaxy , the Express , and even the book would seem only petty distractions. On 7 November 1870 Olivia gave birth to the Clemenses' first child, Langdon, prematurely. For a time her health and the baby's life were in such jeopardy that Clemens could think of little more than his anxiety for the two of them. As he did, it registered with him that his dainty palace in Buffalo, despite its particular graces and the "gentle charities" that operated in that city, had become a source of torment rather than

satisfaction. On 11 November 1870 he vented some of his worry and desperation in a letter to Orion:

I am looking for heavy bills to come in during the next few weeks—a four or five hundred-dollar doctor's bill, a sixty-dollar nurse bill, a hundred & seventy-dollar sleigh-bill, a two-hundred dollar life-insurance bill, a three-hundred dollar carpenter's bill, & a dozen or two of twenty-five dollar debts, & we owe the servants seven hundred dollars which they can call for at any time—& I am sitting still with idle hands —for Livy is very sick & I do not believe the baby will live five days.

It had been just four months since Clemens, flush with a sense of his own power, had signed what he thought was a fat contract with Elisha Bliss to produce a fat new work designed to capitalize on his swelling popularity. All things had seemed possible, including the restoration of his father-in-law to health and the writing of "a book like the 'Innocents' in size & style" by the turn of the new year. Now, his life a turmoil and his work in disarray, his responsibilities seemed about to overwhelm him. As the late fall drew on he temperamentally careened between poles of giddiness and despair, and the Roughing It manuscript slipped into twilight.

In letters he wrote during the summer of 1870, Clemens often observed that his deadline for completing the California book was I January 1871. He makes no mention of that deadline, however, after 15 September, a circumstance that suggests his willingness to forget or ignore it once the work of composition began. The Roughing It contract is somewhat equivocal on the matter, stipulating that Clemens was to submit the completed manuscript to his publishers "as soon as practicable, but as early as 1st January next if they ... shall desire it."[12] Perhaps in the hope that the American Publishing Company might suppress any such desire, Clemens kept Bliss well informed of his domestic tribulations throughout the fall, treating him more like a confidant than their mutual wariness would otherwise have made likely. He also managed in November to secure a spot for Orion on Bliss's staff as editor of a house organ called the American Publisher . Bliss was pleased to secure Orion as a kind of hostage to his brother's loyalty and to develop an opportunity to exploit his name. Clemens once remarked that Bliss's purpose in hiring Orion was to keep him—that is, Clemens himself—from "whoring after strange gods."[13] For his part, Clemens may have liked the idea of placing an insider in

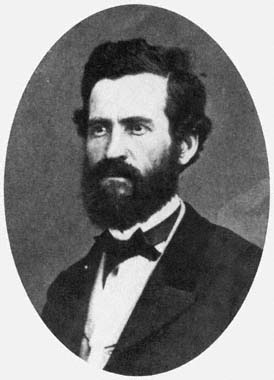

Orion Clemens. (Courtesy Mark Twain Papers,

The Bancroft Library)

Bliss's firm to look after his interests and to plead his case when, for example, he sought to extend a deadline.

By the end of 1870 Clemens had moved all members of his immediate family to the East—his mother, his sister, and his sister's children to Fredonia, New York, in April, and his brother and sister-in-law to Hartford in November. As he did so, ironically, he was becoming increasingly unsettled in Buffalo. The baby survived his first five days, but he did not grow strong. Olivia's hold on health was tenuous. The Express , which had long since ceased to exert any real attraction for Clemens, had come to claim little hold even on his attention or loyalty. On 26 November 1870 he wrote to Charles Henry Webb, "I never write a line for my paper, I do not see the office oftener than once a week, & do not stay there an hour at any time." His January 1871 "Memoranda" showed to

what extent his work for the Galaxy had likewise grown labored and uninspired. Its leading piece showcased a crude Twain engraving of King William III of Prussia, executed after the fashion of the map of Paris and amounting to no more than a knockoff or plagiarism of that earlier success. The sketches that followed it largely substantiate his later observation that few things are drearier than "to be a monthly humorist in a cheerless time."[14] If Clemens's hands were no longer idle as winter set in, neither had they taken a purposeful hold on a single enterprise. Rather than working to meet the chief obligation before him, he chose in the last months of 1870 to spawn a bewildering array of new projects which served, whether intentionally or not, to distract him, and sometimes even Bliss, from his failure to make headway in Roughing It .

The most spectacular of these schemes was his proposal, made in November, to write a book about prospecting for diamonds in South Africa, where strikes and claims were making news that sounded an ever-resonant chord in Clemens. The idea was to send a surrogate—a less taciturn, more dependable version of Professor Ford—to the diamond fields to gather facts and impressions, which Mark Twain would then convert to a thick, profitable book. "That book will have a perfectly beautiful sale ," he wrote Bliss, asking for a 10 percent royalty and claiming that he had already found "the best man in America" to send to Capetown. His enthusiasm for the project stopped just short of frenzy: "Say yes or no quick, Bliss, for this thing is brim-full of fame & fortune for both author [and] publisher. Expedition's the word! I don't want any timidity or hesitancy now" (28 November 1870). His "best man" was John Henry Riley, the same Riley to whom he had devoted four columns of praise in his November "Memoranda." In a long, importunate letter of 2 December, Clemens tried to pry Riley loose from his commitments in Washington. "This thing is the pet scheme of my life," he wrote. "I urge upon you, 'Expedition's the word!' Clear out now , & let us publish the FIRST book & take the richest cream.... But hurry , now. There is no single moment of time to lose. If you could start now , it would be splendid." Clemens knew his man, having said of him in the November Galaxy , "He will put himself to any amount of trouble to oblige a body." Riley gave way to this assault and, with Bliss not only concurring but issuing him an advance of $1,500, set sail on 7 January 1871.

The diamond-book enterprise epitomizes the feverish scheming that overtook Clemens during the winter of 1870–71. Frustrated by illness, misfortune, and perhaps by the vagaries of his own unruly talent, he seems to have sought reassurance that he was both a popular writer and a promising entrepreneur by conjuring up and committing himself to a series of literary speculations, all of them taking precedence at least for a time over the Roughing It manuscript. Unable or unwilling to attend to the work before him, he went on a spree of contract signings that may have bolstered his ego at the expense of his common sense and whatever remained of his peace of mind. The diamond-book idea was only the sparkling tip of that speculative iceberg. Moving on another front during this troubled winter, he agreed with Isaac Sheldon, publisher of the Galaxy , to produce a pamphlet which eventually appeared as Mark Twain's (Burlesque) Autobiography and First Romance . When it was all Bliss could do to contain his consternation over this seeming defection, Clemens contracted with him in mid-December to compile another book of short pieces for almost immediate publication. "To-day I arranged enough sketches to make 134 pages of the book," he wrote Bliss on 22 December 1870. "I shall go right on till I have finished selecting, & then write a new sketch or so." By 3 January 1871 he was pressing Bliss hard on this latest undertaking: "Name the Sketch book 'Mark Twain's Sketches ' & go on canvassing like mad. Because if you don't hurry it will tread on the heels of the big book next August." The "big book," of course, was Roughing It ; this letter indicates that Clemens still hoped somehow to complete the Roughing It manuscript in time to allow for its August 1871 publication.

All together, then, by the turn of the new year Clemens had pledged himself to produce a substantial volume of sketches for Bliss (to appear in the late winter or early spring), a pamphlet for Sheldon (to appear in March), a six hundred-page western book for Bliss (to appear in August), and another six hundred-page work, also for Bliss, on the African diamond fields (to appear, as Clemens wrote Riley, on "Feb. 1, 1872, & sweep the world like a besom of destruction" [2 December 1870]). All the while he had to prepare his monthly "Memoranda" columns and make some show at fulfilling his editorial obligations to the Express . In Clemens's mind, Mark Twain had somehow become an enterprise of

vast proportions, a literary fabricating plant modeled on the prevailing industrial strategies of bulk processing and mass production. Whatever else these schemes may have accomplished, they seem to have supplanted in Clemens's imagination the notion of the writer-as-inspired-artist with that of the writer as manager or processor. While there is considerably less magic or mystery in the latter conception than in the former, there is also less isolation and pressure. What these new projects had in common, whether paste-ups of new sketches and old or retellings of someone else's diamond-field escapades, was that they diverted their would-be author from the awful obligation of having miraculously to invent the California book. Their sheer number, though, destined them to stymie rather than soothe the frantic conjurer.

Something had to give. By the end of a few months, almost everything had. Sheldon got and printed his pamphlet by mid-March 1871, and the Galaxy publishers continued to receive "Memoranda" until Clemens had fulfilled his contract in April, but all else slid to confusion. Bliss convinced Clemens that to put a book of sketches on the market would be to jeopardize sales of the still popular Innocents Abroad . Clemens deferred to this reasoning and to Bliss's subsequent postponements as well, with the consequence that Mark Twain's Sketches, New and Old remained unpublished until 1875. The diamond book proved to be not only a failure, but a failure bearing the cast of tragedy. Riley performed dutifully, often under difficult circumstances. "Your letters have been just as satisfactory as letters could be," Clemens wrote him on 3 March 1871. But by the time Riley returned from his long odyssey, Clemens was preoccupied with other projects, and the diamond book, together with Riley himself, was left to languish. When Riley died of cancer of the mouth in September of 1872, unbidden and unvisited by Clemens, the book died with him.[15]

Roughing It proved vulnerable to both the pipe dreams and the vnightmares of early 1871. In a frenzy of enthusiasm for the book, perhaps after several weeks of having neglected it, Clemens wrote Bliss on 27 January, "Tell you what I'll do, if you say so. Will write night & day & send you 200 pages of MS. every week (of the big book on California, Nevada & the Plains) & finish it all up the 15th of April if you can without fail issue the book on the 15th of May.... I have to go to Washington next Tuesday & stay a week,

but will send you 150 MS pages before going, if you say so." This is a big promise, even for a man given to making big promises, as Clemens indisputably was, particularly at this moment in his life. No evidence suggests that he had yet experienced a two hundred-page week in working on the Roughing It manuscript. The record established by his correspondence, in fact, implies that he may not have written a total of two hundred manuscript pages since he began the book five months earlier in late August. Whether or not he could have delivered on such a promise, however, was destined to become an irrelevant question. Within a few days of Clemens's writing this letter, his grand schemes came crashing down around him as his wife again collapsed, seriously ill. The diagnosis was typhoid fever.

Clemens's February 1871 "Memoranda," which he would have submitted to his publishers just before this latest calamity, included a piece entitled "The Dangers of Lying in Bed," whose humor depended on the argument that since many more accidents occurred in the home than on the road, people had a much greater need for accident insurance when they were at rest than when they were in motion. "THE PERIL LAY NOT IN TRAVELLING," its astonished author exclaims, "BUT IN STAYING AT HOME." He continues, "my advice to all people is, Don't stay at home any more than you can help; but when you have got to stay at home a while, buy a package of those insurance tickets and sit up nights. You cannot be too cautious." Although it is hardly likely that he meant this as a veiled commentary on his own home life in Buffalo, it was an observation that came abundantly to be borne out by his subsequent experience. For as long as they lived in Buffalo, at least, home was not a safe place for Samuel and Olivia Clemens. During their courtship Clemens took particular pleasure in promulgating a vision of domestic life that stressed shelter, security, repose, and contentment. The "great world" might do its worst, he had written Olivia, "we will let it lighten & thunder, & blow its gusty wrath about our windows & our doors, but never cross our sacred threshold" (12 January 1869). Two years later he stood in the ruins of that dream. Married life offered no special protection against the world's tumultuous thunder, and in fact brought its own burdens of care and vulnerability. The heft of those burdens might eventually strengthen and deepen Mark Twain, but at the time, in early 1871,

it all but crushed him. For months Clemens had needed a chance to relax and find his bearings in Buffalo, both personally and professionally, after a spring and summer of uncertainty, distraction, and loss. Instead the fall brought further and even more dire calamities. When Olivia fell ill with typhoid in the dead of winter, just as their first married year was ending, he found himself at his wit's end. There would be no writing a big book now while the nightmare continued; there would be no writing at all.