Four

New Uses for Popular Culture

The highest note comes oft from basest mind,

As shallow brookes do yeeld the greatest sound.

Sir Philip Sidney, The Lady of May

The restrictions on professional participation that resulted from bureaucratic antimodernism and war-tightened purse strings encouraged popular participation in mass festivals during 1919. The pressing matter of survival diverted officials' attention from holidays, and the initiative sometimes made it to other hands. The popular spirit that had inspired Rousseau, Rolland, Lunacharsky, Kerzhentsev—even Wagner—finally infiltrated revolutionary festivals.

People's theater (narodnyi teatr ) had been a beacon for nineteenth-century liberalizers; no mere artistic phenomenon, it was a rhetorical icon for the creative energies that common people would manifest once liberated from tsarist oppression. The passion of the advocacy often obscured the phrase's muddled meanings. It could mean folk theater, specific to peasant culture; theater where peasant amateurs performed the classics; theater taken directly to the lower classes with the didactic strain typical of playwrights like Leo Tolstoy; popular theater of the urban masses; state-run theaters like the prerevolutionary People's Houses (sponsored by the imperial family or temperance groups), with a special "people's" repertory—fairy plays and operetta; classics on the order of Sophocles, Shakespeare, or Molière, which some fancied to

represent the spirit of an entire people; or even pan-national theater, as envisioned by Ivanov. Proletkultists were joining a hoary debate, and their contribution was not the already-old notion of popular participation but an emphasis on its class nature and a rejection of precedent.

Intellectuals rarely acknowledged the existence of a truly popular theater: the balagany and puppet booths of the holiday fairground. Russian popular culture seemed too vulgar and too familiar to most Russian intellectuals, and they ignored its distinct features in their sincere quest for a people's culture. The prejudice eluded political pigeonholing. Most older Bolsheviks considered high culture good, popular culture pernicious. Lenin wanted to replace the popular block prints (lubki ) he despised with cheap reproductions of art classics.[1] Lunacharsky, who saw a continuing role for fairground culture, preferred to co-opt its antiauthoritarian streak:

Long live the jesters of his Majesty the Proletariat! Although jesters once told tsars the truth, . . . they were still slaves. The jesters of the proletariat will be its brothers, . . . keen and eloquent advisers.

Why shouldn't Petrushka or another herald of popular opinion appear on the fairgrounds, urban squares, or at our rallies as a beloved character who could exploit the inexhaustible resources of popular humor? . . . Surely [that humor] will be permeated with the caustic humor that animates the revolution's destructive side.[2]

Even Blok, Meyerhold and Evreinov, who welcomed popular culture, looked mostly to Western variants: the puppet booth of Balaganchik was inhabited by an alienated Pierrot rather than the bawdy Petrushka of the Russian fairground.

Disdain for popular culture had several roots; the deepest root, perhaps, was an imprecise image of the "people" for whom so many struggles were waged. The Bolsheviks often neglected popular culture because they confused it with the folk (peasant) culture they despised so thoroughly. Here they burlesqued the attitudes of narodnik populists who had distrusted popular culture because it seemed like an impure version of the folk. The outcome was a failure to recognize that popular culture had strong and legitimate artistic traditions that could appeal to the very people the Soviet state represented.

Nevertheless, the vigorous process of assimilation proceeded. Although some forms of popular culture faded, others found new homes. Cultural forms are mobile; they move into new contexts within a culture and assume different meanings. A particularly fruitful source for festivals proved to be fairground culture. Gulianiia (carnivals or fairs;

from guliat', "to stroll") were distasteful to many Bolsheviks because of the sponsors: the Romanov family, with a more recent influx of entrepreneurial help. Yet the fact that carnivals were state run and state sponsored made the tradition exploitable. The opinion eventually prevailed that fairground culture should not be disavowed; rather it should be harnessed to the task of political education. Carnival culture was slowly transformed from raucous entertainment to pious proselytizer.

From the Fairground

Urban carnival culture in Russia thrived from the early eighteenth to the late nineteenth century.[3] Associated with Yuletide and Shrovetide, carnivals were bursts of color and celebration that bracketed the long Russian winter. Carnivals were confined to particular—but varying—spots within the city: in Moscow, Novinskoe Field, Maiden's (Devichee) Field, and Khodynka; in Petersburg, Admiralty Square (next to the Palace), later the Field of Mars. The Shrovetide and Yuletide holidays occupied a special time in the popular culture; as one saying had it:

Shrovetide comes only once a year;

I drinks a bit, don't spare the change

For holiday cheer.[4]

Shrovetide was the only time of year that the Finnish sleighs came to Petersburg; dancing bears would sometimes even appear in the city.

Carnivals were the only time and place in Imperial Russia where all classes could meet and mix. Early in his reign Nicholas I was known to visit with the people on Admiralty Square; and a foreign visitor noted that during a fête, commoners and courtiers met as equals.[5] Decades later, merchants and officers still found the holidays a fashionable time to promenade. Even the sheltered wards of the Smolny Institute for Noble Girls were known to circulate around the edges of the crowd in their carriages (or so they were represented in popular lithographs). By mid-century, however, the fashion had faded, and by the end of the century mixing was uncommon.[6]

Up until the 1880s, when the socialist International claimed May Day as its own, that holiday was also celebrated with a carnival: for Petersburgers, it took place in Ekaterinhof, a park outside the city.

Although the Ekaterinhof carnival was revived for May Day 1919, it lacked the splendor of former years.[7] Carnival thrives on excess; in 1919, Russia was starving and in the middle of the Civil War. Alcohol was forbidden as it had been during the war years; and the rich bliny , thin pancakes dripping with butter, were also a distant memory. Gone were the huge wooden swings of the traditional gulianie; gone were the ten-yard-high slides, coated with ice in the winter, on which a young boy could slide half the length of the Admiralty.

Bolshevik celebrations never provided the license of a true carnival; but this was due no more to a censorious Red soul than to the inroads of modernity. By the late nineteenth century traditional carnival amusements were being challenged by the products of the industrial age, the carousel and the roller coaster—which most of Europe called "Russian mountains," but which Russians called "American mountains." The vivid entertainments of the penny theaters were threatened, if not tamed, by the edifying shows sponsored by the People's Houses. Even when the old balagan master Lentovsky directed the 1903 May Day spectacles in the Nicholas II People's House, the show lacked the splash of yesteryear.

As holiday culture changed, the location it occupied within the city also shifted. From the early to mid-nineteenth century, the site of Petersburg gulianiia was Admiralty Square, next to the Palace. In the 1870s the fair was moved from city center to the Field of Mars, and the end of the century saw the Shrovetide carnival moving farther and farther toward the outskirts, coming to rest in the filthy Semenov Place. Carnivals of a sort were established in the once-elegant Mikhailovsky Manège near the center of town, where they resided until the First World War. The sponsor there was, at first, the Guardians of the People's Temperance; later, private enterprise was the organizer. The Guardians—representing a Victorianism alien to the carnival spirit—saw the fairs as an opportunity to attract the people away from the harmful influence of liquor.[8]

By the twentieth century, carnival culture had been redefined by the industrial city. Industrial culture, with its standardized sense of time, was opposed to the erratic, intensified time of carnival. No time or space was allotted for carnival in industrial society. The essential change brought about by capitalism was the disassociation of carnivals from holidays; this link had made them central to earlier cultures. The time frame of carnival was rendered obsolete by the advent of entrepreneurial financing; profits were highest when the carnival ran every day.

Carnivals, which had once occupied a central position in an alternative, holiday, culture, were now consigned to a peripheral role in a single

culture—one without alternatives. Removed from the center of social life, the carnivals were removed from the center of the city. The Mikhailovsky affairs were designed strictly for simple folk; no self-respecting officer or merchant would be found there. The broad, open spaces of the central squares were replaced by an enclosure, a roofed indoor space. The program had also changed considerably since the advent of the gulianiia . Entertainment, confined to a variety stage, combined balagan -type skits, vaudeville, and circus. Indoors there could be no ice mountains, no fireworks; no longer did hawkers roam the crowd selling hot bliny. Drinking, obviously, was banned.

The Russian carnival should in no way be associated with a rebellious vein in the culture; as a matter of fact, the Baron N. N. Wrangel (brother of the future White general) had led the prewar fight to revive carnivals on the Field of Mars.[9] In a great city, arranging and sponsoring a carnival is a complex process that can be accomplished by only the most powerful institutions, such as the autocracy. Yet the system that marked a carnival a holiday could be translated into an aesthetic of upheaval.

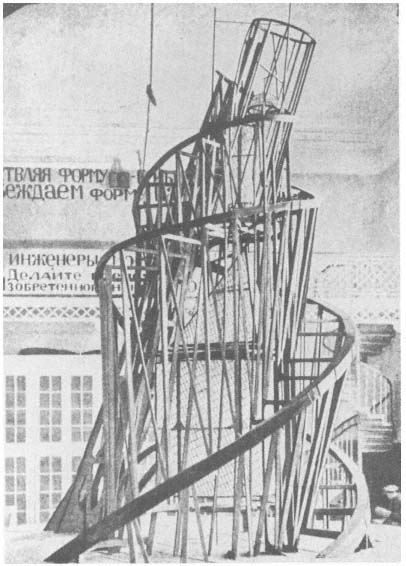

This transformation was what Mystery-Bouffe accomplished and what Meyerhold planned for November 7, 1918 (the first day of Mystery-Bouffe ), when he tried to revive the Manège carnival as a celebration of the Revolution. Meyerhold collected a remarkable organizing commission of artists who had used popular art forms in their work: Blok, Evreinov, Konstantin Miklashevsky (assistant to Meyerhold and Evreinov, expert on the commedia dell'arte), Lentulov, Sergei Prokofiev, Khlebnikov, Mayakovsky, and the choreographer Fedor Lopukhov. Also included were the finest performers of vaudeville and circus.[10] The program did not differ radically from earlier Manège carnivals: vaudeville, dance numbers, musical and circus skits, puppet theaters. The Manège itself was different; the huge statue of Nicholas II standing before it had been taken down for the holiday, and its bronze was given for reuse in the Lenin monument plan.[11] Yet the essential difference was Meyerhold's aim to return carnival to its former place at the center of the culture and restore the association with a holiday. The vitality, splash, and color dimmed by the Guardians and entrepreneurs would be restored. The commission planned for carousels, swings, and even extravaganza/melodramas—a balagan specialty. Alekseev-Iakovlev was hired to produce Song of the Merchant Kalashmikov (a repeat from the turn of the century), based on a Mikhail Lermontov poem; and when the commission discovered that the amphitheater where The Taking of Azov once played was still standing, it voted to organize a new spectacle

there. The planned revival was not entirely faithful: alcohol, an essential ingredient of the old carnival, was still banned, as were lotteries, a huge draw in prewar days. Strict censorship was to be enforced; but that too was part of the Russian carnival tradition.

Failure to realize the plan tells us more about the official side of Soviet culture in 1918 than about the popular side. The work of the commission, pursued over two months of meetings, fell victim to the bureaucratic skirmishes preceding the first anniversary. TEO, sponsor of the commission, moved its headquarters to Moscow in mid-summer; PTO, which took over operation of Petrograd theaters and spectacles, was run by Andreeva. She simply refused to recognize the commission and its plan; when funding disappeared, the commission dissolved.

Redefining Popular Culture

Popular culture was a ready conduit of images to the mind of the demos, and the Bolsheviks, who relied on their ability to disseminate ideas, never completely neglected it. Although older leaders such as Lenin and Krupskaia sometimes disdained its baser tastes, others, like Lunacharsky, saw considerable value and potential in it. Performance in the circus and balagany was of an extraordinarily high level of skill, and technique was frequently superior to that in the theater of high culture. There was a great tradition to be preserved, and great enthusiasm. Much of it belonged to younger, often anonymous workers in the political-education apparatus. Confronted by a vast, mobile, and often unschooled audience, local workers used familiar formats to transmit unfamiliar knowledge. By the early 1920s, thousands of local propagandists had developed a broad array of agitational and propaganda techniques, many of which relied on the legacy of fairground culture.[12]

Underlying the enthusiasm was a frequent disregard for the vagaries of communication. The assumption was that old popular forms could carry new ideas without extra burden and that their symbols and rhetoric would suffice for the job. Yet popular culture exerted an influence on the message it carried; it had rules and traditions of its own, many of which resisted new ideas. Conventions and types, for instance, which were the essence of balagan theater, were often imperfect expressions of Bolshevism and, as in the case of The Legend of the Communard, could thwart the intentions of sincerely revolutionary work.

Perhaps even more treacherous was the play element in popular entertainment. Plans for Moscow's May Day 1919 celebration, in which traditional May Day games such as tug of war and sack racing were to be used for propaganda, demonstrated the strain that political messages could put on games. A Soviet version of the Maypole dance was entitled the Carousel of Craft-Guilds: the title itself suggests how choreographed the dance—a traditional show of spring-inspired freedom—was to be. The Maypole was topped by a female figure symbolizing Soviet power, and the dancers were arrayed in their occupational costumes, one of which appeared to be Phrygian caps.[13] The traditional climbing of a greased pole was also changed by placing on the pole not a pig but an effigy of the White admiral Aleksandr Kolchak, which the winning contestant "overthrew."[14] Assimilation was clearly not an easy process. The fun of a game like pole climbing is in the effort and suspense, yet uncertain outcomes make propaganda an unreliable tool. Imagine the message conveyed if contestants did not scale the greased pole, and Kolchak rested atop it unassailed.

One type of popular game that adapted well to propaganda was the dramatic game (igrishche ). Dramatic games partook of both play and theater; the rules of dramatic progression, which regulate free variation, helped dramatic games carry political messages. Dramatized trials were a particularly useful game; though popular in origin, they were familiar to the intelligentsia as a prerevolutionary debate forum. The law, criminals, courts, and detectives were always a fertile topic for popular culture. They offered clear-cut situations and intriguing characters, sharply drawn divisions, and action that generated endless variations. Courtroom disputation fueled the plots of literature as diverse as Pinkerton (detective) stories and Dostoevsky's Brothers Karamazov, and it was also an integral element of traditional peasant weddings.

A common game in Cossack country was the Trial of Ataman Buria, which survived up to the First World War.[15] Buria, a figure from popular Ermak lore, sat in judgment over merchants, innkeepers, and landowners—the people's traditional foes. The trial was improvised but only in the sense that the commedia dell'arte had been—improvised from an inventory of ready speeches and situations. The conduct of the trial eschewed legal precedent and substituted the conventions of popular and folk theater: accusers came forward from the audience, and the accused, when given a chance to speak, tended to incriminate themselves no less than their accusers had. These self-incriminations were a variant of traditional comic self-introductions.

Political-education workers of the Southern Army made a dramatic trial into an effective agitational skit, The Trial of Wrangel, performed in the autumn of 1919 before ten thousand spectators.[16] The performance took place in Crimea Village, Kuban region—Cossack country. The plot was simple.

The court session is declared open, and the secretary reads the allegations, in which Baron Wrangel is accused of violating and murdering workers and peasants, of associating with foreign capitalism, of signing secret pacts with foreign powers delivering Russia into slavery, of aiding White Poland, etc. Then the interrogation of the witnesses begins. A turncoat from the Volunteer Army tells of Baron Wrangel's career in Crimea. A worker from Novorossiisk describes the Volunteer Army's "work"; then a Red soldier who fought in the Crimea speaks, then a port worker from Sebastopol; then a worker from Batum tells of hydroaeroplanes transported on steamships with Russian prisoners. A wealthy merchant tells of the charms Wrangel holds for the bourgeoisie. . . . Each witness represents a type, a particular social class, and gives a live picture of recent events. Finally, following the concluding arguments of the prosecution and the defense, and Wrangel's final speech, the sentence is announced: Wrangel will be destroyed, a sentence to be fulfilled immediately by the workers of Soviet Russia.[17]

The dramatic-game skeleton accommodated topical political material easily; and as the agit-trial (as the form came to be known) gained popularity, criminals as diverse as deserters and lice were put into the dock. Constant use brought changes to the play format. Though organizers claimed that the original agit-trial was improvised from a bare scenario, the scenario published was closer to a full text. The play element had to be disciplined if it was to become a reliable vehicle for propaganda; in fact, the question of how spontaneous an agit-trial should be became a hot item of debate among political-education workers in the 1920s.

Dramatic forms of popular culture offered ready vehicles for a political message, and melodrama was perhaps most apt. Like courtroom drama, it offered a simple skeleton that could bear unaccustomed loads. Melodrama first appeared in Paris in the wake of the French Revolution and was originally a musical drama. Soon however the term came to connote the unsophisticated dramatic convention by which good and bad are always unalloyed, terror and pity are liberally elicited, and the outcome is always happy (at least for the hero or heroine). This was the version that reached Russian balagany in the late nineteenth century and ultimately became a mainstay of the cinema.

Lunacharsky and Gorky were conscious of the genre's power even before the Revolution. It involved constant action, a key to popular

drama. When action was preserved as a primary feature, secondary characteristics of the melodrama, which determined propaganda value, could be put to use. Following Rolland, they believed that melodrama sustained in its audience the optimism needed for social renewal;[18] and its broadly drawn emotions and actions were essential for mythmaking. Melodrama was the seed of communist tragedy.[19] The analogy motivated a PTO commission chaired by Gorky to sponsor a melodrama contest in 1919, in which the style was defined as "psychological primitivism" and authors were asked to "clearly underline [their] sympathies and antipathies."[20]

The enthusiasm was not unadulterated. The melodrama had originally been a revolutionary form, that chose middle-class heroes in contrast to tragedy's aristocrats. But its evolution made it the preferred style of the Nicholas II People's House, no revolutionary institution. So when Lunacharsky and Andreeva gained control of the People's House through the Petrograd Municipal soviet in summer 1917, they replaced melodrama with the socially conscious plays of Gorky, Tolstoy, and Aleksei Pisemsky. This high-minded decision attracted everyone but an audience, which preferred entertainment.

Message is a notion to be applied to popular culture with only the greatest caution. Popular culture can, of course, be interpreted, as can anything given the proper observer at the proper distance. But often popular culture that seems from the outside like art, an ordered system of signs subject to interpretation, seen from within becomes play, an open-ended series of actions requiring no interpretation. Russian artists recognized that quality of popular culture and bent it to their own goals; in dramas like Andreev's He Who Gets Slapped and Blok's Balaganchik, it was a metaphor for meaninglessness.

These distinctions are of import to propagandists as well as to artists. The distinctions determine how ideas can be passed along and how they can outlast the moment of performance. A message is conveyed by an artist through controlled selection; game playing is impossible without randomness and risk. The controlling artistic consciousness, and the reader or viewer, must to some degree stand outside the work of art, aware of the conventionality of its rules; participants and viewers must temporarily immerse themselves in a game, forgetting that the rules are conventional and arbitrary. Play is as ephemeral as holiday culture; it occupies a special place and special time and generates its own conventions. Once the game is over, and its rules are again suspended, it loses its significance.

Play's greatest taboo is to step outside its boundary during its progress. In revolutionary Russia the use of popular culture as propaganda was precisely such a step, yet it had ample precedent. Popular entertainments like the carnival and circus were traditionally associated in time and place with holidays and fairgrounds. But by 1917 they had long ceased to be associated with holiday culture; they had settled in permanent buildings and consisted of patriotic pantomimes all through the Great War. Bolshevik propaganda violated popular culture's boundary, but it was a boundary already rubbed thin.

In addition, popular culture had particular rules of linkage that conditioned any attempt to convey a message. The circus, like vaudeville and other popular entertainments, was a string of short performances that, except for belonging to a single stage, had little structural connection. Animal trainer followed tightrope walker. Segmentation lent an emphasis to the parts, not the whole, in popular culture. Characterization, for instance, came from a single feature representing the whole, as in Mystery-Bouffe; episodes were the dominant building block of prose, as in the picaresque novel or serial tale. Selection and ordering of parts were quite often tenuous, determined more by tradition than by meaning. Circus and vaudeville acts were strung together in free order; pictures in the fairground peep show (raek ) were connected only by the barker's commentary. In a lubok, diverse segments were placed side to side in timeless simultaneity, while "in the popular theater, episodes were merely juxtaposed, laid next to one another without reference to the movement of historical time."[21]

Time in popular culture, as expressed by the progression of segments, is loose, accommodating, and disjointed; yet within episodes driven by action it is continuous and concrete. Constant action keeps it from drifting into the timelessness of monumentalism. This dual time system was at the foundation of early attempts at mass spectacles. The November 1918 festival was to feature "the staging of [seventeen] lubki depicting scenes from the revolutionary past."[22] For the same celebration, PTO's Repertory Bureau suggested a plan for an instsenirovka of six episodes: Spartacus, Vasily Nemirovich-Danchenko's poem about the troubadour who threw down the gauntlet before the king, the German peasant uprising, the uprising under William of Orange, Garibaldi, and both French revolutions.[23] This selection of episodes seems somewhat abitrary, but it was not alien to popular culture.

Revolution was not the only subject to be treated in this way. In innovative Voronezh, the Free Theater began its life with Rus', a synthetic

spectacle directed by Nikolai Forreger that summarized Russia's cultural history. The first play of the cycle consisted of five acts: "A Pagan Ritual," featuring priests, priestesses, and witches; "Anna Yaroslavna's Departure for France"; "Market Day in Kudrino," with boyars, Tatars, and jesters; "Theater under Aleksei I," in which a medieval débat was performed; and a folkloric performance of "Dances of Peasant Women."[24]

Such a simple collection of episodes was an effective instrument of propaganda; the selection of episodes alone dictated a particular concept of history and its movement. Episodes had been linked thus in the medieval mystery cycles, as they were in lubki . In the second year of the Revolution this method, which originated in popular culture, proved handy to established artists. In this time of great cultural shifts, popular culture was a ready source of new models.

The most ambitious project was Gorky's planned History of World Culture . Conceived as an educational series, History employed some of Russia's finest writers to illustrate key stages of world development.[25] The monumental theater Gorky had formed with Iurev, Chaliapin, and Andreeva was devoted to great manifestations of the human will; and History selected (somewhat randomly) moments when civilization had made great leaps forward, revolutions of the human spirit. It was a concrete conception of history, if one not entirely consonant with Marxist theory. Blok wrote or planned episodes on Ramses (surely the worst thing he ever wrote), Tristram, and even the building of the first boat; Gorky planned one on the Norman Conquest; and in a patent allusion to the present Zamiatin wrote The Fires of St. Dominic, about the Spanish Inquisition. Plays were written in prose dialogue, in folk (bylinnyi ) verse, and in fourteenth-century language; the only requirement was that subject matter be part of the humanity's logical progress in time. Professionals such as Mardzhanov were invited to direct the episodes—both for film and for mass festivals.

The Circus

Partisans of popular culture could follow two paths: remain faithful to tradition and develop a theater in which message yielded to action, the whole to the part; or tie the disparate segments of popular entertainment into a unified artistic whole. The ways that the new authorities used the circus provide illustrations of both paths.

When the Soviet circus became a focus of artistic attention in 1919, it was a reservoir of untapped performance skills. The TEO Circus Department was staffed by talented artists: Kamensky, Ilya Ehrenburg, Ivan Rukavishnikov, the avant-garde artist Boris Erdman, Kuznetsov, and Konenkov, and the choreographer Kasian Goleizovsky.[26] Artists fascinated by the circus were not entirely new; the circus had been fashionable with the prerevolutionary artistic intelligentsia.

The Sovietization of the circus could not be effected with the entire repertory. Some elements did not undergo transformation easily. Shklovsky suggested that only clown acts and pantomimes could be performed as art; acrobatics and other skill-based performances, in which plot, rhythm, and meaning-bearing structures were marginal, could not.[27] The more risk or chance in an act, the less suitable it was for the new circus. Randomness resists a message or ideology. The early Soviet circus shied away from the risk factor, from trapeze artists and tightrope walkers, preferring the verbal performance of clowns and the dramatic art of pantomime.[28]

The clown in the Russian circus was traditionally verbal; Lazarenko and the Durov brothers, supporters of the new regime, read verse they had written themselves as part of their routines. Lazarenko even performed a series of anti-White couplets written by his old friend Mayakovsky, entitled The Soviet ABCs . Clowns could function as spokesmen for the Bolsheviks without violating the traditions of their craft. Pantomimes, which had been popular during the First World War, could be assimilated, as the Cinizelli Circus in Voronezh in 1918 had shown. New figures could be grafted onto old plots: the Turks and Germans of World War I could be replaced by French and English interventionists; the cops and robbers by Reds and Whites. The same traditions, however, made clowns a double-edged sword. The most popular entertainment in Civil War Moscow was the clown duo of Bim and Bom. Their popularity, alas, rested not only on their wit but on its target, the Bolsheviks. Bim and Bom desisted from mocking the Bolsheviks only when their couplets so offended Latvian Riflemen in the audience that they shot up the circus and threatened to do the same to the clowns.[29]

For some popular spectacles to carry the new political ideas, they first had to undergo radical revision. Wrestling, a major circus attraction in the early twentieth century, could be exploited only at the expense of its sporting qualities. Skill and strength determined the outcome of the sport, but propaganda demanded a fixed conclusion. Lazarenko per-

formed a skit written by Mayakovsky entitled World Wrestling Championship, in which David Lloyd George, Woodrow Wilson, Wrangel, and Józef Pilsudski squared off unsuccessfully against the Russian champion, Revolution (the Russian words for wrestling and [class] struggle are the same).[30] Combats of skill, which might have culminated in a bourgeois victory, became instead a symbolic battle in which Revolution inevitably triumphed.

Circus spectators were unpracticed in the interpretation of wrestling. A wrestling match with a plot—a controlled sequence with an established ending—was unaccustomed entertainment; wrestling as a political language was unfamiliar; and most alien of all was the notion that wrestling could be language. If the message was to find its target, the audience needed to be warned that new cultural functions were active. Propagandists had not only to create the message but to highlight it and even supply the proper interpretation—much as they had for May Day 1918.

Popular culture provided a ready vehicle for this function, the intermediary. Intermediaries were essential to circus, vaudeville, and fairground-theater performances, which were filled with gaps as they passed from one skit or episode to the next. Because dead air was the greatest sin imaginable, gaps were filled by the appearance of an intermediary. The role allowed for great freedom of movement; it breached the time gap between skits, and the space gap between performers and audience. The role was filled by, among others, both the clown and ringmaster of the circus, vaudeville's master of ceremonies, and the compère of the artistic cabaret. Intermediaries performed an invaluable function when popular entertainment moved to a lecture hall: continuing to provide a structural bridge, they also explained the action to the audience and guaranteed that the proper message was received. The intermediary was a carrier and enabler of meaning. In Championship, the role was filled by the ringmaster, who combined the duties of referee and announcer, and helped spectators along by providing narration and exegesis.

All these functions were featured in one of the most influential shows of War Communism, Annenkov's August 1919 production of Leo Tolstoy's First Distiller . Performed in, of all places, the Heraldic Hall of the Winter Palace, the First Distiller used Tolstoy's antiliquor tract as the scenario for a concoction of circus, vaudeville, and balagan .[31] Tolstoy's original intent, and much of the text, disappeared in Annenkov's remake. The fable involved a demon sent to earth to tempt a peasant with liquor. It was a "modernized lubok, "[32] and Annenkov used popular

culture's loose time structure to insert clown acts, risqué folk ditties (chastushki ), and other tidbits into the action. Although some of the insertions were justified by the text, many were not: "Ditties were incorporated as the songs of peasants drunk on the 'devil's brew.' Accordions and choral dances were also inserted into the drunken scene. Acrobats appeared as demons; a circus was the model for Hell. And, lastly, an eccentric clown in red wig and broad 'formal' trousers appeared without the slightest motivation. He simply showed up in Hell and strolled around as though it was a nightclub."[33]

Assuming that the skeleton taken from Tolstoy was still present (some critics claimed it was lost entirely), the insertions were essentially full stops, moments when the progress of Tolstoy's play was suspended. Most were performed by the clown Georg Delvary, whose role was specially created by Annenkov. The clown had no place in the plot as such; rather he fulfilled an intermediary role traditional for clowns, standing on the forestage and commenting on the action occurring behind him. Annenkov claimed that his insertions could effectively carry the message: "A five-minute number can with a few phrases or gestures offer a joyful and convincing solution to any problem and convert an unexpected zigzag in the action into a weapon of propaganda, stronger than a public speech. . . . It screams, knocks, and burns a thought into the spectator's head—instantly, unimpeded by thought, at full swing."[34] But the claim was doubtful. The devil's antics, similar to commedia dell'arte lazzi, were entertaining, but carried no message. Not only did the antics not correspond to the play's specific message, they did not always assign the desired positive or negative value, which is a cardinal duty of propaganda.

Directors of the popular school faced a considerable quandary in propaganda productions like Mystery-Bouffe and First Distiller . Negative, anti-Soviet characters were depicted comically; positive characters were depicted monumentally. But in popular culture (for example, the Petrushka puppet play) comic characters were often more praiseworthy (more entertaining if less ethical) than the straight characters, usually pompous boors. The bad guys were more fun than the good. Interpretation was further complicated by the lack of signals about what in the play was significant (demanding interpretation) and what was not: insertions interrupted the intent of the play; halting the progress halted the transmission of the message. Ultimately, First Distiller was well done and well liked; only the claims to a message were unjustified.

Meyerhold, who had started the circus fashion in theatrical circles,

warned against its going too far. "The circus must not restructure itself at someone else's bidding," he said. "Reform must unfold within the circus, initiated by the circus itself. There cannot and must not be a theater circus; each is and must be a thing in itself, [although] the work of masters of the circus and the theater can draw close to one another."[35] The distinction went unheeded by the TEO Circus Department. Its artists fancied circus the art form of the future and were interested in it less as a popular entertainment than as a series of disconnected acts to be formed into a unified drama. One of the first reforms the department set about introducing was the "elimination of separate circus numbers and the reduction of circus performance to a single, unified action [deistvo ]."[36]

This approach was not entirely contrary to circus traditions; there were wartime precedents. At the Manège, for instance, popular attractions had been allegorical processions and tableaux vivants celebrating tsar and country, and pantomimes starring trick riders and special effects, such as Russian Herves in the Carpathians and The Inundation of Belgium .[37] Lazarenko, who would produce many such spectacles for the Bolsheviks, gained experience during the First World War. On December 16, 1914, before assembled diplomats of the allied nations, his circus had presented The Triumph of the [Allied ] Powers, a play in two acts, five scenes, written by A. V. Bobrishchev-Pushkin (who in 1919 would denounce Meyerhold to White forces in the South). The characters were Russia, France, England, Belgium, Serbia, Montenegro, Japan (played by Lazarenko), Breslau, Alladin, Sultan-Bey, two dancing girls, and a dervish.[38]

Still, giving the circus new Soviet functions entailed some redefinition. Wartime pantomimes afforded spectacular action, but the Soviet pantomimes praised more abstract qualities. The circus was robbed of its dynamism; and the resulting spectacles, but for the fact that they took place in the circus arena, were indistinguishable from allegories like that performed in the Voronezh Opera House in 1918 or even baroque court spectacles. In fact, one TEO proposal, which was rehearsed for almost a year in the Second State Circus, was a revival of Sumarokov and Volkov's Minerva Triumphant, first performed at the coronation of Catherine the Great.[39]

It seems that the greatest obstacle to imbuing circus with a message was its essence, action. Circus action is simply unreliable. Perhaps for this reason artists turned to tableaux vivants, an older, less eccentric form. Tableaux are allegorical and static, and can be counted on to make

their point. The sculptor Konenkov, who had just completed a group of wooden figures from the Razin lore for Lobnoe Mesto, was hired to direct a performance at the Second State Circus for the November 1919 anniversary. His choice of a theme, Samson and Delilah, was unfortunate (although he claimed it was a "song of the struggle for freedom"). The performance was a series of static tableaux, like a comic strip, portraying the stages of the Samson legend: the slaying of the Philistines with the jawbone of an ass; the seduction by Delilah; Samson's imprisonment; the final test of strength.[40] Konenkov employed wrestlers as the material of his sculpture; he made wigs and costumes, and carved wooden figures to encircle the tableaux. As the papers reported, "A long series of rehearsals was needed to create muscular memory in the performers and to force them to portray the sculptures with super-balletic exactitude."[41] The wrestlers, naturally enough, wanted nothing to do with it.

Another allegorical tableau presented that day in Moscow, Standing Guard for the World Commune, almost completely ignored the principles of the circus. It was based on the pyramid, a tumbling formation that had obvious social implications in revolutionary times.[42] The skit could have been played anywhere: "In the center of the arena a red stage rises up into a rainbow-shaped tower. There, on a platform, is the symbolic figure of a woman, Freedom, around which are grouped a peasant, a worker, a sailor, a soldier, and an intellectual . . . . Below on the steps are the corpses of Bavaria and Hungary, crushed by the imperialists. The figure reads poetry, expressing . . . confidence in the impending arrival of world revolution."[43] During the reading, statues of Marx and Engels flanking the tower came to life.[44]

Oddest of all circus presentations on November 7, 1919, was Political Carousel . Written by Rukavishnikov, whose wife ran the Second State Circus, where it was shown, Political Carousel was directed by Forreger, who by now was the director of the Moscow Balagan.[45] Forreger should have known better. This mass drama was performed on a three-tiered stage designed by Kuznetsov.

On the top level is a monster depicting imperialistic capitalism; near it are the Russian tsar, his court, family, and ministers. On the second level are bureaucrats . . . . On the third tier a prison is shown in which workers are imprisoned, guarded by soldiers and cannons . . . . The war with Germany is symbolically depicted, with the participation of all the imperialistic countries. The pantomime closes again with a symbolic representation of the Russian Revolution: the people drag the monster out of the tower onto the street, burn the monster, then dance and make merry.[46]

One could only agree with Shershenevich when he accused Rukavishnikov and the Circus Department of destroying the circus.[47]

The Mobile-Popular Theater

Perhaps prerevolutionary Russia's finest example of popular theater was Gaideburov's Mobile-Popular Theater, located on the outskirts of Petrograd. The Mobile-Popular Theater was the first to perform on the streets of revolutionary Russia, in May 1917; and it was there, not in Proletkult, not in Narkompros, not in the heart of Ivanov's imaginary demos that the first and strongest impulse for mass spectacles arose in Soviet Russia.[48]

Founded in 1903 as the Popular Theater by Gaideburov and his wife, Nadezhda Skarskaia, a daughter of the great Komissarzhevsky acting family, it was located in the Ligovsky People's House, funded by a wealthy Social Revolutionary, the Countess Sofia Panina. Its mission was to supplement the thin cultural fare offered Petrograd workers. People's Houses sponsored by the Guardians of the People's Temperance typically featured melodramas, patriotic plays, and "extravaganzas"; others offered a "special" repertory designed for the simple folk.[49] To Gaideburov, the gulianiia and other "people's entertainments" were the "greatest enemy of the rebirth of popular theater."[50] He demanded more from his audiences; the first production of 1903 was Ostrovsky's Storm, and the repertory continued with a variety of Russian and foreign classics.[51]

Gaideburov was one of the rare members of the prewar intelligentsia who could bridge the abyss between educated and untutored Russia. He respected the potential of the people and demanded respect in return. Initially, the audience needed some training; at the conclusion of an early performance, instead of the traditional roses an enthusiast threw a bottle of vodka onto the stage.[52] But soon the theater had educated a generation of viewers who appreciated drama. By 1907 the Popular Theater had merged entirely with its alter ego, the Mobile Theater, which, staffed by the same actors, spent summer months touring the provinces with a modern repertory aimed at the local intelligentsia (Figure 10).

Symbolist theater was gaining an audience in those years, as were the symbolists' rather mystical notions of how to close the gap between the people and the intelligentsia. Although not always evident in his practice,

Figure 10.

Emblem of the Mobile-Popular Theater, Petrograd

(P. P. Gaideburov, Literaturnoe nasledie, Moscow, 1977).

Gaideburov felt the influence of Ivanov. He believed that true theater, like all true art, brought the spectator into contact with the universal. It was classless, uniting all classes and nations through a common heritage.[53] Art was a door from everyday reality into a world of ideals; the spectator, momentarily aware of the divine, left the theater stronger, ready to live creatively.[54] If theater occupied a special, ideal position in culture, it also occupied a special time; it was "a holiday in the life of man. After all, it is special precisely because it is different from the everyday."[55] Theater was a festival.

Although Gaideburov shared some of Ivanov's basic tenets, there were essential differences: Gaideburov saw symbolism as Lunacharsky or Gorky did, as an art of dynamic change. He avoided static plays like the Death of Tintageles; the mainstay of his repertory was Björnson's Beyond Human Might, which ran for over 200 shows. In Gaideburov's interpretation, the drama was a paean to the power of faith to change human life.

When the theater's ambitions outgrew the bounds of spectacle, traditional forms became a constraint; Gaideburov, like his contemporaries, found his faith limited by stage conventions. The theater was to be like a

church; and the drama, a deistvo, a service in which "the people will be led to a pan-national creative illumination of life, in conditions of panhuman brotherhood and love. Life itself will be the object of creativity, and life will become a perfect work of art."[56] The contemporary drama, with long denouements, short climaxes, characters trapped hopelessly in the material world, and a passive audience, would not suffice.

Like his contemporaries, Gaideburov sought a theater on the threshold between ritual and drama. Early in 1918 he developed a hybrid theatrical form which he called "Masses" (mèssa, as in ritual). These occasions bore some resemblance to the poetic "requiems" hosted by the liberal Literary Fund at the turn of the century.[57] The first Mass of 1918, the Turgenev Evening, a memorial to the great novelist and poet, was as much about its maker as its subject. The Mobile-Popular Theater's Turgenev was deeply mystical; the Evening, like a church ritual, was an ascension to communion with his spirit.

The first segment opened on a stage decorated with only a bas-relief of Turgenev carved on an obelisk. The figure was draped in black, as was the entire set. The stage design was borrowed from Meyerhold's symbolist period at the Komissarzhevskaia Theater; and the ritual style of acting most probably had the same source. Figures came onstage chanting "the Great Pan is dead"; then figures entered the stage chanting an antistrophe, "the Great Pan lives."[58] The performers settled themselves about the stage and shared personal recollections of Turgenev's verse with the audience. The second section of the Evening was an oration illustrated by dramatic fragments, followed by the final section, a staging of scenes from Turgenev's works. The selection was mystically slanted: from Klara Milich, Spirits, A Strange Story, and the death of Bazarov from Fathers and Sons .[59] Like patriotic variety shows of the Great War, the Mass concluded with an apotheosis, a reading of the poem "The Russian Language."

The Mobile-Popular Theater's trip to the front in autumn 1917, immediately preceding the Bolshevik takeover, was a first attempt at "extramural" theater; and the Liberty Bond Day street production of Le vendeur de soleil showed how well it could be received by the people. But what Gaideburov really wanted, and what he advocated in a series of articles in 1918–19, was "theatrical, popular festivals . . . . Let it be the celebration of a national holiday, into which go speeches, processions, and songs. . . . Let it renew long-lost habits: Lenten celebrations, spring celebrations, celebrations of driving the cattle to pasture, of the arrival of a new car—

all this is theater that has been taken into the thick of the people, the theatricalization of life, artistic phenomena of a different artistic order, but still emanating from the nature of theatrical action."[60]

Clearly, he wished, like Ivanov, to take the theater out of the theater and to the people; and the Masses were a synthesis of theater and religion. But in his calls for national festivals, Gaideburov remembered a third element of festival performance, play, that Ivanov neglected. Here he was closer to Evreinov: "We must use the theatrical instinct, characteristic of everyone, which once helped create the forms of national life: games [play], holidays, rituals. Today, too, it can create a new ritual of national life, new forms of holiday interaction."[61]

Gaideburov pursued this idea less in the Mobile-Popular Theater, where the classics were still dominant, than in classes he and his actors conducted for the Adult Education Department (Otdel vneshkol'nogo obrazovaniia) of Narkompros. The courses were based on a philosophy different from that which had inspired the intelligentsia to organize theaters for the people before the Revolution: "We must depart from the previous educational view of theater, which saw the rationality of theatrical art in its literary side. . . . Play, specifically popular and specifically theatrical play, the activity of the people themselves, rich in artistic mysteries, will bring enlightenment."[62]

Acting, or play, was not to be taught; it was to be released from the people, where it had rested latent for centuries. The process involved a notion alien to Ivanov's ritual theater, improvisation. The Adult Education Department used the Skarskaia method, step-by-step instruction that introduced neophytes to the essentials of theater. The Skarskaia method stressed instinct over rational consciousness, inspiration and emotion over technique; the method was one of revealing, not inculcating, as "creativity is more or less inherent in everyone."[63]

Courses in improvisation were taught by Nikolai VinogradovMamont and Dmitry Shcheglov, members of the theater who would soon produce the first mass spectacles in Red Petrograd. Other instructors were Elena Golovinskaia, N. V. Lebedev, Viktor Shimanovsky, and Vsevolod Vsevolodsky-Gerngross;[64] these teachers, along with Grigory Avlov, another member of the theater, and Piotrovsky, who joined the group in late 1919, would be (along with Meyerhold's students Radlov and Soloviev) the most prolific producers of mass spectacles and directors of amateur theater in Petrograd until 1927.[65]

Gaideburov himself never took part in Bolshevik festivals. In 1918–19, relations between the Mobile-Popular Theater and the new regime

were acrimonious. In the difficult decade up to 1917, the Ligovsky People's House had offered shelter to many Bolsheviks, including Lenin. The party conducted meetings and lectures, and the nucleus of what would become Proletkult opened its first circle there.[66] But after the Bolsheviks took power, relations soured. The Countess Panina, who served the Provisional Government as deputy minister of public education, was jailed by the Bolsheviks for refusing to hand teachers' pension funds over to the usurpers.[67] Needless to say, Gaideburov and Skarskaia, who had the highest respect for the countess, did not approve of the action.

Differences ran even deeper, to basic philosophy. Gaideburov abhorred civic violence, particularly when it pitted class against class. His art had always strived to transcend class differences. In a letter published in the Mobile-Popular Theater's newsletter, Gaideburov defended his vision and roundly condemned the notion of a distinct proletarian art.[68] In 1919, those were fighting words. Rejection of class conflict meant rejection of the Revolution. The first of Gaideburov's disciples to object to the letter and to leave the theater was Vinogradov-Mamont.

The second half of Vinogradov's surname (which means "mammoth") was actually a nickname coined by the famous operatic bass Chaliapin to honor Vinogradov's infatuation with monumental theater.[69] Like Gaideburov and Ivanov, Vinogradov believed the theater to be a universal art; and he modestly formulated his ideas in the following "Seven Points":

1. The theater is a temple.

2. Universality.

3. Monumentality.

4. Creativity of the masses.

5. An orchestra of the arts [synthetic art].

6. The joy of labor.

Naturally, the last point of his plan was

7. Transfiguration of the world.[70]

Vinogradov worked with advanced students at the Adult Education Department on this new type of theater and planned a production of Aleksandr Pushkin's Boris Godunov as an open-air choral tragedy.[71] After seceding from Gaideburov's theater, he took his plans to the Political Administration of the Petrograd Military District (PUR), which was

sufficiently impressed to entrust him with 100 soldiers and the task of creating a new art. For the next two years, PUR was sponsor of Petrograd's most ambitious mass spectacles.

The Red Army Studio

The Theatrical-Dramaturgical Studio of the Red Army, or Red Army Studio, as the PUR group was called, was awarded the status of a special military unit.[72] Though just about all the soldier-pupils were amateurs—such was the selection by design—the instructors were professionals. From the Mobile-Popular Theater came Golovinskaia, Lebedev, Shimanovsky, and I. M. Charov; Shklovsky would later join the staff; Meyerhold, Vinogradov's old teacher at Kurmatsep (Master Courses in Scenic Productions), was prevailed on to help; Meyerhold's disciples Nikolai Shcherbakov, Soloviev, and Radlov joined in; N. N. Bakhtin, Meyerhold's collaborator at the Instructor's Courses for Children's Theater and Festivals, also assisted.

Long before the Revolution, even before the intelligentsia interested itself in the popular theater in the 1880s, the army had served to acquaint simple Russians with theater. Soldiers had their own special repertory: melodramas and the like, such as Kedril the Glutton and Filatka and Miroshka's Rivalry, which Dostoevsky noticed before anyone even suspected that Russian popular theater existed.[73] Most popular with the soldiers were dramatic games (igrishcha ), particularly Boat (Lodka ).[74] As opposed to the ritual dramas common in folk culture, Boat, which survived in cities up to the Revolution, was a bare skeleton onto which action was attached and improvised. The game was given a dramatic framework by "Down the Mother Volga" ("Vniz po matushke po Volge"—the song adapted by Kronstadt sailors as they sailed into revolutionary Petrograd), which was sung as accompaniment and narration.

Festival theater was born on the borders of drama, ritual, and play. If Gaideburov's own Masses mated drama and ritual, Vinogradov followed another example, that of his other mentor, Meyerhold, and trod the border of drama and play. Boat was an excellent model, with its origins in mimetic play; there was no stage, no props, and few costumes. Performance began with players arranging themselves as if in a boat, one player taking a position at the helm and singing "Down the Mother Volga," the others clapping hands in a rowing rhythm. It ended

the same way. The song provided a frame onto which episodes from the lore of the great Russian brigands—Ermak, Razin, and brethren—were attached.

Boat was less a drama than a cycle of episodes joined by a common theme and characters. Its time was the time of popular culture, a loose structure of stops and starts, which can expand and contract to accommodate new episodes. Like commedia dell'arte, Boat was improvised from a pool of traditional spoken lines and actions; and even more than in the commedia, connections between episodes could be loose. Yet Boat shared the ability of popular culture to take these disparate elements and unify them. Action within episodes was continuous. Perhaps most important to their new function within Soviet culture, dramatic games traditionally alternated tragic and comic scenes.[75]

The Red Army Studio's first production, performed March 12, 1919, was an igrishche on the topic of the February Revolution, The Overthrow of the Autocracy .[76] The first mass spectacle of Bolshevik Petrograd thus celebrated the February Revolution the Bolsheviks had overturned. The performance was a game in all senses of the word; it was play at revolution, a make-believe revolt by soldiers who had participated in the real one.[77] The performance, which would eventually be repeated 250 times,[78] was based on the Skarskaia method of improvisation. Most of the actors had taken part in some of the events and needed little directorial prompting. This, however, is not to suggest that improvisation engendered a deep, "elemental" understanding of historical events; nor should it suggest that the acting was necessarily spontaneous, direct, natural. Game playing has its conventions: the actors split off into two teams and, like little boys playing at war, depicted the historical conflict through a series of skirmishes and battles. Yet the play was about a bloodless revolution!

Vinogradov claimed that the oppressed masses of The Overthrow of the Autocracy were equivalent to the chorus of ancient tragedy and, because the ideals of the Russian Revolution were superior to those of slave-owning Athens, that the production was superior to the dramas of Aeschylus.[79] This analysis was perhaps overstated; but it would be unwise to ignore the production's artistic ambitions. Vinogradov's claim suggests a dilemma running through the Red Army Studio's history: Was it to be a popular undertaking, as the military theater traditionally had been, or was it to fulfill the great artistic ambitions suggested by symbolist theory?

The play did provide solutions to problems first pointed out by mod-

ernists. The division between stage and spectator, so porous in popular performance, was breached by the studio; this had also been an aim of symbolists. Popular culture's free combination of episodes was subjected to dramatic discipline; yet the structuring elements of the performance were taken from popular culture. Perhaps the similarities to simplified symbolist realism were apparent and desirable to Vinogradov; but the simplicity came from the exigencies of working with soldiers.

Whatever the cause, benefits were forthcoming. No decorations were used for the performance; real space was freely redefined by the action. As in melodrama, characters were divided into rebels and oppressors, good guys and bad guys. The stage itself was broken up into two platforms, each at one end of the Steel Hall of the People's House, where the play was performed. Linking the two stages was a broad aisle that passed through the audience.[80] The game principle, which split the characters into two "teams," had accordingly split the stage into two platforms; individual scenes were performed on the platforms; battles were conducted in the aisle. The aura of authenticity that brought spectators so close to the stage was intensified by the placement of actors in the audience. There were no costumes; dressed in army greatcoats, they were indistinguishable from the audience, and when they stood to deliver their lines, it seemed to spectators that one of their own was sharing a spontaneous reaction. Nevertheless, it was not the popular audience but the great artist Meyerhold who recognized what his pupil Vinogradov was looking for; when a young soldier, killed on the barricades, was borne down the aisle to "You Fell Victim," a song of revolutionary mourning, Meyerhold took the soldier's rifle from the ground and leapt to join the procession.[81] This was a sliianie, the merging of stage and audience the symbolist avant-garde had awaited.

The Overthrow of the Autocracy resembled a popular game, but it was supervised by professional directors. Their influence was visible in the formation of a unified play from discrete segments of improvisation. Episodes were not chosen at random, and neither was their order. The play comprised eight episodes chosen from the downfall of the Romanov dynasty: a prologue about the riots of 1905 was followed by the arrest of underground students, a revolt in a military prison, the seizure of the arsenal by workers, the sacking of Police Headquarters, the erection of barricades on the streets, the revolution at the front, and the tsar's renunciation of the throne (later observers would find the absence of the Bolsheviks unfortunate). The episodes were strung together in chronological order, with the dual platform providing a spatial model

for temporal progression. One stage accommodated the primary action, with mass scenes of the proletarian struggle for freedom; on the other was the counteraction, the reaction of the conservative camp. Later observers were correct in asserting that the split stage, free definition of space, and other features of Overthrow, which arose naturally from its game-playing nature, laid the foundation for future mass dramas.[82]

After several performances, young studio members found themselves praised to the stars by Gorky, Chaliapin, Iurev, and others. This was heady inspiration, and for May Day another spectacle, The Third International, was developed.[83] Like Overthrow, Third International was an improvised igrishche . The stage was the same, except for a symbolic globe placed center-stage—a prop borrowed from Mystery-Bouffe . One thing was new about Third International; it was played outdoors, in front of the People's House. The mobile stage used in both the studio's works made outdoor performance fairly easy; any place could be made to fit the play.

As in Overthrow, improvisation in Third International tended to degenerate into simple fighting, to the point that the play was not dissimilar from its predecessor. In fact, most revolutions depicted in subsequent mass spectacles would look similar, which had unanticipated political consequences. In the case of Third International, the conventions inherited from Overthrow distorted the historical picture. Fighting, which made up the bulk of action, had little to do with the Third International, founded only two months before in a conference hall; and the production's thousand participants far outnumbered the International's roster. Art predicts life, as Vinogradov might have answered.

Play-based Overthrow worked with a historical reality familiar to players and spectators alike. The basic episodes were taken from this reality; and if improvisation departed from historical facts, its creative license revived the emotional experience of revolution more vividly than an accurate re-creation could have. Third International did not satisfy itself with mimetic play based on a simple, concrete experience; it aimed toward symbolic, universal truths, as the globe in the middle of the stage signaled to spectators. The stage was not just a stage but the world beyond; people were not just people but allegorical types. Mayakovsky had done the same to wrestling in his World Championship .

The Red Army Studio, despite Meyerhold's tutelage, was just not up to these additional requirements. There had been no characters in Overthrow, just masses. Characterization demanded greater continuity between scenes, a stronger focus on montage and its meaning, and, alas,

greater acting skills. It demanded, in general, more art, less play. When studio actors began to portray characters and work from a text in International, it quickly became apparent that they were poor actors. The sharp division of characters into comic and heroic, pioneered by Meyerhold in Mystery-Bouffe, did not work for the studio; there was no one skilled in comic acting, which was much more difficult than Mgebrov-style heroic declamation. A need for professionals was becoming apparent.

The Red Army players had run up against what was becoming a familiar problem: play-based culture bore the burden of meaning poorly. Meaning-bearing structures were often a hindrance to play. When their ambitions shifted, those who devised the simple but fresh performances praised by critics began to fancy themselves the creators of a "new proletarian art," and their work evolved toward allegoric ritualism. It happened in the circus; it would happen in Proletkults all over the country; and it happened in the studio.

The next development was a tragedy—perhaps more a baroque allegory—written by Vinogradov and intended for performance by the studio, The Russian Prometheus (1919).[84] Picking a common theme (both Scriabin and Ivanov had written deistva of that name), Vinogradov wrote on the conflict between Peter the Great and Crown Prince Aleksei. The central figures (along with Peter and Aleksei) were two choruses: a tragic chorus of raskol'niki (members of religious sects) and the comic chorus of Peter's Most Drunken Council of Fools and Jesters, led by the jester Balakirev. Tragedy, according to Vinogradov, was the conflict and synthesis of equal and opposing principles.[85] The conflict led to the deaths of both Aleksei and Peter and, in the finale, Peter's ascent to heaven on a bank of clouds (perhaps Alekseev-Iakovlev could have provided the special effects).

The play was never performed,[86] and it would not merit attention but for the strong praise of some very talented contemporaries: Aleksei Remizov and Blok.[87] Lunacharsky took a more sober view: he noted that, yes, it did in many respects correspond to the theater of the future, but he also noted the strong and perhaps unintentional influence of decadent symbolism.[88] Lunacharsky's subtle criticism did nothing to discourage Vinogradov, who next wrote a deistvo entitled The Creation of the World .[89]

Graduates of Vinogradov's studio were sent to all parts of the country by PUR, and reports of similar performances began cropping up in the press. The Overthrow of the Autocracy was performed in Arkhangelsk;[90] Third International found its way to Perm.[91] Students sent to Cossack

country organized topical political games, The Taking of Rostov and Novocherkassk and The Smashing of Kolchak, using the same dual stage and the same acting methods.[92]

One of Vinogradov's assistants, Shcheglov, left the Red Army Studio for a studio of his own at the Petrograd Proletkult. Shcheglov, who had directed the Red Army Studio on a trip to the front, lost no time in applying the lessons of Gaideburov and Vinogradov. On May Day 1919, in the Porokhovye factory district on the outskirts of town, he produced the first (and only) of Proletkult's mass spectacles, From the Power of Darkness to the Sunlight . As the title indicates, Shcheglov too was guilty of allegorical excesses. The production, an "outdoor agitational show," was assigned to the Proletkult studio by the Petrograd party leadership, which kept a close eye on its creation.[93] Shcheglov knew from his Red Army experience that uncontrolled improvisation could not be allowed; he took the writing upon himself. But because there was little dialogue, which would have been lost in the open air, most of the performance, including the gist of the plot, was conveyed by pantomime. Speech was mostly slogans, delivered either by a worker chorus or by individuals with megaphones.

In popular culture, a bad script can always be saved by a good spectacle; From the Power of Darkness was rescued by Alekseev-Iakovlev, in whose hands heavy-handed allegories became wondrous sights:

On a special platform, emaciated people smeared with soot spun flywheels and spoke sad words . . . taken from the proletarian poet Tarasov. . . . Occasionally a colossal figure in black with a whip in its hand would rise above the group, precisely in those moments when murmuring began and voices of protest were heard. The figure's first appearance was so unexpected, and its dimensions so huge, that the public oohed and aahed. Alekseev was truly a master of his trade. . . .

But then a red figure ran directly through the surprised crowd of spectators. . . . It stopped, raised its hand, and a red Roman Candle flared up above its head. Red "specters of communism" immediately appeared from all sides. Their appearance halted the wheels' movement: they were followed by exhausted people, but the "specters" ran past and underneath a broad old tree, in the branches of which appeared an "agitator." He read Tarasov's poem, and the workers answered from the stage: "We are here, we are ready! Battle approaches, and smoke spreads through the valley."

Hands raised hammers high to break the cursed chains; a woman with a child on her breast raced toward the "red tree" [mahogany]. But suddenly something hissed and exploded in her path, and clouds of smoke began to spread. However, this barrier could not impede the laboring masses. Raising high their hands bound in chains, the workers left the tribune for a place that

augured freedom. But suddenly from all around there appeared the "shades of evil," huge figures in black. They cracked their whips, and the orchestra began to play music from a long forgotten adaptation of Gogol's Terrible Vengeance that Alekseev had once staged in the People's House.

Bowed and tamed, the workers retreated without casting away their age-old chains. And again the wheel began to turn with its sickening screech. The woman with the child returned to the action. Climbing the steps she read:

They laid there in the corner,

In the dirt of the stinking police station,

The blood thick like paint,

A puddle congealed on the floor.

My friends! The enemy won't yield,

He will buy the sacred rights of an uplifted nation

At the price of new victims, a cruel price.

Having finished her reading, the woman ripped the black shawl from her head. Underneath was a bright red one. Others began to repeat her words, and the gray-black light on the platform where the wheel spun quickly turned red. The workers again set to breaking the chains, but, the moment the last chains were to be cast from a girl in a white dress and broad red ribbon, the forces of darkness reappeared. To the pounding of kettledrums a symbolic battle began. . . . Figures in tunics tumbled down to the enthusiastic cries of surprised spectators, and the performers themselves in their excitement forgot that the "evil forces" were only young men from the factory, standing on each others' shoulders and holding up yard-tall poles with capes and heads in top hats and "stupendous" yellow teeth bared for effect. Boys from the crowd threw themselves with exalted howls and whistles into the "battle with evil"—that is, they went to knock the giants over. The spectators applauded, . . . but suddenly everything fell quiet. One of the "forces of the past" that had managed to save itself stole up to the girl on stage who had not yet managed to free herself entirely from her chains. A duel between the girl and the enormous figure began: the girl waved a red cape; the black figure cracked its whip, all the while getting smaller and smaller. The liberated workers approached them from behind and, crushing the last "knight of darkness," took his remains to another platform, where they hoisted the head and cape and set them on fire. First there were hissing clouds of smoke—"the stench of the past"—the head caught fire and burned long and bright, throwing out multicolored sparks. From all the trees where the "red specters" had clustered bengal lights burned, and the workers again stepped onto their old platform, where the machine wheel turned out to be decorated with ribbons and flowers. The whole thing ended with a collective reading of Glory to Labor .[94]

From the Power of Darkness pleased the authorities, and in November Shcheglov was invited to produce another spectacle, From Darkness to Light, in the city center. The second spectacle could scarcely be distinguished from the first.

Late in 1919 leadership changes in the Red Army Studio sparked changes in the plot of Overthrow . A young poet, scholar, and playwright, Piotrovsky, an enthusiast of the Revolution and follower of Ivanov, took charge.[95] Piotrovsky quickly spotted a major deficiency: although the play concerned historical change, little sense of history was conveyed. Perhaps more damning was that the play, which celebrated the Revolution, failed to include the Bolsheviks. If dramatic games like Overthrow, which featured continuous action and uniform episodes, were to portray the sweep of history and the Bolsheviks' sense of historical mission, changes were necessary, but not along the lines of Vinogradov's later plays. Recognizing that the Bolsheviks' mission was manifest not in events but in the progression of events, Piotrovsky portrayed the Revolution as a process beginning in February and culminating in October. He added two episodes: a comic interlude about the Provisional Government and a heroic finale about the October Revolution. The whole thing was renamed Red Year .

The introduction of discontinuous episodes brought up the question of how they could be assembled into a whole. Piotrovsky took structures characteristic of popular drama and assigned them new functions, for which Mystery-Bouffe offered a ready model. The alternation of tragic and comic, which Mayakovsky had used for characterization, was used to stitch together episodes in Red Year . Space operated on a similar principle; in the final two scenes, Kerensky and Lenin face each other from the two stages, and the final conflict occurs in the corridor between. This principle of simple oppositions, spatial, temporal, political, and moral, would be a rule for most future mass spectacles.

Piotrovsky also introduced changes in the performance. The full-length Red Year was held together by concrete historical figures and fictional characters, who replaced the faceless masses of Overthrow . Such characterization required disciplined acting and costumes to make figures like Lenin and Kerensky identifiable, but it also changed an essential principle of Overthrow: actors were now separated from the audience. Improvisation also gave way to a scripted text, which fixed the proper message but suppressed the playlike character of Overthrow . Improvisation had been intended to release the soldiers' creative instincts, but true improvisation, like true play, is a risk. Improvisation had been to a large extent desirable in Overthrow, which was an emotional experience of the tension and uncertainty of revolutionary days, when the future was unknown. From a strictly Bolshevik point of view, though, history was not uncertain. The October Revolution was an inevitable

conclusion to the events of 1917 and, for that matter, to a century of history. This was in fact the Bolsheviks' greatest claim to legitimacy, particularly in opposition to the claims of other leftist parties.

The changes were regrettable but perhaps inevitable if the play was to fulfill the edifying function that its sponsors intended. Much the same was happening at Proletkult. Shcheglov, like Piotrovsky, attempted to discipline improvisation in his next production, Popular Movements in Russia .[96] Although improvisation was not entirely discouraged, the creative process was subordinated to the director's will. For the first time, soldiers were portraying events unfamiliar to them; they had to study events, not relive them emotionally.[97] Themes were chosen by the director. Improvisation continued unhindered in rehearsal until it deviated from the plan, when it was halted and corrected. The final result of all rehearsals was then treated as a fixed text.[98]

The episodes, selected and assembled during rehearsals, presented a new concept of revolutionary history that would much later gain broad currency in Soviet Russia: the October Revolution as the culmination of national history, ignoring Western influence. Popular Movements was something of a misnomer: it tied together the Bolotnikov, Razin, and Pugachev peasant uprisings, the rebellion of the aristocratic Decembrists, the revolt of the tiny village of Bezdna (Bottomless Pit) in 1861, the 1905 revolution, and the Bolshevik seizure of Moscow in December 1917. As the last episode of a series, the Bolshevik takeover was the assumed heir of a great historical progression.

The limits of the popular style were reached by the Red Army Studio in February 1920, when The Sword of Peace was produced for the army's second anniversary.[99] The play was called a "variation" on The Overthrow of the Autocracy, but the resemblance was distant. To emphasize ties to the popular theater, it was performed in the Cinizelli Circus, yet Piotrovsky's text was written in the blank verse of high tragedy. Radlov directed the play and employed the dual-platform stage of Overthrow, but of course, with a text in blank verse, there could be no improvisation. The plot was built from the basic stages of the Red Army's history. The play opens with a soldier in a greatcoat and helmet, spotlighted center-stage, portraying Trotsky at Brest-Litovsk. Unrolling a long scroll (the treaty) he declaims:

Comrades! the workers and the peasants

Are neither murderers nor thieves! We don't need

A predatory war. We need peace. . . .

Red soldiers, you are the hope of peace!

You are the sword of peace. The future of the Commune

Is on your banners. In bloody splendor

The Red Star ascends above the world.

In truth, a new world has been born.[100]

To Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique a shower of red stars rains down from the big top, and the Red Army rushes into battle. Battle scenes, like those in Vinogradov's productions, ensued; but an interlude, in which Three Wise Men crossed the stage in search of the Red Star rising in the East, separated the battles into episodes.

The Revolution prompted shifts in the cultural hierarchy. Popular forms once consigned to the periphery of Russian culture moved to the center and were given new responsibilities. These responsibilities could be met only at the price of structural changes. The play element that had been the essence of popular culture could not always bear the messages thrust on it by the Revolution.

When popular theater began to serve official purposes, changes could be observed: the subordination of improvisation to directorial design; a shift of emphasis from episodes (most early amateur depictions of the Revolution were one-act plays) to the way in which episodes were strung together; and the loading of symbolic interpretations onto play-based actions. Individuals replaced mass characters and choruses; costumes were introduced to identify the new characters; acting became increasingly complex. These changes were an early example of a trend in Soviet Russia: popular performance, an autonomous branch of culture with values and a style of its own, was replaced by amateur performance, a secondary reflection of high culture.

Mass spectacles had caught the attention of Bolshevik leaders and had shown the potential to project a compelling view of the Revolution. Yet to realize their significance within the new culture, they would have to expand beyond the local audience. Greater organizational skills were needed; and if an audience unfamiliar with the actors and their locality was to be attracted, the full resources of the theatrical heritage would have to be exploited. There was only one option. Professionals would have to take control.

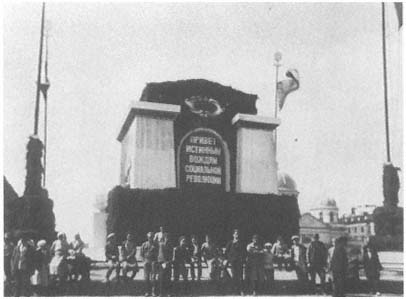

Plate 1.