5—

Contemplating the Ancients

Yu Yuanzhi once asked his uncle, Wenkang, about [the meetings in the Bamboo Grove]. The latter replied, "I never heard of it while I was [in the north]. If this story has suddenly showed up here, some raconteur just made it up, that's all."

Zhulin qixian lun

Humiliated by defeat, transplanted to a strange land, the northern émigrés yearned (at least in public) for the Heartland. It is not surprising that, as they struggled for a foothold in their precarious new world, stories about "home" began to circulate—to be embellished and written down, often merely to amuse, but just as often to instruct. The stereotype of the Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove took form in this, the fourth century, far from the site of their alleged revels and colored as much by the political realities of Eastern Jin as by the misted landscapes of the south.[1]

By the end of that century and the first half of the fifth, the Seven Worthies, as a group and as individuals, were celebrated in literature, history, and painting.[2] Poets alluded in their own works to poems written by Xi Kang and Ruan Ji; statesmen quoted from their literary

works; emperors and courtiers created paintings illustrating their poems. Anecdotes about their purported exploits proliferated; it is said that their portraits (xiang ) were painted.[3] Finally, the men of Eastern Jin and later often compared their contemporaries to the Seven Worthies. They were, in short, famous. And more: they had become models, deemed worthy of emulation by at least some men of the new world—for the benefit of society and for the benefit of oneself and one's family.

The task is manifold: First, to determine from the wealth of extant documents the traditions about the Seven Worthies (as well as Rong Qiqi) that were known to the elite of the fourth and fifth centuries.[4] Comparing these traditions with the Nanjing mural, I shall attempt to place the mural within one of these traditions. For its full significance, however, we must then turn our attention to those who admired that tradition, to those who might have wanted to rest eternally with the Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove and Rong Qiqi.

Traces of Fame

Although New Tales of the World states that the Seven Worthies gathered in a bamboo grove, "letting their fancy free in merry revelry," there are no specific accounts of these revels.[5] In one anecdote Wang Rong says that long ago he frequented a wine shop with Xi Kang and Ruan Ji, and "in the outings in the Bamboo Grove I also took a humble part."[6] He offers no details, however. The specifics, rather, appear in stories about individual members of the group: Ruan Ji, hearing that the commissary stored several hundred hu of wine, requested appointment as the commandant; Liu Ling was always accompanied by a man with a spade, who was ordered to dig his grave wherever he happened to drop; Wang Rong was so parsimonious that he gave his nephew only an unlined gown as a wedding gift and later billed him for it.[7]

It is clear, however, that by the fifth century traditions for the Seven Worthies as a group were well established. Although commentators drew on the same anecdotes and literary works, they interpreted them in varying ways that fall roughly into two opposing categories.[8] The first characterized them as a raunchy, immoral crew, carousing and defying all propriety. The second, conversely, depicted them as serious, contemplative men, whose defiance of convention masked

their distress over the political events of the day and expressed their criticism of a Confucian ritual-behavior grown sterile. A few examples give the flavor:

Criticizing a later band of revelers, Deng Can blamed the Seven Worthies: "Hsieh K'un [Xie Kun] . . . and other companions of Wang Ch'eng [Cheng] emulated the 'Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove,' and with their heads dishevelled and hair falling loose, would sit around naked, their legs sprawled apart. They called themselves the 'Eight Free Spirits.'" Dai Kui, however, insisted that, unlike the spirit of their models, "the spirit of those later imitators of the Seven Worthies was not genuinely transcendent. . . . They were merely taking advantage of it for self-indulgence and nothing more."[9] Neither commentator denied the behavior; it was the interpretation of that behavior, decadent or transcendent, on which they differed. For both Deng Can and Dai Kui "truth," or reality, was to be found beyond appearance, in the characters of the men and in their intent. Behavior, for both commentators, required interpretation and judgment.

Referring to stories that Ruan Ji had violated the mourning rites, Gan Bao caustically remarked that "if ever there was a case of letting the hair fall loose, or acting in an unrestrained or contemptuous manner, or turning the back on the dead and forgetting the living, while claiming on the contrary to be fulfilling the rites, Juan Chi [Ruan Ji] was such a man."[10] Sun Sheng denied the charge. Ruan Ji, he said, was "by nature extremely filial. While he was in mourning, even though he did not follow the ordinary prescriptions, nevertheless he was so wasted away that he nearly lost his life."[11]

Xi Kang's outstanding ability, said the emperor Jianwen (r. 371–372) harmed the Way.[12] Yan Yanzhi (384–456), agreeing that he was not like others, defended him for that very reason. Praising that outstanding ability, Yanzhi exulted, for, although one may sometimes hobble the phoenix, "who can subdue the dragon's soul?"[13]

Liu Ling appears in the Shishuo xinyu as thoroughly dissolute:

On many occasions Liu Ling, under the influence of wine, would be completely free and uninhibited, sometimes taking off his clothes and sitting naked in his room. Once when some persons saw him and chided him for it, Ling retorted, "I take heaven and earth for my pillars and roof, and the rooms of my house for my pants and coat. What are you gentlemen doing in my pants?"[14]

But he was not really a coarse and idle lout, Yan Yanzhi explained. He was merely hiding his grief in daily drunkenness. Ling's "Ode to

Wine," he claimed, was actually a very profound work that revealed his deep mourning.[15]

As for the carefree recluse Rong Qiqi, he too found a place in the new world across the river. Lidai minghua ji records, for example, that Gu Kaizhi painted a picture of the ancient worthy, while his meeting with Confucius is reported in the Liezi. In this version, however, the Master has the last word. Pleased with Rong Qiqi's expression of joy, Confucius adds, "He is a man who knows how to console himself." To which Zhang Zhan (fl. 370) commented that Rong Qiqi is "unable to forget joy and misery altogether; Confucius merely praises his ability to console himself with reasons."[16]

Rong Qiqi appears also in poems by Tao Yuanming, who twice couples him with virtuous recluses and refers to him as "cold and hungry." He wonders if such deprivation was worth it, and, as is so often true of the great poet, comes to differing conclusions. He ends one poem affirmatively: "They had to be firm in adversity / For their names to live a thousand years." In the second poem, however, Tao Yuanming decides that fame is no consolation after death. It is best to please oneself: "A man should go beyond accepted views."[17]

The fourth-century embellishments of the exemplar of ziran intimate a poignancy not apparent in the earlier literary image, a suggestion that one is never completely free or that a price is always paid. The fictional character is seen as more complex and thus as more human.

The literature is rich and the stories are delightful. However, when we compare the anecdotes and their interpretations with the images of the Nanjing reliefs, we are nonplussed. Where are the nakedness, the sprawling, the flouting of convention of which we have just read? Where are the Ruan family's convivial pigs, Ruan Xian's nubile slave girl, Xi Kang's lice?[18] Do three wine cups and three musical instruments make a debauch, a "merry revelry" even? No figure, in fact, is "noticeably tipsy," nor are the men really depicted together, in a group.[19]

Of course, anyone who saw the murals (those who attended the funerals of the two tomb occupants) would be reminded of the many stories that circulated in the fashionable world.[20] Knowing them, and the deceased, they might interpret the portraits as those of men who were "free," or whose antics hid their grief. Or they might see it as a cautionary tale, a lesson for survival. After Xi Kang's execution, for example, his friend Xiang Xiu was recommended for office. Arriving

at the capital, he was interviewed by Sima Zhao (who had ordered Xi Kang's death).

[The Generalissimo] asked him, "I heard you had the ambition of retiring to Chi Mountain; What are you doing here?"

Xiu replied, "Ch'ao Fu [Chao Fu] and Hsü Yu [Xu Yu] were timid, pusillanimous men, not worthy of much emulation."

[Sima Zhao] heaved a great sigh of admiration.[21]

Yet, the pictorial and literary depictions seem ill-matched. Nor can we seriously consider the possibility of skill-deficiency for artist or artisans. Careful examination of the forms leads, on the contrary, to admiration and to the assumption that greater pictorial and literary correspondence was certainly possible, if wanted.[22]

Perhaps further probing of the traditions will reveal a closer correspondence. In addition to the many anecdotes about the men portrayed, the Seven Worthies were often characterized. That is, they were judged —pithily, wittily, quite as if they were candidates for office (as indeed they once were). Gu Kaizhi, for example, averred that Shan Tao could not be described. "Pure, deep, mysterious and silent—no one saw his limits, yet all agreed that he had, indeed, entered upon the Way." Zhong Hui had recommended Wang Rong to the ruler, saying, "He is unceremonious and keeps to the essential." Pei Kai had said of him that "his eyes flash like lightning beneath a cliff." Wang Gong once remarked that "in Juan Chi's [Ruan Ji's] breast it was a rough and rugged terrain; that's why he needed wine to irrigate it."[23]

Xi Kang had "the beauty [zi ] of a phoenix, the grace [zhang ] of a dragon." Some characterized him as "serene and sedate, fresh and transparent, pure and exalted!" Still others said of him, "Soughing like the wind beneath the pines, high and gently blowing."[24]

In contrast to Xi Kang, Liu Ling was said to be short, ugly, and dissipated-looking. Ruan Xian possessed a "divine understanding" of music. Shan Tao had once recommended him for a government post by characterizing him as "incorruptible [qing ] and honest, with few desires; the myriad things of the world cannot budge him."[25]

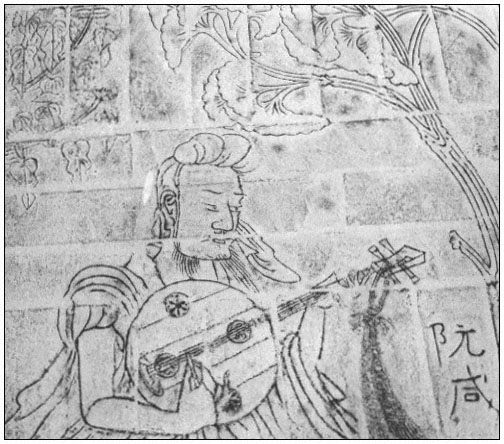

Although we may intuit a correspondence between such characterizations and the v:isual forms, can we objectify that correspondence? The instrument held by the figure of Ruan Xian may indeed signify his divine understanding of music (fig. 31).[26] The erect back and poised fingers of Xi Kang may well be interpreted as a calm serenity (xiao xiao ) His tumbled garments and exposed flesh, however, are hardly

31.

Ruan Xian.

Detail of figure 3.

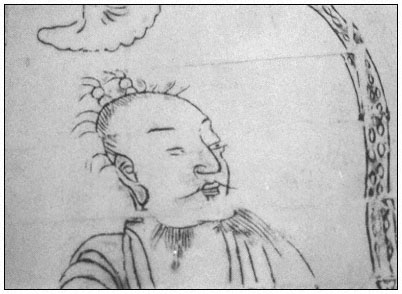

signs of a sedate, or decorous (su su ), figure. Indeed, such characterization is more appropriate to the image of Dong Shou in the tomb at Anak. Nor can we discern a distinction between the beauty of Xi Kang and the ugliness of Liu Ling. The faces of both men, for example, are identical (figs. 32 and 33).[27] Differences in height are not evident. It is possible that Xi Kang's erect head and posture reflect a dragon-grace or a phoenix-beauty. On the other hand, it is difficult to believe that Liu Ling's bent head is meant to reflect ugliness.

32.

Xi Kang.

Detail of figure 2.

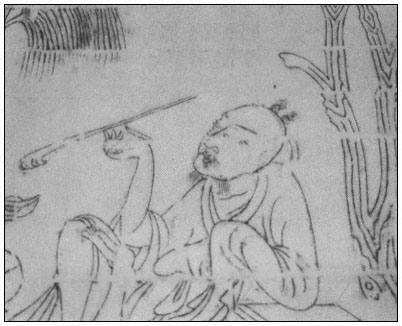

33.

Liu Ling.

Detail of figure 3.

Wang Rong's flashing eyes (fig. 34), capable of direct depiction, are no more visible than that which cannot be depicted objectively—Ruan Ji's rough and rugged inner terrain. The wine pot beside the latter may, however, be its external sign.

In short, when we search for physical characteristics whereby to identify the seven historical individuals whose portraits confront us, we cannot find them. When we rummage among the many anecdotes about them, we discern few pictorial forms that jog the memory—a wine cup here, a musical instrument there. Checking literary characterizations, we are unable to apply them to the various figures and say with certainty that the depiction of each corresponds to individual descriptions of their character.

With but one exception, we cannot, in fact, identify the individuals depicted pictorially from the literary texts. Only the gesture of Ruan Ji, his fingers close to his pursed lips and puffed cheeks, reminds us of his adventure in the Sumen Mountains and enables us to identify him with any certainty.[28] As for the others, were we to exchange the musical instruments and remove the names from the bricks, Xi Kang and Ruan Xian could each pass for the other. Were we to remove the wine bowl from the one and give it to the other, Liu Ling and Xiang Xiu could not be distinguished. Although each figure differs slightly from all others in posture, in the way the drapery folds curve and fall around them, in their headdresses, fundamentally they are all alike. In my opinion, they were intended to be so. The eight figures are a collective portrait, in which the forms and their placement in a single, but bifurcated, composition convey a specific character, an ideal-type, one both admired and denigrated by many men of the fourth century and long after.

The texts, for example, reveal that all the Seven Worthies had in common certain character traits, regardless of their individual life trajectories.[29] The comments and opinions about them focus on two dimensions of character: ability and its expression.

All Seven Worthies are characterized as men of outstanding ability. "Just as [Xi Kang] was, in the midst of a crowd of other figures, one would know unmistakably that he was a man of no ordinary capacity." All the little boys, spotting by the road a laden plum tree, ran to gather the fruit. Wang Rong, however, stood still: "If the tree is by the side of the road and still has so much fruit, this means they must be bitter plums." And so they were. Because of this incident, the seven-year-old was "acclaimed for his divine intelligence even in his youth."

34.

Wang Rong.

Detail of figure 2.

"Because his capacities were ample, Shan T'ao [Shan Tao] was looked up to by the court . . . Youths from noble families all sang his praises."[30]

This ability was expressed in several ways. Ruan Xian's subtlety (wei ) could be discerned in his musicianship; drunkenness hid Ruan Ji's brilliance (zhao ) and Liu Ling's refined essence (jing ).[31] Having twitted Xiang Xiu for devoting his time to a commentary on the Zhuangzi, his friends Xi Kang and Lü An later read it. "K'ang remarked, 'Have you actually beat us again?' An cried out in surprise, 'Chuang Chou [Zhuang Zhou] isn't dead!'"[32] "Shan T'ao's selections for public office which he had made throughout his career had practically run the gamut of the various offices. . . . In every case where he had written an estimate of a candidate's ability, it proved to be exactly as he had stated."[33]

Literature, philosophy, music, and that most important art of the times, knowing men—these were the refined expressions of their innate abilities, and the men were famous for them.

All the Seven Worthies are characterized as free, unrestrained, or unceremonious. "Xi Kang despised the world, remaining unfettered [bu ji ]."[34] Ruan Ji was criticized for violating the rites by visiting his sister-in-law. "Were the rites established for people like me?" he demanded.[35] When Shan Tao recommended Ruan Xian for office, he knew, said Dai Kui, that the emperor could not use him. "It seems he simply did it because he admired the strength of his freedom [kuang ] from the world."[36] Liu Ling treated his body like so much earth or wood.[37] Indulging his fancy, "he let himself go (fang dang )."[38] Wang Rong was unceremonious (jian ), Shan Tao was free (hui da ).[39]

Similarly, such words as "pure" and "remote" are associated with the unfettered Worthies. Xi Kang and Shan Tao are "pure" (qing, chun ).[40] Xi Kang is "like a solitary pine tree standing alone."[41] One who read Xiang Xiu's commentary to the Zhuangzi felt "released, as if he had emerged beyond the dust of the world to peer into Absolute Mystery. For the first time such a one understood that beyond sight and hearing there is a divine power and abstruse wisdom which enables one to leave the world behind and pass beyond all external things."[42] Looking at Shan Tao, said Pei Kai, is like "climbing a mountain and looking down, far, far from the world."[43]

Rejection of ritual behavior, purity, remoteness: those Worthies who turned their backs on the world and those who chose to remain firmly in it were thus characterized. It is an inner detachment of which we read, a quality of character one retains even amidst the dust of the world, and discernible, even there, by those truly capable of knowing men.

Perhaps it was their inner detachment and purity that led so many to refer to the Worthies' self-possession, the ability to retain composure under all circumstances. Liu Ling was "always in good spirits, the most self-possessed man [zide ] of the entire age." "On the eve of Xi Kang's execution . . . his spirit and manner showed no change." Wang Rong announced that he had "never seen an expression of either pleasure or irritation on his face." Criticized for his failure to abstain at a party although still in mourning for his mother, Ruan Ji "continued drinking and devouring his food without interruption, his spirit and expression completely self-possessed [shen se ziruo ]." When a tiger broke loose and all others fled in fear, Wang Rong (then seven years

old) "remained placid and motionless, without the slightest appearance of being afraid."[44]

Outstandingly able and refined, untrammeled and pure, self-possessed—this is the Eastern Jin–Liu-Song literary characterization of the Seven Worthies, and it is the pictorial characterization as well.

Judging the Manner

"We would fill our wine cups and pass them to one another and then, when the strings and winds played together and our ears were hot from the wine, we would raise our heads and chant poetry." The scene invoked by the Wei emperor had long since become the preferred life-style for the elite, and no educated courtier in Jiankang could fail to remember his words when beholding the mural.[45] How simply and efficiently the artist/artisan transforms a literary image into a pictorial one: eight informally dressed figures, seated on mats, and ten trees suffice to inform the viewer that the dust of the world (the city, the court) has been left behind. Three wine bowls, three cups, three musical instruments are the attributes that economically convey the happy pursuits. It is not a debauch; it is a moment of leisure, in which wine and music play their appropriate and refined roles. The inscriptions naming two of the famous figures as Xi Kang and Ruan Ji affirm beyond question the "presence" of poetry, while the inscription naming the recluse Rong Qiqi forces the conclusion that this is what it means to be free, to be an adherent of ziran. If its pictorial expression struck the viewer as a rather tame, even somewhat restrained, spontaneity, yet how forceful must have been its antiritualistic, anti-Confucian implications. The viewer could perceive no hint of hierarchy, no apparent decorum, when confronting eight carefree, lounging figures en déshabillé, all the same size, all seated at the same level.

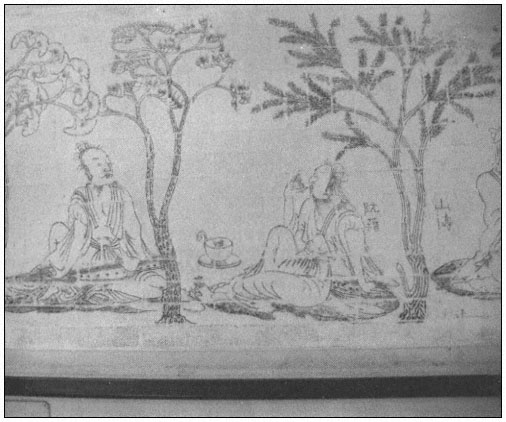

How simple it all seems, and how delusory the simplicity! For if the roots of the composition lie in Cao Pi's literary depiction of conviviality, why are the eight men not depicted in a group?[46] Mats do not touch and wine cups are not passed from hand to hand. Each figure, rather, is self-contained and isolated from all others by trees (fig. 35). It is precisely this compositional isolation that expresses the men's remoteness and purity—each like a solitary pine tree—ascribed to

35.

Xi Kang and Ruan Ji.

Detail of figure 2.

them in the literature. It also objectifies, at least in part, that sense of composure or tranquillity intuited by the viewer.

Paradoxically, these lolling, whistling, drinking figures, with their robes in disarray and their partial nudity, are dignified. Wang Rong carefully, delicately, balances his ruyi on his fingertips, his posture and clothing asserting utter relaxation.[47] The insouciance, the composure, are elegant. Xi Kang sits with ramrod-straight back and fingers gracefully poised above his zither, his bared limbs and tousled robe adding that touch of casualness that suggests complete and natural mastery of his instrument. A pictorial convention traceable to Han dynasty art, the qin placed across the lap not only enhances the sense of

remoteness, but hints at a decorum not apparent at first glance, for the instrument cannot actually be played in this position, but must be placed on a firm table for performance. In the context of death, this qin seems not only one of music without sound but a "silent comforter."[48] Similarly, the isolation of each figure whispers at decorum. "He who is in mourning should sit on a single mat," the Rites instruct.[49]

Casual yet controlled, relaxed but restrained—the very style of the figures reinforces the message. Firm, continuous lines form slender bodies, as well as robe contours that gently curve inward to define, for example, Ruan Ji's leg, Xi Kang's knee, or Wang Rong's arm, and to suggest, not only weight of cloth, but a slight tension of the muscles beneath. The relatively few interior lines—long, smooth curves evenly spaced—of the robes where the body is covered add to the sense of repose. They form a strong contrast to the many curves of drapery that fall to the ground in scalloped swirls or flutter to the sides in loops, as if weightless and in motion.[50] The combination of firm, unmodulated, slow curves of body outline with drapery curves that break into swirls and points effectuates the sense of tranquillity in action, of utter composure under all circumstances. Moreover, the absence of texture or pattern in the garments (such as we see, for example, in the ribbons attached to Ruan Xian's balloon-guitar) virtually forces the eye to focus on this combination.

The absence of spatial setting, the absence of texture, the absence of any sense of weight or of volumes in space—what is missing from the composition is as important as what is there. For these figures are beyond time and space. Reality is not in their appearance but in its interpretation. As Dai Kui claimed, they are transcendent.

Each figure is accompanied by an inscribed brick that names it. By definition, then, each figure is a portrait, a picture intended to be like an individual. Yet., as I have demonstrated, all eight figures are depicted in exactly the same way: they are all alike. Physical likeness cannot, therefore, have been intended. The act of naming, of course, is itself a literary device; each name is an allusion that evokes in the knowledgeable viewer a host of historical and literary events and traditions associated with each image. The pictorial devices, however, are more selective; by virtue of their presence (and the absence of others, clearly available), only certain events or traditions should come to mind. It would be absurd, for example, to suggest that the figure of Xiang Xiu (figs. 23 and 24), slumped against a tree, is a pictorial allusion to his reply to Xi Kang: "To look at your shadow and sit like a

corpse with rocks and trees as your neighbors . . . I have never heard it was fitting."[51]

Composition, imagery, and style conspire, rather, to evoke in the viewer associations that confirm these depictions as character portraits, the external expression of inner qualities, innate and unalterable. The very absence of any spatial setting that might, for example, define a man's wealth or status (such as we see in many Han-period depictions) imposes the conviction that the most important information about these men lies within them alone.[52] It is from their behavior, from their style, as Liu Shao warned, that we may know the men in the reliefs.[53] All eight are seen to have the same character. From their attributes, their postures and gestures, indeed from the very lines that form the figures, we know their inner qualities: outstandingly able and refined, untrammeled and pure, self-possessed.

With no spatial setting, by posture and gesture, and by style, the many Han portraits of Confucius and Laozi, of filial sons and dutiful officials, of exemplary recluses, all preached the importance of Virtue. With similar devices, the Jin-Song portraits of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi preach less obvious, and very different, values: ziran, spontaneity, detachment, freedom; and yaliang, restrained, or elegant, composure.[54]

The controversial issues of the third century reached pictorial fruition in the fourth. The reader may recall that Cao Cao sought only talent, but that his grandson demanded something more. The Nanjing mural is the earliest extant pictorial expression of a social ideal, the cultivated gentleman.

Style and the Man

"Truly, those who are not free and detached cannot find pleasure in it; those who are not profound and serene cannot rest quiet in it; those who are not liberated cannot abandon themselves to it; those who are not of the utmost refinement will be unable to discern its principles."

Xi Kang's words make it clear that the joys of the qin are not for every man. Only those with special inner qualities are capable of appreciating it. Such were the qualities of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi as they were portrayed on the walls of the tomb in the capital city. How different from those countless Han portrayals of virtuous creatures great and small! For Virtue was the supreme, universal

value of the Han era, its demands and expression clear to everyone. High and low, men of all classes could practice it, praise it, even gain by it if they chose: it was inclusive. Peasant and courtier, eunuch and scholar—none could fail to grasp the significance of Han portraits.

The Anak and Liaoning portraits, some two hundred years later, were equally clear and universal in their messages. This was not so for the Seven Worthies' collective portrait. Profound, serene, imperturbably untrammeled: who could aspire to be a cultivated gentleman, to appreciate the qin, to chant the poetry of the past or create his own, to impress with his witty allusions? And who but only another cultivated gentleman could have the perspicacity and experience to recognize such a one when he met him? The new portrait was, indeed, not for every man. It was art for the elite and meant to exclude.

I have presented many accounts of the Seven Worthies to establish what the men of Jin-Song thought of them. I turn now to the men themselves. From this small exercise in social history, I shall attempt to identify, among the many competing political factions, those who admired the Seven Worthies and upheld the social ideal they had come to represent. We shall find that in the world of Eastern Jin there were some who modeled themselves on the Seven Worthies as they were depicted in the Nanjing tomb, and who, in their turn, became exemplars for their contemporaries and successors. We shall find, too, that others attributed to the new exemplars the same characteristics they saw in the Seven Worthies. Finally, we shall see that the traditions that developed about the men of the Bamboo Grove were put to rhetorical use, and that the Nanjing portrait(s) had political resonance. Thus does life mirror art.

The tradition of the Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove belonged to the northerners, to be embellished and circulated by those who crossed the river. That it became an ideal to be used in the rivalry between the northern and southern aristocrats is evidenced by one anecdote:

Hsieh Hsüan [Xie Xuan] held his elder sister, Hsieh Tao-yün [Xie Daoyun], in very high regard, while Chang Hsüan [Zhang Xuan] constantly sang the praises of his younger sister, and wanted to match her against the other. A certain Chi Ni [Ji Ni] [visited both families]. When people asked him which was superior and which inferior, he replied, "Lady Wang's (i.e., Hsieh Tao-yün's) spirit and feelings are relaxed and sunny; she certainly has the manner and style of (the Seven Worthies) beneath the (Bamboo) Grove. As for the wife of the Ku [Gu] family (i.e., Chang Hsüan's sister), her pure heart gleams like jade; without a doubt she's the full flowering of wifely virtue."[55]

Let us note first the emphasis on a pervasive activity of the period, the comparing and judging of people. The otherwise unknown Ji Ni is not recommending the ladies for official appointments. The issue, rather, is one of social status, in which the Lady Wang, daughter of a prominent émigré family and married into another such family, is pitted against one connected with two equally prominent southern families. The northern contender, herself a well-known poet, is likened to the Seven Worthies, who, in the judge's adroit balancing of scales, are here equal to gleaming jade. Note too the different, yet evenly weighted values: the northern Lady Wang has the manner (feng ) and style (qi ) of the Seven Worthies, while the southern Lady Gu receives the accolade for Virtue.[56]

An especially revealing source for understanding the value placed on the manner and style of our exemplars is the Buddhist literature of the period. In the south, Buddhist proselytization focused on the aristocracy, and missionary activity found a home in the salons and country retreats of the men who threw open their lapels and unfastened their girdles to debate, with erudition and wit, the philosophical issues of the day.[57] Needless to say, the native and foreign monks who moved in these circles required considerable talent and learning to win respect and adherents.

Without question, the early biographies of Buddhist monks were hagiographic, drafted with an eye to associating the missionaries with native Chinese thought, with Chinese eminents and their values.[58] When, therefore, we read that Sun Chuo (fl. 330–365), a leading Buddhist layman, compared seven Buddhist monks with the Seven Worthies, we may be sure that the choice of exemplars was no accident.[59] Chuo's contemporary and friend, the redoubtable Zhi Dun (314–366), for example, he likened to Xiang Xiu, for both admired the Zhuangzi and the Laozi. Although born in different times, the two were "mystically one." He compared Zhu Daoqian to Liu Ling, the great translator Dharmaraksa to Shan Tao, and so on. No events in the biographies of these monks evoked the comparisons with the Seven Worthies, save for the life of Bo Yuan (fl. 304), who, like Xi Kang, was executed—unjustly, of course.[60] Rather, it was their characters, their essential natures, that Sun Chuo compared. Thus, Bo Yuan and Xi Kang, "careless of their frames and beyond worldly concerns," invited the retribution of a base world. Zhu Daoqian, remote and profound, like Liu Ling, took the universe as his dwelling. "How alike in their vast, untrammeled manner!" We hear naught of wine vats, slave girls, or lice. The seven monks equaled the Worthies

because of their shining intelligence and virtue, because they were lofty and remote, because each was spiritually one with his secular counterpart.[61]

Sun Chuo established the saintly images of these fathers of the early Buddhist church, of these exemplars to the faithful, by comparing them with secular exemplars. He did not compare the seven monks, of varying ethnic and social origins, with Confucian sages or loyal ministers. Seven cultivated gentlemen, tippling poets and officials, were his choices. To whom did he expect his equations to appeal? Why, indeed, did they appeal to him personally?

From a northern family whose members had held high office for several generations, Chuo was highly rated by his contemporaries as a man of literature. Famous for his characterizations of others, his evaluation of himself (requested by the future Emperor Jianwen) is of interest:

[When it comes to] deliberating on policies suited to the times, or ways of ruling the present world . . . for the most part, I don't approach [others]. On the other hand, precisely because I'm untalented, I set my thoughts . . . on the Mysterious and Transcendent . . . and intone from afar the words of Lao-tzu and Chuang-tzu. Lonely and aloof in lofty retirement, I don't concern my thoughts with temporal duties. I myself feel that in this attitude I yield to none.[62]

Scorning the dust of the world, Sun Chuo retreated to the lush landscape of Guiji (modern Shaoxing in Zhejiang province), where for several years he enjoyed the reclusive life with a large circle of eminent friends. It was a life, that is, rather less lonely and aloof than might be thought from his high-minded remarks. Despite his expressed attitude, Sun Chuo emerged from retirement to serve in various official positions throughout his life. Since neither Chuo's father nor his uncles served in office, his access to appointment—or his summons, if one prefers—may have been gained through his highly placed contacts at Guiji.[63]

Certainly, his family name and his literary talents equaled those of his cohort. Unlike many of his friends (or their fathers or their uncles), however, he lacked, in these early days, enfeoffment or official appointment. He refers to himself in a letter as a hanshi, one without rank or wealth (although humble rhetoric should, of course, never be taken at face value).[64] We read, moreover, that some considered him to be vulgar or an upstart, one who presumed to be closer to holders of wealth and power than he really was.[65]

Much of this attitude toward Sun Chuo appears to stem from the ambiguities of his behavior: on the one hand, an extoller of aloof retirement, on the other hand, a too eager seeker of office. Note the different attitudes toward him and Xu Xun, another recluse, who never accepted office: "Those who honored Hsü [Xu] for his exalted feelings would correspondingly despise Sun for his corrupt conduct, and those who loved Sun for his literary ability and style would conversely have no use for Hsü."[66]

The excoriation of Sun Chuo for duplicity is surprising. Eremitism, as I have noted, was much en vogue (which is not to deny the serious intent of many), and the records of EasternJin are replete with accounts of gentlemen in retirement who, at some point, answered the call to duty. Yet many whose lives alternated between retreat and court were not criticized in the manner of poor Sun Chuo. In this period, moreover, when temporary retirement was so frequent a political necessity, the concept of the recluse in society—one who outwardly engaged in public life while inwardly maintaining his detachment—was especially powerful.[67] When the danger had passed, a man could hardly be expected to cast aside his essential purity, his very nature, as he returned to public life. In the third century the famed recluse Zhuge Liang earned no calumny when he emerged to serve as Liu Bei's minister; nor did his contemporaries criticize Shan Tao for returning to office following a period of retirement. As for later attitudes, we know already that Sun Chuo praised Shan Tao's lofty remoteness and that his cousin, Sun Sheng, admired him for his sound judgment:

Shan T'ao's cultivated tolerance [ya su ] was untrammeled and free, and his judgment vast and far-reaching. His mind remained beyond the realm of worldly affairs, yet he stooped and rose with the times. He once had a relationship with Hsi K'ang and Juan Chi which transcended words. But whereas all the other gentlemen encountered difficulties in the world, T'ao alone preserved his vast overflowing judgment.[68]

The matter of Sun Chuo's "corruption" and "vulgarity" warrants continued interest. We read, for example, that Xie Wan (ca. 321–361) had a disagreement with Sun Chuo over the former's "Discourse on Eight Worthies," in which four recluses were paired with four men of the world.[69] One of the pairs comprised the recluse Sun Deng and a worldly Xi Kang, whose violent death Deng had predicted.[70] "Xie Wan's general idea was that recluses were superior and men of affairs inferior. Sun Chuo objected to this, saying, 'For those who embody

the Mysterious and understand the Remote, public life or retirement amount to the same thing.'"[71]

It is easy to conclude that Chuo's argument was, after all, his apologia, which the high-minded Xie Wan rejected. However, we are entitled to wonder whose apologia was whose when we recall that Wan had held several important offices and eventually "crowned an ignoble military career" with an overwhelming defeat at Shouchun in 359.[72] Thereafter he was stripped of all titles and rank and went into involuntary, permanent retirement. Whereupon, the family fortunes were rescued by the emergence from retirement of Wan's elder brother, and Sun Chuo's friend, Xie An.[73]

One of the most famous men of the century, Xie An did much to establish the foundation of his family's later preeminent social status.[74] He is credited with saving the throne from usurpation and, after, with saving the empire from invasion; for many years he was the power behind the throne.[75] No one was more admired in his day, or so we are told, and it is to this exemplar that I now turn for instruction.

Like his friend Sun Chuo, Xie An had elected to live in retirement at Guiji, where his family owned large estates. Together with other friends, such as Wang Xizhi (309–ca. 365) and the Buddhist monk Zhi Dun, they often gathered to converse or to discuss the philosophical issues of the day.[76] At such times, the art of Pure Conversation was highly prized, and adepts vied to produce the cleverest epigrams or to outdo each other in debate. At one gathering, An urged the assembly to "speak, or intone poems, to express our feelings." Choosing the Zhuangzi as their topic, all held forth. Zhi Dun's ideas were "intricate and graceful, the style of his eloquence wonderful and unique, and the whole company voiced his praises." When all others had finished, Xie An spoke:

The peak of his eloquence was far and away superior to any of the others. Not only was he unquestionably beyond comparison, but in addition he put his heart and soul into it, forthright and self-assured. There was no one present who was not satisfied in his mind. Chih Tun [Zhi Dun] said to Hsieh [Xie], "From beginning to end you rushed straight on; without any doubt you were the best."[77]

Such was the tenor of life in retirement. Far from the capital, reputations could nevertheless be made. Not only was An the best debater, but there was also the purity of his determination: for some six or seven years he roamed the mountains and forests without a care. "When summoned to office he did not go. Even though summonses

and memorials came in swift succession, followed by threats of imprisonment, he was blissfully disdainful of them all."[78] Wang Xizhi went so far as to state that he was superior even to the famous recluse Xu Xun.[79]

Yet, far from the capital, a man's leadership qualities could shine forth. When Xie An was out boating one day with Sun Chuo, Wang Xizhi, and others,

the wind rose and the waves tossed . . . the others all showed alarm in their faces and urged [returning] to shore. But Hsieh An's [Xie An's] spirit and feelings were just beginning to be exhilarated, and humming poems and whistling, he said nothing. The boatman, seeing that Hsieh's manner was relaxed and his mood happy, continued to move on without stopping. But after the wind had become more and more violent and the waves tempestuous, everyone was shouting and moving about and not remaining seated.

Hsieh calmly said, "If it's like this, let's go back."

Everyone immediately responded to his voice, and they turned back. After this it was realized that his tolerance was adequate for a governing post, either at court or in the provinces.[80]

Thus could a man's behavior and style earn him fame. Xie An was refined, pure, and self-possessed. His judgment was outstanding. He was to continue to exhibit these qualities when, in the end, he left Guiji to heed the summons to office—perhaps because he no longer dared to refuse, perhaps to save the dynasty, or perhaps because he owed it to his family.

Of course, not everyone thought he was the essence of purity. When An arrived in 360 to take up his post as aide to his enemy Huan Wen (312–373), the latter taunted him for hypocrisy.[81] Years later, however, Wen's son, Xuan, inquired about this from Xie An's niece, Daoyun. The lady explained:

My late uncle . . . in his early conception of what is correct, took "uselessness" for his cardinal principle, and considered public life versus retirement to be a contrast of inferior versus superior. It was not until his mature conception of what is correct that he considered them to be merely the difference between activity and quiescence.[82]

Like Shan Tao, An stooped and rose with the times, and we read his own apologia in the anecdote in which he asks the young people of his family to choose the finest passage in the "Book of Songs." His own choice: "With mighty counsels he determines the Mandate / With farsighted plans he makes timely announcements." The passage,

he added, "uniquely contains the profoundest sentiments of the cultivated (ya ) man."[83]

The cultivated man therefore preserves his vast overflowing judgment and discerns the correct moments for activity and quiescence. Whether in retirement or at court, he maintains his inner detachment and far-reaching judgment. The Nanjing mural is a collective portrait in the sense that the images of eight men are used to convey the full significance of the recluse. Did they not, in their life histories, span a spectrum, from the total retirement of Rong Qiqi to the complete immersion in public life of Wang Rong? Yet did they not all share the inner qualities of detachment and purity, and did they not all reveal these inner qualities by their untrammeled and thoroughly self-possessed manner? Similarly, Xie An, in the circumstances of his life, embodied these qualities. He was the cultivated gentleman, the exemplar for all seasons.

If there is an exemplar, surely there must be a counter-exemplar to enlighten us further. Indeed, we have already met him in the person of Huan Wen, who suspected Xie An's purity. Little is known of the Huan family prior to Wen's father, Yi.[84] Wen, a military man like his father, rose rapidly, however, to become grand marshal and the real power behind a puppet emperor. Only his death in 371 prevented him from attempting to usurp the throne.

Wen had a low opinion of those who enjoyed philosophical discussion while he, a rugged and disciplined man of action, coped with military affairs. "If I didn't do this," he once admonished Liu Tan, "then how in blazes could you fellows get to sit around and talk?" As for living in retirement, he was appalled by the thought. "Who could be so petty and perverse as to live by himself?"[85]

For all his rejection of those values his political opponents admired, he nevertheless respected his enemy, Xie An. Once, during Wen's illness, An called on him. "Huan, gazing at him from a distance, sighed, saying, 'It's been a long time since I've seen such a man in my gate.'" Judging him, Wen remarked that An, "as one would expect, is inviolable; his very position is naturally superior."[86]

It should not be thought that Huan Wen was without admirers of his talents. After his pacification of the state of Shu in 347, for example, he entertained his staff and the local families in the palace.

Huan had always had a martial disposition and vigorous air, and moreover on this particular day his voice and intonation rang out heroically as he told how from antiquity to the present "success or failure have proceeded from

men," and survival or perdition are bound up with human ability. His manner was rugged and flint-like and the whole company sighed . . . in appreciation.

After the meeting . . . everyone was still savoring its flavor with continued conversation. At the time Chou Fu [Zhou Fu] said, "What a pity you fellows never saw the generalissimo, Wang Tun (d. 324)."[87]

Forthright, heroic, flint-like: surely a character worthy of emulation. Furthermore, Huan Wen, in this version of the tale, is likened to a gentleman of the prestigious Langya Wang clan. All present, however, knew that Wang Tun [Wang Dun] had rebelled against the throne. The allusion could not have been lost on those assembled.[88]

The anecdotal material I have presented may objectively relate events that actually occurred and remarks that were actually made. It may, on the other hand, comprise only kernels of historical truth modified or altered to fit a certain point of view. It is well, therefore, to pause here and discuss that point of view and its significance for my tale.

The great majority of quotations are selected from that literary masterpiece of the fifth century A New Account of Tales of the World, the Shishuo xinyu (SSXY ). It is a work of art in its own right, as well as a remarkable exercise in social history, one not unworthy of comparison with Proust's masterpiece.[89] It is not a work of history, although almost all of its characters are known, from other sources, to have existed, and there is no doubt of the historicity of many of the events to which it alludes.[90] Yet the compilers of the Sui and Tang dynastic histories classified it, not under the Division of History, but under the Division of Philosophers. Under that rubric, they placed it with Minor Tales (xiaoshuo ), in the company of fictionalized biographies, jokebooks for court jesters, and, significantly, source books for advisers to the throne.

The SSXY is, in short, fictionalized history—exemplary fiction. It has a point of view, from which some of its characters are seen to be better or more admirable than others. This is not the same as noting that the book has a hero, who of course has enemies, a fact apparent from even the most cursory reading. Since it chronicles, for the most part, the Eastern Jin world of elite factions that hummed at court, it is not surprising to find protagonists and antagonists aplenty. Superficial reading, however, fails to discern few, if any, differences between the two categories of characters. Only more refined study enables the reader to grasp the essence of the true exemplar and to understand why others, of like class and rank, are found wanting. If this is not

apparent at first, it is because the SSXY is a work of subtlety, relying far less on plot than on allusion, pun, and metaphor to convey its messages. Not everyone can understand it, nor was everyone meant to.[91]

Not its historicity, but, a near paradox for the historian, the point of view or bias of the SSXY enables us to determine what kind of patron might have commissioned the Nanjing mural. Obviously, only one who admired the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi and who wished to be associated with them would have done so. Just as obviously, however, it must have been one who was concerned with the specific values conveyed by the pictorial form, one, that is, who admired the concept of the cultivated gentleman, and who himself wished to be, or to be seen as, one such. It is precisely this image that the literary form celebrates, for its most important hero exemplifies these values above all others in his, or anyone else's, circle.

The undoubted hero and primum exemplum of the SSXY is Xie An. Its counter-exemplar is Huan Wen. No direct statement reveals this. Rather, the descriptions of the behavior of the two men, the judgments other characters in the book make of that behavior, and the allusions linking them to still other individuals enable us to discern their roles in what seems to be merely a loose collection of random anecdotes. The true point of the tale of Huan Wen in Shu lies in the allusion to the traitor Wang Dun.

In the fourth century Sun Chuo considered the Seven Worthies so potent an ideal that he wished Buddhist monks to be admired in the same way. Others of the time—for example, Gan Bao and Dai Kui—had opinions about them, favorable and otherwise. We have observed, as well, that many anecdotes about them were collected in the fifth-century SSXY. They appear in the book not only as actors, however, but also as individuals to whom others are compared. It is instructive to examine a few of these allusions:

While Wang Meng and Hsieh Shang [Xie Shang] were serving together as officers under Wang Tao's [Wang Dao's] administration, Wang Meng once remarked, "Officer Hsieh here can perform an unusual dance." Hsieh immediately got up and danced, his spirit and mood both utterly composed. Wang Tao watched him intently, then said to the other guests, "Makes a person think of Wang Jung [Wang Rong]!"[92]

Xie Shang (308–357) was a cousin to Xie An and served successively as vice-president of the Imperial Secretariat, governor of Yu Province, and General Governing the West. The favorable compari-

son was made by the great minister and kinsman of Wang Rong, Wang Dao.[93] Sun Chuo once characterized Xie Shang as "pure, yet easygoing; genteel, yet uninhibited."[94]

The eminent recluse Xu Xun once observed that "in (Xi Kang's) essay on the qin, 'Those who are not of the utmost refinement will be unable to discern its principles' is Liu Tan. And the one meant by the line 'Those who are not profound and serene cannot rest quiet in it' is Emperor Jianwen."[95]

We need not doubt that Xu Xun intended the reference as a compliment to both men. The emperor—is the emperor; Liu Tan (311–347), although poor as a youth, was a descendant of the Han royal family and brother-in-law to Xie An. Sun Chuo once characterized him as "pure, yet luxuriant; unceremonious, yet genteel."[96]

Once, when Liu Tan and Wang Meng were both present at a banquet, the latter, "slightly in his cups, got up and performed a dance. Liu said to him, 'Meng, old chap, today you're not a whit behind [Xiang Xiu]!'"[97] Wang Meng's daughter was the consort of Emperor Ai and became empress in 362.

There are thus linkages between individuals of the fourth century and various of the Seven Worthies.[98] And it is surely no accident that all the figures noted above have linkages—political, marital, social—with the Xie family. One final anecdote links Xie An with one of the Seven Worthies and clearly demonstrates his superiority, not only over his adversary, but also over an important ally, a Taiyuan Wang:

Huan Wen held a feast with armed men concealed about the premises . . . with the intention of killing Hsieh An [Xie An] and Wang T'an-chih [Wang Tanzhi]. . . . Wang was extremely apprehensive, and asked Hsieh, "What plan should we make?"

Hsieh, his spirit and mood showing no change, said to Wang, "Whether the Chin [Jin] mandate survives or perishes will be determined by this one move."

As they went in together, Wang'sfears grew more and more apparent in his face, while Hsieh's cultivated tolerance became more and more evident in his manner. Gazing up the stairs, he proceeded to his seat, then started to hum a poem in the manner of the scholars of Loyang, reciting the lines by Hsi K'ang [Xi Kang], "Flowing, flowing mighty streams." Huan, in awe of his untrammeled remoteness, thereupon hastened to disband the armed men.

Wang and Hsieh had hitherto been of equal reputation; it was only after this that they were distinguished as superior and inferior.[99]

Thus, our exemplar: whether in retirement or in public life, he remains the cultivated gentleman. The cultivated gentleman—not the filial-pious, not the Confucian erudite—disarms the enemy and saves the dynasty. All see him as superior.

Time Remembered

It is tempting to conclude from the above that the occupant of the Nanjing tomb must have been an adherent of the Xie political faction. However, we do not know the date of the tomb, and the architectural evidence suggests a construction date somewhat later than the events referred to above, when, after Xie An's death in 385, new alliances and perils confronted the throne. Since the firmest date for construction, late Eastern Jin to early Liu-Song, covers a span of perhaps fifty years, the question of patron seems more complicated. Were the tomb constructed during the early Song period, for example, would there be any possible justification for asserting that the tomb occupant chose to link himself—albeit metaphorically, yet publicly—with earlier events, with one family and their allies, and with their ideals? Would not such an identification be viewed by an upstart dynasty as a statement of defiance?

Such would most certainly be the case had the ideal of the Seven Worthies remained parochial, a stereotype identified with only one group—for example, northern émigrés, or with specific families within that group—for example, Langya Wangs, Taiyuan Wangs, Xies, and so forth. There is evidence, however, that by the end of the century the cultivated gentleman had become a pervasive ideal, a persona to which many aspired. It is precisely because of its early associations with powerful families that others were to adopt it as their own.

I have noted that in the wake of the flight to the south, it was not difficult for a man of ability to seize the opportunity to establish a reputation. Associating oneself with men of power through friendship, marriage, or political alliance, one could gain appointment, wealth, and, with time, social eminence.

A man of great talent but small pedigree might easily gain wealth and power. Acceptance by others with wealth and power is then readily obtained. Acceptance by those with wealth, power, and impeccable pedigree, however, is more difficult. Sun Quan, smart and powerful, lost no time in arranging marriages between members of his family and the southern aristocrats; the latter, for their part, saw where the power lay and acted accordingly. That, after all, was what daughters were for.

But let us return to our exemplar, Xie An, his wife a descendant of Han dynasty emperors (or so it was said), his niece the wife of an impeccably pedigreed Langya Wang. Who could be more socially prominent? Since An was so powerful and so admired, an arbiter of fashion, is it not then astonishing to read that Ruan Yu (ca. 300–360),

Ruan Ji's kinsman and one who admired Xie An, considered the family to be upstarts?[100]

We know, of course, that the Seven Worthies were prominent men of the third century, that Ruan Yu, without wealth or power, could nevertheless boast of eminent ancestors. Had not Sima Zhao admired and protected his poet-cousin? And had not the latter been so prominent that he was selected to write the epistle urging Zhao to accept the throne?[101] Where had the Xies been then? They were not entirely unknown in the third century, but their rise to prominence began only when they crossed the river.

Therefore, when Xie An remarked that if his famous uncle Xie Kun (280–324), who had prospered after fleeing south, "should ever meet the Seven Worthies, they would undoubtedly seize him by the arm and lead him into the Grove," we have reason to interpret this as a positive association.[102] Xie Kun, the reader may recall, was a member of the "Eight Free Spirits" who were charged with emulating the Seven Worthies, but who were considered by both critics and admirers of the latter to be self-indulgent.[103] Yet the linkages I have established—between Wang Dao and Wang Rong (Langya Wangs) and the son of Xie Kun, Shang, for example—suggest that An meant this as a positive characterization. It was not that he saw both Xie Kun and the Seven Worthies as self-indulgent; rather, his kinsman was spiritually one with the latter.

Xie An, as we have seen, emulated the spirit and manner of the Seven Worthies. We must remember, of course, that such talent was inborn and that no environmental considerations could alter its fundamental character. By identifying his prominent ancestor with an ideal, did he not lay claim to his right to the succession? No upstart really, but one, rather, born to the manor/manner? He came by it, that is, naturally. His wife once asked him, "How comes it that from the start I've never seen you instructing your sons?" "I'm always naturally instructing my sons," he replied.[104]

The above is especially interesting in view of the fact that the Xie family's social progress closely paralleled that of the Huans. Not much was heard of either family prior to the move south. Huan Yi (275–328), Wen's father, was also a member of the "Eight Free Spirits" and thus a friend of Xie Kun's. Wen's younger brother, Chong (328–384), married a granddaughter of Wang Dao's; Wen's son, Huan Xuan, married a daughter of Liu Tan's. In short, there were few differences in either background or current status to differentiate the two families.[105]

There is one difference: someone wrote a book about the Xie family, from the Xie point of view.[106] In this Chinese predecessor of a Western movie, the forces of civilization are always outstandingly able; untrammeled, pure and remote; elegantly self-possessed—and admiring of the Seven Worthies. Outlaws, of course, don't appreciate these qualities. Thus the only difference between the two families, at least in the telling, is one of style.[107]

All students of Chinese history know who won the political struggle between the Xies and the Huans. The Xies won in other ways as well, for by the end of Eastern Jin their social eminence rivaled that of the Langya Wangs. They were the most cultivated gentlemen of the realm, and many aspired to be like them. In the new world of the south, where the old claims of birth could not always be validated, legitimacy acquired a new form. What was inside a man, his character, established his right to preferment, at least in theory. However, just as in the period of Latter Han when the landed magnates obtained a lien on virtuous character, so by the end of Eastern Jin was the newly valued character suborned. For the behavior that signaled one's inner being depended largely upon one's education.

Huan Wen's son Xuan is an example of the new ideal. Although he was a military man like his father, we nevertheless do not hear of his heroic, flint-like manner. We read, instead, of his literary talents and his love of art.[108] He had the right attributes, as it were. And although his father scorned reclusiveness, this usurper of the throne took a different view of that social role. Noting that all great dynasties of the past had had their recluses, whereas he, the self-proclaimed king of Chu, had none, Huan Xuan summoned a descendant of Huangfu Mi's, Xizhi, and ordered him to retire in order to write. Then, offering him an appointment, Xuan ordered him to decline to serve, so that Xizhi might gain a reputation as a virtuous scholar. Men of the time called the poor man the "phony recluse" (chongyin ).[109]

Thus did the next generation strive to observe the new conventions. Of course, a biased source cannot be expected to award Xuan full marks. His character had one significant flaw. Although talented and free, he could, alas, never hide his emotions—he was not truly detached and self-possessed.[110] He tried, however: With victory in his grasp, Huan Xuan, the new usurper, stood aboard his ship. As bugles blared and drums thundered, he chanted aloud lines from a poem by Ruan Ji, in vague historical allusion to his own conquest. A modern commentator perceptively terms the allusion "somewhat forced, to say the least."[111] Huan Xuan had chosen the wrong moment and the

wrong way to emulate others with his cultivated reference. How different was the style of Xie An when he received the news of the great victory over Fu Jian. "An read the letter in silence, and without saying a word, calmly turned back to his [chess game]." When his guests inquired about the news of the battle, he replied, "'My little boys have inflicted a crushing defeat on the invader.' As he spoke his mood and expression and demeanor were no different from usual."[112] With such subtle comparisons did our source employ its rhetoric, not merely to amuse its readers but to sway them. The style of the telling was an interpretation—a man's character adduced from his behavior—and that interpretation had social and political impact, for we are left in no doubt about which man was fit to lead.

We may characterize Huan Xuan as lacking style. The indiscriminate art-collecting, the appointment of an official recluse, the chanting of famous poetry amidst the crashing noises of victory—he knew the conventions, but he seems not to have come by them naturally. He was, all in all, a trifle vulgar. Ars est celare artem.

I cannot, in view of the above, argue that the Nanjing tomb was built for a member of the Xie faction. The problem is far more complicated, and I am inclined at this juncture to see it as a burial place for one who, perhaps not quite so powerful and not quite so eminent, sought to emulate his betters and to be remembered as one of them—a cultivated gentleman. Perhaps he sought the beneficial influence of the portraits on his own character, like one Tian Yu, who, in the third century, asked to be buried next to an ancient worthy whose "course of conduct was in exact contrast to mine; if the dead have influence, then he will certainly endow me with virtues."[113]

Covering a period from approximately A.D. 25 to 420, the SSXY was compiled by Liu Yiqing (403–444), a nephew of the military founder of the succeeding Liu-Song dynasty. As the Nanjing mural is court portraiture, so the book is court literature. Its hero is Xie An, and one may well wonder why, after the first Song emperor had finally put an end to the factional struggles of the fourth century, anyone—and specifically a member of the victorious imperial family—would wish to commemorate those struggles. It has been argued, successfully to my mind, that the actual compilers of the book, staff members to the prince, had close connections to a collateral descendant of Xie An, the great poet Xie Lingyun (385–433).[114] It was they, rather than the prince, so the argument runs, who thus chose to honor their gifted but reckless friend, who had been executed for treason.[115] Be that as it may, their patron must have approved the work; lacking evidence, we

cannot know why. For the younger generation, however, perhaps the passage of time had reduced the brutality of the earlier struggles to amusing memories. The prince's uncle had himself put an end to Huan Xuan's pretensions, and the Xie family was now entrenched as one of the foremost families of the realm. They held high office, were wealthy, married into the imperial family.[116] But true power lay elsewhere, with the throne, which is to say with upstart generals.[117] I suggest that Prince Liu Yiqing may have found these tales both amusing and instructive (as did the men of the later Sui and Tang dynasties), and that he saw in Xie An, not an old family enemy, but a model for a prince—one who was outstandingly able, free, and selfpossessed.

The Most Difficult Painting

Although the Nanjing relief of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi may not have been the first of its kind, it was, I suspect, one of the earliest. It soon became a pictorial stereotype, as we know from the recently excavated Danyang murals, and its potency as an ideal in Chinese history is demonstrated by the repeated use of its pictorial conventions throughout that history.[118]

I shall discuss those conventions and their significance for Chinese portraiture in the final chapter. I must not, however, close this discussion of the Nanjing portrait before taking note of other portraits that are said to have been made during this period.

The SSXY mentions several, while the later Lidai minghua ji offers many examples. Xie Zhi (fl. early fifth century?), for example, is said to have painted pictures (tu ) of filial sons, of Confucius's ten disciples, of the mother of Mencius. Portraits (xiang ) of Sima Yi, founder of the Jin dynasty, as well as those of famous ministers of the Wei kingdom, are also mentioned.[119] Gu Kaizhi, to note but a few listed by Zhang Yanyuan, painted portraits (xiang ) of Huan Wen, Huan Xuan, and Xie An, and Dai Kui portrayed the Confucian disciples and Sun Chuo.[120]

The subjects thus include traditional Confucian figures, historical personages of more recent times, and contemporary figures. Only rarely are the functions of the paintings noted.[121] Unfortunately, none of them is described and we do not know what they looked like.

Our extant portraits, however—the examples from the northeast of China and the Nanjing mural—are the true evidence for portraiture

of the period. There is no need to assume that their forms are all-inclusive. It is obvious, however, that what remains warrants the conclusion that more than one form and style existed at the time, and that portraiture of the period was, to be sure, character portraiture, but character portraiture of an exemplary nature. The official portraits from Liaoyang and Anak are retardataire only in the sense that older values continued to prevail in the region, while at the capital, in court circles, new values came to the fore, not to replace the old ones entirely, but to vie with them and to give life to a new persona or image worthy of emulation by many of the governing class.

We cannot know what the portraits of the Huans, father and son, or of Xie An looked like. Were they portrayed as loyal ministers, or in the case of Huan Xuan, as the king of Chu? Or were they, rather, portrayed as cultivated gentlemen? The occasion must have determined the choice. I do not think that a portrait of Xie An as loyal minister, for example, would have looked like the inventions of the Seven Worthies mural. On the contrary, it would have looked like the forms from the northeast, or perhaps like the bowing, submissive Han-period forms of Confucius's disciples.[122] Furthermore, the character of the man would have been instantly recognizable to all who saw the portrait.

If the portrait were intended, however, to convey something more complex—a man with a character of outstanding ability, whose detachment and inner purity could permit him, at the right time, to enter the fray (as Confucius could not bring himself to do)—then, I submit, the portrait of Xie An would have resembled the Nanjing images. When Gu Kaizhi painted An's uncle, Xie Kun, among crags and rocks (i.e., as living in seclusion), the rocks are an allusion to Xie's persona and a choice of considerable social significance.[123]

Moreover, the character of the man would not have been universally recognizable, for only those within elite circles would have understood. It is precisely for that reason that I believe the original of the Nanjing mural to have been based on a painting by an artist familiar with the values and conventions of circles at court. It is not a question of technical skill alone (the relief itself indicates the high level of craftsmanship available in the capital); rather it is one of sophistication: the subtle understanding of, as well as the ability to subtly convey, subtle ideas.

The bowing form, the gesture of submission, and the ceremonial dress were adequate to convey a man's (public) character in the Han dynasty. For artists and artisans of the later period, the depiction of a

man's character required greater subtlety. How, indeed, does one pictorially objectify a man who exemplifies such values as spontaneity and detachment, tranquillity and self-possession? Our analysis of the Nanjing portraits has shown us the pictorial solution to the problem.