6

Gandhian

Gandhi was still present throughout India, in his achievements, his example, his image. For Europe, he was simply a liberator with clean hands; a symbol of saintliness, with the quaintness that goes with many saints: an obstinate nun with a big toothless smile, dressed in a humble plebian garment worn like the uniform of freedom.

André Malraux, Anti-Memoirs

To comprehend Romain Rolland's intellectual politics in the period 1923–1932, we must treat the ambiguities of his engagement as a Gandhian. Since the publication of his biography of Gandhi in 1924, over four hundred books about Gandhi have been released. Today, Gandhi's name and face are so familiar that it is hard to envision a time when he was not part of our consciousness. But before the French writer popularized his image—fusing anti-imperialism, the nonviolent political philosophy, and the holiness of his life—Gandhi was an obscure Indian lawyer, unknown in continental Europe or America.

Romain Rolland's critique of imperialism emphasized that Europe's destructive tendencies, so visible during the Great War, were active in the colonized regions of Asia and Africa.[1] The civilizing rhetoric of imperialism veiled nationalistic and expansionistic aims, the will to amass wealth and to subjugate weaker societies. "Under the mask of civilization, or of a brutal national idealism, the politics of the great States methodically practice fraud and violence, theft and degradation (rather, extermination) of the so-called inferior peoples."[2] Throughout the interwar period, he protested European imperialism and predicted that the awakening nations would turn this violence against the Europeans themselves. Imperialistic aggressors would inevitably be confronted with anti-imperialistic aggression, which might finally engulf Europe. If this happened, Europeans were ultimately responsible.[3] Romain Rolland sought

some intermediary between the imperialistic and anti-imperialistic forces, between East and West. Progressive intellectuals of Europe and developing countries might be able to "use their hearts and geniuses" to work toward nonviolent solutions to imperialistic injustices. Because struggles for national liberation might unchain cataclysmic forces, he urged intellectuals to preserve an "Island of Calm," to not be swept away by the destructive passions.[4]

Opposition to war was meaningless unless buttressed by opposition to imperialism. The Great War and the Treaty of Versailles convinced Romain Rolland that imperialist rivalries were creating the conditions for another world war. In one issue of Clarté he signed a public indictment of the French suppression of the Riff rebellion in Morocco and condemned all wars unequivocally.[5] The oppressive reality of "brutal and greedy imperialism" would provoke a counterattack, unleashing insurrectionary movements in Asia and Africa. The revolutionary dynamic of decolonization would not necessarily follow a Bolshevik model. Anti-imperialist movements might turn against the Soviet communists, perhaps to follow another path of historical development.[6]

All critical inquiry into imperialism should rely on accurate, firsthand information. Most crucial, it should grasp the totality of the situation by considering the perspectives of "both the conquerors and the conquered." The historical destinies of colonizer and colonized played decisive roles in struggles for self-determination and in the construction of independent societies. For Romain Rolland, imperialism derived from the expansionistic policies of military elites and venal capitalists: the "imperialism of armies and of money."[7] He understood that French involvement in Morocco and Syria was strategically designed to protect French interests in Algeria. That was no longer a legitimate aim:

[Algeria's] conquest was the fruit of an extortion, and to defend that conquest, it is necessary to commit in turn other extortions, other crimes against the independence of native peoples. If the conqueror stops on the road and wavers, all his conquests totter; all Islam rises in insurrection. And who can calculate the ensuing ruins, not only for France but for Europe?[8]

Gandhi's political philosophy offered one humane solution to the multiplication of imperialist and anti-imperialist aggression.

Gandhi's democratic and conciliatory methods were preferable to the Soviet model as a way out of the "iron net" of imperialist domination and privilege: "It would be necessary as certain great-hearted men have discussed—such as Gandhi and some magnanimous Englishmen—that both antagonists should consent to make mutual sacrifices and to treat together in a spirit of kindness and abnegation this terrible question on which depend the life and death of both." The Gandhian path moved toward international cooperation, redress of the grievances of colonized nations, and a negotiating mechanism to satisfy the mutual needs of the imperialist powers and the countries seeking independence. Romain Rolland advocated the Gandhian route but had few illusions about the reception of these nations by Western governing elites. He knew "the blindness and obstinate pride of the great States."[9]

Anti-imperialism included a defense of civil liberties. His 1926 appeal in favor of a jailed Vietnamese writer supported the absolute right of the colonized to freedom of speech. He also denounced the French presence in Indochina, and he advocated national independence. If "loyal collaboration" between the French and the indochinese occurred, intelligence and mutual resources might be shared. Independence should not mean a total rift. Vietnamese students and workers in Paris ought not to imitate Western violence and insensitivity. Movements of national liberation should repudiate all forms of racial pride and nationalistic prejudice. Europeans could struggle with the Indochinese in their fight for self-determination, if both sides accepted an "equality of rights and duties."[10]

Romain Rolland's anti-imperialism was fundamentally Gandhian. His denunciation of imperialism was often harsh and violent, but his remedies left the door open for dialogue between East and West. His intention was to circumvent the massive dislocations and random violence of struggles of national liberation and the efforts to repress them. The real work of creating a durable society could begin only after the struggles ended. Romain Rolland's anti-imperialism was also accompanied by an uncompromising opposition to pan-European ideas, such as a United States of Europe,[11] and by recurring pressure for revision of the Treaty of Versailles.[12]

In the interwar period, the isolated pockets of French and European pacifists bestowed enormous prestige on Romain Rolland, calling him "the conscience of Europe" because of his antiwar

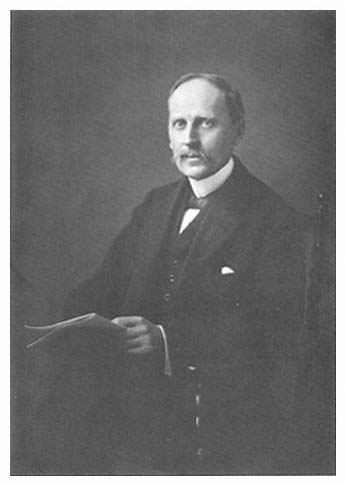

Portrait of Romain Rolland at about the age of forty.

Romain Rolland on the balcony of his Left Bank apartment

in Paris during the time he was writing Jean-Christophe .

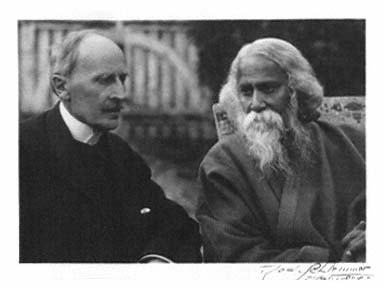

Romain Rolland with Rabindranath Tagore

in Villeneuve, Switzerland, 1926.

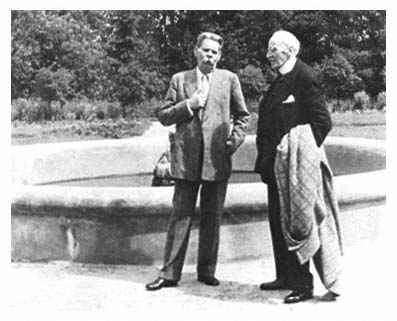

Romain Rolland with Stefan Zweig, his Viennese

biographer and friend, Villeneuve, Switzerland, 1933.

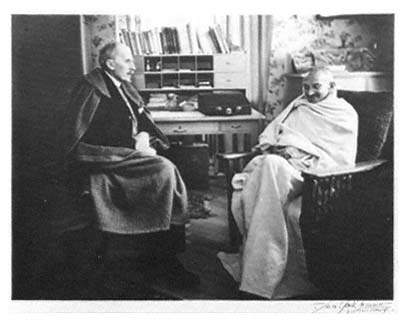

Photograph of Romain Rolland with Mohandas

Gandhi, Villeneuve, Switzerland, December 1931.

Romain Rolland with Maxim Gorky, in the vicinity of Moscow, July 1935.

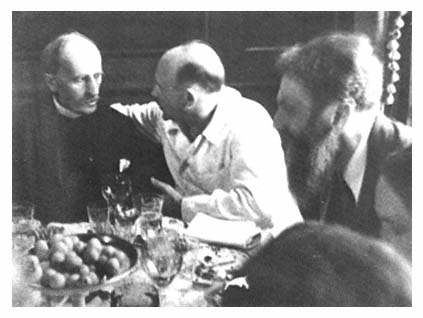

Romain Rolland with Nikolai Bukharin and Otto Schmidt

during his visit to the Soviet Union, summer 1935.

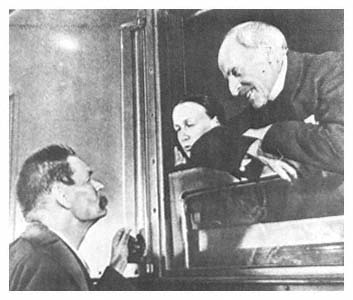

Romain Rolland and Madame Marie Romain Rolland with

Maxim Gorky at the Moscow railroad station, July 1935.

stance during the First World War.[13] His introduction of Gandhi and his dissemination of the nonviolent political philosophy further reinforced his stature. He was a paternal figure and pioneer with unassailable pacifist credentials, an authority within the anti-war movement. Pacifists regarded him with affection, even if they were unaware of his latest position. They repeatedly asked him to clarify internal disputes and external dilemmas; to write interventions, petitions, declarations, manifestos, prefaces; and now and then to contribute money to rescue a failing antiwar periodical.[14] Romain Rolland debated continuously in the interwar era with pacifist intellectuals along the entire spectrum of pacifist sentiment and ideology—educators, mothers, scholars, Tolstoyans, anarchists, Christians, and advocates of disarmament and conscientious objection.[15]

Romain Rolland seldom missed an opportunity for a symbolic gesture to oppose war or to deflate the arrogance of the militarists. When the Chamber of Deputies passed a conscription law in the spring of 1927, and French right-wing Socialists such as Joseph Paul-Boncour collaborated in supporting the bill, he published a blunt oath of conscientious objection. The worst oppression of all was the militarization of intelligence by the state:

The monstrous project of military law, audaciously camouflaged by the warmongering pacifist verbiage of several Socialists, and voted by sleight of hand at the French Chamber, last March 7 [1927], claims to realize what no imperial or Fascist dictatorship has yet dared to accomplish in Europe: the entire slavery of a people from the cradle to the tomb.

I swear in advance never to obey this tyrannical law.[16]

In "The Duty of Intellectuals Against War," he again advocated intellectual independence from institutions and parties. Intellectuals were exhorted to be "look-out men" for the eventuality of war. Thinkers were enjoined to go beyond impartiality, beyond the "laborious and scrupulous exercise of intelligence." Protest was linked to action.[17]

Romain Rolland was not the first French writer to look to the East for inspiration or consolation or the first to compare the Orient

with a materialistic, declining Occident.[18] He was, however, one of the first French intellectuals to conceive of modern India as a challenge to European political reality and global hegemony. He was drawn to the East because it differed from the violence and cultural stalemate of the postwar West. His meditation on India renewed the spiritual inquiry that had been interrupted by the world war and immediate postwar issues. Romain Rolland's Gandhian phase was, in part, a flight from sociopolitical preoccupations into oceanic metaphysics.

The Orient offered attractive regenerative possibilities for Europe; Indian thought might give receptive Europeans ontological as well as political options, introduce them to an alternative ethical system, encourage them to rethink their discredited values. The otherness of India could assist demoralized Europeans in rediscovering and tolerating their own otherness, thus initiating inner growth without precipitating anxiety or the need to dominate on the part of the Westerner. Romain Rolland's discourse on India emphasized similarities between East and West as well as the traditional contrasts. He discovered an exemplary personality to represent the East: a man of purity and self-sacrifice, a "great-souled" individual who was himself engaged in an epic political experiment. Romain Rolland mythologized Mohandas Gandhi into "the Mahatma."[19]

Unlike earlier Orientalists, Romain Rolland was convinced that European imperialistic domination of India must end. Empire building led to expansionism, imperialist rivalries, bloody suppression of native populations, and ultimately to war. The colonizers imposed their language, educational system, and cultural values on other civilizations. It is difficult to disentangle Romain Rolland's moral and political critiques of imperialism.[20] He recognized that European empires were crumbling and that movements of national liberation would eventually triumph. He hoped that decolonization would not reenact the violence of the colonizing impulse but would contain an explicitly internationalist dimension, rejecting the ethnocentrism of imperialist domination.

Gandhi provided Romain Rolland with a tentative solution to his dilemma as a committed intellectual in the 1920s, an ideological alternative to Bolshevism, and a corrective to postwar European pacifism. No matter that his political orientation was not

pragmatic, or that his cultural writings crossed the boundaries of fiction. Romain Rolland became a self-appointed citizen of the world, mediating between East and West from his exile in neutral Switzerland. In the process he contributed the first documented study of Gandhi and modern India, using largely Indian and British sources.[21]

Romain Rolland's writings on India in the 1920s were not received in a total vacuum. A spate of books by Orientalists had appeared in France.[22] Between February and March 1925 the Parisian periodical Cahiers du mois sponsored an exchange entitled "The Appeals of the East." Twenty-two celebrated writers commented on the interpenetrability of Eastern and Western ideas, taking a position on the "grave peril" or value of Eastern influences on the West.[23]

Although writers such as Henri Barbusse and André Breton argued that interpenetration would be beneficial,[24] most participants adopted the stance of Paul Valéry, a lucid spokesman for the French conservative intellectual establishment:

From the cultural point of view, I do not think that we have much to fear now from the Oriental influence. It is not unknown to us. We owe to the Orient all the beginnings of our arts and of a great deal of our knowledge. We can very well welcome what now comes out of the Orient, if something new is coming out of there—which I very much doubt. This doubt is precisely our guarantee and our European weapon.

Besides, the real question in such matters is to digest . . . . The Mediterranean basin seems to me to be like a closed vessel where the essences of the vast Orient have always come in order to be condensed.[25]

Action Française writer Henri Massis remained hostile to Eastern influences and preoccupied with defending the West against foreign contaminants. His integral nationalistic stand favored the restoration of French will and grandeur, the preservation of its mental, religious, and geographical purity. He alleged that Romain Rolland's interest in Gandhi and Indian culture was politically motivated. Asian idealogues only weakened France, created disorder, and consequently played into the hands of hostile political forces such as Japan, Germany, and the Soviet Union. Receptivity to Eastern culture was nothing less than intellectual treason.[26] In a transparent display of cultural nationalism and contempt for the for-

eign, most of the writers argued that the East had far more to gain from exposure to the West, that East-West barriers were unmodifiable, and that limited exchanges ought to be guided by academics or Oriental specialists, not amateurs or propagandists.[27]

Romain Rolland replied, limpidly, "Where Henri Massis is, Romain Rolland cannot be."[28]

To Romain Rolland, the assertions of most participants in the debate were tinged with superiority and Eurocentrism, proving that French thinkers were rigidly closed to dialogue. They desperately needed an infusion of Eastern sources, and he was prepared to stand alone to promote substantive East-West exchange.[29] He used his connections to publish works by Tagore and to keep abreast of Indian affairs; he opened his home to prominent Indian visitors. He welcomed the works of Hermann Hesse, whose novels (particularly Siddhartha , the first part of which was dedicated to Rolland) irrefutably proved that Europeans could fathom Hindu thought.[30]

In humanitarian appeals during the same period, Romain Rolland attacked French nationalism and promoted Franco-German reconciliation. He responded to developments in Weimar Germany by writing from the perspectives of those suffering, the victims of runaway inflation, hunger, the military occupation of the Ruhr, political arrest, and indiscriminate hatred of Germans. If the French, from their postwar position of strength, failed to redress German grievances resulting from the unjust peace treaty and other punitive policies—failed to be sensitive to the desperate plight of the Germans—they would sow the seeds of German revenge, preparing to reap the next war.[31]

Romain Rolland was introduced to Indian thought in February 1915 in a series of letters from the Hindu writer Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In becoming the European spokesman for Indian culture, he hoped both to regenerate postwar Europe and to avoid a fatal East-West clash resulting from mutual ignorance and stereotypes.[32]

As early as October 1916, he supported the work of the Nobel Prize—winning poet Rabindranath Tagore, whose 1916 "Message from India to Japan," a denunciation of European imperialism and

the exclusively political and material foundations of European civilization, Romain Rolland addressed hyperbolically as a turning point in world history.[33]

The theme of Asian-European cross-fertilization permeated his thinking on India. In correspondence and discussions with Tagore, Romain Rolland stressed cultural exchange and advised against the imposition of either civilization on the other.[34] He was more concerned with cultural revitalization than with concrete problems of power relations.[35]

Gandhi's heroism contrasted with the absence of visionary leaders in Europe:

That Gandhi's action of twenty years in South Africa has not had more reverberation in Europe is a proof of the incredible narrowness of view of our political men, historians, and men of faith: for his efforts constitute a soul's epic unequaled in our times, not only by the power and constancy of sacrifice, but by the final victory.[36]

An infusion of Eastern ideas might rekindle the old humanist torch. Romain Rolland did not propose to adopt Oriental forms of thought indiscriminately, however; they should be assessed impartially. He entertained high hopes that Europe , the review ostensibly founded under his patronage, would publish such assessments and propagate the ideas, but his hopes were dashed by the editors' refusal to publish Tagore's novel A Quatre Voix . This incident led to a temporary falling-out with Europe , though the "charming novel" was subsequently published by the Revue européenne in 1925.[37]

Romain Rolland first learned of Gandhi through conversations with Dilip Kumar Roy in August 1920.[38] The tentative nature of his defense of nonviolent noncooperation in the second open letter of the Rolland—Barbusse debate, in February 1922, mirrored his tentative knowledge of Gandhi and the Indian struggle for liberation. When asked in August 1922 to write an introduction to the French edition of Gandhi's Young India , he wanted initially to decline. Gandhi's spiritualized nationalism lacked the breadth of his own internationalism. Such important subject matter required more than a superficial treatment. He therefore postponed any writings on Gandhi in order to read about and reflect on Gandhi's mode of thought and action.[39]

With the assistance of his sister, Madeleine Rolland, Romain

Rolland (who neither spoke nor read English) spent the latter half of December and all of January 1923 reading Gandhi's texts. These included Indian Home Rule , articles in Young India , and writings from Gandhi's South African struggles. He was aided by the Indian academic Kalidas Nag, an intimate of both Gandhi and Tagore. Nag, Tagore, and others encouraged him to visit India.[40]

Gandhi and his French biographer had significant affinities. They were of the same generation—Gandhi was born in 1869; Romain Rolland in 1866. Both were influenced by and had corresponded with Tolstoy. Both emerged from their experiences in the Great War with an aversion to violence and warfare.[41]

If Romain Rolland was enchanted with Gandhi's blend of individualism, activism, and morality, he was equally troubled by Gandhi's distrust of science, his nationalism, and his nostalgia for preindustrial times.[42] Fascination far outweighed hesitation, however, and Romain Rolland planned a biographical portrait of the Indian leader modeled on his immensely successful Beethoven (1903). He wrote a short, easily digestible narrative essay centering on Gandhi's life and message, designed to acquaint as many readers as possible with the Gandhian movement. It was first published in three installments in the new Parisian monthly Europe , from March to May 1923, before it was released in book form in 1924.[43]

Gandhi's staunch opposition to oppression, particularly the British colonial variety that Gandhi had encountered both in South Africa and in India, became the connecting thread in the essay. His often indiscriminate attack on Western civilization derived from the brutality of British colonial rule, "written in the blood of the oppressed races, robbed and stained in the name of lying principles." Gandhi associated modernity and progress with domination and simplistically pitted the spiritual East against the acquisitive, technological West.[44]

Romain Rolland found the religious foundations of Gandhism reassuring. He drew on traditional Christian vocabulary to describe Gandhi and his movement, pointing to the similarities between Gandhi and Christ, St. Francis, and St. Paul to reinforce any religious associations the European reader might make. Since the nonmolestation of all forms of life had the standing of a categorical imperative, those who engaged in Gandhian resistance were acting spiritually. "Real noncooperation is a religious act of purification."[45]

Gandhi's methods demonstrated a capacity for tactical flexibility. His political philosophy contained a gradual theory of stages. In his campaigns there was first a concerted effort to work through legal means, employing negotiation and compromise to redress grievances. Only after exhausting legal resources, petitions, newspaper propaganda, and agitation by students, farmers, and the working class did Gandhi permit more disruptive, illegal tactics. Noncooperation moved from one level of resistance to another, increasing the degree of militancy at each level. Its campaigns were highly selective and cautious. Gandhi considered civil disobedience a legitimate but extreme form of noncooperation that should be focused on specific laws. Because personal risk was great and self-control was required of the resister, civil disobedience was applicable only when all other alternatives had been explored and was feasible only for the reliable elite.[46]

The concept of noncooperation was powerful and timely: Gandhi understood that "noncooperation can and must be a mass movement." His refusal to yield to the forces of the criminal state was not an infantile negation but an assertion of India's pride in herself. As Romain Rolland observed: "India had too much lost the faculty of saying 'No.' Gandhi returned it to her."[47] Gandhi appreciated the necessity for political organization and leadership; his strategy was a sophisticated staged program of cultural action employing meetings, demonstrations, fasts, and prayers, as well as music, national symbolism, and traditional Hindu imagery to guarantee maximum political efficacy.[48] Moreover, Gandhi demonstrated a shrewd sense of timing and propaganda and was adept in winning sympathy for his movement, both in India and among progressives in England.

Absolute sincerity of commitment was proved by the persecutions Gandhians suffered in all their campaigns. Gandhi himself had been imprisoned three times by 1923. Gandhism could be distinguished from other political ideologies by the moral restraint built into its doctrine, by the tendency of Gandhian resisters to circumvent power clashes whenever possible. Gandhians viewed their opponents as potential converts, if not allies, and tried to persuade the enemy by demonstrating the "irresistible" moral rightness of their positions.[49]

The most striking example of Gandhi's rejection of political expe-

diency came in February 1922, after the riots at Chauri Chaura. In this small village eight hundred miles from Bardoli province, where Gandhi prepared to launch his mass civil disobedience campaign, a violent confrontation took place on 5 February between his followers and the local police. After provocation by the constables, the crowd retaliated by burning the police headquarters and murdering twenty-two policemen. Learning of the episode on 8 February, Gandhi immediately suspended the Bardoli campaign of civil disobedience. He made this choice against the advice of other Indian political leaders and despite the willingness of the rank and file to carry on with its more assertive action. The English government initially considered Gandhi's judgment an act of folly. It arrested him on 10 March 1922.

Romain Rolland contrasted Gandhi's tactical choice with repressive policies in Europe, including current Bolshevik practices. He stressed the purity, self-mastery, and silent suffering required of the Gandhian resister:

To create the new India, it is necessary to create new souls, souls strong and pure, which are truly Indian and wrought out of Indian elements. And in order to create them it is necessary to form a sacred legion of apostles who like those of Christ are the salt of the earth. Gandhi is not, like our European revolutionaries, a maker of laws and decrees. He is the molder of a new humanity.[50]

Gandhi had generated a powerful momentum within the ranks of his movement. It is unclear how far this movement could have gone in 1922. As a contemporary commentator, Romain Rolland understood that the initiation and abrupt halt of the Bardoli campaign crystallized the ambiguities at the core of the Gandhian movement.[51] Nevertheless, he congratulated the Mahatma on his choice, thereby underlining the precedence of the spiritual over the political in his mission: "The history of the human conscience can point to few pages as noble as these. The moral value of such an act is exceptional. But as a political move it was disconcerting."[52] If Gandhi's acceptance of personal responsibility for the Chauri Chaura episode was naive, his penitential fast was a magnanimous gesture of legendary proportions.

The balance sheet of the biography was mixed. Though conceived in the genre of haute vulgarisation , it was not simply hagiography or

propaganda. Gandhi's opposition to science and technology and his exaggerated hope in cottage industries were historically regressive, a feature of Gandhi's messianic approach to immediate conflicts. Other policies recalled the cloister of medieval monks, most particularly his xenophobic attitude toward other cultures. Romain Rolland had not visited India or learned its languages. But his writing on Gandhi proved that civilizations could interpenetrate.[53]

He also disapproved of Gandhi's puritanical outlook. The severe restrictions on sensual gratification and abstention from sexual intercourse were reminiscent of St. Paul's hostility toward the body.[54] Gandhi's personal saintliness did not obliterate the erotic and aggressive urges of less disciplined men and women. Because of his own freedom from "the animal passions that lie dormant in man," or perhaps because of his overcompensation for them, Gandhi denied the human potential for violence, including violence to self.[55] His answer to perennial reliance on cruelty was an exceptionally high standard of behavior. Conspicuously lacking the redeeming features of their master, many of Gandhi's disciples had vulgarized the doctrine, substituting discipline for idealism, dogma for principles, and above all narrowness for Gandhi's emphasis on the attainment of truth through experimentation.[56] Romain Rolland noted the aggression in much of the discourse of nonviolence: "Tagore is alarmed and not without reason at the violence of the apostles of nonviolence (and Gandhi himself is not exempt from it)."[57]

Not without disclaimers, his portrait underscored that Gandhi's message to the world was as urgent as it was great. Whether that message was peace, noncooperation, nonviolence, or voluntary self-sacrifice, Gandhi recaptured the full potential of Indian liberation. If his successes were studied and his techniques emulated in other battles against oppression, India's special message might be extended to the peoples of the world. His political instrument was equally the most humane technique known to history: nonviolence. For the biographer, Gandhism symbolized a universal hope and a political alternative to the pervasiveness of force in the West. It could give to the demoralized pacifists a vigorous faith and an experimental tactic for change. Taken by the immense power of the doctrine, Romain Rolland announced his own conversion to the principles of Gandhian nonacceptance. Anticipating scorn from the left and right, he asserted that Gandhi's methods had proved their value for

the social battles to come. The real enemy in the nonviolent struggle was the resister's personal weakness and lack of conviction:

The Realpolitikers of violence (whether revolutionary or reactionary) ridicule this faith; and they thereby reveal their ignorance of deep realities. Let them jeer! I have this faith. I see it flouted and persecuted in Europe; and, in my own country, are we a handful? . . . (Are we even a handful? . . . ) But if I alone were to believe, what difference would it make for me? The true characteristic of faith is—far from denying the hostility of the world—to see and believe in spite of it! For faith is a battle. And our nonviolence is the toughest struggle. The way to peace is not through weakness. We are less enemies of violence than of weakness. . . . Nothing is worthwhile without strength: neither evil nor good. Absolute evil is better than emasculated goodness. Whining pacifism is fatal for peace: it is cowardly and a lack of faith. Let those who do not believe, or who fear, withdraw! The road to peace is self-sacrifice.[58]

In "Gandhi Since His liberation," Romain Rolland stressed the strengths of Gandhi as an adversary of British imperialism and of nonviolence as a political weapon. This piece informed European readers of Gandhi's two-year imprisonment, the rupture of his direct influence on Indian politics, and his subsequent release on 2 February 1924. Gandhi had elaborated a four-part program for national independence and social reform, the objectives of which were (1) work toward Indian home rule through the unity of Hindu and Moslem factions; (2) spinning as a remedy to Indian pauperism and as a pragmatic way to extricate India from economic dependence on Britain; (3) the disappearance of Untouchability; and (4) the methodical application of nonviolence in both propaganda and deed, including civil disobedience as a last resort. Gandhi opposed the British government and struggled against imperialism, while distinguishing between the English people and their administrators. He also realized that while colonization had ruined India's economy, decolonization would cause hardships on British industrial workers in Manchester: "A Gandhi is one of the very rare men capable of rising above the interests of individual parties in struggle and of wanting to seek the welfare of both."[59]

Romain Rolland's "Introduction to Young India " revised the point of view of the biography. The Gandhi presented here is decidedly more Mazzinian, complex, tragic, and ultimately more revolutionary than in the earlier portrait. "Nonviolence . . . in other words the

political nonviolence of the Non-cooperator [is] a reasoned method of peaceful and progressive revolution, leading to Swaraj , Indian Home Rule." He underlined the interlocking role of experimentation and direct action in Gandhi's politics. However, those who opted for class struggle and violence were also engaged in an experiment. Without judging which experiment was more viable for India or applicable to Europe, the French writer urged the partisans of violence to be "honorable" and "unhypocritical" in elaborating their strategy and tactics. Feeling an affinity between communists and Gandhians, he refused to dismiss the courage and idealism of violent revolutionaries: "Between the Mahatma's nonviolence and the weapons of revolutionary violence there was less separation than between heroic noncooperation and the sterile ataraxia of the eternal acceptors."[60] Satyagraha, insistence on truth, was based on the laws of active love and voluntary renunciation. Gandhi was different from passive, sentimental, "nerveless" European pacifists. Romain Rolland now emphasized the rational and accessible nature of the Mahatma's message, as well as the mystical side. The doctrine was also experimental: "But we must dare. Gandhi dares. His audacity goes very far."[61] Gandhism was characterized as an open-ended struggle, full of dangers for the half-believer, unsuitable for the individual who could not endure extended periods of self-discipline. "Nonviolence, then, is a battle, and as in all battles—however great the general—the issue remains in doubt. The experiment which Gandhi is attempting is terrible, terrifyingly dangerous, and he knows it."[62]

Romain Rolland's essays on Gandhi illustrated the positive attributes of the Mahatma's character and the wide possibilities of organized nonviolence. The point of view is best understood as noncommunist; Bolshevik and Gandhian methods were compared in just three brief allusions in the biography.[63]

As with his other biographies, he spent approximately six to eight months researching Gandhi's life and only three weeks composing the text. His small volume on Mahatma Gandhi sold extremely well in France (thirty-one printings in three months, at least 100,000 copies in the first year) and was translated into Russian, German, English, Spanish, and three Indian dialects by 1924 and into Portuguese, Polish, and Japanese by 1925. The critical

reception in Paris was apathetic.[64] By 1926, nevertheless, a fiftieth printing was published. The biography was clearly a best-seller.

The French communist reaction to his introduction of Gandhi was politically inconsistent. In the midst of the Romain Rolland-Barbusse debate, the communist author Ram-Prasad Dube focused on the social aspects of Gandhi's movement in India, drawing a parallel between Gandhism and the European anarchosyndicalist movements. He praised Gandhi's expertise in propaganda and agitation and his willingness to engage the mass movement in illegal tactics but predicted that Gandhi's politics of concession to authority and the perfection of the individual would ultimately fail. Gandhi would be remembered chiefly as the initiator of the first stage in India's social revolution.[65] One year later, L'Humanité published a far more critical article by the Indian Marxist revolutionary and representative to the Comintern, M. N. Roy. Roy held that the Gandhian movement was socially suspect, composed of members of the "reactionary petite bourgeoisie." It was neither anti-imperialist nor committed to complete Indian independence. To harness the energy of the "revolutionary spontaneity of the masses," an indigenous Communist Party was necessary. Roy looked to the Indian leader C. R. Das to provide the Indian left with leadership and a radical direction. The country simply could not afford to become captive to Gandhi's moralism and theology.[66] Later, in March 1923, L'Humanité published an editorial signed by the executive committee of the Communist International. While condemning British imperialism and their fierce reprisals against the Indians for the Chauri Chaura incident, the statement carefully excluded criticism of Gandhi or his movement.[67]

Romain Rolland's portrait of Gandhi triggered a clever, if inaccurate, rejoinder by Henri Barbusse that blurred the political and ideological antagonism between Gandhism and Bolshevism. Following the pattern of the earlier polemic, Barbusse's article "Eastern and Western Revolutionaries: Concerning Gandhi" praised the spirit in which Romain Rolland wrote his essay. Although it opened communications between Europe and Asia, his "magisterial and lyrical study" of Gandhi nevertheless misrepresented the formal opposition between Gandhi's doctrine and that of Western revolutionaries. Barbusse asserted that Gandhi belonged on the side of the Third International. His intransigence, utilitarianism, and practicality indi-

cated that "Gandhi [was] a true revolutionary."[68] As a pragmatic idealist with a realistic understanding of Indian political constellations, Gandhi, without being aware of it, was "very close to the Bolsheviks."[69] His verbal vilification of communism resulted from his unfamiliarity with Marxist doctrine and misinformation about communism in the Soviet Union.

In Gandhi's activities as a popular leader and his defense of the working and agricultural masses of India, Barbusse found a form of class struggle.[70] Noncooperation was irrefutable revolutionary activism, not passivity. Gandhi's ability to suspend his movement at a crucial moment after the violence of Chauri Chaura only dramatized the immense authority of the Mahatma over 300 million Indians.[71]

Barbusse emphasized that nonviolence was merely a provisional tactic.[72] If Lenin had been in India, he too would have spoken and acted as Gandhi did: the two "are men of the same species, prodigious characters, who know how to measure for and against."[73] The spectacle of the Indian masses agitating for their sovereignty shared many similarities with the Russian experience. Gandhi's goals were identical to those of Lenin's, namely, a society in which privileges would be eliminated, where people could live a peaceful, egalitarian life. Their methods were alike: "Lenin is for constraint—and Gandhi also."[74]

Gandhi would evolve closer to the Communist International's concept of a professional, socialist revolutionary. His grasp of the value of organization, leadership, and discipline added to his intimacy with the Indian popular multitudes did not contradict contemporary communist teachings. The only significant contrast between communism and Gandhism was Gandhi's patriarchal attitude towards labor, a residue of his repudiation of industrialization.[75]

Barbusse's article ended with a critique of Romain Rolland and Tagore. These "marvelous and admirable artists" telescoped social issues into individual categories. They overemphasized "moral values." The idealist hand Romain Rolland had extended to the East had to be politicized, by bringing the Eastern and Western revolutionary movements into closer contact. Gandhi himself was invited to participate in the "Left International" to guarantee the proliferation of his thought.[76]

On reading the first communist articles on Gandhi, Romain Rolland was moved to laughter. The slogan "petit bourgeois" was

abusive enough with reference to the Gandhian movement, but this "tarte à la crème of Communist language" took on a thoroughly ridiculous savor when applied to India. Because India's social structure was fundamentally agricultural, Marxist phraseology obscured more than it explained. There could be no "possible analogy" between the politics and class structures of Europe and Asia. Communist polemicists used "sleight of hand" to debunk Gandhi while overestimating the significance of the Indian communist movement.[77]

The second series of communist articles by Barbusse and the Indian Bolsheviks devalued the "true and holy grandeur of Gandhi." Unable to arrive at a consistent line on Gandhi, the communists presented contradictory theses that would only confuse the European audience. On the one hand, the communists characterized Gandhi as a religious utopian, a "chimerical being without practical intelligence." On the other hand, they portrayed him as "a prudent Bolshevik who use[d] nonviolence as a provisional expediency."[78]

Romain Rolland was equally disturbed by information he received from Russian friends about Soviet overtures to Gandhi, directed by M. N. Roy and other Indians of Bolshevik persuasion. If Gandhi were sufficiently informed, he would perceive the underlying opportunism that motivated these gestures. Under no circumstances should Gandhi be deceived and manipulated by the Bolsheviks. There was a fundamental antagonism between nonviolent and communist tactics as well as between the basic philosophies of the two doctrines. He alleged that the Bolsheviks desired a political alliance with the Gandhians to prop up their own power base in India. In the end, the communists had contempt for nonviolence and would either attempt to subvert it or crush it entirely.

Romain Rolland's intention was to introduce and transmit Gandhi as an independent thinker, without linking him to an existing social movement or political party.

I admire the intelligence and energy of the Bolshevik government; but I feel a profound antipathy for its means of action; they totally lack frankness. Its politics is to utilize, in its struggle to destroy the present European system, all the great forces opposed to European imperialism, even if these forces are also opposed to the system of Bolshevik oppression and violence. . . . Certainly I prefer Moscow

to Washington, and Russian Marxism to American-European imperialism. But I claim to remain independent of one as of the other. "Above the Battle!" The Civitas Dei, the city of nonviolence and of human Fraternity, must refuse every alliance, every compromise with the violent partisans of all classes and all parties.[79]

Romain Rolland was alarmed by the deliberate communist distortions of the spirit, internal dynamics, and goals of the Gandhian movement. They interfered with his own efforts to disseminate the Mahatma's message from a spiritual perspective consistent with the central foundations of the nonviolent movement. He urged C. F. Andrews, a British missionary and friend of Gandhi, to warn Gandhi about self-serving communist efforts to make procommunist propaganda within the Gandhian movement. Indian communists would infiltrate the nonviolent rank and file. Gandhi might also be invited to visit the Soviet Union and Germany. Above all else, he urged Gandhi to distinguish clearly his movement's motivations and aims from those of the Communist International.[80]

Gandhi acted directly on Romain Rolland's warning, delivered through Andrews. In his article entitled "My Path," published in Young India on 11 December 1924, he implicitly endorsed Romain Rolland's "Western" assessment of his doctrine and dissociated himself from communist interpretations. "It is my good fortune and misfortune to receive attention in Europe and America at the present moment." The good fortune was that his doctrine was made more accessible. But "a kind European friend has sent me a warning . . . that I am being willfully or accidentally misunderstood in Russia." The friend discreetly left unnamed was Romain Rolland. The biographer was now playing advisor, urging the subject of his biography not to be duped by the communist Machiavellians. Gandhi denied that he planned to visit the "great countries" of Germany or Russia. India was the main stage of his social experiment and "any foreign adventure" would be premature until his movement had succeeded in his native country. The Mahatma added that he was unsure of the precise nature of Bolshevism. "But I do know that insofar as it is based on violence and denial of God, it repels me. . . . There is, therefore, really no meeting ground between the school of violence and myself."[81]

Romain Rolland breathed a sigh of relief when he learned of Gandhi's categorical repudiation of Bolshevism in Young India .

That article ended the equivocation about the real nature of the nonviolent movement and terminated the hypocritical game of the pro-Soviet communists. Yet Romain Rolland regretted one aftereffect of Gandhi's statement—its manipulative use by the reactionary European press. The Parisian daily Le Matin exploited Gandhi's article as yet another weapon in their anticommunist crusade.[82]

Gandhi had made a powerful impact on Romain Rolland by the summer of 1924. Still strongly attached to his intellectual independence, the French writer felt obliged to make public statements not only to "relieve his conscience" but also to defend noncooperation, which he identified with a politics transcending party, class, nation, and force. He wrote: "It is clear that Gandhian noncooperation as an example will lead its apostles in Europe to sacrifice without any practical result—and perhaps for a rather long time. It is not less true and good in an absolute fashion; and it is the sole means of salvation for human civilization."[83]

During the period from February 1924 to September 1925, two significant events considerably affected Romain Rolland's relationship to Gandhi. The first was a postcard he sent to Gandhi excusing himself for inadvertent errors in his short biography.[84] This gesture initiated a unique epistolary friendship between the two that lasted until 30 December 1937. Second, he wrote a letter of introduction for a young Englishwoman, Madeleine Slade, asking Gandhi to accept her into his ashram. After reading his biography of Gandhi, she was converted to the Mahatma's philosophy, thereby discovering her life's mission. Slade not only became Gandhi's close disciple, but also remained the intermediary between Romain Rolland and Gandhi throughout the entire interwar period.[85]

Gandhi praised Romain Rolland's essay both for containing so few factual errors and for having "truthfully interpret[ed] my message."[86] Gandhi again expressed his satisfaction with the biography: "Tell M. Romain Rolland that I will try to live up to the high interpretation that he has given my humble life."[87]

Romain Rolland's idealization of Gandhi was bound to lead to disillusion. For ten years the personal contacts between Gandhi and his French biographer were marked by geographical distance, cordiality, and mutual respect, but also by consistently different conceptions of the world and their historic missions. Gandhi and Romain Rolland met only once. In truth, they had little in common.

Madeleine Slade mediated between Romain Rolland and Gandhi (the Mahatma neither read nor spoke French). Gandhi wrote letters of introduction to Romain Rolland for many of his colleagues and disciples traveling in Europe. They exchanged letters on birthdays. Romain Rolland often wrote before and after Gandhi participated in fasts, prayers, and marches or entered life-threatening periods of imprisonment.

Throughout this time, there were serious tensions between the two. Romain Rolland vehemently clung to his vocation of free-spirited intellectual. Gandhi did not see himself as a theoretician but rather as a popular Indian guru, devoted to his own brand of political and religious action. Gandhi's contribution to a festschrift for Romain Rolland's sixtieth birthday in 1926 stressed his own difference from his biographer. He wrote that he was not a man of letters and did not know a great deal about the French Nobel laureate. He also referred to Romain Rolland as "my self-chosen advertiser"—a distancing and slightly denigrating term.[88]

Romain Rolland emphasized his separation from the Mahatma's movement. He refused to become an official spokesman for Gandhi in Europe: "I am not a Christian, I am not a Gandhian, I am not a believer in a revealed religion. I am a man of the West who, in all love and in all sincerity, searches for the truth."[89] His motives in writing about Gandhi were personal; he felt called on to "relieve his heart." He wrote out of love, to present the Gandhian message to Europeans, alerting them to the possibility of a free and joyous choice. Wounded by the offhand remark Gandhi made about his biography (he supposedly said that it was "literature"), Romain Rolland countered that it was "not written for 'literature' (The littérateurs scarcely consider me as one of them)."[90]

In his private diary, the converted Romain Rolland entertained doubts about the realistic possibility for Gandhian nonacceptance being applied in Europe as early as November 1926. Nonacceptance could only be practiced by an elite corps of "apostles and martyrs." The faith required a well-trained, tightly disciplined band of self-abnegators. Nonacceptance might subvert the modern state if practiced over a long period of time, but in Europe only a minority of conscientious objectors possessed this faith, with the courage to sacrifice their lives, families, professions, and personal welfare for principles. To practice war resistance in an era of fascism and rearma-

ment was to risk persecution. Conscientious objectors would be harassed and punished. He observed that even Gandhi practiced his doctrine inconsistently, lacking the spiritual hardiness attributed to the early Christians.[91]

Europe could not survive without peace. But European pacifists were obliged to connect their antiwar activity to a larger effort to "revise the values of life." Gandhism represented a cultural revolution that might assist them to reevaluate politics, morality, and social attitudes by beginning with the self. Romain Rolland's pacifism, although it contained critical components, was essentially positive and character building. That is why he so deeply appreciated the sentiments of Spinoza's Political Treatise .[92] By the middle and late 1920s he recognized that the religious and political climate of Europe was "unsuited" for Gandhi's heroic experiment.[93] Non-violence promised salvation, but it had no roots in the industrial, secular, materialist West—especially in Latin Europe.

Their correspondence often debated Gandhi's views on war resistance. They had a brief controversy about two French peasants who resisted World War I and retreated into the mountains for thirteen years. The Mahatma refused to discuss the case in Young India . Romain Rolland, for his part, judged Gandhi's response to their action harsh and puristic.[94] This, in turn, gave rise to a more acrimonious exchange about Gandhi's role during the Great War, both his support of the British Empire and his active participation in the war. The French writer was dissatisfied with Gandhi's rejoinder in his Autobiography .[95] There were instances of "doctrinal narrowness" in Gandhi's message and a growing number of personal inconsistencies. Gandhi's justification of his activities during the Great War was not convincing; the Mahatma should have adhered to the strategy of individual civil disobedience.[96]

Romain Rolland urged Gandhi to visit Europe in the late 1920s to tell the anti-imperialist version of the struggle (Europeans usually heard only the viewpoint of the British Empire) and to enter into direct contact with other oppressed peoples.[97] On Gandhi's sixty-first birthday in 1930, he referred to Gandhism as a unifying "revolution of the spirit, . . . the refusal hurled by the proud soul against injustice and violence. . . . This revolution does not breed opposition between races, classes, nations, and religions; it brings them together."[98]

By 1931, Romain Rolland was writing more stinging indictments of European imperialism, largely in response to the social crisis engendered by the world depression. The language of pacifist engagement in the 1920s gave way to the revolutionary language of the 1930s. Europe's only hope, he exclaimed, was for a "complete reversal of the social order." Capitalist imperialism had to be toppled and replaced. Since Gandhism contained a revolutionary potential, he issued calls for a nonviolent revolution with Gandhi as leader.[99]

The warmth of their relationship peaked during Gandhi's five-day visit to the French writer's villa in Villeneuve from 6 December to 11 December 1931.

Historians have trivialized their conversations at this time by dwelling on the circus atmosphere that followed Gandhi's entourage (even Romain Rolland viewed ironically the incongruous assortment of nudists, vegetarians, crazies, lottery-card holders, and peasants bringing milk to the "King of India," who converged on his villa).[100] Most accounts mention the music and the metaphysics.[101] In fact, they discussed the political and economic crisis of Europe and the urgent necessity for Gandhi to clarify his views on social questions. Romain Rolland viewed Europe's malaise as deriving historically from the rivalries and expansionism of international capitalism. He asked Gandhi what options nonviolence posed for Europeans in the face of this crisis.[102] Rolland observed that nonviolence could work only if the resisters shared a common religious belief system. Nonviolence also required visionary leadership and a broad base of followers. For nonviolence to succeed in Europe, the organized workers in factories and arsenals would have to be mobilized. Workers, he alerted Gandhi, were already politicized, and many were inspired by events and the example of the Soviet Union. Most organized French workers were class conscious and prepared for class struggle, which might include violent confrontations. He pressed Gandhi for clarification of his perspectives on Italian fascism (Gandhi had chosen to visit Italy after leaving Switzerland), but above all on the clash between capitalism and the labor movement.[103]

Gandhi did not consider the antagonisms of labor and capital essential. If a collision occurred, he favored organized labor. The methods of satyagraha could be employed against capitalists, as he

had demonstrated in India. Gandhi appeared insensitive to the plight of unemployed workers in England and in industrialized countries: "In England's case the unemployed have not many reasons to complain of the capitalist." He seemed ignorant about developments in Russia. Without having studied the facts, he stated that he was distrustful of the USSR; that he associated communism with violence, arbitrariness, intolerance, and terrorism; and that he was unequivocally opposed to the dictatorship of the proletariat.[104]

In summary, Gandhi's visit had a mixed impact on Romain Rolland. He still revered Gandhi as a man, admired his sense of humor, stamina, leadership qualities, and self-control, but he felt removed from him. At times it seemed that they had nothing to discuss, that the formidable differences in their sensibilities, lifestyles, and cultural politics were unbridgeable. He was dissatisfied with Gandhi's faulty knowledge of pacifist and left-wing politics in Europe and deeply disturbed by the Mahatma's planned trip to fascist Italy. Most significant, he reluctantly endorsed Gandhi's positions on labor and class struggle.[105]

Italian fascism was a controversy, an embarrassment, and finally an impasse in Romain Rolland's relations with Gandhi. After being Romain Rolland's guest in Switzerland, Gandhi visited Italy for four days from 11 December to 15 December 1931. Gandhi's trip to fascist Italy repeated Tagore's Italian fiasco of 1926, with its elements of farce and tragedy. The French writer tried to persuade the Mahatma not to risk traveling in Italy. If he were foolish enough to go, he should take precautions against being "swindled" by the unscrupulous regime. He was entirely unsuccessful in explaining to Gandhi the symbolic dangers of visiting a fascist dictatorship in Europe, but it was contrary to his style to veto Gandhi's trip. Gandhi made only one concession to Romain Rolland: he resided with the independent General Moris, declining shelter from the official fascist establishment.[106]

Gandhi had been invited to Italy by the Italian consul to India. The Indian leader delivered a short address at the Institute of Culture in Rome. Ostensibly, Gandhi was motivated to visit Italy by his unabashed curiosity, his empirical desire to test out and observe Italy's political and social context for himself. Gandhi also asserted, somewhat self-righteously, that as a messenger of peace his presence in Italy would ultimately have a constructive effect on

the Italians. In Gandhi's words: "The distant effect of a good thing must be good." Before entering Italian territory, he requested that no secret meetings be held and that he be permitted to speak his mind freely in public. Gandhi's contact with Mussolini's Italy may have signaled to the British his bitterness after the collapse of the Round Table Conference designed to discuss Indian independence and the safeguarding of minorities in India. The prospect of India establishing friendly relations with Italy may have given pause to the ruling echelons in England. In reality, Gandhi's four-day trip to Italy involved a number of incongruous activities. He toured the Vatican museums but was denied an audience with the Pope. He met with Maria Montessori and visited two of her experimental schools. He had an appointment with Tolstoy's granddaughter. He also had an interview with the new secretary of the Fascist Party of Italy, Achille Starace. And last, he was received by Mussolini for twenty minutes in the duce's office.[107]

Although Gandhi's historical reputation was not irreparably damaged by the visit to Italy, it had immediately disastrous repercussions for the triple causes of world peace, anti-imperialism, and resistance to social injustice. Romain Rolland accurately predicted that the fascist press would misrepresent or suppress the content of Gandhi's public statements. The newspaper Giornale d'Italia quoted Gandhi as sympathetic to fascist opinions, alleging that he sanctioned the use of violence. Fascist press reports of his speeches simply deleted the "non" from the word "nonviolence." With the peaceful and loving components of his statements removed, Gandhi's critique of the British Empire seemed more menacing than he intended. The trip to fascist Italy tarnished his prestige among pacifists and leftists in France and Great Britain. Far more insidious was the effect of Gandhi's presence on thousands of oppressed antifascist Italians, both in and out of Italy: "Anything of this nature in Italy would be harmful to the Italians. People would say: 'The great saint is with the oppressors against the oppressed.' "The antifascist emigrés clustered around La Libertà in Paris reported that Gandhi's trip to Italy was marked by "ingenuousness."[108] Gandhi's misinformation about the degrading policies of the Italian government angered his French biographer. He began to reappraise the incisiveness and efficacy of Gandhism in the face of international fascism.

Unable to convince Gandhi that the "true face of Fascism" was

murder and repression, Romain Rolland predicted that nothing worthwhile would result from Gandhi's trip. "I should have said to him: Well, then, you will not go. At no price ought you to shake hands with the assassin of Matteotti and Amendola."[109]

Gandhi, in fact, had been favorably if somewhat ambivalently impressed by Mussolini. Europeans should suspend judgment on Mussolini's "reforms," he thought, until an "impartial study" could be carried out. Although Italy was repressive, its coerciveness paralleled other European societies that were also "based on violence." There was merit, Gandhi held, in Mussolini's programs against poverty, his opposition to "superurbanization," and his corporate efforts to harmonize the interests of capital and labor. Moreover, behind Mussolini's implacable facade and his oratorical flourishes, Gandhi detected an "inflamed sincerity and love for his people," as well as a disinterested desire to serve his country. The Italian people were inspired by the duce—this accounted for Mussolini's vast popularity.[110] Gandhi subsequently told several Indians leaving for a European trip that there were two Europeans worth knowing: Mussolini and Romain Rolland—a distinction his antifascist French biographer ironically recorded but hardly appreciated.[111]

Romain Rolland was incensed by Gandhi's impressions of fascist Italy; they were "hasty," "erroneous," and "careless." He challenged Gandhi's capacity to assess the popularity of the fascist regime, given his short stay; his ignorance of the Italian language, history, and culture; and his failure to meet opponents of the government. Gandhi was astute at reading progressive British opinion and politics, but he seemed oblivious to the dynamics of fascism and to the abuses of organized state violence. The hidden Italy was a wounded country, best represented by the enemies and victims of fascism, that is, by those men and women silenced by lies, mystified by "bread and circuses," and brutalized by police terror. Gandhi knew nothing of deported Italians doing forced labor on volcanic islands off the coast of southern Italy. He had no idea of Matteotti's widow, hounded by the fascist secret police. Gandhi's insensitivity to the "moral sufferings" of the majority of the Italian people was shocking. Romain Rolland refuted Gandhi's rationalizations for Mussolini's policies by differentiating between Western countries. To say that all Western democracies were coercive was sophistic and ahistorical.[112]

Gandhi misunderstood that fascist violence had a bureaucratic apparatus and ideological legitimacy not to be found in the Western democracies. The various "crimes" of the duce's regime included state-ordered executions. Mussolini suppressed civil liberties. He systematically destroyed the Italian Labor Confederation, popular libraries, and the socialist municipal councils. He decimated the Italian Socialist Party, an act of vindictive revenge, for Mussolini had served as the second-ranking official of that party. He brutalized the Italian peasantry, exacerbating the divisions between north and south. Gandhi was mistaken to see Mussolini as a protector of the Italian people; he should not have swallowed the duce's self-aggrandizing rhetoric at face value. There was no self-abnegation, no ascetic ideal, among the Italian Fascist Party leadership. Rather, they were arrivistes committed to amassing personal wealth, imposters who craved domination. Mussolini's regime consisted of a "band" that "pillaged the State treasury and gorged [themselves] with millions." Romain Rolland pointed out that the symbiotic connection between fascist leadership and big business was explicitly expansionist and imperialistic. It would eventually push Italy into wars and into efforts to suppress underdeveloped countries.[113] A responsible political personality was obliged to support the antifascist cause.

Romain Rolland's preoccupation with Gandhi became the point of departure for another line of inquiry—Hindu mysticism. His biography of Gandhi was subtitled "The Man Who Became One with the Being of the Universe." By the late 1920s, he entered a period of scholarly researches on intuition, musical genius, and the nature of oceanic religiosity. The products of Romain Rolland's "journey within" were his autobiographical Le Voyage intérieur: Le Périple (1946); his multivolume biography of Beethoven, Beethoven: Les Grandes Epoques créatrices de l'Héroïque à l'Appassionata (1928) and Goethe et Beethoven (1930); and his three-volume study of Indian spirituality, Essay on Mysticism and Action in Living India: The Life of Ramakrishna (1929) and The Life of Vivekananda and the Universal Gospel (two volumes, 1930).[114]

Romain Rolland's immersion in mysticism plunged him once more into the oceanic current underlying his artistic sensibility. His period of intellectual disengagement culminated with the biographies of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda. There could be no greater

flight from social and political reality than these introspective autobiographical works, nothing more meditative than these volumes on Hindu mysticism. But even these works were designed to overcome the contemporary European ignorance of Eastern religious thought by paralleling common experiences of the divine. He combated the unbridled rationalism and scientism to which the twentieth-century mind was heir, claiming "the sovereign right of the religious spirit—in the true sense—even and especially outside of religious institutions, in every profound and impassioned movement of the mind."[115] While working on Hindu mysticism, Romain Rolland engaged Sigmund Freud in a controversy over the origins and meaning of the oceanic sensation.[116]

For Romain Rolland, the connections between Indian mysticism and the music of Bach and Beethoven, German idealism, the principles of the French Revolution, and the metaphysics of Spinoza irrefutably demonstrated the unity of human nature. The oceanic sensation allowed him to think himself into the minds of people and cultures different from his own. The oceanic feeling was the imaginative source and the deep structure of access to others and the world. It allowed him to grasp intuitively the larger connections the individual experienced in relationship to culture.[117]

After returning to India, Gandhi was arrested, led an unsuccessful campaign against Untouchability, and conducted fasts and marches. Romain Rolland kept the French reading public informed of these events by writing a total of nine reports, a serialized "Letter from India," published in Europe .[118] The British repression of the noncooperation movement made Gandhi seem to him a revolutionary martyr, a partisan of labor against capital.[119] He argued that a social revolution was imperative in Europe, and he predicted that such a revolution would follow either the Leninist or the Gandhian model. He held that violence and nonviolence, communism and Gandhism, were not necessarily incompatible—at least among sincere practitioners and in terms of the desired goal. He saw himself as the mediator between the pro-Soviet and pro-Indian camps in the period 1931 to 1934:

In the eyes of thousands of men who at the present moment consider it intolerable to maintain the present capitalist and imperialist society and who have resolved to change it, the great and ambitious Indian experiment with Satyagraha is the only chance open to the

world of achieving this transformation of humanity without having recourse to violence. If it fails, there will be no other outlet for human history than violence. It's either Gandhi or Lenin! In any case, social justice must be achieved .[120]

In April 1934, Romain Rolland definitively broke with nonviolent noncooperation as a tactic for revolution or resistance in contemporary Europe. The reason for the change was the historical ascendancy of fascism. Satyagraha having no realistic chance for victory in a Europe saturated by fascist movements, he switched his loyalties to the struggles of organized labor. Workers, at least, would actively resist fascism and right-wing extremism.[121]

By 1935, Romain Rolland revised his views on Gandhi's leadership of the Indian movement. For social reconstruction in India, the French writer preferred the younger leaders Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, who were more coherently socialist and who belonged to the left wing of the Indian Congress Party. Gandhi's sentimental and religious approach to politics no longer corresponded to realities in his own country. Nonviolence was not the "central pivot of all social action." He was particularly upset by the Mahatma's refusal to adapt the principles of socialism for his country. Gandhi's prejudices, his obstinate clinging to received ideas, meant that he was ill equipped to lead India, once it gained its independence, into the modern world.[122] Although he no longer advocated Gandhi's political philosophy and tactics, Romain Rolland always retained enormous respect for Gandhi the man; there was no personal rupture in relations, just distance. Nor did he waver in his judgment of Gandhi's prominence in modern Indian history. His last public statement on Gandhi condensed the ambivalence of his admiration for the man and his refusal to cling to nonviolence "in the face of the growing ferocity of the new regimes of totalitarian dictatorships. . . . We cannot, in this circumstance, advocate and practice Gandhi's doctrine, however much we respect it."[123]

To assess Romain Rolland's engagement as a Gandhian, we should note that his essays accomplished their immediate goals: they disseminated information about Gandhi's struggle in India and they familiarized the European public with the concepts of nonviolence and noncooperation.

From 1923 to 1932, he had harnessed his international prestige

and his gifts as a writer to serve as the European popularizer of Gandhi. His articles, introductions, anthology of Gandhi's thought, and above all his biography transmitted the Mahatma's message in Europe. Romain Rolland presented nonviolent resistance as a concrete third way between Leninism and Wilsonism. By 1923, he was convinced that the revolutionary conjunctures of postwar Europe had passed, that the European reaction had consolidated its gains. He presented Gandhism as a potentially powerful political philosophy, a vision of politics and morality, that allowed both for individual refusal and for collective disobedience. In the European setting, it might provide postwar pacifists a viable model for the organization and structure of a movement, a paradigm for leadership and action. By the late 1920s he considered Gandhism a revolutionary movement of the spirit or soul. By the early 1930s he linked it to the revolutionary strategy and tactics of syndicalism. Civil disobedience and radical trade unionism could work together.

His World War I experience, coupled with his reaction to events in the immediate postwar period, made Romain Rolland psychologically and ideologically receptive to Gandhi's ideas. Motivated by his intellectual curiosity about India, he seized on Gandhism in part to extricate himself from his political bind: isolation, a posture of criticism without the proposal of a constructive program, and, above all, reliance on vague, metaphysical formulas in place of concrete notions of strategy and tactics. He assumed the task of expanding the consciousness of the European intellectual community by introducing Gandhism as a new area of study, a collateral branch of Indian spiritual thought, without compromising his intellectual integrity, and without having to join an established political party. Accepting the precept that no form of knowledge was foreign to the mind, he initiated a process of European acquaintance with Indian culture, personalities, and political conflicts and strategies. His campaign confronted European and particularly French xenophobia. Romain Rolland must be seen as a great challenger of French ethnocentrism.

If Romain Rolland's essays prepared the European public for Gandhi's message and methods, they failed to ask how Gandhism would ground itself in the materialist West. In his enthusiastic effort to demythologize standard East-West stereotypes and to stress unity, he blurred distinctions. He made a leap of faith to

Gandhism, but he did not consider the sources of Gandhian resistance in Europe or the training ground for its leadership.

Gandhi's methods might indicate to European pacifist intellectuals a way out of their impasse. He was painfully aware that members of the French and European peace movements had capitulated to the war in 1914 and after. Pacifists had been weak, contradictory, and unable to transform their theories into antiwar practice in the face of the grave crisis of World War I. Gandhism might provide European pacifists, especially religious ones, with principles requiring self-sacrifice, imprisonment, and even death. Nonacceptance of the state might allow European war resisters to move from isolated acts of conscientious objection to a massive civil disobedience that might ultimately subvert the state. With the Indian model in mind, one could not separate issues of social injustice from the foreign policies of major European powers.

Despite the genuine affection between Romain Rolland and Gandhi, the two were working at cross-purposes, even at the most cordial stages of their relationship. Gandhi's main platform was India: his movement would prove its viability there within the context of the independence struggle. The propagandistic edge of Romain Rolland's essays undoubtedly supplied the Gandhian struggle with an additional lever of prestige and authority. For his part, Romain Rolland seized on the universal aspects of the Mahatma's theory and practice. Though he sympathized with the Indian national liberation movement, he was committed to generating a French and European Gandhian movement—he wanted to internationalize the nonviolent cause. If Europeans did not accept Gandhi as a new spiritual and political guide, his ideas would at least stimulate dialogue among partisans of progressive social change.

Because he never considered systematic thinking a virtue, Romain Rolland was not perplexed by the internal contradictions within Gandhism itself. There was no critique, for instance, of Gandhi's policies when they were patently unreasonable, puristic, or even inconsistent with the dictates of conscience. Romain Rolland subsequently called into question Gandhi's support of the British Empire, as he did his voluntary participation in the Boer War and especially World War I. That the Mahatma had accepted—but transformed for his own purposes—the elementary Hindu allegiance to caste (with the exception of the barbaric tradition of Untouchability),

cow protection, idol worship, and other aspects of traditional Hindu doctrine demonstrated that his political philosophy was inextricably tied to ancient Indian customs. Romain Rolland did not realize that Gandhi's failure to reconsider his attachment to Hinduism would leave India hopelessly backward looking or that Indian religiosity would obstruct the movement's acceptance by Westerners. Moreover, Gandhi's capacity to tap India's spiritual heritage illustrated a tighter grasp of political expediency in India than the idealistic biographer wanted to grant.

Romain Rolland pursued his flight from time by meditating on eternity. Gandhism pushed him toward depoliticization: his trilogy on Indian mystics represented his most disengaged stance in the interwar period. He tended to overlook the limitations of the satyagraha doctrine, which was anti-industrial, nationalistic, and entangled in a mystifying metaphysical web. His failure to visit India prevented him from seeing the stark and overwhelming reality of India's poverty and the ignorance of its populace. Only in the mid-1930s did he sense that Gandhism would never provide India with a complete tool by which to liberate itself from this misery. He never saw noncooperation in practice, hence he never ascertained its finite limits. In his mind it remained a beautiful ideal, something to be striven for and perfected in the future.

Like so many students and advocates of Gandhi after him, Romain Rolland saw in Gandhism what he wanted to see.[124]

He made broad, unsubstantiated claims about nonviolence, especially given the very limited nature of its victory in South Africa and its precarious state in India from 1923 to 1932. By refusing to extract the secular content and political appeal of the nonviolent message, his writings might have unwittingly retarded a mass European acceptance of Gandhi's novel political weapon. He did not initially try to politicize either the doctrine or the audience. At first he had not carefully examined whether the movement was inherently reformist or revolutionary, whether it could be stretched to encompass socialist goals. More important, he blunted the differences between national independence struggles and those involving war resistance and class conflicts in more advanced societies. Although some of the propaganda for nonviolence contained unwarranted rhetorical violence, he never developed a psychological critique of absolute nonviolence that questioned whether nonvio-

lent resisters did emotional violence to themselves through their radical prohibition of the expression of anger.

In Romain Rolland's biography, the Mahatma is deified as a messiah for India and for the world. Gandhian noncooperation with the state became the gospel updated, alternatively described as a new Christianity and a religion of humanity. Gandhi answered his need not only for a splendid spiritual leader but also for a martyr. The British persecution of Gandhi and the violent repression of his movement suggested that he might die violently and soon. History bore out that dreadful premonition. Gandhi was assassinated in 1948, four years after Romain Rolland's death.

The Gandhian stage culminated Romain Rolland's evolution from antiwar dissenter to popularizer of nonviolent resistance. Gandhism was compatible with Romain Rolland's dialectical formula for intellectual commitment: "Pessimism of the intelligence, optimism of the will." Nonviolent resistance fused audacious action with critical analysis. There was no great gap between Gandhian nonviolent resisters and the violent social revolutionaries. He was most pro-Gandhi while disenchanted with the Russian Revolution, and he became most critical of Gandhi when he moved closer to the fellow-traveler position. For several years, he tried to be an international intermediary between the two camps.

If his introduction of Gandhism resolved a personal and spiritual problem for him, it simultaneously created major problems for pacifists throughout the twenties and thirties. Romain Rolland's Gandhism stressed character building, virtue, and integrity; it was oriented toward fortifying the individual's autonomy, healing inner existential splits. He wanted pacifists to be incorruptible and visionary, to stand above parties, classes, and coteries. They were not to dirty their hands. Rollandist pacifism was ambivalent toward the Communist International and toward the issue of social revolution. That ambivalence would plague pacifists during the period between the wars.

Gandhism did not provide a social, economic, or cultural analysis of the roots of war or a persuasive ideology for the masses. It was not readily absorbed in the postwar European atmosphere of speed, machines, automobiles, airplanes, jazz, and adventure. It did not appeal to the longing of youth for revolt or the yearnings of war veterans for camaraderie. Gandhism in Europe did not give

rise to a surrogate Gandhi. Romain Rolland was not enough of an activist or professional politician to step into that role.