Chapter Three—

The Definition of Diocesan Boundaries (1): to 1266

The thirteenth century was a world of dioceses. Clerks writing in the papal chancery had no serious maps but were not on this account discommoded. They wrote to a Christian world securely embraced and divided. Diocese met diocese everywhere. Nothing was excluded. Where was a place? It was at least locally, not always jurisdictionally, within a diocese. Curial letters and formularies make clear that this is what the clerks thought or assumed; and theirs was the assuming mind and idiom of formal Christendom.[1] Of course the real meaning and importance of diocesan boundaries, like any others, depended upon what they contained and what they divided; and these whats were, in the early thirteenth century, about to undergo significant, and really quite drastic, change.

In 1182 Pope Lucius III granted to Benedetto bishop of Rieti and his successors a confirmation of their rights and privileges, which included a description of the diocese's geographical boundaries, imagined as starting from and returning to the Tancia on the borders of the diocese of Sabina and passing through or near some still seemingly recognizable places, like Marmore, Stàffoli, Lago di Fucino, Collalto, Vallebuono, Canemorto (Orvinio), Pietrasecca, the torrente Farfa, and through other places less easily identifiable. The original privilege does not seem to have survived at Rieti, and, in fact, its wording suggests that it is copying the words of other earlier privileges which do not survive.

The copied, probably copying, privilege's description is, nevertheless, an affirmation of the idea of territoriality, a legacy, but also an idea

related to that distant one, for example, which was changing the kings of England from reges anglorum to reges anglie , an idea which was neither clear nor locally limited. But it was, in the limiting sense of the word, an idea, although one with a potential for development and physical extension. Had a contemporary been able to describe the boundaries of the relatively large and complex diocese of Rieti in terms that a modern cartographer could follow, it would have been surprising. It is not clear that the composers of the Lucius privilege thought that they were describing actual and exact boundaries. They did not need to be exact because they were describing a general area in which they then proceeded to name the enclosed plebes, pievi (the baptismal churches). The privilege names seventy-five pievi and then some sixty "oratoria quae monasteria dicuntur (places called monasteries)" and some twenty more "infra ciuitatem in suburbiis eiusdem ciuitatis (within the city in the suburbs of the city)"; but these names, although they removed the burden of exactness from the boundary description, should not be thought all necessarily to represent places existing in 1182, or existing as plebes or monasteria . The rather indistinct category with which the privilege concludes its list of plebes and monasteria is followed by a list of seven castra , a roccha , and a turris .[2]

The surviving Anastasius IV confirmation of privileges from 1153 contains a similar but not identical list of plebes and monasteria , and it concludes with nine castra .[3] Although both privileges are essentially lists of the internal units of the diocese in which the bishop and cathedral church had jurisdictional and other rights, neither was probably meant to be seriously descriptive even in this sense. The privileges need not suggest that the popes themselves or any of their, particularly curial, contemporaries examined those rights in any rigorous way in connection with these confirmations. The evidence surviving from the time of the long-episcopated Bishop Dodone, Anastasius's bishop, however, suggests that Dodone was, at least in his time's terms, an unusually active diocesan; and the evidence surviving from Bishop Benedetto reveals activity.[4]

In the mountainous wastes along parts of the border of the diocese of Rieti, exact geographical boundaries would have been useless. In the broad high wastes behind San Pastore, for example, unless there had been measurable and returnable tithes in cyclamen and fiori di pasqua (or more realistically, perhaps, in hay or wood or animal droppings), who need have cared about diocesan or pieve boundaries?[5] The geographical boundaries that did matter, one must assume, were defined

by local long custom. The diocese of Rieti shared boundaries with the dioceses of Sabina, Narni, Terni (after its reconstitution), Spoleto, Ascoli, Teramo, L'Aquila (and before it, Forcone), and the Marsi; it seems to have touched a corner of the diocese of Tivoli. Although there may have been some hostility between Rieti and Spoleto in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and perhaps some problem with Narni and Terni, the only clear and sharply visible dispute over diocesan boundaries was with the diocese and diocesan of L'Aquila.[6]

L'Aquila was in various ways a special case. The city itself was an early member of a series of creations of centralized agglomerations of castri and castelli in the northernmost parts of the Regno, the reformed kingdom of Naples—places like Leonessa (an earlier Hohenstaufen foundation), Cittareale, Cittaducale, Borgo Velino, and Posta—places which were meant to offer amenities to their inhabitants and to make defense, administration, taxation, and the control of trade more effective, places which recall similar creations in northern Italy, southwestern "France" and elsewhere, places which also made the mountainous Abruzzi a more conventional part of urban Italy.[7] In 1256 and 1257 the episcopal see of Forcone was transferred to, or renewed in, this "new city" of L'Aquila. Bishop Berardo de Padula, who may already have been residing in L'Aquila as bishop of Forcone, was made its first bishop.[8] The sense of continuity which this implies, however, is misleading. The new bishopric was more vigorous than the old, attached as it now was to a real city, in a relatively toughly governed kingdom, at a time of generally increased diocesan activity.

Pope Alexander IV's privilege of translation seems to have granted to the new bishop jurisdiction over all the inhabitants of Forcone and Amiterno and to have named, roughly, a geographical outline of the diocese.[9] The vigor of the new see seems quickly to have been applied to Amiterno and thus to have provoked a dispute with the church of Rieti. A mandate of Pope Clement IV addressed to the Cistercian abbot of San Pastore and dated 2 April 1266 was obtained for the bishop and chapter of Rieti, perhaps through the intervention of Cardinal Giordano of Terracina. The mandate says that the bishop of L'Aquila suis finibus et iuribus non contentus , not content with his borders and rights, was forcing the rectors and clerks of Amiterno (the ecclesiastical area on the eastern border of the diocese of Rieti and to the north and west of L'Aquila) in the diocese of Rieti to come to his synods and that he was in various ways keeping the bishop of Rieti from exercising his appropriate jurisdiction in his own diocese; piling injury on injury, the man-

date continues, the bishop of L'Aquila had ordered, within a term fixed at the bishop's own pleasure, that rectors and clerks of Reatine Amiterno, having destroyed their churches, should transfer themselves to L'Aquila, where new churches should be constructed and where they themselves should live—this on pain of excommunication and interdict. The pope's mandate says that he, who did not wish calmly to tolerate the bishop of L'Aquila's behavior, orders the abbot of San Pastore to warn the bishop to cease his injurious behavior toward the church of Rieti without delay. Should the bishop refuse, the abbot should cite him to appear before the pope with documents which would establish his rights and privileges, cum priuilegiis, iuribus et munimentis , within an appropriate term, and the abbot should notify the curia of his action. Another papal mandate, similarly dated, was addressed to the royal governor (capitaneo regni ), a mandate procured for the bishop and chapter of Rieti, again possibly through the intervention of Cardinal Giordano. The mandate states that certain inhabitants of the city of L'Aquila, putting aside fear of the Lord and concern for their own safety, had repeatedly inflicted grave injuries and damages on the persons and goods of rectors and clerks of churches in the diocese of Rieti; it orders the governor to use his authority to see that such acts cease.[10]

Certainly in the early 1230s major parts of the old diocese of Amiterno had been considered, without dispute, part of the diocese of Rieti. Equally certainly, in the early fourteenth century the compilers of the rationes decimarum (who admittedly need not have had much local knowledge and who perhaps need not always have been really forced to know in what diocese places actually were) put a number of these old Amiterno places in the diocese of L'Aquila, where—at least topographically, because of the connecting valley of the Aterno—they made better sense.[11] As late as 1282 the bishop of Rieti, Pietro da Ferentino, with the force he had as a papal collector behind him, was able to treat the churches of San Paolo and San Giuliano of Barete and San Pietro of Popleto (or Poppleto) as if their pievi and churches still lay within the diocese of Rieti, and to exact, or try to exact, an oath of loyalty from the wayward rector of Poppleto through his, the bishop's, representatives, the archpriests of the two Barete churches with the assistance of a canon of Santa Maria di Bagno.[12] The eastern boundary of the diocese of Rieti, close as it was to the troublesome boundary between the Regno, the kingdom of Naples, and the papal states, was unstable in the thirteenth century. It was changing and forming itself at the same time that the nature of diocesan government was changing and reforming itself.

Tension between Rieti and L'Aquila is unsurprising. Rather more surprising is the selection by Pope Clement V in 1311 of Bishop Giovanni Papazurri of Rieti, presumably for reasons of propinquity, to be a member of a commission appointed to investigate the alleged crimes of the then bishop of L'Aquila, Bartolomeo. The accusations against the bishop of L'Aquila were, in the style of the early fourteenth century, sufficiently rich to satisfy the taste of any possible enemy. The palest but perhaps most significant of the complaints was that the bishop, without the knowledge or permission of the Holy See, extracted procurations from his diocese but did not give them to the Holy See. It was also complained that the bishop showed no reverence for God and that when he celebrated Mass he did not take off his miter but irreverently kept his head covered even at the Consecration. It was said that his cupidity was so great that for a sum of money which he had received he allowed certain homicidal priests from Guasto (Vasto) and Rocca San Silvestro, identified as being within the diocese of Rieti, publicly to celebrate Mass.[13] Liveliest of the complaints, however, was that which accused him of taking a monthly pension from publicly acknowledged prostitutes in the city of L'Aquila. If Giovanni Papazurri did not have some part in the instigation of these complaints, at least if he felt any diocesan campanilismo, he must have found some pleasure in them.

Rieti's neighbor to the west was Sabina, an old diocese with a cardinal bishop and a remarkably clearly defined Rieti border, at least by the mid-fourteenth century, in spite of wasteland. In 1343 when the Registrum iurisdictionis episcopatus Sabinensis was composed, after the careful, inventorying visit of the cardinal bishop's vicar general, the structure of the diocese was as palpably realized and described, although without actual geographical boundaries, as any diocese could be expected to be.[14] The contrast between fourteenth-century Sabina and thirteenth-century L'Aquila is very sharp. An Amiterno sort of dispute between mid-fourteenth-century Sabina and Rieti is inconceivable. Geography and chronology together made it impossible.

On 3 February 1252 Pope Innocent IV provided a new bishop to the see of Rieti, a man from his own curia, a corrector of papal letters, Tommaso. Tommaso replaced the Franciscan Rainaldo da Arezzo with whom, Salimbene shows, Innocent had tried to give the diocese inspired spiritual leadership. Having failed with his friar saint, Innocent chose as his successor an experienced administrator. The sermons on the active life with which Innocent and his curia had regaled Rainaldo were replaced by helpful papal letters and administrative powers, with

which Tommaso could find the force to reconstitute the diocese in a mid-thirteenth-century pattern at an opportune moment, in 1250, after the death of the Emperor Frederick II, a ruler who both in the order and disorder he created had made ideal diocesan government, from an ecclesiastical point of view, impossible.

Tommaso's efforts to deal with the diocese are most immediately visible in the cathedral church's campanile, which extends in front of the church's facade into the piazza. Tommaso's responsibility for the new campanile is proclaimed on a stone placed within one of its sides. The campanile called the canons to their hours of liturgical prayer, and it thus echoes Rainaldo's struggle with his chapter; but it is also a sign of good and solid and planned order at the center of the diocese. The inscription includes the statement that Tommaso in his first year held a concilium , a synod, and visited the churches in his care. The new bishop's first year, the messages of and on the campanile suggest, was a year of new structure and of organization.[15]

That organization included the compilation of a new list which described the diocese: a summa omnium ecclesiarum tam ciuitatis quam dyocesis , a compendium (or an attempted compendium) of all the churches of the city and the diocese of Rieti and their customary payments to the Reatine church.[16] The summa begins: "Nos Thomas permissione diuina Reatinus episcopus uolentes scire iures et facultates ecclesie Reatine ad utilitatem nostram et subditorum curam facilius subportandam successorum nostrorum perpetuam memoriam omnes ecclesias que fuerunt et sunt in ordine congruo duximus adnotandas infra diocesem Reatinam"; and so the bishop wanting to know the rights of his church for future use and perpetual memory caused (or tried to cause) to be written down all the churches which were and had been in the diocese of Rieti. The list, as it is preserved in the Paris manuscript, begins with the churches of the city itself, written in sequence in lines extending across the folio; and then moving out of the city and to Labro first and Piediluco second, in the most northwesterly part of the diocese (if and when Piediluco was in the diocese at all), it proceeds, from its second folio with some regard for geography, folio by folio in two columns divided into groups of churches, each group signaled by a paragraph notation and each group beginning with the name of an important, presumably mother, church or the name of an order, monastery, or hospital with its members, chapels, or attached churches beneath it. There are 163 of these groups. The localities fully extend into the area of Amiterno.

Tommaso's list does not follow the pattern of the earlier papal privileges; it is not based upon them. It is in some ways simpler than they are: it does not talk, beyond customary income, about rights and jurisdiction, except to notice problems of exemption. It does not talk, as does the Lucius III privilege, about "plebes omnes cum cappellis," not about plebes or parochie at all, but about ecclesie ; but it talks, as they do not, about religious orders, including new orders, and about churches attached to external bodies, like San Pietro, San Paolo, and San Giovanni Laterano in Rome and like Ferentillo and Farfa.[17] It is not a revolutionary document, but it is a newly imagined, a fresh one.

Tommaso's list can be seen as a scheda , as program notes for reorganizing the diocese, recollecting its parts. And that, surviving documents from Tommaso's episcopate suggest, was, with papal support, his program. Tommaso's personality is not revealed to us; but there is every suggestion that he was, as the papal document providing him to the see perhaps formulaically reveals, an upright person of good reputation, a man to be trusted, not only an orderly man.[18] He was a man chosen as arbiter. A dispute over properties in the area of Rieti between the church of Rieti and Pietro Bosi and then his heirs (particularly represented by Boso di Pietro Bosi, for example, from the years 1256 to 1260) was brought to court before a papal delegate, the pievano of Cascia in Spoleto diocese, and, by common consent, was moved to arbitration with Tommaso as arbiter.[19] In another example from 1254 Tommaso, who had been chosen as arbiter by the representatives of the cathedral chapter and of the Cistercian monastery of San Pastore, settled a dispute between those bodies about two pieces of land, one in Terria and the other in Greccio.[20] Tommaso continued to work not only with bringing its property back to the chapter but also with bringing order to the chapter itself.[21]

The diocese of Rieti to which Tommaso came, and in which and with which he began to work, was not an undefined geographical space, but rather an ill and unevenly defined one. Tommaso himself, or someone working for him, created in 1254 the sharpest and most revealing drawing, verbal drawing, or diagram of how that space could be seen from within the diocese in Tommaso's time by someone with his energy and imagination, and his evident desire to understand and control that space. Tommaso produced a pragmatic map in words.[22]

The map comes from a dispute between the bishop and his church, on one side, and, on the other, the old Benedictine monastery of San Salvatore Maggiore, the heavy ruins of which remain, about fifteen kilo-

meters southeast of the city of Rieti in the uplands between the valleys of the Turano and the Salto. This case, together with others earlier than itself, like those between the church of Rieti and neighboring Cistercians over drying marshlands and between the church of Rieti and the abbey of San Pietro, Ferentillo, over San Leopardo in Borgocollefegato, is able to expose the early thirteenth-century diocese, its contents and so in a different sense its boundaries, and particularly contested boundaries, at a, at least in some ways, more convincing level of reality than do privileges and lists.[23] These cases can, that is, expose this reality to a reader who is able to muster the patience to watch with reasonable attention the composition and movement of their courts, the structure and angle of the questions put to their witnesses, and the attitudes caught in those answers—and even more than attitudes the flickering quick images, half-repetitive, half-changing, of which the answers are composed.

The San Salvatore case, the case with the map, was the result of, and part of, Tommaso's program of collecting again for the church of Rieti the rights and possessions which he thought it had lost or failed to exercise during the first half of the thirteenth century. The bishop's positions, which were meant to support the reestablishment of the rights that he claimed the church of Rieti should exercise over the monastery of San Salvatore and over its subject churches within the diocese, were presented in March and April 1254 before two canons of Rieti collegiate churches, Filippo canon of San Ruffo and Bartolomeo canon of San Giovanni Evangelista. These two auditors had been delegated by Pietro Capocci, cardinal deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro, himself the papal auditor in the case.

One aspect of the bishop's case was geographical and concerned boundaries. The bishop wanted to establish the fact that the subject church of Santa Cecilia was within the city of Rieti and that the abbey and its other subject churches were physically within the diocese of Rieti: sunt site in diocesi and consistunt intra fines diocesis . He thus had to deal with the diocese's extent. He did this by proposing a series of lines extending from the city of Rieti. He proposed that the diocese of Rieti extended from Rieti to Collalto, from Rieti to Monteleone, from Rieti to Antuni and beyond, from Rieti to Castelvecchio di Toro (Castel di Tora) and beyond, from Rieti to Rocca Sinibalda and beyond, from Rieti to Santa Maria del Monte and beyond, from Rieti to Poggio Perugino and beyond, from Rieti to Greccio and beyond, from Rieti to Labro and beyond, from Rieti to Sala (Santa Maria, which is now in the

diocese of Spoleto), from Rieti to Capitignano ("Capinniano de Nouer'"), from Rieti to Sant'Angelo in Vigio (later in the diocese of L'Aquila), from Rieti to San Vittorino (later in the diocese of L'Aquila) and beyond, from Rieti to Cartore in the Marsi and beyond, from Rieti to Roccaberardi ("Roccam Vellardi") and beyond, from Rieti to Mareri and beyond, from Rieti to Petrella and beyond, from Rieti to Pendenza and beyond, and from Rieti to Valviano and beyond.[24]

The bishop of Rieti described (and the abbot of San Salvatore denied) his diocesan map in which Rieti was the hub from which spokes extended (or arrows pointed) to or through diocesan (or so claimed) towns and churches. In the map which the bishop projected to catch these churches, the spokes of his wheel or the directed arrows which he drew from Rieti into the diocese sometimes overlap (for example, those to Antuni and Castel di Tora); sometimes they seem out of order (for example, that to Monteleone). Rocca Sinibalda, except for its topographical obviousness and closeness to San Salvatore, seems an odd place to choose in establishing boundaries. The device itself, compared with that of the privileges and list, can seem primitive, only in the process of being worked out—but that of course is its strength, what makes it compelling. Tommaso's description seems particularly effective if it is thought of as being formed in the bishop's mind, and his advisers' minds, as they sat in Rieti at the top of the hill on which the Duomo is built and which dominates the conca , the basin, of Rieti, and from there looked out in all directions toward the farthest limits of the diocese.

To his radiating spokes the bishop added another, netting, element to catch the abbey and its subject churches. Similarly, he said, making a smaller, but not close, pattern of cross-weaving within the established lines, the monastery est situm , is sited, and the churches site sunt infra , are sited within the city of Rieti, Rocca Sinibalda, Castel di Tora, Posta, Paganica, Licetto (Ricetto), Roccaberardi, Mareri, Petrella, Pendenza, and Valviano. The priest of one of the subject churches made specific objection to some of the direction points and tried to bring the northeastern boundary closer to Rieti, and to dispute part of the southern boundary.

One of the bishop's positions connects his interest in geography with his curial background. He, former corrector of papal letters, said, and the abbot of San Salvatore agreed, that popes wrote to the abbot and convent as the abbot and convent of San Salvatore Reatino or of Rieti and that under that name the abbot and convent impetrated letters from the Holy See. The bishop further asserted that the abbey was called

Reatino or of Rieti in common speech. Tommaso, the former corrector, could not possibly have thought that this terminology proved the subjection of the monastery to the local bishop. He could, however, seal with the acceptance of this terminology his argument that the abbey was locally within a place which was called Reatine; and he could try to tie the abbey more firmly to the place with his arguments that San Salvatore and its vassals went to arms at the command of the podestà and council of Rieti, formed part of the hostem and parliamentum of Rieti, and shared responsibility for city walls. With this as background Tommaso could try to prove that the bishop's episcopal authority should be recognized in San Salvatore's part of this Reatine space.

As well as being a geographer, Tommaso, or his adviser, was a historian; and in that art he was more conventional and sufficiently successful so that his case-supporting history of the early thirteenth-century bishops of Rieti is the most accurate, I think, that exists. Tommaso dealt directly with general history in attempting to establish San Salvatore's involvement with the imperial Hohenstaufen, antipapal cause, but his most exacting and extended job was local diocesan history. To prove his case the bishop had to establish the rather tricky claim that in spite of many events, particularly wars, which had impeded the performance by his predecessors of their rights and duties, enough had been performed clearly to show that bishops of Rieti had exercised their rights over San Salvatore and its subject churches. The bishop claimed that his predecessors had visited the churches and received procurations and cathedratica , that they had celebrated divine services and preached in one of the churches (Santa Cecilia in Rieti) and received a census from it, that they had heard marriage cases in the abbey's territory and ordained abbey clerks. The bishop claimed that his predecessors had consecrated churches, chalices, altars, and ornaments for the churches.

Thus, just before the creation of the diocese of L'Aquila, which would remove physical territory from the diocese of Rieti, Bishop Tommaso tried to change and stiffen the actual consistency of diocese at Rieti. In doing it he tried to observe, control, manipulate, and finally change the course of history. The course of history to which he looked back included the episcopate of Bishop Rainaldo de Labro (active at least from May 1215 to July 1233 and almost surely in February 1234). Tommaso summed up Rainaldo's episcopal activity in this way: "Rainaldo de Labro was unable fully to exercise episcopal jurisdiction for ten years and more because of the malice of the times and because of wars "—and about wars he specifies those involving the Emperor Fred-

erick and also those of Count Rinaldo and his brother Bertuldo, who were the sons of old Count Corrado who had been duke of Spoleto—undoubtedly true, in its way, but interested, history.[25] Rainaldo can, at least, be seen acting very much as Tommaso would act in his disputes with two resisting ecclesiastical complexes within the diocese. The documents remaining from the ensuing cases at law expose a notion of diocese consonant with that exposed in the earlier San Leopardo and the later San Salvatore cases, but each of Rainaldo's cases offers its own kind of resonance to the definition of diocesan boundary and of diocese.

Twenty-five documents and fragments of documents, copies and drafts which were written between 1220 and 1234, are preserved from a dispute between Bishop Rainaldo and the clerks of the collegiate church of San Silvestro "de Petrabattuta."[26] The actions of the case bounce around the periphery of the diocese. They, in connection with the provenance of some of the judges who are involved, allow one to see the diocese of Rieti in an enlarged neighborhood. In following these actions and observing these judges one must make one's mind a map. One must see a map. That map will not have exactly the same principles and contours as would the participants' maps; but quite clearly they were thinking in their maps' terms.

Although the documents from the San Silvestro case are variously articulate, they leave their reader in ignorance, as do the documents preserved from many similar cases, about a number of crucial elements in the case itself. One cannot know exactly when the San Silvestro case began or when and how it ended, if in fact it had a distinct ending. One can be fairly sure of what sort of institution San Silvestro was in the early thirteenth century; it was a collegiate church of secular clergy which maintained for itself some of the terminology of an abbey. One cannot, it seems, be sure where San Silvestro was; its name, "de Petrabattuta," is spelled in fourteen different but closely related ways in the surviving documents.[27] There is more certainty about the location of its four subject churches which are mentioned in the documents: San Pietro de Cornu; San Tommaso de Viliano; Sant'Ippolito de Ciculis; San Nicola de Rivotorto.[28] Corno, and actually Rocca di Corno, where San Pietro was, and Vigliano are relatively close neighbors on the Via Sabina between Antrodoco and L'Aquila. Sant'Ippolito in the Cicolano, on the right bank of the river Salto just as it now swells into the artificial Lago di Salto, is some twenty-two kilometers south and slightly west of both Corno and Vigliano. San Nicola de Rivortorto, which still existed in 1907, took its name from the river which empties into the Salto

about four kilometers upstream from Sant'Ippolito after flowing south through the Catena di Monte Velino from near the borders of Tornimparte, south and a little east of Vigliano.[29]

All four of the subject churches, and slightly less frequently San Silvestro itself, are repeatedly said by documents from the Rieti side of the case to have been physically within the diocese of Rieti. No surviving document from the San Silvestro side of the case denies this local description, although Corno and Vigliano were later within the diocese of L'Aquila, and although such a denial, if legitimate, would have been decisively helpful to San Silvestro. Pretty clearly all the churches were in or near the rough country which would become the boundary between the dioceses of Rieti and L'Aquila.

The matter in dispute in the San Silvestro case is stated, in slightly different terms, in several of the surviving documents. In dispute were the bishop's episcopal rights over the four subject churches and, perhaps even from the beginning, over San Silvestro itself; most specifically it concerned the collection of papal procurations, but also, at least by 1234, the Rieti side sought from the abbot and chapter of San Silvestro a fourth of the tithes, oblations, and mortuaries in the church of San Silvestro, de iure communi , especially (maxime ) because the bishop was, it was claimed, in possession, uel quasi , of all other episcopal rights in the church.[30]

The opposing clerics of San Silvestro not only claimed that the demanded procurations were uncustomary but also claimed in 1231 that the bishop was seeking a further procuration for the episcopal see. They sought to have restored to them their subject churches, the named four, which they said had been despoiled by the bishop.[31]

All the dated documents in the case, except one (and a quoted papal mandate), come from the years between 1231 and 1234. The exception is from 12 May 1220. On that day at San Martino di Pile, Bishop Teodino of Forcone sat as a delegate of the cardinal deacon of Santi Sergio e Bacco (Ottaviano Conti, called Dominus Ottavianus Cardinalis Sancti Sergii ) and listened to the bishop of Rieti and the abbot of San Silvestro.[32] The bishop was prepared to present his case, but the abbot said that he could not plead without his advocate or his clerks, "who were the cause of this dispute," and he added that he himself "had never wanted the dispute because hitherto there had been a composition with the church of Rieti concerning procurations and other things and that in the time of Pope Innocent and Bishop Adenolfo there had never been any discord between them." The bishop of Rieti asked that this

confession be committed to the judge's memory; and he said that he had accumulated considerable expenses in coming to the place of judgment. The bishop of Forcone consulted his "assessors" and set a future term at which time the abbot could plead and give just compensation to the bishop for his expenses.

On 1 September 1231 at Bazzano, which is just east of L'Aquila and again in the Abruzzi, the dispute between Bishop Rainaldo and the clerks of San Silvestro once more comes into view. In Bazzano the papal delegate Berardo , abbot of the Benedictine monastery of Santa Maria Bominaco, was active, acting under the authority of a mandate from Pope Gregory IX, which was dated from Perugia on 2 July 1228.[33] The abbot of Bominaco caused his own action and sentence to be recorded, ad maiorem cautelam et futuram memoriam , by his notary Gualtiero , and ad maiorem cautelam , the abbot affixed to the instrument his own seal. In this instrument the abbot had the notary record the abbot's version of the events of the case after his receipt of the papal mandate. The abbot had summoned both parties in the dispute to Paganica, which is about two kilometers north and slightly east of Bazzano. Although San Silvestro had appeared through its proctor, the priest Alberto, the bishop of Rieti had not appeared at all. Wishing, he said, to deal gently with the contumacious bishop, the abbot had again summoned him, to Bazzano. Again Alberto appeared, but no one from Rieti did. Alberto immediately asked that the abbot inhibit the bishop and also the chapter of Rieti from further molesting San Silvestro in the matter of the unwonted papal procurations and the other procuration for the episcopal see, and that he order the restitution to San Silvestro of the four subject churches, and that he grant San Silvestro legitimate expenses.

The abbot consulted his "assessors," of whom one was domno Petro fratre nostro and also allis prudentibus uiris nobiscum residentibus ; they wanted to reassure themselves about the bishop's actual receipt of the abbot's citations. Alberto established, through the testimony of named witnesses, that the bishop had received both letters apud Sanctam Mariam de Reat' . Then the abbot, again after, he says, careful deliberation with his assessors and "aliis presentibus quorum consilio habito nobiscum residentibus in ecclesia Sancte Juste de Baczano (the others present and residing with us at the church of Santa Giusta di Bazzano whose counsel we had)," judged the bishop contumacious and granted possession of the things sought to San Silvestro. The witnesses to this act included Gualtiero di Gualtiero Oderici canonicus Sancte Juste et nota-

rius publicus, assessor et testis (that is, the document's own notary), Theodino di Gualtiero canon of San Massimo assessor et testis , and Miles (or, more probably, the knight) Odericus frater eius , a cluster of brothers around the abbot. The abbot was then in residence, with his circle, at a place some forty kilometers northwest of his own abbey in the diocese of Valva Sulmona (the diocese southeast of Forcone), at Santa Giusta Bazzano, which was in that decade engaged on an ambitious campaign of reconstruction from which came its imposing church and remarkable painting. One of the canons of Santa Giusta acted as the abbot's notary, and as one of his assessors and witnesses.

On Saturday 18 September 1232, Luca, archpriest of Vigliano, acting as proctor of the bishop of Rieti (and very possibly in the interest of himself and the rights of his own church) appeared before the abbot of Bominaco in Sinizzo, a place near San Demetrio ne' Vestini, east of the Ocre villages, Fossa, and Sant'Eusanio Forconese, and about halfway between Bazzano and the abbot's own abbey; Sinizzo itself according to the fourteenth-century rationes decimarum , was just within the boundaries of the diocese of Valva-Sulmona. The archpriest of Vigliano asked the abbot to revoke the sentence of contumacy against the bishop of Rieti because the bishop had not, he said, been cited to appear before the abbot. Since the abbot would not revoke it, the archpriest formally appealed the sentence to the pope. This action occurred before a group of named witnesses including dompno Passavanti canon of San Pietro di Sinizzo and the local judex Pietro da Sinizzo who redacted the instrument recording the appeal.[34]

On 1 January 1233 Bishop Rainaldo made Jacobus Sarraceno, canon of Rieti, his proctor to act before the abbot in the San Silvestro affair; and two days later the canon-proctor can be seen and heard acting. On 3 January 1233 the canon, representing the bishop and wishing, he said, to obey the abbot's mandate, arrived at Bominaco. But the abbot had, within the term fixed for the case according to the bishop's proctor, withdrawn himself to the imperial court, and had, as was apparent from his sealed letters, left as his proctor and representative (uicem suam . . . procurauit ), his companion the monk Bartolomeo. Before this monk representative of the abbot, the proctor canon, who had brought with him as fideiussores the archpriests of San Vittorino and Santa Maria de Civitàte (Cività di Bagno), uiros diuites, nobiles et discretos (rich, respectable, and responsible) offered cautionem sufficientem exibere . The monk utterly rejected cautionem and fideiussores , any surety at all. But, although he said he could not go beyond the abbot's mandate to him,

he sought six uncie of gold as pledge for expenses and judgment. The proctor refused the pledge and appealed to the apostolic see. Witnesses to the appeal were Passavanti the canon of San Pietro Sinizzo, the priest Teodino and dompno Egidio clerics of San Salvatore Sinizzo, a man called Matteo Dodonis, and the two archpriests of San Vittorino and Cività di Bagno.[35]

The next day, the proctor canon Jacobus Sarraceno went to the palazzo of San Silvestro Petrabattuta (here called Petravactita) itself. There he delivered to Alberto, a canon of San Silvestro, letters from Pietro, the prior of Santa Maria Terni, which informed the clerks of San Silvestro (prudentibus uiris clericis de Petrauactita , or in copy Pretauactita ) that the case had been committed to him, the prior, by the pope, and that they should appear before him, or their proctor should, within thirty days of their receipt of his letters. At this point the Rieti canon proctor who had followed the case deeper and deeper into the Abruzzi, and followed the abbot of Bominaco to Bominaco only to find that he had removed himself to the court of the Abruzzi's Hohenstaufen king-emperor, transferred the case across the diocese of Rieti to the northwest, to the refounded Umbrian see of Terni, and into the hands of a man himself involved in that refoundation.[36]

On 2 January 1233, acting before the church of San Tommaso di Cività di Bagno (south of Bazzano and just north of the Ocre villages), four clerks of San Silvestro (here called "de Petra Bacteta" [?] and "Petrabat"), including the priest Alberto and two men called "Rain'l" and "Rainal'," cum uniuerso capitulo eiusdem ecclesie (the whole chapter of the church) had made the priest Paolo their proctor in the case, and they had the procuration written for them by Guitto (?) de Saxa, imperialis aule scriniarius .[37] On 7 February Egidio the scutifer of the bishop of Ricti was at Petrabattuta ("Petravaccita") acting as a nuncio for the prior of Terni; he assigned to the priests Alberto and Paolo, the proctor, sealed letters citing them to appear before the prior at Terni on 17 February. The prior informed the San Silvestro clerks that a day after their proctor had left his court the proctor of the bishop of Rieti had come saying that the term had not yet elapsed and saying that all that the San Silvestro proctor had proposed before the prior was false. On 16 February Bishop Rainaldo made dompno Giovanni Arlocco, clerk of San Giovenale Ricti, his proctor in the case. On 18 February the priest Paolo, as proctor of San Silvestro, appeared in the palazzo of the prior at Terni and appealed from the prior to the pope. The prior tried to mollify him:

Frater [he said to the proctor], non est necesse te appellare cum nec te nec conuentum nec ecclesiam Sancti Siluestri de Petra Vactuta in aliquo grauerim uel grauare uelim. Sed ducas coram me aliquem sapientem et quicquid peterit ostendere tam de loco securo dando quam de longinquitate loci quam de alia suspicione et de litteris que fuerint per mendacium impetrate et omnibus aliis obiectionibus et exceptionibus que mihi rationabiliter ostense fuerint tibi de iure facere sum paratus.

In four preserved copies the words of the prior of Terni's statement vary slightly: a mood changes; Frater becomes Amice ; a tecum is inserted; or an illud libenter audiam , which presumably had been omitted, is replaced. But essentially the copies agree: the prior tried to seem friendly and open to the San Silvestrini and their proposed objections; he said that he did not want to do harm to them or their church; he would gladly listen if they brought before him an expert who could substantiate their grievances about time or distance and mendaciously procured letters; it was not necessary for them to appeal because he was prepared to listen fairly. The copies also agree that the San Silvestro proctor was unsatisfied and went away.

On 21 February the prior of Terni sat again, this time in the palazzo of Guidone Machabei in Terni, before witnesses: Palmerio canon of the major church of Terni and Tommaso canon of San Lorenzo Terni, as well as Guidone Machabei himself, Nicola Elpizi and Merlino, citizens of Rieti. Prior Pietro found the appeal of the clerks of San Silvestro invalid. He declared the proceedings before the abbot of Bominaco null and void, and he granted possession of rights in the churches, and expenses, to the bishop of Rieti. He made the archpriest of Sant'Antimo di Valviano, within the diocese of Rieti, his nuntius and executor in the case.[38]

From Terni the case went to Rome and the Lateran. The auditor given in the case was the repeatedly active papal chaplain and subdeacon, Giovanni Spata.[39] Before him the priest Paolo presented a brief narrative from a San Silvestro point of view, of the progress of the case before the abbot of Bominaco and the prior of Terni. San Silvestro's proctor, he said, had appeared properly before the prior and asked for a copy of the papal letters giving the prior jurisdiction in the case, and the prior had refused to exhibit the letters. The proctor had asked for, and been refused, a place for hearing the case which would be safe for the San Silvestro side. The proctor further said that the court in Terni was beyond the statutory two-day limit of distance from San Silvestro.

On those bases he appealed, asked that the actions of the prior be declared invalid, and those of the abbot confirmed.

The Rieti side, which had had at least two of the documents from the Terni phase of the case copied by a Reatine scriniarius on 2 November (before the archpriest Salvo, of the collegiate church of San Giovanni Rieti and one of its canons, Eleutherio), was prepared to answer the San Silvestro objections to the Terni court before the papal auditor. The Rieti proctor was prepared to argue from de dilationibus , cap. 2, that it was not necessary for the judge to give both sides copies of the original rescript, but that it was enough for him to read the rescript before them; and the Rieti proctor was prepared to show three instruments which would prove that the prior had read the papal letters and had transmitted to the San Silvestro side the tenor of the letters word for word, checked against and compared with the rescripts themselves. As for safety, the Rieti proctor claimed, certainly the war of Bertuldo (the man with the salty mouth) could not have kept the San Silvestro side from coming to Terni, especially since in those days Bertuldo, besieged by the imperial army in Antrodoco, could not have hurt anyone, nor was anyone hurt on the road to Terni: it was a frivolous objection. Finally to the third objection—the Rieti answer was that it could of course he decided by arbiters, but that it certainly was not true that Terni was more than two days from San Silvestro, maxime because it was not more than a one-day trip.[40] Like the San Silvestro side, the Rieti side sought expenses, which it estimated at twenty-one lire.

Evidently the papal auditor was unsympathetic to the Rieti proctor's rebuttal because, on 21 February 1234 in the palace of the Lateran, before witnesses (Tebaldo the papal chaplain and the scribes Nicola Spina and Jacobus Villani from Spoleto), an imperial scriniarius , Aimo called Ypocras, recorded and redacted the viva voce appeal made by Rainaldo, proctor of the bishop of Rieti, against the sentence handed down by Giovanni Spata.[41] The case then moved a step higher, in Rome itself, and both sides prepared to be heard by Sinibaldo Fieschi, cardinal priest of San Lorenzo in Lucina (and later Pope Innocent IV). The clerks of San Silvestro made their scriniarius , Nochero, their proctor to appear before the cardinal; and they sealed their procuratorium with the chapter seal. Rainaldo appealed the Spata sentence before the cardinal and presented to him the Rieti case, with its request for a fourth of San Silvestro tithes, oblations, and mortuaries "according to the common law of the church," and also with a request for expenses now estimated at fifty lire of the senate.[42]

A half-century later in November 1282 an abbot (angelus abas ) and five or six canons of San Silvestro again present themselves at San Silvestro, next to the church, in order to make their syndicum siue yconimum, actorem et nuntium to appear before Pietro da Roma, the vicar of the bishop of Rieti (Bishop Pietro da Ferentino), who had excommunicated the abbot and canons after they had, they say, appealed to the pope.[43] Neither the abbot nor any of the six canons seem to have survived from the 1230s dispute. The document, as its formal structure makes clear, was written in the Regno, by a notary, by papal authority, Gualtiero (da Preturo). The chosen syndic was Bartolomeo, archpriest of San Tommaso Vigliano, whose church had been one of those in dispute in the 1230s.

The San Silvestro case is a lesson in diocesan cultural geography. In it the diocese of Rieti is placed within a larger area, a kind of triangle with its points in Bominaco, Terni, and Rome; the center of the whole triangle is the capitular-episcopal complex in Rieti. It is geography because thickets of clerks gathered cannot be considered less geography than thickets of heather or broom, or their placement less geographically significant than that of limestone or oak (quercus or robur ). About diocesan boundaries the case is variously revealing. It focuses on the unstable boundary between Rieti and Forcone. It shows the penetrability of boundary, as it moves across boundaries; and in the same movement it shows the significance of boundary, the advantage to San Silvestro of Forcone and Valva-Sulmona, the dioceses of the Hohenstaufen kingdom, and the advantage to Rieti of Terni. But content and boundary are again inseparable: immune, or wanting to be, clerks and monks against the order of diocesan government, as at Sinizzo. And always beneath those elements subject to category are the hidden persuasions, tastes, and animosities, the jealousies and ambitions of individuals, hidden beneath the surface of the text, but in some ways suggested by the clustering in the texts of blood brothers and brother monks.

Overwhelmingly apparent in the case is the presence of clerical groups meeting together, living together, talking together, deciding together—the logical social and legal extension of the matrix church with its collegiate body of canons. It would not seem absurd to say—as one looks at the San Silvestro case—that diocesan boundaries are what separate one set of clerical collegiate groups from another. At the same time the nature of movement within and across boundaries is striking: the abbot of Bominaco (and does it matter whether he is quer-

cus or robur ?) changing his surrounding groups as his itinerary progresses; the men of Sinizzo following the Rieti proctor; the travelers' dodging around besieged Bertuldo, with that action's questioning of the nature of war's inhibition; the quick movement of the Rieti canon proctor, and the accessibility of Rome, and important men there.

The suggestions of the other "Rainaldo" case, the case of Santa Croce in Lugnano, and the questions it asks and answers—at least as it is seen here—are quite different ones. The structure of its evidence is different, too. It has left fewer documents, only fourteen of them.[44] They deal with a much smaller geographical area, tighter, closer to the center of the diocese; and the area which they offer is that of the area that produced the case rather than that of its courts. Although almost all of the documents which are of particular interest come from one not quite datable moment in time, and are the recorded responses of witnesses to that time's questions, one of the case's distinctive values is the presentation of a long, stretched out chronology. The case's matter as well as its witnesses' attestations remind its observer of the San Leopardo case, to which it, in its central events, is very close in time: it explores the powers of a lay patron in a changing world. But it adds to San Leopardo's kind of information a revealing spray of violence.

From a Rieti point of view, the two cases had different results. Ferentillo, later evidence makes clear, won its case with Rieti over San Leopardo. The ruined church outside of Borgocollefegato (Borgorose) is called San Giovanni in Leopardo or San Giovanni Leopardi, because when at the beginning of the fourteenth century Boniface VIII gave the deformed house of San Pietro Ferentillo (locally within the diocese of Spoleto), for "reformation," to the canons of San Giovanni in Laterano, San Pietro carried San Leopardo with it. This movement interprets rather surprisingly the suggestion of an Innocent III letter reviewing the work of an auditor (Leone Brancaleone, the cardinal priest of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme) in the case and dated 26 April 1213 (preserved in copy, but not in Rieti); the letter seems to place San Leopardo pretty clearly "infra limites dyocesis" of Rieti, but it makes seem decisive the placing of San Leopardo among Ferentillo's churches in Bishop Tommaso's list (with the qualification of half procurations). Quite the opposite is true of Santa Croce Lugnano: later evidence simply tucks it neatly under Rieti control, and Bishop Tommaso's list does not give it to the Hospitallers.[45]

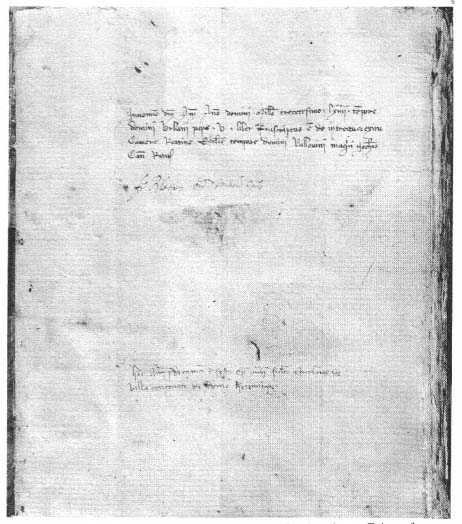

Two documents, at fifteen years distance from each other, specifically tie Bishop Rainaldo de Labro to the Santa Croce case. In May 1215 (plate

21) and again in August 1230 Rainaldo and his chapter (in the first Rainaldo cum capitulo nostre ecclesie and in the second Rainaldo cum concanonicis nostre ecclesie ) make for themselves a proctor (or in the second document an yconimum ) in their dispute with the Hospitallers of San Basilio Rome over the church of Santa Croce in Lugnano—in the first case specifically over Santa Croce, and in the second specifically before the papal chaplain Magister Andrea da Velletri (de Villitro ) who had been made auditor by the pope.[46] (The 1215 proctor is a canon, the priest Paolo; and the document's witnesses include the proctor's nephew as well as Berardo Dolcelli, the same man presumably as a clerk who had seen Bishop Benedetto visiting San Leopardo.) It is not certain, however, that Rainaldo was bishop at the time the witnesses' attestations were gathered. They were gathered at a time when Bishop Adenolfo had retired from the see but was still believed to be living, as a monk at the Cistercian house of Tre Fontane just south of Rome, that is, after 1212. The attestations talk of a bishop-elect, an electus , as if he were presiding over the church of Rieti: this could be either Rainaldo before his consecration or, following Bishop Tommaso's list, his predecessor Gentile de Pretorio, who remained an elect and who was active as late as 3 March 1214.[47]

Although the last abbot of Santa Croce cannot remember what practice was when Santa Croce had belonged to the monastery of Farfa, because he had not been born (nescit quia non dum natus erat ), some of the memories evoked in the case are very long memories. Berardo de Vico (or Vito), who had been cellarer, had a memory that stretched back seventy years; and he had seen nine abbots inducted at Santa Croce. The priest Paolo himself said that he had been a canon in the church of Rieti for thirty years, and Jacobus for more than forty. The witness Tomeo de Rater' says that he had been with Bishop Dodone for twelve years and to the time of his death; and the witness Teodino remembers to a time before the destruction of the city of Rieti (in 1149 by the army of Roger of Sicily).[48] As the past is remembered, the future is penetrated. The most legally significant document which is preserved from the case, the carta liberationis , or charter of liberty, granted by the lay patron Rainaldo de Lavareta to the abbot Giovanni, was made, at Rainaldo's request, by the scriniarius Berardo Malabranca in March 1196; but an authentic copy of it was made by the scriniarius Tomeo in July 1255 (and of two witnessing canons of San Ruffo, Rieti, one bore the same name as the Rieti yconimus of 1230).[49] The documents preserved from the case thus stretch from the time of Bishop Adenolfo to

that of Bishop Tommaso; and the memories penetrate deep back into the long reign of Bishop Dodone.

The pieces of past that the memories recall, of course, in some part differ from each other; but put together they present a reasonably comprehensible story. The grandfather, according to witness, of the Lord Rainaldo de Lavareta (who, Rainaldo, also according to witness, was the father of Bishop Adenolfo de Lavareta) had received the church of Santa Croce Lugnano in an exchange with the abbey of Farfa. In 1196, according to the authenticated copy of the original carta donationis or liberationis , Rainaldo, for the redemption of his soul and those of his relatives (pro redemptione anime mee et meorum parentum ), had made a grant inter vivos to the Abbot Giovanni and his clerks and their successors of all the rights that he, Rainaldo, had had in the church during the occupancy of a previous abbot. He made the church free of himself, its patron. The abbot, Giovanni, in turn (with, according to him, the counsel of Bishop Adenolfo) gave the church to the Hospitallers of San Basilio in Rome. He and the clerks of Santa Croce were received as brother and oblates of San Basilio; and the transfer was made with earth and stones, with branches of fig and vines of grape from Santa Croce and from one of its dependencies, San Massimo. The prior of San Basilio took counsel so that the transfer was canonically correct and brought papal confirmation of transfer to Rieti, according to Giovanni. He also brought papal letters to the canons of Rieti ordering them not to molest San Basilio over the gift of Santa Croce.[50]

But molest they did. A group of clerks and servants from the cathedral church, a group which included canons—the priest Paolo, the priest Rainaldo, Master Enrico medico, and Siginulfo—took the keys to the house of the sons of Tedemario, where the abbot of Santa Croce resided when in Rieti and where Santa Croce had a storeroom. They entered the house, measured the grain in the pozzo (its container) with a stick, and opened the chest where bread and fish and victuals were, and ate the fish they found prepared there, and they took the priest Egidio, the abbot's companion and by then an oblate of San Basilio, as a captive to the cathedral church of Santa Maria, Rieti. The cathedral group also went to the Rieti church of San Giovenale where valuables of Santa Croce or its chapels were deposited (or the canons gave orders to the clerks of San Giovenale that they bring them those valuables) so that they might be carried away: a little library of seven common books, twenty-six vestments and cloths used in services (including three pannos altaris cruciatos , three crossed altar cloths), two pewter chalices, and

one ox or bull or cow (unum bouem ).[51] This violence was appealed by the preceptor and brothers of San Basilio who, their witnesses claim, had already appealed to the pope before the violence occurred.

The eating of the fixed fish, the sequestering of the ox (or bull or cow), the antiphonals, and the missals, the episode of violence could have been an uncontrolled flash of anger or it could have been a calculated expression of power. Either way, it was an explosive, relatively superficial (or perhaps, like the sheds, ritualistically legal) incident in a dispute over the definition of authority within the church, over the structure of diocese. A cardinal point in the Rieti position was that "Ecclesia Sancte Crucis . . . sita est in diocesi Reatina." That the church was physically within the diocese was not in dispute. Lugnano is only about eight kilometers northeast of Rieti, close to the diocesan center. Rieti wanted testimony which would establish that "the church of Rieti had had and held the church of Santa Croce, just as it did the other churches of the diocese (de episcopatu Reatino ) in spiritualities and temporalities, for a long time." And a Rieti witness, Tomeo the companion of Bishop Dodone, testified to another aspect of the ordinariness of Santa Croce, "that the Lord Rainaldo de Lavareta had held the church of Santa Croce just as he held the other churches de terra sua and that he was patron of this church just as he was of the other churches de terra sua ."[52]

Rieti attempted to establish this ordinariness of Santa Croce much as it had attempted to establish the past ordinariness of San Leopardo, by showing that the bishop had acted as diocesan in and to Santa Croce and its three chapels. In the Santa Croce case witnesses testify that bishops were received, and with procession and holy water, at Santa Croce, and were received and were served at San Massimo, that they received imposts—cathedraticum, capitulum , tithes, procurations—and other services from Santa Croce, that exenia were given at Christmas, Easter, and Assumption, that clerks were ordained, and prelates invested, by the bishop, that the abbot and clerks were called to synods and they came, that interdicts were observed, and sacred oil received, that the clerks who offended the abbot or other clerks were called to the bishop's curia where justice was done (as when Giovanni Gentili struck abbot Giovanni with a knife), and that, in a word used repeatedly in this case, abbot and clerks were vasalli of the bishop and church of Rieti and pledged fealty to them.[53]

The pieces of memory that contribute to the Rieti party's overall claim are often limitedly specific and particular:

Pinzono swears that in the time of Bishop Benedetto when he was a sergeant (or servant: seruiens ) he went to Santa Croce with a palfrey of the bishop's and stayed there for two weeks and the abbot gave him and the horse victuals and gave him a shirt out of respect for the bishop; and in the time of Bishop Adenolfo he was seneschal (senescalcus ), and he saw that the bishop received seruitia from the church of Santa Croce just as he did from other churches—he himself saw it because he went with the bishop.[54]

Witnesses speaking for San Basilio spoke of the patron Rainaldo de Lavareta's control of Santa Croce. Berardo di Vico, the cellarer who had seen nine abbots in the church of Santa Croce, testified that Rainaldo sent them and, when he wanted to, removed them, without asking the bishop (sine requisitione episcopi ). And, in fact, the testimony reveals the removal of Abbot Giovanni himself, either by Rainaldo and his son Bishop Adenolfo, or by Rainaldo's son Matteo, and Giovanni's reinstatement and finally the confirmation of Rainaldo's carta liberationis by Matteo.[55] Abbot Giovanni's own testimony about services performed and promises given is especially provocative. Giovanni admits that he swore an oath to the church of Rieti, but it was when he was ordained priest and not at Santa Croce; and he swore as a simple priest and not as rector of the church of Santa Croce (tamquam presbiter simplex non tamquam rector ecclesie Sancte Crucis ). He said that thrice a year seruiebat in exeniis to Bishop Adenolfo for the church of Santa Croce, but he gave the exenia to Adenolfo not as bishop but because Adenolfo was the son of Rainaldo (non tanquam episcopo sed quia filius erat eiusdem Ray naldi).[56]

The Rieti party sums up this sort of testimony from San Basilio-Santa Croce witnesses by saying that they claim in general that Rainaldo presided over the church of Santa Croce—as does the witness Buonuomo specifically that he saw Lord Rainaldo preside over (presidere ) the church for (in Buonuomo's case) thirty years. But this is impossible, the Reatines claim, because a layman (laicus ) cannot preside over (presidere ) a religious place (locum religiosum ); and they cite Pope Alexander III in the titulus "de prescriptionibus."[57]

Rainaldo, the agent, dead, is mute. He cannot respond or add his voice to this case. That he had a voice of a certain timbre, one might guess; in fact it is still audible. He can be heard being quoted by the witness Oddone, archpriest of San Ruffo, Rieti, in a case from 1181—or rather in double quote because Oddone is repeating what he heard Gualtiero de Trozo say. Gualtiero said that Rainaldo came to him with a group of knights and said to him, "I have heard that you have given

your goods to the church of Santa Maria. I want you to revoke that gift and give them to me—and I will do you much good and on top of that I will give you a fief (feudum )." And Gualtiero said that whatever he had done for Rainaldo he had done because of force or fear.[58]

Rainaldo's live voice, and Gualtiero's, heard together remind their listener of their, and Bishop Adenolfo's, common background; they recall the section of the Norman kings' Catalogus baronum , which begins: "Raynaldus de Lavareta tenet a domino Rege in Amiterno Lavaretam (Rainaldo de Lavareta holds of the lord King in Amiterno, Lavareta)," and which includes among the list of those who hold of Rainaldo, "Troz . . . de eodem Raynaldo tenet . . . Roccam de Cornum."[59] Descendants of Catalogus barons are speaking, men of Amiterno, the lord with his caput at Lavareta or Barete, from families who seem to dominate the diocese of Rieti in 1200, but whose central holdings will be removed from it when the diocese of L'Aquila has been successfully constructed. That Lugnano and Santa Croce themselves, although they were in the center of the reduced diocese of Rieti, were of the Regno, the kingdom of Naples, one is reminded by the former, perhaps accidental, preservation at Santa Croce (when it itself was still preserved) of the most Angevin-seeming (probably because of its being carved by a French master) work of thirteenth- or fourteenth-century art in the diocese, the ivory Madonna of Lugnano.[60]

The most quickly memorable remnants of the Santa Croce case's attestations are sharply physical: not only the ox and the little library and the prepared fish eaten in the house of the Tedemarii, but also the pewter chalices, the keys and the knife, branches of fig and vines of grape, horse fodder and a shirt. They seem to have flown to the memory of the witnesses, and they stick in our memories. They are not just convenient mnemonic devices, peripheral—"'though of course I had on my trousers,'" as Schinkel said in The Princess Casamassima —they are what the story of Santa Croce is about; they tie its abstractions to a different kind of lived life, a specific one.

But the abstractions of the Santa Croce case, or, more pompously but perhaps better, the historical forces visible in it, are central and important ones. The potent lay patron, Rainaldo de Lavareta, displays in himself an antique figure. His son was bishop. He gave churches to themselves. And in his acts he did not seem to recognize, to think, that a diocese was a different sort of territory, jurisdictional territory, from his or other men's lands; or, if he did, he saw the difference as something frail and insubstantial, which ought not to interfere with a lord's pa-

tronage—perhaps particularly when that patronage was meant to save his soul.

Rainaldo's acts, however, joined by Abbot Giovanni's, provoked from the representatives of the church of Rieti, from its canons and bishop and their representatives, a further definition of diocese, a further overt realization of what jurisdictional diocese meant—this most specifically and consciously in their restraining and putting in place the rights of the lay patron, but also in their again of necessity recalling those touchstones of diocesan reality which demonstrated that a specific place or specific places were part of a diocese, within its real boundaries: so they talked of the reception with procurations of the visiting bishop, the source of sacred oils, the ordination of clerks by the bishop, the use and validity of the bishop's court, the giving and receiving of customary gifts and rents and fees, of cathedratica , capitula , tithes, and exenia , and the successful summoning of clerks to episcopal synods (as the canon Rainaldo said, "He saw Bishop Dodone call to synod the abbots and clerks of Santa Croce, and they came just as did the other clerks of the diocese").[61] The clerks of Santa Croce were, in a word that makes the Reatine clergy seem almost as antique as Rainaldo de Lavareta, the "vassals" of the church of Rieti.

The indecisiveness, the blurred boundaries, of some of the Santa Croce evidence (were things given to the bishop or to the patron's son? was the oath taken as priest or rector?) recalls, makes analogy to, the blurred indecisiveness of parts of the early thirteenth-century diocese's physical boundaries. The coherence and definition which that diocese could find for itself, or which witnesses living within it could look for and find in it, are not those which would develop in the century which followed the episcopate of Bishop Tommaso the Corrector, in the century which followed the loss of the Amiterno territories to L'Aquila.

Tommaso the Corrector, who came from that curia where dioceses were thought of, was an imaginative and effective bishop; and he was supported by the strong and serious pope from whose curia he had come. Tommaso marked the center of the diocese with a new campanile. He made an extended and orderly list of his diocese's churches. He drew a verbal map of the diocese with an impressively indecisive, because physical, appreciation of its geography; and he drew it with an almost portolan concept of map-making. He offered himself as an arbiter to disputants within the diocese. He gathered back strayed rights and incomes, and he questioned immunities. He can be seen to be laying, probably quite consciously, the foundations for a new and more

stable kind of diocese and diocesan government appropriate to the lengthy period of relative peace which might perhaps have been predicted from the time of the death of Frederick II in 1250. But Tommaso's gathering of rights and incomes, impressive as it seems, particularly in the context of the evidence which exists for his actually trying to understand the geography of his whole diocese, does not seem in its style or in his understanding of diocesan rights very different from that of his predecessors, particularly from that of Rainaldo de Labro and his canons, whose work Tommaso was almost forced to minimize. Tommaso's definition of diocese echoes Rainaldo's.

Evidence from the San Leopardo, Santa Croce, and San Silvestro cases show that Bishop Adenolfo de Lavareta, Bishop Rainaldo de Labro, and canons of Rieti were actively interested in preserving diocesan structure and in exercising the rights of bishop and cathedral church. This interest did not exclude the sacramental and the sacred. It included rights of visitation and summoning to synod (and for both the pontificate of Bishop Dodone was recalled, and of both the exercise was proclaimed on Tommaso's campanile). But visitation, at least in the testimony, seems primarily a matter of ceremonial reception and procuration—natural perhaps in litigation evidence, but this is the evidence that survives. And no one thought to recall the content of any synod. (It is, of course, possible that at each diocesan synod after 1215 the decrees of Innocent III's Fourth Lateran Council were read aloud as an interpretation of that council's canon 6, sicut olim , in this diocese with no provincial metropolitan set above it.)[62]

Viewed from outside (and later) the early thirteenth-century Reatine concept of diocese seems very much one of pennies paid and formal rights demanded. It is not at all clear, at least from witnesses' testimony, what pastoral duties early thirteenth-century bishops of Rieti, in their peregrinations, thought they were performing. In spite of ordinations, baptisms, and sacred oils, and of the real and conscious participation in "church" of lay Christians, the early thirteenth-century diocese really does seem to find an image of itself, although perhaps an exaggerated and distorted one (and one that should not be interpreted as too sharply distinguishing between clergy and laity), in Oderisio di Buonuomo's standing by the outside wall of the church of San Leopardo while the Mass was being sung within. Clear as daylight is the fact that he was standing in a diocese, no matter how ill-defined its boundaries were, full of colleges of secular clergy, and of important family ties.

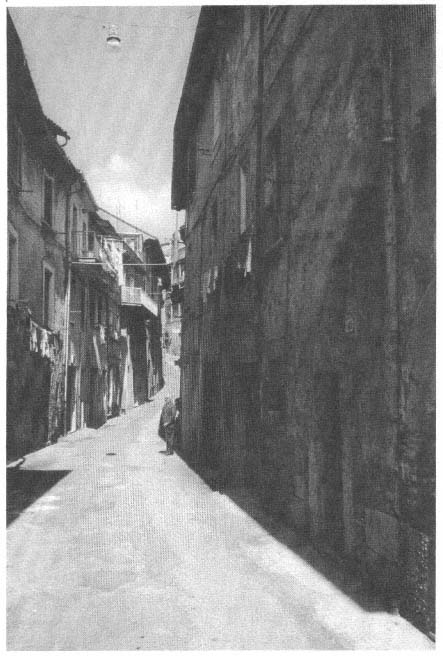

9.

Rieti, urban curvilinear internal street assumed to have been formed before the

middle of the thirteenth century. Photograph by Corrado Fanti, reprinted

from Marina Righetti Tosti-Croce, ed., La sabina medievale

(Milan, 1985), by permission of the Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti.

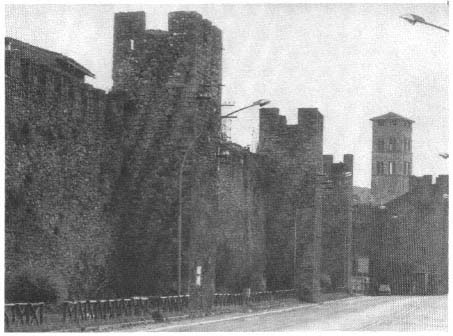

10.

Rieti, the thirteenth-century wall by the Porta Conca and Sant'Agostino, the

northern boundary of Rieti. Photograph by Corrado Fanti, reprinted

from Marina Righetti Tosti-Croce, ed., La sabina medievale

(Milan, 1985), by permission of the Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti.

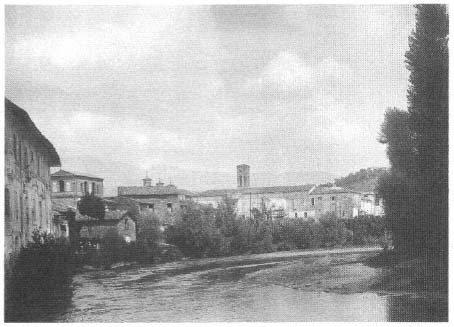

11.

Rieti, the river Velino and San Francesco, the southern boundary of Rieti. Photograph

courtesy of the Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione, Rome.

12.

Rieti, looking toward the church of San Francesco from the south across the Velino.

Photograph by Barbara Bini.

13.

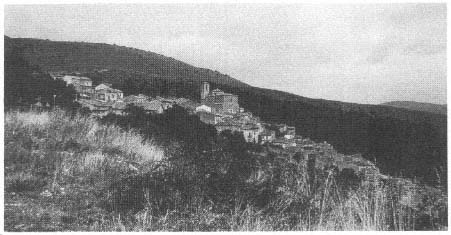

The village of Secinaro. Photograph by the author.

14.

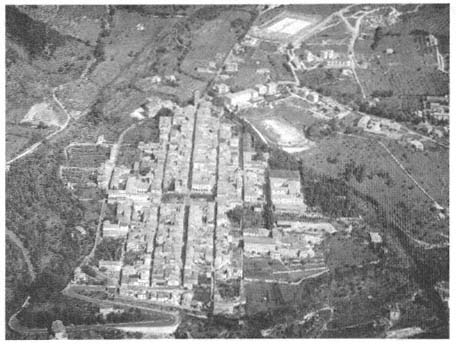

Aerial view of the new town of Cittaducale. Photograph by the Ente

Provinciale per il Turismo, Rieti, reprinted from Marina Righetti

Tosti-Croce, ed., La sabina medievale (Milan, 1985), by permission of the

Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti.

15.

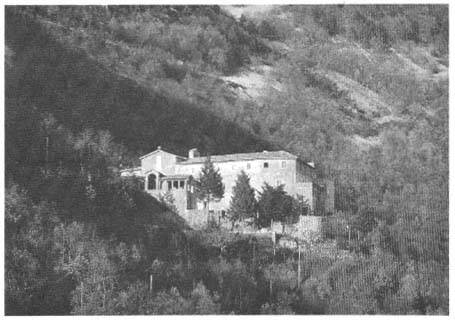

The hermitage of San Giacomo, Poggio Bustone, near Rieti, one of the three early

important Reatine Franciscan hermitages. Photograph by Corrado Fanti, reprinted

from Marina Righetti Tosti-Croce, ed., La sabina medievale (Milan, 1985), by

permission of the Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti.

16.

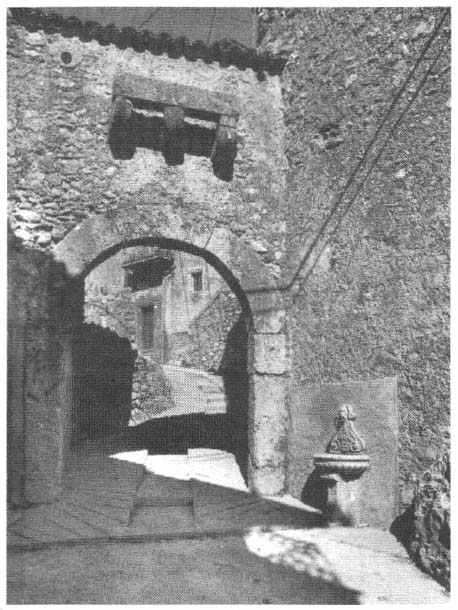

Rocca Ranieri (Longone Sabino), a rural castro, formerly subject to the Benedictine

monastery of San Silvestro Maggiore, seen through a gate. Photograph by

Alessandro Iazeolla, reprinted from Anna Maria D'Achille, Antonella Ferri,

and Tiziana Iazeolla, eds., La sabina: Luoghi fortificati, monasteri e abbazie

(Milan, 1985), by permission of the Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti.

17.

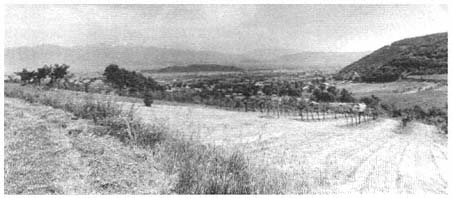

The conca of Rieti seen from the west, from beneath the ruins of the Cistercian

monastery of San Pastore, looking toward the Monti Reatini, with a spur of

San Matteo to the right of the photograph. Photograph by Barbara Bini.

18.

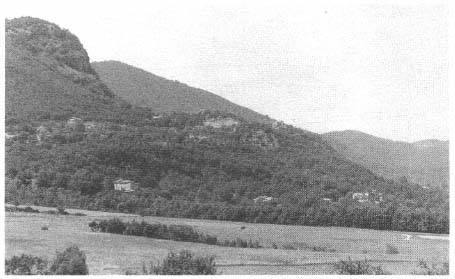

The village or castro of Greccio seen from below and from the south, from near

San Pastore. Photograph by Barbara Bini.

19.

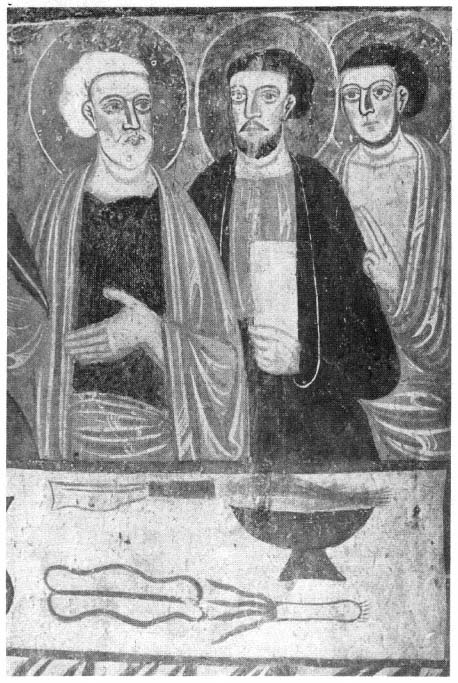

Late thirteenth-century fresco of the Last Supper in Santa Maria ad Cryptas at Fossa,

detail, leek on table. Photograph reprinted from Guglielmo Matthiae, Pittura

medioevale abruzzese (Milan: Electa, n.d.).

20.

Rieti, Archivio Capitolare, first folio of the paper Liber Introitus et Exitus of 1364

(that is, 1 July through the following June), prepared by the canon Ballovino, with

the record of that year's (presumably 1365) Saint Mark's day preacher, the

Augustinian Hermit Nicola da Villa Conzonate. Photograph by Barbara Bini.

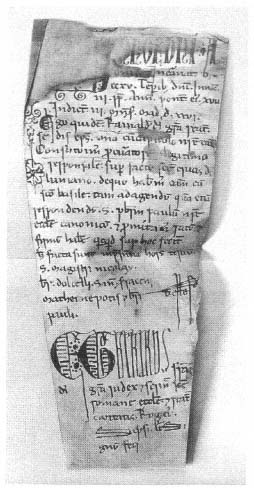

21.

Rieti, Archivio Capitolare, IV.G.3, parchment

document from 26 May 1215 in which Bishop

Rainaldo (de Labro) and his chapter make the

priest Paolo, one of the canons, their proctor

in the case with San Basilio, with witnesses

including Matteo the nephew of the priest

Paolo. The document was redacted by the

judge and scriniario , Berardo Sprangone.

Photograph by Barbara Bini.

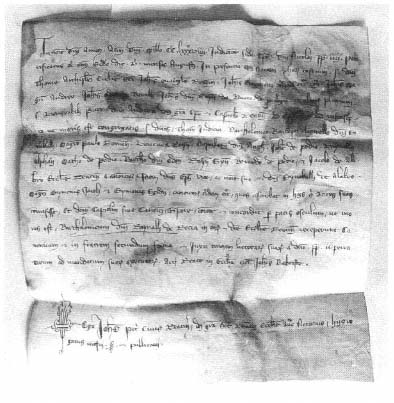

22.

Rieti, Archivio Capitolare, VII.F.3, notarial act written by Giovanni di

Pietro which records the reception of Bartolomeo de Rocca as canon

by Bishop Andrea and the canons of Rieti, including three identified as

"de Podio," on 5 August 1289. Photograph by Barbara Bini.

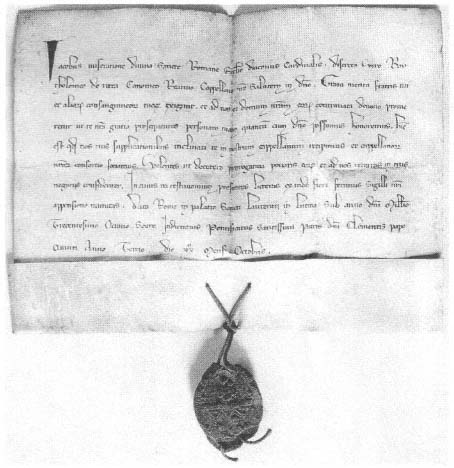

23.

Rieti, Archivio Capitolare, VII.A.4, Cardinal Giacomo Colonna, out of gratitude for

the service of Bartolomeo's family to the house of Colonna, receives Bartolomeo

de Rocca, canon of Rieti, into his consortium of chaplains and records the act in a

sealed letter of 20 October 1308. Photograph by Barbara Bini.

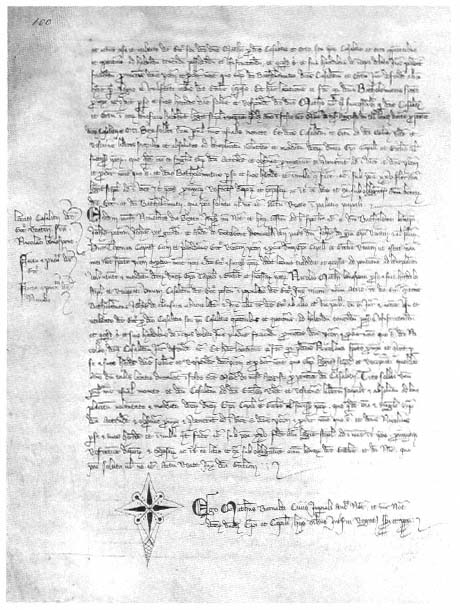

24.

Parchment Book of Matteo Barnabei, page 100, record of acts from November 1317 with

Matteo's notarial sign and subscript at end of gathering. Photograph by Barbara Bini.

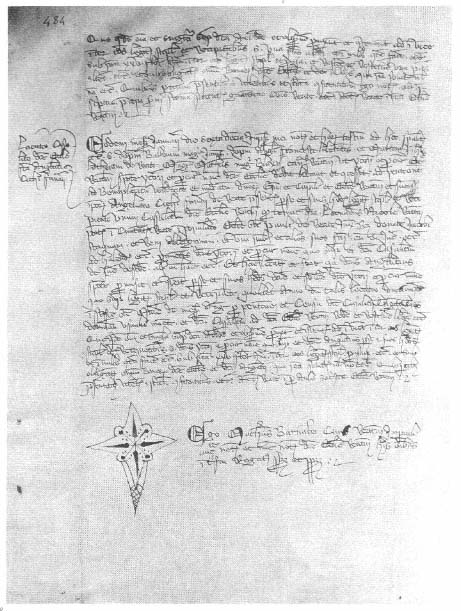

25.

Parchment Book of Matteo Barnabei, page 484, record of act from January 1342 with

Matteo's notarial sign and subscript at end of gathering. Photograph by Barbara Bini.

26.

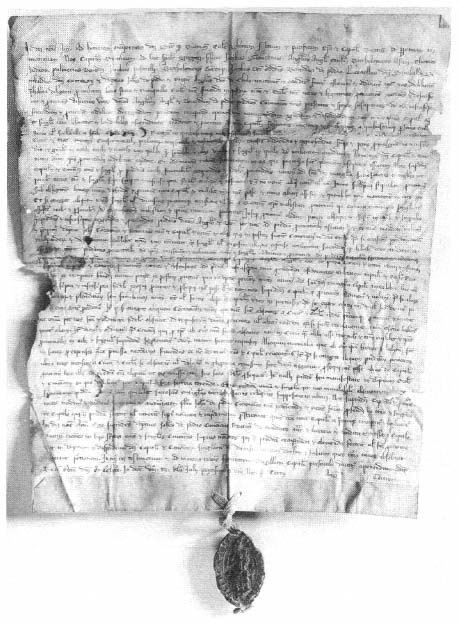

Rieti, Archivio Capitolare, III.C.3, the canons of the chapter of Rieti make two of

themselves proctors, an act recorded in a document of 20 June 1280, sealed with

the chapter seal. Photograph by Barbara Bini.

27.

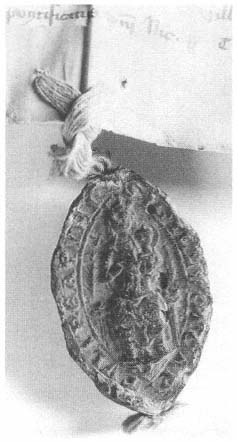

Chapter seal from 1280, Archivio

Capitolare, III.C.3. Photograph by

Barbara Bini.

28.

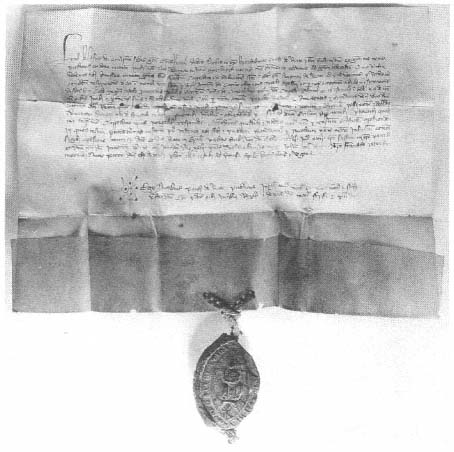

Rieti, Archivio Capitolare, VII.G.10, sealed and notarized (by Nieola di Paolo of Rieti)

letter from Bishop Biagio, instituting to the chapel of San Salvatore in the church

of San Lorenzo, Rieti, Bartolomeo Cicchi, a priest of Rieti who had been presented

by Giovanni de Canemorto, the chapel's patron, and ordering that the new chaplain

be inducted by a canon of Rieti, 23 January 1356. Photograph by Barbara Bini.

29.

Seal of Bishop Biagio, from 1356, Archivio

Capitolare, VII.G.10. Photograph by

Barbara Bini.

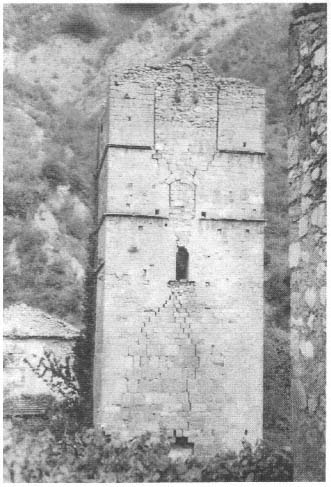

30.

Tower in the ruins of the monastery of San Quirico.

Photograph by the author.

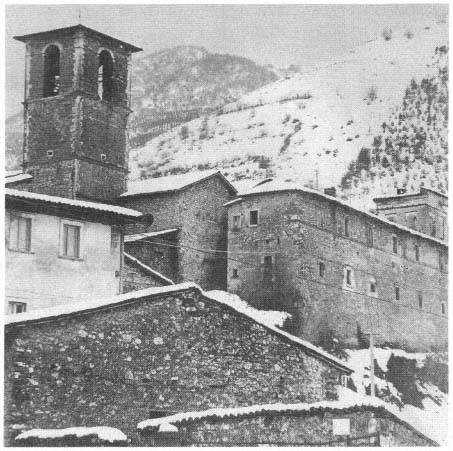

31.

San Francesco, Posta (Machilone). From the Resource Collections of the

Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, Hutzel Archive.

32.

San Francesco, Rieti, choir fresco, the presepio at Greccio. Foto Hutzel, Rome.

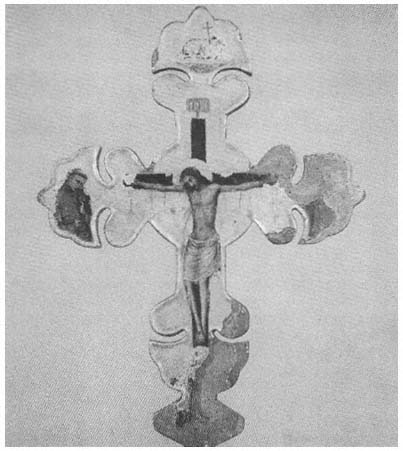

33.

Fourteenth-century painted (gold background) processional cross

from San Francesco, Posta, now in the Museo Civieo of Rieti: reverse,

on which Franciscan saints and a dead Christ replace Mary, John, and

the live Christ of the front of the cross. Photograph by Corrado Fanti,

reprinted from Marina Righetti Tosti-Croce, ed., La sabina medievale

(Milan, 1985), by permission of the Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti.

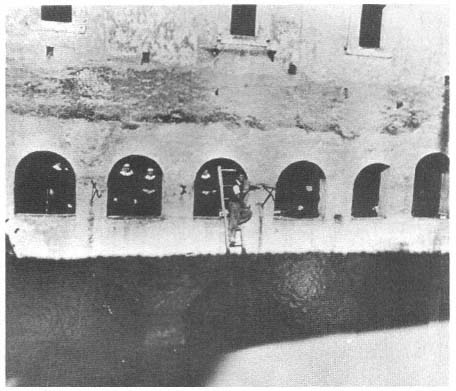

34.

The nuns of the monastery of Santa Filippa Mareri and the rising waters of the

dammed Salto. Photograph by Barbara Bini, copy of photograph in the collection

of the nuns of the monastery of Santa Filippa, by permission of Madre Margherita,

the abbess.

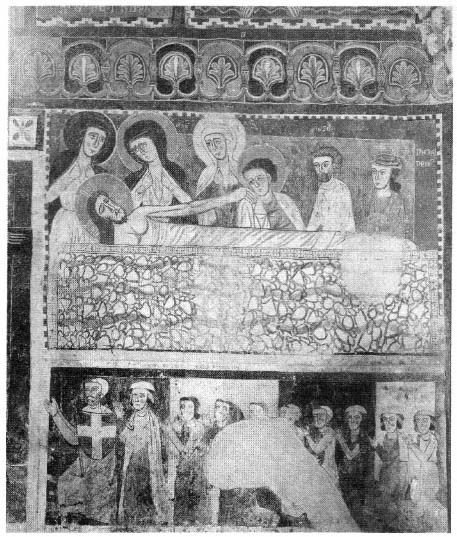

35.

Fossa, Santa Maria ad Cryptas, late thirteenth century frescoes with heavenly and

earthly witnesses to and mourners of the burial of Christ. From the Resource

Collections of the Gerry Center for the History of Art and the Humanities,

Hutzel Archive.

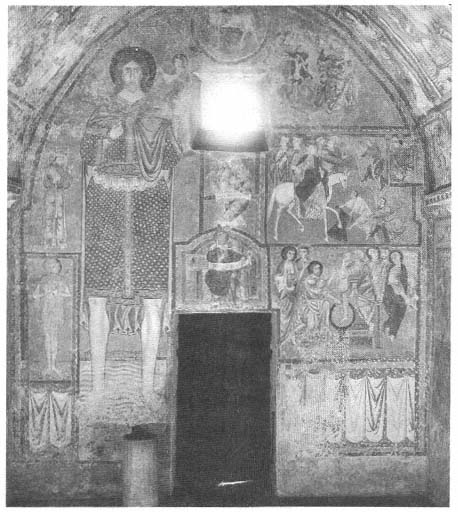

36.

Bominaco, San Pellegrino, late thirteenth-century frescoes on the entrance wall.

From the Resource Collections of the Gerry Center for the History of Art

and the Humanities, Hutzel Archive.

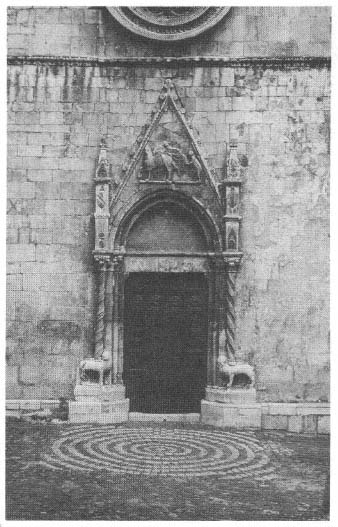

37.

Gagliano Aterno, Saint Martin, and the beggar, above the

door of the parish church of San Martino.

Photograph by the author.

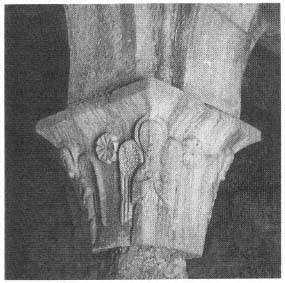

38.

Angel capital from the old ciborio of the cathedral of Rieti,

now in the Palazzo Cappelletti in Rieti, probably carved

before 1225, and removed from the cathedral in 1803.

Photograph courtesy of the Istituto per il Catalogo e la

Documentazione, Rome.

39.

Angel capital which was, until stolen, in the crypt

of the ruined San Leopardo, Borgocollefegato.

Photograph by the author.