Four—

Problems of Symbolic Interpretation

Because Panofsky's interpretation of the Arnolfini double portrait provided the framework for the original presentation of the theory of disguised symbolism, it has had consequences far beyond the analysis of a single picture.[1] A few of these will be addressed in this concluding chapter.

The idea that symbols in early Netherlandish painting might be hidden in a sacramental context actually seems to have originated with Max Friedländer, who suggested as early as 1924 that there is "a mood of sacramental symbolism" about the London panel and that thus "even the most humble thing . . . is endowed with the meaning and importance of a ritual object."[2] From this interpretation it was but a short step to Panofsky's assertion that the painting "impresses the beholder with a kind of mystery and makes him inclined to suspect a hidden significance in all and every object, even when they are not immediately connected with the sacramental performance."[3] Initially Panofsky's approach to what he termed "transfigured reality " remained tentative and cautious: "I would not dare to assert," he wrote in the 1934 article, "that the observer is expected to realize such notions consciously."[4] But by the time Early Netherlandish Painting was written, that is just what he did. Earlier qualification was dropped as the theory became a "principle" that could be applied categorically to the double portrait: "All the objects therein bear a symbolic significance" because the "nuptial chamber" is "hallowed by sacramental associations." And with a rhetorical flourish "disguised symbolism" was ensconced in Van Eyck's world, where, it

was said, "no residue remained of either objectivity without significance or significance without disguise."[5]

Because Van Eyck was further credited with having first "systematized the principle of 'disguised symbolism,'" it followed that such symbols might also be found in other Netherlandish masters. But at this point Panofsky retreated from his universalizing approach, at least with reference to painters besides Van Eyck. Writing about the lilies in the Mérode Altarpiece (see Fig. 47), he noted that if we did not know from hundreds of other Annunciations that the lily was a symbol, "we could not possibly infer from this one picture that it is more than a nice still-life feature." And to deal with such potential ambiguities, Panofsky proposed "the use of historical methods tempered, if possible, by common sense" to ascertain whether a particular object was imbued with symbolic meaning.[6]

In the end Panofsky succeeded in mystifying a whole school of early northern painting, and his views about disguised symbolism have exerted a profound influence on iconographic scholarship for more than half a century. In what follows my purpose is not to engage in a systematic critique of the various symbolic interpretations he proposed, some of which have already been questioned by others. Instead, I take several of these now classic examples of presumed symbolism in the double portrait as a point of departure for further discussion, using them as illustrations of methodologically unsound iconographic interpretation, with the aim of placing the picture in a comparative historical context that offers a better understanding of fifteenth-century mentalities.

It seems appropriate to begin by asking what can be known with reasonable certainty about the relationship between reality and symbol in Van Eyck's work. In contrast to the widely held view that his pictures are replete with hidden meaning, the unequivocally symbolic elements in the painter's work are strikingly commonplace. In the Adoration of the Lamb panel of the Ghent Altarpiece, for instance, the individualized saints are identified by a conventional use of traditional attributes: Barbara with her tower, Agnes holding a lamb, the Magdalene carrying an ointment jar, Christopher endowed with gigantic stature, or Stephen using his dalmatic as an improvised container for the stones emblematic of his martyrdom. More unusual but no less certain, the tongue held in a pair of forceps by one of the bishop martyrs standing next to Stephen (Fig. 44) establishes that this figure is intended as Livinus of Ghent, the apostle of Flanders. And although no one could misconstrue the identity of the imposing figures of Adam and Eve in the upper register of the polyptych, the obvious has been confirmed by the illusionistic epigraphic inscriptions "Adam" and "Eva" painted over their heads.

Figure 44.

Jan van Eyck, Bishop martyrs, detail of the Adoration of the Lamb

panel of the Ghent Altarpiece, completed 1432. Ghent, St. Bavon.

Photo copyright A.C.L. Brussels.

In a work like the Madonna of Canon van der Paele (Fig. 45) remarkable verisimilitude creates a disturbing tension for the modern viewer: because the donor, who is depicted as living and mortal, shares a temporally ambiguous space with the sacred figures, the picture is mystified for us and seems to demand some symbolic reading. But here too the basic iconographic conception, found as early as the ninth century in the famous narthex mosaic of the Hagia Sophia depicting Leo VI prostrate before the throne of Christ (Fig. 46), is entirely traditional. The figures flanking the Virgin are securely identified as George and

Figure 45.

Jan van Eyck, Madonna of Canon van der Paele , 1436. Bruges, Groeningemuseum.

Photo copyright A.C.L. Brussels.

Figure 46.

Leo VI prostrate before the throne of Christ. Narthex mosaic, late ninth century.

Constantinople, Hagia Sophia. Photo copyright 1992, Byzantine Visual Resources,

Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

Donatian by conventional attributes, including the latter's spectacular wagon wheel emblazoned with five lighted candles. Still not satisfied, the painter added didactic inscriptions along the left and right sides of the frame, describing Donatian as the first archbishop of Reims and George as the Cappadocian who vanquished the dragon, information that would make these saints recognizable even without their attributes. And as if these inscriptions were still not enough, on the frame directly beneath these figures Van Eyck has carefully inscribed their names: "Saint Donatian Archbishop" and "Saint George Soldier of Christ." Since inscriptions of this type, used in conjunction with otherwise readily identifiable saints, pervade the Eyckian corpus from early works like the Ghent Altarpiece to late compositions such as the Dresden Triptych, a fundamental question about Eyckian symbolism is simple enough to formulate: Is the painter's mentality, as manifested in these didactic inscriptions, which are not far removed in either form or purpose from those in works of art as early as the twelfth century,[7] really compatible with the complex meanings modern critics claim to find in the ordinary household objects depicted in Van Eyck's works?

The problem can be illustrated with reference to a widely accepted example of symbolism in early Netherlandish painting. The laver and basin in the Ghent Altarpiece and Mérode Annunciations (Fig. 47) were interpreted by Panofsky as "an indoors substitute" for the "fountain of gardens" and "well of living waters" that medieval authors took over from the Song of Songs and applied figuratively to the Virgin's purity.[8] In repeating this interpretation, followers of Panofsky have added the towel nearby as a further symbol of Marian purity or virginity.[9] But from the vantage point of Van Eyck's time we can be certain that lavabos and towels were in common daily use for purposes of personal hygiene. Accordingly, a lavabo and a towel are depicted side by side—closely replicating the imagery of the Mérode panel—in the border of Hans Paur's betrothal woodcut (see Fig. 27), where they are accounted requisite necessities for any new household. The question thus arises: Is such a lavabo, used to wash what is soiled or unclean, any more likely to have been a symbol of purity or virginity for Van Eyck's contemporaries than a bathtub or washbowl would be for us? Further, since in Panofsky's view we recognize the symbolic character of the lilies in the Mérode Altarpiece only because we infer it from hundreds of other Annunciations, is it really plausible to imagine that a man or woman living in fifteenth-century Flanders, looking at the same painting, would have seen in the equivalent of a washbasin something so transcendent as a symbol for the Virgin's purity?

The disparity between the lily and the lavabo as possible vehicles of symbolic meaning is supported by a remark of Joannes Molanus, the earliest Flemish writer to be concerned

Figure 47.

Robert Campin, Annunciation panel from the Mérode Triptych, c. 1425–30. New York, The

Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection (56.70).

with Christian iconography. Writing about the Annunciation lily in his sixteenth-century treatise on religious imagery, Molanus explains that such lilies function symbolically because the Virgin did not have artificial flowers and real lilies do not bloom in March (when the Annunciation was believed to have taken place).[10] The success of modern horticulture in coaxing plants to flower out of season may cause us to forget something so basic, but the fact remains that a vase of lilies in an early Netherlandish Annunciation must have seemed as incongruous in the fifteenth century as a decorated Christmas tree would be for us in the context of the Fourth of July. It would thus appear that modern iconographers have inverted the symbolic perspective shared by Van Eyck and his contemporaries: to them it

was the incongruous and anomalous—lilies blooming out of season or bishops carrying tongues in forceps and wagon wheels with lighted candles—that functioned as symbols, whereas what was normative and commonplace in their experience cannot be presumed to have been endowed with symbolic meaning without substantive and convincing documentation.

Notwithstanding a few protesting voices,[11] Panofsky's legacy remains a pervasive force in current criticism of the double portrait in that discussion has continued to center on complex explanations of presumed symbolic or hidden meaning. Some writers have simply assumed that the picture's enigmatic character is intrinsic to the work and was consciously intended by the artist, but others have further dehistoricized the painting by highly speculative arguments that either manipulate historical documentation in unacceptable ways or claim that the meaning of the London panel has changed and become more complex with the passage of time because of inherent qualities that neither the painter himself nor his contemporaries fully realized.

These trends in scholarship and criticism can be illustrated by a sampling of writing about the picture since about 1980. The most recent general monograph on the painter, Elisabeth Dhanens's Hubert and Jan van Eyck, published that year, still closely follows Panofsky's original presentation of disguised symbolism, reminding the reader with respect to the London panel that "nothing in the picture is without significance" and "even the simplest of household objects used in daily life have their symbolic significance."[12] Discussing the painting in his 1989 book The Medieval Idea of Marriage, Christopher Brooke pushes the presumed inscrutable character of the panel to its logical conclusion when he jestingly complains that Panofsky's "inspired success has largely hidden one crucial element in the picture: that it is meant to puzzle . . . us," while the various enigmatic objects in the work are said to "enforce this fundamental point."[13] And a 1990 study by Myriam Greilsammer on marriage and maternity in medieval Flanders summarizes approvingly all the basic elements of Panofsky's thesis, including the supposedly clandestine nature of what is depicted, adding only some personal observations about "the preeminence of patrimony and the male sex" in the panel and the implied psychological overtones of a picture that in the author's view "presents us with the choice made by urban elites, in conflict with the wish of the church to control the sacrament of marriage."[14]

Other studies over the past decade have suggested further symbolic meanings for objects in the double portrait. An article of 1984 by Robert Baldwin relates the mirror's imagery to Panofsky's assumption about the sacramental character of the painting.[15] Challenging

Panofsky on an important point, Jan Baptist Bedaux rejects the idea of disguised symbolism in a study first published in 1986, but then, under the rubric "the reality of symbols," he proceeds to relate various objects in the picture symbolically to marriage ritual, including the male figure's clothing, which is interpreted as symbolic of the husband's power over and protection of his wife.[16] In the larger context of symbolic readings of early Netherlandish painting in general, others since Bedaux have also challenged Panofsky on essentially semantic grounds, arguing that although symbolic elements are present in these works, the symbols would not have been disguised.[17] Recent interpretations of the London panel by Craig Harbison and Linda Seidel require more extensive comment. Although both authors offer complex symbolic readings of the picture and in this sense remain under Panofsky's influence, they also move beyond the norms within which Panofsky operated, further alienating the picture from its historical context in the process.

In an essay on the Arnolfini double portrait first published in 1990 and then revised for a book that appeared the following year, Harbison begins by approaching the painter's work straightforwardly enough. Expressing his "determination to see with the eyes of a fifteenth-century artist," he disagrees with the "deceptive notion that symbolism can be disguised, or hidden, within realism" and rejects the idea that the double portrait has a theologically complex meaning. The reader is soon surprised to discover, however, that hidden significance abounds in the picture. Because Harbison believes "one likely function" of the painting "was to act as a kind of fertility device," he assigns many of the objects depicted therein—the dog, the bed, the shoes, bare feet ("an almost universal symbol of fecundity"), the fruit, and the candle—a sexual meaning. Yet given the "ambivalent" character of symbols—and the author apparently sees no need to decide in favor of any particular alternative when there is more than one—these same objects might also have, he suggests, a "more pious significance," as in Panofsky's classic interpretation. And although he does not interpret the picture as a contemporary record of an actual marriage ceremony, he nonetheless describes the couple's gestures as having a "calm, even sacramental quality," which is then related to the man's "controlling gesture," as "he calls forth his wife's fecundity."[18]

Harbison's essay concludes with some general remarks about the character of early Netherlandish painting. Since such works "can have multiple meanings for the various audiences for which they were created," Harbison thinks they should be read "as continuing dialogues between art and reality," suggesting that the meaning of a painting may change and grow in complexity with the passage of time, the more so since the implications inherent in any particular image "may not always have been totally intentional or apparent to artist and

patron."[19] Such views, however appropriate to the criticism of modern art, are of dubious application to the works of a fifteenth-century painter like Van Eyck: they can never be historically verified and provide only an ideological basis for saying whatever one wants about a given picture.[20] Moreover, save for the Ghent Altarpiece and possibly the Van der Paele Madonna, Van Eyck's portraits and small devotional panels were created for the private needs of individual patrons, and the mentality of the artist in approaching a commission of this sort must have been more akin to that of a manuscript painter than to that of an artist executing a public monument.

Seidel's highly imaginative approach—expounded in articles published in 1989 and 1991, and the subject of a forthcoming book—eschews any "attempt to reconstruct the original intent" of the Arnolfini double portrait, hoping rather to stimulate readers to come to their own interpretations of a painting that is said to be "a visual enigma, a riddle in which nothing is as it appears to be." Labeling Panofsky's reconstruction "consummate fiction" and adopting the point of view that one "story" about the picture is as good as another, Seidel proceeds to create one of her own.[21] The approach is novel and potentially of great interest in that the argument is developed within a rich historical matrix. But unfortunately, whenever this information is directly related to what is depicted in the panel, the historical component is lifted out of context and misapplied in a way that is analogous to iconographic explanations based on the misunderstanding or misappropriation of theological texts.

According to Seidel, Van Eyck's paintings "do not record events" but "are parts of ongoing transactions." Or again, with specific reference to the double portrait, the panel is said to be "the conflated 'reflection' of . . . a sequence of events." Nonetheless her presentation begins concretely enough, explaining what is depicted on the basis of "Tuscan marriage material," which "emphasizes the domestic ceremony" before a notary and required the consummation of the marriage as a precondition for the payment of the dowry: "We can readily imagine," she says, "that it is Ring Day, around noon." Arnolfini has entered Giovanna's room, leaving his pattens at the door, to consummate the marriage, while the "ruby bedclothes" are said to remind the viewer of the "impending carnal transaction." Extending his hand to his bride, Arnolfini prepares—in Florentine parlance—to "lead her away" (i.e. consummate the marriage), but before proceeding he promises by his righthand gesture "to uphold the terms of the prior negotiations his family has set."[22]

Seidel's hypothetical reading of the double portrait misuses or misinterprets historical information at every turn. Despite the presumed Italian background of the sitters, Italian

marriage customs, for reasons discussed above, cannot be extrapolated and applied indiscriminately to the northern circumstances of the double portrait. A characteristic example of how Seidel does this will serve to exemplify the problems inherent in her speculative approach.

Central to the argument is the mistaken idea that consummation of the marriage was a precondition for the payment of the dowry, a practice peculiar to Florence in the fifteenth century and not a "Tuscan" tradition, as Seidel claims. What led some Florentines by the middle of the quattrocento to abandon the ancient custom of paying the dowry on the day of the marriage, or ring ceremony, was the establishment of a state dowry fund known as the Monte delle doti as a way of financing the mounting public debt of the Florentine commune. In anticipation of a daughter's eventual marriage, fathers were invited to deposit funds with the Monte for a specified period, at the end of which the principal and accrued interest were available as a dowry payment to the husband, but—according to the regulations of the Monte —only after the marriage had been consummated. In the second half of the century it thus became common practice in Florence among the upper class to consummate a marriage in the bride's family home shortly after the domestic ring ceremony before the notary so that the dowry could be paid to the husband before the nozze, or ceremonious transfer of the bride to her new home.

Although founded in 1425, the Monte delle doti did not become a successful institution until 1433, when more favorable regulations were instituted, including a lowering of the minimum deposit period to five years. Because there were only two depositors in 1425 and none thereafter until 1429, and since the minimum term for a deposit in this initial period was seven years, only the two dowries covered by the original depositors of 1425 could possibly have been available for payment by the time the double portrait was painted in 1434.[23] The foundation on which Seidel's argument rests is thus undermined for two reasons. The practice of consummating the marriage in the bride's father's home before the payment of the dowry had not yet been established when the double portrait was painted. Furthermore, the practice stemmed from a Florentine institution and is thus irrelevant to the circumstances of families like the Arnolfini and Cenami whose origins were in Lucca, with whom Florence was at the time engaged in a disastrous war that led to a revolution which brought Cosimo de' Medici to power in the very year the double portrait was painted.[24]

What gives meaning to the Arnolfini double portrait is not some hypothetical reading of imagined symbols or postmodern conjecture, but rather the couple's hand and arm gestures, which established the betrothal context of the picture just as clearly for the contem-

Figure 48.

Jan van Eyck, Saint Catherine , detail from the right

wing of the Dresden Triptych, 1437. Dresden,

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister—Staatliche

Kunstsammlungen.

porary viewer as the Mérode Annunciation reveals its unambiguous subject to us. And because the panel represents the formalizing of financial arrangements associated with a marriage alliance, the many readings based on the mistaken assumption that it depicts instead a sacramental marriage rite are without justification.

The comparative approach I advocate for elucidating the meaning of the London panel is readily exemplified with reference to the female figure's supposedly pregnant state. Documented as early as the Spanish royal inventory of 1700, this mistaken inference continues to be drawn by modern viewers seeing the picture for the first time. But among those familiar with Franco-Flemish works of the fifteenth century a consensus has developed that this is not the case, for virgin saints, who obviously cannot be pregnant, also appear gravid in many contemporary representations. The woman in the London panel has thus often been compared with the Saint Catherine in the right wing of Van Eyck's Dresden Triptych, who is similarly portrayed (Fig. 48), as is the bride in the marriage vignette of Rogier's

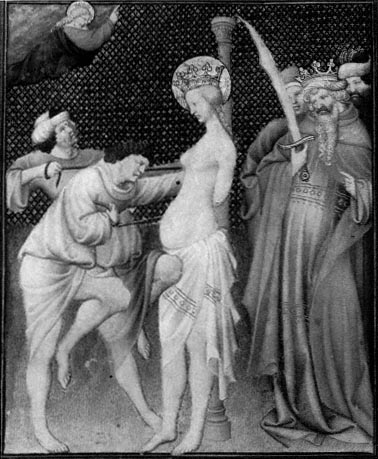

Seven Sacraments Altarpiece (see Fig. 21) as well as the Virgin and one of her attendants in Israhel van Meckenem's Marriage of the Virgin (see Fig. 50). And a protruding belly is seen in many female nudes, including again virgin saints, as in a depiction of the martyrdom of Saint Catherine in the Belles Heures (Fig. 49).[25] Whether or not this feature is explained by fifteenth-century perceptions of idealized feminine beauty, these images clearly reflect some contemporary Flemish convention whose precise meaning is no longer readily apparent.

A chapter in Christine de Pisan's Le livre des trois vertus devoted to women "who are extravagant in gowns, headdresses, and clothing" provides a useful social context for understanding Giovanna Cenami's attire. Christine, who was familiar with both the French and Burgundian courts earlier in the fifteenth century, regrets that the old rules governing dress were at the time in disarray. Whereas formerly, she says, a duchess would never have dared wear the gown of a queen, just as no countess would have dressed like a duchess, or any ordinary woman like a countess, women (as well as men) now follow the dictates of extravagance, wearing whatever they can afford, no matter how grand or inappropriate to their status: "For no one is satisfied with his estate, but everyone would like to appear as a king" ("Car a nul ne souffist son estat, ains vouldroit chasun ressembler un roy"). Using language that could apply just as well to the gown in the double portrait, Christine epitomizes this sorry state of affairs with an anecdote about a provincial woman of no particular status who had a Parisian tailor make her an extravagant garment of wide Brussels cloth with "bombard sleeves that came down to the feet" and a train so long that three-quarters of its length was on the ground.[26]

Although Christine considered such attire unduly ostentatious, her account makes it clear that by the fifteenth century what was formerly a royal and noble prerogative, with connotations closely related to those of the hung bed as furniture of estate, had been appropriated by the upper middle class as a sign of their own rising social status. The gown's excessive fabric in particular conveyed the message of status. Much like poulaines, the extravagantly pointed shoes of the period that served no purpose other than to hinder walking (in extreme instances it was necessary to secure the points by cords to a belt around the waist), the gown, with its voluminous folds, had to be gathered up and held with one hand, thus greatly restricting the wearer's freedom of movement. The purpose behind these conceits of late medieval dress was to emphasize that whoever wore such clothing did not have to engage in any especially strenuous physical activity, let alone do anything that might needlessly be construed as work.[27]

In contrast to Panofsky's familiar interpretation, the wooden clogs or pattens in the lower left corner of the London panel appear to have had a similar function at the time the picture

Figure 49.

Limbourg Brothers, The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine of Alexandria ,

Belles Heures , 1406–9, fol. 17r. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of

Art, The Cloisters Collection (54.1.1).

was painted. Because the room depicted in the double portrait was supposedly hallowed by a sacramental rite, Panofsky saw an analogy between the man's discarded wooden pattens and God's command to Moses from the burning bush to take off his shoes because he stood on holy ground, citing in support the Washington Nativity of Petrus Christus and Hugo van der Goes's Portinari Altarpiece, where presumably Joseph has removed his clogs for the same reason.[28]

Clogs are in fact a quasi-attribute of Saint Joseph in early northern works, and although they have been removed in the pictures Panofsky cites, Joseph wears them in the Adoration of the Magi of Rogier's Columba Altarpiece and in the Nativity of the Bladelin Altar, in the Washington Presentation in the Temple by the Master of the Prado Adoration of the Magi,

Figure 50.

Israhel van Meckenem, The Marriage of the Virgin , 1490–1500.

Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection.

in the Berlin Nativity of Hugo van der Goes, and in many contemporary depictions of the Marriage of the Virgin, for example an engraving by Israhel van Meckenem (Fig. 50).[29] Even donors are shown with clogs in representations of the most sacred scenes of the Christian tradition: in Rogier's Bladelin Nativity and London Pietà, for example. No fifteenth-century viewer can be expected to have considered the ground any less holy in these instances than in the examples mentioned by Panofsky, and if sacramental rites so hallow a place that wearers of pattens ought to remove them, what then of Rogier's Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, where both the godfather holding the child over the font in the baptism scene (Fig. 51) and the bridegroom in the representation of the sacrament of marriage (see Fig. 21) wear pattens?

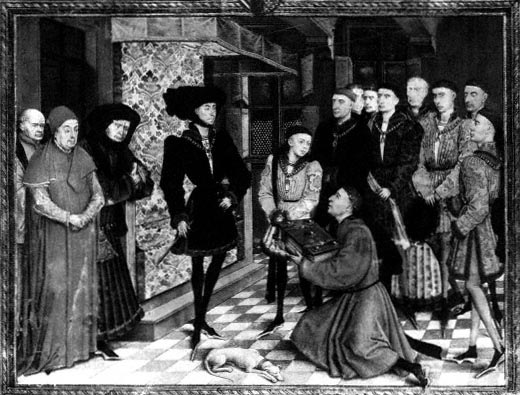

The Arsenal Boccaccio is helpful in understanding what connotation pattens may have had in fifteenth-century Netherlandish society. That only nine of the hundreds of male

Figure 51.

Rogier van der Weyden, The Sacrament of Baptism , detail

from the Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, c. 1448. Antwerp,

Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten.

Photo copyright A.C.L. Brussels.

figures depicted in the manuscript are associated with pattens suggests that their use was not common. In contrast to short, sturdy clogs like those worn by Joseph (in Fig. 50 or the right wing of the Mérode Triptych), which presumably functioned as practical footgear for workers and peasants, the Arsenal manuscript illustrates another type of patten worn by men of the upper class: like the pattens in the London double portrait, these have a narrow, more elongated shape and sometimes extend far beyond the end of the foot. In one miniature (5.5), a man embroiled in street fighting involving swordplay has removed his clogs for greater mobility, and the depiction of Teodoro's betrothal to Violante (see Fig. 31) indicates that what is represented in the Arnolfini double portrait did not in itself provide any rationale for the removal of pattens. A young Neapolitan nobleman, described by Boccaccio (3.6) as blue-blooded and extremely rich, who was about to enjoy (through a complex ruse of mistaken identity) the favors of a certain married lady who had long resisted

Figure 52.

Arsenal Boccaccio (3.6), fol. 116r.

Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

his advances, was portrayed by the Arsenal miniaturist in a large black straw hat and pattens (Fig. 52), suggesting how elegantly attired the man in the London panel must have seemed to the fifteenth-century viewer. It is noteworthy that the outfitting of this figure is an invention of the Arsenal illuminator, for neither the hat nor the pattens are found in the prototype miniature of the Vatican Boccaccio, which in fact contains no illustrations of wooden clogs.[30]

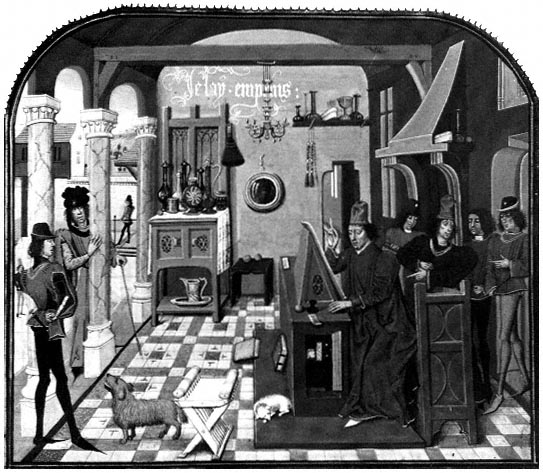

The upper-class fad of wearing pattens seems to stem from a fashion set by the duke of Burgundy himself, in much the same way that Louis XIV's example popularized high-heeled shoes for men in the seventeenth century. Court painters often depict Philip the Good with wooden clogs in formal interior settings, even when he is enthroned in a chair of state; the duke is also known to have had a small portable workshop in which he soldered broken knives, mended glasses, and himself either made or repaired such wooden clogs. After his father's death Charles the Bold destroyed this workshop, and not surprisingly the clogs disappear from Burgundian court manuscripts.[31] But particularly in presentation min-

Figure 53.

Jean Wauquelin presenting his translation of the Chroniques de Hainaut to Philip the Good, Mons,

1448. Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier , ms. 9242, fol. Ir.

iatures made during Philip's lifetime (see Plate II), most notably the famous Chroniques de Hainaut frontispiece group portrait in ms. 9242 of the Bibliothèque Royale in Brussels (Fig. 53), the duke as well as his principal courtiers, including the chancellor Rolin and the duke's heir and successor, the count of Charolais, sport these more refined pattens indoors, where the awkward footgear could have served no practical use. As the occasion depicted is ceremonial and formal, with most of those present also wearing the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece, the clogs are apparently an honorific accoutrement with a value inversely proportional to their cumbersomeness and lack of purpose when worn indoors, although it is amusing to contemplate the clatter that must have accompanied the passage of these courtiers through the ducal residence.[32]

The pattens in the double portrait thus evidently are a footgear of estate, underscoring the status of the male figure, a connotation that apparently lingered on into the sixteenth century, as exemplified by the principal figure in the Invidia vignette of Bosch's Prado Table Top, or the left foreground figure in the January miniature of the Grimani Breviary, who

Figure 54.

Charles the Bold visiting the study of David Aubert. Histoire de Charles Martel , vol. III, Bruges, 1468–70.

Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier ms. 8, fol. 7r.

holds a falcon and wears the collar of some chivalric order. And because a pair of similarly discarded clogs is also found in the same corner of the pictorial space in the Birth of John the Baptist miniature of the Turin-Milan Hours (see Fig. 41)—although it is not so evident in this instance to whom they belong—presumably their removal on entering a house was no more than a matter of convenience.

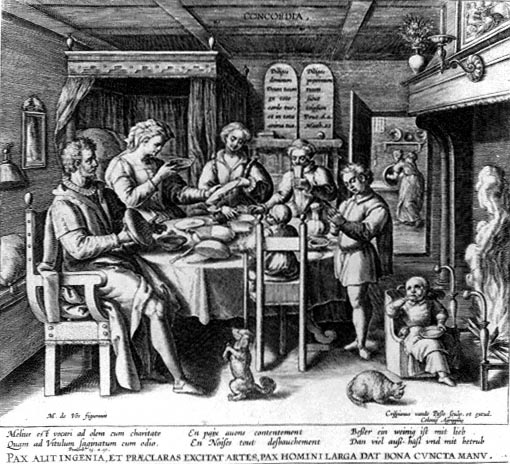

The traditional and conventional nature of the various objects depicted in the Arnolfini double portrait becomes readily apparent in a comparison with two later representations of Netherlandish interiors: a miniature of about 1470 by Loyset Liédet commemorating a visit of Charles the Bold to the study of the romancer David Aubert (Fig. 54) and Crispijn van de Passe the Elder's engraving Concordia, portraying Dutch middle-class domestic harmony

Figure 55.

Crispijn van de Passe the Elder, Concordia , c. 1589. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.

at the end of the sixteenth century (Fig. 55). Although the engraving is separated from the double portrait by a century and a half, the continuity in the objects the two works depict is striking. In both the canopied bed and the father's chair of authority as head of the household are prominent elements in the main room of the house. On the wall next to the bed, the brush and mirror found in the London panel are again to be seen, as is the dog in the foreground, now sharing the household's affection with a cat; and an orange (or at least a piece of fruit) is on the buffet. In Aubert's chamber the buffet with its display of plate replaces the bed and chair as furniture of estate, but other objects familiar from the double portrait are also found in the writer's studio: the mirror, the brush, the rosary hanging on the wall, the chandelier, and the oranges as well as two dogs, and on the shelf and mantel-

piece are various glass vessels similar in form to those that have been routinely interpreted by iconographers as Marian symbols in early Netherlandish paintings.

As these comparisons suggest, the crux of the problem of symbolism (whether disguised or not) in early Netherlandish painting is that symbolic value has been placed on commonplace things that were so much a part of everyday life for several centuries that they reappear continuously in Dutch and Flemish paintings and prints. There is no substantive evidence from the fifteenth century that any of these things were understood symbolically, nothing even comparable to the emblem books of the sixteenth century and later, which are the source of present controversy over meaning in Dutch painting of the seventeenth century. It is also fair to say that save for Meyer Schapiro's mousetrap reading of the Mérode Triptych,[33] none of the many symbolic interpretations advanced during the second half of the twentieth century has enjoyed anything like the consensus that has long supported Panofsky's. The reason is clear: because Panofsky's explanations, even when poorly documented, appear rational or at least plausible, they are intellectually persuasive. Thus it is easier to accept, for example, that Arnolfini has removed his pattens because he is standing on holy ground than to be told that the table in the Mérode Annunciation is an altar or that the towel is a prayer shawl. Although I do not deny that there are symbolic elements in early Netherlandish art, I also do not think that most of the anecdotal details in such works had any symbolic meaning for Van Eyck and his contemporaries. My purpose in what follows is to give a methodological and historiographic critique of three elements in the double portrait that are still widely presumed to have symbolic meaning: the dog, the single candle in the chandelier, and the mirror.

Panofsky's reading of the little terrier as a symbol of "marital faith" is one of his most successful interpretations, for it has acquired a validity quite independent of the London panel, being applied widely and without reference to Panofsky to almost any dog that is associated with a female figure in both earlier and later works.[34] Yet it rests on little more than an undocumented statement that "the dog, seen on so many tombs of ladies, was an accepted emblem of marital faith."[35] The basis for this seems to have been an inference of Emile Mêle with respect to the possible meaning of dogs at the feet of women in thirteenth-century effigy tombs. But Mâle himself went on to recognize that this presumed convention was already breaking down by the fourteenth century, suggesting that such animals might be merely ornamental, and he concluded with the observation that much writing about animal symbolism on tomb sculpture was no more than a "tissu de rêveries."[36]

Both visual and written sources, in fact, indicate that dogs were virtually everywhere in northern Europe during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (see Plate 9 and Figs. 3, 41,

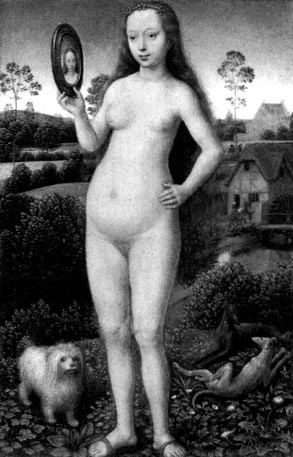

Figure 56.

Hans Memling, Vanitas, c. 1490. Strasbourg, Musée des

Beaux-Arts.

50, 53, 54). If the duke of Berry, who is said to have had 1,500 dogs, seems happy to share his dinner table with two small dogs in the January miniature of the Très Riches Heures, René of Anjou felt compelled to construct a special fence to keep dogs off his bed.[37] Dogs are particularly common in Flemish manuscript illumination, where one or more often fill what would otherwise be an empty area in the foreground of the pictorial field, exactly as in the double portrait, suggesting that a primary function of the animals is compositional.[38] Two dogs are depicted fighting over a bone in a Last Supper miniature in the Hours of Catherine of Cleves,[39] and another dog indifferently witnesses the martyrdom of Saint Ursula in Memling's famous shrine in Bruges. In addition to two greyhounds, a terrier similar in breed to that in the London double portrait accompanies Memling's Vanitas in Strasbourg (Fig. 56), and what could be its sibling attends the same painter's Stuttgart

Bathsheba . Dogs frequently even went to church, as can be seen in Rogier's Seven Sacraments Altarpiece (see Fig. 51) as well as many other works; and, to the consternation of bishops, who waged a futile battle to rid convents of dogs, some nuns were so inseparable from their pets that they took the dogs with them into the choir for the monastic offices.[40] Because they were so common, it would be hard to find anything more antithetical to the out-of-season lily in the iconography of the Annunciation, and thus less likely to have symbolic meaning, than these ubiquitous animals in Franco-Flemish works of the fifteenth century.

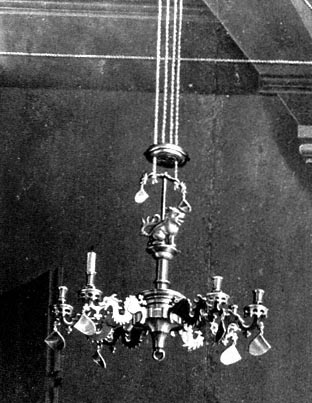

Various explanations, none satisfactory, have been proposed for the chandelier's mysteriously lighted candle. Compounding the enigma, particularly since the subject matter of the two works is so entirely different, a candle also burns for no apparent reason in the daylit chamber of Campin's London Virgin and Child in an Interior (Plate 15). Panofsky's evocative interpretation of the candle in the double portrait as a "symbol of the all-seeing wisdom of God" almost compels intellectual assent and is often repeated as established fact, although in truth it is no more than Panofsky's invention.[41]

Comparative evidence again suggests a very different interpretation for what is seen in the London panel. Chandeliers in other contemporary Netherlandish works are frequently without candles, as in the Last Supper of Dieric Bouts, the Kansas City Petrus Christus (Fig. 40), or the miniature of Aubert's study (see Fig. 54), and many additional examples can be found in Dutch painting as late as the seventeenth century, documenting that the empty chandelier was a commonplace in Netherlandish households for hundreds of years.[42] Sometimes, as in Rogier's Louvre Annunciation (Fig. 57), or in the Turin Virgin and Child (see Plate 12), the chandelier has a single candle, just as in the London double portrait, although it is not lighted, and other candle holders in fifteenth-century works are often either entirely without candles or else have less than a full complement of them, as in the Ghent Altarpiece Annunciation, the Lucca Madonna, or the central panel of the Mérode Triptych, where only one of the two identical fireplace sconces is outfitted with a candle (see Fig. 47; cf. Plate 12).

The explanation is simple and practical: whether made of wax or tallow, candles were expensive in the fifteenth century, and good household management dictated that they should be used as sparingly as possible. Even the price of tallow (which was far less desirable for candles than wax because of its sooty smoke and unpleasant odor) could be four times that of meat; thus an early writer on husbandry recommends that a family retire early rather than waste money on candles.[43] The candles used for a procession in Perugia celebrating Saint Bernardino's canonization in 1450, when later melted down to provide funds for a

Figure 57.

Rogier van der Weyden, detail from The Annunciation ,

c. 1435. Paris, Louvre.

Photo: Musées Nationaux, Paris.

suitable monument to the saint, yielded wax valued at 200 florins.[44] And Giovanni Arnolfini's will, in providing for a requiem mass in his sepulchral chapel annually on the anniversary of his death, specifically limited the lights on the catafalque to four wax candles weighing one pound each,[45] in stark contrast to the many candles burning on the hearse in the Messe des Morts miniature of the Turin-Milan Hours or the corresponding illustration in the Belles Heures . The lighted candle in the double portrait may well have some elusive symbolic meaning that remains to be rediscovered, but the fact that it stands alone in an otherwise empty fixture, so accentuating its enigmatic quality for us, is apparently the consequence of nothing more than good bourgeois thriftiness.

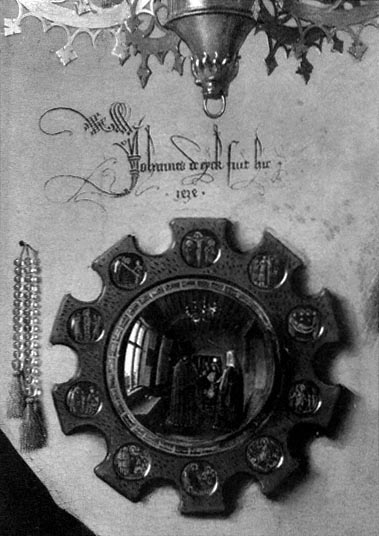

Among the objects depicted in the double portrait, the mirror now shares most closely with the lighted candle this heightened sense of enigma, partly at least because enlarged

Figure 58.

Detail of Plate 1.

photographs of this detail are constantly reproduced (Fig. 58). Because the mirror is also a relative parvenu as a "disguised symbol," how it acquired its present significance makes an interesting chapter in the historiography of the picture's evolving symbolic interpretation.

In Panofsky's original interpretation of the London panel the mirror was so unimportant as to be passed over without notice. But after disguised symbolism was constituted a "principle," some meaning for so prominent an element in the picture had to be found, and accordingly in Early Netherlandish Painting, by way of analogy with the "spotless mirror,"

or "speculum sine macula," of Wisdom 7:26, the mirror became a symbol of "Marian purity."[46] And once canonized by Panofsky's authority, mirrors in other Netherlandish paintings were promptly, if even more dubiously, interpreted in the same way.[47] As tenuous as this proposition was from the beginning—for the mirror in the double portrait is obviously not "spotless"—it goes without saying that any connection between Marian symbolism and a mirror reflecting individuals formalizing the financial arrangements for a future marriage is contextually untenable. What initially gave some measure of credibility to the reading was Van Eyck's known predilection for the Wisdom text, which he took over, together with its application to the Virgin, from liturgical usage, inscribing three of his Madonnas with the passage (it appears as well in the Ghent Altarpiece) extolling her as "the brightness of eternal light and the spotless mirror of God's majesty."[48] Moreover, the speculum sine macula did eventually become a common Marian symbol as an emblem of the Immaculate Conception.

The problem again here is methodological, for the speculum sine macula as an allusion to Marian purity was not current in the 1430s. The meaning of the earlier liturgical imagery—and thus of Van Eyck's inscriptions as well—is that the Virgin herself is a mirror that reflects the majesty of God. Indeed, in Nicolas Froment's Burning Bush of 1476 in Aix-en-Provence, the Virgin and Child have been substituted for God himself in the theophany of the burning bush, and the mirror held by the Child reflects their images. Even as late as about 1480 Bernardinus de Busti makes no mention of the speculum sine macula in his long office for the feast of the Immaculate Conception, approved by—and apparently written at the request of—Sixtus IV (himself a strong advocate of the still controversial doctrine), although Busti's texts, rich in Marian imagery, frequently refer to the Virgins purity and the idea that she was sine macula .[49]

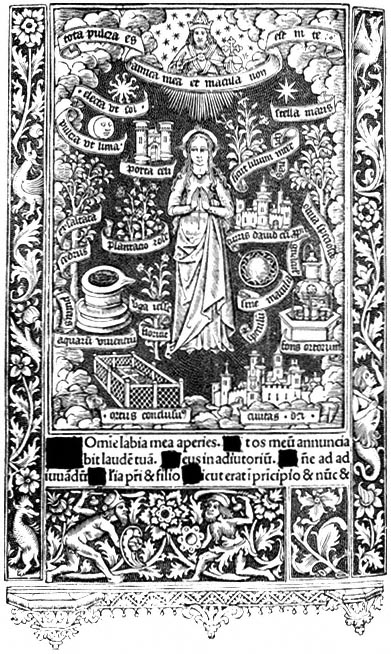

The association of the mirror with the Virgin's purity or sinlessness arose only with a new composite iconography of Marian symbols early in the sixteenth century, as in a Parisian Book of Hours printed by Thielman Kerver in 1505 (Fig. 59). Although some of these symbols, such as stella maris and hortus conclusus, were traditional, others were newly extrapolated from various sources. In the process of accommodating the "spotless mirror of God's majesty" to the new iconography, the last part of the verse was suppressed, significantly changing the traditional meaning as found in Van Eyck's inscriptions. No longer reflecting divine majesty, the mirror now became simply "spotless" or "stainless" and, as a metaphor of being without sin, was appropriated as a symbol of the Immaculate Conception.

Figure 59.

The Virgin with emblems. Heures à l'usage de Rome , Thielman Kerver,

Paris, 1505. San Marino, California, The Huntington Library.

The Litaniae Lauretanae associated with the cult of the Santa Casa of Loreto soon made this imagery a commonplace, but in the first decade of the sixteenth century that was not the case, and hence in early representations these Marian symbols are invariably identified by banderole inscriptions, even in a work such as the Grimani Breviary, which presumably was intended for the use of a theologically learned person.[50] This example shows quite clearly that when symbolic imagery was novel or unfamiliar, even if based on a commonplace text, there was no presumption that the viewer would grasp the intended significance without a written explanation.

What further allegorizes the mirror for many modern writers is the Passion iconography of the miniature roundels that decorate the frame. The presumption is that these images refer to the use of Ephesians 5:22–33 in both Catholic and some Protestant marriage services. The argument might be plausible save for two reasons that effectively undermine its validity. Because a betrothal ceremony, not a marriage, is depicted, text and imagery properly associated with marriage as a sacrament are inappropriate to the circumstances of the couple's action in the London panel. For as previously noted, even when a betrothal was witnessed by a priest, there were normally no prayers. A betrothal was, in short, no more a religious rite in the fifteenth century than an engagement to be married is today. And although Ephesians 5:22–33 became the standard epistle for the nuptial mass in 1570, the normative reading earlier throughout Latin Christendom was taken from I Corinthians 6. Among a handful of exceptions to this general rule over the course of many centuries, the Ephesians 5 lesson does appear in two service books from Reims of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, but only to be replaced subsequently by the conventional reading from I Corinthians. Thus any connection between the liturgical use of Ephesians 5 and the religious imagery of the mirror in the double portrait is unlikely.[51]

The mirror in the London double portrait performs several functions, none of which suggest any need for a symbolic interpretation. The mirror's ordinary function as a looking glass finds confirmation in the Hans Paur woodcut (see Fig. 27), where a convex mirror set in a simple rectangular frame shares a border compartment with a comb and a wooden bathtub. By the fifteenth century mirrors were apparently also valued as costly objects, used primarily for decorative effect. An extreme instance of this use is found in a border miniature of the Vienna Girart de Roussillon from Philip the Good's library, which depicts a convex mirror suspended on a hung bed against the dossier (i.e. the fabric against the back wall). Because one would actually have to stand on the bed to look into this mirror, it cannot have been intended as a looking glass.[52]

The painted roundels decorating the frame of the double portrait mirror would clearly have enhanced its intrinsic value. Their religious content, which doubtless strikes modern viewers as oddly out of place on a seemingly secular object, is nonetheless well within the norms of contemporary convention as part of a long tradition of the moralizing use of mirrors in northern art. The purpose was to diminish thereby the mirror's potential for eliciting vain thoughts. Thus in fifteenth-century miniatures a mirror sometimes reflects a skull, reminding the viewer of death and the corruption of mortal flesh.[53] Similarly, the Crucifixion vignette at the top of the Arnolfini mirror may be compared to an early sixteenth-century woodcut depicting the idealized wise woman as Prudentia (Fig. 60), who, looking into the mirror, sees not her own image but a reflection of the Crucifixion. Often described somewhat inaccurately as a Passion cycle, the ten minuscule medallions embellishing the frame include as well the Harrowing of Hell and the Resurrection, and thus the imagery really epitomizes the central Christian mystery of Christ's triumph over sin and death. In this sense the mirror is a devotional object expressive of middle-class piety, not unlike simple woodcuts (see Plate 12) or small panel paintings that often decorated Netherlandish interiors of the time.

In reflecting the painter's image, the mirror also confirms what the signature above it tells us, namely that "Jan van Eyck was here." But without the inscription even that function of the mirror would remain obscure. By removing both from their context, the modern viewer can easily make more of the inscription and the painter's reflected image than is warranted. The graffito-like signature inscription would not originally have seemed as incongruous as it does today, for manuscript miniatures suggest that mottoes and pious invocations were sometimes actually painted on the interior walls of Flemish houses (see Fig. 54).[54] And even as an artist's signature authenticating a work, the wall inscription of the London panel is comparable to that of Israhel van Meckenem on the altar cloth in his Marriage of the Virgin (see Fig. 50) or, for that matter, to the unusual signature inscription on the Vatican Pietà, which is Michelangelo's only signed work. Instead of indicating an artist's new perception of rising social status in the fifteenth century, these and other similar inscriptions would seem to represent continuity with an earlier medieval tradition, as found in the bold thirteenth-century relief lettering across the base of the south transept portal of the cathedral of Paris identifying Jehan de Chelles as the architect, or the famous inscriptions of Gislebertus on the tympanum of Autun and Giovanni Pisano on the Pisa pulpit.[55]

As for the mirror image of the double portrait, it most closely parallels Van Eyck's painted reflection of himself two years later in the armor of Saint George in the Van der Paele

Figure 60.

Cornelis Anthonisz. (?), The Wise Man and the Wise Woman , early

sixteenth century. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.

Madonna. These images manifest something about the artist's personality that is inherently more playful than profound. And that view of what the painter was like is confirmed by the 1436 inscription on the frame of the Jan de Leeuw portrait, where Van Eyck painted a small heraldic lion following the "Jan de" to complete the sitter's full name (Fig. 61). Rather than enigmatic or cryptic, the meaning of the lion is still humorously transparent, for it is no more than a rebus substituted for the man's surname. The older view—to which Panofsky lent his support—that the inscription on this work constitutes a complex chronograph, is really not credible.[56]

Circumstances peculiar to the twentieth century have helped to form an intellectual environment conducive to the symbolic reading of early Netherlandish works. The influence

Figure 61.

Jan van Eyck, detail of the frame inscription of the Portrait of Jan de Leeuw , 1436. Vienna,

Kunsthistorisches Museum.

of Freud in particular has predisposed us all toward a symbolic view of common things based on free association, especially with respect to the unconscious. It is noteworthy in this regard that in a general reference work like the Encyclopaedia Britannica the earliest notice of Sigmund Freud appeared only in the thirteenth edition of 1926, a quarter century after the publication of Freud's seminal Die Traumdeutung in 1900.[57] The popularization of Freud's ideas by the 1920s thus corresponds in time with Friedländer's symbolic inferences about the double portrait, mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, which in turn prepared the way for Panofsky's tentatively expressed views of 1934 about disguised symbolism in Van Eyck's double portrait: that he would not even dare to assert that the viewer is "expected to realize such notions consciously " (emphasis added). Indeed, the very concept of disguised or hidden symbolism is more akin to the twentieth century than the fifteenth, and iconographic studies based on similarity of form between one object and another owe more to modern psychoanalytic theory than to modes of thought familiar to Van Eyck and his contemporaries.[58]

Complex symbolic readings of Van Eyck's works have also been supported by the modern view, once again fostered by Panofsky's influential remarks, that Van Eyck was a man of wide literary culture and learning.[59] This opinion rests largely on two fifteenth-century texts, only one of which originates with a contemporary who actually knew Van Eyck. In a letter of 1435 Philip the Good reprimanded his financial officers in Lille for their failure to implement an earlier mandate granting Van Eyck an annual pension for life. Because these funds were not being disbursed, Van Eyck had evidently threatened to leave the duke's service, and thus in this letter Philip expresses his apprehension that should this happen, no other painter equally to his taste or "so excellent in his art and science" could be found.[60] The nouns in the phrase "son art et science" apparently refer simply to Van Eyck's skill and

expertise as a painter, which is indeed the context of the passage. And even in modern French, science continues to connote "skill" or "ability." In any case, the duke's vague remark does not justify the view that Van Eyck was learned in a broad general sense.

Bartolomeo Fazio's De viris illustribus contains the earliest extant biographic notice of Van Eyck and provides the second fifteenth-century text adduced in support of the painter's erudition. Written during the 1450s when the Genoese humanist was in the service of Alfonso of Naples, this short account of the artist begins by lauding Van Eyck as "the foremost painter of our time." Fazio continues by saying that Van Eyck was "not unlearned in letters, especially in geometry and those arts which relate to the embellishment of painting," on which account he was thought to have discovered what the ancients knew "about the properties of colors" by reading Pliny and other authors.[61] Phrases like "the embellishment of painting" and the "properties of colors" are characteristic humanistic circumlocutions; precisely what they meant is now difficult to say. Panofsky took the latter to be an "obvious allusion" to Van Eyck's "technical innovations" in painting. Although he may well have been correct, neither he nor any other modern art historian would credit these innovations to Van Eyck's reading of Pliny's Natural History .[62] The point is that Fazio's account is of little value in this regard. And since his brief comments seem to deal only with the technical elements of painting, they do not sustain Panofsky's larger claim that in Fazio's biography Van Eyck "is praised for his scholarly and scientific accomplishments."[63]

The most interesting aspect of Fazio's comment about the painter's intellectual background is the implicit assumption that Van Eyck was enough of a Latinist to have read Pliny's Natural History . Pliny's voluminous encyclopedia was widely used during the High Middle Ages as a source of practical knowledge. It was thus a book that Van Eyck might well have read, provided Fazio's presumption about the painter's proficiency in Latin is correct. As for the actual level of Van Eyck's literary culture, all that can be said with any assurance is that he was familiar with the everyday Latin of his time, but the inscriptions on his works do not in themselves support the idea that his learning was profound. Virtually all these texts are religious and are taken either from the Bible—often via liturgical usage—or from hagiographic sources. The only exception is the banderole inscription of the Erythraean Sibyl in the Ghent Altarpiece, which is derived from Vergil, although it is unlikely to have been based directly on the painter's reading of the Aeneid .

If no complex symbolic reading is superimposed on the anecdotal elements in the double portrait, the painting can be seen as a studied depiction of upper-middle-class affluence: the hung bed and other furniture of estate in the background; the costly chandelier and mirror; the prayer beads of rock crystal; the oranges on the chest and window ledge, which

are known to have been extremely expensive in northern Europe during the fifteenth century;[64] the small carpet near the bed;[65] the opulent vesture of the woman and the fashionable attire of the man, whose discarded clogs also signified status; and finally the woman's little terrier, which Baldass perceptively called the earliest extant portrait of a dog, imbued with "pulsating life" by the artist.[66] It is certainly a pet animal, with no function other than to give pleasure to its owner, who must also have seen in possessing it yet another way to emulate upper-class society, where keeping pet dogs was a common practice by the fourteenth century.[67]

Van Eyck, it has been suggested, attempted the ultimate conceit of an illusionistic painter by denying, in effect, the distinction between the painted image and what it represents, as if to claim that what the viewer sees is not some "fictive image but the real subject of the painter's brush."[68] The objects depicted in a painting by Van Eyck are also key elements in the artist's illusionistic construction of pictorial space, and that is, I believe, their primary function from the painter's point of view. In his multiple-figure compositions Van Eyck first creates the illusion of a central empty interior space by an empirically understood perspectival system.[69] This imaginary, often boxlike, space is then filled with a profusion of objects, each conceived as a real entity with physical extension in all directions. What gives this plasticity to Van Eyck's objects is his astonishing skill as a naturalistic painter combined with his exploitation of the full range of possibilities inherent in the oil medium as he manipulates gradations of color, light, and shadow to enhance the three-dimensional quality of his images.

In the double portrait the various objects have been skillfully and rationally deployed so that from front to back, as well as from top to bottom, the imaginary pictorial space is occupied almost everywhere by some element of these palpably rendered three-dimensional entities or the complex interplay of their cast shadows and reflected highlights. The obliquely disposed foreshortened clogs, the dog, and the train of the woman's gown in the foreground give way to the two central figures, who in turn are succeeded in space by the chest, the oranges, the window and its foreshortened shutters, the carpet, the bed, and the chandelier. The casually placed women's slippers then move the eye into the penultimate plane, where the furniture with its pillow and fabric covering, the rosary, and the mirror are tangible objects that project out into the room and toward the viewer, casting shadows against the rear wall of the room to form a final plane of the pictorial space.[70]

Van Eyck's intentions and even something of the creative process whereby he achieved these remarkable illusionistic effects are discernible from pentimenti that have come to light

Figure 62.

Infrared detail photograph of Plate 1.

by the scientific examination of his works. A major pentimento disclosed by infrared photography of the double portrait (Fig. 62) shows that in rethinking the configuration of Arnolfini's raised right hand, Van Eyck sharply foreshortened it and placed a ring on the first finger. These alterations in no way affect the meaning or significance of the oathswearing gesture, which remains unchanged in its essentials. Visually, however, a relatively flatly rendered hand close to the man's chest has been reworked into a strongly three-dimensional image, thus introducing into the structure of the picture an additional spatial plane between the viewer and the figure itself. The enhanced plasticity of the hand is further accentuated by the ring, with its carefully painted accent of reflected light. By including the ring—which is not present in the underdrawing—Van Eyck departed from his normal practice of omitting, rather than adding, such details in the final execution of a painting.[71]

Similar pentimenti have recently been found in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Annunciation (Plate 16). A cleaning and scientific examination begun in 1988 by Emil Bosshard has revealed that the diptych is not a grisaille painting at all, but a highly naturalistic representation of limestone statues against a polished black marble background, with the figures rendered in a colored palette so as to suggest the structural characteristics of the stone as well as the weathering that might be found in real statues exposed to the elements. Pentimenti indicate that the octagonal plinths on which the statues rest originally began at the bottom edge of the panel, but Van Eyck ultimately repainted the pedestals, extending them out over and actually onto the surface of the frame to enhance the sculptural, three-dimensional effect of the painting.[72] Unlike the similar statues in wings of the Dresden Triptych, where the figures are placed within Van Eyck's most characteristic boxlike spaces, the Thyssen-Bornemisza statues project out from—and seemingly stand in front of—the pictorial plane, thus sharing the viewer's space, casting their shadows back upon the frames. Completing the illusion, Gabriel's head and the entire figure of the Virgin are reflected in the simulated polished stone background in a painterly feat reminiscent of the mirror reflections in the Arnolfini double portrait. Particularly because of their restrained palette, the Thyssen-Bornemisza panels present the viewer with a virtuoso display of the painter's craft and are thus about as close as one can come in the fifteenth century to bravura painting for its own sake.

In a work like the Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, the central perspective of the painting has been opened out to infinity, but in the London panel, with astonishing ingenuity and inventiveness, Van Eyck introduced the convex mirror to create a related but far more original effect. Functioning like a wide-angle lens reflecting an inverted view of much of the interior space of the picture, the mirror also extends a reverse perspectival system out beyond the picture's surface into the space originally, occupied by the painter and his companion, as well as—forever after—by every viewer who stands before this extraordinary work.

If Van Eyck really did read Pliny's Natural History as Fazio suggested, he would doubtless have appreciated the anecdote about the voyage Apelles made to visit Protogenes of Rhodes. Upon arriving at the artist's studio, Apelles found only an elderly woman, who informed him that Protogenes was out and asked who the visitor was. Rather than giving his name, Apelles painted a single colored line of extreme fineness on a sizable panel in the studio and left. When Protogenes returned, he realized at once that only Apelles could have painted so perfect a line. But so as not to be outdone, he painted an even finer line over that of Apelles,

telling the woman to show it to the visitor if he came back again. When Apelles did indeed return to the studio, he was embarrassed by what had happened and in Protogenes' absence proceeded to split the double line already on the panel with a third of yet another color, leaving no room for further display of technical skill. Protogenes thereupon acknowledged his defeat and decided the panel should be preserved, just as it was, for posterity. According to Pliny, this large panel, bearing no more than the three superimposed and almost invisible lines of the two painters, eventually belonged to Augustus and—until it was destroyed by fire in the emperor's Palatine residence—was regarded, especially by artists, as the outstanding work in a collection of important pictures.[73]

In confronting the genius of Van Eyck, we sometimes forget that virtuosity can be so enthralling an experience for performer and audience alike as to become an end in itself. The inscription of the Arnolfini double portrait encourages us to look even more closely at the mirror, which by its distorted reflection draws the viewer further into the picture while at the same time extending our vision out from and beyond the frontal plane of the panel. Van Eyck's technical skill in executing the mirror as a painterly tour de force is further manifested in the ten minuscule medallions that embellish the frame. It was this technical virtuosity that the earliest writers like Fazio, who was especially impressed by a mirror in another of Van Eyck's panels,[74] admired and other painters sought to imitate. And it was in this way that Van Eyck also gave visual expression to his modest—but also proud and confident—motto "Als Ich Can," showing us by his illusionistic description of commonplace objects of the real world what he as a painter could indeed do.