ARE ALLIANCE FORMS A GLOBAL TREND?

The proliferation of complex new forms of strategic alliances in the United States, the European Community, and elsewhere raises the issue of just how different Japanese patterns of intercorporate relations really are, and whether we are not seeing an international movement toward convergence in organizational practice. The popular and business media have been noting this trend since at least the early 1980s, as suggested in the following reports:

1. In the United States, according to Business Week, Silicon Valley has taken the lead in crafting the new rules of competition: "Putting the customer in charge of product design is forging new, tighter relationships between chip suppliers and users. No longer will a sale be just a pact between peddler and purchasing agent; instead, it will require the involvement of engineering staffs and, often, of managements" (May 23, 1983). As part of this "new spirit of cooperation" (January 10, 1983), "Even if they do not acquire each other outright, the various computer, communications, and semiconductor companies may end up aligning themselves through joint ventures, investments, and cooperative deals" (July 11, 1983).

2. In response to international competition, new forms of cooperation have emerged in Europe as well. The New York Times (August 21, 1989) reports, "Governments and companies across Europe are teaming up on a large and fast-growing number of projects aimed at making Europe a more formidable competitor for the United States and Japan."

The scale of these projects is increasingly grand: "France, West Germany, Britain and 10 other nations are building a space shuttle at a cost of $4.8 billion. Airbus Industrie, a four-nation consortium, has become the world's No. 2 passenger aircraft manufacturer, behind Boeing. And Europe's three leading semiconductor companies, Philips of the Netherlands, Siemens of West Germany and SGS-Thomson, a French-Italian joint venture-have teamed up on a $5 billion program that aims to build the world's most advanced computer chips."

3. Similarly, as the Japanese economy moves toward global operations, complex new international alliances are being formed, reshaping the nature of competition in entire industries. A Japan Times article on automobile alliances stated a number of years ago (April 4, 1983): "Trends toward the development of a truly global auto industry demonstrate that Japanese car firms and their U.S. and European counterparts are beginning to recognize that the very survival of the world auto industry depends on cooperative integration of limited resources and technical skills. Faced with meeting energy conservation standards and shifting consumer demands, the auto industry is expected to become streamlined and increasingly interdependent, characterized by shifting alliances and intensified cooperation."

Is Japan, then, at the forefront of a global movement toward complex new forms of cooperation and alliance? A variety of researchers have argued that such a movement is indeed under way, as companies search for solutions to the problems of economic organization that simultaneously avoid the shortcomings of the traditional corporate hierarchy, which introduces a host of different costs related to bureaucratic distortions and inertia, and of arm's-length markets, which fail to adequately protect parties in the kind of complex, information-based exchanges that characterize many contemporary business activities. (See, for example, Piore and Sabel, 1984; Miles and Snow, 1987; Powell, 1987; Johan-son and Mattsson, 1987; Eccles and Crane, 1987; Jorde and Teece, 1990.) If so, this represents a significant trend in the evolution of the industrial structure of advanced societies.

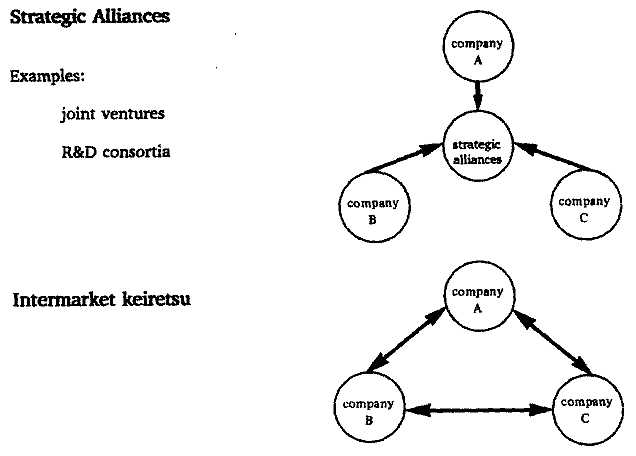

Nevertheless, important differences remain among forms of intercorporate alliance, especially when comparing the strategic alliances characteristic of emergent industries in Silicon Valley and elsewhere with keiretsu relationships among large Japanese enterprises. Strategic alliances create a framework within which companies are able to cooperate in a set of specific business activities, such as the developing of new

technologies. With rare exceptions, however, they do not alter greatly the relationships those companies have directly with each other, their own shareholding structure, or the basic strategic constraints under which they operate.

Japan's major business groups, in contrast, comprise direct and indirect linkages among banks, industrial firms, and commercial enterprises that shape a complex web of interests affecting the company as a whole. They engage a wide variety of activities by opening up sources of capital flows between banks and corporate borrowers, setting a framework for the exchange of raw materials and intermediate product trade, and providing a forum for the informal exchange of information. Most important, they define, through patterns of share crossholding and business-linked equity investment, the underlying ownership structures of their participants-those actors who are assigned ultimate control over the basic decision-making apparatus of the company through the formal mechanisms of corporate control.

This distinction is depicted schematically in Figure 1.2. The strategic alliances that companies craft with competitors and other firms represent a set of focused activities that, while possibly important in the aggregate, do not affect the core integrity of the companies themselves because they are primarily outward-directed and limited in scope. They may be used to help develop new products, exchange technologies, or open up promising markets, but other ongoing business activities among the companies are generally circumscribed and overall corporate strategies are unlikely to be significantly altered.

Not so when a Japanese company's network of ties with its own intermarket keiretsu affiliates is disrupted. Ties to other large manufacturing, trading, and financial firms define basic constraints on the entire corporation: the access it has to capital, the kind of industries it is likely to move into, and the locus of ultimate control over their formal and informal decision-making processes. Should these affiliated enterprises choose, they are able to exercise substantial clout in constraining the management of their members, for they represent a complex nexus of reciprocal interests.

This distinction, of course, is not absolute. Large Japanese companies frequently engage in strategic alliances for technological or market development with the same companies that are their core intermarket affiliates. In this case, their core affiliations help to predetermine the extent of interaction likely to take place among these firms, and this in turn shapes the patterns of cooperation that emerge in the areas of

Fig. 1.2. A Schematic Representation of Strategic Alliances and Intermarket Keiretsu.

business-specific technological and market development. In addition, these firms often take partial equity positions in vertically linked suppliers and distributors that serve business-specific interests for the parent company but represent, in conjunction with high levels of trading dependency, the corporate-wide interests of the supplier or distributor firm.

For this reason, even relatively straightforward distinctions, such as those between vertical and intermarket keiretsu, are rarely this clearly differentiated in practice. Many of the firms constituting the major postwar groupings were themselves at one time vertically linked spin-offs from the zaibatsu. In addition, vertically related firms are often brought into the banking and other relationships that their parent companies maintain with the intermarket groups, indicating that bilateral relationships must be viewed in the context of broader families of relationships.