Heart Failure

The term "heart failure" does not denote the fatal, terminal stage of heart disease but is customarily applied to any state in which the performance of the heart as a pump is significantly impaired. Heart failure means to the physician a set of symptoms and signs appearing in a patient whose heart is incapable of maintaining adequate circulatory function for supplying body tissues with oxygen under all circumstances. Such conditions may exist temporarily or permanently.

The left ventricle, which supports all tissues and organs with the exception of the lungs, is the principal area of the heart affected by cardiac disease. When functioning normally, it is capable of ejecting the needed amount of blood into the aorta with a normal filling pressure (less than 10 mm Hg). Impaired function of the left ventricle is present if the cardiac output (quantity of blood ejected) is less than normal or if higher diastolic filling pressure is required for ejecting blood. Since the left ventricular pressure is identical to the left atrial pressure during diastole, significant elevation of pressure in the left atrium and left ventricle during diastole acts as a dam, which has to be overcome by higher pressure in the veins, capillaries, and arteries of the lungs. Furthermore, the amount of blood in the lungs increases. This phenomenon is usually referred to as pulmonary congestion; the patient may sense stiffness in the lungs during respiration and experience shortness of breath (dyspnea ). Rarely, if the malfunction of the contractile properties of the left ventricle develops abruptly, the capillaries of the lungs may permit an excess of fluid to enter the lungs, producing pulmonary edema , a life-threatening variety of dyspnea associated with coughing up frothy, bloody sputum.

The chain of events initiated by reduced performance of the left

ventricle begins during activities. A patient in the earliest stages of heart failure is able to perform ordinary activities but becomes short of breath during strenuous exercise he or she previously tolerated. Further deterioration of ventricular function causes dyspnea in response to less-demanding activities. Eventually the tolerance of activities may become very limited, and dyspnea may appear without provocation, often at night.

The other effect of left ventricular malfunction, reduced cardiac output, may be compensated for by tissues extracting more oxygen from the blood, thus encroaching on the reserve. However, one organ in the body is especially sensitive to a reduced blood supply—the kidneys, the function of which includes regulating the amount of salt and water in the body. They require a generous blood supply; even a modest reduction of blood flow through the kidneys may set in motion a mechanism involving certain hormones, which causes retention of salt and water.

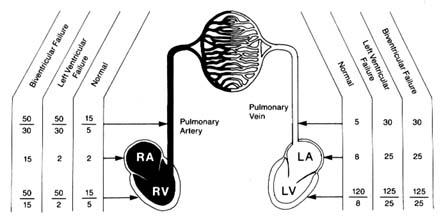

In most cases of heart failure both increased filling pressure and reduced cardiac output take place. High pressure accounts for most of the symptoms, including dyspnea, and produces much of the disability. Furthermore, high pressure in the pulmonary circulation may overload the right ventricle to a point where it begins to malfunction. If this happens, high filling pressure in the right ventricle dams up the venous circulation returning the blood to the heart from the tissues. This impairment in circulation may produce enlargement of the liver and greatly increases the chance of fluid retention, leading not only to more-pronounced swelling of the lower extremities but also to accumulation of fluid in the chest cavity (pleural effusion ) and the abdominal cavity (ascites ). The lowered oxygen content of the blood in the tissues and the slowing of the circulation may become visible through the vessels, giving the skin or lips a bluish tint (cyanosis ). Heart failure involving both ventricles is referred to as congestive heart failure. When this is present, the patient may experience severe weakness accompanying or replacing dyspnea. Sample pressure changes in heart failure are shown in figure 22.

Patients' response to heart failure varies widely. The two principal consequences of it are dyspnea and fluid retention. Dyspnea usually develops only in response to physical activity in the early stages of heart failure. The discomfort related to shortness of breath

Figure 22. Examples of pressure changes in the heart and pulmonary circulation

in left ventricular failure and in combined left and right ventricular failure.

during exercise can be avoided by reducing strenuous activity. Many patients do so intuitively and cease the activity before dyspnea appears; sometimes they are even unaware of their reduced tolerance for exercise, particularly if heart failure progresses very gradually. In most cases, however, patients become aware that activities hitherto easily performed can no longer be tolerated because of dyspnea, which leads them to seek medical care. In later stages dyspnea not only may appear without physical activity but also may be provoked by lying down, so that patients may have to sleep propped up in a half-sitting position (orthopnea ) or may awaken at night from attacks of dyspnea or cough.

It should be emphasized that dyspnea is not specific to cardiac disease with heart failure but may also be produced by other conditions: a variety of diseases of the lungs, including pneumonia, emphysema, and tumors; spasm of the bronchi, such as occur during attacks of asthma; and accumulation of fluid in the pleural cavity. It may also develop in response to certain signals from the central nervous system, such as a reaction to anxiety.

Fluid retention manifests itself most frequently in swelling (edema ) of the ankles, where fluid accumulates under the skin. More pronounced fluid retention shows up in the pleural and abdominal cavities and may cause considerable discomfort to the patient. However, heart failure is only one of several causes of edema.

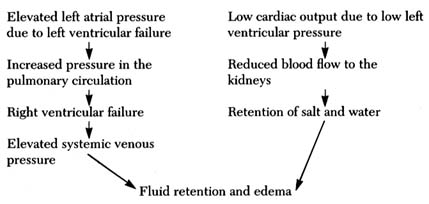

Figure 23. Two alternate mechanisms producing fluid retention and edema in heart failure.

There are three mechanisms involved in the accumulation of fluid (generally or locally): (1) mechanical , when pressure in the veins draining the legs or other areas is abnormally high; (2) hormonal , when the hormonal balance regulating salt and water is upset, such as occurs in reduced blood flow due to heart failure or in kidney disease; and (3) osmotic , when the protein content of the blood serum falls below a critical level, causing fluid to leave the capillary blood vessels. In heart failure, fluid retention in general and edema in particular are caused by mechanical and hormonal factors, as shown in figure 23. It should be noted, however, that abnormalities other than heart failure may also be responsible for edema: for example, edema of the lower extremities may result from an obstruction in the veins interfering with the return of blood from the legs.

Heart failure may develop abruptly (acute heart failure) or gradually, over a period of weeks, months, or years. The mechanisms of acute heart failure differ in patients with a previously healthy heart and circulation and those who already suffer from chronic heart disease. The former type involves a sudden severe injury, or insult, which cannot be compensated for by the cardiac reserve and its adaptive mechanism. It includes sudden overload of the heart or acute damage to the heart muscle. Left ventricular failure may develop after acute damage to one of the left cardiac valves (mitral or aortic regurgitation caused by an infection or trauma) or to the

heart muscle (as in myocardial infarction). Right ventricular failure may result from increased pressure in the pulmonary artery caused by a large thrombus (clot) traveling to the lung and obstructing the flow of blood. Acute heart failure in patients who suffer from a chronic cardiac illness but are able to lead a normal or near-normal life is almost always preceded by some event affecting the heart or circulation: cardiac arrhythmia, as the onset of atrial fibrillation; new damage to the heart muscle, such as an acute coronary episode; or problems affecting the patient as a whole, such as infection, trauma, surgery, and failure of a major organ (kidney, liver, etc.).

Chronic cardiac failure is usually the end result of prolonged heart disease producing either persistent cardiac overload or damage to the heart muscle. Common causes of chronic overload include severe hypertension, valvular heart disease, and congenital cardiac malformations. Causes of myocardial disease include coronary-artery disease and cardiomyopathy.

As a rule, gradual development of heart disease is characterized by long periods during which the patient may lead a normal, unrestricted life. Deteriorating function of the heart may only be detectable by special tests, such as echocardiography or radionuclide studies. Disabling symptoms, particularly dyspnea, may progress very slowly: it is often difficult to pinpoint the onset of heart failure. The great majority of patients with heart failure—in both its acute and chronic varieties—responds to treatment, which can reduce or even totally eliminate disability. Depending on the nature and severity of cardiac disease, successful medical or surgical therapy of heart failure can prolong life or at least make life more tolerable.