I

Hecataeus, His Work, and the Jewish Excursus

Before turning to examine the treatise On the Jews , it would be of advantage to introduce the man Hecataeus, his life and literary work, the genre he specialized in, and, especially, his Jewish excursus. This may help to place the treatise in the right perspective and make it easier to follow arguments and considerations that will be raised in the course of the discussion. The following survey will not try to exhaust all the material and questions involved but will present only information relevant to the subject of this monograph.

1. The Man, the Ethnographic Genre, and Hecataeus's Egyptian Ethnography

Our knowledge about Hecataeus's life is rather patchy. From the few testimonia, the following résumé can be drawn:[1] Hecataeus was born in Abdera, a prosperous Greek colony on the Thracian coast, around the middle of the fourth century. He reached maturity, and perhaps already had some reputation, by the time of Alexander the Great. In these years he seems to have received good philosophical training. In

[1] See E. Schwartz (1885); Jacoby, RE s.v. "Hekataios (4)", 2750-51; id . (1943) 30-34; Guttman (1958-63) I.40-41; Murray (1970) 144-45; Sterling (1992) 59-61, 74. The testimonia are collected in FGrH IIIA 264 T 1-9. The most detailed and explicit information is to be found in the introductory notes of Josephus to the quotations from On the Jews and in the extracts themselves (Ap . I.183, 189, 201). This information is corroborated by circumstantial evidence scattered in other testimonia.

the period of the Successors Hecataeus was occupied in the service of Ptolemy I. His precise position in the court was not recorded. It can only be said that he was close to the satrap-king, took part in military expeditions, and went on diplomatic missions abroad.[2] At least one of his works, the Egyptian ethnography, served, in its special way, political goals of Ptolemy I.[3]

The ancient sources describe Hecataeus as a "philosopher" and critical grammatikos , and refer to his ethnographical works as "history."[4] Diogenes Laertius, the biographer-compiler of the Greek philosophers, lists Hecataeus among the people who were taught by Pyrrho and includes him among the "Pyrrhoneans" (IX.69). However, it is doubtful whether Hecataeus was indeed Pyrrho's disciple, or that he adhered to his teaching.[5] Another testimonium mentions him as one of the

[2] The accepted reconstruction of Hecataeus's life was challenged by Diamond (1974) 117, 139-44, who suggests that Hecataeus was a wandering sophist who lived on the Greek mainland. The one argument worthy of attention is that if the treatise On the Jews is a forgery, the information provided there on Hecataeus must also be discounted. However, the treatise was written, in any case, in Ptolemaic Egypt. To describe a sophist who resided in Greece as a prominent figure in the Ptolemaic court would have discredited the author at the outset. The biography of the author who wrote the celebrated Egyptian ethnography must have been known to local intellectuals in Ptolemaic Egypt. Moreover, Josephus's introductory biographical notes do not seem to be based on the treatise itself, but on another source. And as was said in the preceding note, the testimonia of Against Apion do not stand alone. See also Sterling (1992) 74 n. 81.

[3] See pp. 16-17 below.

[4] See FGrH IIIA 264 T 1, 4, 7, 8.

"Abderites," between Democritus and Apollodorus of Cyzicus (Clem. Strom . II.130.4), which inspired some speculations about Hecataeus's philosophical conceptions.[6] No name of a philosophical work by him is known, but there is little doubt that he indeed wrote philosophical works.[7] The situation with his contribution as a "grammarian" is not much different: we know that he wrote two books, on Homer and Hesiod (Suda , s.v.

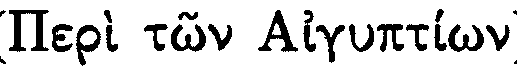

Hecataeus's major contribution was his ethnographical work. It was called history because in antiquity there was no generic name for this sort of writing, and it was included in the framework of history.[8] We know of two monographs: an Egyptian ethnography named On the Egyptians (

[6] See Reinhardt (1921); Jacoby (1943) 31; Spoerri (1959) 6-30, 164ff.; Cole (1967) 77ff.

[7] See Jacoby, RE s.v. "Hekataios (4)," 2753-54; id . (1943) 32. The testimonia in FGrH no. 264, T 3b and 9, could hardly have been taken from Hecataeus's philological or ethnographical works.

[8] See Fornara (1983) 1-2.

[9] On the Egyptians was preferred by Jacoby, FGrH IIIA 264, p. 12; id . (1943) 75ff.; Murray (1970) 142, 150; Fraser (1972) I.496. Others have suggested Aegyptiaca : Wachsmuth (1895) 330; Trüdinger (1918) 50; Burton (1972) 5. Both suggestions are based on known titles of other ethnographic works (and Hecataeus's second book), but direct evidence is lacking. Diod. I.4.6 ("Egyptian Histories") refers also to many other works, all being classified according to their generic name.

[10] See Jacoby (1943) 37-38; Murray (1970) 150, 166-69; id . (1972) 207; Fraser (1972) I.497.

later ethnographic accounts on the Jews.[11] In order to understand the importance of Hecataeus as an ethnographer, we have to preface here a brief survey of the genre.[12]

Although it did not have a generic name, there is no doubt that Greek ethnographical writing was a genre in its own right, with definite structure, rules, and purposes. Its beginning in the sixth century is connected with Greek colonization and the advance of the Persian empire, which raised the interest of the Hellenes in the surrounding world. Hecataeus of Miletus is regarded as the father of ethnography. His Periegesis , a geographical tour or survey around the Mediterranean, included a number of geographical accounts of the peoples of these countries. It seems that ethnographical writing at that time was not limited to excursuses in works belonging to other genres. There is some information about monographs by Hellanicus of Lesbos and Charon of Lampsacus that may have been predominantly ethnographic.[13]

The features of the new genre can be defined according to the ethnographical excursuses of Herodotus, especially the comprehensive accounts on the Egyptians and the Scythians. They were composed of the following sections:[14] (a) origo-archaeologia , the beginning of the nation; (b) geography; (c) customs; and (d) history. The origo-archaeologia described the descent of the people concerned either from their autochthonous beginnings or with their migration, and their early life as a nation. The geography referred to borders, rivers, fertility of soil, flora, and fauna, and elaborated on, among other things, thaumasia (marvels and curiosities). The customs section was the most important, and was designed to present the main features of the nation. Attention was given to beliefs and cult, social structure, institutions, and everyday practices. The last section, history, included mainly dynastic records with stories of the major achievements of outstanding rulers, usually concerning monumental buildings and successful military expeditions.

[11] See below, pp. 211ff.

[12] On the ethnographic genre, see Jacoby (1909) 4ff.; Trüdinger (1918); Dihle (1961); K. E. Müller (1972-80); Fornara (1983) 1-15; Sterling (1992) 20-102.

[13] See Sterling (1992) 32-33.

[14] See the detailed discussion, pp. 192ff. below.

The ethnography of the classical period can be described as nonscientific, resembling Herodotus's historiographical methods: unselective accumulation of material, without an attempt to arrive at the factual truth. There is no causal connection between the various sections of the ethnography or between the details in each section, and there is no reasoning to the mass of material. The sources of information were personal impressions of the author (who in some cases visited the countries described and interviewed local people), together with rumors and hearsay, tourist reports, and references in previous Greek literature. No use was made, directly or indirectly, of the literature or written records of foreign nations.

The first ethnographers did not write their works in the service of rulers or cities. They were, by and large, travelers, amateur geographers, seamen, merchants, or historians who had a keen interest in foreign countries and their inhabitants, and wrote at leisure. Their geographical horizon was limited to neighboring countries and the main divisions of the Persian empire. No clear ideology or pragmatic purpose is visible in these accounts. It can be said that they were basically written to satisfy the curiosity of Greeks who came across foreigners or heard about them. The rise of the genre just at the end of the age of colonization and the rather general character of the accounts rule out the possibility that Greek ethnography was initially meant as a guide to planned colonizations. In the case of excursuses incorporated in works belonging to another genre such as history or geography, the ethnographical accounts were introduced as a necessary preface to historical events or geographical descriptions relating to the nation concerned. They also had a literary role—to diversify the writing and provide some relief in the course of a long and monotonous narrative.

A new impetus in the development of the ethnographical genre naturally arose with the conquests of Alexander and Greco-Macedonian settlement in the newly occupied countries.[15] Interest in foreign nations grew immensely, and increased knowledge carried with it practical implications. The authors were no longer residents of the old Greek world, and in many cases lived in the countries they described. They could, therefore, consult local written sources, thoroughly interview people of

[15] See Jacoby (1909) 90-92; Trüdinger (1918) 64ff.; Dihle (1961) 207-39, esp. 207-13; Murray (1972) 207; Sterling (1992) 55ff.; cf. Spoerri (1961) 63ff.; Cole (1967) 25ff.

all ranks of society, and gain firsthand acquaintance and understanding of the subjects referred to. Unlike their predecessors, Hellenistic ethnographers were personally involved with their subject, had definite didactic purposes in presenting their material, and frequently served Greco-Macedonian rulers. Consequently the new writing was no longer a casual accumulation of material arranged into schematized thematic rubrics: its information was carefully selected to fit with Greek literary models, or with premeditated political purposes or philosophical conceptions, or both. The information was not left unprocessed: it received some Greek touches and coloring, and reasoning was provided for the facts. The explanations often disclose the purposes of the writers; in other cases they were just borrowed from Greek tradition. As a result of all these, the final picture may have deviated considerably from the historical truth. By and large, the genre can be described as an interpretatio Graeca of the Orient. The more an author adhered to premeditated purposes, the more he departed from the original information. In some cases the outcome was an odd mixture of realism with sheer fantasy.

As far as the structure is concerned, there was no change in the basic scheme of ethnographical works: the same sections appear in Hellenistic ethnographical monographs and excursuses as in their classical counterparts, although in certain cases one or two sections may be missing. However, in contrast to the old ethnography, the various sections did not remain isolated from each other. Authors stress the causal connection between them: customs result from the special circumstances and conditions of the origo, or the geography, or both; and history arises from all these. The various subjects in each section are also connected by causal reasoning. As a result, there is more flexibility in the order and sequence of the traditional four sections of the ethnographical work.

The philosophical and political character prevailing in many works of the new ethnography motivated the rise of a subgenre, the utopian ethnography. Utopian features in Greek literature were as old as Homer, and were integrated in various genres.[16] Undertaking to describe remote or legendary peoples, utopian ethnographies were planned and constructed according to the rules of Hellenistic ethnography; but the material was entirely fictitious, designed to illustrate an ideal, nonexistent society. The best-known example is Euhemerus's utopia about the

[16] On Greek utopian writing, see Ferguson (1975).

Panchaeans, set on an imaginary island in the Indian Ocean. It included the celebrated Euhemerist religious conception, according to which the gods were actually deified kings and heroes of the past. Less well known is that this idea was expressed earlier by Hecataeus of Abdera with regard to "terrestrial" gods in his Egyptian ethnography (Diod. I.13ff.).[17]

We can now turn again to Hecataeus of Abdera.[18] The general scheme of his works will be discussed below in Chapter VI.3.[19] It will be shown that Hecataeus followed the basic scheme of his Greek predecessors. However, apart from this structural similarity, all other features differed substantially, marking a new phase in the development of the genre. There is an obvious expansion of scope. Hecataeus increased the sources of information, the geographical horizon, and the types of the genre, and expanded its literary framework. He consulted, directly or indirectly, old Egyptian writings (Diod. 1.69.7, 96.2) and had access to a variety of oral sources. He wrote two comprehensive monographs, one on the Egyptians, the other on the Hyperboreans. The first described the nation among whom he was residing; the second, legendary people imagined to live on the northern outskirts of the inhabited world. The first work was an idealized version of Egyptian history, institutions, and way of life; the second, an imaginary utopia. In addition to monographs, Hecataeus wrote miniature ethnographies of nations believed to have originated from Egypt. These were incorporated as excursuses in the Egyptian ethnography. The nations described were neighboring peoples such as the Jews, or the Babylonians (whose country was then the center of the rising Seleucid empire), and even Hellenic tribes or cities, such as Athens (Diod. I.28-29).

The great contributions of Hecataeus, however, to the development of the genre were the selection of material according to Greek literary and ideological conceptions, the creation of a causal connection between

[17] On the influence of Hecataeus on Euhemerus, and the chronological question, see Jacoby, RE s.v. "Hekataios (4)," 2763; Nilsson (1961) II.285-86; Cole (1967) 153-58; Murray (1970) 151; Drews (1973) 206 n. 162; and Oden (1978) 118-19 for further bibliography.

[18] On Hecataeus as an ethnographer, see Jacoby, RE s.v. "Hekataios (4)," 2755ff.; Guttman (1958-63) I.42ff.; Murray (1970); Fraser (1972) I.496-505; Mendels (1988); Sterling (1992) 61-78.

[19] Pp. 192-219 below.

the sections of the work and between the subjects within each section, and the reasoning provided for many statements. Thus, for instance, in the case of an emigrating nation, its experiences in the country of origin and the circumstances of its emigration would influence its everyday life, institutions, language, and attitude toward other nations. The life, history, and character of autochthonous peoples would be dictated, to a great extent, by geography, especially soil, water, climate, and fauna. Cult and beliefs, which were referred to without comment by earlier ethnographers, received rational explanations. Even the notorious Egyptian animal cult was given a detailed rationalization, pointing out the benefits brought by the animals to the Egyptians (Diod. I.86ff.). The like applies to other subjects. The reasoning often drew on Greek experience and thinking. In this respect Hecataeus's ethnography may appear to strive for scientific presentation, but the selection of the material, its coloring, and its reasoning were not necessarily guided by a wish to record absolute historical truth.

This loss to political history and ethnography was a gain for the history of ideas. It would be rather speculative to reconstruct the utopian model envisaged by Hecataeus in his Hyperborean ethnography. The scant surviving material allows only a few conclusions with regard to Hecataeus's religious stance. He seems to have adhered to the traditional cult of classical Greece and was evidently highly tolerant.

The state of preservation of the Egyptian ethnography is much better Apart from some fragments and testimonia,[20] its contents are to be found in Book I of Diodorus's Historical Library , which is devoted to Egyptian ethnography. Following the studies of Eduard Schwartz and Felix Jacoby it has been accepted that Book I of Diodorus (from I.10 onward) is basically an abbreviated paraphrase of Hecataeus's Egyptian ethnography, though it also contains a long section taken from Agatharcides of Cnidus (the description of the Nile, I.32-41) as well as notes and additions by Diodorus himself.[21] This conclusion has been challenged from time to time; arguments have been raised against the attribution of certain passages to Hecataeus, and there have also

[20] See FGrH IIIA 264 F1-6.

[21] See E. Schwartz (1885) 223-62, following Schneider (1880); Leopoldi (1892); Schwartz, RE s.v. "Diodorus," 669-72; Reinhardt (1921); Jacoby, RE s.v. "Hekataios (4)," 2759-60; id . (1943) 75-76; cf. Fraser (1972) I.497-509, II.1116; J. Hornblower (1981) 23ff.

been those who have tried to minimize Hecataeus's share in Diodorus's version.[22] These attempts have been rightly refuted, and one has to note especially the contribution of Oswyn Murray, who reestablished the old, accepted theory.[23]

The dating of Hecataeus's Egyptian ethnography has been disputed. While some have suggested the early years of Ptolemy's independent satrapy (320-315) others have preferred the first years of his monarchy (306/5-300).[24] The arguments in favor of the first possibility are not decisive. On the other hand the year 306/5 as a terminus post quem appears from the introduction to the account of the borders of Egypt (Diod. I.30.1):

Egypt lies mainly toward the south, and, in natural strength and beauty of land, seems to excel those places that have been separated off [each] into a kingdom.

A comparison is obviously being made with the regions occupied by the other satraps who declared themselves kings after the naval battle of Cyprian Salamis in 306. Given the general context, an account of pharaonic Egypt, the sentence seems to have been written by a contemporary of the Successors, and certainly not by Diodorus, in the days of Augustus. It stands in fact at the head of two definitely Hecataean chapters (30-31.8),[25] and this would appear to clinch the argument. The year 302/1 (not 300) as terminus ante quem is suggested by the unbiased attitude toward Jews and Judaism manifested in the Jewish excursus incorporated in the Egyptian ethnography:[26] after the confrontation between Ptolemy I and the Jews in that year, the subsequent harsh treatment of the population, the banishment of scores

[22] See Spoerri (1959), and esp. Burton (1972) 1-34. Cf. Sacks (1990) 206.

[23] See Murray (1970) 145, 148-49, 151-52, 164, 168-70; id . (1972) 207ff. Murray's articles actually answer many of the arguments raised by Burton, although Burton's book appeared two years later. Cf. Murray (1975) 287-90; Lloyd (1974) 287-88; Griffiths (1976) 122. See also Gigon (1961) 771ff. on Spoerri's book. See further, on Burton's and Sacks's arguments, Extended Notes, n. 1 p. 289.

[24] See M. Stern (1973), Murray (1973), with references there to earlier literature.

[25] Diod. 1.30-31.8 was taken from Hecataeus; see p. 196 below.

[26] See pp. 22, 208-11 below on the original place of the excursus.

of thousands to Egypt, and the sale of many into slavery,[27] a positive account of the Jews without any reference to these developments is hardly to be expected of an author serving in the court.

The very writing of the work and its main message were dictated by the circumstances of the hour: the official end of provincial rule and the establishment of new kingdoms in oriental countries with long monarchic traditions. Ptolemy saw himself as the successor of the pharaohs, a legitimate king of the Egyptians. The predominant feature of the Egyptian ethnography was, therefore, the glorification of Egypt. The country is described as the land of human origins, the cradle of civilization, and of wisdom. Useful inventions such as fire, agriculture, language, and writing, as well as most of the arts, originated on Egyptian soil (I.13ff., 69.5-6). Many nations came from Egypt and were deeply influenced by its culture. The most outstanding of these were the Greeks (including the Athenians) and the Babylonians (I.28-29). Mythical cult figures, lawgivers, poets, and philosophers, such as Orpheus, Musaeus, Solon, Lycurgus, Homer, Protagoras, Democritus, and Plato, visited Egypt, explored its laws and institutions, and drew substantially from them (I.69.3-4, 96ff.). Pharaonic rule appears as a law-abiding monarchy, guided by priests, with the king maintaining virtues like justice, magnanimity, and piety (I.70-71, 73.4). The Egyptian judicial system and its procedures are said to have been planned in a way that facilitated reaching the absolute truth with the utmost objectivity (I.75ff.). Egyptian gods are equated with Greek ones and rationalized: two are explained as representing the great celestial bodies; five others, the basic elements (fire, spirit, etc.); and the rest, renowned mortal heroes and inventors of the past. The rehabilitation of practices deplored by Greeks included not only animal cult (I.86-90) but also incest (I.27.1-2). These were toned down and given rational explanations that made them acceptable to Greek ears.

The tribute paid to the greatness of Egypt was meant to help in establishing the image of the Ptolemaic regime. It raised the prestige of Ptolemy, the new king of this great, old civilization, in the eyes of Greco-Macedonians living under other Hellenistic rulers. This in turn helped to attract to Egypt competent European manpower and the intellectual elite of the Greek world. As for the Greco-Macedonians settled in

[27] On these events, see pp. 74-77 below.

Egypt, the enthusiastic account of the pharaonic past brought home the royal policy of respecting Egyptian traditions, including superstitions, in order to avoid ugly confrontations with the natives and their strong priesthood.[28] It has been suggested that the work was also intended to flatter the Egyptians themselves. This is quite doubtful: the language barrier was still too high at the end of the fourth century to expect the book to circulate among Egyptians, let alone influence them. Moreover, the glorification of the pharaonic past could have sparked off Egyptian nationalism, and the recurring references to the role of the priests as advisers of the king would only have encouraged the Egyptian priests not to be content with their religious duties. Other suggestions offered for the purpose of the book, such as to establish a general model of government and society for the developing Hellenistic world, or to present an idealized version of the Ptolemaic regime, do not stand up to criticism.[29] The role of the priests is not the only feature refuting these suggestions. Various points in the book have evident didactic purposes, but they do not carry its main message.

It would take us far afield to refer to every thematic aspect of this fascinating ethnography. It is a mine of theological, philosophical, political, and social ideas. I shall restrict myself to noting a number of points that have some relevance to an understanding of the Jewish excursus:

1. The information is based by and large on Egyptian priestly oral and written sources.[30]

2. In certain cases it reflects not historical facts but ideals circulating among those priests.[31]

[28] For the dangers involved in not respecting Egyptian superstitions like the killing of a cat, see, e.g., the later incident related in Diod. I.83.6-8.

[29] For the various suggestions for the point of the work, see E. Schwartz (1885) 233-62; Wendland (1912) 116-19; Jacoby, RE s.v. "Hekataios (4)," 2757-63; Meyer (1928) 529ff.; Jaeger (1938) 140, (1938a) 151ff.; Welles (1949) 39-44; Kienitz (1953) 49ff.; Guttman (1958-63) I.45ff.; Murray (9170) 150-69; Fraser (1972) 1.497-505; Drews (1973) 126-32, 205 n. 157; Mendels (1988) 15-16; Sterling (1992) 73-75.

[30] Diod. I.21.1, 26.1, 43.6, 69.7, 86.2, 96.2; and see Murray (1970) 143 n. 2, 151 n. 1.

[31] ee Murray (1970) 152-61 with regard to the account of pharaonic kingship. Cf. Burton (1972) 209ff.

3. The interpretation of the facts is Hecataean, and is inspired by Greek tradition and modes of thinking, apart from a few cases where the author explicitly says that an explanation is Egyptian.

4. The interpretation is frequently complimentary, and apologetic in some cases. It includes explicit expressions of praise. The tendency to idealize is evident.

5. The author himself divides the customs recorded in the book into two categories: "extremely strange [paradoxotata ] customs," and those that might be "most useful" to the reader (I.69.2; cf. 30.4). He introduces customs of the first type in order to provide reasoning for well-known curiosities and to arouse interest in others. The "useful" customs are brought in to serve as models for imitation, to point out their superiority over existing Greek practices, or just for the sake of comparison.[32]

6. Despite his desire to present an appealing, favorable picture of Egyptian life, Hecataeus does not refrain from expressing reservations about Egyptian hostility toward strangers, although he tries to "soften" it (Diod. I.67.10-11, 69.4, 88.5)

2. The Jewish Excursus

Hecataeus's Jewish excursus was much discussed in the last century. Being actually the first comprehensive account of Jews and Judaism in Greek literature, it was used by later gentile authors as a basic source of information on the subject. Some features of this account, especially the attribution to Moses of the settlement in Judea and the establishment of basic Jewish institutions and practices, became a vulgate in Greco-Roman literature.[33] In the present monograph, a review of the excursus and its problems is relevant not only to the question of the authenticity of On the Jews , but also to the shaping of one of its sections. Be that treatise a forgery or not, its author was certainly acquainted with the excursus.

Like his major works, Hecataeus's original ethnographic account on Jews and Judaism has not been preserved. Diodorus incorporated an abbreviated paraphrase of it in Book XL of the Historical Library

[32] An evident model: Diod. 1.73.7-9 (see pp. 37-38 below). Explicit criticism of Greek customs, I.74.6-7, 76; comparisons, I.29.

[33] See pp. 211-17 below.

(3.1-8), which is itself now lost, but his version of Hecataeus's Jewish ethnography is preserved by Photius, the Byzantine patriarch of the ninth century. Photius attacks Diodorus for "telling lies" about the Jews. To illustrate this accusation, he cites two extracts. The first is a story about the siege of Jerusalem by Antiochus VII Sidetes (in 134 or 132 B.C. ) and the anti-Jewish libels and accusations voiced on that occasion by the king's advisers (cod. 244, 379a-380a = Diod. XXXIV-XXXV.1.1-5). Then comes the Jewish ethnography. The text of Photius runs as follows (cod. 244, 380a-381a):

From the fortieth book [of Diodorus], about the middle:[34]

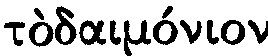

[3.1] Now that we intend to record the war against the Jews, we consider it appropriate to give first an outline [

] of the foundation [ktisis ] from its beginning, and of the customs [nomima ] practiced among them.

When in ancient times a pestilence arose in Egypt, the ordinary people ascribed their troubles to the working of a divine power [

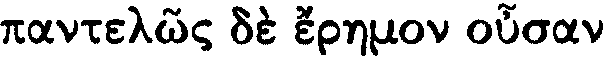

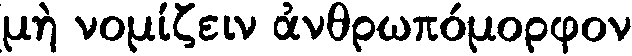

]; for indeed with many strangers of all sorts dwelling in their midst and practicing different habits of rites and sacrifice, their own traditional observances in honor of the gods had fallen into disuse. [3.2] Hence the natives of the land surmised that unless they removed the foreigners, their troubles would never be resolved. At once, therefore, the aliens were driven from the country, and the most outstanding [] and active among them banded together and, as some say, were cast ashore in Greece and certain other regions; their leaders were notable men, chief among them being Danaus and Cadmus. But the greater number were driven into what is now called Judea, which is not far distant from Egypt and was at that time utterly desolate []. [3.3] The colony [apoikia ] was headed by a man called Moses, outstanding both for his wisdom and courage. On taking possession of the land, he founded [], besides other cities, one that is now the most renowned of all, called Jerusalem. In addition he established the temple that they hold in chief veneration, instituted their forms of worship and ritual, drew up the laws relating to their political institutions, and ordered [] them. He also divided the people into twelve tribes, since this is regarded as the most perfect number and corresponds to the number of months that make up a year [3.4] But he had no images whatsoever of the Gods made for them, being of the opinion that God

[34] Henceforward (up to 3.8) the extract from Diodorus. The translation: Walton (1967) 279-87 (LCL ), with a few necessary emendations. The marking of the paragraphs of the extract is according to the editions of Dindorf (1828-31) and Bekker (1853-54), followed by Walton.

is not in human form [

]; rather the heaven that encompasses [] the Earth is alone divine, and rules everything []. The sacrifices that he established differ from those of other nations, as does their way of living, for as a result of their own expulsion [] from Egypt he introduced a [way of] life which is somewhat unsocial and hostile to strangers []. He picked out the men of most refinement and with the greatest ability to head the entire nation, and appointed them priests; and he ordained that they should occupy themselves with the temple and the honors and sacrifices offered to their God. [3.5] These same men he appointed to be judges in all major disputes, and entrusted to them the guardianship [] of the laws and customs. For this reason the Jews never [] have a king, and the leadership [] of the multitude [] is regularly vested in whichever priest is regarded as superior to his colleagues in wisdom and virtue. They call this man high priest [], and believe that he acts as a messenger [] to them of God's commandments. [3.6] It is he, they say, who in their assemblies and other gatherings announces what is ordained, and the Jews are so docile in such matters that straightway they fall to the ground and do reverence [] to the high priest when he expounds the commandments to them. There is even appended to the laws, at the end, the statement: "These are the words that Moses heard from God and declares unto the Jews." Their lawgiver was careful also to make provision for warfare, and required the young men to cultivate manliness, steadfastness, and, generally, the endurance of every hardship. [3.7] He led out military expeditions against the neighbouring tribes, and after annexing much land apportioned it out, assigning equal allotments to private citizens and greater ones to the priests in order that they, by virtue of receiving more ample revenues, might be undistracted and apply themselves continually to the worship of God. The common people were forbidden to sell their individual plots [], lest there be some who for their own advantage should buy them up, and by oppressing the poorer classes bring on a scarcity of manpower []. [3.8] He required those who dwelt in the land to rear their children, and since offspring could be cared for at little cost, the Jews were from the start a populous nation. As to marriage and the burial of the dead, he saw to it that their customs should differ widely from those of other men.[35] But later, when they became subject to foreign rule, as a result of their mingling with men of other nations—both under Persian rule and

[35] This is the end of Hecataeus's excursus. The next sentence is an addition by Diodorus; see p. 24 below.

under that of the Macedonians who overthrew the Persians—many of their traditional practices were disturbed.[36]

So he [Diodorus] says also here about customs and laws common among Jews, and about the departure of those same people from Egypt, and about the holy Moses, telling lies about most things, and going through the [possible] counter arguments, he again distorted the truth, and using cunning devices as a refuge for himself, he attributes to another [author] the abovesaid things which are contrary to history. For he [Diodorus] adds: "As concerns the Jews, this is what Hecataeus of Miletus narrated."[37]

First of all, some comments on the transmission of the text, its preservation, and its original location. Photius explicitly says that the extract was taken from Diodorus's fortieth book. In view of his declared purpose to expose Diodorus's "lies" and considering the typically Diodorean style and turn of phrase, it has rightly been assumed that Photius faithfully transmitted the text of Diodorus.[38] As noted by Diodorus at the head of the extract (3.1), he incorporated the excursus on the Jews at that point to serve as an introduction to his account of the confrontation between the Romans and the Jews, that is, the events surrounding the Roman occupation of Judea in the year 63 B.C. It followed the appeal alleged to have been made by a Jewish delegation to Pompey to dispose of the Hasmonean rulers and restore the Jewish "ancestral constitution" (XL.1a). The extract indeed provides background material for this claim: it elaborates on a Jewish patrios politeia , stressing its theocratic character and categorically stating that the Jews "never have a king."[39] The excursus also deals with the military preparation of

[36] This is the end of the extract from Diodorus. The following paragraph is a comment by Photius, supplemented by the closing sentence of Diodorus.

[37] The sentence closed the original excursus by Diodorus. On the copying mistake "Miletus" instead of "Abdera," see below.

[38] See Diamond (1974) 10-12. From codex 238 onward, Photius adheres to his sources, apart from slight and insignificant linguistic improvements. Abbreviations were made only to avoid duplications and stylistic awkwardness, or with regard to redundant details that detract from the main issue. See Palm (1955) 16-26, 29ff., 48ff.; Hägg (1975) 9ff. and 197-203, esp. 201-2. Treadgold (1980) 129 is probably mistaken in assigning Diodorus's excerpts in cod. 244 to what he calls class IIc; it should be class IIIc (see Treadgold's classification on pp. 82-83, 86, 90-91).

[39] Cf. Diod. XL.2.2: "their ruler called High Priest, not king." On the contents of the alleged complaint, see Bar-Kochva (1977) 177-81.

the younger generation for war, the motivation of the Jewish farmers to fight, and their abundance of manpower, which obviously are relevant for the coming military confrontation.

Diodorus's extract closes with the statement "this is what Hecataeus of Miletus narrated." "Miletus" instead of "Abdera" is certainly a slip of Photius or a copyist.[40] The original ethnography by Hecataeus was not an independent monograph, but an excursus. It was included in his great ethnographical work on Egypt, most probably as an appendix at the end of the origo-archaeologia section, the first of the four sections of the Ae-gyptiaca (Diod. I.28-29).[41] The Jewish excursus was just one of a number of miniature ethnographies of nations, tribes, and cities supposed to have originated from Egypt that were treated in the same context.

Diodorus states in the preface to the excursus that he intends to report on the "founding" (ktisis ) and "customs" (nomima ) of the Jews. The excursus indeed contains these two sections; it opens with the founding, namely the origo : the expulsion of the Jews together with other aliens (XL.3.1-2), the settlement of the Jews in Judea and Jerusalem under the leadership of Moses (2-3), and the establishment of political and religious institutions (3). Then follows the section on customs: Jewish faith (4), sacrifices (4), attitude toward strangers (4), the duties of the priests (4-5), the role of the High Priest and his authority (5-6), the organization of the army and military expeditions (6-7), the distribution of land (7-8), child rearing and demography (8), marriage and burial (8).

These were also the components of Hecataeus's original excursus. It included only ktisis and nomima , without geographical and historical sections, which were common in Greek ethnographies. These sections were also absent from the other minor ethnographies in the appendix to the Egyptian archaeologia-origo . Hecataeus was primarily concerned in that context to illustrate the origin of certain nations in Egypt, with the evidence of Egyptian influences on their customs to prove it. Geography and history of the new lands would have been quite out of place.[42]

[40] This has been universally accepted: see, e.g., Reinach (1895) 20; Jacoby (1943) 34, 46; Guttman (1958-63) 1.50; Diamond (1974) 128-30; Gabba (1989) 626. The only exception is Dornseiff (1939) 52-65. His arguments do not make sense. How easy it was to mix the two is indicated in a note by Aelian, NA 11.1

[41] See pp. 208-11 below.

[42] See in detail pp. 209-10 below.

At the same time, it is clear that the original content of the nomima section was not preserved by Diodorus in its entirety:[43] the account of the daily customs was omitted. This is evident with regard to circumcision (Diod. 1.28.2), sacrifice (XL.3.4),[44] and marriage and burial customs (XL.3.8),[45] and may also have happened to explicit references about Jewish exclusiveness (XL.3.4). The first four were omitted because they could not contribute to the aforementioned purposes for which the excursus was incorporated. Illustrations of the Jewish attitude toward strangers were left out, probably because they were very moderate in comparison with the sharp accusations and libels quoted by Diodorus from another source in a previous book (XXXIV-XXXV.1.1-3). Left in the nomima section are statements about Jewish institutions and remarks pertaining to Jewish military potential (training, motivation, manpower).[46] The account of Jewish belief was recorded not only because of its uniqueness, but chiefly owing to its relevance for understanding the Jewish theocratical system of government as described by the delegation to Pompey.

Hecataeus's original excursus thus opened with the origo , in this case the alleged expulsion of Jews from Egypt. Then came the nomima section, which seems to have comprised two main subjects: institutions and provisions made by Moses, and a collection of daily customs. As became customary in the new, Hellenistic, ethnography, the author uses one section to explain another. Here he stresses the influence of the origo on the creation and development of Jewish customs. The expulsion explains the "hatred of strangers" (XL.3.4). Daily customs

[44] Jaeger ([1938] 142ff.) suggested that Hecataeus's account of Jewish sacrifices was preserved by Theophrastus (ap . Porph. Abst . II.26). This has rightly been rejected on chronological counts; see M. Stern (1973).

[46] On the military implications of the reference to the rearing of children, see pp. 36-38 below.

are compared with those of the Egyptians, with some, like circumcision, being described as originating in Egypt (1.28.3). Others, like marriage and burial customs, were contrasted with those of the Egyptians.[47] Jewish beliefs, governmental institutions, and social provisions were not just listed but were given a causal reasoning.

Apart from the omission of the customs mentioned above, the references to the Jewish origo and nomima seem to represent the contents of the original text. In three cases there is a striking similarity between the excursus and references to Egyptians and Jews in Hecataeus's Aegyptiaca .[48] They indicate that even if some of the statements and explanations were abbreviated by Diodorus, the original meaning was not distorted. Significantly, Diodorus was not tempted by the vicious libels about Jewish origins and attitude toward strangers included elsewhere in his work (XXXIV-XXXV.1.1-4), nor by his own prejudice (XL.2.2, "lawless behavior of the Jews"): the Jews are not described as lepers, and the reason given for their expulsion is not in-suiting; the reference to Jewish hostility toward strangers expresses just some reservation. These passages certainly reflect the original Hecataean text.

The question whether Diodorus adhered to Hecataeus's vocabulary and syntax is more problematic. It can only be said that there is much of the Diodorean style in the excursus.[49] One sentence, however, is clearly an addition by Diodorus: it is agreed that the statement "but later, when they became subject to foreign rule, ... many of their traditional practices were disturbed" (XL.3.8) could not have been written by Hecataeus. It records changes in the Hasmonean period and is connected with the alleged complaints of the Jewish notables to Pompey. The reference to the "rule ... of the Macedonians who overthrew the Persians" indicates that it was written long after the end of Macedonian rule in Judea. A similar note was supplemented by Diodorus at the end of his epitome of Hecataeus's Egyptian ethnography (I.95.6).

[47] The references to Jewish marriage customs probably stressed Jewish incest prohibitions as opposed to Egyptian permissiveness (mentioned at Diod. I.27.1). An allusion to Jewish rejection of mixed marriages is also possible (cf. the abridged reference to Jewish exclusiveness, para. 4.)

[48] See Diod. I.94.2, and pp. 36-38 below on 73.7-9.

[49] See the detailed discussion of Diamond (1974) 13ff. Cf. Fraser (1972) II.1116.

The contents of the excursus raise a number of questions that have continually attracted the attention of scholars.[50] Did Hecataeus have real knowledge about Jewish antiquities? What were his sources of information? What were Hecataeus's guidelines in selecting the material? Does the account reflect Jewish life in the period of Hecataeus? To what extent was the account inspired by Greek practices, conceptions, and literary traditions? Does the excursus carry certain messages or didactic purposes? Did Hecataeus intend to idealize the life of the Jewish people or certain customs? How should Hecataeus's note about Jewish separatism and "hatred of strangers" be understood? Is it complimentary, or does it express reservation? And finally: what was, after all, Hecataeus's basic attitude toward Jews and Judaism? All these questions are relevant, in one way or another, to various points in the discussion on the treatise On the Jews . However, as they cannot decide the major issues,[51] and the purpose of this chapter is simply to introduce the reader to Hecataeus's work and references to the Jews, I shall refrain from examining in detail the numerous suggestions offered so far concerning these and related questions, and shall not attempt to exhaust all the points involved. The following discussion will try to sort out and define the significant problems, survey the relevant source material, and present what seem to me to be the right solutions. Of most interest to us will be the process by which the excursus was composed, and the considerations behind the selection, arrangement, and shaping of the material.

Do the accounts of the Jewish origo and nomima accord with Jewish tradition and history? At first sight the answer is firmly negative. Almost every clause, as it stands, can easily be refuted or found inaccurate. This, however, is a hasty conclusion. One has to distinguish

[50] See Radin (1915) 92-95; Engers (1923); Jaeger (1938) 144-53, (1938a) 139-41; Dornseiff (1939) 52-66; Jacoby (1943) 39ff. Guttman (1958-63) I.49ff.; Tcherikover (1961) 56-59, 119-25; Murray (1970) 158-59, (1973); Gager (1972) 26-29; M. Stern (1973), (1974-84) 1.29-35, (1976) 105-9; Wacholder (1974) 85-93; Diamond (1974), (1980); Hengel (1973) 564ff.; Lebram (1974a) 244-53; Momigliano (1975) 84-85; Wardy (1979) 638-39; Mendels (1983); Will and Orrieux (1986) 83-92; Bickerman (1988) 16-18; Gabba (1989) 627-29; Mélèze-Modrzejewski (1989); Sterling (1992) 75-78; Feldman (1993) 8-9, 46, 149-50, 234-36.

[51] See esp. pp. 55, 99-100 below.

between the facts and their reasoning. The explanations were provided by Hecataeus himself, and are typically Greek. The facts, except one or two, are based on Jewish tradition and history. What is mistaken is the dating and sequence. Hecataeus conflates three periods of Jewish history: (a) the time of the Exodus and the wandering in the desert; (b) the period of the settlement in Canaan; and (c) the Restoration, the Persian rule, and the days of the Diadochs. The three periods are telescoped into one, under the leadership of Moses, the founder. The account fails to distinguish between periods and stages of development, and ignores other long periods. Such telescoping, centering around the personality of the "founder" (ktistes , oikistes ), was quite common in Greek foundation legends and stories relating to the age of colonization, and even to later colonization activities.[52] Events and developments that occurred during long periods, under different individuals, were conflated into one period and attributed to one person, the leader-founder.[53] We shall see later that both the collection and the arrangement of the material were indeed strongly influenced by Greek foundation legends. The Judea portrayed is consequently not historical but mythological. It is difficult to know whether Hecataeus had consciously ignored the real sequence, or whether he had received the information sporadically and unsystematically, and presented it the way Greeks were accustomed to record foundation stories.

Disregarding inaccuracies that result from the conflation and the tendency to attribute everything to Moses, the following data reflect the tradition (as distinct from history) about Moses and his period: the Jews were once aliens in Egypt (Diod. XL.3.2); Moses was their leader and great lawgiver (3); they were divided into twelve tribes (3); their cult avoided images and sculptures (4); they believed in the divine origin of the law (5-6; cf. 1.94.2); the High Priest and priests were in charge of

[53] See Virgilio (1972).

sacrifices and cult (XL.3.4), and were appointed to handle major judicial cases (5; cf. Deut. 17.8-12); the Jews reared their children, and therefore were from the beginning a "populous nation" (Diod. XL.3.8; cf. Exod. 1.7, 11). There is even a paraphrased quotation of a formula that recurs in the Pentateuch (Diod. XL.3.6).[54] The second period provided the following data: the Jews settled in their country (3); they went to war against their neighbors and annexed lands (7). The statements that the lots were evenly distributed and were inalienable (7) also have biblical parallels.[55]

Other data and features recall Jewish life and institutions after the Babylonian exile and in the days of Hecataeus:[56] Jews were concentrated in Judea and Jerusalem (3); the Jewish deity was named "Heaven" (4);[57] the High Priest was the leader of the nation (5-6); the priests were, in addition to their cult duties, guides and guardians of the Torah (4-5);[58] there was no king (5); the Temple stood at the center of Jewish life (3, 5-6); the congregation was occasionally assembled in Jerusalem, and the Pentateuch was then publicly read by priests (5-6; cf. Neh. 8.1-8); the kneeling before the High Priest may be an inaccurate reflection of the practice to fall upon the ground and bow before the Lord on such occasions (Neh. 8.6);[59] the belief that the High Priest is a "messenger of

[54] Lev. 26.46, 27.34; Num. 36.13; Deut. 28.69, 32.44 (LXX). See Walton (1955); Wacholder (1974) 90 n. 89.

[56] That the excursus reflects Jewish life in the Persian period was stressed by Radin (1915) 92-95; Tcherikover (1961) 56-59, 119-25; and particularly Mendels (1983). The latter suggests that the reference to the building of the Temple by Moses originates from anti-Samaritan propaganda, that the attribution of Jewish institutions and practices to Moses and the statement that the Jews "never have a king" echoes an attempt by certain priestly circles to erase from memory the period of the kingdom (pp. 100-101), and that the description of Judea as being uninhabited at the time of the settlement applied to the time of the Restoration (p. 99).

[57] See Mélèze-Modrzejewski (1989) 6-7, referring to the Cyrus decree, two of the Elephantine documents, and the Books of the Maccabees.

[58] Cf. Mal. 2.7; II Chron. 17.8-9, 19.5-10, which reflect the Persian period. See also M. Stern (1974-84) 1.31; Will and Orrieux (1986) 85-86. Cf. Deut. 17.8-12.

[59] See also Sirach. 50.18, the kneeling of the people at the Temple on the Day of Atonement (noted by Diamond [1980] 88; Will and Orrieux [1986] 85).

God" (Diod. XL.3.5) is identical to a statement by the prophet Malachi, referring to the "priest" (Mal. 2.7);[60] certain priestly families seem to possess great estates, which may account for the statement that the priests were allotted greater lots than common people (Diod. XL.3.7);[61] the stress laid on the inalienability of lands may record a tightening-up of the Torah restrictions on selling lands, a likely feature of Nehemiah's social reform;[62] in addition to the Exodus traditions, the reference to the rearing of children may also record the situation in a Judea small at that time, and apparently overpopulated.[63]

These pieces of information were certainly provided by Egyptian Jews, probably of priestly descent.[64] Given such sources, what is the reason for the absence of any reference to the period of the Israelite and Judean kings (and the statement that "the Jews never have a king," 3.5)? Hecataeus, who served an absolute ruler and illustrated an ideal monarchy in the Aegyptiaca , had no motive for concealing that major period of Jewish history. The reason seems to be structural and literary: as was already mentioned, the Jewish excursus, like other miniature ethnographies incorporated in the same context, was planned to include just the origo and contemporary customs. It stands to reason that in interviewing his Jewish informants, Hecataeus was interested in collecting material for these sections alone. Consequently he was not informed about (or did not take notes about) matters relating to a historical section. The period of the Israelite and Judean kingdoms, as well as the Babylonian exile, had no place in the excursus. Summing up the implications of the account for the Jewish governmental system, it occurred to Hecataeus that the "Jews never have a king."

In addition to the Jewish informants, the use of Egyptian sources, oral or written, is evident in the statement concerning the expulsion of the Jews from Egypt.[65] Hecataeus seems to have preferred a moderate

[60] See Walton (1955) 255; Mendels (1983) 160.

[61] See Gager (1972) 33; Mendels (1983) 108-9.

[62] Similarly Tcherikover (1961) 122-23.

[63] On the overpopulation of Judea proper in the Hellenistic period, see Bar-Kochva (1977) 169-71, (1989) 56-57. Add the data about the mass deportation by Ptolemy I (see pp. 74-75 below).

[64] Suggested by Jaeger (1938) 146; Guttman (1958-63) 1.51; Murray (1970) 158; Gager (1972) 37; Diamond (1980) 81, 87.

version of the expulsion story,[66] and perhaps even to have "softened" it: to judge from other sources, the Egyptian versions related that the Jews were banished because they suffered from pestilence—leprosy and other diseases—or that they were loathed by the Egyptian gods, or both. In addition, in at least one source the Jews are also accused of impiety.[67] From Hecataeus's version it appears that the whole population in Egypt suffered from the plague, because the Egyptians themselves neglected the worship of their gods. They put the blame on the influence of foreigners who worshipped their own deities, and consequently expelled them. The inclusion of Danaus and Cadmus in the account, which did belong to the original Egyptian story,[68] by itself demanded a "softening" of the original tradition. Another "softening" is evident in the reference to Jewish hatred of strangers ("somewhat," 3.4),[69] which may be based on comments of Egyptians or Greek settlers, but could also reflect Hecataeus's personal impression.

There are, however, other references that could not have been based on Jewish or Egyptian sources, namely the explanations given for Jewish practices. There are also data that do not accord with Jewish traditions known to us: that the Jews settled in an "utterly desolate" land (3.2), that the first priests and all the High Priests were appointed according to merit (4-5), and that Moses made provisions for military training of the younger generation (6). This brings us to the much-discussed question of Greek influence.

It was suggested long ago, and has been repeated since by many scholars, that the excursus is an imaginary account of Jewish history and life based on Greek practices and conceptions. Thus, for instance, it

[66] The use of more than one source for the expulsion stories is indicated in Diod. 1.28.2; see Jaeger (1938) 146; Guttman (1958-63) I.50-51.

[67] See the versions of Manetho ap . Jos. Ap . I.229, 239-40, 248-50 (impiety); Lysimachus, ibid. 1.304-9; Posidonius ap . Diod. XXXIV-XXXV.1.1-2; Pompeius Trogus ap . Justin XXXVI.1.12. The version of Tacitus (Hist . V.3.1) ascribes the pestilence to the whole population, and the Jews are portrayed as being hated by the gods.

[68] See Bickerman (1988) 17.

[69] See p. 39 below.

has been argued that a good number of details actually record Platonic ideals. These statements are too general and sweeping. The whole question of Greek influence requires qualification and more precise definitions. In the great variety of governmental systems, institutions, and political ideas current in Greek civilization, it is not difficult to find a counterpart to almost every clause in Hecataeus's excursus, although these might represent different political models and conceptions. It should be emphasized once more, however, that almost all the data (as distinct from their reasoning) originate in Jewish tradition and history, and that the statements about the dominant role of the priests and High Priests do not accord with Hecataeus's political commitment. The latter references are also specifically Jewish, and the "quotation" from the Pentateuch is the best example for this.

Greek influence can be detected in: (a) the literary structure and sequence; (b) a few details that are absent from or are contradictory to Jewish tradition; (c) the terminology used for the factual material; (d) the explanations provided by the author for Jewish nomima . As far as the literary structure is concerned, we have already mentioned the application of the rules of the ethnographical genre: the division of the excursus into a ktisis (origo ) section and a nomima section, the causal connection between the two, and the reasoning of the facts. No less important was the structural influence of foundation stories. The conflation of three periods into one and the centering of the major historical developments and institutions around the personality of Moses were explained above by reference to the literary tradition of foundation stories. The influence of this tradition, noticed first by Werner Jaeger,[70] also dictated the selection and arrangement of the material for the two sections of the excursus.

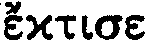

That Hecataeus treated Moses as a ktistes (founder and builder) and Jerusalem as his colony also appears from the terminology: the first section of the excursus is called ktisis (3.1), which may record Hecataeus's wording. The verb ktizein is explicitly used with regard to the alleged foundation of Jerusalem by Moses (3); Moses is said to have been leading (

[70] Jaeger (1938) 144, 146-47; id . (1938a) 140. Cf. esp. Lebram (1974a) 248-49. (The latter, however, thinks that the excursus is a Jewish forgery of the Hasmonean period.)

Greek settlement initiated by a mother city. Hecataeus uses this term even though he describes the Jews in the ktisis-origo as foreigners who were expelled from Egypt. Moreover, this is certainly not how Jewish informants would have termed resettlement in the land of the Israelite Patriarchs. Moses is described as a leader who excelled in wisdom and bravery (3), two virtues that are required of and attributed to founders (cf. Dion. Hal. II.7.1). He is not praised for "piety" (eusebeia ),[71] which Jewish informants might have been expected to stress. Here we have an indication of the selection technique.

Turning to the structure, the similarity with foundation stories is indeed striking. The events and processes recorded in the ktisis section (3.1-3) are known from foundation stories and follow their basic sequence:[72] the rise (usually by appointment) of a leader-founder, the emigration, foundation of the city (in foundation stories, building of a wall and then houses), building of a temple, drawing up laws, forming political institutions, and dividing the population into tribes. The nomima section opens with three references that deviate from the usual sequence: they relate to everyday customs unique to Jews (faith, sacrifice, and attitude toward strangers). It may well be that these references were originally located by Hecataeus at the end of the excursus, and were brought forward by Diodorus because of some association. These are followed by an elaboration of some of the institutions and laws founded by Moses that were only generally referred to at the end of the ktisis section. The sequence again principally follows that of foundation stories: establishment of judiciary and governmental system (3.4-6), preparation of the younger generation for war (6), expansion through military expeditions (7), distribution of agricultural lands and prohibition against selling them (7).[73] Even the final demand to rear children to increase the population (8) has its parallels in traditional foundation stories.[74]

[71] Noted by Bidez and Cumont (1938) 1.241; Jacoby (1943) 51-52; Diamond (1974) 228-29, (1980) 83-84.

[72] On the scheme and sequence, see E B. Schmid (1947) 176-77; Virgilio (1972); Graham (1982) 143ff.; Leschhorn (1984) 85ff., 106ff. Cf. Jaeger and Lebram (n. 70 above).

[73] On the equal distribution of lands and the literary tradition concerning their inalienability in Greek colonies, see Graham (1982) 1.51-52. Cf., for Rome, Dion. Halic. II.7.4.

[74] The most detailed is Dion. Halic. II.15.1-3.

The excursus closes with a number of daily customs that are compared with those of the Egyptians (3.8). This may have been the original location of the references to Jewish faith, sacrifices, and attitude toward strangers (4), but they may well have been attached by Hecataeus himself to the ktisis-origo by way of association (temple-sacrifice-[dietary laws]-apanthropia and misoxenia ). The inclusion of an account of daily customs is not typical of foundation stories, but is an essential component of ethnographies. This indicates that the basic structure of the excursus as a whole is that of a miniature ethnography, not of a ktisis . The distinction made by Diodorus between the first section (ktisis ) and the second (nomima ) may derive from Hecataeus himself, and reinforces this conclusion.

It must be admitted that the variety of subjects and their sequence in foundation stories were not so rigid as it might appear, and there were local variations according to the circumstances. The main features and basic order, however, are common to many foundation traditions. Naturally, some of them contained subjects not referred to in the Jewish excursus, since this local variation had no place for them. Most conspicuous is the absence of any consultation of an oracle by the founder before embarking on the expedition. Parallel Jewish information drawn from the Book of Exodus was available, but, Hecataeus having chosen the expulsion story, a consultation, which usually centered upon the question whether to emigrate or not, was redundant.

The influence of foundation stories may help to understand the origin of data that contradict or do not appear in Jewish tradition. The statement that Judea was "utterly desolate" (

[75] This is actually the suggestion of Diamond (1974) 246-49, though her discussion is spoiled by too many wrong assumptions.

concerning the age of colonization mention settlement in both inhabited and uninhabited regions. The latter situation seems to have been the more common, especially in such destinations as the Black Sea area. On some occasions, emigrants were invited by local rulers and did not have to occupy a place by force.[76] However, when referring to barbarian emigrations in the archaic age, Greeks tended to describe them as settling desolate lands.[77]

Another statement, which is not contradictory to but is absent from Jewish tradition, attributes to Moses the making of special provisions for war, especially with regard to the training of the younger generation (3.6). It is followed by the statement that Moses led the nation in wars against neighbors (7), which probably echoes some hazy information about the wars of Joshua. Such wars were frequently mentioned in Greek foundation stories as well. They were preceded by references to intensive military training, especially of the young, as one of the first steps taken in Greek colonies. Having described the Jewish settlement in Judea as a peaceful one, Hecataeus felt it necessary to introduce a stage of military preparations, before the wars of expansion, following the Greek model. We shall see later that Hecataeus also had a special didactic aim in making this point, and that in his Egyptian ethnography he emphasized the need to train the younger generation from childhood (Diod. I.73.9).[78] The requirements from the young, "manliness, steadfastness, ... endurance of every hardship," are typical of the Greek paideia .[79]

More problematic is the statement about the appointment of priests and High Priests. Jewish priesthood and High Priesthood were hereditary. Hecataeus seems to be unaware of this fact. He says that the first priests were appointed by Moses on merit (XL.3.4) but does not refer to later generations. With regard to the High Priesthood he states that it is always conferred upon the priest who excels in "wisdom and virtue" (5). It is hardly believable that the Jewish informants

[76] See the survey of Graham (1982) 92-143, 155. On the Black Sea: Vinogradov (1981) 11ff.

[77] M. Stern (1974-84) 1.30 draws attention to Hdt. IV.11.4 (the settlement of the Scythians); Dion. Halic. I.12.:1, 13.3 (Italy), and I.22.2 (Sicily). Cf. the place chosen for the foundation of the ideal city in Plato, Leges 704b-c.

[78] See pp. 36-38.

[79] Noted by Jaeger (1938) 152. See, e.g., Plato, Rep . 375-90.

deliberately misled Hecataeus on these matters. He may instead have misinterpreted certain complimentary references to the qualities of the priests and the High Priests. In addition, as the position of High Priest was sometimes conferred upon the brother of the legal heir,[80] some process of formal ratification must have existed. This being reported to him, it may have contributed to the misunderstanding. Hecataeus may also have had parallels in Plato's Laws (759a-b, 947a-b) at the back of his mind.

The Greek coloring of the facts (as distinct from their explanations) was also achieved by the application of classical political and philosophical terminology to Jewish institutions and practices. We have noted above the terms borrowed from foundation stories. To mention just a few more examples: the Jewish settlements are called poleis (Diod. XL.3.3), the position of the High Priest is defined as

As far as the explanations provided by Hecataeus are concerned, here the Greek influence is very much in evidence: the nation is divided into twelve tribes "since this is regarded as the most perfect number and corresponds to the number of months" (3.3; cf. Plato, Laws , 745b-d; Philo, De Fug . 184ff.);[83] the Jews are said to deify "Heaven" because it "encompasses the Earth... and rules everything [

[80] See Alon (1957) 72; M. Stern (1974-84) I.31, referring to Ant . XI.298 and XII.157, 237-38; II Macc.4.7ff. On Eliashib, brother (son?) of Yehoyakim, see Cross (1975) 7ff.

[82] Arist. Eth. Nic . 1995 19, 22, 1102 22; Pol. 1267 40, 1297 9, 1320 7 (see Diamond [1980] 94; Feldman [1993] 235).

[83] See in detail Guttman (1958-63) I.53-54. More references in M. Stern (1974-84) I.30.

not in human form" (4);[85] the priests receive greater lots to provide them enough leisure for performing their public duties (7; cf. Arist. Pol . 1269a 35, 1273a 34); the lands are inalienable to avoid the creation of great estates and consequent oppression of the poor classes and scarcity of manpower (Diod. XL.3.7);[86] a community of landowning farmers can easily rear children, and this secures the necessary manpower for the nation (8).[87] The attitude of Jews to strangers is called apanthropia and misoxenia and is explained by their xenelasia from Egypt, which is the term used exclusively for Spartan banishment of strangers.[88] Some inspiration was also drawn from Egyptian tradition to explain Jewish practices: the priests are given greater lots to enable them to be free to perform their public duties (7; cf. 1.72.2-3).[89]

It has frequently been argued that the excursus is an idealization of the Jewish people, and was meant to present a model of an ideal society.[90]

[85] See Xenophanes in Diels and Kranz (1935) 21(11) B 23, and the striking similarity with Hdt. I.131 (on Persian religion). Cf. Jaeger (1938) 147-48; Gager (1972) 31-32; Will and Orrieux (1986) 84-85; and esp. Guttman (1958-63) I.58-62. It is still to be proved that this explanation accords with the Jewish conception of the divine at the beginning of the Hellenistic period.

[86] Cf. Plato, Leges 741b; Arist. Pol . 1266 , 1270 18ff.; and see Guttman (1958-63) I.56-57; M. Stern (1974-84) I.33.

[87] See pp. 36-38 below.

[88] See Ginsburg (1934); Guttman (1958-63) 1.108-11; Murray (1970) 158-59.

[89] Cf. also Euhemerus's utopian treatise on the Panchaeans, where the priests are given, for the same reason, a double share of the produce (Diod. v.45.5).

[90] See esp. Jaeger (1938) 149, 151-53; id . (1938a) 141; Guttman (1958-63) I.53-65; Murray (1970) 158-59; Hengel (1973) 564ff.; Will and Orrieux (1986) 87-92; Bickerman (1988) 17; Mélèze-Modrzejewski (1989) 12-13. The most outspoken is Joshua Guttman, who describes Hecataeus's version as "a complete and absolute idealization" (p. 63). Guttman says further: "He [Hecataeus] sees the Jewish constitution in the spirit of Platonic doctrine, as blessed in all the advantages of a perfect and exemplary constitution, for it has a divine origin and accords with the rules governing the cosmos. Consequently, the Jewish political system, according to Hecataeus, lacks all the defects that harm the political systems of other nations, and deserves, therefore, to be a model of imitation for all mankind" (p. 66). In contrast to these views, see Jacoby (1943) 48ff.: "es ist ganz deutlich, dass er [Hecataeus] das jüdische wesen nicht als vorbildlich, sondern nur als fremdarting empfunden hat." Cf. Diamond (1980).

The model, however, has been variously described as a "theocracy" or "aristocracy," inspired to a great extent by Plato's Laws and Republic respectively, a "Spartan oligarchy," and even an "Egyptian Sparta."[91] It has also been suggested that the account describes a "mixed constitution" made of all these. As a matter of fact, none of these conceptions, singly or in combination, perfectly concurs with the contents of the excursus.[92] What should really be asked is whether Hecataeus actually aspired at the outset to idealize the account, and present all of it as a model. The answer must be that he did not. Hecataeus, who served Ptolemy I, would hardly have advocated a society without kings, with the power being entrusted entirely to priests. This also stands in contrast with the government presented in his Egyptian ethnography. It should be reiterated that, by and large, Hecataeus recorded the information provided by his Jewish informants. The interpretation is basically what one would expect to be made of the facts by a Greek intellectual who had a good philosophical education, if he was not himself an original philosopher. The account does not include superlatives or even praises, and it is difficult to see features that could be admired or advocated by Hecataeus, except for those pertaining to military manpower.

The latter features were emphasized, supplemented, and explained with much elaboration, having in mind the Greco-Macedonian reader in Egypt. Much stress was laid on military training of the younger generation, allocation of equal lots, inalienability of land, and the great

[91] The expression of Murray, loc. cit . (n. 90); cf. Will and Orrieux, loc. cit . (n. 90). Noteworthy are the attitude toward strangers, the distribution of equal lots, the inalienability of lands, and the training of the younger generation.

[92] Thus, e.g., the encouragement to rear children and increase the population (without setting a limit) does not accord with the ideal of Plato (Leges 741d; 928c-930) or Aristotle (Pol . 1265 35ff., 1326 4ff., 1355 20ff.), nor with Spartan practice. The same applies to the account about the status of the priests and their allotments, the High Priest, the veneration of the High Priest, and the divine source of all the laws. To equate the priests with Plato's "guardians" or "sages" would not resolve the differences, and would even raise new ones (e.g., the ownership of land).

rate of natural increase that was implicitly praised. A close look at the explanations provided reveals the message: farmers should have viable lots and a sound economic position so that there will be no "scarcity of manpower." The agrarian arrangements are also the way to encourage rearing children. As a result, the Jews are a "populous nation" (3.8). The causal connection in the first point is not made clear, and the advantage of the second is not explained. Hecataeus's original reasoning may well have been cut short by Diodorus. To understand it, we have to turn to the corresponding passages concerning the Egyptian warrior class in Hecataeus's Aegyptiaca . The main features and their explanation are actually identical:[93]

The last part [of the land] is held by the warriors [machimoi ], who are subject to call for all military duties, the purpose being that those who hazard their life may be loyal to the country because of this allotment of land [klerouchia ] and may thereby eagerly face the perils of war. For it would be absurd to entrust the safety of the entire nation to these men and yet have them possess in the country no property to fight for valuable enough to arouse their ardour. But the most important consideration is the fact that, if they are well-to-do, they will readily beget children and thus so increase the population that the country will not need to call in any mercenary troops. And since their calling, like that of the priests, is hereditary, the warriors are incited to bravery by the distinguished record of their fathers and, inasmuch as they become zealous [students] of warfare from their boyhood up, they turn out to be invincible by reason of their daring and skill.

The distribution of land and the efforts made for the welfare of the settlers are thus intended to provide them with a good motivation to fight. This is the meaning of the argument of the Jewish excursus that economic hardships "bring on a scarcity of manpower." Even more important is the second purpose: to encourage and enable the settlers to rear children and thus "increase the population." The aim is to secure a situation in which "the country will not need to call in any mercenary troops." Here we find what is missing in the Jewish excursus: rearing many children and becoming a "populous

[93] Diod. 1.73.7-9. The translation: Oldfather (1933) 253-54 (LCL ). On the rearing of children in Egypt, see also Diod. 1.806, where it seems to be factual and free of didactic and military connotations.

nation" confers a military advantage (cf. Polyb. XXXVI.17.5-11). Just as with the Jews in the excursus, the younger generation of Egyptian warriors was trained for war from childhood. The terminology applied in the passage should also be noticed: machimoi and klerouchiai were the official Hellenistic terms for military settlers of Egyptian descent serving under the Ptolemies, and their settlements, respectively. In the third century, the term klerouchiai

The correspondence of these data and explanations with the situation of the Greco-Macedonian settlers in Ptolemaic Egypt cannot be coincidental. Scarcity of European manpower was the most acute problem facing the young Ptolemaic empire. The Greco-Macedonian conquerors of Egypt were a tiny minority amid the native population, and the possibility of recruiting Greco-Macedonian mercenaries was rather limited, these being divided between the armies of the Successors. In the first generation of the occupation, Ptolemy recruited Egyptians to the army as light troops (e.g., Diod. XIX.80.4), making sure not to provide them with heavy weapons.[95] Hecataeus, who was considering the future of the kingdom, must have realized that even this solution could only be temporary. In the long run, arming and training the natives at all might prove dangerous to the very existence of the Macedonian regime in Egypt. Hecataeus, therefore, suggests measures that will invest in the younger generation of Greco-Macedonian settlers: encouraging the birth and raising of children (contrary to the traditional practice in the motherland), allocating equal and sufficient lots to the settlers to enable each one to raise a large family, prohibiting the sale of lands to secure the continuity of this class of farmer-soldiers, and constantly training the descendants of the first generation of settlers. Ptolemaic military settlement was indeed organized along such lines, but gradually deteriorated, neglecting the preparation of the younger generation for war. As a result, in 217, on the eve of the battle of Raphia, Ptolemy IV was

[94] See Lesquier (1911) 5-8, 30ff., 175ff.; Oertel, RE s.v. katoikoi , 17-18; Holleaux (1938-57) II.37-38; Uebel (1968) 4-11. In the third century B.C. the term klerouchiai was applied also to settlements of European settlers, while in second-century Ptolemaic Egypt it was used only for settlements of native soldiers, to distinguish them from katoikiai , settlements of Greco-Macedonian soldiers.

[95] See Lesquier (1911) 6-7, 19-21; Griffith (1935) 109, 112; Launey (1949-50) 1.589; Bar-Kochva (1989) 96 and n. 27.

forced to recruit thousands of Egyptians and to train them as phalanx warriors. The success of these troops in the battle of Raphia raised the self-confidence of the local population and generated a revolt that lasted thirty years, leaving the Ptolemaic kingdom at the mercy of its Seleucid rival.[96]

The assumption that the excursus is a highly idealized account intended to be a model has led a number of scholars to suggest that the reference to the Jewish attitude toward strangers (3-4) was meant to express not reservation but praise.[97] However, in addition to the connotations of apanthropia and misoxenia in Greek culture, which could not be favorable, the qualifier

How then should the attitude of Hecataeus toward the Jews be evaluated? Having a basically unbiased attitude, Hecataeus presented the information available to him while interpreting certain features

[96] See Milne (1928) 226-34; Griffith (1935) 117, 123, 140; Préaux (1939) I.28-52; Will (1967) II.35-36; Bar-Kochva (1989) 96-98.

[97] See Guttman (1958-63) I.63; Lebram (1974 ) 274; Diamond (1980) 85-86; Gabba (1989) 629. Cf. the variations of Gager (1972) 35, (1983) 40; Will and Orrieux (1986) 92-93. On the negative character of the sentence, see Reinach (1895) 17, 19; Willrich (1900) 89; Radin (1915) 93-95; Jacoby (1943) 48-49; Tcherikover (1961) 360; Murray (1970) 144; Sevenster (1975) 188-90; Mélèze-Modrzejewski (1989) 11-12; Feldman (1993) 126.

according to Greek experience and conceptions. This is just how a Greek author-philosopher would have dealt with the facts; it does not mean that the excursus is an idealization or a "model." The account of the preparation of reliable manpower (including the strict agrarian arrangements) is the only part intended for emulation. However, even this is still not a deliberate idealization: the information given by the Jews is presented in the way Hecataeus, as a Greek, understood it.

One should not exaggerate the significance of the excursus. Hecataeus did not attach so much importance to it as might appear from modern scholarly interpretations. The Jewish excursus was just one of a number of minor ethnographies incorporated into the Aegyptiaca. They each presented a different system of government and society. In the way many Greeks viewed most oriental nations at the beginning of the encounter between the two great cultures, so Hecataeus viewed the Jews: he was curious and impartial, attempting to understand the information according to his education and way of thinking. He was indifferent on most topics, but appreciated some features and expressed reservations about others. This discerning evaluation is expressed in a factual style, combined with elaborate reasoning, without explicit compliments, exclamations, or superlatives, and avoiding rhetorical-emotional expressions. Despite the philosophical interpretation of their faith, the Jews are not described as a nation of philosophers, although this appears in contemporary Hellenistic literature.[99] After all, even in referring to Egyptian religion, Hecataeus describes their "first god" as being "the same as the universe [

To sum up the discussion: How can the process of composition be imagined? Hecataeus planned an excursus that would include an origo section and a nomima section, to be incorporated among other