7—

Epilogue

The network of Baja Californios who settled in San Diego county was at its height in the 1930s through the 1950s, as families coalesced in Lemon Grove. It is important to note that during the second quarter of the twentieth century these families became rooted in San Diego, and in Lemon Grove specifically. Most offspring were American citizens by birth and were members of a community that was home to them. The towns from which pioneer migrants came were still remembered, and indeed still visited from time to time, but these pueblos were no longer the bases of out-migration or kinship that fostered the development of the network in the mines or the United States. The people in Lemon Grove depended on and sought assistance from their kin, neighbors, and friends who had decided to settle in the United States.

Changes in both the immigrant community in the United States and along the border altered the nature of migration and immigration after the 1930s. Before the thirties families had traveled as groups and entered the U.S. in the footsteps of other immigrants who had followed the migration north and were in the process of settlement. These early crossings of the border were not restricted and immigration was relatively easy, but as developments along both sides of the border drew increasing numbers of people, U.S. border policy focused on immigration control. Multiple border crossings and the mobility that had been a pattern in the early period of settlement were no longer possible for newcomers. Migrants were discouraged from crossing the border and those who did entered an Anglo environment for short periods rather than as settlers. In the forties and fifties and thereafter, the Californio

community in San Diego was no longer seen as a group of peninsulars but primarily as a settled U.S. community. U.S. kin continued to offer support based on kin relationships (parentesco, compadrazgo, and family intermarriage), but migrants no longer traveled as kin units or families. Family members continued to arrive from the south, but the majority came for short visits to the homes of kin. Some migrants recognized that U.S. kin were well acquainted with the Anglo environment and could provide help in finding jobs and housing.

During the twenties and thirties a number of sociopolitical circumstances challenged the solidarity of the network and the settlers of Lemon Grove. By the 1930s Lemon Grove had become a prosperous little community, but the depression brought economic and social constraints not only for the people of Lemon Grove but for all people of Mexican descent in the United States. The economic collapse sustained by the nation as a whole resulted in resentment against the growing Mexican population in the United States. This was particularly true in the Southwest, where the Mexican immigrant population was the largest. The basis of this sentiment was the fear that Mexicans were taking jobs from U.S. citizens and filling the welfare roles without any desire to become U.S. citizens. As the nation's economy worsened and unemployment rose, official government action reflected this reaction. National changes in immigration policy specifically aimed to curtail Mexican immigration to the United States, and a national repatriation plan was organized to alleviate the Mexican alien problem. The Hoover administration's official policy of repatriation resulted in the repatriation of over 400,000 people of Mexican descent, many of whom were U.S. citizens by birth (Balderrama 1982; Bogardus 1934; Cardoso 1974; Divine 1957; Hoffman 1974; Romo 1975; Scott 1971). In California official reports and measures heightened latent prejudices and fears concerning the growing Mexican population (Hoffman 1974; Alvarez 1986; Balderrama 1982). Media reports of alarming growth rates in the Mexican population fueled the resentment. In this atmosphere the strong maintenance of the Spanish language, values, and life-style among Mexican settlers confirmed the view that these people were a threat to the general populace. Communities such as Lemon Grove, where Mexicans congregated and lived together in "little Mexicos," became targets of public and official action.

In the late 1920s and into the 1930s schools throughout the Southwest, in Texas, Arizona, and California, began Americanization programs for immigrants (Weinberg 1977; Taylor 1928; Carter 1970).

Segregation in these schools was sanctioned under the guise of help for the immigrant. Such schools were widespread in the Los Angeles area and in the San Joaquin and Imperial Valleys of California. In Lemon Grove these actions were perceived as threats to the livelihood of the Californio network, and the Californios responded by a concerted tightening and activating the community and network.

In January 1931 the local school board in Lemon Grove attempted to segregate the children of the Mexican settlers into a specially constructed school. The PTA and the board of education met to plan the separation that would exclude the Mexican community. A two-room school was built in the heart of the Mexican community, the school board assuming that the Mexican community would docilely separate itself and send its children to the new school. The school, however, became a point of contention and the Mexican parents refused to comply with the act of segregation, relying on the bonds of solidarity that had brought them to the United States and made their settlement possible. This action clearly reveals the network as a communal organization with a goal that was not simply familial or individual, as in mutual aid for jobs and housing in the past, but communal. This was true network mobilization. When the school board took action to separate the children of Mexican descent from "American" children, the Mexican families organized a neighbors' committee and vowed to fight the school board's action. The new school, boycotted by all but one family, became known as the caballeriza (the barnyard). The Californio community, in a well-planned response, took their grievance to the public. Local as well as statewide Spanish and English newspapers published accounts of the segregation as well as appeals from the Lemon Grove Neighbors Committee for financial and moral support (Alvarez 1986).

Many of these parents had come north on the mining circuit or had arrived via steamer from Baja California, but most of the children had been born in the United States. The parents were incensed by the attempt at segregation and based their appeals on the U.S. citizenship of the children, the majority of whom had been born in the United States and had attended the regular school for over a decade. The parents also sought help from the Mexican counsel in San Diego (Balderrama 1982; Alvarez 1986), who took a keen interest in the case and assigned two sympathetic lawyers to defend the community. Reports in Mexican newspapers followed the case closely, and the Mexican government was in full support of the community's action.

The community filed a writ of mandate with the Superior Court of

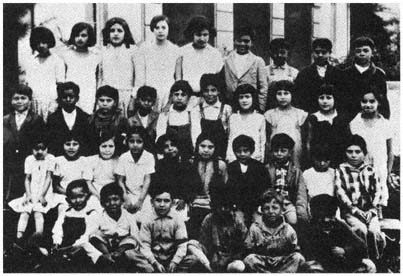

First-generation U.S. citizens at the Lemon Grove school at the time of the

school desegregation court case, c. 1931.

(Courtesy of María Smith Alvarez)

the County of San Diego charging the school board with segregation. In early 1931 the case was heard in San Diego. Children took the stand to prove their knowledge of English and their general progress in school. In March 1931 the court ruled in favor of the Mexican community of Lemon Grove and demanded the immediate reinstatement of the children of Mexican descent in the regular school. The importance of this case, which was the first successful court action in favor of school desegregation in the United States, has only been recognized recently. In addition to the legal and social ramifications this case illustrates in dramatic form the mobilization of a group of Mexican immigrant families. This action was clearly the outcome of network alliance that has been conditioned over several generations of time. The parents who formed the neighborhood organization and fought the school board included members of the Alvarez, Castellanos, Smith, Romero, Sotelo, Gonzales, and Simpson families among others, all of whom had come north along the mining circuit and settled in Lemon Grove. In addition to these families, incorporated families, now a strong

part of the community, provided additional leadership and strength in the school battle. The roster of eighty-five schoolchildren named for the school case is a list of family names whose heritage was to be found in the towns of the southern peninsula. The case itself, Roberto Alvarez v. the Lemon Grove School Board, was named after one student who represented the children at large.

In addition to this mobilization of the network in united legal action, the Californios continued to offer mutual aid and assistance to one another during these periods. The depression was hard felt everywhere, but the community survived. Work in the lemon fields continued, but wages were low and the overall hardships served to begin dispersing individuals and families, although in small numbers. Few families were repatriated, and there is only one instance of deportation during this period, an action directly linked to the school segregation case. In an attempt to apply pressure to the community one family was singled out and, on the grounds of truancy, deported in the midst of the school case. The Ruiz family had long been in Lemon Grove and the children, like the majority of the schoolchildren, had been born and raised in the U.S.

While Californios were sometimes forced to seek jobs outside of Lemon Grove, the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps by President Roosevelt also furthered outside contact for the people of Lemon Grove. Many of the young men were recruited into the CCC and taken into service throughout the state of California. This action helped families in a number of ways. It provided a source of income (which was sent home to parents) and lessened the burden on individual households. These men were exposed to new life-styles in new areas which for some provided incentives for careers unlike those known in Lemon Grove. Nonetheless, when the depression ended, most of these individuals returned to Lemon Grove and San Diego.

The economic and social stresses in the thirties were clearly serious threats to the Mexicanos of Lemon Grove. The school case illustrates more than the community's adaptation to the life in the United States and the mobilization of the network. It also shows the attitudes that prevailed among parents toward settlement and survival in the United States. Children were expected to attend the local school as a way of further adaptation. In fact, these children, the first generation of immigrant offspring, attended school and were socialized into a sociocultural environment far different from the ones their parents had experienced.

Thus, although the majority of these children attended only grammar school, they belonged to a cohort that blended U.S. and Mexican life-styles and outlooks.

As the depression ended the Californio community continued to rely on the cultural foundations established by the migrant generation. The depression had further solidified the family network both through the successful coalition against the school segregation case and through the mutual aid people offered to one another during this period of scarcity. Then in the late 1930s the community mobilized again, this time to protest poor wages for the lemon workers. Lemon Grove had become a center of Mexican labor, but this united action was countywide and included Mexican communities from other parts of San Diego. In 1938 the field-workers in Lemon Grove organized a union called La Union de Campesinos y Obreros (The Agricultural and Workers Union). Meetings were held in Lemon Grove and the union became part of a large struggle in Mexican communities in Southern California. Many of the primary actors were individuals who had come from the southern peninsula, but these folk were no longer immigrants—they were now settlers striving to make a decent living in the United States.

The decade of the 1940s brought new challenges to the families. By this time an entire generation of Californio children had been raised in the United States along the border. Although most of these families continued to maintain ties in Mexico where kin and friends remained, allegiance to Baja California now stemmed primarily from the experiences of parents and older kin who a generation before had created the little community of Lemon Grove. The cohort of the U.S.-born Mexican-American youth had attended U.S. schools and had become conditioned to many of the values of the U.S. society. Perhaps nothing illustrates this new allegiance as clearly as the response of this Californio youth generation to the Second World War. Although these individuals were tied to the border, continued to speak Spanish, and considered themselves "Mexicanos," the majority of young men old enough to volunteer joined the U.S. armed services. For the network this meant a further dispersal of family members. Although most men returned to San Diego at the end of the war, many had learned new skills and had been exposed to new environments.

New industry and growth in San Diego also resulted in dispersal of individuals from Lemon Grove. Lemon Grove had begun to change and by the beginning of the forties was no longer a primary attraction

for Californios and other Mexicans. New opportunities for land development and housing signaled the end of the lemon business and with it the jobs in the packinghouse and citrus fields. The rock quarry ceased operation and most individuals were forced to seek employment outside of the community. During the thirties some families had moved into Logan Heights in the city of San Diego where a large Mexican community developed (see Camarillo 1979). People were attracted by the presence of friends and kin as well as by easier access to the city, where a new industry—the tuna canneries—attracted Mexican labor. The canneries employed hundreds of men and women and, like the jobs of the orchards and packinghouse in Lemon Grove, brought together many network families around Logan Heights. The canneries were built along the San Diego harbor within walking distance of the growing community of Logan Heights. Work in the canneries renewed common ties and the Californios formed new friendships, especially with other peninsulars, as in the past. Tuna fishing, shipbuilding, and the naval base and aircraft companies flourished during the forties. These industries acted as a major attraction for citizens of all backgrounds.

Logan Heights was just eight miles from Lemon Grove, and visits to the friends and kin who remained there was easy. The community continued as a cultural core. Family celebrations were still community events, and the families that remained attracted people from San Diego and from across the international border in Tijuana, Mexicali, and Tecate.

Although the forties were marked by numerous intermarriages among the families of Lemon Grove, which strengthened the network bonds, the problems of the thirties, the war, and the changes in Lemon Grove itself fostered a new outlook among the younger generation. The generation born in the forties was tied to the kin network through the institutions that had made settlement possible, but these were no longer rooted to the geographic base in Lemon Grove. Many families remained in Lemon Grove and their children attended the local school, but now members of the community were dispersed in other areas of San Diego county. A conscious choice of environment and the desire for better schools resulted in a further dispersion of the network. During these years family network members continued to rely on one another for primary relationships, but new friendships developed within new neighborhoods and places of employment. In addition to marriages within the network, compadrazgo relationships intensified between the

family members as this new generation of adults continued to seek out one another. Family ceremonies were multiple. Birthdays, baptisms, and funerals, bringing together the remaining pioneer migrants and their offspring with the new generation of offspring, served to further the existing ties of the families.

Geographic dispersion of the network at first did not mean the serious weakening of communal relations. The institutions that had bound Californios together over geographic space, through the mining circuit, were now at work in San Diego county. People continued to congregate in the community at the homes of surviving pioneers. The celebrations that marked the formal institutions of marriage and baptisms were family and community events. For in addition to celebrating specific transitions for individuals, these ceremonies reemphasized the bonds and the families that were part of a recognized community. This included kin and friends who now lived on the Mex-

Women of the Salgado Smith family in Logan Heights, San Diego, summer

1937. Left to right: María Smith, María Sepulveda, unidentified, unidentified,

unidentified, unidentified, Dolores Salgado Smith, unidentified, and

Guadalupe Salgado.

(Courtesy of María Smith Alvarez)

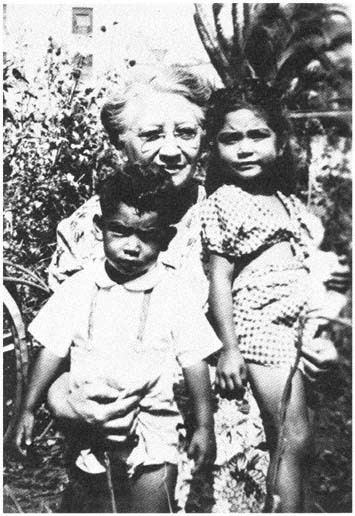

Ramona Castellanos with two grandchildren, Roberto and Guadalupe

Alvarez Smith, c. 1947.

ican side of the international border. These were times in which the family played an important role in solidifying and impressing specific values and outlooks on the past and on the pioneers. Ties to the peninsula and its heritage were now centralized in Lemon Grove and

the surviving elders. My parents and their generation were bred in the small town of Lemon Grove and their life symbolized important values that they taught their offspring. They considered themselves Mexicanos, but they were also American citizens, born in the United States, striving to make their lives better. Their move out of Lemon Grove served to place the next generation in a new sociocultural environment, exposing individuals to influences and decisions that were not part of the past. In the end the economic prosperity of the fifties and the sixties provided jobs and living alternatives not afforded earlier. The trend of a new era for the network had truly begun.

An important factor in the change of social relations during this time was the passing away of the elders. As the last of the pioneers died, communal events became less frequent. Celebrations continued to be familial gatherings, but individuals and their families became less and less tied to the network. Job responsibilities, educational preferences, and new friends influenced this new generation to begin shifting some of the alliances of the past.

By the end of the sixties a whole life-style had passed away. Lemon Grove itself was no longer a little community of pioneer Californios but a growing suburb of San Diego. Lemon groves and other citrus had given way to real-estate speculation. New developments in and around Lemon Grove brought more people into the town and contributed to diversification of the area. Mexicans continued to arrive in the area, but the community was not a focus of jobs. Mexican immigrants now turned to Chula Vista, National City, and Logan Heights, urban communities growing in response to the development in San Diego and the border region. The lemon fields and the related economy were forgotten. Today the only reminder is a large concrete lemon monument that marks the center of town.

My generation grew up socialized into two worlds. Lemon Grove and the communities to which pioneers had moved formed an intrinsic part of our social relations, but this was buffered by daily contact in neighborhoods outside the realm of the immigrant outlook. Schooling and other experiences fostered new values and aspirations that steered individuals into totally new life-styles. Intermarriages between pioneer families became the exception as individuals sought support from new matrices of social bonds created outside the family network. Only the celebration of wedding anniversaries, baptisms, and the occasional marriage continues to unite original family members. Funerals, espe-

cially of respected elders, have become the final reason for bringing together those people who lived through the settlement and life in Lemon Grove.

Los Castellanos in Logan Heights, San Diego, 1972. Left to right:

Tiburcio, Juana, Francisca, Narcisso, and Ricardo.

(Courtesy of Francisca Castellanos de Moreno)