“Ceilings of Glass”[15]

Real or imagined persecution, then, does not explain the emigration of Lebanese peasants. Instead, as one can imagine, each emigrant had an individual tale of the events that led him or her out of the village and onto roads to foreign lands. In 1884 Da‘ad Fatūh left her husband and two-year-old son in Lebanon and sailed to New Orleans to make money.[16] Tafeda Beshara's aunt, Sadie, came back for a visit to Rachaya from the United States and convinced Tafeda's father to let her take the little girl, whose mother had died, back to Hartford to “bring her up.”[17] After completing his education at the American University in Beirut, Sim‘an Abdenour left that city in 1906 to attend the medical school at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.[18] In light of these and many other stories, it would be inadvisable to speak definitively of a cause or causes for Lebanese emigration. However, amidst the great variety of stories and the history of the 1880s and 1890s, a pattern of emigration can be discerned. People seem to have left for the Americas because they could and because they wanted a better life. Trite as these two reasons may appear to be, they in fact explain much of the human movement across continents. A more detailed explanation will illustrate my point.

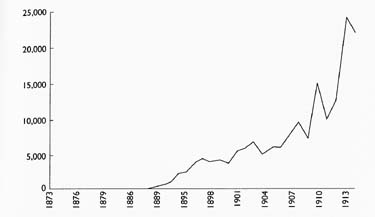

From Figure 1, it should be apparent that far more emigrants left Lebanon for the United States after the turn of the century than before. Similar patterns of emigration hold true for South American destinations like Brazil and Argentina.[19] If one adds to this the fact that the great majority of the emigrants (96 percent) were in their forties or younger,[20] then one can assume that most of the men and women who emigrated were born after 1860. The significance of this conclusion surfaces if one recalls that the Règlement Organique of 1861 mandated a greater measure of individual freedoms for the inhabitants of Mount Lebanon. Among these was freedom of movement without interference on the part of the political elites, the shuyukh, of the Mountain. The cynic could dismiss such legislation as nothing more than words on paper. Yet, thirty years after the fact, and particularly for the generation born after 1860, which had no encounter with the earlier and more arbitrary power of the shuyukh, these words were legal measures that did open venues of social and physical movement within and out of the country.

Figure 1. Rate of Lebanese emigration to the United States. Figures from Immigration Commission, Reports of the Immigration Commission: Statistical Review of Immigration, 1820-1910, 61st Cong., 3rd sess., 1911, S. Doc 756, and Reports of the Immigration Commission, 63rd Cong., 3rd sess., 1915.

Commentaries from various sources help establish this point. In a report in 1885 the Russian consul in Beirut, Constantin Dimitrievich Petkovich, states:

A petition by Shi‘a villagers addressed to the British consul Arthur Eldridge supports these contentions. In their letter the peasants requested Eldridge's help in annexing their lands to the Mountain because “people there enjoy greater security, freedom and smaller taxes.”[22] More tellingly, we find that in most personal accounts of emigration the Ottoman authorities rarely make an appearance. While stories of seasickness, excitement, and fear on reaching new cities like Montevideo and tales of circumventing immigration officers abound in these accounts, we do not come across any mention of Ottoman officers, or others, stopping the emigrants. Instead, and after a few unsuccessful attempts at halting the emigration movement, the Ottomans simply acquiesced to its reality.Despite the many faults one can find in the Lebanese administration . . . one must admit that this administration has contributed in large degree to the improvement in the material and moral state of the population. . . . For the current Lebanese administration has guaranteed for the Lebanese a greater measure of tranquility and social security, and it has guaranteed individual rights. . . . With this it has superceded that which the Ottoman administration provides for the populations of neighboring wilayat [province].[21]

The Sublime Porte began to be alarmed by the high rate of emigration from the Mountain toward the end of the 1880s. A series of letters exchanged between the central government and the Mutasarrif of Lebanon discuss the possibility of limiting emigration by vigilantly applying existing rules and regulations dealing with the issue of travel documents. Yet, despite this official attention, the illegal use of internal travel documents (tezkere) for the purpose of emigration continued unabated through the 1890s. The Ottoman officials did not have the means to police the long coast of Lebanon. Sarrafs (smugglers) worked through gaping holes in the coastal border to ferry peasants on board European steamboats that made unscheduled stops in the Christian ports of Jounieh and Jubayl. Corrupt police officers were also quite willing to look the other way—in exchange for a few piasters—as aspiring emigrants in Beirut and Tripoli illegally boarded boats heading for Marseilles, Barcelona, and Liverpool. Compounding this porous situation was the large number of tezkere that were being issued by the Mutasarrifiyya. For example, in May of 1892 the Beirut police superintendent reported that large numbers of Lebanese were boarding boats in Beirut and Tripoli bound for other Ottoman ports. He added that while he was certain that these individuals were actually intent on emigrating, he could do little to stop them since they held valid travel permits.[23] Given all these difficulties, the imperial government, on the recommendation of the governor of Beirut, “issued a decision [in 1899] suppressing the regulation that prohibited the emigration of the Syrians.”[24] Not surprisingly, soon after that decision the numbers of annual emigrants from Lebanon went from the hundreds to the thousands.

Unfettering the peasants from the land is but one part of the puzzle of this migration movement; another was money. It took money to leave the village, buy a ticket, bribe officials, pay off the sarrafs, stay at hotels along the way, and take care of oneself in the first few days—at least—of arrival in the new country. To legally obtain a tezkere the peasant had to pay close to 50 piasters in official and unofficial charges, in addition to securing—after the change in Ottoman immigration policy in 1899—a bond equivalent to $178. At the port of Beirut throughout the 1890s, emigrating peasants had to pay various fees (“barge expenses,” “donations” to the Hijaz railway project) amounting to over $9. To get on the steamboats, peasants purchased tickets from Beirut to Marseilles and on to New York or Rio de Janeiro at a cost ranging from $10 to $15. Hostelries where emigrants stayed along the way were another expense. An advertisement on the front page of the semiofficial newspaper of the Mutasarrifiyya, Lubnan, announced in 1907 that the Hotel de Syrie in Marseilles was ready to welcome “our travelling Syrian brothers.” It promised furnished and unfurnished rooms with facilities for cooking and cleaning, as well as assistance in making travel arrangements “to all parts of the world.” According to the advertisement, rooms started at 30 paras (2.6 cents) per night, although in reality the rooms cost ten times this amount, and the emigrants were thus about $4 poorer by the time they checked out.[25]

More depleting than these fixed expenses was the financial exploitation to which these travelers were subjected—specially in the early days of emigration—in Beirut and intermediate ports such as Marseilles. In announcing the lifting of restrictions on emigration from Mount Lebanon, the official gazette, Beirut, noted on March 18, 1899, that now “Lebanon[ese] fellaheen . . . can go anywhere they like without falling in the traps which used to be set for them by smugglers who minded nothing but their own personal interest.”[26] Amin Rihani, a contemporary Lebanese writer, satirized the financial plight of emigrants in his novel The Book of Khalid. Writing of Shakib and Khalid, two emigrants who arrive in Marseilles from Beirut, Rihani muses:

Even after all this exploitation, Lebanese immigrants arriving at Ellis Island had in their possession—on average—$31.85.[28] Adding the tangible numbers alone—and there were many hidden costs that are hard to quantify—we find that an average peasant started out of Beirut or Tripoli with a $63 purse. If we throw in some estimates of intangibles such as bribes and food, the figure could go as high as $80, or close to 2,500—piasters—the salary of a policeman or the tuition at a boarding school for children of the elite in Lebanon.They were rudely shaken by the sharpers, who differ only from the boatmen of Beirut in that they . . . intersperse their Arabic with a jargon of French. These brokers, like rapacious bats, hover around the emigrant. . . . From the steamer, the emigrant is led to a dealer in frippery, where he is required to doff his baggy trousers, and crimson cap, and put on a suit of linsey-woolsey and a hat of hispid felt. . . . From the dealer of frippery, . . . he is taken to the hostelry, where he is detained a fortnight, sometimes a month. . . . From the hostelry to the steamship agent, where they secure for him a third-class passage on the fourth-class ship across the Atlantic.[27]

Where did emigrants come up with these sums of money for the financially arduous journey? In the pioneering days of emigration (1880s to 1890s) peasants mortgaged their land, borrowed from relatives, sold jewelry, got loans from richer neighbors. Tannous Abu Dilly, from the village of ‘Ayn ‘Arab, was one of those “neighbors” who loaned many people their fares to the United States. While many repaid their loans on time, others defaulted, and Tannous traveled to their towns overseas to collect some money from them.[29] Even in later years (1900–1914), when emigrants were sending back to Lebanon money and steamboat tickets for relatives to join them in their endeavors, some families had resort to older means to finance their journeys. One woman, Skiyyé Sabha Samaha, wanted to take her son and rejoin her husband in the United States. She had to sell all her jewelry and borrow 20 liras ($65) from her husband's aunt in Lebanon to finance the trip.[30] Regardless of how peasants obtained the money, it is clear that it made immigration to the Americas a possibility that could not have been entertained before the 1880s.

More tellingly, the figures we reviewed above lead us to the conclusion that most emigrants from the Mountain were poor but not destitute. This conclusion in turn brings us face to face with another explanatory part of the puzzle of emigration—namely, peasants were not seeking financial salvation, but rather financial amelioration. The generation of peasants (born after 1860) which was capable of leaving Lebanon was also facing new financial realities. Having grown up in the fairly prosperous times of the 1860s and 1870s, this generation had come to expect that they could at least maintain, if not improve on, the standard of living of their parents. Yet, by the 1880s it was growing difficult to maintain these expectations. Silk prices were stagnating, the population was increasing dramatically, and land was becoming more dear.

By the time children born after 1860 had come of age, silk had been established as a crop of unprecedented importance within the economy of their families. If, as one contemporary commented in 1879, “the majority of [arable] lands in Mount Lebanon were covered with mulberry trees,”[31] then it only follows that the majority of the peasants' income derived either directly or indirectly from silk. Some numbers will serve to illustrate this point. In 1879 silk cocoons accounted for over 38 percent of the total income of the Mountain. Only wheat, which brought in about 21 percent of Mount Lebanon's income, came close to approximating the financial preeminence of silk. In later years this gap between silk and other products only yawned. For example, in 1906 in the district of Metn, silk provided approximately 82 percent of the total revenue.[32] That same year the inhabitants of Dardoreet, a Maronite village in the Shūf district, made 173,320 piasters from their silk crop, while olive oil brought them only 12,000 piasters, and the value of their sheep did not exceed 6,250 piasters. In Mount Lebanon as a whole, silk accounted for an income of a little over 42 million piasters, while the sale of olive oil and the potential value of sheep together amounted to no more than 29 million piasters. In other words, in 1906 the silk crop made up—on average—60 percent of the peasant family's income. Of course variations existed within this general scheme. Residents of areas that heavily favored silk—like the Metn, Kisrawan, and Shūf districts—naturally obtained a greater share of their annual income from the culture of the silkworm. Yet, the preponderance of mulberry trees in all the regions of Mount Lebanon made silk an indispensable source of income for the majority of peasant families during the second half of the nineteenth century. In fact, by the early 1900s, silk was providing, directly and indirectly, 72 percent of the peasantry's revenues obtained from the production of goods.[33]

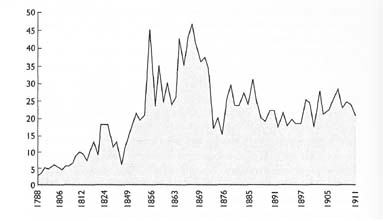

Even as dependence on silk had grown enormously, prices of this cash crop had begun an irreversible downward trend. Figure 2 demonstrates this problem, which plagued the “baby boomers” of the 1860s. While the prices of one oka of silk cocoons had been catapulted by European demands during the 1850 and 1860s from 8 to 40 piasters and above, the 1880s saw a reversal of that trend. Beginning with the collapse of the market in 1875, and despite a brief recovery in the mid-1880s, the price of silk hovered around a meager 22 piasters per oka. This depression in prices derived from the strong entry of China and Japan into the worldwide silk market. Cocoons from these two countries tended to be of better quality and even cheaper than the Lebanese product. This entry of East Asian producers was due in large part to the opening of the Suez Canal, which had cut the distance between London and Bombay in half and thus brought down transportation costs for shipments between East Asia and Europe.

Figure 2. Price (in piasters) of on oka of silk cocoons. Figures from Gaston Ducousso, L'Industrie de la soie en Syrie. (Paris: A. Challemel, 1913; Dominique Chevallier, La Société du Mont Liban à l'époque de la révolution industrielle en Europe. (Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1971); AE CC, Correspondance commerciale, 1831-1898.

In addition to the lower prices which silk was bringing in, the young generation of peasants had to deal with a growing uncertainty in the success of crops. The production of silk was never of a stable nature, yet this fluctuation became more pronounced in the second half of the nineteenth century. For instance, after a bumper crop in 1866, the number of cocoons harvested in the Mountain plummeted to less than one third of the normal yield four years later. Similar, albeit less severe, setbacks occurred in 1876, 1877, 1879, 1885, 1891, 1895, and as late as 1909.[34] These crises were due to several factors, first among which was the quality and source of the silkworm eggs. According to the French consul general, “It has been several years now [1868] that the silkworm eggs coming from Syria have not succeeded [in producing silkworms].” Because of this failure and the greater demand for silkworm eggs, “individuals leave every year to buy [silkworm eggs] in Egypt, Cyprus and Candi [Lombardy].”[35] However, this solution was far from perfect since those types of eggs were bred in different environmental settings that made them rather unsuited to either the climate of Mount Lebanon or the tougher type of mulberry leaves found in its hills. As a result they never provided yields equal to those given by indigenous eggs before the 1850s. For example, while, in 1854, 25 grams of local eggs produced close to 54 kilograms of cocoons, by the 1880s a box (25 grams) of Japanese eggs yielded a bare 29 kilograms. In later years, matters got only worse for the Lebanese peasants. Between 1906 and 1911 the average yield of 25 grams of eggs in Mount Lebanon was 22.733 kilograms of cocoons. When this Lebanese yield is compared with the lowest yield in France, where the same amount of eggs hatched 44.4 kilograms of silkworms cocoons, it becomes ever more clear that the Lebanese peasants were experiencing disappointing returns on their investments.[36]

Lower prices and meager yields were not the only discouraging economic signs facing younger farmers after the 1880s. A mushrooming population was increasing the pressure on the already strained resources of the Mountain. While exact figures for the number of people who lived along the rugged edges of Mount Lebanon still elude us, we can paint a broad picture of the population trends. In summary, many more children were born, and lived through adulthood, after 1860 than did before that year. Between 1783 and 1860, the population of the Mountain had risen from 120,000 to only about 200,000, or an increase of about 67 percent in seventy-seven years.[37] Only two decades later, the population had leapfrogged to 280,000, and by 1913 there were 414,800 people living in the Mountain. Even if we do not include the estimated 155,600 emigrants residing in North and South America, the population jump still amounts to 107 percent in the fifty-three years after 1860, or almost double the growth experienced before that year.[38]

Various factors coalesced to bring about this change. Most obvious—and perhaps most crucial—is the fact that the Mountain experienced no violent upheavals between 1860 and the onset of World War I. In comparison, the thirty years preceding 1860 saw two major civil wars, a number of peasant revolts, a revolt against the Egyptian occupation forces, and famines. During that time over ten thousand people died.[39] Peace during the Mutasarrifiyya period also allowed for medical improvements, which subsequently contributed to the population increase. For instance, in 1881 the “Lebanese Administration” launched a program of inoculation against smallpox—a disease that was ravaging the districts neighboring Mount Lebanon—and by the end of the century over half the population had been immunized.[40] In addition to these measures, Mount Lebanon was effectively quarantined during outbreaks of diseases in Beirut or surrounding territories. In one such instance, in the summer of 1900, a plague had beset Beirut, which prompted the Mutasarrif Naoum Pasha to prohibit any contact between the Mountain and the city. Along with the local residents who were trapped by this quarantine was the French consul general de Sersi, who demanded special permission to leave Beirut for the mountains. Much to the chagrin of the consul, who fumed and threatened, the Mutasarrif rejected his request on the premise that he was human like all the other residents of the city and thus could be a carrier of the disease.[41] Finally, a high birth rate among the peasants was partially responsible for driving the population figures higher. For example, in an 1847 dispatch the French consul general Bourée estimated that on average a Maronite family had 6.2 children, while its Druze counterpart had 4.6 children.[42]

As the population grew by leaps and bounds, land became more dear. One observer wrote of the 1890s, “It got to the point where what was divided among the heirs was no longer a piece of land but the thick branches of mulberry trees . . . and the olive tree crop.”[43] Even allowing for literary license the point remains valid. Two comparative numbers will suffice to prove this contention. During the 1864 census of Mount Lebanon, it was estimated that 125,238 dirhems of land (176,586 acres) were under cultivation.[44] By 1918 the amount of land exploited for agriculture was a little over 140,000 dirhems (197,600 acres).[45] In total, then, the increase was barely 15,000 dirhems (20,889 acres), which represents an anemic additional 11.8 percent of fields to plow, plant, and harvest. The meagerness of this change becomes even more pronounced when we correlate it with the increase in population. If in 1864 an average peasant representing the 200,000 inhabitants of the country had access to 0.88 acres of land, fifty years later that hypothetical peasant would have to contend with half that plot. In other words, as hard as peasants worked to hold on to land, their efforts were frustrated by their own children, who were growing up to find that little land had to be subdivided among too many male siblings.[46] The effect of such intense population pressure on the limited resources of the Mountain was to drive land prices skyward, beyond the reach of our average peasant.

Pulling these various elements together, we can begin to draw the picture that faced the post-1860 generation of peasants. Having grown up in relative prosperity, these peasants were facing limitations that threatened to send them economically a few steps backward. At the end of the 1880s silk was no longer the golden crop it had been ten or twenty years before. At the same time, rising land prices and shrinking inheritance combined to make the economic future bleak. So it was that many peasants arrived at the year 1887 with a sense of malaise. They did not have much land, and what little they had did not promise to make them a “good” living. For those seeking to simply make a living (have money for food, clothes, and a modest shelter), there were few jobs. They could work as servants in the cities (about four thousand were doing so in 1884), they could join the gendarmerie (another few hundred opted for that), they could hire out as agricultural laborers, or (if they were women) they could work in the silk factories. Although some villagers did migrate seasonally to neighboring cities (like Aleppo and Bursa), these areas provided limited opportunities as they were experiencing their own economic crises. Aside from the fact that none of these avenues offered much income, they also meant leaving the land or at least losing status as an independent farmer. In either case, the result was not socially gratifying, to say the least. These drawbacks made a large number of peasants look for other ways out of their dilemma—namely, how to make enough money quickly to guarantee their status as landowners and not slip into the ranks of the landless laborers. About the only option that appeared on the economic horizons was emigration.

At first (in the 1880s) few hardy souls ventured along this uncharted path. In tens they left the Mountain to take a steamboat somewhere across the sea—where, they were not exactly certain. We are no more certain of how they would have heard about financial opportunities in the Americas.[47] However there were several possibilities. For one, we know of an Ottoman pavilion at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibit of 1876 and of a couple of Lebanese who were in attendance. One can imagine the stories they brought back about the “wonders” they saw there and how these stories—properly embellished and spiced—would have meandered along with muleteers across the Mountain. Or it is conceivable that at the port of Beirut they were not only unloading French sugar and English cloth but also “strange” stories of South America and its abundant riches. Schools (which were proliferating after 1860, and most notable of which was the American institution known then as the Syrian Protestant College) and the handful of newspapers and few books that were published in Beirut and its environs may very well have carried some tales of America, emigration, or both. (We certainly know that to have been the case in the 1890s and later). Some members of the burgeoning foreign community in Beirut—who summered in Mount Lebanon to escape the heat and humidity—may indeed have pontificated about the civil war in America or disdainfully mentioned the European migration to that “land of opportunity.” Ultimately, it could have been the few Lebanese who traveled to Paris, London, or Rome who brought back in their cultural baggage news of these “new” lands. In any or all of these cases, the result was that those who were boarding the ships at Beirut vaguely knew to go to “Amirka,” south or north.

It did not take long for these adventurers to write back letters laden with praise for the lands they discovered. Michel H. recounted one such letter, which prompted him to emigrate to the United States. “In 1892 not many people were going to America. This family went to America and they wrote back . . . [to say that] they made $1000 [in three years]. . . . When people of ‘Ayn ‘Arab saw that one man made . . . $1000, all of ‘Ayn ‘Arab rushed to come to America. . . . Like a gold rush we left ‘Ayn ‘Arab, there were 72 of us.”[48] Such (tall?) tales of easy money would have probably been little more than amusing anecdotes for the folks back home were it not for the evidence of newfound wealth. In the first years of emigration, letters would sometimes come with a money order for a few hundred dollars. But by the 1890s emigrants were making the journey back to get married, see the family, take a rest, and flaunt their financial fortunes. They came dressed to the hilt, wearing gold watches and Panama hats. Tafeda Beshara vividly remembered her aunt's first visit back to Rachaya: “Well, I had no picture of America. . . . But my aunt had already been there and she made a lot of money peddling so she went back for a visit. Ho! She was dressed and fixed and what—she was in her prime then, you know—. . . silk and ostrich feathers and diamonds and a watch pinned to her chest. That picture of her is just priceless. . . . Oh she came back and she had the money.”[49]

Memories of coming back and “having money” were common enough to become part of the fiction of the period. In one such story, Mikhail Nu‘aymi wrote about a peasant named Khattar whose fiancée (Zumurrud) was seduced by the sight and status of a “cocoo clock” (grandfather clock) into eloping with the emigrant who had brought it into the village. In the aftermath of the scandalous event (which gave Zumurrud's father a heart attack and would go on to claim a few other victims), Khattar was left pondering his life and future. One day while plowing his plot, he suddenly stopped, looked around, and thought to himself, “Until when Khattar, until when? You have buried in this soil twenty years of your life, and what has it given you? . . . It is shameful that a man like Faris Khaybir [the man with the “cocoo clock”] could steal your love, and [he] would not have stolen it without his money for which he had traveled the seas. So what ties you to these rocks? . . . And Khattar went to America.”[50] Despite its heavy-handed moralizing, Nu‘aymi's story still manages to depict at least one impact of the return of moneyed emigrants to the villages and provides us with an image of one of the engines of emigration.

But the emigrants' most lasting impression was of the “American home,” the old house renovated and expanded. Dr. Carslaw of the Foreign Mission of the Church of Scotland observed these improvements in his report of 1894: “Houses were having the old clay roofs taken off, and new roofs of Marseilles tiles put on. . . . Eighteen years ago there was not a tiled roof in the whole district.”[51] Nine years later the effect was even more dramatic. In the words of U.S. consul general Ravndal, “A village in the most remote parts of the Lebanon . . . has . . . at least 2 or 3 new houses with tiled roofs and . . . even whole villages have been thus constructed.”[52] These blushes of wealth, which could be seen from all over the village and from afar, attracted the attention and excited the imagination of those who had remained in the village and who were still pondering how to secure their future as farmers. Consequently, the tens turned to hundreds, and by the turn of the century they were followed by thousands who left the Mountain every year.

Facilitating the desire to acquire money was the creation of a trodden path to the mahjar. By the turn of the century, the adventures and uncertainties of yesteryears were replaced by a network of people that extended from the villages all the way to the cities and towns of the Americas. All along this web information was passed back and forth about work opportunities and travel pitfalls. Word would be sent back about the best way to avoid increasingly strict immigration control in the United States (travel to Mexico and cross overland into Texas), the good and bad hotels along the way, and whom to ask for on arrival in a town. Even impromptu courses in highly abridged English (“thank you,” “please,” “yes,” and “no”) were given on the boat to teach these future peddlers the essence of selling trinkets and baubles to middle-class women in the cities and to farmers out on the plains of the United States.[53] While troubles still accompanied the emigrants, these tips helped smooth the trip and convince the reluctant peasant to undertake the immense voyage across the ocean.