Puns: Verbal and Figurative Machines

It's true literally and in all the senses.

— Arthur Rimbaud

At certain moments even spelling-books and dictionaries seemed to us poetic.

— Novalis

When citing influences on his artistic work, Marcel Duchamp singles out the event of attending a performance with Francis Picabia and Guillaume Apollinaire of Raymond Roussel's Impressions of Africa in 1911. (Roussel [1877–1933] mechanized art-making and language in this book.) He describes this event as follows: "It was tremendous. On the stage there was a model and a snake that moved slightly—it was absolutely the madness of the unexpected. I don't remember much of the text. One didn't really listen. It was striking" (DMD, 33).[29] When questioned by Cabanne whether the spectacle struck him more than the language, Duchamp responded: "In effect, yes. Afterward, I read the text and could associate the two" (DMD, 34). The impact of Roussel's spectacle cannot be summarized purely in terms of its outlandish visual, mechanical, and

nonsensical character; equally significant is Duchamp's observation that the dissociation of the visual and linguistic aspects of the spectacle can be reassembled upon the reading of the text. Hence the text retrospectively illuminates the image, and in doing so, displaces the priority of both the visual performance and the text.

This anecdote becomes significant once it is understood that Roussel's interest in the mechanisms of language and his "secession" from literature corresponds to Duchamp's challenge to, and final abandonment of, painting.[30] Later, commenting on The Large Glass, Duchamp underlines the fact that the notes contained in The Box of1914 are essential to the visual experience of the work: "I wanted that album to go with the Glass, and to be consulted when seeing the Glass, because, as I see it, it must not be 'looked at' in the aesthetic sense of the word. One must consult the book and see the two together. The conjunction of the two things removes the retinal aspect that I don't like " (DMD, 42–43; emphasis added). This statement elucidates Duchamp's earlier assessment of Roussel's Impressions of Africa by defining his antiaesthetic position as a strategic interplay: the active dissociation and reassemblage of the visual and textual elements. Duchamp's expressed bias—that as a painter it was much better to be influenced by a writer than by another painter—indicates his effort to reinterpret art as "intellectual expression." His concomitant rejection of painting as "animal expression" reflects his project to overcome the purely visual (retinal) constraints of a medium that reduces the artist to silence, rendering him: "dumb as a painter."[31] This is not because the verbal is more "intellectual" than the visual; rather, it is the possibility of their interplay that arouses his curiosity. Duchamp's appeal to Roussel, as an answer to the crisis he perceives in painting, reflects his interest in the conceptual experiments with language through which Roussel challenged the very limits of literature.

Without being familiar with Roussel's writing methods—his experiments generating wordplays from sentences—Duchamp specifies his influence as follows:"But he gave me the idea that I too could try something in the sense of which we were speaking; or rather antisense . . . . His word play had a hidden meaning, but not in the Mallarméan or Rimbaudian sense. It was an obscurity of another order" (DMD, 41; emphasis added). The "antisense" that Duchamp speaks of here has neither

a negative sense nor suggests a hidden meaning, such as we find in the poetic experiments of Stéphane Mallarmé or Rimbaud. For Duchamp, "antisense" refers to Roussel's investigations of language as a mechanism that can generate "poetic" associations and to Jean-Pierre Brisset's analysis of language through puns.[32] Hence Duchamp's efforts to "strip" language "bare" of meaning, and thus explore its creative potential through "non-sense" (DMD, 40). This "linguistic striptease" liberates language from sense in order to open its field to the play of nonsense, that is, to the contextual generation of a variety of senses.

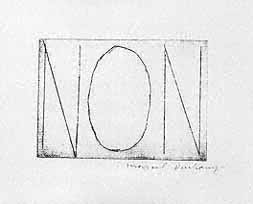

In order to elucidate what Duchamp means by nonsense, we turn to First Light (Première Lumière, 1959) (fig. 36), a work that explores the contextual production of pictorial and literal meaning through puns. First Light is a blue and black etching depicting the word NON, made to illustrate Pierre André Benoît's poem entitled "Première Lumière." What is striking about this etching is the fact that its status as an image or as a text is unclear. Are we dealing with the illustration of a poem, or merely the image of a title acting as a commentary on the official title? The relation of the image of the word NON and the title First Light is opaque as long as we do not shed light on this image with a pun. NON (both a negation and a particle of the French negative ne . . . pas ) is a pun on nom (meaning name or noun, in French). The "first light" that is cast on the word NON (orNOM ) reveals its fragile and conditional existence as a noun. NON hovers precariously between negation (a particle that brackets and derealizes

Fig. 36.

Marcel Duchamp, First Light (première lumière),

1959. Etching, 4 13/16 x 5 7/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise

and Walter Arensberg Collection.

the existence of another term) and nomination (a word that entitles an object or person).[33] The punning ambiguity between negation and nomination is further complicated by what appears to be the lack of reference to the title of the work First Light. However, once we recall Duchamp's subtitle to Given, "the illuminating gas" (a pun on gaze), it becomes clear that the discrepancy between the title and the image (which is like a title) reflects the difficulty of illuminating the image.

Duchamp's effort to reproduce Benoît's "creation" in this "literal" image results in the discovery that there are only "non-words" and "non-images," since neither the name (as image) nor the image (as a negative) has any intrinsic essence. Despite their nominative and essentialist character, the meaning of names, like those of images, depends on their context. Thus, both title and image are nonsensical to the extent that their ability to refer relies on the circuit of their interplay. Like Gertrude Stein, Duchamp discovers that "We must get rid of nouns, for objects are never stable."[34] The effort to provide a literal representation generates an excess of sense that spills out from the verbal into the visual domain, echoing Rimbaud's pronouncement: "It's true literally and in all the senses." Nonsense in this context no longer signifies "non-sense," but instead a gesture whose contextual character strategically stages and engages all the different senses.

Duchamp's active use and understanding of nonsense as a hinge between the linguistic and the visual defies the simplistic reduction of nonsense to a purely "literary" procedure. When Duchamp speaks of the poetic value of words, the "poetry" in question encompasses sound, wit, rhyme, and figurative considerations:

I like words in a poetic sense. Puns for me are like rhymes. The fact that "Thaï's" rhymes with "nice" is not exactly a pun but it's a play on words that can start a whole series of considerations, connotations and investigations. Just the sound of these words alone begins a chain reaction. For me, words are not merely a means of communication. You know, puns have always been considered a low form of wit, but I find them a source of stimulation both because of their actual sound and because of unexpected meanings attached to the inter-relationships of disparate words. For me, this is an infinite

field of joy—and it's always right at hand. Sometimes four or five different levels of meaning come through.[35]

Duchamp's interest in language is neither communicative nor expressive. His preference for puns, which he compares to rhymes, demonstrates his acceptance and use of chance. A pun plays on words that are similar in sound but different in meaning, just as a rhyme arbitrarily couples together two different verses. The sound of words produces a "chain reaction," in which "different levels of meaning come through," thereby producing an "infinite field of joy." As Duchamp warns us, the pleasure generated by these wordplays cannot be construed merely in terms of wit. Rather, for Duchamp, this pleasure is endemic to his description of intelligence: "There is something like an explosion in the meaning of certain words: they have a greater value than their meaning in the dictionary" (DMD, 16). In describing the meaning of intelligence, Duchamp is, in fact, distinguishing sense from nonsense. The intelligence that he has in mind is an intelligence of the tongue, an explosion of meaning whose verbal and figurative character defies the referential character of language. By situating intelligence, "right at hand," that is as a figurative principle generated through the play of puns, Duchamp stretches the logical limits of rational intelligence. His exploration of the plasticity of language, hinged upon its verbal and figurative associations, inscribes in his work a pleasurable dimension, that of an eros generated through their interplay.

Although Duchamp speaks of liking words in a poetic sense, his examples demonstrate that the poetry in question is conceptual, rather than "literary." Tristan Tzara's remark that "the poetic work has no static value, since the poem is not the end of poetry: the latter can perfectly well exist elsewhere," echoes Duchamp's own efforts to recover the plasticity of language and images.[36] As Duchamp explains in reference to The Large Glass : "I refer to purely mental ideas expressed as part of the work but not related to any literary allusions."[37] This denial of the literary captures Duchamp's understanding of his work as a new kind of language, one which rejects both literary and pictorial conventions, as well as the conventional meanings of words and images.[38] Michel Sanouillet considers Duchamp's strategy an effort to sunder the relation of expression to expressive content:

Once words are thus emptied and freed through the sudden visible strangeness of their internal structure or through a new association with other words, they will yield unexpected treasures of images and ideas. The adventure of language thus unfolds differently from the striving for style, which pursues freshness and visual and auditory sensations. The principle is that a word too much in view, like a landscape, loses its savor, wears itself out, and becomes a commonplace. The interest which its semantic content gives rise to is reduced to the vanishing point. It is only and precisely at the point where the stylist in search of the picturesque gives up that Duchamp intervenes. Once the container is stripped of its content, the word as assemblage-of-letters assumes a new identity, physical and tangible, as a surprising interpreter of a new reality. (WMD , 6)

Sanouillet's eloquent description of Duchamp's "adventure of language" suggests that this adventure applies equally to words and images, insofar as their meaning has been petrified and rendered commonplace through repetitive usage. Hence, Duchamp's experiments with puns emerge not merely as examples of self-expression, a gratuitous appeal to the private joke, but also as significant efforts to rethink the nature of both poetic and visual language.

Duchamp's interest in visual and verbal puns is expressed explicitly in his ready-mades. The selection and visual display of the ready-mades also involves the naming of the object, since the ready-made becomes a work of art by Duchamp's performance, by his declaration that it is such. Thus the title of the ready-made inscribes the object into a temporal and linguistic dimension. In his statement "Apropos of 'Readymades'" Duchamp explains: "That sentence, instead of describing the object like a title, was meant to carry the mind of the spectator towards other regions, more verbal" (WMD, 141). These titles are the expression of Duchamp's poetic concerns with language, his dynamic conception of words not merely as bearers but also as producers of meanings. Commenting on the title of the Nude, Duchamp remarked that it "already predicted the use of words as a means of adding color, or shall we say, as a means of adding to the number of colors in a work."[39] He also considered words in visual terms as "photographic details of largesized objects." Arturo Schwarz observes

that Duchamp was motivated by the desire "to transfer the significance of language from words into signs, into a visual expression of the word, similar to the ideograms of the Chinese language."[40]

Thus Duchamp's act of nomination of the ready-made is not a gesture of closure, that is, of framing the visual referent by a verbal one. The punning title of the ready-made stages the active interplay of phonetic and figurative elements, thereby engendering the destruction and dissemination of its objective character. Duchamp's understanding of words as mechanisms that may trigger a variety of associations enables him to manipulate the literal object-ness of the ready-mades. Like its title, the ready-made is more or less an object. Its meaning and existence as an object are validated by the act of nomination, but the title fractures the object to the extent that its literal and figurative dimensions interfere and condition our perception of the object. The title thus functions not purely as name but as a signifying material whose phonetic redundancies with respect to the object set up a relay of significations that displace and scramble the identity of the object. The redundancies and alliterations that come to define the object expend its objective character through nonsense.

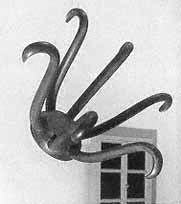

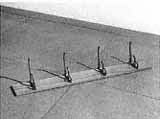

A quick review of Duchamp's ready-mades, a bottle rack, Bottle Rack (Egouttoir; 1964 version [original version of 1914, lost]) (fig. 37), a hat rack, Hat Rack (Porte-chapeaux; 1964 version [original version of 1917, lost]) (fig. 38), and a coat rack nailed to the floor, Trap (Trébuchet; 1964 version [original version of 1917, lost]) (fig. 39), reveal his interest in

Fig. 37.

Marcel Duchamp, Bottle Rack (Egouttoir),

1964 (original version of 1914, lost). Ready-

made: galvanized iron, height 25 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Fig. 3 8.

Marcel Duchamp, Hat Rack (portechapeaux),

1964 (original version of 1917, lost). Assisted

ready-made: hat rack suspended from the

ceiling, height 9 1/4 in., diameter at base 5 1/2

in. Galleria Schwarz, Milan.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

Fig. 3 9.

Marcel Duchamp, Trap (trebuchet), 1964

(original version of 1917, lost). Assisted

readymade: coat rack nailed to the floor.

Galleria Schwarz, Milan.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

exploring how physical displacement may be translated into logical and artistic paradoxes. The visual suspension of the bottle rack and the hat rack highlights their ambiguous status as ordinary objects. Hung from a support, they become inaccessible as functional objects. The coat rack, on the other hand, is rendered functionally redundant by being nailed to the floor. Floating in the air as if unattached, the bottle rack and hat rack draw the viewer's attention to the temporal, as well as visual, meaning of suspension—suspension as a brief interruption, or delay. Playing on both meanings of suspension, Duchamp inscribes a temporal interval into the visual dimension. In doing so, however, he reveals the nature of his intervention to be that of an intellectual fact, one which may "strain a little bit the laws of physics," to use his own terms. As he observes to Francis Roberts: "Even gravity is a form of coincidence or politeness, since it is only by condescension that a weight is heavier when itdescends than when it rises."[41]

Three of the ready-mades—the bottle rack, hat rack, and coat rack—are frameworks on which articles are hung, sharing the designation of rack (porte, as in the French porte-bouteilles porte-chapeau, and porte-manteau. ) Not only has Duchamp selected three objects that act as bearers for other objects porte (from porter, which is also door in French) but, lest his audience misses the joke, he has provided us with a further verbal clue with the coat rack (porte-manteau. ) A portmanteau is an artificial word construction that packs two meanings into one word. The coat rack (porte-manteau ) reveals Duchamp's understanding of ready-mades, not as actual objects but as porte-parole (spokesman or mouthpiece in English), that is, as bearers of speech or as mechanisms for the production of linguistic and visual puns. The visual suspension of these ready-mades reveals their affinity to puns, since puns suspend conventionalmeaning by creating an interval that delays their capacity to refer, by being objectified or "made" either into words or into images. As bearers of other objects and other meanings these ready-mades embody through their visual characteristics the mechanical displacements operated through puns.

In order to elucidate how puns function—not as ordinary words but as utterances—we return to Duchamp's coat rack Trap, which instead of being physically suspended is nailed to the floor. Keeping in mind Arturo Schwarz's observation that a "Ready-made is sometimes a pun in three-

dimensional projection," this work helps us clarify the relation of linguistic and visual puns in Duchamp's oeuvre. The visual meaning of this work, that of the physical displacement of the coat rack, remains quite opaque as long as we do not consider the conceptual displacement enacted by the title. The title of this ready-made, Trap (Trébuchet), is phonetically identical to the French chess term trébucher, meaning to "stumble over," thus suggesting both the kind of impediment (trap) and the kind of movement (stumbling) that puns engender. Susan Stewart has noted that puns "trip us up," and that they are an "impediment to seriousness" since they split the flow of meaning and events in time.[42] Yet, by making us stumble, puns invite us to think about language in a new way—not as a static object but as a mechanism generating movement. Considered in these terms, the so-called "poetic" or "creative" aspects of language emerge as "ready-made," to the extent that a pun is like a switch that mechanically enables us to discover the creative potential of language.

If Duchamp's work is a "pressure responsive mechanism" (to use Antin's expression), the linguistic and the visual elements can be considered as "trap doors" that open up kinetic possibilities. As Duchamp observes, "the trap door, and by its falling open/ the trap door effects the instantaneous pulling / of the carriage (through the system of pull cords.)" (Notes, 97).[43] The coat rack in Trap, on which clothes used to hang neatly in a row like words in a sentence, is a mechanical trap that unhinges our concepts both of language and of vision. The "linguistic trap" is the idea or rather conceit that "art could free itself from language" and "come to occupy a kind of neutral space between thoughts."[44] This illusion, that art can transcend language, is based on the mistaken assimilation of linguistics to literature—an assimilation that, in Antin's view, denies its conceptual and kinetic nature. The other trap in question is the "retinal" or "visual shudder," the illusion that an image or an object needs no further illumination since it is autonomous from language.

Duchamp's interest in puns as machines whose nonsensical character challenges the conventions of meaning is echoed by his Dada contemporaries' efforts to revolutionize both language and artistic modes of expression. For instance, Tristan Tzara's Manifeste de Monsieur Anti-pyrine and Manifeste Dada (1918) are neither purely discursive nor poetic artifacts but instead efforts to critique language itself as the purveyor of a logical

and metaphysical worldview. By setting into play the visual, graphic, and acoustic properties of language, through experimental typography that disrupts the conventional organization of words on the page, these manifestos challenge our presuppositions about the communicative or informational function of language. Like Hugo Ball's and Richard Huelsenbeck's optophonetic experiments, these texts are visual and acoustic performances that operate at the very limits of language. These experiments with language, however, must be distinguished from Duchamp's own discovery of puns as verbal and poetic machines. The specificity of the Duchampian project lies in the systematic elaboration of puns as embodied objects whose concrete identity is disseminated through verbal and visual reproduction. Instead of testing the limits of language, as do his Dada contemporaries, Duchamp uncovers within ordinary language a creative potential that reflects his understanding of it as a generative mechanism. As linguistic ready-mades, puns act like switches between common sense and nonsense, thereby technically reactivating and enriching their common usage. Their meaning is transitive, reflecting less their specific content than their strategic and contextual nature as utterances. By positing puns as mechanical prototypes, Duchamp invites the spectator to envision language itself in the mode of mechanical reproduction. Instead of just restricting himself to the nominal properties of ordinary objects, however, Duchamp proceeds to explore through the ready-mades their peculiar redundancy as both artistic and unartistic gestures.