Chapter 1

The Casbah and the Marine Quarter

A whitish blur, cut into a trapezium, and dotted with silver sparkles—each one of them a country house—began to be drawn against the dark hills: this is Algiers, Al-Djezair, as the Arabs call it. We approach; around the trapezium, two ocre-colored ravines define the lower edges of the slopes, and shimmer with such a lively light that they seem as though they are ends to two sun torrents: these are the trenches. The walls, strangely crenellated, ascend the height of the slope.

Algiers is built as an amphitheater on a steep slope, such that its houses seem to have their feet on the heads of others. . . . When the distance gets smaller, we perceive amid the glare the minaret of a mosque, the dome of a sufi convent, the mass of a great edifice, the casbah.

Théophile Gautier, Voyage pittoresque en Algérie

The term casbah refers to the ancient core of Algiers, the triangular-shaped town carved into the hills facing the Mediterranean (Fig. 2).[1] The sea forms the base of the triangle; a citadel is at the triangle's summit. It is defined on the south by Square Port Said (formerly Place d'Aristide Briand, earlier Place de la République) and Boulevard Ourida Meddad (formerly Boulevard Gambetta), on the west by Boulevard de la Victoire and the Palace of the Dey, on the north by Boulevard Abderazak Hadad (formerly Boulevard de Verdun), and on the east by Boulevards Ernesto Che Guevara, Anatole France, and Mohamed Rachid (formerly all three comprising Boulevard de la République, ear-

Figure 2.

Plan of the old city, c. 1900, showing the casbah (1)

and the Marine Quarter (2). For a more

detailed plan of the street network, see Fig. 14.

lier Boulevard de l'Impératrice), which define the waterfront. The town's border being fixed by fortifications, it developed vertically into a high-density settlement. Its striking urban aesthetics were defined by the interlocking masses of white, geometric houses with roof terraces opening onto the bay.[2] As will be traced in the following chapter, under French rule Algiers extended along the coastline, gradually filling in the valleys and climbing up the hills in the hinterland.

Historic Development

The settlement was founded by the Arab Zirid dynasty in the tenth century and named al-Jaza'ir ("the islands") in reference to the islands facing the waterfront. Its fate locked to the rest of North Africa, it was ruled by successive Arab dynasties as a minor port until the sixteenth century, when it was made the capital of Algeria by the Ottomans.

A major turning point in the history of medieval Algiers was the recapture of Spain by Christians in the fifteenth century, which resulted in a wave of Muslim refugees to Algiers. The Muslims from Spain contributed further to the "Western" Islamic taste that already character-

ized the artistic and architectural culture, but perhaps more important to the livelihood of the city they established themselves as corsairs, or pirates, in response to the reconquista , the Spanish expulsion of Muslims to North Africa. To suppress the corsair activity, Spain imposed a levy on Algiers in 1510. With support from powerful Ottoman corsairs (first Aruj, then Khayr al-Din), however, the Spaniards were driven away and Algiers became an important port of the Ottoman Empire in 1529. Piracy remained the main income-generating activity for the city, providing for all sections of the population but also provoking frequent attacks from Europe.[3]

Not much is known about pre-Ottoman Algiers. The walls of the Arab settlement might have corresponded to the later Ottoman walls, but the density was considerably lower than that of the post-sixteenth-century period. The Ottoman walls ran continuously for 3,100 meters and enclosed the town from all sides, including the sea. They were dotted with towers and had five gates: Bab Azzoun to the south, Bab al-Jadid to the southwest, Bab al-Bahr on the sea front, Bab Jazira on entry of the harbor, and Bab el-Oued to the north. The streets leading from the gates met in front of the Ketchaoua Mosque. The citadel at the highest point on the fortifications was built in 1556.[4]

The road connecting Bab el-Oued to Bab Azzoun divided Algiers into two zones, in accordance with André Raymond's notion of "public" and "private" cities: the upper (private) city, called al-Gabal or "the mountain," and the lower (public) city, called al-Wata or "the plains."[5] The lower part developed as an administrative, military, and commercial quarter (Fig. 3). It was inhabited mostly by Turkish dignitaries and upper-class families whose luxurious houses synthesizing Eastern and Western influences dotted the neighborhood. The Dar al-Sultan, or the Janina Palace, built in the 1550s as the residence of the dey, was also located in this area, together with the major mosques and the military barracks.[6] The souks (markets) and warehouses were concentrated along the main streets, with the al-Souk al-Kabir (the road connecting Bab el-Oued and Bab Azzoun), only 3 meters wide, standing out as the largest artery of Algiers. Commercial structures also provided accommodations for foreigners and "bachelors" from other parts of the country. The commercial zone was shaped according to concentrations of different merchandise, and merchant associations were strong and well organized.[7]

The upper city was comprised of approximately fifty small neighborhoods. As was typical of the decentralized Ottoman urban system

Figure 3.

View of the waterfront, c. 1830. In the foreground is the al-Jadid Mosque; to the right is

the al-Kabir Mosque. The Bab al-Bahr (Sea Gate) is to the left of the al-Jadid Mosque.

throughout the empire, every neighborhood was under the administrative responsibility of religious chiefs and qadis (judges), hence each community was controlled and supervised by its own leaders. The population was mixed. Old families with Andalusian and Moorish roots engaged in commercial and artisanal activities; kabyles formed the working class; Jews, who had three distinct neighborhoods in the upper casbah, were tradespeople. The presence of European consuls and businessmen, Saharans, and Christian slaves made the population of Algiers truly cosmopolitan.[8]

The street network—considered thoroughly inadequate and irrational by the French—demonstrated a clear and functional hierarchy, made up of three distinct types of thoroughfares.[9] It revealed a carefully articulated logic, a "system of filtered access."[10] The streets of the lower town, catering to commercial, military, and administrative functions, differed in their physical character and the concentration of their activities: they were lined with shops, cafés, and large structures, and crowded

with people and merchandise all day long, but especially during morning hours. The arteries leading to the gates were particularly prominent. The transversal roads that climbed to the upper town formed the second category; as straight as the topography permitted, they cut through the urban tissue and provided efficient communication between the two sections of Algiers. The neighborhood streets made up the third and the largest category. Narrow, irregular, often with dead ends, they accommodated the introverted lifestyle that centered around the privacy of the home and the family; their configuration also enabled the use of gates to close off a neighborhood in the evenings to ensure its safety (Fig. 4). Respect for privacy dictated the design of facades as well: windows and doors were carefully located to prevent views into the houses across the street. Neighborhood streets had the lightest circulation; they functioned instead as playgrounds for children, especially boys. The citizens of Algiers took great pride in the cleanliness of their streets , where, they boasted, one could sit on the ground, even to eat.[11]

The urban structure of Algiers, dominated by its short, crooked neighborhood streets, is a hallmark of the "Islamic city"—a problematic construction by European historians, which has been recently subjected to serious revision. Janet Abu-Lughod, the most convincing critic of this concept, has argued, nevertheless, that Islam shaped social, political, and legal institutions, and through them, the cities. She pointed out that gender segregation was the most important issue, and by encouraging it, Islam structured the urban space and divided places and functions.[12] To put it schematically, in the "traditional Islamic city," public spaces, hence streets, belonged to men, and domestic spaces to women.

Gender-based separate "turfs" prevented physical contact and relegated the lives of the women to their homes. Privacy thus became a leading factor and resulted in the emergence of an interiorized domestic architecture. Regardless of the family's income level or the size of the building, the houses of the casbah were organized around a court surrounded by arcades (Figs. 5 and 6). This was the center, indeed the "principal room," the setting for the "theater of work and women's leisure, for children's games."[13] Some houses had water fountains here, with water coming from the aqueducts that tapped the sources in the hills around Algiers.[14] Entrance to the court was indirect and achieved through several labyrinthine lobbies. The largest room of the entry level could be used by the man of the house to entertain his friends without interfering with women's activities. The upper floors contained the

Figure 4.

Street view in the upper casbah.

Figure 5.

Plans and section of a modest house in the casbah. (1) Basement floor

plan: A, room; B, cistern; C, laundry room; (2) first-floor plan: A, entrance

hall; B, vestibule; C, patio; D, portico; F, G, I, rooms; (3) a half floor between

the first and second floors, where the latrines are located; (4) second-

floor plan: J, kitchen; K, L, M, rooms; (5) plan of the terrace level;

(6) section through the courtyard (X—Y).

Figure 6.

Courtyard view from an upper-class house (Dar Aziza) in the casbah.

main rooms, all opening onto the arcade. A stairway led to the roof terrace, which often had a cistern to collect rainwater.[15]

Like the court, the terrace was an essential part of the house where women spent many hours of the day, working and socializing with their neighbors. The dense configuration of the casbah made it possible to pass from one terrace to the other and visit other homes without having to use the streets. The rooftops of the casbah functioned as an alternative public realm that extended over the entire city. In contrast to the interiorized court and the relatively contrived rooms, the rooftops opened up to the city, to the sea, to the world (Fig. 7). With the appropriation of this space by the women of Algiers, the casbah became divided horizontally into two realms: on the top, occupying the expanse of the entire city, were the women; at the bottom, the streets belonged to the men.

Algiers boasted religious and public buildings throughout. Right before the French conquest, there were about a dozen major mosques and sixty smaller ones.[16] The primary mosques, namely the eleventh-century al-Kabir (Fig. 8), Ketchaoua from 1612 (transformed into a cathedral in 1838), Ali Bichnin from 1632, al-Jadid from 1660, and al-Sayyida, perhaps the most elegant of all the religious buildings in Algiers and reconstructed in 1794, were concentrated in the lower section.[17] Nevertheless, the entire city was dotted with masjids (smaller prayer halls), endowing every neighborhood with its own prayer spaces. Minarets were placed strategically around the city so that the calls to prayer could be heard from every house. Religious schools were scattered throughout, as well as public fountains and hammams (baths). The management of all religious and public buildings was in the hands of the religious leaders, regulated by the waqf system.[18]

Mosques and religious schools were frequented by the male population, but the baths were used by women on special days reserved for them. Their outings included visits to the tombs of venerated figures, some inside the city walls, some outside. It was not uncommon to see small groups of women passing through the streets of Algiers, creating an "exotic" scene much cherished by the French.

When the French occupied Algiers in 1830, they found a dense, fortified town, nestled against steep green hills facing the Mediterranean (Fig. 9). The city was crowded with monuments and public buildings, criss-crossed by an efficient street network, well maintained, and cosmopolitan. However, the urban image owed its uniqueness and

Figure 7.

(above) Rooftops of the casbah; sketch by Charles Brouty, 1933.

Figure 8.

(below) Exterior view of al-Kabir Mosque, c. 1930. Part of this mosque was

demolished to make room for the Rue de la Marine. During the operation,

one row of interior columns was turned into an exterior colonnade.

Figure 9.

Nineteenth-century view of Algiers from the sea.

integrity to the residences, collectively an impressive mass of white, cubical structures that had evolved incrementally.

The Myth of the Casbah

The image of the casbah from the sea, described, drawn, painted, and photographed repeatedly by travelers, artists, and architects, became engraved in the collective imagination and, nurtured with the Orientalist cultural repertory on Islam, enhanced the creation of a "myth." For Roland Barthes, myth is a "system of communication," a "message." It is defined by the "way in which it utters this message," and not by the "object of its message." It is "chosen by history" and is "filled with a situation."[19] In this case, then, the myth was about the colonial discourse and not the casbah itself; it was colonialism (the historic "situation") that framed the casbah with certain concepts. In turn, these powerful and enduring concepts played an important role in shaping colonial policies regarding the casbah. The myth and the politics of colonialism continued to nurture each other throughout French rule.

The myth of the casbah developed around three concepts: gender,

mystery, and difference. The first was linked to the broader project of the feminization of the Orient; yet in the colonial context, the gendering of Algerian society and culture became blatantly referential to power structure. As Winifred Woodhull has shown, French intellectuals, the military, and administrative officers made Algerian women the "key symbols of the colony's cultural identity." In a typical formulation, J. Lorraine, writing at the turn of the century, called the entire country "a wise and dangerous mistress," but one who "exudes a climate of caress and torpor," suggesting that control over her mind and body was essential.[20]

The casbah, too, became identified with a single and undifferentiated Algerian woman. Popular literature abounds with descriptions of Algiers as a woman, often an excessively sensuous one. In the travel accounts of Marius Bernard, for example, Algiers is a woman to fall in love with. Even its name carried a special appeal:

Algiers! Such a musical word, like the murmur of waves against the white sand of the beach; a name as sweet as the rippling of the breeze in the palm trees of the oases! Algiers! So seductive and easy-going, a town to be loved for the deep purity of her sky, the radiant splendor of her turquoise sea, her mysterious smells, the warm breath in which she wraps her visitors like a long caress.[21]

Similarly, Lucienne Favre, a woman novelist writing in the 1930s, described the casbah as "the vamp of North Africa," bearing a "capricious feminine charm" and a great "sex appeal."[22]

Le Corbusier's gendered description of Algiers extends this tradition to architecture. Provoking associations between the curved lines of his projects and the "plasticity" of the bodies of Algerian women, Le Corbusier described at length his enchantment with these women and consistently represented the casbah as a veiled head in his reductive drawings (Fig. 10). He also likened the city to a female body: "Algiers drops out of sight," he noted, viewing the city from a boat leaving for France, "like a magnificent body, supple-hipped and full-breasted. . . . A body which could be revealed in all its magnificence, through the judicious influence of form and the bold use of mathematics to harmonize natural topography and human geometry."[23] The cover sketch of his Poésie sur Alger depicts a unicorn-headed, winged female body—supple-hipped and full-breasted—the city/poem caressed gently by a hand (the architect's) against the skyline of new Algiers, to be designed by Le Corbusier himself (Fig. 11).

Figure 10.

Le Corbusier, sketch showing the casbah as a veiled head.

Le Corbusier elaborated on the sensuality of Algiers by describing the city's intimate relation to nature and recycling the formula that equates nature with woman. The casbah complemented its surrounding geography and absorbed all senses:

We are in Africa. This sun, this space created by azure and water, this foliage have formed the set for the actions of Salambo, Scipio and Hannibal, t together with those of Kheir-ed-dinn the Barbaresque. The sea,

Figure 11.

Cover of Le Corbusier's Poésie sur Alger.

the chain of the Atlas Mountains, the slopes of Kabylia unfold their blue displays. The earth is red. The vegetation consists of palm trees, eucalyptus trees, gum trees, cork oaks, olive trees and fig trees; the perfumes, jasmine and mimosa. From the first plane to the confines of the horizon, the symphony is imminent.[24]

The casbah was so intertwined with landscape and nature that it made the site: "The casbah of Algiers . . . has given the name Algiers-the-White to this glittering apparition that welcomes at dawn the boats arriving from the port. Inscribed in the site, it is irrefutable. It is in consonance with nature."[25]

Hand in hand with its gendered sensuality, the casbah evoked mystery. It represented the attractions of unknown dangers, as expressed by one writer: "The Kasbah! This magic word intrigued me when I was a child. It pursued me over the years, evoking so much mystery, such hazy and disturbing images. When it was spoken it had a special sound. . . . I imagined a den of danger and enchantment, straight from the Arabian Nights ."[26] Furthermore, it marked the difference between cultures and even formed for some observers an inspiring contrast to the "vulgarity of the Occident," with its "trams, machinery, cylindrical costumes, stupidity of words": "And to know that simply two steps from all this is the possibility of perpetual beauty . . . which is only to push open a door, to take a few steps in order to enter right away into a magic land."[27]

Even when the observer did not romanticize about the casbah, he or she attributed elements of mystery and unfamiliarity to it. Eugène Fromentin, for example, noted the dramatic transition from culture to culture and its immediate effect, but claimed to have transcended mere appearances and to understand the hidden meaning about the civilization the casbah represented:

Opposite [the European town] . . . open discreetly contemplative quarters of old Algiers. . . . Bizarre streets like mysterious stairways that would lead to silence climb [the hill]. The transition is so rapid, the change of place so complete that one recognizes the better, the more beautiful sides of Arab people, those sides that make a contrast with the sad example of our social state. . . .

Their town, whose construction itself is the most significant symbol, their white town shelters them, more or less like the national bournous that they wear, in a uniform and crude envelope. . . . [A] single mass of masonry, compact and confused, built like a sepulchre . . . such is the strange city where a people who had never been as grand as we believed . . . lives, or rather extinguishes itself. I spoke the truth when I mentioned a sepulchre. The Arab believes he lives in his white town; he is buried there.[28]

Descriptions and commentaries on the casbah perpetuated the myth that restricted the city and remade it according to favorite colonial paradigms. In addition, the freezing of the old town in a mythical frame

abstracted it from history. Colonial discourse attempted to reserve history making for the colonizer alone; the casbah was relegated to acting as a background that highlighted the colonizer's "innovative dynamism."[29] Years later, struggling with the problems of the casbah in independent Algeria, Dr. Amir, the president of COMEDOR (Comité permanente d'études, de développement, d'organisation et d'aménagement de l'agglomération d'Alger) felt the need to undo the myth to be able to face the urgent issues. He argued that the colonial discourse that had made the casbah an "exotic town . . . something different to look at" carried serious political implications. By focusing on the "picturesqueness of its streets and beauty of its patios" as the only impressions to be retained from a visit to the old town, the "colonial mechanism" in reality dismissed the essence of the old town and its sociocultural realities.[30]

Replanning al-Jaza'ir

First Interventions

The casbah posed a great challenge to French planners for a variety of reasons: high population densities, concentration and form of the built fabric, topography, and sociocultural texture, as well as their own romantic/Orientalist appreciation of its aesthetic values, accompanied by a growing consciousness of historic preservation. In part due to these reasons, but also to the need to provide new quarters to lodge Europeans, interventions in the casbah remained incremental throughout the French occupation and no grand plans were ventured. While the upper part of the town was left practically untouched, the lower part underwent certain transformations that accentuated the preexisting division during the colonial period. The greatest changes to the lower city, known later as the Marine Quarter or the Quarter of the Ancient Prefecture, took place during the initial phase of colonization, between 1830 and 1846.

A solution that essentially characterized almost all later projects was proposed by Théophile Gautier in 1845: the high casbah should be preserved "in all its original barbary," while the Europeans should stick to the lower part, close to the harbor, because of their penchant for "large streets . . . cartage . . . and commercial movement."[31] This was exactly what had happened in the early years of the occupation, when the main

concerns were militaristic (not yet commercial) and before it became clear that expansion beyond the Ottoman fortifications was a necessity. The documents from the first decade of the French regime reveal an overwhelming obsession with potential offensives from Europe and only a secondary consideration for possible conflicts and confrontations with local people. Military engineering dominated all urban design operations during this period.

The pressing issues of the 1830s consisted of lodging military troops and cutting through the necessary arteries to enable rapid maneuvers. Appropriation of houses, shops, workshops, and even religious buildings was commonplace during the first years of the occupation and often involved modifications in the buildings to accommodate the needs of the army.[32] The abrupt brutality of the first interventions caused an immediate controversy, making the city and its architecture prime actors as contested terrains in the colonial confrontation. Oral literature from the time of the conquest is rich with examples that voice the collective sentiments of local residents. One such song lamented the invasion and appropriation of the city and highlighted the violation of its most revered cultural icons:

O regrets for Algiers, for its houses

And for its so well-kept apartments!

O regrets for the town of cleanliness

Whose marble and porphyry dazzled the eyes!

The Christians inhabit them, their state has changed!

They have degraded everything, spoiled all, the impure ones!

They have broken down the walls of the janissaries' barracks,

They have taken away the marble, the balustrades and the benches;

And the iron grills which adorned the windows

Have been torn away to add insult to our misfortunes.

O regrets for Algiers and for its stores,

Their traces no longer exist!

Such iniquities committed by the accursed ones!

Al-Qaisariya has been named Plaza

And to think that holy books were sold and bound there.

They have rummaged through the tombs of our fathers,

And they have scattered their bones

To allow their wagons to go over them.

O believers, the world has seen with its own eyes.

Their horses tied in our mosques,

And they and their Jews rejoiced because of it

While we wept in our sadness.[33]

Expropriation and demolition were rampant, but on a fragmented and relatively small scale. True French urbanism in Algiers originated with the carving of a Place du Gouvernement and the widening of three main streets off this square that led to the main gates: Rue Bab Azzoun going south, Rue Bab el-Oued going north, and Rue de la Marine east to the harbor.

The idea of a Place du Gouvernement developed immediately after the conquest. Noting right away that the existing town lacked a large, conveniently located space for assembling the troops, the chief army engineers decided to open an "immense" area in front of the Palace of the Dey (Figs. 12 and 13).[34] The initial clearing—which involved the demolition of the minaret of the al-Sayyida Mosque,[35] as well as "many shops in bad shape and several houses," in the words of Lieutenant Colonel Lemercier—was based on practical goals: to shelter the troops, to enable the movement of carriages, and to establish markets. Lemercier added, however, that with later enlargements according to a plan, this square would turn the quarter into "the most beautiful and the most commercial" in town. Successive projects attempted to regularize the square: a pentagonal piazza, planted with trees, dotted with fountains, and surrounded by two-story residential buildings with arcades on the ground level was proposed in 1830.[36] A rectangular proposal by a government architect named Luvini called for the demolition of the al-Jadid and al-Sayyida mosques in 1831, but was opposed by Lemercier out of sympathy for the local population in order "not to hurt the religious sentiments of the Moors" (Fig. 14).[37] Al-Jadid survived the demolition fever, but al-Sayyida was torn down to allow for a building with a regular facade on the square.[38]

Capitalizing on the damage caused by a fire to parts of the Janina Palace in 1844, numerous projects attempted to readjust the plaza's overall shape in the following decades. Over a long period of time it acquired a loosely rectangular shape with arcades on three sides, the irregularity of the east side a result of Lemercier's desire not to tear down the al-Jadid Mosque (Fig. 15).[39]

The enlargement of Bab Azzoun, Bab el-Oued, and Marine streets did not involve such drastic demolitions. Adhering to preexisting patterns, they followed an irregular route but were widened to 8 meters to allow for two carriages to pass (Fig. 16).[40] In 1833 two other streets, Rue de Chartres and Rue des Consuls, were classified with the first three as the main arteries of Algiers, although only Rue de Chartres could be enlarged and that in 1837. Between Bab Azzoun and Rue de Chartres a

Figure 12.

(above) Plan of central Algiers, showing the Place d'Armes (Place du Gouvernement),

1832. Figure 13. (below) View of the Place du Gouvernement, c. 1835. The building

to the left in the foreground is the al-Jadid Mosque.

Figure 14.

Proposal for regularization of the Place du Gouvernement, 1831.

square, Place de Chartres, was carved by demolishing a small mosque and a series of commercial structures (Fig. 17). To compensate for the loss of the latter, the urban administration constructed here a covered market with 250 shops for the exclusive use of indigenous populations. Boulevard de la Victoire, defining the highest boundary of the town,

Figure 15.

Aerial view of the Place du Gouvernement, 1934. The al-Jadid Mosque is to the right.

also dates from this period.[41] To facilitate military movements and vehicular circulation in the upper casbah, a plan in 1834 proposed a new gate on the south walls and an artery connecting this gate to the citadel. In addition to serving the army, the new "grande route" would bring life to the residents of the upper town by providing an alternative to the existing "exceptionally narrow" streets; totally inaccessible to vehicles.[42] The project, which also regularized the central square, was not executed.

Regularization, Reduction, and Isolation

Comprehensive urban design projects that targeted the reorganization of the entire settlement were few and far between. Engineer Poirel's 1837 proposal to regularize and widen the street network, bringing the secondary streets to 3 and 5 meters wide, received a great deal of criticism due to its excessive catering to private interests.[43] Later designs focused on the extension of the city and only marginally ad-

Figure 16.

Rue Bab Azzoun, c. 1990.

dressed the old town. One example is Charles Delaroche's 1848 project, which doubled the size of Algiers by new fortifications and a modern settlement with wide arteries and squares in the European quarter (Fig. 18). Delaroche's unrealized interventions to the casbah consisted of broadening three major streets that cut across the old town and carving a few squares at important intersections.

Figure 17.

Plan of the casbah. (1) Boulevard Gambetta, (2) Boulevard

de la Victoire, (3) Boulevard Vallée, (4) Rues Randon and Marengo,

(5) Rue Bab el-Oued, (6) Rue d'Orléans, (7) Rue de la Marine, (8)

Place du Gouvernement, (9) Place de Chartres, (10) Rue Bab

Azzoun, (11) Rue de Chartres, (12) Rue de la Lyre.

The realization of a main artery on the waterfront, Rue Militaire, first presented in a sketch by Poirel in 1837 and intended to serve the harbor as well as act as a promenade, was delayed until 1860. When construction began, the artery was named Boulevard de l'Impératrice, celebrating the visit of Empress Eugénie and Napoleon III to Algiers the same year. It was completed in 1866 according to Charles-Fréderick Chassériau's plans (Fig. 19). A particularly difficult feat of engineering due to the drastic difference in level between the boulevard and the embankment, the structure was supported by a series of high arches recalling a bridge or an aqueduct. The ramps connecting the Boulevard de l'Impératrice to the harbor level took another eight years to build.[44] The project gave Algiers its memorable waterfront: the continuous high arcade of the lower level, animated by the changing scale of the arches supporting the ramps and in juxtaposition to the more delicate arcades of the Boulevard de l'Impératrice on the upper level—all in white.

Figure 18.

(above) Plan by Charles Delaroche, 1848.

Figure 19.

(below) Aerial view of the arcades and the Boulevard de l'Impératrice, 1933.

While providing a spectacular edge to Algiers, this project also engraved the power relations of the colonial order onto the urban image: the casbah was locked behind the solid rows of French structures.

The obsessive focus on defense generated persistent demands for the enlargement of the fortified areas—a debate that had started in 1840.[45] By 1849, the old fortifications were replaced by new ones, enclosing an area three times larger than the one occupied by the old town. The lower part of the casbah had acquired a more regular street network with two main arteries, Rue de la Marine and Rue d'Orléans, which connected Rue de la Marine to Rue Bab el-Oued (see Fig. 17). The European settlers—French, but also Italian and Spanish—lived here, while the upper casbah became an exclusively indigenous town. The distinction between the two parts was reflected in their new names: the upper casbah became the "casbah" proper and the lower town became the Marine Quarter.[46]

The conjuncture of the casbah and the Marine Quarter was subjected repeatedly to regularization proposals. In 1917, for example, a project devised for the area defined by Chartres, Vialar, and Bab Azzoun streets and Place du Gouvernement, advocated the enlargement of Rue Bab Azzoun by appropriating 6-meter strips from its west side, thereby changing the width from 8 to 14 meters. In addition, Rue de Chartres and Rue de Vialar would be widened to 10 meters, and transversal streets, 8 meters wide, would connect the main arteries running parallel to the waterfront.[47]

Of various plans devised for the Marine Quarter, the one proposed by Eugène de Redon in 1884 has been revived several times, most significantly in revised versions between 1901 and 1914, and in 1922 (Fig. 20). Redon's project was initiated by the municipality's growing concern about public hygiene in the Marine Quarter, in the area between Rue Bab el-Oued and Boulevard de la République on the waterfront (the original Boulevard de l'Impératrice). The municipal authorities agreed to "raze whatever existed" here.[48] Although Redon's project addressed the entire city, its main impact was restricted to the proposals for the Marine Quarter, because it established clear strategies to resolve the chaotic structure of this area. The essence of the proposal involved the displacement of half of the population residing in the quarter, specifically the urban poor, who would be relodged in new housing projects to be built on the hills of the Bab el-Oued Quarter to the northwest of the old town. This depopulation would enable the replacement of narrow streets with large arteries lined with luxurious buildings to attract the wealthy bourgeoisie. A 25-meter-wide main avenue, Avenue de la

Figure 20.

Eugène de Redon's plan for the Marine Quarter, 1925.

Préfecture, would extend the Boulevard de la République. At the beginning point of the avenue, close to the Place du Gouvernement, placement of the stockmarket and the Tribunal of Commerce expressed the ambition to turn the Marine Quarter into an impressive business center. The reorganization of the area would result in the reorientation of the al-Jadid Mosque and demolition of the al-Kabir Mosque, with plans to rebuild it on the northern flanks of the casbah.[49]

The 1922 version of the Redon plan emphasized once more the quarter's congestion and the necessity for erasing the entire area to accommodate circulation and called for the displacement of twelve to fifteen thousand people. The new buildings would cater above all to the needs of commerce.[50] In this version, however, the two mosques were preserved and a prominent casino was placed where the main avenue met the waterfront in the north.

Interventions to the casbah proper were relatively few. The north-south Rue de la Lyre (present-day Rue Ahmed Bouzrina), parallel to the Rue Bab Azzoun, stood out with its straight layout and continuous colonnades amid the irregular street fabric surrounding it. Projected in

1845 but completed in 1855, it connected the center with the newly planned suburb Bab Azzoun and eased the heavy circulation on the axis of Rue Bab Azzoun and Rue Bab el-Oued.[51] Its architectural qualities made it especially significant to the French as a reminder of the Rue de Rivoli, a cherished urban fragment from Paris now implanted in Algiers. Rue Randon (now Ali la Pointe), its extension Rue Marengo (now Arbaji), and Rue Bruce were also cut through at this time.[52] Other major alterations carried out in the 1840s included two straight boulevards, Boulevard Vallée (present-day Boulevard Abderazak Hadad) on the north and Boulevard Gambetta (present-day Boulevard Ourida Meddad) on the south, both built on the glacis of the Ottoman fortifications.[53] Remaining at the edges of the old town, the major interventions during the early phases of the colonial rule may seem to have had little effect on the core of this introverted settlement. Nevertheless, the boulevards encircled the casbah and signified the surrender of the original residents of Algiers to the French—literally and metaphorically.

French architects early on acknowledged the immense difficulty of cutting through the casbah. A report submitted to the governor general of Algeria in 1858 pointed to the futility of fighting "against nature," against the capricious, "tormented," and "accidental" topography of the casbah. Arguing that the needs of the French were different from those of the indigenous people, the report proposed the construction of a new town, which would cater to European tastes, next to the old one.[54] Napoleon III's "arabizing" policies enhanced the conservation of the casbah further. The new policy of "tolerance" that dominated the 1860s criticized former demolitions and European constructions in the old town, which had pushed the local population to upper slopes and resulted in highly congested living conditions. The report that followed the emperor's research maintained that

the town must conserve its actual physiognomy, that is to say, the high town must stay as it is, because it is appropriate to the customs and habits of the indigenous; cutting through grand arteries may result in causing them great suffering, and all these improvements may impose hardships to the indigenous population, which does not have the same lifestyle as the Europeans. The emperor thinks that the lower town should be reserved for the latter and it is in that part that all works of improvement and beautification should be made.[55]

In the late 1870s Eugène Fromentin summarized the early colonial policies Napoleon III aimed to change and commented on the rationale and extent of the French appropriation of Algiers:

France took from the old town everything that was convenient for her, everything that touched the waterfront or dominated the gates, everything that was more or less level and that could be easily cleared, and readily accessible. She took the Djenina, that she razed, and the ancient palace of the pachas, that she converted into the house of her governors . . . . She created a little Rue de Rivoli with Bab Azzoun and Bab el-Oued streets, and peopled it with counterfeiting Parisians. She made a choice between mosques, leaving some to the Qu'ran, giving others to the Evangelists.[56]

After these initial interventions, the casbah was left on its own. If demolition was no longer the issue, neither was maintenance. Algerian urban sociologist Djaffar Lesbet argues that the implicit menace of destruction to the casbah posed by neglect played a constructive and catalyzing role on the residents and forced them to pool their resources to stop the "natural" demolition of their neighborhoods. The basis for an alternative urban administration was established, operating on two levels: the maintenance of public open spaces by designated officers from the casbah and the maintenance of individual houses by the collaborative and organized labor of renters and owners. The residents of the casbah thus spoke back to colonizers by turning to themselves, consolidating their unity, and establishing their own system. With this move, Lesbet maintains, the casbah was transformed into a "counter space" (espace contre ) that represented the oppositional voice of Algerians to colonial power.[57] The diametric stances of the casbah and the French Algiers, crystallized further by the former's "counter space" character, destroyed any possibility of overall harmony in a situation distinct to French colonial urbanism. In the words of Fanon, "The zone where the natives live is not complementary to the zone inhabited by the settlers. The two zones are opposed, but not in the service of a higher unity. Obedient to the rules of pure Aristotelian logic, they both follow the principle of reciprocal exclusivity. No conciliation is possible."[58]

The Ideology of Preservation

The polarization in the urban form and social structure of Algiers was well in place after a century of French occupation. This did not mean, however, abandoning the casbah and its inhabitants to their own destiny. The attempts to renovate Algiers in celebration of one hundred years of French rule and in preparation for its leadership role in French Africa brought the old city—both the casbah and the

Marine Quarter—into focus. By this time, the first colonial interventions into the old city were subject to widespread criticism among the French in Algeria. The critics focused on two points: demolition of the old fabric and the poor aesthetic quality of the European structures. According to one critic, before the arrival of the French,

The capricious urbanism of Algiers had the great merit of unity; Arab architecture only had buildings that accommodated their goals and that presented an ensemble of haditations all built according to a uniform plan. From the first stroke, we abolished this harmony.

The most beautiful indigenous quarters thus were hollowed out; hundreds of houses were torn down; either the military administration or the entrepreneurs, after demolishing and ravaging, replaced the oriental dwellings with villain structures in the European style for renters.[59]

The foremost scholar of Algiers, René Lespès, also emphasized the "uniformity of the Moorish houses of Algiers," which harmonized with the lifestyles and customs of the residents. Grieving over the destruction of the ancient town, he pointed to the need to understand the particular character of these houses, as well as the intentions and the necessities that dictated their plans against the "stupidity and inelegance . . . of the desire to Europeanize them."[60]

The new directions adopted during the two decades from the 1930s to the 1950s agreed on the preservation of the precolonial heritage of the casbah. In essence, the policies pursued Napoleon III's notion of royaume arabe (arab realm) and, building on decades of French colonial experience, brought a clearly articulated ideological justification to all the design decisions.

Hubert Lyautey, governor general of Morocco from 1912 to 1925, is acknowledged for his development of distinct French colonial urban policies and an ideology of preservation in the colonies. The essence of his urbanism aimed to accommodate a new order, based on diversity, where people of different social and cultural circumstances could coexist.[61]

Lyautey's two main principles, which recall Napoleon III's policies for Algiers—namely, preservation of medinas out of respect for the local culture and building of new, modern cities for European populations—formed the backbone of all later urban planning decisions in Algiers. For Lyautey, the preservation of the Arab town had several meanings, some emotional, some practical. Above all, he savored the aesthetic qualities of the Arab town, its "charm and poetry," which he attributed

to the sophistication of the Arab culture.[62] To understand the difference between this culture and the European one was essential to building a colonial policy that would endure: "The secret . . . is the extended hand, and not the condescending hand, but the loyal handshake between man and man—in order to understand each other . . . . This [Arab] race is not inferior, it is different. Let us learn how to understand their difference just like they will understand it from their side."[63]

This major difference between the two cultures required the separation of the indigenous from the European populations in the city, according to Lyautey:

Large cities, boulevards, tall facades for stores and homes, installations of water and electricity are necessary, [all of] which upset the indigenous city completely, making the customary way of life impossible. You know how jealous the Muslim is of the integrity of his private life; you are familiar with the narrow streets, the facades without opening behind which hides the whole of life, the terraces upon which the life of the family spreads out and which must therefore remain sheltered from indiscreet looks.[64]

Consequently, Lyautey made the conservation of the Moroccan medinas one of his priorities in urban planning. He announced proudly, "Yes, in Morocco, and it is to our honor, we conserve. I would go a step further, we rescue. We wish to conserve in Morocco Beauty—and it is not a negligible thing."[65] Behind these compassionate words, however, lay an economic goal: the medinas were essential for the development of tourism, especially for the romantic traveler and the artist.[66]

The International Congress on Urbanism in the Colonies, held during the 1931 Colonial Exposition in Paris, recorded the powerful influence of Lyautey's ideas and practice on the new rules of planning in French colonies. Among the goals of the congress, as listed by Henri Prost, were "tourism and conservation of old cities" and "protection of landscapes and historic monuments." The "wish list" of the participants included the creation of separate settlements for indigenous and European populations, respecting the beliefs, habits, and traditions of various races. Whenever possible, a greenbelt, sometimes referred to as a cordon sanitaire , would divide the European town from the indigenous one.[67]

In Algiers, these principles were already written into ordinances by the late 1920s, and the "indigenous quarters" were placed under a special regime destined to conserve their character—despite the fact that "they were in opposition to principles of hygiene and urbanism."[68] The

architects in Algiers knew that conservation was not sufficient to preserve the picturesque character of the casbah; given the buildings' fragility, rehabilitation was an important issue. One architect, Jean Bévia, proposed regulations to prohibit changes, to fix the height limits, and to impose "the Arab style." Nevertheless, he advocated demolishing buildings in had condition and using their lots to "ventilate" these congested neighborhoods. Furthermore, a special municipal commission of hygiene had to be established to educate the residents—a most difficult task, Bévia maintained, given that the local people ignored all rules of health and hygiene.[69] A recurring theme in the discussions on the casbah, the "lack" of hygiene (together with the "lack" of order, material civilization, and so on) is a key mechanism in what Ella Shohat and Robert Stam call "the transformational grammar of colonial style racism," which reiterates the hierarchical structure of the colonial society.[70]

A special regulation, dated 13 June 1931, intended to conserve the "character and aesthetics" of the casbah by "imposing on the inhabitants the obligation to restore their houses and to build new ones only in ways that serve to that effect, following the proportions and characteristics of the indigenous architecture of Algiers." A newly created commission of consultants would supervise the casbah. Accordingly, Henri Prost, René Danger, and Maurice Rotival drafted a master plan for Algiers in 1931 that aimed to preserve the casbah.[71]

The abstract notion of the preservation of casbah was further articulated during the following years. Now the upper city itself was divided into two. The efforts of the Commission of Historic Monuments contributed greatly to the regulations concerning the "picturesque physiognomy" of the new "upper" casbah, defined by Rue Randon and Rue Marengo and Boulevard de la Victoire. This quarter would be neither demolished nor rebuilt as pastiche in the manner of "exhibition pavilions," a term used derogatorily. The rules were clearly specified: all new houses would conform to Algerian and Moorish styles; cornices, windows, wood lattices, canopies, doors, polished tiles, and painted or sculpted woodwork would be either preserved or reconstructed according to the original; a few new interpretations could be allowed if the output conformed to the general style; demolished European houses would be replaced by ones in the indigenous style; no building would be higher than three floors, including the ground floor; and all plans had to be submitted to the Technical Services section of the municipality for approval.[72]

While intervention to the upper part of the casbah was minimal and its residential function was maintained, the lower part, between Rue

Marengo and Rue Bab el-Oued, would be turned into a "museum quarter." Here, careful restoration of the few authentic buildings of aesthetic value and the preservation of the "tortuous and vaulted" Rue Emile Maupas and Rue de l'Intendance, considered by Lespès as "the most remarkable in old Algiers," would be undertaken. The archdiocese, the Palais d'Hiver, the headquarters of Indigenous Military Affairs, the old Moorish baths, the Bibliothèque Nationale, and the palace that now sheltered some offices of the secretary general would form an easily accessible ensemble as a museum complex.[73] In addition, schools for the indigenous would encourage the development of local art forms. As an integral part of the greater mission to preserve Algeria's historic heritage, an impressive number of new schools and workshops had already been established by the colonial authorities to develop local crafts—embroidery, leatherwork, copperwork, metalwork, carpentry, pottery, masonry, and decorative arts—with the goal of increasing their commercial value.[74]

Le Corbusier's projects for Algiers (spanning from 1931 to 1942) pursued the prescribed policy of preservation, used the same terminology, and gave the familiar rationale in explaining what to do with the casbah. Le Corbusier's casbah was also "beautiful," "charming," and "adorable," and it "never, no, never must be destroyed." Its historic significance as the "place of European and Muslim life during centuries of picturesque struggles" was held to be of great interest to the entire world. Therefore, its historical and aesthetic values, the vestiges of Arab urbanism and architecture, should be protected to enhance the "gigantic" touristic potential of Algiers. The overpopulation of the casbah, however, posed a difficult problem because it sheltered four to six times more residents than it could contain. If Algiers was to become the capital of French Africa, the misery of its Muslim population had to be addressed, the casbah "purified" and reorganized, its population reduced.[75]

Le Corbusier thus proposed to preserve the upper casbah in its integrity while restricting the densities and intervening in the patterns of use, in accordance with the planning decisions made before him. A number of buildings were to continue to function as residences, but others were to be converted into arts and crafts centers to initiate an indigenous "renaissance." The slums of the lower casbah, in contrast, would be expurgated; only the mansions would be preserved, yet converted into specialized museums for the indigenous arts. Parks and gardens would replace the areas cleared from the slums, but the existing street network

Figure 21.

Le Corbusier, project for Algiers, photomontage, 1933. The business center,

shown in the foreground, is connected to the residential areas on the hills by

means of an elevated structure that forms a bridge over the casbah.

would be maintained to link the high casbah to the Marine Quarter and to the harbor.[76]

Le Corbusier interpreted Lyautey's idea of a greenbelt separating the European city from the casbah. In his 1932 plan, for example, a giant linear structure that connected the hillside residences for Europeans to the cité d'affaires in the Marine Quarter formed a bridge over the casbah, transforming the sanitary greenbelt into an air band and reversing the horizontality of the former into a vertical element (Fig. 21). Repeating the concept in his later plans, Le Corbusier himself emphasized the essential separation of the two settlements: "This artery will be separated entirely from the indigenous town, by means of a level difference."[77] Le Corbusier's project would thus establish constant visual supervision over the local population and clearly mark the hierarchical social order onto the urban image, with the dominating above and the dominated below.

Post-World Way II Realities

The casbah entered a crisis in the late 1930s. Political and economic conflicts and instability stalled all plans for the casbah in the

later part of the decade. World War II shifted the focus of political concerns away from the local populations, pushing the casbah further into the background. The result was an intensification of the problems noted repeatedly in the early 1930s, namely the pace of demographic growth and physical decrepitude.

According to the 1931 census, the population of the upper casbah was about 54,000 people, with nearly 3,000 inhabitants per hectare; as compared to 1,430 in 1881 and 2,028 in 1921. The growth was largely due to immigration from Kabylia. The majority of the casbah's population consisted of indigenous people, Arab or Kabyle, although there was a considerable Jewish contingent; the few Europeans were often married to locals. As indicated by the very high densities, housing conditions were dreadful, with often an entire family crammed into a single room. The majority of the houses did not have electricity or running water, but sometimes a well in the shared courtyard. Remnants of the former lifestyle could be found in a small number of houses that belonged to the Turkish bourgeoisie on Rue de la Grenade (now Kheireddine Zenouda), Rue Kléber (now Rue des Frères Bachara), and Rue Sidi Mohammed Cherif.[78]

By 1949, the population had increased to 64,000 in the 38-hectare area defined by Boulevard Gambetta, Boulevard de la Victoire, Boulevard de Verdun, and Bab el-Oued and Bab Azzoun streets, raising the density in certain locations to 3,500 inhabitants per hectare. Of the 2,250 buildings of the upper casbah, 7 were mosques, 5 synagogues, and 1 a Protestant church; only 15 residences were "classified," that is, in good condition. E. Pasquali, an engineer in charge of the Central Division of Technical Services in the municipality, reported that the rest of the residential fabric, "several centuries old," would be subject to a municipal program. The first step in this program consisted of a survey of all buildings, to be followed by necessary interventions to assure the safety of the inhabitants, and, eventually, by demolition. While the municipal officer regretted the disappearance of these "last witnesses of the barbaresque period," he argued that in the interest of the residents and the quarter itself, there was no other alternative. The demolition of thirty-three houses in 1948 marked the beginning of a new era for the upper casbah: it was now essential to draft a redevelopment plan for the old town.[79]

Two years later, such a plan had not been drafted and Pasquali still advocated the demolition of most of the casbah, pursuing the dominant attitude toward historic cities everywhere at the time. He now proposed that before demolitions, however, a new cité should be built for the resi-

dents who would be displaced. He attributed the unhygienic conditions to overpopulation and the age of the buildings, pointing to physical as well as social diseases that would result from the crowding of eight or ten persons into a single room and two hundred into a single house. Under attacks from the conservationist camp, Pasquali eventually had to "admit, in spite of everything, that tourists did not come to Algiers to contemplate (our) Isly and Michelet streets," and that it was the casbah that made Algiers a tourist attraction due to the originality of the siting of its houses and to its "sympathetic disorder." His solution was to convert the upper casbah in its entirety into a museum and to remove its actual residents.[80]

The loss of old Algiers was an eventuality agreed on by many European observers. The only unchanged section was the heights, the quarter bordered by Rue de la Casbah on the north, Boulevard de la Victoire on the west, Rue Rampart-Médée and Rue du Centaure in the south, and Rue Randon and Rue Marengo in the east. With the goal of limiting historic preservation to this relatively small area, planners argued that here the original street network and the Moorish houses should remain intact. European constructions were negligible and the population exclusively Muslim. Given that the rest of the casbah had been intersected by several arteries and that old age was in the process of destroying whatever was left of the original buildings, the area once occupied by the old town was diminishing rapidly. Already in the first period of colonization the great triangle of old Algiers had lost its base, with the two great mosques left freestanding and isolated from their community of worshipers.[81]

The overcrowding of the casbah began to push the limits of the old settlement with pockets of shantytowns at its borders in the early 1950s. The first bidonvilles appeared to the west and the northwest of the casbah; the construction was made of any available material, including reed, zinc sheets, and large metal containers (bidons ). Here immigrants from the countryside lived in congested conditions, often more than ten people inhabiting a single shack. Carrying the aspect of a "real village of gourbis, " or huts, such settlements maintained a rural lifestyle and contrasted not only with the European parts of Algiers, but also with the urban form and life of the casbah itself. Nevertheless, the casbah had undergone some transformations as the waves of immigration changed its population cross-section to predominantly Kabyle residents, "a truly rural proletariat" that maintained its customs and traditions and resisted the urban culture.[82]

The urban administration proudly announced its success in introduc-

ing some elements of "modernization" to the casbah. By the first years of the 1950s, public fountains, at intervals of 200 or 300 meters, dotted the quarter; because the majority of the houses did not have running water, water carriers provided service for a fixed price. Garbage was collected every morning by small carts pulled by donkeys (regular carriages could not pass through the narrow streets), and the streets were washed by sea water. Electricity had also entered the casbah: not only the major streets, but also many houses were lit electrically.[83]

The debates between those who favored the preservation of the casbah (for historic and touristic reasons) and those who favored radical surgery (for hygienic—later political and militaristic—reasons) continued until the liberation. Even after the Battle of Algiers turned the historic city into a war zone, a romance with the beauty of its site and architecture lingered among many sectors of European society. In 1959, for example, the chief engineer of the Urbanism Section of the Municipal Council of Algiers gave an extensive tour of the casbah to a delegation of European mayors, who, according to newspaper accounts, were seduced by the "cascades of white terraces, diving into the harbor in a dreamlike golden light."[84]

On 3 October 1957, Gen. Charles de Gaulle revealed his extensive development plan for Algeria. The Plan de Constantine, named after the city where de Gaulle's famous speech was delivered, was based, according to its promoters, on "human promotion." Its premise, as outlined by de Gaulle, emphasized the role of France as the bearer of civilization, now a modern civilization: "Algeria in its entirety must have its share of what modern civilization can deliver to men of well-being and dignity." Together with education, decent housing was deemed essential to improve the standard of life of the Algerian people, but also to ensure their "social evolution" and "to modify their life habits and familial needs."[85]

Interpreted by its defenders as "the hope for the renaissance of the casbah," the Plan de Constantine addressed its problems on two levels: socioeconomic promotion and humanization of the daily life of the inhabitants. According to Jean Fabian, the municipal inspector for the casbah, the sociocultural project involved establishing new clinics and schools, and encouraging commercial enterprise. As congestion was the main issue, ventilating the casbah by means of demolition would allow for good traffic circulation and improve the transportation problems, as well as endowing the quarter with a "decent and modern" face, one that would be perceived as "a very great French work." According to the

Plan de Constantine, the residents would be relodged in new housing projects specifically designed for them. Of the three possible solutions—to raze the casbah entirely, to keep it as it was, or to redevelop it—the last was deemed the most productive. The houses in poor condition would be taken down, while others whose salvage was possible would be restored according to an effective technical plan. This option would not only bring down the population densities, but also establish an equilibrium between open space and built form.[86]

Despite regulations and the innumerable debates on how to improve the conditions in the casbah, the administration did not take any action. With the intensification of local resistance against French rule, the casbah became a "high risk" war zone. Ultimately, it was abandoned by the urban administration altogether. As noted by Lesbet, Algiers and the casbah were played against each other during the war, expanding on their oppositional roles established earlier.[87]

Impact of the Decolonization War

The image of the casbah changed fundamentally in 1954, when the region became the site of urban guerrilla warfare. For the Algerians, it became the locus of "the legend and the slum," that is, the legend of the Revolution and the slum of daily life. The National Liberation Front's Committee of Coordination and Execution had reorganized the administration of the casbah by dividing it into zones and establishing a system of planques (hideouts) and caches of resistance.[88] The complex configuration of the casbah, with interlocking terraces and passageways and tortuous dead-end streets, made penetration by French authorities difficult and facilitated defense.

As the site of war, certain locations in the casbah became associated with unforgettable moments for Algerians. The houses where resistance fighters were caught, tortured, and sometimes murdered became engraved into public memory. For example, the Rue Sidi bin Ali was the hiding place and explosives laboratory of Yacef Sadi, who escaped miraculously during the invasion on 6 February 1956; the same night, on Rue de la Grenade, Djamila Bouhired's father and brother were tortured in her presence for hours; two months later, Djamila herself was shot and arrested in the same location. On Rue Caton, Yacef Sadi and Zohra Drif were caught on 24 September 1958; on 3 October 1958 a group of houses was blown up by parachutists, resulting in the death of Ali la Pointe and Hassiba ben Bouali, in addition to thirty others.[89]

Figure 22.

Barricades in the casbah.

From 1956 on, it was common practice for the French security forces to invade the casbah and cut it off from communication with the rest of Algiers (Fig. 22). Even a random selection of news items conveys the change in the daily life of the casbah, now frequently interrupted by unexpected police raids. On 28 March 1956, in an attempt to "decontaminate" the casbah of troublemakers and "to protect the lives and properties of many families . . . whose only desire is to work and live in peace," the police forces blocked unexpectedly the Rue Marengo and Rue Randon, together with adjoining smaller streets, to question more than two thousand people; five hundred were taken to the police headquarters for identity checks. The same evening, a similar operation was carried out in the upper casbah, and still more people were put into custody. Another "giant control operation" imprisoned sixty-five hundred residents in the casbah on 26 May 1956 for twenty-four hours, during which more than four thousand people were interrogated and all contact with the exterior was halted. The casbah was surrounded at midnight, and machine guns and grenade launchers were placed at key locations, such as Boulevard de la Victoire and Rue de la Lyre. Colonial

newspaper accounts commented tongue in cheek on the lack of picturesqueness in the casbah during those twenty-four hours, when the residents were locked inside their houses and allowed to open their doors only to the police. On 8 January 1957, armed forces two thousand strong undertook a search operation in the upper casbah. A secondary objective of this massive action, which had started at 3:00 A.M., was to recruit unemployed people as construction workers. On 23 September 1956, twenty-four smaller streets around Rue Bab el-Oued, Rue Bab Azzoun, and Rue de la Lyre were barred from circulation "for an indeterminate amount of time."[90]

The French considered the defeat of Ali la Pointe the end of the Battle of Algiers, with the paramilitary forces as the victors. From that point military order reigned in the casbah and marked the region with its own symbols of war and occupation. Military and police officers had increased in great numbers, all strategic crossroads were wired, entries and exits from the casbah were controlled, and public spaces were decorated with propaganda posters (which were in turn covered with graffiti expressing themes of resistance and independence).[91] In December 1960, a tract signed by several resistance organizations and published in El Moudjahid , the official journal of the National Liberation Front (FLN), called the casbah the "new ghetto of Warsaw," in reference to the two hundred thousand people besieged here.[92] Yet though the casbah was locked off from the rest of Algiers and under military occupation, it still functioned as a theater for resistance, with parades echoing others elsewhere in the city until the end of French rule.[93]

The Story of the Marine Quarter

The divergence of the Marine Quarter and the casbah became definitive in the 1930s. In response to the debates to create a truly appropriate capital for French Africa, René Danger, Henri Prost, and Maurice Rotival drafted the first master plan for Algiers, which was approved in 1931. In accordance with the new enthusiasm for "urbanism" among French technocrats and administrators, the three architects were applauded as "true 'urbanistes' of highest quality, and of an indisputable fame."[94] This statement implicitly expressed doubt about Le Corbusier's credibility as an urbanist at the time when he had started working on his alternative designs for Algiers.

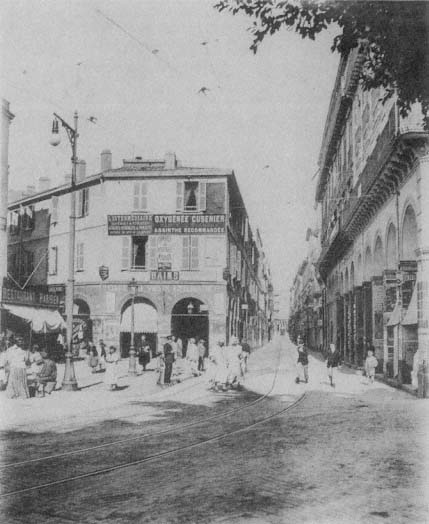

Within the framework provided by the master plan, Tony Socard, an

Figure 23.

Aerial view of the Marine Quarter, with the casbah behind, 1935.

architect working with Prost, developed a project for the Marine Quarter that was based largely on Redon's earlier scheme.[95] In the early 1930s, this quarter was densely inhabited by a low-income cosmopolitan population, mainly consisting of Neapolitan Italians, Spaniards, Jews, and "indigenous immigrants" (Fig. 23). Its street network was inaccessible to motor vehicles and its buildings extremely fragile—as witnessed by a building collapse on Rue des Consuls in 1929 in which over fifty people were killed. It was generally agreed that there was little here worthy of preservation. René Lespès defined the Marine Quarter at the time as "a small town, bastard, neither Moorish, nor entirely European." Joseph Sintes reaffirmed Lespès' statement by arguing that "this old quarter responded neither to aesthetics, nor to material or moral hygiene," the last reference to the scale of prostitution.[96] The few protests from the Comité du Vieil Alger to preserve several small and scattered "historic corners" were rebuffed (even by members of the committee itself) as "false Orientalism . . . now outmoded."[97] It was common sentiment that there was nothing worth saving from the residential and commercial framework and that valuable fragments—columns, tiles, woodwork, etc.—could easily be salvaged for incorporation into new buildings.[98]

The Marine Quarter was of crucial importance to Algiers, however, because it provided the connection to the harbor. It had also maintained a commercial character, with the Rue Bab el-Oued as the center of this activity, being the first stop for people descending from the casbah. Yet Bab el-Oued was lined with small shops that were deemed no longer efficient.[99] The presence of the two "untouchable" monuments, al-Kabir and al-Jadid mosques, caused several daily visits by Muslims in large numbers, inevitably making the quarter a meeting place—a notion that Le Corbusier would expand into a "meeting place" between the two cultures.

Socard's plan aimed to destroy the quarter entirely with the exception of the two historic mosques; their asymmetrical relationship, which betrayed the essence of Beaux-Arts urban design, would be "corrected" with landscaping (Fig. 24). A "magnificent boulevard," 450 meters long and 30 meters wide, would pass between the two mosques and act as the "great collector" of traffic circulating between Bab el-Oued and the streets to the west and northwest, on the one hand, and the waterfront and the ramps of the harbor, on the other. The Rue Bab el-Oued would be enlarged to 22 meters; the west part of the quarter would be divided into four sections by means of 16-meter and 10-meter streets, each part occupied by a building with a large garden court. The patchwork of houses between the Place du Gouvernement and Rue Mahon were to be demolished to give way to a park that would include the landscaped plaza in front of the al-Jadid Mosque and end in a curve to the west; the curve would be reflected on the east side of the grand avenue, creating a transversal axis. The east part of the quarter was differentiated as the locus of institutions, such as the chamber of commerce, stockmarket, Palace of Justice, library, and possibly the National School of Fine Arts. The project was seen as favorable in terms of circulation and a well-balanced distribution of built and open spaces; the resulting displacement of about fifteen thousand people would be resolved by settling them into the new housing projects.[100]

The project came under the attack of critics defending a more radical approach sympathetic to Le Corbusier's ideas. Emphasizing the importance of "scientific control by urbanists who know their job" and agreeing on the necessity to change the scale of the quarter, Jean-Pierre Fauve expressed his dissatisfaction with the Prost-Socard plan. According to Fauve, this plan was not "large enough." The widening of Bab el-Oued as proposed by Prost and Socard was in the spirit of the plans applied in Algiers in the 1850s and thus on a pre-automobile scale. The 35-meter width envisioned for the grand avenue was not daring enough, either.

Figure 24.

Tony Socard, plan for the Marine Quarter, 1935. Al-Jadid and al-Kabir

mosques are labeled 6 and 7, respectively. The buildings marked in black

form the institutional complex.

The best solution would be a ville radieuse , a radiant city that would let the sun in by decreasing the built surface and increasing the open space.[101]

Fauve also criticized Prost's overall master plan for shifting the city center away from old Algiers toward Agha in the south. Arguing that centers historically develop according to many good reasons, he challenged the Prost plan for not being functional and for turning its back on the history of Algiers. There was also a political issue at stake: as the capital, Algiers had a most important mission as a "Franco-Muslim" city. The Place du Gouvernement, the contact point of the two communities, had to remain the center of the city.[102]

Le Corbusier's designs preserved the central functions of the Marine

Quarter. In the 1932 plan, for example, a skyscraper sheltered the main activities of the cité d'affaires .[103] The "air belt" that separated the casbah from new Algiers began at this point with the proposal for a bridge-like structure that connected the skyscraper to the residential buildings for the Europeans on the hills above the casbah. Le Corbusier's successive proposals elaborated on the idea of the Marine Quarter as the "business center" and "civic center" of Algiers. Cleared and rebuilt with large blocks that left plenty of open space for parks and gardens, the quarter would provide the link between the European and Arab cities. Certain Arab institutions, such as offices, shops, and meeting halls, would be placed here. Le Corbusier maintained that the location was most convenient for overlapping functions because of its proximity to the port, its centrality in terms of future growth, and its significance as a historical axis for Arabs. The two mosques to be preserved, but cleared of the impeding fabric, would be returned to their original condition, sitting on a rock base. The presence of the new "indigenous institutions" in a "vast ensemble of new [and] grand Muslim architecture, as monumental as it would be picturesque," would complement the historic buildings.[104] In short, Le Corbusier's cleansing in the Marine Quarter would be urbanistic, architectural, and social, at once providing for controlled activities for Arabs and racial contact in an ordered environment.

After a long political battle, laced with intrigue, concessions, and compromises between the urban administration and Le Corbusier and his defenders, his project was rejected definitively in 1942 and the Prost plan was revived.[105] The war years stalled its implementation, however, and only in 1945 was the grand axis, Avenue du 8 Novembre (now Avenue du 1 Novembre), opened to circulation. The demolitions rekindled the sentiments of the citizens who feared the loss of their historic heritage. In a public letter, well-respected Algerian theologian and intellectual Omar Racim likened the destruction of Algiers to that of Hiroshima and argued that with the opening of the Avenue du 8 Novembre the mosques were "chipped" and found themselves as "old people deformed by age who in vain tried to hide their shame caused by their infirmities." He bitterly wondered when the city officials would "bury Algiers alive" by demolishing whatever was left of the old city in order to sell its pieces to tourists as relics.[106]

To enable the construction of the new artery, 340 buildings, covering an area of 45,800 square meters, were demolished, and 11,000 residents and 380 shopkeepers were evacuated (Fig. 25). Meanwhile 1,456 units of

Figure 25.

(above) Plan showing the extent of demolitions proposed by Socard's

project for the Marine Quarter. Figure 26. (below) Plan for the Marine

Quarter, 1950.

housing (amounting to 3,628 rooms) were constructed elsewhere, the city expropriated about 500 more buildings, and the construction of the first residential complex in the Marine Quarter was begun. P. Loviconi, the adjunct secretary general of the communal administration, summarized the status of the project in 1949, indicating clearly the extent of the demolition and construction work to be done.[107]

In 1950, a slight alteration to the project introduced a trapezoidal public place, the Place Impériale, open to the waterfront on the south but surrounded by buildings sheltering residential units and offices on the other three sides (Fig. 26). The Palace of Justice would define its narrow north side, and a skyscraper would be placed to the east, reviving Le Corbusier's 1932 scheme.[108] This project stalled again.

Mayor Jacques Chevallier refueled the efforts to renovate the Marine Quarter in a final, but doomed, attempt. By this time, the housing conditions had become even more urgent and the existing stock alarmingly decrepit. The 550 buildings over an area of 89,000 square meters, sheltering 18,000 to 20,000 residents, with densities approaching 1,500 people per hectare, were estimated unsalvageable in the Marine Quarter. The city official reiterated that there was no other solution than razing the area and rebuilding it.[109]

The project was commissioned to Gérald Hanning, who brought back the design principles of Le Corbusier's cité d'affaires without linking it to the heights. Hanning proposed to reduce the number of motor vehicles in the quarter by designating a peripheral route to transit traffic. Treated as a tabula rasa, the area was reorganized with tall blocks placed perpendicular to the casbah, with the highest structure at the tip of the triangle extending to the sea (Fig. 27). Hanning's rationalization of this decision focused on providing intriguing city views from the water and sea views from the hills. Four to five thousand people would be resettled in the new housing (the remaining population was to be transferred to the new projects in the Bab el-Oued Quarter), and the densities would not exceed four hundred persons per hectare.[110]

Hanning's project did not lead to any of the turmoil Le Corbusier had experienced two decades earlier. It was approved with great pride on the premise that "the orthogonal conception of the buildings will give the quarter an agreeable ambiance while providing for large open spaces between the buildings."[111]

Hanning proposed a "historic" enclave amid the entirely new buildings, a quiet spot between the two mosques below the Place du Gouvernement. Isolating the historic monuments from the modern quarter

Figure 27.

Gérald Hanning, project for the Marine Quarter, photomontage, 1959.

would put an end to their "suffering" and give them back their religious and artistic value, according to the architect. The Place du Gouvernement was to be enclosed on the north side by a horizontal block four stories high. Considering the area between Avenue du 8 Novembre and the foot of the casbah a transition zone, Hanning laid out here a network of short, rather narrow streets lined with modern, courtyard houses. In another attempt to relate to the casbah, the architect allowed for small shops on the ground level of the tall buildings that would correspond to the scale of souks and hence make the transition between the old city and the new quarters smoother.[112]