6

Neighbors

The day I was born . . . I heard all these different women, different names —like in those days you weren't born in the hospital, you were born at home, and I heard them speak about Mrs. Moriah, Mrs. Tracy, Mrs. O'Brian, Mrs. Silva, Mrs. Riposa, and Mrs. Filotta, all those different names, I said, "Doctor, hey, doc, what kind of a place is there where all these people of different nationalities come to help this old Black woman with her baby?" And he said, "This is West Oakland." And I said, "Well, jeez, West Oakland really must be a heaven on earth. It must be a really fine place."

Royal E. Towns

The pioneers were neighbors of many national, ethnic, and racial groups; scattered throughout the city, they knew nothing of a ghetto. In fact, ghettos were nonexistent in all Pacific slope cities until World War I, and, in San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley, even beyond that date. This was also true in southern cities, as well as in Boston, New York, Chicago, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Cleveland, and Cincinnati. Thus we must revise the popular notion that the ghetto is the usual physical setting of Black urbanites.[1] In San Francisco, the different neighborhoods mirrored the social and cultural complexities of the pioneers. As the city grew, and specific sections like the waterfront and the entertainment district appeared, complex residential locations became the pattern for Afro-Americans. These areas were located in different neighborhoods and, later, in East Bay municipalities as well. Their distribution indicates that Blacks were thoroughly familiar with the entire Bay Area.

Early San Franciscans lived near their workplaces, within walking

distance of the original settlement, Yerba Buena, in the midst of the business blocks. As the population rapidly increased, the city spread south of Pine Street, beyond Market Street, west to Nob Hill, and across the bay to Berkeley, Oakland, and Alameda. Real estate developers filled the swampy terrain at the bay's edge, leveled hills, extended streets, and erected buildings.

Initially, San Franciscans found accommodations along the waterfront that stretched from south of Market Street around the tip of the peninsula and west almost to Fort Mason. If not on the urban perimeter, near the foot of Broadway, they dwelled in central business blocks along Montgomery, Kearney, and Dupont (later known as Grant). Some resided on Market Street, the city's widest boulevard, which ran diagonally southwest from the northeast tip of the peninsula. They dwelled on east-west streets like Pacific, Washington, and Clay, and later on the routes south of Pine, and on secluded back lanes like Hinkley, Pinkney, Scott, and Stone, in houses and flats, above shops, and in rooms for boarders.[2]

Throughout its history, the city's many hills have been "barometers of wealth and position." Beginning in the seventies, silver kings and railroad barons built palaces atop Nob Hill. Below the summit dwelled the moderately well-to-do. Still lower, businessmen, tourists, transients, and various citizens found situations in the downtown hotels, in lodging houses, and in ethnic enclaves. After 1906, affluent San Franciscans occupied the expensive hotels and apartments on Nob and Russian Hills, and the less fortunate inhabited the slopes.

Even with the development of the flatlands south of Market and Pine in the 1860s, and the advent of cable cars in the following decade, San Franciscans remained neighbors within walking distance of each other. They preferred living in a tightly packed cluster in the midst of businesses, shops, and offices, remaining between Van Ness and the waterfront until the earthquake and fire.

Blacks also inhabited the walking district of nineteenth-century San Francisco. Some lived near the waterfront, especially in the 1850s. Others resided in the entertainment districts, such as the Barbary Coast and along lower Broadway. A few lived in Spanish-speaking enclaves near Kearney Street and Broadway. Most stayed around the residential area at Broadway and Powell (Fourth Ward) and, after 1870, in the artisans' and workingmen's districts south of Market near Third Street. Table 7 gives their residential patterns and distribution in 1870. The difficulties of enumeration in a large city were particularly apparent in Ward Four, where residences, businesses, churches, government offices, and Chinatown were all jammed together.[3] Unlike the Blacks, the Chinese, considered by contemporaries to be the most foreign of foreigners, lived in a few square

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

blocks in the eastern part of Ward Four. But as late as 1940, the Black San Franciscans maintained their dispersal, spreading out with the city's population to new areas of the metropolis.

The changing waterfront reflected San Francisco's development in shipping and transportation; its growth marked the formation of a metropolitan area. More and larger piers and wharves penetrated its waters as the city expanded, and its waterfront was lined by a variety of ocean-going vessels, river steamers, ferries, and smaller craft, crowded with a hodgepodge of wheeled vehicles on shore, and populated by tourists, adventurers, hackmen, and seamen. The piers, which extended the city into the bay, and the variety of people highlighted San Francisco's interdependence with the far west and the world. In the twentieth century, the waterfront functioned even more as a zone of transition for the metropolitan area. Oakland possessed a substantial waterfront of its own, where oceanic vessels docked and local ferries landed. It was a familiar sight for East Bay-bound urbanites, commuting workers, and East Bay residents out for a night in San Francisco.[4]

Black sailors inhabited this, one of the roughest, most notorious waterfronts in the United States, from pioneer days. In 1860, 16 percent of San Francisco's Afro-Americans lived there, often because of connections with sea travel, along with newcomers and other residents. Boarding-

house keepers maintained accommodations, and also provided banking and employment services. Colored sea rovers, cooks, and waiters resided in these establishments, some of which were run by Afro-Americans.

The Golden Gate Boarding House, probably at Broadway near Sansom, accommodated thirty Blacks, mostly mariners and cooks, in 1860. At the foot of Broadway, Abraham Cox, a seaborne waiter, ran the Pioneer Seamen's Boarding and Lodging House. In 1866, John Callender, another former seamen, assumed control of the establishment. Callender, his family, two Black sailors, and thirteen lodgers from Europe and the United States lived there in 1880. As the seasons changed, so did his customers. When the whaling fleet arrived in one autumn, a newspaper reported: "Colored gentlemen of every shade frequent his hostelry, and there remain until their hard-earned dollars have finished."[5] This milieu was as harsh and violent for the ordinary seaman as his conditions of work, particularly in the nineteenth century. Mariners, who had few rights until the twentieth century, probably suffered more if they were Afro-American, as that group could not rise through the ranks and become officers until well into the twentieth century. They remained ordinary seamen, just as Negroes on shore were destined to occupy menial positions all their lives.[6]

When they came ashore, the Black seamen were prey for avaricious boarding-house keepers and were likely to be shanghaied. In 1873 Edward J. Scott, a ship's steward, was drugged and robbed after one beer in a resort appropriately named Hell's Kitchen. Aurelious Alberga recalled a saloon, The Last Chance, where a trap door was used to kidnap unwary sailors. Hoodlums or "footpads" waited outside the "blind tigers" (illegal saloons without liquor licenses), dance halls, dives, and underground melodeons.[7]

These conditions changed somewhat as seamen's unions emerged and after reforms in working conditions, beginning in the late nineteenth century. Equally important, the waterfront's role changed. An urban transportation revolution led to more warehouses, wharves, and factories, and fewer accommodations on the waterfront. Thousands of rush-hour commuters passed through these sites every morning and late afternoon.[8]

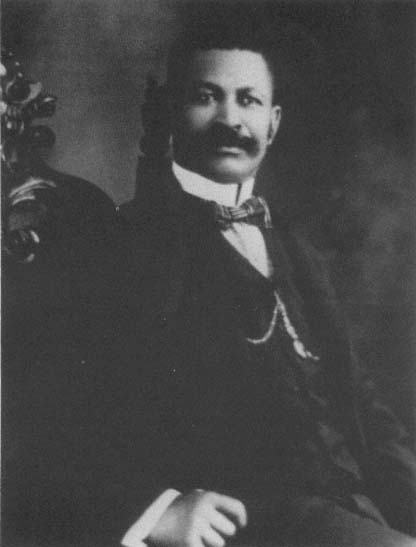

In the twentieth century, fewer Blacks inhabited the waterfront, but transients and seamen still spent time there. When trains supplanted passenger ships, Blacks worked as redcaps, cooks, waiters, and porters, while others became newspaper vendors, bootblacks, and lodging-house operators. They congregated near the transbay terminal, at the railroad depot on Third and Townsend, and across the bay on Seventh Street and near the Oakland Mole, where the trains crossed the bay to San Francisco.[9] At such active spots, Afro-Americans learned of distant places and gauged the variety of citizens of the metropolis. When William E. Towns, an early settler who worked on the trains at the turn of the century, took his

youngest son, Royal, to the Ferry Building, he explained the workings of the metropolis, pointed out a clamshell dredge, and, as Royal recalled, informed him that the vessels had names for identification.[10] Like William Towns, the Black inhabitants and workers of this zone served as bridgeheads to the distant world for isolated Afro-Americans on the Pacific slope. They taught Negro urbanites of the faraway places whose vessels, products, and citizenry made San Francisco a worldly spot.

The famous entertainment districts were another dimension of city life. The Barbary Coast and the Tenderloin housed both permanent inhabitants and tourists and transients. The oldest entertainment area, the Barbary Coast, matched in notoriety New Orleans's Storyville. It was linked with the waterfront by resorts on Pacific and Broadway streets and was bounded by Stockton, Kearney, Broadway, and Washington. In its heyday the Coast possessed "a few dives . . . patronized by negroes and drunken sailors, and where white and colored women of the lowest class [were] employed as waitresses." Similar places lined the streets near the bay south of Market.[11]

As the Coast declined in importance in the nineteenth century, spin-offs appeared on Morton Street (now Maiden Lane) near Union Square and along Dupont between Bush and Pine. On Berry, Morton, and Dupont streets, "the windows are left open, [and] half-naked and brazenfaced, painted prostitutes are seated at pianos playing and singing lewd songs, while others are standing at the doors in tights inviting every passerby to enter." Men of all ages, messenger boys, and policemen collecting graft entered the resorts that came to form the Tenderloin.[12] In the 1870s a new entertainment district emerged along Market Street near Third and Fourth, amidst hucksters, charlatans, patent medicine dealers, and actors and actresses from the theatres near Union Square. In the twentieth century, East Bay cities, seaside resorts, and new neighborhoods possessed night clubs and vice centers. Regardless of their location, the nineteenth century resorts were crowded and noisy at all hours.

From pioneer days, Black San Franciscans participated in the life of the entertainment districts. Their involvement ranged from jobs as entertainers to the usual positions as cooks, waiter girls, and porters, to roles as rounders or "sports"—swaggering urbanites out for a night of good times. Some Black workers and members of the sporting crowd won a measure of fame, success, and independence, while others earned little money and less recognition. They engaged in legal and illegal activities in a milieu where respectable and underworld citizens met and commingled in search of good times and profits. As in the ordinary business and workaday world, racism and discrimination limited Afro-Americans' opportunities and dimmed their successes.[13]

Some Afro-American prostitutes lived on side streets with co-workers of every nationality. In 1880, a few Black prostitutes occupied a Morton Street address with thirty-five other prostitutes; a few more resided several blocks west of the Coast, on Morse Place, and one lone Black prostitute dwelled with six white women, a housekeeper, and a boarder, at 502 1/2 Broadway.[14]

Blacks who won a degree of fame in the districts inspired the anonymous urbanites who toiled as porters or as waiter girls. Deacon Jones gained recognition and respect as the vigilant bodyguard of the operator of the Bella Union, a famous resort on Portsmouth Square, in the 1870s and 1880s. Another negro served Calico Jim, a Chilean, in the same capacity. John Tuers, a Black minstrel and pistol marksman, became famous among the sporting crowd after his pistol discharged in Snug's during a brawl, killing a well-known theatre manager. He was acquitted at the second trial. The "large attendance of theatrical and sporting men," and the favorable testimony of witnesses, showed the respect and support a Black person could get in a milieu whose members showed considerable loyalty to one another.[15]

Black-owned saloons and night clubs drew Afro-Americans along with other city dwellers to the entertainment districts. Gamblers were to be found in the resorts on Broadway and Pacific streets, and in 1865 the Elevator complained, "We can scarcely go into a place of entertainment of any kind but we hear the falling of cards, the rattle of the dice-box, and the oaths and imprecations which usually accompany such 'amusement.'" "Match games" around the billiard table were the rage in the 1870s. Some church members were said to spend "half their time and all their money in the Chinese Lotteries."[16]

Scattered throughout the city, the Black resorts were never numerous or close enough to form a distinct Afro-American district. A traveler of the 1860s and 1870s might visit The Iron Clad at 420 Pacific, near Sansom Street; at the Lincoln Exchange, at 823 Washington near Stockton; in William H. Hall's billiard saloon on Mason near Vallejo; or at Snug's, at Powell and John streets.[17] Later in the century, Black saloons and clubs moved with the expanding city and the newly emerging entertainment areas that, in the San Francisco tradition, were adjacent to residences. The Arcadia Club rooms, at 11 Stockton (near Market), offered drinks, cigars, and billiards. South of Market Street, Black clubs of the 1890s included the Acme at 668 Mission Street, the Unique Saloon and Club Rooms at 189 Jessie, and The Lotus, featuring gentlemen's private club rooms, at 24 Third Street.[18]

In the twentieth century, Blacks desiring drink, companionship, or diversion went to Purcell's on the Barbary Coast, the Bancroft Cafe at 236

Townsend Street, or the Cafe Dixie at 750 Pacific Street. In West Oakland, Blacks met at several places along Seventh Street near the railroad tracks. Some of these places were important centers for Afro-American song and dance. Purcell's, for example, drew slummers and celebrities out for a night on the town, including the famous Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova, and her escort, Arnold Genthe, the San Francisco photographer, one night around World War I.[19]

Night club men, entertainers, boxers, bodyguards, and waiter girls lived the bohemian life of the entertainment districts. Knowledgeable of the various ranks and customs of this complex milieu, skilled raconteurs and entertainers, known and respected among the denizens, they experienced the freedom and variety of acquaintances their sensitive natures required. They moved on from one resort to the next in an evening on the town in the same way that they shifted from one city to another, experiencing the freedom, sense of adventure, and allure of glamor that characterized these urban locales.[20]

Like the waterfront, the entertainment districts provided a freedom and gaiety that lightened the burdens of Black workers and that gave San Francisco drawing power. The glamor and bright lights both enticed sinners and slummers and provided opportunities for the occupants of Morton, Pacific, Broadway, and Market Streets. The districts drew entertainers from as far as the Atlantic states and Europe and audiences from the entire Pacific slope; they also provided graft for policemen and civic officials. Political ties made it possible for the districts to exist in open defiance of conventional standards until Prohibition.

After the entertainment and waterfront areas, ethnic enclaves were a third element in San Francisco life. Because of cultural ties, and to escape white racism, a handful of Blacks resided in the Mexican, Italian, and Chinese enclaves of the city center. There were a number of national, ethnic, and linguistic neighborhoods or enclaves, including Chinatown, unique among U.S. cities, which struck visitors as "a small section of an actual Chinese city." Parts of the downtown reflected Spanish-Mexican, Irish, Italian, and later Japanese influences. The ethnic districts date from the 1850s and still exist today. Some were distinctive in architecture, while others blended with the drab buildings typical of the urban settlement. Frequently overlapping one another and dispersed above stores and behind businesses, the clusters of foreign-born imparted a cosmopolitan quality to San Francisco's architecture, streets, cuisine, and tenor of life.[21] Chinatown, the Mexican quarter, and the Italian settlements in North Beach and on Telegraph Hill stemmed from rapid and recent settlement by foreigners who wished to cling to their cultures. The desire to recreate past settings expressed itself in the clustering of foreign-born, in architecture

reminiscent of distant homelands, and in the languages heard in those areas.

The contrasts between the ethnic neighborhoods resulted from the fact that, aside from a desire for money and residence in the same city, San Franciscans lacked a common cause or background. The communities distributed through the downtown blocks represented both the residents' diverse interests and their heterogeneous backgrounds. The singularity of the metropolis, particularly before the earthquake and fire, lay in its polyglot character, established several decades before the "new" immigration to and the rise of foreign-born ghettos in eastern cities.[22] Living in these enclaves shaped the lives of some Blacks and attracted others. Some pioneers lived among ethnic groups with common cultural and linguistic ties. Blacks with Spanish surnames and Central and Latin American origins occasionally lived with Mexicans, Panamanians, Peruvians, and Portuguese.

Infinite combinations of heritage and culture resulted in a region newly colonized by varied ethnic and national groups, where individuals associated with one another according to their inclinations. Fifteen Afro-San Franciscans resided with Mexican and Spanish-surnamed urbanites near Kearney and Broadway in 1880. A foreign-born Black was apt to be of African descent and Central American background, or a dark-skinned Iberian, or not Black at all, but a Hispanicized Indian, whose dark complexion confused the census taker. Determining a resident's background and racial heritage is difficult, if not impossible, for the contemporary scholar, just as it was for the federal census enumerator.[23]

The area around the 500 block of Broadway reflected the mix of nationalities and the way their neighborhoods overlapped. Although part of the Barbary Coast, and situated on the edge of Chinatown, the area housed a number of Central Americans, Latin Americans, and Italians on Kearney, Hinkley, and Pinkney streets. It also had a governmental character, as the county jail was located in the 500 block. The dwelling at 522 Broadway represented in microcosm San Francisco's mix of nationalities, races, and linguistic groups. A Black cook from Peru named José Seminario, his Panamanian wife, their four children (all but one born in Panama), and a Mexican boarder (designated "mulatto") lived at this address. A Black Panamanian with the family name of Cajar and two Mexican Black women with Spanish surnames shared the site. In the various apartments Chileans, European-born Irish, Italians, and Germans, and United States citizens mingled. The same pattern was found offshore. The U.S.S. Pensacola, which was anchored in the bay, was home for several foreign-born Blacks, principally from the West Indies and the Canary Islands.

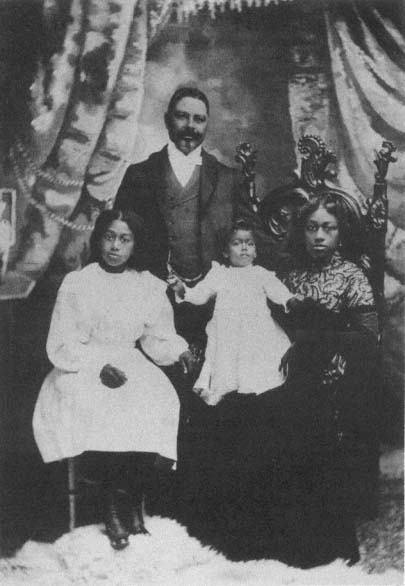

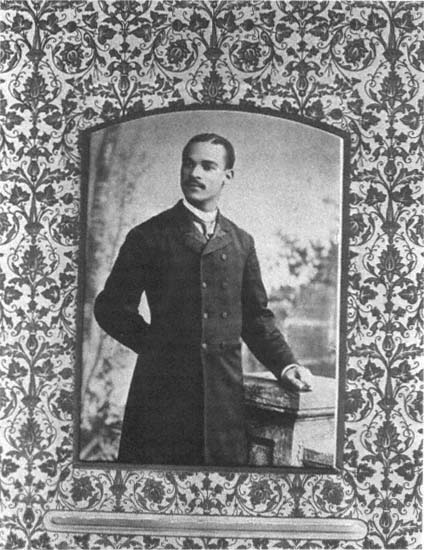

William E. Towns exhibits the refined manner typical of Black pioneers. He had ample

reason to pose proudly; head of a large family, he knew some Spanish and Chinese,

was|an agent for the San Francisco Elevator, and was treasurer of the Brannan Guards,

a Black military society. In the five decades he lived in the Bay Area, Towns worked as a

cook for the transcontinental railroad line under construction in the Sierras, as a porter

on the steamer Princess, and on various Pullman trains. He also preserved photographs

of his family and travels, some of which are now in the collection of his son, Royal

Royal E. Towns Collection.

A stereotypical portrayal of an Afro-American from the early twentieth century. The white men

have individual characteristics-moustaches, different kinds of hats, eyeglasses, and facial wrinkles.

The Black man's face is more of a mask, a mark of his inferiority, and his white coat and brushes also

signify his low status. Such cartoons appeared regularly in newspapers and magazines.

San Francisco Chronicle, August 5, 1914.

This unidentified woman left a striking image of a successful late

nineteenth-century Black. Consider the amount of time and work

that went into preparing her hair and clothing, accumulating

money for the jewelry and the richly-tiered dress, and cleaning

and maintaining the apparel. Note the material at the collar and

cuffs- there are pleats, lace, and possibly ruffles. The front of the

bodice and bottom of the skirt are also decorated and bordered in

different fabrics. Certainly the photographer at the Elite studio on

Market Street was technically accomplished, but the serene

confidence and beauty of his subject made possible an image

that is still arresting after a hundred years. Courtesy of

Bancroft Library.

Captain William T. Shorey, from Barbadoes, went to sea, ended up in San

Francisco, and commanded whaling vessels. At the turn of the century he and his

wife, Julia Ann, and children, Zenobia Pearl (left) and Victoria Grace, spent many

months at sea. The richness of this studio portrait suggests the prosperity

some residents attained. California Historical Society.

Photograph albums were often a standard size. A pocket-sized one such as this is rare.

Walter L. Gibson Collection.

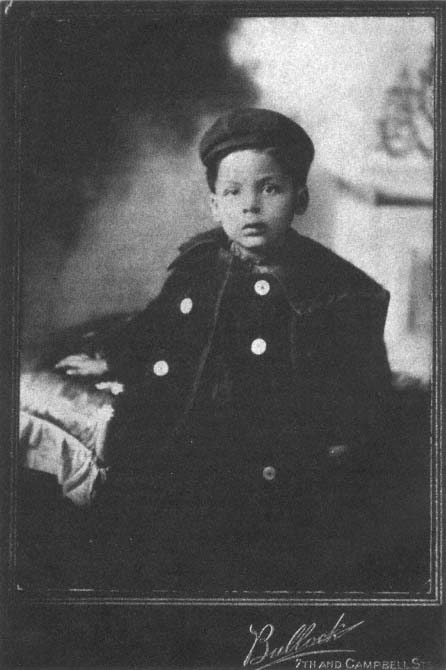

Royal E. Towns, in one of several children's photographs in his family collection.

These photos reflect Black parents' love and adoration of their children. Royal Towns

preserved family records and became an avid photographer, passing these

documents and interests on to his descendants. Royal E. Towns Collection.

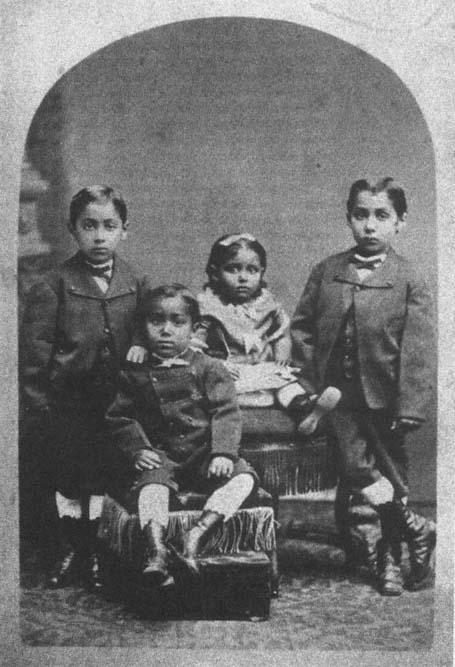

California-born children of William E. and Alice Rochford Towns, who came to the

Bay Area in the 1850s. From left to right: Wallace, Henry, Nellie, and William.

Royal E. Towns Collection.

An unidentified cosmopolite. Royal E. Towns Collection.

Charles H. Tinsley displays the bearing suitable for a Palace Hotel bellman. He

was one of the employees who was fired in 1896 and replaced by white men. He

later worked as a butler, waiter, and insurance salesman. This gentlemen also

liked to perform in Shakespearean productions. Lora Toombs Scott Collection.

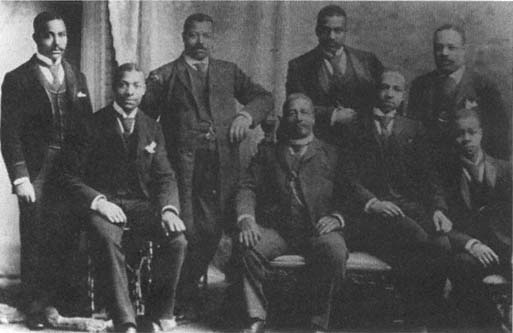

This Butler family portrait of the father and his sons shows the pride, sense of poise, and formal

bearing of pioneer urbanites. Standing (left to right): Abraham Lincoln, John Hanson, Jr., Floyd,

William Wesley. Seated (left to right): Charles Sumner, John Hanson, Sr., Walter Archibald,

and Benjamin Franklin Butler. Circa 1905. Courtesy of Bancroft Library.

Kate Grasses enjoyed some financial and job security as a postal

employee. Born in California, she was the granddaughter of Reverend

Jeremiah B. Sanderson, who migrated west in the 1850s.

Courtesy of Bancroft Library.

A well-dressed urbanite from the collection of Mary ("Mayme") Netherlands.

East Bay Negro Historical Society.

Ethel Terrell, from New Jersey, came to San Francisco in the 1920s as a pianist

and leader of the Syncopated Seven, on the Keith and Orpheum vaudeville circuit.

She settled down, continued to play, married, moved to Oakland, and

participated in Bay Area civic and social life. Ethel Terrell.

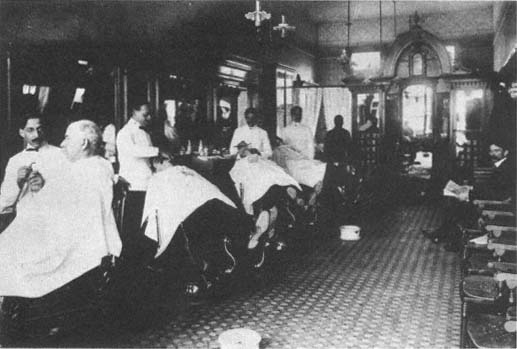

Many prominent pioneers were barbers. The Mint Barbershop of William A. Towns (standing

far left) at Tenth and Broadway in Oakland accommodated four patrons at a time. In such a

setting, barbers and customers discussed politics, sports, and the affairs of men.

Royal E. Towns Collection.

Black residents had a number of options on where to live in the city, one of which was to stay with the Chinese. Described as a "coal black" Spaniard, Ong Fung Yu lived with the Chinese for nearly three decades. Born in Spain and named Montoya, he went to sea, was shipwrecked off the Chinese mainland, and spent twenty-seven years in servitude in China. When his master emigrated to San Francisco in 1881, Ong Fung Yu accompanied him and then gained his freedom. Interviewed in the mining country, he explained in Spanish that he preferred to associate with his adopted countrymen, to wear their clothes, and to speak what had become as much his language as theirs. In the twentieth century, as well, Blacks lived with Chinese for various reasons.[24] Jean Ng, "a well-known character of San Francisco's demi-monde," resided at 520 Pacific (formerly Lester Mapp's Olympia and before that Purcell's), where the Coast and Chinatown met. Born in Kansas of Afro-American parents, she seems to have abandoned her ties to marry a Chinese rooming-house operator and underworld figure. When she died shortly after her husband, her adopted people claimed the body, prepared it for the funeral, and interred it in their cemetery in 1934.[25]

Few Afro-Americans went that far, but some associated with or, if necessary, claimed to be foreigners. Occasionally traveling musicians roomed with Chinese to avoid white discrimination. "There used to be a hotel next to the Orpheum on O'Farrell Street," Ethel Terrell, a bandleader and pianist, recalled. "That's where I stayed. And then as now people would come in San Francisco and didn't know where to stay, you stayed in Chinatown because they would always receive you. The Chinese would always let you stay anyplace where other people would not accept you." At least one informant, drawing upon her Panamanian background, assumed a Spanish identity to find accommodations for her large family in San Francisco.[26]

More typical were the Black individuals and families living on secondary streets or back lanes near Broadway and Powell and behind the Palace Hotel on Market Street. Prosperous Blacks resided on Sacramento and Washington Streets in the Fourth and Sixth Wards. In the 1870s newcomers inhabited the long narrow streets of Minna, Tehama, and Natoma, a few Black families to a city block. A total of four Afro-American families lived in the 1100 and 1200 blocks of Clay Street among German- and American-born residents in 1880. Similarly, the 100 block of Tehama housed ninety-seven whites, eight Chinese, and eight Afro-Americans.[27]

The largest contingent of Black pioneers (nearly 33 percent) inhabited the Fourth Ward (between Chinatown and Russian Hill) in 1880, but they were nonetheless widely dispersed. On Auburn Street fourteen Afro-

Americans lived among 103 urbanites, including Irish, West Indians, Germans, Mexicans, and Italians. Even on Stone Street, off Washington and Powell, the high percentage of Negroes (thirty-four of fifty-three citizens) resulted from two Black boarding houses located in this narrow lane. More commonly, Blacks lived in frame buildings next door to whites, sometimes sharing homes with them.[28]

A number of Afro-American gathering places, including the three Black churches, sat on the east slope of Russian Hill west of Chinatown. The two Methodist churches were on Stockton near Sacramento and on Powell near Jackson. The Baptist Church was also on Powell, between Bush and Sutter. Young Men's Hall, Prince Hall Masonic rooms, and billiard parlors were found on Broadway or on Pacific near Powell. The traditionally Black-operated boarding houses, one at 28 Stone Street and another at 1109 Stockton Street, were nearby. While the twentieth century brought important new developments in Black residential patterns, the Afro-American pioneers remained scattered over the metropolitan area.[29]

Across the Bay in West Oakland, Berkeley, and Alameda, Negroes similarly lived among native and foreign-born whites. John T. Callender, Ezekiel Cooper, and Jeremiah B. Sanderson lived in the East Bay in the late nineteenth century. Other Black pioneers soon followed, most of them living near the railroad terminals and the harbor west of downtown Oakland. The West Indian sea captain, William Shorey, and his family resided at 1774 Division Street. Their neighbors included an actor, a marine engineer, and their families (at 1778); a Swedish-born boilermaker (at 1770); an English railroad car repairman and three lodgers (at 1768); and an English railroad foreman and his family. All were white.

Near Brush Street, just south of the railroad tracks that ran down Seventh Street (where the elevated Bay Area Rapid Transit runs today), lived a number of Afro-Americans. A cook from British Guiana and his family inhabited a one-story frame house at 804 Brush. Across the street at 805 lived a carpenter, his wife, and their in-laws. A little way up, in two attached flats, were another Black couple and three boarders and lodgers (one white). A white Irish domestic probably owned these dwellings at 812. Further along lived a day laborer, his wife, grown children, and their spouses (860). Two Black families shared a two-story dwelling around the corner on Fifth Street (721), and on Sixth Street Afro-American families occupied one, one-and-a half, and two-story frame structures (713, 721, 758, 760, 765).[30]

These Black living trends call for an explanation, particularly in the older urban area. In a city famed for its ethnic neighborhoods and heterogeneous population, no "Negro quarter" existed. The Chronicle observed this in 1904, pointing out that San Francisco's Blacks were the

prosperous descendants of pioneer servants and businessmen. According to J. S. Francis, the editor of the Western Outlook , the reasons for this were simple. Colored citizens were "allowed to rent in most parts of the city" as "no strong color line [was] drawn in this city." Their singular status, he claimed, resulted from the fact that "influential members of the race" actually discouraged "the undesirable element" from coming to the city and aided only those "negroes of education and general eligibility." The article is the only mention of a Black district, or the absence of one, in San Francisco until 1944.[31]

In a study of Bay Area Negroes during World War II, Charles S. Johnson, the noted Black sociologist, observed that until the 1940s "no rigidly segregated Negro community existed in the city." Unlike eastern cities, "Negro inhabitants were to some degree lost in the city's population complex." Even as, in the 1930s, they congregated along Fillmore Street, one site of today's ghetto, they lived among Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, and "sizeable groups of whites."[32]

Because before the 1940s Blacks migrated as individuals and over a long period of time, they scattered over a wide area. They found accommodations as single family units and as individuals, not as a large contingent of newcomers. On the other hand, we know that when thousands of Blacks suddenly entered a city, as in the east during World War I and in the Bay Area during World War II, the familiar ghetto resulted. (The same institution emerged when masses of foreign-born whites occupied American cities.) Discrimination, profit-seeking real estate agents, and housing shortages promoted ghettos more than did any desire of Blacks to live together. Varying occupations and specific preferences among Negro San Franciscans also accounted for their scattered locations.

The presence of dark-skinned inhabitants from southern Europe, Latin America, Oceania, and Asia, and traditions of cosmopolitanism enabled Blacks to enjoy uncommonly numerous options in terms of neighborhood locations. Black culture also assumed an important role in permitting their distribution in the city. American customs, institutions, and language were the heritage of the vast majority of pioneer urbanites, and, when merit and ability were the sole criteria, they found easy access to different sections of society. But merit and ability were not the only standards, and discrimination barred entry to some places. Yet to an extent their color also worked in their favor, permitting entrance to certain circles as servants and menials, jobs which would have been denied them if they were considered equals.

With their knowledge of the language and customs of the United States and San Francisco, the pioneers acquired job skills, a degree of literacy, and a variety of social contacts out of the reach of recently arrived European and Asian immigrants. Such foreign-born residents needed

years, if not generations, to acquire vital language and job skills and to adjust to the American urban scene, unless they possessed wealth, high social station, or professional training when they came to the U.S.

San Francisco and Oakland Blacks learned the accents, intonations, jokes, and vocabularies of their foreign neighbors. Royal E. Towns maintained that his association with a variety of urban dwellers allowed him to learn many distinctive speech patterns and idioms. He said that a uniquely cosmopolitan atmosphere existed in West Oakland (and the Bay Area) because so many national and ethnic groups shared a tradition of neighborliness, cooperation, and goodwill. To illustrate what a Black child might learn, he recited incidents and jokes in first an Irish and then a Jewish accent.

Towns told of visiting his son on a ship in Brooklyn Harbor in New York in the 1940s. Stopped by an Irish policeman, Towns explained that his son was in the merchant marine, but the Irishman, "with all the flannel on his tongue that he could possibly have, he said, 'No yuz don't,' he says, 'nobody goes down to the ship, and arders is arders.'" Towns then showed him his identification, indicating he was a lieutenant in the Oakland Fire Department and had a port pass for San Francisco. "'I don't give a damn who you are, you just don't go down to the ship,' he says, and 'arders is arders.'" Towns replied, "'You know something, you are the first Irishman that ever believed me. When was you born—in the year of the black potatoes or the year of the big wind?' And he said, 'Where did you get the blarney?' I said, 'Out where I live.' He said, 'Many Irishmen out there?' I said, 'Ha! I was born in old man O'Brian's house right next to Mr. Tracy's,' and I said, 'There's O'Boyle, O'Hallihan, McAllister, . . . ' and jeez, I started naming a whole gang of micks, you know, and he said 'Wait a minute, wait a minute!' He said, 'Hey, Pat, come here and take this Irishman down to the boat.' (Laughter.) It's all in knowing the language or the vernacular of the particular ethnic group that you live with. . . . This has happened in many instances in my life where I have utilized some of the things I learned from those kids down there [in West Oakland]."[33]

By contrast, Asian and European migrants sometimes balked at learning English, and often retained an accent or manner of speaking that evinced their origins. The accents and dialects, not to mention the languages, that characterized San Francisco were evidence of the recent arrival and distant origins of many of its inhabitants. While foreign newcomers attempted to preserve their traditions, Afro-American culture was not only American, but had been American for several generations. If it served their ends, Blacks learned the languages of the newcomers, thus acquiring a European and Asian veneer.

Asian and European immigrants, in fact, preserved their original

cultures while learning American ways in San Francisco, re-creating their homelands in their ethnic enclaves. Newcomers imported countrymen, foods, and goods to surround themselves with familiar remnants of home. Afro-Americans, on the contrary, felt little desire to bring anything but a bit of New Orleans, Philadelphia, or New York City to the far western metropolis. They were at home any place in the American city where prejudice did not make conditions intolerable; the variety of their neighborhood locations, and their eventual shift from the city center highlighted their familiarity with the urban scene much as their speech evidenced a native acquaintance with American culture. The dispersal of pioneer urbanites, and their shifting locations accompanying the city's expansion, contradict those who desire to see all Black urban life in the ghetto environment.[34]

In 1906, the earthquake and fire all but destroyed downtown San Francisco. Residents moved temporarily to the lightly settled Western Addition beyond Van Ness Avenue and to the growing East Bay, Oakland in particular. The city was quickly rebuilt, but large business blocks and expensive hotels rose where businesses and residences had been mixed. The well-to-do and the Chinese built stores and accommodations in the downtown districts. The growing metropolis penetrated the residential Western Addition and enveloped suburbs which were sometimes cities in their own right. The typical Black San Franciscan located in these expanding regions, inhabiting the rowhouses and flats along Bush, Pine, Sutter, and Post Streets, rooms above stores on Divisadero and Fillmore, or the larger homes of Oakland. East Bay residents, who depended on trolleys, trains, and ferries to travel to the city center, had overcome their inclination to dwell more than walking distance from downtown.[35]

By World War I the Bay Area's residential patterns had crystallized. This was partly due to the growth of industry in the East Bay, but transportation changes were also crucial to both the city's expansion and the new living patterns of Blacks. The introduction of cable cars in the 1870s accelerated the city's growth and settlement of the steep hills. Eventually electric trolleys and rapid trains enabled San Franciscans to live some distance from their workplaces in the city center, while an efficient ferry system hastened the growth of Oakland and Berkeley. The ferries traveled at regular intervals, and in 1912 carried 15,000 transbay commuters during each rush hour. The advent of the automobile and consolidation of the city's transportation system around World War I spurred suburban development. Construction of the Bay and Golden Gate bridges in the 1930s facilitated the movement of trains, trucks, automobiles, and commuters. As distinct commercial and residential neighborhoods appeared, the new mobility of commuters complicated matters.

Swiftly moving motorized transportation (public and private) obliterated distinctions between the city proper and its surrounding regions, whether suburbs, countryside, or seaside resorts.[36]

Bay Area Blacks took advantage of the residential shift and adopted the new life style, embracing suburban ways more readily than other urbanites. After 1906 a few relocated on Russian Hill, in the city center, and in the Western Addition, but by 1910 most Bay Area Afro-Americans lived in Oakland. In the 1920s, when San Francisco's total population outnumbered Oakland's by more than two to one, almost twice as many Blacks lived in Oakland as in San Francisco. Usually viewed as members of American society's rear guard, Blacks had adopted a life style that would not become the norm until the mid-twentieth century.[37]

In the nineteenth century, Blacks who lived in the city center for convenience's sake often used the pastoral East Bay for excursions and picnics. As early as 1880 nearly six hundred Afro-Americans lived in Oakland, constituting the second-largest group of Black city dwellers in the state. Oakland's rustic character disappeared during the economic boom of the 1890s, but the city retained a decidedly suburban atmosphere and, characteristically, a lower population density than San Francisco. The East Bay's proximity, suburban character, expanding economy, cheaper rents, and larger homes accounted for the more than 8,000 Afro-Americans in Oakland and more than 3,000 in Berkeley by World War II.[38] The Black migration to the East Bay in the 1890s also followed the rise of the white labor unions that excluded Blacks from their traditional positions (see Chapter 3). Afro-Americans found jobs quite readily on the trains which terminated in Oakland; as these positions were reserved for Blacks, discrimination forced them to adapt to new trends while whites stayed in San Francisco.[39]

The East Bay's cheap and available housing also caused many pioneer families to relocate. Though as a rule racism was not as rigidly imposed on Afro-Americans as it was on Chinese in California, it eventually affected Negroes' housing choices. There are no complaints about housing discrimination in the remaining copies of the nineteenth-century Black newspapers; probably San Francisco life was initially so rich that when discrimination occurred, it hardly mattered. Perhaps city folk were too busy seeking wealth to exclude Blacks from neighborhoods or even from households. At any rate the problem of discrimination in housing was first mentioned in a white newspaper in 1889.[40] Richard C. O. Benjamin, author, newspaperman, and political organizer, argued that San Francisco was as prejudiced as the south. "Right here in San Francisco," he exclaimed, "it is impossible for respectable negro families to rent homes except in certain communities." Eighteen years later, the Oakland Sunshine echoed this sentiment. "To live in either of the [Bay] cities, it is

almost necessary for you to own your own home; rents are high and real estate agents do not care to rent to Negroes." One advantage of suburban living was that homes could be purchased "at the price of a monthly rental." In the 1920s, an informant said, discrimination made it all but impossible to obtain anything but "rundown" accommodations in San Francisco.[41] In 1930 Black householders in San Francisco paid an average of five dollars per month more than their counterparts in Oakland, usually for less space. The East Bay's lots were wider than San Francisco's, making possible commodious houses, yards, and gardens, and room for children.[42]

A conscious choice of alternatives was evident in the move to Oakland. Rather than flee the metropolis because of job discrimination, expensive housing, and increasing racism, devotees of the Bay Area moved to new residential sections. Faced with limited opportunities, the Black urban dwellers devoted their time and energy to improving their immediate home environment, buying spacious houses in the East Bay or comfortable Victorian dwellings in San Francisco's Western Addition. The less expensive East Bay homes freed portions of householders' budgets to buy furnishings, plant flowers, and devote space to their children's play activities. The new suburban residential districts provided a quieter setting that contrasted with the expensive, crowded, noisy, downtown districts.

It is impossible to ascertain how many Blacks moved to the East Bay at the turn of the century. What is significant is that adoption of the suburban life style, based on motor transport, entailing residency in a neighborhood far from downtown, and implying an affinity for trees, flower gardens, and more space, distinguished the pioneers from the average American and from many San Franciscans. The pioneers embraced the new pattern more quickly than most Americans, white or Black, because they were flexible and willing to seek new opportunities to better their lives. They chose to enrich their home lives because other forms of advancement were not readily available. In the late nineteenth century, as working conditions worsened due to labor competition and chances for wealth dwindled, home and family became the new means of expressing ideals.

For newcomers to the Bay Area, the East Bay offered both jobs and an attractive physical locale that especially appealed to migrants from southern small towns and crowded, dirty eastern cities. Noisy, expensive, and exclusive, San Francisco repelled all but the most cosmopolitan and skilled newcomers; the high cost of living there also discouraged migrants with families. When single Black San Franciscans married, they moved to the East Bay for the welfare of their families. Most of the informants' parents left San Francisco to live in Oakland or Berkeley by 1900, and the informants themselves often purchased homes in the East Bay for good prices during the Depression.

The pioneers and their unique urban ways went relatively unnoticed by

contemporary observers and, perhaps as a consequence, have been neglected by scholars. They merit attention because they contrast with both the contemporary ghetto dweller and the average white urbanite of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; analysis of these pioneer suburbanites might shed light on the problems of metropolitan life in the late twentieth century. At the very least, study of their conversion to suburban living furthers our understanding of the historical origins of that way of life and its implications for whites as well as for Blacks.

Emphasis on the "problems" of Black and white urban life results not so much from careful analysis of the history of different ethnic groups, but from scholars' concern with social policy, crime, and health. The experiences of pioneer urbanites in the Bay Area show that the availability of different neighborhood locations can improve those aspects of urban life—given the right setting. While contemporary residents enjoy emphasizing the Bay Area's liberal, multi-racial, and multi-ethnic heritage, the region's history indicates a more complicated picture. Perhaps the city did accommodate versatile and literate Afro-Americans in the nineteenth century, but it was not so generous with Chinese of that era or with the Japanese in the twentieth century. And when large numbers of Black southerners arrived during World II, the Bay Area cities finally faced the problems that had plagued eastern cities since World War I. Black ghettos formed at Hunters Point, along Fillmore Street, and around Seventh Street in Oakland. The "Negro problem" emerged full-blown, and the area's singularity and belief in its non-racial ways disappeared. All the characteristics of ghetto life—high mortality rates, inadequate housing, and cirme—heralded a new phase for San Franciscans. Comparison of the two different urban patterns—those of pioneers and those of ghetto dwellers—should illuminate our understanding of each.[43]

The pioneer experience forces us to modify the usual portrait of Negro urban life and to take into account differences between cities and between regions. Analyzing Black San Franciscans' neighborhood locations shows the complexity of city life. Negro urbanites learned of the city's complicated functions and of the larger world outside it by living in or working on the waterfront. The entertainment and ethnic districts lent a bohemian, if not a licentious, quality and a degree of ethnic sophistication to Black life. From their neighbors, the pioneer Blacks learned to be sophisticated urbanites who valued lasting friendships based on childhood experiences and individual preferences, rather than on ethnic background. In many ways this freed them from some of the effects of racial oppression.

Such living conditions may have been the prevailing pattern on the Pacific slope, although much research needs to be done on this subject. Edward J. "Buster" Johnson, who worked on the trains along the Pacific

coast, said that there was little variation in Black life from city to city. "Up and down the coast, . . . Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles—it was all the same . . . Negroes lived the same as they did here all the way up and down the coast." There was also considerable freedom. On public transportation, for example, "you paid your fare and sat down and rode and you didn't have to ride at the back of the bus or somewhere else, just wherever you could find a seat. We didn't have none of that funny stuff like they had in the south."[44] Despite Jim Crow restrictions, Blacks seem to have been well dispersed in many nineteenth-century U.S. cities. The relationship between this living pattern and racial prejudice needs to be explored in order to compare the quality of Black urban life from region to region.

The Bay Area pioneers shared another characteristic with Negro urbanites outside the far west. While Black urbanites are frequently viewed as laggards behind the nation, they were in the vanguard in San Francisco and Boston. Starting in the late nineteenth century, Black Bostonians moved to the "streetcar suburbs" because of lower rents, lower home purchase prices, more pleasant physical surroundings, and less antipathy for their group. Boston and San Francisco Blacks moved to the suburbs at comparable rates, if only at the outset: "So far as increasing residence in the more open and healthful outlying districts is concerned, the Negroes have in the main fared better than the rest of the population."[45]

The benefits of urban life seem to have counterbalanced discrimination in employment, or so many Black San Franciscans believed—and their opinions must be weighed when we assess the effects of racism and the quality of their lives. If their childhood memories minimized racial strife and were a bit nostalgic for the cosmopolitan pre-ghetto era, their segregated social life reminds us of the restrictions they faced.