INTRODUCTION:

THE HISTORY AND POLITICAL ECONOMY OF BANARAS

To place in context the essays that follow, we begin with an examination of the "political economy" of the city—that conjunction of political, economic, and social structures which provided the context for historical events and processes. Not least important, in this respect, was the city's location—occupying that auspicious niche of land where the Ganges and Varana rivers meet. We tend to see the significance of Banaras primarily in terms of auspiciousness, in its function, that is, as one of the premier pilgrimage sites in the subcontinent. At the same time, however, we must remember that it was also the largest urban center in the eastern Gangetic plain (see map 1). Thus the political economy of this central place affected a densely populated hinterland with a high level of agricultural production. Furthermore, as the center of the Bhojpuri cultural region, Banaras provided a focal point for a vernacularly based culture that encompassed what is now eastern U.P. (Uttar Pradesh) and western Bihar (see G. Pandey 1983a for an interesting discussion of the potential of this culture for mobilization).[1] Within the city itself the population grew rapidly in the last half of the eighteenth century, coming to number about 200,000 for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—a good-sized urban site in the days following the decline of Mughal imperial centers.

Although the history of Banaras reaches back into the mists of time, tempting the historian to follow,[2] our narrative begins with the eigh-

[1] U.P. refers to that general area in the north Indian Gangetic plain and Himalayan foothills which underwent several name and boundary changes in this period. It was known variously as the two separate provinces of North-West Provinces (NWP) and Oudh; the combined provinces of NWP and Oudh; and finally the United Provinces. Since independence it has been known as Uttar Pradesh.

[2] Diana Eck, for instance, begins with the sixth century B.C. (1982:43).

Map 1

South Asia about 1785.

teenth century: it is in this century that new politicocultural alignments emerged which have profoundly affected the processes and people analyzed in this volume. Physically, too, the period produced most of the architectural landmarks that anchor the contemporary city. Such widespread construction became possible, in part, because much of the reli-

Map 2

North India about 1860. Stippled area indicates U.P. and Bhojpuri districts.

gious architecture of the city had been razed (c. 1660s) by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb (1657–1707). Following the pattern of a good Muslim ruler, he observed the dictates to build mosques in every city—in the process superimposing an Islamic city on the site of Banaras, which he tried to call "Muhammadabad."[3] Neither the name nor the "qasba" cultural style took root, however.[4] Instead, an alternative cultural collaboration emerged between an upstart dynasty, merchant bankers, and mendicant soldier-traders. It is to the impact of this collaboration that we now turn.

National, Regional, and Local Political Power

For our purposes, the most important elements of Banaras's political economy include its place within the larger political structures of the subcontinent (as these were expressed at the national, regional, and local levels); the composition of its economic cum social and cultural elite; and the characteristics of its population—as well as the relationships of these subgroups to each other. The significance of beginning with the eighteenth century as we establish a context for our studies stems largely from the fact that these elements of the political economy un-

[3] Stephen Blake has described this process, as observed by Shahjahan, in his essay (1986).

[4] See below; see also Bayly 1983 and R. Kumar 1977 for discussions of this qasba style.

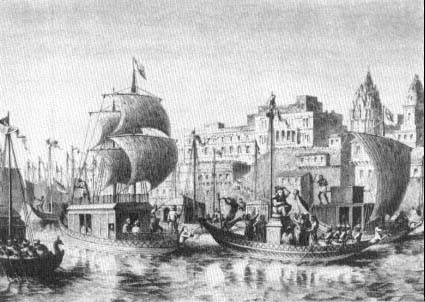

Fig. 1

Drawing of the river festival of Ganesh (elephant-headed god especially popular

with the Marathas). From Louis Rousselet, India and its Native Princes (1876).

derwent significant change then, prompted primarily by the ebbing of power and influence from the centralized Mughal Empire, which had dominated north India for two preceding centuries. Indeed, during the last half of the eighteenth century Banaras became "the subcontinent's inland commercial capital . . . [receiving] immigrant merchant capital from the whole of north India and [standing] astride the growing trade route from Bengal to the Maratha territories." Its strength came in large part from the integrated regional economy that had been achieved by the 1780s around holdings of the Raja of Banaras, based on a larger pattern for the period of "commercial development which arose within the agricultural society and then linked up with growing urban demand produced by the emergence of the new kingdoms" (Bayly 1983:104–6).

As the Mughal Empire declined, what Cohn (1960) has characterized as the "national level" political responsibility for Banaras came to rest, first, with the Nawab Wazir of Awadh and, by the end of the century, with the British East India Company. Just below this national level, actors at the regional level—what is usually referred to as the Mughal Empire's successor states—proved particularly important for

our narrative. But contenders for control moved rather easily during this century between the national, regional, and local levels of power, often using resources accumulated at one level to build claims for power in the next. While neither the research nor the space available allow us to discuss these eighteenth-century changes in detail, we should note that the most important actors moving among the levels of power included the Maratha empire in the west; the nearby Nawabi of Awadh, with its capital at Lucknow; and the family that came to be known in this period as the Rajas of Banaras, whose zamindari (estate) eventually encompassed the present districts of Ballia, Banaras, Ghazipur, Jaunpur, and Mirzapur (see maps 1 and 3).

Much of our narrative refers to Awadh and Banaras. But we should not minimize the interests of the Marathas in the old urban centers of north India: the military collaboration of the Marathas with the Nawabi against the Rohillas (in the hills of the area; see map 1) included a condition that, in return for their military support, the Marathas would acquire control over Mathura, Prayag (Allahabad), Banaras, and Gaya (B. N. Singh 1941:27); all were urban centers significant for their prominence on Hindu pilgrimage routes. While this Maratha desire to exercise direct political control was thwarted when the British replaced Awadh as ruler of the area, the Marathas remained culturally important in the city of Banaras itself. Reflecting their intellectual as well as their trading interests there,[5] Marathas financed much of the eighteenth-century Hindu reconstruction of the city, which encompassed dharmshalas (rest houses) for pilgrims, temples and feasting to support Brahmin priests, and palaces for themselves and their local kin and agents (and see fig. 1).[6]

Without treating in detail the political history or functional realignments that marked the eighteenth century, we must recognize the significance of the emerging economic and cultural collaboration between the Raja, mendicant trader-soldiers (usually referred to as "Gosains"), and the merchant-banker families of Banaras (whose most prominent members constituted a tightly knit oligarchy called the Nau-

[5] "Deccani pandits" had contributed substantially to Sanskritic studies from the sixteenth century on (B. N. Singh 1941:23); among the early documents prepared for the East India Company in the late eighteenth century was an unfavorable analysis of the trading deficit with the Maratha empire.

[6] Maratha immigrants in Banaras came to number almost 30,000 people by the end of the eighteenth century and "included traders (naik and Sipahi Nagar bankers), Deccani Brahmins and the retainers of the many nobleman who temporarily or permanently resided in the city" (Bayly 1983:137). Maratha-sponsored construction included the present Visvanatha temple in 1777, as well as the temples of Annapurna, Kalabhairava, Sakshivinayaka, and Trilochanesvara. A large number of the bathing ghats along the riverfront—such as Amritrao Ghat, Ahilya Ghat, Scindia Ghat, Bhonsla Ghat—were also built by the Marathas (B. N. Singh 1941:28).

patti). Although full histories of all three of these groups of collaborators await closer scholarly scrutiny, we do know something about each.

The Gosains—the largest owners of urban property in Banaras in the late eighteenth century—have been identified as possessing several important characteristics. They formed a "religio-commercial sect, militarized to some degree, and organized according to the guru-chela principle,"[7] recruiting without regard to caste, and thus admitting "any person of abilities among them" (Kolff 1971:213–17). This combination of religion, trade, and military prowess may not be as peculiar as it seems at first glance. Moneylenders and merchants worked together to establish credit as well as transport for a particular shipment of goods to a far-flung urban destination; since "long distance trade needed armed protection, the dividing line between trading and soldiering must have been a thin one" (Kolff 1971:217; Gordon 1971:219). As the "principal merchants" dealing with the Maratha empire in the Deccan, these Gosains "resided at Benaras and transported their goods to Mirzapur, there to sell them to other members of their own sect who came annually from the Deccan to buy them" (Kolff, quoting Shakespear 1873:17–21). Thus the Gosains possessed a commercial edge on other merchants, able to utilize their pilgrimage networks for trading purposes. At the same time, they could amass the capital needed for trade through inheritance procedures, which permitted them to pass on a larger share to one chela (Cohn 1964:175–82). To these advantages, bestowed by their unique organization of resources, they added other significant characteristics. Numerous in Banaras, they could call on religious connections with other sadhus to be reckoned a major force in the city.[8] Indeed, they constituted "a body of brokers between different social groups. They attracted veneration from the mass of the people and also had a close hand in the running of the merchant communities" (Bayly 1983:181–84).

As for merchant-bankers, H. R. Nevill notes, in the gazetteer produced for Banaras early in the twentieth century, that "in the palmy days of Benares many large fortunes were accumulated, so that there is a good deal of money in the place." The banking family firms described in the Gazetteer include many whose histories are suggestive of the ways in which ties were established between Banaras and other trading centers, as well as the paths to political and social influence within Banaras itself. One was a Maratha family who benefited from

[7] The term refers to a highly disciplined teacher-student relationship that implies much more: the chela is at once student, follower, and disciple of the guru.

[8] The Magistrate in the early nineteenth century counted the Gosains as "one-fourth" of the city's inhabitants; to reach this figure he must have included all those who appeared to be mendicants. Boards Collections no. 7407:298.

the Deccan's elaborate trading, intellectual, religious, and political ties described above. Another, a family with "extensive dealings with the Bengali community," had originally owned the site of Fort William (the military center of the East India Company in Calcutta). Once settled in Banaras, this latter family proved to be important local citizens, giving land for the Grand Trunk Road, "proving their loyalty" during the Mutiny/Revolt of 1857, and becoming "noted for their public spirit and charitable works . . . the present heads being honorary magistrates and members of the municipal board." Another family came from Jhind, where they had held the hereditary office of kanungo (revenue official); they had followed the former Mughal royal family to Banaras and by the early twentieth century boasted both an honorary magistrate and a government treasurer. Yet another firm was started by brothers resident in Allahabad; their sons and grandsons had become "connected by marriage with most of the leading Benaras families." Two banking families were noted as well for their "dealings in silk and other costly fabrics" and as chaudhari[*] (headman) "of the kincob merchants" (a type of silk fabric: see DuBois 1987). Other large bankers functioned as "considerable landowners" in the district (Nevill 1909a:53–55).

Such merchant-bankers were drawn to Banaras for the commercial opportunities provided by this trading center located on the main west-to-east trade route. They provided important connections with their constituent groups back home in Jhind, Allahabad, and the like. To regulate so complex a trading and banking world as that of Banaras, they further organized internally. Building on the Naupatti ("Society of Nine Sharers")—which had become "a self-perpetuating oligarchy of status which no aspiring family could enter"—other merchants and bankers grouped themselves in a structure whose pinnacle was occupied by the Naupatti families. The resulting linkages were based variously on organization within a particular trade, among those trading in a particular region, or among those performing a particular function in the trading structure. Most particularly, all shared conceptions of status and mercantile honor (Bayly 1983:177–80).

Especially important for us is the emergence of the Raja of Banaras as the regional ruler of the area.[9] Bayly notes that, particularly during this period of political flux, the establishment after migration of the great agricultural clans of Bhumihars or Rajputs led to the creation of new commercial centers. Building on the model sketched by Richard Fox (1969), Bayly suggests that a two-stage process linked economic development to the political emergence of a raja from the previously democratic clan organization. Working from a relatively small estate

[9] See the model developed in Bayly (1983:95–96).

(zamindari), between the 1730s and 1750s, this Bhumihar family[10] used its position as tax official for Awadh to become zamindar for most of Banaras province, and to gain the title of Raja.[11] Functioning as the virtually independent regional-level ruler, it paid only a lump-sum tax or tribute to Awadh. What enabled the family to preserve this distance from Awadh was its own ability to profit from the changing economic and legal circumstances affecting control of land—particularly that introduced by the British (see Cohn 1960 for details)—as well as the interdependent relationship the family developed with the Banaras merchant-bankers for meeting Awadh's demand for tribute.

These histories of successful banking families, and the evolution of a landlord family into local dynasty, personalize the larger trend of shifting economic and political structures which marks out the eighteenth century. If, as Bayly argues, the intermediate economy emerging in the eighteenth century rested on "the distribution of local political power expressed in revenue assignments" (Bayly 1983:52), then this ability of the banker-merchants to command resources located deep in the countryside gave them "considerable, if covert, political power within the state." It was not only that they had the capacity to float huge loans to the Raja when his tribute was owing to Awadh. It was also that they possessed important rural connections to generate such resources, mobilizing "shadowy groups of substantial rural men of capital."[12]

The Nineteenth-Century Cultural Pattern and Power Relationships

Local political power became intimately connected, as well, to cultural patronage (discussed in more detail in Part 1). The merchants and the Raja figured prominently in this patronage, which expanded at the re-

[10] The caste name is usually transliterated in British sources Bhumihar or Bhuinhar. (We have ignored Platt's transliteration of Bhunhar, which may be based on a different regional pronunciation.) This twice-born caste enjoyed high status throughout north India; exercising much influence, particularly in the rural areas, its members were prominent landowners and tenants with very favorable terms. The family that became Rajas was headed, first, by Mansa Ram (1730–38) and then by his son Balwant Singh (1738–70). The longevity of Balwant Singh was doubtless significant in consolidating the power of the family. Chait Singh succeeded to the gaddi (throne, seat of authority) in 1770. The power of the dynasty also helped to entrench the power of the Bhumihar clan in the area.

[11] This was elevated to Maharaja in reward for loyalty during the 1857 Mutiny/Revolt.

[12] For examples of occasions when he required large amounts of money, see IOL & R L/PS/10, vol. 173 for 1910, file 876; Winter to Dane, p. 2. (These "rural men of substance" had emerged from commercial development that linked consolidation with agricultural society to "growing urban demand produced by the emergence of the new [successor state] kingdoms"; Bayly 1983:104–7.)

gional and local levels as the Mughal Empire faltered. In part, such patronage conveyed legitimation for these emerging power-holders. Most important, the devolution of the locus of cultural patronage from the national to the regional and local levels, together with the ability to mobilize the intermediate economy, provided significant linkage between the newly emerging Hindu merchant elite, the regional political figure of the Raja of Banaras, and the artisans and others who made up the lower classes of Banaras.

The interaction of these power and culture relationships developed in ways unique to Banaras.[13] In the early eighteenth century, like many of the other "celebrated holy places such as Prayag (Allahabad) and Ajodhya," Banaras had been a "mughalizing city," owing much to the cultural patterns established first by the Mughals and then fostered by the Nawab of Awadh's court. The physical world of Banaras certainly reflected this mughalization—in its Muslim buildings, the establishment of muhalla s[*] (neighborhoods: see below), and the dotting of Muslim shrines. The social world, too, had been mughalized, with configurations of such urban functionaries as the "service types, sufi orders, pirs . . . and scribal groups." No doubt this mughalized style accounted, in part, for the strong ties established early in the career of the Banaras dynasty with the Muslim lower-caste groups such as the weavers.

Nevertheless, the pattern in Banaras, unlike that in other mughalizing urban centers in north India, changed so that, by the early nineteenth century, a Hindu tradition had been "reinvented"[14] to serve certain goals cherished by the triumvirate of power-holding groups in Banaras. More will be said, below,[15] about the importance of this reinvented Hindu style for the Raja of Banaras. Here it will suffice to point to the other actors in Banaras who could also respond to this reinvention, including the Marathas, the immigrant Bengalis, and those from the eastern U.P. countryside. The nexus of culture and power in nineteenth-century Banaras, then, was located in a reformulation of Hindu culture that drew together a disparate group of power holders. Such a style, nevertheless, made room for the substantial numbers of (generally lower class) Muslims resident in the city as well.[16] Equally important, this special amalgam that marked Banaras also protected it, to a surprising degree, from British intrusions, particularly in the early nineteenth century and again after 1910.

[13] I am indebted to Chris Bayly for calling my attention to the importance of explicitly emphasizing this point. The formulations quoted in the paragraph that follows are from a private communication dated 17 May 1987.

[14] In this term, Bayly is drawing on vocabulary and concept developed in Hobsbawm and Ranger, 1983.

[15] And in chapter 7.

[16] For a discussion of how this was accomplished, see below and chapter 7.

In recognition of the virtual independence of the Raja of Banaras, the British did not attempt to rule the area directly when they took Banaras over from the Nawab in 1775, but simply replaced Awadh as the national-level authority. Indeed, as a special mark of favor, the East India Company Governor-General, Warren Hastings, gave further rights to Raja Chait Singh, allowing him to coin money and administer penal justice ("A History," 1873:100–7). Hastings established a Resident there but did not interfere directly in the administration of Banaras until the pressures of war with France led him to make extortionate money demands on the Raja, who "rebelled" in 1781. Even then, the British simply replaced Chait Singh with his young relative, Mehip Narayan, whose claim to the throne was at least as compelling as Chait Singh's own. The rights to the mint and judicial functions were withdrawn, however, and by 1795 the Resident's administrative power had expanded greatly. This was symbolized by his permanent revenue settlement of the area and was officially recognized when the young and perhaps epileptic Raja signed away his independent authority to the East India Company in 1794.[17]

Consequently, during the nineteenth century the British administered the Banaras region directly, with the ruling Bhumihar family occupying a vague position somewhere between that of large landlord and the ruler of a princely state.[18] While the government officially maintained the distinction in status between Banaras and the other "native princes" ruling elsewhere in the subcontinent (these enjoyed legal status under the doctrine of "internal" or "limited sovereignty"), India Office administrators debated in the 1870s whether or not the characterization of Banaras as a "mere zamindary" was grossly misleading ("A History," 1873). Earlier studies have suggested that nineteenth-century direct rule by the British represented a collapsing of the levels of political authority from three to two; that the British came to represent both the national and the regional level of authority.[19]

[17] His successor (Udit Narayan Singh, 1795–1835) unsuccessfully attempted to have the agreement set aside (Nevill 1909a:116).

[18] For a delineation of the rights accorded to the Raja, and how they exceeded those available to ordinary large landholders, see documents submitted by the provincial government to the Government of India, beginning in 1905. IOL & R L/PS/10, vol. 173 for 1910, file 876; Winter to Dane, pp. 6–7.

[19] Cohn 1960:430. Cohn's analysis reflects scholarly preoccupation at that time with the need to analyze the political impact of the British on their empire. The new interpretation of the political history of the Banaras region sketched here reflects a shift of focus from overtly political arenas to those expressed by cultural activities. This shift enables us to make different measurements about the extent of power and influence exercised by the dynasty within the political economy of the area. As a result, we argue that the Raja maintained an important politicocultural influence that kept alive the intermediate "regional" function within local society. See also chapter 7.

But in 1910–11 the British government took the unusual action of creating a new princely state of Banaras,[20] investing the Maharaja with "full ruling powers" over the area encompassed within his zamindari.[21] While retaining direct British rule in the city of Banaras, the British nevertheless recognized the Maharaja's cultural influence there by allowing him to retain his capital at Ramnagar (situated directly across the Ganges River, and the only other town of any size in the district). This decision to re-create the princely state was informed in part by early-twentieth-century British political concerns.[22] The move also, however, officially recognized the ongoing politicocultural influence possessed by that triad of collaborators—the Bhumihar dynasty, the Gosains, and the merchant-bankers. In turn, it also perpetuated this influence: in its unofficial and then official role as princely state, Banaras provided important patronage for Indian artists and intellectuals, as well as opportunities for talented Indian administrators. The Maharaja's council, for instance, reflected the confluence of mercantile, landowning, caste, and educational elite possessing what we refer to here as "Hindu merchant-style" culture (see below). Together the triad shaped this culture so successfully that it integrated those who resided in the city in a way that came to be virtually unparalleled in urban north India.[23]

The preeminent ceremonial expression of this integration—we might even say the cultural expression of the city's political economy—was the Ramnagar Ramlila[*] .[24] This observance, performed under the aegis of the Bhumihar dynasty, is discussed from several different viewpoints in the essays that follow; here we will look at the symbolic expression of civic identity it embodied as it came to be elaborated over

[20] See L/PS/10/173 file 876 for references to other unsuccessful attempts in the late nineteenth century to re-create princely states from areas acquired and ruled directly by the British.

[21] He was to receive a 15-gun salute, and could be received and visited by the Viceroy. (List of Leading Officials, Nobles and Personages 1925:1.)

[22] Administrators, particularly those at the center, perceived the princes as an important political counterweight to emerging nationalist agitators. To support the case that the Maharaja should be deemed a Native Chief, the Government of India remarked to the Secretary of State for India that "responsible as we are for the maintenance of peace and the checking of the seditious movement in India, which now causes us such grave anxiety," [we are] "deeply impressed" with the Maharaja's ability to keep "conservative Hinduism at Banaras on our side." L/PS/10/173 file 876, p. 2.

[23] Delhi represented a similar phenomenon, but one perhaps much more dependent on the strength of the Mughal political power (see Frykenburg 1986). Lucknow presented a regionally focused phenomenon closer to Banaras, but, ultimately, shorter-lived (cf. Oldenburg 1984).

[24] See also Hess 1986 and chapter 1 in this volume, relating to this subject, as well as N. Kumar 1984, and Schechner and Hess 1977.

two centuries. Cosponsored by the Maharaja and the Hindu merchant "corporation" of the city, this staging of the Ramlila[*] stands out for its length and performance elaboration even among the large number of Ramlila observances staged annually in Banaras and its environs (see Mathur 1978, 1979 for brief histories and descriptions of the wide range of Ramlilas[*] staged in the various muhalla s[*] of Banaras). For our purposes, it possesses several key attributes, most notably its expression of the "relationship between government, Maharaja and ordinary people" (Schechner and Hess 1977:54). This is symbolized particularly by the Maharaja's mythical roles as king and as representative of Siva ("the lord of ancient holy Kashi"):

The identification is so complete that everywhere the Maharaja goes he is hailed with the name "Mahadev," a name for Siva. And while the Maharaja is cheered as a god in the Ramlila, Rama is cheered as a king. . . . Usually the Maharaja on his elephant forms one of the spatial limits of a scene, with Rama forming the other. Both Maharaja and Rama are elevated, and the audience is on ground level, assembled between them" (Schechner and Hess 1977:69, 74).

Indeed, as the story unfolds over the thirty-one days, "the boundaries between Rama's world and the Maharaja's world" dissolve. This is facilitated by the extensive patronage provided by the Maharaja's family. Support for Ramlila by the Bhumihar dynasty has always represented a substantial investment, although the burden of support has been shared with the merchant community. Even today—when the state of Uttar Pradesh underwrites about a third of the cost—the authors estimate that the year-round related expenditures total more than Rs. 350,000 (Schechner and Hess 1977:66, 73). Why did the Maharaja's family invest so substantially in this event? One response has been that it was done to "restore the lost glory to the Hindus." The Maharaja himself recognizes the importance of his family's patronage: "My ancestor who started the dynasty also began a renaissance of Hinduism," he notes.

While the emphasis on Hindu values and legitimizing myth have played an important role in fostering the Ramlila (see chapter 1), the emphasis on the Maharaja as kingly expression of the entire community moves this beyond a Hindu framework. Given the close interrelationship of upper and lower (frequently Muslim) classes in Banaras,[25] this vehicle of high Hindu culture was rendered palatable, even essential, through the predominant role played by the local ruler, with whom all Banarsis could identify, through whom all communities became symbolically integrated. This cause was doubtless helped by that

[25] See N. Kumar 1984.

strain in Tulsidas which emphasized social equality among those devoted to god (Hess 1987).

Given the communities involved, this was a particularly significant accomplishment. The ordinary denizens responsible for the main "industries" or production activities operating in Banaras included artisans, religious specialists, and scholars. Most of the literature on Banaras emphasizes the latter two,[26] but artisans were the most numerous group; their wares included, particularly, silk products, brass ware, and wooden toys. Of these various producers, we may judge the weavers, virtually all Muslim, to be the most important, in part for their numbers (more than a quarter of the city's population), and in part for the collective role they have played in the life of the city (see N. Kumar 1984 and chapter 5 in this volume).

We may also use the weavers to illustrate social and cultural integration in Banaras. On the one hand, since the weavers were independent artisans, their production schedule was their own—a form of "freedom" they prized highly. On the other hand, both for their supplies of yarn and for marketing their goods, they depended heavily on Hindu merchant middlemen or agents. From the early nineteenth century on, observers have pointed to this close relationship when explaining why the weavers of Banaras are not more confrontational in behavior. (Indeed, their collective behavior differs dramatically from that presented by Julahas[*] , or Ansaris, as they wished to be called, in other urban sites of north India [see G. Pandey 1983b for an inventory of historical references to "bigoted Julahas" rioting or protesting to protect their perceived rights].) In 1931 an observer could still write:

It should be explained that in Benares the Mahomedan population is nearly entirely dependent upon the Hindus. With the exception of a few members of the old Mahomedan aristocracy, who are now in straitened circumstances, the entire community lives a hand to mouth existence. . . . The weavers are without exception dependent on the good will of their Hindu employers. The two communities are therefore closely bound to each other by economic ties.[27]

Beyond this indicator of economic interdependence, we also have evidence to suggest that Muslim weavers actively participated in the public ceremonials expressing a shared Banarsi civic culture, including "the marriage of the Laut" (Bhairava), Bharat Milap[*] , and the day-to-day observances related to particular figures and shrines (see chapter 7

[26] See Eck on scholars and priestly groups. Jonathan Parry's work on the death specialists of Banaras adds another entire dimension to the literature; see, for instance, Parry 1980, 1981, 1982.

[27] IOL & R. L/P & J/7/vol. 75 for 1931, p. 573.

for more details). Moreover, even Muharram fit into this larger pattern. An observance during the first ten days of that month, this event commemorated the martyrdom of the Prophet's grandson, Husain, massacred in a battle over the appropriate line of succession. This memorial functioned in early-nineteenth-century Banaras as a ceremonial expression, of "Islam" in which many members of the city participated, nevertheless. Some 90 percent of the Muslim participants were Sunni not Shi'i (the group for whom the event had historical importance), and very substantial numbers were Hindu.[28] Like the style of observance in other areas where the crowd preponderantly featured non-Shi'i participants, the ceremonial emphasis in the Banarsi Muharram focused on its processional elements, while popular participation encompassed a range of behaviors that permitted participation by Hindus and Muslims, disinterested in the original martyr motif, to join in fully. In all these characteristics they closely resembled other, ostensibly "Hindu" observances of the city's shared ceremonial life.

Thus the style of Muharram observance carried the implication that the Muslims in Banaras pursued, through ceremonials, simultaneous goals of reiterating their Islamic identity and reinforcing their ties with other Banarsis, particularly those power holders interested in the reinvented Hindu culture that came to characterize Banaras. This fits with other evidence now emerging, particularly from Nita Kumar's fascinating examination of schooling among the Banaras Muslims. In a recent presentation she pointed to the history of the Jnana Vapi Mosque perpetuated among Muslim students by such texts as a geography prepared by Abdus Salam Nomani (1963). Denying attribution of the mosque to Aurangzeb, the text maintained: "This is wrong. The foundations of this mosque were laid by the great grandfather of Badshah Alamgir, Akbar, and Alamgir's father, Shahjahan, had started a madras in the mosque in 1048 hijri."[29] That is, in legitimizing their claims to space—and, implicitly, to a presence and role in the city— Banaras's Muslims turned particularly to rulers known simultaneously for establishing Muslim rule and for developing a distinctly integrative, syncretic Indo-Muslim culture.[30]

[28] As late as 1895, the local vernacular press could comment, "Mohurram passed off without disturbance. . . . when it is Hindus who mostly celebrate this festival, what fear can there be?" Bharat Jiwan , 8 July 1895, p. 1, quoted in N. Kumar 1985:316.

[29] Quoted in N. Kumar, "History and Geography as Protest: The Maintenance of 'Muslim' Identity in 'Hindu' Banaras, c. 1880–1987," p. 33. Paper presented to the panel on Protest and Resistance, American Historical Association, December 1987.

[30] N. Kumar has called attention in chapter 5 in this volume to her differing interpretation of these relationships. She argues that not enough credence is given here to the Muslim and lower-class point of view. I suggest, instead, that this viewpoint cannot be fully understood unless it is viewed from a comparative perspective that places this view-point next to that expressed in other, nearby cities. Her argument that the popular culture activities in Banaras express a shared set of lower-class values that she designates "Banarsipan" cannot be convincing without references that make clear what distinguishes lower-class culture in Banaras from that expressed in other north Indian urban sites. Nothing noted in her essay or earlier work suggests that such a distinction exists. Instead, what distinguishes Banaras from other central places is the nuances of the nexus of cultural expressions and social power, as elaborated in this volume.

To this cultural claim, moreover, the Muslims of Banaras added that of power in numbers. That Muslims were a coherently organized group capable of bringing pressure to bear on the municipal government, and that, therefore, their civic integration was prized as much by municipal power-holders as by weavers, is indicated in the 1909 gazetteer's reference to the impact of the famine of 1897. While Banaras district "fared moderately well" in this famine, "the city population, however, suffered considerably, as must inevitably happen when prices rise to famine level and when trade is dull." Money raised locally and contributed by the municipality was distributed in three ways: in the form of doles to "respectable poor"; as "gifts of clothing to paupers" (which created a demand for cloth); and as "advances to the weavers for making cloth, which was afterwards purchased for distribution in the city and elsewhere." That this reflected the priority placed on placating the weavers is clear, for "the weavers were among the first to feel the pinch of scarcity, and on the 15th of September 1896 they made an organized demonstration, complaining against municipal taxation and the octroi duty [presumably that levied on imported yarn]: they were informed that their demands could not be complied with, but that relief would be afforded them should the necessity arise" (Nevill 1909a:48–49).

Evidence suggests that other artisan and low-caste service groups proved similarly important in the political economy of the city—particularly butchers and Ahirs (or Yadavs[*] , as they prefer to be called). This should not surprise us for, as Bayly notes,

both Hindu and Muslim writers imply that the provision of services by a large client population is a guarantee of an appropriate religious [and civic] existence. Thus the city (nagar ) for some Hindu theorists was where the system of castes reaches its most perfect expression and the greatest number of ritual specialists and jajmans are on hand for the protection of dharma . Similarly, for Muslims the city is the "flower of earthly existence" because this is where the faithful can find the basis of social life—the mosque, running water for purity, learned qazis to settle disputes, and the Sultan to protect the umma [community of believers]. (Bayly 1986:223)

The essays in this volume provide additional insights on the central role played by service and artisan groups. To understand the civic roles

played by these groups, we must understand the nature of an urban site in nineteenth-century north India.

Banaras as Urban Context

As a municipal-level site for much early experimentation in self-government, the city of Banaras provided many outlets for the civic interests of its merchants and other intellectual and economic elite of the area. References in the gazetteer to merchant-bankers as municipal commissioners and honorary magistrates suggest some of the avenues pursued by this elite. These positions provided more than symbols of power, for local government had access to increasingly significant resources over the nineteenth and into the twentieth century. For instance, new forms of taxation were sought almost immediately by the British to cover the costs of administering the city once they had taken direct control. A local tax to support neighborhood police (chaukidari[*] ) was introduced at least by 1795; perhaps because this phatakbandi was levied by the neighborhoods themselves, who also appointed and paid the chaukidar s, residents voiced few objections. In 1810, however, the British attempted to introduce a form of house tax; the protest in Banaras proved so vehement that the administration had to retreat to the phatakbandi (see chapter 7 for a further discussion of what this protest revealed about power relationships in the city); this arrangement remained in effect until 1867, when the provisions of the Municipalities Act of 1850 were applied to the city.

Under the Act a new municipal committee collected revenues for a police force, conservancy, and other "general improvements." Ultimately the octroi tax on imports became the "backbone" of municipal income (B. N. Singh 1941:79), providing more than half the revenues; other revenue derived from taxing pilgrims, as well as from assessments for water, light, and (eventually) houses; these were supplemented by income from rents and licenses. Initially, the District Magistrate functioned as the president of the committee. The municipal board became increasingly representative after 1884, however, and by 1904 it consisted of twenty-eight members, twenty-one of whom were elected. Interest continued high in civic participation; in contrast to the district committee governing the rural areas, Nevill noted that "the elected members [of the municipal committee] exhibit great interest in the work, and the attendance at meetings reaches a high average" (1909a:168). Indeed, in 1941 a local scholar could comment that "with the exception of political events [i.e., nationalist agitation], the general public is more interested in Municipal administration" than in any other topic (B. N. Singh 1941:95).

The ostensibly familiar veneer of these modern-style interactions should not mislead us, however, for it covers a process in which the idiom was much more indigenous. It was a process that had begun much earlier. "The early colonial period," Bayly tells us, "saw the further consolidation of a merchant and service class between the state and agrarian society. It was as much the product of the slow commercialisation of political power which had gathered pace in the late Mughal period as of the export of trades and land market of colonial rule. . . . But as an indication of the persistence of an indigenous social change [begun in the eighteenth century], it was no less important because its idiom remained 'traditional' " (1983:344–45).

This idiom proved particularly strong in Banaras. We may explain this best by briefly examining the place of Banaras in the "indigenous social change" to which Bayly refers. Begun in the eighteenth century, this was rooted in the development of urban places in north India. That is, at the same time that certain urban centers emerged during the late eighteenth century, a new set of intermediary groups emerged within them: these have been designated by Bayly as "corporations." We will examine the implications of the rise of this form of collective decision-making at the local urban level in more detail below.

The word "town," Bayly notes, can be applied to a number of different levels in the hierarchy of central places in India. The lowest level was hath , or "humble periodic market, which had no urban features at all." Above this was the ganj , the small, fixed-market centers founded "by the agents of regional political authority, and the fortress lineage-center of the local zamindar or petty ruler. . . . A congregation of fixed markets sometimes became, in effect, a small town. But the most obvious bottom rung of the urban hierarchy proper was the country town or qasbah which generally supported a population of more than 3,000" and possessed distinguishing characteristics in terms of social, legal, and economic status (Bayly 1983:110–12). As R. Kumar has noted, such a center was "urban in the sense that its residents, by and large, were not directly engaged in agricultural production. . . . Besides the revenue officers and the men of commerce, the qasbah was also the seat of the petty landlords of the locality, just as it was the base of artisans and craftsmen who produced goods for a wider market" (R. Kumar 1978–79:202).

Finally, with a population of over 10,000, were the cities proper, of which there were more than sixty serving many different functions in 1770.[31] Of the very largest centers in the province, the three great cities

[31] "These functions ranged from retail centers and bulking points, through transit points for longer-distance high value trades, to service centers for regional rulers or their 'great lieutenants' " (Bayly 1983:110–12).

under the Mughals—Delhi, Agra, and Lahore—had lost their primacy as well as much of their population (from 400,000 in 1700 each had declined to 100,000 a century later). By 1800, however, cities like Banaras and Lucknow—as centers of regional successor states—had acquired a comparable dominance in their own regions, with populations of about 200,000 each. Though the number of cities in the next lower level, that is, those holding populations of 10,000–100,000 did not change greatly in this century, there was much movement of population among them, prompted particularly by Jat and Rohilla conquests in the west of the province and by consolidation of the commercial economy in the east. Even among "cities proper," then, there were a number of sites whose size of population shifted in the eighteenth century in response to economic and political stimuli.

Consistent behind this movement of peoples, however, stood commonly held notions of urban organization, including, particularly (1) neighborhood social organization; (2) policing and peace-keeping functions and the dispensation of justice; and (3) an "intermediary" role developed and filled by "corporations" of leading citizens. Each of these will be discussed in turn.

Not enough work has been done on the muhalla[*] (neighborhood) as the basic unit of urban social organization and what we may call associational activity. The key to understanding this may be the work of Stephen Blake, which traces an eighteenth-century shift in the organization of residential space in Shahjahan's capital city. The pattern, begun as an outgrowth of the emperor's camp organization, featured neighborhoods centered on the haweli[*] (great house, palace), in which service and other client groups lived in domestic configurations clustered around their patrons (courtiers or large merchants). But in the eighteenth century, as the Mughal Empire declined, this pattern shifted to one in which residence units, instead, clustered caste or craft groups together in specific muhalla s[*] (Blake 1974). The shift, though substantial, may never have been complete: evidence can still be found throughout the nineteenth century of the haweli -centered pattern (see Bayly 1978). How the muhalla served as an organizational base for local community identity and activities is examined in more detail in Part 2. Here it will suffice to note that the shifting pattern of neighborhood may also have reflected social (and power) shifts that emerged over the nineteenth century. That is, from the patron-client structures of the inner city, city power bases may have moved outward, thus accommodating the caste- and occupation-specific muhalla s located at the outer edge of the city (and see chapter 7).

The role played, respectively, by the qadi and kotwal in policing urban centers and dispensing justice provided another central character-

istic of the north Indian city. Indeed, the essential element in defining an urban space in the Muslim cities of the plains had been the presence of the qadi, or Islamic judicial official. "As a 'censor of morals,' the kazi was to enforce public righteousness when public opinion, embodied in periodic religious and caste assemblies, had proved unable to do so." This "strong moral, even religious sanction," applied to the "smooth working of city life," extended to the role of the kotwal as well. He "was supposed to work through the faithful and public-spirited citizens, 'engaging them in pledges of reciprocal assistance and binding them to a common participation of weal and woe'." Chapter 7 suggests what happened when this "framework of institutions and moral ideas" began to decay within "at the same time as their functions were reduced by the power of corporations or landed gentry" (Bayly 1983:308–11). That is, qadi and kotwal were affected by a process begun in the eighteenth century under indigenous pressures. Although qadi and kotwal were left in place, the impetus of moral action shifted to the triad: merchant-bankers, mendicants (Gosains), and the new ruling dynasty. It remained in the nineteenth century for the British empire to co-opt the kotwal completely and, ultimately, to abolish the position of qadi in about 1865.[32]

Perhaps most important for our purposes was the emergence, in this period of shifting urbanism, of "corporations" of Hindu merchants or Muslim learned men to provide a new organizational focus for urban life. The contributor of this concept, Bayly, defines "corporation" to mean "an occupational or religious organization which transcended the bounds of 'caste' in the sense of jati. It would therefore include commercial or priestly associations . . . as well as certain types of ascetic [groups] . . . which integrated urban or rural society and acted as self-regulating entities de facto. . . . [Thus] Indian society produce[d] dynamic, multi-caste institutions in the context of growing monetisation and the weakening of central state power" (1983:163n.).

It is to these corporations that we must look for the most significant change wrought in the eighteenth century, the development of "more stable patterns of local power [that] were slowly being precipitated between the state and agrarian society. There emerged a unified merchant class wielding covert political power, and a locally resident gentry [Muslim or scribal Hindu] of literate service families." It is these two groups—(predominantly Hindu) merchants and (predominantly Muslim) landlords with courtly connections—who, performing intermediary roles, developed attendant cultural patronage styles during the

[32] See, for example, documents on abolition in NWP Judicial A Proceedings no. 48–108 for 19 January 1865.

Map 3

U.P. Districts about 1860. Stippled area indicates Bhojpuri region. Areas in parentheses

are princely states.

eighteenth century. Elaboration of urban corporations as cultural and economic intermediaries had a profound impact over much of north India.[33] The personnel of these corporations had been recruited not from the old commercial families, for these were definitely in decline along with the Mughals, but from "communities with their feet firmly in the villages and small towns who made the adaptation with least pain . . . and often, local groups from outside the bounds of the traditional merchant communities" (Bayly 1983:161–62). Implications of this pat-

[33] It also established precedents of appropriate behavior which would prove very important for institutions of self-governance in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

tern were as important for city-hinterland connections as they were for urban residents themselves (see Part 3).

The emergence of such urban corporations is important for us in this study of the urban site of Banaras, for

corporations of townsmen, merchants and religious specialists had developed a new coherence and autonomy which in some cases amounted to a virtual civic self-government. These changes were not frustrated by caste fragmentation or the passivity of Hinduism: on the contrary, caste and religion provided the building-blocks out of which mercantile and urban solidarities were perceptibly emerging. . . . [Although the growing European presence in India doubtless enhanced this process,] the commercialisation of politics and the rise of the corporations were by origin intrinsic changes within the economy and culture. War and political change, far from destroying towns and trade, had actually galvanized them into greater independence. (Bayly 1983:175)

Two major forms of such corporations had evolved by the end of the eighteenth century, shaping cultural expressions particular to each; the style of an urban site depended on whichever was dominant in that central place. The first emerged from the qasba s[*] (or country towns) founded by Mughal service gentry; the Indo-Persian style that characterized this form emphasized "continuous connection with the rulers, dependence on service income," and Urdu literacy. It was expressed in what we may call the dominant economic "institution," the qasba[*] landowner. The second emerged from the ganj s (small market centers), fostered by "a group of entrepreneurial castes with common professional practices who were also linked together through a system of hierarchically organized markets"; it was expressed through the economic institution of the Hindu family firm (Bayly 1983:370).

Each type of corporation fostered a particular cultural style. Interaction between these Indo-Persian and Hindu merchant cultural styles provides much of the background for developments in colonial Indian history. Largely as a result of the impact of the hold of the Mughal Empire after its decline, as well as the influence of Muslim successor states,

Indo-Persian cultural activities and values figured largely in urban and colonial political events in the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth century. But the history of late colonial India becomes increasingly dominated by the values and interests of the Hindu merchant elite; as this culture came to the historical forefront the influence of the smaller towns of north, India in which it was rooted increased (Bayly 1983; Freitag 1989).

The culture emerging from Hindu merchant patronage had a number of identifying characteristics. For our purposes, the most important were Sanskritizing in nature, and included patronage of religious personnel, buildings (especially the construction, maintenance, and elaboration of temples), and ceremonials. Also important were reformist activities that frequently exhorted the lower castes to adopt Sanskritizing values and modes of behavior; perhaps most significant, these often became linked to political movements.

What the increasing dominance of Hindu merchant culture meant for the largest urban centers emerging in U.P. in the nineteenth century is especially interesting. Of the five major urban centers in U.P. (see table 1, showing population figures for 1911 and 1941)—Lucknow, Banaras, Allahabad (which became the provincial capital of U.P. under the British), Agra (an old Mughal capital), and Kanpur (a British-created inland industrial center)—four found it necessary to balance the traditions fostered by these two differing styles of corporate organization, for their populations reflected residents accustomed to each. Only Banaras lacked the strong presence of an Indo-Persian literary elite. That lack, coupled with the strength of the collaboration that had emerged among Maharaja, merchants, and Gosains, gave Banaras a very different urban style. It is aspects of that politicocultural style which we examine in the chapters that follow.