"Doing Ngoma": The Core Ritual Unit

The song-dance of ngoma may last all night, as in the Kongo example at the head of the chapter. Such a session is made up of many shorter units of song: the self-presented and the response. In the Cape Town setting, which will be featured here, it may be repeated by the same person (usually with a different song), or someone else "takes up ngoma" and "does his or her ngoma"—sa ngoma . The sequence of such units may go on for hours. It may occur within the context of events heralded as purification celebrations for established healers or as celebrative points in the initiatory course of novices. The familiar group ngoma song presentations may be seen at a wide variety of events within the local ngoma network. An important variant of the sufferer-singer presenting his or her invocation and song is for another singer to present the "case" of the sufferer. This may occur in the instance of a very sick individual, someone who has not developed her or his song or who cannot perform, or a senior healer who has suffered the death of a close kinsman and is being ministered to.

The case that will be illustrated is from a "washing of the beads" of a senior igqira/sangoma in the Western Cape following the period of

mourning of the death of her mother. Her sister and host of the event sang the leads, reiterating the death of their mother. The spoken openings to each unit narrated the days leading up to the death, details surrounding the death. It was thus in effect a requiem ngoma and a coming out of mourning of the descendant. Death is impure, but mourning and commemoration allow the ngoma practitioners to cleanse themselves and to "throw out the darkness" and to "wash the beads" with medicines—in Nguni pollution terminology, to replace darkness with light.

At the site of throwing out the darkness, outside, the same format is again repeated. For the spoken prayer parts, the novices (amakwetha) sit down for the declaration, then rise for the dancing and singing (fig. 9).

In the following pages I present a sequence of self-presentations (ukunqula ) and song-dances (ngoma) performed at the above event, first among senior sangoma and amagqira of the Western Cape, followed by a session by their novices.[1]

1. Ukunqula [by the senior healer whose mother had died, and who was being cleansed]: Sukube ndilthandenza ke xa kdisitsho kumama . In so saying I'm praying to mother. We'll leave having washed each other [repeated many times]. Kuphilwa ngamutu . We survive [or live] because of each other. While we say we came to "heal" here.

Ngoma: Bambulele umama ... They killed mama.

2. Ukunqula : You would have thought that the night "war" would have calmed down this [igqira spirituality]. But no, it doesn't. I'm in it, always facing a white person [at work], and maybe that's why I'm "on edge."

Ngoma: Balele phezu kweentaba zuLundi . The [ancestors] are sleeping at the top of the mountains of Ulundi.

3. Ukunqula : Let's camagusha now! Let darkness be replaced by light. Nizala [a relative], I want you to say for me to these amagqira and these visitors what we're here for, they're welcome.

Ngoma [in Afrikaans]: Wat makeer vandag, wat makeer? What's happening today?

Figure 9.

Plan of house, compound, and street in Cape Town township setting

where "doing ngoma" was performed, in the context of "washing of the

beads" of senior healer Adelheid Ndika following her mother's death:

(a) living room and intermediate ritual space where all ngoma sessions are

held, as well as "calling down ancestors"; (b) kitchen; (c) bedroom;

(d) storage room; (e) backyard; (f) subrenter shelter; (g) water tap, toilet;

(h) profane public space where "coming out" is held and where darkness

of pollution is "thrown away."

4. Ukunqula: Hulle wil meet wat makeer vandag? Kaffirdans. You want to know what's happening here today? It's a Kaffir dance! Let darkness be replaced by light.

Ngoma: Ndiyamthenda u Jesu; waklulula umoy a wam . I love Jesus, he set free my soul.

5. Ukunqula : Let darkness be replaced by light. Camagusha . I thank being welcome in this home, camagu . I was coronated in this home, and the isidlokolo bushy hat was given to me here.

1.

Young women and mothers of the lineage in procession, during Nkita rite in

Kongo-Ntandu society, western Zaire. Photo archive, Institut des Musées Nationaux

du Zaire.

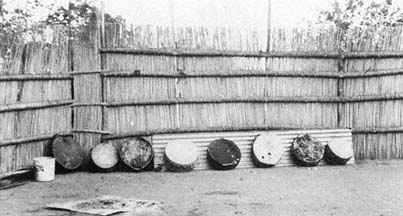

2.

Diversity of ngoma drums

from the Congo Basin, Zaire:

(a)

with face of Mbuolo healing

spirit, Yaka, Southwestern

Zaire, Institut des Musees

National duZaire (IMNZ)

71.138.1 (59 cm. tall, 28 cm. wide);

(e)

RMCA 8977, Kusu, Maniema, 65 x 36

cm., before 1902 (Boone VI/2 "ngoma");

(f)

RMCA 48.20.107, Hungana,

Southwestern Zaire, 98 x 33 cm.,

before 1948 (Boone XIII/10);

(b)

Tshokwe-Lunda, Kasai,

IMNZ 71.22.13 (53 cm. tall);

from the collections of the

Royal Museum of Central

Africa, Tervuren (RMCA)

and published in Olga Boone,

Les tambours du Congo belge

et du Ruanda-Urundi, 1951;

(c)

RMCA 38828, Luluwa, Kasai,

52 x 35cm., collected 1939

(Boone plate VIII/34, "ngoma");

(d)

RMCA 31696, Tabwa,

Southeast Zaire, 28 x 27 cm.,

prior to 1882–1885

(Boone VI/12, "ngoma");

(g)

RMCA 27729, Lele, Kasai,

98 x 28 cm., before 1924

(Boone XXXVIII/5);

(h)

RMCA 37955, Hutu, Rutshuru, Kivu, 83 x 41 cm.

(Boone XXVII/7, "ingoma" or "impuruzu"), the

thong-tied drum beaten with stick shown here,

typical of northern forest and West African

region, but with form and name of "ngoma" area.

The faced drums articulate visually the idea of

the spirit-rhythm in ngoma. Photographs c—h

courtesy Section of Ethnography, Royal Museum

of Central Africa, 3080 TERVUREN, Belgium.

3.

Kishi Nzembela, of Kinshasa, Zaire, before painting of her late daughter

Janet, for whom she is a medium in Bilumbu, a ritual of Luba origin. Photo

by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

4.

Kishi Nzembela, a Catholic, stands before this painting of Jesus in her healing

chapel in her home compound in Kinshasa. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

5.

Pregnant woman "in seclusion" as part of reproduction enhancing ngoma

among the Chokwe of Zaire, Southern Savanna. This is comparable to ngoma

Mpombo in the South Kasai. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1959.

6.

At Betani, the diviners' college, eight tigomene drums of cowhide over seg-

ments of oil drums lie in the sun to tighten the hide for the next performance.

They will be used in mediumistic takoza divination ceremonies to reveal the

causes of distress for clients. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

7.

Tanzanian mganga Botoli Laie of Dar es Salaam demonstrates and displays paraphernalia for ngoma Mbungi:

five ngoma drums, two wooden double gongs, and medicine basket. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1983.

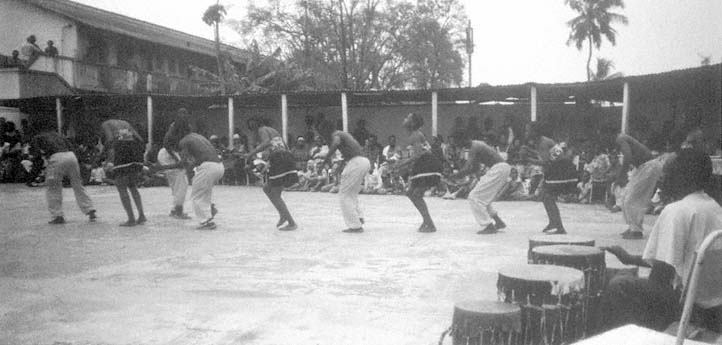

8.

An example of ngoma as secularized entertainment, performed by the Baraguma ngoma troupe of Bagamoyo, here doing the Sindimba dance

at the Almana nightclub in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Instruments include ngoma, other drums, and xylophone. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1983.

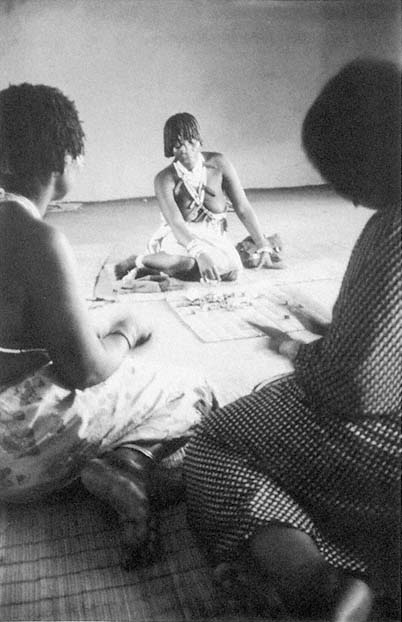

9.

enior novice in Ida Mabuza's college in Betani, Swaziland, performs pengula

bone-throwing divination, widespread in Southern Africa, before a client (right)

and a colleague (left) who indicates agreement or disagreement with each

declaration by the diviner. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

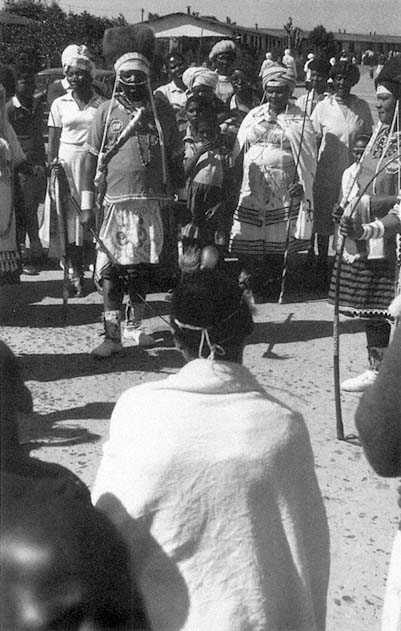

10.

A group of novices (amakwetha ) in white performing an ngoma on the street in Guguleto township, South Africa,

at the time of a "washing of the beads" purification for igqira Adelheid Ndika. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

11.

Cowhide over oil drum is here used in an ngoma session in Guguleto, Cape Town,

South Africa. It is drummed by a novice (nkwetha) who has her head bound with

two strands of white beads to indicate that she is "in the white." She is accompanied

by a hand-clapping noninitiate. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

12.

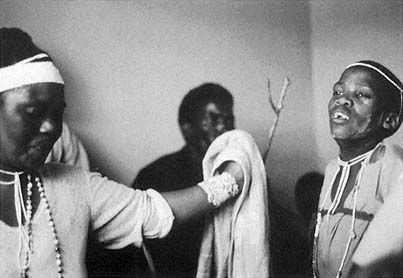

Two novices (amakwetha) participate in ngoma session in Guguleto, Cape Town.

They are part of a close circle of novices who are "presenting themselves" in

call-and-response performance. The script of this event is given in chapter 5.

Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

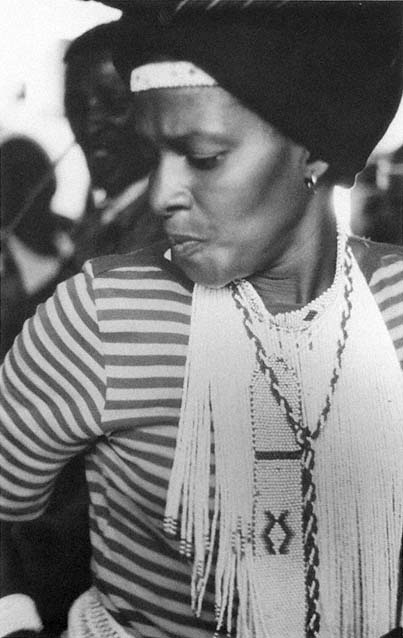

13.

Ngoma session presented in chapter 5 was led by this woman, a just-graduated

igqira (healer) whose manner of leading the others out, of dancing, and of

bringing the participants together was as striking as is her composure in the

picture. The beadwork is the beginning of her igqira costume, which began

with a few strands of white beads when she was a novice and will flower into

a colorful full costume. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

14.

A "white" novice serenely watches others in

ngoma performance after having presented

herself to others in evocation, prayer, song,

and dance. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

15. Preparing to "throw out the darkness,"

the pollution of death of a novice's kinsman.

Igqira Golden Majola distributes tobacco to

his novices, which they will throw into the

waters of the Indian Ocean near Cape Town

to the accompaniment of a singing and drumming

ngoma. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

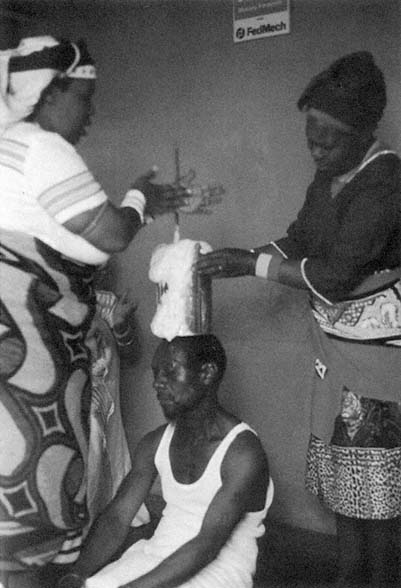

16. Amagqira Adelheid Ndika (left) and helper (right) stir the ubulau medicine of entry

into "the white" at the outset of the sufferer's novitiate. Photo by, J. M. Janzen, 1982.

17. Later, after the goat sacrifice and the all-night ngoma, the opening

phase of ngoma initiation is concluded with ngoma sessions on the street of

Guguleto, a black township near Cape Town. The "white" novice is seated

in the foreground while fully qualified amagqira take turns encouraging him

with song-dance ngoma. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

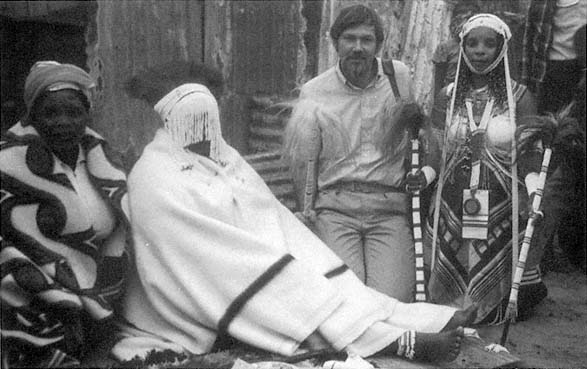

18.

The author kneeling between the graduating still-veiled novice and her kinswoman (left) and her igqira healer (right),

in Guguleto township. Photo by Reinhild Janzen, 1982.

Ngoma : I love Jesus, he set free my soul.

6. Ukunqula : Mzala, I thank what you've done, saying sorry after "sinning," consulting those above you.

Ngoma : I love Jesus, he set free my soul.

7. Ukunqula : We came to uncover the wound, and thereafter take some oil and anoint it. I, too, came to say: Let the wound be healed. The amagqira have spoken well.

Ngoma : I love Jesus, he set free my soul.

The basic call-and-response structure of the ukunqula/ngoma pattern is enriched by a rhythm between speaking and singing. Afrikaans, English, Xhosa, Zulu, and Swazi evocations and songs in these two sessions are a particularly poignant reminder of the cleavages and cosmopolitan diversity of South African society. Especially touching are the exchanges in Afrikaans (#3, #4) that may have been prompted by my presence with several members of my family. One of the senior igqira in evocation number 3 asks the others to tell "why we're here." That is followed by an ngoma in Afrikaans: "What's happening here?" The next ukunquia (#4) responds that it's a kaffirdans . This demonstrates the power of the medium to absorb the condescending attitude of white South Africa toward an African institution. The exchange is, however, intended to be ironic. Ukunqula number 2 also touches on the role of ngoma in helping these amagqira deal with the racial tension in their society. This woman was a domestic worker in a white home, and she complained to us of her low wages for long, hard working hours despite many years of seniority. She used the ngoma session to tell the others, and her ancestors, that this is what made her "on edge," or spiritually "sharp."

The repetition of the ngoma "I love Jesus ..." from Zionist singing, demonstrates the influence of Christianity, but it also suggests that it is difficult to draw a line separating "African" from "Christian" reference points. However, ngomas 1, 2, and 7 are in a more conventional idiom.

After shaking off the isimnyama , pollution, as a result of the death, and singing-praying for the igqira, the second ngoma session follows for the novices. A just-graduated, fully qualified igqira (the woman in the blue and black striped sweater, plate 13) leads this session. (Plates 10, 11, and 12 portray this event.) She opens with a song-dance.

Ngoma: Simonwoya . We have spirit ...

8. Ukunqula [by a boy novice]: Ka Ngwane [ancestors], hear me.

Ngoma: Mombeleleni, unonkala, ngasemlanieni . Sing and clap for the crab next to the river.

Ngoma: He Majola [clan name], phuma e jele . Majola, come out of jail. Ndinendabe zonzi wakho . I have news of your house. (See fig. 10.)

[One of the persons in the circle points to another who is sick, a novice.] We are giving [the song, ngoma] over to you mother, camagu .

Ngoma : ... eluhambeni . ... in a trip [inaudible].

9. Ukunqula : I ask for protection from my people [ancestors], the Radebes and the Mtinikulus.

Ngoma : [call] Akulalwa ezweni akulalwa ; [response] akulalwa akulalwa ezweni . ...

Ngoma: He Majola phuma entelakweni, ndinendaba zonzi wakho . Majola come out of confinement (lit. "the pot"), I have news of your household. Camagu!

Ngoma : Hey Majola, come out, I have news of your household.

10. Ukunqula : Let darkness be replaced by light. I call on my ancestors. This igqira was handed me by a parent while living. I take after my grandmother, and use one of the eyezeni medicines. I resemble an igqira of igqiras, a truly authentic one. The white bones over which death lies, I approached them with my back turned to them, that they not be resentful of me. May the drug be revealed to me, so that as an igqira I may be able to say the truth after kneeling before my clients.

Ngoma: Khawuhibe igqira . Go, go igqira.

11. Ukunqula : Since I almost left this ceremony without coming forth to say something, I might fall sick after leaving this house. May I sing.

Figure 10.

Spatial layout of "doing ngoma" in living room of home depicted

in figure 9; (a) all participants in living room; (b) circle of amakwetha

(novices); (c) fully qualified igqira (healer) who leads session; actors in the

ritual unit once session has begun: (d) in left-hand scheme, novice presents

ukunqula ; (e) other novice or leader responds to self-presentation, and

leads in song-dance, as shown in right-hand scheme.

Ngoma: Ndine thumba lam lokuthandaza . I have my time to pray.

Ndinendawo yam yokuthandaza . I have my place to pray.

12. Ukunqula: Camagusha! Let us remember what we are here for. To ukublamba , purification. I have very little with me. [Response] Camagu. Let the darkness be replaced by light! [Response] Camagu . I pray for a drug, that it may do its work. May it be there, as far as the caves, the river, from where it comes, and where its roots are ground on a stone to make medicine of it. I am also here to pray to God. May this home of the Makwayis have the darkness replaced by light.

Ngoma: Andimanto esandleni, ndize kanye Nkosi. Sendondele ekrusini, ekubethelweni . I have nothing at hand, I come once Lord ...

13. Ukunqula : When I'm here, presenting myself, I think back to my mother's home, at the KwaNguni, and the way they said, "Let darkness be replaced by light." Ndiyanqula ndiyathendaza, camagwini ? [Response] Camagu . I admit that I take pills when I come to a ceremony [inthlombe ] because it makes me sick. May darkness be replaced by light. My people should not worry that I'm doing

this ukunqul presentation. I'll lead in my song and then hand the ngoma over.

Ngoma: Andiyoyiki le ntwaza na ingangani . I am not afraid of this girl who is as big as myself. [Response] Camagu .

14. Ukunqula : I am hard-pressed by rental fees and many other things. I had to take from my children, asked them to give me some soap, for the young women here to smell good.

Ngoma : Blessed be the name of the Lord [in English].

Ngoma: Yomelelani kunzima emblabeni . Be strong because it's hard here on earth.

15. Ukunqula : I come from afar. My home is in Swaziland, and I'm a visitor. I call on my ancestors.

Ngoma : [call] Unwoya wam ; [response] wankbulul'umoya wam . My spirit, he set my spirit free.

Ngoma: Ndize kuwe, undincede . I am coming to you Lord for help.

Ngoma: Sicel'i camagu . We are requesting a camagu.

16. Ukunqula : I call upon my ancestors to let darkness be replaced by light. I am glad that the darkness that has been hanging over here could be removed, that broken hearts have been consoled. I thank all of God's children present, in the name and authority of Jesus. Hallelujah, might God give us power. May Jesus give the woman Maradebe power. Things are as they are, the wearing of white beads [novices who are initiated], because there is no peace in the world. Hallelujah, beloved ones, may God bless you.

Ngoma: Themba lam ngu Yesu, ndozimele ngeye . My hope is Jesus, I'll hide in him.

17. Ukunqula : I wish to be a sincere, honest igqira. If I can't diagnose something, I'll kneel down and pray in order to tell the truth. I want to stand atop of Table Mountain and be light to the people. May the darkness be replaced by light!

The spoken calls (ukunqula ) and sung responses (ngoma), with drum and dance accompaniment, demonstrate the complex basis of this institution. There is a keen desire on the part of these novices (amak-

wetha) to be in touch with each other, as they put it, to camagusha . The phrases "let's camagusha " or the call "camagu! " followed by the response camagusha indicates before each ngoma unit a kind of ritual positioning to follow through. This call announces, in effect, "let's do an exchange," or "we have heard," "we have agreed." These verbal signals are important as rhetorical framing devices in the ngoma work at hand.

There is also evidence of deliberately handing the ngoma around, as it were, "being it." In set number 8 someone, it is not clear who, hands the song over to another woman.

The content of the individual declarations and songs varies widely, the former for the most part relating to the lives of particular individuals, their call, sickness experience, environment, their aspirations, whereas the latter, the songs, are more culturally standardized. A number of ukunqula evocations call on ancestors for help and solace. We see from the names mentioned that this is a varied group of novices from across Southern Africa. Clan names such as Ka Ngwane from the Eastern Transvaal (#8), Radebe and Mtinikulu (#9), the generic KwaNguni (#13) are mentioned. One says she is from Swaziland. The ancestors are invoked in a general sense here, which differs from identification with particular ancestors in other regions of Central and Southern Africa (e.g., Fry among the Zezuru, or Turner among the Ndembu). There is also indirect and direct reference to natural domains of land and water and to mediators across these domains. The young boy (#8), following his ukunqula , sings out the "crab song" and others join in. This is a commonly heard ngoma both in Southern Africa and elsewhere (the term nkala for crab is very widespread, as is the reference to the crab as a mediator). The crab burrows in the beach sand and scurries into the water when discovered. It is the perfect natural reference for a spiritual metaphor bridging land, the domain of humans, with water, the domain of ancestors and spirits. Similarly, there is reference to plants and drugs (e.g., #12) found in caves and along rivers, mediatory zones, that are used to enhance the ngoma process of "coming out" and "sharing" and "presenting" oneself.

Most of the novices express a concern for articulating their inner conflicts, getting their words out. Songs in numbers 8 and 9 mention a Majola who is implored to "come out of his confinement"—literally a pot—because they have news to share with him. This image of a person being in a jail, or a prison, or a "pot," is an intriguing one for the person who is trying to clarify his situation. Another image common in this

occasion was that of "replacing darkness with light," being able to "see" clearly.

Some of the ukunqula self-presentations have to do with personal problems. In number 10 the novice talks of her call from her grandmother and asks that she be able to follow in her steps as an igqira. In number 11, the novice feels compelled to share so that she won't become sick. The novice in number 12 prays for a medicine that will help her clarify her situation. Novice number 13 admits that she takes medicine prior to the sessions because they make her sick. In number 14, the singer confesses that she is so poor that she took from her children to be able to bring something to the sharing session. Another, in number 16, laments that there are so many lgqira/ngoma novices because things are so hard, because there is no peace in the world. Several seem to be already thinking ahead to when they will be igqira. Novice number 10 prays that she will have effective medicines revealed to her by her grandmother. Novice number 16 prays that another woman may have power. Novice number 17 wishes to stand atop Table Mountain—the highest, most prominent point in the Cape—and be a shining light to her people.

References to God, to Jesus, and to the ancestors suggest that there is no dividing line in the minds of these people between what is "African" and what is "Christian." In fact, many of them have been in contact with the church and even continue to be members, but they are now participants in ngoma to come to terms with their sickness, their situation, and their ukutwasa , "call."